Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

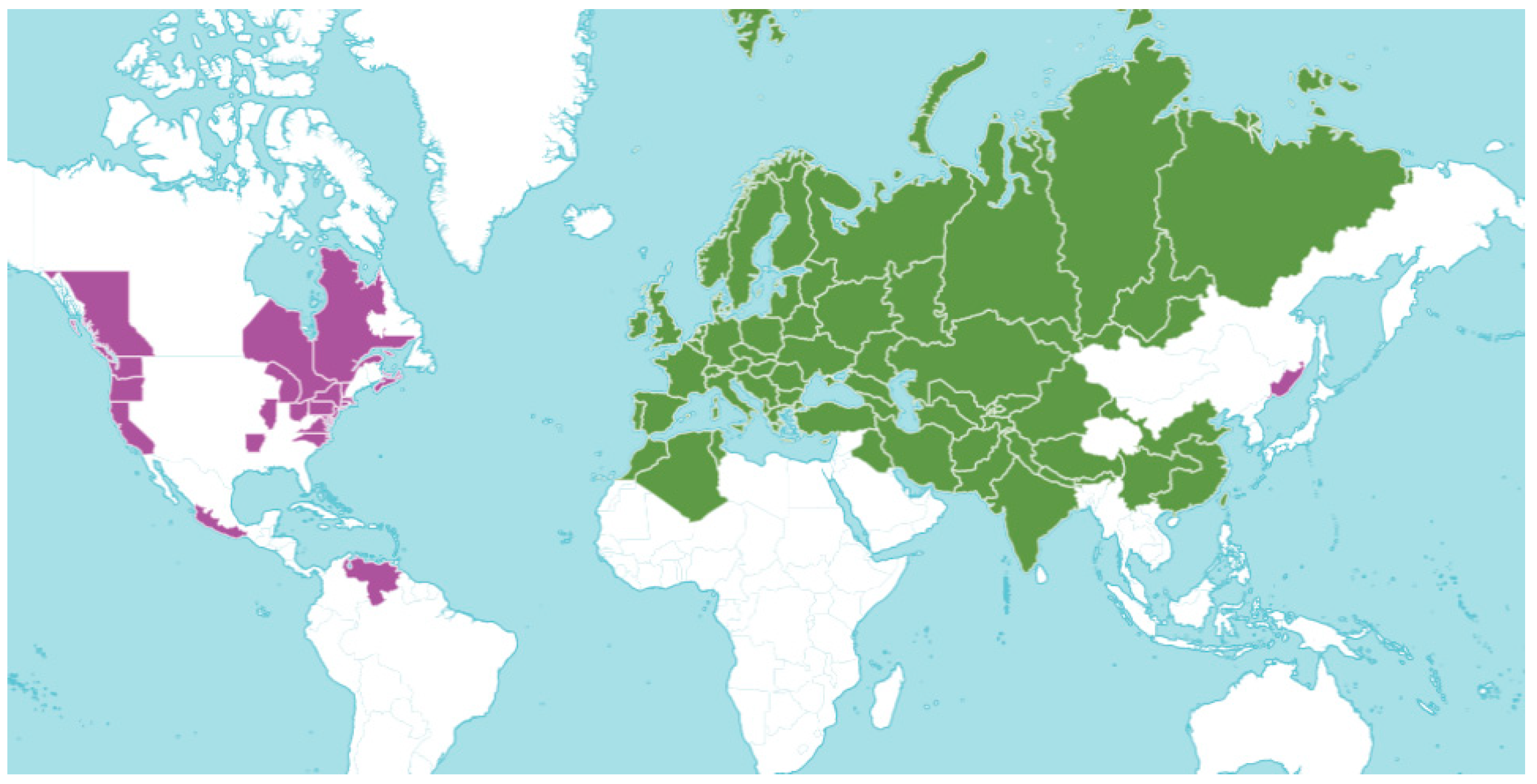

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

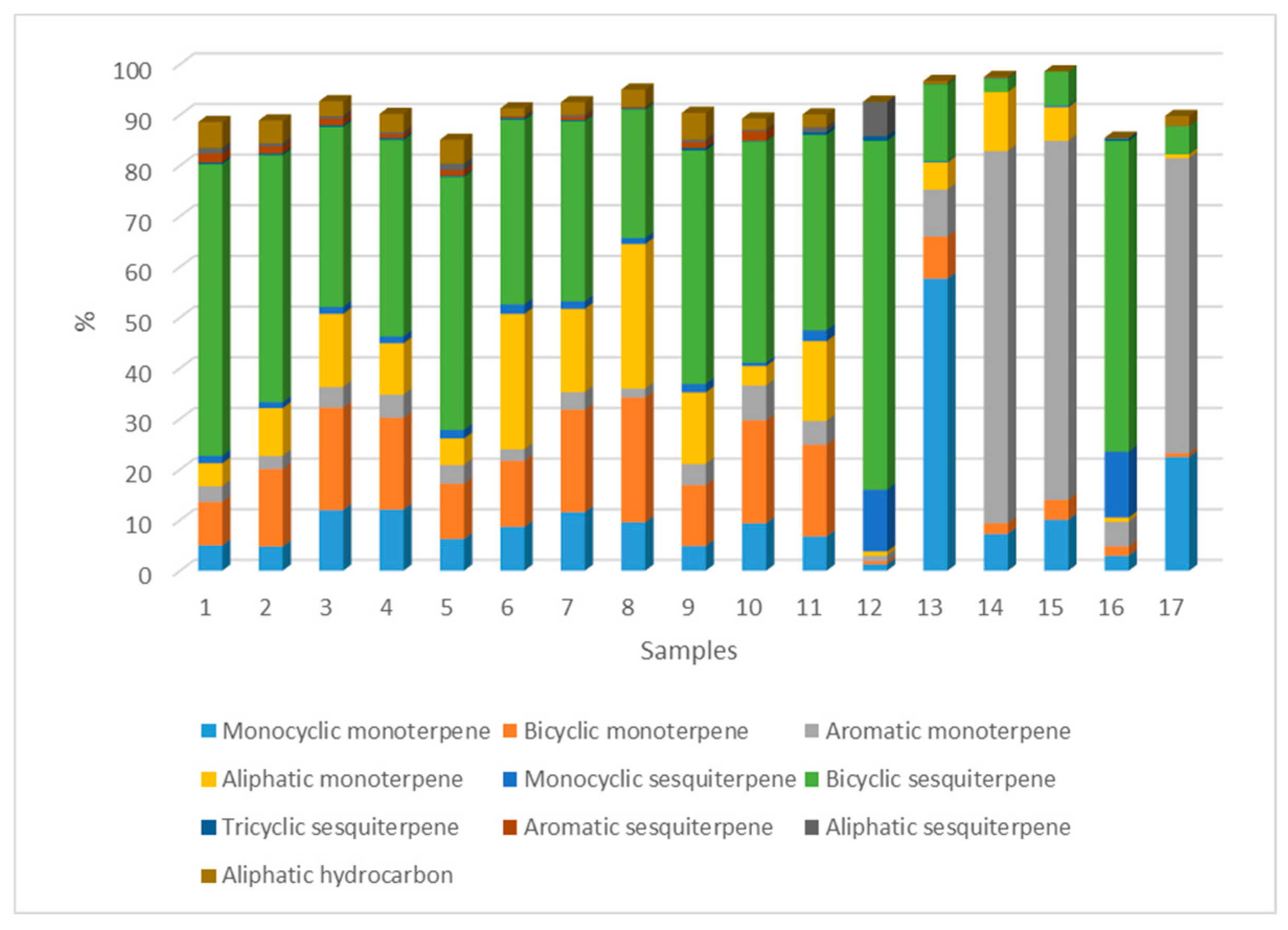

