Introduction

Metabolic disturbances, such as insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, have been linked to an increased risk of developing vascular disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases in later life. These conditions can disrupt normal metabolic processes, leading to chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular damage. The connection between metabolic disturbances and disease development is thought to be mediated by various molecular mechanisms, including epigenetic changes, impaired cellular signaling pathways, and alterations in gene expression [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Therefore, early identification and management of metabolic disturbances are crucial for preventing or delaying the onset of these diseases. Metabolic syndrome is also linked to an increased risk of certain cancers, including colon adenomas, colorecta cancer, non-alcoholic liver disease and liver cancer. Metabolic disorders, including insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction are implicated in the development and progression of neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. Established obesity-related cancer are defined as those for which the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has concluded that there is sufficient evidence linking them to obesity, including cancers of the esophagus ( adenocarcinoma) gastric (cardia), and colon. Recent research has proposed a novel concept,-that AD as “type-3 diabetes” highlighting the critical role of insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism as the common pathogenesis of these two diseases[

12].

Meticulous research conducted by the Framingham Heart Study group, established risk factors for the development of coronary artery disease [

13]. The INTERHEART study found that nine easily measurable modifiable risk factors could explain more than 90 percent, the risk of heart attack globally, in all geographical regions and major ethnic groups [

14]. They concluded that management of modifiable risk factors will have the potential to prevent most premature myocardial infarctions. Khera and associates from Harvard University, demonstrated that among participants, even with high genetic risk, a favorable lifestyle was associated with a nearly 50% lower relative risk of coronary artery disease [

15]. According to a report from the researchers of the Imperial College London, Cardiovascular mortality has declined, and diabetes mortality has increased in high-income countries [

16]. It’s encouraging to note, that death due to cardiovascular disease has decreased by two thirds in industrial nations over the past 60 years. According to various studies, the reduction in cardiovascular mortality can be attributed to improvements in medical care, lifestyle changes, and advancements in disease prevention and treatment. The decrease is also linked to increased awareness and education about heart health, as well as the implementation of public health initiatives aimed at reducing risk factors such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking [

17]. Death rates from cancer on the other hand, have hardly reduced in the more than fifty years since the War on Cancer was declared.

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon in 1971, aimed to eliminate cancer as a major health threat by the end of the 20th century. Despite significant advances in cancer research and treatment, death rates from cancer have not decreased substantially over the past five decades. In fact, according to the American Cancer Society, cancer remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide, with over 18 million new cases and 9.6 million cancer-related deaths reported in 2020 alone. This suggests that the war on cancer has yet to be won [

18]. Cancer is developed from a normal healthy cell, a disease that is endogenous, and therefore the aim should be better management than to cure. According to the experts, it is more realistic to treat cancer as one of the chronic, manageable diseases [

18]. There is worldwide effort to shift the public health policies towards prevention than curing. Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the USA right behind heart disease. Then why is there such a difference in the management of these two diseases?

The difference between the management of these two diseases is that we understand the metabolic risks that initiate and contribute to the progression of metabolic diseases such as hypertension, obesity, type-2 diabetes and vascular diseases. Therefore, we have come up with robust management of the modifiable risk factors associated with vascular diseases [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

In contrast, cancer remains a multifaceted disease with numerous subtypes, each with distinct genetic and environmental risk factors. While certain modifiable risks like smoking, diet, and environmental carcinogens are recognized, cancer’s initiation and progression are often influenced by genetic mutations and complex cellular interactions, making prevention and management more challenging. Cancer arises from genetic mutations, environmental factors, and lifestyle influences, making it harder to pinpoint universal preventive strategies. While screening programs exist for some cancers (e.g., mammograms for breast cancer, colonoscopies for colorectal cancer), many cancers remain undiagnosed until later stages. Unlike CVD, where long-term medication use can manage symptoms effectively, cancer therapies (chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy) often face challenges like drug resistance and recurrence. Cancer treatment increasingly relies on targeted therapies based on individual genetic profiles, making management more specialized and costly. Increasing awareness of lifestyle-related cancer risks and promoting healthier habits could help reduce incidence rates. Investing in better screening technologies and biomarkers can lead to earlier diagnosis and better outcomes. Just as CVD patients benefit from multidisciplinary care, cancer patients could receive more integrated support, including metabolic health monitoring. Utilizing genetic and metabolic profiling may help identify individuals at higher risk, enabling more targeted preventive measures.

In a recent article we reviewed, ‘Cardiometabolic Diseases; Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms’ [

10]. In this article, we briefly review the importance of early diagnosis, challenges related to the early diagnosis, types of cancers, unique characteristics, early origin of cancer, role of microenvironment, advance imaging and biomarker assays and treatment options.

Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer

Cancer is primarily a disease caused by cellular, genetic and tissue organization dysregulation [

24]. Understanding the molecular and cellular mechanisms driving cancer progression is essential for developing targeted therapies that selectively attack cancer cells while minimizing harm to normal cells. Cancer arises when normal cells undergo genetic and epigenetic alterations, disrupting cellular homeostasis and leading to tumor formation, invasion, and metastasis. Genetic mutations play a key role in cancer development by driving uncontrolled cell growth and division.[

25]. Oncogenes, such as

RAS, MYC, and HER2, are mutated or overexpressed genes that enhance cell proliferation and survival. In contrast, tumor suppressor genes like

TP53, RB1, and BRCA1/2 normally regulate cell division and promote apoptosis (programmed cell death)[

26]. Loss-of-function mutations in these genes impair DNA repair, apoptosis, and cell cycle control, contributing to cancer progression. Additionally, defects in DNA repair genes such as

MLH1 and MSH2 lead to genomic instability and an accumulation of mutations [

27].

Epigenetic alterations also play a significant role in cancer by modifying gene expression without changing the DNA sequence [

28].

Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes silences their protective functions, whereas

hypomethylation of oncogenes increases their expression, promoting uncontrolled proliferation [

29]. Dysregulation of microRNAs (miRNAs) can either promote or suppress cancer growth [

30]. Moreover, mutations affecting key cell cycle regulators such as

cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), cyclins, and P53 allow cancer cells to bypass checkpoints (G1/S and G2/M), resulting in unrestricted cell division. Cancer cells evade programmed cell death by overexpressing anti-apoptotic proteins like

BCL-2 or downregulating pro-apoptotic factors such as

BAX and caspases[

31]. Mutations in

TP53 further disrupt apoptosis pathways, allowing damaged cells to survive. To sustain their rapid growth, cancer cells require an ample blood supply for oxygen, glucose and other nutrients. They achieve this by secreting

vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to stimulate new blood vessel formation, which assures substrates for energy and metabolic needs [

32].

