Submitted:

15 January 2026

Posted:

16 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

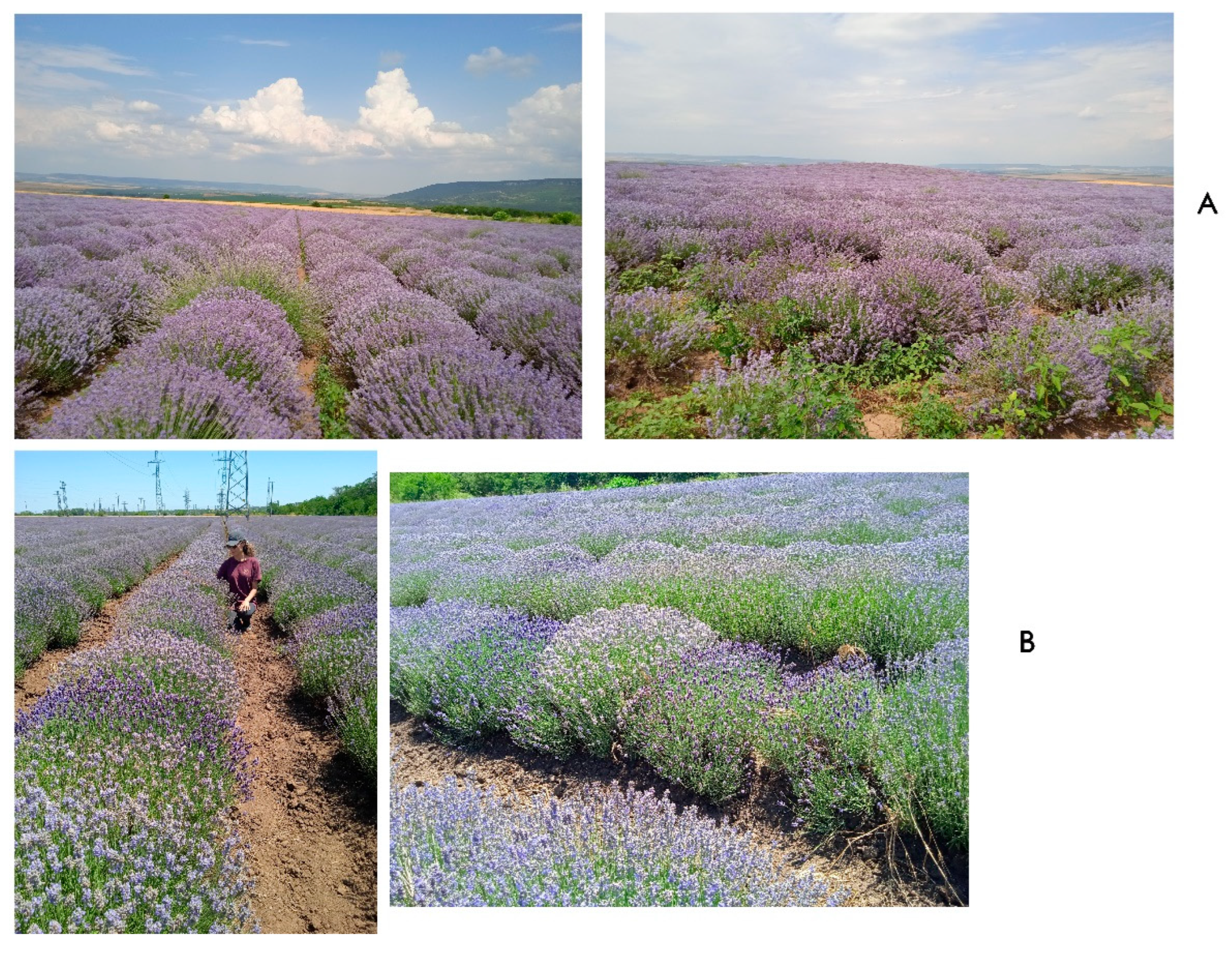

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. PCR Amplification

2.3. Genetic Diversity

2.4. Data Analysis

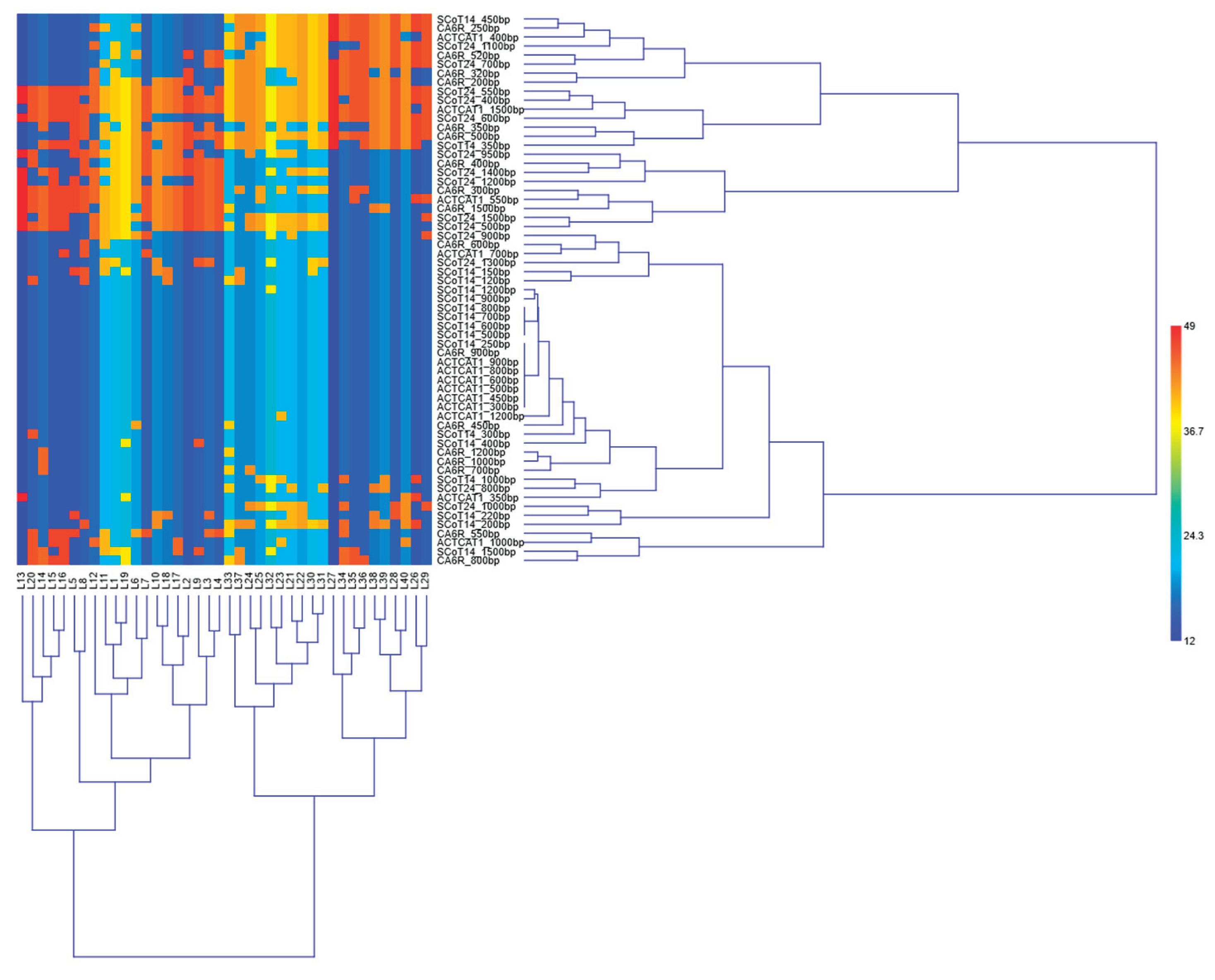

3. Results

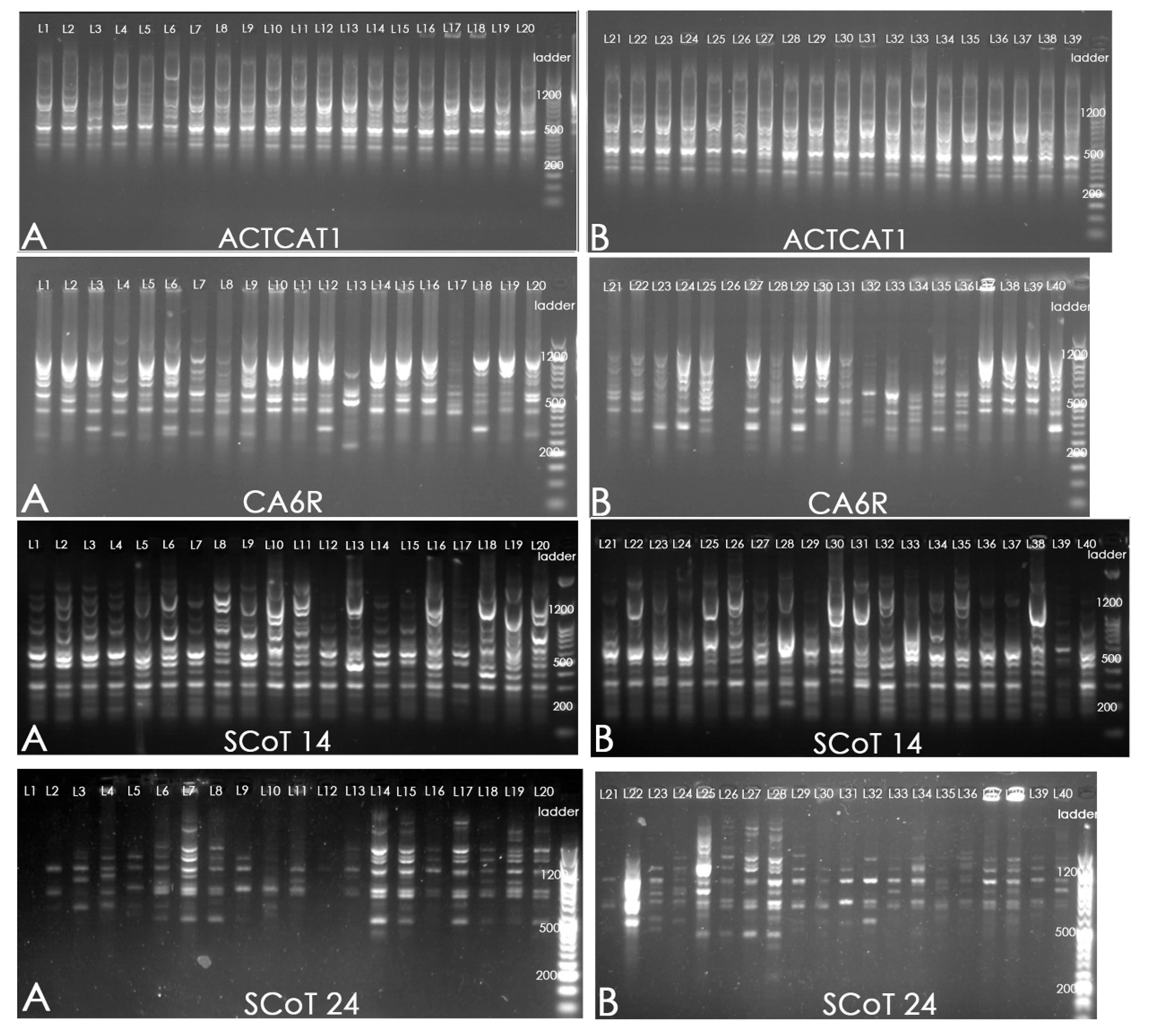

| Primers | Band size, bp | TB | PB | MB | %PB | EMR | PIC | Rp | MI |

| ACTCAT1 | 300-1500 | 13 | 7 | 6 | 53.84 | 15.9 | 0.25 | 16.1 | 4.4 |

| CA6R | 200-1500 | 17 | 16 | 1 | 94.11 | 16.8 | 0.50 | 17.0 | 7.5 |

| SCoT 14 | 120-1500 | 17 | 11 | 6 | 55.00 | 21.8 | 0.25 | 19.3 | 5.5 |

| SCoT 24 | 400-1500 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 100 | 19.8 | 0.69 | 18.9 | 13.6 |

| Total | 61 | 48 | 13 | ||||||

| Mean | 75.7 | 18.6 | 0.42 | 15.3 | 7.8 |

4. Discussion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atanasova, M.; Nedkov, N. Essential Oil and Medicinal Crops. Modern Cultivation Technologies. Competitiveness. Funding.; (In Bulgarian). Cameo: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ražná, K.; Čerteková, S.; Štefúnová, V.; Habán, M.; Korczyk-Szabó, J.; Ernstová, M. Lavandula spp. diversity assessment by molecular markers as a tool for growers. Agrobiodiversity for Improving Nutrition, Health and Life Quality 2023, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, R.; Kirchev, H.; Delibaltova, V.; Chavdarov, P. Investigation of Some Agricultural Performances of Lavender Varieties. Yuzuncu Yıl University Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2021, 31, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozuharova, E.; Simeonov, V.; Batovska, D.; Stoycheva, C.; Valchev, H.; Benbassat, N. Chemical composition and comparative analysis of lavender essential oil samples from Bulgaria in relation to the pharmacological effects. Pharmacia 2023, 70, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanev, S.; Angelova, D. Peculiarities in the flowering of the Bulgarian varieties of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.). Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2023, 99, 3375–3385. [Google Scholar]

