1. Introduction

The rapid advancements in technology and medicine have significantly influenced the development of Implantable Medical Devices (IMDs), which have become essential for continuous health monitoring applications. IMDs, such as bioimplant sensors, provide real-time physiological data, enabling early detection of health deterioration and facilitating timely medical interventions. These devices are indispensable in applications ranging from cardiac and neural monitoring to gastrointestinal health tracking, playing a pivotal role in modern healthcare by improving patient outcomes and reducing hospitalization rates [

1,

2,

3].

Bioimplant sensors leverage wireless communication protocols to transmit physiological data, with Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) emerging as a popular choice due to its low power consumption, extended communication range, and seamless compatibility with consumer devices such as smartphones and tablets [

4]. BLE operates in the 2.4 GHz Industrial, Scientific, and Medical (ISM) band and employs Gaussian Frequency-Shift Keying (GFSK) modulation to transmit data efficiently. This technique shifts the signal frequency higher or lower to encode binary data, while Gaussian filtering reduces noise to improve signal integrity. BLE further enhances power efficiency through duty-cycling protocols, which turn off the device’s radio system at regular intervals to conserve energy [

5].

Despite its advantages, BLE’s reliance on duty cycling poses significant challenges in IMDs. While the protocol conserves energy, it introduces idle listening and false wake-ups, increasing power consumption and communication latency. This limitation is particularly problematic for bioimplant sensors, where prolonged battery life is critical due to the difficulty of recharging or replacing batteries in invasive devices [

6]. Moreover, BLE’s periodic wake-ups to broadcast advertisement packets, even in the absence of a connection request, contribute to further energy consumption [

7].

Recent research has highlighted the potential of integrating Wake-Up Radios (WuRs) with BLE to address these challenges. WuRs are ultra-low-power auxiliary radios designed to activate the primary communication module only when specific events or thresholds are detected, significantly reducing idle listening and false wake-ups [

8]. By combining WuRs with BLE, bioimplant sensors could achieve greater energy efficiency and reduced latency, making them more suitable for long-term monitoring applications such as cardiac and neural activity tracking [

9].

Existing studies have primarily focused on utilizing BLE’s duty-cycling mechanisms in medical IoT applications, yet issues such as high data latency and inefficient energy usage persist in scenarios requiring aperiodic transmissions [

8]. Furthermore, there is a lack of comprehensive evaluations comparing standalone BLE, always-on WuR-enabled BLE, and duty-cycled WuR-integrated BLE configurations. Addressing these gaps is essential to advance the design and implementation of energy-efficient IMDs capable of delivering reliable, low-latency performance over extended periods.

This paper seeks to explore the potential of WuR technology in addressing the energy and latency challenges associated with BLE-enabled bioimplant sensors. By leveraging software modeling techniques and simulations, this work aims to evaluate the performance of various configurations and provide insights into the most effective strategies for optimizing power consumption and communication efficiency in IMDs.

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on BLE duty-cycling mechanisms and WuR technology in medical IoT applications.

Section 3 provides an overview to the BLE protocol stack.

Section 4 outlines the simulation setup, including system configurations and evaluation metrics.

Section 5 presents the results and discusses the performance of BLE and WuR-integrated configurations. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the study, summarizing key findings and their implications for BLE-enabled bioimplant sensors.

2. Related Work

Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) has become a widely adopted communication protocol for bioimplant sensors due to its low power consumption and seamless compatibility with consumer devices. For example, BLE has been implemented in various medical applications such as electromyographic sensors [

10], neural implant sensors [

11], and glucose monitoring sensors [

12]. However, its high energy consumption in certain scenarios limits its efficiency for energy-constrained implantable devices. For instance, commercially available BLE chips consume approximately 10 nJ/bit, making them unsuitable for applications like neural implants with strict power constraints [

13]. Similarly, Yogev et. al. [

14] argue that off-the-shelf and standardized protocols such as Bluetooth Low Energy can be implemented in implant designs, but they come with two drawbacks: mW-level power consumption and their generalized nature.

While BLE provides user-friendly integration, many utilizations lack power management strategies. For example, a BLE-enabled implant was designed for MRI heating experiments but did not address power optimization [

15]. Another study proposed BLE-based bidirectional communication between implants and a central device, enabling reliable connections between multiple devices, but failed to provide specific methods for reducing power consumption [

16]. Similarly, BLE technology was used to design an implantable, wireless, and battery-less bladder pressure monitoring system. To reduce power consumed by the BLE transceiver, the device was configured to transmit data every two seconds, considering bladder pressure as a slow-changing signal. However, periodic transmissions every two seconds can still lead to unnecessary energy usage, as bladder pressure may not change significantly during this interval [

17].

To address BLE's power inefficiencies, various techniques have been proposed. Single Sideband (SSB) BLE backscatter communication was introduced to reduce power consumption by avoiding the need to generate and amplify a carrier wave [

13]. This approach was later improved with an all-digital design using an inductor-free capacitance modulator, achieving further energy savings [

18]. Similarly, BLE was integrated into a compact base station system for biomedical implants, utilizing short bursts of data transfer to optimize battery usage. These strategies demonstrate the potential of tailored BLE implementations to enhance energy efficiency and extend device lifespan [

19].

Wake-Up Radios (WuRs) have emerged as a promising solution to improve energy efficiency in wireless networks, including Wireless Body Area Networks (WBANs) and Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs). WuRs reduce idle listening and unnecessary wake-ups, allowing devices to remain in low-power mode until triggered by a wake-up signal [

20]. This approach has been shown to be particularly effective in scenarios with infrequent communication events, significantly reducing energy consumption compared to traditional duty cycling. For example, energy harvesting and a radio-triggered wake-up circuit were employed for a glucose monitoring system, enabling efficient power management by activating the sensor only when necessary [

21].

Integrating WuRs with BLE has been demonstrated to reduce latency and improve energy efficiency, provided data delivery latency remains below 2.1 seconds and wake-up requests are not excessive [

22]. Similarly, incorporating WuRs into the BLE protocol stack for beacon scenarios was shown to achieve up to a 30% increase in energy efficiency [

23]. These studies highlight the potential of hardware WuRs to enhance power efficiency and reduce latency in wireless medical applications.

