1. Introduction

Currently, magnesite-chrome bricks have been widely used in cement rotary kiln in China [

1]. It has led to serious environmental problems, because the Cr(Ⅲ) is easily oxidized into the toxic Cr(Ⅵ) in magnesite-chrome bricks under natural condition [

2], especially spent magnesite-chrome bricks have not been reasonably handle. Therefore, it’s urgently to develop free chrome refractory bricks to substitute for magnesite-chrome bricks in cement rotary kiln [

3,

4,

5].

Magnesia-calcium bricks have been widely used as lining materials in ferrous metallurgy to produce the clean steel such as refining furnace [

6], because of their excellent performances [

7]. They are also regarded as the substitution of magnesite-chrome bricks for cement rotary kiln [

8], because they own the similar operational performances, such as high–temperature resistance, corrosion resistance and good coating adherence, etc. [

9,

10]. However, the application of magnesia-calcium bricks on cement rotary kiln has been restricted, since they have bad hydration resistance which can result in seriously structural damage [

11]. Related researches showed that aluminium oxide (Al

2O

3) could enhance the hydration resistance of magnesia-calcium bricks [

12,

13,

14].

There are more and more spent magnesia-calcium bricks not being reused effectively [

15], because of high impurity content such as Al

2O

3 that can reduce the usability of regenerated product, and further leads to a new environmental problem. Besides, there was very rare study on the utilization of spent magnesia-calcium bricks [

15,

16]. A kind of high hydration resistance regenerated magnesia-calcium brick was prepared basing on the spent magnesia-calcium bricks in previous work [

14], without removing the impurities of Al

2O

3 in spent magnesia-calcium bricks. It has not only realized the high reutilization rate of spent magnesia-calcium bricks, but also provided a possible pathway using regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks in the cement rotary kiln to substitute for magnesite-chrome bricks. Nevertheless, high-temperature performances such as high temperature strength and refractoriness need be degraded because of excessive impurity content, particularly the content of Al

2O

3 [

17,

18].

Therefore, in this work, the regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks with different content of additive Al2O3 were prepared respectively. The investigation and comparative of their phases, microstructures, room temperature and hot flexural strength, resistance to cement clinker corrosion and strength of coating adherence were carried out successively. This work can also provide a reference for the replacement of hazardous magnesite-chrome bricks in the cement rotary kiln by the regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Main Raw Materials of the Regenerated Magnesia-Calcium Bricks

The main raw materials of the regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks were spent magnesia-calcium bricks, fused magnesia and Al

2O

3 powder additive. The spent magnesia-calcium bricks were from a refining furnace in ferrous industry, the fused magnesia was from a refractory materials plant, and Al

2O

3 powder additive was a kind of analytical reagent. Their chemical compositions were measured by an 1800 X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF) and the results were shown in

Table 1.

