Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

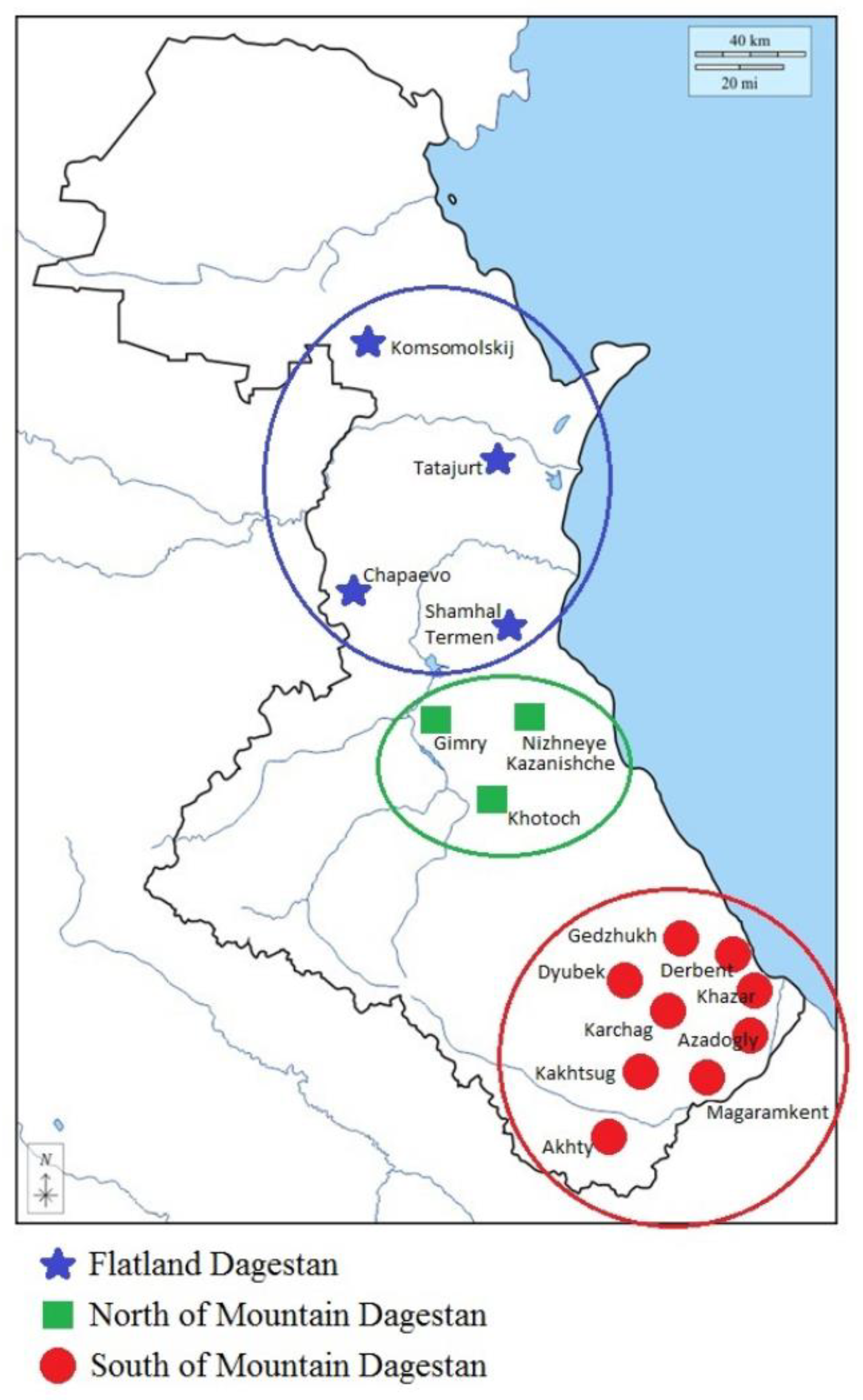

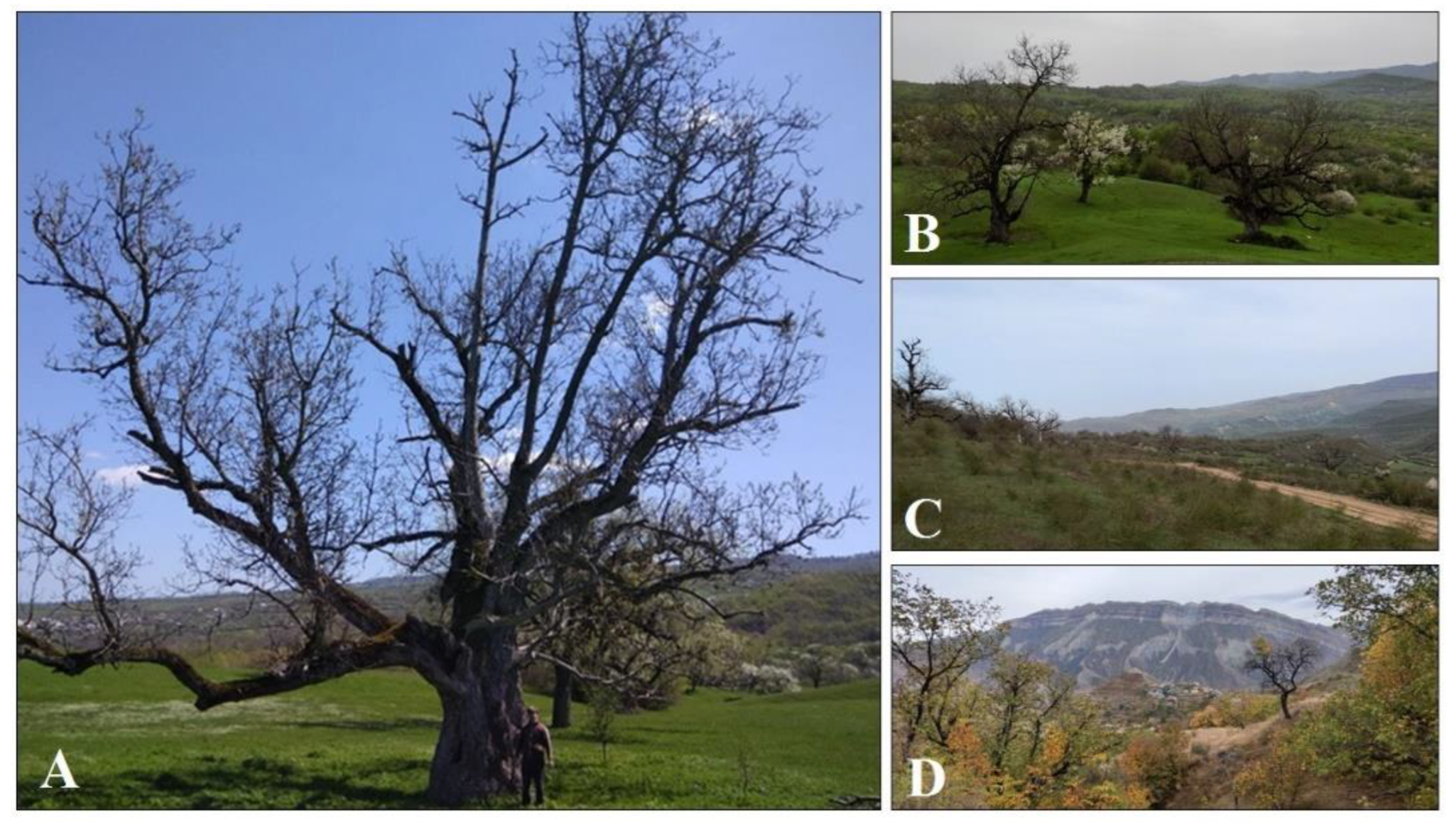

2.1. Plant material

2.2. DNA extraction. PCR setup. PCR product analysis

2.3. Analysis of genetic diversity

3. Results

3.1. Genetic variability of studied set of walnut genotypes

3.2. Evaluation of AMOVA parameters between regional groups of Juglans regia

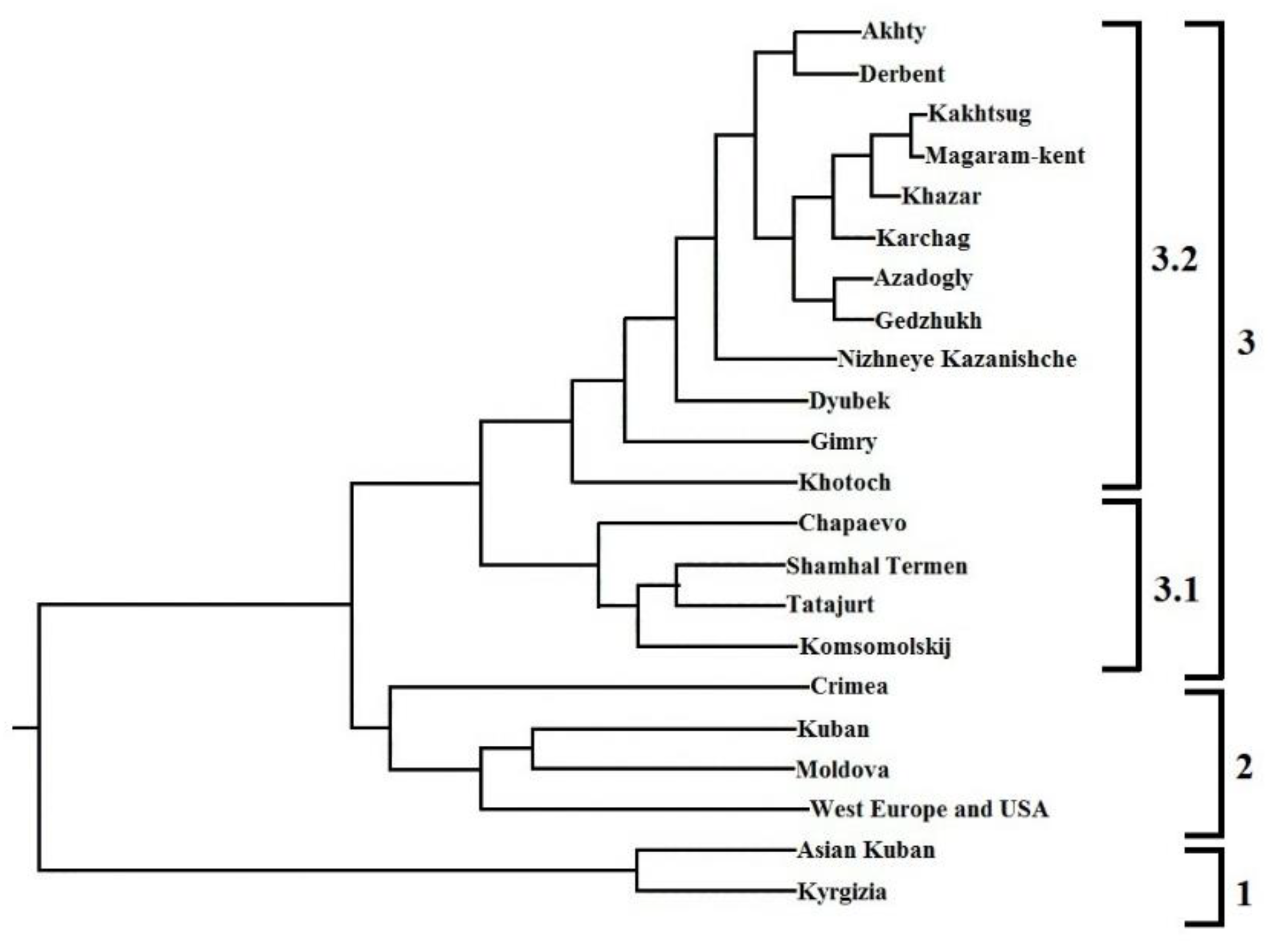

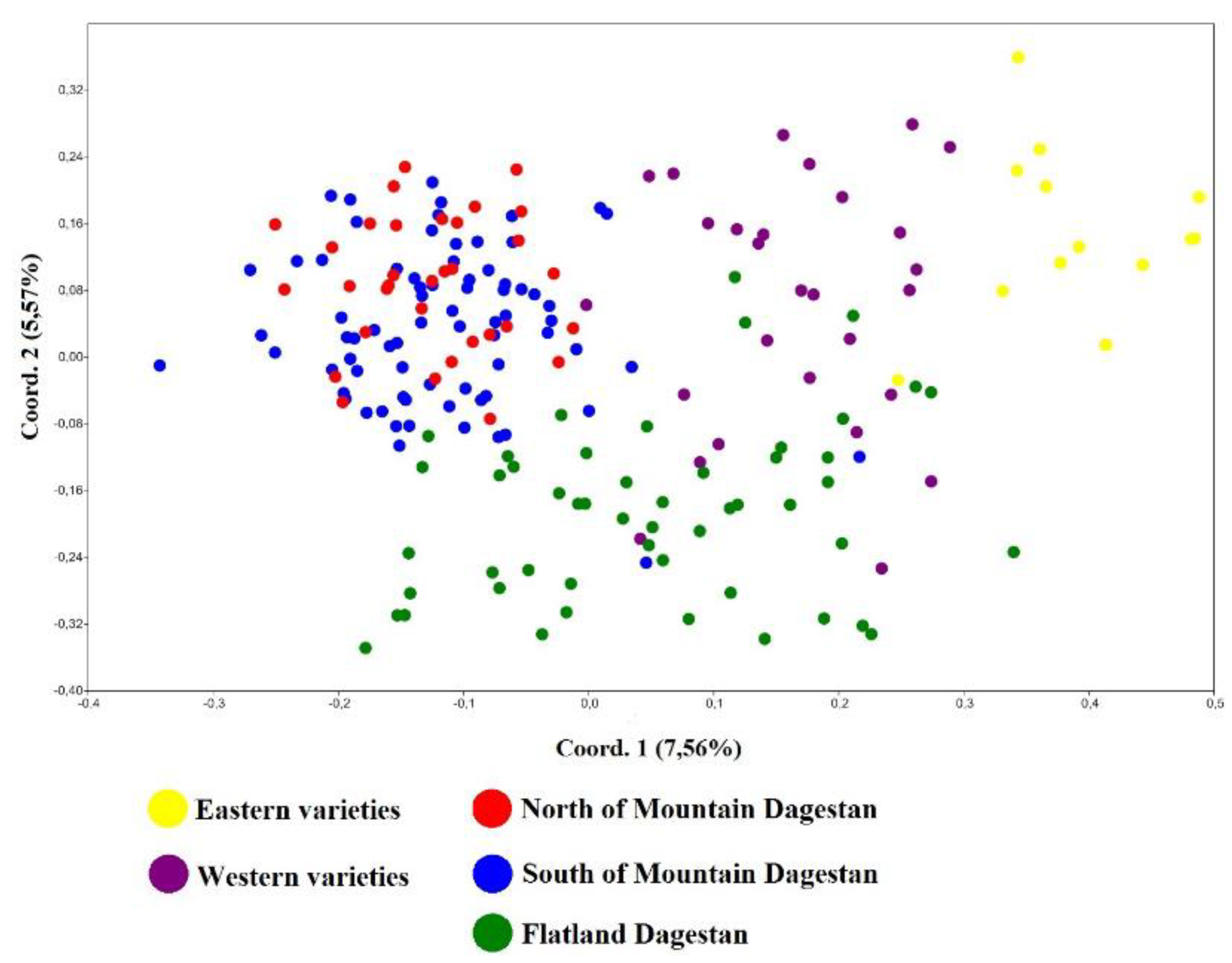