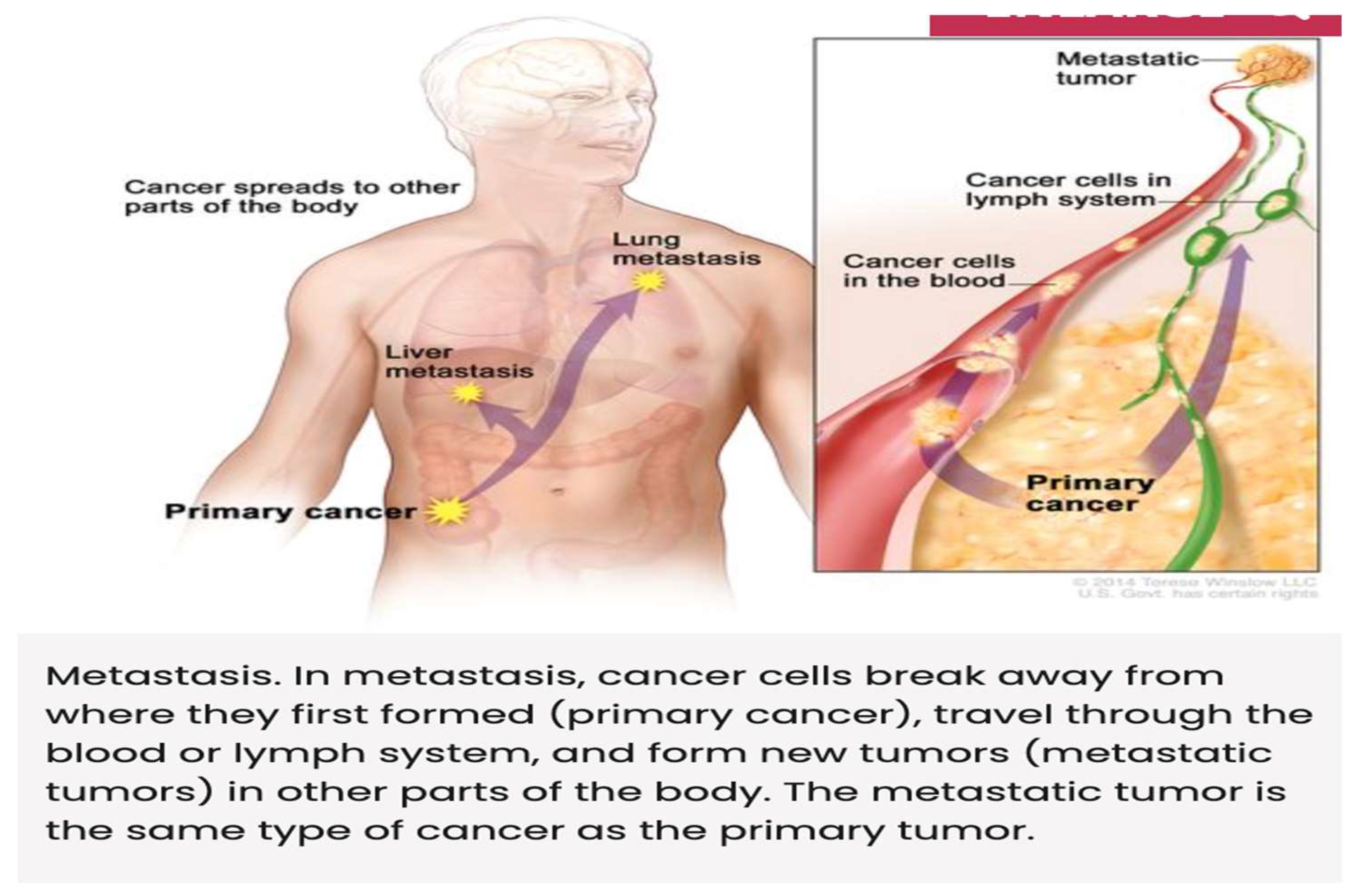

Metastasis, the spread of cancer to other tissues, occurs through

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process in which tumor cells lose adhesion and gain invasive properties. Key players in EMT include

matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), downregulation of E-cadherin, and integrins. [

33,

34] Additionally, cancer cells evade immune destruction by upregulating immune checkpoint proteins like

PD-L1 and CTLA-4, which inhibit T-cell activity, and by recruiting immunosuppressive cells such as

regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)[

35]. Cancer cells also alter their metabolism, switching to

aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect)—favoring glucose fermentation even in the presence of oxygen—to meet their biosynthetic and energy demands [

36,

37]. Understanding these cellular and molecular mechanisms is critical for developing targeted therapies, including

immunotherapy, small-molecule inhibitors, and gene therapy, to effectively combat cancer [

38,

39,

40]

Signal transduction pathways regulate various cellular processes, including growth, differentiation, and survival. In cancer, these pathways are often dysregulated, leading to aberrant cell behavior [

41,

42,

43]. For example, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is frequently activated in cancer, promoting cell growth and survival. When activated under normal physiological conditions, it responds to growth factors, such as insulin and epidermal growth factor (EGF). However, in cancer, mutations in genes such as

PIK3CA (encoding PI3K),

PTEN (a tumor suppressor that negatively regulates PI3K), or

AKT can lead to

persistent activation of the pathway, driving oncogenesis [

44,

45]. Hyperactivation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway has been implicated in various cancers, including

breast cancer, glioblastoma, and lung cancer. This leads to increased cell proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, enhanced angiogenesis, and metabolic reprogramming. Due to its critical role in cancer progression, this pathway has become a major target for cancer therapy. Drugs such as

mTOR inhibitors (e.g., rapamycin and its analogs), PI3K inhibitors, and AKT inhibitors are being developed and tested in clinical trials to block aberrant signaling and suppress tumor growth.[

46,

47] However, in cancer, signal transduction is often dysregulated due to genetic mutations, epigenetic changes, or external influences, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and metastasis.