- Adaszyńska-Skwirzyńska, M.; Zych, S.; Bucław, M.; Majewska, D.; Dzięcioł, M.; Szczerbińska, D. Evaluation of the antibacterial activity of gentamicin in combination with essential oils isolated from different cultivars and morphological parts of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) against selected bacterial strains. Molecules 2023, 28, 5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Shukla, S.P.; Mathur, A.; Chanotiya, C.S.; Mathur, A.K. Genetic fidelity of long-term micropropagated Lavandula officinalis Chaix.: an important aromatic medicinal plant. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2015, 120, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Salama, A.M.; Abou El-Leel, O.F. Analysis of genetic diversity of Lavandula species using taxonomic, essential oil and molecular genetic markers. Sciences 2017, 7, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Babanina, S.S.; Yegorova, N.A.; Stavtseva, I.V.; Abdurashitov, S.F. Genetic stability of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) plants obtained during long-term clonal micropropagation. Russian Agricultural Sciences 2023, 49, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova, A.; Balinova-Tcvetkova, A. Lavender: Obtaining Essential Oil Products in Bulgaria.; (In Bulgarian). UFT Academic Publishing House: Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adal, A.M.; Demissie, Z.A.; Mahmoud, S.S. Identification, validation and cross-species transferability of novel Lavandula EST-SSRs. Planta 2015, 241, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgieva, P.; Rusanov, K.; Rusanova, M.; Kitanova, M.; Atanassov, I. Development of SSR markers and construction of a genetic linkage map in lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.). Preprints 2025, 2025011933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharan, H.; Pandey, P.; Singh, S. Genetic Resources and Breeding Strategies for Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.). In Ethnopharmacology and OMICS Advances in Medicinal Plants; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zagorcheva, T.; Stanev, S.; Rusanov, K.; Atanassov, I. SRAP markers for genetic diversity assessment of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) varieties and breeding lines. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2020, 34, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ražná, K.; Čerteková, S.; Štefúnová, V.; Habán, M.; Korczyk-Szabó, J.; Ernstová, M. Lavandula spp. diversity assessment by molecular markers as a tool for growers. Agrobiodiversity for Improving Nutrition, Health and Life Quality 2023, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fopa Fomeju, B.; Brunel, D.; Bérard, A.; Rivoal, J.B.; Gallois, P.; Le Paslier, M.C.; Bouverat-Bernier, J.P. Quick and efficient approach to develop genomic resources in orphan species: Application in Lavandula angustifolia. Plos one 2020, 15, e0243853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, K.R.; Adal, A.M.; Upson, T.M.; Mahmoud, S.S. An assessment of plant DNA barcodes for the identification of cultivated Lavandula (Lamiaceae) taxa. Biocatalysis and agricultural biotechnology 2018, 16, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, R. The mitochondrial genome of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (Lamiaceae) sheds light on its genome structure and gene transfer between organelles. BMC genomics 2024, 25, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Lan. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the fragrant plant Lavandula angustifolia (Lamiaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2018, 3:1, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp Furan, M.; Yildiz, F.; Kaya, O. Exploring the Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Key Lamiaceae Species Uncovers the Secrets of Evolutionary Dynamics and Phylogenetic Relationships. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Mahdy, E.M.; Taha, H.S.; Eldomiaty, A.S.; Abd-Elfattah, M.A.; Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Hassanin, A.A. Genetic and morphological diversity assessment of five kalanchoe genotypes by SCoT, ISSR and RAPD-PCR markers. Plants 2022, 11, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amom, T.; Tikendra, L.; Apana, N.; Goutam, M.; Sonia, P.; Koijam, A.S.; Nongdam, P. Efficiency of RAPD, ISSR, iPBS, SCoT and phytochemical markers in the genetic relationship study of five native and economical important bamboos of North-East India. Phytochemistry 2020, 174, 112330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.Y.; He, X.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Lu, T.T.; Yang, J.H.; Huang, X.; Luo, C. Genetic diversity and relationship analyses of mango (Mangifera indica L.) germplasm resources with ISSR, SRAP, CBDP and CEAP markers. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 301, 111146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimuthu Somasundaram, S.; Durairajan, S.G.; Arumugam Palanivelu, S.; Rajendran, S.; Palani, D.; Arumugam, C.; Subbaraya, U. Evaluation of genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationship among the major banana varieties of north-eastern India using ISSR, IRAP, and SCoT markers. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 2024, 42, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badakhshan, H.; Kamangar, M.S.; Mozafari, A.A. Characterization of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) cultivars using SCoT, ISSR and IRAP markers. Crop Breeding Journal 2018, 8, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, N.; Lateef, D.; Rasul, K.; Rahim, D.; Mustafa, K.; Sleman, S.; Aziz, R. Assessment of genetic variation and population structure in Iraqi barley accessions using ISSR, CDDP, and SCoT markers. Czech Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding 2023, 59, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep Reddy, M.; Sarla, N.; Siddiq, E.A. Inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) polymorphism and its application in plant breeding. Euphytica 2002, 128, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.R.; de Sousa, V.A.; Guedes, F.L.; Diniz, F.M. Genetic diversity and association analysis of ISSR markers with forage production traits in pigeonpea. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2025, 72, 5853–5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittaragi, D.; Ananthan, M.; Venkatesan, K.; Mahalingam, L.; Jeyakumar, P.; Boopathi, N.M. Molecular characterization of curry leaf genotypes using ISSR markers. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 37763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, B.C.; Mackill, D.J. Start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism: a simple, novel DNA marker technique for generating gene-targeted markers in plants. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 2009, 27, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulpuri, S.; Muddanuru, T.; Francis, G. Start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism in toxic and non-toxic accessions of Jatropha curcas L. and development of a codominant SCAR marker. Plant science 2013, 207, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Nazari, L.; Kordrostami, M.; Safari, P. SCoT marker diversity among Iranian Plantago ecotypes and their possible association with agronomic traits. Scientia Horticulturae 2018, 233, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.X.; Shen, S.Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, L. Analysis of genetic diversity and development of a SCAR marker for green tea (Camellia sinensis) cultivars in Zhejiang Province: the most famous green tea-producing area in China. Biochemical Genetics 2019, 57, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Deng, L.; Zhu, K.; Shi, D.; Wang, F.; Cui, G. Evaluation of genetic diversity and population structure of Annamocarya sinensis using SCoT markers. Plos One 2024, 19, e0309283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; He, X.; Huang, X.; Lu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Luo, C. Cis-element amplified polymorphism (CEAP), a novel promoter-and gene-targeted molecular marker of plants. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2022, 28, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; He, X.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Lu, T.T.; Yang, J.H.; Huang, X.; Luo, C. Genetic diversity and relationship analyses of mango (Mangifera indica L.) germplasm resources with ISSR, SRAP, CBDP and CEAP markers. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 301, 111146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Pi, Z.; Wu, Z.; Li, S. Genetic diversity analysis of red beet germplasm resources using CEAP molecular markers. Sugar Tech 2024, 26, 1477–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, S.; Pi, Z.; Wu, Z. Genetic Diversity Analysis of Sugar Beet Polyembryonic Germplasm Resources Based on CBDP and CEAP Molecular Markers. Sugar Tech 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan-Ruiz, I.; Dendauw, J.; Vanbockstaele, E.; Depicker, A.; De Loose, M. AFLP markers reveal high polymorphic rates in ryegrasses (Lolium spp.). Molecular Breeding 2000, 6, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, J.; Damodar, R.K.; Nagaraja, G.M.; Sethuraman, B.N. Comparison of multilocus RFLPs and PCR-based marker systems for genetic analysis of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Heredity 2001, 86, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.K.; Chabane, K.; Hendre, P.S.; Aggarwal, R.K.; Graner, A. Comparative assessment of EST-SSR, EST-SNP and AFLP markers for evaluation of genetic diversity and conservation of genetic resources using wild, cultivated and elite barleys. Plant Science 2007, 173, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevost, A.; Wilkinson, M.J. A new system of comparing PCR primers applied to ISSR fingerprinting of potato cultivars. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 1999, 98, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GENALEX 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Molecular Ecology Resources 2006, 6, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D. A. Past: paleontological statistics software package for educaton and data anlysis. Palaeontologia electronica 2001, 4(1), 1. [Google Scholar]

