1. Introduction

In the current context of climate change and increasing pressure to reduce the carbon footprint of resource-intensive industries, the construction sector faces the challenge of transforming its materials and processes towards more sustainable alternatives [

1,

2]. Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), the basis of conventional concrete, is responsible for approximately 7–9% of global CO₂ emissions, mainly due to the calcination of calcium carbonate at temperatures nearing 1400 °C, which requires high energy consumption and releases significant amounts of greenhouse gases [

3].

In response, alternative cementitious materials—particularly geopolymers and alkali-activated slag (AAS) systems—have garnered growing interest [

2,

4,

5]. These materials utilise industrial by-products rich in silica and alumina—such as fly ash (FA) and ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS)—that, when chemically activated with alkaline solutions, form a cementitious matrix offering good mechanical strength, acceptable durability, and a substantial reduction in CO₂ emissions. In addition to their low cost and abundance, these residues help reduce clinker dependency and mitigate the environmental impacts of traditional cement production [

6,

7].

Nevertheless, one of the most critical technical challenges of AAS systems is their poor resistance to carbonation, which limits their use in structures exposed to urban or industrial environments with elevated CO₂ concentrations [

7,

8]. Carbonation occurs when atmospheric CO₂ penetrates the concrete, reacts with alkaline compounds in the matrix, and progressively reduces the pH—disrupting the passive film that protects the embedded steel and initiating corrosion processes [

9,

10,

11].

Unlike Portland concrete, which contains substantial amounts of calcium hydroxide (CH), AAS matrices possess a limited alkaline reserve based on C–A–S–H or N–A–S–H gels, offering reduced buffering capacity against CO₂ [

12]. Furthermore, their porous structure may facilitate gas diffusion if not properly controlled [

13]. This loss of alkalinity and the onset of corrosion present significant technical risks for structural durability and lead to elevated maintenance costs—contradicting the sustainability goals that motivate the use of such materials [

12].

To address this issue, strategies such as special curing regimes, hybrid activators, or functional additives have been proposed [

13]. A promising option is the use of anion-intercalating lamellar materials, such as calcined magnesium–aluminium layered double hydroxide (CLDH) [

14]. This material, part of the LDH family, is characterised by its anion-capturing ability, structural rehydration (“memory effect”), and controlled release of OH⁻, thus helping preserve internal alkalinity and hinder CO₂ ingress [

15].

When incorporated into the AAS matrix, CLDH acts not only as an alkaline buffer but also modifies the microstructure, reduces pore connectivity, and limits the penetration rate of aggressive gases [

16,

17]. Upon rehydration in humid and carbonated environments, CLDH partially restores its lamellar structure, releasing ions that help maintain a pH conducive to steel protection [

18,

19]. This regenerative capability and synergy with alkaline activators make CLDH an attractive additive from both technical and economic perspectives [

20].

The present study investigates the incorporation of increasing CLDH dosages (2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%) as partial slag replacement in AAS mixtures. These levels are based on previous studies indicating that low dosages may be insufficient to trigger a significant structural reconstruction of CLDH, while higher levels might lead to oversaturation of lamellar phases, formation of inert residues, or adverse effects on the durability and corrosion resistance of the system. This approach aims to identify the optimal dosage that maximizes protection against carbonation-induced corrosion without compromising the microstructural integrity of the matrix.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

This study employed two primary cementitious materials: ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) and calcined layered double hydroxide (CLDH). The GGBFS, a by-product of the steel industry supplied by Acerías Paz del Río (Boyacá, Colombia), was obtained via water granulation, ensuring a reactive vitreous phase suitable for alkaline activation. Its chemical composition, determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy, showed high contents of calcium (CaO), silicon (SiO₂), aluminium (Al₂O₃), and magnesium (MgO) oxides, which are characteristic of a basic-type slag.

The CLDH used was a synthetic hydrotalcite with a lamellar double hydroxide structure, primarily composed of magnesium and aluminium. This material was pre-calcined at temperatures above 500 °C to induce crystalline restructuring, enhancing its memory effect in alkaline environments and promoting the adsorption of carbonate species. The CLDH featured a Mg/Al molar ratio close to 3:1, making it compatible with highly alkaline cementitious matrices.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of both materials was analysed via XRF.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of both materials was analysed via XRF.

| |

Si O2

|

|

Al2O3

|

Fe2O3

|

CaO |

MgO |

SO3

|

MnO |

K2O |

P2O5

|

| GBFS |

34.8 |

|

15.5 |

2.4 |

37.4 |

2.3 |

1.4 |

3.8 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

| CLDH |

1.5 |

|

24.5 |

- |

0.5 |

65.0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Two types of mixtures were prepared depending on the analysis objective: Alkali-activated pastes were used for physico-chemical, mineralogical, and microstructural characterization, composed only of GGBFS, CLDH, and activator solution—without any aggregates and alkali-activated concrete was used for durability testing related to reinforcement corrosion. These mixes incorporated the same binder matrix along with coarse and fine aggregates. The coarse aggregate was crushed granite with a nominal maximum size of 19 mm and a bulk density of 2.65 g/cm³. The fine aggregate consisted of natural siliceous sand with a fineness modulus of 2.70 and a controlled moisture content of 2%. Both aggregates met ASTM C33 standards [

21]. The concrete also included embedded reinforcing steel bars, cleaned and surface-treated prior to casting to ensure proper bond. CLDH contents of 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8% by total binder mass (GGBFS + CLDH) were assessed in both mixture types. Water/activator and activator/binder ratios were held constant across all systems.

The chemical activation of the mixtures was carried out using a biphasic alkaline solution comprising 85% by mass sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and 15% sodium silicate (Na₂SiO₃). The sodium hydroxide was dissolved in deionised water to achieve a concentration of 14 mol/L, ensuring a high availability of OH⁻ ions to promote the initial dissolution of the slag. This reagent, with a purity of 98% and supplied in pellet form, was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The liquid sodium silicate used had a typical composition of 9.1% Na₂O, 27.5% SiO₂, and 63.4% H₂O, corresponding to a SiO₂/Na₂O molar ratio of 3.02. This ratio was selected to favour the formation of (C,N)–A–S–H-type gels during hydration, balancing the availability of reactive silica with the system’s alkalinity.

The ratio between the total mass of the activator solution and the cementitious material (slag + CLDH) was fixed at 0.55, optimised to ensure sufficient workability and efficient system activation. Initial curing of the pastes was performed in an oven at a constant temperature of 85 °C for 24 hours, aiming to accelerate the dissolution–precipitation reactions characteristic of alkali-activated binders. After this period, samples were allowed to cool to ambient temperature and subsequently stored under stable conditions.

Methods

The identification of mineral phases present in the samples was carried out using X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a PANalytical X’Pert PRO MPD instrument (Malvern PANalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands), configured in reflection mode with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). Measurements were conducted over a 2θ angle range from 5° to 65°, with a step size of 0.02° and a counting time of 0.5 seconds per interval.

