1. Introduction

The growing global demand for natural resources, driven by the consumption pattern of developed and emerging industrialized economies, threatens the planet. The standard of living in economies will continue to rise and, by 2060, GDP per capita in emerging countries is expected to reach OECD levels [

1]. Different studies have projected that total resource use could more than double by 2050 if these trends continue [

2,

3]. Therefore, it is urgent to improve the efficiency with which resources are used by maximizing their value and avoiding that the increase in globalized demand for resources leads to a shortage of supply leading to an increase in input costs, the extraction of raw materials from nature at a much faster rate than the capacity of nature to recycle and return them to nature, based on a linear model with abundant reserves of cheap and readily available materials and energy sources as referred to by DGCEP [

4].

The concept of circular economy (CE) first emerged in the literature through three main pillars, known as the 3R principles: reduce, reuse and recycle [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. In this context, the CE model is presented as a key component to steer the world towards sustainability and help achieve the proposed goals. Subsequently, at the United Nations Environment Assembly, new variables were introduced to the CE model, describing it as: “one of today’s sustainable economic models in which products and materials are designed to be reduced, reused, recycled or repaired (4R’s). This approach ensures that they remain in the economy for as long as possible, together with the resources from which they are made, while avoiding or minimizing the generation of waste, especially hazardous waste, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions”. It should be noted that several systematic analyses have been carried out in order to find that most appropriate definition, although it is an extremely complicated task, due to the fact that numerous meanings of this term have been found, amounting to 114 definitions as highlighted by [

11].

In recent years, the global need for a “circular” economy, as opposed to the predominantly “linear” economy currently in place, has been recognized. The linear economy generates outcomes that are harmful to the environment and relies on non-renewable inputs, as well as its global supply chains of finite natural reserves [

12]. According to the United Nations, the agricultural sector occupies 50% of the Earth’s habitable surface, contributes 25–30% of greenhouse gas emissions, and is responsible for 80% of deforestation, 90% of land degradation, and 80% of biodiversity loss. Furthermore, it consumes 70% of freshwater and is responsible for over 80% of water pollution. In addition, 89% of fisheries are overexploited or at capacity [

13].

Agriculture is critical to support our basic needs (to feed the world) but is a greater user of natural resources and causes a great impact on the environment (pollution and degradation of natural resources: soil, water and biodiversity). For example, agriculture uses more inputs of natural resources per unit of value added than any other sector of the economy, including manufacturing, construction, and transportation [

14]. It is the greater user of water resources, using approximately 70%of freshwater withdrawals as refers Gleick [

15]. More than 60% of European Union soils are undergoing degradation processes, with impacts on food security, ecosystem services and human health [

16]. In this context, it is critical the change to a circular paradigm in agriculture production.

According to Jaskani and Khan [

17], Horticulture is the science and art of growing high-value plants, such as fruits, vegetables, ornamental plants, herbs and medicinal plants and plays a key role in the global food value chain. Horticulture, in general, integrate intensive systems of agriculture, and due that has shown the most relevant progress in adopting circular principles. Protected horticulture such as greenhouse, can ensure high quality production and contribute to global food security. Protected horticulture, such as greenhouse cultivation, offers significant opportunities for circular production, optimizing the use of resources by recycling at various levels, from individual farms to the regional level. The use of greenhouses promotes circularity through: high productivity with reduced use of water and agrochemicals per unit of production, production capacity per hectare of up to 10 to 15 times higher compared to open field agriculture and also as a potential tool for water and nutrient recycling [

18]. The concept of CE is of great interest for both academics and farmers as it is considered as a criterion when operating for firms to work from sustainable development. However, it remains a concept that sparks controversy [

19,

20]. CE has gained popularity over time and there are numerous actors, particularly among the stakeholders who adopt it, so its interpretation and implementation can be diffuse and fragment its conceptualization [

11].

It is worth noting that the concept of CE becomes more diffuse in the field of agriculture. Several works, the specific characteristics of the agricultural sector and the need to adopt CE methodologies in this area are discussed. Additionally, emphasis is placed on the need more appropriate indicators to address the complexities of this sector is also emphasized by Velasco-Muñoz et al. [

21]. The use of bibliometric analysis has become an essential tool for evaluating scientific production in various areas of knowledge. This approach makes it possible to identify patterns, trends and relationships between publications, authors, institutions and research topics. By applying bibliometric methods, it is possible to measure the impact of specific studies, map scientific collaboration networks and explore the evolution of concepts over time [

22,

23,

24,

25]. A number of bibliometric studies on the CE have been published recently, offering researchers a novel perspective on the subject. These studies have begun to explore the field from a business administration perspective, in addition to the traditional environmental sciences. Camón and Celma [

26] identify key authors, publications, and themes in this area, noting a shift from production aspects to the growing importance of business organization and its impact on structures.

Dominko et al.; [

27] conducted a comprehensive study on the CE using bibliometric analysis, with the objective of exploring trends in CE. The study emphasized the focus on theoretical frameworks and technological solutions, while observing a slow transition to practical implementation. The study identified a gap between theoretical opportunities and real-world adoption by companies, advocating for a relational, action-based approach to accelerate progress, and offers valuable insights into key publications, authors, and trends. Further research is required to determine the extent to which academics are appropriately using the concept of the CE, whether for the purpose of attracting more readers of their publications or more success in fundraising. In addition, it is necessary to determine the thematic and contextual areas in which the term ‘circular economy’ is being used. A further key question is whether academics are using the concept of the CE for the sake of innovation, to increase the readership of their publications, or to enhance success in fundraising. In which thematic and contextual areas is the term ‘circular economy’ being used?

