Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

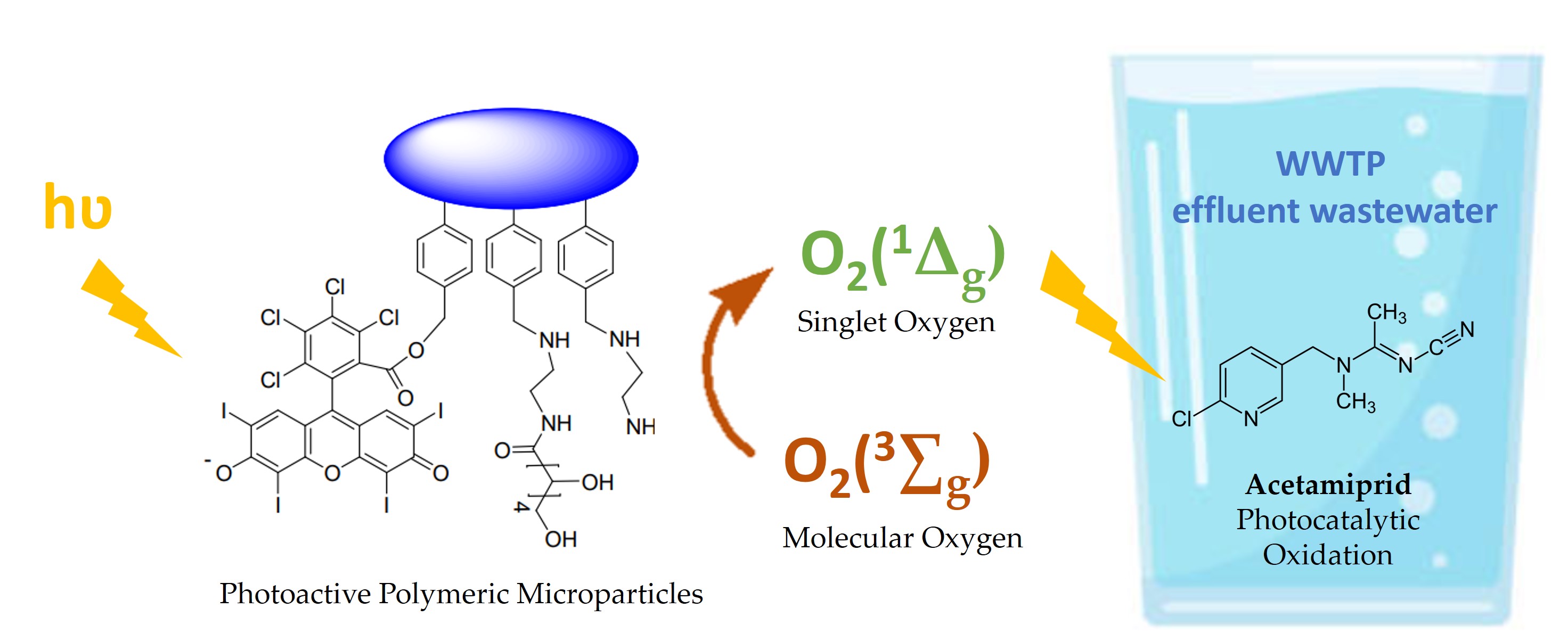

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

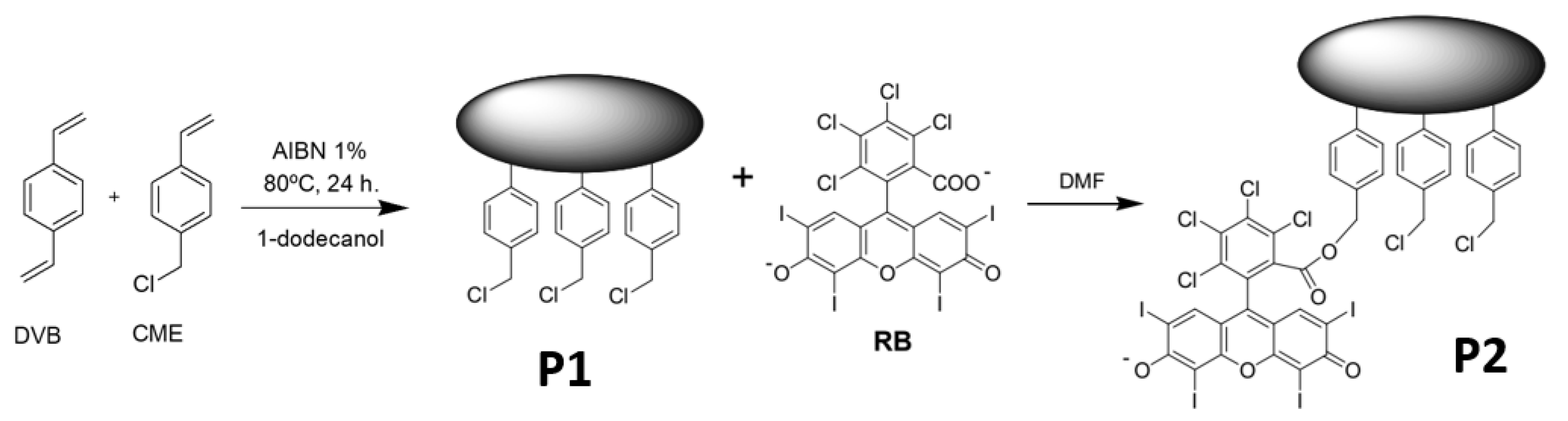

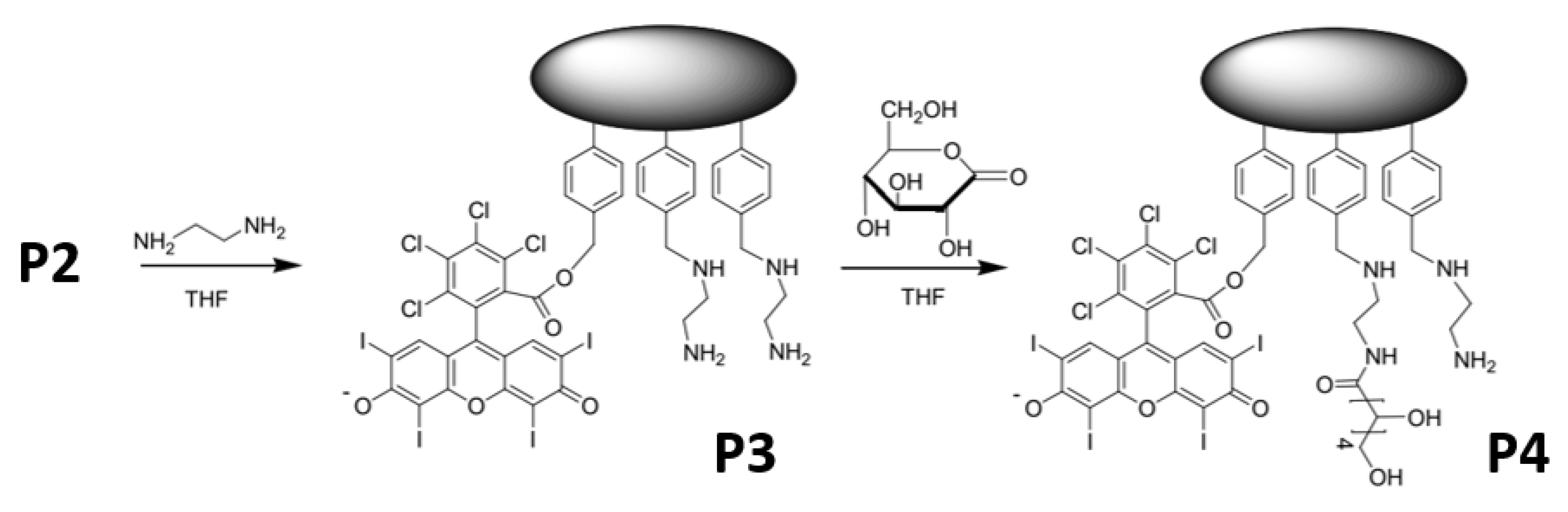

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of the Photoactive Microparticles