To assess the atomic environment of silicon and aluminium, magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (MAS-NMR) spectroscopy was performed using a JEOL ECZ600R spectrometer operating at 119.2 MHz for ²⁹Si and 156.4 MHz for ²⁷Al, under a magnetic field strength of 14.1 T. A spinning frequency of 12 kHz was used, alongside external references such as tetramethylsilane (TMS) and Al(H₂O)₆³⁺. A pulse length of 3.5 μs and a relaxation delay of 5 s were applied to minimise saturation effects.

The microstructural analysis was complemented by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Hitachi SU8230 field emission system.

To investigate the behaviour under carbonation-induced corrosion, cylindrical concrete specimens (10 cm in diameter and 20 cm in height) were prepared, each incorporating a single longitudinally embedded ribbed steel bar. The reinforcing bars had a diameter of 12 mm and a total length of 15 cm, of which 10 cm were embedded in the cementitious matrix, while the remaining 5 cm were left exposed for electrical connection during testing. The exposed section of the bars was coated with epoxy paint to ensure electrical insulation, thereby restricting the active area to the embedded segment.

Prior to casting, the bars were mechanically cleaned to remove surface oxides and to ensure proper bond with the matrix. These specimens were specifically used for electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) testing.

Concrete samples were subjected to accelerated carbonation conditions in order to replicate, within a shorter timespan, the effects of CO₂ ingress into the cementitious matrix. Exposure took place in a controlled chamber with 3% CO₂ concentration, 65% relative humidity, and a constant temperature of 25 °C over a period of 90 days.

Carbonation depth was determined using an alcoholic phenolphthalein solution as a pH indicator. Upon application to the fractured surface of the specimens, carbonated areas (colourless) and still-alkaline regions (pink) were visually differentiated, and the average depth of carbonation front was measured using a millimetre-scale ruler.

The corrosion state of embedded steel was exclusively assessed using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). A Gamry Reference 3000 potentiostat/galvanostat was employed, configured with a three-electrode electrochemical cell: the embedded steel bar as the working electrode, a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference, and a stainless steel mesh as the counter-electrode. A sinusoidal perturbation of ±10 mV was applied across a frequency range from 100 kHz to 10 mHz. The resulting data were represented using Nyquist plots, allowing for the determination of system polarisation resistance and indirect estimation of corrosion current density.

3. Results

3.1. Composition Analysis

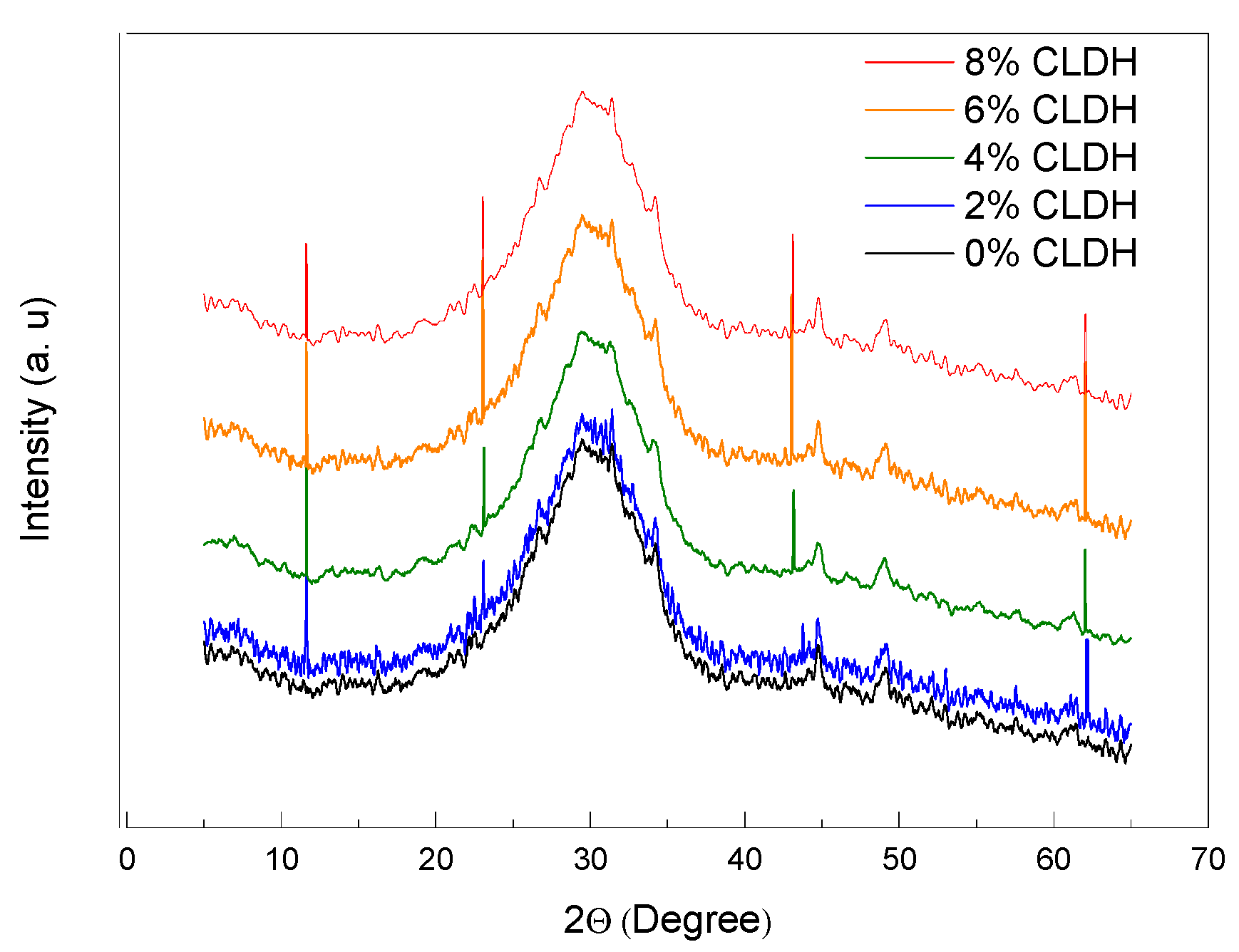

3.1.1. XRD

Figure 1 displays the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes incorporating varying amounts of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH): 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%. The reference mix (0% CLDH) exhibits a typical diffraction profile for AAS materials, characterised by a broad amorphous halo centred around 30° indicative of C–A–S–H gel formation, which lacks long-range crystalline order detectable by XRD [

22].

With the addition of 2% CLDH, weak peaks emerge near 11.6° and 23.2°, corresponding to the (003) and (006) planes of hydrotalcite-like (LDH) phases. These reflections are consistent with a lamellar structure of trigonal–rhombohedral symmetry (space group R-3m), typical of LDHs reformed from mixed Mg–Al oxides [

23]. Their low intensity suggests a limited degree of structural reconstitution at this dosage.

Increasing the CLDH content to 4%, and more markedly to 6%, leads to a pronounced intensification of the LDH peaks, confirming the active reconstruction of the lamellar structure via interlayer anion uptake (CO₃²⁻, OH⁻). This reflects effective activation of the memory effect, whereby the calcined oxides regenerate the LDH structure in an alkaline environment [

24]. From 4% CLDH onwards, additional reflections near 43° and 62° appear, becoming more prominent at 8% dosage. These are attributed to residual magnesium oxide (MgO), indicating that a portion of the CLDH did not fully rehydrate, likely due to limited anion availability or matrix saturation. This progression implies a coexistence of partial structural regeneration with residual crystallisation of undesired phases.

