Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. DNA Extraction and Molecular Analysis Using SSR Markers

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Genetic Diversity of Juglans Regia

3.2. Population Structure Analysis

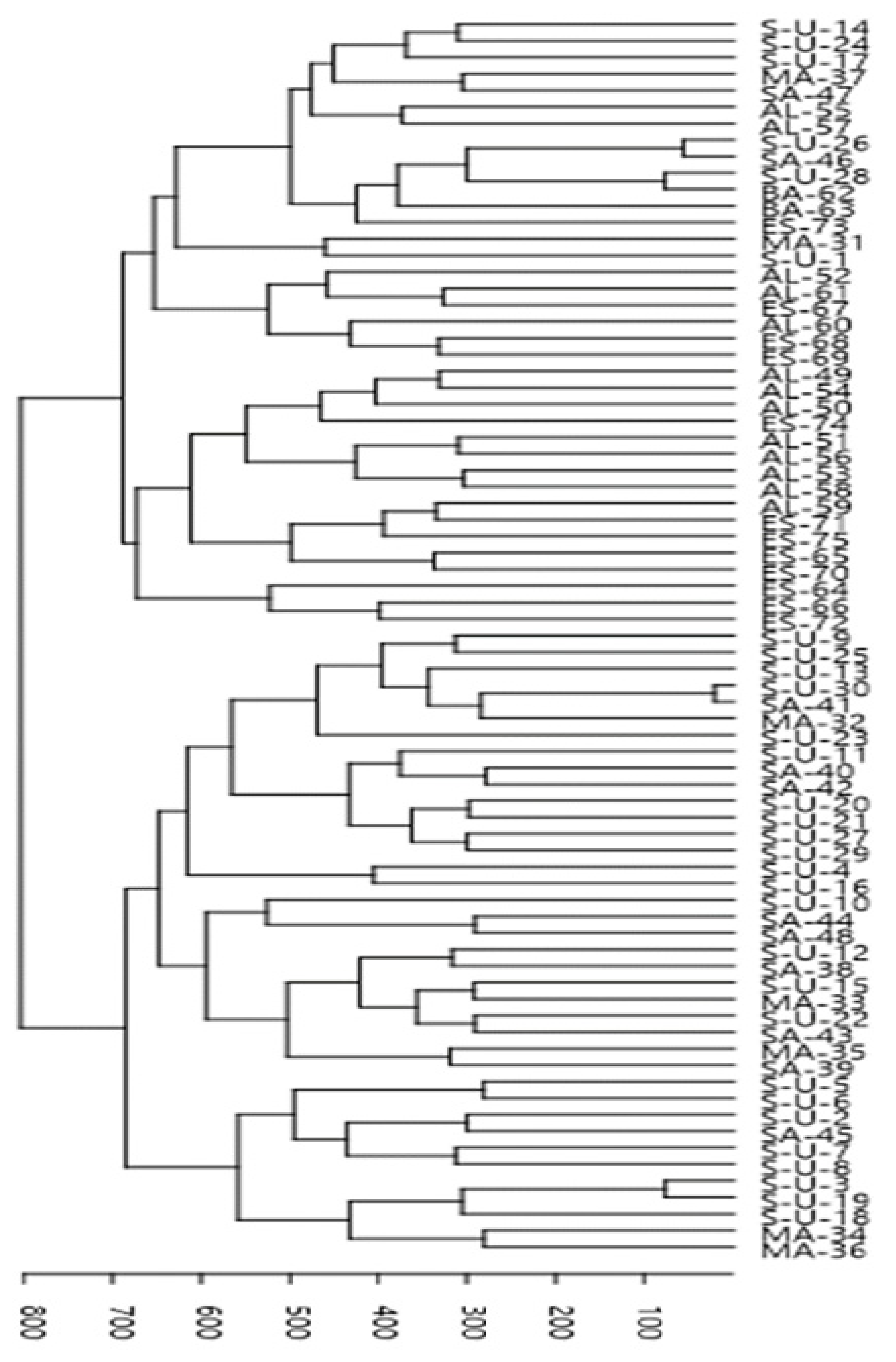

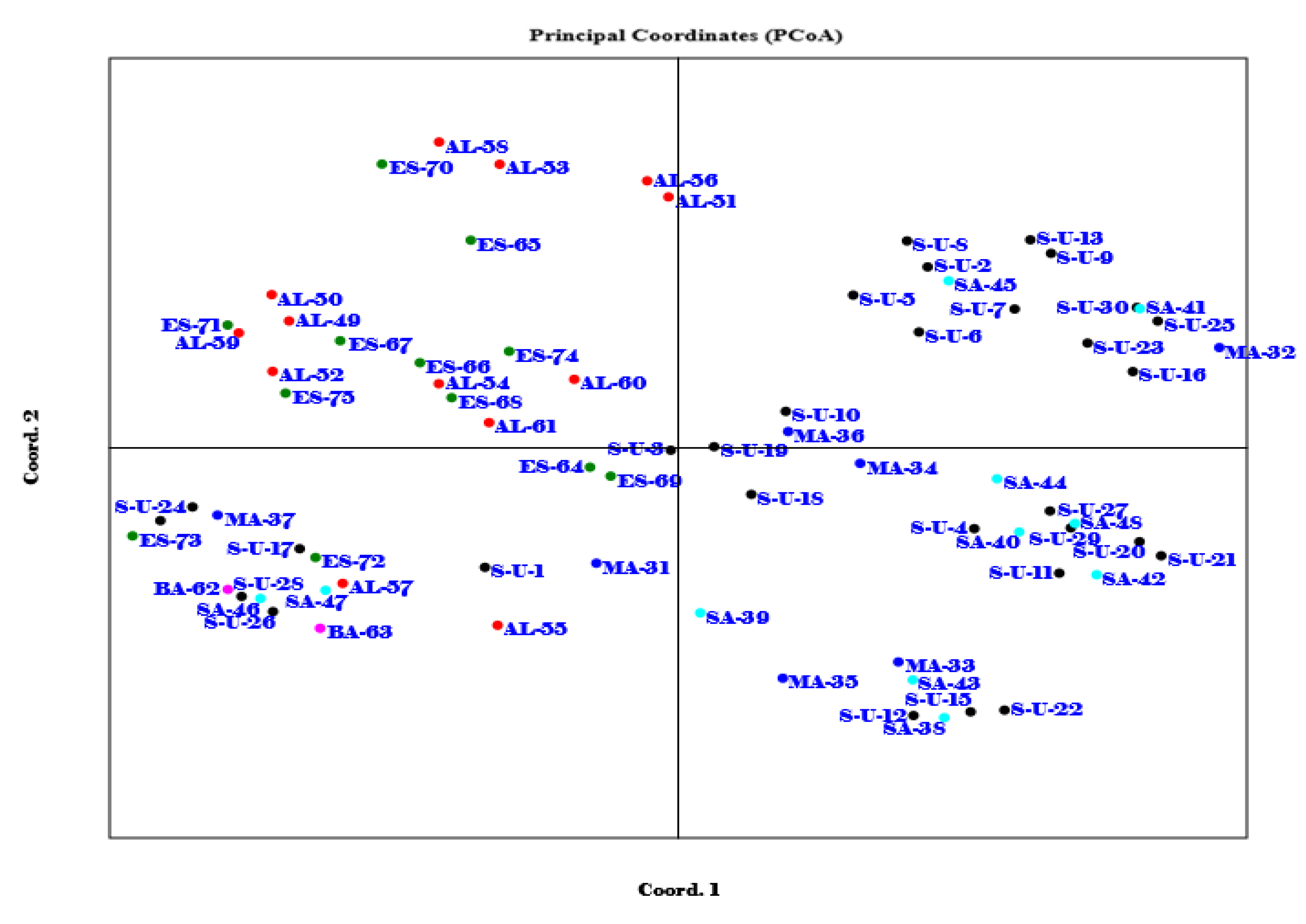

3.3. Cluster Analysis Using UPGMA and Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Declaration of competing interest