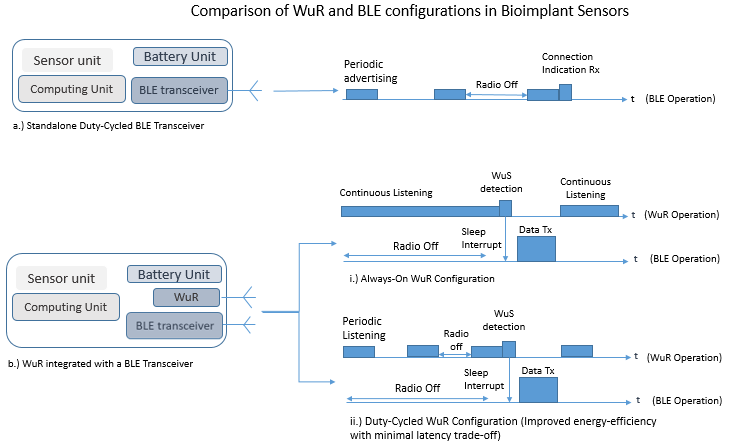

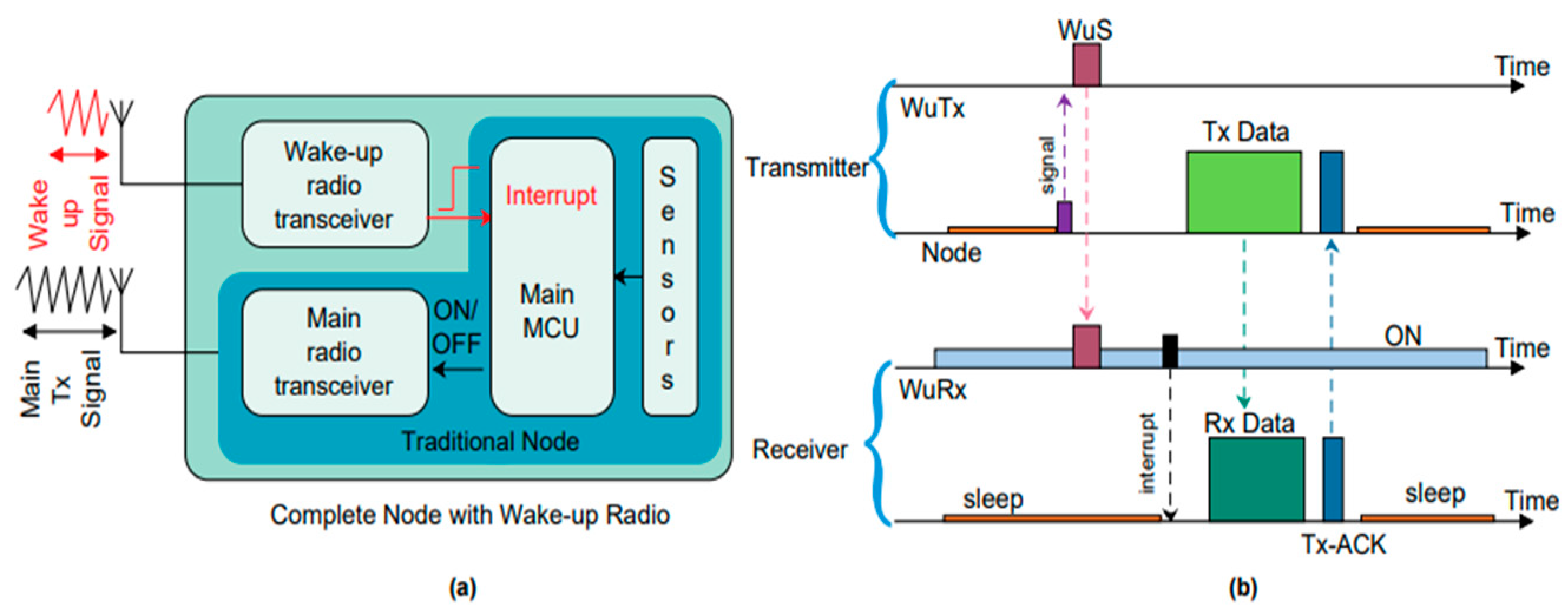

Figure 1 describes the general architecture of wake-up radios and the deployment of a wake-up signal (WuS) to trigger the receiver. The wake-up transmitter (WuTx) signals the wake-up receiver (WuRx) to interrupt the sleep time of the receiving device in order to exchange data.

Despite advancements in BLE technology, its energy efficiency in bioimplant sensors remains a critical challenge. Many existing Medium Access Control (MAC) protocols are tailored for general-purpose WSNs or BSNs but lack the specificity needed for bioimplant devices with unique energy constraints [

14,

24,

25]. While WuRs have been explored in wearable health monitoring devices [

20,

22], their application in bioimplant sensors remains under-researched.

This research aims to address these challenges by investigating the integration of a Wake-Up Radio (WuR) with Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) technology for bioimplant sensors. The proposed approach focuses on optimizing energy consumption by leveraging the WuR to minimize BLE's active duty cycles while maintaining reliable communication. By simulating various configurations, this study evaluates the energy efficiency trade-offs and highlights the potential of WuR-integrated BLE systems to extend the operational lifespan of bioimplant sensors, making them more viable for long-term medical applications.

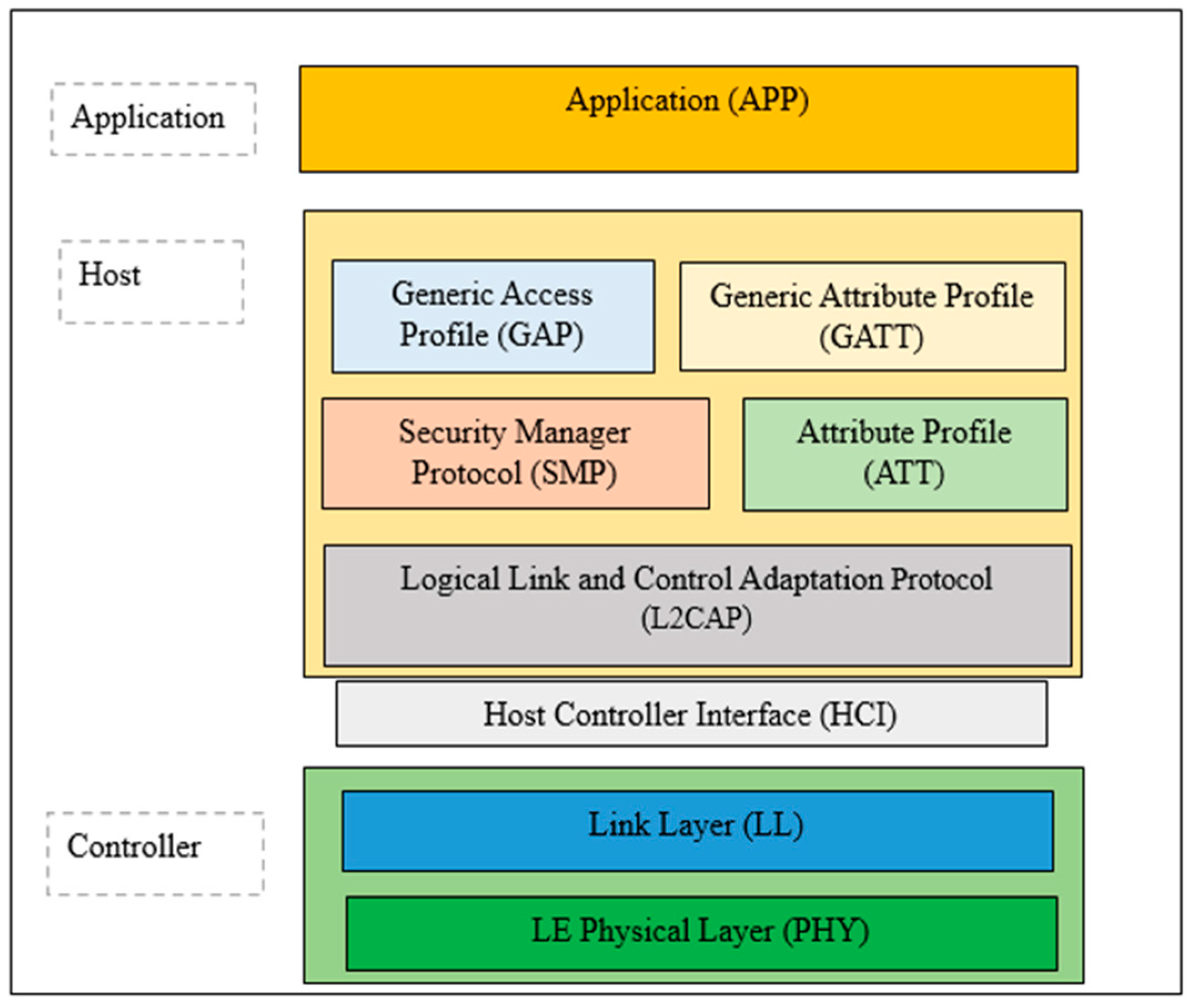

3. BLE Protocol Stack Overview

The Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) protocol stack is organized into three main layers: the application, host and controller, each containing specific components responsible for communication and device operations.

Application Layer (APP)

The Application layer implements the application logic, providing the user interface and interfacing with lower layers of the BLE stack.

Host Layer

The Host layer manages upper layer operations and communicates with the Controller via the Host-Controller Interface (HCI). It includes several protocols:

Generic Access Profile (GAP): Defines device roles (central, peripheral), manages device discovery, connection establishment, and data channels.

-

Generic Attribute Profile (GATT): Manages services, characteristics, and descriptors. GATT defines:

GATT Services: Represent specific functionality (e.g., Heart Rate Service, Battery Service).

GATT Characteristics: Represent actual data (e.g., heart rate, battery level), each identified by a unique UUID.

GATT Descriptors: Provide metadata about characteristics, such as properties or presentation format.

Attribute Protocol (ATT): Facilitates the transport of GATT attributes, organizing data into Attribute Protocol Data Units (PDU).

Logical Link Control and Adaptation Protocol (L2CAP): Ensures logical connections, handles fragmentation, multiplexing, error handling, and retransmissions.

Controller Layer

The Controller layer consists of two components that manage lower-level operations through HCI:

-

Link Layer (LL): Defines multiple device states, including:

Standby State: The device is not transmitting or receiving, conserving power.

Advertisement State: The device broadcasts advertisement packets to signal its presence.

Scanning State: The device listens for advertisements from other devices.

Initiation State: The central device attempts to establish a connection with a peripheral device.

Connection State: A successful connection is established, allowing data exchange.

LE PHY: Responsible for the physical transmission of data, operating within the 2.400 to 2.4835 GHz frequency range. It utilizes 40 channels with 2 MHz spacing, where channels 0–36 are data channels, and channels 37–39 are reserved for advertising. The Bluetooth 5.0 standard introduces the LE 2M PHY, which allows for a maximum data rate of 2 Mbps, effectively doubling the throughput compared to the previous 1 Mbps rate supported by the LE 1M PHY.

4. Simulation Setup

This section outlines the simulation setup and methodology used to evaluate the energy efficiency of three BLE bioimplant sensor configurations: a standalone duty-cycled BLE sensor, an always-on WuR-enabled BLE sensor, and a duty-cycled WuR-enabled BLE sensor. Key simulation components, such as reconnection handling, packet analysis, and wake-up signal mechanisms, were incorporated to ensure accuracy and relevance. Power consumption models were developed for each configuration, enabling a comparative analysis of cumulative energy usage and operational efficiency.

