Submitted:

15 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

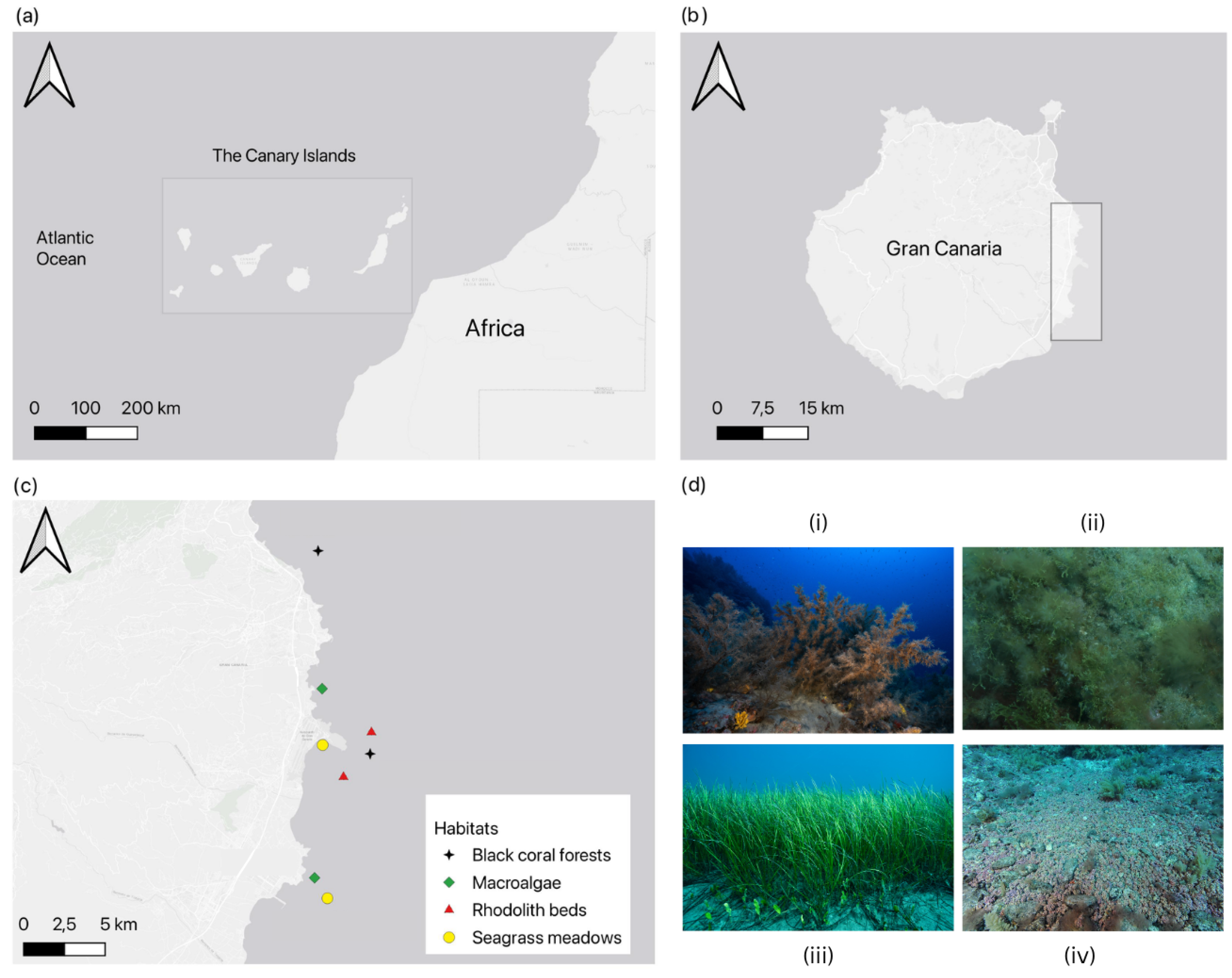

2.1. Study Region

2.2. Sampling Design and Specimen Processing

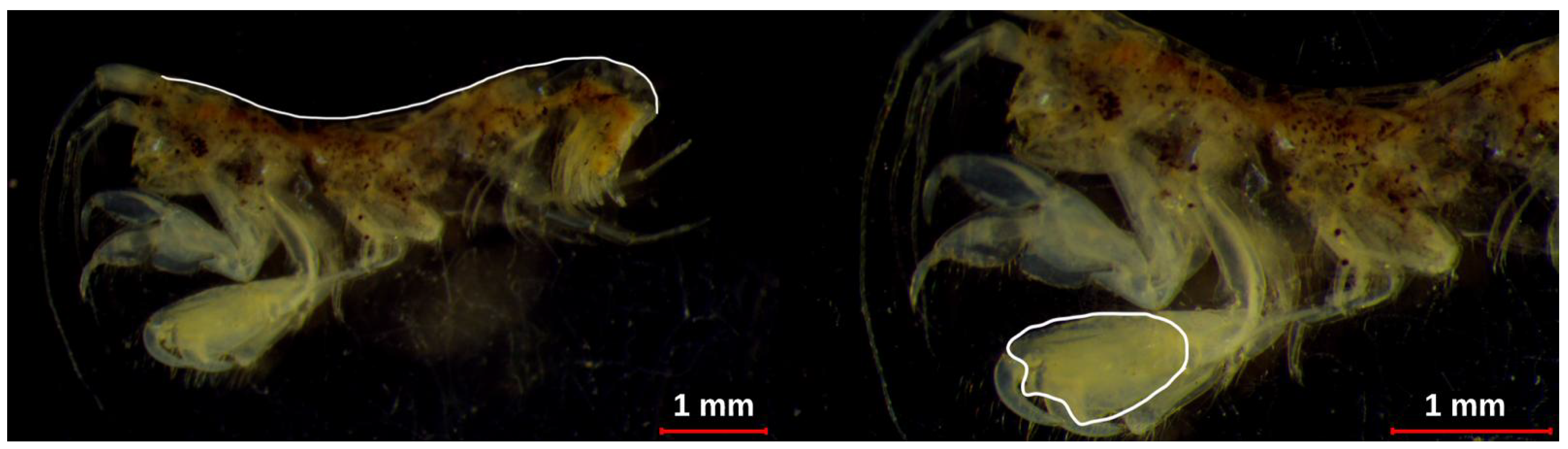

2.3. Morphometric Measurements

2.4. Data Analysis

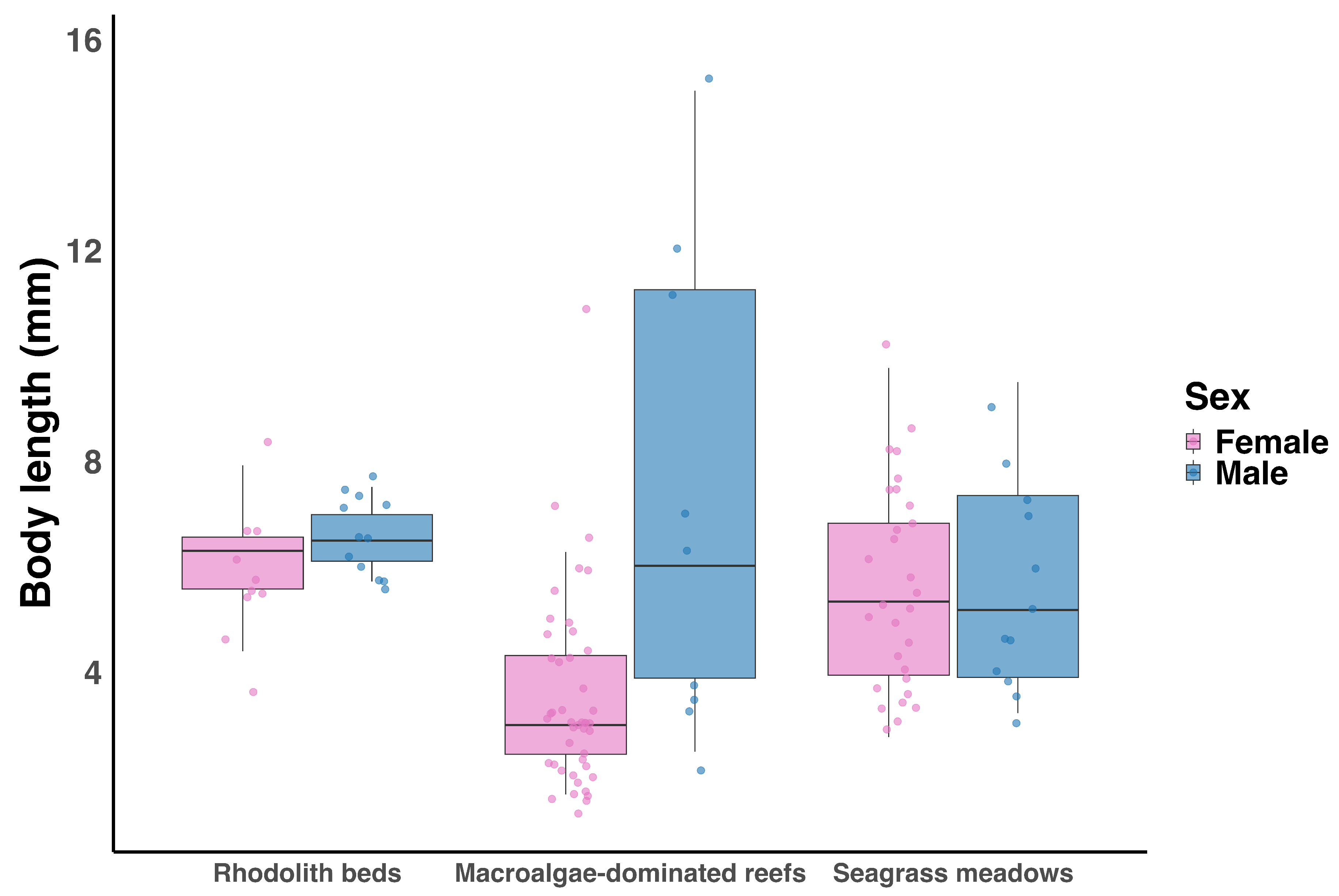

3. Results

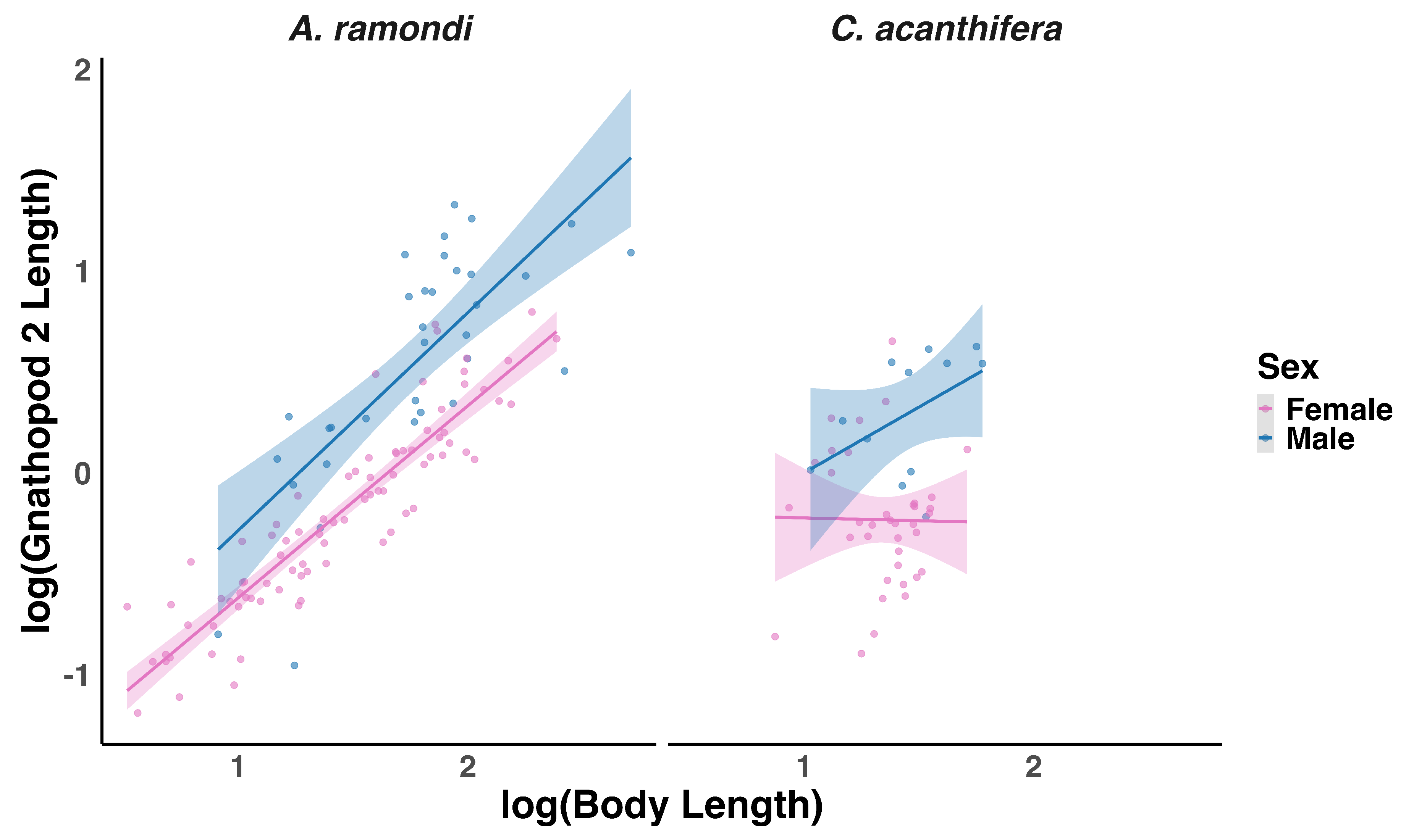

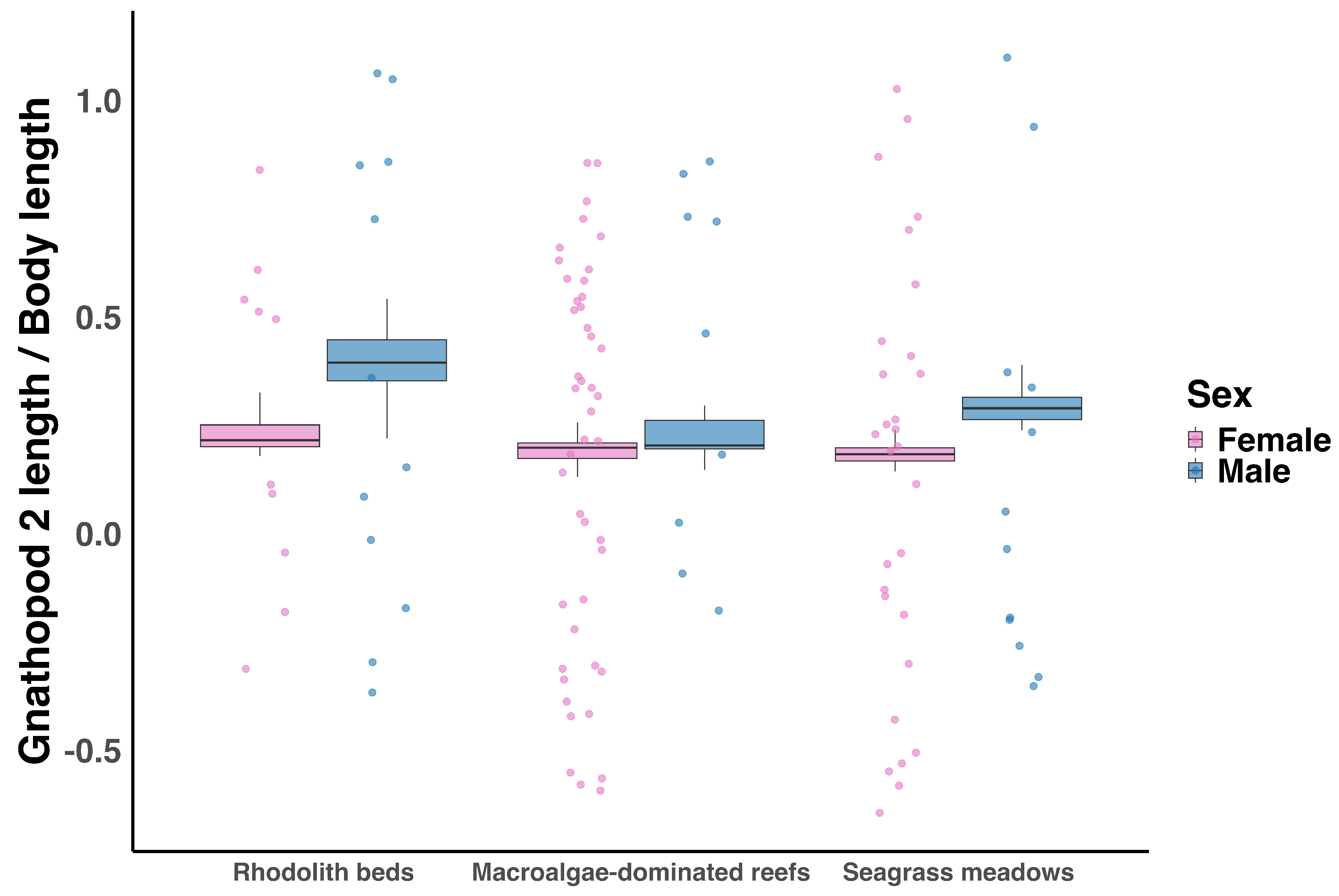

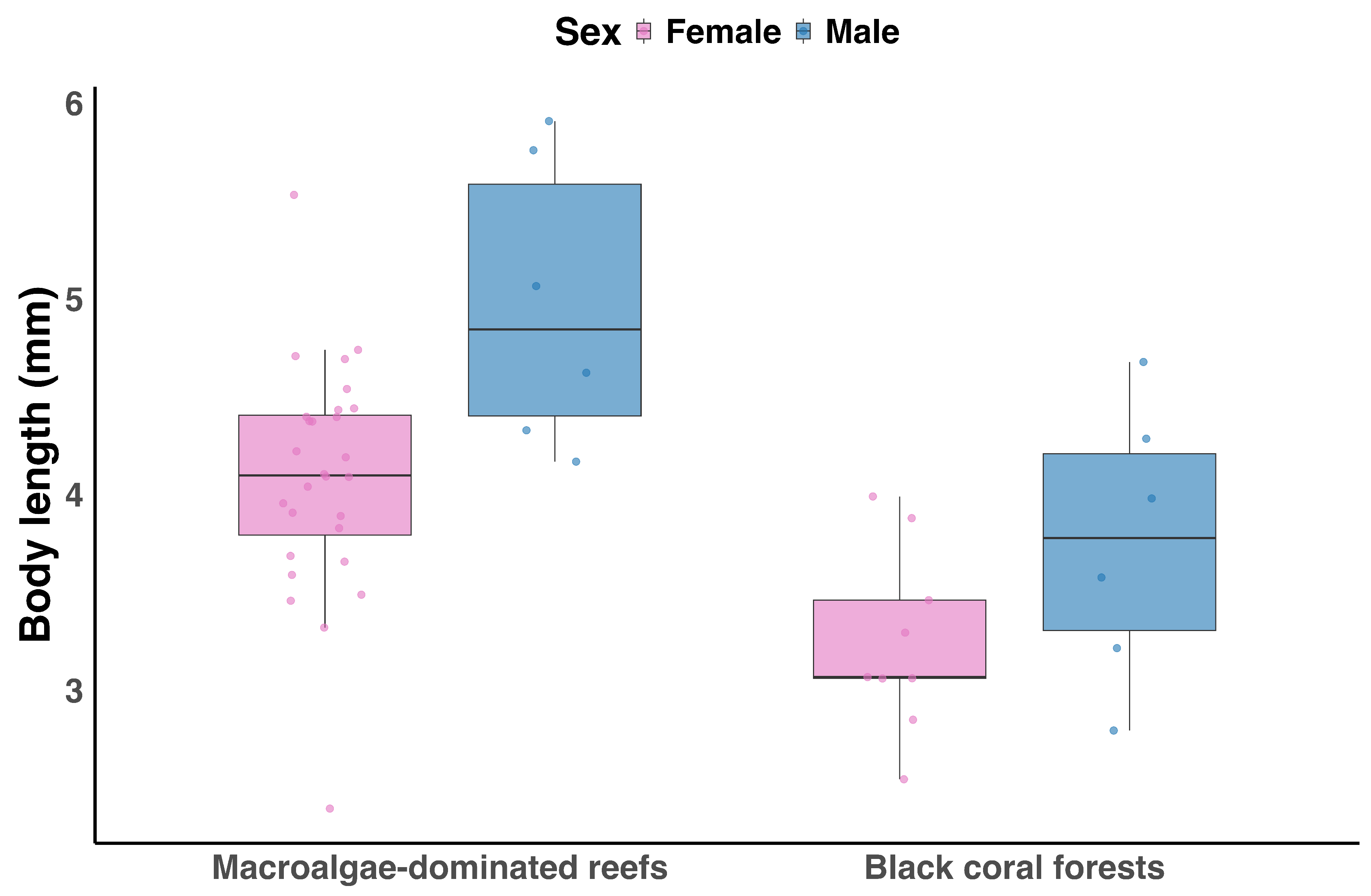

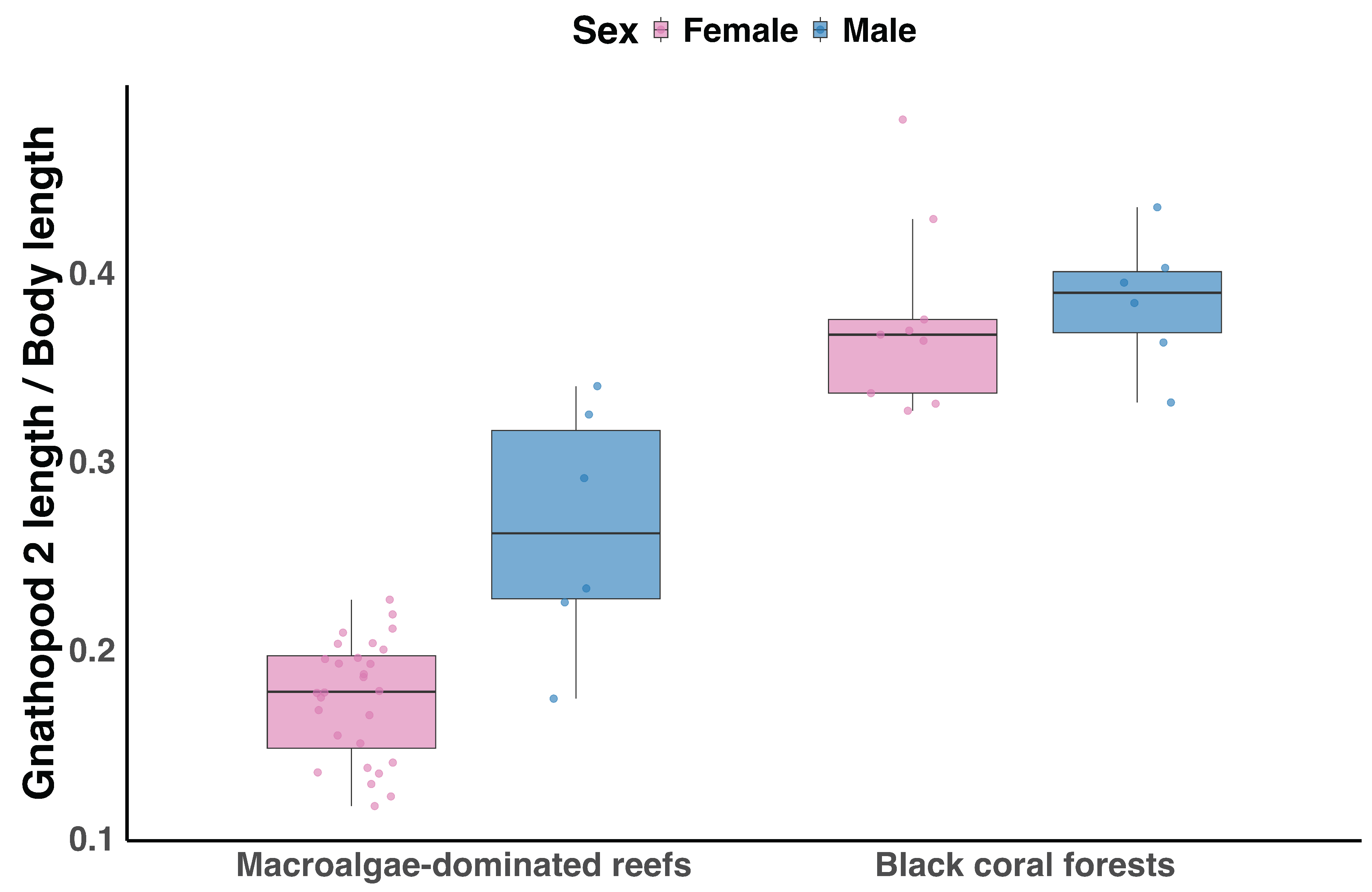

3.1. Sex-Specific Allometry Comparisons

3.2. Species-Specific Models

3.2.1. Ampithoe ramondi

3.2.2. Caprella acanthifera

4. Discussion

4.1. Sexual Selection, Trait Scaling, and Ecological Modulation

4.2. Ecological Complexity and Habitat Structure

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shine, R. Ecological causes for the evolution of sexual dimorphism: A review of the evidence. The Quarterly Review of Biology 1989, 64, 419–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M. Sexual selection; Princeton