The aim of this article is to assess the extent to which CE principles are genuinely integrated into research in line with its fundamental concepts, or whether the term is being misapplied to justify conventional approaches in areas such as the use of phytopharmaceuticals and environmental agricultural technologies. While research into environmental and agricultural sustainability undoubtedly supports broader sustainability goals, this study highlights the importance of using the term “circular economy” authentically, rather than as a superficial label or marketing tool. To achieve the proposed objective, a bibliometric analysis was carried out, focusing on the relationship between the keywords of articles related to horticulture and the circular economy, their abstracts and the specific terminology associated with the CE. This analysis aims to uncover patterns, identify gaps and ensure that the research attributed to the CE adheres to its fundamental principles of resource efficiency, waste minimization and the creation of closed-loop systems, reducing the pressure over the natural resources and ecossystems. By critically evaluating the discourse around the CE in horticultural research, this study seeks to promote a more precise and meaningful application of the concept in scientific research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bibliographic Search

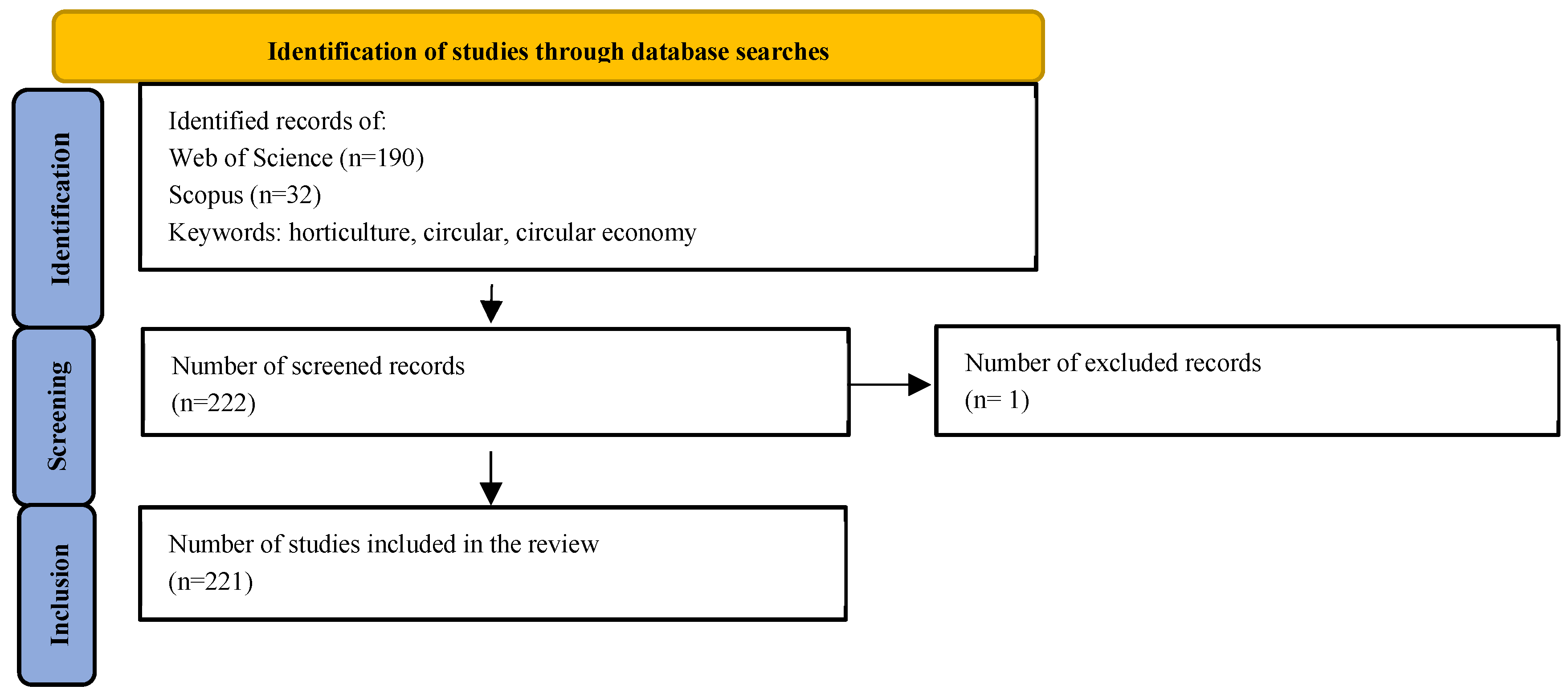

At the outset, a systematic literature review on circular economy and horticulture, the review was conducted using the PRISMA method [

28] (

Figure 1). The review focused exclusively on articles published in English on database. This analysis only found articles from 2016 onward, and there was no data before that data. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in two primary research databases (Scopus and Web of Science) in November 2024 using three keywords (horticulture, circular and circular economy) in the title, abstract and keywords, it has been seen that by removing the keyword “circular”, the same results were obtained. A total of 222 articles were identified in both databases. Subsequently, “open publisher invited review” articles were excluded because they did not fit the research objective, resulting in 221 articles.

After examining the abstracts of these articles, all 221 studies were deemed relevant and included in the review.

2.2. Keyword Map

A keyword map is a visual representation of the frequency of co-occurrence between two terms or keywords within a dataset. This co-occurrence can be observed in the titles or abstracts of articles in a bibliographic database. Co-occurrence analysis is a method of identifying and illustrating relationships between terms, highlighting concepts or topics that frequently appear together in a network of nodes and links [

29]. This method has been applied across various fields, including artificial intelligence, education, and healthcare [

30]. There are different software tools that allow bibliometric analysis, highlighting CitNetExplorer [

31], VOSviewer [

29], SciMAT [

32], Science of Science (Sci2), Tool [

33], CiteSpace [

34] among others. In this case, VOSViewer was used, since it addresses the graphical representation of bibliometric maps and is useful for displaying bibliometric maps of large size and easy interpretation [

35]. Bibliographic searches from two databases were exported and imported into the software. Subsequently, a co-occurrence analysis was conducted, defining that the minimum number of times a keyword should appear was three. Initially, a threshold of five occurrences was tested, but a threshold of three was chosen as it allowed for better noise filtering thus achieving a greater clarity of the map that allowed a better interpretation of results.

