Submitted:

21 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

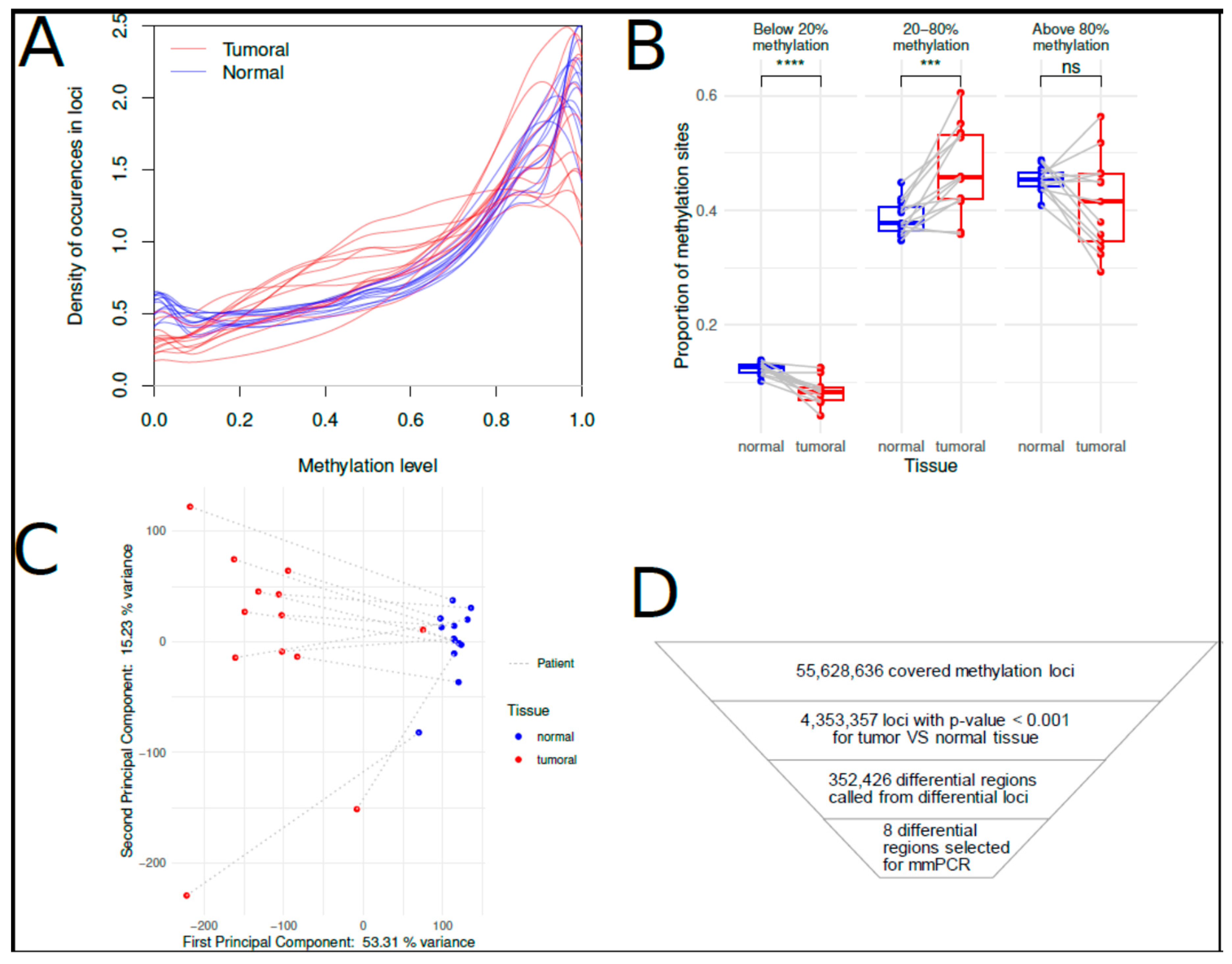

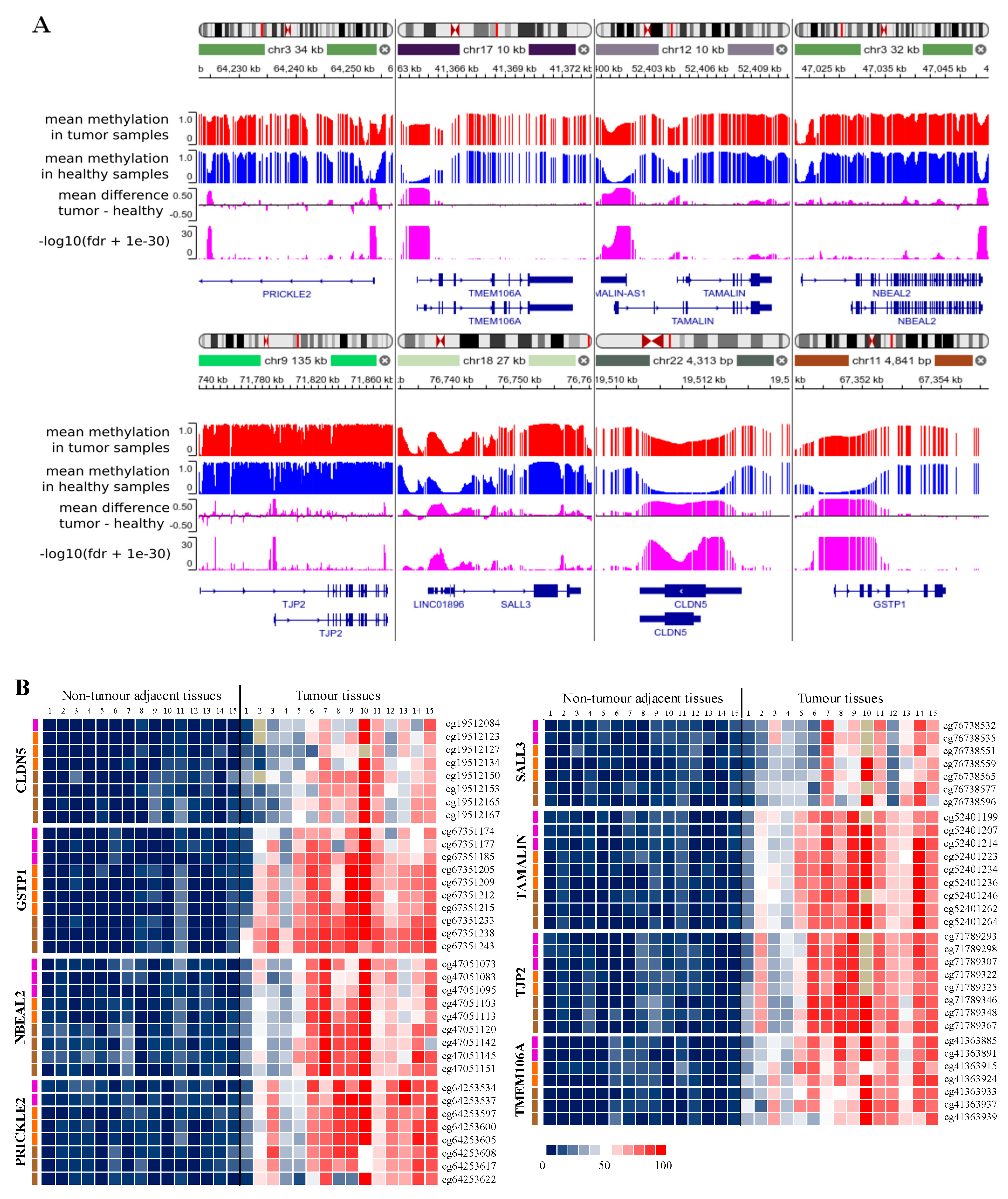

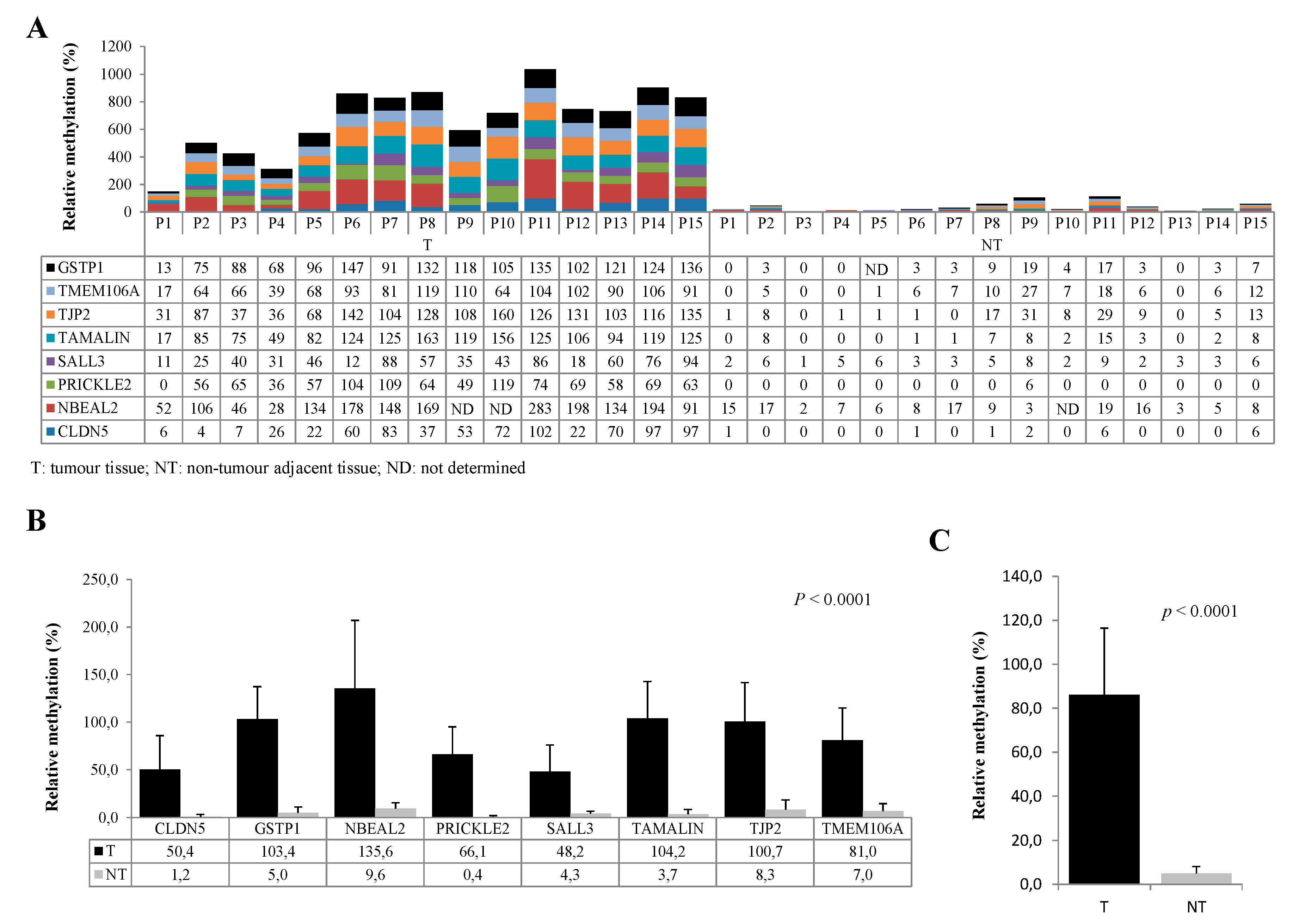

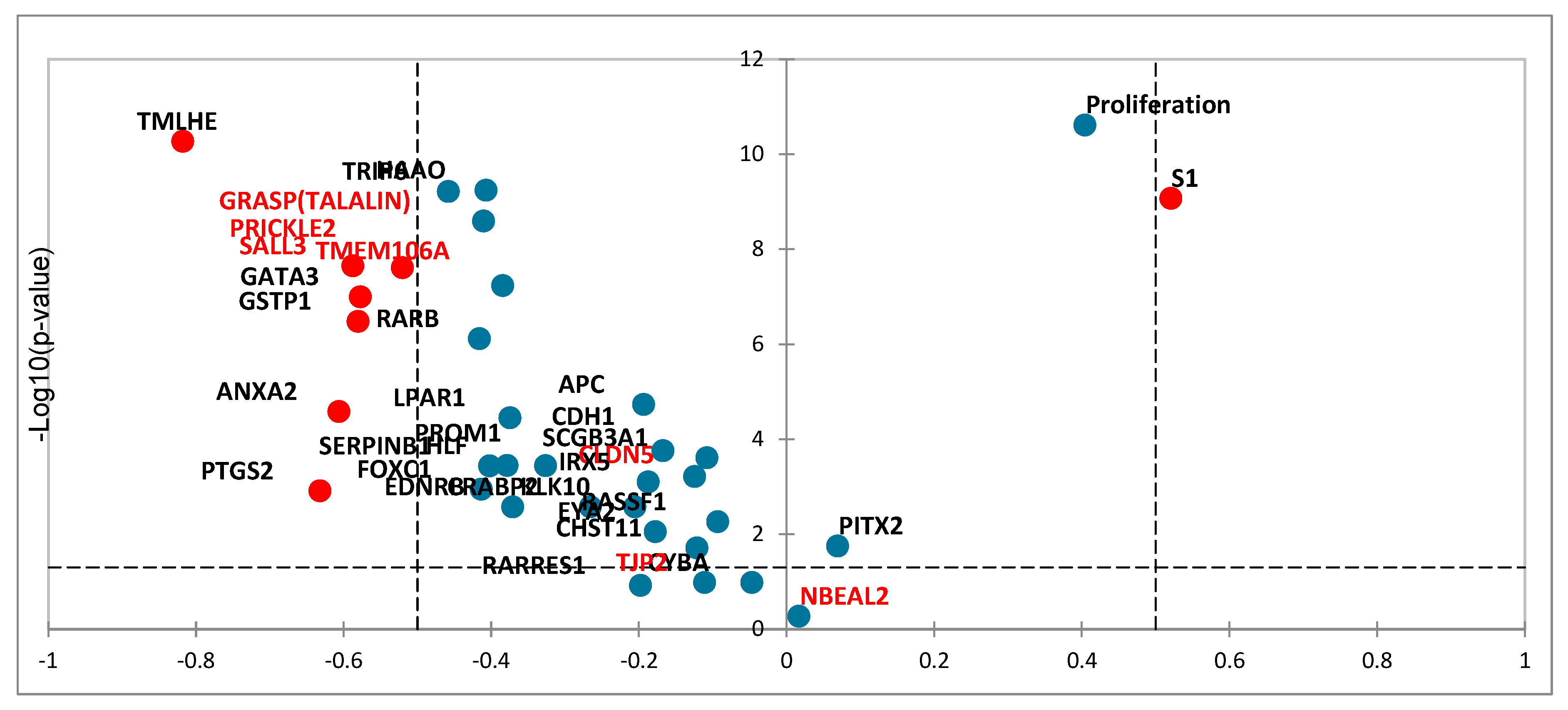

Prostate cancer represents the second most frequently diagnosed malignant tumour in males. Serum PSA is used as a screening tool for prostate cancer. However, there are limitations to this approach due to the number of false positives it generates, which can result in overdiagnosis and over-treatment. The objective of this study was to identify accurate DNA methylation markers for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. In order to achieve this objective, whole-methylome sequencing was performed on tumour tissue samples, and the identified