1. Introduction

The United Nations 2030 Agenda established Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG 2), which calls for a structural transformation of food systems to make them simultaneously more productive, resilient, and environmentally sustainable, capable of meeting the needs of a growing population without intensifying the degradation of natural resources [

1,

2]. However, according to The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture (SOLAW) report [

3], achieving this goal faces increasing obstacles, as pressure on land, soil, and water already imposes concrete limits on the expansion of agricultural production based on conventional practices. This scenario reinforces the need for integrated solutions that reconcile food security, environmental sustainability, and the demands associated with the energy transition.

In this context, the finite nature of land as a resource within food systems highlights an important trade-off associated with the expansion of energy infrastructure in agricultural areas. Although solar photovoltaic generation is widely recognized as a low-carbon alternative, its large-scale deployment has raised debates regarding the conversion of productive land for energy purposes, particularly in regions where the availability of fertile soil is already limited [

4]. As an alternative to this conflict, agrivoltaic (APV) technology emerges as an innovative solution by enabling shared land use, optimizing the simultaneous utilization of productive areas for both energy generation and agricultural production [

5].

Agrivoltaic systems are defined as productive arrangements that integrate, in a simultaneous and functional manner, solar photovoltaic energy generation and agricultural or livestock activities within the same area, with the aim of maximizing land-use efficiency and reducing conflicts between food and energy production [

6]. Recent evidence indicates that these systems can modify local microclimatic conditions, influencing radiation availability, temperature, and soil water dynamics, with direct effects on both agricultural performance and the energy efficiency of photovoltaic panels [

7].

In this context, the objective of this study is to analyze the recent scientific literature on agrivoltaic systems, identifying their main thematic axes, emerging trends, and research gaps.

2. Methodology

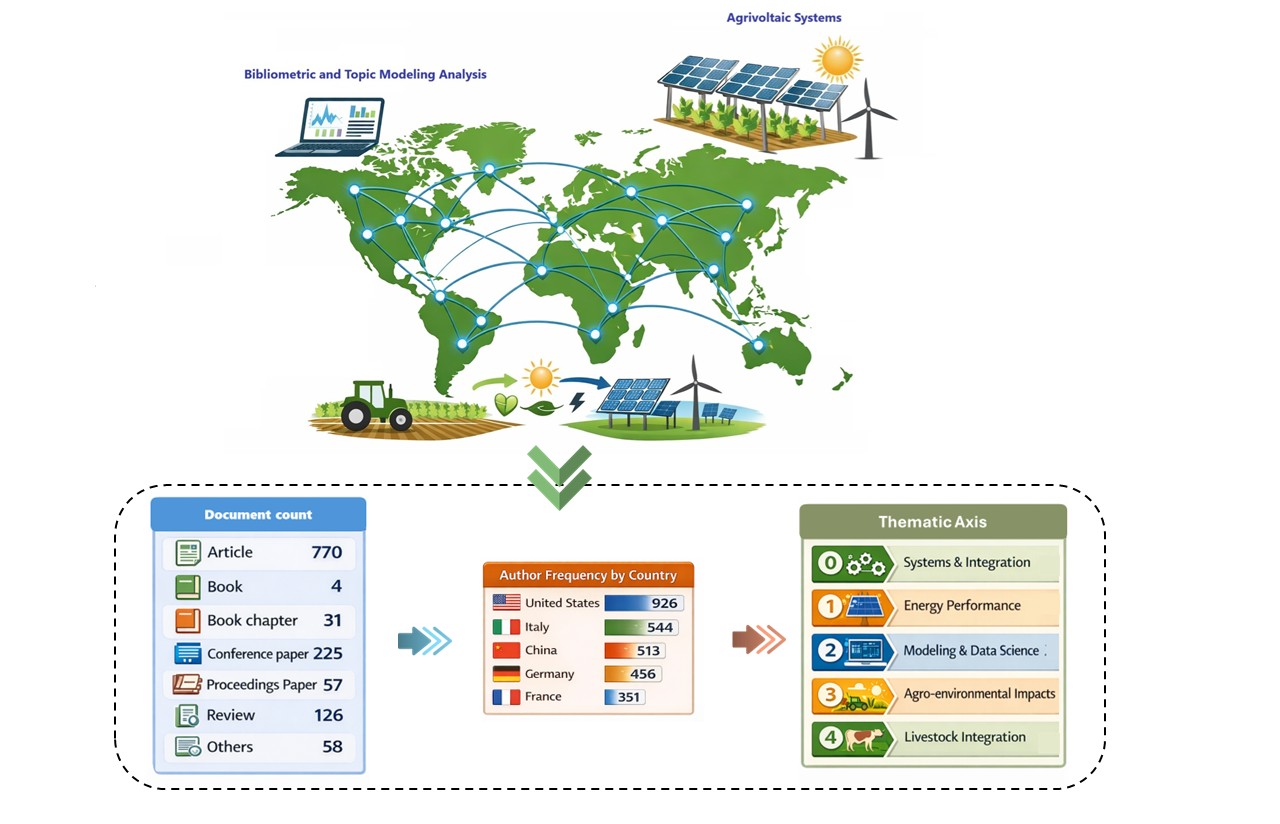

This study was conducted through a bibliometric analysis of scientific literature, following a structured protocol for data search, extraction, and analysis. The research was carried out using the Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and PubMed databases, with data collection performed in December 2025 and no time restrictions, to map the entire body of scientific production on agrivoltaic systems.

The keywords “agrivoltaic”, “agrophotovoltaic”, “agrovoltaic”, and “agri-photovoltaic” were used. Non-related terms, particularly those associated with health and medicine (medicine OR medical OR clinical OR patient OR therapy OR disease OR health), were excluded. The search strategy employed Boolean operators OR for synonyms and NOT for exclusion. After duplicate removal, a total of 1,271 documents remained, as detailed in

Table 1. The analysis was conducted with the support of the PyBibX library, a Python-based tool for bibliometric and scientometric analysis [

8], which enabled the assessment of temporal evolution, geographical distribution, and emerging research topics.

