Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) represents a significant global health burden as the second most common malignancy worldwide, with approximately 1.4 million new cases and 375,000 deaths annually [

1]. This pervasive disease has far-reaching implications for public health, healthcare systems, and individual patient outcomes. In the United States, it ranks as the second leading cause of cancer death among men and the third leading cause of cancer death in the general population, with projections indicating continued increases in both incidence and mortality rates [

2]. These statistics underscore the urgent need for improved prevention, detection, and treatment strategies.

A crucial aspect of PCa characterization is accomplished using the Gleason Score, a grading system utilized in prostate cancer pathology to assess the aggressiveness of the cancer based on histological patterns observed in a biopsy. This system, which ranges from 2 to 10, is derived by scoring the most and second most common patterns from 1 to 5 and summing those scores. The Gleason Score plays a pivotal role in clinical decision-making, helping predict prognosis and guide treatment decisions [

3]. Its widespread adoption has significantly contributed to standardizing PCa assessment and management across healthcare settings.

Previous studies showed a strong correlation between the occurrence of PCa and family history and ethnicity [

4]. This observation, coupled with the fact that PCa is often associated with other familial cancers, particularly breast and ovarian cancers [

5] has led researchers to hypothesize that there is a significant genetic component in the disease mechanism. Furthermore, it suggests that common genetic factors could be responsible for the development of prostate cancer across different cancer syndromes.

The genetic basis of PCa has been increasingly elucidated through comprehensive studies of hereditary cancer syndromes, particularly Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (HBOC) and Lynch Syndrome (LS) [

6]. These investigations have provided valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying PCa development and progression, opening new avenues for targeted therapies and personalized medicine approaches.

Epidemiological studies indicate that 5% to 10% of all prostate cancer (PCa) cases, and up to 40% of those occurring earlier in life, are linked to dominantly inherited susceptibility genes with high penetrance. Research has demonstrated significant associations between pathogenic germline variants in homologous recombination repair (HRR) genes, notably BRCA1 and BRCA2, and more aggressive disease presentations and poorer outcomes [

6,

7,

8]. These genetic alterations not only increase the risk of developing PCa but also influence its clinical course and treatment response. Furthermore, specific demographic factors have been correlated with positive genetic testing results, providing valuable criteria for identifying high-risk individuals. These factors include Jewish-Ashkenazi descent, age at diagnosis, family history of related cancers, and high Gleason scores (≥7) [

9,

10]. The identification of these risk factors has enabled more targeted genetic screening strategies, potentially improving early detection and intervention rates.

In response to these findings, organizations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the Israeli Medical Genetics Association have established genetic testing criteria for PCa patients. Current guidelines recommend testing for patients with a carrier probability exceeding 10%, including those with high-risk disease (Gleason score ≥7), metastatic disease, Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, or relevant family history [

7,

8]. These guidelines aim to optimize the use of genetic testing resources while maximizing the identification of individuals at increased risk for hereditary PCa.

However, the real-world utility of this risk-stratified approach remains largely unexplored, particularly in diverse populations and healthcare settings. To address this knowledge gap, our multi-centered retrospective study evaluates the effectiveness of current testing criteria by characterizing the germline genetic landscape among PCa patients in two Israeli medical centers located in different regions of the country. By analysing demographic and clinical factors influencing the prevalence of disease-causing genetic variations, this study aims to provide valuable insights into the applicability and potential limitations of current genetic testing guidelines.

The findings of this investigation have the potential to inform and refine genetic testing strategies for PCa, ultimately contributing to improved patient care, more accurate risk assessment, and the development of targeted prevention and treatment approaches.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patient Cohort This retrospective study was conducted over a four-and-a-half-year period, from August 2019 through February 2024. The study population comprised all male patients who were referred for genetic counseling due to a diagnosis of prostate cancer at the genetic institutions of Belinson Hospital and Assuta (Ashdod) Hospital during the study timeframe.

