Submitted:

20 November 2023

Posted:

22 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient selection

2.2. Data collection

2.3. Objective

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

3.2. Follow-up

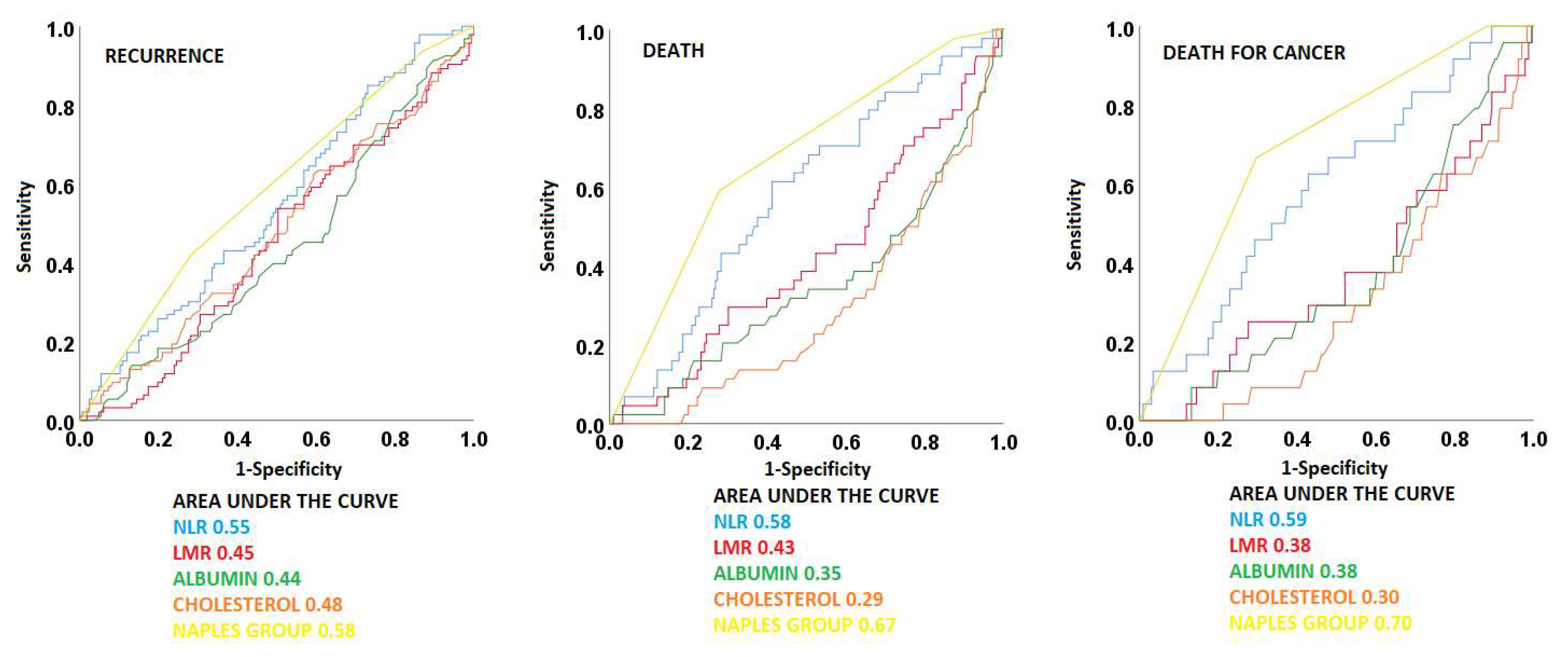

3.3. ROC curves