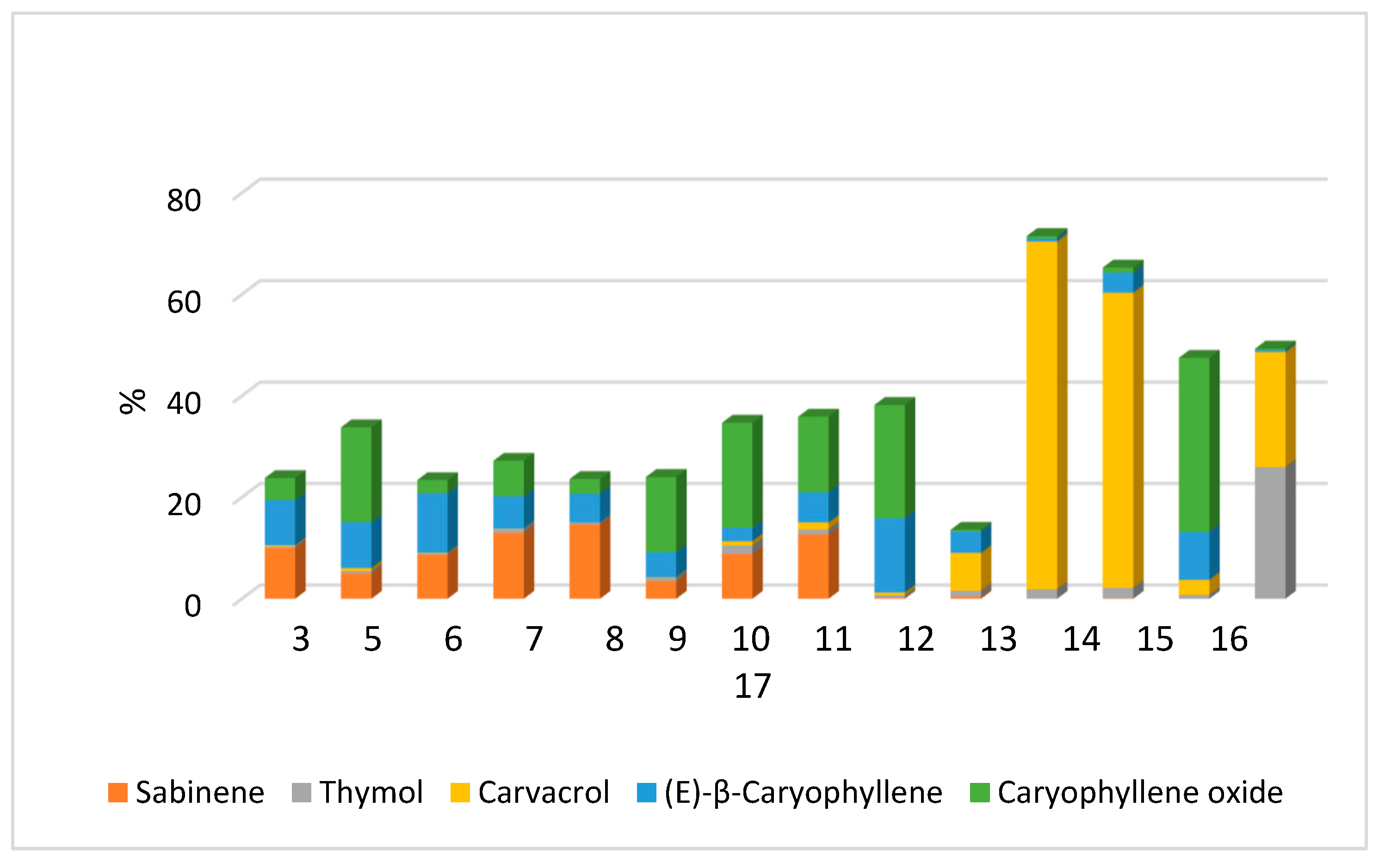

Chemotypes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| № | Compound | Group | RI | Concentration, % | |||||||||||||||||

