Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. White Rabbit Protocol

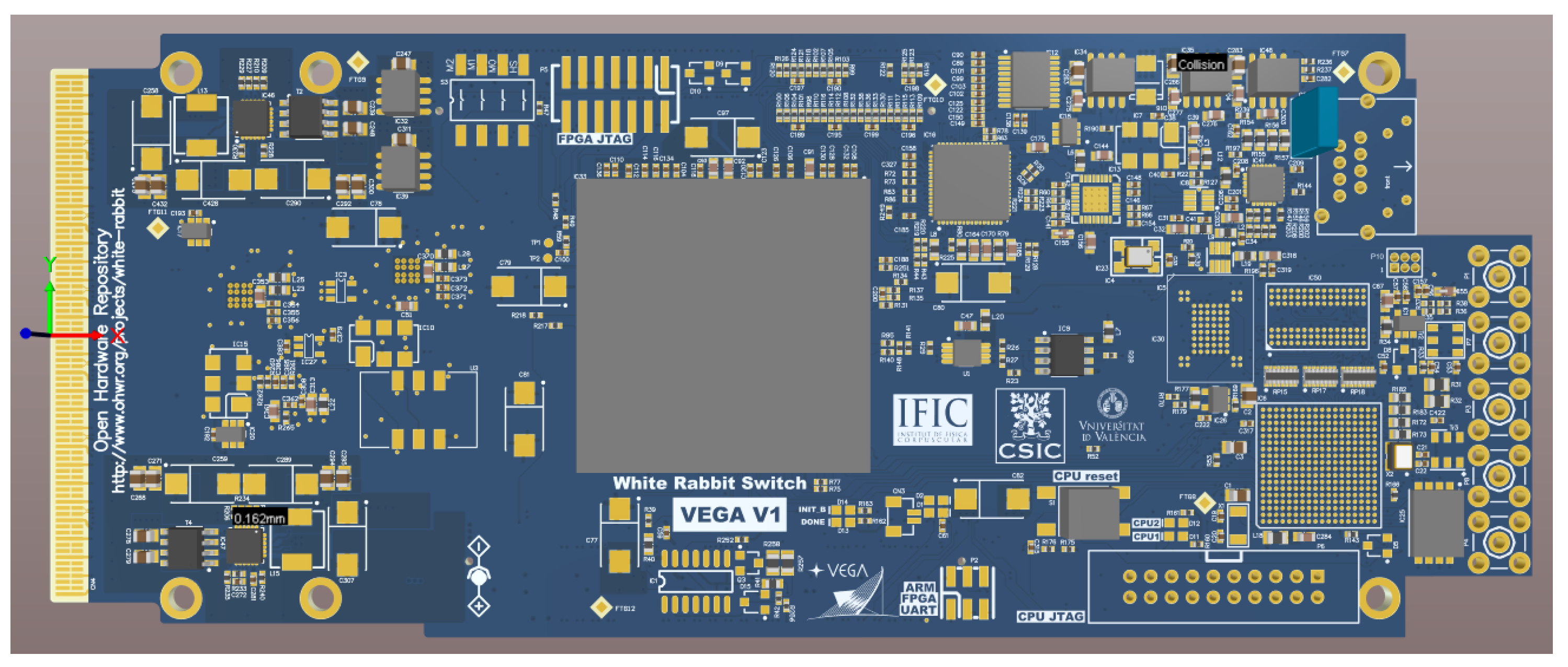

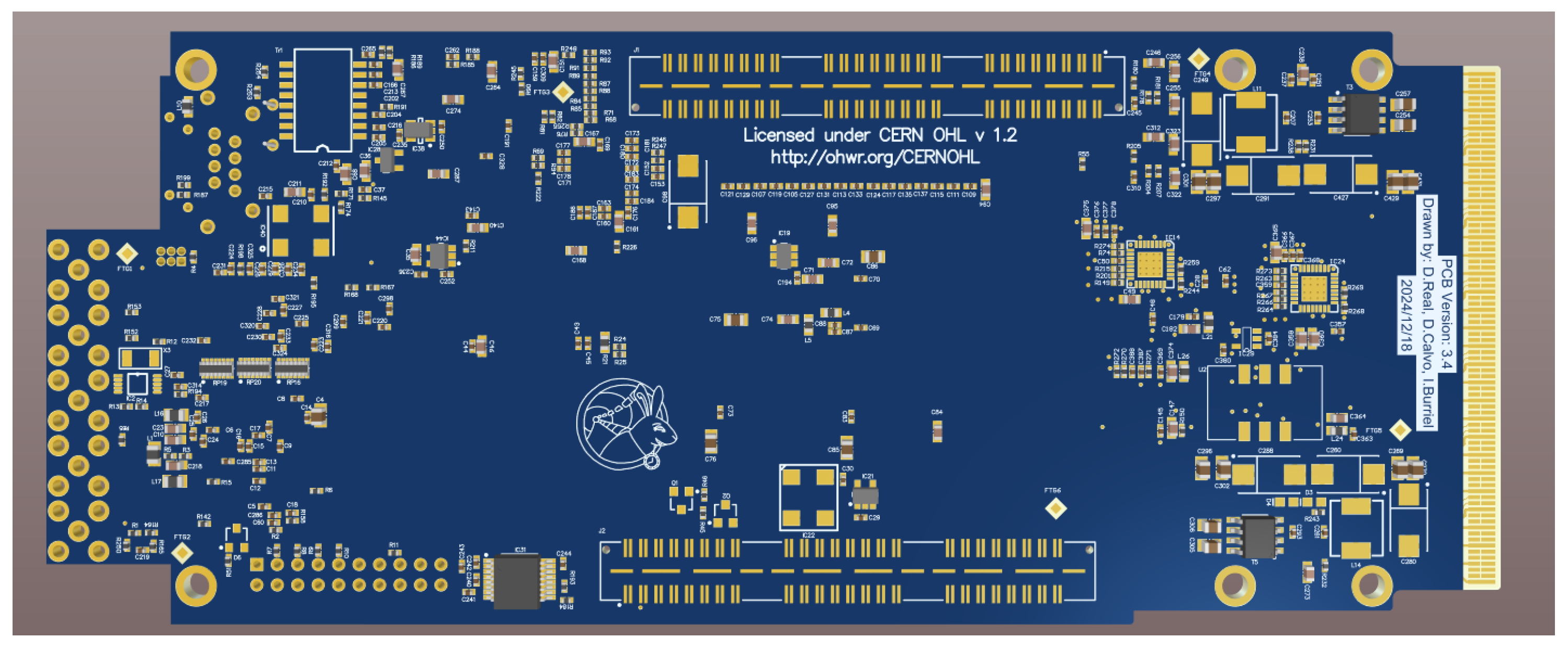

3. Improvements Proposed for Switching Core Board

3.1. Design Philosophy and Objectives

- A dual-clock architecture with independent primary and secondary subsystems.

- Dedicated power regulation and isolation for each subsystem to minimize noise coupling.

- Advanced filtering techniques to suppress high-frequency interference.