Cancer is a complex disease influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. While rare mutations in high-penetrance genes (e.g., BRCA1/BRCA2 in breast cancer) play a role in hereditary cancers [

48]. Genome wide association studies (GWAS) focuses on identifying common genetic variants that have a small effect but collectively contribute to cancer risk in the general population. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), a landmark cancer genomics program of the National Cancer Institut4e, USA, molecularly characterized 20, 200 primary cancer and matched normal samples sampling 33 cancer types in hopes to finding the precise genetic changes that cause various types of cancer, such as breast, kidney, and liver cancer [

49]. The results showed that each cancer type had more than one hundred different mutations and those mutations were more or less random and exhibited no definite pattern. A few gens emerged as drivers of cancer, including TP53, KRAS, common in pancreatic cancer, PIC3A, common in breast cancer and BRAF, common on melanomas. However, few if any shared these known mutations across all tumors [

50]. For instance, the breast cancer is not only different from colon cancer but is different between even the two breast cancer patients.

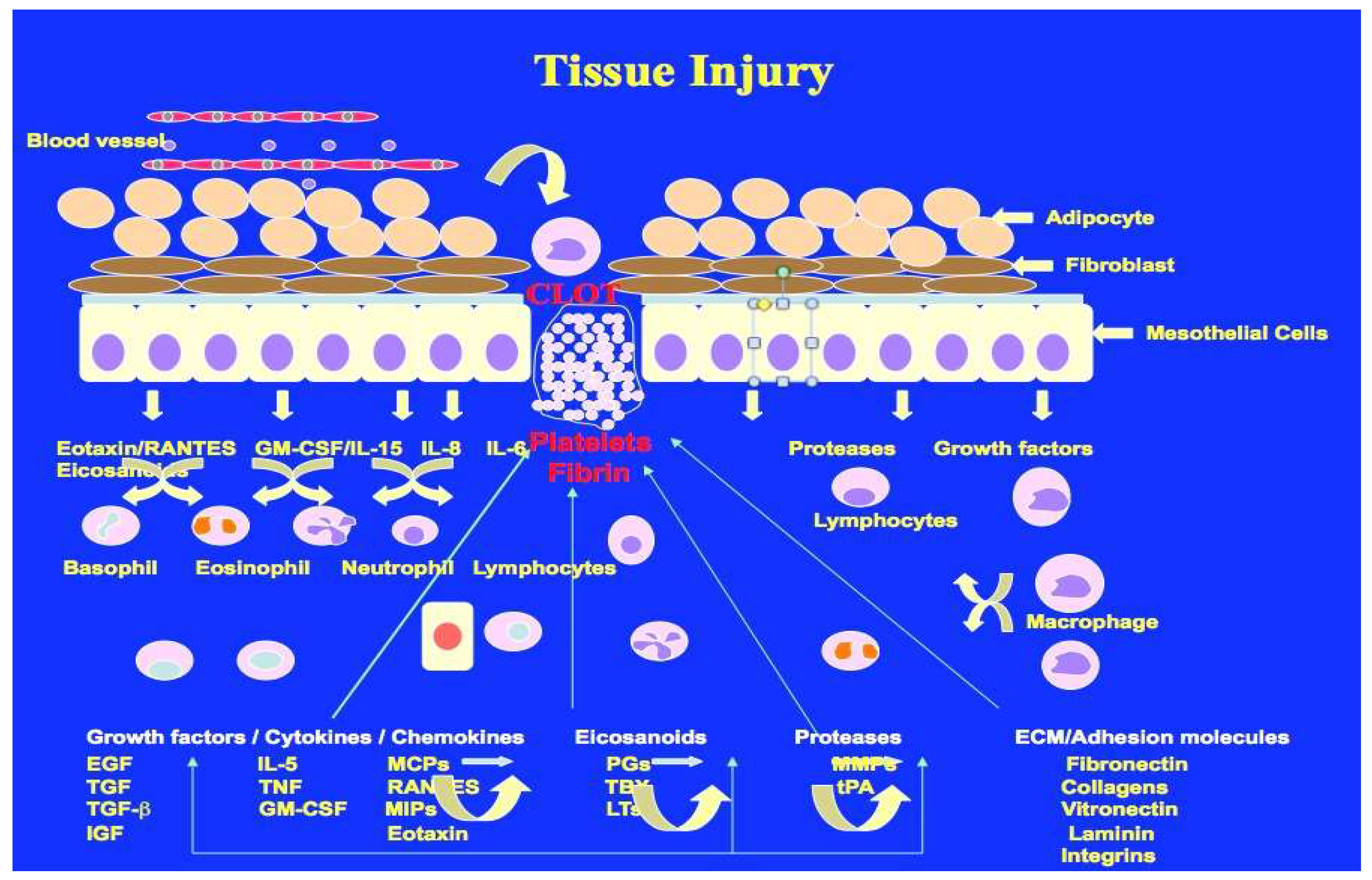

Wound healing is one of the most complex and highly dynamic process, which occurs all the time in response to any tissue injury (

Figure 1). Wound healing and cancer share some similarities in their effects on tissue, but they are fundamentally different processes. Wound healing is a natural, highly regulated process that involves the coordinated effort of various cell types to repair damaged tissues. On the other hand, cancer is an uncontrolled, aggressive growth of cells that can lead to the destruction of healthy tissues. While wound healing seeks to restore tissue integrity, cancer aims to disrupt it, making it a significant threat to overall health. It is of great interest to know how tissue repair and cancer share cellular and molecular processes that are highly regulated in wound healing but misregulated or rather dictated by cancer to meet the needs of altered metabolism. In recent years it has become clear that cancer progression and metastasis is more like a non-healing wound that is out of control. Unresolved tissue injury may initiate the process that leads to cancer [

51].

There are some emerging views that chronic or repetitive tissue injury, coupled with imperfect wound healing, can drive pathological processes instead of successful regeneration. Each cycle of wound healing involves inflammation, cell proliferation, and remodeling. However, when these processes are dysregulated—whether due to persistent stressors, accumulated DNA mutations, or epigenetic changes—tissue repair can veer toward fibrosis, chronic inflammation, or tumorigenesis [

52]. This prolonged inflammatory state is a hallmark of diseases like

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), atherosclerosis, and even cancer (e.g., colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Repeated cycles of injury and incomplete resolution lead to excessive

extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, primarily driven by

myofibroblast activation and TGF-β signaling[

53]

. Continuous cellular turnover due to damage increases the likelihood of

acquired mutations in key oncogenes (e.g.,

KRAS, TP53) or tumor suppressor genes [

54]. Chronic inflammation contributes to a

pro-tumorigenic environment, promoting

angiogenesis, immune evasion, and uncontrolled proliferation. Over time, fibrosis can impair normal tissue function, as seen in

liver cirrhosis, pulmonary fibrosis, and cardiac fibrosis. Continuous cellular turnover due to damage increases the likelihood of

acquired mutations in key oncogenes (e.g.,

KRAS, TP53) or tumor suppressor genes [

55]. Understanding the differences between these processes that lead to the initiation, progression of tumor growth and metastasis can help develop treatment strategies.