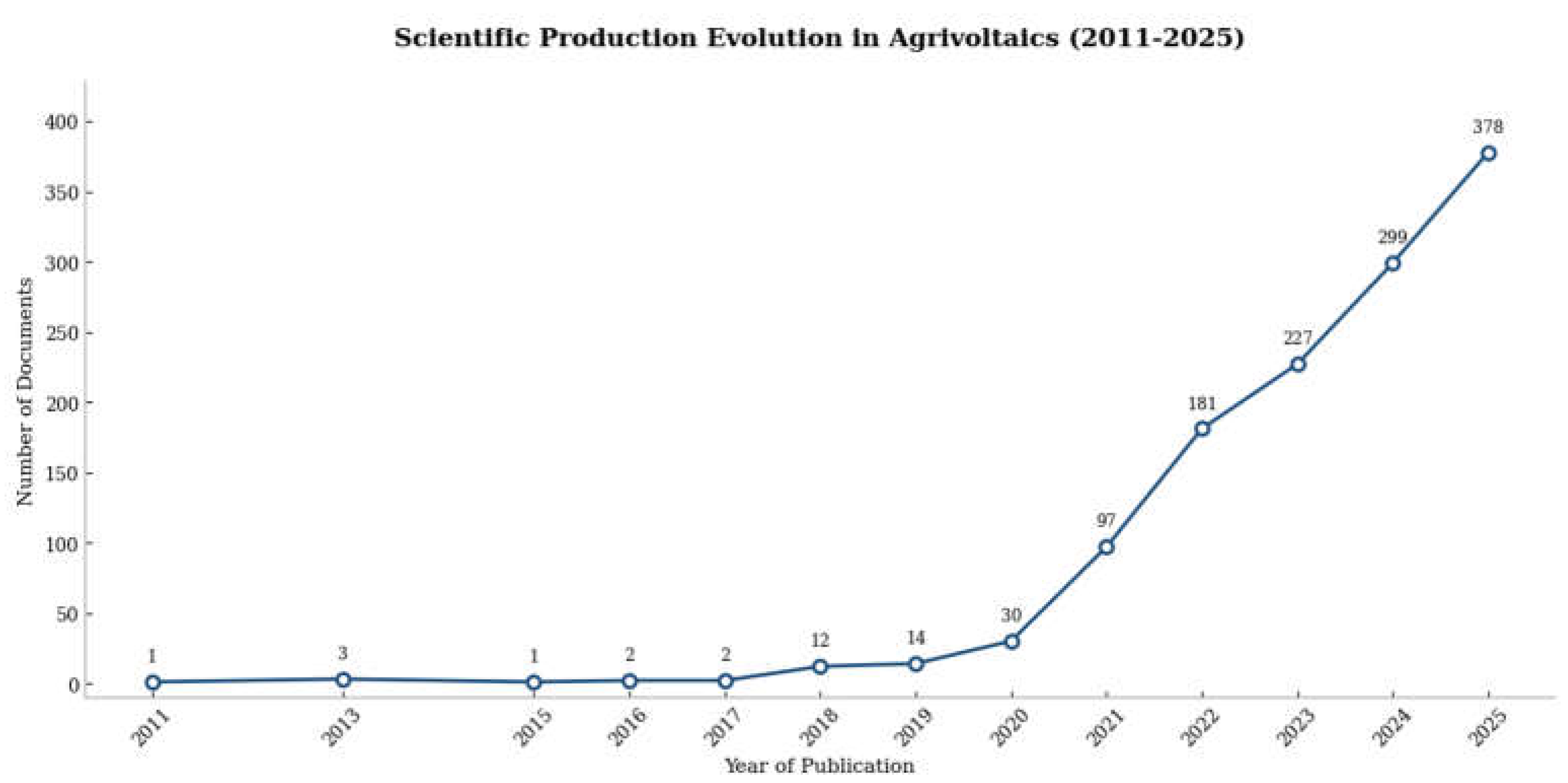

The data indicate that agrivoltaics constitutes a relatively recent and rapidly expanding field of research. Although the concept is grounded in earlier foundations, the volume of publications remained relatively low until 2019. From 2020 onward, a significant and sustained increase in scientific output can be observed, reflecting the growing interest of the academic community in solutions that sustainably integrate solar energy generation with agricultural production. This upward trend continues through 2025, which records the highest number of publications on the topic to date (

Figure 1).

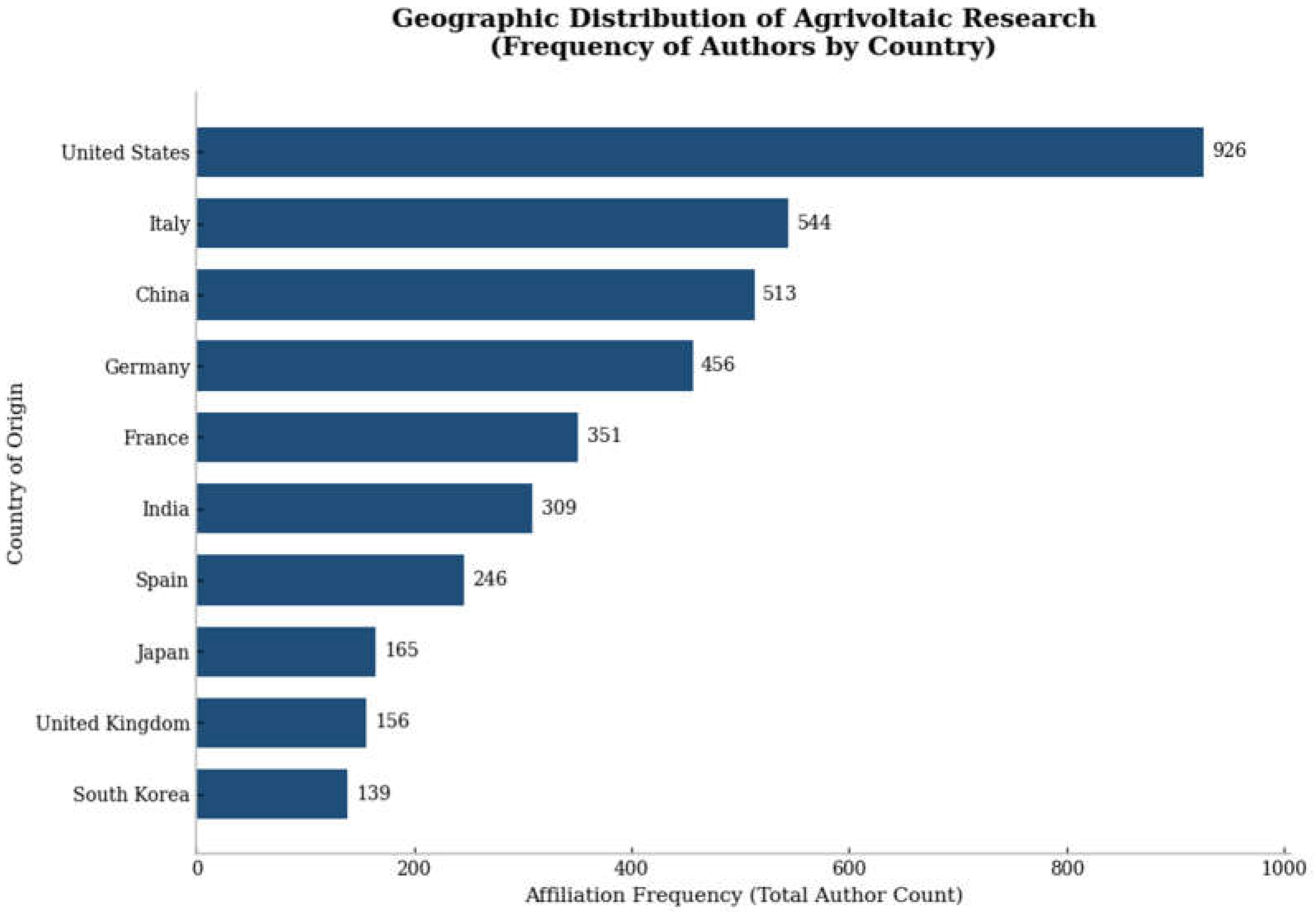

About the geography of scientific production,

Figure 2, highlights the countries leading the development of this technology. A strong concentration of research activity is observed in countries of the Global North (the United States and Europe) and within the Asian technological axis (China, India, Japan, and South Korea). This centralization suggests that the early development of agrivoltaics is closely associated with nations possessing high investment capacity in research, development, and innovation (RDI), as well as strong pressures related to the energy transition. Conversely, it also reveals a publication gap in countries of the Global South, where solar radiation potential and agricultural bases are extensive, yet scientific production remains incipient.