2.2. Kinetics of Acetamiprid Photo-Oxidation Using the Photoactive Microparticles

2.3. Studies of Acetamiprid Degradation with P3 and P4 Polymers as Photosensitizers in Industrial WWTP Samples

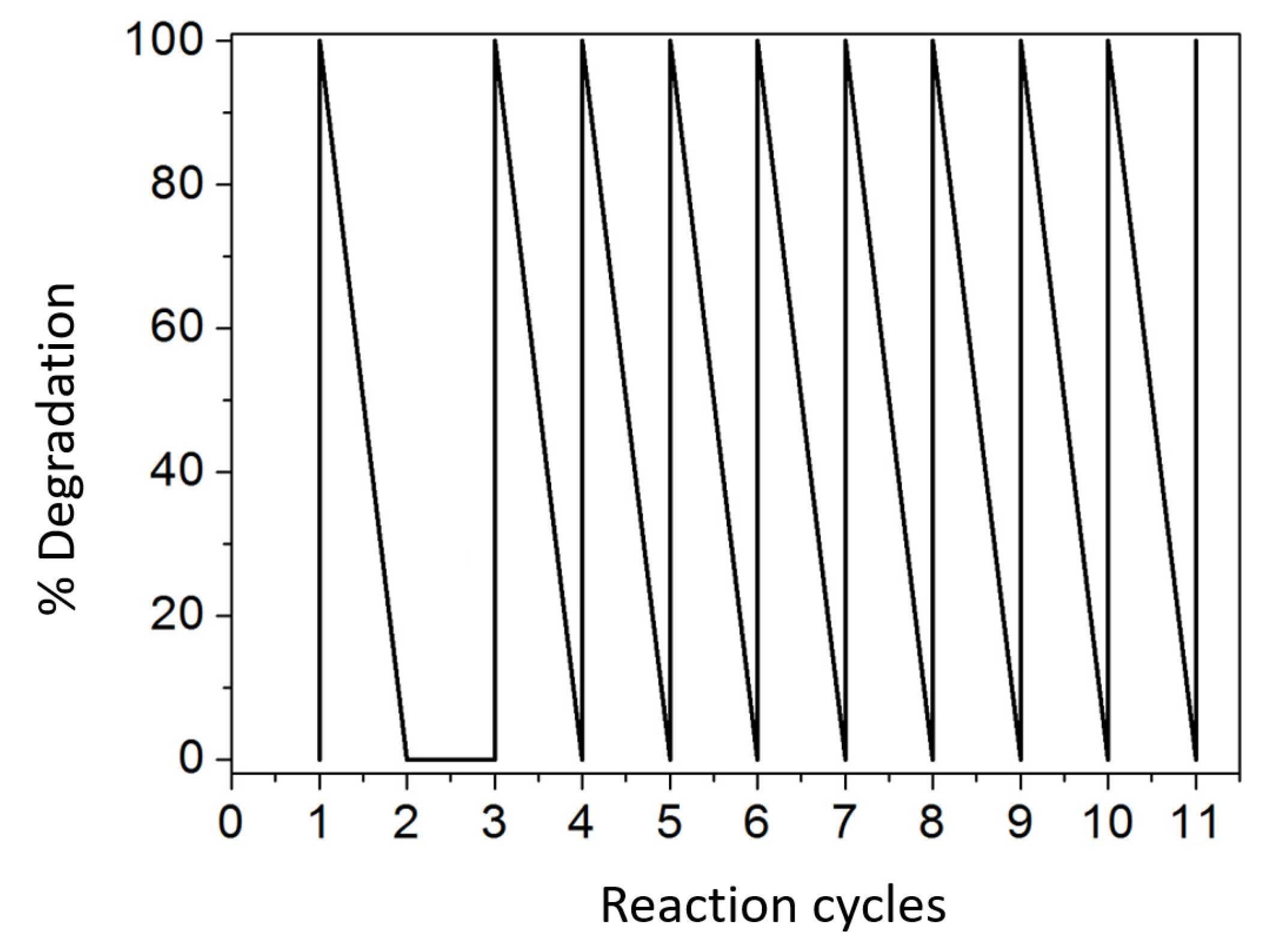

2.4. Reciclability Studies with P3 and P4 Polymers in Acetamiprid Degradation

