1. Introduction

Brazil is a continental-sized country encompassing multiple climatic zones, which promote high ecological diversity and give rise to distinct biomes. Among these ecosystems, the Caatinga stands out as the only biome exclusively found in Brazil, characterized by unique vegetation and a remarkable degree of endemism [

1]. Located mainly in the Northeast region of Brazil, where it occupies approximately 70% of the territory, the Caatinga is characterized by a tropical semi-arid climate, with high temperatures, low annual rainfall, and prolonged dry periods [

2].

Among the native plants of the Caatinga, the genus

Lippia comprises approximately 200 aromatic species belonging to the family Verbenaceae, with notable ethnobotanical and economic importance, especially due to their medicinal properties [

3].

Lippia grata Schauer, popularly known as “alecrim-do-mato” or “alecrim-de-tabuleiro”, is a species native to the Caatinga that has been traditionally used in folk medicine for the treatment of flu and colds, as well as for washing wounds and bruises, due to its antimicrobial and antiseptic properties [

4].

The leaves of

L. grata are characterized by a strong aroma, resulting from the secretion of essential oil (EO) by glandular trichomes [

5]. Several medicinal properties have been attributed to the EO of

L. grata, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antitumor activities, mainly associated with its major compounds, carvacrol and thymol [

6]. More recently, studies have demonstrated the insecticidal potential of

L. grata EO against

Aedes aegypti, the vector of arbovirus-related diseases, including dengue, yellow fever, Zika, and chikungunya [

1,

7].

The yield and chemical composition of plant EOs are known to vary both qualitatively and quantitatively in response to several biotic and abiotic factors, including edaphoclimatic conditions, altitude, soil type, agricultural practices, plant developmental stage, phenological phase, and harvest time [

8,

9,

10]. In aromatic plants, these factors can significantly influence the biosynthesis and accumulation of volatile compounds, thereby affecting EO quality and biological activity.

Seasonal variation has been identified as a key factor influencing EO production in several

Lippia species. For example, in

L. origanoides, higher EO yields were observed during the rainy season, although the chemical profile remained relatively stable [

11]. In contrast, studies on

L. alba demonstrated that both EO composition and antioxidant activity varied throughout the year, depending on seasonal climatic conditions [

12]. Beyond seasonal effects, the timing of harvest within a single day has also been shown to influence EO composition in aromatic species such as

Mentha spicata, even when total oil yield remains unchanged [

13]. Similar patterns have been reported for

Salvia officinalis,

S. rosmarinus, and other medicinal and aromatic plants, where phenological stage and harvest time play a decisive role in determining both yield and volatile compound profiles.

Despite these advances, scientific studies addressing the combined effects of seasonal variation and diurnal harvest time on EO yield and chemical composition in Lippia species remain scarce, particularly for L. grata. This lack of information limits the development of evidence-based agronomic and harvesting strategies aimed at optimizing EO quality for phytotherapeutic, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical applications.

In this context, the present study aimed to evaluate the influence of seasonal variation and harvest time on the yield and chemical composition of L. grata essential oil. By integrating detailed experimental conditions with comprehensive chemical analysis, this work seeks to contribute to a better understanding of how environmental and temporal factors affect EO production in this Caatinga-endemic species, thereby supporting its sustainable use and industrial valorization.

2. Results

The analysis of variance (

Table 1) revealed that season significantly affected leaf fresh mass (

p < 0.001), dry mass (

p < 0.05), EO yield (

p < 0.01), and the contents of carvacrol (

p < 0.01) and thymol (

p < 0.05). Harvest time had a significant effect on fresh mass (

p < 0.05) and carvacrol content (

p < 0.05). The interaction between season and harvest time significantly influenced only

p-cymene content (

p < 0.05). Shoot length was not significantly affected by either season or harvest time (

p > 0.05), with mean values ranging from 1.06 to 1.24 m.

The highest leaf fresh mass was observed in summer (255.0 g), which was statistically higher than both winter (173.8 g) and spring (151.2 g). In contrast, dry mass was higher in the winter (126.6 g) (

Figure 1A). EO yield was higher in spring (4.92%) than in winter (4.09%) and summer (3.90%) (

Figure 1B).

Carvacrol was the major aromatic compound in all seasons, with the highest content recorded in summer (59.28%). A highest thymol content was also observed in summer (6.99%).