- FARD, S.M.; Peyvandi, M.; Abbaspour, H.; Majd, A.; MARANDI, S.J. Genetic diversity and essential oil composition of Myrtus communis L. from Lorestan Province, Iran: Implications for conservation and utilization. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2025, 53, 14559–14559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Pereira, G.; Garrido, I.; Tavares-de-Sousa, M.M.; Espinosa, F. Comparison of RAPD, ISSR, and AFLP molecular markers to reveal and classify orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.) germplasm variations. Plos One 2016, 11, e0152972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgohary, M.E.; Salama, E.A.; El-wakil, H.M.; Abdelsalam, N.R.; Atia, M.A. Integrating SCoT, CBDP, and ISSR molecular markers for genetic diversity assessment and taxonomic authentication of some Asteraceae species in Egypt. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidyananda, N.; Jamir, I.; Nowakowska, K.; Varte, V.; Vendrame, W.A.; Devi, R.S.; Nongdam, P. Plant genetic diversity studies: insights from DNA marker analyses. International Journal of Plant Biology 2024, 15, 607–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hromadová, Z.; Gálová, Z.; Mikolášová, L.; Balážová, Ž.; Vivodík, M.; Chňapek, M. Efficiency of RAPD and SCoT markers in the genetic diversity assessment of the common bean. Plants 2023, 12, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etminan, A.; Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Noori, A.; Ahmadi-Rad, A.; Shooshtari, L.; Mahdavian, Z.; Yousefiazar-Khanian, M. Genetic relationships and diversity among wild Salvia accessions revealed by ISSR and SCoT markers. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2018, 32, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Huang, X.; Lu, Z.; Wang, P. Genetic Diversity of Distinctive-spicy Lavender Cultivars in Xinjiang Yili Revealed by ISSR Analysis. Xinjiang Agricultural Sciences 2016, 53, 716–720. [Google Scholar]