This clarity was achieved by improving the visualization of connectivity; low-frequency keywords often fail to show meaningful links with other terms, potentially leading to an incomplete understanding of the context. Therefore, this threshold enabled greater customization of the analysis. In short, this number allowed a greater personalization of the analysis. Additionally, those words that did not align with the research objective were eliminated, i.e.; those terms that were neither related to horticulture nor to CE, such as “review” “nonhuman”, resulting in the removal of five keywords.

2.3. Abstracts Map

As mentioned in the objective of this work, the aim is to find out whether the keywords are really associated with the information contained in the abstracts, since the abstract offers a concise view of the results and can indicate whether it contains CE or related words and whether there is a relationship with these words [

36].

The abstract text-based map was utilised to explore and visualise the relationships, themes and patterns within the abstracts of the academic articles or other papers. A map of the abstracts was conducted using the VOSViewer software, with the bibliographic searches obtained in both databases. A minimum threshold was established, stipulating that a keyword must appear a minimum of three times. Terminology unrelated to the study’s objectives, i.e. terms not associated with horticulture or the CE, such as “Norway” or “case”, was excluded, resulting in the removal of a total of 35 words.

2.4. Quantitative Analysis of Abstracts and Keywords

To identify the main research trends in the literature on CE and horticulture, an approach based on the frequency of codes was used. The abstracts and keywords were analyzed using the software MAXQDA 24. The process began with thoroughly reading the abstracts from the selected publications. Subsequently, textual analysis techniques were applied to identify the occurrence of terms relevant to the CE within the abstracts.

We applied the same methodology for keyword analysis. This was accomplished by employing a predefined dictionary of keywords, which had been developed based on an exhaustive review of the extant literature on the CE [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. In this study, we identified 24 terms that were used to construct our quantitative research related to CE.The dictionary served as the foundation for the analysis and was constructed to account for the linguistic diversity inherent in CE research. It included synonyms, variations in verbal forms, and other alternative expressions commonly used in the field.

In order to ensure accuracy and relevance, the analysis adhered to three key criteria. Firstly, whole-word matching was employed, focusing on complete words to prevent partial matches from yielding irrelevant results. Secondly, case sensitivity was considered, with variations in uppercase and lowercase being taken into account to capture differences in formatting and emphasis within abstracts. Thirdly, regular expressions were applied to identify all variations of predefined terms, ensuring flexibility in recognizing synonymous or rephrased expressions.

In addition to identifying terms related to the CE, the analysis also focused on terms associated with horticulture, thereby creating a comprehensive framework to explore the intersection of these two domains. By leveraging these systematic approaches, the study ensured a robust and nuanced interpretation of the textual data, capturing the depth and diversity of concepts within the analysed publications. By combining frequency analysis with relational mapping, this approach provides a robust framework for understanding the evolution of research trends, highlighting key areas of focus and emerging opportunities for further investigation.

3. Results

First was examined the keywords to determine their frequency, relationships and significance in the literature reviewed. This step provided information on the main themes and research trends as represented in the keyword mapping process.The analysis was then extended to the abstracts of the articles. This deeper exploration allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of the context and focus of the studies, going beyond the superficial representation provided by the keywords. The integration of these two levels of analysis - keywords and abstracts - provided a holistic view of the research landscape, offering valuable insights into the interrelated topics of CE and horticulture.