References

- Halvorsen, B. L.; Carlsen, M. H.; Phillips, K. M.; Bøhn, S. K.; Holte, K.; Jacobs, D. R.; Blomhoff, R. Content of redox-active compounds (ie, antioxidants) in foods consumed in the United States. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84 (1), 95–135. [CrossRef]

- Kornsteiner, M.; Wagner, K.-H.; Elmadfa, I. Tocopherols and total phenolics in 10 different nut types. Food Chem. 2006, 98 (2), 381–387. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.; Angove, M. J.; Tucci, J.; Dennis, C. Walnuts (Juglans regia) chemical composition and research in human health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56 (8), 1231–1241. [CrossRef]

- Ros, E.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M.; Sala-Vila, A. Beneficial effects of walnut consumption on human health: Role of micronutrients. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2018, 21 (6), 498–504. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guasch-Ferré, M.; Tobias, D. K.; Li, Y. Association of walnut consumption with total and cause-specific mortality and life expectancy in U.S. adults. Nutrients 2021, 13 (8), 2699. [CrossRef]

- Poggetti, L.; Ferfuia, C.; Chiabà, C.; Testolin, R.; Baldini, M. Kernel oil content and oil composition in walnut (Juglans regia L.) accessions from north-eastern Italy. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98 (3), 955–962. [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Ning, D.; Ma, T.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Comprehensive analysis of the components of walnut kernel (Juglans regia L.) in China. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 9302181. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhong, L.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Hou, X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, Y. Comprehensive comparative analysis of lipid profile in dried and fresh walnut kernels by UHPLC-Q-exactive orbitrap/MS. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132706. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, C.; Ciudad, C. J.; Noé, V.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M. Health benefits of walnut polyphenols: An exploration beyond their lipid profile. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57 (15), 3373–3383. [CrossRef]

- Gandev, S. Budding and grafting of the walnut (Juglans regia L.) and their effectiveness in Bulgaria (Review). Bulgar. J. Agri. Sci. 2007, 13 (5), 683–689.

- Martinez, M. L.; Labuckas, D. O.; Lamarque, A. L.; Maestri, D. M. Walnut (Juglans regia L.): genetic resources, chemistry, by-products. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90 (12), 1959–1967. [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, G.; Leslie, C. Walnut. In Fruit Breeding; Badenes, M., Byrne, D., Eds.; Handbook of Plant Breeding; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp 827–846.

- Pollegioni, P.; Woeste, K. E.; Chiocchini, F.; Del Lungo, S.; Olimpieri, I.; Tortolano, V.; et al. Ancient humans influenced the current spatial genetic structure of common walnut populations in Asia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10 (7), e0135980. [CrossRef]

- Vahdati, K. Traditions and folks for walnut growing around the Silk Road. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1032, 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Zohary, D.; Hopf, M.; Weiss, E. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; p 149.

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAO Statistics Division. 2018. Available online: http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/default.aspx#ancor (accessed on [date]).

- Vahdati, K.; Arab, M. M.; Sarikhani, S.; Sadat-Hosseini, M.; Leslie, C. A.; Brown, P. J. Advances in Persian walnut (Juglans regia L.) breeding strategies. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Nut and Beverage Crops; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp 401–472. [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture - Statistical Yearbook 2023; Rome, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Akça, Y.; Yusupov, B. Y.; Erdenov, M.; Vahdati, K. Exploring of walnut genetic resources in Kazakhstan and evaluation of promising selections. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2020, 7 (1), 93–102. [CrossRef]

- Kairova, G.; Taskuzhina, A.; Yanin, K.; Ismagulova, E.; Oleichenko, S.; Sarshayeva, M.; Sapakhova, Z.; Gritsenko, D. First evaluation of genetic diversity and population structure of wild and cultivated Juglans regia in Kazakhstan. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2025, 72 (4), 1755–1771. [CrossRef]

- Oleichenko, S. N.; Yegizbayeva, T. K.; Apushev, A. K.; Nusipzhanov, N. S. Assessment of promising local walnut forms for the South and South-East of Kazakhstan. Rep. Natl. Acad. Sci. Repub. Kazakhstan 2020, 333, 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Bakhytuly, K.; Kokhmetova, A. M.; Umirzakova, A. T.; Kuliev, A. S.; Kumbarbayeva, M. T.; Keishilov, Z. S. Monitoring of the distribution of Juglans regia L. in the southern and south-eastern regions of Kazakhstan and morphological study of walnut fruits. Izd. Natigeler 2024, 2, 238–248. [CrossRef]