| Primer | Sequence (5' to 3') |

| ACTCAT1 | GCAGCTGCGTACTCATAA |

| CA6R | CACACACACACAR |

| SCoT 14 | ACGACATGGCGACCACCG |

| SCoT 24 | CACCATGGCTACCACCAT |

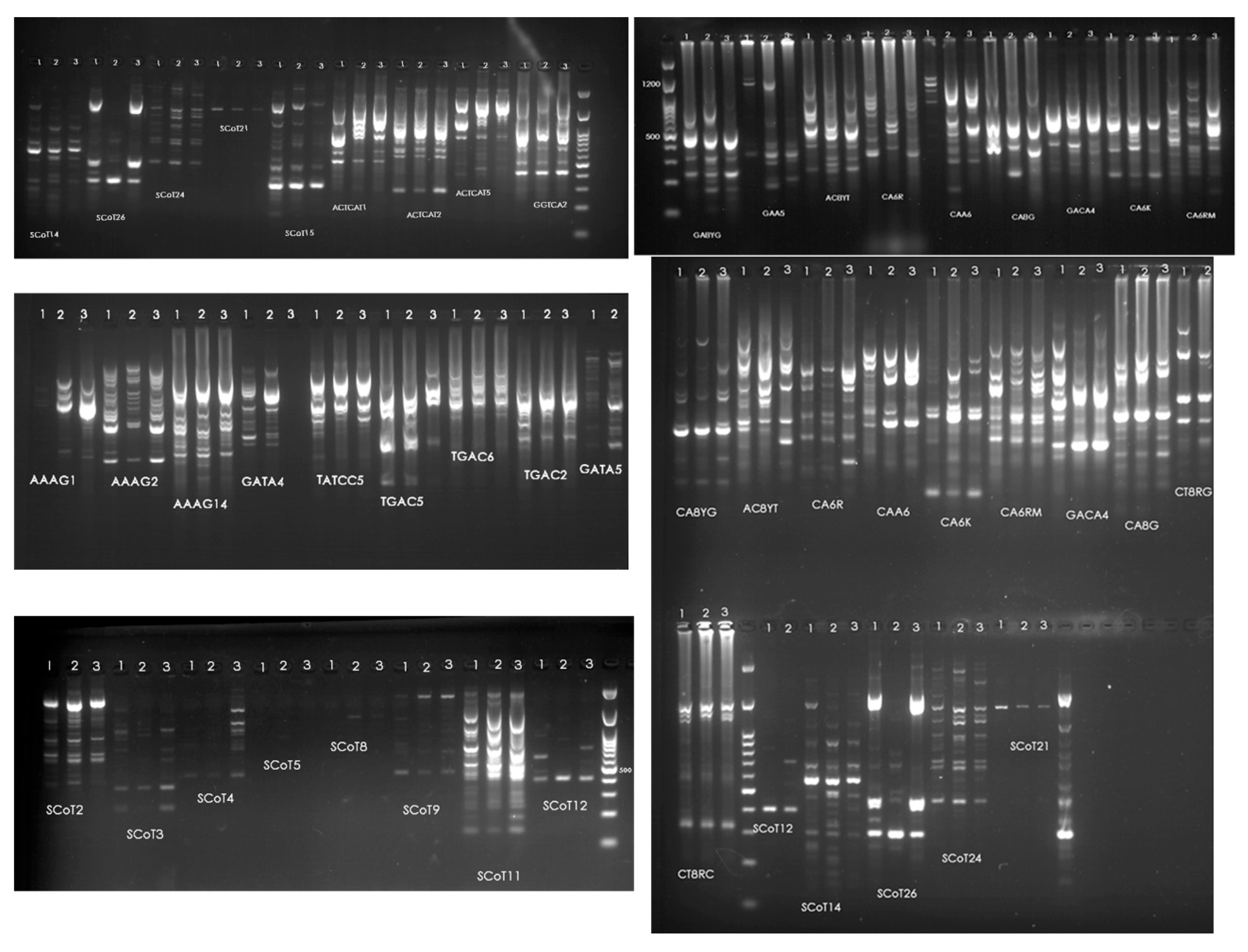

| Primers | Sequence | NB |

| ACTCAT1 | GCAGCTGCGTACTCATAA | 5b |

| ACTCAT2 | GCAGCTGCGTACTCATAT | 5b |

| AAAG1 | GCAGCTGCGTGTAAAGAA | 5c |

| AAAG2 | GCAGCTGCGTGTAAAGAT | 10c |

| AAAG14 | GCAGCTGCGTGTAAAGCT | 11c |

| GATAA4 | GCAGCTGCGTGGATAATA | 9c |

| GATAA5 | GCAGCTGCGTGGATAATT | 5c |

| ACGTG26 | GCAGTCAGACACGTGCAG | 11a |

| TATCC5 | GCAGCTGAGACTATCCTA | 5c |

| TGAC2 | GCAGCTGAGAGTTGACAT | 5c |

| TGAC5 | GCAGCTGAGAGTTGACTA | 6c |

| GGTCA2 | GCAGTCAGATCGGTCAAT | 6c |

| ACTCAT5 | 8b | |

| TGAC6 | 5c | |

| Total | 96 | |

| SCoT 2 | CAACAATGGCTACCACCC | 12e |

| SCoT 3 | CAACAATGGCTACCACCG | 7e |

| SCoT 4 | CAACAATGGCTACCACCT | 8e |

| SCoT 5 | CAACAATGGCTACCACGA | 0e |

| SCoT 8 | CAACAATGGCTACCACGT | 2e |

| SCoT 9 | CAACAATGGCTACCAGCA | 5e |

| SCoT 11 | AAGCAATGGCTACCACCA | 12e |

| SCoT 12 | ACGACATGGCGACCAACG | 4f |

| SCoT 14 | ACGACATGGCGACCACCG | 15f |

| SCoT 15 | ACGACATGGCGACCGCGA | 12f |

| SCoT 21 | ACGACATGGCGACCGCCA | 1e |

| SCoT 24 | CACCATGGCTACCACCAT | 10e |

| SCoT 26 | ACAATGGCTACCACCATC | 8f |

| Total | 96 | |

| AC8YT | ACACACACACACACACYT | 8d |