3.2. Redundant Clock Architecture

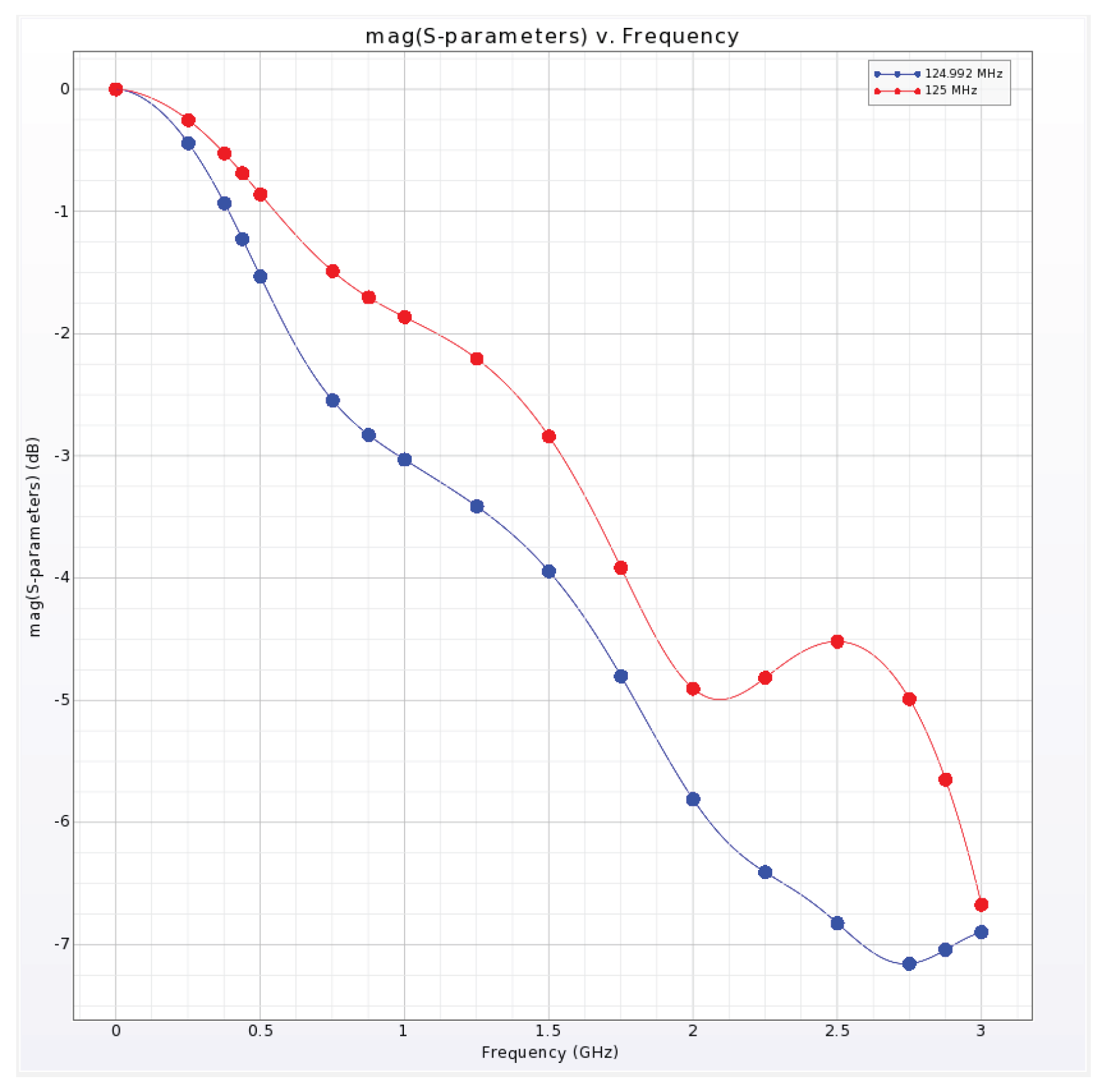

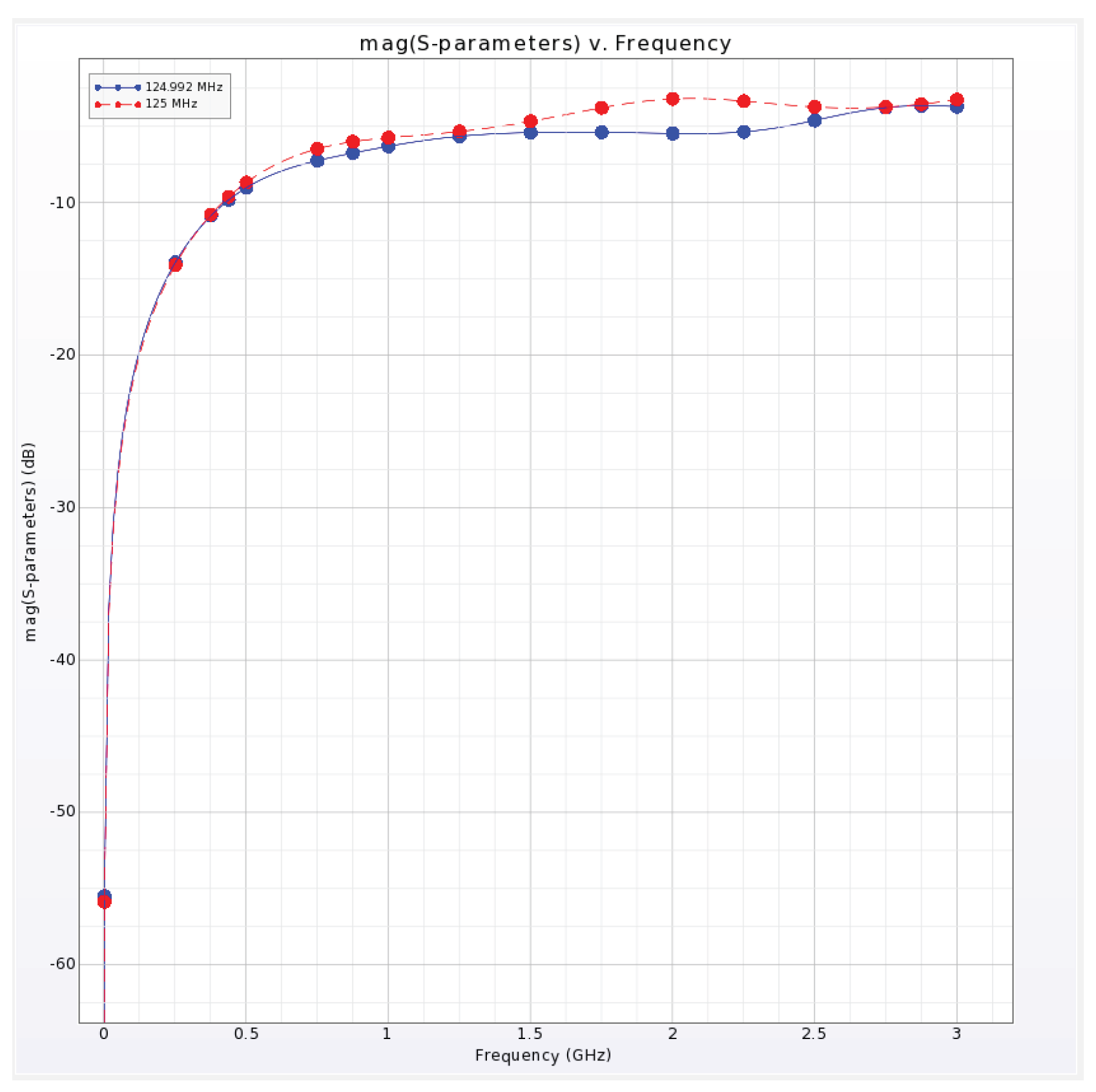

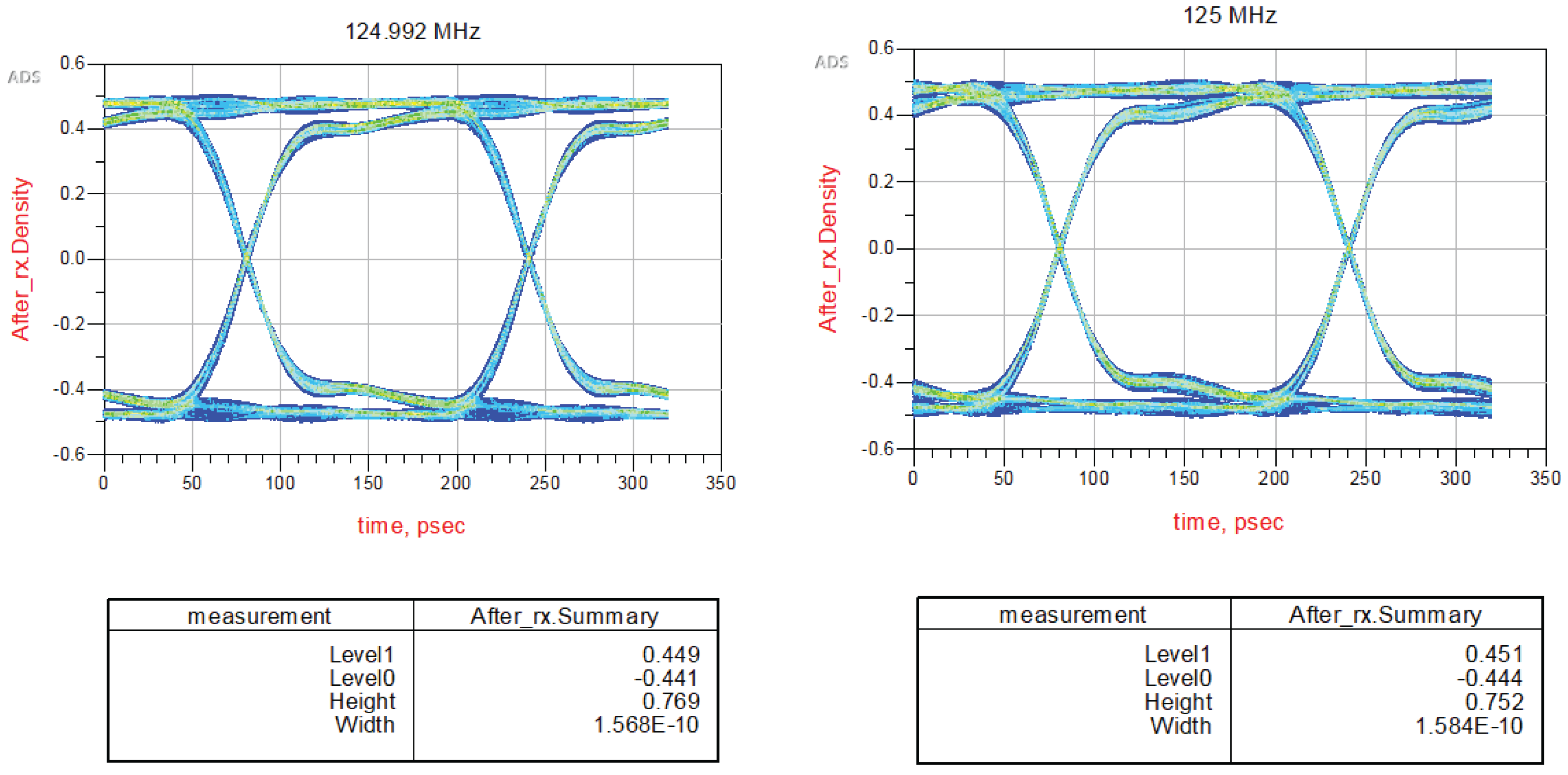

- Primary Clock Path: Based on high-stability crystal oscillators (CVPD-992), optimized for low phase noise and minimal jitter. These oscillators directly generate the 125 MHz and 124.992 MHz signals required for DDMTD measurements, eliminating intermediate frequency synthesis stages.

- Secondary Clock Path: Incorporates a voltage-controlled crystal oscillator (VCXO) combined with a clock synthesizer, providing dynamic frequency adjustment and compatibility with legacy designs.