- Terletskaya, N. V.; Shadenova, E. A.; Litvinenko, Y. A.; Ashimuly, K.; Erbay, M.; Mamirova, A.; Nazarova, I.; Meduntseva, N. D.; Kudrina, N. O.; Korbozova, N. K.; et al. Influence of cold stress on physiological and phytochemical characteristics and secondary metabolite accumulation in microclones of Juglans regia L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25 (9), 4991. [CrossRef]

- Kushnarenko, S. V.; Rymkhanova, N. K.; Aralbayeva, M. M.; Romadanova, N. V. In vitro cold acclimation is required for successful cryopreservation of Juglans regia L. shoot tips. CryoLetters 2023, 44 (3), 240–248. [CrossRef]

- Kushnarenko, S.; Aralbayeva, M.; Rymkhanova, N.; et al. Initiation pretreatment with Plant Preservative Mixture™ increases the percentage of aseptic walnut shoots. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. - Plant 2022, 58 (6), 964–971. [CrossRef]

- Kairov, G.; Ismagulova, E.; Oleichenko, S.; Suleimanova, G.; Basim, H.; Sarshabayeva, M. Resistance of walnut varieties to bacteriosis caused by Pantoea agglomerans in the southern fruit-growing zone of Kazakhstan. Izdenister Natigeler 2024, 2, 238–248. [CrossRef]

- Çarpar, H.; Sertkaya, G. First report of Crepis phyllody disease associated with phytoplasma in Crepis foetida in a walnut orchard in Turkey. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2023, 130 (3), 177–180. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Zhao, G.-F.; Zhang, S.-X.; Zhou, H.-J.; Hu, Y.-H.; Woeste, K. E. RAPD derived markers for separating Manchurian walnut (Juglans mandshurica) and Japanese walnut (J. ailantifolia) from close congeners. J. Syst. Evol. 2014, 52 (2), 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zhang, J.; Pei, D. Genetic analysis of walnut cultivars in China using fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2011, 136 (6), 422–428. [CrossRef]

- Kafkas, S.; Ozkan, H.; Sutyemez, M. DNA polymorphism and assessment of genetic relationships in walnut genotypes based on AFLP and SAMPL markers. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2005, 130 (4), 585–590. [CrossRef]

- Itoo, H.; Shah, R. A.; Qurat, S.; Jeelani, A.; Khursheed, S.; Bhat, Z. A.; Mir, M. A.; Rather, G. H.; Zargar, S. M.; Shah, M. D.; et al. Genome-wide characterization and development of SSR markers for genetic diversity analysis in Northwestern Himalayas walnut (Juglans regia L.). 3 Biotech 2023, 13 (3), 136. [CrossRef]

- Arab, M. M.; Brown, P. J.; Abdollahi-Arpanahi, R.; Sohrabi, S. S.; Askari, H.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Mokhtassi-Bidgoli, A.; Mesgaran, M. B.; Leslie, C. A.; Marrano, A.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis and pathway enrichment provide insights into the genetic basis of photosynthetic responses to drought stress in Persian walnut. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac124. [CrossRef]

- Grover, A.; Aishwarya, V.; Sharma, P. C. Biased distribution of microsatellite motifs in the rice genome. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2007, 277 (5), 469–480. [CrossRef]

- Taheri, S.; Lee Abdullah, T.; Yusop, M. R.; Hanafi, M. M.; Sahebi, M.; Azizi, P.; Shamshiri, R. R. Mining and development of novel SSR markers using next generation sequencing (NGS) data in plants. Molecules 2018, 23, 399. [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, N.; Song, L.; Yan, B.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Fang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. Fingerprinting 146 Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima Blume) accessions and selecting a core collection using SSR markers. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1277–1286. [CrossRef]