3.3. Estimated genetic distances between groups by origin of Juglans regia with used UPGMA and PCoA methods

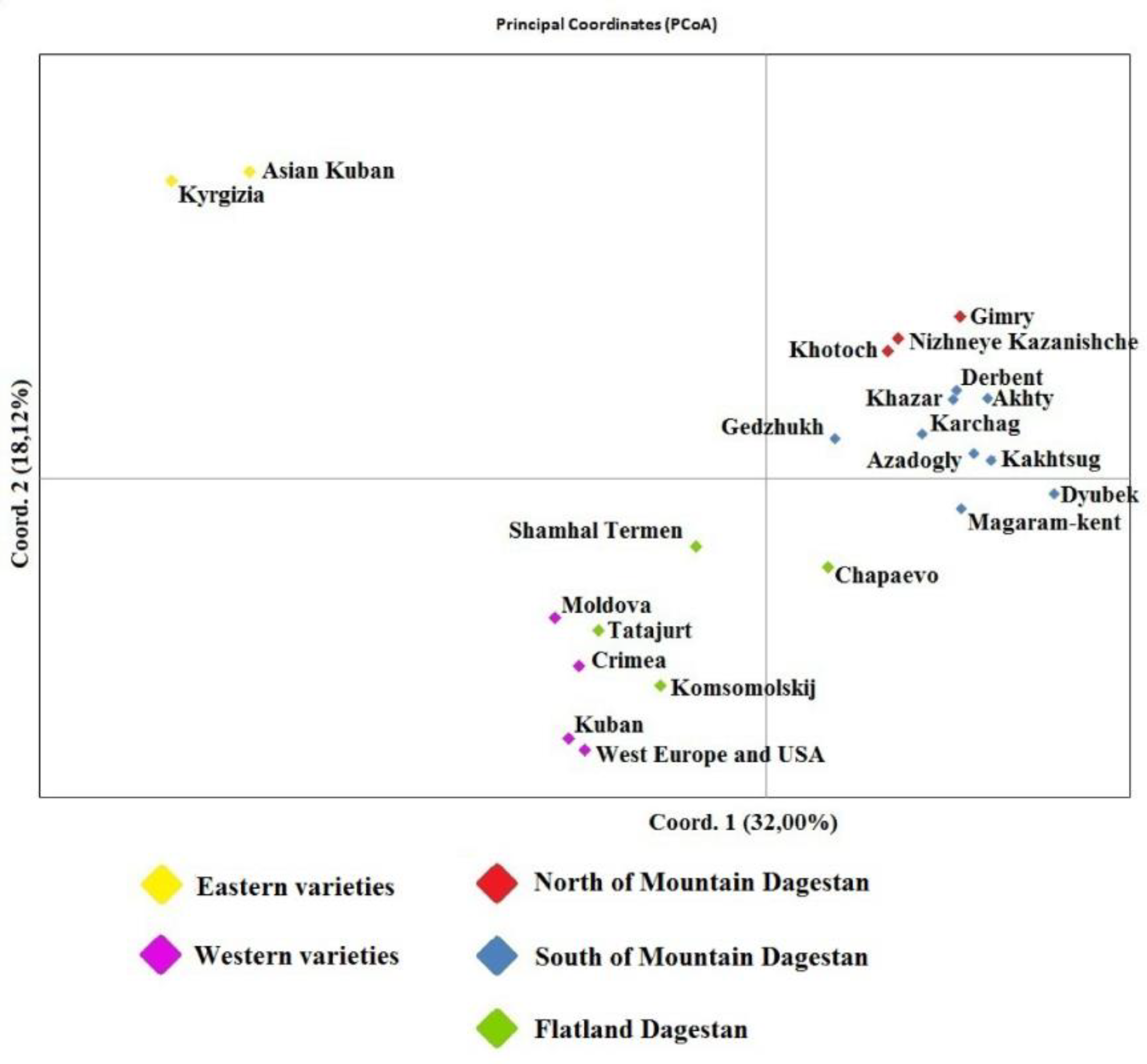

3.4. Estimated genetic distances between individual samples Juglans regia on the PCoA graph

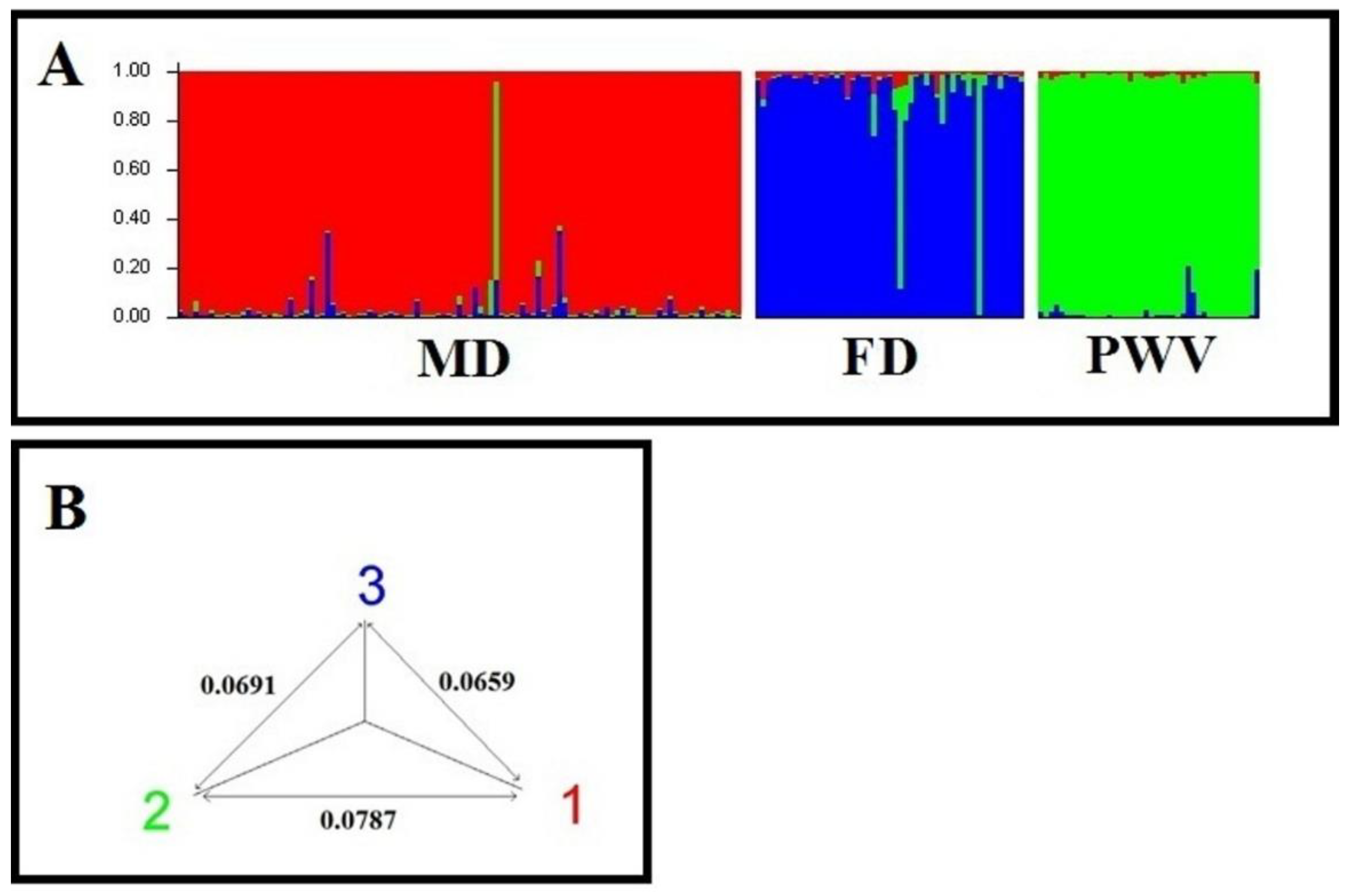

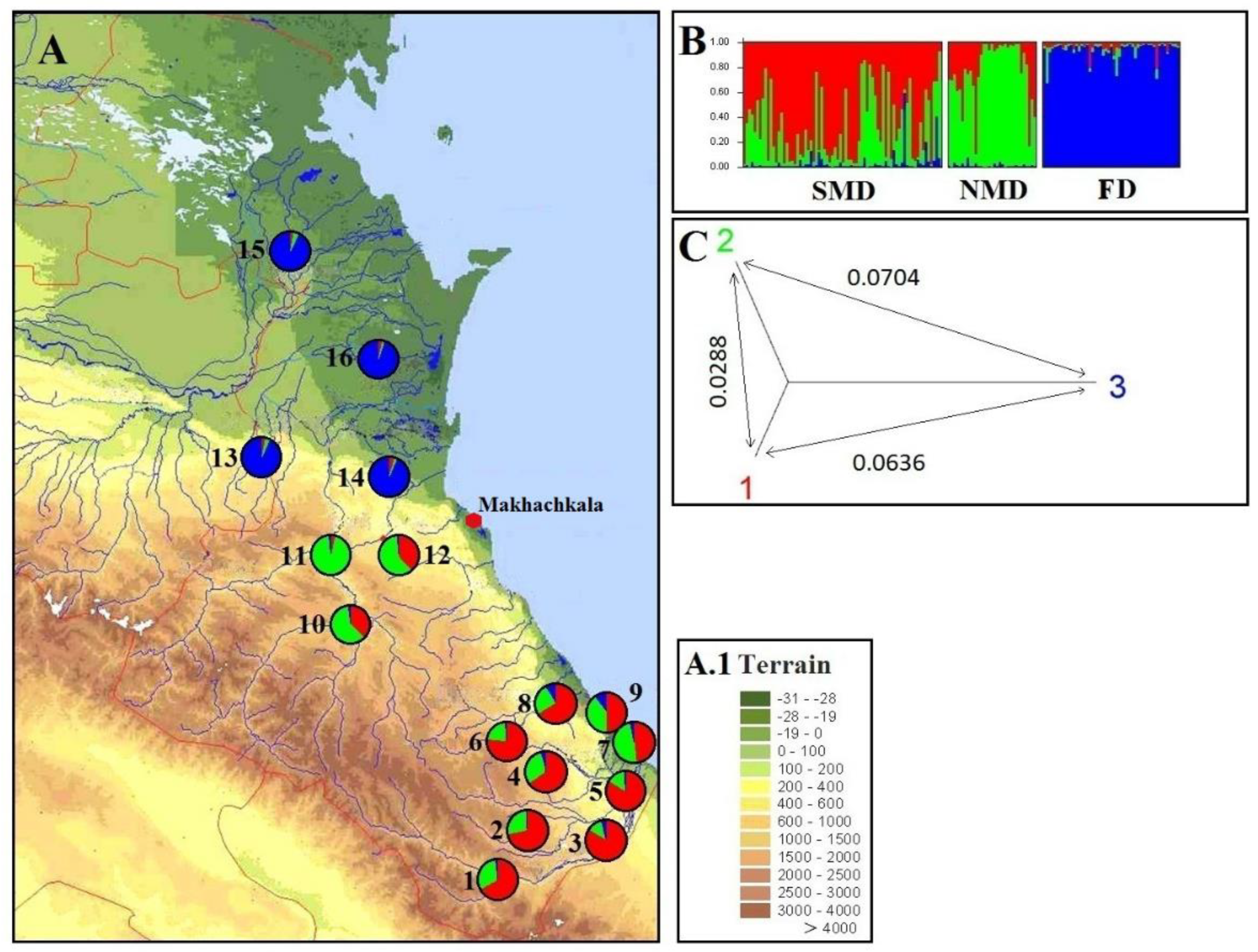

3.4. Genetic analysis of walnut samples in the program STRUCTURE

4. Discussion

4.1. Polymorphism of SSR loci

4.2. Analysis of the genetic structure of walnut populations from Dagestan