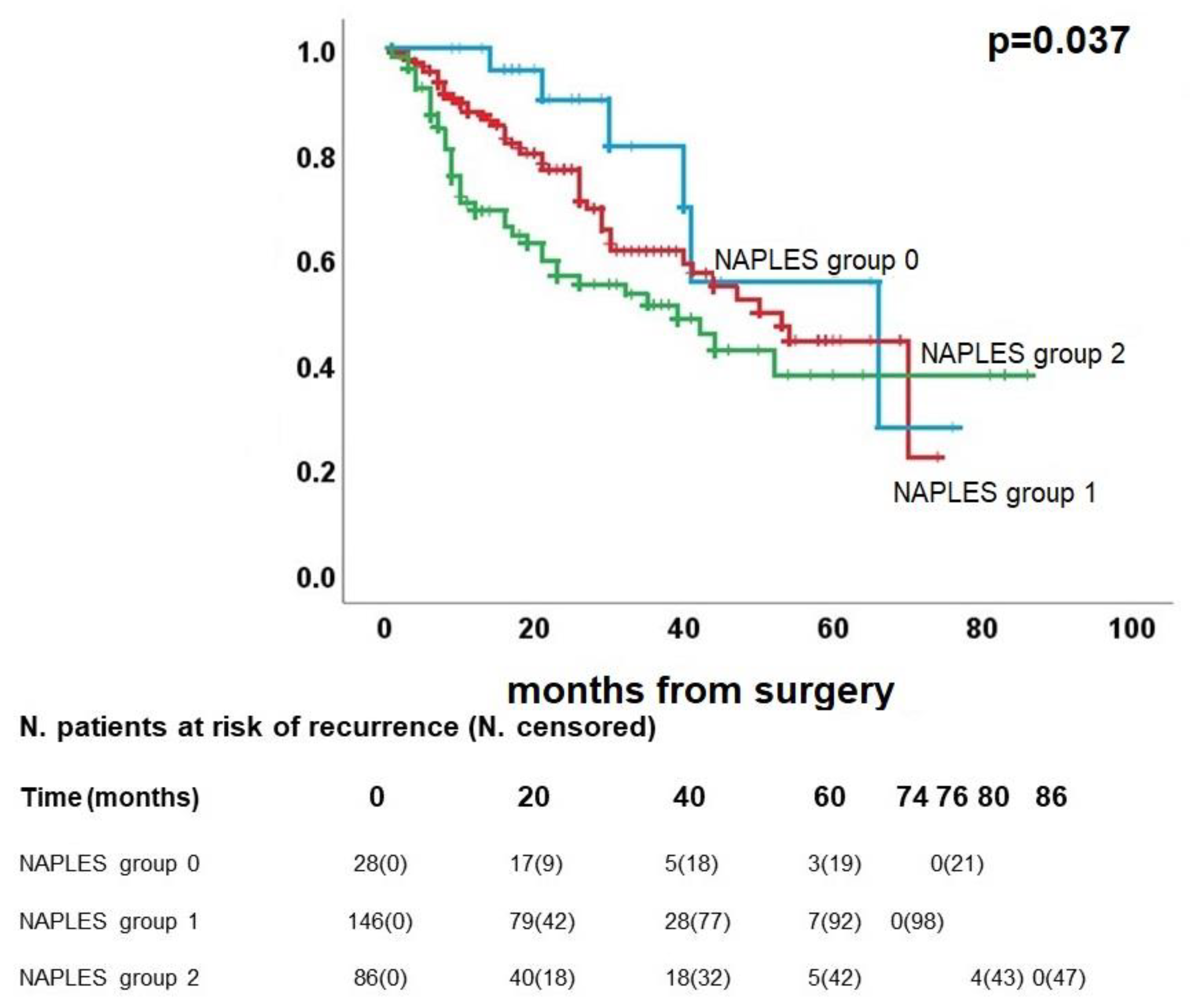

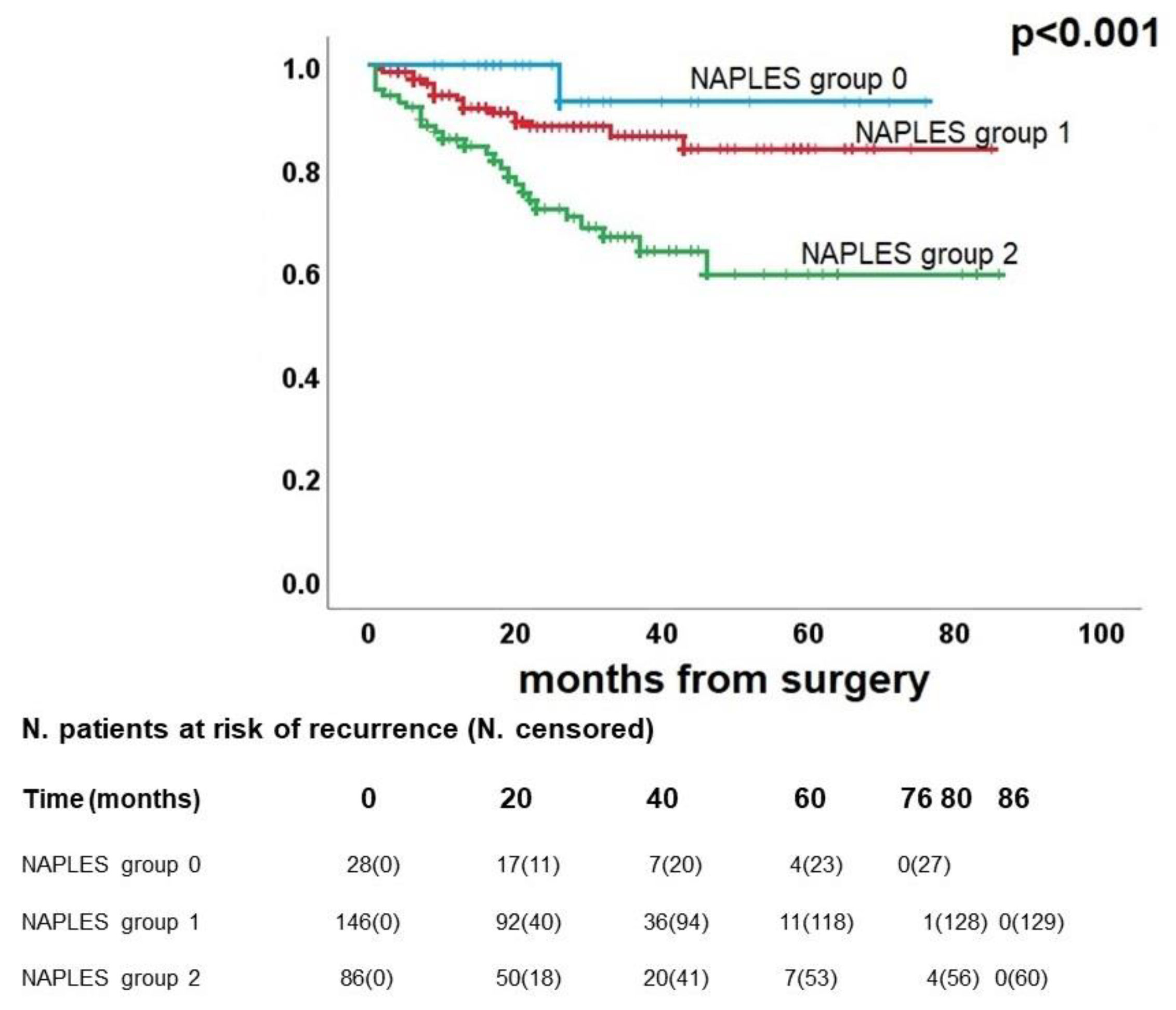

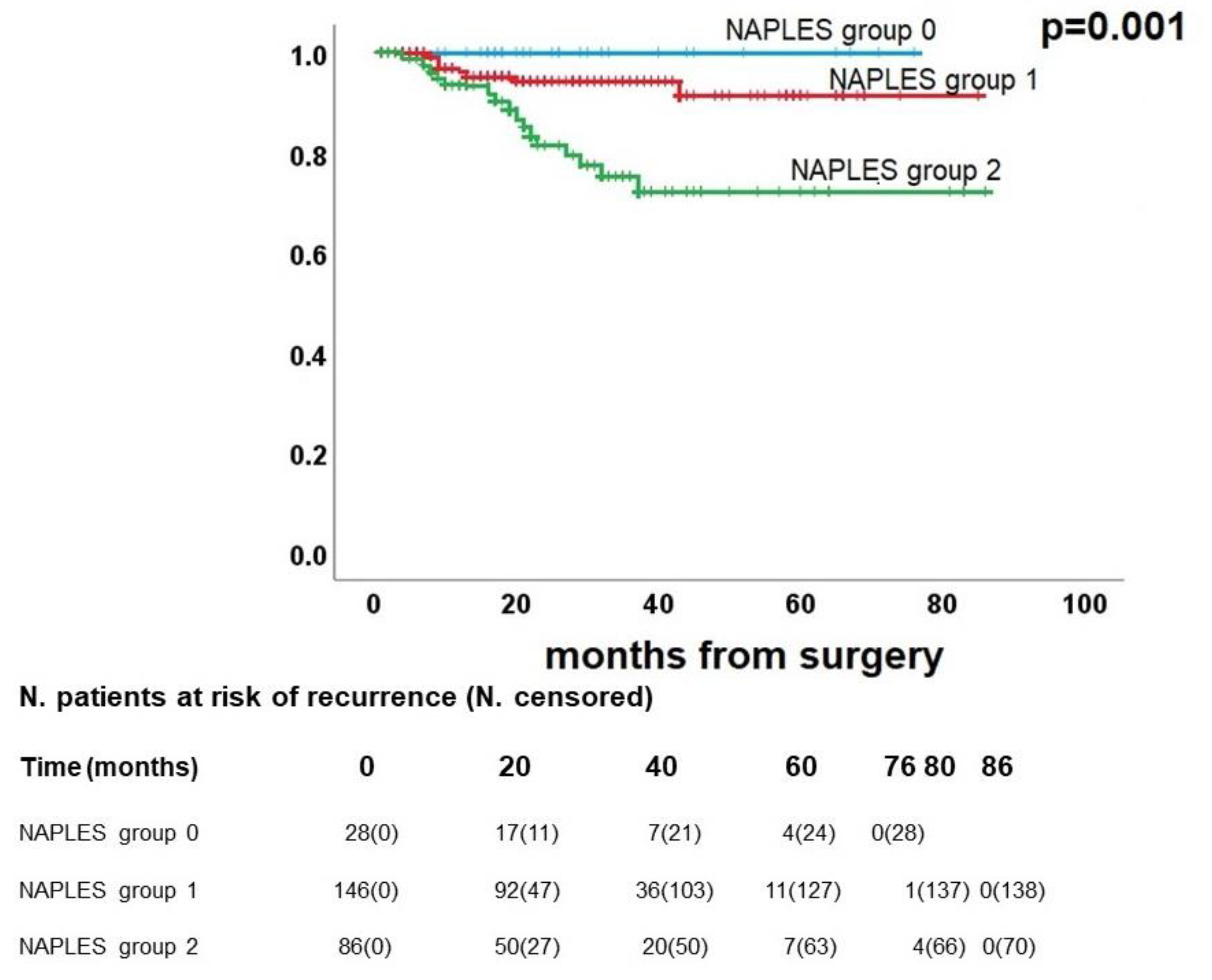

3.4. Survival analysis

3.5. Propensity score matching

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgments

Presentation

References

- Bade BC, Dela Cruz CS. Lung Cancer 2020: Epidemiology, Etiology, and Prevention. Clin Chest Med. 2020 Mar;41(1):1-24. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Jan;71(1):7-33. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Jul;71(4):359. [CrossRef]