All participants in the study were offered the opportunity to undergo germline genetic testing. The testing modalities included either the targeted Israeli founder mutation panel or a more comprehensive, multi-gene next-generation sequencing (NGS) commercial panel. The NGS panel included an extensive set of genes for which pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) variants are recognized as established risk factors for prostate cancer, such as ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, EPCAM, HOXB13, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, NBN, PMS2, TP53, RAD51D, and PALB2. Detailed demographic and clinical information for each patient was retrieved from their medical records and computerized patient management systems.

Sequencing and Variant Interpretation For this patient cohort, the sample type utilized for genetic testing was blood samples exclusively. The classification of identified variants as pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), variants of unknown significance (VOUS), or increased-risk alleles was determined based on the guidelines established by the American College of Medical Genetics. A positive test result was defined as the detection of a P/LP variant, which could be either a low penetrance variant (LPV) or a high penetrance variant (HPV). For the LPV category, the study included variants that have been previously defined as risk alleles, such as APC:c.3920T>A;p.Ile1307Lys and CHEK2:c.1283C>T;P.Ser428Phe. Conversely, P or LP variants exhibiting mosaic results or heterozygosity in a recessive context were deemed as negative findings.

Data Collection. For each participating patient in the study, a comprehensive set of data points was collected, including the following:

Ancestry: Patients were classified based on their Ashkenazi descent as either Full (three or more grandparents of Ashkenazi descent), Mixed (two grandparents of Ashkenazi descent), or None (less than two grandparents of Ashkenazi descent).

Age

Gleason score

Age at diagnosis

Known cases of cancer and/or prostate cancer in the family

Type of genetic test taken (founder mutation panel or NGS panel)

Variants identified through the genetic testing, categorized as pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), variants of unknown significance (VOUS), and increased-risk alleles

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive Statistics: For categorical variables, summary tables provided the sample size (n) and relative frequencies (%). For continuous variables, summary tables included the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) or median (Me) and interquartile range (IQR), depending on the normality of the data distribution as assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Pearson’s chi-squared tests were used to examine the correlations between the study groups and the categorical parameters. The effects of continuous variables on the groups were assessed using an independent sample t-test or a Mann-Whitney non-parametric test, based on the sample size and data normality distribution. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to investigate the correlations between the genetic results of P+PL/Low, Ashkenazi ethnicity, and family cancer history while adjusting for age, presenting odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) (

Table 4). A p-value of 5% or less was considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 29 (IBM).

Results

Patient Clinical and Demographic Characteristics.