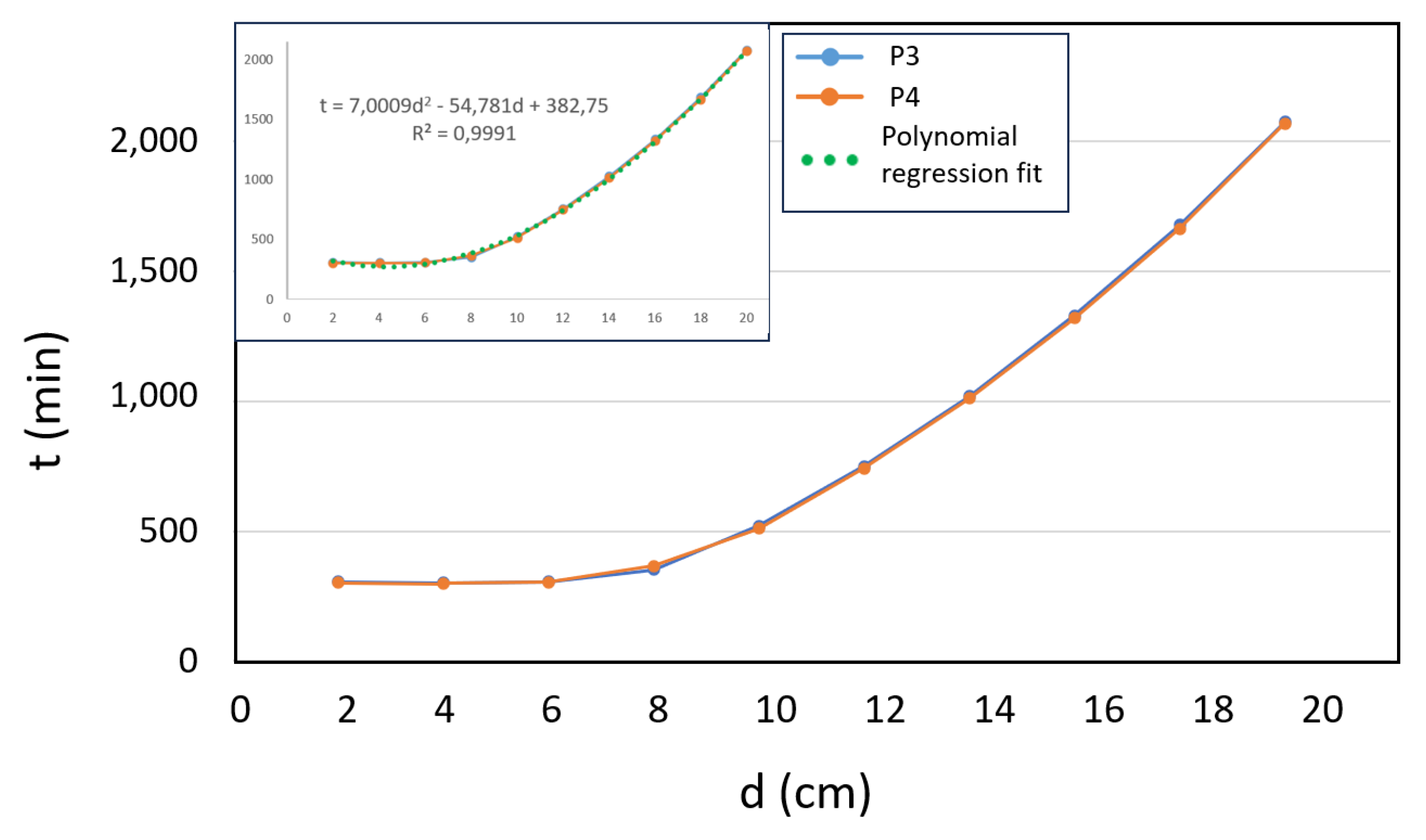

2.5. Simulated and Direct Solar Irradiance Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

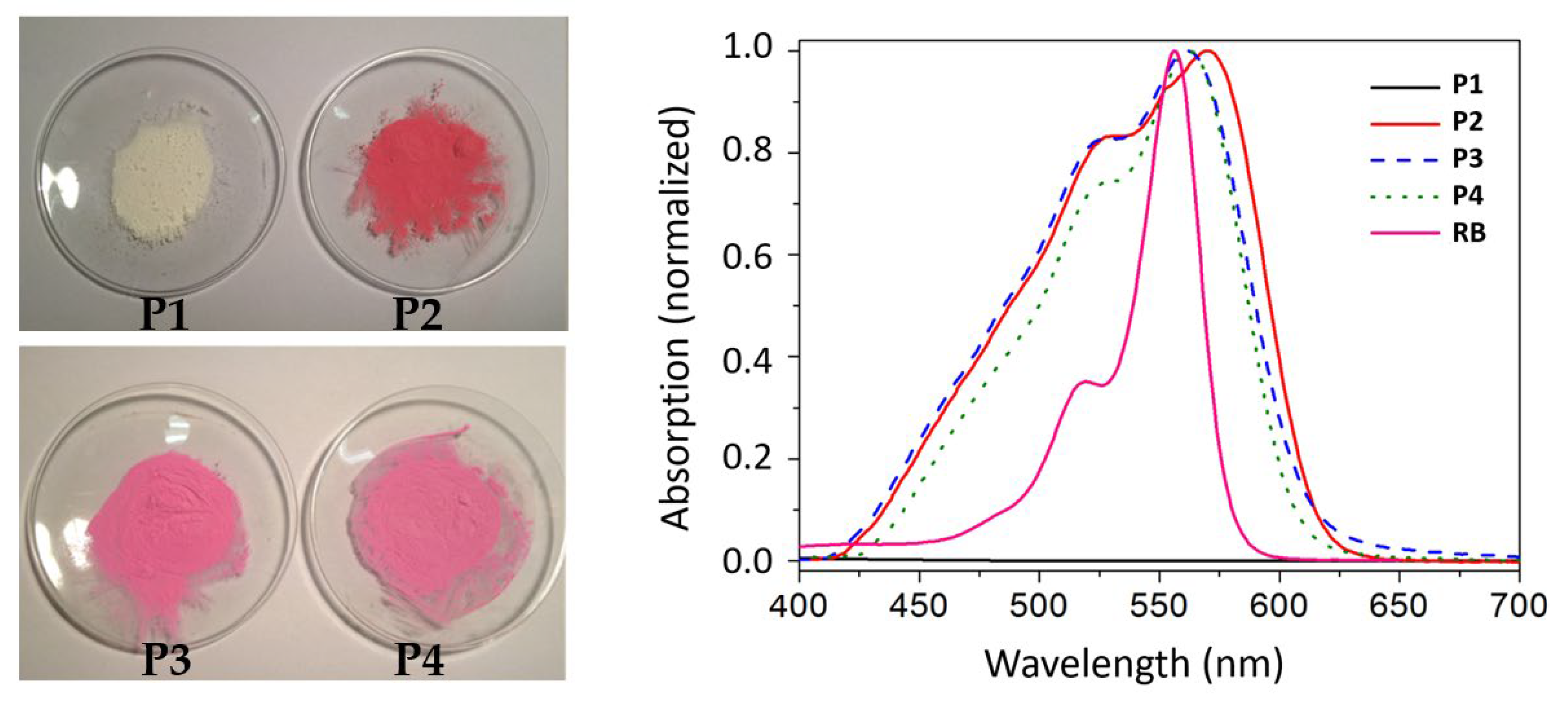

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of the Photoactive Microparticles

