1. Introduction

The Human Genome Project (HGP) and ENCODE revealed ~80% of the genome is transcriptionally active, yet only 2% encodes proteins, with the majority comprising non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) [

1,

2,

3]. lncRNAs, once deemed " junk RNA," are now recognized as multifunctional regulators of cellular differentiation, development, and stress responses[

2,

4]. They modulate three-dimensional chromatin architecture[

5] stabilize telomeres[

6,

7], remodel chromatin via histone modifications[

8], regulate imprinting genes[

9], and control transcription through promoter-associated (paRNAs) [

10] or enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) [

11]. Despite this progress, >70% of lncRNAs lack functional annotation, with many uncharacterized due to tissue-specific expression. Critical gaps persist in defining their structural motifs, dynamic interactions, and physiological roles beyond model systems. Their functional redundancy, context-dependent activity, and spatiotemporal regulatory hierarchies remain poorly resolved. Deciphering lncRNA biology requires integrating advanced tools to map their mechanistic diversity and organismal impact.

Ionizing radiation exerts its genotoxic effects via two primary mechanisms: direct ionization of cellular constituents and indirect oxidative stress mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS). These synergistic pathways collectively induce critical biomolecular lesions, including DNA strand breakage, structural and functional protein alterations, and peroxidative degradation of lipid membranes [

12,

13,

14]. Emerging evidence elucidates an expanded regulatory architecture of ionizing radiation responses, wherein lncRNAs serve as bifunctional mediators: concurrently operating as molecular rheostats modulating radiosensitivity through epigenetic coordination of DNA repair machinery, while exhibiting biomarker potential via radiation dose-responsive transcriptional dynamics[

15,

16,

17,

18]. Mechanistic investigations in oncological contexts reveal lncRNAs orchestrate cellular radiation responses through metabolic network crosstalk, with urothelial cancer associated 1 (UCA1) constituting a prototypical regulator that augments radiosensitivity in cervical carcinoma models through targeted suppression of hexokinase 2 (HK2), the pivotal glycolytic gatekeeper enzyme[

19]. The growth arrest-specific 5 (GAS5) lncRNA augments radiation responsiveness through inhibition of miR-21 and activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling cascade[

20]. Conversely, LINC01134 establishes radiation defense systems in hepatocellular carcinoma via kinase rewiring of MAPK-mediated DNA damage checkpoints, clinically correlating with acquired radioresistance phenotypes [

21]. This regulatory cartography establishes lncRNAs as nodal regulators operating across the radiation biology continuum, from real-time dosimetric biomarkers to druggable targets within therapeutic resistance networks.

CRISPR-based genome engineering has emerged as a cornerstone technology in functional genomics research due to its high-precision genome editing capabilities, enabling large-scale functional screens through molecular engineering innovations. The catalytically deactivated dCas9 variant has evolved into modular platforms for locus-specific epigenetic reprogramming, retaining sequence-specific DNA anchoring while acquiring transcriptional control through effector domain fusions (e.g., VP64 transactivation complexes) or chromatin remodeling capacity via enzymatic payload conjugation (e.g., p300 acetyltransferase) [

22]. Parallel advancements in CRISPR screening methodologies employ multiplexed sgRNA libraries for systematic interrogation of gene regulatory networks, where genome-scale or pathway-focused guide RNA collections enable combinatorial genome perturbations coupled with deep phenotyping and next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based deconvolution to resolve genotype-phenotype correlations. CRISPRa systems epitomize this technological evolution, deploying dCas9-transactivator chimeras guided by sgRNA constellations to achieve transcriptional amplification at promoter-proximal genomic coordinates[

23,

24]. Continuous methodological refinements have spawned applications ranging from genome-wide transcriptional activation mapping - revealing histone acetyltransferase (HAT) inhibitor complexes as HIV-1 proviral integration modulators[

25] - to precision oncology investigations where CRISPRa screens delineated metabolic adaptation networks underlying metformin resistance in prostate cancer[

26]. This proven capacity for functional lncRNA annotation establishes CRISPRa as a transformative framework for decrypting radiation-inducible non-coding RNA circuits, particularly in mapping therapeutically actionable lncRNA nodes within ionizing radiation response cascades.

Despite growing recognition of non-coding RNAs as master regulators of radiation response pathways, the systematic identification and mechanistic characterization of functionally significant lncRNAs in radiation biology remains an unresolved challenge. In this study, we explored CRISPRa library-based high-throughput screening and identified LOC401312 as a central regulator of radiosensitivity in NSCLC. Mechanistically, we demonstrate that LOC401312 functions as a transcriptional enhancer of CPS1, thereby revealing an unexpected connection between urea cycle metabolism and radiation response in NSCLC pathogenesis.