Finally, the semantic analysis conducted through topic modeling enabled the organization of the literature into five central thematic axes, as presented in

Table 2. It is worth noting that Topic −1, typically associated with documents exhibiting low semantic adherence to the remaining groups (i.e., noise or outliers), was excluded from the interpretative analysis, as it does not represent a cohesive thematic axis. Accordingly, the final classification focused on topics that demonstrated conceptual consistency and analytical relevance for understanding the evolution of research on agrivoltaic systems.

The distribution of these topics reveals an evolution of the field, which moves beyond an exclusive focus on technical approaches associated with photovoltaic system engineering to incorporate an increasingly multidisciplinary perspective. The consolidation of thematic axes related to computational modeling, as well as to the impacts of agrivoltaic systems on soil and vegetation, indicates a growing concern with system performance optimization and the biophysical sustainability of agroecosystems. This shift in focus reinforces the understanding that the expansion of energy generation in agricultural areas must occur in a manner that does not compromise agricultural productivity or food security, in line with the principles established by Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG 2).

These thematic axes provide the foundation for the in-depth analysis presented in the following sections, enabling a structured and coherent discussion of the advances, challenges, and future perspectives of agrivoltaic systems.

3. Main Thematic Axes of Literature

Based on the results of the bibliometric analysis and topic modeling, the scientific literature on agrivoltaic systems was organized into four main thematic axes, which structure the subsequent analytical sections of this article. The first axis focuses on studies addressing the conceptual, design, and system integration aspects of agrivoltaics (Topic 0). The second axis encompasses research related to photovoltaic efficiency, solar radiation utilization, and computational modeling of agrivoltaic systems (Topics 1 and 2). The third axis brings together investigations into the effects of agrivoltaic systems on soil, vegetation, and the agricultural microclimate (Topic 3). Finally, the fourth axis includes studies focused on the integration of solar power generation with livestock activities, with an emphasis on pasture-based systems and animal management (Topic 4).

