Submitted:

02 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Crispr Site-Directed Mutagenesis Experiment

Gel Electrophoresis

PCR- Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism(RFLP)

Dot Blot (DNA Southwestern Blot)

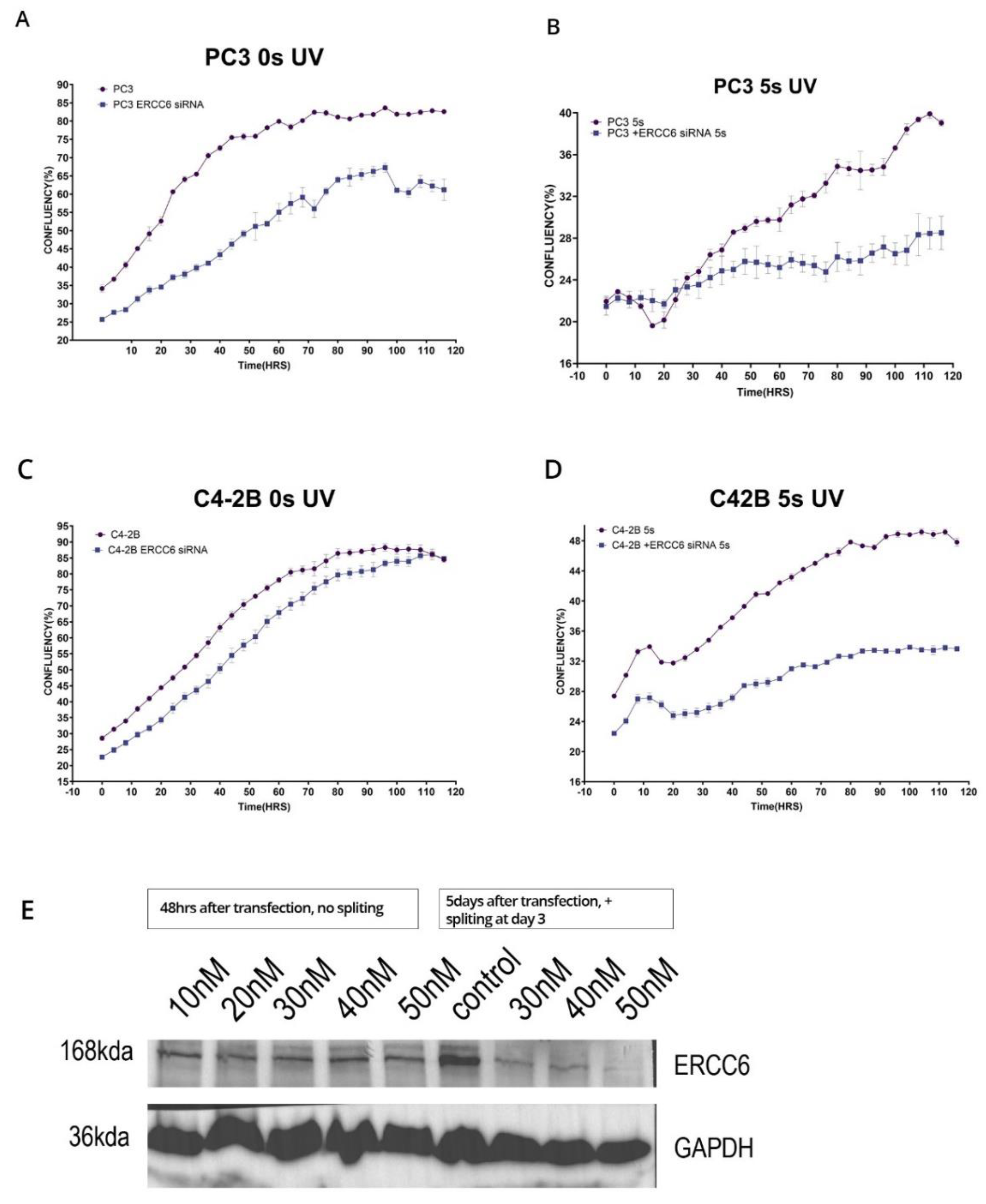

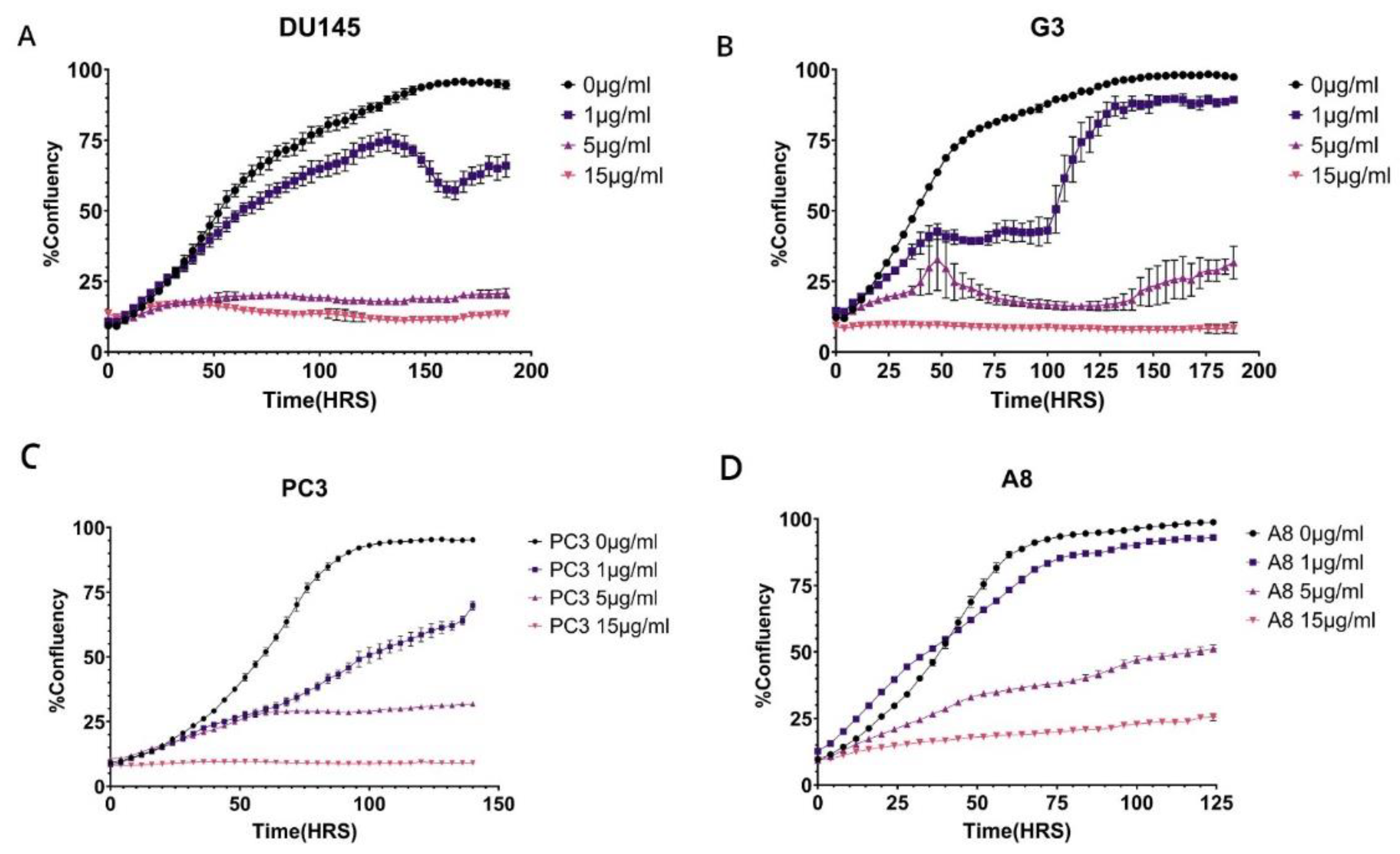

Proliferation Assay

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussion

-

Transcription-Coupled DNA Repair (TC-NER):

- ○

- ERCC6 plays a central role in detecting and initiating the repair of DNA lesions that block transcription.

- ○

- When RNA polymerase II stalls at DNA damage (such as UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers), ERCC6 helps recruit repair factors to remove the lesion and resume transcription.