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vahdati, K.; Arab, M.M.; Sarikhani, S.; Sadat-Hosseini, M.; Leslie, C. A.; Brown, P.J. Advances in Persian walnut (Juglans regia L.) breeding strategies. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Nut Beverage Crops 2019, 4, 401-472. [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, G.; Leslie, C. Walnut, in: Badenes, M., Byrne, D. (Eds.), Fruit Breeding. Handbook of Plant Breeding. Springer, Boston, MA, 2012; pp 827-846. [CrossRef]

- Rébufa, C.; Artaud J.; Dréau, Y.L. Walnut (Juglans regia L.) oil chemical composition depending on variety, locality, extraction process and storage conditions: A comprehensive review. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2022, 110, 104534. [CrossRef]

- Rabrenović, B.; Natić, M.; Zagorac, D.D.; Meland, M.; Akšić, M. F. Bioactive Phytochemicals from Walnut (Juglans spp.) Oil Processing By-products. In: Ramadan Hassanien, M.F. (eds) Bioactive Phytochemicals from Vegetable Oil and Oilseed Processing By-products. Reference Series in Phytochemistry. Springer, Cham. 2023, 535-557. [CrossRef]

- Najafian Ashrafi, M.; Shaabani Asrami, H.; Vosoughi Rudgar, Z.; Ghorbanian Far, M.; Heidari, A.; Rastbod, E.; Jafarzadeh, H.; Salehi, M.; Bari, E.; Ribera, J. Comparison of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Beech and Walnut Wood from Iran and Georgian Beech. Forests. 2021, 12, 801. [CrossRef]

