Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Treatment Regimens and Efficacy Assessment

2.4. Follow-up and Endpoints

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics and Efficacy

3.2. Optimal Cutoff

3.3. Survival Analysis

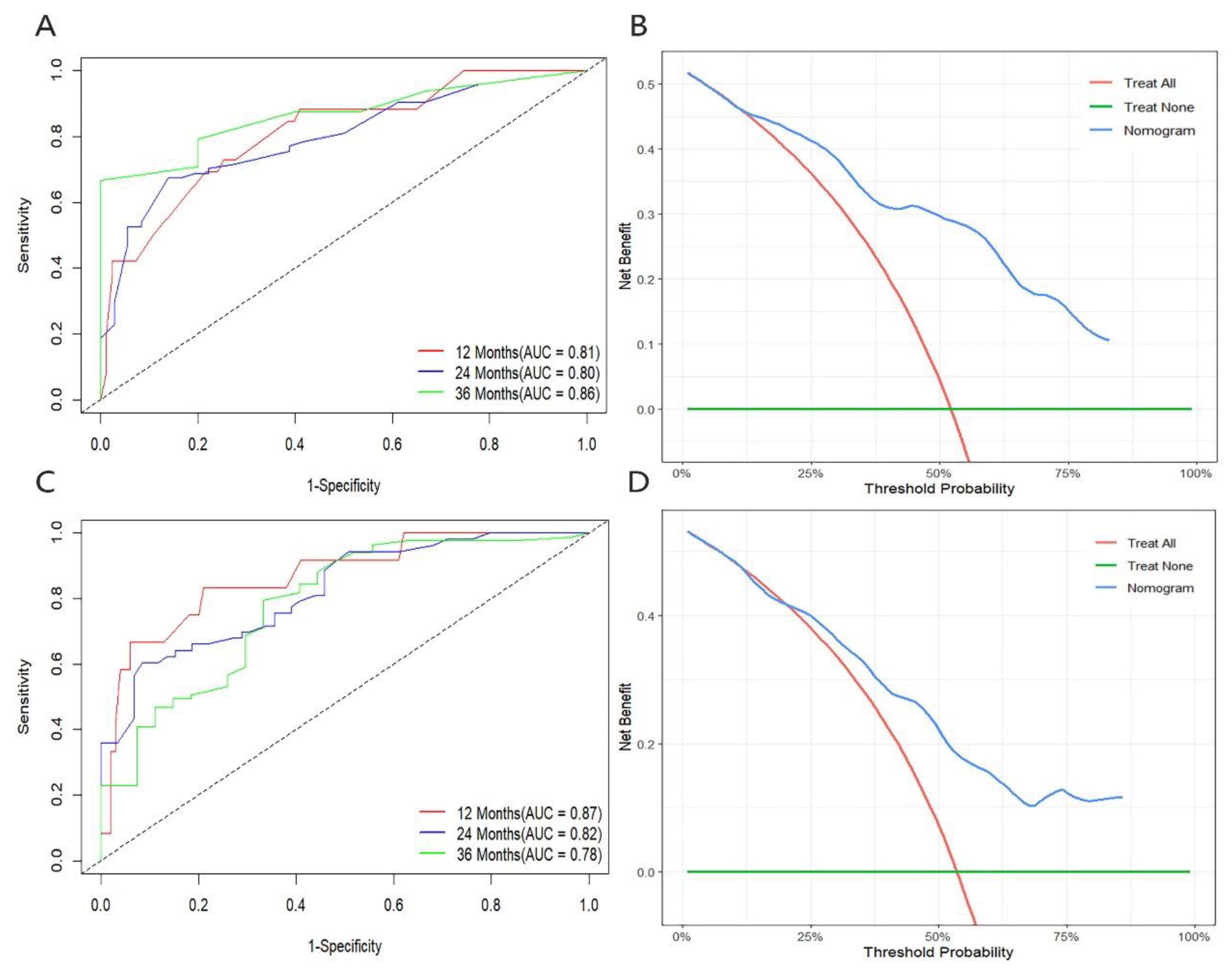

3.4. Development and Validation of Nomogram Prediction Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NSCLC Non-small cell lung cancer |