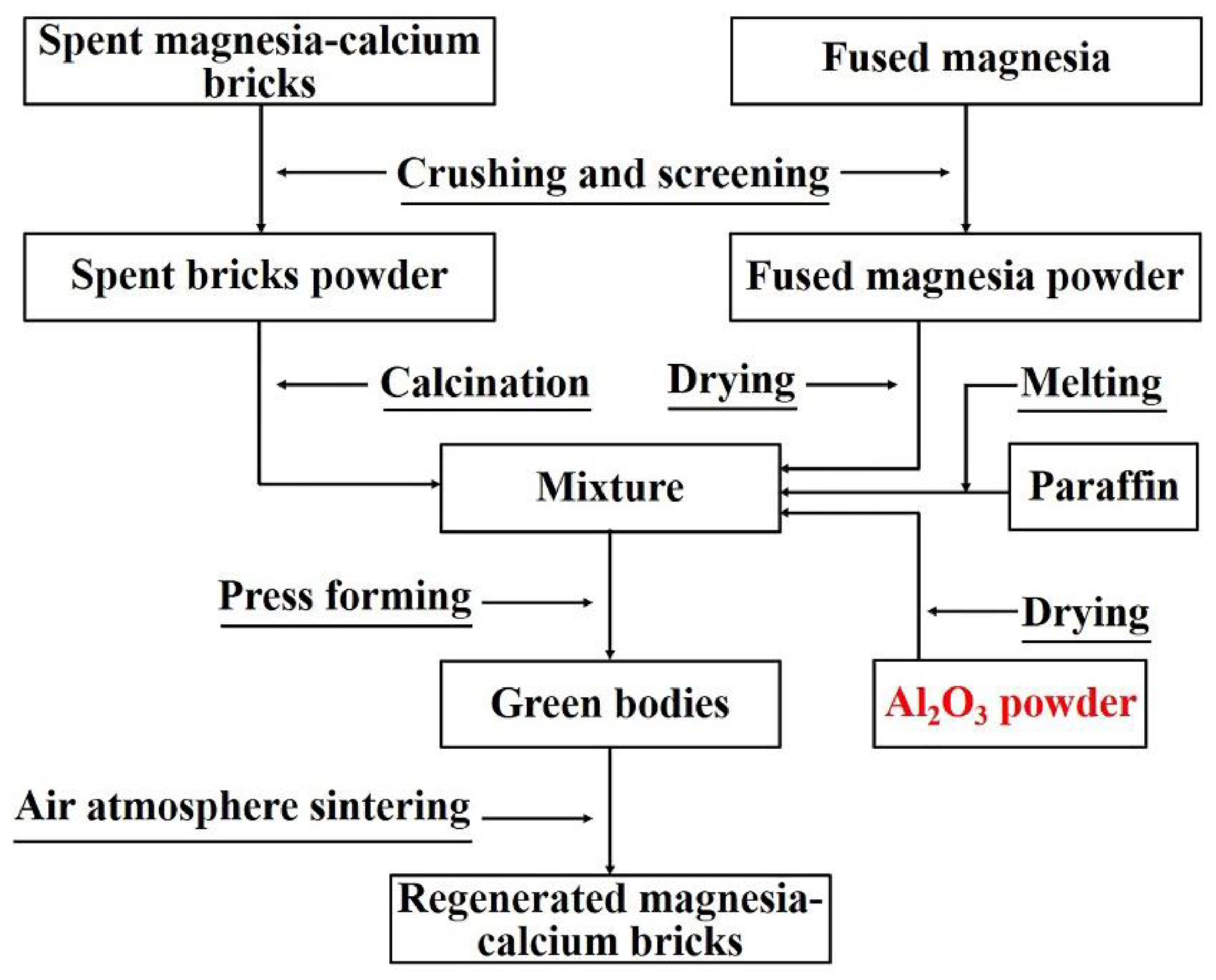

2.2. Preparation of the Regenerated Magnesia-Calcium Brick Samples

Figure 1 shows the synthetic process of the regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks. The mixture of the regenerated magnesia-calcium brick green body was prepared by using the main raw materials as show in

Table 1, and liquid paraffin as the binder firstly. The green body was prepared by 100 MPa pressing the mixture to form a rectangular of 60 mm × 8 mm × 8 mm subsequently. The regenerated magnesia-calcium brick sample was obtained by firing the green body at 1873 K for 2 h under an air atmosphere finally. In this work, three kinds of regenerated magnesia-calcium brick green bodies containing 0 wt.%, 1.5 wt.%, 3.0 wt.% Al

2O

3 powder additive were prepared, their compositions were shown in

Table 2, and their corresponding fired samples were marked as A0, A1.5, A3.0 respectively.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

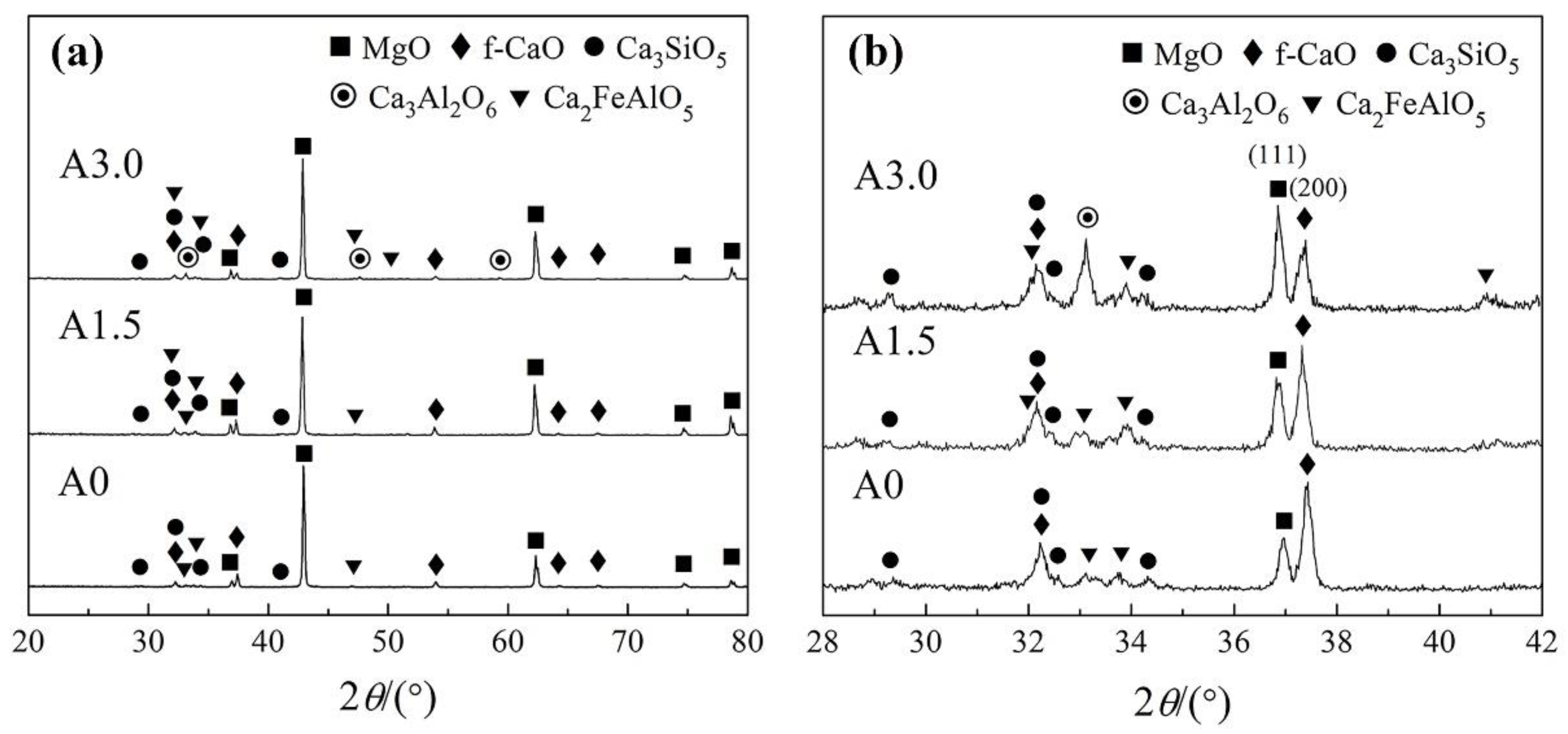

3.1. Phase Compositions of the Regenerated Magnesia-Calcium Bricks

Figure 3(a) shows that the main phase compositions of the sample A0, A1.5 were identical the magnesia (MgO), free calcium oxide (f–CaO), tricalcium silicate (Ca

3SiO

5, C

3S) and tetracalcium aluminoferrite (Ca

2FeAlO

5, C

4AF), while the main phase compositions of the sample A3.0 were the MgO, f–CaO, C

3S, C

4AF and tricalcium aluminate (Ca

3Al

2O

6, C

3A). It shows that a new phase C

3A generated and other phases did not change according to the increase of Al

2O

3 addition in the regenerated samples.