- Ganti AK, Klein AB, Cotarla I, Seal B, Chou E. Update of Incidence, Prevalence, Survival, and Initial Treatment in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in the US. JAMA Oncol. 2021 Dec 1;7(12):1824-1832. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonoda D, Matsuura Y, Kondo Y, Ichinose J, Nakao M, Ninomiya H, Ishikawa Y, Nishio M, Okumura S, Satoh Y, Mun M. Characteristics of surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer patients with post-recurrence cure. Thorac Cancer. 2020 Nov;11(11):3280-3288. Epub 2020 Sep 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor MD, Nagji AS, Bhamidipati CM, Theodosakis N, Kozower BD, Lau CL, Jones DR. Tumor recurrence after complete resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012 Jun;93(6):1813-20; discussion 1820-1. Epub 2012 Apr 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourcerol D, Scherpereel A, Debeugny S, Porte H, Cortot AB, Lafitte JJ. Relevance of an extensive follow-up after surgery for nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2013 Nov;42(5):1357-64. Epub 2013 Mar 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Eberhardt WE, Nicholson AG, Groome P, Mitchell A, Bolejack V; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee, Advisory Boards, and Participating Institutions; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee Advisory Boards and Participating Institutions. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016 Jan;11(1):39-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzella A, Maiolino E, Maisonneuve P, Loi M, Alifano M. Systemic Inflammation and Lung Cancer: Is It a Real Paradigm? Prognostic Value of Inflammatory Indexes in Patients with Resected Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Mar 20;15(6):1854. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitvogel L, Pietrocola F, Kroemer G. Nutrition, inflammation and cancer. Nat Immunol. 2017 Jul 19;18(8):843-850. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock AF, Greenley SL, McKenzie GAG, Paton LW, Johnson MJ. Relationship between markers of malnutrition and clinical outcomes in older adults with cancer: systematic review, narrative synthesis and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020 Nov;74(11):1519-1535. Epub 2020 May 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyokawa T, Muguruma K, Yoshii M, Tamura T, Sakurai K, Kubo N, Tanaka H, Lee S, Yashiro M, Ohira M. Clinical significance of prognostic inflammation-based and/or nutritional markers in patients with stage III gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2020 Jun 3;20(1):517. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto T, Kawada K, Obama K. Inflammation-Related Biomarkers for the Prediction of Prognosis in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jul 27;22(15):8002. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang D, Hu X, Xiao L, Long G, Yao L, Wang Z, Zhou L. Prognostic Nutritional Index and Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Predict the Prognosis of Patients with HCC. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021 Feb;25(2):421-427. Epub 2020 Feb 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim M, Yildiz M, Duman E, Goktas S, Kaya V. Prognostic importance of the nutritional status and systemic inflammatory response in non-small cell lung cancer. J BUON. 2013 Jul-Sep;18(3):728-32. [PubMed]

- Galizia G, Lieto E, Auricchio A, Cardella F, Mabilia A, Podzemny V, Castellano P, Orditura M, Napolitano V. Naples Prognostic Score, Based on Nutritional and Inflammatory Status, is an Independent Predictor of Long-term Outcome in Patients Undergoing Surgery for Colorectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017 Dec;60(12):1273-1284. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li S, Wang H, Yang Z, Zhao L, Lv W, Du H, Che G, Liu L. Naples Prognostic Score as a novel prognostic prediction tool in video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for early-stage lung cancer: a propensity score matching study. Surg Endosc. 2021 Jul;35(7):3679-3697. Epub 2020 Aug 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto Y, Hiyoshi Y, Daitoku N, Okadome K, Sakamoto Y, Yamashita K, Kuroda D, Sawayama H, Iwatsuki M, Baba Y, Yoshida N, Baba H. Naples Prognostic Score Is a Useful Prognostic Marker in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019 Dec;62(12):1485-1493. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa N, Yamada S, Sonohara F, Takami H, Hayashi M, Kanda M, Kobayashi D, Tanaka C, Nakayama G, Koike M, Fujiwara M, Kodera Y. Clinical Implications of Naples Prognostic Score in Patients with Resected Pancreatic Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020 Mar;27(3):887-895. Epub 2019 Dec 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Egmond M, Bakema JE. Neutrophils as effector cells for antibody-based immunotherapy of cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013 Jun;23(3):190-9. Epub 2012 Dec 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laviron M, Combadière C, Boissonnas A. Tracking Monocytes and Macrophages in Tumors With Live Imaging. Front Immunol. 2019 May 31;10:1201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010 Apr 2;141(1):39-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambace NM, Holmes CE. The platelet contribution to cancer progression. J Thromb Haemost. 2011 Feb;9(2):237-49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiesner T, Bugl S, Mayer F, Hartmann JT, Kopp HG. Differential changes in platelet VEGF, Tsp, CXCL12, and CXCL4 in patients with metastatic cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2010 Mar;27(3):141-9. Epub 2010 Feb 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008 Jul 24;454(7203):436-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishijima TF, Muss HB, Shachar SS, Tamura K, Takamatsu Y. Prognostic value of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015 Dec;41(10):971-8. Epub 2015 Oct 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou X, Du Y, Huang Z, Xu J, Qiu T, Wang J, Wang T, Zhu W, Liu P. Prognostic value of PLR in various cancers: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014 Jun 26;9(6):e101119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang Z, Zheng Y, Wu Z, Wen Y, Wang G, Chen S, Tan F, Li J, Wu S, Dai M, Li N, He J. Association between pre-diagnostic serum albumin and cancer risk: Results from a prospective population-based study. Cancer Med. 2021 Jun;10(12):4054-4065. Epub 2021 May 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kritchevsky SB, Kritchevsky D. Serum cholesterol and cancer risk: an epidemiologic perspective. Annu Rev Nutr. 1992;12:391-416. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura K, Hamanaka K, Koizumi T, Kitaguchi Y, Terada Y, Nakamura D, Kumeda H, Agatsuma H, Hyogotani A, Kawakami S, Yoshizawa A, Asaka S, Ito KI. Clinical significance of preoperative serum albumin level for prognosis in surgically resected patients with non-small cell lung cancer: Comparative study of normal lung, emphysema, and pulmonary fibrosis. Lung Cancer. 2017 Sep;111:88-95. Epub 2017 Jul 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Xu J, Lou Y, Hu S, Yu K, Li R, Zhang X, Jin B, Han B. Pretreatment direct bilirubin and total cholesterol are significant predictors of overall survival in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients with EGFR mutations. Int J Cancer. 2017 Apr 1;140(7):1645-1652. Epub 2017 Jan 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li D, Yuan X, Liu J, Li C, Li W. Prognostic value of prognostic nutritional index in lung cancer: a meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2018 Sep;10(9):5298-5307. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Kong FF, Zhu ZQ, Shan HX. Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score is a prognostic marker in III-IV NSCLC patients receiving first-line chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2023 Mar 9;23(1):225. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang Q, Chen T, Yao Z, Zhang X. Prognostic value of pre-treatment Naples prognostic score (NPS) in patients with osteosarcoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2020 Jan 30;18(1):24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Q, Cong R, Wang Y, Kong F, Ma J, Wu Q, Ma X. Naples prognostic score is an independent prognostic factor in patients with operable endometrial cancer: Results from a retrospective cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2021 Jan;160(1):91-98. Epub 2020 Oct 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong J, Hu H, Kang W, Liu H, Ma F, Ma S, Li Y, Jin P, Tian Y. Prognostic Impact of Preoperative Naples Prognostic Score in Gastric Cancer Patients Undergoing Surgery. Front Surg. 2021 May 21;8:617744. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng JF, Zhao JM, Chen S, Chen QX. Naples Prognostic Score: A Novel Prognostic Score in Predicting Cancer-Specific Survival in Patients With Resected Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021 May 28;11:652537. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo D, Liu J, Li Y, Li C, Liu Q, Ji S, Zhu S. Evaluation of Predictive Values of Naples Prognostic Score in Patients with Unresectable Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Inflamm Res. 2021 Nov 23;14:6129-6141. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou Z, Li J, Ji X, Wang T, Chen Q, Liu Z, Ji S. Naples Prognostic Score as an Independent Predictor of Survival Outcomes for Resected Locally Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients After Neoadjuvant Treatment. J Inflamm Res. 2023 Feb 23;16:793-807. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren D, Wu W, Zhao Q, Zhang X, Duan G. Clinical Significance of Preoperative Naples Prognostic Score in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2022 Jan-Dec;21:15330338221129447. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng SM, Ren JJ, Yu N, Xu JY, Chen GC, Li X, Li DP, Yang J, Li ZN, Zhang YS, Qin LQ. The prognostic value of the Naples prognostic score for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2022 Apr 6;12(1):5782. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (IQR) | 72 (65-77) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 168 (64.6%) |