4.1. General Simulation Tools and Methodology

MATLAB’s computational capabilities, user-friendly interface, and extensive library of functions were essential for simulating complex systems. MATLAB R2019b was selected due to its support for Bluetooth protocol simulation via the Communications Toolbox™ Library for the Bluetooth® Protocol, which provides standardized tools for evaluating BLE communication systems [

26]. The three setups simulate the behavior of a BLE heart rate sensor (acting as the GATT Server) communicating with a central device (GATT Client).

The simulation evaluated three configurations:

BLE standalone bioimplant sensor with a duty cycling MAC protocol.

BLE standalone bioimplant sensor enhanced with a Wake-Up Radio (WuR).

BLE bioimplant sensor integrated with a duty-cycled WuR.

The power consumption models align with established findings that energy usage in BLE is directly proportional to data length

and the number of communication channels

, while inversely proportional to the communication interval

[

27]. By leveraging these relationships, the simulation accurately reflects real-world behavior, providing actionable for optimizing BLE-enabled bioimplant sensors.

In this study, the WuR functionality is modeled probabilistically, detecting Wake-Up Signals (WuS) that trigger the activation of a simulated bioimplant radio transceiver. Two modes were considered: Always Active WuR and Duty-Cycled WuR. Power specifications from the AS3930 demo kit and the DA14582 BLE module were used to parameterize the models.

The simulation system incorporates several generalized techniques to improve the accuracy and depth of the analysis across all configurations. One key aspect is reconnection handling, where the system is designed to replicate real-world scenarios in which a device might disconnect and require reconnection. To optimize this process, cached service and characteristic data are utilized, but only for bonded or paired devices that have established a trusted relationship [

28]. This caching mechanism eliminates the need for redundant discovery processes during reconnections, thereby significantly reducing both latency and power consumption.

The system also incorporates logging and packet analysis to capture all interactions, state transitions, and packet transmissions. State log files record system behavior, while transmitted packets are saved in PCAP files. Together, these files form the basis for detailed energy consumption analysis, offering insights into Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) communication patterns and enabling precise validation of power consumption metrics. This approach ensures the simulation results are both reliable and reflective of real-world conditions.

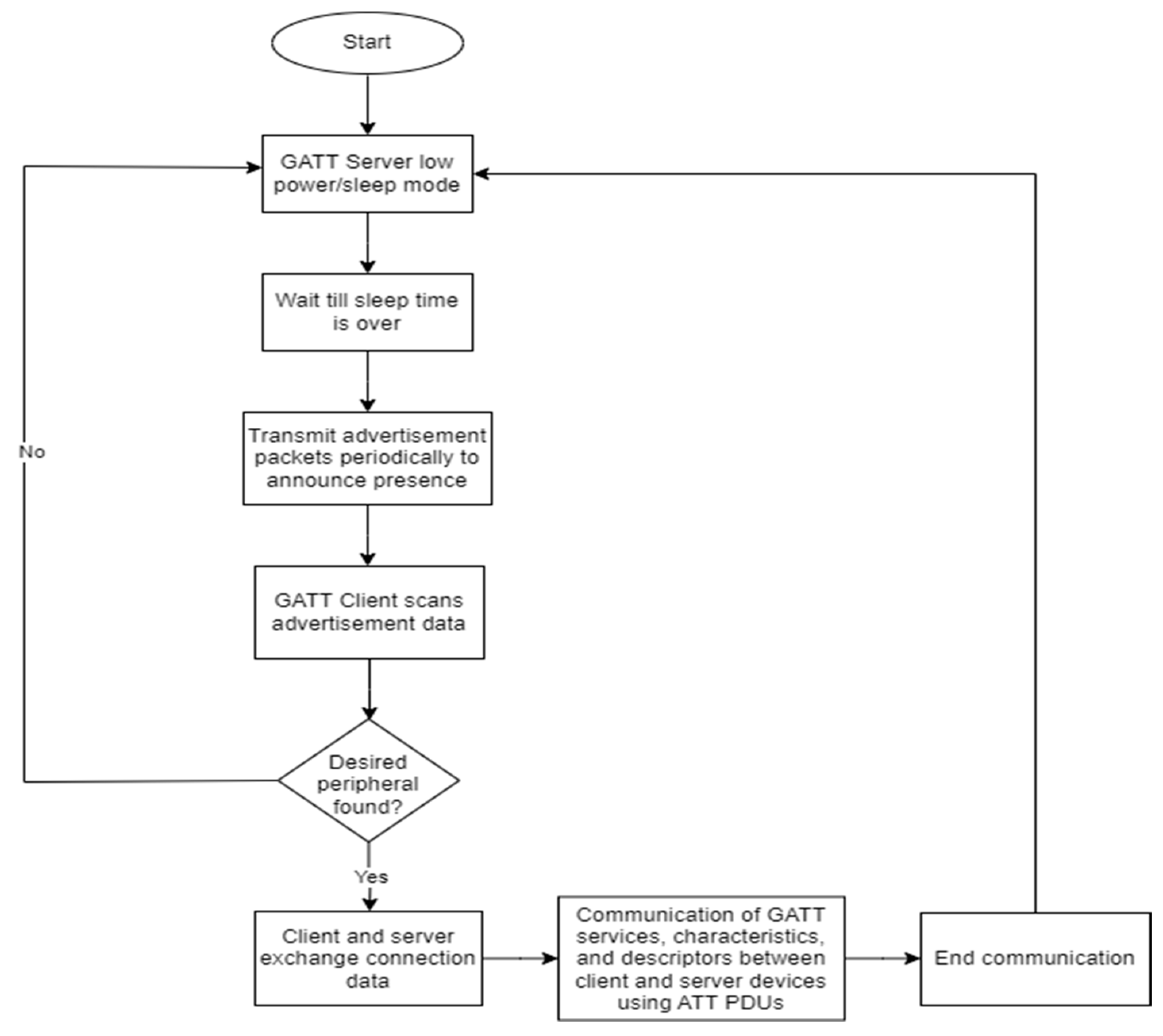

4.2. System Setup: BLE Standalone Sensor with Duty Cycling

This scenario focuses on simulating a BLE standalone bioimplant sensor utilizing a duty-cycling mechanism to optimize power consumption. Duty-cycling alternates the sensor's operation between active communication and low-power sleep modes, conserving energy while maintaining communication efficiency.

Table 1.

BLE Standalone Sensor Parameters.

Table 1.

BLE Standalone Sensor Parameters.