- Kalia, R. K.; Rai, M. K.; Kalia, S.; Singh, R.; Dhawan, A. K. Microsatellite markers: An overview of the recent progress in plants. Euphytica 2011, 177, 309–334. [CrossRef]

- Ali Khan, M.; Shahid Ul, I.; Mohammad, F. Extraction of natural dye from walnut bark and its dyeing properties on wool yarn. J. Nat. Fibers 2016, 13, 458–469. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Barreneche, T.; Donkpegan, A.; Lheureux, F.; Dirlewanger, E. Comparison of structure analyses and core collections for the management of walnut genetic resources. Tree Genet. Genomes 2020, 16, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Marrano, A.; Donkpegan, A.; Brown, P. J.; Leslie, C. A.; Neale, D. B.; Lheureux, F.; Dirlewanger, E. Association and linkage mapping to unravel genetic architecture of phenology-related traits and lateral bearing in Persian walnut (Juglans regia L.). 2019.

- Shah, U. N.; Mir, J. I.; Ahmed, N.; Fazili, K. M. Assessment of germplasm diversity and genetic relationships among walnut (Juglans regia L.) genotypes through microsatellite markers. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2018, 17, 339–350. [CrossRef]

- Shah, R. A.; Baksi, P.; Jasrotia, A.; Bhat, D. J. I.; Gupta, R.; Bakshi, M. Genetic diversity of walnut (Juglans regia L.) seedlings through SSR markers in north-western Himalayan region of Jammu. Bangladesh J. Bot. 2020, 49, 1003–1012. [CrossRef]

- Pollegioni, P.; Woeste, K.; Chiocchini, F.; Del Lungo, S.; Ciolfi, M.; Olimpieri, I.; Tortolano, V.; Clark, J.; Hemery, G. E.; Mapelli, S.; et al. Rethinking the history of common walnut (Juglans regia L.) in Europe: its origins and human interactions. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172541. [CrossRef]

- Doğan, Y.; Kafkas, S.; Sütyemez, M.; Akça, Y.; Türemiş, N. Assessment and characterization of genetic relationships of walnut (Juglans regia L.) genotypes by three types of molecular markers. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 168, 81–87. [CrossRef]

- Nickravesh, M. H.; Vahdati, K.; Amini, F.; Di Pierro, E. A.; Amiri, R.; Woeste, K.; Arab, M. M. Reliable propagation of Persian walnut varieties using SSR marker-based true-to-type validation. HortScience 2023, 58, 64–66. [CrossRef]

- Wambulwa, M. C.; Fan, P. Z.; Milne, R.; Wu, Z. Y.; Luo, Y. H.; Wang, Y. H.; Wang, H.; Gao, L. M.; Ye, L. J.; Jin, Y. C.; et al. Genetic analysis of walnut cultivars from Southwest China: Implications for germplasm improvement. Plant Divers. 2022, 44, 530–541. [CrossRef]

- Shamlu, F. Genetic diversity of walnut (Juglans regia L.) populations in Iran based on SSR markers. J. Nuts 2018, 9, 1–12.

- Rogers, S. O.; Bendich, A. J. Extraction of DNA from milligram amounts of fresh, herbarium and mummified plant tissues. Plant Mol. Biol. 1985, 5, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Woeste, K.; Burns, R.; Rhodes, O.; Michler, C. Thirty polymorphic nuclear microsatellite loci from black walnut. J. Hered. 2002, 93, 58–60. [CrossRef]

- Dangl, G. S.; Woeste, K.; Aradhya, M. K.; Koehmstedt, A.; Simon, C.; Potter, D.; Leslie, C. A.; McGranahan, G. Characterization of 14 microsatellite markers for genetic analysis and cultivar identification of walnut. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2005, 130, 348–354. [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P. E. GenAlEx 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2006, 6, 288–295. [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P. E. GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—An update. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D. A. T.; Ryan, P. D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9.