- Pollegioni, P.; Woeste, K.; Chiocchini, F.; Olimpieri, I.; Tortolano, V.; Clark, J.; Hemery, G. E.; Mapelli, S.; Malvolti M.E. Landscape genetics of Persian walnut (Juglans regia L.) across its Asian range. Tree Genet. Genomes 2014, 10, 1027–1043. [CrossRef]

- Pollegioni, P.; Woeste, K.; Chiocchini, F.; Lungo, S.D.; Ciolfi, M.; Olimpieri, I.; Tortolano, V.; Clark, J.; Hemery, G.E.; Mapelli, S.; Malvolti, M.E. Rethinking the history of common walnut (Juglans regia L.) in Europe: Its origins and human interactions. PLoS ONE 2017, 12(3), e0172541. [CrossRef]

- Aradhya, M.; Velasco D.; Ibrahimov, Z.; Toktoraliev, B.; Maghradze, D.; Musayev, M.; Bobokashvili, Z.; Preece, J. E. Genetic and ecological insights into glacial refugia of walnut (Juglans regia L.). PLoS ONE 2017, 12(10), e0185974. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Lheureux, F.; Dirlewanger, E. Walnut: past and future of genetic improvement. Tree Genetics & Genomes 2018, 14, 1 . [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, F.; Rezaei, M.; Heidari, P.; Hokmabadi, H.; Lawson, S. Identification and DNA Fingerprinting of Some Superior Persian Walnut Genotypes in Iran. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2021, 63, 393-402. [CrossRef]

- Bozhuyuk, M.R. Determination of the genetic diversity of walnut (Juglans regia L.) cultivar candidates from northeastern Turkey using SSR markers. Mitt. Klosterneuburg 2020, 70, 269-277.

- Ruiz-Garcia, L.; Lopez-Ortega G.; Fuentes, A.; Frutos, D. Identification of a walnut (Juglans regia L.) germplasm collection and evaluation of their genetic variability by microsatellite markers. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2011, 9(1), 179-192.

- Bernard, A.; Barreneche, T.; Lheureux, F.; Dirlewanger. E. Analysis of genetic diversity and structure in a worldwide walnut (Juglans regia L.) germplasm using SSR markers. PLOS ONE 2018, 13(11), e0208021. [CrossRef]

- Aradhya. M.; Woeste K.; Velasco, D. Genetic Diversity, Structure and Differentiation in Cultivated Walnut (Juglans regia L.). Acta Horticulturae 2010, 861, 127-132.

- Balapanov, I.; Suprun, I.; Stepanov, I.; Tokmakov, S.; Lugovskoy, A. Comparative analysis Crimean, Moldavian and Kuban Persian walnut collections genetic variability by SSR-markers. Sci. Hortic 2019, 253, 322-326. [CrossRef]

- Suprun, I.I.; Stepanov I.V.; Vahdati, K.; Tokmakov, S.V.; Balapanov, I.M.; Al-Nakib, E.A.; Khokhlov, S.Yu.; Sokolova, V.V. Analysis of genetic diversity in three Eastern European walnut germplasm collections. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 334, 113275. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.N.; Ma, Q.G.; Chen, Y.K.; Wang, B.Q.; Pei, D. Identification of major walnut cultivars grown in China based on nut phenotypes and SSR markers. Scientia Horticulturae 2014, 168, 240-248. [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Ullah, I.; Woeste, K.; Fiaz, S.; Zeb, U.; Ghazy, A. I.; Azizullah, A.; Shad, S.; Malvolti, M.E.; Yue, M.; et al Population genetics informs new insights into the phytogeographic history of Juglans regia L. Genet Resour Crop Evol 2023, 70, 2263–2278. [CrossRef]

- Pollegioni, P.; Woeste, K.E.; Chiocchini, F.; Lungo, S.D.; Olimpieri, I.; Tortolano, V.; Clark, J.; Hemery, G.E.; Mapelli, S.; Malvolti, M.E. Ancient Humans Influenced the Current Spatial Genetic Structure of Common Walnut Populations in Asia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10(9), e0135980. [CrossRef]

- Vahdati, K.; Mohseni Pourtaklu, S.; Karimi, R.; Barzehkar, R.; Amiri, R.; Mozaffari, M.; Woeste, K. Genetic diversity and gene flow of some Persian walnut populations in southeast of Iran revealed by SSR mrakers. Plant Syst Evol 2015, 301, 691-699.

- Shahi Shavvon, R.; Qi, H.L., Mafakheri, M.; Fan, P.-Z.; Wu, H.-Y.; Vahdati, F.B.; Al-Shmgani, H.S.; Wang, Y.-H.; Liu, J. Unravelling the genetic diversity and population structure of common walnut in the Iranian Plateau. BMC Plant Biol 2023, 23, 201. [CrossRef]

- Roor, V.; Konrad, H.; Mamadjanov, D.; Geburek, T. Population Differentiation in Common Walnut (Juglans regia L.) across Major Parts of Its Native Range-Insights from Molecular and Morphometric Data. Journal of Heredity 2017, 108(4), 391-404. [CrossRef]

- Gaisberger, H.; Legay, S.; Andre, C.; Loo, J.; Azimov, R.; Aaliev, S.; Bobokalonov, F.; Mukhsimov, N.; Kettle, C.; Vinceti, B. Diversity Under Threat: Connecting Genetic Diversity and Threat Mapping to Set Conservation Priorities for Juglans regia L. Populations in Central Asia. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 171. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pan, G.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, J.; Pei, D. The genetic diversity and introgression of Juglans regia and Juglans sigillata in Tibet as revealed by SSR markers. Tree Genetics & Genomes 2015, 11, 1. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, W.; Pan, G.; Pei, D. Analysis of genetic diversity and relationships among 86 Persian walnut (Juglans regia L.) genotypes in Tibet using morphological traits and SSR markers. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2015, 90(5), 563–570. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhou, H.; Zulfiqar, S.; Hu, Y.; Feng, L.; Malvolti, M.E.; Woeste, K.; Zhao, P. The Phytogeographic History of Common Walnut in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1399. [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Woeste, K.E.; Hu, Y.; Dang, M.; Zhang, T.; Gao, X.-X.; Zhou, H.; Feng, X.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, P. Genetic diversity and population structure of common walnut (Juglans regia) in China based on EST-SSRs and the nuclear gene phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL). Tree Genetics & Genomes 2016, 12, 111. [CrossRef]