| Female | 92 (35.4%) |

| Median number of comorbidities (IQR) | 3 (IQR 2-5) |

| Smoking history, n(%) | |

| Never smoked | 37 (14.2%) |

| Former smoker | 130 (50.0%) |

| Current smoker | 93 (35.8%) |

| Surgical procedure, n(%) | |

| Pneumonectomy | 8 (3.1%) |

| Bilobectomy | 4 (1.5%) |

| Lobectomy | 187 (71.9%) |

| Segmentectomy | 10 (3.8%) |

| Wedge resection | 51 (19.6%) |

| Side of surgery, n(%) | |

| Right | 151 (58.1%) |

| Left | 109 (41.9%) |

| Lobe (pneumonectomies excluded), n(%) | |

| Upper | 151 (58.1%) |

| Middle/lingula | 11 (4.2%) |

| Lower | 90 (37.7%) |

| Final histology, n (%) | |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | 184 (70.8%) |

| Lung squamous carcinoma | 76 (29.2%) |

| pT, n(%) | |

| 1 | 115 (44.2%) |

| 2 | 103 (39.6%) |

| 3 | 29 (11.2%) |

| 4 | 13 (5.0%) |

| pN, n(%) | |

| 0 | 212 (81.5%) |

| 1 | 29 (11.2%) |

| 2 | 19 (7.3%) |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, n(%) | |

| ≤ 2.96 | …174 (66.9%) |

| >2.96 | 86 (33.1%) |

| Lymphocyte/monocyte ratio, n(%) | |

| <4.44 | 205 (78.8%) |

| ≥4.44 | 55 (21.2%) |

| Serum albumin, n(%) | |

| <4.0 g/dL | 99 (38.1%) |

| ≥4.0 g/dL | 161 (61.9%) |

| Total cholesterol, n(%) | |

| ≤ 180 mg/dL | 127 (48.8%) |

| > 180 mg/dL | 133 (51.2%) |

| NAPLES score, n (%) | |

| 0 | 28 (10.8%) |

| 1 | 56 (21.5%) |

| 2 | 90 (34.6%) |

| 3 | 63 (24.2%) |

| 4 | 23 (8.8%) |

| NAPLES group, n(%) | |

| 0 | 28 (10.8%) |

| 1 | 146 (56.2%) |

| 2 | 86 (33.1%) |

| Median follow-up, months (IQR) | 26 (15-40) |

| Recurrence, n(%) | |

| Yes | 93 (35.8%) |

| No | 167 (64.2%) |

| Median time to recurrence, months (IQR) | 16 (8-29) |

| Status, n(%) | |

| Alive | 216 (83.1%) |

| Dead | 44 (16.9%) |

| Cancer-related death, n(%) | |

| Yes | 24 (54.5%) |

| No | 20 (45.5%) |

| Median time to death, months (IQR) | 13 (6-22) |

| Disease Free Survival | Overall Survival | Cancer related Survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

| p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|

Age (≤ 72 vs > 72) years |

0.019 |

1.4 (0.9-2.1) |

0.14 | 0.057 | - |

- |

0.11 |

- |

- |

|

Gender (M vs F) |

0.13 |

- |

- | 0.10 | - |

- |

0.10 |

- |

- |

| Smoking history (never vs former/current) | 0.84 | - | - | 0.080 | - |

- |

0.41 |

- |

- |

| Surgical procedure (major vs sublobar) | 0.028 | 1.7 (1.1-2.7) | 0.020 | 0.98 | - |