epi-genetic markers were validated using multiplex methylation-specific PCR. Abstract: Background/Objectives: Prostate cancer (PCa) remains the leading cause of cancer deaths in men. Serum Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) test is widely used for PCa screening. This method is controversial, as it can lead to over-diagnosis and over-treatment. Using DNA methyl-ation sequencing, our aim was to identify new sensitive and specific epigenetic markers in PCa tissue. Methods: DNA methylome analysis was performed from 15 paired tumors (T) and non-tumour adjacent (NT) prostate tissues by Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit (EM-seq). Results: 66 CpGs sites representing eight genes were identified as hypermethylated in T versus NT, and were confirmed by multiplex methylation-specific PCR (MM-SPCR). A very good correlation between EM-Seq and MM-SPCR results was observed (Pearson's correlation of 0.93). As an indicator of the overall methylation status, the percentage of methylated reference (PMR) was measured for each marker. Overall, a significant difference was found in the mean PMR values of T vs. NT (86.2 30.3% vs. 5.0 3.2%, p < 0.0001). Area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated from PMRs for each marker, with AUC values ranging from 0.987 to 1.0. This is an indication of the very high diagnostic accuracy of these markers in the tissue of prostate cancer patients. Conclusions: A total of 66 hypermethylated CpG sites were identified in paired prostate tumour tissue in comparison to non-tumour adjacent tissue by EM-seq. They represent a set of eight genes, including CLDN5, GSTP1, NBEAL2, PRICKLE2, SALL3, TAMALIN, TJP2 and TMEM106A, which could be used as diagnostic markers for prostate cancer.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tissue Sample Collection and Patient Information

2.2. DNA Isolation

2.3. DNA Methylation Sequencing Analysis

2.4. Quantification of Methylation Levels by MM-SPCR

2.5. Array RNA Expression Validation

2.6. Gene Expression Validation Using Spatial Transcriptomics

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Cytosine Methylation Using EM-seq

3.3. Evaluation of Diagnostic Performance with MM-SPCR

3.4. Tissue RNA Expression of Candidate Genes Using Affimetryx Arrays Data Set and In Situ Expression using Spatial Transcriptomics Visium 10X