3.1. Keyword Map

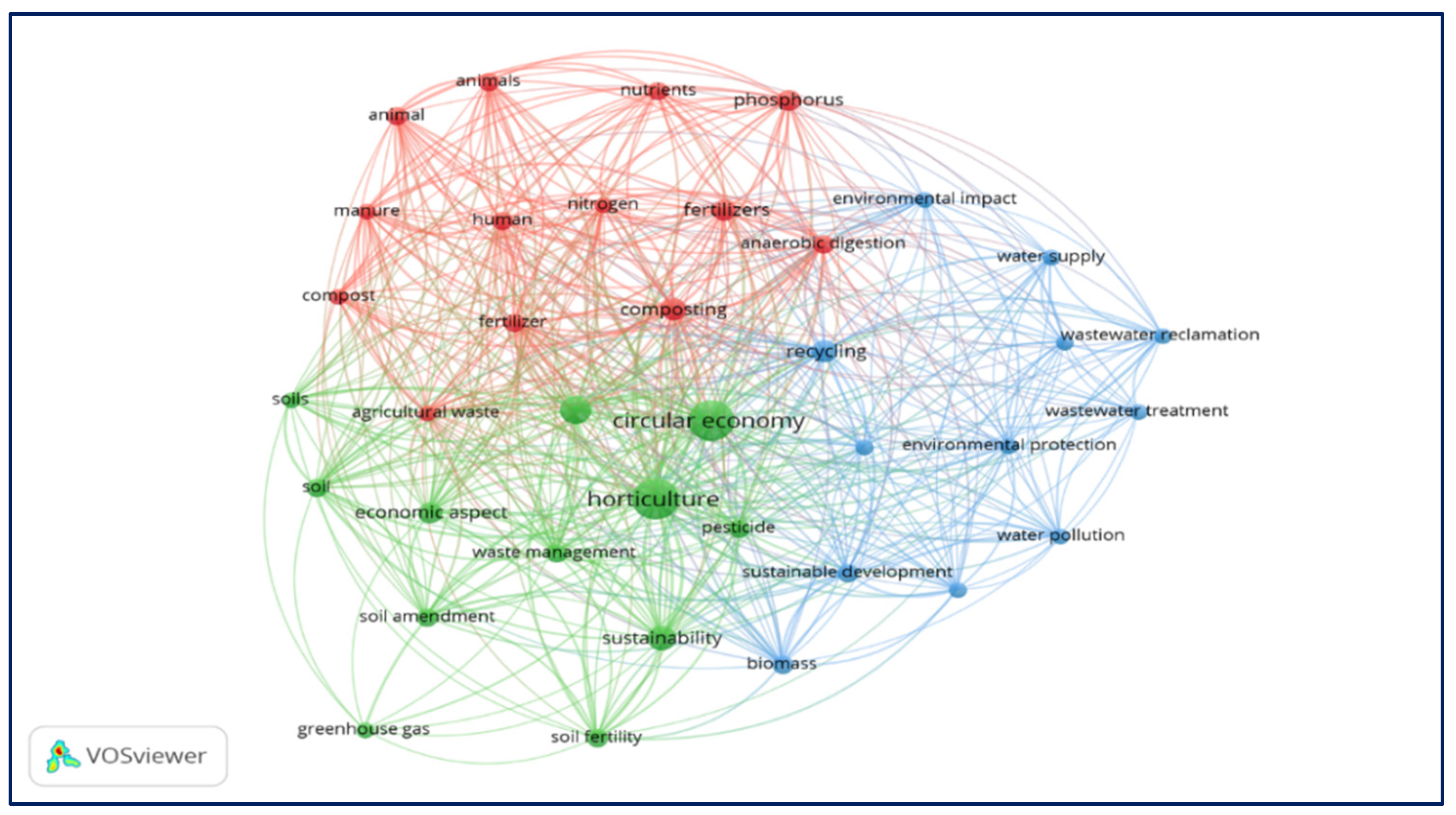

The relative frequency of use of keywords and the relationships between them in the reviewed publications was analyzed in a word map, shown in

Figure 2.

The larger the circle, the more frequently a given word appears in the keywords of the reviewed articles.

Figure 2 also highlights the relationships between different keywords, with “circular economy” and “horticulture” are those with a higher presence. This is expected considering that they are part of the bibliographic search terms. The map generated is related to the clusters created by the software. (

Table 1).

Analyzing groups and relationships between keywords allows for meaningful interpretations of themes and focus areas on the research landscape. Each group represents a distinct thematic area, with clustering indicating shared concepts or topics of academic interest. The relationships between keywords within a group reveal interdependencies and synergies, providing an integrated perspective on aspects of the CE and horticulture. The prominence of specific keywords within a cluster indicates their importance in driving research trends and identifies emerging areas of focus aligned with sustainability, resource efficiency, and environmental protection. Understanding cluster relationships helps researchers to identify gaps in knowledge and under-explored areas for future research. Clusters not only visualize keyword relationships but also serve as a framework for guiding further research. The clusters are analyzed and interpreted to provide a deeper understanding of their thematic focus and relevance.

1st Cluster: Focuses on nutrient recycling, where waste is managed in such a way that it is converted into resources, minimizing environmental impact and promoting sustainability. It highlights strategies to convert waste into valuable fertilizers, thereby minimizing environmental impact and promoting sustainability, aligning with broader goals of reducing ecological footprints of the chemical fertilizers use. In this cluster, animals are critical players, converting vegetable biomass into organic fertilizer. Composting is the other way to transform animal effluents and vegetable waste in fertilizers.

2nd Cluster: Reflects the interconnection between agricultural production and sustainability, with special attention to the soil health. It emphasizes the importance of practices that minimize environmental impact while promoting efficient resource use, with the CE being a key approach to achieving more sustainable and responsible horticulture. This perspective encourages the adoption of regenerative practices that enhance resilience and efficiency within agricultural systems by promoting resource efficiency, waste reduction, and the regeneration of natural systems, the CE balances environmental conservation and economic viability. It supports the transition to greener horticulture and emphasizes the importance of resilience and long-term sustainability in the agricultural sector.

3rd Cluster: The valorization of waste is the core of this cluster, reducing its environmental impacts. It emphasizes the importance of sustainable management of water and land resources in horticulture, as well as the role of bioenergy, recycling and the valorization of agricultural by-products in the CE as key components. It also highlights the need to protect the environment and minimize the impact of agriculture on ecosystems. The focus is on promoting long-term sustainable development by ensuring that horticultural practices are in line with environmental protection and resource optimization. and emphasizing the urgent need to protect natural ecosystems from the negative impacts of agriculture. This includes reducing pollution, preserving biodiversity and promoting practices that regenerate rather than deplete natural resources. The overall aim is to enable sustainable development that meets today’s needs while safeguarding the environment for future generations