3.1. Agrivoltaic Systems as Integrated Energy Systems

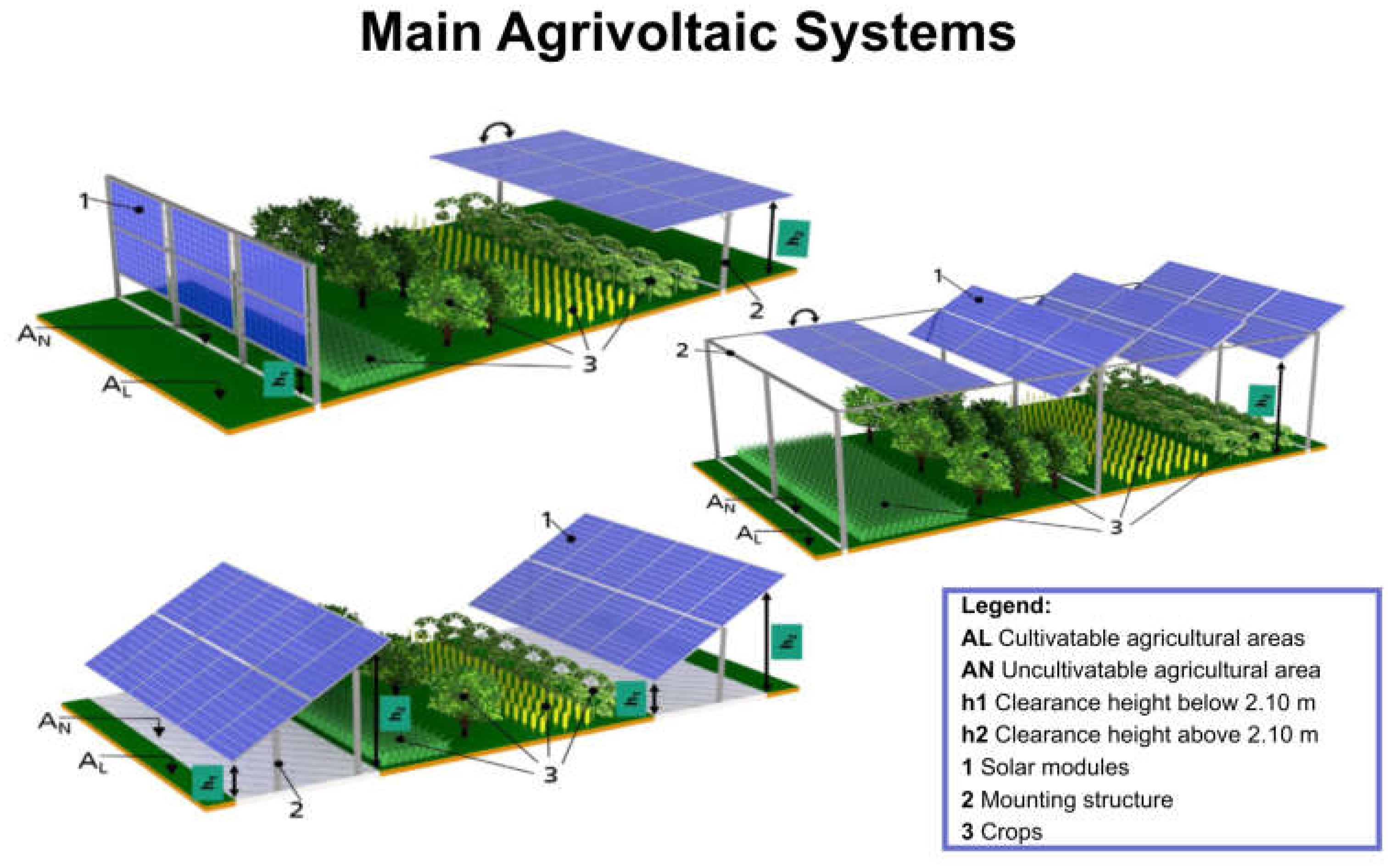

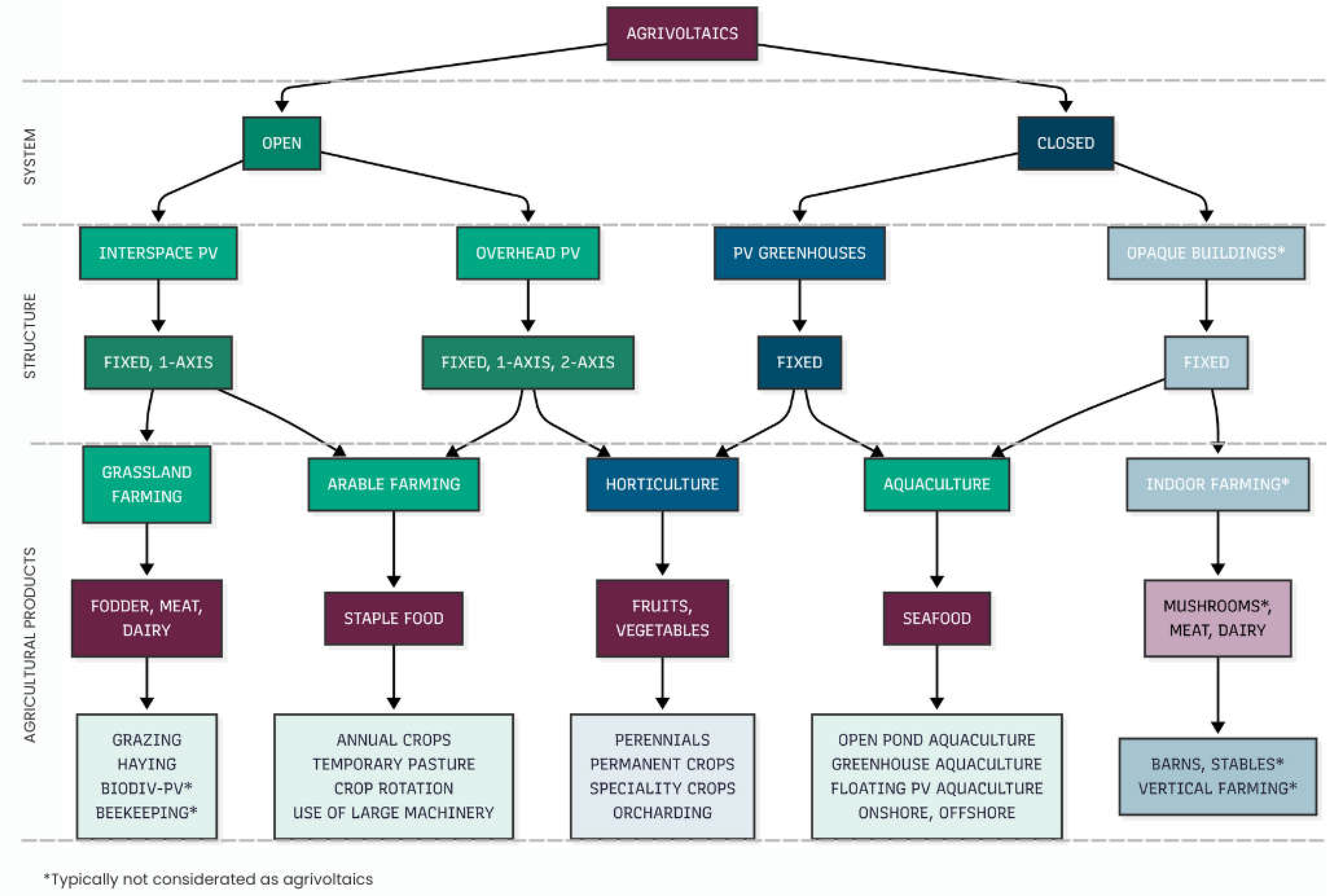

The earliest scientific formulations of agrivoltaic systems were grounded in the principle of dual land use, operationalized through the elevation of photovoltaic modules to simultaneously enable electricity generation and agricultural cultivation on the underlying soil [

9]. From 2015 onward, however, the field began to incorporate new structural configurations, such as inter-row systems and ground-level vertical arrangements, significantly expanding the spectrum of technical solutions and shifting the concept of agrivoltaics from a specific structural model to a broader approach to energy–agriculture integration (

Figure 3) [

10].

This diversification of configurations highlighted the relevance of the spatial organization of agrivoltaic systems as a central element of their integrated operation. Field-based studies demonstrate that parameters such as row spacing, module layout, and the level of induced shading exert a direct influence on agricultural productivity, enabling the identification of optimal degrees of solar coverage compatible with crop performance [

11].

As a result, the literature has proposed multifactorial classification schemes that simultaneously consider system type (open or closed), structural configuration (elevated modules, inter-row arrangements, or greenhouse-integrated systems), module mobility (fixed or tracking), and the type of agricultural or livestock application. The incorporation of these multiple dimensions underscores the consolidation of agrivoltaics as a category of energy systems integrated with productive land use, whose viability depends on balancing energy performance and agricultural functionality [

11] (

Figure 4).

In this context, agrivoltaics moves beyond a mere coexistence technique to become a strategic energy infrastructure, integrated into the electrical system in a decentralized manner. The technological evolution of the sector—already exceeding 14 GWp of global installed capacity by 2021—demonstrates a clear transition from pilot and experimental projects to large-scale commercial applications [

10]. This advancement enables agrivoltaic systems to be conceived not only as generation units, but also as integrated components of local productive systems, capable of meeting specific energy demands such as irrigation, agro-industrial processing, and energy storage solutions, thereby promoting greater resource-use efficiency and reinforcing energy autonomy within the production environment.