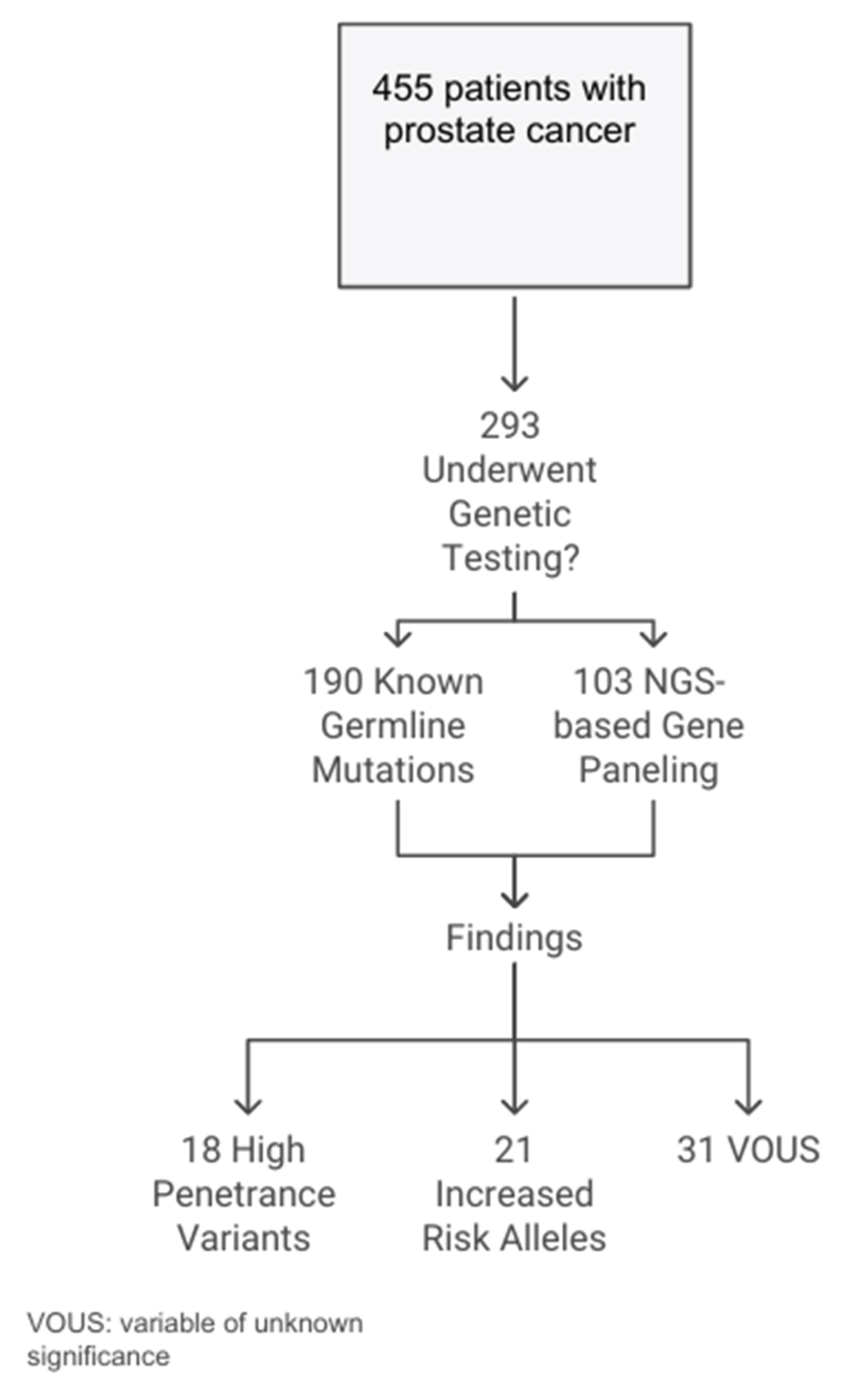

During the study period from August 2019 to February 2024, a total of 455 Jewish patients with prostate cancer underwent genetic counseling at the Belinson and Assuta Ashdod genetic centers. The median age at diagnosis was 67.8 years, with a standard deviation of 8.6 years. Of the 455 patients, 193 (42.4%) were of Ashkenazi Jewish descent (having at least two grandparents of Ashkenazi origin), and 93 (20.4%) had metastatic disease. A family history of ovarian, breast, or pancreatic malignancies was reported in 13 (2.9%) patients. The cohort included 362 (79.6%) individuals with non-metastatic disease, and a Gleason score of ≥ 8 was reported in 285 (62.6%) of them (

Figure 1,

Table 1).

Germline Genetic Testing Outcomes.

Of the 455 patients in the cohort, 293 (64.4%) underwent germline genetic testing. Significant variations were observed in several parameters between the tested and non-tested groups. The tested group was younger (67.1 ± 8.3 years), had a higher proportion of Ashkenazi descent (136, 46.4%), and reported a greater occurrence of malignancy in the family (12, 4.1%) compared to the non-tested group.

Of the 293 tested men, 190 (64.8%) underwent testing for the presence of known germline founder mutations, while the remaining 103 (35.2%) underwent germline genetic panel testing using NGS-based commercial gene panels.

Overall, 13.3% of the tested patients had a positive genetic finding reported. Specifically, 18 (6.1% of the tested cohort) presented with a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in a high-penetrance gene (in MSH6, BRCA1, or BRCA2), and 21 (7.2%) had results associated with an increased-risk allele. Additionally, variants of uncertain significance (VOUS) were reported in 39 (13.3%) patients. Interestingly, half (50%) of the patients diagnosed with pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in high-penetrance genes using NGS panels had a founder mutation, while the other half (50%) consisted of unique variants (

Figure 1).