3.2. Abstracts Map

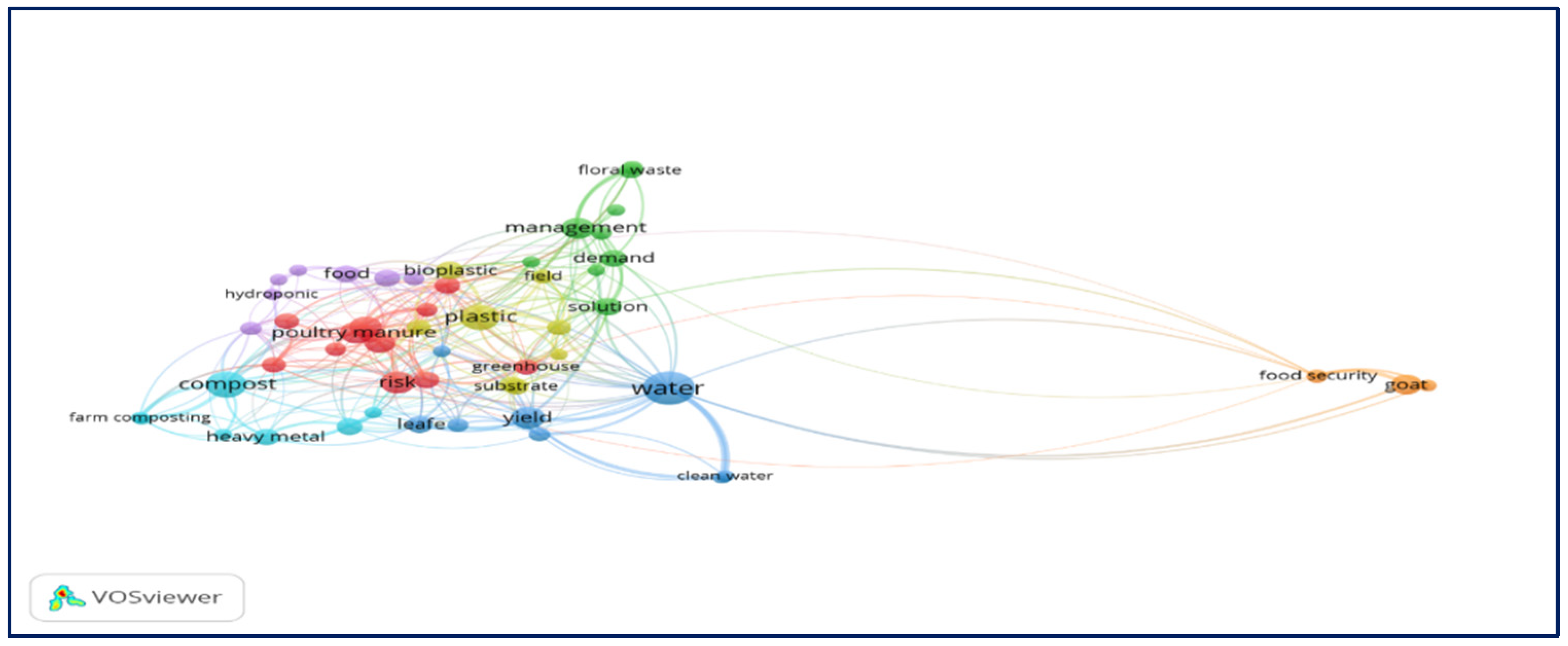

The first step was analysis the relative frequency of words used in the abstracts. This analysis provided insight into the prominence of specific terms and concepts within the field. Following this, the relationships between keywords were examined to understand how they interact and cluster within the research landscape. These findings were visually represented in a word map, shown in

Figure 3.

The word map illustrates both the frequency of individual keywords and the strength of their relationships, offering a clear depiction of the central themes and interconnections shaping the discourse on CE and horticulture. As referred to above, the larger the circle, the more frequently a given word appears in the keywords of the abstracts of the articles reviewed.

Figure 3 also shows the relationships between the different keywords found in the abstracts of the publications. The main keywords found were “water”, “compost”, “plastic”, “poultry manure” and “management”.

As with the analysis of keywords found in the reviewed articles, the clusters generated by the software were also examined, this time focusing on the abstract texts. This examination is particularly significant in determining whether, beyond the keywords assigned by the authors and the inclusion of these articles in the categories specified in the methodology, the abstracts also incorporate terms relevant to the context. Specifically, the analysis sought to identify whether the abstracts include references to “circular,” “circular economy,” and “horticulture,” aligning with the themes under investigation. The analysis, conducted using VOSviewer and in accordance with the methodology presented above, resulted in the generation of a map (

Figure 3) comprising seven clusters (

Table 2).

1st Cluster: The focal point of this cluster is the practices, challenges, and opportunities in modern horticulture through the lens of sustainability and the CE. A win-win relationship between animal and plant production is fostered, where outputs from one system are inputs for the other, with the objective of minimizing waste and maximizing resource efficiency. Strategies for reducing waste, recycling resources, and adopting environmentally friendly innovations in cultivation techniques are examined. The integration of advanced technologies and knowledge is central to the cluster’s objective of optimizing production processes, whilst also fostering environmental stewardship and promoting the interconnectedness of agricultural systems within a sustainable framework. This cluster includes the novelty aquaponic system, where vegetable production is integrated with aquiculture. This system promotes the reduction of waste, the circularity of nutrients, and the symbioses of the two productions.

2nd Cluster: This cluster is related with floriculture production and sustainability. The transformation of floral and plant waste into valuable resources such as compost and bioenergy foster eco-friendly practices, aligned with nature-based solutions. Sustainable methodologies, including precision agriculture, organic farming, and lifecycle analysis, propel this transition, achieving a balance between economic productivity and ecological preservation. The integration of scientific innovations, policies, and stakeholder collaboration is pivotal in advocating for greener, resilient systems that meet the increasing demand for sustainable products and ensure long-term agricultural viability.

3rd Cluster: This cluster emphasizes the critical synergy between water quality and recycling, resource management, and sustainability in horticulture. It highlights the integration of alternative resources and by-products, such as microalgae and struvite, into horticultural practices. Microalgae, known for capturing carbon dioxide and producing biomass, serve as sustainable sources of nutrients and biofertilizers, while struvite, a phosphorus-rich mineral recovered from wastewater, supports the CE by recycling essential nutrients. The cluster also underscores advanced irrigation techniques, such as precision drip systems and water recycling technologies, to optimize water usage. By prioritizing resource efficiency, recycling, and environmental stewardship, this cluster advocates for scalable, eco-friendly solutions that align horticultural productivity with long-term sustainability and resilience.

4th Cluster: This cluster of research examines the intricate interconnections between the materials employed in horticulture, including plastics, substrates, and other inputs, and their management, processing, and ultimate impact on sustainability. It addresses the growing concern over the environmental consequences of traditional materials, including conventional plastics and peat, which contribute to pollution and ecological degradation. The main aim of this cluster is the integration of bioplastics as an innovative and sustainable alternative. Bioplastics, derived from renewable biological resources, have the potential to replace traditional petroleum-based plastics, thereby reducing greenhouse gas emissions and reliance on finite resources. Furthermore, this cluster emphasis’s the importance of advanced material management strategies, including recycling, upcycling and the development of biodegradable products.

5th Cluster: This cluster underscores the interconnectedness of horticultural production, sustainable consumption, and the CE, exploring the potential of responsible food production – encompassing the creation of added value, utilization of bio-stimulants, and the health of the agroecosystems. Concomitantly, conscious food consumption assumes a pivotal role in effecting closure within the loop of the CE. The integration of bio-stimulants, which enhance plant growth while reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers, is a key innovation that the cluster highlights as being vital to achieving a sustainable future.