-

Chromatin Remodeling:

- ○

- ERCC6 possesses ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling activity, allowing it to alter nucleosome positioning.

- ○

- This activity is crucial for providing repair machinery access to DNA in compact chromatin regions.

-

Transcription Regulation:

- ○

- In addition to DNA repair, ERCC6 can regulate gene expression by interacting with transcription machinery.

- ○

- It influences RNA polymerase 1 and RNA polymerase II pausing and restart, ensuring proper transcription resumption after repair.

-

Interaction with Other Repair Proteins:

- ○

- ERCC6 interacts with other TC-NER factors such as CSA (ERCC8), XPG, TFIIH, and UVSSA to coordinate the repair process.

-

Response to Oxidative Stress:

- ○

- ERCC6 has been implicated in the repair of oxidative DNA damage, not just UV-induced lesions.

- ○

- It helps maintain mitochondrial function and cellular redox balance under stress conditions.

-

Role in Disease:

- ○

- Mutations in ERCC6 cause Cockayne Syndrome, a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by growth failure, neurodegeneration, and premature aging.

- ○

- It is also linked to other neurodevelopmental and progeroid syndromes.

Conclusions

Funding

Declarations: Authors’ contributions

IRB

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations List

References

- Fan, T.; Shi, T.; Sui, R.; Wang, J.; Kang, H.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, Y. The chromatin remodeler ERCC6 and the histone chaperone NAP1 are involved in apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease-mediated DNA repair. The Plant Cell 2024, 36, 2238–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulou, Z.; Papaspyropoulos, A.; Lagopati, N.; Myrianthopoulos, V.; Georgakilas, A.G.; Fousteri, M.; Kotsinas, A.; Gorgoulis, V.G. Cockayne Syndrome Group B (CSB): The Regulatory Framework Governing the Multifunctional Protein and Its Plausible Role in Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakarla, M.; ChallaSivaKanaka, S.; Hayward, S.W.; Franco, O.E. Race as a Contributor to Stromal Modulation of Tumor Progression. Cancers 2021, 13, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, P.C.; Huang, S.P.; Liu, C.H.; Lin, T.Y.; Cho, Y.C.; Lai, Y.L.; Wang, S.C.; Yeh, H.C.; Chuu, C.P.; Chen, D.N.; et al. Identification of DNA Damage Repair-Associated Prognostic Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer Using Transcriptomic Data Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, S.; Omlin, A.; Higano, C.; Sweeney, C.; Martinez Chanza, N.; Mehra, N.; Kuppen, M.C.P.; Beltran, H.; Conteduca, V.; Vargas Pivato de Almeida, D.; et al. Activity of Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Patients With Advanced Prostate Cancer With and Without DNA Repair Gene Aberrations. JAMA network open 2020, 3, e2021692–e2021692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Van Gent, D.C.; Incrocci, L.; Van Weerden, W.M.; Nonnekens, J. Role of the DNA damage response in prostate cancer formation, progression and treatment. Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases 2020, 23, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, P.; Xu, W.; Murphy, D.; James, P.; Sandhu, S. Relevance of DNA damage repair in the management of prostate cancer. Current problems in cancer 2017, 41, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bono, J.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abida, W.; Campbell, D.; Patnaik, A.; Shapiro, J.D.; Sautois, B.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Voog, E.G.; Bryce, A.H.; McDermott, R.; Ricci, F.; et al. Non-BRCA DNA Damage Repair Gene Alterations and Response to the PARP Inhibitor Rucaparib in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Analysis From the Phase II TRITON2 Study. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26, 2487–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perše, M. Cisplatin Mouse Models: Treatment, Toxicity and Translatability. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Anbalagan, M.; Baddoo, M.; Chellamuthu, V.K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Woods, C.; Jiang, W.; Moroz, K.; Flemington, E.K.; Makridakis, N. Somatic mutations in the DNA repairome in prostate cancers in African Americans and Caucasians. Oncogene 2020, 39, 4299–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.-H.; Chiu, C.-F.; Wang, H.-C.; Wu, H.-C.; Tsai, R.-Y.; Tsai, C.-W.; Wang, R.-F.; Wang, C.-H.; Tsou, Y.-A.; Bau, D.-T. Significant Association of ERCC6 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms with Bladder Cancer Susceptibility in Taiwan. Anticancer Research 2009, 29, 5121–5124. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, I.S.; Chaudhary, K.; Vy, H.M.T.; Bafna, S.; Kim, S.; Won, H.H.; Loos, R.J.F.; Cho, J.; Pasquale, L.R.; Nadkarni, G.N.; et al. Genetic pleiotropy of ERCC6 loss-of-function and deleterious missense variants links retinal dystrophy, arrhythmia, and immunodeficiency in diverse ancestries. Hum Mutat 2021, 42, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q.; Yu, H.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Zheng, J. Genetic Association of ERCC6 rs2228526 Polymorphism with the Risk of Cancer: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022, 2662666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.J.; Arab, L.; Steck, S.E.; Fontham, E.T.; Schroeder, J.C.; Bensen, J.T.; Mohler, J.L. Obesity and prostate cancer aggressiveness among African and Caucasian Americans in a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011, 20, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baurick, T.; Younes, L.; Meiners, J. Welcome to "Cancer Alley" where toxic air is about to get worse. Propublica 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, M.I.; Ghosh, I.; Singh, V.; Chen, J.; Zhu, H.; De Benedetti, A. NEK1 Phosphorylation of YAP Promotes Its Stabilization and Transcriptional Output. Cancers 2020, 12, 3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basei, F.L.; Meirelles, G.V.; Righetto, G.L.; Dos Santos Migueleti, D.L.; Smetana, J.H.; Kobarg, J. New interaction partners for Nek4.1 and Nek4.2 isoforms: from the DNA damage response to RNA splicing. Proteome Sci 2015, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, C.D. Strand discrimination in DNA mismatch repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2021, 105, 103161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoir, S.; Ogundepo, O.; Yu, X.; Shi, R.; De Benedetti, A. Exploiting TLK1 and Cisplatin Synergy for Synthetic Lethality in Androgen-Insensitive Prostate Cancer. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, L.A. A mutator phenotype in cancer. Cancer Res 2001, 61, 3230–3239. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Bhoir, S.; Chikhale, R.V.; Hussain, J.; Dwyer, D.; Bryce, R.A.; Kirubakaran, S.; De Benedetti, A. Generation of phenothiazine with potent anti-TLK1 activity for prostate cancer therapy. Iscience 2020, 23, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Jaiswal, P.K.; Ghosh, I.; Koul, H.K.; Yu, X.; De Benedetti, A. Targeting the TLK1/NEK1 DDR axis with Thioridazine suppresses outgrowth of androgen independent prostate tumors. International journal of cancer 2019, 145, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Jaiswal, P.K.; Ghosh, I.; Koul, H.K.; Yu, X.; De Benedetti, A. The TLK1-Nek1 axis promotes prostate cancer progression. Cancer letters 2019, 453, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinata, N.; Fujisawa, M. Racial Differences in Prostate Cancer Characteristics and Cancer-Specific Mortality: An Overview. World J Mens Health 2022, 40, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eule, C.J.; Hu, J.; Al-Saad, S.; Collier, K.; Boland, P.; Lewis, A.R.; McKay, R.R.; Narayan, V.; Bosse, D.; Mortazavi, A.; et al. Outcomes of Second-Line Therapies in Patients With Metastatic de Novo and Treatment-Emergent Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer: A Multi-Institutional Study. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2023, 21, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corn, P.G.; Heath, E.I.; Zurita, A.; Ramesh, N.; Xiao, L.; Sei, E.; Li-Ning-Tapia, E.; Tu, S.M.; Subudhi, S.K.; Wang, J.; et al. Cabazitaxel plus carboplatin for the treatment of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancers: a randomised, open-label, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019, 20, 1432–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, F.-J.; Lin, C.; Tian, H.; Lin, W.; You, B.; Lu, J.; Sahasrabudhe, D.; Huang, C.-P.; Yang, V.; Yeh, S.; et al. Preclinical studies using cisplatin/carboplatin to restore the Enzalutamide sensitivity via degrading the androgen receptor splicing variant 7 (ARv7) to further suppress Enzalutamide resistant prostate cancer. Cell Death & Disease 2020, 11, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).