3.2.1. Primary Clock System

3.2.2. Secondary Clock System

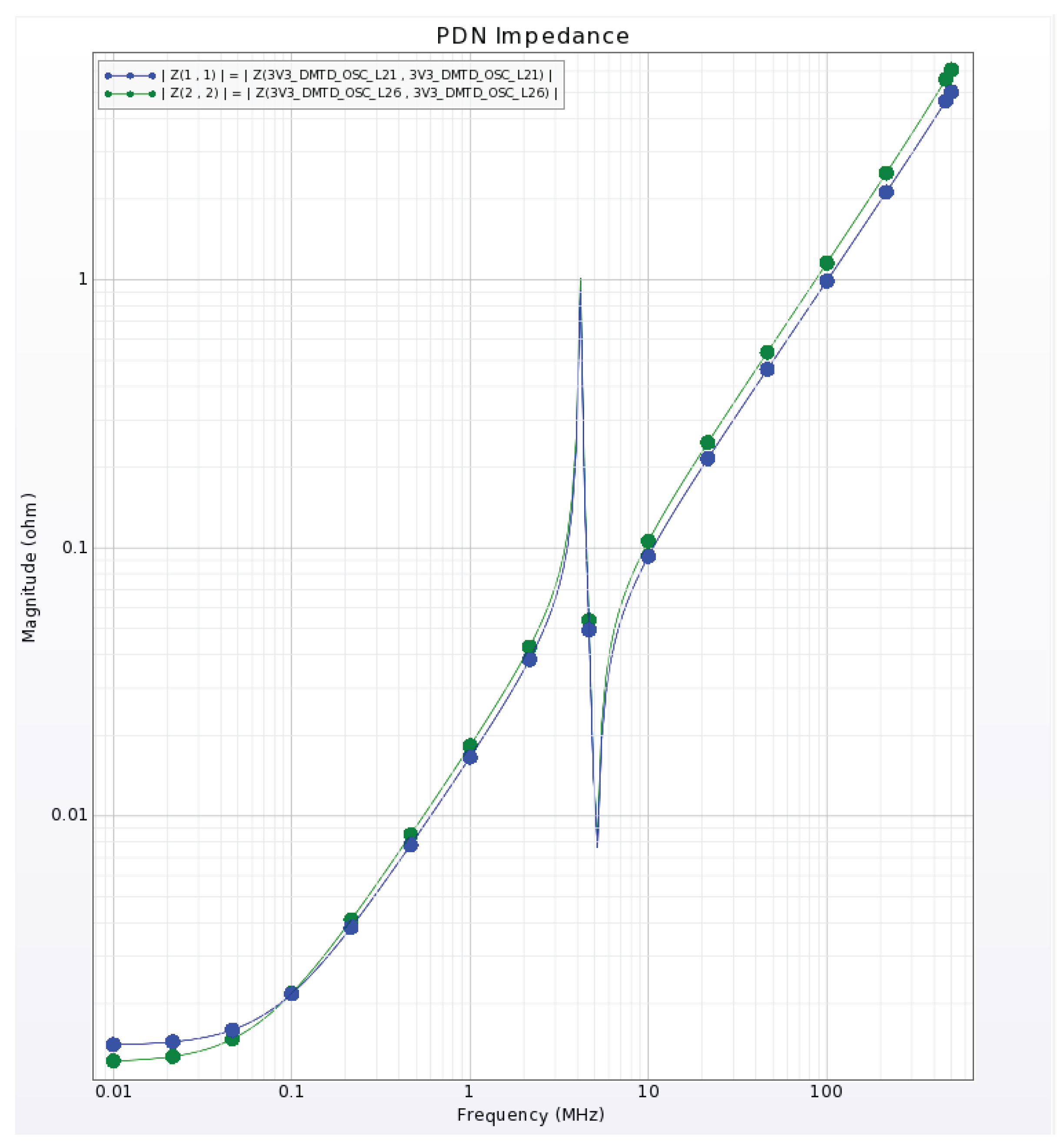

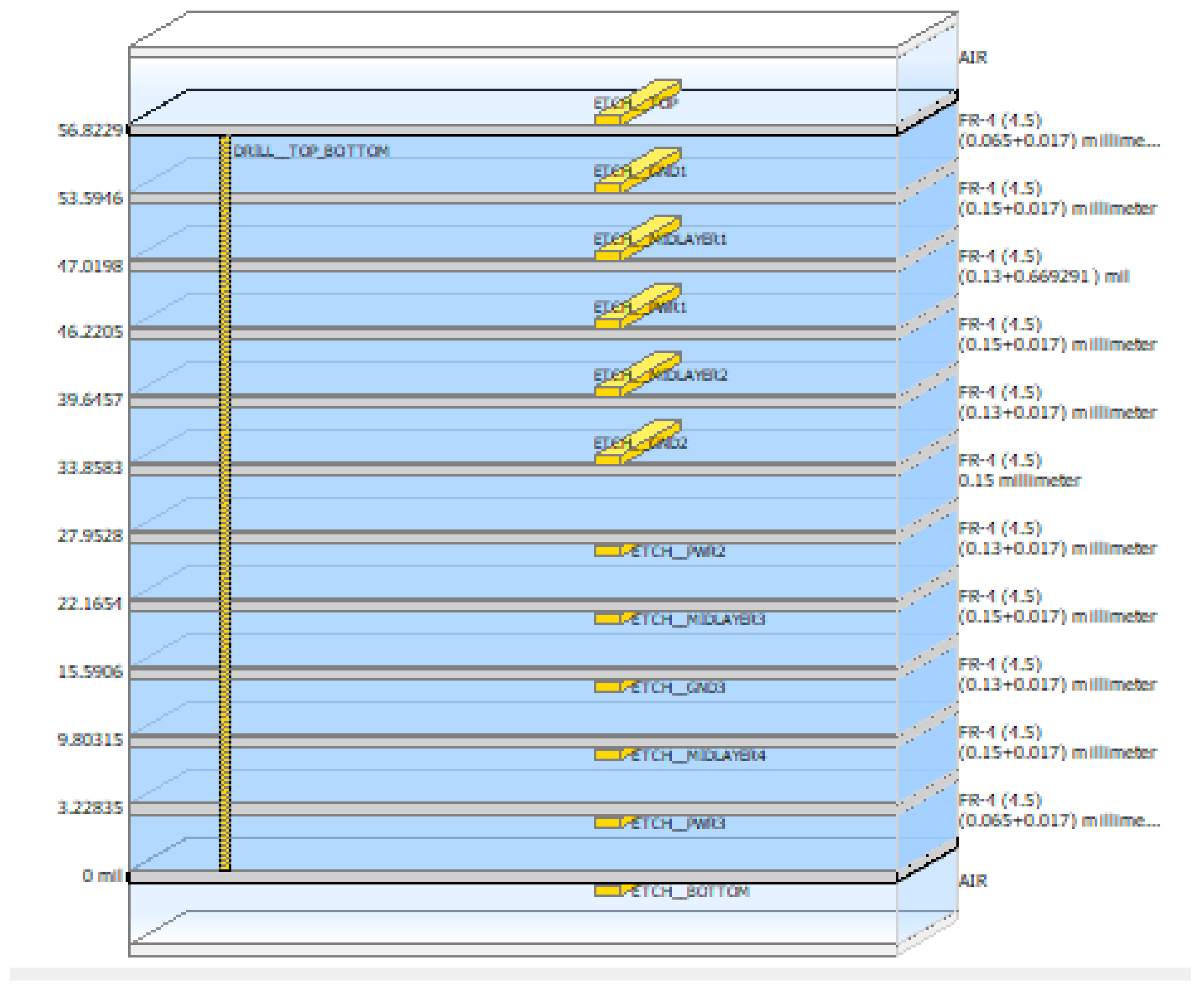

3.3. Power Integrity and Isolation

3.4. Noise Mitigation Strategies

3.5. Expected Advantages

- Improved Timing Accuracy: Direct generation of WR frequencies reduces phase noise and enhances DDMTD measurement precision.

- Enhanced Reliability: Redundant clock paths and automatic failover mechanisms eliminate single points of failure.

- Superior Power Integrity: Isolated regulators and advanced filtering minimize noise-induced jitter.

- Scalability and Compatibility: The design maintains full compatibility with existing WR infrastructure while providing a foundation for future upgrades.