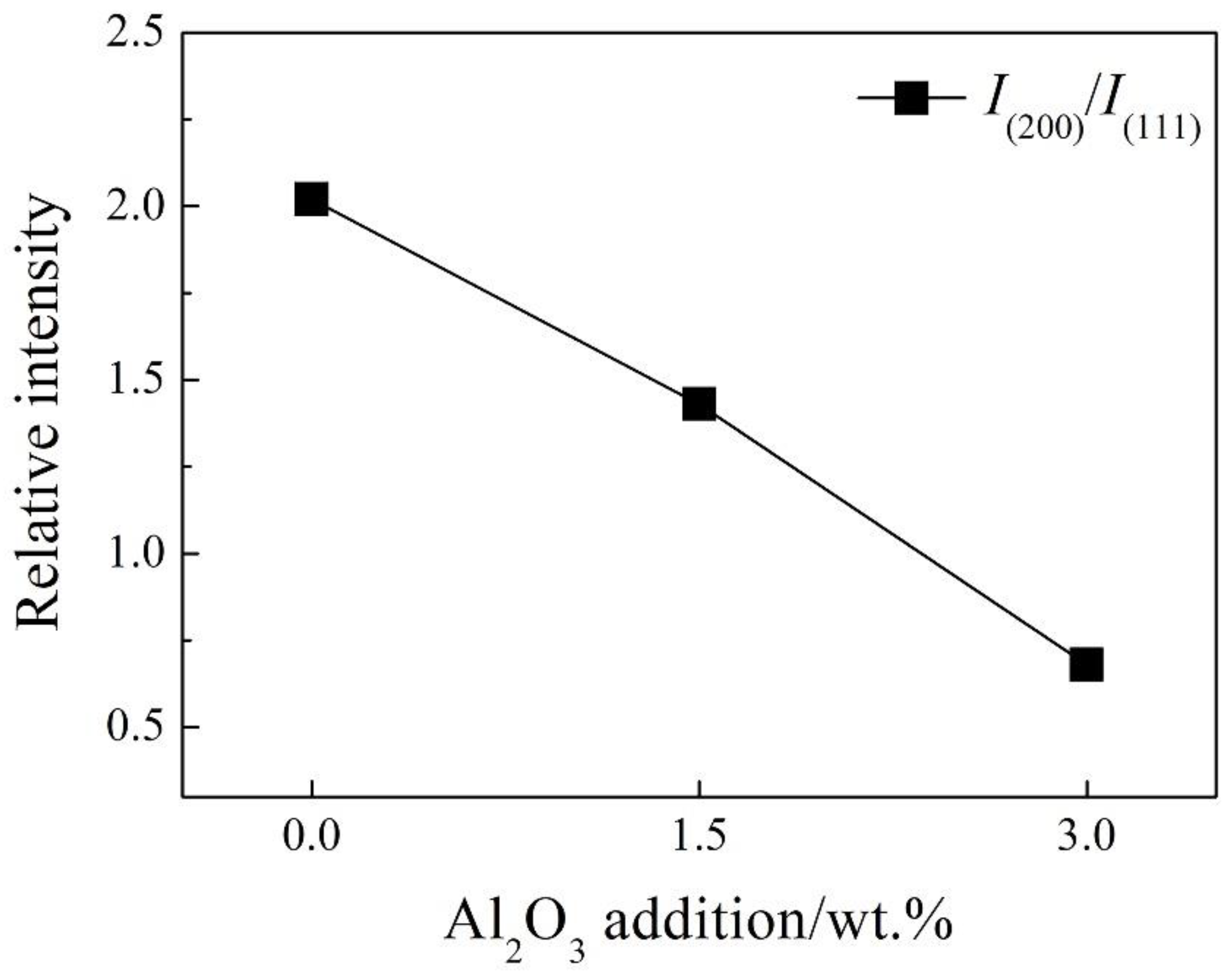

Figure 3(b) shows that the intensity of character diffraction peaks of f–CaO [

ICaO(200)] and MgO [

IMgO(111)] were the two highest peaks in the range of 28–42° and varied significantly. The relative intensities of

ICaO(200)/

IMgO(111) decreased observably along with the increase of increase of Al

2O

3 addition in the regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks as shown in

Figure 4. It also indicates that the content of f–CaO decreased along with the increase of Al

2O

3 addition in the regenerated samples, because the phase of MgO was exclusive and stable in the regenerated samples as shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows that the elements Fe and Al in the regenerated samples existed only in the C

4AF and C

3A phases. The standard reaction Gibbs energy of reactions between Fe

2O

3, Al

2O

3 and f–CaO which generate C

4AF and C

3A is shown in

Figure 5 [

19]. It shows that the phase of C

4AF generates preferentially when the impurity elements of Fe and Al exist concurrently, the phase of C

3A generates when there is excess Al element impurity (the mole ratio of Fe

2O

3 to Al

2O

3 < 1). Besides, preliminary study had proved that the phase of C

2F generates when the mole ratio of Fe

2O

3 to Al

2O

3 >1 [

20].

