Submitted:

17 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Clinical Characteristics

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinicopathological Characteristics of the Patients

3.2. Cox Regression Analysis for Predictors of OS

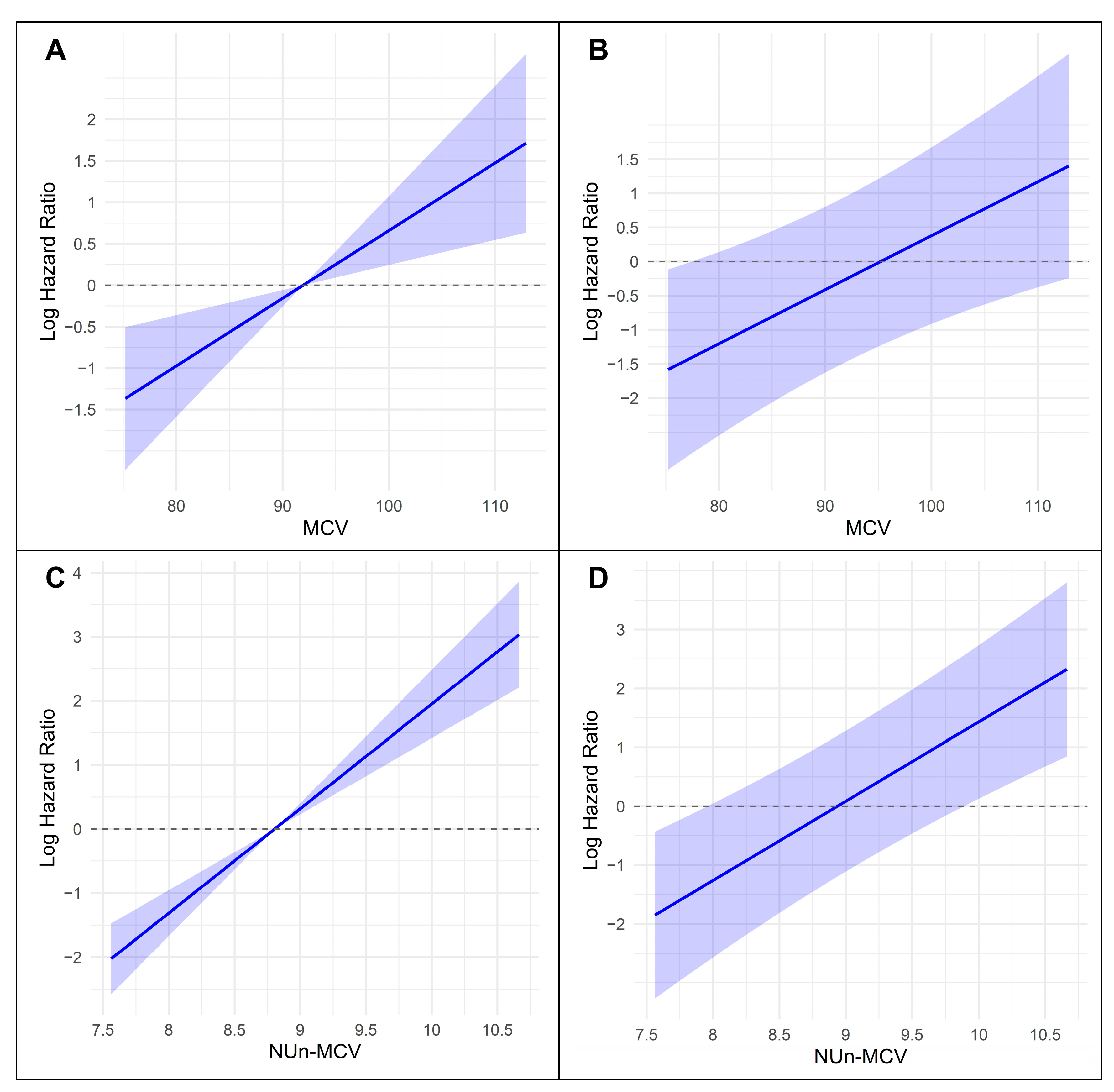

3.3. Association Between Key Variables and Log-Relative Hazard in Predicting Survival

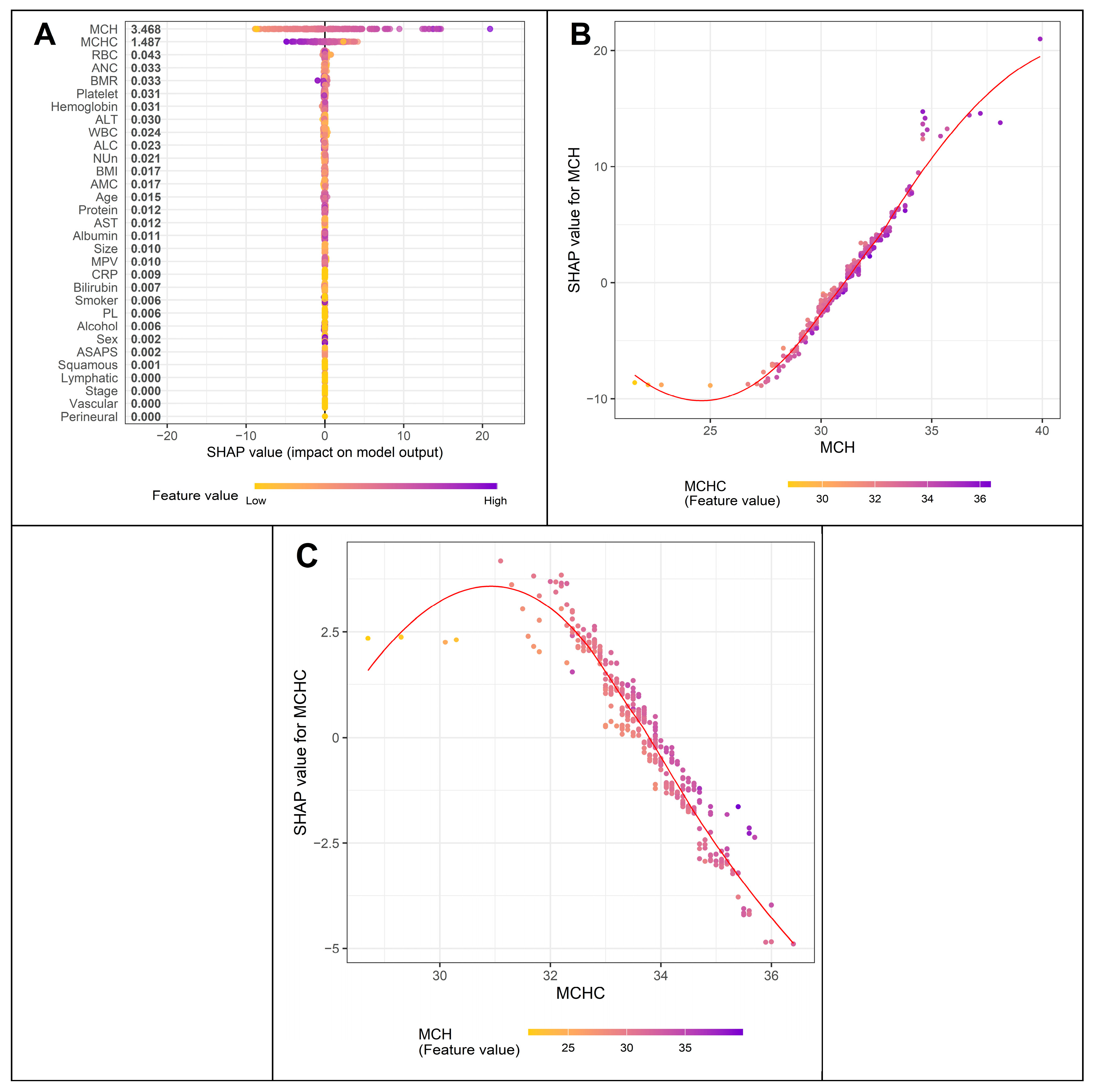

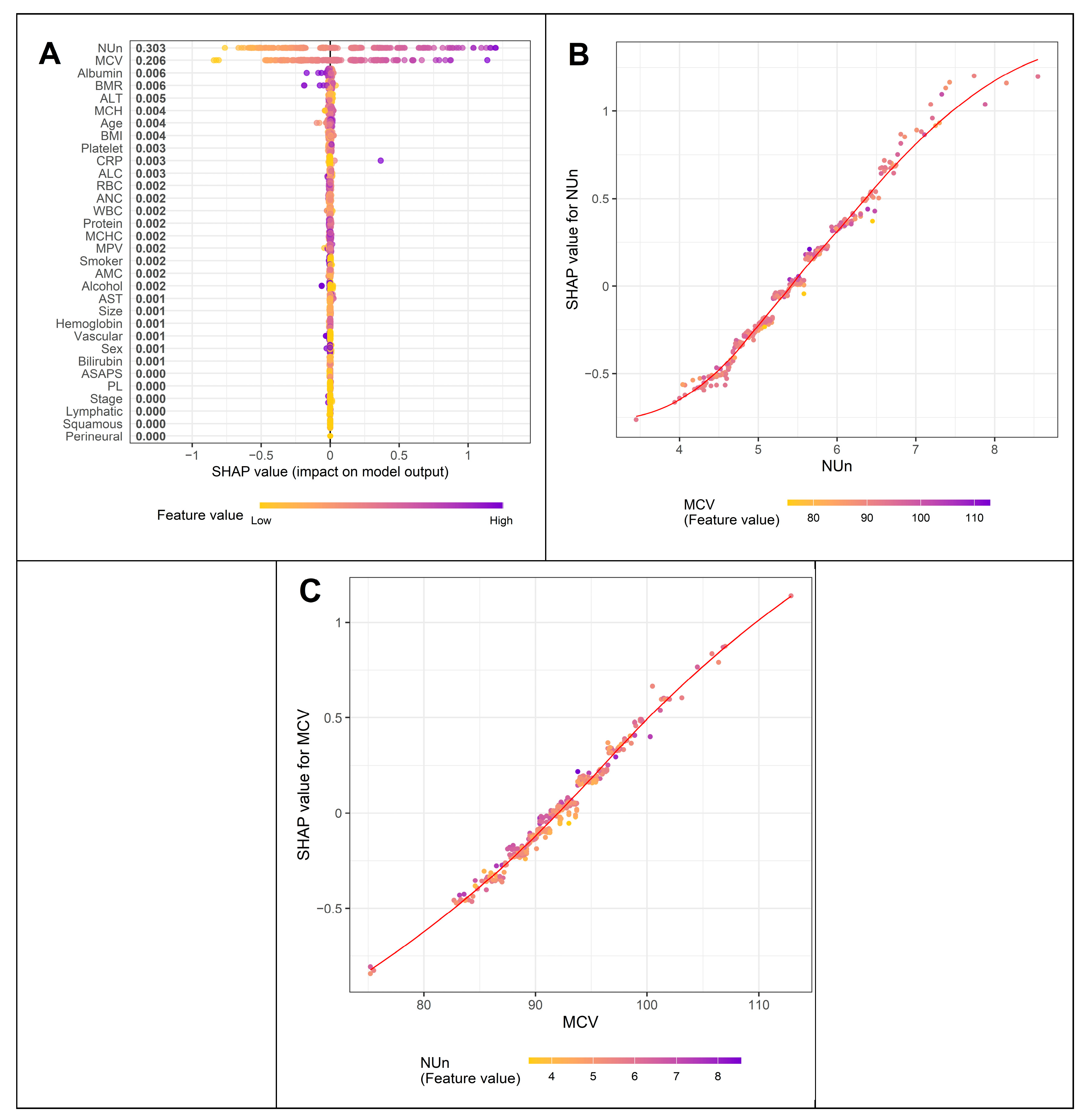

3.4. Variables Contributing to Key Variables Such as MCV and the Nun–MCV Index