3.4.1. Tissue RNA Expression of Candidate Genes Using Affimetryx Arrays Data Set

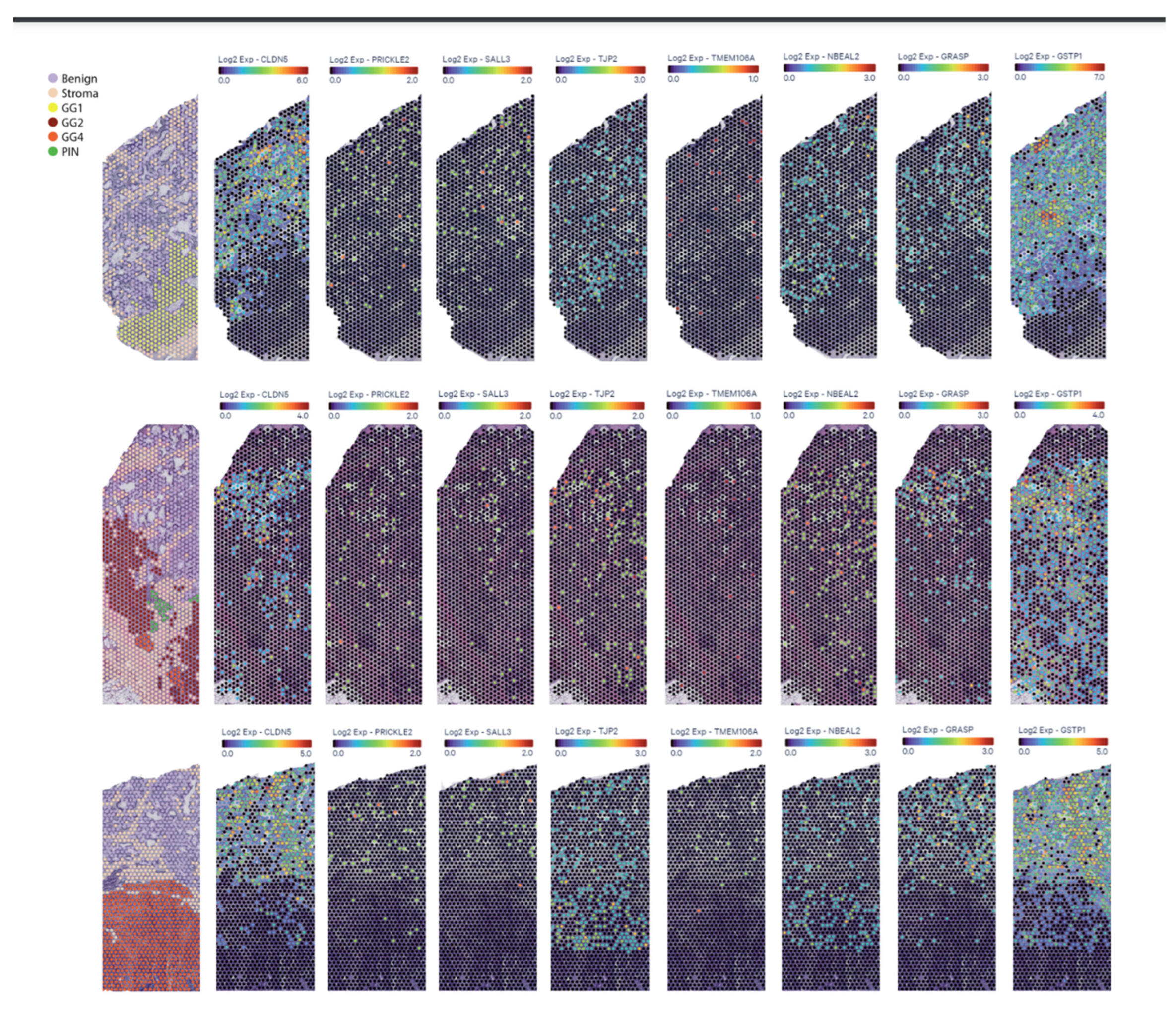

3.4.2. In Situ RNA Expression Using Spatial Transcriptomics Visium 10X

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; J. Ferlay, R. L. Siegel, M. Laversanne, I. Soerjomataram, A. Jemal.; et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71(3):209–249. [CrossRef]

- Van Poppel, H.; Albreht, T.; Basu, P.; et al. Serum PSA-based early detection of prostate cancer in Europe and globally: past, present and future. Nature Reviews Urology. 2022, 19, 562–572.

- Merriel, SWD.; Pocock, L., Gilbert, E.; et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for the detection of prostate cancer in symptomatic patients. BMC Medicine. 2022, 20:54. [CrossRef]

- Catalona, WJ.; Smith, DS.; Ratliff, TL.; et al. Measurement of Prostate-Specific Antigen in Serum as a Screening Test for Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991, 324:1156-1161.

- Bernal-Soriano, MC.; Parker, LA.; Lopez-Garrigos, M.; et al. Factors associated with false negative and false positive results of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and the impact on patient health: Cohort study protocol. Medicine. 2019, 98(40):e17451.

- Esteller, M. Epigenetics in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1148–1159.

- Baylin, P.; Jones, A. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome-biological and translational implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011, 11, 726–734.

- Jeronimo, C.; Bastian, PJ.; Bjartell, A.; Carbone, GM.; Catto, JW.; Clark, SJ.; Henrique, R.; Nelson, WG.; Shariat.; SF. Epigenetics in prostate cancer: biologic and clinical relevance. European urology. 2011, 60(4):753–766. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Buckles, E.; Estrada, J.; et al. Aberrant DNA Methylation and Prostate Cancer. Curr Genomics. 2011, 12(7):486-505.

- Massie, CE.; Mills IG.; Lynch, AG. The importance of DNA methylation in prostate cancer development. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 2017, 166:1–15.

- Erickson, A.; He, M.; Berglund, E.; Marklund, M.; Mirzazadeh, R.; Schultz, N.; Kvastad, L.; Andersson, A.; et al. Spatially resolved clonal copy number alterations in benign and malignant tissue. Nature. 2022, 608, 360–367. [CrossRef]

- Dillinger, T.; Sheibani-Tezerji R.; Pulverer, W.; Stelzer, I.; Hassler, MR.; Scheibelreiter, J.; Pérez Malla, CU.; et al. Identification of tumor tissue-derived DNA methylation biomarkers for the detection and therapy response evaluation of metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer in liquid biopsies. Mol Cancer. 2022, Jan 3;21(1):7.