| CA6R | CACACACACACAR | 8d |

| CAA6 | CAACAACAACAACAACAA | 9d |

| CA6K | CACACACACACAK | 9d |

| CA6RM | CACACACACACARM | 11d |

| GACA4 | GACAGACAGACAGACA | 9d |

| GA8YG | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAYG | 9d |

| CT8RG | CTCTCTCTCTCTCTCTRG | 5d |

| CA8G | CACACACACACACACAG | 8d |

| CT8RC | CTCTCTCTCTCTCTCTRC | 7d |

| GATA4 | GATAGATAGATAGATA | 4d |

| GAA5 | GAAGAAGAAGAAGAA | 5d |

| CA8YG | CACACACACACACACAYG | 7d |

| Total | 97 |

| Primers | Band Freq. | N | Na | Ne | I | H |

| ACTCAT1 | 0.81 | 20 | 1.23 | 1.21 | 0.16 | 0.11 |

| CA6R | 0.67 | 20 | 1.80 | 1.60 | 0.50 | 0.34 |

| SCoT14 | 0.89 | 20 | 1.47 | 1.37 | 0.29 | 0.20 |

| SCoT24 | 0.51 | 20 | 1.86 | 1.43 | 0.39 | 0.26 |

| Mean | 1.61(0.07) | 1.41(0.05) | 0.34(0.04) | 0.23(0.03) | ||

| TB | PB% | |||||

| 59 | 63.93 | |||||

| ACTCAT1 | 0.83 | 20 | 1.46 | 1.26 | 0.23 | 0.15 |

| CA6R | 0.65 | 20 | 1.65 | 1.41 | 0.36 | 0.24 |

| SCoT14 | 0.80 | 20 | 1.41 | 1.34 | 0.28 | 0.19 |

| SCoT24 | 0.49 | 20 | 1.50 | 1.52 | 0.41 | 0.28 |

| Mean | 1.51(0.08) | 1.38(0.05) | 0.32(0.04) | 0.22(0.03) | ||

| TB | PB% | |||||

| 56 | 59.02 | |||||

| Primers | Band Freq. | N | Na | Ne | I | H |

| ACTCAT1 | 0.82 | 40 | 1.35 | 1.23 | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| CA6R | 0.66 | 40 | 1.74 | 1.50 | 0.43 | 0.29 |