- Magige, E.A.; Fan, P.-Z.; Wambulwa, M.C. Milne, R.; Wu, Z.-Y.; Luo, Y.-H.; Khan, R.; Wu, H.-Y.; Qi, H.-L.; Zhu, G.-F.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Structure of Persian Walnut (Juglans regia L.) in Pakistan: Implications for Conservation. Plants 2022, 11, 1652. [CrossRef]

- Shah, U.N.; Mir, J.I.; Ahmed, N.; Fazili, K.M. Assessment of germplasm diversity and genetic relationships among walnut (Juglans regia L.) genotypes through microsatellite markers. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences 2018, 17(4), 339-350. [CrossRef]

- Guney, M.; Kafkas, S.; Keles, H.; Zarifikhosroshahi, M.; Gundesli, M.A.; Ercisli, S.; Necas, T.; Bujdoso, G. Genetic Diversity among Some Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Genotypes by SSR Markers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6830. [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, P.G.; Paffetti, D.; Vettori, C.; Testolin, R. Genetic Diversity of Walnut (Juglans Regia L.) in the Eastern Italian Alps. Forests 2017, 8, 81. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Zarei, A.; Lawson, S.; Woeste, K.E.; Smulders, M.J.M. Genetic diversity and genetic structure of Persian walnut (Juglans regia) accessions from 14 European African, and Asian countries using SSR markers. Tree Genetics & Genomes 2016, 12, 114. [CrossRef]

- Voronov, Yu. N. Wild relatives of fruit trees and shrubs of the Caucasian region and the Near East. Proceedings on Applied Botany, genetics and breeding 1925, 14, 44.

- Ilyinsky, A.A. Walnut and other fruit trees in the forests of the Samur River delta. Proceedings of the Dagestan Agricultural Institute 1941, 3, 144-168.

- Gritsenko, N.P. Socio-economic development of the Twilight regions in the XVIII – first half of the XIX century. The works of CHINIYAL 1969, 4, 289.

- Magomedov, N.A. Regional and international transit trade in the Western Caspian Region in the XVII – XVIII centuries; Makhachkala: IIAE DNC RAS, ALEF, 2015; 184 p.

- Magaramov, S.A.; Chekulaev, N.D.; Inozemtseva, E.I. The history of the Derbent garrison of the Russian Imperial Army (1722-1735); Makhachkala: Publishing House "Lotus", 2021; 200 p.

- Ghobad-Nejhad, M. Wood-inhabiting basidiomycetes in the Caucasus region—systematics and biogeography. Publications in Botany from the University of Helsinki 2011, 40, 8-25.

- Carrión, J.S.; Sánchez-Gómez, P. Palynological data in support of the survival of walnut (Juglans regia L.) in the western Mediterranean during last glacial times. J. Biogeogr 1992, 19, 623–630. [CrossRef]

- Filipova-Marinova, M.V.; Kvavadze, E.V.; Connor, S.E.; Connor, S.E.; Sjögren, P. Estimating absolute pollen productivity for some European Tertiary-relict taxa. Veget Hist Archaeobot 2010, 19, 351–364. [CrossRef]

- Gogichaishvili, L.K. Vegetational and climatic history of the western part of the Kura River basin. In: Bintliff JL, van Zeist W (eds) Paleoclimates, paleoenvironments, and human communities in the Eastern Mediterranean region in later prehistory; B.A.R. International Series: Oxford, 1984; pp 325–341.

- Rogers, S. O.; Bendich, A. J. Extraction of DNA from milligram amounts of fresh, herbarium and mummified plant tissues. Plant Mol. Biol. 1985, 5, 69-76. [CrossRef]

- Woeste, K.; Burns, R.; Rhodes, O.; Michler, C. Thirty polymorphic nuclear microsatellite loci from black walnut. J Hered. 2002, 93(1), 58–60 . [CrossRef]

- Dangl, G.S.; Woeste, K.; Aradhya, M.K.; Pitcher, A. M. K. Characterization of 14 microsatellite markers for genetic analysis and cultivar identification of walnut. J Am Soc Hortic Sci 2005, 130, 348–354. [CrossRef]

- 59Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research--an update. Bioinformatics 2012, 28(19), 2537-9. [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [CrossRef]

- Earl, D.A.; von Holdt, B.M. Structure harvester: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. 2012, 4, 359-361. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, F.C.; Yang, R.C.; Boyle, T. POPGENE Version 1.32: Microsoft Window-Based Freeware for Population Genetics Analysis. University of Alberta, Edmonton 1999.

- Hammer, O.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 2001, 4(1), 1-9.

- Mamadzhanov, D.K. Recommendations for the introduction of the best varieties and forms of walnut, Institute of Forestry and Walnut Growing of the National Academy of Sciences of the Kyrgyz Republic named after prof. P.A. Gan.-B. 2005, 157, 499-506.

- Mamadzhanov, D.; Kenzhebaev, S.A. Walnut diversity and breeding in Kyrgyzstan. BIO Web of Conferences. International Scientific Online-Conference «Bioengineering in the Organization of Processes Concerning Breeding and Reproduction of Perennial Crops» 2020, 25, 02009. [CrossRef]

- Curkan, I.P. Walnut; Kishineu, 2004, P. 156.