Ethnicity and Genetic Testing Outcomes.

Of the 455 participants, 232 (51%) had partial (at least two grandparents are Ashkenazi) or complete (all four grandparents are Ashkenazi) Ashkenazi ancestry, while 223 (49%) were of non-Ashkenazi descent. No statistically significant differences were found based on ethnicity when comparing age, family history of cancer, and disease progression (

Table 2).

When evaluating the results of genetic testing based on Ashkenazi Jewish ethnicity, Gleason score, and the presence of cancer in the family, the only notable difference in positive outcomes was between the group with a family history of cancer (besides prostate cancer) and those without (

Table 3).

Correlation Between Risk Factors and Positive Test Results

The statistical analysis aimed to identify correlations between a positive result from a germline test and specific exposure variables, including age, Gleason score, family history of malignancy, and Ashkenazi descent.

The analysis showed that the only significant correlation was between a positive test result and a family history of cancer (p=0.041), while age and ethnicity were not found to be significant factors (

Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression model for the correlation between the genetic results of P+PL/Low and Ashkenazi ethnicity, cancer in the family, with adjustment for age.

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression model for the correlation between the genetic results of P+PL/Low and Ashkenazi ethnicity, cancer in the family, with adjustment for age.

| Exposure variable |

Type of variable and categories |

OR |

95% CI |

p |

| Ethnicity |

Binary—none vs. Ashkenazi |

0.70 |

0.33-1.45 |

0.335 |

| Any cancer in the family |

Binary—Yes vs. No |

3.81 |

1.05-13.77 |

0.041 |

| Age |

Continuous—years |

0.99 |

0.94-1.03 |

0.490 |

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study stands as a unique contribution to the field, offering real-life insights into the germline genetic landscape of prostate cancer (PCa) and distinguishing between high- and low-penetrant variants. Our investigation evaluates the significance of demographic and clinical factors related to pathogenic germline variants within this patient cohort, providing a comprehensive analysis that has not been previously undertaken in this context.

Prevalence of Germline Variants

Our analysis revealed a notable prevalence of germline pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants within our cohort, with 13.3% of patients testing positive. This figure can be further broken down into 6.1% harboring variants in high-penetrance genes and 7.2% carrying variants of low penetrance. These findings align closely with prior studies, reinforcing the significant role of germline mutations in PCa pathogenesis, particularly among high-risk populations. For instance, Nicolosi et al. (2019) [

9], reported a 17.2% prevalence of germline mutations in men with PCa referred for genetic testing. The consistency between our results and previous research underscores the importance of genetic factors in PCa development and progression.

The high prevalence of germline variants observed in our study has significant implications for clinical practice and genetic counseling. It suggests that a substantial proportion of PCa patients may benefit from genetic testing, potentially leading to more personalized treatment approaches and improved risk assessment for family members. Furthermore, this finding highlights the need for broader implementation of genetic screening protocols in PCa management.

Correlation with Risk Factors

When comparing our cohort results with established risk factors identified in the literature, such as Gleason Score, age of onset, family history, and ethnicity, we uncovered some intriguing and unexpected findings. Contrary to prevailing expectations, our analysis demonstrated that only a family history of cancer significantly correlated with positive genetic test results. This observation reinforces the hereditary component of PCa. It aligns with literature suggesting that familial aggregation of cancer, particularly breast and ovarian cancers, is a strong predictor of germline mutations in PCa patients [

5,

10]. However, it is noteworthy that other well-established risk factors, including the Gleason score, age at diagnosis, and ethnicity [

4,

11]. Did not show significant associations with positive test results in our study. This divergence from previous findings raises important questions about the universality of these risk factors and the potential influence of population-specific genetic backgrounds or environmental factors.