6th Cluster: Reflects the importance of organic waste management and soil quality in horticulture. It explores practices such as on-farm composting and the application of compost to enhance soil fertility and structure, while simultaneously reducing pollution. On-farm composting and the use of compost can improve soil quality and reduce pollution, while concerns about heavy metals and disease underline the need for sustainable practices. By addressing these issues, the cluster aims to create a more resilient and environmentally sustainable horticultural system.

7th Cluster: This cluster is concerned with the interrelated topics of food security, urban food production, and the role of animals, such as goats, in more sustainable agricultural systems. The necessity for agricultural practices that simultaneously address the population’s food requirements and promote sustainability and resource efficiency is emphasized. By integrating urban farming, small-scale livestock systems and sustainable resource management, the cluster identifies innovative strategies to meet the food demands of growing urban populations. Furthermore, it emphasizes the necessity of achieving a balance between food production and environmental conservation in order to ensure global food security in an increasingly urbanized world.

3.3. Quantitative Analysis of Keywords and Abstracts

A quantitative analysis of terms related to the CE in the abstracts and keywords of academic publications was conducted (

Table 3). The results reveal a clear upward trend in research output over the years, reflecting a growing academic interest in the CE. Specifically, the number of articles analyzed increased progressively, from only two publications in 2016 to 44 in 2024. This growth highlights an expanding focus on sustainability-related research and its associated practices in the field of CE. Comparing the trienniums 2016-2018 and 2021-2023, the number of articles analyzed increased almost nine times, while the Horticulture publication increased only 33.3% during this period [

42].

Terms such as “Circular economy” and “Sustainability” are the most used, with a notable increase in the number of mentions over the years, especially in abstracts (31 mentions for “Circular economy” in 2024). Other key terms such as “reduce”, “recover” and “recycle” also show significant increases, indicating a continued focus on reduction and reuse practices, signaling a sustained focus on fundamental CE principles, specifically reduction and reuse strategies. This growing prevalence underscores their central role in framing the discussion on CE practices. However, the analysis also highlighted the relatively low use of emerging and complementary concepts such as “biomimicry”, “permaculture” and “carbon farming”, which barely appear in the publications, which may reflect the lower integration of these concepts into the academic discourse on the CE or their recent incorporation into the topic. These terms appear infrequently in the publications analyzed, which may indicate limited integration into the dominant academic discourse on the CE. Alternatively, their sparse occurrence may reflect their recent introduction into the field or a niche that has yet to gain widespread recognition.

Finally, although there is a gradual diversification of terms specific to both CE and horticultural topics, especially in abstracts, reaching up to 11 terms in 2024. The total number of terms used in abstracts shows a constant increase year after year, reaching 146 mentions in 2024, while keywords only reach 20 in the same year. Overall, the analysis suggests that while the CE continues to gain traction in academic literature, there is considerable room for integration of emerging concepts and expansion of the use of specific terminology, particularly in keyword selection. In addition to the terms listed in

Table 3, the following keywords were also included in the search: repair, refuse, regenerative agriculture, biomass valorization, zero waste farming, carbon farming, permaculture, and biomimicry. However, none of these terms were found during the search, and as such, they are not included in the

Table 3.

4. Discussion

This article presents a bibliometric analysis with the objective of exploring the connection between the concepts of the circular economy and horticulture. The analysis focuses on the relationship between keywords, abstracts, and the core principles of the circular economy. Additionally, the study seeks to ascertain whether the terminology employed in the research is consistent with the keywords, abstract content, and circular economy concepts.

Table 4 presents a synthesis of the results of this research.

The analysis of article abstracts reveals a clear increase in the use of terms related to the 4Rs (reduce, reuse, recover and recycle), especially after 2019. Of these, the term “reduce” is the most frequently mentioned, indicating a focus on the minimization of resource consumption in horticultural practices. It is related to the concept of eco-efficiency, e.g.; using fewer natural resources to obtain one unit of product. Furthermore, terms such as “repair” are conspicuous by their absence, which is likely attributable to the inherent characteristics of horticulture, where repair concepts are less applicable than in mechanical or product-focused domains.

Furthermore, the analysis demonstrates that broader CE-related terms, such as “sustainable”, “sustainability” and “circular economy”, only sporadically appear in the literature up until 2020. Despite an examination of 221 articles with the keyword’s “horticulture” and “circular economy”, it can be concluded that the integration of CE terminology remains limited during this period. This indicates that these concepts are not yet fully embedded in horticultural research. It is noteworthy that the terms “circular economy” and “sustainability” appear in both the keywords and abstracts, though they are more frequent in the latter. This higher frequency indicates that these terms serve as anchor concepts, deliberately selected to attract researchers interested in these specific topics. Such anchor terms play an important role in enhancing the visibility and discoverability of articles in academic databases, thereby extending their reach within relevant academic communities. There is a great association, in each year, between the number of abstracts with the term “circular economy” and the number with the term “sustainable” (or “sustainability”). The results show the emerge of the circular bioeconomy since 2019 but only a few times and not consistently.

Nevertheless, the relatively low representation of CE-related terms in the keywords indicates that horticulture research is not yet fully positioned within the broader CE framework. While the abstracts frequently address themes such as resource efficiency, waste reduction, and the 4Rs, this alignment is not consistently reflected in the keywords. However, it is clear the importance of reduce, recycle, recover and reuse, demonstrated by the presence of these terms in the abstracts. This gap presents a valuable opportunity for researchers to more clearly establish a connection between their work and the fundamental principles of the CE. By selecting more specific and representative keywords, authors could enhance the visibility of their research and further integrate CE concepts into horticultural studies. It would be beneficial for future research to improve the alignment between the content of the abstracts and the selection of keywords. This would ensure a stronger connection to CE principles and enhance the overall impact of the research.

There is a strong presence of the 4Rs, especially after 2019. The most present term (in the abstracts) is “reduction” (95 times), followed by “recycling” (74 times) and, to a lesser extent, the terms “recover” and “reuse” (53 and 47 times, respectively). These results indicate an alignment between circularity, the 4Rs and sustainability, and the prioritization of actions in research into “Circular Horticulture”. We can conclude that there is a priority to reduce the use of inputs (namely those higher impact in environmental, such as nitrogen, phosphorus and pesticides), followed by a concern with the recycling of materials, especially nutrients.