A dosage of 6% CLDH is identified as optimal, as it yields the highest intensity of LDH peaks without significant interference from residual phases. This balance ensures sufficient reactivity to promote slag hydration while maintaining robust C–A–S–H gel formation. In contrast, the 8% CLDH mixture exhibits a relative decrease in LDH peak intensity alongside a marked increase in MgO signals, suggesting a threshold beyond which further CLDH addition becomes ineffective [

25]. The excess CLDH may behave as an inert filler, diluting the highly reactive slag and potentially hindering the formation of cementitious products, with adverse effects on microstructural densification and mechanical performance.

Figure 1. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes with varying proportions of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH) as partial slag replacement (0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%).

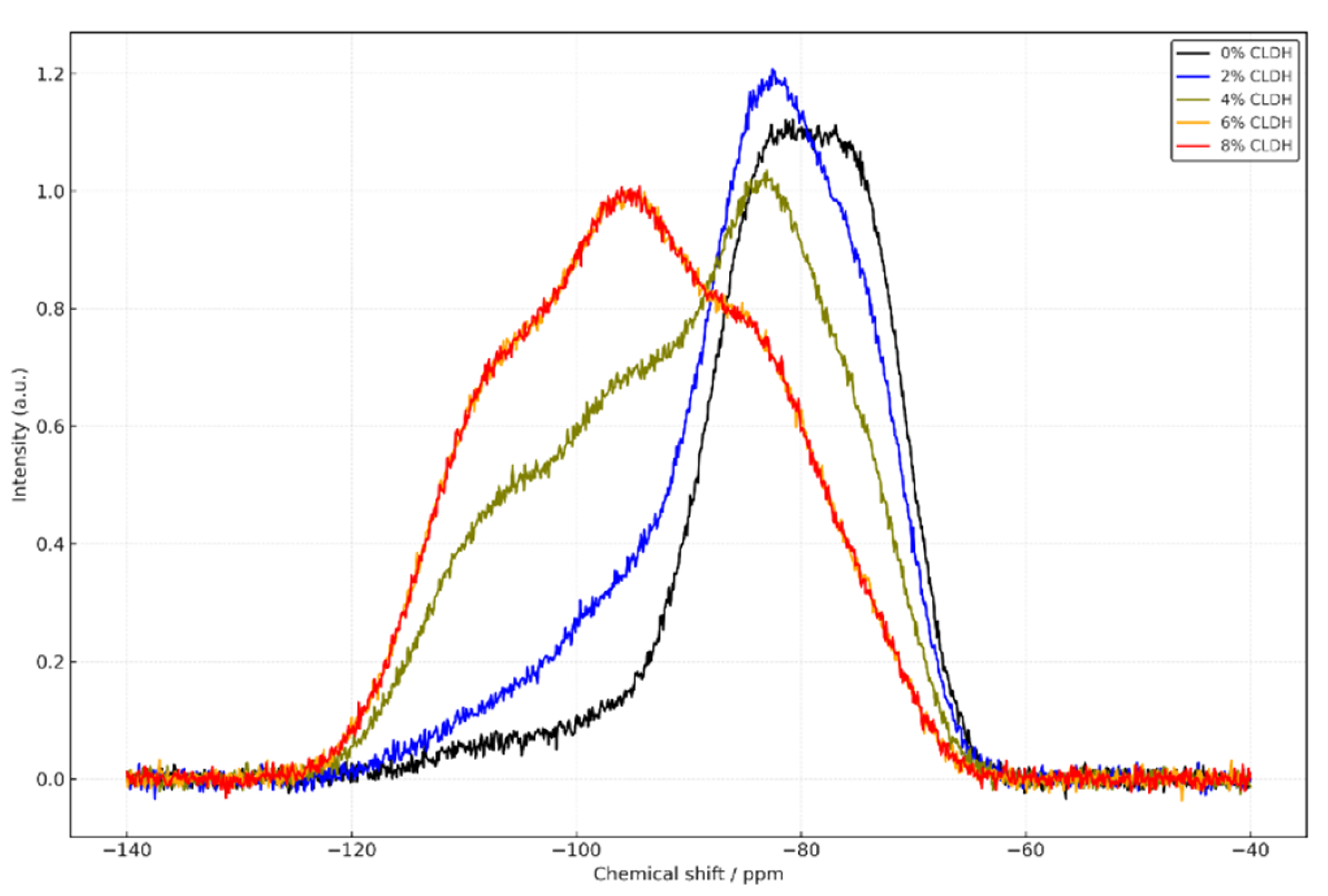

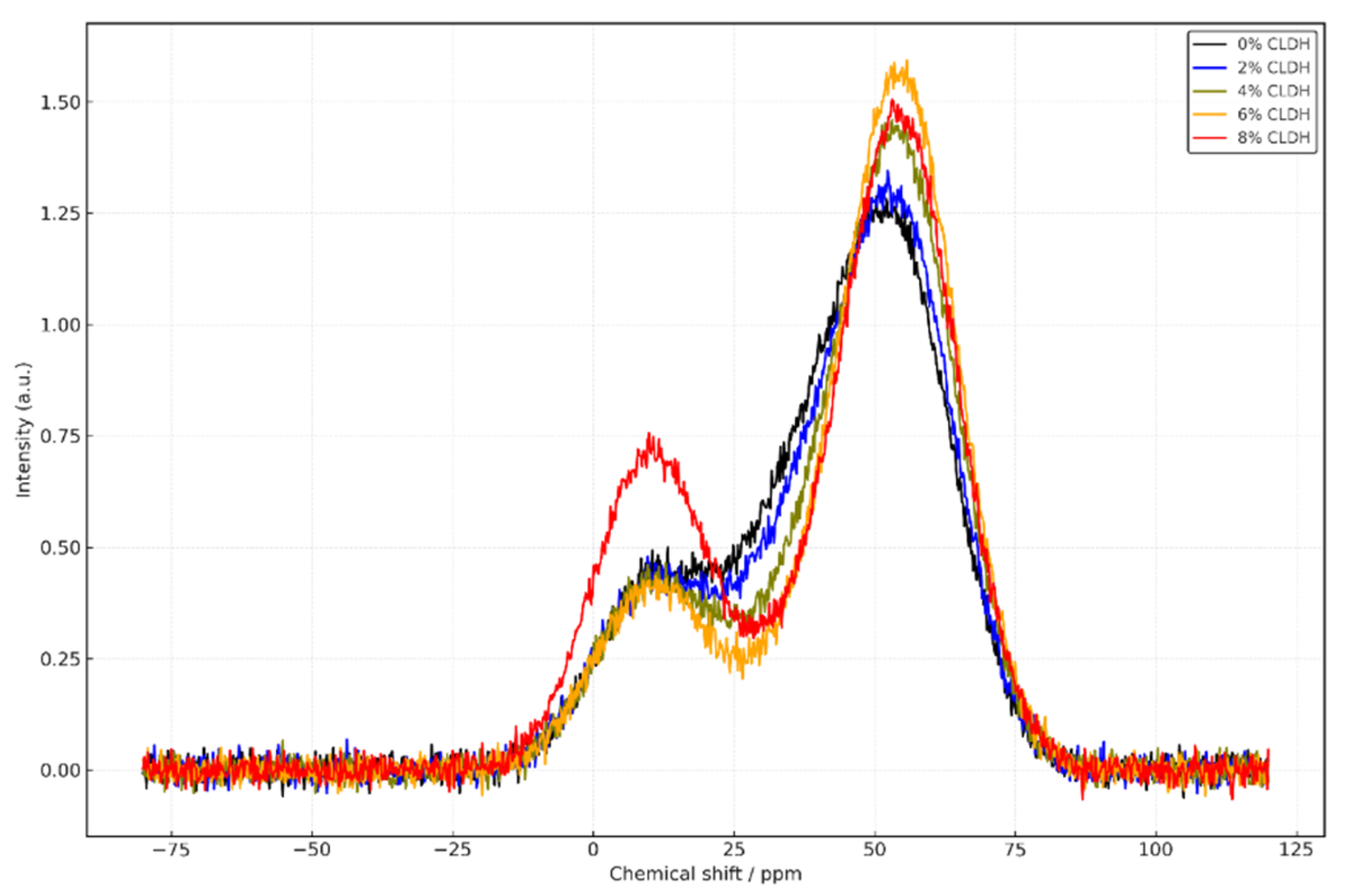

3.1.2. NMR

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 present the magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (MAS-NMR) spectra for

29Si and

27Al nuclei in alkali-activated slag concrete (AASC) mixtures containing different proportions of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH): 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%. These spectra provide insight into the structural evolution of the cementitious gel as a function of CLDH content and its integration into the alkali-activated matrix.

The

29Si spectra reveal that the reference mix (0% CLDH) is dominated by Q¹ and Q² units, located between –74 and –83 ppm [

26]. This distribution reflects a C–A–S–H gel structure with a low degree of polymerisation, limited connectivity between silicate tetrahedra, and greater susceptibility to carbonation. With the incorporation of 2% CLDH, Q² signals intensify and traces of Q³ (–95 ppm) appear, suggesting initial rearrangement of the silicate environment. At 4%, Q³ intensity increases significantly and Q⁴ signals (–103 to –110 ppm) emerge, indicating the development of a denser and more polymerised network. The highest level of structural development is reached at 6% CLDH, where Q³ dominates and Q⁴ is well-defined, pointing to a highly interlinked three-dimensional matrix [