3.2. Energy and Technological Performance

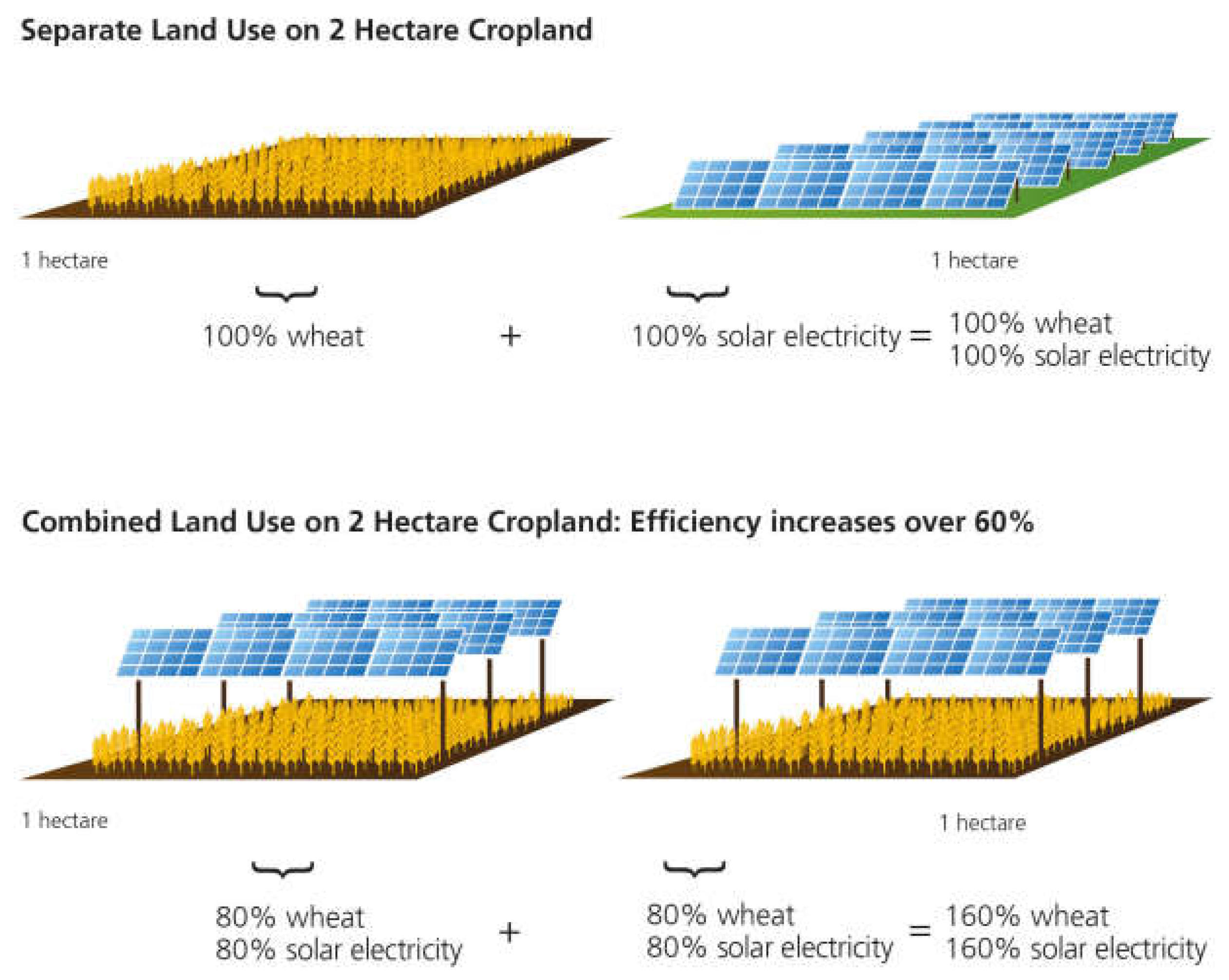

The performance of agrivoltaic systems fundamentally arises from the way solar radiation is partitioned between electricity generation and agricultural production. This partitioning is directly conditioned by the geometric design of the system, which simultaneously controls photovoltaic yield and the shading regime imposed on crops [

12]. This principle is schematically illustrated in

Figure 5, which highlights the difference between separate and combined land use for agricultural and energy production.

In this context, the distinction between direct and diffuse radiation plays a structuring role in agrivoltaic analysis. From a physiological perspective, many crops utilize diffuse light more efficiently due to its more homogeneous penetration into the plant canopy [

13]. This functional difference underpins the development of specific technological solutions, such as concentrating photovoltaic (CPV) systems, which act as solar splitters by concentrating direct radiation onto high-efficiency photovoltaic cells while allowing near-complete transmission of the diffuse fraction to the plants. These systems can achieve transmittance levels above 70%, thereby preserving favorable conditions for photosynthesis [

14].

The centrality of radiation partitioning implies the adoption of evaluation criteria capable of capturing the joint performance of agrivoltaic systems. This stems from the fact that the agrivoltaic logic differs structurally from that of conventional photovoltaic systems: while ground-mounted PV (GM-PV) systems are designed to maximize electricity production per unit area, agrivoltaics seeks to optimize the simultaneous use of land for energy and agricultural production [

15].

In this regard, the most widely used technical indicator is the Land Equivalent Ratio (LER), according to which a system is considered advantageous when the sum of relative agricultural productivity (α) and energy productivity (β) exceeds unity (α + β > 1) [

16]. The LER thus synthesizes the trade-off between electricity generation and agricultural production that characterizes agrivoltaic systems.

Operationalizing this trade-off involves complex physical and biological interactions, which has driven the adoption of advanced computational models as tools to support system planning and operation. Methods such as ray tracing and view-factor calculations enable high-precision simulations of the spatial distribution of incident radiation over crops, allowing for the simultaneous estimation of electrical and agricultural yields [

17].

Three-dimensional tools have been widely employed to test different structural arrangements, module configurations, and spacing prior to field deployment, thereby reducing technical and productive uncertainties [

18]. At a more advanced stage, approaches based on machine learning and hybrid models have been increasingly explored—particularly by research groups in Germany and China—as a means of addressing the nonlinear and transdisciplinary nature of agrivoltaic systems [

19,

20].

In parallel, integrated energy balance models have been used to assess specific applications, such as the feasibility of organic photovoltaic (OPV) modules in agricultural greenhouses. These studies demonstrate that it is possible to meet internal energy demands while maintaining reductions in photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) at acceptable levels [

21]. An example of such applications is shown in

Figure 6, which illustrates an experimental greenhouse covered with OPV modules [

22].

From an analytical standpoint, the consolidation of these methods and metrics highlights a recurring dilemma in the literature: the configuration that maximizes electrical yield rarely coincides with that which optimizes agricultural performance [

12]. In systems oriented toward high-value horticulture, the economic viability of sacrificing part of the electrical output—such as through trackers that deliberately deviate from the optimal energy-generation position—has been observed in favor of improved microclimatic conditions and crop health [

24].

Thus, the search for an “optimal point” in agrivoltaic systems constitutes not only a technical problem, but also a multicriteria optimization challenge, conditioned by crop type, local climatic conditions, and the economic viability of the target market.