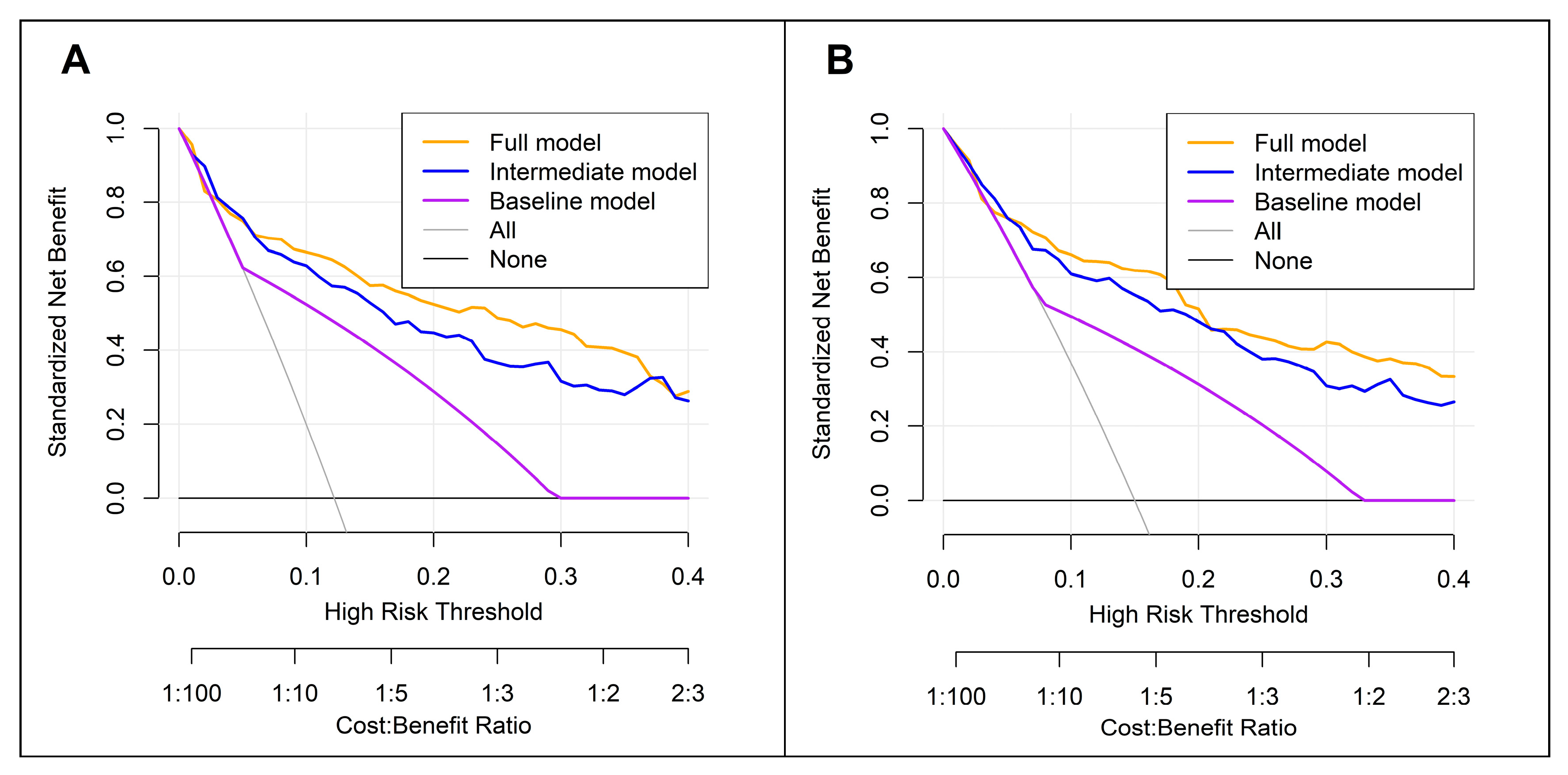

3.5. Comparison Between the Full, Baseline, and Intermediate Models

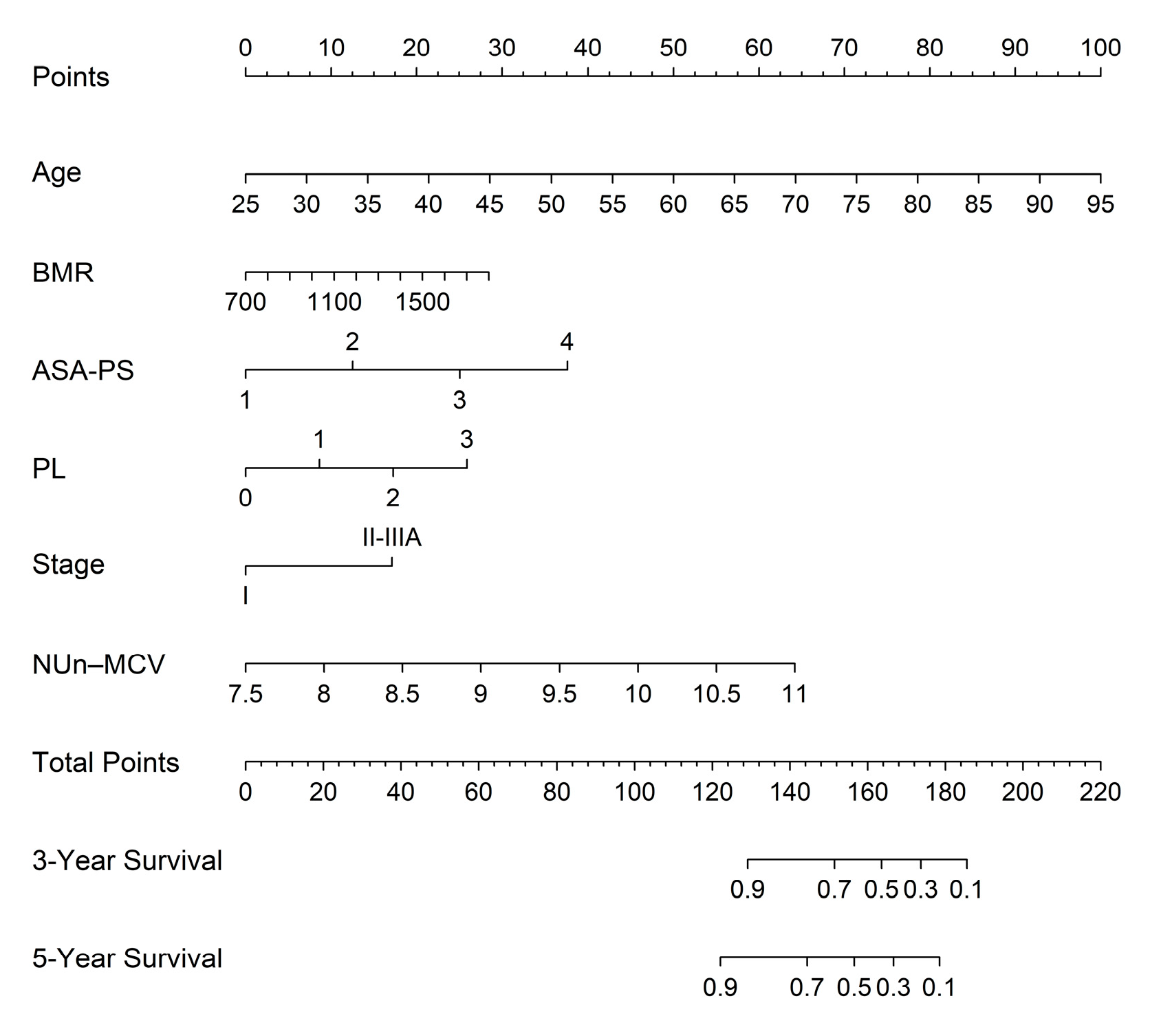

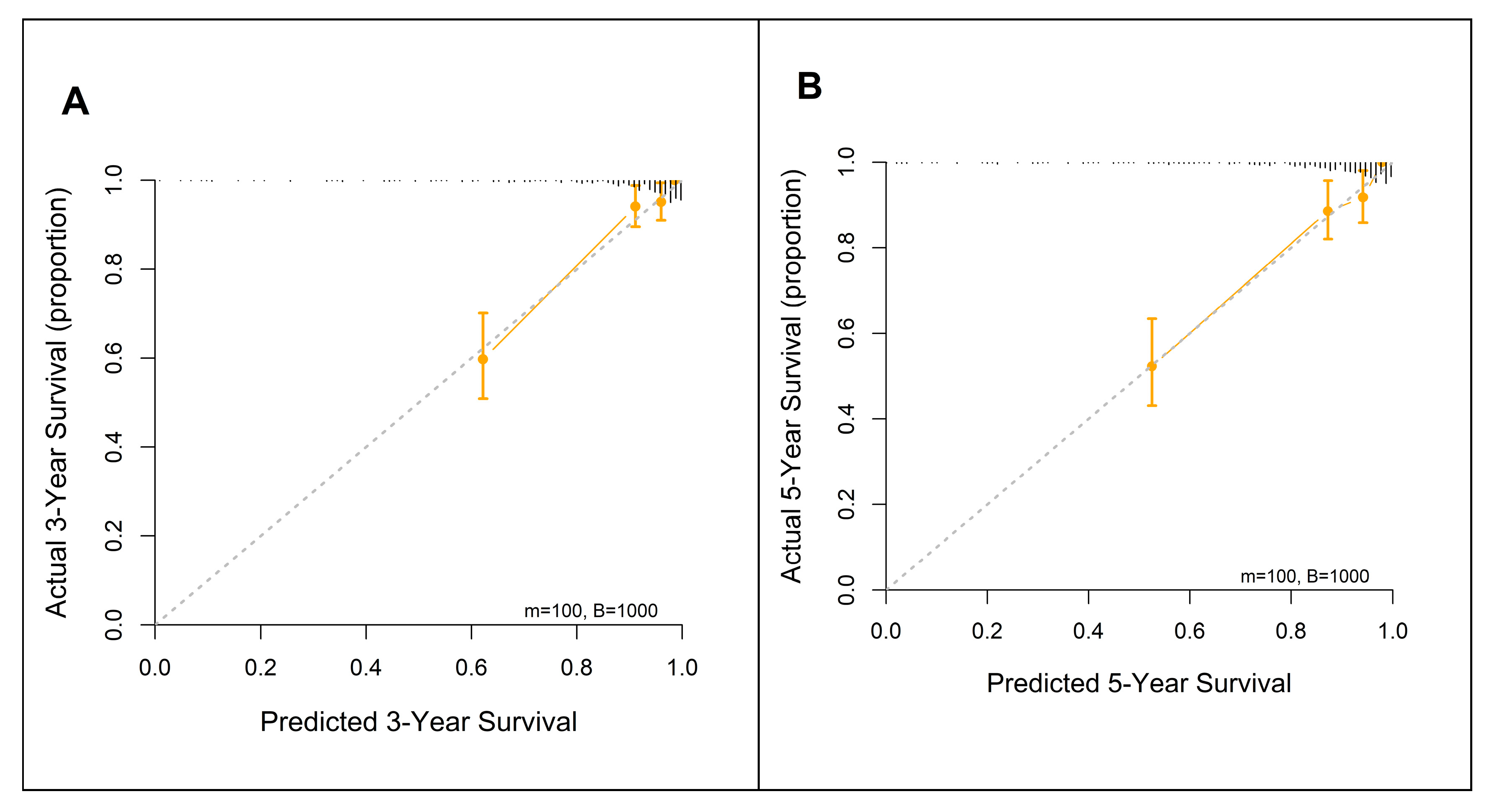

3.6. Nomogram for Predicting 3- and 5-Year Survival Using the FM