The theoretical content of the C

3S, C

4AF C

2F, C

3A and f–CaO phases (calcium–based phases) in the regenerated samples can be calculated by the Eq. (1) - (7) [

21]. The results (as shown in

Table 3) indicates that the theoretical content of the C

3A phase increased while that of the f–CaO phase decreased as the increasing of Al

2O

3 addition, and the Fe element of the sample A1.5 and A3.0 all generated the C

4AF phase. These calculation results were identical with the phase compositions analysis shown in

Figure 3.

w(C3S), w(C4AF), w(C2F), w(C3A), w(f–CaO)—the mass fraction of the calcium–based phases in the regenerated samples, wt.%;

w(SiO2), w(Al2O3), w(Fe2O3), w(CaO)—the mass fraction of the regenerated samples’ composition, wt.%.

3.2. Microstructures of Regenerated Magnesia-Calcium Bricks

Figure 6(a) shows the SEM images of the regenerated samples’ surfaces. The white phases shown in the selected areas

1,

2 and

3 in

Figure 6(a) were f–CaO, C

4AF or C

4AF–C

3A, and C

3S phases respectively, while the dark phases shown in

Figure 6(a) were all MgO phase. Besides, it indicates that the phase of C

4AF and C

3A showed a tendency of aggregation in the sample A1.5 and A3.0. It is because that the elements of Fe and Al exist in the form of liquid phase at the firing temperature (1873 K), the C

3A phase (melting point of 1808 K [

19]) and the C

4AF phase (melting point of 1688 K [

22]) successively crystallized from the liquid phases, and sintered together during the furnace cooling process.

Figure 6(b) shows the SEM images of the regenerated samples’ fractures. It shows that the sample A1.5 and A3.0 both present much more compactness than the sample A0, and the calcium–based phases were more continuous along with the increase of Al

2O

3 addition.

Table 3 shows that the increase of C

3A content was the main change among that of the calcium–based phases as Al

2O

3 addition increasing. Therefore, it can prove that the generation of C

3A improved the sinterability of the regenerated samples.

Figure 3 shows that there were too few of the C

3A phase to be observed in its character diffraction peak in the sample A1.5. It did not match the theoretical calculation as shown in

Table 3. It is because that part of the Al element was dissolved into the C

3S phase, reducing generation of the C

3A phase [

20]. The EDS analysis of the C

3S phase in

Figure 6(a)–A1.5 is shown in

Figure 7. It can be seen a significant solid solution appearing between the Al element and the C

3S phase.

3.3. Room Temperature and Hot Flexural Strength of the Regenerated Magnesia-Calcium Bricks

Figure 8 shows the results of the room temperature and hot (1573 K) flexural strength of the samples A0, A1.5 and A3.0. It indicates that the room temperature flexural strength of the regenerated samples enhanced, oppositely, the hot flexural strength of the regenerated samples reduced with Al

2O

3 addition increasing. It is due to the increasing of the low melting point phases content (C

4AF and C

3A) as shown in

Table 3 that improved the sinterability of the regenerated samples as shown in

Figure 6, and subsequently enhanced their bulk density as shown in

Figure 8. Thus, it results in the opposite phenomenon between the room temperature strength and the hot flexural strength of the regenerated samples with Al

2O

3 addition increasing.