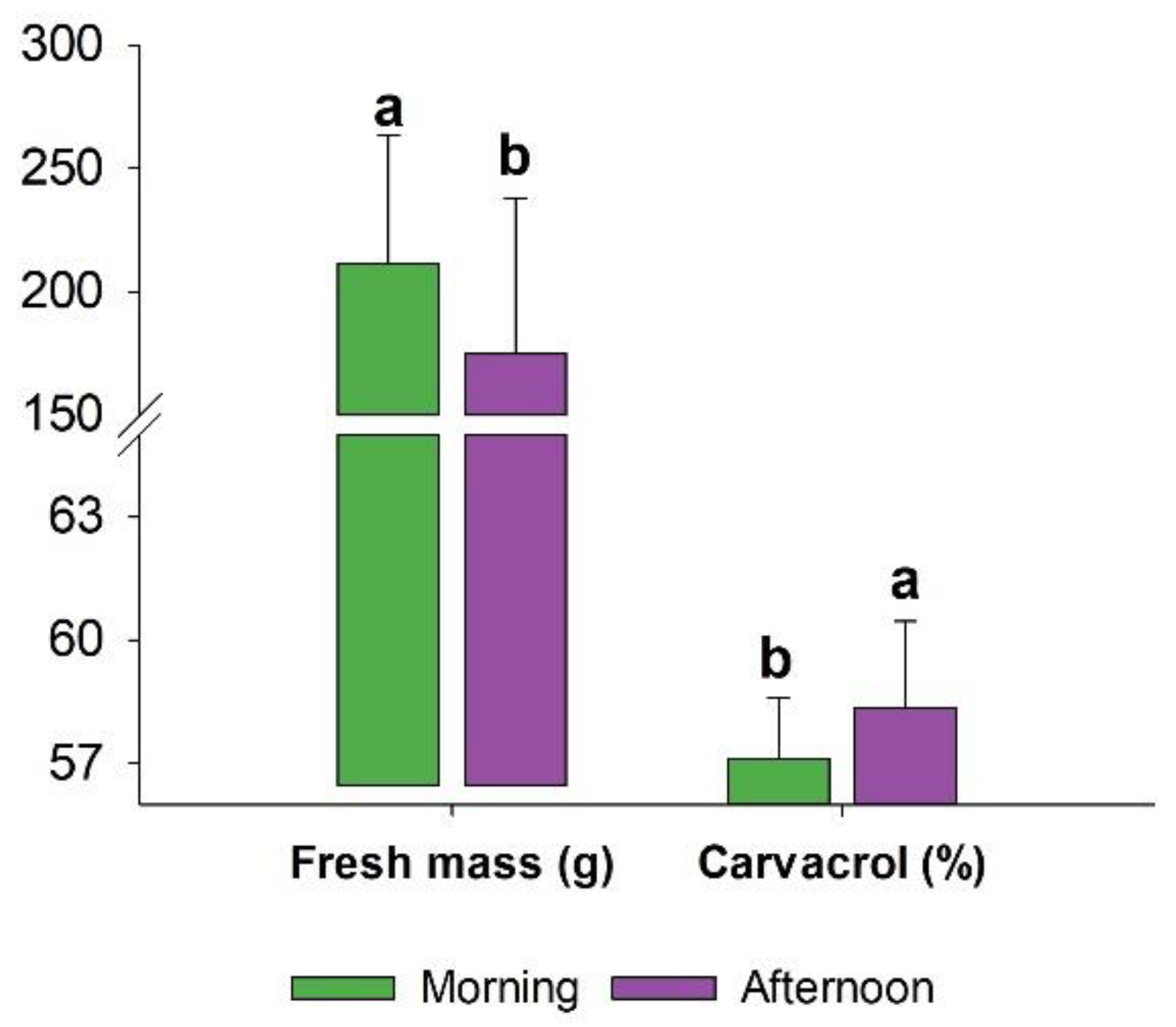

Regarding harvest time, the morning harvest resulted in higher fresh mass (211.7 g) compared with the afternoon harvest (175.0 g), whereas carvacrol content was higher in the afternoon (58.35%) than in the morning (57.12%) (

Figure 2).