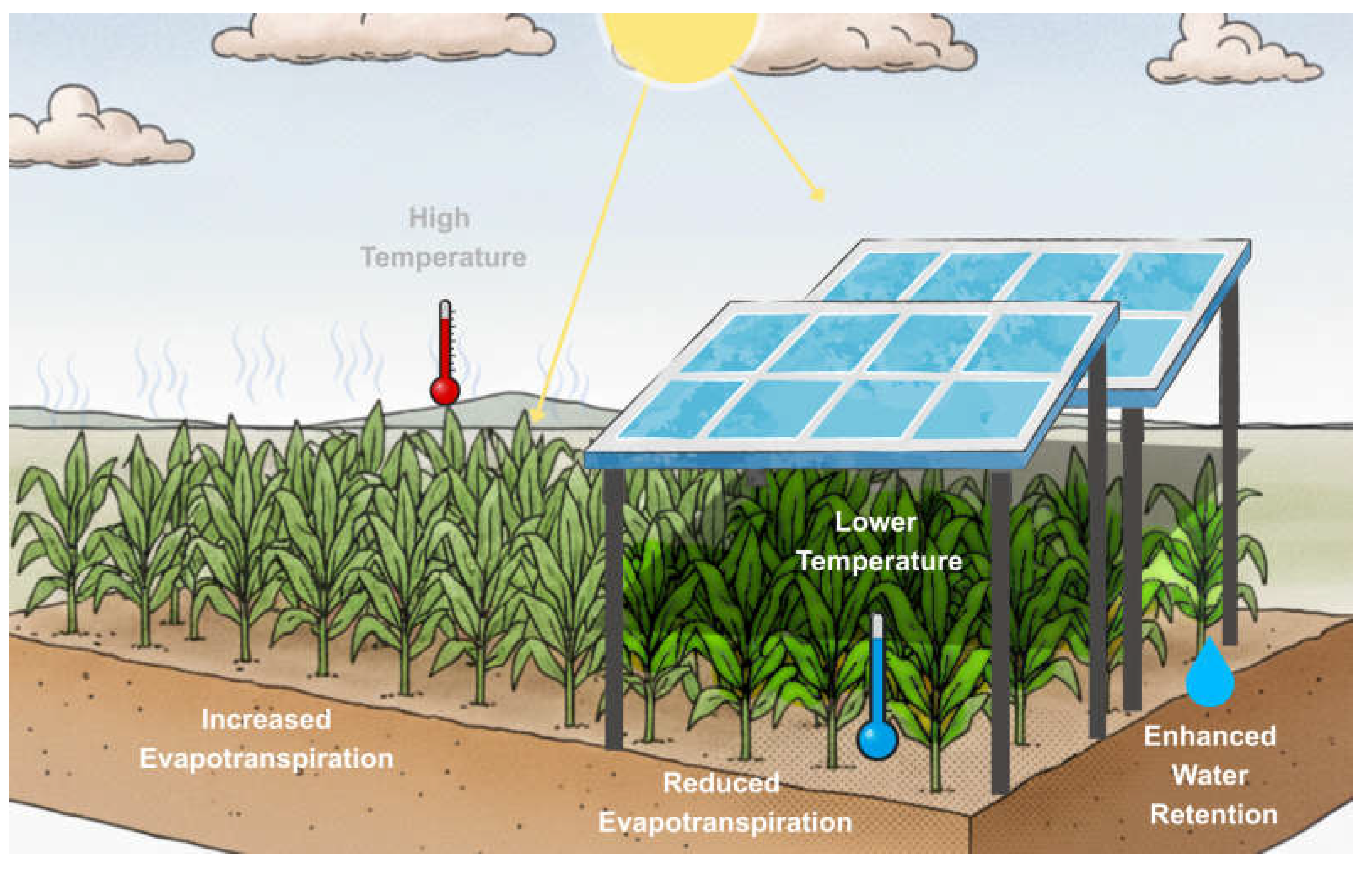

3.3. Agro-Environmental Impacts

From a microclimatic perspective, the presence of photovoltaic panels systematically alters meteorological variables at the crop level. Partial shading reduces daytime air temperatures by approximately 1.2 °C, while nighttime temperatures tend to be slightly higher on the order of 0.5 °C, resulting in a more thermally stable environment over the diurnal cycle (

Figure 7) [

3]. In addition, soil temperature exhibits significant reductions during summer periods, which contributes to decreased root thermal stress and to the maintenance of crop physiological activity under extreme heat conditions [

24].

These thermal changes are associated with relevant modifications in the system’s water regime. Relative air humidity tends to be higher beneath the panels, which is reflected in lower vapor pressure deficit (VPD) values, indicating a less water-demanding atmosphere and favoring leaf hydration [

25,

26]. Together, partial solar radiation blockage and the reduction in wind speed induced by photovoltaic structures result in a decrease in average daily evapotranspiration ranging from 14% to 29%, representing a particularly relevant water-saving effect in arid and semi-arid regions [

12,

27].

From a soil perspective, the literature indicates that agrivoltaic systems can contribute to soil moisture conservation, with levels remaining, on average, about 15% higher than those observed in open-field agricultural areas [

26]. This effect improves water-use efficiency and may reduce the need for supplemental irrigation. However, soil impacts are not exclusively positive and depend strongly on installation and management practices. The use of heavy machinery during installation may cause soil compaction, with negative effects on soil structure and fertility; therefore, construction activities are recommended during periods of low soil moisture [

10]. Conversely, photovoltaic structures may function as windbreaks, reducing wind erosion, while non-cultivated strips near panel foundations can act as biotopes, contributing to biodiversity maintenance and protecting soil against erosive processes [

28].

Crop responses to the agrivoltaic environment vary significantly depending on shade tolerance and physiological requirements. Species such as leafy vegetables, berries, aromatic herbs, and forage crops exhibit high adaptability and are often classified as shade tolerant [

8]. Some crops, such as potatoes, belong to the so-called “plus class,” in which partial shading may result in productivity gains due to improved microclimatic conditions [

29]. Under intense heat scenarios, crops such as peppers and cherry tomatoes have shown substantial yield increases under shading levels between 70% and 80%, whereas species highly dependent on direct radiation may experience yield reductions if shading exceeds their light saturation point [

3].

Beyond productive effects, agrivoltaic systems contribute to increased agricultural resilience to extreme climatic events. The panels provide physical protection against hail, frost, and sunburn damage to fruits, functioning as risk-mitigation infrastructure and contributing to production stabilization under conditions of increasing climate variability [

12].

Convergently, the literature emphasizes that the agro-environmental benefits of agrivoltaics are conditional and strongly dependent on the alignment between crop type, local climate, and management strategies. In hot and dry regions, shading tends to reduce water and thermal stress, whereas in environments where light is already the main limiting factor, radiation reduction may compromise productivity. Thus, the success of agrivoltaic systems requires designs guided by crop physiological needs, with dynamic light adjustments, flexible spatial configurations, and layouts compatible with agricultural mechanization.

3.4. Livestock Applications

The integration of photovoltaic systems with pasturelands, often referred to as grassland farming, is based on the simultaneous use of land for forage production, animal grazing, and electricity generation. This approach maximizes land-use efficiency by allowing areas traditionally dedicated exclusively to livestock production to also contribute to the energy matrix, without necessarily compromising forage productivity [

30]. In addition, the presence of photovoltaic structures may provide supplementary environmental functions, contributing to the long-term maintenance of pasture productivity [

28].

From an animal welfare perspective, agrivoltaic systems offer direct benefits related to thermal comfort. The natural shading provided by the panels reduces heat stress, particularly in warm climates, where prolonged solar exposure can impair animal health and zootechnical performance (

Figure 8) [

31]. Field observations indicate that sheep show a clear preference for areas shaded by photovoltaic modules compared to open pasture areas, suggesting positive behavioral adaptation to the agrivoltaic environment. There is also evidence that these microclimatic conditions may lead to improvements in the quality of by-products, such as wool, although this aspect still requires systematic investigation [

31].