The cluster visualization shows the main lines of research in “Circular Horticulture”, highlighting composting and the circularity of nutrients through animal production, waste valorization, soil regeneration and soil health, water quality and water recycling, the problem of plastics, and the sustainability of food production and consumption. However, these clusters are not very consistent within each cluster, in the case of abstracts, or there is a great diffusion between the various clusters, as can be seen by viewing the keyword map.

The results of this study align with those of other recent research, which has also observed a growing trend in the popularity of the concept of the CE over time. However, the concept is often vague and unclear, and it is still in the phase of validity challenges and development, heading in a progressive and promising direction [

11,

43]. Furthermore, other works indicate that this concept is still in the explanatory phase and lacks a confirmatory approach and empirical validation [

44]. There is also a notable lack of methodologies and indicators that allow for the assessment of the application of the CE across different sectors [

45,

46].

The exploration of the CE as a model for promoting sustainability continues, and many researchers concur that its full implementation necessitates a more profound comprehension of its underlying principles, more precise definitions, and more robust methods for measuring impact. The ongoing challenge is twofold: to refine the concept and to create actionable frameworks that can evaluate and enhance the CE in various domains, whether in business, agriculture, or urban planning. As research progresses, it is becoming evident that the success of the CE will depend on its adaptability to different contexts and its ability to provide measurable, real-world benefits

5. Conclusions

Considering that this study aimed to analyse the role of the CE in scientific research in horticulture, it is observed that although the literature review was conducted using the keywords horticulture and circular economy, it is only after 2019 that the term CE appears more than 10 times in the abstracts of research papers. The association among the frequency of CE, the 4Rs and sustainability suggest that the terminology associated with the CE is being used as a way of linking research to sustainability and CE concepts. However, these economic concepts do not necessarily appear explicitly in the abstracts themselves.

This complexity highlights the need for further research to better understand how authors integrate and explore CE concepts in their research. Furthermore, there is a notable incoherence between the concepts highlighted in the bibliographic research, the actual keywords chosen by the authors, and the broader academic curricula. This inconsistency may reflect a gap in the adoption or understanding of the CE within horticultural research, warranting a deeper exploration of how sustainability is incorporated into research focus, methodology and outcomes.

In conclusion, while there is growing interest in linking horticultural research to CE principles, integration remains partial and inconsistent. Addressing this gap requires a more systematic analysis of how the circular economy framework is embedded in research practices, conceptual frameworks and academic curricula.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Emilio Hernández López; Data curation; Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Emilio Hernández López; Formal analysis; Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Emilio Hernández López; Funding acquisition: Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Investigation; Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Emilio Hernández López; Pedro Reis; Methodology: Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Emilio Hernández; Project administration; Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Resources: Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Software: Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Emilio Hernández López; Supervision; Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Pedro Reis; Validation: Pedro Reis; Visualization: Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Emilio Hernández López; Pedro Reis; Writing Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Emilio Hernández López; Writing – review and editing; Maria de Fátima Oliveira; Pedro Reis.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by [CERNAS (UIDB/00681/2020; DOI: 10.54499/UIDP/00681/2020].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) for the financial support to the Research Centre for Natural Resources, Environment and Society — CERNAS (UIDB/00681; DOI: 10.54499/UIDP/00681/2020). We acknowledge FCT funding to “GREEN-IT Bioresources for Sustainability” Unit, (DOI 10.54499/UIDB/04551/2020 and DOI:10.54499/UIDP/04551/2020). Emilio Hernández López, thank to Applied Research Institute (i2A) and to Coimbra Agriculture School (ESAC) of the Polytechnic University of Coimbra for their support throughout the development of this article during their work stay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- OECD. Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060: Economic Drivers and Environmental Consequences, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2019. [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Decoupling natural resource use and environmental impacts from economic growth, A Report of the Working Group on Decoupling to the International Resource Panel. Fischer-Kowalski, M.; Swilling, M.; von Weizsäcker, E.U.; Ren, Y.; Moriguchi, Y.; Crane, W.; Krausmann, F.; Eisenmenger, N.; Giljum, S.; Hennicke, P.; Romero Lankao, P.; Siriban Manalang, A.; Sewerin, S, United Nations Environment Programme, 2011. ISBN: 978-92-807-3167-5. Available online: https://www.resourcepanel.org/reports/decoupling-natural-resource-use-and-environmental-impacts-economic-growth.

- UNEP. Resource Efficiency: Potential and Economic; Implications. A report of the International Resource Panel. Ekins, P.; Hughes, N.; et al, 2017. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/resource-efficiency-potential-and-economic-implications-international-resource.

- DGCEP. Circular economy: definition, importance and Benefits, Directorate General for Communication European Parliament (2023) Article24-05-2023, 2023. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/pdfs/news/expert/2023/5/story/20151201STO05603/20151201STO05603_en.pdf.

- Feng, Z.; Yan, N. Putting a Circular Economy Into Practice in China. Sustainability Science, 2007, 2 (1), 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, S. I.; Yoshida, H.; Hirai, Y.; Asari, M.; Takigami, H.; Takahashi, S.; Chi, K. International comparative study of 3R and waste management policy developments. Journal of material cycles and waste management 2011, 13, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, F. A global redesign? Shaping the circular economy. Energy, Environment and Resource Governance, 2012, EERG BP. Available online: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Energy%2C%20Environment%20and%20Development/bp0312_preston.pdf.

- Reh, L. Process engineering in circular economy. Particuology, 2013 11(2), 119-133. [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Heshmati, A.; Geng, Y.; Yu, X. A review of the circular economy in China: moving from rhetoric to implementation. Journal of cleaner production 2013, 42, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, L. A. Las amenazas globales, el reciclaje de residuos y el concepto de economía circular. Revista argentina de microbiología, 2014, 46(1), 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, conservation and recycling 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariatli, F. Linear economy versus circular economy: a comparative and analyzer study for optimization of economy for sustainability. Visegrad Journal on Bioeconomy and Sustainable Development, 2017, 6(1), 31-34. 10.1515/vjbsd-2017-0005.