2. Results

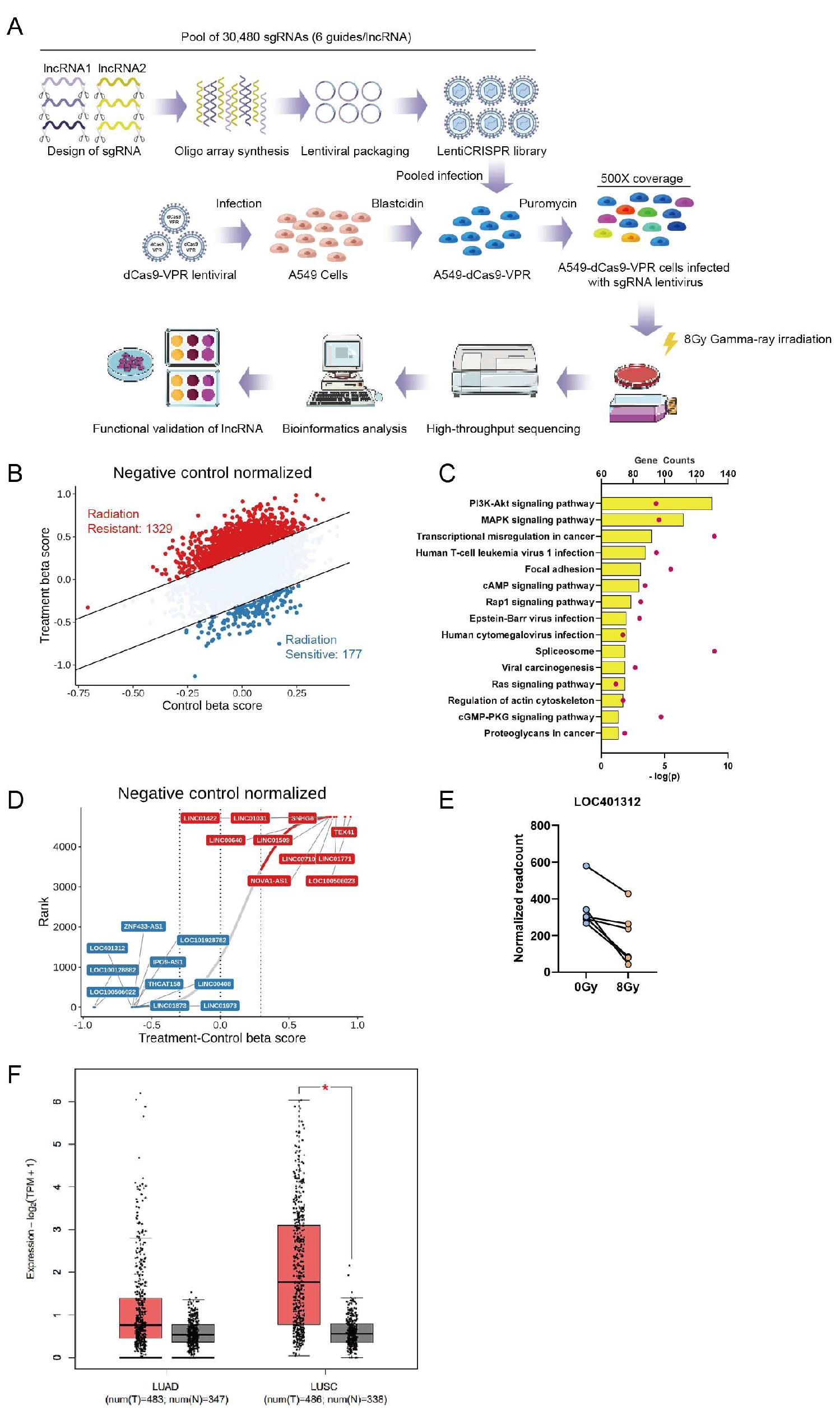

2.1. Systematic Identification of Radiation-Responsive lncRNAs via CRISPRa Screening in NSCLC

To investigate lncRNAs critical in ionizing radiation response, we performed functional screening of 4,766 lncRNAs expressed in non-small cell lung cancer using a CRISPRa non-coding library containing six sgRNAs per lncRNA and 1,884 control sgRNAs packaged into puromycin-resistant lentiviral vectors. Following lentiviral transduction of A549-dCas9-VPR cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1, we performed 4-day puromycin selection to establish polyclonal populations with single sgRNA integrations. Cells were then subjected to γ-irradiation (8Gy, ⁶⁰Co source), with genomic DNA extracted from irradiated and non-irradiated control cells at day 14 post-treatment for sgRNA abundance quantification through next-generation sequencing (

Figure 1A). Bioinformatic interrogation of sgRNA distribution patterns revealed distinct radiation-responsive candidates: enriched sgRNAs corresponded to radioresistance-associated lncRNAs, while depleted sgRNAs indicated radiosensitizing targets, collectively identifying 1,329 radioresistant and 177 radiosensitive lncRNAs (

Figure 1B). Protein interaction networks of these lncRNAs analyzed via LncSEA (

http://bio.liclab.net/LncSEA) demonstrated significant enrichment in PI3K-Akt and MAPK signaling pathways (

Figure 1C), consistent with established lncRNA-mediated radiation response mechanisms. The beta score ranking and differential gene visualization revealed radiation-associated lncRNAs identified through our screening, with LOC401312 emerging as a prioritized candidate (

Figure 1D). Multi-replicate sgRNA correlation analysis revealed LOC401312 as a significantly enriched radiosensitizing lncRNA (

Figure 1E), establishing it as a prime candidate for mechanistic interrogation. Clinical relevance analysis using GEPIA2 (

http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn) revealed significant downregulation of LOC401312 expression in both lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues (

Figure 1F), suggesting potential tumor-suppressive roles associated with its radiation response modulation.