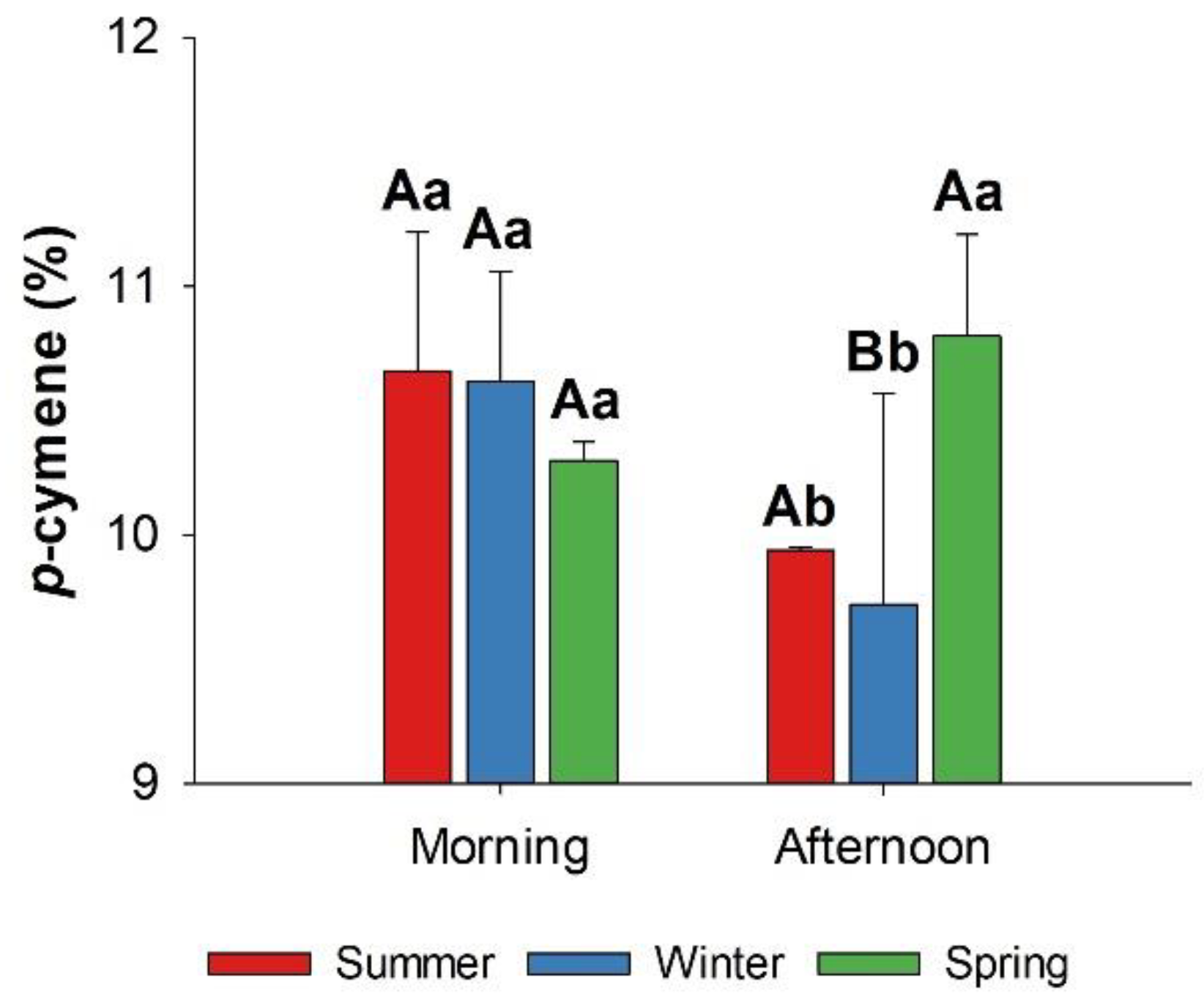

The content of the aromatic monoterpene

p-cymene varied as a function of the interaction between season and harvest time, with higher values observed in summer (10.66%) and winter (10.62%) during the morning and in spring (10.80%) during the afternoon (

Figure 3). This pattern suggests that its biosynthesis or accumulation is sensitive to solar radiation, temperature, and humidity, as well as to the plant daily metabolic cycle.