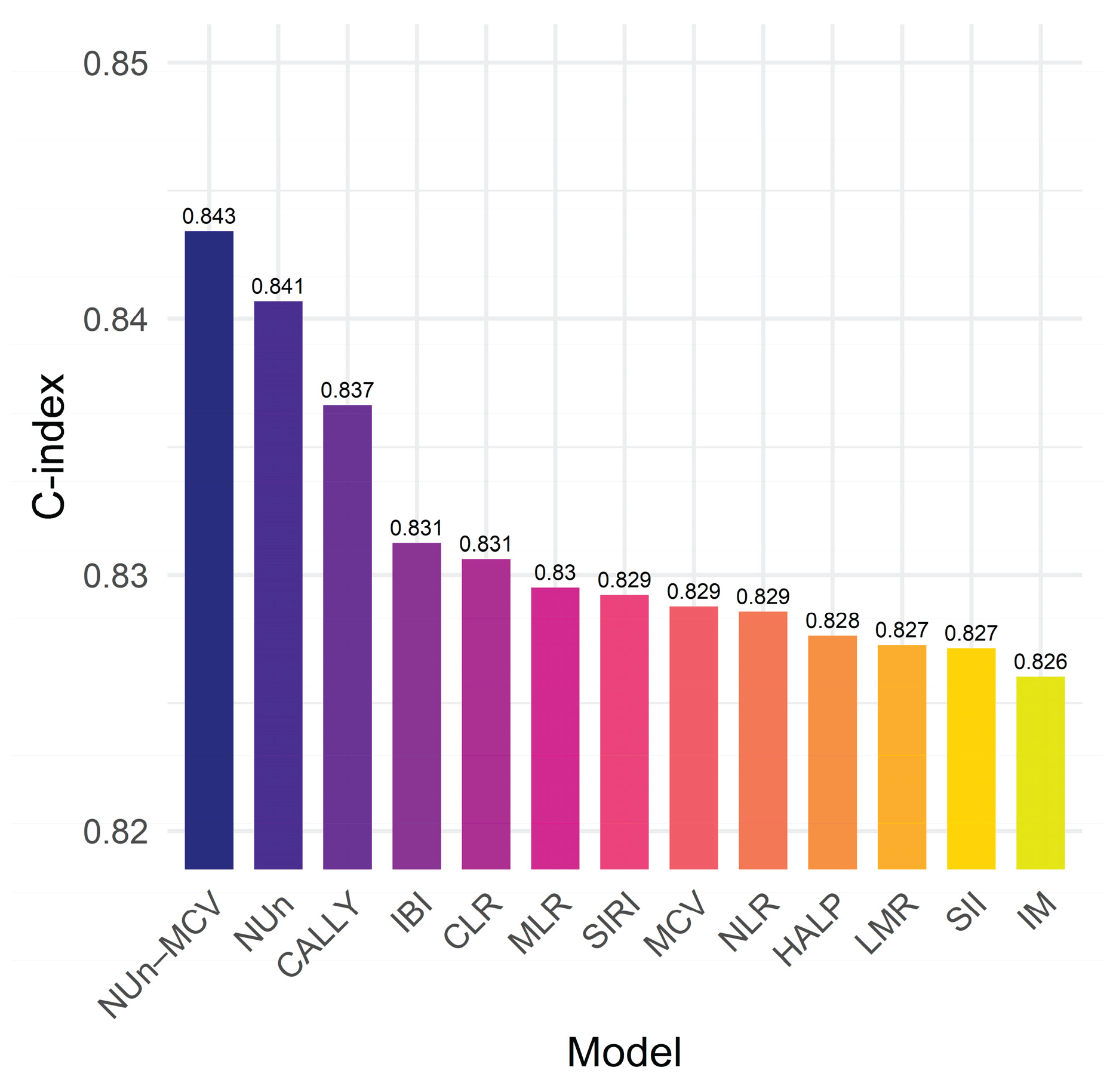

3.7. The NUn–MCV Index vs. Established Biomarkers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASA-PS | American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status |

| CALLY | CRP–albumin–lymphocyte |

| HALP | Hemoglobin–albumin–lymphocyte–platelet |

| IBI | Inflammatory burden index |

| LASSO | Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| PL | Pleural invasion |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SII | Systemic immune-inflammation index |