- Pritchard, J. K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [CrossRef]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Fatahi, R.; Zamani, Z. Analysis of genetic diversity among some Persian walnut genotypes (Juglans regia L.) using SSR markers. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 130, 146–151. [CrossRef]

- Orhan, E.; Eyduran, S. P.; Poljuha, D.; Akin, M.; Weber, T.; Ercisli, S. Genetic diversity detection of seed-propagated walnut (Juglans regia L.) germplasm from Eastern Anatolia using SSR markers. Horticulturae 2020, 32, 67–76. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Barreneche, T.; Lheureux, F.; Dirlewanger, E. Analysis of genetic diversity and structure in a worldwide walnut (Juglans regia L.) germplasm using SSR markers. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208021. [CrossRef]

- Plugatar, Y. V.; Suprun, I. I.; Khokhlov, S. Yu.; Stepanov, I. V.; Al-Nakib, E. A. Comprehensive Agrobiological Assessment and Analysis of Genetic Relationships of Promising Walnut Varieties of the Nikitsky Botanical Gardens. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2023, 27, 454–462. [CrossRef]

- Aradhya, M. K.; Woeste, K.; Velasco, D. Genetic Diversity, Structure and Differentiation in Cultivated Walnut (Juglans regia L.). Acta Hortic. 2010, 861, 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Manthos, I.; Sotiropoulos, T.; Karapetsi, L.; Ganopoulos, I.; Pratsinakis, E. D.; Maloupa, E.; Madesis, P. Molecular Characterization of Local Walnut (Juglans regia) Genotypes in the North-East Parnon Mountain Region of Greece. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17230. [CrossRef]

- Suprun, I.; Stepanov, I.; Anatov, D. Analysis of Genetic Diversity and Relationships of Local Walnut Populations in the Western Caspian Region of the North Caucasus. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 65. [CrossRef]

- Samlu, F.; Rezaei, M.; Lawson, S.; Ebrahimi, A.; Biabani, A.; Khan-Ahmadi, A. Genetic Diversity of Superior Persian Walnut Genotypes in Azadshahr, Iran. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2018, 24, 939–949. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Barreneche, T.; Lheureux, F.; Dirlewanger, E. SSR Genetic Diversity Assessment of the INRAE’s Walnut (Juglans spp.) Germplasm Collection. Acta Hortic. 2020, 1297, 387–394. [CrossRef]

| No. | Geographic Region, Location | Population/Local Walnut Sample | Latitude | Longitude | Altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-01 | N 42 39 995 | E 070 15 080 | 820 |

| 2 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-02 | N 42 39 995 | E 070 15 095 | 817 |

| 3 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-03 | N 42 39 992 | E 070 15 098 | 815 |

| 4 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-04 | N 42 39 991 | E 070 15 119 | 811 |

| 5 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-05 | N 42 39 988 | E 070 15 119 | 808 |

| 6 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-06 | N 42 39 982 | E 070 15 117 | 804 |

| 7 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-07 | N 42 39 981 | E 070 15 113 | 811 |

| 8 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-08 | N 42 39 980 | E 070 15 115 | 806 |

| 9 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-09 | N 42 39 975 | E 070 15 113 | 804 |

| 10 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-10 | N 42 39 986 | E 070 15 130 | 810 |

| 11 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-11 | N 42 39 995 | E 070 15 139 | 814 |

| 12 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-12 | N 42 40 001 | E 070 15 135 | 811 |

| 13 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-13 | N 42 40 010 | E 070 15 136 | 805 |

| 14 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-14 | N 42 399 95 | E 070 15 112 | 799 |

| 15 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-15 | N 42 39 955 | E 070 15 112 | 804 |

| 16 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-16 | N 42 39 985 | E 070 15 153 | 810 |

| 17 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-17 | N 42 39 994 | E 070 15 156 | 808 |

| 18 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-18 | N 42 39 999 | E 070 15 161 | 811 |

| 19 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-19 | N 42 40 020 | E 070 15 154 | 817 |

| 20 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-20 | N 42 40 021 | E 070 15 157 | 816 |

| 21 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-21 | N 42 40 017 | E 070 15 157 | 816 |

| 22 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-22 | N 42 40 039 | E 070 15 135 | 819 |

| 23 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-23 | N 42 40 041 | E 070 15 140 | 820 |

| 24 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-24 | N 42 40 051 | E 070 15 069 | 831 |

| 25 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-25 | N 42 40 049 | E 070 15 067 | 829 |