4. Power and Signal Integrity Analysis

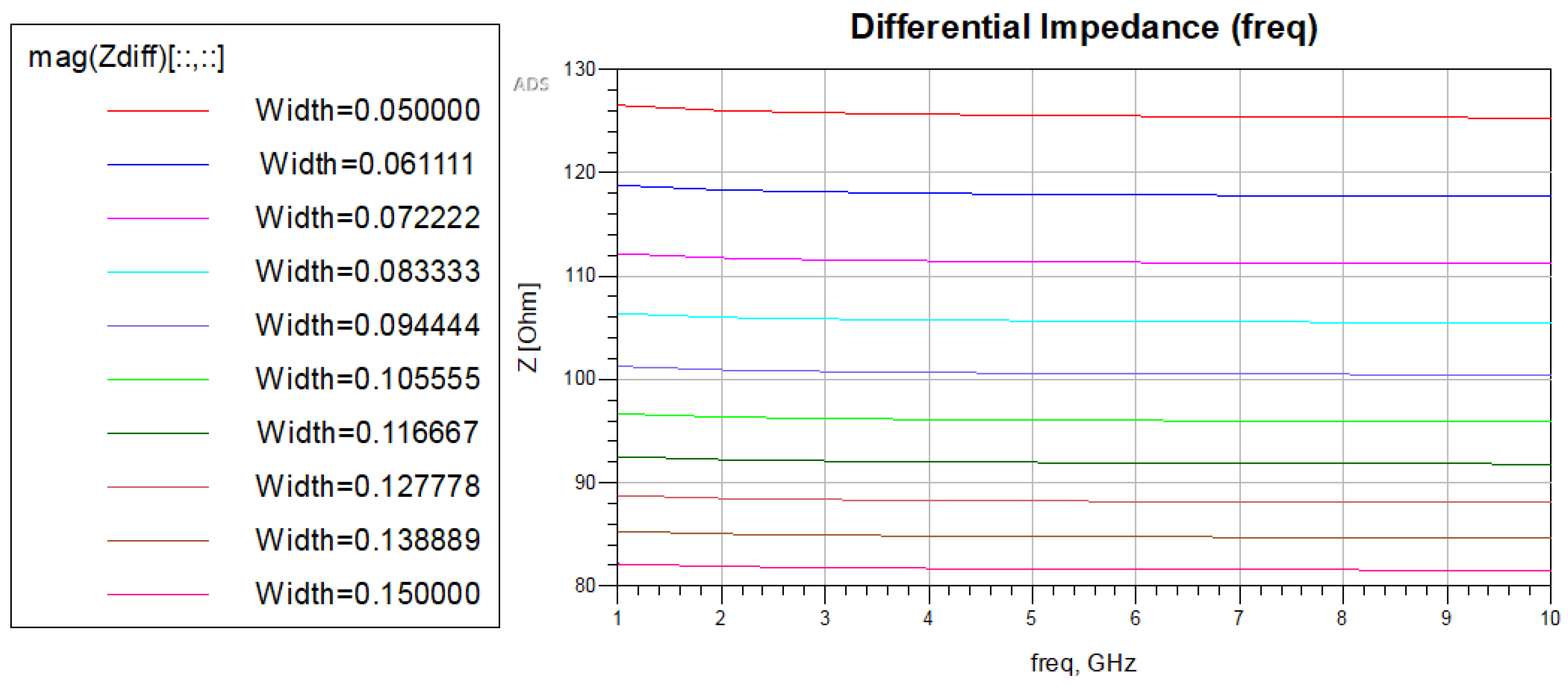

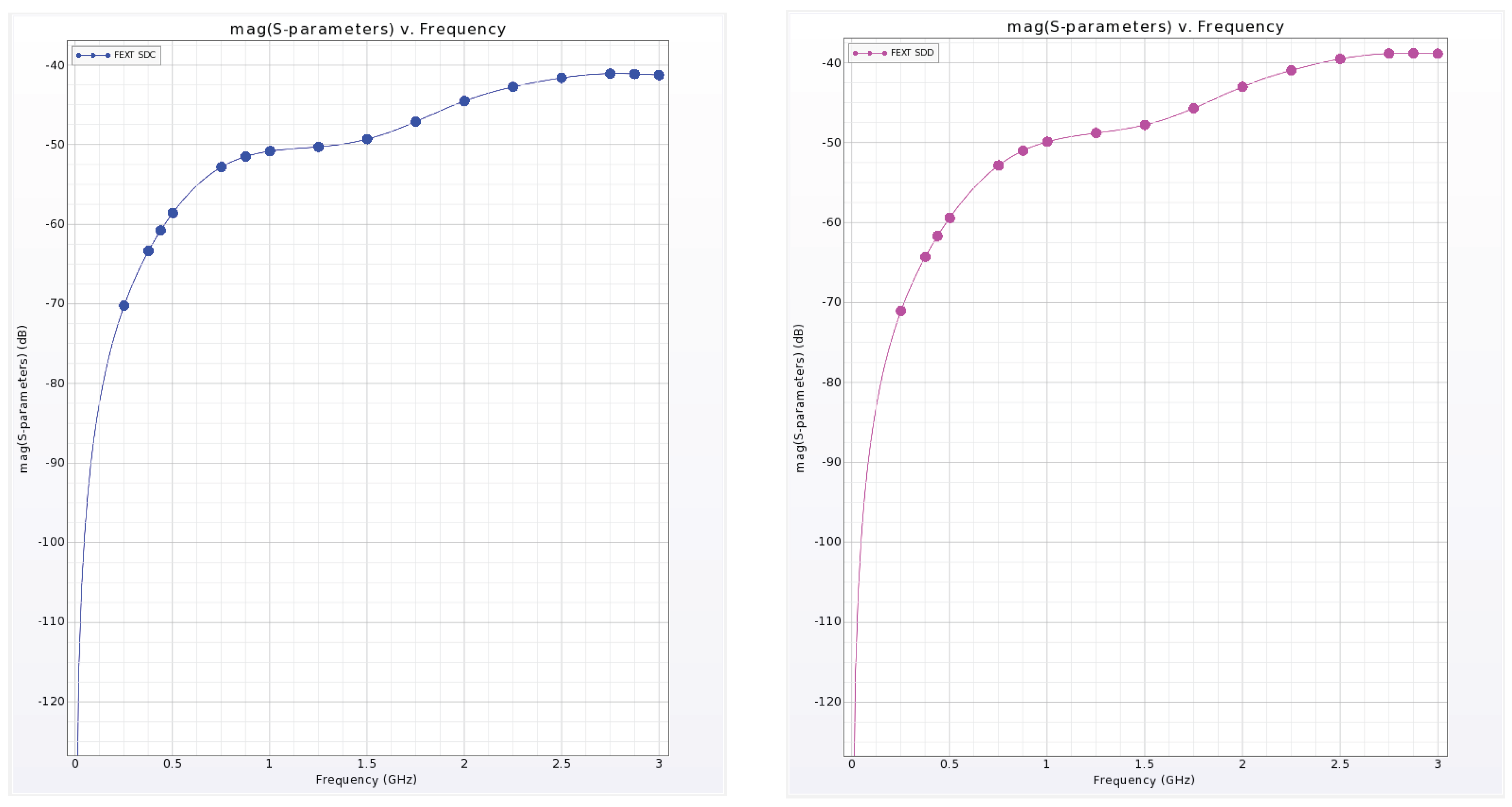

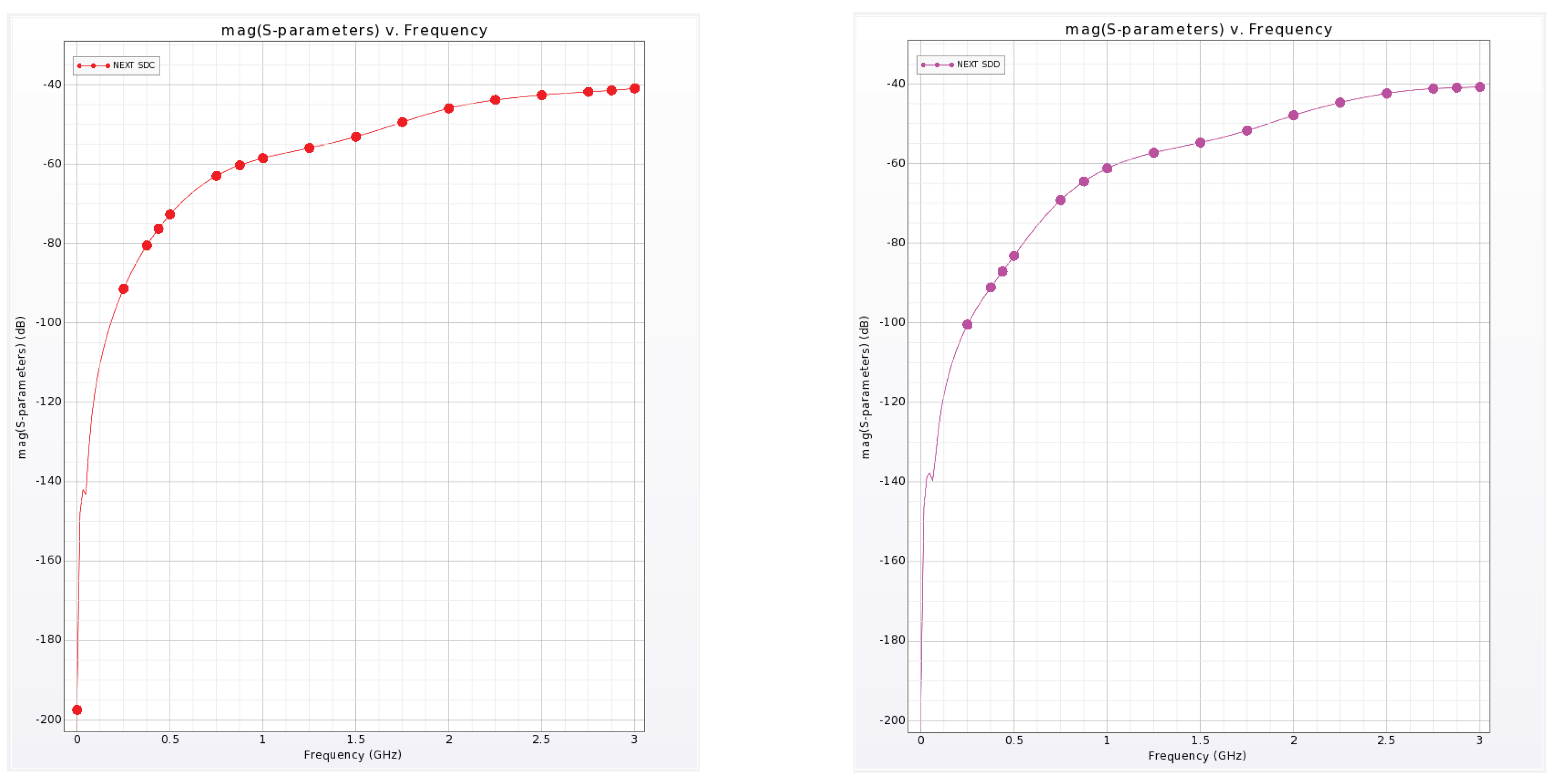

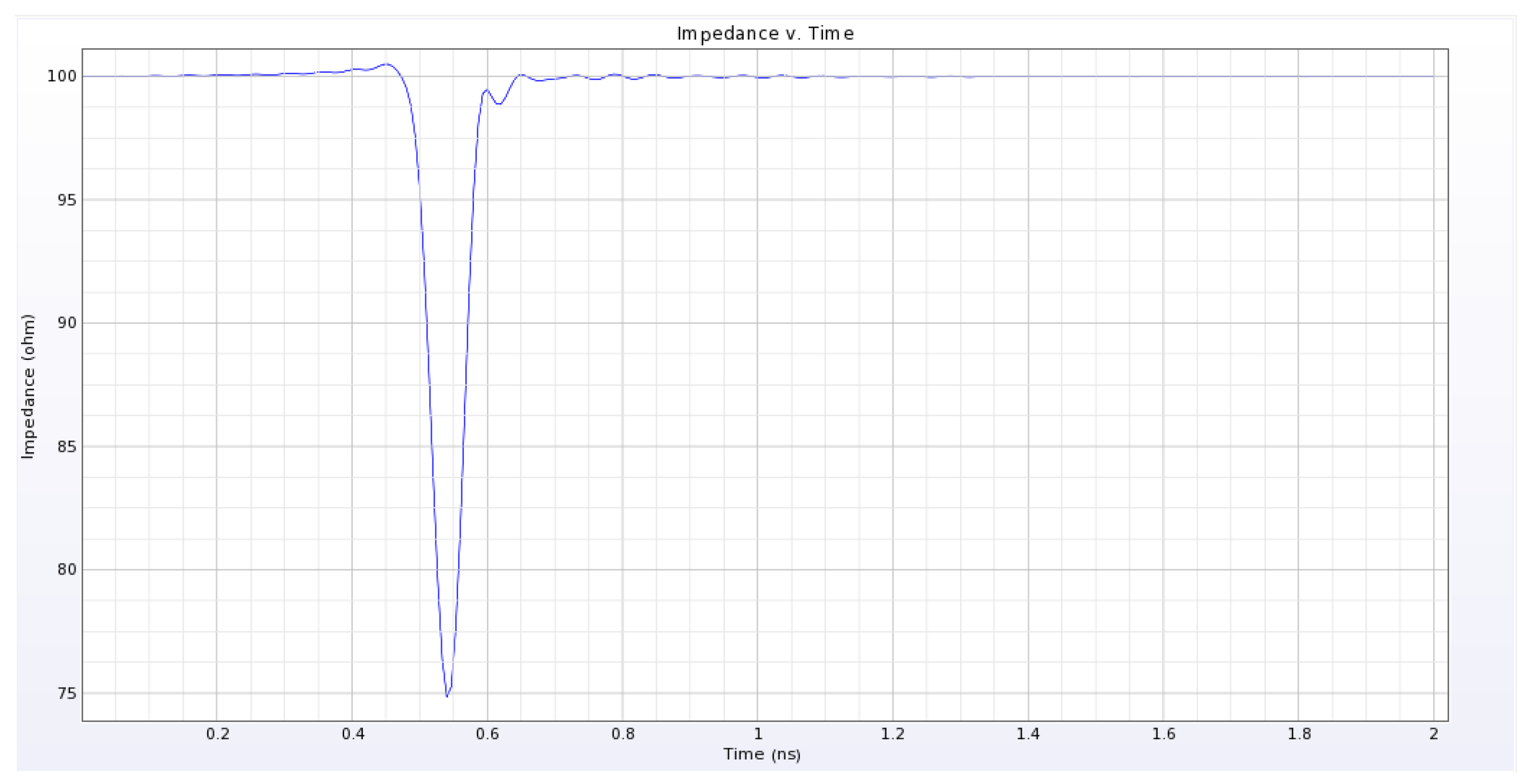