| Parameters |

Value |

Description |

| TX Current |

3.4mA |

Current consumption during transmission. |

| RX Current |

3.1mA |

Current consumption during reception. |

| Sleep Current |

1.5µA |

Current consumption during sleep mode. |

| Operational Voltage |

3V |

Voltage supplied to the BLE module. |

| Heart Rate Threshold |

140bpm |

Threshold for heart rate events triggering transmissions. |

| Advertising Interval |

1.285s |

Time between successive advertisement events. |

| Advertising Duration |

10s |

Duration of active advertising in each duty cycle. |

| Sleep Duration |

10s |

Duration of sleep phase in each duty cycle. |

| Data Channels (Used) |

[0, 4, 12, 16, 20, 24, 25] |

Channels specified in the CONNECT_IND PDU for communication. |

| Connection Chance |

10% |

Probability that a client connects during an advertisement. |

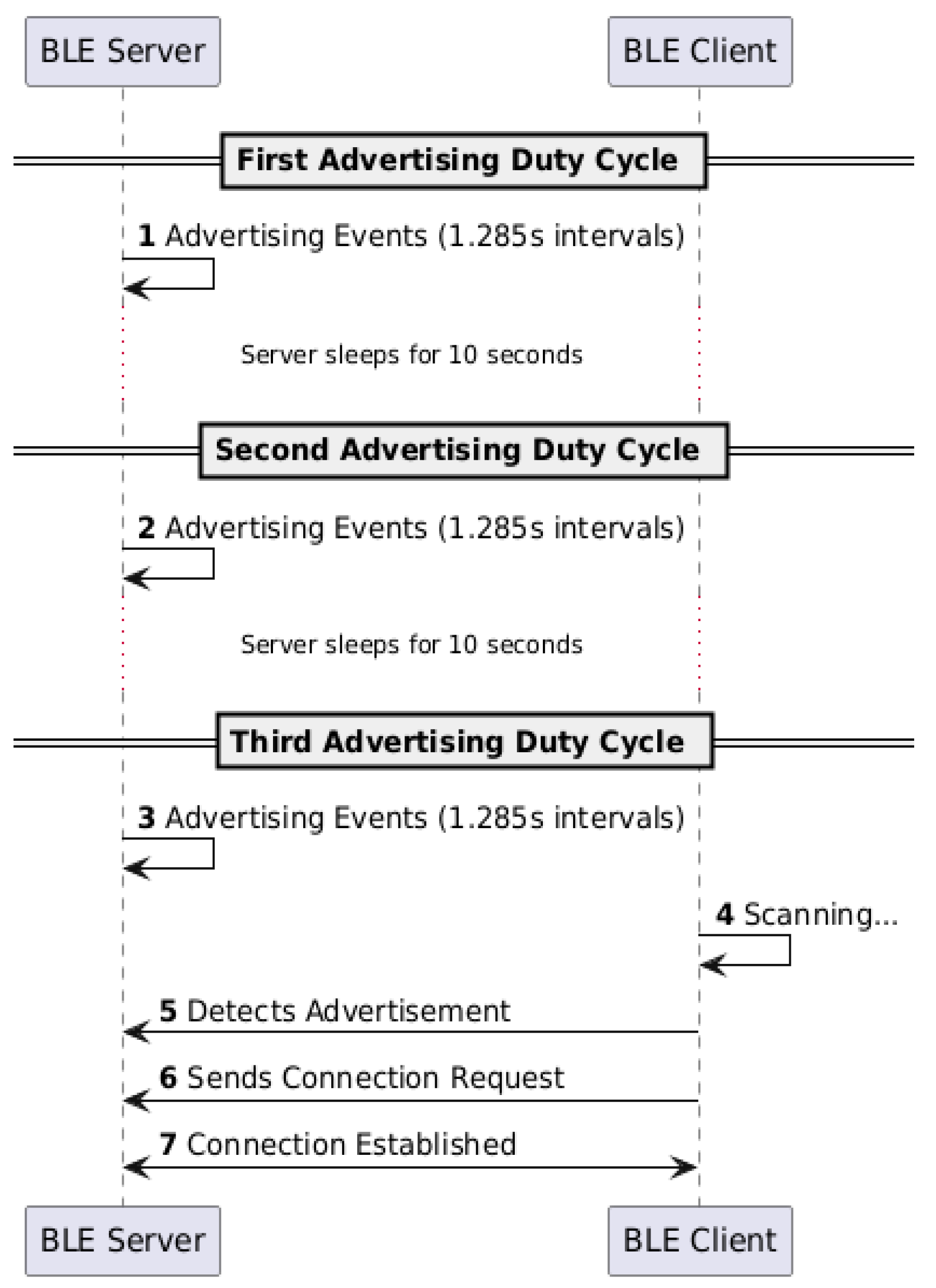

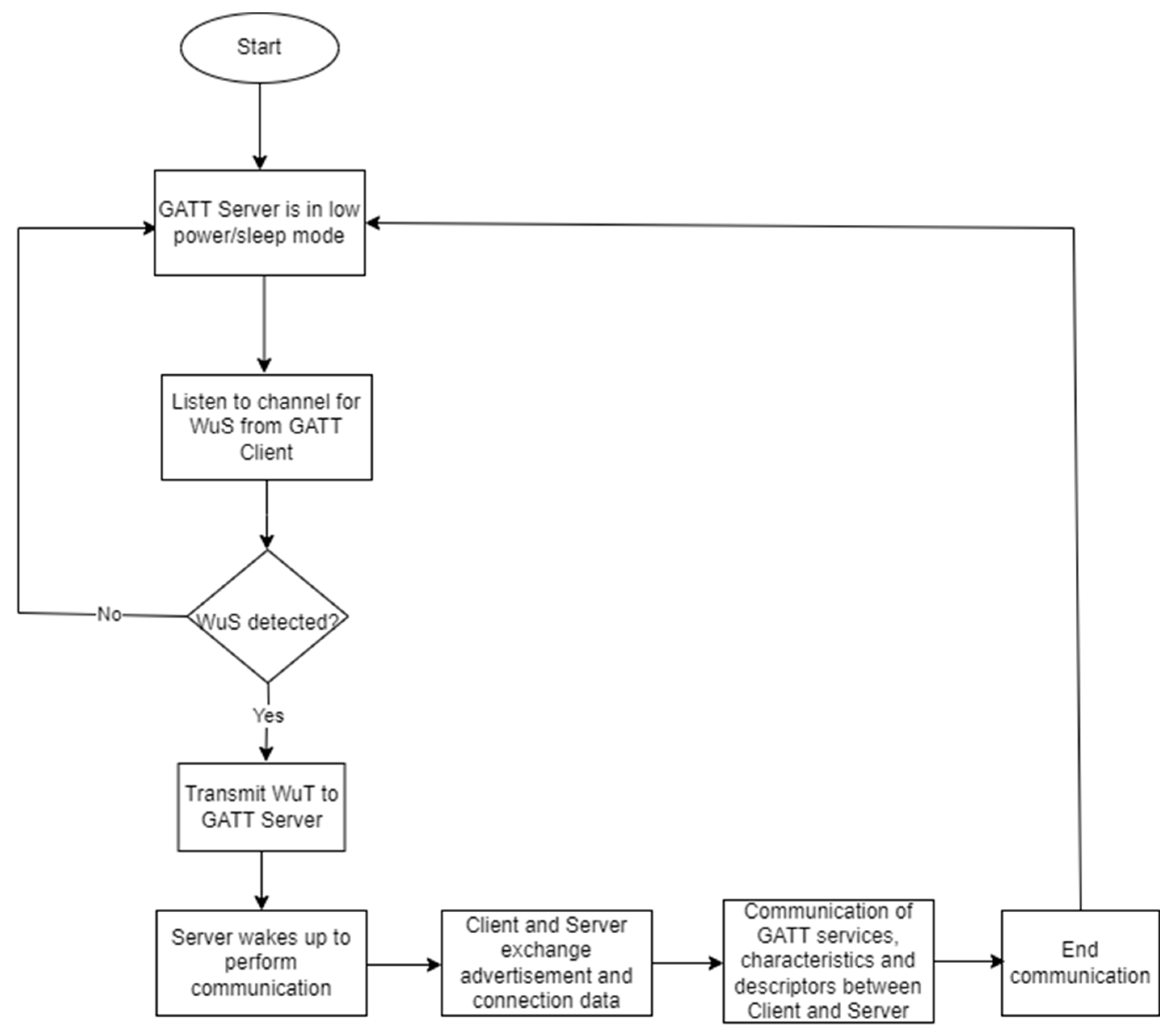

4.2.1. Simulation Workflow

The simulation environment is designed to capture key stages of BLE communication. The workflow includes the following steps:

-

Initialization:

The BLE device initializes in a low-power sleep state. Parameters such as advertisement intervals (1.285 seconds), sleep durations (10 seconds), and emergency notification thresholds (e.g., 140 bpm) are defined.

Randomized seeds simulate real-world variations such as environmental interference and reconnections, creating a more realistic model.

-

Duty-Cycled Advertisement:

-

Connection Establishment and GATT Discovery:

Upon connection, the central device performs service and characteristic discovery. The sensor (GATT Server) provides details of its available services, such as the Heart Rate Service.

Cached service and characteristic data are used to optimize reconnections, skipping redundant discovery processes and reducing power consumption

-

Data Transmission and Notification:

Simulated heart rate readings are transmitted to the central device. Emergency thresholds trigger immediate notifications (e.g., heart rates exceeding 140 bpm), while routine notifications occur during scheduled wake-ups.

Each data transmission is followed by the sensor returning to sleep mode to conserve power until the next scheduled communication.

Figure 1.

Server and Client Advertising and Connection Establishment Sequence.

Figure 1.

Server and Client Advertising and Connection Establishment Sequence.

Figure 2.

Code workflow a: standalone BLE bioimplant sensor.

Figure 2.

Code workflow a: standalone BLE bioimplant sensor.

4.2.2. Power Consumption Analysis

The power consumption for each event (advertising, connection establishment, data transmission) is calculated using the following formula:

where;

Current consumption during the state (3.4mA for transmit, 3.1mA for receive, 1.5µA for idle).

Size of the transmitted/received packet in bytes.

Number of BLE communication channels used.

: Operating voltage (3V).

: Communication interval (e.g., 1.285 seconds).