Ethnicity and Germline Variants

Our cohort included a high proportion of Ashkenazi Jewish patients (51.3%), reflecting the demographic composition of the Israeli population. Interestingly, we found that the prevalence of high-penetrance mutations did not significantly differ between Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi individuals. This observation contrasts with previous studies that have highlighted higher mutation rates in Ashkenazi populations, particularly due to founder mutations in genes like BRCA1 and BRCA2 [

6]. The lack of statistical significance regarding the ethnicity factor in our study may be attributed to the way the Ashkenazi group was defined in our cohort. We classified individuals as Ashkenazi if they had at least two grandparents of Ashkenazi descent. This broad definition may have diluted the genetic homogeneity typically associated with Ashkenazi populations in other studies. Due to the limited size of our participant cohort, it was not feasible to create a sufficiently large subgroup of individuals with four grandparents of Ashkenazi descent to allow for meaningful statistical analysis.

This finding highlights the complexity of studying genetic predisposition in ethnically diverse populations and emphasizes the need for more nuanced approaches to defining and analyzing ethnic subgroups in genetic studies. Future research with larger, more homogeneous subgroups is crucial to clarify the role of ethnicity in PCa susceptibility and to provide more precise risk assessments for different ethnic groups.

Unique vs. Founder Mutations

The discovery that 50% of pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants identified through next-generation sequencing (NGS) in our prostate cancer (PCa) cohort were unique rather than founder mutations represents a significant finding with far-reaching implications for genetic testing in PCa.

This observation challenges the adequacy of founder mutation panels in capturing the full spectrum of germline variants in PCa patients. While founder mutation panels are valuable for detecting common, well-characterized mutations, they may fail to identify rare or population-specific variants that could be equally important in disease risk and progression. Consequently, relying solely on these panels might lead to an underestimation of the true prevalence of P/LP variants in PCa patients.

The high proportion of unique variants underscores the critical role of NGS in providing a more comprehensive genetic profile. NGS allows for the detection of both known founder mutations and novel or rare variants, offering a more complete picture of an individual’s genetic risk. This suggests that NGS should be considered more routinely in genetic testing protocols for PCa patients to ensure that clinically relevant genetic alterations are not missed.

However, it’s important to note that our study’s conclusions are limited by the relatively small number of NGS-tested patients (35.2%). This restricted sample size constrains our ability to draw definitive conclusions about the true prevalence and spectrum of unique variants in the broader PCa population. It highlights the need for larger studies with more extensive use of NGS to validate these findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the genetic landscape in PCa.

The presence of numerous unique variants also has important clinical implications. It suggests that some patients may be missed by current testing strategies, potentially leading to underestimation of genetic risk and missed opportunities for targeted interventions or family counseling. Furthermore, it emphasizes the importance of conducting genetic studies in diverse populations to capture the full range of genetic variations associated with PCa risk.

Study Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Its retrospective design introduces potential biases in patient selection and data collection, especially regarding self-reported family histories. Additionally, the limited use of NGS panels constrains our understanding of the prevalence of unique variants and variants of uncertain significance (VOUS). To address these limitations and validate our findings, future research should focus on: prospectively designed studies with standardized data collection methods, larger cohorts with more diverse demographics and clinical backgrounds, and more extensive use of NGS panels across the entire study population. Implementing standardized protocols for collecting and verifying family history information would also be beneficial. These strategies would improve the reliability, completeness, and applicability of the results, providing a stronger basis for clinical decision-making and genetic counseling in prostate cancer management.

Implications for Public Health and Clinical Practice

The findings of our study have a significant impact on public health initiatives and clinical practices related to prostate cancer:

Promoting Awareness of Genetic Testing: Our study highlights the urgent need for public health efforts to increase awareness and knowledge about genetic testing for prostate cancer. This is particularly important, as organizations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the Israeli Medical Genetics Association already recommend genetic testing for high-risk groups.

Prioritizing Access to Genetic Counseling and Testing: Given the recognized value of genetic testing for prostate cancer risk assessment, it is essential to prioritize access to genetic counseling and testing services. This is especially crucial for high-risk populations, as identified by current guidelines.