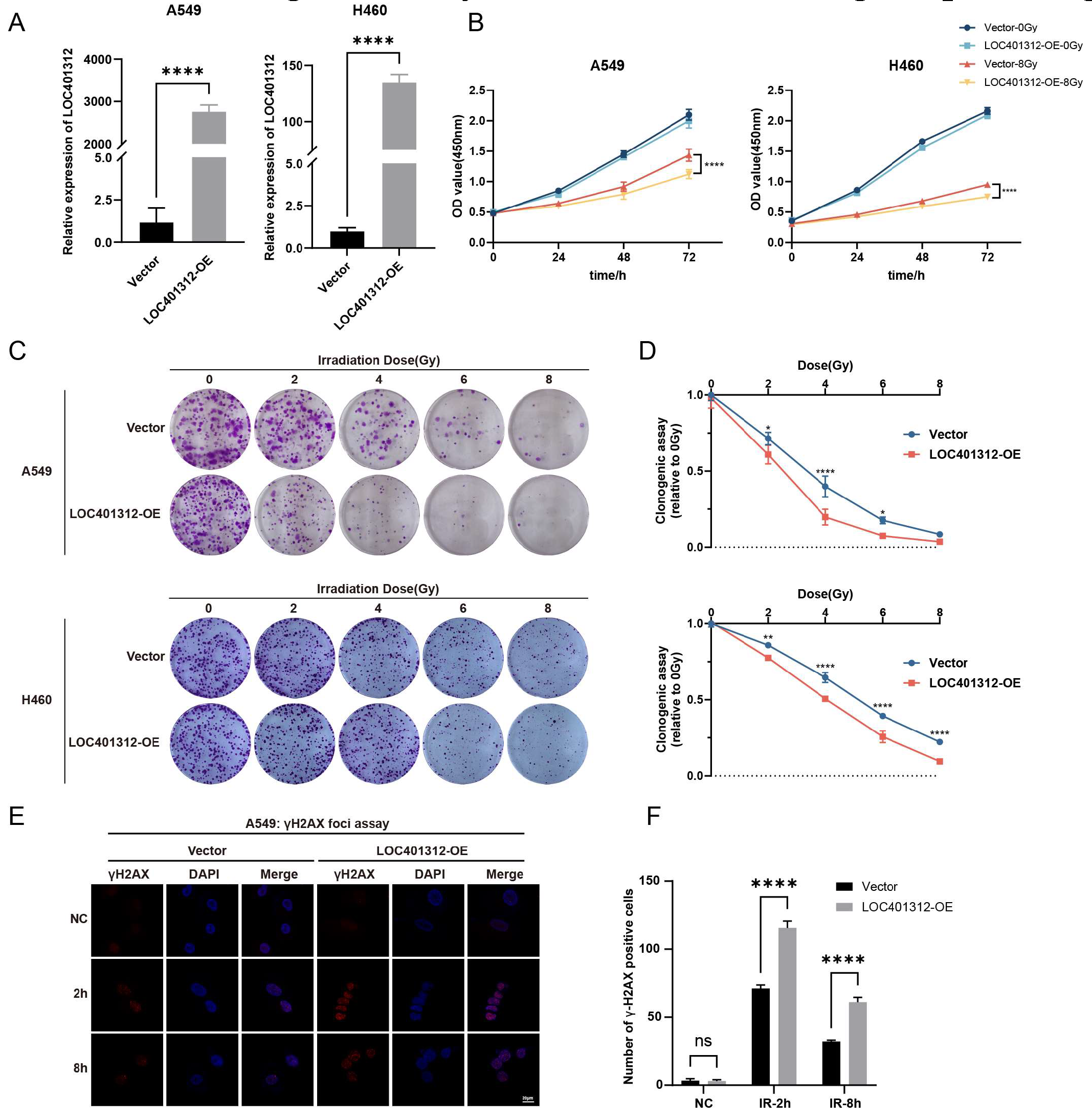

2.2. LOC401312 Validated as a Radiosensitizing lncRNA in Lung Cancer Cells

LOC401312, a five-exon lncRNA transcribed from the STEAP1B locus on chromosome 7, was functionally characterized through overexpression in A549 and H460 lung cancer cells, with qRT-PCR validation confirming robust transcriptional activation efficiency (

Figure 2A). Radiation sensitivity analyses of cells were perforemd via CCK-8 proliferation assay and clonogenic survival test following 8 Gy irradiation. Overexpression of LOC401312 in A549 cells significantly reduced cellular proliferation by 21.7% (

p < 0.0001) at 72 hours post 8 Gy ionizing radiation compared to controls (

Figure 2B), while colony formation assays demonstrated a marked decline in colony-forming capacity of LOC401312-overexpressing cells (

Figure 2C). At 8 Gy irradiation, which exceeds the threshold of cellular repair mechanisms, no significant difference was observed between LOC401312-overexpressing and control groups (

Figure 2D). Cross-validation in the H460 lung cancer cell line confirmed that LOC401312 overexpression similarly enhanced cellular sensitivity to ionizing radiation. To evaluate DNA damage repair modulation, phosphorylation of histone H2AX at serine 139 (γH2AX), a established molecular marker for double-strand break (DSB) formation and repair progression, was analyzed at 2- and 8-hour post-2 Gy γ-irradiation. Cells were fixed, stained with γH2AX-specific antibodies, counterstained with DAPI, and subjected to foci quantification (>20 foci/nucleus defined as positive) (

Figure 2E). In the control cells, γH2AX is significantly induced at 2 hours after exposure and decreases at 8 hours, suggesting rapid DNA damage repair in the cells. In LOC401312-overexpressing cells, the number of γH2AX foci is significantly higher than that in the control group, and even at 8 hours, a higher level of γH2AX can still be detected, indicating that overexpression of LOC401312 can significantly inhibit DNA damage repair (

Figure 2F).

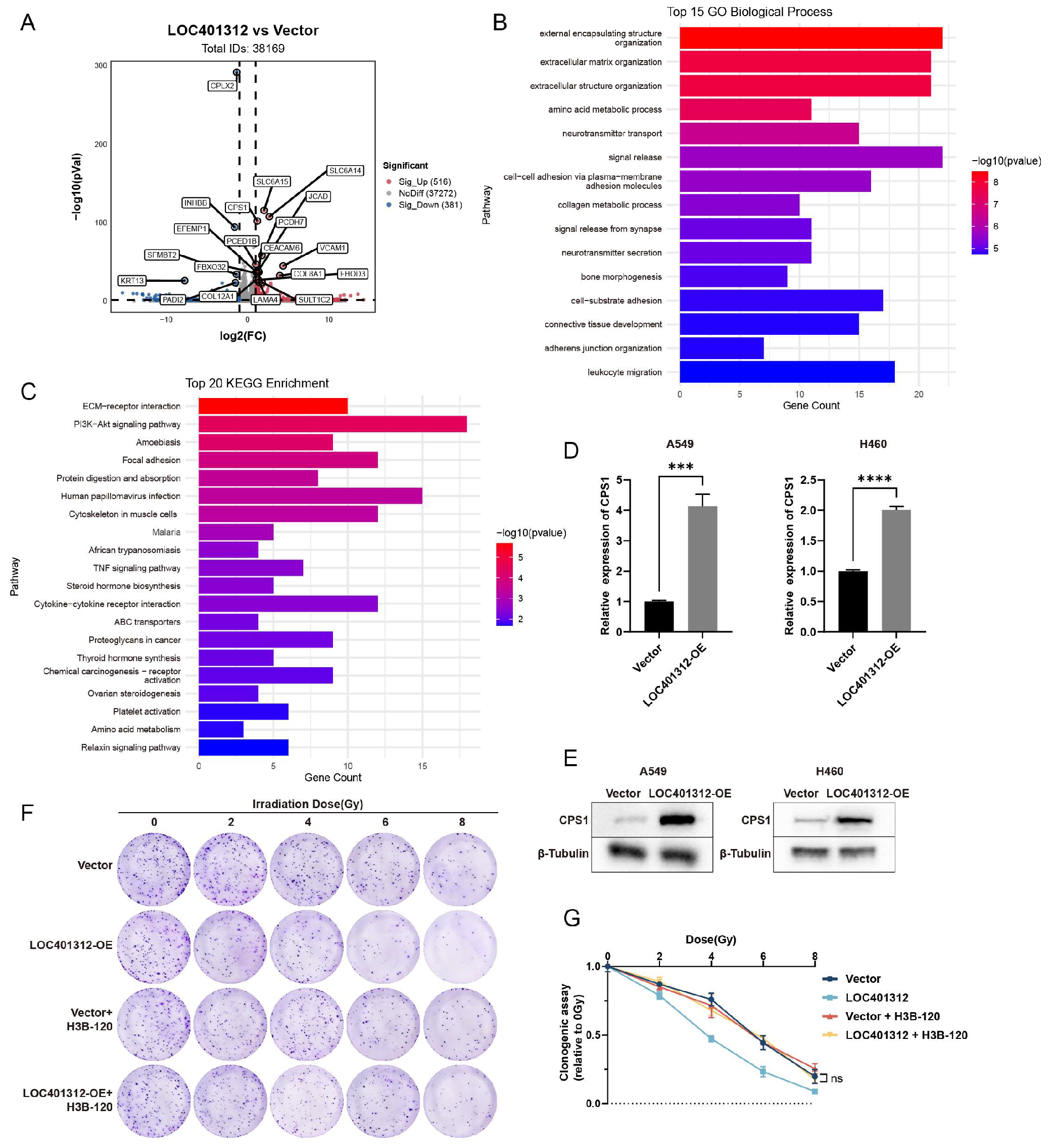

2.3. Transcriptomic Profiling of LOC401312-Overexpressing A549 Cells Identifies CPS1 as a Functional Mediator of Radiation Sensitivity

