Submitted:

22 May 2023

Posted:

23 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. DNA isolation

2.3. PCR amplification for SRAP markers

2.4. Agarose gel electrophoresis

2.5. Parameters used for analysis of SRAP markers

3. Results and analysis

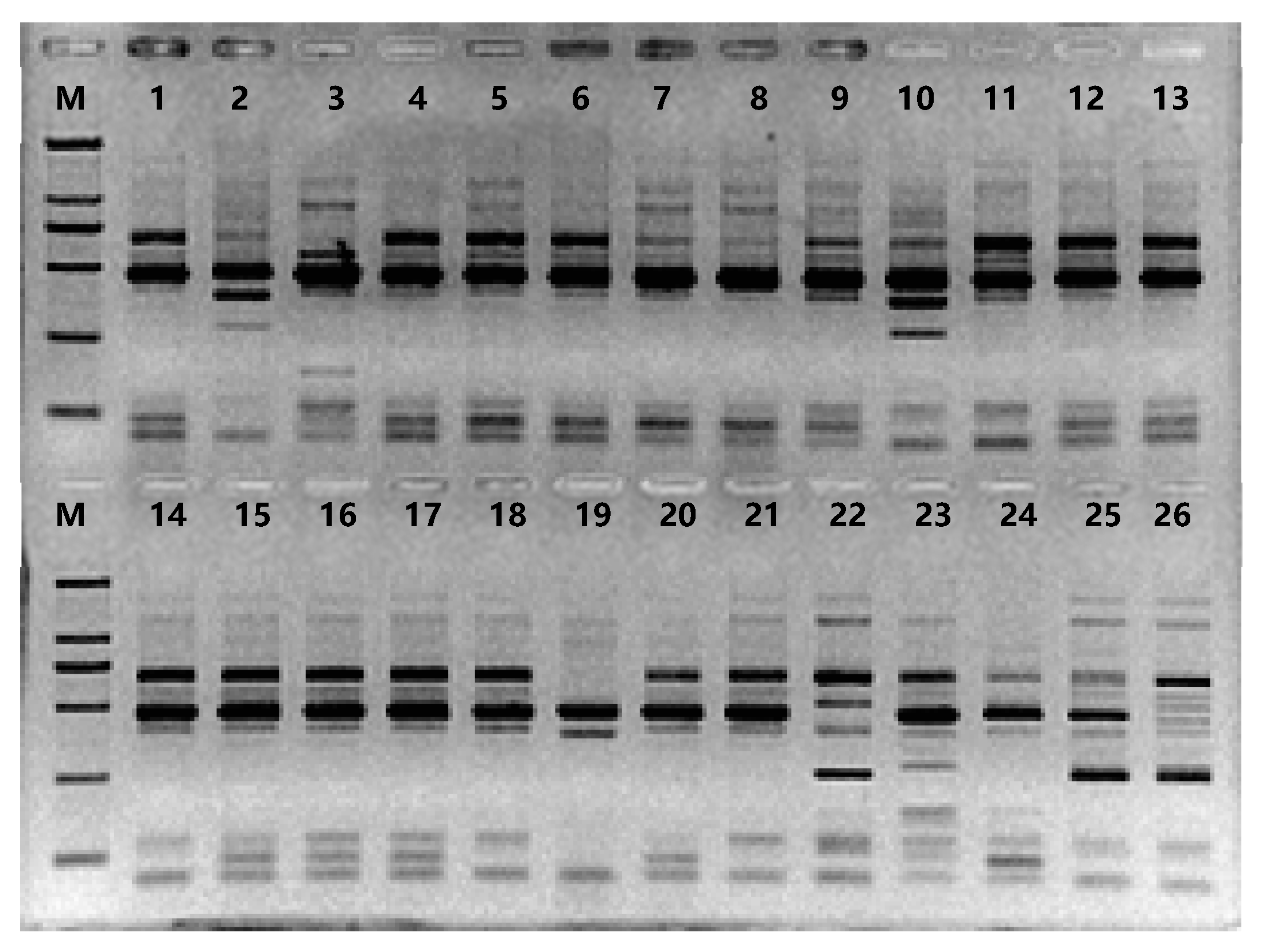

3.1. Polymorphism analysis using SRAP markers

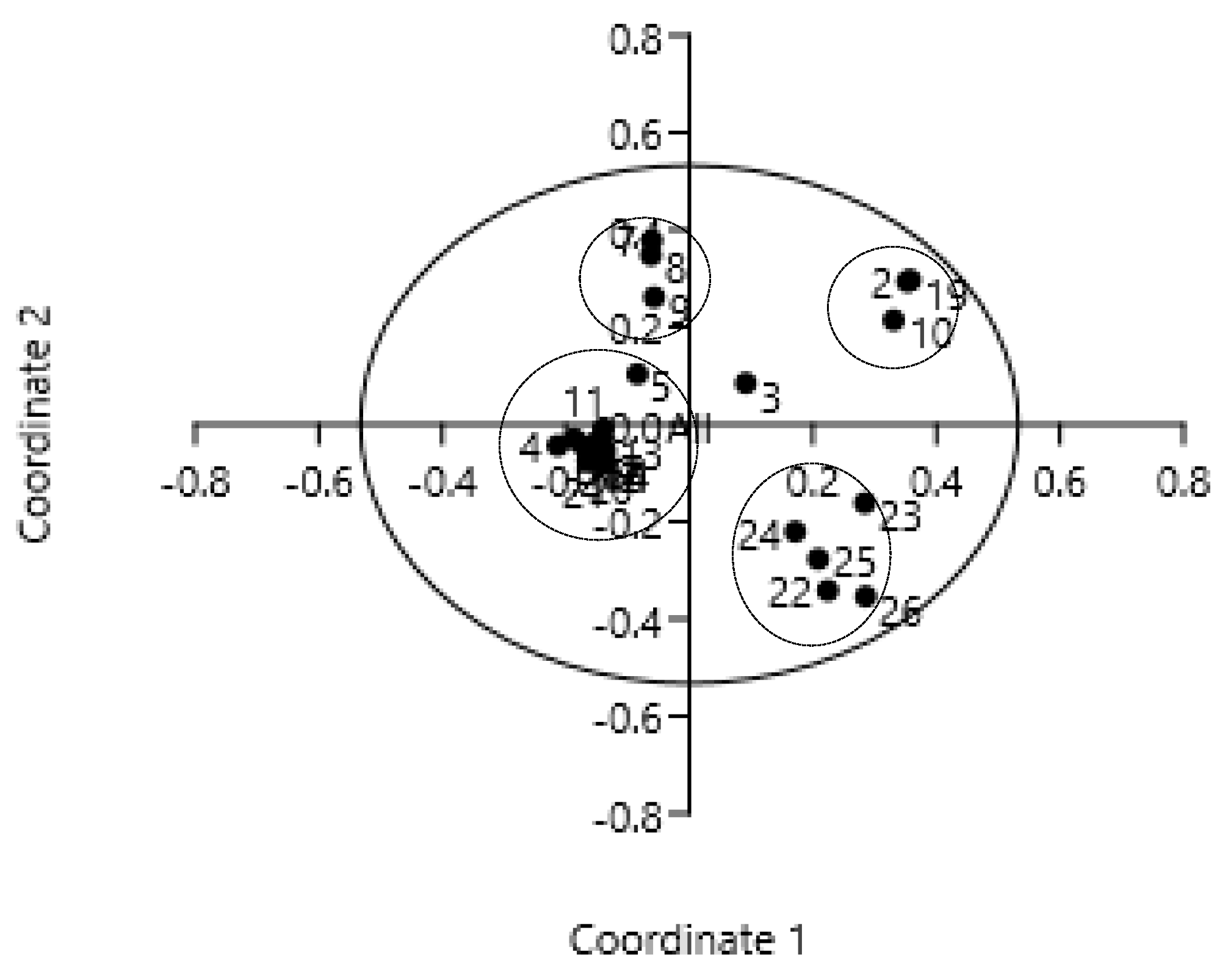

3.2. Principal Coordinate Analysis