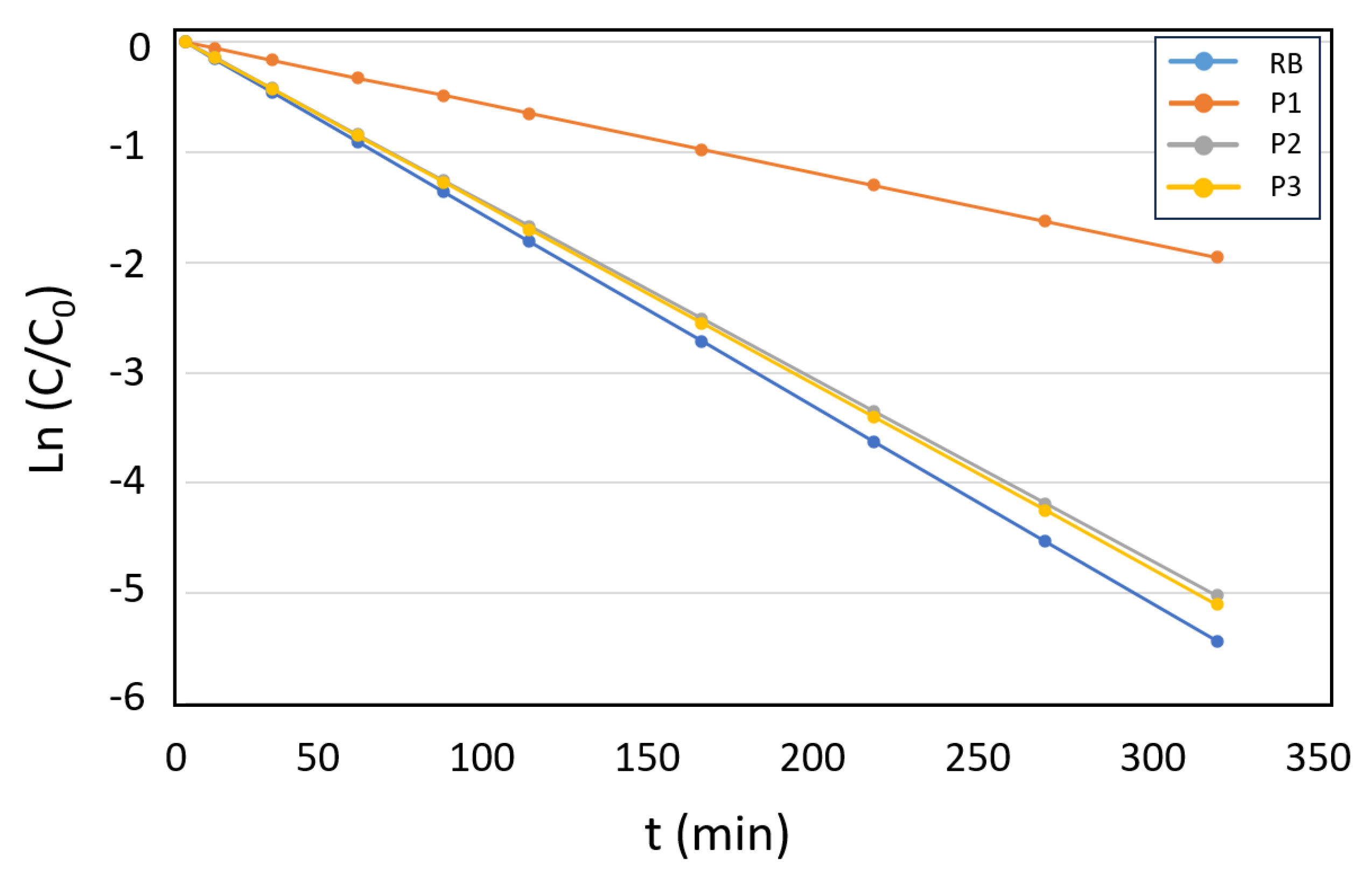

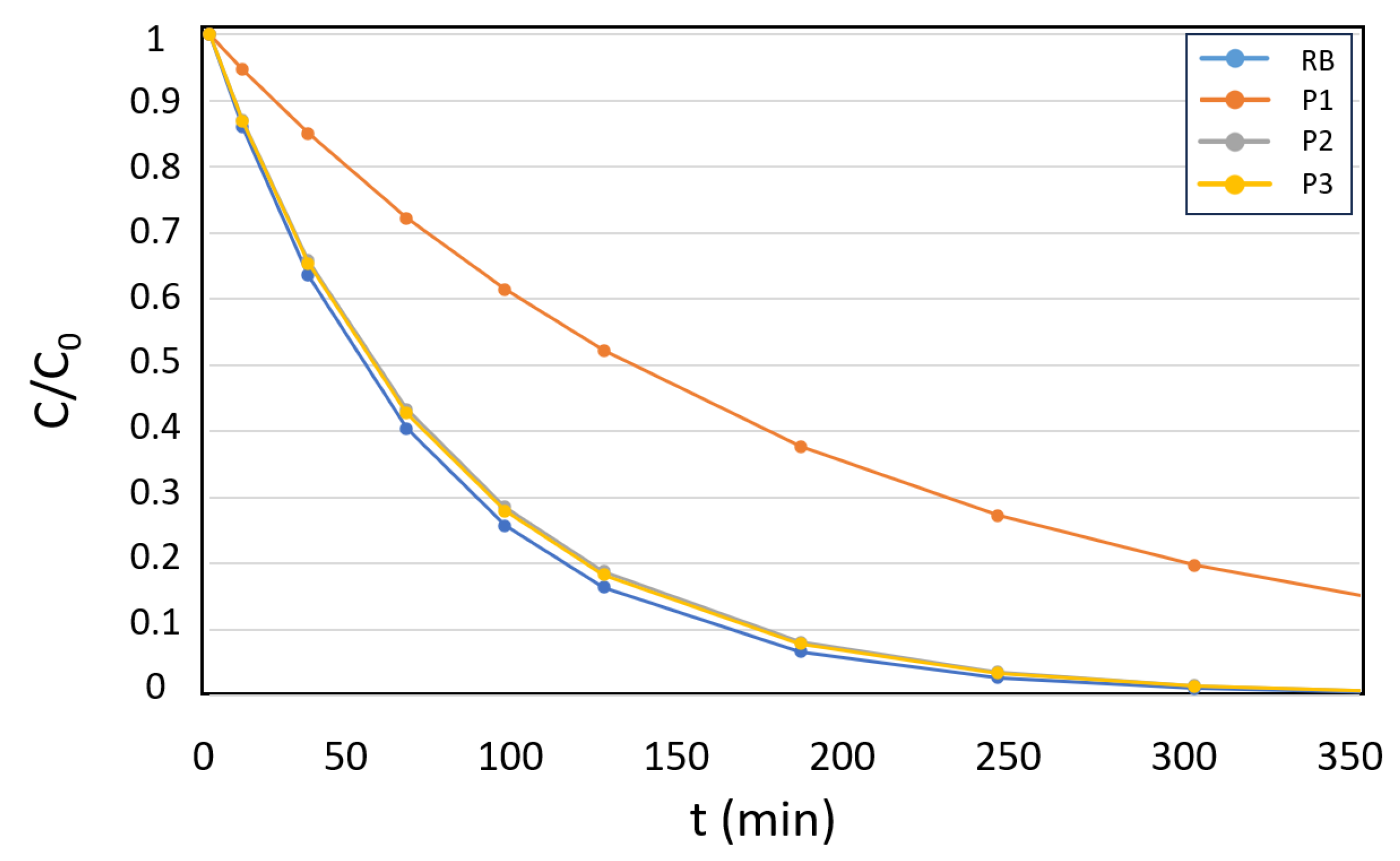

3.2. Study of the Kinetics of Acetamiprid Photo-Oxidation Using the Photoactive Microparticles

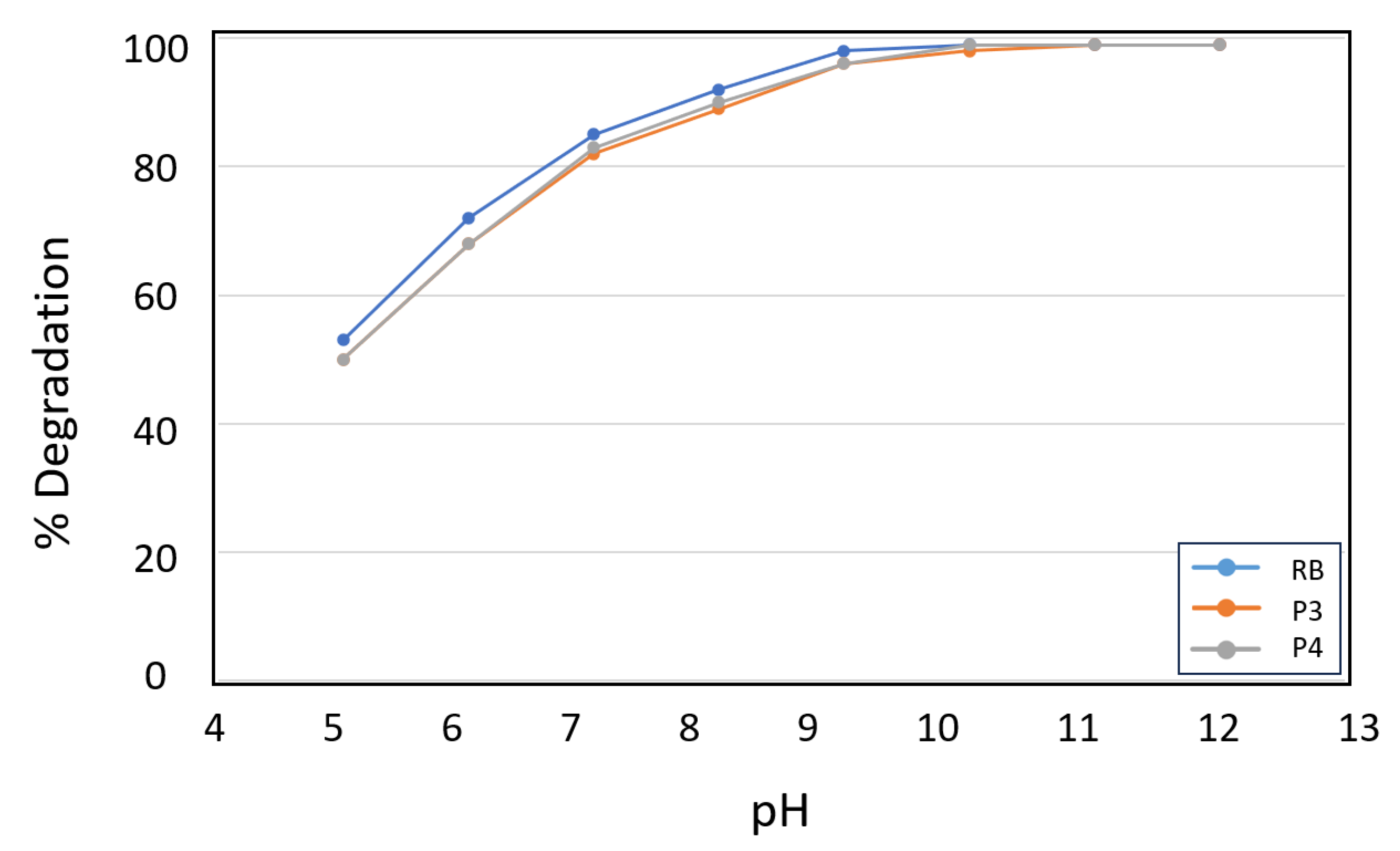

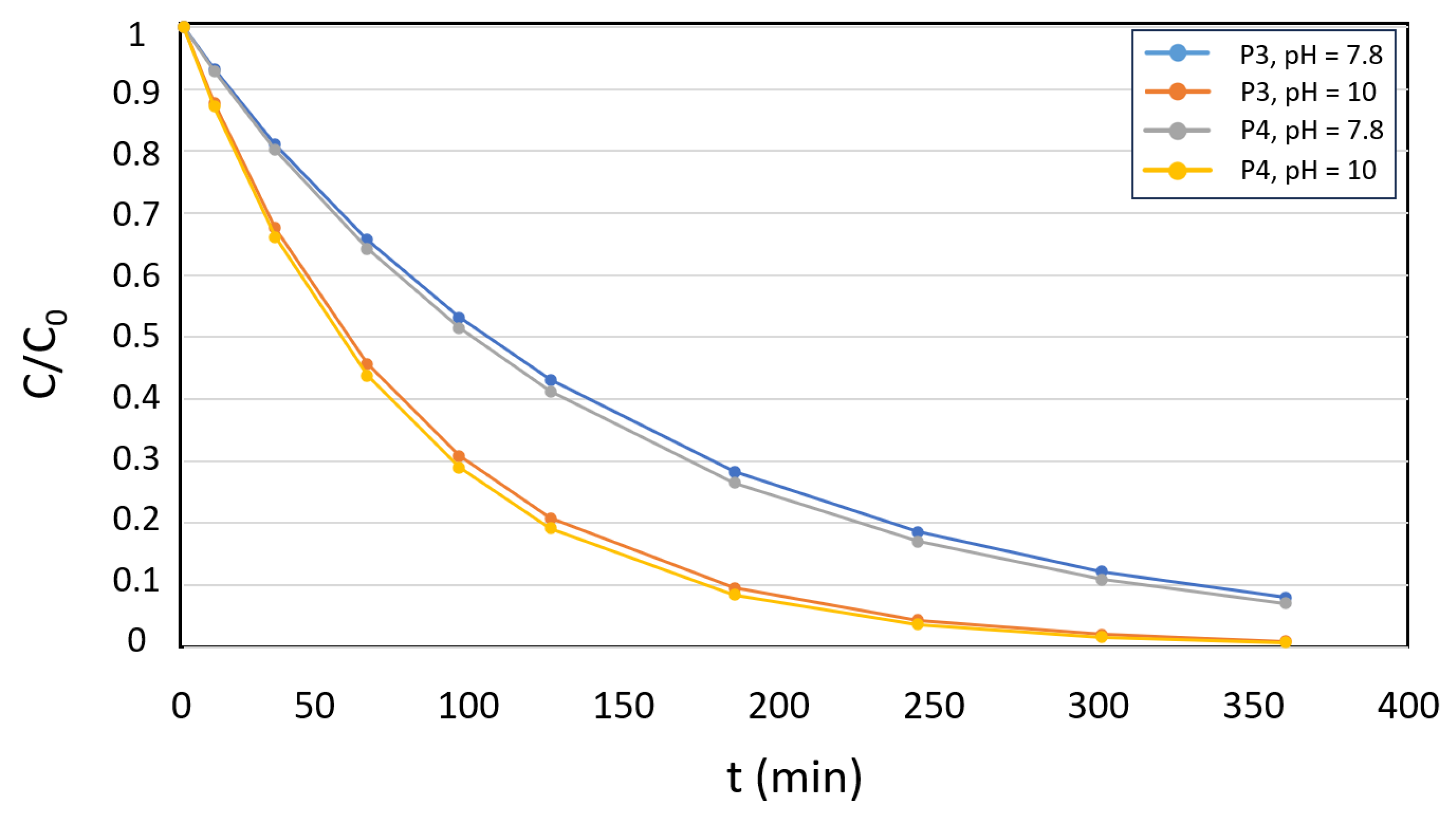

3.3. Acetamiprid Degradation Studies with P3 - P4 Microparticles as Photosensitizers in Industrial WWTP Samples

3.4. Reciclability Studies with P3 and P4 Polymers in Acetamiprid Degradation

3.5. Experimental Study with Simulated and Direct Solar Irradiance on IWWTP Samples

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alrousan, D.M.; Dunlop, P.S.; McMurray, T.A.; Byrne, J.A. Photocatalytic inactivation of E. coli in surface water using immobilised nanoparticle TiO2 films. Water Research 2009, 43, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, J.S.; Messaddeq, Y. The Role of Solar Concentrators in Photocatalytic Wastewater Treatment. Energies 2024, 17, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villén, L.; Manjón, F.; García-Fresnadillo, D.; Orellana, G. Solar water disinfection by photocatalytic singlet oxygen production in heterogeneous medium. Applied Catalysis B Environmental 2006, 69, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.E.; Sierra, M.; Cuevas, E.; García, R.D.; Esparza, P. Photocatalysis with solar energy: Sunlight-responsive photocatalyst based on TiO2 loaded on a natural material for wastewater treatment. Solar Energy 2016, 135, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Li, Q.; Wei, T.; Zhang, G.; Ren, Z. Historical development and prospects of photocatalysts for pollutant removal in water. Journal of hazardous materials 2020, 395, 122599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, A.; Kumar, P.S.; Vo DV, N.; Yaashikaa, P.R.; Karishma, S.; Jeevanantham, S.; Bharathi, V.D. Photocatalysis for removal of environmental pollutants and fuel production: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2021, 19, 441–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee BC, Y.; Lim, F.Y.; Loh, W.H.; Ong, S.L.; Hu, J. Emerging contaminants: An overview of recent trends for their treatment and management using light-driven processes. Water 2021, 13, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin-Crini, N.; Lichtfouse, E.; Liu, G.; Balaram, V.; Ribeiro, A.R.L.; Lu, Z.; Crini, G. Worldwide cases of water pollution by emerging contaminants: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2311–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arman, N.Z.; Salmiati, S.; Aris, A.; Salim, M.R.; Nazifa, T.H.; Muhamad, M.S.; Marpongahtun, M. A review on emerging pollutants in the water environment: Existences, health effects and treatment processes. Water 2021, 13, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.A.V.E.E.N.; Khan, M.D.; Shahane, S.; Rai, D.; Chauhan, D.; Kant, C.; Chaudhary, V.K. Emerging pollutants in aquatic environment: Source, effect, and challenges in biomonitoring and bioremediation-a review. Pollution 2020, 6, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.K.; Kashif, A.; Fuwad, A.; Choi, Y. Current advances in treatment technologies for removal of emerging contaminants from water–A critical review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 442, 213993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosato, R.; Bolognino, I.; Fontana, F.; Sora, I.N. Applications of Heterogeneous Photocatalysis to the Degradation of Oxytetracycline in Water: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madureira, J.; Melo, R.; Margaça, F.M.; Verde, S.C. Ionizing radiation for treatment of pharmaceutical compounds: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 49, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilachi, I.C.; Asiminicesei, D.M.; Fertu, D.I.; Gavrilescu, M. Occurrence and fate of emerging pollutants in water environment and options for their removal. Water 2021, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.K.; Kashif, A.; Fuwad, A.; Choi, Y. Current advances in treatment technologies for removal of emerging contaminants from water–A critical review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 442, 213993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, B.S.; Kumar, P.S.; Show, P.L. A review on effective removal of emerging contaminants from aquatic systems: Current trends and scope for further research. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 409, 124413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.C. Removal of emerging contaminants from the environment by adsorption. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 150, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, M.L.; Santos-Juanes, L.; Arques, A.; Amat, A.M.; Miranda, M.A. Organic photocatalysts for the oxidation of pollutants and model compounds. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1710–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, D.; Dasgupta, S. Visible light induced photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2005, 6, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracamontes-Ruelas, A.R.; Reyes-Vidal, Y.; Irigoyen-Campuzano, J.R.; Reynoso-Cuevas, L. Simultaneous Oxidation of Emerging Pollutants in Real Wastewater by the Advanced Fenton Oxidation Process. Catalysts 2023, 13, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiano, V.; De Marco, I. Removal of Azo Dyes from Wastewater through Heterogeneous Photocatalysis and Supercritical Water Oxidation. Separations 2023, 10, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Khan, S.; Han, C. UV/TiO2 Photocatalysis as an Efficient Livestock Wastewater Quaternary Treatment for Antibiotics Removal. Water 2022, 14, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodha, V.; Shahabuddin, S.; Gaur, R.; Ahmad, I.; Bandyopadhyay, R.; Sridewi, N. Comprehensive Review on Zeolite-Based Nanocomposites for Treatment of Effluents from Wastewater. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motamedi, M.; Yerushalmi, L.; Haghighat, F.; Chen, Z. Recent developments in photocatalysis of industrial effluents։ A review and example of phenolic compounds degradation. Chemosphere 2022, 296, 133688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, J.; Margaça, F.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C.; Verde, S.C.; Barros, L. Applications of bioactive compounds extracted from olive industry wastes: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madureira, J.; Barros, L.; Cabo Verde, S.; Margaça, F.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C. Ionizing radiation technologies to increase the extraction of bioactive compounds from agro-industrial residues: A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 11054–11067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Mañas, M.C.; Plaza-Bolaños, P.; Martínez-Piernas, A.B.; Sánchez-Pérez, J.A.; Agüera, A. Determination of pesticide levels in wastewater from an agro-food industry: Target, suspect and transformation product analysis. Chemosphere 2019, 232, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-López, J.; Llorent-Martínez, E.J.; Ortega-Barrales, P.; Ruiz-Medina, A. Analysis of neonicotinoid pesticides in the agri-food sector: a critical assessment of the state of the art. Applied Spectroscopy Reviews 2020, 55, 613–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Life Clean Up. Available online: https://www.lifecleanup.eu/ (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Fabregat, V.; Pagán, J.M. Technical–Economic Feasibility of a New Method of Adsorbent Materials and Advanced Oxidation Techniques to Remove Emerging Pollutants in Treated Wastewater. Water 2024, 16, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabregat, V. Enhancing Emerging Pollutant Removal in Industrial Wastewater: Validation of a Photocatalysis Technology in Agri-Food Industry Effluents. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, B.; Werner, M.; Berndt, C.; Shattuck, A.; Galt, R.; Williams, B.; Tittor, A. A new critical social science research agenda on pesticides. Agriculture and Human Values 2024, 41, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, J. Acetamiprid in the environment: the impact of commercial neonicotinoid formulations on soil function and ecology. Bangor University (United Kingdom), 2022.