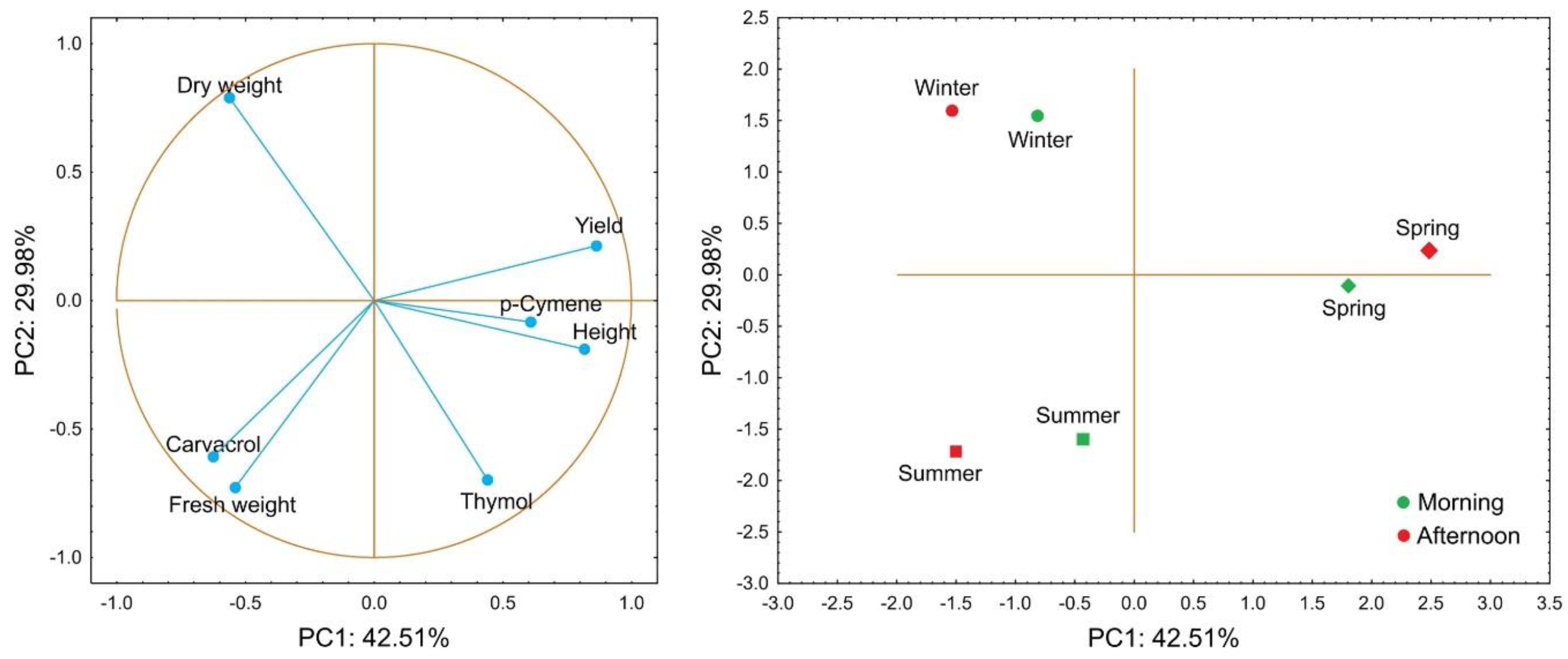

Principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to summarize the dataset, resulting in two principal components that explained most of the total variance with minimal information loss. According to the results, the first (PC1) and second (PC2) principal components accounted for 42.51% and 29.98% of the data variance, respectively, jointly explaining 72.49% of the total variability (

Figure 4). PC1 was strongly associated with EO yield, shoot length, and

p-cymene, which were in the positive quadrant of the axis, while fresh mass and carvacrol clustered in the negative quadrant. PC2 showed a strong positive correlation with dry mass and a negative correlation with thymol (

Figure 4).

The distribution of samples in the PCA scatter plot showed a clear separation among seasons and, to a lesser extent, between harvest times. Spring samples, positioned in the positive quadrant of PC1, were correlated with EO yield,

p-cymene, and shoot length, indicating that this season favored greater biomass and oil production. Winter samples, from both morning and afternoon harvests, clustered in the negative region of PC1 and positive region of PC2, whereas summer samples were concentrated in the negative quadrant, associated with lower oil yield and higher relative carvacrol content (

Figure 4).

Additionally, harvest time showed a weaker contribution to group separation than seasonal variation, although afternoon-harvested samples tended to shift slightly toward higher

p-cymene content and EO yield (

Figure 4).

3. Discussion

The results demonstrate that both season and harvest time significantly affect biomass production and the chemical composition of the

L. grata EO. The greater accumulation of fresh biomass observed in summer is likely associated with more favorable environmental conditions, particularly higher temperatures and increased solar radiation, which stimulate photosynthetic activity and vegetative growth [

14]. Similar seasonal patterns have been reported for other species of the genus

Lippia, such as

L. alba, in which greater biomass production was associated with periods of higher solar radiation [

12].

In contrast, the highest EO yield in the present study was recorded in spring, despite the lower fresh biomass observed during this season. This response may be associated with moderate water stress, which is typical of spring conditions in the semi-arid region and is known to stimulate the biosynthesis of defensive secondary metabolites, particularly monoterpenes [

9,

11]. A similar response has been reported for

Salvia officinalis, in which reduced air humidity and increased solar radiation promoted higher EO production [

9]. In addition, Tozin et al. [

5] reported that both glandular trichome density and EO production in

L. origanoides varied according to environmental conditions, reinforcing the role of microclimate in regulating EO yield.