3.4. Resistance to Cement Clinker Corrosion of the Regenerated Magnesia-Calcium Bricks

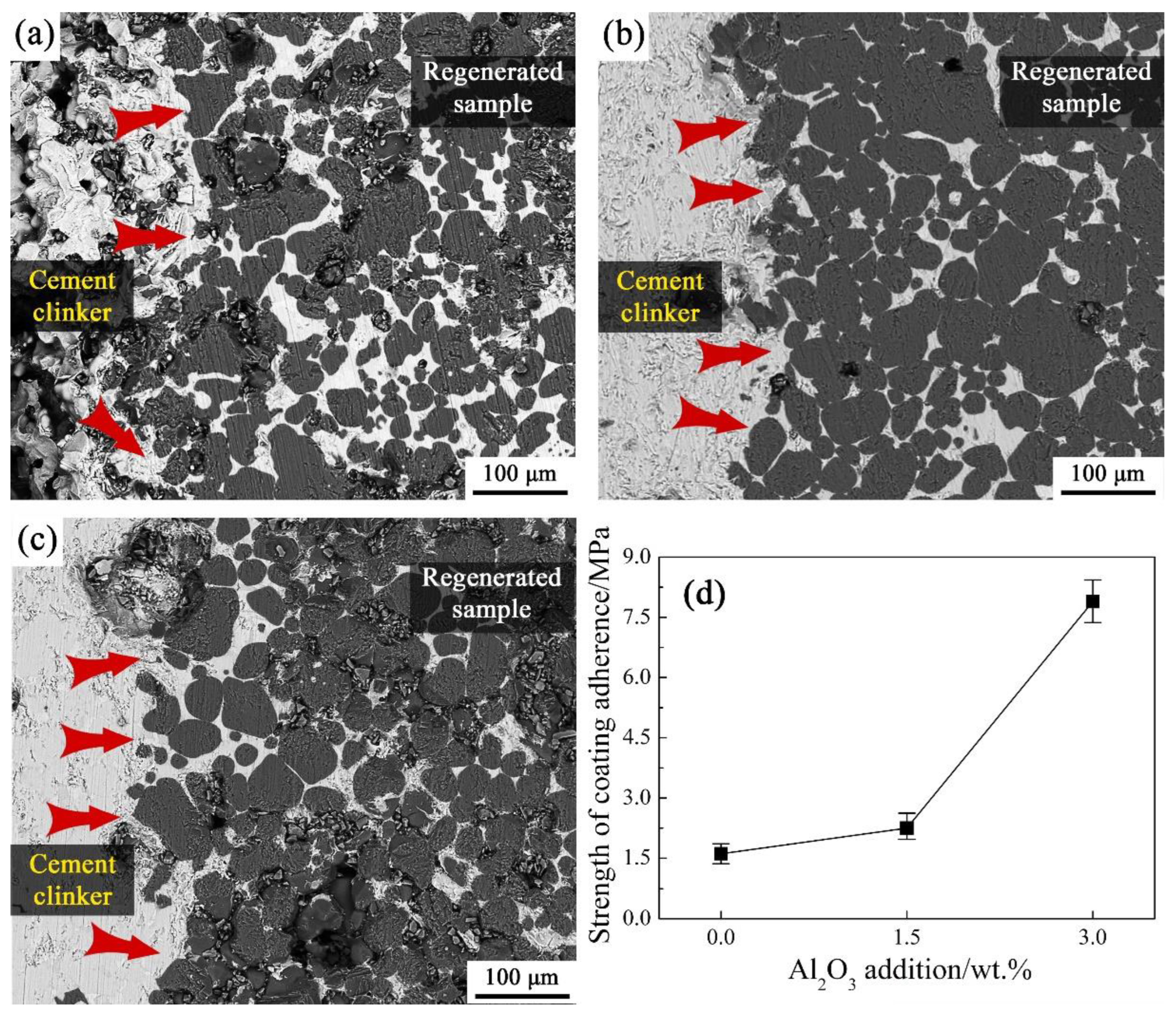

The SEM images of the sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0 cross-section after corrosion resistance experiment are shown in

Figure 9(a)–(c). It indicates that the cement clinker corrosion to the regenerated samples was gradually serious as the increasing of Al

2O

3 addition, and the cement clinker was more prone to corroding the regenerated samples along their calcium–based phases. It is because that the calcium–based phases of the regenerated samples were composed of the C

3S, C

4AF, C

3A and f–CaO phases, among which the phases of C

4AF and C

3A content increased with Al

2O

3 addition increasing. It improved the wettability of the regenerated samples, and thus, the melting cement clinker was much easier to corrode the regenerated samples along the areas of these low melt point phases [red arrow pointing out in Figure(a)–(c)] as they all exist in liquid phase form at 1823 K.

Figure 9(d) shows an increasing tendency of the regenerated samples’ coating adherence along with the increase of Al

2O

3 addition. It is because that the reaction areas between the cement clinker and regenerated samples increase with additive Al

2O

3 increased, resulting in their strength of coating adherence enhanced.

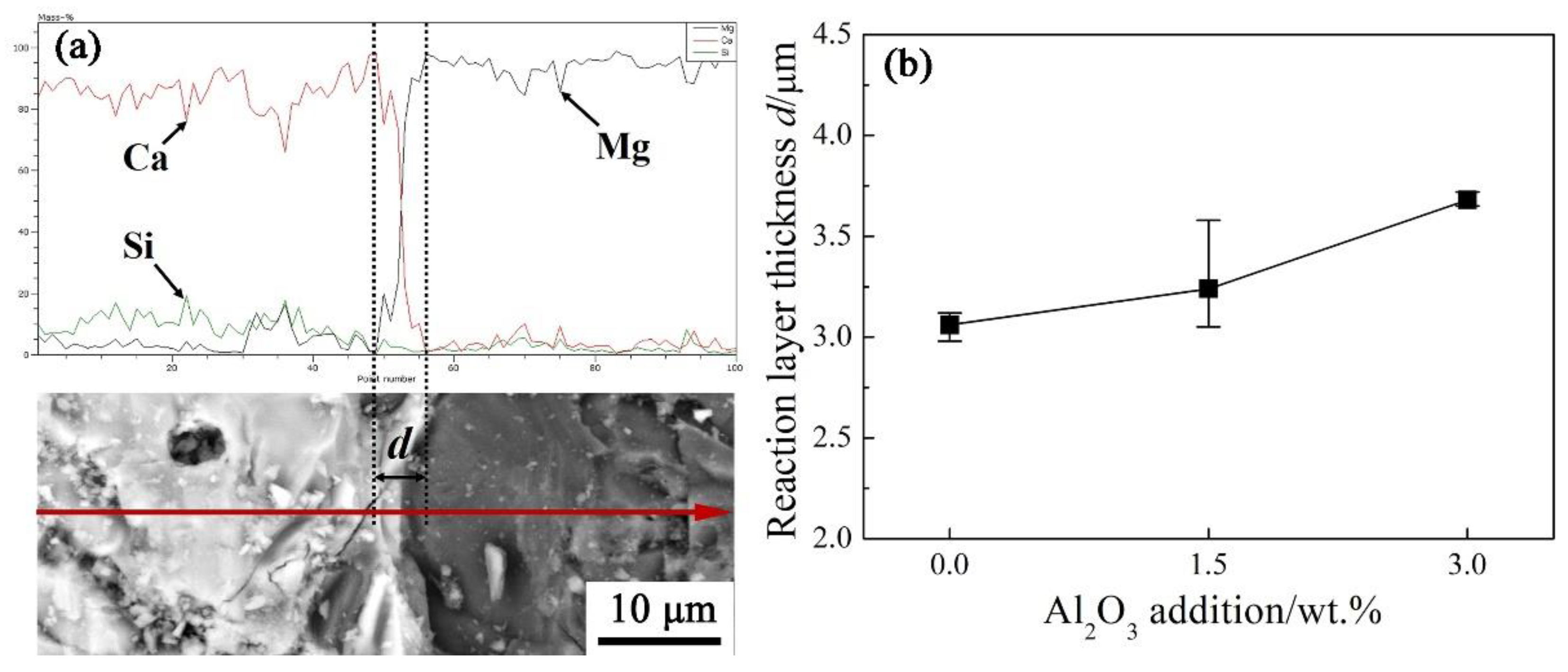

The corrosion of the cement clinker to the phase of MgO was carried out by an elements distribution scanning analysis across their contact areas as shown in

Figure 10(a). The analysis results indicate that a reaction layer containing element Ca, Si and Mg existed in the interfacial surface of these contact areas. The thickness

d of the reaction layer gradually became larger with Al

2O

3 addition increasing as shown in

Figure 10(b), which also indicates an aggravating corrosion of the cement clinker to the phase of MgO.