Types of Cancers

Cancer is a group of disease characterized by uncontrolled cell growth and the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. There are more than 100 types of cancers, classified based on the type of cell they originate from. In a general review like this, it is not possible to cover all types of cancer, readers are urged to refer to specific monographs related to this topic [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. Internationally accepted cancer classification developed by the Union of International Cancer Control(

UICC) and the World Health Organization (

WHO) are based on histotype, site of origin, morphology and spread of the cancer in the body [

56]. Tumors are currently diagnosed by routine histology and immunochemistry, based on their morphology and protein expression [

57]. Classification based on the gene expression signatures also have been developed with the help of artificial neural networks [

58]. Global Cancer Burden using the GLOBOCAN 2020 estimates of cancer incidence and mortality published by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Worldwide, an estimated 19.3 million new cancer cases and almost ten million cancer deaths [

59]. According to GLOBOCAN 2022, approximately 3 out of 5 people in India die following a cancer diagnosis[

60]. The incidence and prevalence of different types of cancer vary based on several factors, including geography, ethnicity, metabolic activities, and lifestyle choices [

61]. In the next few paragraphs, we describe briefly some of the common cancers.

Carcinomas originate in epithelial cells, which line the skin and internal organs. They account for about 80-90 of all cancers. Adenocarcinomas begin in mucus-producing glands (breast colon, lungs, pancreas and prostate). 1). Squamous cell carcinomas arise in the flat cells of the skin and lining of internal organs (skin, esophagus, lungs, bladder and cervix). Basal cell carcinoma is a common type of skin cancer, slow-growing and rarely spreads. Transitional cell carcinoma found in the lining of the bladder, ureters and renal pelvis. 2). Sarcomas develop in bones, muscles, fat cartilage and other connective tissues. They include; Osteosarcoma, the cancer that originates in the bones, Chondrosarcoma that arises in cartilage cells. Liposarcoma which arise in fat tissues. Leiomyosarcoma which affects smooth muscle cells and Rhabdomyosarcoma, a rare cancer of skeletal muscle tissues. 3). Leukemias; acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). 4). Lymphomas; Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), marked by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells, Non Hodgkin Lymphoma, a more common type, with various subtypes.

5) Myelomas, cancer of plasma cells, a type of white blood cell found in bone marrow, which disrupts immune function and bone health. 6). Brain and spinal cord cancers; Gliomas, which arise form glial cells, Meningiomas, which develop in the meninges (the protective layer of the brain and spinal cord), Medulloblastomas, most common in children. 7) Melanoma develops from melanocytes, the cells responsible for skin pigmentation. It is more aggressive than other skin cancers. Basal cell carcinoma, most common and slow-growing. Squamous cell carcinoma 8). Germ Cell Tumors, which arise from reproductive cells. Can occur in the testis ovary pr even outside the reproductive organs. Testicular cancer,-seminoma, and non-seminoma, Ovarian germ cell tumors are rare but aggressive. Extragonadal germ cell tumors, found in areas like chest or brain. 9) Neuroendocrine tumors which arise form neuroendocrine cells. Types of this cancer include, Carcinoid tumors often found in the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs), which affect the pancreas. 10). Rare and uncommon cancers include; Mesothelioma, a cancer that occurs in the lining of the lungs and abdomen, Thyroid cancer that affects thyroid glands, Adrenal Cancer, which develops in adrenal glands and Wilms Tumor a type of kidney cancer in children.

Discussions and Conclusion

In our introduction to this topic, we mentioned that metabolic dysfunctions lead to the development of cardiometabolic disease as well as cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. The Cleveland Clinic emphasizes that significant reductions in premature mortality due to cardiovascular disease can be achieved through lifestyle changes (Cleveland Clinic Newsroom News Update September 2021) Specifically, they highlight the importance of healthier diets, regular exercise, and avoiding smoking. The Mediterranean diet can reduce the risk of certain types of cancer. The diet, rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and olive oil, and low in processed meats, may offer protection against various cancers, including breast, prostate, colorectal, and those linked to obesity. While the evidence is strong, it is crucial to remember that most studies are observational [

120,

121]. In the case of metabolic diseases, the Framingham Heart Study played a pivotal role in identifying key risk factors—such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity—that contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease. However, a similar comprehensive framework of risk factors has not yet been fully established for the development and progression of various types of cancer [

13].

In the absence of key risk factors that promote various types of cancer, the fight against cancer has seen substantial evolution, transitioning from broadly destructive modalities such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy to more refined approaches including targeted therapies and immunotherapy. Conventional therapies, while effective to some extent, are limited by their lack of specificity and the resulting collateral damage to healthy tissues. Chemotherapy, for instance, indiscriminately attacks rapidly dividing cells, leading to severe side effects such as immunosuppression, fatigue, and organ toxicity. Radiation therapy similarly affects surrounding normal tissues, constraining the dose that can be safely delivered to tumors.

The emergence of targeted therapy marked a significant shift in the treatment paradigm. By focusing on specific molecular abnormalities unique to cancer cells—such as overexpressed receptors or mutated proteins—these therapies offer a more precise and often better-tolerated alternative. Agents like trastuzumab (Herceptin), which targets HER2 in breast cancer, and imatinib (Gleevec), which targets BCR-ABL in chronic myeloid leukemia, have dramatically improved survival and quality of life in subsets of patients. Nonetheless, challenges such as acquired resistance, limited applicability across all cancer types, and high treatment costs remain significant barriers.