| CIT Chemoimmunotherapy |

| LDH Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| LAC Lactate |

| UA Uric acid |

| ALB Albumin |

| TG Triglycerides |

| TC Total cholesterol |

| BMI Body Mass Index |

| R Responders |

| NR Non-responder |

| PFS Progression-free survival |

| OS Overall survival |

| C-index Concordance index |

| DCA Decision curve analysis |

| AUC Area Under the Curve |

| RECIST Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors |

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024; 74: 229-263. [CrossRef]

- Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature 2018; 553: 446-454. [CrossRef]

- Zhou C, Wang Z, Sun Y et al. Sugemalimab versus placebo, in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy, as first-line treatment of metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (GEMSTONE-302): interim and final analyses of a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet Oncol 2022; 23: 220-233. [CrossRef]

- Garassino MC, Gadgeel S, Speranza G et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum in Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes From the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 Study. J Clin Oncol 2023; 41: 1992-1998. [CrossRef]

- Zhou C, Chen G, Huang Y et al. Camrelizumab plus carboplatin and pemetrexed versus chemotherapy alone in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CameL): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 305-314. [CrossRef]

- Ren S, Chen J, Xu X et al. Camrelizumab Plus Carboplatin and Paclitaxel as First-Line Treatment for Advanced Squamous NSCLC (CameL-Sq): A Phase 3 Trial. J Thorac Oncol 2022; 17: 544-557. [CrossRef]

- Holder AM, Dedeilia A, Sierra-Davidson K et al. Defining clinically useful biomarkers of immune checkpoint inhibitors in solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer 2024; 24: 498-512. [CrossRef]

- De Martino M, Rathmell JC, Galluzzi L, Vanpouille-Box C. Cancer cell metabolism and antitumour immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2024; 24: 654-669. [CrossRef]

- Chen D, Liu P, Lu X et al. Pan-cancer analysis implicates novel insights of lactate metabolism into immunotherapy response prediction and survival prognostication. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2024; 43: 125. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Shi D, Guo C et al. Can uric acid affect the immune microenvironment in bladder cancer? A single-center multi-omics study. Mol Carcinog 2024; 63: 461-478. [CrossRef]

- Zheng L, Hu F, Huang L et al. Association of metabolomics with PD-1 inhibitor plus chemotherapy outcomes in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer 2024; 12. [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 228-247. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 2078-2092. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Bai H, Wang C et al. Efficacy and Safety of First-Line Immunotherapy Combinations for Advanced NSCLC: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2021; 16: 1099-1117. [CrossRef]

- Trefny MP, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L, Kobold S. Metabolites as agents and targets for cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chang CH, Qiu J, O’Sullivan D et al. Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell 2015; 162: 1229-1241. [CrossRef]

- Osataphan S, Awidi M, Jan YJ et al. Association between higher glucose levels and reduced survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lung Cancer 2024; 198: 108023. [CrossRef]

- Kumagai S, Koyama S, Itahashi K et al. Lactic acid promotes PD-1 expression in regulatory T cells in highly glycolytic tumor microenvironments. Cancer Cell 2022; 40: 201-218.e209. [CrossRef]

- Wang JX, Choi SYC, Niu X et al. Lactic Acid and an Acidic Tumor Microenvironment suppress Anticancer Immunity. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Wu J, Zhai L et al. Metabolic regulation of homologous recombination repair by MRE11 lactylation. Cell 2024; 187: 294-311.e221. [CrossRef]

- Claps G, Faouzi S, Quidville V et al. The multiple roles of LDH in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022; 19: 749-762.

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022; 12: 31-46.