| 26 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-26 | N 42 40 041 | E 070 15 073 | 828 |

| 27 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-27 | N 42 39 994 | E 070 15 082 | 821 |

| 28 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-28 | N 42 39 987 | E 070 15 088 | 816 |

| 29 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-29 | N 42 39 986 | E 070 15 097 | 815 |

| 30 | Turkestan region, S-U | S-U-30 | N 42 39 984 | E 070 15 068 | 845 |

| 31 | Turkestan region, MA | MA -01 | N 42 25 665 | E 070 03 024 | 669 |

| 32 | Turkestan region, MA | MA -02 | N 42 25 670 | E 070 03 025 | 665 |

| 33 | Turkestan region, MA | MA-03 | N 42 25 672 | E 070 03 030 | 664 |

| 34 | Turkestan region, MA | MA-04 | N 42 25 675 | E 070 03 028 | 664 |

| 35 | Turkestan region, MA | MA-05 | N 42 25 672 | E 070 02 669 | 660 |

| 36 | Turkestan region, MA | MA-06 | N 42 25 671 | E 070 02 682 | 662 |

| 37 | Turkestan region, MA | MA-07 | N 42 25 670 | E 070 02 642 | 664 |

| 38 | Turkestan region, SA | SA-01 | N 41 27 773 | E 069 25 611 | 579 |

| 39 | Turkestan region, SA | SA-02 | N 41 27 794 | E 069 25 634 | 577 |

| 40 | Turkestan region, SA | SA-03 | N 41 27 796 | E 069 25 641 | 580 |

| 41 | Turkestan region, SA | SA-04 | N 41 27 802 | E 069 25 649 | 578 |

| 42 | Turkestan region, SA | SA-05 | N 41 27 813 | E 069 25 671 | 578 |

| 43 | Turkestan region, SA | SA-06 | N 41 27 860 | E 069 25 729 | 578 |

| 44 | Turkestan region, SA | SA-07 | N 41 27 874 | E 069 25 744 | 576 |

| 45 | Turkestan region, SA | SA-08 | N 41 27 958 | E 069 25 637 | 575 |

| 46 | Turkestan region, SA | SA-09 | N 41 27 955 | E 069 25 636 | 576 |

| 47 | Turkestan region, SA | SA-10 | N 41 27 692 | E 069 25 686 | 577 |

| 48 | Turkestan region, SA | SA-11 | N 41 27 693 | E 069 25 684 | 574 |

| 49 | Almaty region, AL | AL-01 | N 43 179 141 | E 076 867 784 | 898 |

| 50 | Almaty region, AL | AL-02 | N 43 197 52 | E 076 84 600 | 895 |

| 51 | Almaty region, AL | AL-03 | N 43 19 733 | E 076 84 664 | 896 |

| 52 | Almaty region, AL | AL-04 | N 43 19 756 | E 076 84 601 | 895 |

| 53 | Almaty region, AL | AL-05 | N 43 197 55 | E 076 84 602 | 894 |

| 54 | Almaty region, AL | AL-06 | N 43 20 214 | E 076 84 941 | 896 |

| 55 | Almaty region, AL | AL-07 | N 43 13 322 | E 076 55 063 | 880 |

| 56 | Almaty region, AL | AL-08 | N 43 13 331 | E 076 55 262 | 883 |

| 57 | Almaty region, AL | AL-09 | N 43 13 013 | E 076 54 955 | 896 |

| 58 | Almaty region, AL | AL-10 | N 43 13 011 | E 076 54 954 | 895 |

| 59 | Almaty region, AL | AL-11 | N 43 13 010 | E 076 54 950 | 892 |

| 60 | Almaty region, AL | AL-12 | N 43 13 012 | E 076 54 951 | 898 |

| 61 | Almaty region, AL | AL-13 | N 43 13 013 | E 076 54 956 | 891 |