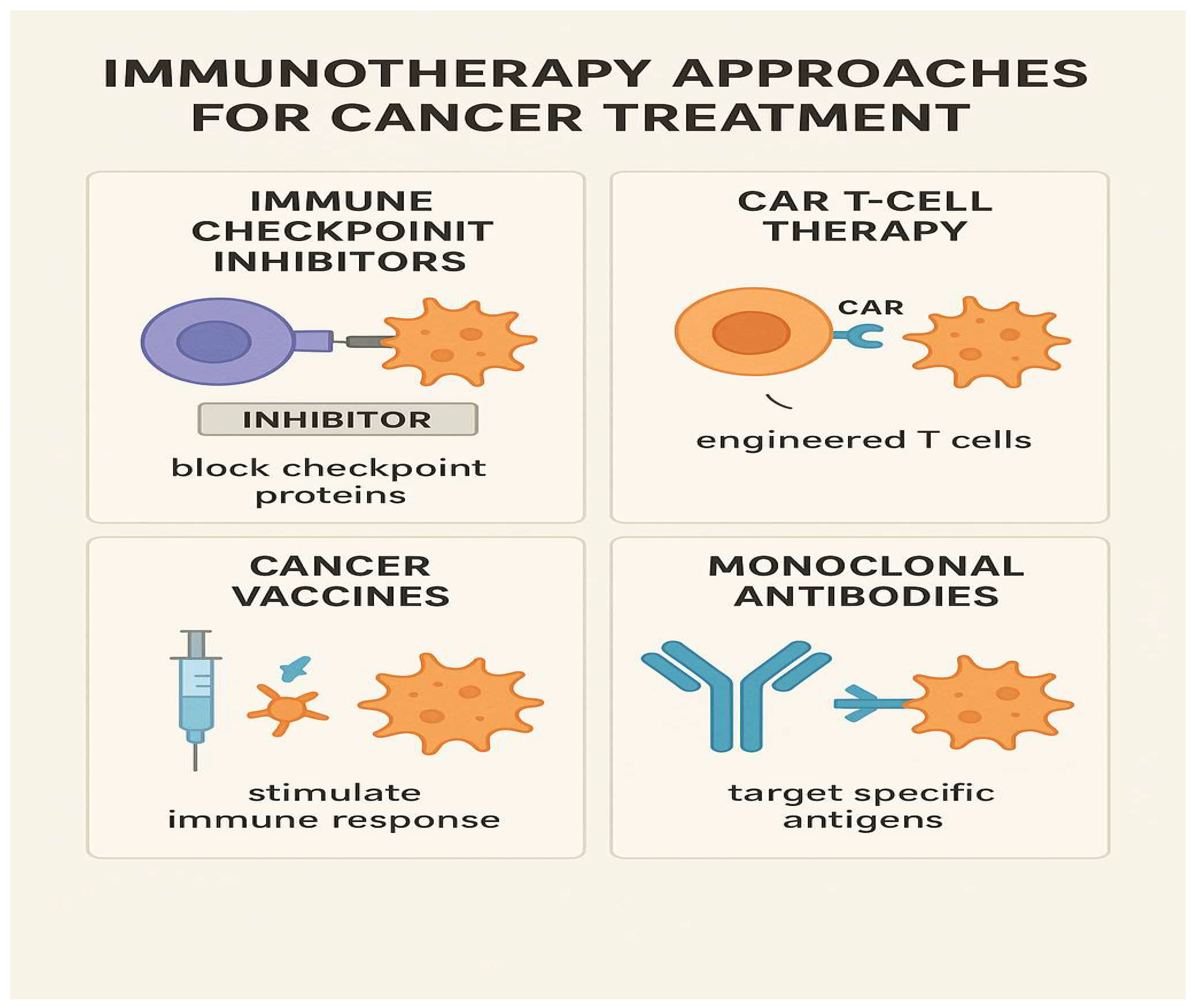

Immunotherapy represents a newer frontier, with the promise of durable responses and the potential for long-term remission, even in advanced cancers. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors, unleash the body’s own immune system against cancer cells, as illustrated in the accompanying figure (

Figure 3). This figure summarizes the mechanism by which immunotherapy reactivates T cells to recognize and destroy tumor cells that have evaded immune surveillance. Additionally, CAR-T cell therapy and cancer vaccines are broadening the scope of immune-based treatments. However, not all patients respond to immunotherapy, and immune-related adverse events—ranging from skin rashes to severe autoimmunity—pose new clinical challenges.

In conclusion, while no single therapeutic strategy is universally effective, the integration of conventional, targeted, and immune-based therapies offers a comprehensive framework to combat cancer. Personalized medicine, guided by genetic and immunologic profiling of tumors, is the way forward. Continued research into tumor biology, immune evasion mechanisms, and biomarkers of response will be essential to improve outcomes.

Author Contributions

This is an overview of metabolic risks as it refers to the initiation and progress of metabolic diseases such as hypertension, type-2 diabetes, obesity, vascular diseases, cancer and neurogenerative diseases. Drs. Y. T. Rao and G. H. R. Rao. have conceptualized and developed this essay. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Gundu H. R. Rao extends his thanks and gratitude to the National Institutes of Heart, Blood and Lung Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) USA, for their continued backing of our collaborative studies at the University of Minnesota from 1970-2000. He also extends heartfelt gratitude to the National Science Foundation (NSF), USA (1980), the United Nations Development Program (UNDP)(1990-1993), and the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis for their generous financial support.

Data Availability Statements

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgements

Professor Gundu H. R. Rao is extremely grateful to the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Lillehei Heart Institute, University of Minnesota, for their unwavering support in our research on thrombosis and hemostasis for more than four decades. He would also like to express his deep appreciation to the late Professor James G White of the University of Minnesota for his invaluable mentorship. Additionally, he extends his thanks and gratitude to the National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for their continued financial backing of our studies from 1970 to 2000. Furthermore, he expresses his sincere appreciation to the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH), USA, for their financial assistance to the South Asian Society on Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis (SASAT) from 1992 to 2000 for international educational initiatives in India. He also expresses his thanks to the National Science Foundation (NSF), USA, and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), for providing travel grants to visit India for developing bilateral research projects from 1992-2000.

References

- Koene RJ, Prizment AE , Bales A., et al.: Shared risk factors in cardiovascular disease and cancer.Circulation. 133(11): 1104-1114. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Libby P: Inflammation and cancer. Am J. Clin. Nutr. 83:456S-460S, 2006.

- Kamp DW, Shacter E, Weitzman SA: Chronic inflammation and cancer. The role of the mitochondria. Oncology 25:400-410, 2011.