27]. At 8%, these signals persist but without further improvement, suggesting a functional saturation threshold has been reached.

The 27Al spectra consistently show a strong signal near +55 ppm across all mixtures, corresponding to tetrahedrally coordinated aluminium (Al⁴⁺) integrated into the C–A–S–H or N–A–S–H gel network. As CLDH content increases up to 6%, this signal becomes more pronounced, while the signal associated with penta-coordinated aluminium (+38 ppm) decreases, indicating effective incorporation of Al released from the rehydrated CLDH. In the mix with 8% CLDH, a relative increase in the Al⁶⁺ signal at +10 ppm is observed, associated with residual phases such as MgO or spinels, suggesting incomplete CLDH rehydration and poor integration into the principal gel.

Collectively, the results shown in

Figure 3 confirm that CLDH significantly alters the molecular architecture of both silicate and aluminate gels [

28]. An optimal addition of 6% enables maximum silicate network polymerisation and efficient structural incorporation of aluminium. Below this threshold, reinforcement is progressive yet limited; above it, the system loses efficiency due to the formation of inert secondary phases. The CLDH-free sample (0%) reflects a poorly connected and less dense structure, whereas the 8% mixture exhibits signs of structural overload and chemical imbalance.

These structural transformations, evidenced by shifts and intensity changes in the MAS-NMR spectra, are directly correlated with the mechanical performance, carbonation resistance, and overall durability of the material.

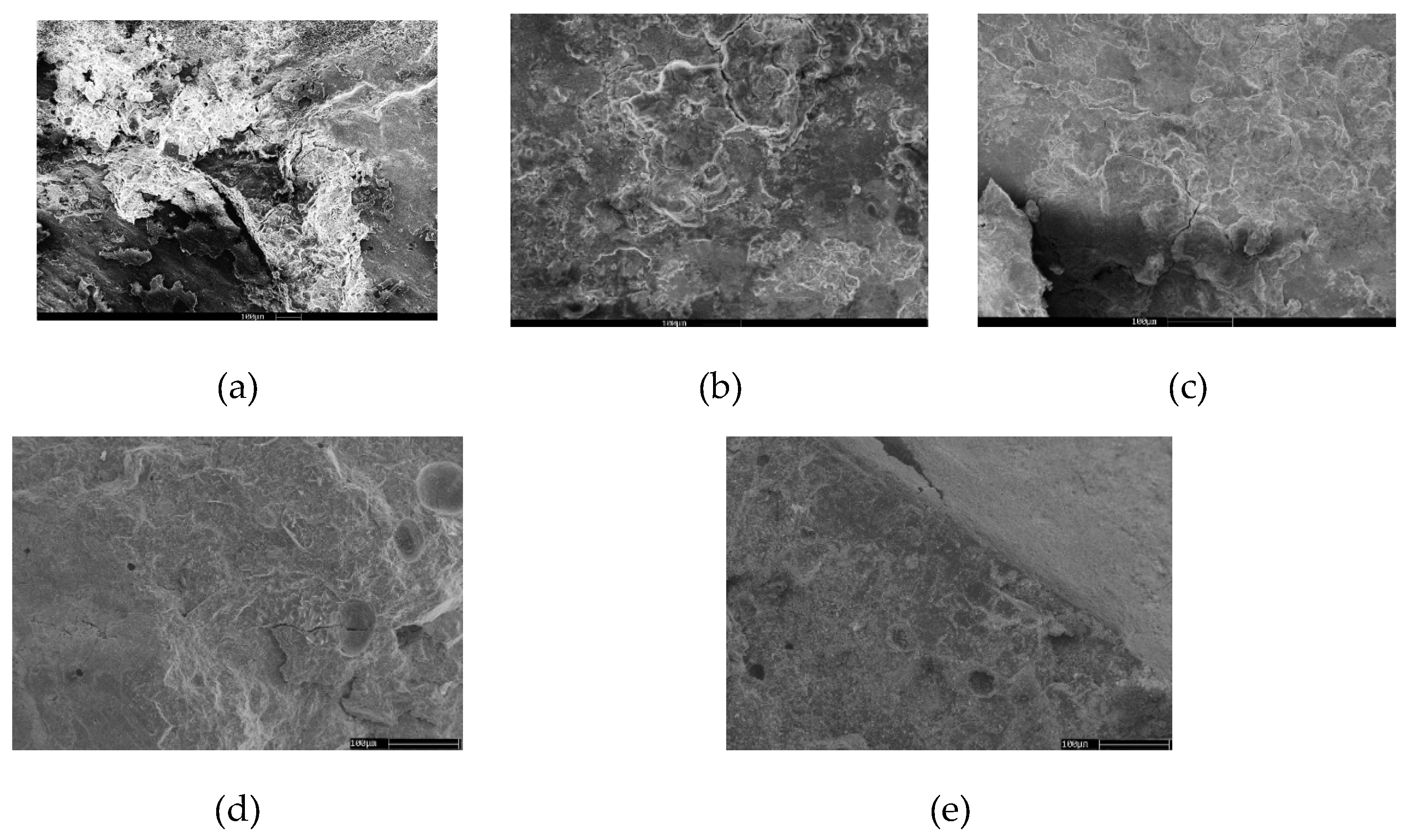

3.1.3. SEM

Figure 4 presents SEM micrographs at 1000× magnification of alkali-activated slag pastes (AASC) modified with varying proportions of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH): 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%. This analysis allows for correlation between surface morphology and matrix density with hydration dynamics, structural reorganisation, and the formation of secondary products induced by CLDH, enabling the evaluation of the additive’s efficiency in enhancing microstructural development [

29].