- Sung M, Jang WS, Kim HR et al. Prognostic value of baseline and early treatment response of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, C-reactive protein, and lactate dehydrogenase in non-small cell lung cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2023; 12: 1506-1516. [CrossRef]

- Tjokrowidjaja A, Lord SJ, John T et al. Pre- and on-treatment lactate dehydrogenase as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in advanced non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer 2022; 128: 1574-1583. [CrossRef]

- Allegrini S, Garcia-Gil M, Pesi R et al. The Good, the Bad and the New about Uric Acid in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022; 14. [CrossRef]

- Mi S, Gong L, Sui Z. Friend or Foe? An Unrecognized Role of Uric Acid in Cancer Development and the Potential Anticancer Effects of Uric Acid-lowering Drugs. J Cancer 2020; 11: 5236-5244. [CrossRef]

- Rao H, Wang Q, Zeng X et al. Analysis of the prognostic value of uric acid on the efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with primary liver cancer. Clin Transl Oncol 2024; 26: 774-785. [CrossRef]

- Shao Z, Xu Y, Zhang X et al. Changes in serum uric acid, serum uric acid/serum creatinine ratio, and gamma-glutamyltransferase might predict the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Strahlenther Onkol 2024; 200: 523-534. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Shan D, Dong Y et al. Correlation analysis of serum cystatin C, uric acid and lactate dehydrogenase levels before chemotherapy on the prognosis of small-cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett 2021; 21: 73.

- Jin HR, Wang J, Wang ZJ et al. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor microenvironment: from mechanisms to therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol 2023; 16: 103. [CrossRef]

- Jiang H, Li XS, Yang Y, Qi RX. Plasma lipidomics profiling in predicting the chemo-immunotherapy response in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol 2024; 14: 1348164. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Ma C, Yuan X et al. Preoperative Serum Triglyceride to High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Ratio Can Predict Prognosis in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Curr Oncol 2022; 29: 6125-6136. [CrossRef]

- Yildirim S, Dogan A, Akdag G et al. A Novel Prognostic Indicator for Immunotherapy Response: Lymphocyte-to-Albumin (LA) Ratio Predicts Survival in Metastatic NSCLC Patients. Cancers (Basel) 2024; 16. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald M, Poei D, Leyba A et al. Real world prognostic utility of platelet lymphocyte ratio and nutritional status in first-line immunotherapy response in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Treat Res Commun 2023; 36: 100752. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total n(%) /?x±s |

R n(%) /?x±s |

NR n(%) /?x±s |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 0.588 | |||

| <60 | 46(41.07) | 24(43.60) | 22(38.60) | |

| ≥60 | 66(58.93) | 31(56.40) | 35(61.40) | |

| Sex | 0.643 | |||

| Male | 96(85.71) | 48(87.30) | 48(84.20) | |

| Female | 16(14.29) | 7(12.70) | 9(15.80) | |

| ECOG PS | 0.159 | |||

| 1 | 55(49.11) | 31(56.40) | 24(42.10) | |

| 2 | 57(50.89) | 24(43.60) | 33(57.90) | |

| Diabetes | 0.038 | |||

| No | 84(75.00) | 46(83.60) | 38(66.70) | |

| Yes | 28(25.00) | 9(26.40) | 19(33.30) | |

| Hypertension | 0.917 | |||

| No | 83(74.11) | 41(74.50) | 42(73.70) | |

| Yes | 29(25.89) | 14(25.50) | 15(26.30) | |

| Smoking status | 0.656 | |||

| Non-smoker | 41(36.61) | 19(34.50) | 22(38.60) | |

| Smoker | 71(63.39) | 36(65.50) | 35(61.40) | |

| Histology | 0.183 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 54(48.21) | 23(41.80) | 31(54.40) | |