Transcriptomic sequencing of LOC401312-overexpressing versus control cells identified 205 upregulated and 110 downregulated genes (|log2(fold change)| >1, adjusted p-value <0.05) (

Figure 3A). GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of significantly differentially expressed genes from transcriptomic sequencing revealed a predominant enrichment in amino acid metabolism pathways, providing critical clues for subsequent investigations. Convergent evidence from these analyses, combined with volcano plot characterization, collectively implicated CPS1 as a prioritized candidate (

Figure 3B-C). Cross-validation in multiple lung carcinoma cell lines confirmed CPS1 as the most robustly induced target, where LOC401312 overexpression in A549 cells elevated CPS1 mRNA levels by 4.1-fold compared to empty vector controls (

Figure 3D), with Western blot analysis further demonstrating concomitant upregulation of CPS1 protein expression (

Figure 3E), and parallel results observed in the H460 lung cancer cell line, collectively highlighting consistent transcriptional activation and protein-level induction across models. Pharmacological inhibition of CPS1 enzymatic activity using the specific small-molecule inhibitor H3B-120 in LOC401312-overexpressing A549 cells significantly reversed the radiation sensitization phenotype (

Figure 3F-G), demonstrating the functional dependency of LOC401312-mediated radiosensitization on CPS1 catalysis. These findings indicate that the radiation-sensitizing effects triggered by LOC401312 overexpression are mediated via CPS1 enzymatic activity.

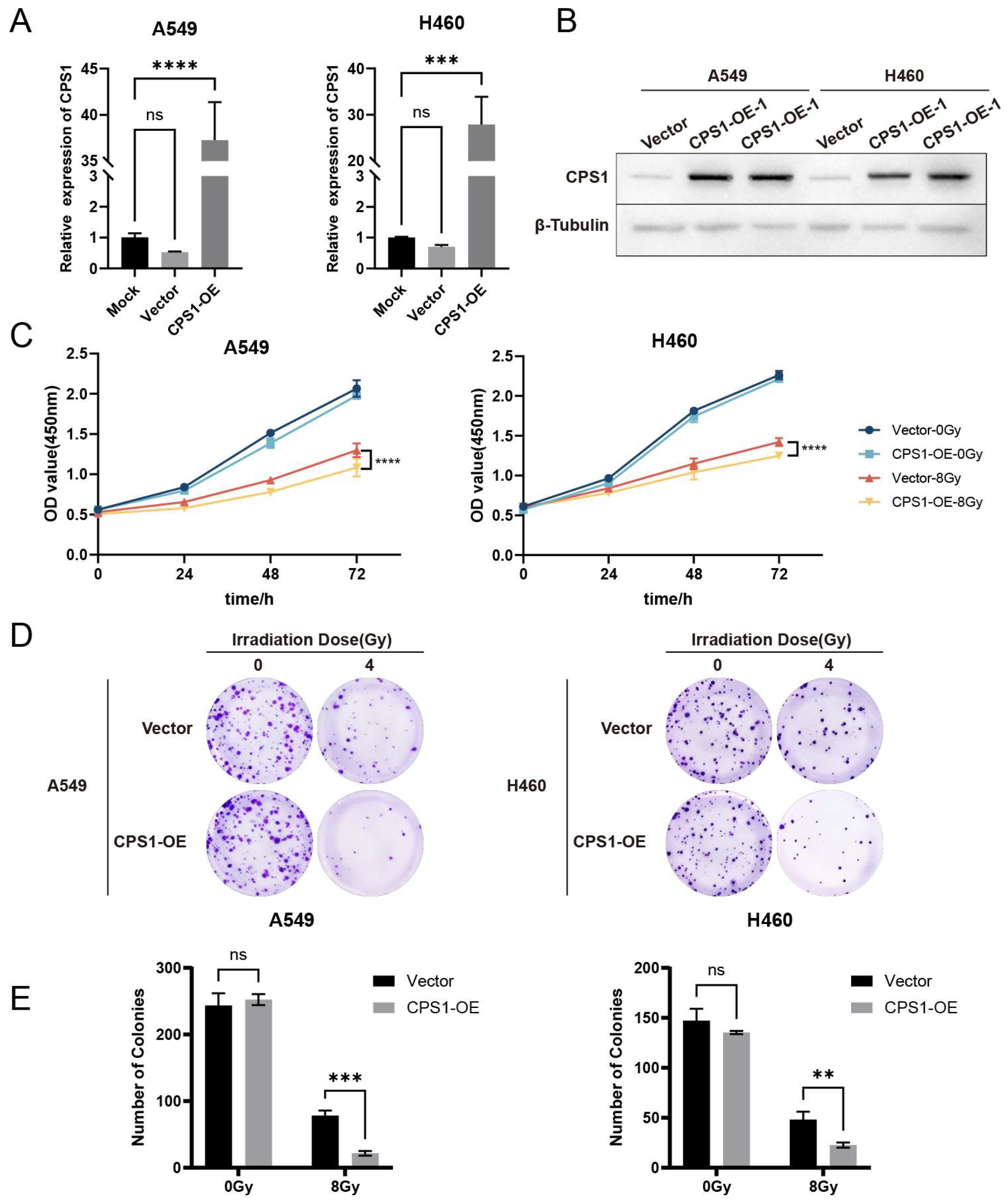

2.4. CPS1 Overexpression Enhances Radiosensitivity in Lung Carcinoma Cells

To evaluate the role of CPS1 in LOC401312-induced radiation sensitization, stable CPS1-overexpressing cell lines were generated in A549 and H460 models via jetPRIME-mediated transfection with human CPS1 cDNA-containing plasmids. RT-qPCR analysis revealed that overexpression of CPS1 in A549 cells elevated its mRNA levels by 37.25-fold compared to mock controls (

Figure 4A), with Western blot analysis confirming a marked increase in CPS1 protein expression (

Figure 4B), while parallel experiments in H460 cells demonstrated a 27.88-fold upregulation of CPS1 mRNA and a corresponding significant protein-level induction. The proliferation assay demonstrated that significantly impaired cellular proliferation in CPS1-overexpressing lung cancer cells compared to vector controls following 8 Gy ionizing radiation (

Figure 4C). Clonogenic survival tests revealed markedly enhanced radiosensitivity in CPS1-overexpressing lines post-8 Gy irradiation, exhibiting 72.2% (

p=0.0002) and 52.7% (

p=0.0029) reductions in colony formation capacity for A549 and H460 respectively compared to controls (

Figure 4D-E). These findings indicate that CPS1 overexpression significantly enhances ionizing radiation sensitivity in both A549 and H460 cell lines.

