Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Photoanode Material and Treated Solutions

2.3. Photoelectrochemical Characterization

2.3. Photoelectrochemical Oxidation

2.4. Analytical Techniques

2.4. Indicators of the Reactor Performance

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Photoelectrochemical Characterization

3.2. Photoelectrochemical Oxidation of the Isolated Pollutants

3.2.1. Degradation

3.2.2. Mineralization

3.3. Photoelectrochemical Oxidation of the Synthetic Mixture

3.3.1. Degradation

3.3.2. Mineralization

3.3.2. Energy Consumption

3.3.3. Comparison with a commercial BDD anode

4. Conclusions

- The photoelectrochemical characterization of the photoanode revealed an immediate photocurrent response upon illumination, which depended on both the applied bias potential and the light intensity, a behavior typical of semiconductor materials. Based on these results, the light intensity was selected and kept constant for the subsequent experiments.

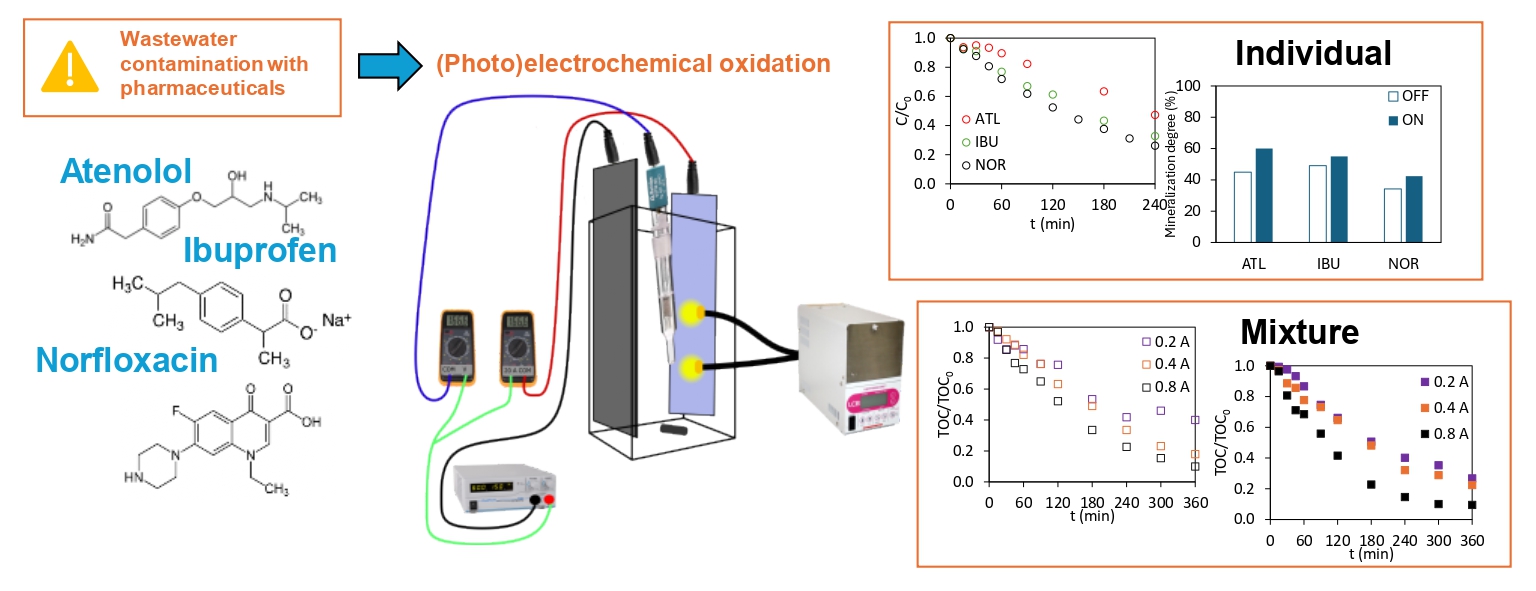

- Degradation of individual pharmaceuticals showed significant improvement under illumination. Likewise, the mineralization of the solution was also enhanced with light exposure, though always lower than degradation for all pharmaceuticals under study, a fact that emphasizes the complexity of their degradation pathway. Photolysis tests confirmed that ATL, IBU and NOR are stable under light irradiation.