- Rouprêt, M.; Hupertan, V.; Catto, JW.; Yates, DR.; Rehman, I.; Proctor, LM.; Phillips, J.; Meuth, M.; Cussenot, O.; Hamdy FC. Promoter hypermethylation in circulating blood cells identifies prostate cancer progression. Int J Cancer. 2008, Feb 15;122(4):952-6.

- Li, Y.; Meng, L.; Shi, T.; Ren, J.; Deng, Q. Diagnosis and prognosis potential of four gene promoter hypermethylation in prostate cancer. Cell Biol Int. 2021, Jan;45(1):117-126. [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, V.; Clegg, W.; Meek, S.; Lenz, L.; Flake, DD.; Ronan, T.; Kornilov, M.; Horsch, D.; Scheer, M.; Farber, D.; Zalaznick, H.; Cussenot, O.; Compérat, E.; Cancel-Tassin, G.; et al. Development and validation of a cell cycle progression signature for decentralized testing of men with prostate cancer. Biomark Med. 2022, Apr;16(6):449-459.

- Kamoun, A.; Cancel-Tassin, G.; Fromont, G.; Elarouci, N.; Armenoult, L.; Ayadi, M.; Irani, J.; Leroy, X.; Villers A.; et al. Comprehensive molecular classification of localized prostate adenocarcinoma reveals a tumour subtype predictive of non-aggressive disease. Ann Oncol. 2018, Aug 1;29(8):1814-1821. [CrossRef]

- Hoppers, A.; Williams, L.; Ponnaluri, VKC.; et al. Enzymatic Methyl-seq: Next Generation Methylomes. J Biomol Tech. 2020, 31:S15.

- Vaisvila, R.; Ponnaluri, VKC.; Sun, Z.; and al. Enzymatic methyl sequencing detects DNA methylation at single-base resolution from picograms of DNA. Genome Res. 2021, 17;31(7):1280-1289. [CrossRef]

- Füllgrabe, J.; Gosal, WS.; Creed, P.; et al. Simultaneous sequencing of genetic and epigenetic bases in DNA. Nature Biotechnology. 2023, 41, 1457-1464. [CrossRef]

- Costa, VL.; Henrique, R.; Jeronimo C. Epigenetic markers for molecular detection of prostate cancer. Disease Markers. 2007, 23:31-41.

- Goering, W.; Kloth, M.; Schulz, WA. DNA methylation changes in prostate cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2012, 863:47-66.

- Lammie, GA. ; Peters, G. Chromosome 11q13 abnormalities in human cancer. Cancer Cells. 1991, 3(11):413-20.

- Gurioli, G.; Martignano, F.; Salvi, S.; Costantini, M.; Gunelli, R.; Casadio, V. GSTP1 Methylation in Cancer: A Liquid Biopsy Biomarker? Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2018, 56, 702–717.

- Martignano, F.; Gurioli, G.; Salvi, S.; Calistri, D.; Costantini, M.; Gunelli, R et al. GSTP1 Methylation and Protein Expression in Prostate Cancer: Diagnostic Implications. Disease Markers. 2016, 10:4358292.

- Jian, C.; Guoqing, L.; Jie, Y.; Linwei, L.; Yue, T.; Haoran, W.; Bang, L.; Lihong, D.; Jialu, T.; Yongli, C and Lan, Y. GSTP1 and cancer: Expression, methylation, polymorphisms and signaling. International Journal of oncology. 2020, 56: 867-878.

- Singh, AB.; Sharma, A.; Dhawan. Claudin Family of Proteins and Cancer: An Overview. Journal of Oncology. 2010, 541957.

- Coradini, D.; Casarsa, C.; Oriana, S. Epithelial cell polarity and tumorigenesis: new perspectives for cancer detection and treatment. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2011, 32: 552–564.

- Sawada, N.; Murata, M.; Kikuchi, K.; et al. Tight junctions and human diseases. Medical Electron Microscopy. 2023, Volume 36, no. 3, 147–156.

- Martin, TA.; Jiang, WG. Loss of tight junction barrier function and its role in cancer metastasis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009, Volume 1788, no. 4, 872–891.

- Martin, TA.; Mason, MD.; Jiang, WG. Tight junctions in cancer metastasis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2011, 16,898.

- Yuang, G.; Jiang, L.; Chen, Q. Comprehensive analysis of expression and prognostic value of the claudin family in human breast cancer. Aging. 2021, Volume 13, no. 6.

- Cherradi, S.; Martineau, P.; Gongora, C.; et al. Claudin gene expression profiles and clinical value in colorectal tumors classified according to their molecular subtype. Cancer Management and Research. 2019, 11, 1337–1348.