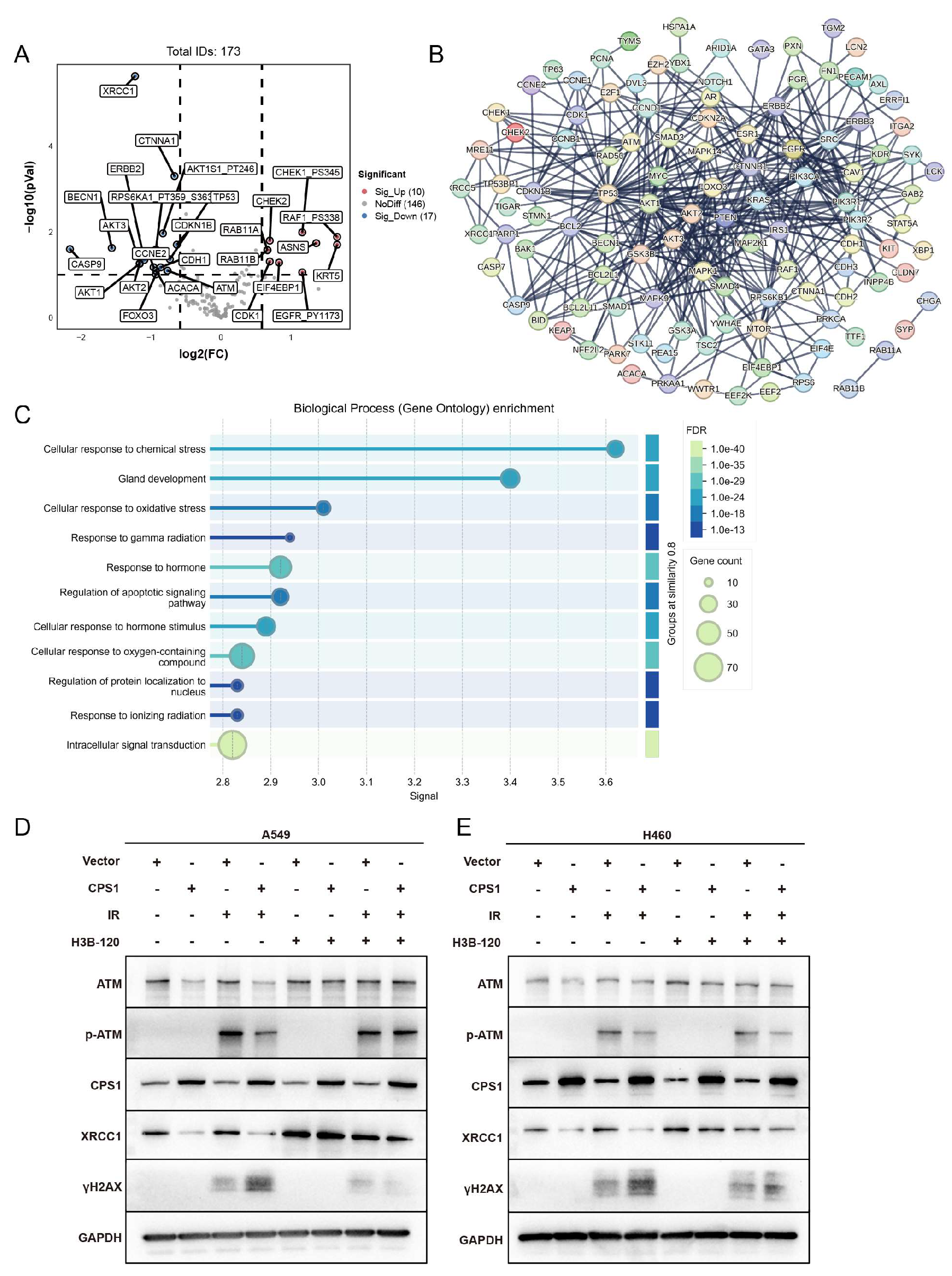

2.5. Co-expression Network Analysis of CPS1 in Lung Cancer Identifies DNA Damage Repair Modulation as a Mechanism Governing Ionizing Radiation Sensitivity

Integrated analysis of CPS1 co-expression networks in TCGA lung cancer cohorts via cBioPortal identified 174 significantly correlated genes (

Table S2). Volcano plot analysis of co-expression profiles showed marked downregulation of radiation-associated genes ATM and XRCC1 (

Figure 5A). Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network mapping reveals core hub genes enriched in DNA damage response (DDR) regulators including AKT1, ATM, and RAD50 (

Figure 5B). GO analysis demonstrated significant enrichment in oxidative stress response, gamma radiation response, and ionizing radiation response pathways (

Figure 5C). Western blot analysis revealed marked downregulation of ATM and XRCC1 protein levels in CPS1-overexpressing A549 cells compared to vector controls following 8 Gy IR, accompanied by decreased ATM phosphorylation (p-ATM) and elevated γH2AX accumulation post-irradiation (

Figure 5D). H460 cells exhibited significant XRCC1 suppression and γH2AX elevation with minimal ATM protein reduction, though p-ATM attenuation was consistently observed post-IR (

Figure 5E). Remarkably, inhibition of CPS1 enzymatic activity via H3B-120 pre-irradiation treatment restored ATM and XRCC1 protein expression to baseline levels, confirming the functional dependency of this regulatory axis on CPS1 catalysis. This work collectively suggests that the regulatory potency of CPS1 on DNA damage repair key factors such as ATM may vary across different lung cancer cell lines, and its modulation of cellular ionizing radiation sensitivity could involve distinct biological pathways. These findings delineate a novel urea cycle-dependent mechanism through which CPS1 metabolically regulates ATM kinase activity to influence DNA repair fidelity and radiation sensitivity in lung carcinoma cells.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3. Discussion

This study demonstrates that LOC401312, a radiosensitizing lncRNA identified through CRISPRa screening, enhances ionizing radiation sensitivity in lung cancer cells via the LOC401312-CPS1 transcriptional regulatory axis. Mechanistic investigations further reveal that CPS1 may function as a central regulatory hub within the DDR pathway in lung carcinoma, orchestrating radiation-induced genomic instability through metabolic-epigenetic crosstalk.

lncRNAs, representing the largest class of non-coding RNAs with over 90,000 annotated genes[

27], play pivotal roles in transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation through interactions with DNA, RNA, or proteins[

28]. Emerging evidence implicates specific lncRNAs as promising radiation response modulators and biomarkers[

29]. The radiosensitizing lncRNA LOC401312 identified in this study represents an uncharacterized lncRNA, with no prior reports linking it to ionizing radiation sensitivity regulation. Overexpression of LOC401312 enhanced radiation sensitivity in A549 and H460 cells, exacerbating DNA damage severity, while the CPS1-specific inhibitor H3B-120 reversed this radiosensitizing effect. Preliminary mechanistic exploration revealed partial overlap between microRNAs targeting CPS1 and those computationally predicted to interact with LOC401312, suggesting potential regulatory cross-talk that may guide future investigations into the LOC401312-CPS1 axis.