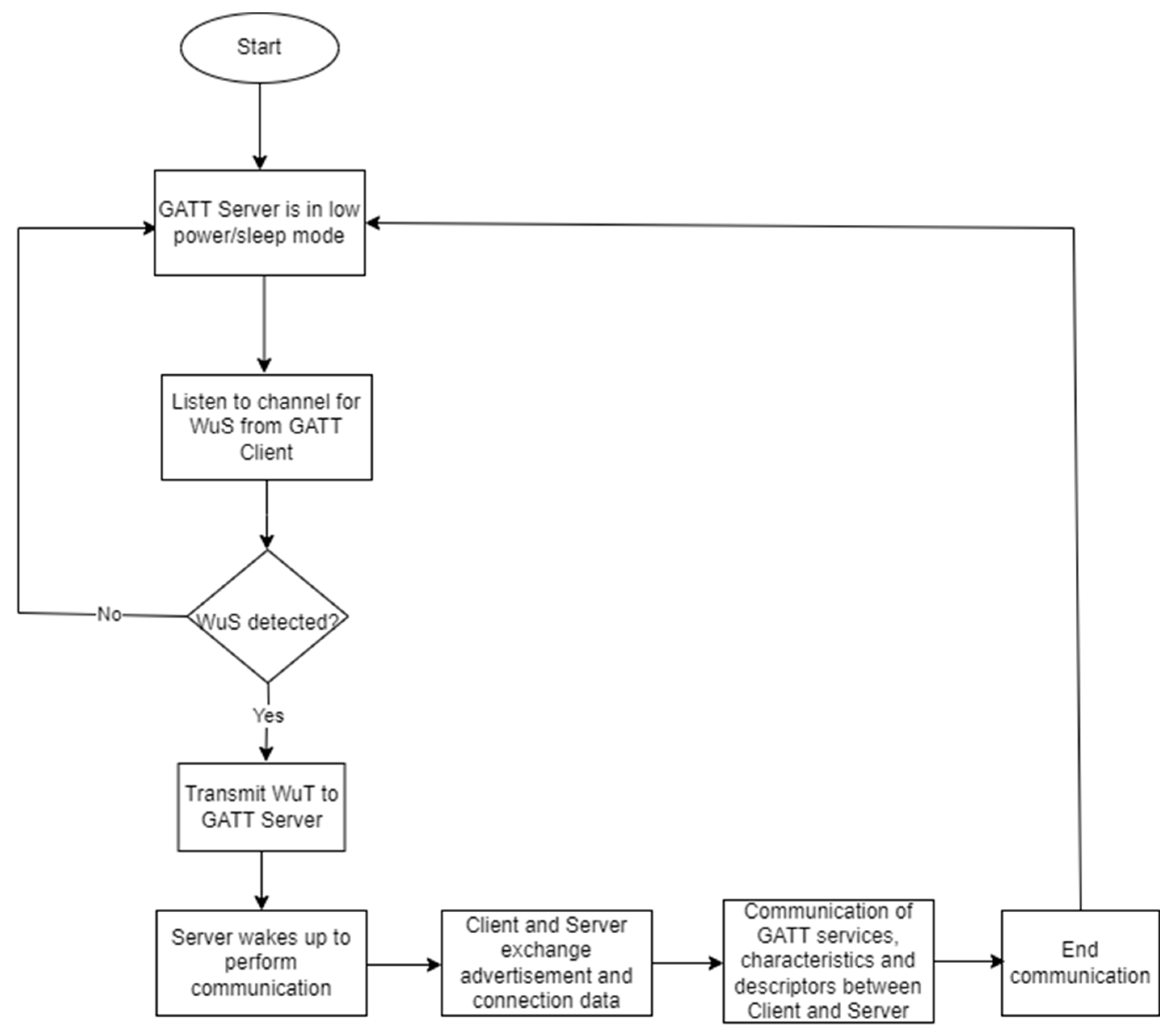

4.3. System Setup: Always-On WuR-Enabled BLE Sensor

This simulation setup explores the integration of a Wake-Up Radio (WuR) with a standalone BLE bioimplant sensor to optimize power consumption. Unlike the traditional duty-cycled BLE sensor, which wakes periodically to transmit advertisement data and listen for connection requests even in the absence of client requests, this configuration leverages a WuR to keep the BLE device in a low-power sleep state. The BLE module is activated only upon detecting a wake-up signal indicating a client's data request. Additionally, power consumption is further reduced by limiting the device from periodically transmitting sensor data after connection, especially when the data is not required by the client. Given the ultra-low power requirements of implants, the BLE sensor transmits data only when explicitly requested by the client or when critical conditions are met, such as the heart rate measurement crossing a predefined threshold. This approach significantly minimizes energy usage while maintaining responsiveness for essential operations.

Table 2.

Always-On WUR Enabled BLE Sensor Parameters.

Table 2.

Always-On WUR Enabled BLE Sensor Parameters.

| Parameter |

Value |

Description |

| WuR Active State |

5.3µA |

Current consumption when the Wake-Up Radio is active. |

| WuR Listening State |

2.7µA |

Current consumption when the Wake-Up Radio is in listening mode. |

| WuS Detection Chance |

10% |

Probability of Wake-Up Signal (WuS) detection. |

| Data Channels (Used) |

[4, 5, 14, 16, 21, 28, 36] |

Channels specified for BLE communication after WuS detection. |

4.3.1. Simulation Workflow

The workflow for the WuR-enabled BLE sensor simulation includes the following steps:

Randomized seeds are introduced to simulate real-world environmental factors, such as interference and connection variability.

- 2.

-

Wake-Up Signal Detection and Connection

The WuR scans for wake-up signals using a probabilistic model during each detection interval.

If a wake-up signal is detected, or if the device flags a reconnection requirement, the WuR activates, waking up the BLE device to begin advertising and connection attempts.

If no wake-up signal is detected, the WuR remains in the listening state conserving energy bioimplant sensor.

- 3.

-

Caching and Reconnection Detection

Cached service and characteristic data are used to optimize reconnections, avoiding redundant GATT discovery processes.

The isReconnectionRequired flag tracks device disconnections and ensures reconnections are handled efficiently.

Figure 3.

Code workflow b: WUR equipped BLE standalone bioimplant sensor.

Figure 3.

Code workflow b: WUR equipped BLE standalone bioimplant sensor.

4.3.2. Power Consumption Analysis

-

The script computes power usage based on the device’s current mode (e.g., WuR active, WuR listening, BLE transmit, BLE receive, or BLE idle). Each mode has a defined power draw.

WuR Power Calculation:

4.4. System Setup: BLE Bioimplant Sensor with Duty-Cycled WuR

This setup goes a step further to optimize power consumption through periodic wake-up checks negotiated between the BLE client and server, allowing the WuR itself to enter sleep mode for certain intervals. This introduces a minor trade-off in terms of latency, since the BLE server becomes temporarily unreachable by the client during the WuR's sleep periods. However, we consider this a reasonable compromise to further reduce the overall power consumption budget. By carefully balancing energy efficiency and responsiveness, the system ensures reliable performance for critical events while maintaining ultra-low power operation.

4.4.1. Simulation Workflow

The simulation is structured to represent key phases of BLE communication in a duty-cycled WuR environment:

-

Initialization and Setup:

Parameters: The simulation initializes with a WuR wake-up interval (wakeUpInterval) of 10 seconds, a sleep duration of 10 seconds, and an emergency notification threshold of 140 bpm.

Caching and Random Seeding: Service and characteristic data are cached after the first connection to optimize future reconnections. Random seeds simulate environmental variability and connection stability.

Wake-Up Signal Simulation: Probabilistic wake-up signal detection introduces randomness, replicating real-world scenarios.

-

Wake-Up Signal Detection and Connection:

Interval-Based Wake-Up: The WuR checks for wake-up signals at predefined intervals (wakeUpInterval). During these intervals, detection probabilities vary dynamically.

Conditional Activation: If a wake-up signal is detected or reconnection is required, the WuR activates the BLE device for communication. If no signal is detected, the WuR remains in low-power sleep mode.

-

Connection Establishment and Caching:

Figure 4.

Code workflow c: BLE heart rate sensor integrated with duty cycled WUR.

Figure 4.

Code workflow c: BLE heart rate sensor integrated with duty cycled WUR.

4.4.2. Power Consumption Analysis

The methodology for calculating power consumption in the duty-cycled WuR-enabled BLE simulation mirrors the approach used in the always-on WuR setup. Key parameters, such as power draw for various operational states (active, listening, sleep, transmit, and receive), are derived from logged events and BLE packet data. These values are computed using established formulas to ensure consistency and accuracy across both configurations, with adjustments tailored to the duty-cycling mechanism.

4.5. ENERGY CONSUMPTION COMPUTATION

The energy consumption computation in the graphComparison.py script follows a step-by-step approach to calculate cumulative energy from power values over time, using data from CSV files. A detailed breakdown of the computation process is described below:

Loading CSV Data:

The script loads timestamped power data from CSV files corresponding to different configurations (e.g., Always-On WUR, Duty-Cycled WUR, Duty-Cycled BLE).

-

For each CSV file, load_csv reads two main columns: Time (s) and Power (mA), representing the time in seconds and power consumption in milliamps at that moment.

Cumulative Energy Calculation:

-

The function calculate_cumulative_energy performs the core energy calculation. Here’s how it works:

Time Intervals: For each entry in time_values, it calculates the time difference (time_interval) between consecutive timestamps.

Power Conversion: Power values (in mA) are converted to watts (W) by using the operating voltage:

Energy for Each Interval: Energy consumption for each interval is calculated by multiplying the converted power (W) by the time_interval (s):

Cumulative Total: A running total (total_energy) accumulates energy across intervals, building a cumulative energy list (cumulative_energy). This list captures how much energy has been consumed by the device up to each timestamp.

Output for Graphing:

The final cumulative energy values provide a complete energy profile over time, which we use to observe trends and transitions in energy use as the device operates.