In the absence of CLDH (

Figure 4a, 0%), the microstructure displays a high degree of porosity, with poorly consolidated fragments, disaggregated zones, and limited C–A–S–H gel formation. This results in a heterogeneous, weakly bonded network with poor distribution of hydration products, associated with low mechanical strength and increased vulnerability to carbonation. With 2% CLDH addition (

Figure 4b), a slight improvement in densification is observed, characterised by more integrated particles and a partial reduction in visible voids [

30]. Nonetheless, discontinuous regions persist, indicating an ongoing yet still limited hydration process. At 4% CLDH (

Figure 4c), the improvement becomes more pronounced: the surface exhibits partial continuity, hydrated products of globular morphology, and overall increased compactness. This evolution suggests an effective nucleating role of restructured CLDH, promoting gel formation in previously inert zones. The most favourable condition is observed with 6% CLDH (

Figure 4d), where a homogeneous, densely packed matrix with no significant porosity is achieved [

31]. The globular hydration products are fully integrated into a continuous network, indicating an advanced degree of hydration and polymerisation. This behaviour aligns with MAS-NMR findings and corresponds to the highest mechanical strength and durability recorded for this formulation. However, with 8% CLDH (

Figure 4e), a decline in matrix continuity is evident. Although the globular morphology partially persists, isolated or poorly bonded spheres and agglomerated regions appear [

32]. This response indicates excessive additive content, leading to the formation of less reactive secondary gels or interference with complete slag hydration, negatively affecting the integration of reaction products.

The SEM analysis confirms that CLDH exerts a decisive influence on the internal microstructure of AASC pastes. A 6% dosage is identified as optimal for enhancing densification, minimizing porosity, and promoting a homogeneous, continuous matrix [

33]. In contrast, mixtures containing 0% and 8% CLDH display suboptimal microstructural configurations, which may negatively impact the durability and corrosion resistance of the material.

3.1.4. Carbonation Front Penetration under Accelerated CO₂

Carbonation depth was assessed in AASC mixtures with varying proportions of CLDH (0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%) after 87 days of accelerated exposure under controlled conditions (3% CO₂, 65% relative humidity, 25 °C). Measurement was conducted by applying a 1% alcoholic phenolphthalein solution, which turns magenta in regions with pH above 9.0 and remains colourless when the pH falls below this threshold [

34].

The mixture without CLDH (0%) exhibited a carbonation depth of 50 mm, reflecting a rapid loss of alkalinity and high susceptibility to CO₂ ingress, attributed to the absence of additional chemical buffering mechanisms.

With increasing CLDH content, a systematic reduction in carbonation depth was observed. At 2%, the carbonation front decreased to 38.2 mm, suggesting an initial improvement due to slight microstructural densification. Mixtures containing 4% and 6% CLDH demonstrated significantly enhanced performance, reaching depths of 31.2 mm and 25.4 mm, respectively [

35]. These findings indicate that CLDH serves as a dual-functional agent: it releases protective anions (OH⁻, CO₃²⁻) and enhances matrix compactness, thereby limiting CO₂ penetration.

At 8%, the additional reduction was marginal (23.7 mm), suggesting a functional saturation of the system. In this case, part of the CLDH may not rehydrate effectively and could act as an inert or dilutive filler, reducing overall efficiency.

In summary, a 6% CLDH dosage is identified as optimal, maximising carbonation resistance without compromising the system’s microstructural integrity [

36]. This result is consistent with supporting physicochemical evidence obtained from XRD and NMR analyses, where this proportion also exhibited the highest reactivity and structural stability.