- Barrera G: Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation products in cancer progression and therapy. ISRN Oncol. 201:137289, 2012.

- Thanan R, Oikawa S, Hiraku Y et al.: Oxidative stress and its significant roles in neurodegenerative diseases and cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 16:193-217, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Wolin KY, Carson K, Colditz GA: Obesity and Cancer. Oncologist 15:556-565, 2010.

- Dobbins M Decorby K Choi BC: The association between obesity and cancer risk: a meta- analysis of observational studies from 1985-2011. ISRN Prev Md. 2013:680536, 2013.

- Tsilidis KK, Kasimis JC, Lopez Ds et al.: Type 2 diabetes and cancer: umbrella review of meta-analysis of observational studies. [CrossRef]

- Tate AR. Rao GHR: Inflammation” Is it a healer, Confounder of a Promoter of Cardiometabolic Risks? Biomolecules. 14:948, 2024.

- Tate AC. Rao GHR: Cardiometabolic Diseases: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Cardiol Cardiovasc Res 3(2):1-15, 2025.

- Santiago, JA, Karthikeyan M, Lackey M et al.: Diabetes: a tipping point in neurodegenerative diseases. Trend in Mol Med 29(12):P1029-1044, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kcuik M: Alzheimer’s disuse as Type-3 diabetes: Understanding the link and implications. Int J Mol Sci. 25(22):11955.

- Mahmood SS, Levy D, Vasan RS, et al.: The Framingham Study and the Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease: A Historical Perspective. Lancet 2014 15:383 (9921): 999-1008. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al.: Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infraction in 52 countries (the INTEHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 364 (9438):937-52.

- Khera AV, Emdin CA, Drake I, et al.: Genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and coronary artery disease. N Engl. J Med 2016;375: 2349-2358.

- Di Cesare M, Bennett JE, Best N, et al.: The contributions of risk factor trends to cardiometabolic mortality in 26 industrialized countries. Int J Epidemiol. 42 (3): 838-848, 2013.

- Menash GA, Wei GS, Sorlie PD et al.: Decline in Cardiovascular Mortality: Possible Causes and Implications. Circ Res. 120(2):366-380, 2017.

- Surh YJ; The 50-year War on Cancer Revisited: Should we continued to fight the enemy within? J. Cancer Prev. 26(4):219-223, 2021.

- Rao GHR: Prevention or reversal of cardiometabolic diseases. J. Clin. Prevent Cardiol. 7 (1): 22-28, 2018.

- Clinical Handbook of Coronary Artery Disease. (Rao GHR: Editor), Jaypee Medical Publishers, New Delhi, India. 2020 ISBN# 978-93-89188-30-1.

- Cardiometabolic Diseases. Molecular Basis, Early detection of Risks and Management. ( Rao, GHR & Das UN Editors). Academic Press, Elsevier. 2024. ISBN#978-0-323-95469-3.

- Rao GHR: Integrated approach to the management of cardiometabolic diseases. Cardiol Cardiovasc Res. 2(3):37-42, 2018.

- Rao GHR: Predictive and Preventive Care: Metabolic Diseases. Clin res. Diab Endocrinol 1(1):1-9, 2018.

- Sheth M, Esfandiari L: Bioelectric dysregulation in cancer initiation promotion and progression. Front Oncol. 14:12846917, 2022. PMID: 35359398.

- Chial, H: Genetic regulation of cancer. Nature Education 1(1):67, 2008.

- Joyce C, Rayi A Kasi A: Tumor-suppressor genes. [Updated 2023]. In: Stat pearls [Internet}. Treasure Island (FL): Stat Pearls Publishing: 2025 Jan https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532243/.

- Hopkins JL, Lan Li Zou L: DNA repair defects in cancer and therapeutic opportunities. Genes Dev. 36(56);278-293, 2022.

- Lu Y, Chan Y, Tan H et al.: Epigenetic regulation in human cancer: the potential role of epi-drug in cancer therapy. Mol Cancer 19:Article number 79, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich M: DNA methylation in cancer: too much, but also too little. Oncogene 21:54005413, 2002.

- Peng Y, Croce CM: The role of microRNAs in human cancer. Signal Trans. and Targeted Ther. 1, Article number 15004, 2016.

- Carneiro BA El-Deiry WS: Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nature reviews Clin Oncol. 17:395-417, 2020.

- Elebito TC, Rotimi S, Evbuomwan IO et al.: Reassessing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in anti-cancer therapy. Cancer Treat and Res Comm. 32: 100620, 2022.

- Gilles C, Newgreen DF, Sato H et al.: Matrix metalloproteases and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: Implications for carcinomas metastasis. In: Madame Curie Bioscience Database (Internet). Austin (Tx): Landes Biosciences; 2000-2013. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6387/.

- Huang Y, Hong W, Wei: The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J. Hematol and Oncol 15, Article number 129, 2022. [CrossRef]

- He Xi, Xu C: Immune checkpoint signaling and cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 30:660-669, 2020.

- Barba I, Carillo-Bosch L, Seoane J: Targeting the Warburg effect in cancer: Where do we stand? Int J Mol Sci 25(6):3142, 2024.

- Pedersen PL; 3-Bromopyruvate (3BP) a fast acting, promising, powerful, specific, and effective “small molecule” anti-cancer agent taken from labside to bedside: Introduction to a special issue. J. of Bioenergetics and Bio membranes. 44,1-6. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Min H, Lee Ho: Molecular targeted therapy for anticancer treatment. Exp Mol Med. 54(10:1670-1694, 2022.

- Kciuk M, Yahya E, Mohamed MHI et al.: Recent advances in molecular mechanisms of cancer immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 15(10:2721, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zafar A, Khan MJ, Abu J et al.: Revolutionizing cancer care strategies: immunotherapy, gene therapy, and molecular targeted therapy. Mol Biol Reports 51:219, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fu D, Hu Z, Xu Xi et al.: Key signal transduction pathways and cross talk in cancer: Biological and therapeutic opportunities. Translational Oncol 26: 101510, 2022.

- You M, Xie Z, Zhang N et al.: Signaling pathways in cancer metabolism: Mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nature Signal Transl. and Target Ther.8. Article number 196, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Jiang W, Du Y et al.: Targeting feedback activation of signaling transduction pathways to overcome drug resistance. Drug Resistance Updates 654, 100884, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ren Xi, Long M, Li Z et al.: Oncogene PRR14 promotes breast cancer through activation of P13K signal and inhibition of CHEK2 pathway. Nature Cell Death and Diseases 11, Article number 464, 2020.