Seasonal variation also influenced the concentration of the major aromatic compounds in the EO, with carvacrol, thymol, and

p-cymene being the predominant constituents in decreasing order. Higher contents of carvacrol and thymol were observed during summer, a season characterized by intense solar radiation and low relative humidity. Similar seasonal trends have been reported in other species native to the Caatinga. For instance, Souza et al. [

15] observed higher EO yields in

Croton sonderianus during the driest period of the year, associated with elevated temperature and solar radiation. Likewise, higher EO yields in the dry season were reported for

L. gracilis [

16], and seasonal variation in carvacrol content was documented in

L. schaueriana [

17]. Collectively, these findings indicate that plants adapted to semi-arid environments tend to enhance the production of phenolic monoterpenes under conditions of increased environmental stress.

Harvest time also played an important role in modulating EO composition. Afternoon harvesting resulted in higher carvacrol accumulation in

L. grata, which is consistent with the findings of Hazrati et al. [

9] for

Salvia officinalis, in which the highest concentrations of oxygenated compounds were also observed in the afternoon. This pattern can be explained by the daily dynamics of plant metabolism. During the afternoon, higher solar radiation and lower relative humidity favor the synthesis and accumulation of lipophilic volatile compounds, such as monoterpenes, which act as protective agents against thermal and radiation stress [

13]. Similar diurnal trends have been reported for other species of the Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae families [

5].

A study on

L. alba evaluated the effect of harvest time (morning at 09:00 h and afternoon at 13:00 h) on the volatile compound profile and EO yield. Although no statistically significant differences in EO yield were observed between harvest periods, higher levels of compounds such as nerol, geranyl acetate, β-elemene, and germacrene D were reported in the afternoon harvest [

18].

The variation in

p-cymene observed in this study further highlights the complexity of terpene metabolism. As a direct biosynthetic precursor of carvacrol and thymol,

p-cymene reflects the balance between precursor accumulation and its enzymatic conversion into phenolic monoterpenes. Its biosynthesis begins with geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP), which is converted into γ-terpinene and subsequently into

p-cymene, carvacrol, and thymol through the action of dehydrogenases and cytochrome P450 monooxygenases [

19]. The significant interaction between season and harvest time observed for

p-cymene suggests that environmental conditions strongly regulate the enzymatic steps involved in these conversions. Higher

p-cymene levels under milder conditions, such as in the morning, may indicate reduced enzymatic conversion, whereas the lower levels observed in the afternoon likely reflect increased conversion into carvacrol and thymol under stress conditions [

20].

Overall, these results demonstrate that environmental factors associated with both seasonality and the diurnal cycle strongly influence not only the quantity but also the chemical quality of the EO of L. grata. Understanding these dynamics is essential for optimizing harvest strategies aimed at maximizing EO yield and the concentration of bioactive compounds for medicinal and industrial applications.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material, Cultivation and Experimental Conditions

The experiment was conducted from January to November 2021 at the Bebedouro Experimental Station, belonging to the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa), in Petrolina, State of Pernambuco, Brazil (9°20′58.8″ S, 40°33′16.7″ W; altitude 376 m). The region presents a semi-arid climate classified as BSh according to the Köppen–Geiger climate classification [

21], with a mean annual temperature of 26.6 °C and a cumulative rainfall of 433 mm during the experimental period [

22].

A botanical voucher specimen of Lippia grata Schauer was deposited in the Herbarium of the Semi-Arid Tropics (HTSA 5979) at Embrapa. All procedures involving plant material were conducted in compliance with Brazilian legislation and were registered and authorized by the National System for the Management of Genetic Heritage and Associated Traditional Knowledge (CGen/SisGen).

Seedlings were obtained by vegetative propagation through rooting of semi-hardwood cuttings collected from healthy mother plants maintained in the Embrapa working collection. The cultivation experiment was established in raised planting beds measuring 3.0 × 1.0 m, with plant spacing of 0.5 m within rows and 1.0 m between rows. Prior to planting, beds were fertilized with 40 t ha⁻¹ of well-composted goat manure.