| SCoT14 | 0.84 | 40 | 1.44 | 1.35 | 0.29 | 0.20 |

| SCoT24 | 0.50 | 40 | 1.68 | 1.48 | 0.40 | 0.27 |

| Total | 1.56(0.06) | 1.40(0.04) | 0.33(0.03) | 0.23(0.22) |

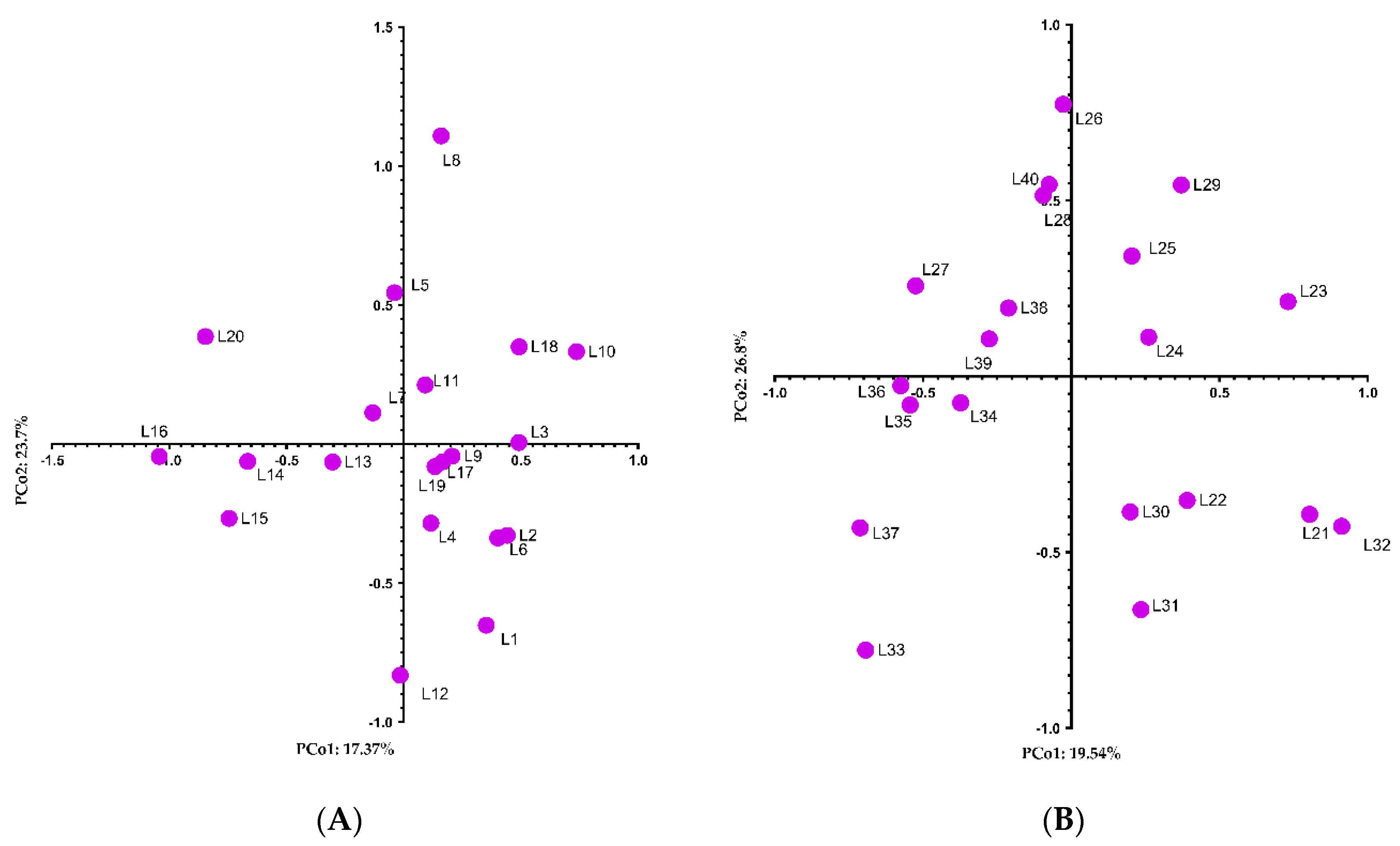

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. var | %Variation |

| Among fields | 1 | 88.875 | 88.875 | 4.156 | 42% |

| Within Fields | 38 | 218.550 | 5.751 | 5.751 | 58% |

| Total | 39 | 307.425 | 9.908 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).