| Squamous carcinoma | 58(51.79) | 32(58.20) | 26(45.60) | |

| T stage | 0.925 | |||

| T1-2 | 31(27.68) | 15(27.30) | 16(28.10) | |

| T3-4 | 81(72.32) | 40(72.70) | 41(71.90) | |

| Lymphatic metastasis | 0.144 | |||

| No | 18(16.07) | 6(10.90) | 12(21.10) | |

| Yes | 94(83.93) | 49(89.10) | 45(78.90) | |

| Metastatic sites | 0.281 | |||

| No | 32(28.57) | 17(30.90) | 15(26.30) | |

| Viscera | 51(45.54) | 21(38.20) | 30(52.60) | |

| Bone | 29(25.89) | 17(30.90) | 12(21.10) | |

| TNM stage | 0.862 | |||

| ШC | 32(28.57) | 17(30.90) | 15(26.30) | |

| ⅣA | 27(24.11) | 13(23.60) | 14(24.60) | |

| ⅣB | 53(47.32) | 25(45.50) | 28(49.10) | |

| PD-L1 (%) | 0.000 | |||

| <1 | 31(27.68) | 9(16.40) | 22(40.00) | |

| 1-49 | 45 (40.08) | 18(32.70) | 27(49.10) | |

| ≥50 | 34(32.14) | 28(50.90) | 6(10.90) | |

| PD-1 inhibitor | 0.897 | |||

| Pembrolizumab | 29(25.89) | 15(27.30) | 14(24.60) | |

| Sintilimab | 41(36.61) | 19(34.50) | 22(38.60) | |

| Tisleizumab | 42(37.50) | 21(38.20) | 21(36.80) | |

| BMI(Kg/m2) | 23.22±3.51 | 23.66±3.89 | 22.79±3.06 | 0.189 |

| NLR | 6.67±6.95 | 6.25±6.88 | 7.066±7.06 | 0.682 |

| MONO(109/L) | 0.61±0.27 | 0.57±0.26 | 0.65±0.28 | 0.140 |

| Hb(g/L) | 121.12±18.95 | 123.36±22.27 | 118.95±14.96 | 0.219 |

| LDH(U/L) | 230.66±94.74 | 212.69±97.88 | 248.01±89.05 | 0.048 |

| LAC(mmol/L) | 2.99±1.19 | 2.77±1.06 | 3.22±1.26 | 0.045 |

| UA(umol/L) | 356.93±90.15 | 338.85±73.52 | 374.37±101.33 | 0.037 |

| TG(mmol/L) | 2.14±1.46 | 1.85±1.18 | 2.41±1.66 | 0.039 |

| TC(mmol/L) | 4.65±1.35 | 4.55±1.32 | 4.75±1.38 | 0.435 |

| ALB(g/L) | 37.75±6.12 | 37.67±5.65 | 34.99±6.31 | 0.019 |

|

Variables |

Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | |||

| Age(years) <60 vs ≥60 |

0.872 | 0.592-1.284 | 0.487 | |||||

| Sex Male vs Female |

1.097 | 0.634-1.897 | 0.742 | |||||

| ECOG PS 1 vs 2 |

0.972 | 0.661-1.428 | 0.883 | |||||

| Smoking status Non-smoker vs smoker |

1.113 | 0.748-1.657 | 0.596 | |||||

| Diabetes No vs Yes |

0.793 | 0.507-1.239 | 0.309 | 0.785 | 0.462-1.333 | 0.370 | ||

| Hypertension No vs Yes |

0.781 | 0.503-1.213 | 0.271 | |||||

| Histology Adeno vs Squamous |

0.978 | 0.665-1.437 | 0.909 | |||||

| PD-L1(%) <50 vs ≥50 |

1.338 | 0.902-1.985 | 0.148 | 1.355 | 0.859-2.139 | 0.192 | ||

| TNM stage Ⅲ vs Ⅳ |

0.771 | 0.524-1.135 | 0.187 | 0.574 | 0.336-0.981 | 0.042 | ||

| Metastasis No vs Yes |

0.922 | 0.545-1. 561 | 0.907 | 1.541 | 0.862-2.753 | 0.145 | ||