Among the various livestock applications, the use of sheep represents the most mature and widely documented case, particularly in North America and Europe. This predominance stems from the high operational compatibility between animal size and photovoltaic infrastructure, as well as the functional role sheep play in system maintenance. Sheep act as “natural mowers,” reducing the need for mechanical vegetation cutting and herbicide use, which results in lower operational expenditures (OPEX) and a reduced risk of damage to cables and modules [

33]. Recent technical standards, such as DIN SPEC 91434, formally recognize the integration of other species—including cattle, goats, poultry, and pigs—under or between photovoltaic modules, thereby expanding the potential scope of agrivoltaic livestock applications [

10,

34].

The viability of these systems, however, depends on appropriate design and logistical decisions. Innovations such as vertical photovoltaic systems with bifacial modules have gained prominence by allowing free movement of agricultural machinery and animals between rows, with typical spacing ranging from 6 to 15 m [

35]. In elevated systems, the literature recommends minimum heights exceeding 2.1 m to ensure safe circulation of machinery and livestock [

34]. Experiences conducted in Germany, such as those developed by the company Next2Sun, demonstrate the economic feasibility of forage production between rows of vertical modules, consolidating this model as a promising alternative for sustainable land use (

Figure 9) [

36].

Empirical results from case studies indicate that although forage density under photovoltaic panels may be lower than that observed in open pastures—by up to 38% in some cases—the nutritional quality tends to be higher, resulting in comparable zootechnical performance, such as lamb production [

33]. From an environmental perspective, estimates suggest that each animal integrated into agrivoltaic systems may contribute to emission reductions on the order of 103 kg CO₂ equivalent per year, reinforcing the potential of these arrangements as climate mitigation strategies [

37].

Despite the observed advances, the literature converges on the identification of relevant research gaps within the livestock axis. While the integration of sheep under photovoltaic panels represents a well-established success case, large-scale applications involving beef and dairy cattle remain underexplored [

37]. This gap is particularly evident in tropical and arid contexts, where the shading provided by agrivoltaics may play a decisive role in reducing heat stress, promoting the regeneration of degraded pastures, and supporting the adaptation of livestock systems to climate change.

4. Future Perspectives

Future perspectives point toward overcoming static photovoltaic systems in favor of dynamic, adaptive arrangements oriented toward crop biological logic. Advances in intelligent tracking systems will enable modules to adjust their tilt not only to maximize electricity generation but also to modulate radiation input according to plant phenological stages or thermal stress conditions [

38,

39,

40]. These solutions, however, imply increased capital costs, especially in elevated or mobile systems, reinforcing the need for integrated economic assessments that simultaneously consider agricultural yields, energy production, and climate risk reduction. In parallel, the development of spectrally selective modules—including emerging technologies such as organic photovoltaics (OPV) and luminescent solar concentrators (LSC)—is expected to redefine the relationship between light and agricultural production by directing specific portions of the solar spectrum to electricity generation while preserving photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) essential for plant growth [

21].

Technological evolution also involves the consolidation of integrated energy infrastructure combining generation, storage, and decentralized energy management. The incorporation of batteries and rural microgrids enhances farm-level energy autonomy and enables active participation in local energy markets or grid stability services. This infrastructure can be synergistically coupled with smart irrigation systems, in which photovoltaic modules themselves act as elements for rainwater capture and redirection, increasing water-use efficiency and reinforcing the multifunctional character of the technology [

10].

From a scientific standpoint, advancing the field requires a transition from isolated case studies to integrated modeling approaches of the energy–water–plant nexus [

20]. The use of artificial intelligence and machine learning becomes central to addressing long time series and increasing climatic variability, enabling more robust predictions of agricultural productivity and energy performance. To support this evolution, international standardization of metrics is essential, along with the strengthening of technical standards that ensure the primacy of the agricultural function in agrivoltaic systems. The absence of consolidated regulatory frameworks in many countries currently constitutes a barrier to financing and commercial expansion, as it generates technical and legal uncertainties for investors and financial institutions [

10].

In this context, there is a clear need to broaden and diversify the agrivoltaics research agenda, particularly in regions of the Global South, where distinct solar regimes prevail and productive systems remain underrepresented in the literature. Future studies should prioritize the development and validation of shading and radiative distribution models better suited to conditions of high solar incidence and elevated zenith angles, as well as their integration with diverse edaphoclimatic and agricultural contexts.

Finally, future applications should prioritize extensive livestock systems integrated with bifacial or vertical modules, strategies for regenerating degraded areas, and business models oriented toward family farming and cooperatives. In these contexts, agrivoltaics can simultaneously function as an instrument for climate adaptation, environmental restoration, and rural socioeconomic strengthening, consolidating itself as a key technology for resilient agro-energy systems [

10].

5. Conclusions

The performance of agrivoltaic systems depends on multicriteria approaches capable of simultaneously considering energy, agronomic, environmental, and economic variables, moving beyond assessments based exclusively on maximizing photovoltaic generation. The thematic organization presented herein demonstrates relevant technological advances, measurable agro-environmental impacts, and viable productive applications, while also revealing significant research gaps—particularly in regions of the Global South, in large-scale livestock systems, and in long-term analyses. In this context, strengthening agrivoltaics as a sustainable solution requires metric standardization, the development of integrated models, and the expansion of empirical studies that account for territorial specificities, rural development objectives, and climate change adaptation.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APV |