Generally, Al

2O

3 addition had a positive effect on the room temperature performances of the regenerated samples, such as the bulk density and the room temperature flexural strength, on the contrary, it had an adverse effect on the high-temperature performances of the regenerated samples, such as the hot flexural strength and corrosion resistance except of the strength of coating adherence, because of the low melting point phases of C

4AF and C

3A generating. It had been reported that the room temperature flexural strength and the strength of coating adherence of the chromium–free refractories applied on cement rotary kiln were lager than 21.60 MPa and 0.52 MPa [

23], in comparison that of sample A0, A1.5, A3.0 were 68.58 MPa, 70.91 MPa, 93.11 MPa and 1.61 MPa, 2.25 MPa, 7.89 MPa accordingly. It shows that sample A0, A1.5, A3.0 could all meet the room temperature flexural strength and the strength of coating adherence. However, the hot flexural strength of sample A0, A1.5, A3.0 was 9.65 MPa, 4.34 MPa, 3.62 MPa respectively, and it shows that the hot flexural strength of sample A0 was only higher than that of the literature report (lager than 5.4 MPa) [

24]. Therefore, the sample A0 can be considered as most suitable regenerated sample for cement rotary kiln, and the content of Al

2O

3 in the regenerated magnesia-calcium brick should not be higher than 1.1 wt.% (without extra Al

2O

3 addition).

4. Conclusions

The magnesia-calcium brick samples were prepared by using spent magnesia-calcium brick, fused magnesia and Al2O3 powder additive as the main raw materials, liquid paraffin as the binder, and firing at 1873 K for 2 h under an air atmosphere respectively, among which the Al2O3 powder addition was 0 wt.%, 1.5 wt.%, 3.0 wt.%. The main phase compositions of the sample A0 and A1.5 were MgO, f–CaO, C3S, C4AF, and a new phase C3A was observed in the sample A3.0 besides MgO, f–CaO, C3S, C4AF. There was a solid solution appearance between the Al element and the C3S phase, resulting in the actual content of the C3A phase was lower than the theoretical calculation, and it led to the phase of C3A being not observed in the sample A1.5. The room temperature performances of the regenerated samples such as bulk density and flexural strength enhance along with the increase of Al2O3 addition, since the low melting point phases of C4AF and C3A content increase which improve the sinterability of the regenerated samples. However, the high-temperature performances of the regenerated samples such as hot flexural strength (1573 K) and corrosion resistance (1823 K) degrade as the addition of Al2O3 increasing, because the melting points of the C4AF and C3A phases were close to 1573 K, furthermore, they were in liquid phase form at 1823 K that wetted the regenerates sample to enhance the reaction between the cement clinker and the MgO phase, resulting in the increasing of the strength of coating adherence. The sample A0 can be considered as most suitable regenerated sample for cement rotary kiln, as comparing the main performances with other chromium–free refractories for cement rotary kiln, that is, the total content of Al2O3 in the regenerated magnesia-calcium brick should be no more than 1.1 wt.%.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.G.-B. and Z.M.; methodology, Q.G.-B., H.Y.-D. and Z.M.; software, Q.G.-B. and W.H.-G.; validation, H.J. and Z.X.-H.; formal analysis, Q.G.-B. and H.J.; investigation, Q.G.-B., H.Y.-D. and P.B.; resources, H.J. and P.B.; data curation, Q.G.-B., W.H.-G. and Z.X.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.G.-B.; writing—review and editing, Z.M., H.Y.-D. and W.H.-G.; visualization, Q.G.-B., H.J. and Z.X.-H.; supervision, P.B. and Z.M.; project administration, Q.G.-B. and P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by 2023 Zhanjiang Ocean Young Talent Innovation Project of China (2023E0009) and National Natural Science Foundation Outstanding Youth Science Fund project of China (52322806).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nievoll, J.; Guo, Z.Q.; Shi, S. Performance of magnesia hercynite bricks in large Chinese cement rotary kilns. RHI Bulletin 2006, 3, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schacht, C. Refractories Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; p. 607. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, M.O. Price temper steel market promise. Ind. Miner. 1994, 324, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Jones, P.T.; Parada, S.; Boydens, E.; Dyck, J.V.; Blanpain, B.; Wollants, P. Degradation mechanisms of magnesia–chromite refractories by high–alumina stainless steel slags under vacuum conditions. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 26, 3831–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez–Rodríguez, C.; Antonio–Zárate, Y.; Revuelta–Acosta, J.; Verdeja, L.F.; Fernández–González, D.; López–Perales, J.F.; Rodríguez–Castellanos, E.A.; García–Quiñonez, L.V.; Castillo–Rodríguez, G.A. Research and development of novel refractory of MgO doped with ZrO2 nanoparticles for copper slag resistance. Materials. 2021, 14, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.Q.; Fang, B.X.; Zhang, W.J.; Li, X.C.; Wan, H.B. Corrosion mechanism of ladle furnace refining slag to fired MgO–CaO bricks. China’s refractories, 2010, 019, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.W.; Li, N. Refractories for clean steel making. Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2002, 81, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, G.B.; Peng, B.; Guo, M.; Zhang, M. Regeneration utilization of spent MgO–CaO bricks for argon oxygen decarburization furnace. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 41, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Soltanieh, M.; Payandeh, Y. Relationship between oxygen chemical potential and steel cleanliness. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2005, 12, 28–33, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Rabah, M.; Ewais, E.M.M. Multi–impregnating pitch–bonded Egyptian dolomite refractory brick for application in ladle furnaces. Ceram. Int. 2009, 35, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Tian, L.; Li, G.H.; Tian, F.R. MgO–CaO refractories, Ed. by L. Song, Metallurgical Industry Press, Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 25, 52–57.