CPS1, the rate-limiting enzyme of the urea cycle, catalyzes the ATP-dependent condensation of bicarbonate, ammonia, and ATP into carbamoyl phosphate within hepatic mitochondrial matrices under physiological conditions[

30]. As a central regulator of hepatic metabolic homeostasis, CPS1 not only mediates ammonia detoxification but also exhibits aberrant expression patterns correlating with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) progression and liver fibrosis staging[

31]. Intriguingly, CPS1 displays tissue-specific oncogenicity: its overexpression in colorectal cancer patients with poor neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy response associates with reduced pathological complete remission rates and shortened progression-free survival[

32], while hepatocellular carcinoma studies demonstrate that CPS1 deficiency enhances radiation sensitivity through c-Myc regulation[

33]. Notably, our findings align with CPS1's radiation-sensitizing role in lung cancer, where co-expression network analysis and post-irradiation Western blot assays revealed enzyme activity-dependent modulation of DNA damage repair and oxidative stress pathways. In our models, CPS1 overexpression induced significant downregulation of DNA damage response mediators ATM and XRCC1, impairing radiation-induced ATM phosphorylation at Ser1981 as demonstrated by Western blot analyses. ATM, a master regulator of DNA double-strand break repair, orchestrates activation of cell cycle checkpoints, DNA repair cascades, and apoptotic pathways through phosphorylation of downstream targets including Chk2 and p53[

34,

35,

36], while XRCC1 functions as an essential scaffolding protein coordinating base excision repair and single-strand break repair complex assembly through its BRCT domain-mediated protein interactions[

37,

38,

39]. The observed dual suppression of ATM and XRCC1 expression in CPS1-overexpressing lung carcinoma cells creates a compounded DNA repair deficiency phenotype, mechanistically explaining enhanced radiation sensitivity. This study provides the first demonstration of urea cycle enzyme CPS1 functioning as a metabolic-epigenetic regulator of DNA damage response fidelity in lung cancer radiobiology, with its novel mechanism of radiation sensitization through ATM/XRCC1 pathway modulation remaining previously uncharacterized in the literature. Critically, clinical cohort analyses reveal CPS1 overexpression in specific lung cancer subtypes, with emerging evidence positioning it as a diagnostic biomarker candidate[

40,

41], thereby establishing CPS1 as a novel metabolically driven therapeutic target for optimizing radiotherapy efficacy through metabolic-epigenetic crosstalk.

This study provides the first evidence of urea cycle enzyme CPS1 functioning as a DDR pathway modulator in lung cancer radiobiology. The identified LOC401312-CPS1 axis offers dual therapeutic strategies: enhancing radiosensitivity through targeted axis activation or improving radiotherapy efficacy via small-molecule inhibition of CPS1-mediated DNA repair compensation. CPS1 emerges as a dual-functional candidate in lung cancer patients, serving both as a potential diagnostic biomarker and a radiosensitizing therapeutic target to optimize radiotherapy efficacy through its novel role in metabolic regulation of DNA damage response pathways. Further investigations should delineate the molecular mechanisms underlying LOC401312-mediated CPS1 transcriptional regulation and explore urea cycle metabolites in radiation response.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Transfection

The A549 and H460 cell lines, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), were cultured in their respective growth media: A549 cells in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Pleasanton, CA, USA) and H460 cells in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (RPMI-1640; Gibco, Pleasanton, CA, USA), both supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Pan-Biotech, Adenbach, Germany) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cell transfections were performed using the jetPRIME transfection reagent (Polyplus, Illkirch, France) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

4.2. Infection of lncRNA Activation Libraries and Screening

Lentiviral CRISPR library transduction commenced at 80% confluence following ice-thawed viral preparation, with infection cocktails containing 1 ml culture medium, 3 μl Polybrene, and 0.9 μl lentiviral particles. Fifty percent medium replacement preceded addition of the infection mixtur. A549-dCas9-VPR cells were seeded into T75 flasks and then infected with the library lentiviruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1. Complete medium exchange occurred at 12 h post-transduction, succeeded by puromycin selection medium (2 μg/ml) application at 48 h for 4-day antibiotic resistance selection. Two distinct screening strategies were implemented: high-density cell culture to simulate conventional proliferative conditions and low-density culture to assess single-cell survival capacity. For the high-density model, cells were exposed to fractionated ⁶⁰Co γ-ray irradiation (2 Gy/day for 4 consecutive days) in treatment groups versus non-irradiated controls, with both cohorts subcultured on days 2, 6, and 10 post-completion of irradiation (designated as day 0), followed by cell collection and cryopreservation at -80°C on day 14 for subsequent genomic DNA extraction. The low-density protocol utilized an acute 8 Gy ⁶⁰Co γ-ray irradiation single dose in treatment groups, after which control cells underwent subculturing on days 5 and 10 while irradiated cells were maintained without passaging through biweekly medium replacement for 14 days, culminating in day 14 cell harvest and cryopreservation at -80°C prior to downstream genomic analyses.

4.3. Illumina Sequencing of sgRNAs

Genomic DNA samples from day 0 background control cells and day 14 experimental cells were submitted to Genewiz (Suzhou, China) for nucleic acid quality control. Qualified samples (2–3 μl genomic DNA) underwent sgRNA sequence amplification and subsequent library preparation, followed by high-throughput sequencing on the Illumina platform to generate raw sequencing data (FASTQ-formatted files containing gRNA core sequences). Sequencing outputs were subjected to data quantification and quality assessment prior to bioinformatic analysis, with sgRNA enrichment/depletion profiling performed to identify radiation-responsive genetic elements based on differential read abundance.

4.4. Construction of Overexpression Cell Lines

Stable overexpression cell lines for LOC401312 and CPS1 were generated using the PiggyBac transposon system through co-transfection of PiggyBac transposase plasmid PB210PA-1 and PiggyBac Dual Promoter plasmid PB514B-2(System Biosciences, CA, USA) into A549 and H460 cell lines according to manufacturer-recommended ratios. Following transfection, puromycin selection was implemented to establish genomically integrated cell populations, with transposase-mediated integration efficiency validated through antibiotic resistance profiling and subsequent target gene expression verification.