- Vischi, M.; Chiabà, C.; Raranciuc, S.; Poggetti, L.; Messina, R.; Ermacora, P.; Cipriani, G.; Paffetti, D.; Vettori, C.; Testolin, R. Genetic Diversity of Walnut (Juglans Regia L.) in the Eastern Italian Alps. Forests 2017, 8, 81. [CrossRef]

- Vranckx, G.; Jacquemyn, H.; Muys, B.; Honnay, O. Meta-analysis of susceptibility of woody plants to loss of genetic diversity through habitat fragmentation. Conserv. Biol 2012, 26, 228–237. [CrossRef]

- Garnier-Géré, P.; Chikhi, L. Population subdivision, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and the Wahlund effect; In eLS; John Wiley andSons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Kanaka, K.K.; Sukhija, N.; Goli, R. Ch.; Singh, S.; Ganguly, I.; Dixit, S.P.; Dash, A.; Malik, М. On the concepts and measures of diversity in the genomics era. Current Plant Biology 2023, 33, 100278. [CrossRef]

- Pollegioni, P.; Woeste, K.; Olimpieri, I.; Marandola, D.; Cannata, F.; Malvolti, M.E. Long-term human impacts on genetic structure of Italian walnut inferred by SSR markers. Tree Genetics & Genomes 2011, 7, 707–723. [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.N.; Zeng, Y.F.; Zhang D.Y. Mating patterns and pollen dispersal in a heterodichogamous tree, Juglans mandshurica (Juglandaceae). New Phytol 2007, 176, 699–707. doi.10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02202.x.

- Robichaud, R.L.; Glaubitz, J.C.; Rhodes, O.E.; Woeste, K. A. Robust set of black walnut microsatellites for parentage and clonal identification. New Forests 2006, 32, 179–196. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Lawson, S.S.; Frank, G.S.; Coggeshall, M.V.; Woeste, K.E.; McKenna, J.R. Pollen flow and paternity in an isolated and non-isolated black walnut (Juglans nigra L.) timber seed orchard. PLoS One 2018, 13(12), e0207861. [CrossRef]

- Polito. V.S.; Pinney, K.; Weinbaum, S. et al. Walnut pollination dynamics: pollen flow in walnut orchards. In V International Walnut Symposium 2004, 705, 465–472. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2005.705.68.

- Gunn, B. F.; Aradhya, M.; Salick, J. M. Genetic variation in walnuts (Juglans regia and J. sigillata; Juglandaceae): Species distinctions, human impacts, and the conservation of agrobiodiversity in Yunnan, China. American Journal of Botany 2010, 97(4), 660–671. [CrossRef]

- Caciagli, L.; Bulayeva, K.; Bulayev, O.; Bertoncini, S.; Taglioli, L.; Pagani, L.; Paoli, G.; Tofanelli, S. The key role of patrilineal inheritance in shaping the genetic variation of Dagestan highlanders. J Hum Genet 2009, 54, 689–694. [CrossRef]

| Locus | Na | Ne | I | Ho | He | F |

| WGA001 | 8 | 3,477 | 1,466 | 0,633 | 0,712 | 0,112 |

| WGA376 | 11 | 6,052 | 2,032 | 0,709 | 0,835 | 0,151 |

| WGA069 | 14 | 4,606 | 1,814 | 0,462 | 0,783 | 0,41 |

| WGA276 | 20 | 9,678 | 2,504 | 0,759 | 0,897 | 0,153 |

| WGA009 | 7 | 2,198 | 1,1 | 0,513 | 0,545 | 0,06 |

| WGA202 | 14 | 5,286 | 1,912 | 0,741 | 0,811 | 0,087 |

| WGA089 | 7 | 1,923 | 0,906 | 0,494 | 0,48 | -0,028 |

| WGA321 | 10 | 3,981 | 1,551 | 0,69 | 0,749 | 0,079 |

| WGA 72 | 4 | 3,424 | 1,289 | 0,297 | 0,708 | 0,58 |

| WGA 79 | 9 | 3,618 | 1,455 | 0,722 | 0,724 | 0,003 |

| WGA 4 | 4 | 2,635 | 1,037 | 0,576 | 0,62 | 0,072 |

| Mean | 9,818 | 4,262 | 1,552 | 0,6 | 0,715 | 0,152 |

| Regions | N | Na | Ne | Ne/Na | I | Ho | He | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South of Mountain Dagestan | 74 | 7.545 | 3.444 | 0.456 | 1.376 | 0.574 | 0.662 | 0.114 |

| North of Mountain Dagestan | 33 | 5.273 | 2.991 | 0.567 | 1.254 | 0.545 | 0.646 | 0.146 |

| Flatland Dagestan | 51 | 7.455 | 4.024 | 0.540 | 1.491 | 0.672 | 0.715 | 0.067 |

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % | F-statistica |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South and North of Mountain Dagestan | ||||||

| Among Pops | 1 | 16.559 | 16.559 | 0.140 | 4% | Fst=0.036 |

| Among Indiv | 105 | 443.090 | 4.220 | 0.556 | 15% | Fis=0.151 |

| Within Indiv | 107 | 332.500 | 3.107 | 3.107 | 82% | Fit=0.183 |

| Total | 213 | 792.150 | 3.804 | 100% | Nm=6.54 | |

| South of Mountain Dagestan and Flatland Dagestan | ||||||

| Among Pops | 1 | 44.231 | 44.231 | 0.331 | 8% | Fst=0,080 |

| Among Indiv | 123 | 517.853 | 4.210 | 0.417 | 10% | Fis=0,110 |

| Within Indiv | 125 | 422.000 | 3.376 | 3.376 | 82% | Fit=0.181 |

| Total | 249 | 984,084 | 4,124 | 100% | Nm= 2.86 | |

| North of Mountain Dagestan and Flatland Dagestan | ||||||

| Among Pops | 1 | 38.299 | 38.299 | 0.425 | 10% | Fst=0.100 |

| Among Indiv | 82 | 348.052 | 4.245 | 0.411 | 10% | Fis=0.107 |

| Within Indiv | 84 | 287.500 | 3.423 | 3.423 | 80% | Fit=0.196 |

| Total | 167 | 673.851 | 4.259 | 100% | Nm=2.26 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).