Addressing Gaps in Genetic Testing Coverage: Currently, in Israel, genetic testing for prostate cancer is only funded by the health system for patients with metastatic disease who are eligible for treatment with PARP inhibitors. This leaves a significant gap in access to genetic testing for individuals with localized or early-stage prostate cancer.

Enhancing Early Detection and Personalized Care: Addressing the gap in genetic testing coverage could provide significant benefits, including:

• Better early detection of prostate cancer in high-risk individuals

• Allowing more personalized treatment plans based on genetic risk profiles

• Supporting targeted prevention and intervention strategies for at-risk populations

By implementing these public health and clinical practice recommendations, we can work towards a more comprehensive and equitable approach to prostate cancer management. This would empower individuals and healthcare providers to make informed decisions, leading to earlier diagnosis, more personalized treatment, and potentially better outcomes for patients and their families.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study highlights the critical role of genetic factors in diagnosing and managing PCa, particularly in populations with identifiable risk factors. Establishing comprehensive protocols for genetic screening based on demographic and familial history could improve outcomes for patients and their families, providing a clearer pathway toward targeted prevention and intervention strategies. Future research using NGS is essential to elucidate the prevalence of pathogenic variants, both founder and unique, in PCa patients and to refine genetic testing guidelines accordingly.

By addressing these key findings, healthcare providers and public health stakeholders can work towards a more nuanced and practical approach to PCa risk assessment, prevention, and treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, RS, BS, and YG.; methodology, RS, YG, and ASN.; formal analysis, ASN.; investigation, RS, BS, IK, ML, NA, HS.; writing—original draft preparation, RS, BS.; writing—review and editing, RS, YG, IK.; supervision, RS, YG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards (Belinson and Assuta Ashdod) (No. 0160-17-RMC, 0066-23-AAA).

Informed Consent Statement

As this was an anonymized retrospective study, Patient consent was waived as approved by both institutional review boards

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCa |

Prostate Cancer |

| NGS |

Next Generation Sequencing |

| P |

Pathogenic |

| LP |

Likely Pathogenic |

| VOUS |

variants of uncertain significance |

References

- Doan DK, Schmidt KT, Chau CH, Figg WD. Germline Genetics of Prostate Cancer: Prevalence of Risk Variants and Clinical Implications for Disease Management. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13.(9). [CrossRef]

- Statistics USC. 1999–2011 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group., 2015.

- Epstein JI, Zelefsky MJ, Sjoberg DD, et al. A Contemporary Prostate Cancer Grading System: A Validated Alternative to the Gleason Score. Eur Urol 2016;69(3):428-35. [CrossRef]

- Daniyal M, Siddiqui ZA, Akram M, et al. Epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15(22):9575-8.

- Leongamornlert D, Saunders E, Dadaev T, et al. Frequent germline deleterious mutations in DNA repair genes in familial prostate cancer cases are associated with advanced disease. Br J Cancer 2014;110(6):1663-72. [CrossRef]

- Oh M, Alkhushaym N, Fallatah S, et al. The association of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with prostate cancer risk, frequency, and mortality: A meta-analysis. Prostate 2019;79(8):880-895.

- Daly MB, Pal T, Maxwell KN, et al. NCCN Guidelines(R) Insights: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 2.2024. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2023;21(10):1000-1010.

- Daly MB, Pal T, Berry MP, et al. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021;19(1):77-102. [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi P, Ledet E, Yang S, et al. Prevalence of Germline Variants in Prostate Cancer and Implications for Current Genetic Testing Guidelines. JAMA Oncol 2019;5(4):523-528. ttps://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6760.

- Perdana NR, Mochtar CA, Umbas R, Hamid AR. The Risk Factors of Prostate Cancer and Its Prevention: A Literature Review. Acta Med Indones 2016;48(3):228-238.

- Jayadevappa R, Chhatre S, Johnson JC, Malkowicz SB. Association between ethnicity and prostate cancer outcomes across hospital and surgeon volume groups. Health Policy 2011;99(2):97-106. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).