4.5. Colony Formation Assay

Overexpression and control cells were plated at varying densities in 6-well plates and subjected to ionizing radiation (IR) treatment at 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy doses 18 h post-seeding, followed by 10-14 days of culture with medium replacement every 48 hours until macroscopic colony formation. Fixed cells were processed through sequential PBS washes, methanol fixation (20 min), and 0.2% crystal violet staining (5 min) prior to destaining and imaging. Colony quantification was performed using standardized counting criteria, with only colonies containing ≥50 cells considered valid for statistical analysis of radiation response profiles.

4.6. Cell Proliferation Assay (CCK-8)

Following trypsinization, cells were plated at 1.5×10³ cells/well in 96-well plates and cultured for 18 h prior to exposure to ionizing radiation. Cellular proliferation was assessed at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h post-irradiation using CCK-8 assays prepared with fresh medium:CCK-8 reagent (Dojindo, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan)(9:1 v/v). Original medium was replaced with 100 µl assay solution followed by 1.5 h incubation (37°C, 5% CO₂), with subsequent optical density measurements at 450 nm using a spectrophotometric microplate reader. Survival curves were generated based on triplicate absorbance values normalized to non-irradiated controls.

4.7. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), with RNA concentration and purity quantified via a K5600 ultra-micro spectrophotometer (Kaiao, Beijing, China), where samples demonstrating OD260/OD280 ratios between 1.8–2.0 were considered suitable for downstream applications. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the HiScript III RT SuperMix reverse transcription kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) following manufacturer protocols. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis was conducted on the MX3000P system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using Applied Biosystems™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) with thermal cycling parameters optimized per manufacturer specifications. Relative expression levels of lncRNAs and mRNAs were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method normalized to GAPDH as an endogenous control, with primer sequences for reverse transcription and amplification detailed in

Supplementary Table S1.

4.8. Western Blot Analysis

Cellular proteins were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and quantified via BCA assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham, MA, USA), with protein concentrations normalized to 1 μg/μL using loading buffer prior to SDS-PAGE separation and subsequent electroblotting onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 8% non-fat milk for 2 h at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution: GAPDH (1:5000, AC002, ABclonal, Wuhan, China), β-Tubulin (1:10000, 10094-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), CPS1 (1:1000, ab18197, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), XRCC1 (1:3000, 21468-1-AP, Proteintech), ATM (1:1000, Y170, Abcam), phospho-ATM-Ser1981 (1:1000, ab81292, Abcam) and γH2AX(1:500, 05-636, Millipore, Germany). After three TBST washes, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000, RGAR001/RGAM001, Proteintech) for 1 h at room temperature prior to chemiluminescent detection using ECL substrate (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA).

4.9. Immunofluorescence Assay

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min, and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by three gentle PBS washes. Primary antibodies diluted in PBS (γH2AX, 1:500, 05-636, Millipore, Germany) were applied (500 μl/well) and incubated overnight at 4°C under light-protected conditions. After three PBS washes, cells were incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies (CoraLite® Plus 488-Goat Anti-Rabbit, 1:500, RGAR002; CoraLite® Plus 594-Goat Anti-Mouse, 1:500, RGAM004; Proteintech, Wuhan, China) for 1 h in darkness. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1 μg/ml) for 20 min at room temperature, followed by three final PBS rinses prior to confocal microscopy imaging (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using standardized exposure settings for cross-sample comparability.The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Primer sequence, Table S2: Co-expression network profiling of CPS1-associated genes in lung cancer.

Author Contributions

Z.-Y.C.: Methodology, investigation, data curation, writing - original draft, visualization. T.-T.W.: Methodology, data curation, visualization. F.-M.T.: Data Curation. R.Z.: Data Curation. H.-J.L.: Data Curation. J.-J.L.: Formal analysis. S.-S.X.: Data Curation. H.-Y.G.: Data Curation. X.-F.Z.: Conceptualization, validation, resources, supervision. C.-Y.L.: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