- Wallace, D.R. Acetamiprid. Encyclopedia of Toxicology, Fourth Edition: Volume 1-9, 2023 (pp. V1–53). Elsevier.

- Yamada, T.; Takahashi, H.; Hatano, R. A novel insecticide, acetamiprid. In Nicotinoid insecticides and the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, 1999, (pp. 149–176). Tokyo: Springer Japan.

- Zuščíková, L., Bažány, D., Greifová, H., Knížatová, N., Kováčik, A., Lukáč, N., Jambor, T. Screening of toxic effects of neonicotinoid insecticides with a focus on acetamiprid: A review. Toxics 2023, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phogat, A.; Singh, J.; Kumar, V.; Malik, V. Toxicity of the acetamiprid insecticide for mammals: A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU pesticides export ban: what could be the consequences? PAN EUROPE, Brussels, 2024.

- Yao, B.; Zhou, Y. Removal of neonicotinoid insecticides from water in various treatment processes: A review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2024, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzsvány, V., Rajić, L., Jović, B., Orčić, D., Csanádi, J., Lazić, S., Abramović, B. Spectroscopic monitoring of photocatalytic degradation of the insecticide acetamiprid and its degradation product 6-chloronicotinic acid on TiO2 catalyst. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part A 2012, 47, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelić, I.E., Povijač, K., Gilja, V., Tomašić, V., Gomzi, Z. Photocatalytic degradation of acetamiprid in a rotating photoreactor-Determination of reactive species. Catalysis Communications 2022, 169, 106474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Kang, J.K.; Park, S.J.; Lee, C.G.; Moon, J.K.; Alvarez, P.J. Photocatalytic degradation of neonicotinoid insecticides using sulfate-doped Ag3PO4 with enhanced visible light activity. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 402, 126183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E. Fenton, photo-Fenton, electro-Fenton, and their combined treatments for the removal of insecticides from waters and soils. A review. Separation and Purification Technology 2022, 284, 120290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wu, H.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y. Superior photo-Fenton degradation of acetamiprid by α-Fe2O3-pillared bentonite/L-cysteine complex: Synergy of L-cysteine and visible light. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 344, 118523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zhong, Z., Muhammad, Y., He, H., Zhao, Z., Nie, S., Zhao, Z. Defect engineering of NH2-MIL-88B (Fe) using different monodentate ligands for enhancement of photo-Fenton catalytic performance of acetamiprid degradation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020, 398, 125684. [CrossRef]

- Fasnabi, P.A.; Madhu, G.; Soloman, P.A. Removal of acetamiprid from wastewater by fenton and photo-fenton processes–optimization by response surface methodology and kinetics. CLEAN–Soil Air Water 2016, 44, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.B.; Raut-Jadhav, S.; Topare, N.S.; Pandit, A.B. Combined strategy of hydrodynamic cavitation and Fenton chemistry for the intensified degradation of acetamiprid. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 325, 124701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Alcalde, A.; Sans, C.; Esplugas, S. Priority pesticides abatement by advanced water technologies: The case of acetamiprid removal by ozonation. Science of the Total Environment 2017, 599, 1454–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Arciprete, M.L.; Santos-Juanes, L.; Arques, A.; Vercher, R.F.; Amat, A.M.; Furlong, J.P.; Gonzalez, M.C. Reactivity of neonicotinoid pesticides with singlet oxygen. Catalysis Today 2010, 151, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, R.W.; Gamlin, J.N. A compilation of singlet oxygen yields from biologically relevant molecules. Photochem. Photobiol. 1999, 70, 391–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, C.R.; Kochevar, I.E. Does rose bengal triplet generate superoxide anion? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 3297–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neckers, D.C. Rose Bengal. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 1989, 47, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez-Moraleja, A.; Cabezuelo, O.; Martinez-Haya, R.; Schmidt, L.C.; Bosca, F.; Marin, M.L. Organic photoredox catalysts: Tuning the operating mechanisms in the degradation of pollutants. Pure Appl. Chem. 2023, 95, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez-Moraleja, A.; Moya, P.; Marin, M.L.; Bosca, F. Synthesis of novel heterogeneous photocatalysts based on Rose Bengal for effective wastewater disinfection and decontamination. Catal. Today 2023, 413, 113948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.; Moya, P.; Bosca, F.; Marin, M.L. Photoreactivity of new rose bengal-SiO2 heterogeneous photocatalysts with and without a magnetite core for drug degradation and disinfection. Catal. Today 2023, 413, 113994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez-Moraleja, A.; Bosio, A.; Gamba, S.; Bosca, F.; Marin, M.L. Covalent or ionic bonding of Eosin Y to silica: New visible-light photocatalysts for redox wastewater remediation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Liu, Y., Zhu, Z., Zhang, G., Zou, T., Zou, Z., Xie, C. A full-sunlight-driven photocatalyst with super long-persistent energy storage ability. Scientific Reports 2013, 3, 2409. [Google Scholar]

- Fabregat, V.; Burguete, M.I.; Galindo, F. Singlet oxygen generation by photoactive polymeric microparticles with enhanced aqueous compatibility. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 11884–11892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabregat, V.; Burguete, M.I.; Luis, S.V.; Galindo, F. Improving photocatalytic oxygenation mediated by polymer supported photosensitizers using semiconductor quantum dots as ‘light antennas’. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 35154–35158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagaki, S.; Liesner, C.E.; Neckers, D.C. Polymer-based sensitizers for photochemical reactions. Silica gel as a support. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 1573–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.C.; Svec, F.; Frechet, J.M. Hydrophilization of porous polystyrene-based continuous rod column. Anal. Chem. 1995, 67, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paczkowska, B.; Paczkowski, J.; Neckers, D.C. Heterogeneous and semiheterogeneous photosensitization: Photochemical processes using derivatives of rose bengal. Macromolecules 1986, 19, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.H.; Martin, R.L.; Feriozi, D.; Brewer, D.; Kayser, R. On the mechanism of quenching of singlet oxygen by amines-iii. evidence for a charge-transfer-like complex. Photochemistry and Photobiology 1973, 17, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmanyan, A.P.; Jenks, W.S.; Jardon, P. Charge-transfer quenching of singlet oxygen O2 (1Δg) by amines and aromatic hydrocarbons. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 1998, 102, 7420–7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.H.; Brewer, D.; in:, B. Ranby, J.F. Rabek (Eds.), Singlet Oxygen Reactions with Organic Compounds and Polymers 1976, 36–43.