Agrivoltaic |

| CO₂ |

Carbon dioxide |

| CPV |

Concentrating photovoltaic |

| GM-PV |

Ground-mounted PV |

| GWp |

Gigawatt-peak |

| LER |

Land Equivalent Ratio |

| LSC |

Luminescent solar concentrators |

| OPEX |

Operational expenditures |

| OPV |

Organic photovoltaic |

| PAR |

Photosynthetically active radiation |

| PV |

Photovoltaic |

| RDI |

Research, development, and innovation |

| SDG 2 |

Sustainable Development Goal 2 |

| VPD |

Vapor pressure deficit |

| WoS |

Web of Science |

References

- United Nations. Goal 2: Zero Hunger—Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/hunger/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture 2025—Systems at Breaking Point (SOLAW 2025); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/publications/fao-flagship-publications/the-state-of-the-worlds-land-and-water-resources-for-food-and-agriculture/en (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A.; Minor, R.L.; Sutter, L.F.; Barnett-Moreno, I.; Blackett, D.T.; Thompson, M.; Dimond, K.; Gerlak, A.K.; Nabhan, G.P.; et al. Agrivoltaics provide mutual benefits across the food–energy–water nexus in drylands. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, M. Performance Indices for Parallel Agriculture and PV Usage: Approaches to Quantify Land Use Efficiency in Agrivoltaic Systems; IEA-PVPS Task 13; International Energy Agency Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme: . 2020. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/IEA-PVPS_Task-13_R15-Performance-of-New-PV-system-designs-report.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Dupraz, C. Assessment of the ground coverage ratio of agrivoltaic systems as a proxy for potential crop productivity. Agrofor. Syst. 2024, 98, 2679–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturchio, M.A.; Macknick, J.; Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Higgins, C.W.; Smith, M.S. Agrivoltaic arrays can maintain semi-arid grassland productivity and extend the seasonality of forage quality. Appl. Energy 2024, 356, 122418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.; Basilio, M.P.; Santos, C.H.T. PyBibX: A Python library for bibliometric and scientometric analysis powered with artificial intelligence tools. Data Technol. Appl. 2025, 59, 302–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzberger, A.; Zastrow, A. Kartoffeln unter dem Kollektor (Potatoes under the collector). Sonnenenergie 1981, 3, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Trommsdorff, M.; Heller, A.; Schindele, S. Agrivoltaics: Solar power generation and food production. In Solar Energy Advancements in Agriculture and Food Production Systems; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 159–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, S.; Bousi, E.; Özdemir, Ö.S.; Trommsdorff, M.; Kumar, N.M.; Jelle, B.P.; Zhou, Y. Progress and challenges of crop production and electricity generation in agrivoltaic systems using semi-transparent photovoltaic technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraunhofer, ISE. Harvesting the Sun for Power and Produce—Agrophotovoltaics Increases the Land Use Efficiency by over 60 Percent; Press Release 20/17; Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE: Freiburg, Germany, 2017. Available online: https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/press-media/press-releases/2017/harvesting-the-sun-for-power-and-produce-agrophotovoltaics-increases-the-land-use-efficiency-by-over-60-percent.html (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Li, T.; Yang, Q. Advantages of diffuse light for horticultural production and perspectives for further research. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Lv, H.; Liao, J.; Shang, Y.; Liu, W.; Lv, Q.; Cheng, C.; Su, Y.; Riffat, S. A dish-type high-concentration photovoltaic system with spectral beam-splitting for crop growth. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2017, 9, 063701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, M. Working Paper No. 03-2016; An Economic Analysis of Agrophotovoltaics: Opportunities, Risks and Strategies Towards a More Efficient Land Use. Constitutional Economics Network: Freiburg, Germany, 2016.

- Dupraz, C.; Marrou, H.; Talbot, G.; Dufour, L.; Nogier, A.; Ferard, P.H. Combining solar photovoltaic panels and food crops for optimising land use: Towards new agrivoltaic schemes. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 2725–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Lim, J.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, J.H. Practical comparison between view factor method and ray tracing method for bifacial PV system yield prediction. In Proceedings of the 36th European PV Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition (EU PVSEC), Marseille, France, 9–13 September 2019; pp. 950–954. [Google Scholar]

- Willockx, B.; Herteleer, B.; Cappelle, J. Techno-economic study of agrovoltaic systems focusing on orchard crops. In Proceedings of the 37th European PV Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition (EU PVSEC), Online, 7–11 September 2020>; pp. 1490–1495. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y. A criterion of crop selection based on the novel concept of an agrivoltaic unit and M-matrix for agrivoltaic systems. In Proceedings of the 7th World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conversion (WCPEC-7), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 10–15 June 2018; pp. 1324–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Fraunhofer, ISE. Agri-Photovoltaics. Available online: https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/key-topics/integrated-photovoltaics/agrivoltaics.html (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Emmott, C.J.M.; Röhr, J.A.; Campoy-Quiles, M.; Kirchartz, T.; Urbina, A.; Ekins-Daukes, N.J.; Nelson, J. Organic photovoltaic greenhouses: A unique application for semi-transparent PV? Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.; Kacira, M.; Magadley, E.; Teitel, M.; Yehia, I. Evaluating the performance of flexible, semi-transparent large-area organic photovoltaic arrays deployed on a greenhouse. AgriEngineering 2022, 4, 969–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, A.; Colauzzi, M.; Amaducci, S. Innovative agrivoltaic systems to produce sustainable energy: An economic and environmental assessment. Appl. Energy 2021, 281, 116102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weselek, A.; Ehmann, A.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Schindele, S.; Högy, P. Agrophotovoltaic systems: Applications, challenges, and opportunities. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, P.; Muñoz, I.; Acuña, I. AgroPV: Mancomunión Energía Solar y Agricultura; Project Report; Fraunhofer Chile Research: Santiago, Chile, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Minor, R.L.; Allen, N.A.; Cronin, A.D.; Brooks, E.P.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A. The photovoltaic heat island effect: Larger solar power plants increase local temperatures. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elamri, Y.; Cheviron, B.; Lopez, J.M.; Dejean, C.; Belaud, G. Water budget and crop modelling for agrivoltaic systems: Application to irrigated lettuces. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 208, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Hou, A.; Chang, C.; Huang, X.; Shi, D.; Wang, Z. Environmental impacts of large-scale CSP plants in northwestern China. Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts 2014, 16, 2432–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Bopp, G.; Goetzberger, A.; Obergfell, T.; Reise, C.; Schindele, S. Combining PV and food crops to agrophotovoltaic—Optimization of orientation and harvest. In Proceedings of the 27th European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition (EU PVSEC), Frankfurt, Germany, 24–28 September 2012; pp. 4148–4152. [Google Scholar]

- Krause-Tünker, S. Next2Sun: Experiences with Vertical Agro-Photovoltaic. Presentation at Agrivoltaics Conference, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, A.S.C.; da Silva, R.G.; Loureiro, B.A.B.; Silva, N.C. Photovoltaic panels as shading resources for livestock. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasch, A.; Lara, R.; Pearce, J.M. Financial analysis of agrivoltaic sheep: Breeding and auction lamb business models. Appl. Energy 2025, 381, 125057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, A.C.; Higgins, C.W.; Smallman, M.A.; Graham, M.; Ates, S. Herbage yield, lamb growth and foraging behavior in agrivoltaic production system. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 659175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

DIN SPEC 91434:2021-05; Agri-Photovoltaic Systems—Requirements for Primary Agricultural Use. Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2021.

- Khan, M.R.; Hanna, A.; Alam, M.A. Vertical bifacial solar farms: Physics, design, and global optimization. Appl. Energy 2017, 206, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Next2Sun. Reference Projects. Available online: https://www.next2sun.de/en/references/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Handler, R.; Pearce, J.M. Greener sheep: Life cycle analysis of integrated sheep agrivoltaic systems. Cleaner Energy Syst. 2022, 3, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, B.; Simonneau, T.; Sourd, F.; Pechier, P.; Hamard, P.; Frisson, T.; Rybiansky, M.; Prieto, J.A. Increasing the total productivity of a land by combining mobile photovoltaic panels and food crops. Appl. Energy 2017, 206, 1495–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffon-Terrade, B. Effect of Transient Shading on Phenology and Berry Growth in Grapevine. Master’s Thesis, L’Institut Agro, Montpellier, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Juillion, P.; Lopez, G.; Fumey, D.; Génard, M.; Lesniak, V.; Vercambre, G. Water status, irrigation requirements and fruit growth of apple trees grown under photovoltaic panels. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Agrivoltaics, Online, 2020; p. 050002. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |