Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

31 August 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

Discussion

Materials and Methods

- 1.

- Cell Viability Assay

- 2.

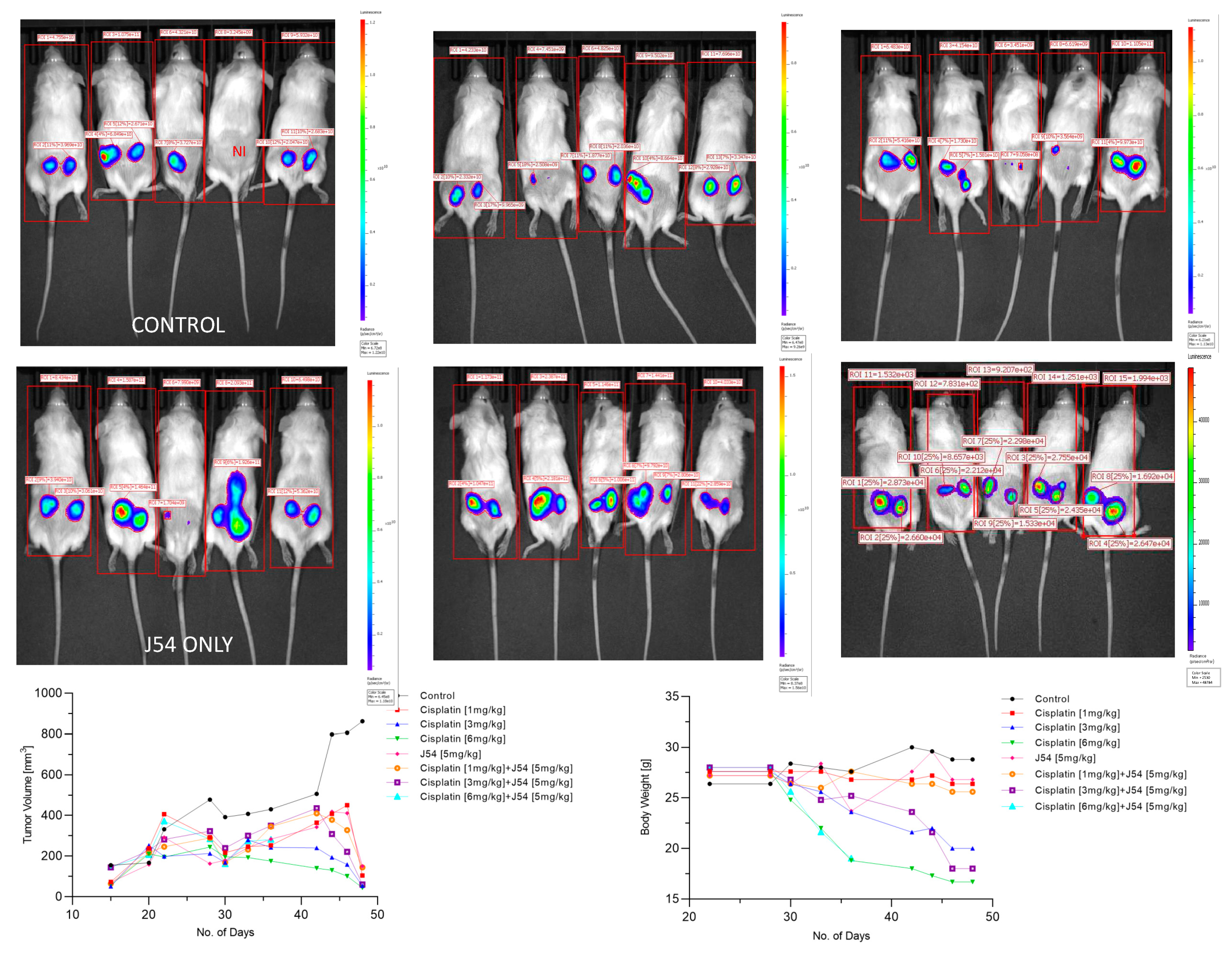

- Animal Studies

- 3.

-

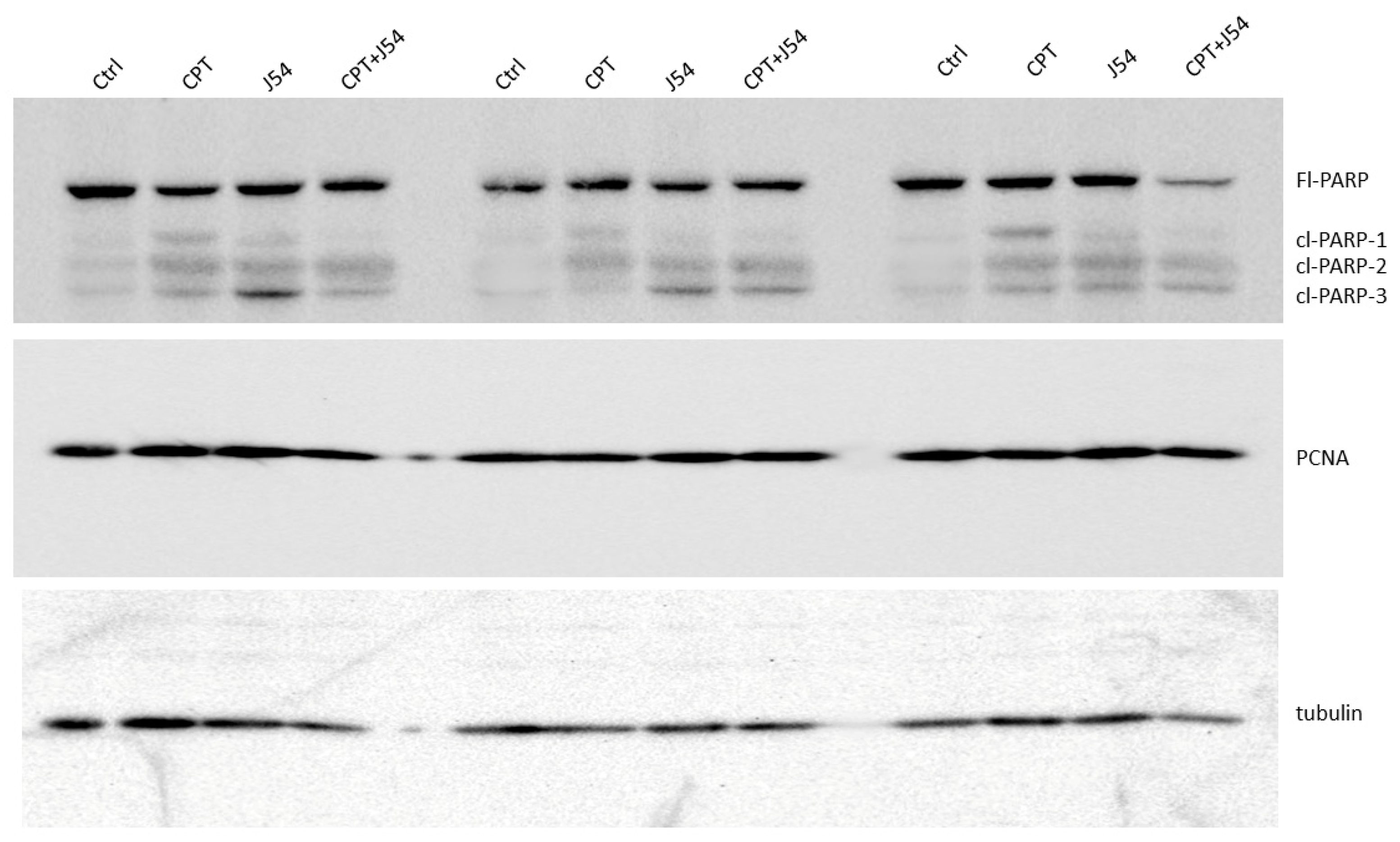

Western Blots

- Tissue Western Blot: Western blots were performed in three biological replicates for the tumors excised from the different treatment groups, including control (PBS), cisplatin (3mg/kg), J54 (5mg/kg) and the combination of the PC-3 grafted NOD SCID mice. The frozen tumor tissues were disrupted with the Bioruptor® Plus sonication device (Diagenode; Cat. No. B01020001), homogenized, and lyzed in the ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Cat. No. SC-24948). The samples were clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 mins in the refrigerated setting. The supernatant was collected, transferred into fresh 1.5 ml microfuge tubes, flash-frozen, and stored at -800C until further use. The total protein concentration was measured using a Pierce™ BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific; Cat. No. 23225) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard control. An equal loading amount of 15 µg was calculated for each protein sample. The sample supernatant was denatured with 1X Laemmli Buffer for 10 mins at 950C and separated using 12% Mini PROTEAN TGX protein gel (BioRad; Cat. No. 4568084) at 100 volts for 120 mins. The proteins were transferred to the Immun-Blot PVDF membrane (BioRad; Cat. No. 1620177) using a Mini Trans-Blot Cell (BioRad; Cat. No. 1703930) at 100 volts for 150-180 mins on ice. The membrane was blocked with 5% Non-fat dry milk (Cell Signaling Technology; Cat. No. 9999S) in 1X Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 hour at room temperature. Following blocking, the membrane was washed once with 1X TBST and incubated with mouse anti-PCNA (PC10) monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Cat. No. SC-56; 1:1000 dilution) and mouse anti-PARP-1 (F-2) monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Cat. No. SC-8007; 1:1000 dilution) in 5% BSA in 1X TBST overnight at 40C with gentle rocking. The next day, after washing four times with 1X TBST, the membrane was incubated with horse anti-mouse antibody (Cell Signaling Technology; Cat. No. 7076S: 1:2000 dilution) labeled with horseradish peroxidase in 5% BSA in 1X TBST for 1-1.5 hours at room temperature. After incubation, the membrane was washed four times with 1X TBST, and the reactive bands were detected using Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific; Cat. No. 32106) on ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (BioRad; Cat. No. 12003154).

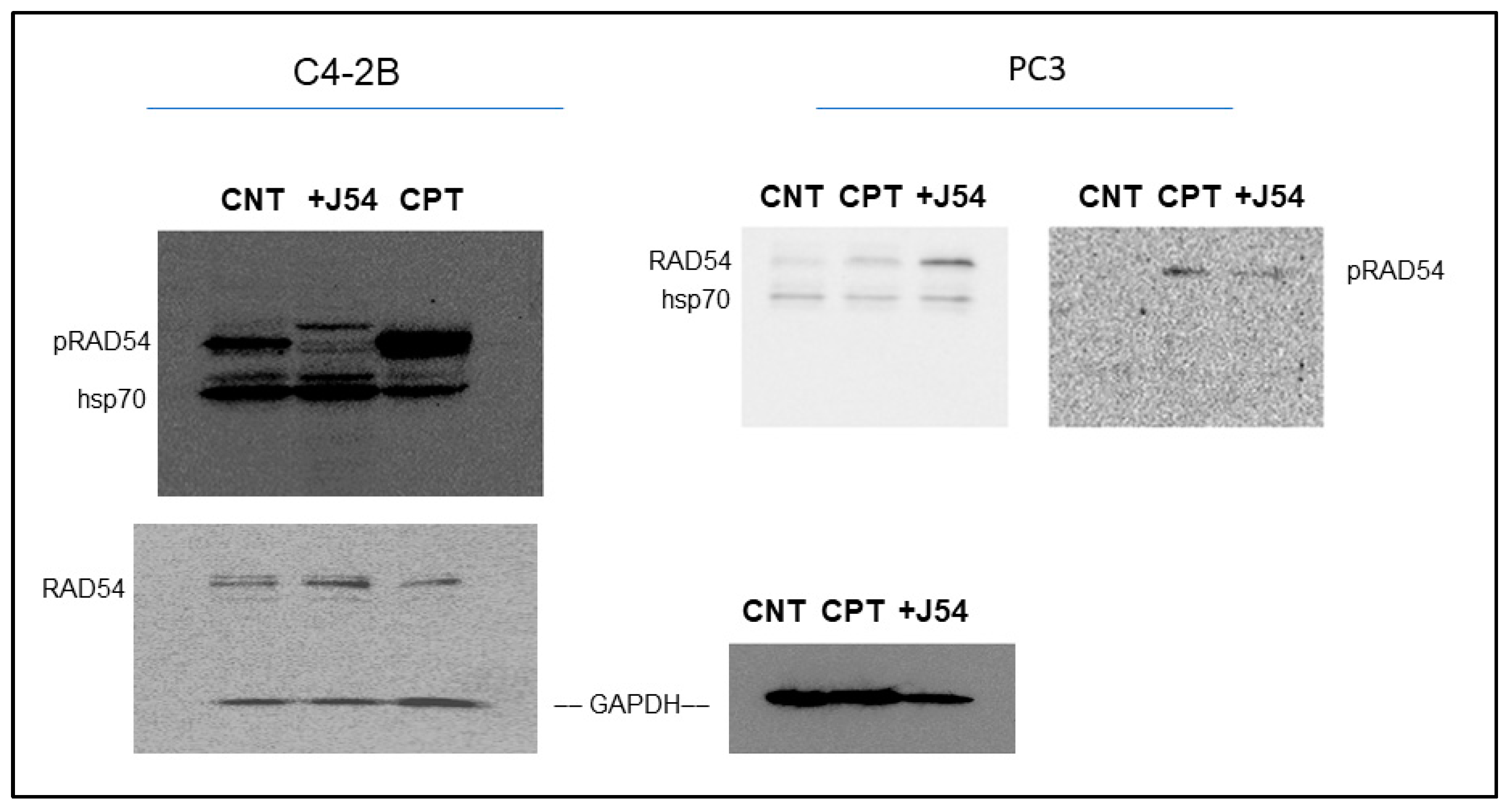

- Cell Western Blot: The western blot for PC-3 cells was performed as described above but with minor modifications. Briefly, 3*106 PC-3 cells (control and drug-treated) were collected, washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and lyzed with RIPA lysis buffer system. The lysate was vortexed and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min to remove cell debris. The total protein was estimated, and 30 μg of the cell lysate was loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel. The separated proteins were transferred to the membrane using a wet transfer apparatus. The complete transfer was ensured by checking the membrane for uniform background staining. The membrane was then incubated in a blocking solution (e.g., 5% non-fat milk in TBST) for 1 h at room temperature to block non-specific binding sites, followed by primary antibody (custom-made anti-pRAD54 rabbit polyclonal; Thermo Scientific; Cat. No. AB1991; 1:1000) incubation in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. The next day, the membrane was washed 3X with TBST for 10 min each to remove excess primary antibody. Further, it was incubated with goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody diluted in a blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature. Next, the membrane was washed 3X with TBST for 10 min each to remove excess secondary antibody, and the bands were detected using the ECL chemiluminescent substrate.

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

IACUC approval

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chatterjee, N.; Walker, G.C. Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environ Mol Mutagen 2017, 58, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, K.A.; Michelson, R.J.; Putnam, C.W.; Weinert, T.A. Toward maintaining the genome: DNA damage and replication checkpoints. Annu Rev Genet 2002, 36, 617–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setton, J.; Zinda, M.; Riaz, N.; Durocher, D.; Zimmermann, M.; Koehler, M.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Powell, S.N. Synthetic lethality in cancer therapeutics: the next generation. Cancer Discov 2021, 11, 1626–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abida, W.; Campbell, D.; Patnaik, A.; Shapiro, J.D.; Sautois, B.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Voog, E.G.; Bryce, A.H.; McDermott, R.; Ricci, F.; et al. Non-BRCA DNA Damage Repair Gene Alterations and Response to the PARP Inhibitor Rucaparib in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Analysis From the Phase II TRITON2 Study. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26, 2487–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bono, J.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujino, T.; Takai, T.; Hinohara, K.; Gui, F.; Tsutsumi, T.; Bai, X.; Miao, C.; Feng, C.; Gui, B.; Sztupinszki, Z.; et al. CRISPR screens reveal genetic determinants of PARP inhibitor sensitivity and resistance in prostate cancer. BioRxiv 2022, Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.N.; Ashton, N.W.; Paquet, N.; O’Byrne, K.; Richard, D.J. Mechanisms of cisplatin resistance: DNA repair and cellular implications. In Advances in Drug Resistance Research, Morais, C., Ed. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: 2014; pp. 1-37.

- Kiss, R.C.; Xia, F.; Acklin, S. Targeting DNA damage response and repair to enhance therapeutic index in cisplatin-based cancer treatment. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickoloff, J.A.; Jones, D.; Lee, S.H.; Williamson, E.A.; Hromas, R. Drugging the Cancers Addicted to DNA Repair. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, S.; Omlin, A.; Higano, C. Activity of platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced prostate cancer with and without DNA repair gene aberrations (vol 3, e2021692, 2020). Jama Network Open 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccaldi, R.; Sarangi, P.; D'Andrea, A.D. The Fanconi anaemia pathway: new players and new functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016, 17, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, S.; Anai, H.; Hanada, K. Mechanisms of interstrand DNA crosslink repair and human disorders. Genes Environ 2016, 38, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Michels, J.; Brenner, C.; Szabadkai, G.; Harel-Bellan, A.; Castedo, M.; Kroemer, G. Systems biology of cisplatin resistance: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis 2014, 5, e1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, C.; Albers, P. Testicular germ cell tumors: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011, 7, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perše, M. Cisplatin Mouse Models: Treatment, Toxicity and Translatability. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, C.R.R.; Silva, M.M.; Quinet, A.; Cabral-Neto, J.B.; Menck, C.F.M. DNA repair pathways and cisplatin resistance: an intimate relationship. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2018, 73, e478s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, S.; Gu, F.X.; Langer, R.; Farokhzad, O.C.; Lippard, S.J. Targeted delivery of cisplatin to prostate cancer cells by aptamer functionalized Pt(IV) prodrug-PLGA-PEG nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 17356–17361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selemenakis, P.; Sharma, N.; Uhrig, M.E.; Katz, J.; Kwon, Y.; Sung, P.; Wiese, C. RAD51AP1 and RAD54L Can Underpin Two Distinct RAD51-Dependent Routes of DNA Damage Repair via Homologous Recombination. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, J.M.; Barnett, E.; Nauseef, J.T.; Nguyen, B.; Stopsack, K.H.; Wibmer, A.; Flynn, J.R.; Heller, G.; Danila, D.C.; Rathkopf, D.; et al. Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer With DNA Repair Gene Alterations. JCO Precis Oncol 2020, 10.1200/po.19.00346, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, S.; Omlin, A.; Higano, C.; Sweeney, C.; Martinez Chanza, N.; Mehra, N.; Kuppen, M.C.P.; Beltran, H.; Conteduca, V.; Vargas Pivato de Almeida, D.; et al. Activity of Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Patients With Advanced Prostate Cancer With and Without DNA Repair Gene Aberrations. JAMA network open 2020, 3, e2021692–e2021692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillje, H.H.; Takahashi, K.; Tanaka, K.; Van Houwe, G.; Nigg, E.A. Mammalian homologues of the plant Tousled gene code for cell-cycle-regulated kinases with maximal activities linked to ongoing DNA replication. Embo J 1999, 18, 5691–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Jaiswal, P.K.; Ghosh, I.; Koul, H.K.; Yu, X.; De Benedetti, A. The TLK1-Nek1 axis promotes prostate cancer progression. Cancer Lett 2019, 453, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunavala-Dossabhoy, G.; Fowler, M.; De Benedetti, A. Translation of the radioresistance kinase TLK1B is induced by gamma-irradiation through activation of mTOR and phosphorylation of 4E-BP1. Bmc Molecular Biology 2004, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, A.; Lukas, J.; Nigg, E.A.; Sillje, H.H.; Wernstedt, C.; Bartek, J.; Hansen, K. Human Tousled like kinases are targeted by an ATM- and Chk1-dependent DNA damage checkpoint. Embo J 2003, 22, 1676–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; DeFatta, R.; Anthony, C.; Sunavala, G.; De Benedetti, A. A translationally regulated Tousled kinase phosphorylates histone H3 and confers radioresistance when overexpressed. Oncogene 2001, 20, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.P.; De Benedetti, A. TLK1B promotes repair of UV-damaged DNA through chromatin remodeling by Asf1. BMC Mol Biol 2006, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, Y.; Kokuryo, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Ito, S.; Nagino, M.; Hamaguchi, M.; Senga, T. Silencing of Tousled-like kinase 1 sensitizes cholangiocarcinoma cells to cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Cancer Lett 2010, 296, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, I.; Kwon, Y.; Shabestari, A.B.; Chikhale, R.; Chen, J.; Wiese, C.; Sung, P.; De Benedetti, A. TLK1-mediated RAD54 phosphorylation spatio-temporally regulates Homologous Recombination Repair. Nucleic Acids Research 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyer, W.-D.; Li, X.; Rolfsmeier, M.; Zhang, X.-P. Rad54: the Swiss Army knife of homologous recombination? Nucleic Acids Research 2006, 34, 4115–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Bhoir, S.; Chikhale, R.V.; Hussain, J.; Dwyer, D.; Bryce, R.A.; Kirubakaran, S.; De Benedetti, A. Generation of Phenothiazine with Potent Anti-TLK1 Activity for Prostate Cancer Therapy. iScience 2020, 23, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castri, P.; Lee, Y.J.; Ponzio, T.; Maric, D.; Spatz, M.; Bembry, J.; Hallenbeck, J. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 and its cleavage products differentially modulate cellular protection through NF-kappaB-dependent signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1843, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los, M.; Mozoluk, M.; Ferrari, D.; Stepczynska, A.; Stroh, C.; Renz, A.; Herceg, Z.; Wang, Z.Q.; Schulze-Osthoff, K. Activation and caspase-mediated inhibition of PARP: a molecular switch between fibroblast necrosis and apoptosis in death receptor signaling. Mol Biol Cell 2002, 13, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald, S.; Awate, S.; Rath, A.; Carroll, J.; Galiano, F.; Dwyer, D.; Kleiner-Hancock, H.; Mathis, J.M.; Vigod, S.; De Benedetti, A. Phenothiazine Inhibitors of TLKs Affect Double-Strand Break Repair and DNA Damage Response Recovery and Potentiate Tumor Killing with Radiomimetic Therapy. Genes Cancer 2013, 4, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Jaiswal, P.K.; Ghosh, I.; Koul, H.K.; Yu, X.; De Benedetti, A. Targeting the TLK1/NEK1 DDR axis with Thioridazine suppresses outgrowth of androgen independent prostate tumors. International journal of cancer 2019, 145, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, M.; Montemorano, L.; Bixel, K. PARP Inhibitors in Gynecologic Cancers: What Is the Next Big Development? Curr Oncol Rep 2020, 22, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan Geethakumari, P.; Schiewer, M.J.; Knudsen, K.E.; Kelly, W.K. PARP Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2017, 18, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stopsack, K.H. Efficacy of PARP Inhibition in Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer is Very Different with Non-BRCA DNA Repair Alterations: Reconstructing Prespecified Endpoints for Cohort B from the Phase 3 PROfound Trial of Olaparib. Eur Urol 2021, 79, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teyssonneau, D.; Margot, H.; Cabart, M.; Anonnay, M.; Sargos, P.; Vuong, N.-S.; Soubeyran, I.; Sevenet, N.; Roubaud, G. Prostate cancer and PARP inhibitors: progress and challenges. J Hematol Oncol 2021, 14, 51–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothkamm, K.; Löbrich, M. Misrepair of radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks and its relevance for tumorigenesis and cancer treatment (review). Int J Oncol 2002, 21, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhoir, S.; De Benedetti, A. Targeting Prostate Cancer, the ‘Tousled Way&rsquo. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 11100. [Google Scholar]