The soil of the experimental area presented pH of 6.8, organic matter content of 7 g kg⁻¹, available phosphorus of 34.05 mg dm⁻³, potassium of 0.59 cmolc dm⁻³, calcium of 2.40 cmolc dm⁻³, magnesium of 0.80 cmolc dm⁻³, aluminum of 0.00 cmolc dm⁻³, potential acidity (H+Al) of 2.20 cmolc dm⁻³, sum of bases (SB) of 4.10 cmolc dm⁻³, cation exchange capacity of 6.20 cmolc dm⁻³, base saturation (V) of 65%, and electrical conductivity of 0.81 mS cm⁻¹.

Each experimental plot consisted of six plants, of which four central plants constituted the useful area for evaluations, while two border plants were excluded to avoid edge effects. Irrigation was applied uniformly, corresponding to a water depth of 25 mm per application, performed four times during the cultivation cycle. Weed control was conducted manually whenever necessary, and no chemical pesticides were applied during the experiment.

Planting was carried out in July 2020, and the first harvest took place in January 2021 (summer), corresponding to 180 days after planting. The second harvest was performed in July 2021 (winter), also 180 days after the first harvest, and the third harvest was conducted in November 2021 (spring), 120 days after the second harvest. At each harvest, plants were manually collected during two daily periods: morning (08:00–09:00 h) and afternoon (13:30–14:30 h), allowing evaluation of diurnal variation.

At each harvest, environmental data were recorded, including mean air temperature, mean relative humidity, and mean global solar radiation (

Table 2). These data were used to characterize the climatic conditions during each season and harvest period (

Table 2).

4.2. Morphological Evaluations, Biomass Determination, and Preparation of Plant Material

At each harvest, L. grata plants were evaluated for vegetative growth and biomass production. Shoot length was measured using a graduated ruler, considering the distance from the plant base to the apex of the longest shoot. Total fresh biomass was determined immediately after harvest by weighing the aerial parts on an analytical balance, to minimize water loss and ensure accurate measurements.

Following morphological assessments, leaves were manually separated from stems and arranged in properly labeled trays to form representative samples of each experimental plot. The plant material was then subjected to drying under controlled conditions at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C) for five days in the Biotechnology Laboratory at Embrapa. During the drying period, samples were maintained under natural ventilation and protected from direct light to prevent thermal or photochemical degradation of volatile compounds.

After complete drying, the leaf material was weighed to determine dry biomass and subsequently homogenized. For each experimental plot, 100 g of dried leaves were used as the standard sample mass for EO extraction. EO yield was calculated based on the dry mass of the plant material and the volume of oil obtained under each experimental treatment.

4.3. EO Extraction

Dried leaf samples were manually cut into small fragments and subjected to hydrodistillation using a modified Clevenger-type apparatus (Glassco Laboratory Equipments Pvt. Ltd., Ambala Cantt, Haryana, India), following standardized procedures [

23]. Each extraction was conducted in triplicate using 100 g of dried plant material and 1.5 L of distilled water, with a total distillation time of 180 min [

24].

After extraction, the EOs were separated from the hydrolate, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, transferred to sealed amber glass vials, and stored at −20 °C until chemical analysis. EO yield was expressed as a percentage (v/m), calculated as the volume of oil obtained divided by the dry mass of plant material used in each extraction.

4.4. GC–MS and GC–FID Analysis

The chemical composition of the essential oils was determined by gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC–MS) and flame ionization detection (GC–FID) using a Shimadzu GC–MS QP2010 Ultra system equipped with an AOC-20i autosampler (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan).

Chromatographic separations were carried out on an Rtx-5MS fused-silica capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d.; 0.25 μm film thickness; Restek, Centre County, PA, USA), coated with 5% diphenyl–95% dimethylpolysiloxane. Helium (99.999%) was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.2 mL min⁻¹. Samples were injected in split mode (1:10), with an injection volume of 0.5 μL and an oil concentration of 5.0 mg mL⁻¹.

The oven temperature program was as follows: initial temperature of 50 °C for 1.5 min, increased at 4 °C min⁻¹ to 200 °C, followed by an increased of 10 °C min⁻¹ to 250 °C, with a final of 5 min.

Simultaneous acquisition of MS and FID data was achieved using a Detector Splitting System (Shimadzu Europe GmbH, Duisburg, Germany), with a split ratio of 4:1 (MS:FID). Restrictor capillaries measuring 0.62 m × 0.15 mm i.d. and 0.74 m × 0.22 mm i.d. were used to connect the splitter to the MS and FID detectors, respectively.

Mass spectra were acquired in full scan mode (m/z 40–350) using electron ionization at 70 eV, with a scan rate of 0.3 s. For FID analysis, the injector temperature was set at 250 °C, the ion source temperature at 200 °C, and hydrogen, air, and helium were supplied at flow rates of 30, 300, and 30 mL min⁻¹, respectively.