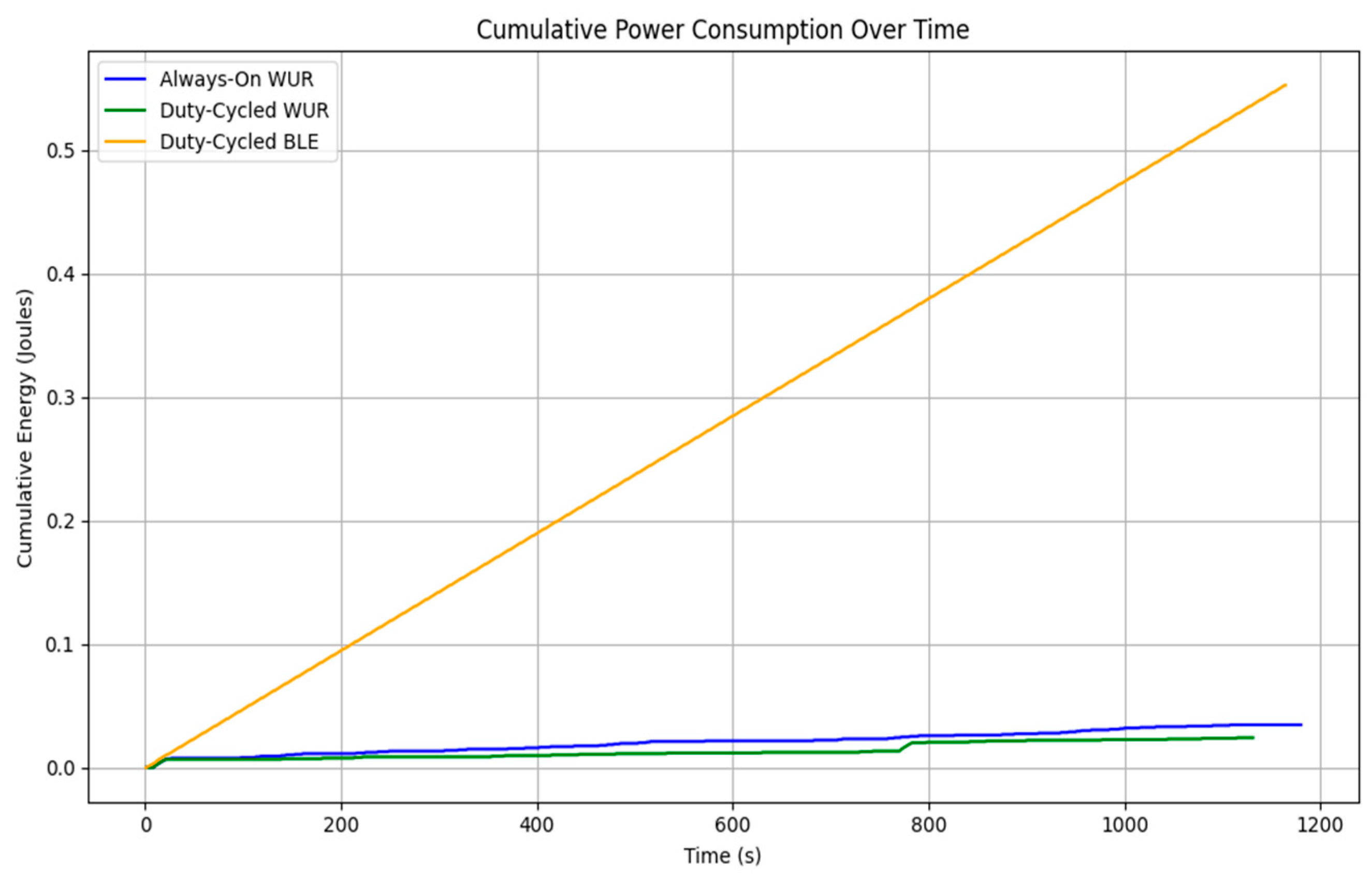

5. Results

This section presents the experimental results for the three simulation configurations designed to evaluate the energy efficiency of BLE bioimplant sensors integrated with Wake-Up Radios (WuRs). The experiments analyze cumulative energy consumption for standalone duty-cycled BLE, Always-On WuR, and Duty-Cycled WuR configurations. Additionally, a comparative analysis highlights the energy trade-offs and suitability of each approach for long-term bioimplant applications.

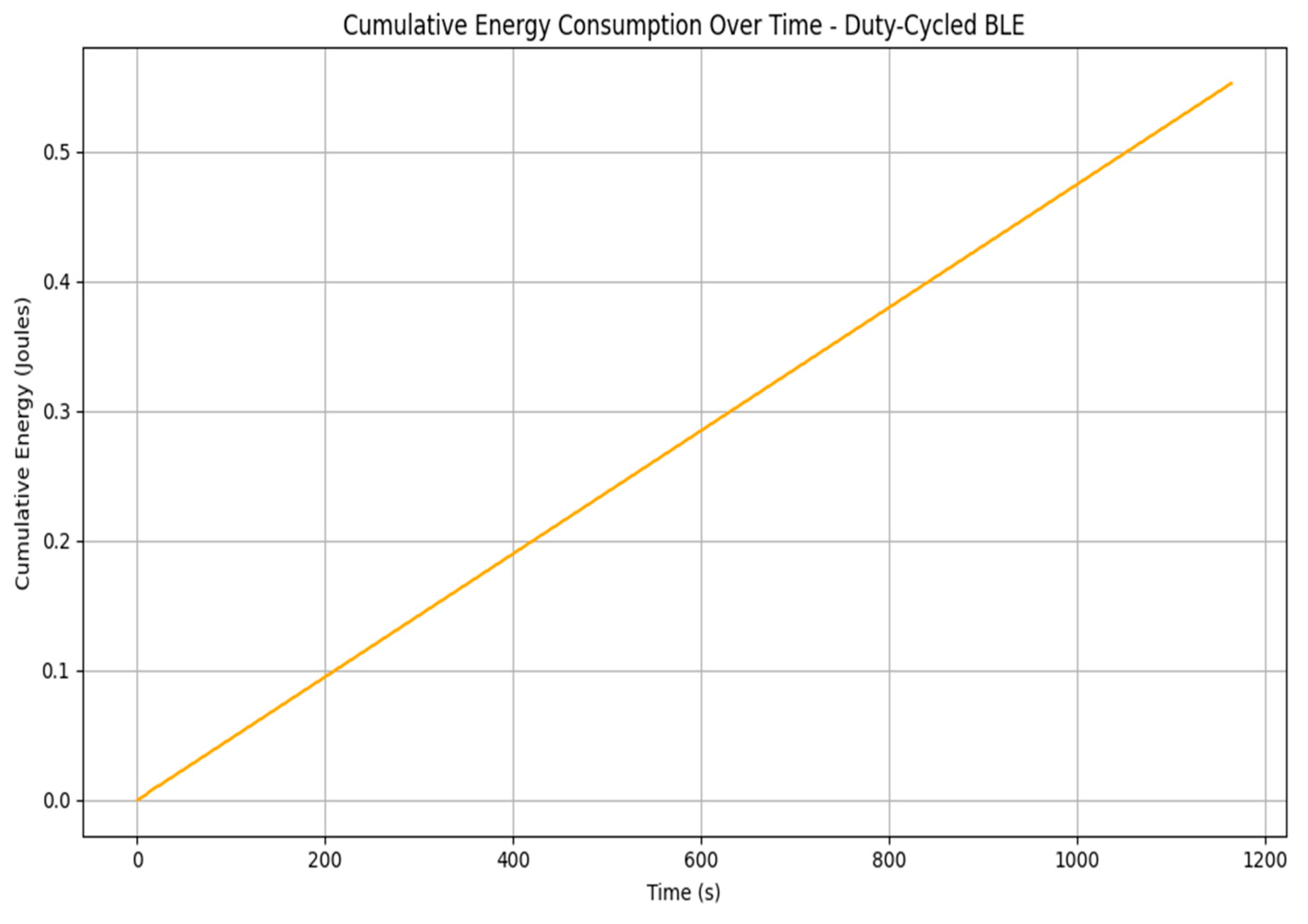

5.1. Scenario 1: Standalone BLE Bioimplant Sensor

This scenario evaluates the energy consumption of a standalone BLE bioimplant sensor operating in a duty-cycled configuration. The BLE device alternates between active and sleep modes, with periodic wake-ups for data transmission.

The total cumulative energy consumed over a 1200-second period was 0.552684 Joules, as shown in

Figure 7. The energy consumption profile follows a linear progression, reflecting the predictable and consistent power usage of the BLE device under a duty-cycled setup.

This linear behavior demonstrates the suitability of BLE for applications requiring periodic communication. However, the relatively high cumulative energy consumption compared to WuR-integrated configurations underscores the limitations of standalone BLE in scenarios demanding long-term energy efficiency.