- Gumulec, J.; Balvan, J.; Sztalmachova, M.; Raudenska, M.; Dvorakova, V.; Knopfova, L.; Polanska, H.; Hudcova, K.; Ruttkay-Nedecky, B.; Babula, P.; et al. Cisplatin-resistant prostate cancer model: Differences in antioxidant system, apoptosis and cell cycle. Int J Oncol 2014, 44, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.I.; De Benedetti, A. Tousled-like kinase 1: a novel factor with multifaceted role in mCRPC progression and development of therapy resistance. Cancer Drug Resistance 2022, 5, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, I.; De benedetti, A. Untousling the Role of Tousled like Kinase 1 in DNA Damage Repair. In Preprints, Preprints: 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nieman, K.M.; Romero, I.L.; Van Houten, B.; Lengyel, E. Adipose tissue and adipocytes support tumorigenesis and metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1831, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carli, M.; Kolachalam, S.; Longoni, B.; Pintaudi, A.; Baldini, M.; Aringhieri, S.; Fasciani, I.; Annibale, P.; Maggio, R.; Scarselli, M. Atypical Antipsychotics and Metabolic Syndrome: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Differences. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayabandara, M.; Hanwella, R.; Ratnatunga, S.; Seneviratne, S.; Suraweera, C.; de Silva, V.A. Antipsychotic-associated weight gain: management strategies and impact on treatment adherence. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2017, 13, 2231–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).