Quantification of EO constituents was performed by peak area normalization and expressed as relative percentage composition. Retention indices (RI) were calculated using a homologous series of n-alkanes (C₇–C₃₀) analyzed under identical chromatographic conditions. Compound identification was based on comparison of mass spectra with those from the NIST21, NIST107, and WILEY8 libraries, as well as comparison of calculated RI values with literature data [

25].

4.5. Statistical Analysis

The experiment followed a randomized complete block design in a 3 × 2 factorial arrangement, consisting of three seasons (summer, winter, and spring) and two harvest times (morning and afternoon), with four replications per treatment.

The statistical model was defined as:

where

Yijk represents the response variable for the

i-th replication at the

j-th season and

k-th harvest time;

μ is the overall mean;

Bi is the effect of the

i-th block (i = 1, 2, 3, 4);

Sj is the effect of the

j-th season (j = 1, 2, 3);

Tk is the effect of the

k-th harvest time (k = 1, 2);

(S × T)jk is the interaction effect between season and harvest time; and

εijk is the random error associated with the

i-th replication,

j-th season, and

k-th harvest time.

Data were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the main effects of season and harvest time, as well as their interaction effects, on yield and chemical composition of L. grata EO, using the R packages rstatix, ggpubr, and tidyverse.

Assumptions of ANOVA were evaluated through detection of outliers, analysis of residual normality using Q–Q plots and the Shapiro–Wilk test (α = 0.01), and verification of homogeneity of variances using residual plots and Levene’s test (α = 0.01). When significant effects were detected, treatment means were compared using Tukey’s post hoc test at p < 0.05.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to reduce the variables into a few principal components responsible for most of the data variance, based on the correlation matrix. PCA was performed using the software STATISTICA 12 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, USA).