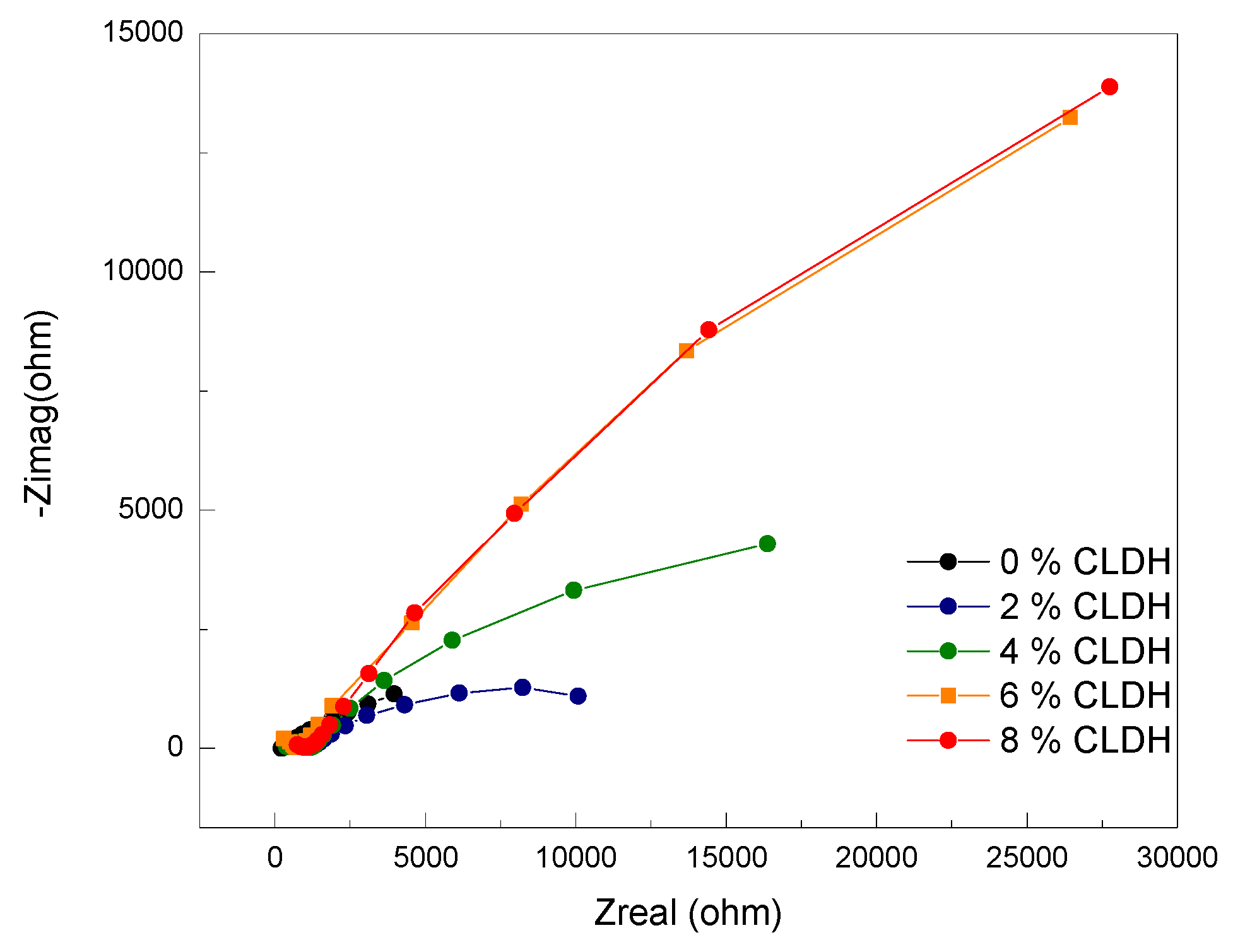

3.1.5. EIS

Figure 5 presents the Nyquist plots obtained after exposing the AASC mixtures to an accelerated carbonation process. These clearly illustrate how the progressive incorporation of calcined layered double hydroxide (CLDH) significantly alters the electrochemical response of the system. As the CLDH content increases, the diameter of the Nyquist semicircles expands accordingly, indicating a higher polarization resistance (Rp). This trend is directly associated with improved protective capacity against the corrosion of embedded steel within the alkali-activated matrix.

In the reference mixture (0% CLDH), a small semicircle is observed, with polarisation resistance (Rp) values below 6 kΩ·cm², indicating a condition of active corrosion. This behaviour aligns with a carbonation depth of 50 mm after just 87 days, suggesting a chemically degraded environment [

37]. MAS-NMR results revealed a poorly polymerised structure dominated by Q¹–Q² units, while XRD analysis showed a matrix with minimal formation of protective phases, such as hydrotalcites or well-developed gels. SEM micrographs confirmed significant porosity and discontinuous zones, which facilitated CO₂ ingress and the depassivation of the embedded steel.

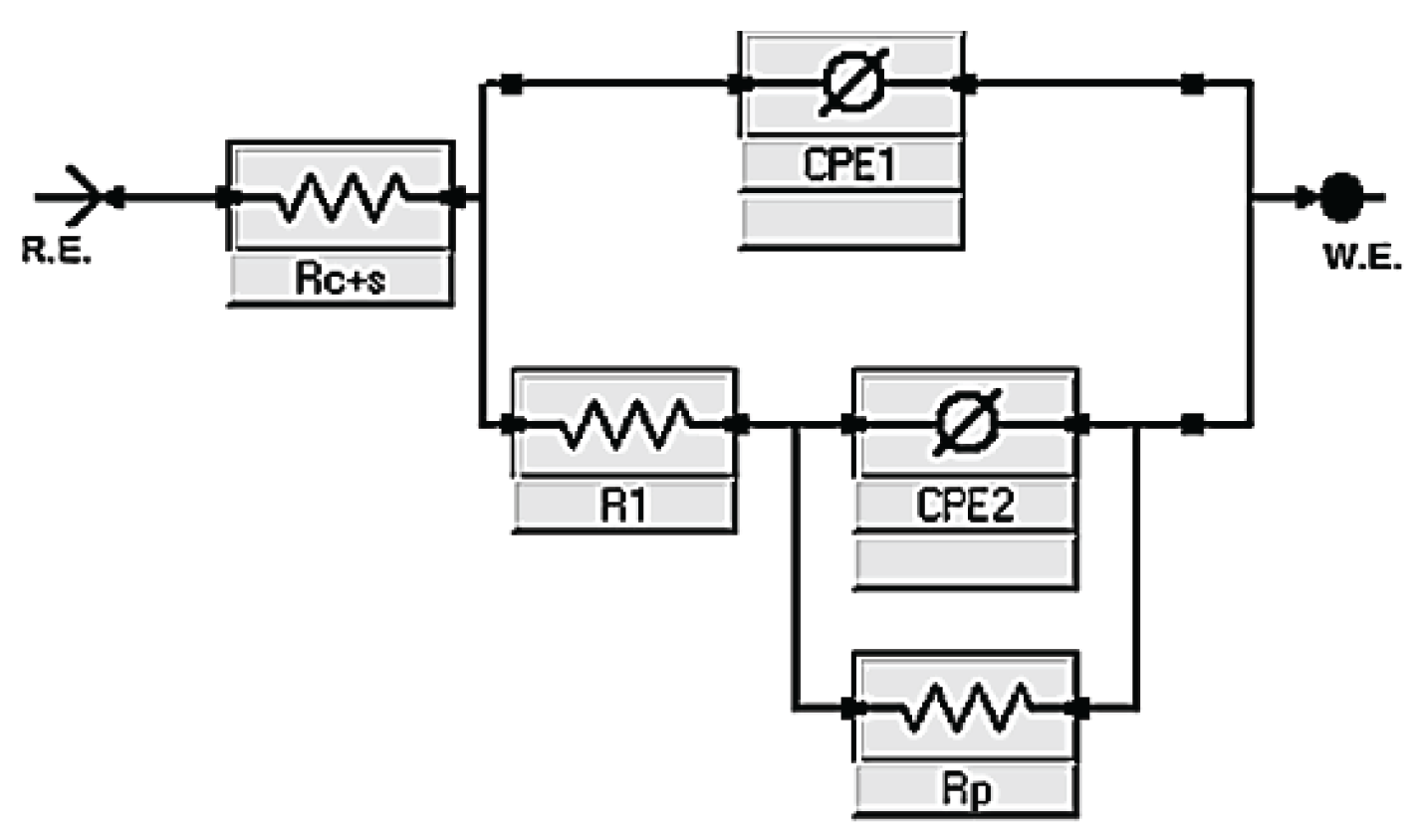

To interpret these findings, the equivalent circuit shown in

Figure 6 was employed. It comprises a solution resistance (Rₛ), two constant phase elements (CPE₁ and CPE₂), and two resistances associated with the interface and diffusion processes (R₁ and Rp). This model enabled fitting of the impedance data and the extraction of representative system parameters.

The parameters obtained from fitting the equivalent circuit reveal a clear trend with increasing CLDH content. The progressive rise in R₁ and Rp from values below 6 kΩ·cm² to over 50 kΩ·cm² in the mixture containing 6% CLDH indicates a notable enhancement in polarisation resistance. Simultaneously, the exponents n₁ and n₂ approach values near 0.9, reflecting a transition towards more ideal capacitive behaviour—typically associated with homogeneous interfaces and a dense microstructure [

38]. The reduction in C₁ and C₂ values further suggests a decrease in the system’s distributed capacitance, likely due to a reduction in structural defects and active pores.