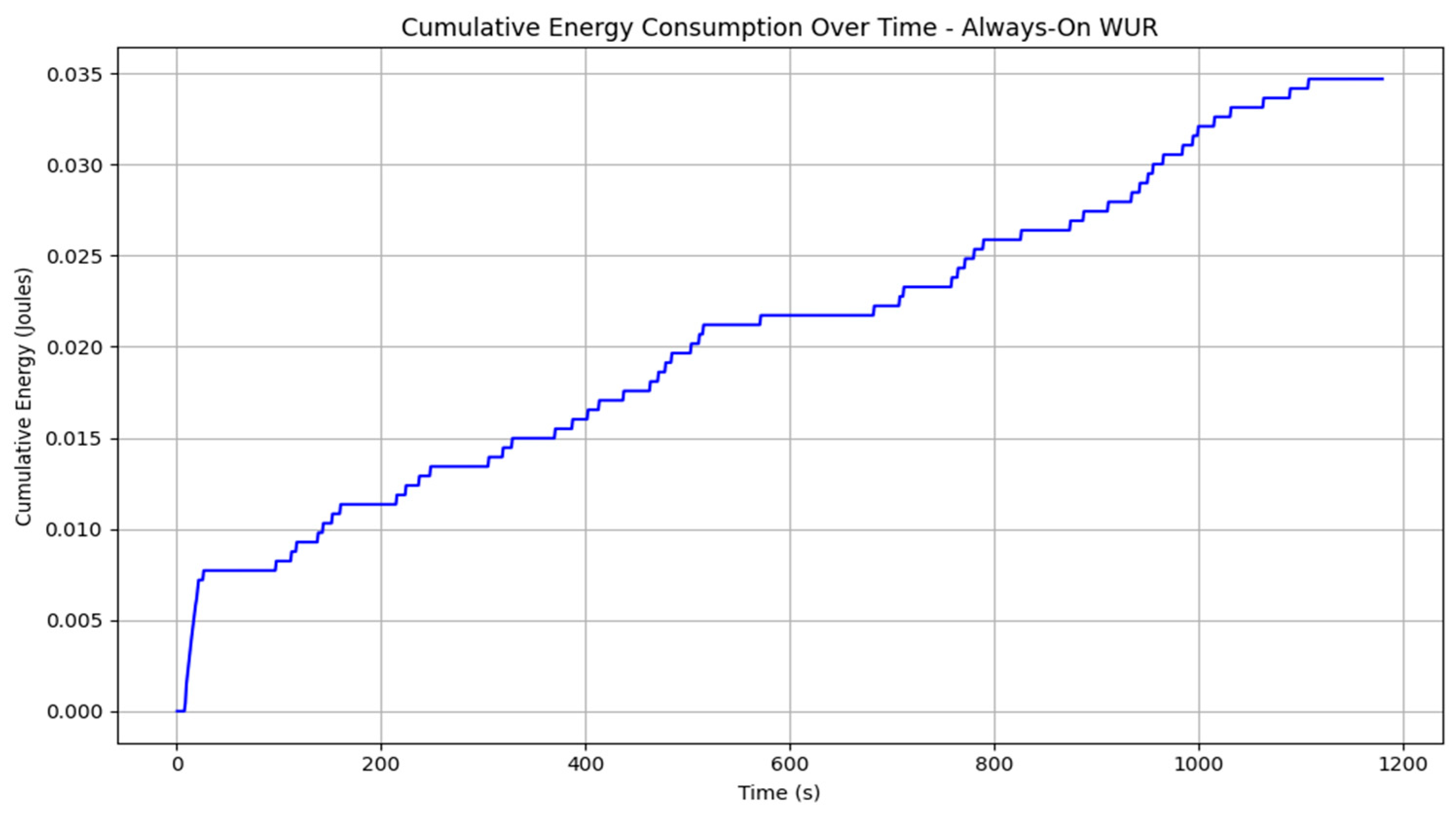

5.2. Scenario 2: Always-On WuR Integrated with BLE Bioimplant Sensor

This experiment investigates the energy consumption of a BLE bioimplant sensor integrated with an Always-On WuR. The WuR facilitates immediate wake-ups, reducing the need for continuous BLE operation.

The total cumulative energy consumption over 1200 seconds was 0.034690 Joules, as shown in

Figure 8. The stair-step pattern in the energy profile represents bursts of energy usage triggered by the WuR for BLE activations.

This result highlights the effectiveness of the Always-On WuR in reducing overall energy expenditure while maintaining responsiveness. Despite its efficiency, the continuous listening mode of the WuR results in higher energy usage compared to the Duty-Cycled WuR configuration.

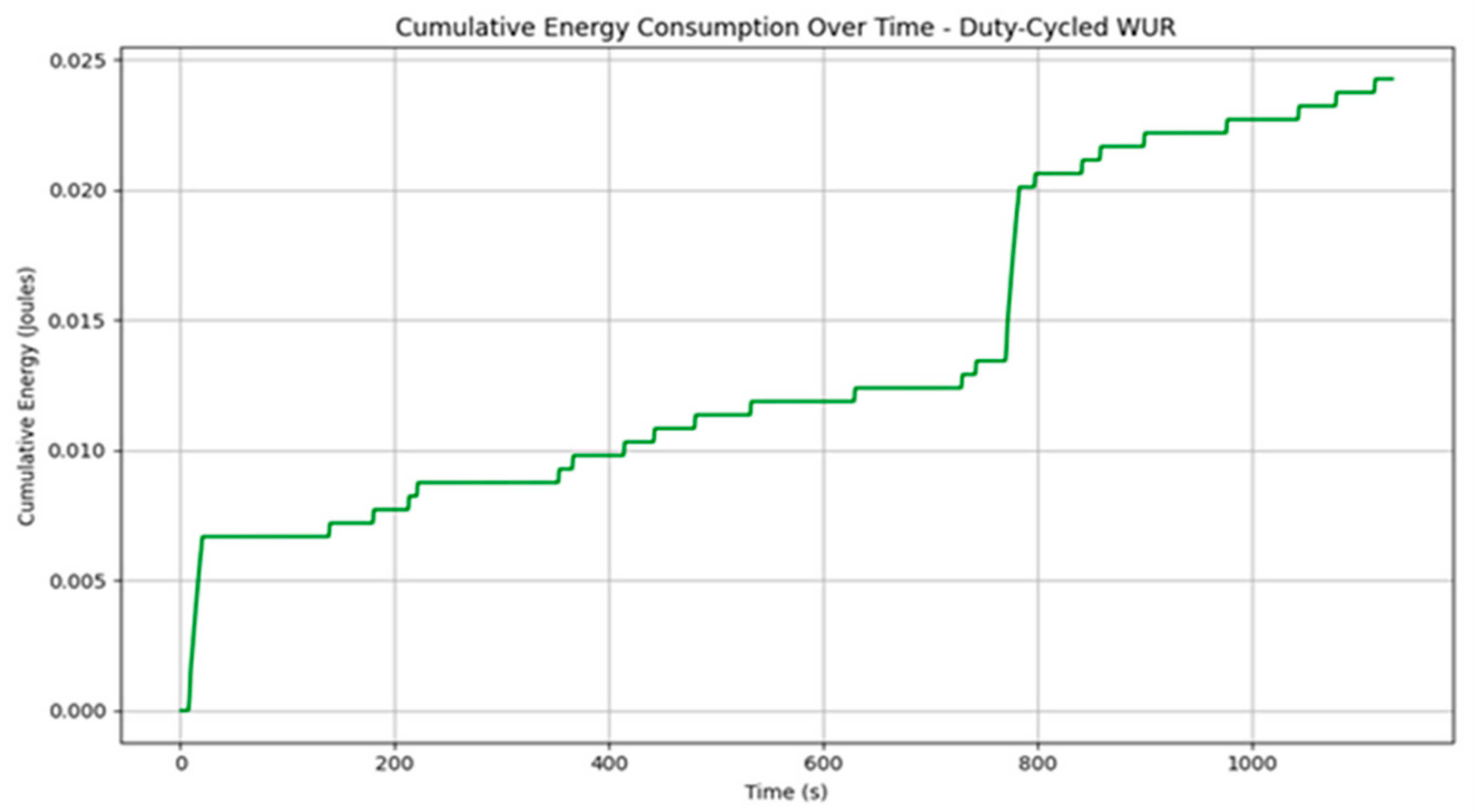

5.3. Scenario 3: Duty-Cycled WuR Integrated with BLE Bioimplant Sensor

This scenario evaluates a Duty-Cycled WuR configuration integrated with a BLE bioimplant sensor. The WuR alternates between active and sleep states, optimizing energy efficiency while ensuring timely wake-ups for critical events.

The total cumulative energy consumption over 1200 seconds was 0.024263 Joules, as depicted in

Figure 9. The energy profile exhibits gradual increases interspersed with larger steps during BLE activations, reflecting the WuR's periodic wake-up mechanism.