Funding

This study was funded in part by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1103502), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82370115).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Lin Liu for her valuable contributions in analyzing the experimental data of this manuscript. We deeply appreciate her support and assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Derrien, T.; Johnson, R.; Bussotti, G.; Tanzer, A.; Djebali, S.; Tilgner, H.; Guernec, G.; Martin, D.; Merkel, A.; Knowles, D.G.; et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res 2012, 22, 1775–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A.B.; Tsitsipatis, D.; Gorospe, M. Integrated lncRNA function upon genomic and epigenomic regulation. Mol Cell 2022, 82, 2252–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulitsky, I.; Bartel, D.P. lincRNAs: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell 2013, 154, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmuthuge, N.; Guan, L.L. Noncoding RNAs: Regulatory Molecules of Host-Microbiome Crosstalk. Trends Microbiol 2021, 29, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, S.; Coller, J. RNA in unexpected places: long non-coding RNA functions in diverse cellular contexts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013, 14, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kopp, F.; Chang, T.C.; Sataluri, A.; Chen, B.; Sivakumar, S.; Yu, H.; Xie, Y.; Mendell, J.T. Noncoding RNA NORAD Regulates Genomic Stability by Sequestering PUMILIO Proteins. Cell 2016, 164, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munschauer, M.; Nguyen, C.T.; Sirokman, K.; Hartigan, C.R.; Hogstrom, L.; Engreitz, J.M.; Ulirsch, J.C.; Fulco, C.P.; Subramanian, V.; Chen, J.; et al. The NORAD lncRNA assembles a topoisomerase complex critical for genome stability. Nature 2018, 561, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.A.; Shah, N.; Wang, K.C.; Kim, J.; Horlings, H.M.; Wong, D.J.; Tsai, M.C.; Hung, T.; Argani, P.; Rinn, J.L.; et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature 2010, 464, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.P.; Bartolomei, M.S. Genomic imprinting in mammals. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.X.; Ma, J.X. Promoter-associated RNAs and promoter-targeted RNAs. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012, 69, 2833–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Kang, J.; Hu, M.; Li, N.; Sun, K.; Zhao, Y. Enhancer RNAs in transcriptional regulation: recent insights. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1205540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, R.B.; Wardman, P. Biological chemistry of reactive oxygen and nitrogen and radiation-induced signal transduction mechanisms. Oncogene 2003, 22, 5734–5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.J.; Wang, X.J.; Wu, Q.J.; Liu, C.; Fan, C.D. Induction of G1 Cell Cycle Arrest in Human Glioma Cells by Salinomycin Through Triggering ROS-Mediated DNA Damage In Vitro and In Vivo. Neurochemical Research 2016, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Rogers, L.; Suchowerska, N.; Choe, D.; Al-Dabbas, M.A.; Narula, R.S.; Lyons, J.G.; Sved, P.; Li, Z.; Dong, Q. Sensitization of prostate cancer to radiation therapy: Molecules and pathways to target. Radiother Oncol 2018, 128, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zeng, Z.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, X.; Li, S.; Sun, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; et al. LncRNA PCAT1 activates SOX2 and suppresses radioimmune responses via regulating cGAS/STING signalling in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Transl Med 2022, 12, e792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Shankavaram, U.; Bylicky, M.; Dalo, J.; Scott, K.; Aryankalayil, M.J.; Coleman, C.N. Profiling mRNA, miRNA and lncRNA expression changes in endothelial cells in response to increasing doses of ionizing radiation. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 19941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.M.; Bylicky, M.; Chopra, S.; Coleman, C.N.; Aryankalayil, M.J. Long and short non-coding RNA and radiation response: a review. Transl Res 2021, 233, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shao, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Kong, X.; Jiang, J. A novel long noncoding RNA SP100-AS1 induces radioresistance of colorectal cancer via sponging miR-622 and stabilizing ATG3. Cell Death Differ 2023, 30, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Huang, C.; Li, J.; Gao, T.; Lin, Z.; Yao, T. Long non-coding RNA urothelial cancer associated 1 regulates radioresistance via the hexokinase 2/glycolytic pathway in cervical cancer. Int J Mol Med 2018, 42, 2247–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ren, P.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, B.; Yu, D.; Sun, X. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 increases the radiosensitivity of A549 cells through interaction with the miR-21/PTEN/Akt axis. Oncol Rep 2020, 43, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Rong, Z.; Dai, L.; Qin, C.; Wang, S.; Geng, W. LncRNA LINC01134 Contributes to Radioresistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Regulating DNA Damage Response via MAPK Signaling Pathway. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 791889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Pinera, P.; Kocak, D.D.; Vockley, C.M.; Adler, A.F.; Kabadi, A.M.; Polstein, L.R.; Thakore, P.I.; Glass, K.A.; Ousterout, D.G.; Leong, K.W.; et al. RNA-guided gene activation by CRISPR-Cas9-based transcription factors. Nat Methods 2013, 10, 973–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, T.I.; Mikkelsen, N.S.; Gao, Z.; Foßelteder, J.; Pabst, G.; Axelgaard, E.; Laustsen, A.; König, S.; Reinisch, A.; Bak, R.O. Targeted regulation of transcription in primary cells using CRISPRa and CRISPRi. Genome Res 2021, 31, 2120–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardon, F.M.; McDiarmid, T.A.; Page, N.F.; Daza, R.M.; Martin, B.K.; Domcke, S.; Regalado, S.G.; Lalanne, J.B.; Calderon, D.; Li, X.; et al. Multiplex, single-cell CRISPRa screening for cell type specific regulatory elements. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 8209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, W.; Yau, E.; Hui, H.; Singh, P.K.; Achuthan, V.; Young Karris, M.A.; Engelman, A.N.; Rana, T.M. Genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 transcriptional activation screen identifies a histone acetyltransferase inhibitor complex as a regulator of HIV-1 integration. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, 6687–6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Li, M.; Ling, X.; Liao, J.; Zhou, X.; Fang, S.; Zhao, H.; Zhong, W.; Yuan, X. Genome-Scale CRISPR-Cas9 Transcriptional Activation Screening in Metformin Resistance Related Gene of Prostate Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 616332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Niu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Teng, X.; Sun, X.; et al. NONCODEV5: a comprehensive annotation database for long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, D308–d314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, M.P.; Sinha, R.; Mukhtar, M.S.; Athar, M. Epigenetic regulation in the pathogenesis of non-melanoma skin cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 83, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoja, S.; Nitzahn, M.; Truong, B.; Lambert, J.; Willis, B.; Allegri, G.; Rüfenacht, V.; Häberle, J.; Lipshutz, G.S. A constitutive knockout of murine carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 results in death with marked hyperglutaminemia and hyperammonemia. J Inherit Metab Dis 2019, 42, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh, R.M.; Mansy, S.S.; Nessim, I.G.; Hosni, H.N.; El Hindawi, A.; Hassanein, M.H.; AbdelFattah, A.S. Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) as a prognostic marker in chronic hepatitis C infection. Apmis 2019, 127, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Li, C.F.; Lin, C.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Sheu, M.J.; Lin, L.C.; Chen, T.J.; Wu, T.F.; Hsing, C.H. Overexpression of CPS1 is an independent negative prognosticator in rectal cancers receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Tumour Biol 2014, 35, 11097–11105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wu, T.; Li, P.; Lian, Q.; Xu, S.; Gu, J.; Chen, L.; et al. Deficiency of Carbamoyl Phosphate Synthetase 1 Engenders Radioresistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Deubiquitinating c-Myc. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2023, 115, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Paull, T.T. Cellular functions of the protein kinase ATM and their relevance to human disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 796–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, L.; Xie, S.; Tu, L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, K.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; et al. SERPINE2/PN-1 regulates the DNA damage response and radioresistance by activating ATM in lung cancer. Cancer Lett 2022, 524, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lin, M.; Li, Z.; Shen, Z.; Yin, S.; Zheng, Y.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; et al. Targeting ATM enhances radiation sensitivity of colorectal cancer by potentiating radiation-induced cell death and antitumor immunity. J Adv Res 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, D.; Zhai, Y.; Pan, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, R.; Yu, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Glycometabolic reprogramming-induced XRCC1 lactylation confers therapeutic resistance in ALDH1A3-overexpressing glioblastoma. Cell Metab 2024, 36, 1696–1710.e1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, S.; He, Z.; Chen, Y. Cytosine-phosphate-guanine oligodeoxynucleotides alleviate radiation-induced kidney injury in cervical cancer by inhibiting DNA damage and oxidative stress through blockade of PARP1/XRCC1 axis. J Transl Med 2023, 21, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Lin, S.H.; Welsh, J.W.; Wei, X.; Jin, H.; Mohan, R.; Liao, Z.; Xu, T. Radiation-induced lymphopenia during chemoradiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer is linked with age, lung V5, and XRCC1 rs25487 genotypes in lymphocytes. Radiother Oncol 2021, 154, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çeliktas, M.; Tanaka, I.; Tripathi, S.C.; Fahrmann, J.F.; Aguilar-Bonavides, C.; Villalobos, P.; Delgado, O.; Dhillon, D.; Dennison, J.B.; Ostrin, E.J.; et al. Role of CPS1 in Cell Growth, Metabolism and Prognosis in LKB1-Inactivated Lung Adenocarcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017, 109, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham-Danis, C.; Gehrke, S.; Danis, E.; Rozhok, A.I.; Daniels, M.W.; Gao, D.; Collins, C.; Paola, J.T.D.; D'Alessandro, A.; DeGregori, J. Urea Cycle Sustains Cellular Energetics upon EGFR Inhibition in EGFR-Mutant NSCLC. Mol Cancer Res 2019, 17, 1351–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).