University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stillwell, R.C.; Blanckenhorn, W.U.; Teder, T.; Davidowitz, G.; Fox, C.W. Sex differences in phenotypic plasticity affect variation in sexual size dimorphism in insects: From physiology to evolution. Annual Review of Entomology 2010, 55, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, J.A. Signals, signal conditions, and the direction of evolution. American Naturalist 1992, 139, S125–S153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutton-Brock, T. Sexual selection in males and females. Science 2007, 318, 1882–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex; John Murray, 1871; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lande, R. Sexual dimorphism, sexual selection, and adaptation in polygenic characters. Evolution 1980, 34, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.M. Evolution of sexual dimorphism in body weight in platyrrhines. American Journal of Primatology 1994, 34, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, V.; Bayer, M. Sexual dimorphism in the Cervidae and its relation to habitat. Journal of Zoology 1988, 214, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleasby, I.R.; Wakefield, E.D.; Bodey, T.W.; Davies, R.D.; Patrick, S.C.; Newton, J.; Votier, S.C.; Bearhop, S.; et al. Sexual segregation in a wide-ranging marine predator is a consequence of habitat selection. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2015, 518, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losos, J.B.; Butler, M. Sexual Dimorphism in Body Size and Shape in Relation to Habitat Use among. Lizard social behavior 2003, 356. [Google Scholar]

- Wikelski, M.; Trillmich, F. Body size and sexual size dimorphism in marine iguanas fluctuate as a result of opposing natural and sexual selection: An island comparison. Evolution 1997, 51, 922–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfianti, T.; Wilson, S.; Costello, M.J. Progress in the discovery of amphipod crustaceans. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, T.; De Broyer, C.; Bellan-Santini, D.; Coleman, C.O.; Copilaș-Ciocianu, D.; Corbari, L.; Daneliya, M.E.; Dauvin, J.C.; Decock, W.; Fanini, L.; et al. The World Amphipoda Database: History and progress. Australian Museum 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, J.K.; Myers, A.A. A phylogeny and classification of the Amphipoda with the establishment of the new order Ingolfiellida (Crustacea: Peracarida). Zootaxa 2017, 4265, 1–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Mayoral, S.; Díaz-Vergara, S.; Bosch, N.E.; Tuya, F.; Bramanti, L.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, V.; Terrana, L.; Espino, F.; Haroun, R.; Otero-Ferrer, F. Inside the mesophotic zone: Taxonomic and trait diversity of epifauna associated with black coral forests across an oceanic archipelago. Coral Reefs 2025, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Copilaș-Ciocianu, D.; Boros, B.V.; Šidagytė-Copilas, E. Morphology mirrors trophic niche in a freshwater amphipod community. Freshwater Biology 2021, 66, 1968–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, K.D.; Elwood, R.W.; Dick, J.T.; Morrison, J. Sexual dimorphism in amphipods: The role of male posterior gnathopods revealed in Gammarus pulex. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2005, 58, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emlen, D.J. The evolution of animal weapons. Annual review of ecology, evolution, and systematics 2008, 39, 387–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellborn, G.A. Selection on a sexually dimorphic trait in ecotypes within the Hyalella azteca species complex (Amphipoda: Hyalellidae). The American Midland Naturalist 2000, 143, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutton-Brock, T. The functions of antlers. Behaviour 1982, 79, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellborn, G.A. Trade-off between competitive ability and antipredator adaptation in a freshwater amphipod species complex. Ecology 2002, 83, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellborn, G.A.; Bartholf, S.E. Ecological context and the importance of body and gnathopod size for pairing success in two amphipod ecomorphs. Oecologia 2005, 143, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolnick, D.I.; Svanbäck, R.; Fordyce, J.A.; Yang, L.H.; Davis, J.M.; Hulsey, C.D.; Forister, M.L. The ecology of individuals: Incidence and implications of individual specialization. The American Naturalist 2003, 161, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Mayoral, S.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, V.; Otero-Ferrer, F.; Tuya, F. Spatio-temporal variability of amphipod assemblages associated with rhodolith seabeds. Marine and Freshwater Research 2020, 72, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Mayoral, S.; Tuya, F.; Prado, P.; Marco-Méndez, C.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, V.; Fernández-Torquemada, Y.; Espino, F.; de la Ossa, J.A.; Vilella, D.M.; Machado, M.; et al. Drivers of variation in seagrass-associated amphipods across biogeographical areas. Marine Environmental Research 2023, 186, 105918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; et al. Introducción a las islas. Ecología Insular/Island Ecology 2004, 21–55. [Google Scholar]