| SPB-5 | SW-10 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |||

| The content of EO, mL/kg | 1.03 | 1.9 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 7.9 | 4.5 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 4.3 | 11.0 | 9.3 | ||||

| 1. | α-Thujene | Bicyclic monoterpene | 924 | 1024 | nd | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | nd | nd | 0.4 | 0.2 | nd | 0.1 |

| 2. | α-Рinene | Bicyclic monoterpene | 927 | 1021 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | nd | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | nd | 0.3 |

| 3. | Сamfene | Bicyclic monoterpene | 940 | 1062 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.1 | nd | nd | nd | 0.1 | 0.1 | nd | nd | nd | 0.2 | 0.1 | nd | 0.3 |

| 4. | Sabinene | Bicyclic monoterpene | 966 | 1120 | 2.8 | 8.6 | 10.0 | 5.8 | 5.0 | 8.7 | 13.0 | 14.7 | 3.5 | 8.9 | 12.7 | 0.2 | 0.4 | nd | 0.1 | nd | nd |

| 5. | β-Pinene | Bicyclic monoterpene | 968 | 1107 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 0.3 | nd | nd | |

| 6. | 1-Okten-3-ol | Aliphatic hydrocarbon | 980 | 1448 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 0.9 | 2.1 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 7. | 2-Octanone | Aliphatic hydrocarbon | 984 | 1254 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | nd | 0.5 | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 8. | β-Myrcene | Aliphatic monoterpene | 987 | 1160 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 9.3 | 1.2 | 5.3 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 1.4 | nd | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.7 | nd | 0.3 |

| 9. | 3-Oktanol | Aliphatic hydrocarbon | 994 | 1380 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 10. | α-Terpinene | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1012 | 1172 | nd | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | nd | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | nd | nd | 1.0 | 0.9 | nd | 0.4 |

| 11. | p-Cymene | Aromatic monoterpene | 1019 | 1270 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 10.7 | 1.2 | 6.2 |

| 12. | Limonene | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1022 | 1200 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 | nd | 3.9 | 0.3 | 0.4 | nd | 0.1 |

| 13. | 1,8-Cineole | Bicyclic monoterpene | 1025 | 1206 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 7.4 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | nd |

| 14. | (Z)-β-Ocimene | Aliphatic monoterpene | 1034 | 1234 | 0.6 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 10.2 | 5.8 | 12.7 | 7.7 | 1.5 | 9.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | nd | 0.1 | nd | nd |

| 15. | (E)-β-Ocimene | Aliphatic monoterpene | 1044 | 1251 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 7.3 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 0.3 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 16. | γ-Terpinen | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1052 | 1241 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 0.1 | nd | 4.3 | 5.4 | nd | 3.5 |

| 17. | (Z)-Sabinene hydrate | Bicyclic monoterpene | 1063 | 1460 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | nd | nd | 0.1 | nd | nd | nd |

| 18. | (Z)-Linalool oxide | Aliphatic monoterpene | 1066 | 1425 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.1 | 0.2 | nd | nd | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| 19. | Terpinolene | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1085 | 1274 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | nd | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | nd | nd |

| 20. | (E)-Sabinene hydrate | Bicyclic monoterpene | 1096 | 1543 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | nd | 0.9 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 21. | Linalool | Aliphatic monoterpene | 1100 | 1545 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 7.1 | 5.6 | 0.7 | |

| 22. | n-Nonanal | Aliphatic hydrocarbon | 1102 | 1400 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 23. | 1,3,8-Menthatriene | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1111 | 1139 | 0.6 | 0.7 | nd | 0.3 | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd | 0.1 | 0.1 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 24. | β-Thujone | Bicyclic monoterpene | 1118 | 1438 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 25. | Camphor | Bicyclic monoterpene | 1140 | 1502 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.2 | nd | nd |

| 26. | Isoborneol | Bicyclic monoterpene | 1154 | 1663 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | nd | nd | 0.3 | nd | 0.1 | nd | nd |

| 27. | Borneol | Bicyclic monoterpene | 1162 | 1702 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | nd | 0.2 | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd | 0.7 | 1.1 | nd | nd |

| 28. | Terpinene-4-ol | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1172 | 1595 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.2 | nd |

| 29. | Myrtenal | Bicyclic monoterpene | 1186 | 1642 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | nd | 1.1 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 30. | α-Terpineol | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1189 | 1690 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| 31. | Myrtenol | Bicyclic monoterpene | 1192 | 1762 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | nd | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 32. | n-Dekanaal | Aliphatic hydrocarbon | 1209 | 1500 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | tr | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 33. | Pulegone | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1234 | 1630 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 34. | Carvone | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1238 | 1733 | 0.2 | 0.1 | nd | 0.1 | 0.1 | tr | 0.2 | tr | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 7.9 | |

| 35. | Сarvone methyl ester | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1245 | 1630 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.4 | nd | 52.0 | 0.1 | nd | nd | 10.0 |

| 36. | Geranial | Aliphatic monoterpene | 1265 | 1720 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.2 | nd | nd | 3.5 | 0.2 | nd | nd |

| 37. | Bornyl acetate | Bicyclic monoterpene | 1273 | 1575 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 38. | Isobornyl acetate | Bicyclic monoterpene | 1283 | 1820 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.1 | nd | nd | 1.2 | 1.5 | nd |

| 39. | Thymol | Aromatic monoterpene | 1289 | 2174 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 26.0 |

| 40. | Carvacrol | Aromatic monoterpene | 1302 | 2213 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | nd | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 7.4 | 68.5 | 58.1 | 2.9 | 22.6 |

| 41. | α-Cubebene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1336 | 1450 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.1 | 0.3 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 42. | α-Ylangene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1367 | 1480 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 43. | α-Copaene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1374 | 1478 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | nd | nd |