- UN. Circular Economy and Agribusiness Development. (s.d). Available online: https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/files/2020-09/Circular_economy_in_AGR.pdf.

- NASEM. The Challenge of Feeding the World Sustainably: Summary of the US-UK Scientific Forum on Sustainable Agriculture. 2021, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P. The World’s Water. The Biennial Report on Freshwater Resources. 2011, Vol. 7, SERBIULA (sistema Librum 2.0). [CrossRef]

- EC: European Environment Agency, Joint Research Centre, Arias-Navarro C, Baritz R, Jones A. The state of soils in Europe: fully evidenced, spatially organised assessment of the pressures driving soil degradation. Publications Office of the European Union; 2024.

- Jaskani, J.; Khan, A. Horticulture: An Overview. In book: Horticulture, Science & Technology Publisher: 2021, University of Agriculture Faisalabad Pakistan. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348621593_Horticulture_An_Overview#fullTextFileContent.

- EC. EIP-AGRI factsheet: Circular horticulture. European Commission, 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eip/agriculture/sites/default/files/eipagri_factsheet_circular_horticulture_2019.

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. Journal of Cleaner production 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The circular economy: an interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. Journal of business ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Muñoz, F.; Aznar-Sánchez, A.; López-Felices, B.; Román-Sánchez, M. Circular economy in agriculture. An analysis of the state of research based on the life cycle. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2022, 34, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, R.; Russo, S. Marcas como um indicador: revisão sistemática e análise bibliométri, ca da literatura. Biblios, 2018 (71), pp. 50-67. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Silva, W.; Silva, G.; Cruz, C.; Oliveira, L.; Mann, R.; Paixão, A. Estudo bibliométrico e análise de tendências de pesquisa em indicações geográficas. Research, Society and Development, 2020, 9. 10.33448/rsd-v9i10.9146.

- Börner, K.; Chen, C.; Boyack, K.W. Visualizing knowledge domains. Ann. Rev. Info. Sci. Tech. 2003, 37, 179–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delen, I.; Sen, N.; Ozudogru, F.; Biasutti, M. Understanding the Growth of Artificial Intelligence in Educational Research through Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability, 2024, 16(16), 6724. [CrossRef]

- Camón, E.; Celma, D. Circular Economy. A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability, 2020, 12(16), 6381. [CrossRef]

- Dominko, M.; Primc, K.; Erker, R.; Kalar, B. A bibliometric analysis of circular economy in the fields of business and economics: towards more action-oriented research. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 2022, 25. 10.1007/s10668-022-02347-x.

- Page, J.; McKenzie, E.; Bossuyt, M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, C.; Mulrow, D.; Shamseer L, Tetzlaff, M.; Akl, A.; Brennan, E.; Chou R, Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.; Li T, Loder, W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, A.; Stewart, A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A.; Welch, A.; Whiting P, Moher D.. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 Mar 29; 372:71. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Van Eck, N, Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 2010. 84(2), pp523-538. [CrossRef]

- Delen, I.; Sen, N.; Ozudogru, F.; Biasutti, M. Understanding the Growth of Artificial Intelligence in Educational Research through Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability, 2024, 16(16), 6724. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, J.; Waltman, L. CitNetExplorer: A new software tool for analyzing and visualizing citation networks. Journal of informetrics, 2014, 8(4), pp. 802-823. [CrossRef]

- Cobo, J.; López-Herrera, A. G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. SciMAT: A new science mapping analysis software tool. Journal of the American Society for information Science and Technology, 2012. 63(8), pp. 1609-1630. [CrossRef]

- Team, S. Science of science (Sci2) tool. Indiana University and SciTech Strategies, 2009, 379. Available online: https://sci2.cns.iu.edu/user/index.php (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. Journal of the American Society for information Science and Technology, 2006, 57(3), pp. 359-377. [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of informetrics, 2017, 11(4), pp. 959-975. [CrossRef]

- Börner, K.; Chen, C.; Boyack, W. Visualizing knowledge domains. Ann. Rev. Info. Sci. Tech.; 2003, 37: pp. 179-255. [CrossRef]

- Ellen Macarthur Foundation. Delivering circular economy. A toolkit for policy makers, 2015a. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-toolkit-for-policymakers (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Growth within: A circular economy vision for a competitive Europe, 2015b. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/growth-within-a-circular-economy-vision-for-a-competitive-europe (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Pieroni, M.; Pigosso, D.; Soufani, K. Circular business models: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020, 277. 123741. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959652620337860?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef]

- Dimitra I.; Maria K.; Michail, V,; Labros.; V. Circular economy: A multilevel approach for natural resources and wastes under an agri-food perspective. Water-Energy Nexus, 2024, Volume, 7, pp 103-123. [CrossRef]

- Everett, E. Combining the Circular Economy, Doughnut Economy, and Permaculture to Create a Holistic Economic Model for Future Generations. Environmental Sciences Proceedings, 2022, 15(1), 19. [CrossRef]

- SCImago. SCImago Journal: World Report, 2025. Available online: https://www.scimagojr.com/worldreport.php?area=1100 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Upadhayay, S.; Alqassimi, O.; Khashadourian, E.; Sherm, A.; Prajapati, D. Development in the Circular Economy Concept: Systematic Review in Context of an Umbrella Framework. Sustainability, 2024, 16(4), 1500. [CrossRef]

- Homrich, S.; Galvão, G.; Abadia, G.; Carvalho, M. The circular economy umbrella: Trends and gaps on integrating pathways. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 175, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassanelli, C.; Rosa, P.; Rocca, R.; Terzi, S. Circular economy performance assessment methods: A systematic literature review. Journal of cleaner production 2019, 229, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, T.; Dantas, T.; Soares, R. Nano and micro level circular economy indicators: Assisting decision-makers in circularity assessments. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2021, 26, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).