- Premate, E.; Fišer, Ž.; Biró, A.; Copilaş-Ciocianu, D.; Fromhage, L.; Jennions, M.; Borko, Š.; Herczeg, G.; Balázs, G.; Kralj-Fišer, S.; et al. Sexual dimorphism in subterranean amphipod crustaceans covaries with subterranean habitat type. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2024, 37, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, N.E.; Espino, F.; Tuya, F.; Haroun, R.; Bramanti, L.; Otero-Ferrer, F. Black coral forests enhance taxonomic and functional distinctiveness of mesophotic fishes in an oceanic island: Implications for biodiversity conservation. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 4963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Peris, I.; Navarro-Mayoral, S.; de Esteban, M.C.; Tuya, F.; Peña, V.; Barbara, I.; Neves, P.; Ribeiro, C.; Abreu, A.; Grall, J.; et al. Effect of depth across a latitudinal gradient in the structure of rhodolith seabeds and associated biota across the eastern Atlantic Ocean. Diversity 2023, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, B.; Hernández, J.C.; Sangil, C.; Martín, L.; Expósito, F.J.; Díaz, J.P.; Sansón, M. Fast climatic changes place an endemic Canary Island macroalga at extinction risk. Regional Environmental Change 2021, 21, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, C.; Tuya, F.; Boyra, A.; Sanchez-Jerez, P.; Blanch, I.; Haroun, R.J. Spatial variation in the structural parameters of Cymodocea nodosa seagrass meadows in the Canary Islands: A multiscaled approach. In Botanica marina (Print); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.G.; Lawton, J.H.; Shachak, M. Organisms as ecosystem engineers. In Ecosystem management: Selected readings; Springer, 1994; pp. 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- Feldens, P.; Held, P.; Otero-Ferrer, F.; Bramanti, L.; Espino, F.; Schneider von Deimling, J. Can black coral forests be detected using multibeam echosounder “multi-detect” data? Frontiers in Remote Sensing 2023, 4, 988366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez, V.; Navarro-Mayoral, S.; Sanchez-Jerez, P. Connectivity patterns for direct developing invertebrates in fragmented marine habitats: Fish farms fouling as source population in the establishment and maintenance of local metapopulations. Frontiers in Marine Science 2021, 8, 785260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Jackson, D.W.; Cooper, J.A.G.; Beyers, M.; Breen, C. Whole-island wind bifurcation and localized topographic steering: Impacts on aeolian dune dynamics. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 763, 144444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, J.; Arístegui, J.; Hernández-Hernández, N.; Fernández-Méndez, M.; Riebesell, U. Oligotrophic phytoplankton community effectively adjusts to artificial upwelling regardless of intensity, but differently among upwelling modes. Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9, 880550. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Mayoral, S.; Gouillieux, B.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, V.; Tuya, F.; Lecoquierre, N.; Bramanti, L.; Terrana, L.; Espino, F.; Flot, J.F.; Haroun, R.; et al. “Hidden” biodiversity: A new amphipod genus dominates epifauna in association with a mesophotic black coral forest. Coral Reefs 2024, 43, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.; Luck, D.G.; Toonen, R.J. The biology and ecology of black corals (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Hexacorallia: Antipatharia). Advances in Marine Biology 2012, 63, 67–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bellan-Santini, D.; Karaman, G.; Krapp-Schickel, G.; Ledoyer, M.; Myers, A.; Ruffo, S.; Schiecke, U. The Amphipoda of the Mediterranean. Part 1: Gammaridae (Acanthonotozomatidae to Gammaridae) 1982.

- Bellan-Santini, D.; Diviacco, G.; Krapp-Schickel, G.; Ruffo, S. The Amphipoda of the Mediterranean. Part 2. Gammaridea (Haustoriidae to Lysianassidae) 1989.

- Bellan-Santini, D.; Karaman, G.; Krapp-Schickel, G.; Ledoyer, M.; Ruffo, S. The amphipoda of the mediterranean. Part 3: Gammaridea (melphidippidae to talitridae), ingolfiellidea, caprellidea; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, F.M.; Lasenby, D.C. Seasonal trends in the head capsule length and body length/weight relationships of two amphipod species. Crustaceana 1998, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovich, J.E.; Gibbons, J.W. A review of techniques for quantifying sexual size dimorphism. Growth, Development, and Aging: GDA 1992, 56, 269–281. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2024.

- Brooks, M.E.; Kristensen, K.; van Benthem, K.J.; Magnusson, A.; Berg, C.W.; Nielsen, A.; Skaug, H.J.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.M. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. The R Journal 2017, 9, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, F. DHARMa: Residual diagnostics for hierarchical (multi-level / mixed) regression models, 2024. R package version 0.4.7.

- Lenth, R. emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means, 2025. R package version 1.11.1.

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis; Springer-Verlag, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Conlan, K.E. Precopulatory mating behavior and sexual dimorphism in the amphipod Crustacea. Hydrobiologia 1991, 223, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowsky, B.; Borowsky, R. The reproductive behaviors of the amphipod crustacean Gammarus palustris (Bousfield) and some insights into the nature of their stimuli. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 1987, 107, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazikalova, A.Y. Taxonomy, ecology, and distribution of genera Micruropus Stebbing and Pseudomicruropus nov. gen. (Amphipoda; Gammaridea). Tr. Limnol. Inst., Akad. Nauk SSSR, Sib. Otd 1962, 2, 3–140. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrito, A.; de Juan, S.; Hinz, H.; Maynou, F. Morphological insights into the three-dimensional complexity of rhodolith beds. Marine Biology 2024, 171, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippert, H.; Iken, K.; Rachor, E.; Wiencke, C. Macrofauna associated with macroalgae in the Kongsfjord (Spitsbergen). Polar Biology 2001, 24, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.R.; Stachowicz, J.J. Genetic diversity enhances the resistance of a seagrass ecosystem to disturbance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 8998–9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.P.; Jacobucci, G.B.; Leite, F.P.P. Title TBD. In press. 2025.