| BMI(Kg/m2) <21 vs ≥21 |

1.532 | 1.004-2.338 | 0.048 | 1.385 | 0.896-2.140 | 0.143 | ||

| NL <3.2 vs ≥3.2 |

0.678 | 0.449-1.024 | 0.065 | 0.800 | 0.517-1.237 | 0.316 | ||

| MONO(109/L) <0.7 vs ≥0.7 |

0.609 | 0.398-0.931 | 0.022 | 0.673 | 0.424-1.070 | 0.094 | ||

| Hb(g/L) <112 vs ≥112 |

1.582 | 1.043-2.400 | 0.031 | 1.477 | 0.912-2.391 | 0.113 | ||

| LDH(U/L) <193 vs ≥193 |

0.340 | 0.221-0.524 | 0.000 | 0.418 | 0.259-0.674 | 0.000 | ||

| LAC(mmol/L) <2.5 vs ≥2.5 |

0.372 | 0.242-0.571 | 0.000 | 0.434 | 0.259-0.725 | 0.001 | ||

| UA(umol/L) <430 vs ≥430 |

0.465 | 0.296-0.731 | 0.001 | 0.471 | 0.286-0.774 | 0.003 | ||

| TG(mmol/L) <3.5 vs ≥3.5 |

0.606 | 0.377-0.976 | 0.032 | 0.552 | 0.331-0.921 | 0.023 | ||

| ALB(g/L) <36 vs ≥36 |

1.670 | 1.122-2.486 | 0.012 | 1.124 | 0.709-1.781 | 0.145 | ||

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | ||

| Age(years) <60 vs ≥60 |

0;682 | 0.458-1.016 | 0.060 | ||||

| Sex Male vs Female |

1.094 | 0.631-1.896 | 0.749 | ||||

| ECOG PS 1 vs 2 |

0.109 | 0.490-1.075 | 0.109 | ||||

| Smoking status No vs Yes |

0.880 | 0.584-1.326 | 0.542 | ||||

| Diabetes No vs Yes |

1.034 | 0.647-1.651 | 0.890 | ||||

| Hypertension No vs Yes |

0.695 | 0.445-1.087 | 0.111 | ||||

| Histology Adeno vs Squamous |

0.939 | 0.686-1.504 | 0.939 | ||||

| PD-L1(%) <50 vs ≥50 |

1.561 | 1.038-2.345 | 0.032 | 1.442 | 0.911-2.283 | 0.118 | |

| Clinical stage Ⅲ vs Ⅳ |

0.806 | 0.544-1.184 | 0.283 | 0.449 | 0.240-0.840 | 0.012 | |

| Metastasis No vs Yes |

1.042 | 0.603-1.798 | 0.301 | 2.564 | 1.069-6.154 | 0.035 | |

| BMI(Kg/m2) <21 vs ≥21 |

1.530 | 1.002-2.335 | 0.042 | 1.656 | 1.048-2.617 | 0.031 | |

| NL <2.9 vs ≥2.9 |

0.577 | 0.360-0.927 | 0.023 | 0.699 | 0.424-1.151 | 0.159 | |

| MONO(109/L) <0.7 vs ≥0.7 |

0.570 | 0.370-0.880 | 0.011 | 0.643 | 0.398-1.037 | 0.070 | |

| Hb(g/L) <114 vs ≥114 |

1.777 | 1.183-2.668 | 0.006 | 1.450 | 0.922-2.281 | 0.107 | |

| LDH(U/L) <208 vs ≥208 |

0.380 | 0.249-0.582 | 0.000 | 0.579 | 0.366-0.917 | 0.020 | |

| LAC(mmol/L) <2.5 vs ≥2.5 |

0.415 | 0.267-0.643 | 0.000 | 0.504 | 0.310-0.820 | 0.006 | |

| UA(umol/L) <430 vs ≥430 |

0.491 | 0.309-0.781 | 0.002 | 0.442 | 0.264-0.737 | 0.002 | |

| TG(mmol/L) <3.5 vs ≥3.5 |

0.584 | 0.362-0.941 | 0.022 | 0.540 | 0.320-0.912 | 0.021 | |

| ALB(g/L) <36 vs ≥36 |

2.060 | 1.374-3.090 | 0.000 | 0.449 | 0.240-0.840 | 0.039 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).