| 44. | γ-Elemene | Monocyclic sesquiterpene | 1384 | 1575 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.8 | nd | nd | nd | 1.2 | nd |

| 45. | Geranyl acetate | Aliphatic monoterpene | 1383 | 1758 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.7 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 46. | β-Bourbonene | Tricyclic sesquiterpene | 1384 | 1519 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | nd | nd | 0.3 | nd |

| 47. | (E)-β-Caryophyllene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1409 | 1580 | 4.0 | 5.8 | 9.0 | 6.2 | 9.1 | 11.8 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 5.0 | 2.7 | 6.0 | 14.7 | 4.3 | 0.6 | 4.0 | 9.5 | 0.4 |

| 48. | n-Dodecanale | Aliphatic hydrocarbon | 1417 | 1690 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 49. | 2,6-Dimethyl-p-cymene | Aromatic monoterpene | 1419 | 1697 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.6 | nd | nd | nd | 3.5 |

| 50. | α-Humulene | Monocyclic sesquiterpene | 1441 | 1644 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 0.2 | nd | 0.2 | 1.9 | nd |

| 51. | Alloaromadendrene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1450 | 1625 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | nd | |

| 52. | γ-Muurolene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1468 | 1688 | nd | nd | 0.3 | nd | 0.3 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.1 | nd | nd | nd | 0.2 | nd |

| 53. | Germacrene D | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1470 | 1690 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 4.6 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 6.0 | 13.5 | 6.3 | nd | 0.1 | 8.7 | nd |

| 54. | ar-Curcumene | Aromatic sesquiterpene | 1479 | 1790 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | nd | 0.2 | 0.5 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 55. | β-Ionone | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1486 | 1922 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | nd | nd | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 56. | α-Muurolene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1491 | 1730 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | nd | 0.4 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.9 | nd |

| 57. | Bicyclogermacrene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1500 | 1712 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | nd | 1.6 | 3.6 | 0.9 | 0.1 | nd | nd | nd |

| 58. | α-Selinene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1503 | 1707 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 1.6 | nd | 0.3 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 59. | γ-Cadinene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1504 | 1752 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | nd | 0.4 | 3.3 |

| 60. | n-Tridecanal | Aliphatic hydrocarbon | 1508 | 1795 | 0.2 | 0.1 | nd | nd | 0.4 | 0.1 | nd | 0.1 | 0.1 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 61. | β-Bisabolene | Monocyclic sesquiterpene | 1508 | 1736 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 5.0 | nd | nd | 0.1 | 3.4 | nd |

| 62. | δ-Cadinene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1516 | 1740 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 0.3 | nd | 0.2 | 0.8 | 1.4 |

| 63. | Cadina-1,4-dieen | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1527 | 1800 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | tr | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | nd | nd | 0.1 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 64. | α-Cadinene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1538 | 1738 | nd | nd | 0.3 | 0.6 | nd | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd | 0.4 | nd | nd | nd | 0.4 | nd |

| 65. | α-Calacorene | Aromatic sesquiterpene | 1540 | 1896 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 1.4 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 66. | Hedycariol | Monocyclic sesquiterpene | 1548 | 2077 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.2 | nd | nd | nd | 1.8 | nd |

| 67. | (E)-Calamenene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1551 | 1850 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 68. | (E)-Nerolidol | Aliphatic sesquiterpene | 1565 | 2055 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.3 | 0.5 | nd | nd | nd | 0.3 | nd |

| 69. | Spathulenol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1568 | 2115 | 12.1 | 8.7 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 5.9 | 3.2 | nd | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.2 |

| 70. | Caryophyllene oxide | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1572 | 1960 | 17.3 | 16.7 | 4.3 | 11.9 | 18.7 | 2.6 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 14.8 | 20.7 | 14.9 | 22.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 34.3 | 0.3 |

| 71. | Germacrene D-4-ol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1583 | 2018 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.0 | nd | nd | nd | 0.9 | nd |

| 72. | Globulol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1588 | 2050 | 0.1 | 0.1 | nd | 0.2 | 0.2 | nd | 0.2 | nd | 0.3 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 73. | Humulene oxide | Monocyclic sesquiterpene | 1592 | 2032 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 2.7 | nd | nd | nd | 4.7 | nd |

| 74. | Ledol | Tricyclic sesquiterpene | 1594 | 2022 | nd | 0.3 | 0.4 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | |||||||||

| 75. | Caryophyllene epoxide | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1594 | 1990 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 3.0 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 76. | Viridiflorol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1602 | 2074 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.7 | 0.2 | nd | nd | 0.2 | nd |

| 77. | Geranylisovaleriate | Aliphatic monoterpene | 1604 | 1885 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 78. | Cubenol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1626 | 2055 | nd | nd | nd | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | nd | nd | 0.5 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 79. | τ-Cadinol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1635 | 2167 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 1.1 | nd | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 80. | Epicubenol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1638 | 2087 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.6 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 81. | T-Murolol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1644 | 2193 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.3 | 3.3 | 0.3 | nd | nd | 1.6 | nd |

| 82. | α-Eudesmol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1649 | 2216 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 4.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 0.8 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 83. | α-Cadinol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1659 | 2218 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | nd | nd | 0.4 | nd | 2.0 | 4.7 | nd | 0.2 | nd | 1.7 | nd |

| 84. | δ-Cadinol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1664 | 2150 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | nd | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.1 | nd | nd | 0.4 | nd | nd | nd |

| 85. | Eudesma-4(15),7-dien-1-β-ol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 1677 | 2364 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 1.4 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 86. | n-Heptadecane | Aliphatic hydrocarbon | 1700 | 1700 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | nd | 0.4 | 0.2 | nd | nd | 0.3 | nd | nd | nd | 1.0 |

| 87. | Farnesol | Aliphatic sesquiterpene | 1752 | 2330 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 | nd | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 6.3 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.1 |