4.1. Prelayout Signal Integrity Simulations

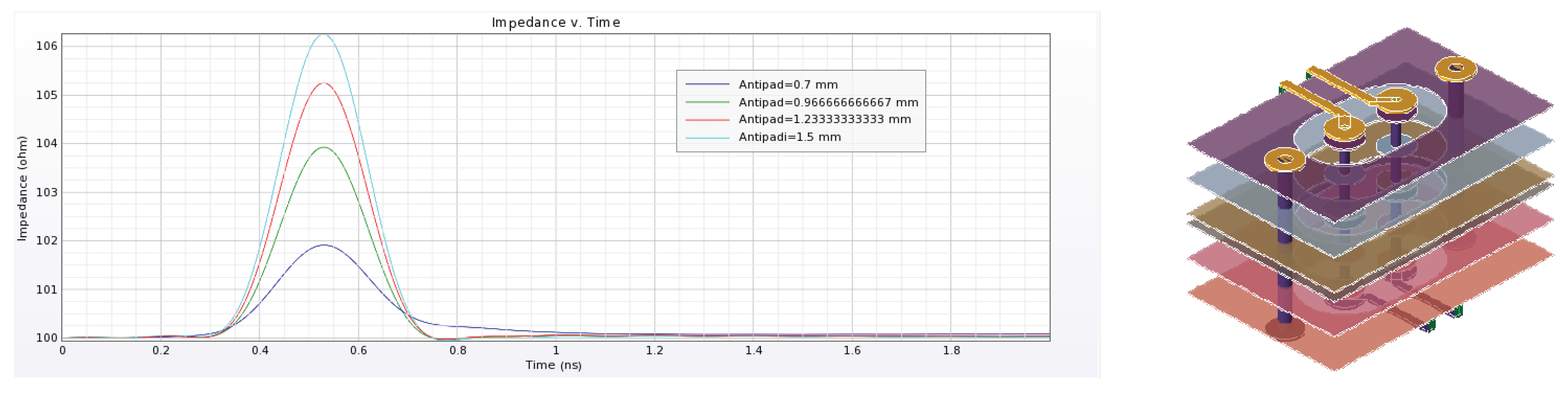

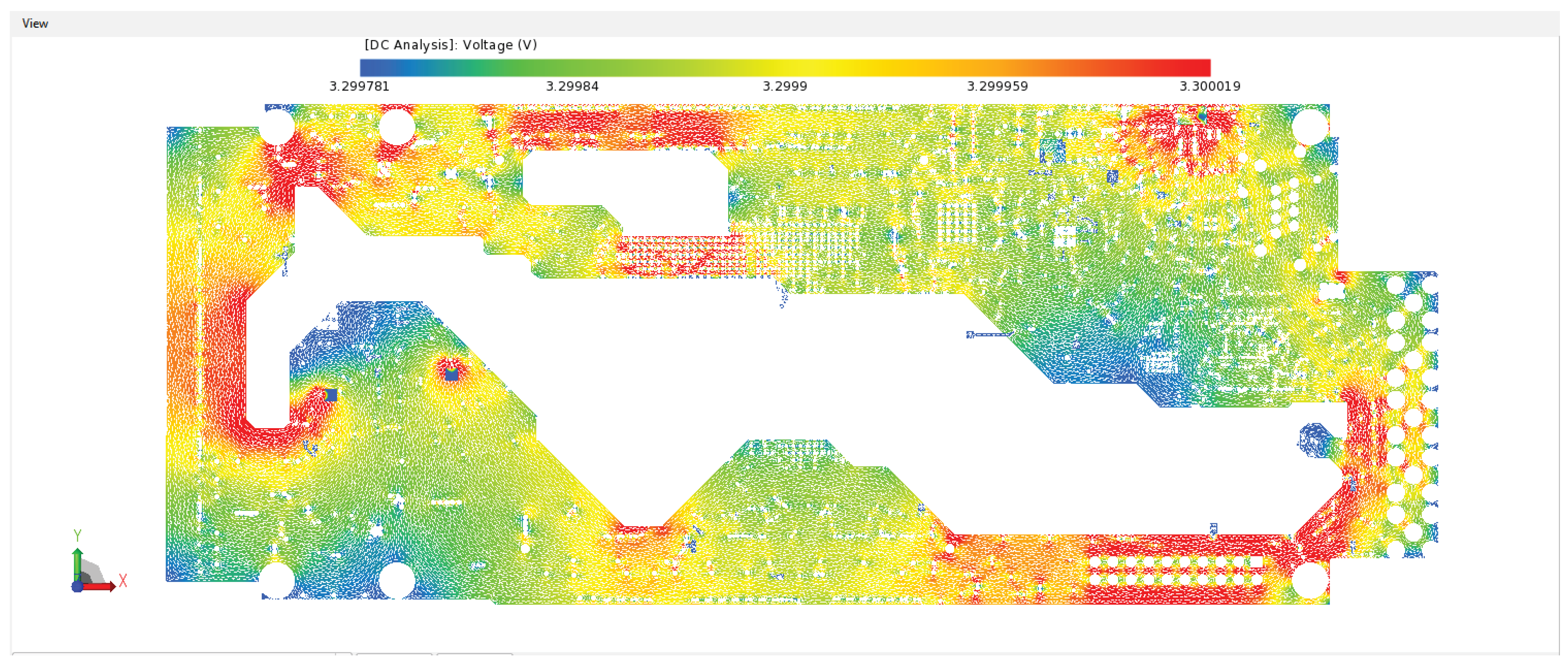

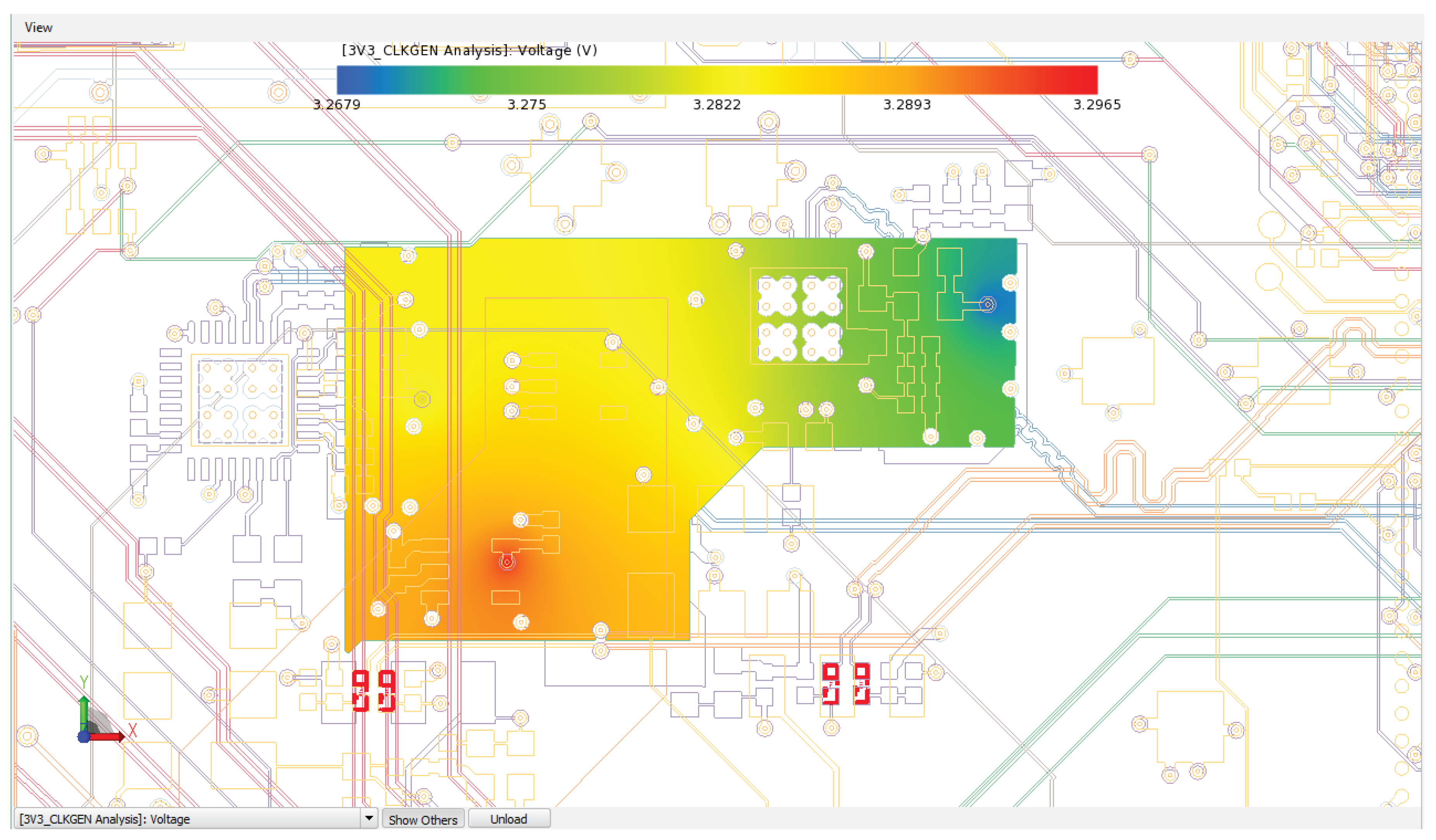

4.2. Postlayout Power and Signal Integrity Simulations

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Acknowledgments

References

- IEEE Std 1588-2019 (Revision ofIEEE Std 1588-2008); Synchronization Distribution in 5G Transport Networks. 2022.