5. Conclusions

Biomass production and the chemical composition of the essential oil of Lippia grata were significantly influenced by both season and harvest time. Spring yielded the highest EO production, whereas summer favored fresh biomass accumulation and higher concentrations of carvacrol and thymol. Afternoon harvesting enhanced carvacrol content, the major volatile compound of the species. These findings provide a scientific basis for defining more efficient agronomic practices aimed at maximizing both yield and chemical quality of the EO, particularly for phytotherapeutic and industrial applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.V.d.S. and F.J.V.d.O; methodology, A.V.V.d.S.; J.R.G.d.S.A. and J.M.Q.L.; formal analysis, A.V.V.d.S.; J.R.G.d.S.A.; Y.M.d.N. and J.C.V.; investigation, A.V.V.d.S.; resources, A.V.V.d.S.; data curation, A.V.V.d.S. and J.C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.d.O. and J.C.V.; writing—review and editing, A.V.V.d.S.; R.C.d.O.; J.M.Q.L. and J.C.V.; visualization, J.C.V. and A.V.V.d.S.; supervision, A.V.V.d.S.; project administration, A.V.V.d.S.; funding acquisition, A.V.V.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation and Bio Assets Brazil.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Bio Assets Brazil.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- da Silva Carvalho, K.; da Cruz, R.C.D.; de Souza, I.A. Plant species from Brazilian Caatinga: a control alternative for Aedes aegypti. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2023, 26, 102051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, K.N.; Guarniz, W.A.S.; Sá, K.M.; Freire, A.B.; Monteiro, M.P.; Nojosa, R.T.; et al. Medicinal plants of the Caatinga, northeastern Brazil: Ethnopharmacopeia (1980–1990) of the late professor Francisco José de Abreu Matos. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 237, 314–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida Lima Rocha, M.C.; Muniz de Oliveira, L. Ecogeographic study of Lippia lasiocalycina Cham. (Verbenaceae). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, H.; Matos, F.J.A.; Cavalleiro, A.D.S.; Brochini, V.F.; Souza, V.C. Plantas Medicinais no Brasil: Nativas e Exóticas, 3rd ed.; Instituto Plantarum: Nova Odessa, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tozin, L.R.; Marques, M.O.; Rodrigues, T.M. Glandular trichome density and essential oil composition in leaves and inflorescences of Lippia origanoides Kunth (Verbenaceae) in the Brazilian Cerrado. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2015, 87, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, A.P.R.; Andrade, A.L.; Pinheiro, A.D.A.; de Sousa, L.S.; Malveira, E.A.; Oliveira, F.F.M.; et al. Lippia grata essential oil acts synergistically with ampicillin against Staphylococcus aureus and its biofilm. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felix, S.F.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Rodrigues, A.L.M.; de Freitas, J.C.C.; Alves, D.R.; da Silva, A.A.; et al. Chemical composition, larvicidal activity, and enzyme inhibition of the essential oil of Lippia grata Schauer from the Caatinga biome against dengue vectors. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazim, Z.C.; Amorim, A.C.L.; Hovell, A.M.C.; Rezende, C.M.; Nascimento, I.A.; Ferreira, G.A.; Cortez, D.A.G. Seasonal variation, chemical composition, and analgesic and antimicrobial activities of the essential oil from leaves of Tetradenia riparia in Southern Brazil. Molecules 2010, 15, 5509–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazrati, S.; Beidaghi, P.; Beyraghdar Kashkooli, A.; Hosseini, S.J.; Nicola, S. Effect of harvesting time variations on essential oil yield and composition of sage (Salvia officinalis). Horticulturae 2022, 8, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palhares Neto, L.; de Souza, L.M.; de Morais, M.B.; Arruda, E.; de Figueiredo, R.C.B.Q.; de Albuquerque, C.C.; Ulisses, C. Morphophysiological and biochemical responses of Lippia grata Schauer to water deficit. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.M.; Fonseca, F.S.A.; Silva, J.C.R.L.; Silva, A.M.; Silva, J.R.; Martins, E.R. Composição do óleo essencial na população natural de Lippia origanoides (Verbenaceae) durante as estações seca e chuvosa. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2019, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, L.; Cruz, E.; Guimarães, B.; Mourão, R.; da Silva, J.; Costa, J.; Figueiredo, P. Chemometric analysis of seasonal variation in essential oil composition and antioxidant activity of a new geraniol chemotype of Lippia alba (Mill.) N.E.Br. ex Britton & P. Wilson from the Brazilian Amazon. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2022, 106, 104503. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanakis, M.K.; Papaioannou, C.; Lianopoulou, V.; Philotheou-Panou, E.; Giannakoula, A.E.; Lazari, D.M. Seasonal variation of aromatic plants under cultivation conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikosaka, K.; Ishikawa, K.; Borjigidai, A.; Muller, O.; Onoda, Y. Temperature acclimation of photosynthesis: mechanisms involved in changes in temperature dependence of photosynthetic rate. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, A.V.V.; de Britto, D.; Santos, U.S.; Bispo, L.P.; Turatti, I.C.C.; Peporine Lopes, N.; et al. Influence of season, drying temperature and extraction time on yield and chemical composition of Croton sonderianus essential oil. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2017, 29, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.V.V.; dos Santos, U.S.; Corrêa, R.M.; de Souza, D.D.; de Oliveira, F.J.V. Essential oil content and chemical composition of Lippia gracilis cultivated in the Sub-middle São Francisco Valley. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2017, 20, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.V.V.; dos Santos, U.S.; de Sá Carvalho, J.R.; Barbosa, B.D.R.; Canuto, K.M.; Rodrigues, T.H.S. Chemical composition of essential oil of leaves from Lippia schaueriana collected in the Caatinga area. Molecules 2018, 23, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, Á.F. Rendimento de óleo essencial de Lippia sidoides Cham. em função da idade de corte, horário de colheita e condições de secagem. Master`s thesis, Federal University of Tocantins, Gurupi, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, B.M.; Ketchum, R.; Croteau, D. Terpenoid Biosynthesis in Plants: A Primer on Molecular Biology, Biochemistry and Biotechnology; Springer: New York, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Llorens-Molina, J.A.; Vacas, S.; Escrivá, N.; Verdeguer, M. Seasonal variation of Thymus piperella essential oil composition. Relationship among γ-terpinene, p-cymene and carvacrol. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2022, 34, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Gonçalves, J.L.M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrapa, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Registros meteorológicos. Available online: https://lookerstudio.google.com/u/0/reporting/83744b6f-698e-488f-8ccb8d1a9e2f6b8a/page/p_7225pjqoyc (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Souza, A.V.V. Extração de óleo essencial de alecrim-do-mato (Lippia grata Schauer - Verbenaceae); Embrapa Semiárido: Petrolina, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlert, P.A.D.; Blank, A.F.; Arrigoni-Blank, M.F.; Paula, J.W.A.; Camos, D.A.; Alviano, C.S. Tempo de hidrodestilação na extração de óleo essencial de sete espécies de plantas medicinais. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2006, 8, 79–80. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Publishing: Carol Stream, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).