- Bittremieux M, Parys JB, Pinton P et al.: ER functions of oncogenes and tumor suppressors: Modulators of intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Biochim Biophysics Acta (BBA)-Mol Cell Res. 1863(6):1364-1378, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Glaviano A, Foo AS, Lam HY et al.: P13/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol Cancer 22, Article number 138, 2023.

- Garg P, Ramisetty S, Nair M et al.: Strategic advancements in targeting the P13k?AKT/mTOR pathway for breast cancer therapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 26:116850, 2025.

- Maner BS, Dupuis L, Solomon JA: Overview of genetic signaling pathway within cutaneous malignancies. J. Cancer Met and Treatment 6:37, 2020.

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Weinstein JN, Collison EA, Mills GB et al.: The cancer genome atlas pan0cancer analysis project. Nature Gen. 45:1113-1120, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Sinkala M: Mutational landscape of cancer-driver genes across human cancers. Sci. Reports 13:Article number 12742, 2023.

- Martin P, Pardo-Pastor C, Jenkins RG et al.: Imperfect wound healing sets the stage for chronic disease. Science 386:6726, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Xiao Xi, Yi Y et al.: Tumor initiation and early tumorigenesis: molecular mechanisms and interventional targets. Signal Trans and Target Ther. 9, Article number 149, 2024.

- Frangogiannis NG: Transforming growth factor-β in tissue fibrosis. J Exp Med. 217(3):e20190103, 2020.

- Chen Xi, Zhang T, Su W et al.: Mutant p53 in cancer: from molecular mechanism to therapeutic modulation. Nature; Cell Death and Dis. 13, Article number 974, 2022.

- Dakal TC, Dhabhai B, Pant A et al.: Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes: function and roles in cancers. Med Comm 5(6):e582, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Carbone A: Cancer classification at the crossroads. Cancers 12(4):980, 2020.

- Selves J, Long-Mira, E, Mathieu M et al.: Immunohistochemistry for diagnosis of metastatic carcinomas of unknown primary site. Cancers (Basel) 10(4):108, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Khan J, Wei JS, Ringner M et al.: Classification and diagnostic prediction of cancers using gene expression profiling and artificial neural networks. Nat Med. 7(6):673-679, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Ferkay J, Siegel RL et al.: Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin,71:209-249, 2021.

- Singh K, Grover A, Dhanasekaran L et al.: Unveiling the cancer epidemic in India; a glimpse into GLOBOCAN 2022 and past patterns. Lancet Reg Health, South East Asia 34:100546, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H et al.: Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J Clin. 74(3):229-263, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Brown JS, Amend SR, Austin RH et al.: Updating the Definition of Cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 21(11):1142-1147, 2023.

- Castaneda M, Hollander P, Kuburich NA et al.: Mechanisms of cancer metastasis. Sem in Can Biol 87:17-31, 2022.

- Tufail M, Hu J, Liong J et al.: Hallmarks of cancer resistance. iScience 27:109979, 2024. [CrossRef]

- He R, Liu Y, Fu W et al.: Mechanisms and cross-talk of regulated cell death and their epigenetic modifications in tumor progression. Mol Cancer 23, Article number 267, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kumar N, Sethi H: Telomerase and hallmarks of cancer: An intricate interplay governing cancer cell evolution. Cancer Letters 578, 216459, 2023.

- Papaneophytou C: The Warburg effect: Is it always an enemy? Front Biosci. 29(12):402, 2024.

- Liu Z, Chen H, Zheng Li-Li et al.: Angiogenic signaling pathways and anti-angiogenic therapy for cancer. Nature Signal Trans. & Targa Ther. 8 Article number 198, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH et al.: Molecular principles of metastasis: a hallmark of cancer revisited. Nature Signal Trans & Targa Ther 5, Article number 28, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Avci CB, Bagca BG, Nikanfar M, et al.: Tumor microenvironment and cancer metastasis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Front Pharmacol 15, 2024.

- Zhuang Y, Liu K, Gu Xi et al.: Hypoxia signaling in cancer: Implications for therapeutic interventions. Med COMM 23; 4(1):e203, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tufail M, Jiang C, Li N: Altered metabolism in cancer: insights into the energy pathways and therapeutic targets. Mol Cancer 23. Article number: 203, 2024.

- 73) Conroy G: Cells are swapping their mitochondria. What does this mean for our health? Nature 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mullard AL: Cancer cells “poison’ the immune system with tainted mitochondria. Nature. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Begeman A, Smolka JA, Shami A et al.: Spatial analysis of mitochondrial gene expression reveals dynamic translation hubs remodeling in stress. Sci. Adv. 11: eads6830, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Soumalainen A, Numari L: Mitochondria at the cross roads of health and disease. Cell 187:2601-2627, 2024.

- Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Sci, 124(3215):269-70, 1956.

- Wang S, Tseng L, Lee H: Role of mitochondrial alterations in human cancer progression and cancer immunity. J Biomed Sci 30, Article number: 61, 2023.

- Cal M, Matyjaszczyk I, Flilk K et al.: Mitochondrial function are disturbed in the presence of the anticancer drug, 3-Bromopyruvate. Int J. Mol Sci. 22(12):6640, 2021.

- Pederson PL: Warburg, me and Hexokinase2: Multiple discoveries of key molecular events underlying one of cancers’ most common phenotypes, the “Warburg Effect” i.e., elevated glycolysis in the presence of oxygen. J Bioenergy Biomembr 39(3): 211-22, 2007.

- David Gorski: 3-Bromopyruvate” The latest cancer cure “they” don’t want you to know about. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/3-bromopyruvate-the-latest-cancer-cure-they-dont-want-you-to-know-about/ August 15, 2016.

- Wang Yi, Lei Q: Metabolite sensing and signaling in cell metabolism. Nature Sign Trans and Targa Ther 3, Article number 30, 2018.

- You M, Xie Z, Zhang N et al.: Signaling pathways in cancer metabolism: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nature Sign Trans and Targa Ther 8, Article number 196, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lugano R, Ramachandran M, Dimberg A: Tumor angiogenesis: causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cell Mol Life Sci 77(9): 1745-1770, 2019.

- Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W et al.: Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J. Med. 350:2335-2342, 2004.