| 88. | Hexahydrofarnesyl acetone | Aliphatic sesquiterpene | 1842 | 2069 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | nd | 0.1 | 0.1 | nd | nd | nd | 0.2 | nd | nd | nd |

| 89. | Palmitic acid | Aliphatic hydrocarbon | 1985 | 2930 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 | nd | 1.7 | nd | 0.1 | nd | 0.4 | nd | nd | nd | 0.3 | 0.1 | nd | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Unidentified compounds, % | 11.4 | 11.1 | 7.3 | 9.8 | 14.9 | 8.7 | 7.5 | 5 | 9.6 | 10.7 | 9.9 | 7.4 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 13.7 | 10.2 | ||||

| Identified compounds, % | 88.6 | 88.9 | 92.7 | 90.2 | 85.1 | 91.3 | 92.5 | 95 | 90.4 | 89.3 | 90.1 | 92.6 | 96.7 | 97.5 | 98.6 | 86.3 | 89.8 | ||||

References

- Knapp, W.M.; Naczi, R.F.C. Vascular Plants of Maryland, USA: A Comprehensive Account of the State’s Botanical Diversity; Smithsonian Contributions to Botany; Smithsonian Institution; National Museum of Natural History; Carnegie Museum of Natural History; 2021; ISBN 0081-024X. [Google Scholar]

- Cinbilgel, I.; Kurt, Y. Oregano and/or Marjoram: Traditional Oil Production and Ethnomedical Utilization of Origanum Species in Southern Turkey. Journal of Herbal Medicine 2019, 16, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFO. Origanum vulgare L. 2024.

- Ilić, Z.; Stanojević, L.; Milenković, L.; Šunić, L.; Milenković, A.; Stanojević, J.; Cvetković, D. The Yield, Chemical Composition, and Antioxidant Activities of Essential Oils from Different Plant Parts of the Wild and Cultivated Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.). Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee-Hajiabad, M.; Novak, J.; Honermeier, B. Characterization of Glandular Trichomes in Four Origanum vulgare L. Accessions Influenced by Light Reduction. Journal of Applied Botany and Food Quality 2015, 88, 300307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivask, K.; Orav, A.; Kailas, T.; Raal, A.; Arak, E.; Paaver, U. Composition of the Essential Oil from Wild Marjoram ( Origanum vulgare L. ssp. vulgare) Cultivated in Estonia. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2005, 17, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, B.; Schmiderer, C.; Novak, J. Phytochemical Diversity of Origanum vulgare L. subsp. vulgare (Lamiaceae) from Austria. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 2013, 50, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, M.; Sinniah, U. A Comprehensive Review on the Phytochemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of Pogostemon Cablin Benth.: An Aromatic Medicinal Plant of Industrial Importance. Molecules 2015, 20, 8521–8547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, B.; Hecer, C.; Kaynarca, D.; Berkan, Ş. Effect of Oregano Essential Oil and Aqueous Oregano Infusion Application on Microbiological Properties of Samarella (Tsamarella), a Traditional Meat Product of Cyprus. Foods 2018, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tmušić, N.; Ilić, Z.S.; Milenković, L.; Šunić, L.; Lalević, D.; Kevrešan, Ž.; Mastilović, J.; Stanojević, L.; Cvetković, D. Shading of Medical Plants Affects the Phytochemical Quality of Herbal Extracts. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarinho, A.T.P.; Dias, N.F.; Camilloto, G.P.; Cruz, R.S.; Otoni, C.G.; Moraes, A.R.F.; Soares, N.D.F.F. Sliced Bread Preservation through Oregano Essential Oil-Containing Sachet. J Food Process Engineering 2014, 37, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, C.M.; Grosso, N.R.; Rodolfo Juliani, H. Quality Preservation of Organic Cottage Cheese Using Oregano Essential Oils. LWT Food Science and Technology 2015, 60, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha Krishnan, K.; Babuskin, S.; Babu, P.A.S.; Fayidh, M.A.; Sabina, K.; Archana, G.; Sivarajan, M.; Sukumar, M. Bio Protection and Preservation of Raw Beef Meat Using Pungent Aromatic Plant Substances. J Sci Food Agric 2014, 94, 2456–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plati, F.; Paraskevopoulou, A. Micro- and Nano-Encapsulation as ‘Tools for Essential Oils Advantages’ Exploitation in Food Applications: The Case of Oregano Essential Oil. Food Bioprocess Technol 2022, 15, 949–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes-Quero, G.M.; Esteban-Rubio, S.; Pérez Cano, J.; Aguilar, M.R.; Vázquez-Lasa, B. Oregano Essential Oil Micro- and Nanoencapsulation With Bioactive Properties for Biotechnological and Biomedical Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 703684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, A. Maailma Ravimtaimede Entsüklopeedia; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ekor, M. The Growing Use of Herbal Medicines: Issues Relating to Adverse Reactions and Challenges in Monitoring Safety. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Tewari, G.; Pandey, H.K.; Kumari, A. Exploration of Productivity, Chemical Composition, and Antioxidant Potential of Origanum vulgare L. Grown at Different Geographical Locations of Western Himalaya, India. Journal of Chemistry 2021, 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojević, L.; Stanojević, J.; Cvetković, D.; Ilić, D. Antioxidant Activity of Oregano Essential Oil (Origanum vulgare L.). Biologica Nyssana 2016, 7, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, L.; Ilić, Z.S.; Šunić, L.; Tmušić, N.; Stanojević, L.; Stanojević, J.; Cvetković, D. Modification of Light Intensity Influence Essential Oils Content, Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Thyme, Marjoram and Oregano. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2021, 28, 6532–6543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu-Ingok, A.; Devecioglu, D.; Dikmetas, D.N.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Capanoglu, E. Antibacterial, Antifungal, Antimycotoxigenic, and Antioxidant Activities of Essential Oils: An Updated Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghrovyan, A.; Sahakyan, N.; Babayan, A.; Chichoyan, N.; Petrosyan, M.; Trchounian, A. Essential Oil and Ethanol Extract of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) from Armenian Flora as a Natural Source of Terpenes, Flavonoids and Other Phytochemicals with Antiradical, Antioxidant, Metal Chelating, Tyrosinase Inhibitory and Antibacterial Activity. CPD 2019, 25, 1809–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, D.; Chanotiya, C.S.; Rana, M.; Semwal, M. Variability in Essential Oil and Bioactive Chiral Monoterpenoid Compositions of Indian Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) Populations from Northwestern Himalaya and Their Chemotaxonomy. Industrial Crops and Products 2009, 30, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.S.; Padalia, R.C.; Chauhan, A. Volatile Constituents of Origanum vulgare L., ‘Thymol’ Chemotype: Variability in North India during Plant Ontogeny. Natural Product Research 2012, 26, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, B.; Marques, A.; Ramos, C.; Serrano, C.; Matos, O.; Neng, N.R.; Nogueira, J.M.F.; Saraiva, J.A.; Nunes, M.L. Chemical Composition and Bioactivity of Different Oregano (Origanum vulgare) Extracts and Essential Oil. J Sci Food Agric 2013, 93, 2707–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilbrey, J.A.; Ortiz, Y.T.; Felix, J.S.; McMahon, L.R.; Wilkerson, J.L. Evaluation of the Terpenes β-Caryophyllene, α-Terpineol, and γ-Terpinene in the Mouse Chronic Constriction Injury Model of Neuropathic Pain: Possible Cannabinoid Receptor Involvement. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nostro, A.; Roccaro, A.S.; Bisignano, G.; Marino, A.; Cannatelli, M.A.; Pizzimenti, F.C.; Cioni, P.L.; Procopio, F.; Blanco, A.R. Effects of Oregano, Carvacrol and Thymol on Staphylococcus Aureus and Staphylococcus Epidermidis Biofilms. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2007, 56, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosakowska, O.; Czupa, W. Morphological and Chemical Variability of Common Oregano (Origanum vulgare L. subsp. vulgare) Occurring in Eastern Poland. Herba Polonica 2018, 64, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, R.; Xian, M.; Liu, H. Biosynthesis and Production of Sabinene: Current State and Perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 102, 1535–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruľová, D.; Caputo, L.; Elshafie, H.S.; Baranová, B.; De Martino, L.; Sedlák, V.; Gogaľová, Z.; Poráčová, J.; Camele, I.; De Feo, V. Thymol Chemotype Origanum vulgare L. Essential Oil as a Potential Selective Bio-Based Herbicide on Monocot Plant Species. Molecules 2020, 25, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocoll, C.; Asbach, J.; Novak, J.; Gershenzon, J.; Degenhardt, J. Terpene Synthases of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) and Their Roles in the Pathway and Regulation of Terpene Biosynthesis. Plant Mol Biol 2010, 73, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshedloo, M.R.; Salami, S.A.; Nazeri, V.; Maggi, F.; Craker, L. Essential Oil Profile of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) Populations Grown under Similar Soil and Climate Conditions. Industrial Crops and Products 2018, 119, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordiei, K.R.; Gontova, T.N.; Gubar, S.N.; Yaremenko, M.S.; Kotova, E.E. Study of the Qualitative Composition and Quantitative Content of Parthenolide in the Feverfew (Tanacetum Parthenium) Herb Cultivated in Ukraine. European Pharmaceutical Journal 2020, 67, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordiei, K.; Gontova, T.; Trumbeckaite, S.; Yaremenko, M.; Raudone, L. Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Tanacetum Parthenium Cultivated in Different Regions of Ukraine: Insights into the Flavonoids and Hydroxycinnamic Acids Profile. Plants 2023, 12, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raal, A.; Gontova, T.; Palmeos, M.; Orav, A.; Sayakova, G.; Koshovyi, O. Comparative Analysis of Content and Composition of Essential Oils of Thymus Vulgaris L. from Different Regions of Europe. PEAS 2024, 73, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshedloo, M.R.; Mumivand, H.; Craker, L.E.; Maggi, F. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oils in Origanum vulgare subsp. gracile at Different Phenological Stages and Plant Parts. J Food Process Preserv 2018, 42, e13516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Pharmacopoeia, 11th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, 2022.