- Yu, J.K.; Dai, W.B. Influence of fine α–Al2O3 powder on the properties of the magnesia–calcia refractories. J. Northeast. Univ. (Natural Science), 2003, 24, 1068–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Shahraki, A.; Ghasemi–Kahrizsangi, S.; Nemati, A. Performance improvement of MgO–CaO refractories by the addition of nano–sized Al2O3. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 198, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.B.; Peng, B.; Li, X.; Guo, M.; Zhang, M. Hydration resistance and mechanism of regenerated MgO–CaO bricks. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2015, 123, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.B.; Shen, X.L. Effects of spent MgO–CaO bricks additive amount on the properties of baking MgO–CaO bricks. Refractories 2008, 42, 392–393. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Shi, G.; Wei, F.C.; Wang, C.Y. Preparation of magnesia–calcia dry mix from used MgO–CaO bricks. Refractories 2012, 46, 126–128. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.Z.; Chen, S.J.; Wei, Z.L.; Zhang, F.Q. Effect of Al2O3 additions on characteristic of burned magnesia–calcia brick. J. Anshan Univ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 26, 425–428. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Liu, L.; Xiao, L.H.; Huo, X.T.; Guo, M.; Zhang, M. , Effect of MgO on corrosion mechanism under LF refining slag for MgAlON–MgO composites synthesized from spent MgO–C brick: Wetting behaviour, reaction process and infiltration mechanism. J. ALLOY. COMPD. 2023, 963, 171278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.P.; Jiang, T.; Li, G.H.; Guo, Y.F.; Yang, Y.B. Thermodynamics of reactions among Al2O3, CaO, SiO2 and Fe2O3 during roasting processe. Thermodynamics–Interaction Studies–Solids, Liquids and Gases, Chapter 30; Moreno–pirajan, InTech, 2011, 825–838.

- Qiu, G.B.; Peng, B.; Yue, C.S.; Guo, M.; Zhang, M. Properties of regenerated MgO–CaO refractory bricks: impurity of iron oxide. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 2933–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.F.; Wang, X.M.; Wang, C. X.; Sun, P.Q. Magnesia and magnesium matrix composite refractories; Metallurgical Industry Press, Beijing, 2010, pp. 25, 32.

- Taschler, T. Refractory materials for the copper and lead industry, In Tehran International Conference on Refractories; Iran, 2004; pp. 302–320.

- Wang, Z.F.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.T.; Zhang, B.G.; Liu, H. Effects of rare earth oxides on physical properties and coating adhering performance of magnesia refractories. J. Wuhan Univ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 33, 595–598. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.X. Research on non–chromium refractory for rotary cement kiln in burning zone. Master Dissertation, University of Science and Technology Liaoning, Anshan Liaoning, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

The synthetic process flow chart of regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks with Al2O3 powder addition.

Figure 1.

The synthetic process flow chart of regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks with Al2O3 powder addition.