- |

0.78 |

- |

- |

| Side of surgery (right vs left) | 0.057 | - | - | 0.67 | - |

- |

0.51 |

- |

- |

| Lobe (upper and middle vs lower) | 0.66 | - | - | 0.33 | - |

- |

0.25 |

- |

- |

| pT (1 vs 2-3-4) |

<0.001 |

2.2 (1.4-3.5) |

0.001 | <0.001 | 3.5 (1.5-7.9) |

0.003 |

0.003 |

4.0 (1.2-13.8) |

0.027 |

| pN (0 vs 1-2) | 0.030 | 1.4 (0.8-2.3) | 0.19 | 0.009 | 1.8 (0.9-3.4) |

0.072 |

0.002 |

2.8 (1.2-6.3) |

0.015 |

| Histology (adenocarcinoma vs squamous) | 0.013 | 1.4 (0.9-2.2) | 0.15 | 0.067 | - |

- |

0.19 |

- |

- |

| NAPLES group |

0.011 |

1.3 (0.9-1.9) | 0.13 | <0.001 | 2.5 (1.4-4.3) |

0.001 |

0.001 |

3.5 (1.6-7.9) |

0.002 |

| Before matching | After matching | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naples group 0-1 | Naples group 2 | p-value | Standardized difference | Naples group 0-1 | Naples group 2 | p-value | Standardized difference | |

| Gender male, n(%) | 102 (58.6) | 66 (76.7) | 0.004 | 0.39 | 59 (76.6) | 57 (74.0) | 0.71 | 0.06 |

| Age>72 years, n(%) | 71 (40.8) | 47 (54.7) | 0.035 | 0.28 | 39 (50.6) | 38 (49.4) | 0.87 | 0.02 |

| Smoker (former or current), n(%) | 143 (82.2) | 80 (93.0) | 0.019 | 0.33 | 71 (92.2) | 71 (92.2) | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Type of resection, n(%) | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.57 | 0.09 | ||||

| Sublobar | 36 (20.7) | 25 (29.1) | 17 (22.1) | 20 (26.0) | ||||

| Major | 138 (79.3) | 61 (70.9) | 60 (77.9) | 57 (74.0) | ||||

| pT, n(%) | 0.008 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| T1 | 87 (50.0) | 28 (32.6) | 25 (32.5) | 25 (32.5) | ||||

| T2-T3-T4 | 87 (50.0) | 58 (67.4) | 52 (67.5) | 52 (67.5) | ||||

| pN, n(%) | 0.77 | 0.04 | 0.52 | 0.10 | ||||

| N0 | 141 (81.0) | 71 (82.6) | 62 (80.5) | 65 (84.4) | ||||

| N1-N2 | 33 (19.0) | 15 (17.4) | 15 (19.5) | 12 (15.6) | ||||

| Histology, n(%) | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.86 | 0.02 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 126 (72.4) | 58 (67.4) | 54 (70.1) | 53 (68.8) | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 48 (27.6) | 28 (32.6) | 23 (29.9) | 24 (31.2) | ||||

| Disease Free Survival | Overall Survival | Cancer related Survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

| p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|

Age (≤ 72 vs > 72) years |

0.11 |

- |

- | 0.78 | - |

- |

0.80 |

- |

- |

|

Gender (M vs F) |

0.42 |

- |

- | 0.77 | - |

- |

0.50 |

- |

- |

| Smoking history (never vs former/current) | 0.59 | - | - | 0.64 | - |

- |

0.60 |

- |

- |

| Surgical procedure (major vs sublobar) | 0.013 | 2.1 (1.2-3.6) | 0.006 | 0.72 | - |