- Simth CEP, Prasad V: Targeted Cancer Therapies. Am Fam Phys 103(3):155-163, 2021.

- Shuel SL: Targeted Cancer Therapies. Can Fam Phys 68(7):515-518, 2022. PMID:35831091.

- National Cancer Institute: List of Targeted Therapy Frugs Approved for Specific Types of Cancer.

- Huang M, Shen A, Ding J et al.: Molecularly targeted cancer therapy: some lessons from the past decade. Trend in Pharmacol. Sci. 35(1):41-50,2014. [CrossRef]

- 88).Min H, Lee H: Molecular targeted therapy for anticancer treatment. Exp Mol Med. 54(10): 16701694, 2022.

-

https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/targeted-therapies/approved-drug-list.

- Esfahani K, Roudaia L, Buhlagia N et al.: A review of cancer immune therapy: from the past, to the present, to the future. Curr Oncol, 1:27(Suppl):S87-S97, 22020.

- Liu C, Yang M, Zhang D et al.: Clinical cancer immunotherapy: Current progress and prospects. Curr progress and prospects. Front Immunol 13:961805. [CrossRef]

- Emens LA, Romero PJ, Anderson AC et al.: Challenges and opportunities in cancer immunotherapy: a society for immunotherapy of cancer (SITC) strategic vision. (Position article and guidelines).J for immunotherapy. Cancer 12:e009063, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hamdan F, Cerullo: Cancer immunotherapies: A hope for the uncurable? Front Mol Med. Sec Gene and Virotherapy. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Meng L, Wu H, Ding P et al.: Mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitors: insights into the regulation of circular RNAS involved in cancer hallmarks. Cell Death & Dis. 15, Article number 3, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mitra A, Barua A, Huang L et al.: From bench to bedside”: the history and progress of CAR T Cell therapy. Front Immunol 14, 2023.

- Fan T, Zhang M, Yang J et al.: Therapeutic cancer vaccines: advances, challenges and prospects. Sign Trans and Targa Ther 8, Article number 450, 2023.

- Pento JT: Monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of cancer. Anticancer Res. 37:5935-5939, 2017.

- Ruff S, Pawlik TN: A review of translational research for targeted therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancers ( Basel). 15(5): 1395, 2023.

- Kiran NS, Yashaswini C, Maheshwari R et al.: Advances in Precision Medicine approaches for colorectal cancer: Molecular profiling to targeted therapies. ACS Pharmacol Trans Sci. 7(4):967-990, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gullapalli RR, Desai KV, Santana-Santos L et al.: Next generation sequencing in clinical medicine: Challenges and lessons for pathology and biomedical informatics. (“Emulsion PCR: Techniques and Applications - Springer Nature”) J Patho. inform 3(1):40, 2012. PMID: 23248761. [CrossRef]

- Tolkach Y, Wolgast LM, Damanakis A et al.: Artificial intelligence for tumor tissue detection and histological grading in esophageal adenocarcinomas: a retrospective algorithm development and validation study. The Lancet Digital Health 5(5): E265-E275, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xu T, Ngan DK, Zheng W et al.: Systematic identification of cancer pathways and potential drugs for intervention through multi-omics analysis Pharmacogenomics J 25(1):2, 2025.

- Hegde PS, Chen DS: Top 10 challenges in cancer immunotherapy. Immunity 52 (1):17-35, 2020.

- Cercek A, Foote MB, Rousseau B et al.: Non-operative management of Mismatch Repair-Deficient Tumors. N. Engl J. Med. April 27, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Youssef E, Fletcher B, Palmer D: Enhancing precision in cancer treatment: the role of gene therapy and immune modulation in oncology. Front Med. Sec. Gen and Cell Ther. 11, 1527600. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Daley J: Four success stories in gene therapy. Nature innovations In. Published online 2021. [CrossRef]

- He, S: The first human trial of CRISPR-based cell therapy clears safety concerns as new treatment for late-stage lung cancer. Sign Tran Targa Ther 5:168, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman JE, Davis ME: Clinical experiences with systematically administered siRNA-based therapeutics in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Disco. 14:843-56, 2015.

- Liu E, Marin D, Macapinlac HA et al.: Use of Car-transduced killer cells in CD19-positive lymphoid tumors. N Engl J. Med. 382:545-53, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cesur-Ergun B, Demir-Dora D: Gene therapy in cancer. J Gene Med 25:e3550, 2023.

- Jin H, Wang L, Bernards R: Rational combinations of targeted cancer therapies: background, advances and challenges. Nature Rev Drug Disc. 22:213-234, 2023.

- Ayoub NM: Editorial: Novel combination therapies for the treatment of solid cancers. Front Oncol. 11: 2021.

- El Sayed KA, Ayoub NM(Editors): Novel combination therapies for the treatment of solid tumors. Front Res Topics. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Rao VP, Gupta S, Natarajan A et al.: Cloud-based biological domain knowledge derived gene expression classifier to predict the cancer clinical outcome [abstract]. In: Proceedings of the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021; 2021 Apr 10-15 and May 17-21. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; Cancer Res 2021;81(13_Suppl):Abstract nr LB018.</p.

- Verma G, Rebholz-Schuhmann D, Madden MG: Enabling personalized disease diagnosis by combining a patient’s time-specific gene expression profile with a biomedical knowledge base. BMC Bioinformatics 25, 62, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Barot S, Patel H, Yadav A et al.: Recent advancement in targeted therapy and role of emerging technologies to treat cancer. Med Oncol. 40:324, 2023. PMID: 37805624. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez CR: Four new technologies that will change cancer treatment. https://www.labiotech.eu/in-depth/cancer-treatments-immuno-oncology/.

- Budnik B, Amirkhani H, Forouzanfar M et al.: Novel proteomics-based plasma test for early detection of multiple cancers in the general population. BMJ Oncol 3(1):e000073, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ma L, Guo H, Zhao Y et al.: Liquid biopsy in cancer: current status, challenges and future prospects. Nature, Sign Tran Targa Ther. 9 Article number 336, 2024.

- Monllor-Tormos A, Garcia-Vigara A, Morgan O et al.: Mediterranean diet for cancer prevention and survivorship. Maturitas 178:107841, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mentella MC, Scaldaferri F, Ricci C, et al.: Cancer and Mediterranean diet: A Review. Nutrients 11(9):2059, 2019. PMID: 31480794. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).