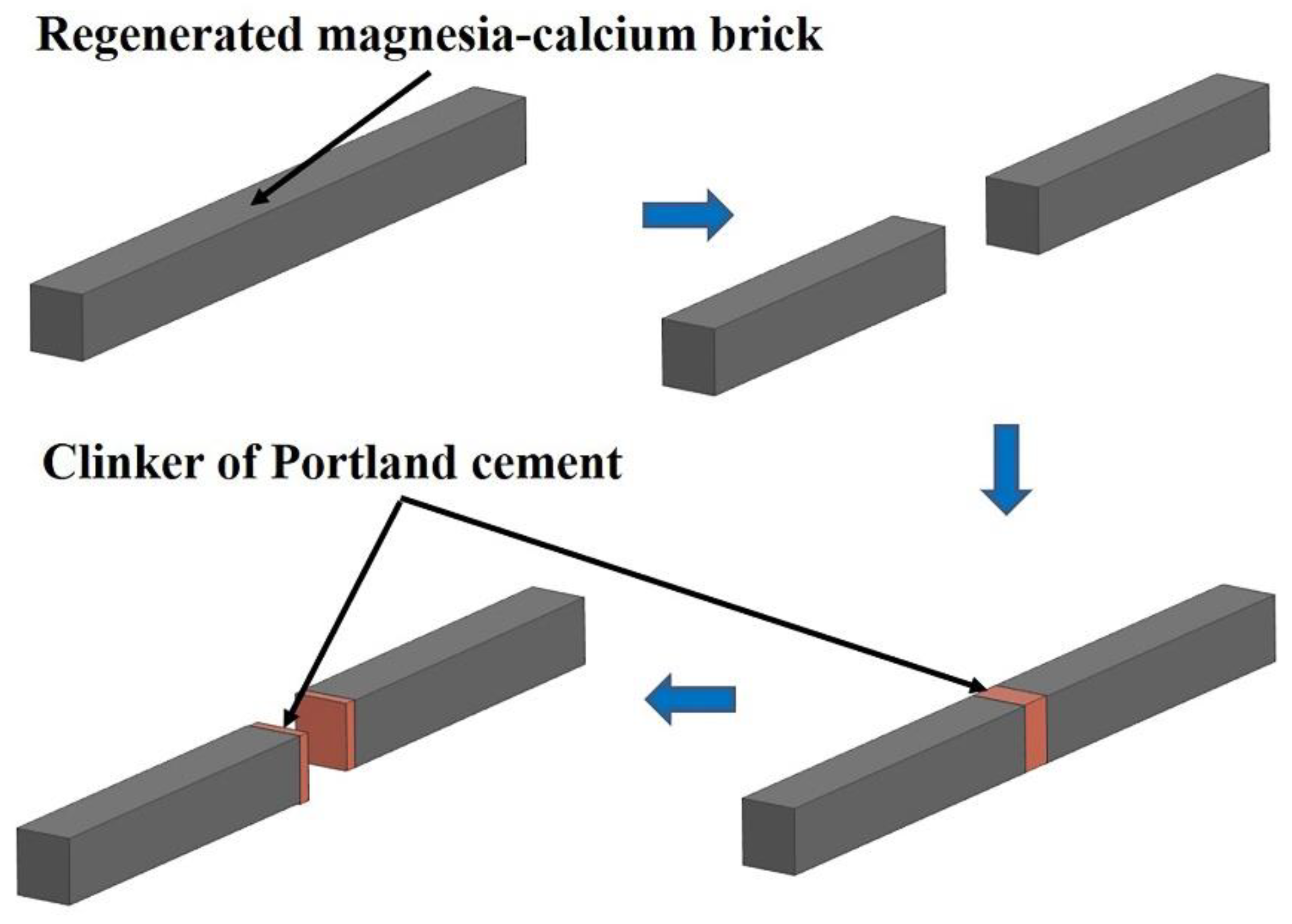

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the resistance to cement clinker corrosion and the coating adherence experiment of the regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the resistance to cement clinker corrosion and the coating adherence experiment of the regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of the sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0: (a) the range of 20–80°; (b) the range of 28–42°.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of the sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0: (a) the range of 20–80°; (b) the range of 28–42°.

Figure 4.

Relative intensities of ICaO(200)/IMgO(111) of the sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0.

Figure 4.

Relative intensities of ICaO(200)/IMgO(111) of the sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0.

Figure 5.

Standard reaction Gibbs energy of the reactions between Fe2O3, Al2O3 and f–CaO vs. temperature in the regenerated samples.

Figure 5.

Standard reaction Gibbs energy of the reactions between Fe2O3, Al2O3 and f–CaO vs. temperature in the regenerated samples.

Figure 6.

(a) SEM images of the regenerated samples’ surfaces; (b) SEM images of the regenerated samples’ fractures.

Figure 6.

(a) SEM images of the regenerated samples’ surfaces; (b) SEM images of the regenerated samples’ fractures.

Figure 7.

The elements of Ca, Si, Al distribution of the C3S phase in the sample A1.5.

Figure 7.

The elements of Ca, Si, Al distribution of the C3S phase in the sample A1.5.

Figure 8.

The room temperature and hot flexural strength, and the bulk density of the sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0.

Figure 8.

The room temperature and hot flexural strength, and the bulk density of the sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0.

Figure 9.

SEM images of the regenerated samples’ cross-section after corrosion resistance experiment: (a) sample A0; (b) sample A1.5; (c) sample A3.0; (d) strength of coating adherence of the sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0.

Figure 9.

SEM images of the regenerated samples’ cross-section after corrosion resistance experiment: (a) sample A0; (b) sample A1.5; (c) sample A3.0; (d) strength of coating adherence of the sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0.

Figure 10.

(a) The elements distribution scanning analysis across the contact area of the cement clinker and the MgO phase; (b) reaction layer thickness d of the sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0.

Figure 10.

(a) The elements distribution scanning analysis across the contact area of the cement clinker and the MgO phase; (b) reaction layer thickness d of the sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0.

Table 1.

Compositions of the main raw materials of the regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks (wt.%).

Table 1.

Compositions of the main raw materials of the regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks (wt.%).

| Constituents |

MgO |

CaO |

SiO2

|

Fe2O3

|

Al2O3

|

| Spent magnesia-calcium bricks |

58.18 |

33.92 |

2.81 |

2.68 |

1.51 |

| Fused magnesia |

94.16 |

1.63 |

2.64 |

1.00 |

0.27 |

| Al2O3 powder |

– |

– |

0.30 |

0.03 |

98.75 |

Table 2.

Compositions of the regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks’ green bodies (wt.%).

Table 2.

Compositions of the regenerated magnesia-calcium bricks’ green bodies (wt.%).

| Samples |

MgO |

CaO |

SiO2

|

Fe2O3

|

Al2O3

|

Al2O3 powder additive |

| A0 |

70 |

23.31 |

2.66 |

2.21 |

1.10 |

0 |

| A1.5 |

70 |

23.31 |

2.66 |

2.21 |

1.10 |

1.5 |

| A3.0 |

70 |

23.31 |

2.66 |

2.21 |

1.10 |

3.0 |

Table 3.

Theoretical contents of each calcium–based phases in sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0 (wt.%).

Table 3.

Theoretical contents of each calcium–based phases in sample A0, A1.5 and A3.0 (wt.%).

| Calcium–based phases |

A0 |

A1.5 |

A3.0 |

| C3S |

10.11 |

9.98 |

9.85 |

| C4AF |

5.25 |

6.62 |

6.53 |

| C2F |

0.82 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| C3A |

0.00 |

3.05 |

6.81 |

| f–CaO |

13.11 |

10.66 |

8.12 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).