- Huang, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Downregulation of Claudin5 promotes malignant progression and radioresistance through Beclin1-mediated autophagy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Transl Med. 2023, 11;21(1):379.

- Yang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Du, C.; Wu, Y. Bioinformatics analysis of differentially expressed genes in tumor and paracancerous tissues of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Dis. 2020, 12:7355–64.

- Karnati, HK.; Panigrahi, M.; Shaik, NA.; et al. Down regulated expression of Claudin-1 and Claudin-5 and up regulation of β-catenin: Association with Human Glioma Progression. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014, 13(8): 1413-1426. [CrossRef]

- Väre, P.; Loikkanen, I.; Hirvikoski, P.; Vaarala, MH.; Soini, Y. Low claudin expression is associated with high Gleason grade in prostate adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2008, 19,25.

- Seo, KW.; Kwon, YK.; Kim, BH.; et al. Correlation between Claudins Expression and Prognostic Factors in Prostate Cancer. Korean Journal of Urology. 2010, 51:239-244.

- Chlenski, A.; Ketels, KV.; Korovaitseva, GI.; et al. Organization and expression of the human zo-2 gene (tjp-2) in normal and neoplastic tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000, 2;1493(3):319-24.

- Chihara, Y.; Hanai, Y.; Fujimoto, H.; et al. Diagnostic markers of urothelial cancer based on DNA methylation analysis. BMC Cancer. 2013, 13:275.

- Zabarovsky, ER.; Lerman, MI.; Minna, JD. Tumor suppressor genes on chromosome 3p involved in the pathogenesis of lung and other cancers. Oncogene. 2002, 7;21(45):6915-35.

- Senchenko, VN.; Kisseljova, NP.; Ivanova, TA.; et al. Novel tumor suppressor candidates on chromosome 3 revealed by NotI-microarrays in cervical cancer. Epigenetics. 2013, 8:4, 409–420.

- Kashuba, V.; Dmitriev, AA.; Krasnov, GS. NotI Microarrays: Novel Epigenetic Markers for Early Detection and Prognosis of High Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 13352-13377.

- Kluth, M.; Graunke, M.; Möller-Koop, C.; et al. Deletion of 18q is a strong and independent prognostic feature in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016, 27; 7(52): 86339-86349.

- Yu, J.; Zhu, T.; Wang, Z.; et al. A novel set of DNA methylation markers in urine sediments for sensitive/specific detection of bladder cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 15,13(24):7296-304.

- Wei, X.; Zhang, S.; Cao, D.; et al. Aberrant Hypermethylation of SALL3 with HPV Involvement Contributes to the Carcinogenesis of Cervical Cancer. Plos One. 2015, 23;10(12):e0145700.

- Misawa, K.; Kanazawa, T.; Mochizuki, D.; et al. Genes located on 18q23 are epigenetic markers and have prognostic significance for patients with head and neck cancer. Cancers. 2009, 11,401.

- Misawa, K.; Mochizuki, D.; Imai, A.; et al. Epigenetic silencing of SALL3 is an independent predictor of poor survival in head and neck cancer. Clin Epigenetics. 2017, 12:9:64. [CrossRef]

- Shikauchi, Y.; Saiura, A.; Kubo, T.; et al. SALL3 interacts with DNMT3A and shows the ability to inhibit CpG island methylation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cell Biol. 2009, 29(7):1944-58.

- Yang, XX.; Sun, JZ.; Li, FX.; et al. Aberrant methylation and downregulation of sall3 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2012, 7;18(21):2719-26.

- Imai, A.; Mochizuki, D.; Misawa, Y.; et al. SALL2 Is a Novel Prognostic Methylation Marker in Patients with Oral Squamous Carcinomas: Association with SALL1 and SALL3 methylation status. DNA Cell. Biol. 2019, 38(7):678-687.

- Sato, N.; Fukushima, N.; Maitra, A.; Matsubayashi, H.; Yeo, CJ.; Cameron, JL.; Hruban, RH.; et Goggins M. Discovery of novel targets for aberrant methylation in pancreatic carcinoma using high-throughput microarrays. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 3735 – 3742.

- Kishibuchi, R.; Kondo, K.; Soejima, S.; et al. DNA methylation of GHSR, GNG4, HOXD9 and SALL3 is a common epigenetic alteration in thymic carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2020, 56(1):315-326.

- Bjerre, MT.; Strand, SH.; Norgaard, M., et al. Aberrant DOCK2, GRASP, HIF3A and PKFP hypermethylation has potential as a prognostic biomarker for prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 20, 1173.

- Mitchell, S.; Ross, JP.; Drew, HR.; et al. A panel of genes methylated with high frequency in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014, 14:54.