- Raal, A.; Komarov, R.; Orav, A.; Kapp, K.; Grytsyk, A.; Koshovyi, O. Chemical Composition of Essential Oil of Common Juniper (Juniperus communis L.) Branches from Estonia. SR: PS 2022, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.J.; Carter, O.A.; Zhang, Y.; Matthews, B.W.; Croteau, R.B. Bifunctional Abietadiene Synthase: Mutual Structural Dependence of the Active Sites for Protonation-Initiated and Ionization-Initiated Cyclizations. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 2700–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, J.; Zuzarte, M.; Liberal, J.; Gonçalves, M.J.; Lopes, M.C.; Cavaleiro, C.; Cruz, M.T.; Salgueiro, L. Margotia Gummifera Essential Oil as a Source of Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Industrial Crops and Products 2013, 47, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, K.A.D.S.; Rodrigues, N.V.S.; Kozhevnikov, I.V.; Gusevskaya, E.V. Heteropoly Acid Catalysts in the Valorization of the Essential Oils: Acetoxylation of β-Caryophyllene. Applied Catalysis A: General 2010, 374, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Oliveira, G.L.; da Silva, B.V.; da Silva Lopes, L. Safety and Toxicology of the Dietary Cannabinoid β-Caryophyllene. In Neurobiology and Physiology of the Endocannabinoid System; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 481–492. ISBN 978-0-323-90877-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francomano, F.; Caruso, A.; Barbarossa, A.; Fazio, A.; La Torre, C.; Ceramella, J.; Mallamaci, R.; Saturnino, C.; Iacopetta, D.; Sinicropi, M.S. β-Caryophyllene: A Sesquiterpene with Countless Biological Properties. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Cho, S.K.; Kim, K.-D.; Nam, D.; Chung, W.-S.; Jang, H.-J.; Lee, S.-G.; Shim, B.S.; Sethi, G.; Ahn, K.S. β-Caryophyllene Oxide Potentiates TNFα-Induced Apoptosis and Inhibits Invasion through down-Modulation of NF-κB-Regulated Gene Products. Apoptosis 2014, 19, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R. Herb Yield and Chemical Composition of Common Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) Essential Oil According to the Plant’s Developmental Stage. Herba Polonica 2009, 55, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrou, E.; Tsivelika, N.; Chatzopoulou, P.; Tsakalidis, G.; Menexes, G.; Mavromatis, A. Conventional Breeding of Greek Oregano (Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum) and Development of Improved Cultivars for Yield Potential and Essential Oil Quality. Euphytica 2017, 213, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, N.K.; Singh, S.; Haider, S.Z.; Lohani, H. Influence of Phenological Stages on Yield and Quality of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) Under the Agroclimatic Condition of Doon Valley (Uttarakhand). Indian J Pharm Sci 2013, 75, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, A.; Hadian, J.; Gholami, M.; Friedt, W.; Honermeier, B. Correlations between Genetic, Morphological, and Chemical Diversities in a Germplasm Collection of the Medicinal Plant Origanum vulgare L. Chemistry & Biodiversity 2012, 9, 2784–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.Y.; Liu, W.H.; Lv, G.Y.; Zhou, X. Analysis of Essential Oils of Origanum vulgare from Six Production Areas of China and Pakistan. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 2014, 24, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechergui, K.; Jaouadi, W.; Coelho, J.A.; Serra, M.C.; Khouja, M.L. Biological Activities and Oil Properties of Origanum Glandulosum Desf: A Review. Phytothérapie 2016, 14, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, B.; Schmiderer, C.; Novak, J. Essential Oil Diversity of European Origanum vulgare L. (Lamiaceae). Phytochemistry 2015, 119, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinno, P.; Guantario, B.; Lombardi, G.; Ranaldi, G.; Finamore, A.; Allegra, S.; Mammano, M.M.; Fascella, G.; Raffo, A.; Roselli, M. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of Essential Oils from Origanum vulgare Genotypes Belonging to the Carvacrol and Thymol Chemotypes. Plants 2023, 12, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryvtsova, M.; Hrytsyna, M.; Salamon, I. Chemical composition and antimicrobial properties of essential oil from Origanum vulgare L. in different habitats. Biotechnol. acta 2020, 13, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vokou, D.; Kokkini, S.; Bessiere, J.-M. Geographic Variation of Greek Oregano (Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum) Essential Oils. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 1993, 21, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkini, S.; Karousou, R.; Dardioti, A.; Krigas, N.; Lanaras, T. Autumn Essential Oils of Greek Oregano. Phytochemistry 1997, 44, 883–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, O.; Kanyal, L.; Chandra, M.; Pant, A. Chemical Diversity and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oils among Different Accessions of Origanum vulgare L. Collected from Uttarakhand Region. Indian Journal of Natural Products and Resources. 2013, 4, 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, M. Herbage Yield, Essential Oil Content and Components of Cultivated and Naturally Grown Origanum Syriacum. Sci. Pap.-Ser. A Agron. 2016, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Khan, S.T.; Khan, N.A.; Mahmood, A.; Al-Kedhairy, A.A.; Alkhathlan, H.Z. The Composition of the Essential Oil and Aqueous Distillate of Origanum vulgare L. Growing in Saudi Arabia and Evaluation of Their Antibacterial Activity. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2018, 11, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, E.; Giovino, A.; Carrubba, A.; How Yuen Siong, V.; Rinoldo, C.; Nina, O.; Ruberto, G. Variations of Essential Oil Constituents in Oregano (Origanum vulgare subsp. viridulum (= O. heracleoticum) over Cultivation Cycles. Plants 2020, 9, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retta, D.S.; González, S.B.; Guerra, P.E.; Van Baren, C.M.; Di Leo Lira, P.; Bandoni, A.L. Essential Oils of Native and Naturalized Lamiaceae Species Growing in the Patagonia Region (Argentina). Journal of Essential Oil Research 2017, 29, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockutë, D.; Judþentienë, A.; Bernotienë, G. Volatile Constituents of Cultivated Origanum vulgare L. Inflorescences and Leaves. CHEMIJA 2004, 15, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kilic, Ö.; Özdemir, F.A. Variability of Essential Oil Composition of Origanum vulgare L. subsp. gracile Populations from Turkey. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 2016, 19, 2083–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, S.; Rashid, M.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Ahmad, P. Biological Efficacy of Essential Oils and Plant Extracts of Cultivated and Wild Ecotypes of Origanum vulgare L. BioMed Research International 2020, 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steševića, D.; Jaćimović, Z.; Šatović, Z.; Šapčanine, A.; Jančan, G.; Kosović, M.; Damjanović-Vratnica, B. Chemical Characterization of Wild Growing Origanum vulgare Populations in Montenegro. Natural Product Communications 2018, 13, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, J.; Xu, X. [Advances in research of pharmacological effects and formulation studies of linalool]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2015, 40, 3530–3533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Sample | Type of raw material | Аrea of cultivation | Method of collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Leaves (vegetative phase) | Kehtna municipality, Estonia | Collected |