- In the pharmaceutical mixture, HPLC-MS analysis revealed that light exposure also improved removal efficiency. The amount of electrogenerated •OH increased with operation intensity, and with that, greater mineralization of the solution was observed. It was concluded that the effect of the photochemical generation of •OH on mineralization may be masked by its improved electrochemical production when operation intensity is increased.

- Overall, the BDD anode exhibits lower energy consumption. The ceramic material, when acting as photoanode, exhibits a significant reduction in energy consumption, reaching values comparable to those of the commercial BDD anode.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOPs | Advanced Oxidation Processes |

| ATL | Atenolol |

| BDD | Boron-doped diamond |

| C | Concentration |

| EIC | Extracted Ion Chromatograms |

| ETOC | Specific energy consumption |

| HPLC-MS | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry |

| IBU | Ibuprofen |

| MCE | Mineralization current efficiency |

| NOR | Norfloxacin |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

References

- Nguyen, M.K.; Lin, C.; Bui, X.T.; Rakib, M.R.J.; Nguyen, H.L.; Truong, Q.M.; Hoang, H.G.; Tran, H.T.; Malafaia, G.; Idris, A.M. Occurrence and fate of pharmaceutical pollutants in wastewater: Insights on ecotoxicity, health risk, and state–of–the-art removal. Chemosphere 2024, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohan Khizer, M.; Saddique, Z.; Imran, M.; Javaid, A.; Latif, S.; Mantzavinos, D.; Momotko, M.; Boczkaj, G. Polymer and graphitic carbon nitride based nanohybrids for the photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment – A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javid, N.; Honarmandrad, Z.; Malakootian, M. Ciprofloxacin removal from aqueous solutions by ozonation with calcium peroxide. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 174, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlsma, L.; Pitarch, E.; Fonseca, E.; Ibáñez, M.; Botero, A.M.; Claros, J.; Pastor, L.; Hernández, F. Investigation of pharmaceuticals in a conventional wastewater treatment plant: Removal efficiency, seasonal variation and impact of a nearby hospital. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-Lor, E.; Sancho, J. V.; Serrano, R.; Hernández, F. Occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment plants at the Spanish Mediterranean area of Valencia. Chemosphere 2012, 87, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Official Journal of the European Union. DIRECTIVE (EU) 2024/3019 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL OF 27 NOVEMBER 2024 CONCERNING URBAN WASTEWATER TREATMENT. 2024. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/C/2023/250/oj.