- Venmani, D.; Lagadec, Y.; Lemoult, O.; Deletre, F. Phase and Time Synchronization for 5G C-RAN: Requirements, Design Challenges and Recent Advances in Standardization. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Industrial Networks and Intelligent Systems 2018, 5, 155238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, L.; Duan, R.; Garner, G.M. Analysis of the Synchronization Requirements of 5g and Corresponding Solutions. IEEE Communications Standards Magazine 2017, 1, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokui, R.; et al. Synchronization Requirements in 5G Massive MIMO Systems. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2019, 18, 3215–3228. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, S.; Yin, Z.; Naik, A.; Prabhakar, B.; Rosenblum, M.; Vahdat, A. Exploiting a Natural Network Effect for Scalable, Fine-grained Clock Synchronization. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stathakopoulou, C.; et al. Sync HotStuff: Blockchain Synchronization via Pipelined BFT. ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review 2022, 56, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ageron, M.; et al. ANTARES: the first undersea neutrino telescope. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 2011, arXiv:astro656, 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian-Martinez, S.; et al. Letter of intent for KM3NeT 2.0. J. Phys. G 2016, arXiv:astro43, 084001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aartsen, M.G.; et al. The IceCube Neutrino Observatory: Instrumentation and Online Systems. JINST 2017, arXiv:astro12, P03012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, E.; et al. The AMANDA neutrino telescope: Principle of operation and first results. Astropart. Phys. 2000, 13, 1–20, [astro-ph/9906203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyshkin, Y. Baikal-GVD neutrino telescope: Design reference 2022. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 2023, 1050, 168117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlin, M. Particle Physics with the Pierre Auger Observatory. SciPost Phys. Proc. 2022, arXiv:astro8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzian, Y.; Lazio, J. The Square Kilometre Array. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2006, 6267, 62672D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- as listed in the paper, A. Title of the paper from the PDF. EPJ Web of Conferences 2025, 302, 12011.

- Ferrini, F.; Wild, W. The Cherenkov Telescope Array Observatory Comes of Age. ESO Messenger 2020, 180, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, A.; et al. SKA Observatory Technical Report SKA-TRN-113; Timing and Synchronization Requirements for the SKA Phase 2. 2023.

- Alvarez, P.; et al. White Rabbit Deployment in CERN’s LHC Timing System. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2023, 70, 712–719. [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski, M.; Wlostowski, T.; Serrano, J.; Alvarez, P. White rabbit: a PTP application for robust sub-nanosecond synchronization 2011, 10, 25–30. [CrossRef]

- White Rabbit PTP Core. 28 02 2023. Available online: https://ohwr.org/projects/wr-cores/wiki/wrpc-core.

- Technology, M. MT-085: Ultra-Stable Oven-Controlled Oscillator, 2023. DS60001542B.

- Zhang, L.; et al. High-Speed PCB Design Techniques for Sub-Nanosecond Systems. IEEE Transactions on Electromagnetic Compatibility 2021, 63, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar]

- White Rabbit Collaboration. 28 02 2023. Available online: https://www.white-rabbit.tech/.

- Serrano, J.; et al. White Rabbit Project. Proceedings of ICALEPCS2009, Kobe, Japan, 2009; pp. 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski, M.; Wlostowski, T.; Serrano, J.; Alvarez, P. White rabbit: a PTP application for robust sub-nanosecond synchronization. 2011 IEEE International Symposium on Precision Clock Synchronization for Measurement, Control and Communication; 2011; pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE Std 1588-2008 (Revision of IEEE Std 1588-2002)2008; IEEE Standard for a Precision Clock Synchronization Protocol for Networked Measurement and Control Systems. pp. 1–269. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.K.; Chen, Y.S.; Hou, T.C.; Wu, B.L.; Chu, Y.S. Development Board Implementation and Chip Design of IEEE 1588 Clock Synchronization System Applied to Computer Networking. Electronics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timing characteristics of synchronous ethernet equipment slave clock. 2007.

- IEEE Standard for a Precision Clock Synchronization Protocol for Networked Measurement and Control Systems. IEEE Std 1588-2019 (Revision ofIEEE Std 1588-2008) 2020, 1–499. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, W.; Qi, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, G. An Enhanced Method for Nanosecond Time Synchronization in IEEE 1588 Precision Time Protocol. Processes 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielewicz, M.; Bancer, A.; Dziedzic, A.; Grzyb, J.; Jaworska, E.; Kasprowicz, G.; Kiecana, M.; Kolasinski, P.; Kuc, M.; Kuklewski, M.; et al. Practical Implementation of an Analogue and Digital Electronics System for a Modular Cosmic Ray Detector. Electronics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, S.; et al. KM3NeT front-end and readout electronics system: hardware, firmware and software. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2019, arXiv:astro5, 046001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella Wallbank, J.; Amodeo, M.; Beaumont, A.; Buzio, M.; Di Capua, V.; Grech, C.; Sammut, N.; Giloteaux, D. Development of a Real-Time Magnetic Field Measurement System for Synchrotron Control. Electronics 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Arnold, D.; Tuffner, F.; Cummings, R.; Lee, K. Recent Advances in Precision Clock Synchronization Protocols for Power Grid Control Systems. Energies 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabwani, M.; Suleymanov, M.; Pinhasi, Y.; Yahalom, A. Real-Time Fault Location Using the Retardation Method. Electronics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifandi, R.; Assagaf, S.; Ningtyas, Y.D.W.K. An Insight About GPS; 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Global positioning/GPS; 2009; pp. 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.; Alvarez, P.; Serrano, J.; Darwezeh, I.; Wlostowski, T. Digital dual mixer time difference for sub-nanosecond time synchronization in Ethernet. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium, 2010; pp. 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, W.; Hoover, S. White Rabbit Time Synchronization for Radiation Detector Readout Electronics. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2020, 68, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.M. Virtual prototyping and concurrent engineering in PCB manufacturing. IEEE Transactions on Electronics Packaging Manufacturing 1997, 20, 300–308. [Google Scholar]

- Zainudeen, P.B.; Althari, A.; Iqbal, M.T. A survey on virtual prototyping tools for PCB design. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Innovative Trends in Computer Engineering (ITCE), Aswan 2018; pp. 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, D.; Panicker, R. The use of virtual prototyping in PCB design. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Workshop Series on Advanced Materials and Processes for RF and THz Applications (IMWS-AMP), Suzhou, 2015; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Liu, K.S.; Huang, C.M. Virtual prototyping for signal integrity analysis of high-speed PCBs. IEEE Transactions on Electromagnetic Compatibility 2006, 48, 711–720. [Google Scholar]

- Silaghi, A.M.; Pescari, C.; Bleoju, C.; De Sabata, A. Solving Automotive Signal Integrity Issues by EMC Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 27th International Symposium for Design and Technology in Electronic Packaging (SIITME), 2021; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaghi, A.M.; Mueller, F.; De Sabata, A.; Buta, A.P.; Nicolae, P.M. Analysis of Shielding Effectiveness of an Automotive Display through Simulation and Testing. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility-EMC EUROPE. IEEE, 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Silaghi, A.M.; De Sabata, A. EMC Simulation of an Automotive Ethernet Interface. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Electronics and Telecommunications (ISETC), 2020; IEEE; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Behagi, A. RF and Microwave Circuit Design: A Design Approach Using (ADS); Advanced design system. Techno Search 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Behagi, A. 100 RF and Microwave Circuit Design: With Keysight (ADS) Solutions; Techno Search, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, H.; Graham, M. High-speed Digital Design: A Handbook of Black Magic; Prentice Hall Modern Semiconductor Design, Prentice Hall, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bogatin, E. Signal and Power Integrity–simplified; Prentice Hall PTR Signal Integrity Library, Prentice Hall, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mudavath, R.; Naik, B.R. Estimation of Far End Crosstalk and Near End Crosstalk Noise with Mutually Coupled RLC Interconnect Models. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), 2018; pp. 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).