- |

0.76 |

- |

- |

| Side of surgery (right vs left) | 0.53 | - | - | 0.81 | - |

- |

0.93 |

- |

- |

| Lobe (upper and middle vs lower) | 0.68 | - | - | 0.12 | - |

- |

0.24 |

- |

- |

| pT (1 vs 2-3-4) |

0.011 |

2.3 (1.3-4.4) |

0.007 | 0.008 | 5.2 (1.6-17.0) |

0.007 |

0.046 |

7.0 (0.9-53.7) |

0.061 |

| pN (0 vs 1-2) | 0.31 | - | - | 0.077 | - |

- |

0.027 |

2.7 (0.9-7.4) |

0.061 |

| Histology (adenocarcinoma vs squamous) | 0.26 | - | - | 0.99 | - |

- |

0.84 |

- |

- |

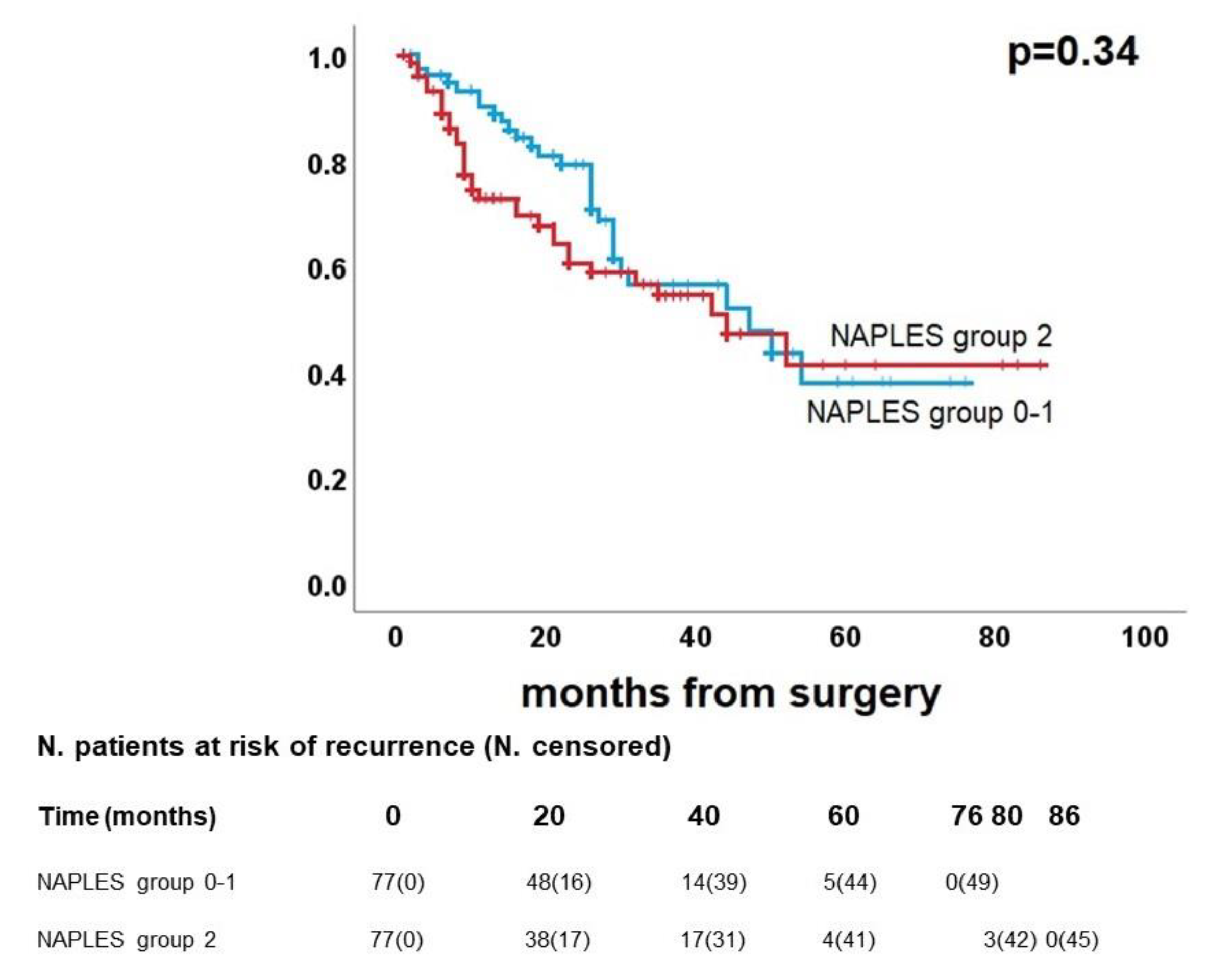

| NAPLES group (0-1 vs 2) |

0.34 |

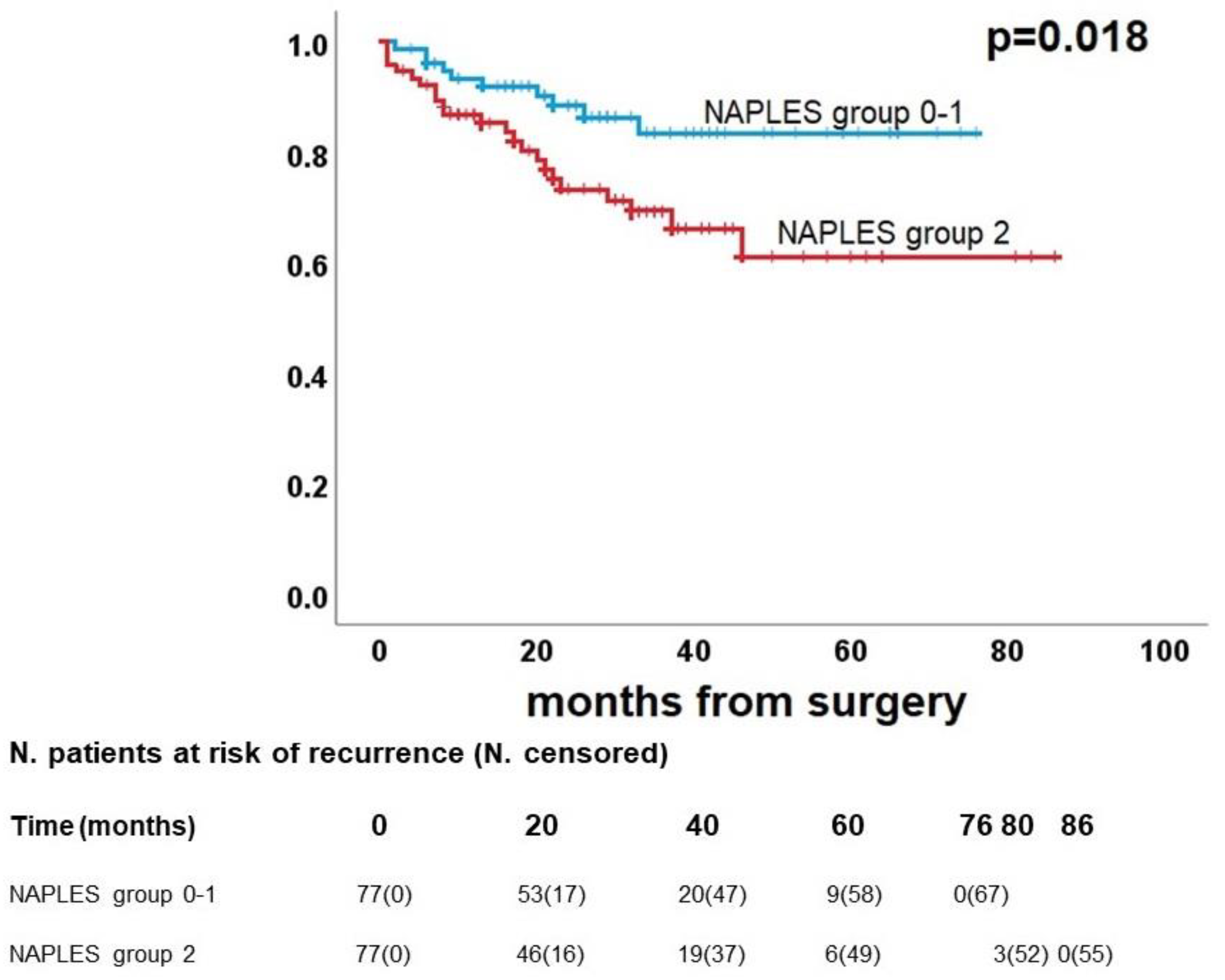

- | - | 0.023 | 2.5 (1.2-5.2) |

0.018 |

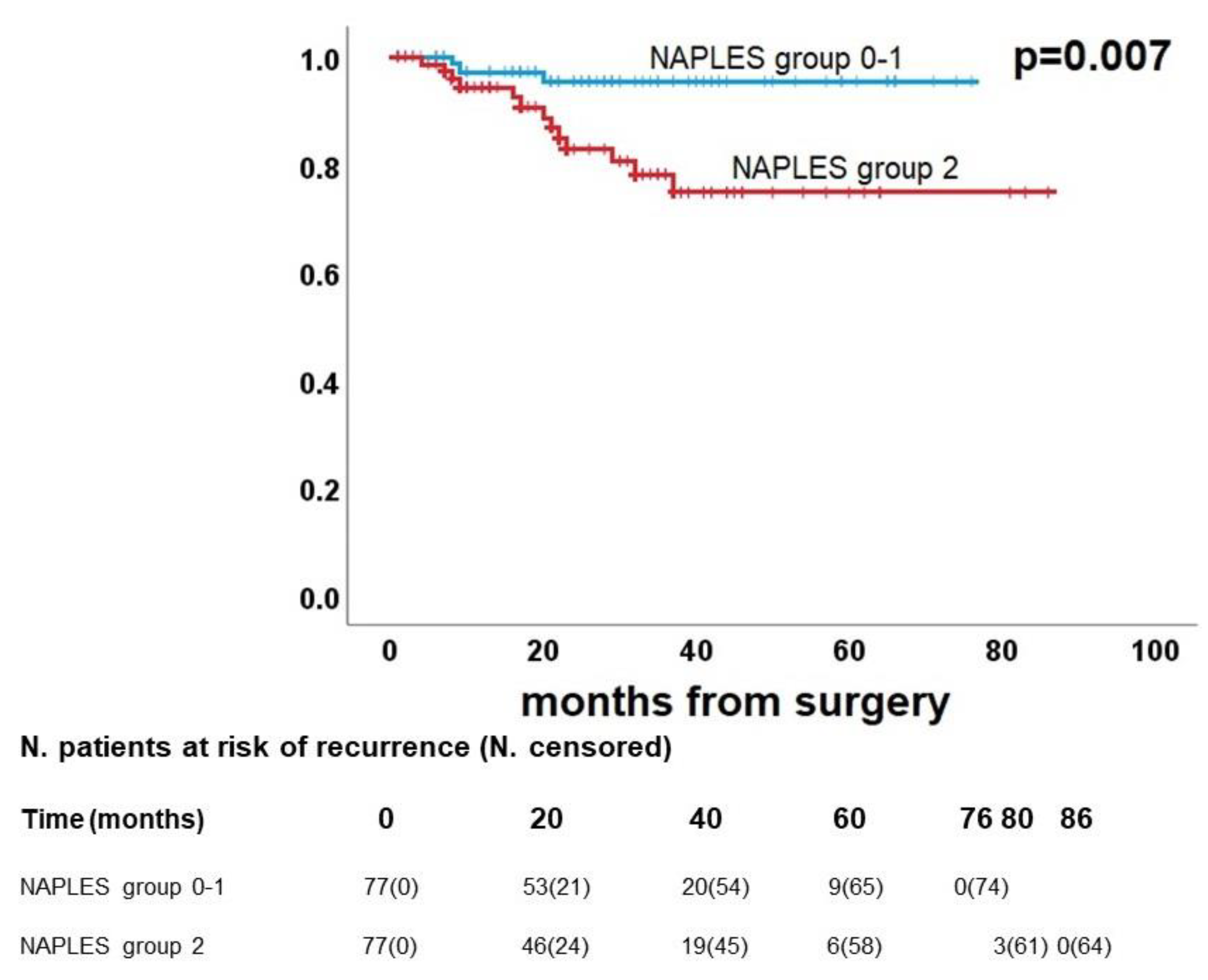

0.015 |

5.2 (1.5-18.2) |

0.010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).