- Sirtori, C.; Agüera, A.; Carra, I.; Sanchéz Pérez, J.A. Application of liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry to the identification of acetamiprid transformation products generated under oxidative processes in different water matrices. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2014, 406, 2549–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, M.I.; Salgado, R.; Laia CA, T.; Cooper, W.J.; Sontag, G.; Burrows, H.D.; Noronha, J.P. The effect of chloride ions and organic matter on the photodegradation of acetamiprid in saline waters. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2018, 360, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas Ibáñez, G.; Casas López, J.L.; Esteban García, B.; Sánchez Pérez, J.A. Controlling pH in biological depuration of industrial wastewater to enable micropollutant removal using a further advanced oxidation process. Journal of Chemical Technology Biotechnology 2014, 89, 1274–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbiljić, J., Guzsvány, V., Vajdle, O., Prlina, B., Agbaba, J., Dalmacija, B., Kalcher, K. Determination of H2O2 by MnO2 modified screen printed carbon electrode during Fenton and visible light-assisted photo-Fenton based removal of acetamiprid from water. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2015, 755, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabasum, A.; Bhatti, I.A.; Nadeem, N.; Zahid, M.; Rehan, Z.A.; Hussain, T.; Jilani, A. Degradation of acetamiprid using graphene-oxide-based metal (Mn and Ni) ferrites as Fenton-like photocatalysts. Water Science and Technology 2020, 81, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.aemet.es/es/serviciosclimaticos/datosclimatologicos/atlas_radiacion_solar (accessed on 19 November 2024). (accessed on 19 November 2024).

| Photosensitizer | % Degradation | Kobs (min-1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RB | Conversion (%) | >99 | 0.0151 |

| t (min) | 305 | ||

| P2 | Conversion (%) | 85 | 0.0054 |

| t (min) | 350 | ||

| P3 | Conversion (%) | >99 | 0.0147 |

| t (min) | 330 | ||

| P4 | Conversion (%) | >99 | 0.0148 |

| t (min) | 325 | ||

| pH | Photosensitizer | % Degradation | Kobs (min-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | RB | >99 | 0.0159 |

| P3 | >99 | 0.0159 | |

| P4 | >99 | 0.0159 | |

| 11 | RB | >99 | 0.0158 |

| P3 | >99 | 0.0157 | |

| P4 | >99 | 0.0158 | |

| 10 | RB | >99 | 0.0154 |

| P3 | 98 | 0.0147 | |

| P4 | >99 | 0.0148 | |

| 9 | RB | 98 | 0.0130 |

| P3 | 96 | 0.0107 | |

| P4 | 96 | 0.0107 | |

| 8 | RB | 92 | 0.0084 |

| P3 | 90 | 0.0075 | |

| P4 | 90 | 0.0076 | |

| 7 | RB | 85 | 0.0063 |

| P3 | 82 | 0.0057 | |

| P4 | 83 | 0.0059 | |

| 6 | RB | 72 | 0.0042 |

| P3 | 68 | 0.0038 | |

| P4 | 68 | 0.0038 | |

| 5 | RB | 53 | 0.0025 |

| P3 | 50 | 0.0023 | |

| P4 | 50 | 0.0023 |

| P3 | P4 | Control | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | pH | [Acmp] ppm |

% Deg (360 min) |

kobs (min−1) |

% Deg (360 min) |

kobs (min−1) |

% Deg (RB, 360 min) |

% Deg (P1, 360 min) |

| 1 | 7.8 | 0.045 | 92 | 0.0070 | 93 | 0.0074 | 93 | 0 |

| 10 | >99 | 0.0131 | >99 | 0.0138 | >99 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 7.7 | 0.053 | 91 | 0.0069 | 92 | 0.0072 | 93 | 0 |

| 10 | >99 | 0.0129 | >99 | 0.0132 | >99 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 7.8 | 0.068 | 90 | 0.0064 | 93 | 0.0075 | 94 | 0 |

| 10 | >99 | 0.0125 | >99 | 0.0139 | >99 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 7.6 | 0.079 | 93 | 0.0073 | 94 | 0.0077 | 94 | 0 |

| 10 | >99 | 0.0139 | >99 | 0.0145 | >99 | 0 | ||

| 5 | 7.8 | 0.092 | 92 | 0.0071 | 94 | 0.0079 | 95 | 0 |

| 10 | >99 | 0.0135 | >99 | 0.0147 | >99 | 0 | ||

| Method | Characteristics | % Degradation | t (min) | pH | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | Heterogeneous | >99 | 1600 | 3 | 41, 43 |

| Fenton | Homogeneous | >99 | 40 | 3 | 43, 66 |

| Fenton | Homogeneous, wastewater | >99 | 90 | 3 | 43, 66 |

| Photo-Fenton | Homogeneous | >99 | 10 | 2.8 | 43, 69 |

| Photo-Fenton | Heterogeneous | >99 | 60 | 3 | 43, 45 |

| Photo-Fenton | Heterogeneous | 78 | 240 | 9 | 43, 45 |

| Fenton | Homogeneous, wastewater | >99 | 60 | 3 | 46 |

| Photo-Fenton | Homogeneous, wastewater | >99 | 30 | 3 | 46 |

| Fenton | Heterogeneous | >99 | 60 | 3 | 70 |

| Fenton | Heterogeneous | 30 | 60 | 8 | 70 |

| Singlet Oxygen | Heterogeneous, wastewater | 94 | 360 | 7.5 – 8 | This study |

| Singlet Oxygen | Heterogeneous, wastewater | >99 | 300 | 10 |

| Date | Solar irradiation | Photosensitizer | Time to >99% Degradation | Kobs (min-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 27th | 7,72 kWh/m2 | P3 | 585 min | 0.007872 |

| P4 | 582 min | 0.007913 | ||

| July 18th | 7,33 kWh/m2 | P3 | 614 min | 0.007494 |

| P4 | 613 min | 0.007513 | ||

| August 8th | 7,16 kWh/m2 | P3 | 627 min | 0.007340 |

| P4 | 625 min | 0.007368 | ||

| September 12th | 6,49 kWh/m2 | P3 | 678 min | 0.006790 |

| P4 | 677 min | 0.006802 | ||

| October 17th | 5,21 kWh/m2 | P3 | 775 min | 0.005941 |

| P4 | 775 min | 0.005941 | ||

| November 14th | 3,35 kWh/m2 | P3 | 916 min | 0.005027 |

| P4 | 915 min | 0.005033 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).