| 62 | Almaty region, BA | BA-01 | N 43 51 353 | Е 077 69 19 | 720 |

| 63 | Almaty region, BA | BA-02 | N 43 51 329 | E 077 69 359 | 725 |

| 64 | Almaty region, ES | ES-01 | N 43 18 085 | Е 077 29 997 | 1286 |

| 65 | Almaty region, ES | ES-02 | N 43 18 086 | Е 077 29 993 | 1284 |

| 66 | Almaty region, ES | ES-03 | N 43 18 081 | Е 077 30 000 | 1287 |

| 67 | Almaty region, ES | ES-04 | N 43 341 342 | Е 077 471 442 | 1285 |

| 68 | Almaty region, ES | ES-05 | N 43 341 11 | Е 077 481 579 | 1286 |

| 69 | Almaty region, ES | ES-06 | N 43 341 054 | Е 077 480 984 | 1284 |

| 70 | Almaty region, ES | ES-07 | N 43 341 010 | Е 077 480 994 | 1286 |

| 71 | Almaty region, ES | ES-08 | N 43 18 164 | Е 077 29 976 | 1283 |

| 72 | Almaty region, ES | ES-09 | N 43 18 162 | Е 077 29 973 | 1282 |

| 73 | Almaty region, ES | ES-10 | N 43 18 112 | Е 077 30 004 | 1291 |

| 74 | Almaty region, ES | ES-11 | N 43 18 107 | Е 077 29 990 | 1286 |

| 75 | Almaty region, ES | ES-12 | N 43 18 104 | Е 077 29 991 | 1284 |

| Primer | Forward Primer (5'-3') |

Reverse Primer (5'-3') |

Annealing Temperature (°C) | Product Size Range (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGA001 | ATTGGAAGGGAAGGGAAATG | CGCGCACATACGTAAATCAC | 56 | 180–210 |

| WGA027 | AACCCTACAACGCCTTGATG | TGCTCAGGCTCCACTTCC | 57 | 225-260 |

| WGA042 | GTGGGTTCGACCGTGAAC | AACTTTGCACCACATCCACA | 55 | 210–260 |

| WGA118 | TGTGCTCTGATCTGCCTCC | GGGTGGGTGAAAAGTAGCAA | 60 | 186–200 |

| WGA009 | CATCAAAGCAAGCAATGGG | CCATTGCTCTGTGATTGGG | 56 | 231–245 |

| WGA202 | CCCATCTACCGTTGCACTTT | GCTGGTGGTTCTATCATGGG | 62 | 259–295 |

| WGA276 | CTCACTTTCTCGGCTCTTCC | GGTCTTATGTGGGCAGTCGT | 60 | 168–194 |

| WGA376 | GCCCTCAAAGTGATGAACGT | TCATCCATATTTACCCCTTTCG | 56 | 230–265 |

| Locus | Na | Ne | I | Ho | He |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGA001 | 6,000 | 3,882 | 1,507 | 0,612 | 0,742 |

| WGA027 | 2,000 | 1,930 | 0,675 | 0,238 | 0,482 |

| WGA042 | 2,000 | 1,943 | 0,679 | 0,341 | 0,485 |

| WGA118 | 3,000 | 2,665 | 1,039 | 0,593 | 0,625 |

| WGA009 | 6,000 | 4,592 | 1,650 | 0,625 | 0,782 |

| WGA202 | 9,000 | 5,619 | 1,916 | 0,571 | 0,822 |

| WGA276 | 10,000 | 6,664 | 2,095 | 0,717 | 0,850 |

| WGA376 | 9,000 | 6,458 | 1,995 | 0,676 | 0,845 |

| Mean | 5,875 | 4,219 | 1,444 | 0,547 | 0,704 |

| Pop | Location | Na | Ne | I | Ho | He |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pop1 | S-U | 4,625 | 3,658 | 1,307 | 0,697 | 0,683 |

| pop2 | MA | 2,375 | 1,851 | 0,670 | 0,367 | 0,388 |

| pop3 | SA | 2,500 | 1,877 | 0,642 | 0,290 | 0,363 |

| pop4 | AL | 3,500 | 2,612 | 1,000 | 0,437 | 0,555 |

| pop5 | BA | 1,125 | 1,075 | 0,157 | 0,063 | 0,109 |

| pop6 | ES | 3,875 | 3,420 | 1,187 | 0,634 | 0,639 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).