In mixtures containing 2% and 4% CLDH, a gradual increase in Rp was observed (reaching approximately 40 kΩ·cm²) along with a delayed onset of complete carbonation (120 and 160 days, respectively). At these dosages, denser microstructures developed, featuring globular gels and fewer unreacted particles, as confirmed by SEM. MAS-NMR data showed increased gel polymerisation with the emergence of Q³ units, while XRD detected characteristic peaks of LDH phases [

39]. This structural synergy suggests a marked improvement in system durability, attributed to the “memory effect” of CLDH and its ability to release protective anions such as OH⁻ and CO₃²⁻.

The optimal content was found at 6% CLDH, where the Nyquist semicircles were largest and Rp exceeded 55 kΩ·cm², indicating a stable passive state. At this level, carbonation depth was the lowest observed. However, the 8% CLDH mix did not show any significant additional benefit. While the Nyquist semicircle was comparable to that of the 6% mix, with Rp around 56 kΩ·cm², complementary analyses indicated a slight reduction in efficiency [

39,

40]. MAS-NMR showed a decrease in the proportion of Q⁴ units, XRD revealed the presence of undesirable phases such as unreacted MgO, and SEM displayed a slight decline in compactness. This suggests that beyond 6%, CLDH acts as an inert filler, oversaturating the system without providing further improvement in carbonation resistance or electrochemical performance.

Table 2 presents the values extracted from the equivalent circuit for the various CLDH contents, allowing quantification of the additive’s effect on the system’s resistive and capacitive components.

4. Conclusions

The progressive incorporation of CLDH into AASC pastes significantly reduces the susceptibility of embedded steel to carbonation-induced corrosion. This is evidenced by the continuous increase in polarisation resistance (Rp), exceeding 55 kΩ·cm² with 6% CLDH, and the marked reduction in carbonation depth (down to 25.4 mm after 87 days of exposure).

A dosage of 6% CLDH is identified as optimal, as it results in a dense and continuous microstructure that restricts CO₂ diffusion and maintains a high pH in the vicinity of the reinforcement. This prevents depassivation and promotes a stable electrochemical passive state, as shown by the wide Nyquist semicircles.

The parameters extracted from the equivalent circuit model (notably the increase in R₁ and Rp, and n₁ and n₂ values approaching 0.9) reflect a transition towards more homogeneous and less defective interfaces, indicating reduced structural degradation and enhanced electrochemical stability under aggressive environmental conditions.

Although 8% CLDH maintains a high Rp (~56 kΩ·cm²), MAS-NMR and SEM results suggest a slight loss in structural efficiency. Residual phases such as unreacted MgO and less compact microstructures were detected, which may compromise long-term durability under advanced degradation processes.

CLDH functions not only as a physical barrier to CO₂ ingress but also as a source of protective anions (OH⁻ and CO₃²⁻) through its memory effect. This dual action enhances the system’s chemical resilience and mitigates degradation induced by carbonation agents under simulated accelerated exposure conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.A. and J.C.; methodology, W.A.; software, J.A.; validation, W.A., J.A., and J.C.; formal analysis, W.A.; investigation, W.A.; resources, J.C.; data curation, J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, W.A.; writing—review and editing, J.C.; visualization, J.A.; supervision, J.C.; project administration, J.C.; funding acquisition, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Willian Aperador acknowledges the Universidad Militar Nueva Granada.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lloyd, N.; Collins, F. G. Carbon Dioxide Equivalent (CO₂-e) Emissions: A Comparison between Geopolymer and OPC Cement Concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2013, 43, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, U.; Ali, M.; Cheema, A.; Sultan, S. M.; Akhtar, M. J. Green Cement Valuation: An Optimistic Approach to Carbon Dioxide Reduction. Journal of Applied Engineering Sciences 2023, 13, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagajothi, S.; Elavenil, S.; Angalaeswari, S.; Natrayan, L.; Mammo, W. D. Durability Studies on Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Concrete Incorporated with Slag and Alkali Solutions. Advances in Civil Engineering 2022, 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M. T. Fresh and Mechanical Characteristics of Alkali Activated Fly Ash Slag Concrete Activated with Neutral Grade Liquid Glass. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology 2023. [CrossRef]

- Luga, E.; Mustafaraj, E.; Corradi, M.; Atiş, C. D. Alkali-Activated Binders as Sustainable Alternatives to Portland Cement and Their Resistance to Saline Water. Materials 2024, 17, 4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q. D.; Castel, A. Developing Geopolymer Concrete by Using Ferronickel Slag and Ground-Granulated Blast-Furnace Slag. Ceramics 2023, 6, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán-Ramírez, R.; González-Hernández, A.; Bautista-Ruiz, J.; Ospina, M.; Aperador, W. Enhancing Concrete Durability and Strength with Fly Ash, Steel Slag, and Rice Husk Ash for Marine Environments. Materials 2024, 17, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shagñay, S.; Bautista, A.; Velasco, F.; Ramón-Álvarez, I.; Torres-Carrasco, M. Influence of the Early-Age Length Change of Alkali-Activated Slag Mortars on the Corrosion of Embedded Steel. Journal of Sustainable Cement-Based Materials 2023, 13, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behfarnia, K.; Rostami, M. An Assessment on Parameters Affecting the Carbonation of Alkali-Activated Slag Concrete. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 157, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, R.; Aperador, W.; Bastidas, D. M. Influence of Conductivity on Cathodic Protection of Reinforced Alkali-Activated Slag Mortar. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, T. Comparison of Testing Methods for Evaluating the Resistance of Alkali-Activated Blast Furnace Slag Systems to Sulfur Dioxide. Materials 2022, 15, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K. , Yongning, L., Ji, T., Lu, Y., & Lin, X. Effect of activator types and concentration of CO2 on the steel corrosion in the carbonated alkali-activated slag concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 262, 120044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Duais, I. N. A.; Ahmad, S.; Al-Osta, M. A.; Maslehuddin, M.; Ibrahim, M. M. Durability of Alkali-Activated Concrete Made Using Multiple Precursors as Primary Binders. Journal of Sustainable Cement-Based Materials 2024, 13, 1483–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Li, W.G.; Ruan, C.K.; Sagoe-Crentsil, K.; Duan, W.H. Pore shape analysis using centrifuge driven metal intrusion: Indication on porosimetry equations, hydration and packing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 154, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. , Xiong, X., Wang, D., Zhou, X., & Xu, Z. (2024). The Risk of Alkali–Carbonate Reaction and the Freeze–Thaw Resistance of Waste Dolomite Slag-Based Concrete. Buildings. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Xie, X. S.; Xu, J. Study on the Macroscopic Properties and Microstructure of High Fly Ash Content Alkali-Activated Fly Ash Slag Concrete Cured at Room Temperature. Materials 2025, 18, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Zhao, G.; Quan, X.; Liu, X.; Bu, M. Investigation on the Sodium Silicate Modulus-Affected Macroscopic and Microscopic Characteristics of Alkali-Activated Slag Concrete. Materials Science and Technology 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kaliyavaradhan, S. K. , Unnikrishnan, A. K., & Ambily, P. S. (2024). CO 2 sequestration through alkali-activated steel slag: a review. Journal of Sustainable Cement-Based Materials. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-J.; Hua, C.; Fazeldehkordi, L.; Shyu, W.-S. Exploring the Potential and Strength Characteristics of Waste Sodium Silicate-Bonded Sand for Sustainable Application in Alkali-Activated Slag Concrete. Journal of Sustainable Cement-Based Materials 2024, 14, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M. A.; Ojala, T.; Al-Neshawy, F.; Punkki, J. Effect of Slag Content and Carbonation/Ageing on Freeze–Thaw Resistance of Concrete. Nordic Concrete Research 2024, 71, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. ASTM C33/C33M–18: Standard specification for concrete aggregates. West Conshohocken (PA): ASTM International; 2018. Available from: https://www.astm.org/c0033_c0033m-18.