- Shen, J.; Le Fave, C.; Sirosh, I.; et al. Integrative epigenomic and genomic filtering for methylation markers in hepatocellular carcinomas. BMC Med Genomics. 2015, 8:28. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, N.; Yasui, K.; Dohi, O.; et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2016, 35(4):2228-36.

- Babalyan, KA.; Sultanov, R.; Generozov, EV.; Zakharzhevskaya, NB.; Sharova, EI.; Peshkov, MN et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation in prostate cancer using the technology of Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (HM450. Voprosy Onkologii. 2016, 62(1) :122-132.

- Geybels, MS.; Zhao, S.; Wong, CJ.; et al. Epigenomic profiling of DNA methylation in paired prostate cancer versus adjacent benign tissue. Prostate. 2015, 75(16):1941–1950.

- Xu, D.; Qu, L.; Hu, J.; Li, G.; Lu, P.; Ma, D.; Guo, M.; Chen, Y. Transmembrane protein 106a is silenced by promoter region hypermethylation and suppresses gastric cancer growth by inducing apoptosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2014, 18:1655-1666.

- Shi, S.; Wang, B.; Wan, J.; et al. TMEM106A transcriptionally regulated by promoter methylation is involved in invasion and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2022, 54(7): 1008-1020.

- Liu, J.; Zhu, H. TMEM106A inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and induces apoptosis of lung cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2019, 120(5):7825-7833.

- Wu, C.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; and al. TMEM106a is a Novel Tumor Suppressor in Human Renal Cancer. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2017, 42:853-864. [CrossRef]

| N° ID | Age PR | ISUP | pT | Surgical margin | PSA level (ng/ml) |

| 1 | 65 | 2 | T2c | Negative | ND |

| 2 | 65 | 3 | T2c | Negative | 5 |

| 3 | 70 | 2 | T3a | Negative | ND |

| 4 | 60 | 1 | T2c | Negative | 4.4 |

| 5 | 67 | 5 | T2c | Negative | 4.3 |

| 6 | 70 | 5 | T3a | Negative | 8.3 |

| 7 | 70 | 5 | T3a | Positive | 14 |

| 8 | 68 | 1 | T2 | Negative | 6.59 |

| 9 | 64 | 1 | T2 | Negative | 9.40 |

| 10 | 69 | 3 | T2cR1 | Positive | 10 |

| 11 | 69 | 1 | T2 | Negative | 3.79 |

| 12 | 62 | 1 | T2 | Negative | 7.19 |

| 13 | 73 | 1 | T3aR1 | Positive | 11.44 |

| 14 | 71 | 1 | T2cR1 | Positive | 6.89 |

| 15 | 59 | 1 | T2c | Negative | 5.3 |

| Gene | Oligonucleotide sequence (5’→ 3’) | CpG | DNA size, bp | |

| ALBUMIN | Fw Rv Pr |

GGGATGGAAAGAATTTTATGTT AAACAAACTAACCCCAAATTCT Vic-AGGGTTTTTATAATTTA |

0 0 0 |

76 |

| CLDN5 | Fw Rv Pr |

TTTGGTAGTTGAAGTTAGGGAAATAACG CCGCGACTAAAACAACGACG 6Fam-AACGACTACCGAACGAAA |

1 4 3 |

112 |

| GSTP1 | Fw Rv Pr |

TGGGGTCGGCGGGAGTTC ATAATCCCGCCCCGCTCC 6Fam-AATCACGACGCCGACCGCTCTT |

3 3 4 |

84 |

| NBEAL2 | Fw Rv Pr |

CGGGGTTTTTCGGTTTTTAAGTC AAAAAAACCGAAACCGCCG 6Fam-CGTTAAAGTACGAGGGTCGT |

3 3 3 |

88 |

| PRICKLE2 | Fw Rv Pr |

TAGGAGTAAATATGTTTTTGCGTCG AATTTCCCGAACCGACAAAAAC Ned-CGCAACGTCGAAACA |

2 3 3 |

117 |

| SALL3 | Fw Rv Pr |

AGAATGGAAGGGAGTTCGTCG CCGCCTAAAAAAAAAATCCCC 6Fam-TCGAACCCGACCTAAC |

2 2 3 |

83 |

| TAMALIN | Fw Rv Pr |

TTTTTCGTTGTTGCGAAGGTC ATAAAACGCGAAATTAAAAACCACC Vic-CGTTTGTATATCGCGTTTAG |

3 3 3 |

78 |

| TJP2 | Fw Rv Pr |

AAATGTCGGTGCGAGGAGATC CGACACAAAAAAACACTTACGCG Ned-ACCTAACAACTCCCGCCGA |

3 3 2 |

82 |

| TMEM106A | Fw Rv Pr |

TTTGAGGGGAGTGTTCGTTTTC AAAAACCTTACCCGCGAACG 6Fam-ACAACGACAAAAACGAA |

2 3 2 |

83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).