This configuration achieves the lowest energy consumption among the three scenarios, making it the most suitable for applications requiring extended operational lifespans and strict energy budgets.

5.4. Comparative Analysis

This section compares the energy efficiency of the three configurations: standalone duty-cycled BLE, Always-On WuR, and Duty-Cycled WuR. The cumulative energy consumption for each configuration is summarized in

Table 4 and illustrated in

Figure 10.

6. Discussions and Conclusions

This research provides a comparative analysis of various Wake-Up Radio (WuR) configurations integrated with Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) bioimplant sensors, emphasizing their energy efficiency for sustainable bioimplant applications. The findings demonstrate the significant impact of WuR configurations on the cumulative power consumption of BLE bioimplant sensors. Among the configurations studied, the Duty-Cycled WuR approach showed a substantial reduction in energy consumption compared to the Always-On WuR and Duty-Cycled BLE setups.

The Duty-Cycled WuR emerges as a promising solution for bioimplant applications requiring extended operational lifetimes. However, this approach introduces a trade-off in the form of latency, as the BLE server becomes temporarily unavailable during the WuR's sleep periods. This trade-off is a reasonable compromise, as the system ensures energy efficiency while maintaining reliable performance for critical events. By balancing energy efficiency and responsiveness, the system provides valuable insights into optimizing WuR configurations for long-term bioimplant sensor applications.

From the perspective of previous research, this work aligns with studies that highlight the potential of WuRs to reduce energy consumption in BLE-enabled systems. For instance, Sultania et al. [

8] demonstrated the benefits of integrating WuRs into BLE devices, achieving reduced latency and energy consumption for energy-harvesting IoT systems. However, their work focused on batteryless BLE nodes and did not explore Duty-Cycled WuRs or implantable sensors. Similarly, Mikhaylov et al. [

21] evaluated BLE wearables with WuRs, emphasizing their energy-saving potential during aperiodic data transmissions but also did not explore bioimplant-specific applications.

This study uniquely contributes to the field by evaluating the Duty-Cycled WuR configuration in the context of implantable sensors, a domain previously unexplored. While WuR configurations have been shown to outperform Duty-Cycled BLE in terms of energy efficiency, as indicated by prior research, our work demonstrates that Duty-Cycled WuRs offer further optimization opportunities, particularly for applications requiring aperiodic operation with minimal power budgets.

Future research should address some limitations of this study. For example, this work excluded acknowledgments, retransmissions, encryption, and security-related packets, which could increase energy consumption under realistic conditions. Incorporating these parameters into future simulations will enhance the accuracy of energy profiling. Moreover, experimental validation through prototype development under controlled laboratory conditions is essential to bridge the gap between simulation results and real-world performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and F.K.; methodology, S.K. and FK.; software, S.K.; validation, S.K. and F.K.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, S.K.; resources, S.K.; data curation, S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.K. and F.K.; visualization, S.K.; supervision, F.K.; project administration, S.K., FK.; funding acquisition, F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WuR |

Wake-up Radio |

| BLE |

Bluetooth Low Energy |

| IMD |

Implantable Medical Device |

| PDU |

Protocol Data Unit |

| WBAN |

Wireless Body Area Network |

| WSN |

Wireless Sensor Network |

| WuS |

Wake-up Signal |

| WuT |

Wake-up Trigger |

| WuTx |

Wake-up Signal Transmit |

| WuRx |

Wake-up Signal Receive |

| GATT |

Generic Attribute Profile |

References

- Brancato, L.; Keulemans, G.; Verbelen, T.; Meyns, B.; Puers, R. An implantable intravascular pressure sensor for a ventricular assist device. Micromachines 2016, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbert, L.; Baranowski, J.; Delshad, B.; Ahn, H. Left atrial pressure monitoring with an implantable wireless pressure sensor after implantation of a left ventricular assist device. ASAIO Journal 2017, 63, e60–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiger, C.; Abramson, A.; Nadeau, P.; Chandrakasan, A.P.; Langer, R.; Traverso, G. Ingestible electronics for diagnostics and therapy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 4, 83–98[ CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzstein, W. Bluetooth wireless technology cybersecurity and diabetes technology devices. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2019. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liendo, A.; Morche, D.; Guizzetti, R.; Rousseau, F. Efficient Bluetooth low energy operation for low duty cycle applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications, Kansas City, MO, USA, 20–24 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, J.; Reynolds, M.S. All-digital single sideband (SSB) Bluetooth low energy (BLE) backscatter with an inductor-free, digitally-tuned capacitance modulator. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/MTT-S International Microwave Symposium (IMS), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 4–6 August 2020; pp. 468–471. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Martin, A. Bluetooth low energy used for memory acquisition from smart health care devices. In Proceedings of the 17th IEEE International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications, New York, NY, USA, 1–3 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sultania, A.K.; Delgado, C.; Famaey, J. Enabling low-latency Bluetooth low energy on energy harvesting batteryless devices using wake-up radios. Sensors 2020, 20, 5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piyare, R.; Murphy, A.L.; Kiraly, C.; Tosato, P.; Brunelli, D. Ultra low power wake-up radios: A hardware and networking survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 2117–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, A.; Macciantelli, G.; Errico, V.; Gruppioni, E.; Saggio, G. Evaluation of dedicated Bluetooth low energy wireless data transfer for an implantable EMG sensor. In Proceedings of the 2020 Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–3 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, W.; Lu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Kim, J.U.; Shen, H.; Wu, Y.; Luan, H.; Kilner, K.; Lee, S.P.; Lu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Wegener, A.J.; Moreno, J.A.; Xie, Z.; Wu, Y.; Won, S.M.; Kwon, K. A wireless and battery-less implant for multimodal closed-loop neuromodulation in small animals. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujeeb, M.; Nazari, M.H.; Sencan, M.; Van Antwerp, W. A novel needle-injectable millimeter-scale wireless electrochemical glucose sensing platform for artificial pancreas applications. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, J.; Reynolds, M. A 1.0-Mb/s 198-pJ/bit Bluetooth low-energy compatible single sideband backscatter uplink for the NeuroDisc brain-computer interface. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2019, 67, 4015–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogev, D.; Goldberg, T.; Arami, A.; Tejman-Yarden, S.; Winkler, T.E.; Maoz, B.M. Current state of the art and future directions for implantable sensors in medical technology: Clinical needs and engineering challenges. APL Bioeng. 2023, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silemek, B.; Acikel, V.; Oto, C.; Alipour, A.; Aykut, Z.G.; Algin, O.; Atalar, E. A temperature sensor implant for active implantable medical devices for in vivo subacute heating tests under MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2017, 79, 2824–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J. Bluetooth low energy 4.0-based communication method for implants. In Proceedings of the 10th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI), Shanghai, China, 14–16 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Qian, B.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, Z.; Deng, J.; Liu, J.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, X. Development of an implantable wireless and batteryless bladder pressure monitor system for lower urinary tract dysfunction. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2020, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Kang, J.; Lee, J.; Hong, Y.-J.; Suh, J.; Kim, S.J. A compact base station system for biotelemetry and wireless charging of biomedical implants. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Asia-Pacific Microwave Conference (APMC), Singapore, 10–13 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Z.; Karvonen, H.; Iinatti, J. Energy efficiency evaluation of wake-up radio-based MAC protocol for wireless body area networks. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Ubiquitous Wireless Broadband (ICUWB), Nanjing, China, 10–12 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gia, T.N.; Ali, M.; Dhaou, I.B.; Rahmani, A.M.; Westerlund, T.; Liljeberg, P.; Tenhunen, H. IoT-based continuous glucose monitoring system: A feasibility study. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 109, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylov, K.; Karvonen, H. Wake-up radio-enabled BLE wearables: Empirical and analytical evaluation of energy efficiency. IEEE Commun. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli, D.; Milosevic, B.; Brunelli, D.; Farella, E. Enhancing Bluetooth low energy with wake-up radios for IoT applications. In Proceedings of the International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Valencia, Spain, 26–30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Monowar, M.M.; Alassafi, M.O. On the design of thermal-aware duty-cycle MAC protocol for IoT healthcare. Sensors 2020, 20, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Guo, A.; Nguyen, H.T.; Su, S. Intelligent management of multiple access schemes in wireless body area networks. J. Netw. 2015, 10, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The MathWorks, Inc. Bluetooth® Toolbox Getting Started Guide; The MathWorks, Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2022–2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H. A comprehensive study of Bluetooth low energy. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2093, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, M. Bluetooth Core Specification v5.1 Feature Overview. Bluetooth Special Interest Group (SIG) 2020. (accessed on 16 December 2024). (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Kodi, S.; Katsriku, F. BLE Wake-Up Radio Simulations; GitHub Repository: 2023. Available online: https://github.com/Coldsummers/BLE-WakeUpRadio-Simulations (accessed on 29 December 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).