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Shi, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Jia, X.; Ren, Q.; Jiang, Z. Early Hydration and Microstructure Formation of Ultra-Rapid Hardening Alkali-Activated Slag Cement (URHA) in the Presence of MgO. SSRN 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pavel, O. D.; Manyar, H. Editorial: Layered Double Hydroxides and Their Use as Catalysts in Sustainable Processes. Frontiers in Chemical Engineering 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Zambrano, S.; Ramos-Ramirez, E. E.; Tzompantzi, F.; Gutiérrez Ortega, N. L. A XRD Study of the CuAl Layered Double Hydroxide Synthesis Evolution. Materials and Devices 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, M.; Aperador, W.; Sobrados, I. Microstructural and Mechanical Properties of Alkali-Activated Colombian Raw Materials. Materials 2016, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, B.; Thom, N. Effects of Alkali Dosage and Silicate Modulus on Autogenous Shrinkage of Alkali-Activated Slag Cement Paste. Cement and Concrete Research 2021, 140, 106322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, M. Micromechanical Analysis of Interfacial Transition Zone in Alkali-Activated Fly Ash-Slag Concrete. Cement and Concrete Composites 2021, 119, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisková, L.; Ducman, V.; Lončar, M.; Tesovnik, A.; Žibret, G.; Skentzou, D.; Georgopoulos, C. Alkali-Activated Mineral Residues in Construction: Case Studies on Bauxite Residue and Steel Slag Pavement Tiles. Materials 2025, 18, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Darquennes, A.; Hannawi, K.; Che, C. Effect of the Alkali-Sulphate Activators on the Hydration Process of Blast-Furnace Slag Mortars and Pastes. Materials 2025, 18, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Cai, L.; Chi, F.; Zhan, W. Impact of Metakaolin to Partially Replace Granulated Blast Furnace Slag on the Performance of Alkali-Activated Slag Grouting Materials and Evaluation of Grouting Effectiveness. Materials Research Express 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li-li, W.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, J. Study on the Inhibition Effect of Fly Ash on Alkali–Silica Reaction and Its Influence on Building Energy Performance. Buildings 2025, 15, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L. , Sun, S. ( 2025.

- Mechanism of chloride binding in alkali-activated materials exposed to combined chloride, sulfate and carbonation environment. Journal of Sustainable Cement-Based Materials. [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Ye, D.; Song, Y.-M.; Yuan, C.; Guan, J.; Yang, G.; Xie, C. Study on Mechanical Properties and Damage Mechanism of Alkali-Activated Slag Concrete. Journal of Building Engineering 2024, 110357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulubeyli, G. Ç.; Artır, R. Synthesis and Characterization of an Alkali-Activated Binder from Blast Furnace Slag and Marble Waste. Materials 2024, 17, 5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, N.; Hallet, V.; Peys, A.; Pontikes, Y. Degradation of Alkali-Activated Fe-Rich Slag in Magnesium Sulfate Solution. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Huang, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, H. A Review on Research Progress of Corrosion Resistance of Alkali-Activated Slag Cement Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Compressive Strength and Resistance to Sulphate Attack of Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag, Lithium Slag, and Steel Slag Alkali-Activated Materials. Buildings 2024, 14, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aperador, W.; Bautista-Ruiz, J.; Sánchez-Molina, J. Effect of Immersion Time in Chloride Solution on the Properties of Structural Rebar Embedded in Alkali-Activated Slag Concrete. Metals 2022, 12, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, G.; Liu, G.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, P.; Su, Y. Study on Impact Resistance of Alkali-Activated Slag Cementitious Material with Steel Fiber. Buildings 2024, 14, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes with varying proportions of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH) as partial slag replacement (0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%).

Figure 1.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes with varying proportions of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH) as partial slag replacement (0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%).

Figure 2.

29Si MAS-NMR spectra of alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes with varying contents of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH): 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%.

Figure 2.

29Si MAS-NMR spectra of alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes with varying contents of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH): 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%.

Figure 3.

27Al MAS-NMR spectra of alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes with varying proportions of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH): 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%.

Figure 3.

27Al MAS-NMR spectra of alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes with varying proportions of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH): 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of the fractured surface of alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes with varying contents of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH): (a) 0%, (b) 2%, (c) 4%, (d) 6%, and (e) 8%.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of the fractured surface of alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes with varying contents of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH): (a) 0%, (b) 2%, (c) 4%, (d) 6%, and (e) 8%.

Figure 5.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) Nyquist plots for alkali-activated slag (AAS) concretes with varying proportions of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH): 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%.

Figure 5.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) Nyquist plots for alkali-activated slag (AAS) concretes with varying proportions of calcined layered double hydroxides (CLDH): 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%.

Figure 6.

Proposed equivalent circuit used to fit the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) spectra for alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes containing CLDH, comprising resistive elements (Rc+s, R₁, Rp) and constant phase elements (CPE₁, CPE₂) representing transport and polarization processes.

Figure 6.

Proposed equivalent circuit used to fit the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) spectra for alkali-activated slag (AAS) pastes containing CLDH, comprising resistive elements (Rc+s, R₁, Rp) and constant phase elements (CPE₁, CPE₂) representing transport and polarization processes.

Table 2.

Parameters extracted from the equivalent electrical circuit model for AASC mixtures with varying CLDH contents, including solution resistance (Rc+s), interface resistance (R1), polarization resistance (Rp), and constant phase elements (CPE1 and CPE2).

Table 2.

Parameters extracted from the equivalent electrical circuit model for AASC mixtures with varying CLDH contents, including solution resistance (Rc+s), interface resistance (R1), polarization resistance (Rp), and constant phase elements (CPE1 and CPE2).

| Material |

Rc+s

Ω cm2

|

R1

Ω cm2

|

CPE1

μF cm−2

|

n1

|

Rp

Ω cm2

|

CPe2

μF cm−2

|

n2

|

| 0% CLDH |

5 |

511 |

55 |

0.85 |

6511 |

452 |

0.74 |

| 2% CLDH |

15 |

1320 |

83 |

0.82 |

14930 |

934 |

0.79 |

| 4% CLDH |

21 |

2456 |

40 |

0.88 |

39215 |

710 |

0.84 |

| 6% CLDH |

32 |

9564 |

32 |

0.92 |

55194 |

658 |

0.89 |

| 8% CLDH |

45 |

12541 |

36 |

0.91 |

56650 |

645 |

0.94 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).