| 2 | Leaves and flower buds (budding phase) | Kehtna municipality, Estonia | Collected |

| 3 | Leaves and blooming flowers (flowering phase) | Kehtna municipality, Estonia | Collected |

| 4 | Leaves and flowers (end of flowering phase) | Kehtna municipality, Estonia | Collected |

| 5 | Leaves and flowers | Varbla municipality, Estonia | Collected |

| 6 | Leaves and flowers | Rapla municipality, Estonia | Collected |

| 7 | Leaves and flowers | Sangaste vald, Estonia | Collected |

| 8 | Leaves and flowers | Märjamaa municipality, Estonia | Collected |

| 9 | Leaves and flowers | Padise municipality, Estonia | Collected |

| 10 | Leaves and flowers | Energia talu, Estonia | Commercial sample from herb farm |

| 11 | Leaves and flowers | Vadi firma, Estonia | Commercial sample from herb farm |

| 12 | Leaves and flowers | Kesklinna Pharmacy, Tartu, Estonia | Commercial sample from pharmacy |

| 13 | Leaves and flowers | Kubja herb farm, Estonia | Commercial sample from herb farm |

| 14 | Leaves and flowers | Turkey | Commercial sample from pharmacy |

| 15 | Leaves and flowers | Scotland | Commercial sample from pharmacy |

| 16 | Leaves and flowers | Moldova | Commercial sample from pharmacy |

| 17 | Leaves and flowers | Italy | Commercial sample from pharmacy |

| Groups of components (number of substances) |

Average content (values of component groups, %) |

|---|---|

| Monoterpenoids | |

| Aliphatic (8) | 10.3 (0.7-28.5) |

| Aromatic (4) | 15.3 (1.1-73.5) |

| Monocyclic (11) | 11.4 (1.3-57.7) |

| Bicyclic (16) | 11.69 (0.6-24.6) |

| Total (39) | 48.57 |

| Sesquiterpenoids | |

| Aliphatic (3) | 0.8 (0-6.8) |

| Aromatic 2 | 0.6 (0-1.9) |

| Monocyclic 5 | 2.5 (0-13) |

| Bicyclic 29 | 36.3 (2.7-68.9) |

| Tricyclic 2 | 0.3 (0-0.5) |

| Total (41) | 40.48 |

| Other substances not classified as mono- and sesquiterpenoids | |

| Aliphatic hydrocarbons (9) | 2.4 (0-5.3) |

| Compound | Sample * | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

| Thymol, % | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 1 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 26 |

| Carvacrol, % | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | nd | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 7.4 | 68.5 | 58.1 | 2.9 | 22.6 |

| The sum of substances, % | 0.5 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1 | 8.6 | 70.4 | 60.2 | 3.7 | 48.6 |

| Compound | Group/structural characteristics | Number of samples | Average content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sabinene | Bicyclic monoterpene | 11 | 5.5 |

| 1-Okten-3-ol | Aliphatic hydrocarbon | 8 | 0.9 |

| β-Myrcene | Aliphatic monoterpene | 11 | 1.7 |

| p-Cymene | 14 | 3.2 | |

| Aromatic monoterpene | |||

| 1,8-Cineole | Bicyclic monoterpene | 13 | 2.4 |

| (Z)-β-Ocimene | Aliphatic monoterpene | 11 | 3.9 |

| (E)-β-Ocimene | Aliphatic monoterpene | 10 | 2.3 |

| γ-Terpinen | Monocyclic monoterpene | 12 | 1.8 |

| Linalool | Aliphatic monoterpene | 13 | 2.1 |

| Terpinene-4-ol | Monocyclic monoterpene | 13 | 2.0 |

| α-Terpineol | Monocyclic monoterpene | 14 | 1.1 |

| Сarvone methyl ester | Monocyclic monoterpene | 4 | 4.5 |

| Carvacrol | Aromatic monoterpene | 13 | 12.5 |

| (E)-β-Caryophyllene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 14 | 6.4 |

| Germacrene D | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 12 | 4.2 |

| Spathulenol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 13 | 1.9 |

| Caryophyllene oxide | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 14 | 0.8 |

| Humulene oxide | Monocyclic sesquiterpene | 10 | 0.8 |

| Caryophyllene epoxide | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 7 | 0.8 |

| α-Eudesmol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 7 | 1.2 |

| Sample | Plant phenophase | Essential oil content, mL/kg | Total content of identified components in EO, % | Thymol in EO, % | Carvacrol in EO, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vegetation | 1.0 | 88.6 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| 2 | Budding | 1.9 | 88.9 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| 3 | Mass flowering | 5.1 | 92.7 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| 4 | End of flowering | 4.8 | 90.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Compound | Group | Content in EO (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation | Budding | Mass flowering | End of flowering | ||

| Sabinene | Bicyclic monoterpene | 2.8 | 8.6 | 10 | 5.8 |

| (E)-Sabinene hydrate | Bicyclic monoterpene | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 2 |

| 1,8-Cineole | Bicyclic monoterpene | 3 | 3.3 | 5.8 | 5.3 |

| p-Cymene | Aromatic monoterpene | 1.6 | 1.9 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| (Z)-β-Ocimene | Aliphatic monoterpene | 0.6 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 2.6 |

| (E)-β-Ocimene | Aliphatic monoterpene | 0.1 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 1.9 |

| Linalool | Aliphatic monoterpene | 2.1 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 4.2 |

| Terpinene-4-ol | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1.3 | 1.1 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| α-Terpineol | Monocyclic monoterpene | 1.3 | 1.1 | 3 | 3.5 |

| (E)-β-Caryophyllene | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 4 | 5.8 | 9 | 6.2 |

| Germacrene D | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 2.4 | 2.1 | 4.6 | 2.4 |

| Spathulenol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 12.1 | 8.7 | 4.3 | 3.1 |

| Caryophyllene oxide | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 17.3 | 16.7 | 4.3 | 11.9 |

| Caryophyllene epoxide | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 2.6 | 1.9 | 1 | 2 |

| α-Eudesmol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 3.6 | 2 | 3.1 | 1.7 |

| δ-Cadinol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 2.3 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 1.3 |

| Eudesma-4(15),7-dien-1-β-ol | Bicyclic sesquiterpene | 3.6 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Total amount, % | 61 | 63.7 | 68 | 64 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).