- Edgar, G.J.; Aoki, M. Resource limitation and fish predation: Their importance to mobile epifauna associated with Japanese Sargassum. Oecologia 1993, 95, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poore, A.G.; Campbell, A.H.; Coleman, R.A.; Edgar, G.J.; Jormalainen, V.; Reynolds, P.L.; Sotka, E.E.; Stachowicz, J.J.; Taylor, R.B.; Vanderklift, M.A.; et al. Global patterns in the impact of marine herbivores on benthic primary producers. Ecology letters 2012, 15, 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, F.P.P.; Tanaka, M.O.; Gebara, R.S. Structural variation in the brown alga Sargassum cymosum and its effects on associated amphipod assemblages. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2007, 67, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Rivera, E.; Hay, M.E. The effects of diet mixing on consumer fitness: Macroalgae, epiphytes, and animal matter as food for marine amphipods. Oecologia 2000, 123, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra-García, J.M.; Sánchez, J.A.; Ros, M. Distributional and ecological patterns of caprellids (Crustacea: Amphipoda) associated with the seaweed Stypocaulon scoparium in the Iberian Peninsula. Marine Biodiversity Records 2009, 2, e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, E.A. Reproductive behavior and sexual dimorphism of a caprellid amphipod. Journal of Crustacean Biology 1991, 11, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emlen, S.T.; Oring, L.W. Ecology, sexual selection, and the evolution of mating systems. Science 1977, 197, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewbel, G.S. Sexual dimorphism and intraspecific aggression, and their relationship to sex ratios in Caprella gorgonia Laubitz & Lewbel (Crustacea: Amphipoda: Caprellidae). Journal of experimental marine Biology and Ecology 1978, 33, 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, S.; Cedhagen, T. Aspects of the behaviour and ecology of Dyopedos monacanthus (Metzger) and D. porrectus Bate, with comparative notes on Dulichia tuberculata Boeck (Crustacea: Amphipoda: Podoceridae). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 1989, 127, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castejón-Silvo, I.; Jaume, D.; Terrados, J. Feeding preferences of amphipod crustaceans Ampithoe ramondi and Gammarella fucicola for Posidonia oceanica seeds and leaves. In CSIC-Instituto de Ciencias del Mar (ICM); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-García, J.M.; Martínez-Pita, I.; Pita, M.L. Fatty acid composition of the Caprellidea (Crustacea: Amphipoda) from the Strait of Gibraltar. Scientia Marina 2004, 68, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, L.N.; Dauby, P.; Gobert, S.; Graeve, M.; Nyssen, F.; Thelen, N.; Lepoint, G. Dominant amphipods of Posidonia oceanica seagrass meadows display considerable trophic diversity. Marine Ecology 2015, 36, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czechowska, K.; Feldens, P.; Tuya, F.; Cosme de Esteban, M.; Espino, F.; Haroun, R.; Otero-Ferrer, F. Testing side-scan sonar and multibeam echosounder to study black coral gardens: A case study from Macaronesia. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Bramanti, L.; Gori, A.; Orejas, C. An overview of the animal forests of the world. In Marine animal forests: The ecology of benthic biodiversity hotspots; Rossi, S., Bramanti, L., Gori, A., Orejas, C., Eds.; Springer, 2017; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Buhl-Mortensen, L.; Buhl-Mortensen, P.; Rungruangsak-Torrissen, K.; Schwach, V.; Hjort, J.; Jakobsen, T.; Toresen, R. Cold temperate coral habitats. Corals in a changing world 2018, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Janicke, T.; Morrow, E.H. Operational sex ratio predicts the opportunity and direction of sexual selection across animals. Ecology letters 2018, 21, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokko, H.; Jennions, M.D. Parental investment, sexual selection and sex ratios. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2008, 21, 919–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuya, F.; Png Gonzalez, L.; Riera, R.; Haroun, R.; Espino, F. Ecological structure and function differs between habitats dominated by seagrasses and green seaweeds. Marine Environmental Research 2014, 98, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuya, F.; Ribeiro-Leite, L.; Arto-Cuesta, N.; Coca, J.; Haroun, R.; Espino, F. Decadal changes in the structure of Cymodocea nodosa seagrass meadows: Natural vs. human influences. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2014, 137, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinossi-Allibert, I.; Rueffler, C.; Arnqvist, G.; Berger, D. The efficacy of good genes sexual selection under environmental change. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2019, 286, 20182313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainte-Marie, B. A review of the reproductive bionomics of aquatic gammaridean amphipods: Variation of life history traits with latitude, depth, salinity, and superfamily. Hydrobiologia 1991, 223, 189–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leber, K.M. The influence of predatory decapods, refuge, and microhabitat selection on seagrass communities. Ecology 1985, 66, 1951–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moksnes, P.O.; Gullström, M.; Tryman, K.; Baden, S. Trophic cascades in a temperate seagrass community. Oikos 2008, 117, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).