- Babu, D.S.; Srivastava, V.; Nidheesh, P. V.; Kumar, M.S. Detoxification of water and wastewater by advanced oxidation processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.Y.N.; Goulart, L.A.; Mascaro, L.H.; Alves, S.A. A critical view of the contributions of photoelectrochemical technology to pharmaceutical degradation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y. Fan; Wang, G.B.; Kuo, D.T.F.; Chang, M. ling; Shih, Y. hsin. Photoelectrocatalytic degradation of the antibiotic sulfamethoxazole using TiO2/Ti photoanode. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 186, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristino, V.; Longobucco, G.; Marchetti, N.; Caramori, S.; Bignozzi, C.A.; Martucci, A.; Molinari, A.; Boaretto, R.; Stevanin, C.; Argazzi, R.; Dal Colle, M.; Bertoncello, R.; Pasti, L. Photoelectrochemical degradation of pharmaceuticals at β25 modified WO3 interfaces. Catal. Today 2020, 340, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaranjani, T.; Rajakarthihan, S.; Karthigeyan, A.; Bharath, G. Sustainable photoelectrocatalytic oxidation of antibiotics using Ag–CoFe2O4@TiO2 heteronanostructures for eco-friendly wastewater remediation. Chemosphere 2024, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, M.H.A.; Santos, A.M.; Wong, A.; Moraes, C.A.F.; Grosseli, G.M.; Nascimento, O.R.; Fadini, P.S.; Moraes, F.C. Photoelectrocatalytic removal of antibiotic ciprofloxacin using a photoanode based on Z-scheme heterojunction. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masekela, D.; Hintsho-Mbita, N.C.; Ntsendwana, B.; Mabuba, N. Thin Films (FTO/BaTiO3/AgNPs) for Enhanced Piezo-Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue and Ciprofloxacin in Wastewater. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 24329–24343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimolade, B.O.; Arotiba, O.A. Towards visible light driven photoelectrocatalysis for water treatment: Application of a FTO/BiVO4/Ag2S heterojunction anode for the removal of emerging pharmaceutical pollutants. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Abad, J.; Mora-Gómez, J.; García-Gabaldón, M.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V. Comparison between an electrochemical reactor with and without membrane for the nor oxidation using novel ceramic electrodes. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Abad, J.; Mora-Gómez, J.; García-Gabaldón, M.; Montañés, M.T.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V. Enhanced Atenolol oxidation by ferrites photoanodes grown on ceramic SnO2-Sb2O3 anodes. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeddin; Hilal, H.S.; Pecquenard, B.; Marcus, J.; Mansouri, A.; Labrugere, C.; Subramanian, M.A.; Campet, G. Simultaneous doping of Zn and Sb in SnO2 ceramics: Enhancement of electrical conductivity. Solid State Sci. 2006, 8, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gomez, J.; Ortega, E.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; García-Gabaldón, M. Electrochemical degradation of norfloxacin using BDD and new Sb-doped SnO2 ceramic anodes in an electrochemical reactor in the presence and absence of a cation-exchange membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 208, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gómez, J.; García-Gabaldón, M.; Carrillo-Abad, J.; Montañés, M.T.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V. Influence of the reactor configuration and the supporting electrolyte concentration on the electrochemical oxidation of Atenolol using BDD and SnO2 ceramic electrodes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Casas, M.P.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; Giner-Sanz, J.J.; Mestre, S.; García-Gabaldón, M. Statistical comparison of the photoelectrochemical degradation of an antibiotic pollutant using two Sb-doped SnO2 ceramic anodes coated with photoactive CdFe2O4 and ZnFe2O4 layers. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtfouse, E.; Schwarzbauer, J.; Robert, D. Environmental chemistry: green chemistry and pollutants in ecosystems; Springer, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Balseviciute; Martí-Calatayud, M.C.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; Mestre, S.; García-Gabaldón, M. Novel Sb-doped SnO2 ceramic anode coated with a photoactive BiPO4 layer for the photoelectrochemical degradation of an emerging pollutant. Chemosphere 2023, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo-Torner; García-Gabaldón, M.; Martí-Calatayud, M.C.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V. Norfloxacin mineralization under light exposure using Sb–SnO2 ceramic anodes coated with BiFeO3 photocatalyst. Chemosphere 2023, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balseviciute; Patiño-Cantero, I.; Carrillo-Abad, J.; Giner-Sanz, J.J.; García-Gabaldón, M.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; Martí-Calatayud, M.C. Degradation of multicomponent pharmaceutical mixtures by electrochemical oxidation: Insights about the process evolution at varying applied currents and concentrations of organics and supporting electrolyte. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, C.N.; Schöneich, S.; Synovec, R.E. Development of an enhanced total ion current chromatogram algorithm to improve untargeted peak detection. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 11365–11373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisquert, JJ.; Gonzales, C.; Guerrero, A. Transient On/Off Photocurrent Response of Halide Perovskite Photodetectors. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2023, 127, 21338–21350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, C.R.; Hwang, I.; Greenham, N.C. Photocurrent transients in all-polymer solar cells: Trapping and detrapping effects. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, F.; Koga, S. Influence of light intensity on the steady-state kinetics in tungsten trioxide particulate photoanode studied by intensity-modulated photocurrent spectroscopy. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.W.; Navarro, E.M.O.; Rodrigues, M.A.S.; Bernardes, A.M.; Pérez-Herranz, V. The role of the anode material and water matrix in the electrochemical oxidation of norfloxacin. Chemosphere 2018, 210, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouddouch; Akhsassi, B.; Amaterz, E.; Bakiz, B.; Taoufyq, A.; Villain, S.; Guinneton, F.; El Aamrani, A.; Gavarri, J.R.; Benlhachemi, A. Photodegradation under UV Light Irradiation of Various Types and Systems of Organic Pollutants in the Presence of a Performant BiPO4 Photocatalyst. Catalysts 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovácsa, K.; Tóth, T.; Wojnárovits, L. Evaluation of advanced oxidation processes for β-blockers degradation: a review. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 85, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Su, R.; Luo, S.; Spinney, R.; Cai, M.; Xiao, R.; Wei, Z. Comparison of the reactivity of ibuprofen with sulfate and hydroxyl radicals: An experimental and theoretical study. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 591, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarran, G.; Mendoza, E.; Schuler, R.H. Concerted effects of substituents in the reaction of •OH radicals with aromatics: The hydroxybenzaldehydes. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2016, 124, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Ben, W.; Xu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Qiang, Z. Ozonation of norfloxacin and levofloxacin in water: Specific reaction rate constants and defluorination reaction. Chemosphere 2018, 195, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, S.W.; Navarro, E.M.O.; Rodrigues, M.A.S.; Bernardes, A.M.; Pérez-Herranz, V. Using p-Si/BDD anode for the electrochemical oxidation of norfloxacin. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 832, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isarain-Chávez, E.; Rodríguez, R.M.; Cabot, P.L.; Centellas, F.; Arias, C.; Garrido, J.A.; Brillas, E. Degradation of pharmaceutical beta-blockers by electrochemical advanced oxidation processes using a flow plant with a solar compound parabolic collector. Water Res. 2011, 45, 4119–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, K.; Smets, B.F. Single-Step Nitrification Models Erroneously Describe Batch Ammonia Oxidation Profiles when Nitrite Oxidation Becomes Rate Limiting. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2000, 4, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gómez, J.; García-Gabaldón, M.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; García-García, D.M.; Carrillo-Abad, J. Synthesis of SnO-Sb2O5 ceramic anodes coated with cadmium and calcium ferrites for the depletion of emerging contaminants. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 67, 106136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopaj, F.; Oturan, N.; Pinson, J.; Podvorica, F.; Oturan, M.A. Effect of the anode materials on the efficiency of the electro-Fenton process for the mineralization of the antibiotic sulfamethazine. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 199, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Lv, Y.; Li, J.; Ding, J.; Xia, X.; Wei, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, Q. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic performance with metal-doped Bi2WO6 for typical fluoroquinolones degradation: Efficiencies, pathways and mechanisms. Chemosphere 2020, 252, 126577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadhi, T.A.; Mahar, R.B.; Bonelli, B. Chapter 12 - Actual mineralization versus partial degradation of wastewater contaminants, in: Nanomaterials for the Detection and Removal of Wastewater Pollutants; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Oturan, N.; Wu, J.; Oturan, M.A.; Zhang, H. The application of electro-Fenton process for the treatment of artificial sweeteners. In Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer Verlag, 2018; pp. 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponkshe, P. Thakur, Solar light–driven photocatalytic degradation and mineralization of beta blockers propranolol and atenolol by carbon dot/TiO2 composite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 15614–15630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olak-Kucharczyk, M.; Foszpańczyk, M.; Żyłła, R.; Ledakowicz, S. Photodegradation and ozonation of ibuprofen derivatives in the water environment: Kinetics approach and assessment of mineralization and biodegradability. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Calatayud, M.C.; Dionís, E.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V. Antimony-doped tin dioxide ceramics used as standalone membrane electrodes in electrofiltration reactors enhance the oxidation of organic micropollutants. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, S.; Farissi, S.; Rayaroth, M.P.; Kannan, M.; Nambi, I.M.; Liu, D. Electrochemical oxidation of Florfenicol in aqueous solution with mixed metal oxide electrode: Operational factors, reaction by-products and toxicity evaluation. Chemosphere 2024, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Trellu, C.; Skolotneva, E.; Oturan, N.; Oturan, M.A.; Mareev, S. Investigating the reactivity of TiOx and BDD anodes for electro-oxidation of organic pollutants by experimental and modeling approaches. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso; Sousa, C.Y.; Farinon, D.M.; Lopes, A.; Fernandes, A. Electrochemical Oxidation of Pollutants in Textile Wastewaters Using BDD and Ti-Based Anode Materials. Textiles 2024, 4, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Scott, Process intensification: An electrochemical perspective. Renew. ad Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1406–1426. [CrossRef]

- Trench, A.B.; Oturan, N.; Demir, A.; Moura, J.P.C.; Trellu, C.; Santos, M.C.; Oturan, M.A. Degradation of methylparaben by anodic oxidation, electro-Fenton, and photoelectro-Fenton using carbon felt-BDD cell. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).