| SIRI | Systemic inflammation response index |

| XGBoost | Extreme gradient boosting |

References

- Zhou, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Feng, L.; Yu, J.; Chen, D. Global burden of lung cancer in 2022 and projections to 2050: Incidence and mortality estimates from globocan. Cancer Epidemiol 2024, 93, 102693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duma, N.; Santana-Davila, R.; Molina, J.R. Non-small cell lung cancer: Epidemiology, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2019, 94, 1623–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.R.; Yang, P.; Cassivi, S.D.; Schild, S.E.; Adjei, A.A. Non-small cell lung cancer: Epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc 2008, 83, 584–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, H.B. Outcome prediction and the future of the tnm staging system. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004, 96, 1408–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chansky, K.; Detterbeck, F.C.; Nicholson, A.G.; Rusch, V.W.; Vallières, E.; Groome, P.; Kennedy, C.; Krasnik, M.; Peake, M.; Shemanski, L.; et al. The iaslc lung cancer staging project: External validation of the revision of the tnm stage groupings in the eighth edition of the tnm classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2017, 12, 1109–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstraw, P.; Chansky, K.; Crowley, J.; Rami-Porta, R.; Asamura, H.; Eberhardt, W.E.; Nicholson, A.G.; Groome, P.; Mitchell, A.; Bolejack, V. The iaslc lung cancer staging project: Proposals for revision of the tnm stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the tnm classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016, 11, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balata, H.; Foden, P.; Edwards, T.; Chaturvedi, A.; Elshafi, M.; Tempowski, A.; Teng, B.; Whittemore, P.; Blyth, K.G.; Kidd, A.; et al. Predicting survival following surgical resection of lung cancer using clinical and pathological variables: The development and validation of the lnc-path score. Lung Cancer 2018, 125, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, M.; Yonei, A.; Ayabe, T.; Tomita, M.; Nakamura, K.; Onitsuka, T. Postoperative serum c-reactive protein levels in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010, 16, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miura, K.; Hamanaka, K.; Koizumi, T.; Kitaguchi, Y.; Terada, Y.; Nakamura, D.; Kumeda, H.; Agatsuma, H.; Hyogotani, A.; Kawakami, S.; et al. Clinical significance of preoperative serum albumin level for prognosis in surgically resected patients with non-small cell lung cancer: Comparative study of normal lung, emphysema, and pulmonary fibrosis. Lung Cancer 2017, 111, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Li, N.; Mao, X.; Liu, Z.; Ou, W.; Wang, S.Y. Elevated pretreatment neutrophil/white blood cell ratio and monocyte/lymphocyte ratio predict poor survival in patients with curatively resected non-small cell lung cancer: Results from a large cohort. Thorac Cancer 2017, 8, 350–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, K.; Takamori, S.; Matsubara, T.; Haratake, N.; Akamine, T.; Kinoshita, F.; Ono, Y.; Wakasu, S.; Tanaka, K.; Oku, Y.; et al. Clinical significance of preoperative inflammatory markers in non-small cell lung cancer patients: A multicenter retrospective study. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0241580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcam, T.I.; Tekneci, A.K.; Turhan, K.; Duman, S.; Cuhatutar, S.; Ozkan, B.; Kaba, E.; Metin, M.; Cansever, L.; Sezen, C.B.; et al. Prognostic value of systemic inflammation markers in early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 33886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.J.; Hur, J.Y.; Eo, W.; An, S.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, S. Clinical significance of c-reactive protein to lymphocyte count ratio as a prognostic factor for survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients undergoing curative surgical resection. J Cancer 2021, 12, 4497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Ruan, G.T.; Liu, T.; Xie, H.L.; Ge, Y.Z.; Song, M.M.; Deng, L.; Shi, H.P. The value of crp-albumin-lymphocyte index (cally index) as a prognostic biomarker in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Support Care Cancer 2023, 31, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Eo, W.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, S. Prognostic value of the noble and underwood score in patients with non-small cell lung cancer undergoing surgical resection. J Cancer 2024, 15, 6185–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, Z.; Du, H.; Zhang, W.; Che, G.; Liu, L. Novel systemic inflammation response index to predict prognosis after thoracoscopic lung cancer surgery: A propensity score-matching study. ANZ J Surg 2019, 89, E507–E513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Xie, H.; Cheng, W.; Liu, T.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Lin, S.; Liu, X.; Tian, H.; Li, X.; et al. The preoperative hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet score (halp) as a prognostic indicator in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1428950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, M.; Ayabe, T.; Maeda, R.; Nakamura, K. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts survival of patients after curative resection for non-small cell lung cancer. In Vivo 2018, 32, 663–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivennikov, S.I.; Greten, F.R.; Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G.; Goodnough, L.T. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med 2005, 352, 1011–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilreath, J.A.; Rodgers, G.M. How i treat cancer-associated anemia. Blood 2020, 136, 801–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ademuyiwa, F.O.; Johnson, C.S.; White, A.S.; Breen, T.E.; Harvey, J.; Neubauer, M.; Hanna, N.H. Prognostic factors in stage iii non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2007, 8, 478–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhao, G.; Lin, J.; Ye, Q.; Xiang, J.; Yan, B. A combined preoperative red cell distribution width and carcinoembryonic antigen score contribute to prognosis prediction in stage i lung adenocarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol 2023, 21, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, R.; Mediratta, N.; Shackcloth, M.; Shaw, M.; McShane, J.; Poullis, M. Preoperative red cell distribution width in patients undergoing pulmonary resections for non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014, 45, 108–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Shi, P.; Xiao, J.; Song, Y.; Zeng, M.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, X. Utility of red cell distribution width as a diagnostic and prognostic marker in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Che, G. Prognostic value of pre-treatment red blood cell distribution width in lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Biomarkers 2020, 25, 241–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Shi, M.; Zhang, J. Preoperative hemoglobin-to-red cell distribution width ratio as a prognostic factor in pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Transl Med 2022, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coradduzza, D.; Medici, S.; Chessa, C.; Zinellu, A.; Madonia, M.; Angius, A.; Carru, C.; De Miglio, M.R. Assessing the predictive power of the hemoglobin/red cell distribution width ratio in cancer: A systematic review and future directions. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, D.G.; Ogundipe, A.; Allen, R.H.; Stabler, S.P.; Lindenbaum, J. Etiology and diagnostic evaluation of macrocytosis. Am J Med Sci 2000, 319, 343–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.J.; Kim, K.; Nam, Y.S.; Yun, J.M.; Park, M. Mean corpuscular volume levels and all-cause and liver cancer mortality. Clin Chem Lab Med 2016, 54, 1247–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsushima, N.; Kano, S.; Suzuki, T.; Hamada, S.; Homma, A. Pretreatment elevated mean corpuscular volume as an indicator for high risk esophageal second primary cancer in patients with head and neck cancer. Auris Nasus Larynx 2023, 50, 423–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsetto, D.; Polesel, J.; Tirelli, G.; Menegaldo, A.; Baggio, V.; Gava, A.; Nankivell, P.; Pracy, P.; Fussey, J.; Boscolo-Rizzo, P. Pretreatment high mcv as adverse prognostic marker in nonanemic patients with head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E836–E845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Kano, K.; Hashimoto, I.; Suematsu, H.; Aoyama, T.; Yamada, T.; Ogata, T.; Rino, Y.; Oshima, T. Clinical significance of mean corpuscular volume in patients with locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. In Vivo 2022, 36, 2371–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, N.; Sasaki, K.; Kanetaka, K.; Kimura, Y.; Shibata, T.; Ikenoue, M.; Nakashima, Y.; Sadanaga, N.; Eto, K.; Tsuruda, Y.; et al. High pretreatment mean corpuscular volume can predict worse prognosis in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who have undergone curative esophagectomy: A retrospective multicenter cohort study. Ann Surg Open 2022, 3, e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Z.; Dai, S.Q.; Li, W.; Cao, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.J.; Fu, J.H.; Wang, J.Y. Prognostic value of preoperative mean corpuscular volume in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2013, 19, 2811–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomrich, G.; Hollenstein, M.; John, M.; Ristl, R.; Paireder, M.; Kristo, I.; Asari, R.; Schoppmann, S.F. High mean corpuscular volume predicts poor outcome for patients with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2019, 26, 976–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, H.; Yuasa, N.; Takeuchi, E.; Miyake, H.; Yoshioka, Y.; Miyata, K. The mean corpuscular volume as a prognostic factor for colorectal cancer. Surg Today 2018, 48, 186–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J. Clinical significance of mean corpuscular volume as a prognostic indicator of radiotherapy for locally advanced lung cancer: A retrospective cohort study. J Thorac Dis 2022, 14, 4916–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travis, W.D. The 2015 who classification of lung tumors. Pathologe 2014, 35, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detterbeck, F.C.; Boffa, D.J.; Kim, A.W.; Tanoue, L.T. The eighth edition lung cancer stage classification. Chest 2017, 151, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanek, P.; Wittekind, C. The pathologist and the residual tumor (r) classification. Pathol Res Pract 1994, 190, 115–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Seishima, R.; Matsui, S.; Shigeta, K.; Okabayashi, K.; Kitagawa, Y. The prognostic impact of preoperative mean corpuscular volume in colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2022, 52, 562–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifflin, M.D.; Jeor, S.T.S.; Hill, L.A.; Scott, B.J.; Daugherty, S.A.; Koh, Y.O. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am J Clin Nutr 1990, 51, 241–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawase, A.; Yoshida, J.; Miyaoka, E.; Asamura, H.; Fujii, Y.; Nakanishi, Y.; Eguchi, K.; Mori, M.; Sawabata, N.; Okumura, M.; et al. Visceral pleural invasion classification in non-small-cell lung cancer in the 7th edition of the tumor, node, metastasis classification for lung cancer: Validation analysis based on a large-scale nationwide database. J Thorac Oncol 2013, 8, 606–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, F.; Curtis, N.; Harris, S.; Kelly, J.J.; Bailey, I.S.; Byrne, J.P.; Underwood, T.J. Risk assessment using a novel score to predict anastomotic leak and major complications after oesophageal resection. J Gastrointest Surg 2012, 16, 1083–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, P.; Goodall, A.H. Studies on mean platelet volume (mpv) - new editorial policy. Platelets 2016, 27, 605–06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noris, P.; Melazzini, F.; Balduini, C.L. New roles for mean platelet volume measurement in the clinical practice? Platelets 2016, 27, 607–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, M.; Shimizu, T.; Hara, M.; Ayabe, T.; Onitsuka, T. Preoperative leukocytosis, anemia and thrombocytosis are associated with poor survival in non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 2009, 29, 2687–90. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Ruan, G.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Lin, S.; Song, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; et al. Inflammatory burden as a prognostic biomarker for cancer. Clin Nutr 2022, 41, 1236–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaupel, P.; Mayer, A. Hypoxia in cancer: Significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2007, 26, 225–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell 2012, 148, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Hif-1 and mechanisms of hypoxia sensing. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2001, 13, 167–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, F.; Qadri, S.M. Mechanisms and significance of eryptosis, the suicidal death of erythrocytes. Blood Purif 2012, 33, 125–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, J.P.; Harishankar, M.K.; Pillai, A.A.; Devi, A. Hypoxia induced emt: A review on the mechanism of tumor progression and metastasis in oscc. Oral Oncol 2018, 80, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, J.G.; Nagababu, E.; Rifkind, J.M. Red blood cell oxidative stress impairs oxygen delivery and induces red blood cell aging. Front Physiol 2014, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Kyriss, T.; Dippon, J.; Hansen, M.; Boedeker, E.; Friedel, G. American society of anesthesiologists physical status facilitates risk stratification of elderly patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2018, 53, 973–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Evison, M.; Michael, S.; Obale, E.; Fritsch, N.C.; Abah, U.; Smith, M.; Martin, G.P.; Shackcloth, M.; Granato, F.; et al. Pre-operative measures of systemic inflammation predict survival after surgery for primary lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2024, 25, 460–467.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, S.; Sezaki, R.; Shinohara, H. Significance of preoperative evaluation of modified advanced lung cancer inflammation index for patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.A.; Benedict, F.G. A biometric study of human basal metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1918, 4, 370–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Eo, W.; Kim, S.B.; Lee, S. Basal metabolic rate by fao/who/unu as a prognostic factor for survival in patients with gastric cancer: A cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e40665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables |

n (%) or median (IQR) |

Variables |

n (%) or median (IQR) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 68 (12) | Vascular invasion | |||

| Sex | Yes | 24 (5.6%) | |||

| Men | 252 (59.0%) | No | 403 (94.4%) | ||

| Women | 175 (41.0%) | Perineural invasion | |||

| Smoking | Yes | 7 (1.6%) | |||

| Current/Past | 185 (43.3%) | No | 420 (98.4%) | ||

| Never | 242 (56.7%) | TNM stage | |||

| Alcohol consumption | IA/IB | 302 (70.7%) | |||

| Yes | 109 (25.5%) | IIA/IIB/IIIA | 125 (29.3%) | ||

| No | 318 (74.5%) | Adjuvant therapy | |||

| BMR, kcal/day | 1256.0 (338.5) | Yes | 105 (24.6%) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.8 (4.2) | No | 322 (75.4%) | ||

| ASA-PS | WBC, × 103 per μL | 6.3 (2.2) | |||

| 1/2 | 351 (82.2%) | ANC, × 103 per μL | 3.6 (1.7) | ||

| 3/4 | 76 (17.8%) | AMC, × 103 per μL | 0.5 (0.2) | ||

| Resection | ALC, × 103 per μL | 1.8 (0.7) | |||

| Sublobar resection | 136 (31.9%) | RBC, × 106 per μL | 4.3 (2.0) | ||

| Lobectomy | 280 (65.6%) | Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.2 (2.1) | ||

| Bilobectomy | 5 (1.2%) | Hematocrit | 39.0 (5.9) | ||

| Pneumonectomy | 6 (1.4%) | MCV, fL | 91.6 (5.5) | ||

| Histology | MCH, pg | 30.9 (2.1) | |||

| Squamous | 98 (23.0%) | MCHC, g/dL | 33.7 (1.3) | ||

| Non-squamous | 329 (77.0%) | Platelet, × 106 per μL | 0.2 (0.1) | ||

| Tumor size, cm | 2.5 (1.8) | MPV, fL | 9.6 (1.1) | ||

| Pleural invasion (PL) | Protein, g/dL | 7.2 (0.7) | |||

| 0 | 329 (77.0%) | Albumin, g/dL | 4.2 (0.5) | ||

| ≥1 | 98 (23.0%) | Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.5 (0.3) | ||

| Lymphatic invasion | AST, U/L | 22 (8) | |||

| Yes | 55 (12.9%) | ALT, U/L | 16 (11) | ||

| No | 372 (87.1%) | C-reactive protein, mg/L | 1 (2) | ||

| Variables | Model 1 HR (95% CI) |

p value | Model 2 HR (95% CI) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | <0.001 |

| BMR, kcal/day | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.022 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.022 |

| ASA-PS† | 1.98 (1.32–2.99) | 0.001 | 1.98 (1.32–2.99) | 0.001 |

| Pleural invasion (PL)† | 1.60 (1.28–2.00) | <0.001 | 1.60 (1.28–2.00) | <0.001 |

| TNM stage (II/IIIA vs. I) | 2.55 (1.60–4.06) | <0.001 | 2.55 (1.60–4.05) | <0.001 |

| MCV, fL | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 0.008 | - | - |

| NUn score | 1.74 (1.34–2.27) | <0.001 | - | - |

| NUn–MCV index | - | - | 2.72 (1.74–4.25) | <0.001 |

| Metrics | Baseline Model (BM) | Intermediate Model (IM) | Full Model (FM) | Gain (FM vs. BM) |

p value | Gain (FM vs. IM) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-index | 0.691 (0.028) | 0.826 (0.023) | 0.843 (0.022) | 0.155 (0.023) | <0.001 | 0.018 (0.011) | 0.058 |

| iAUC | 0.663 (0.027) | 0.799 (0.023) | 0.812 (0.023) | 0.149 (0.009) | <0.001 | 0.015 (0.004) | <0.001 |

| cNRI 3Y | 0.514 (0.078) | <0.001 | 0.301 (0.091) | 0.010 | |||

| cNRI 5Y | 0.418 (0.075) | <0.001 | 0.187 (0.087) | 0.044 | |||

| IDI 3Y | 0.265 (0.046) | <0.001 | 0.073 (0.033) | 0.004 | |||

| IDI 5Y | 0.245 (0.044) | <0.001 | 0.050 (0.031) | 0.022 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).