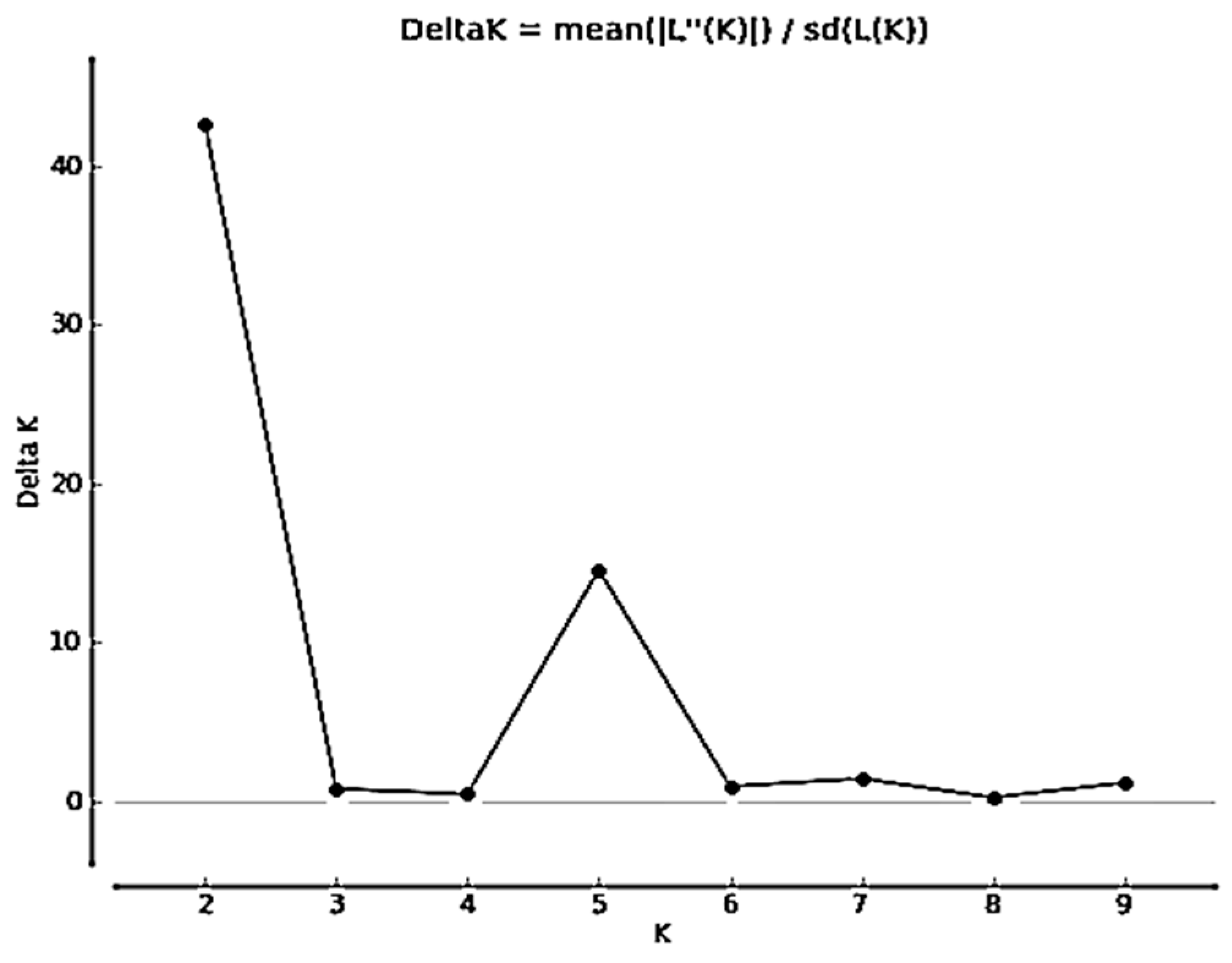

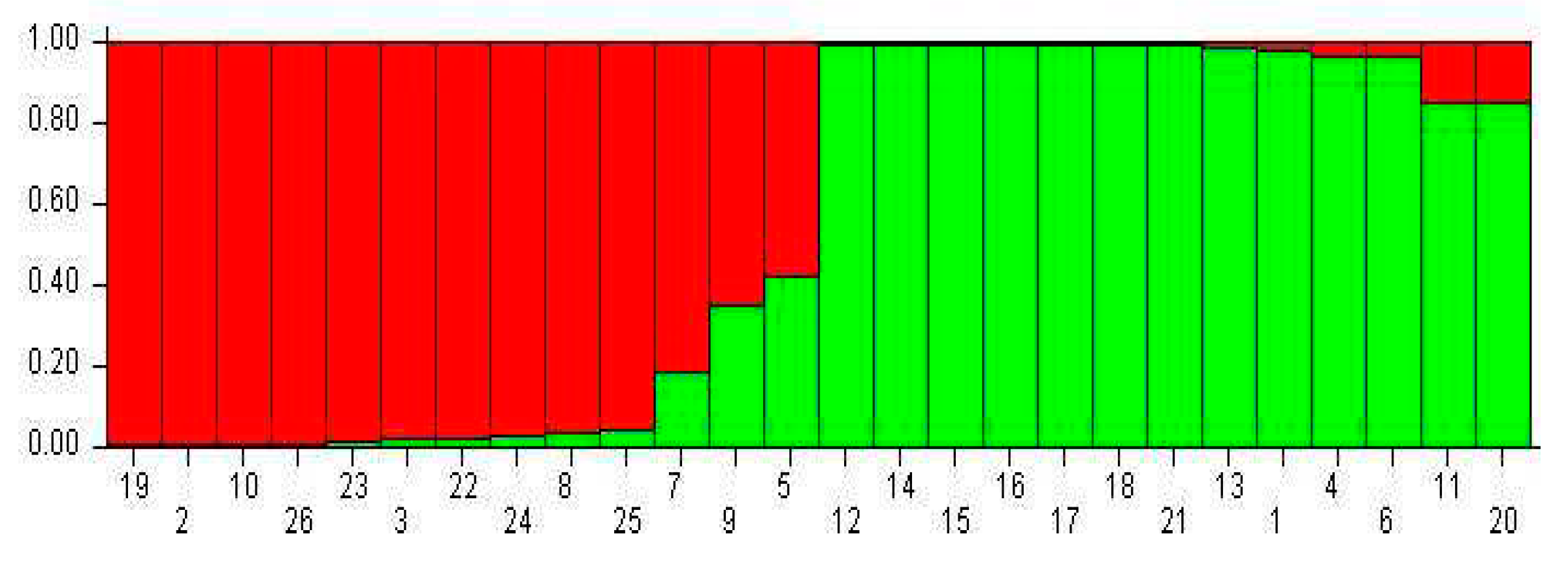

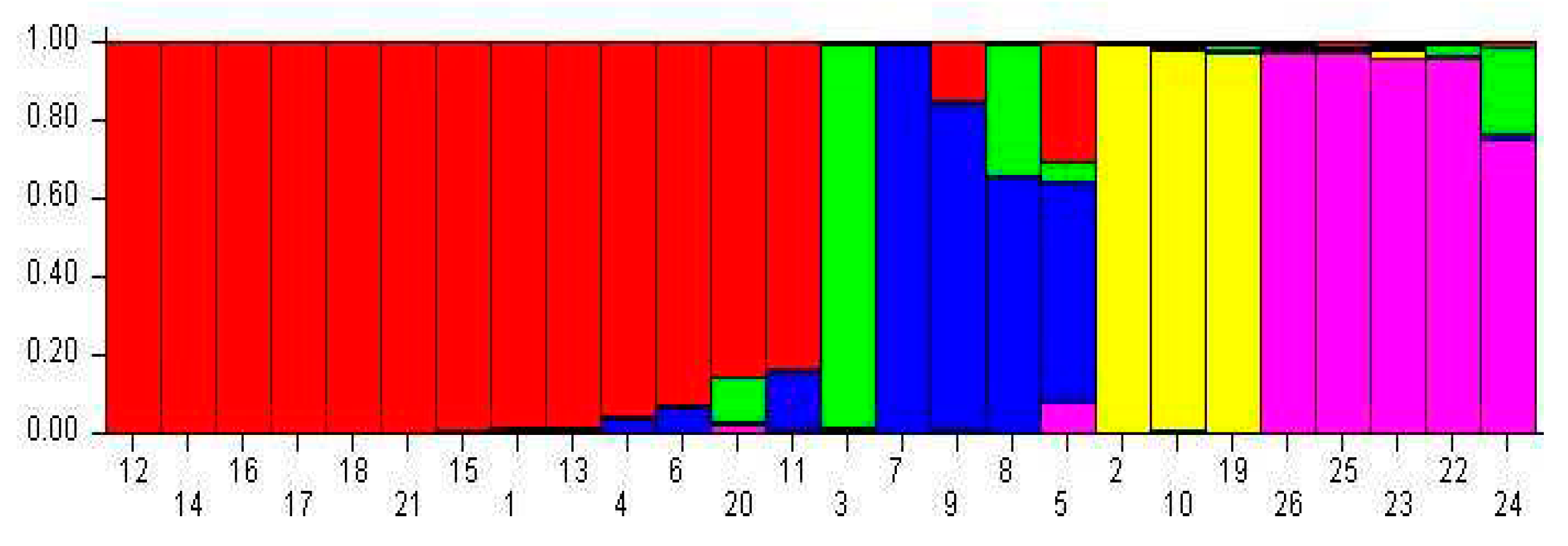

3.3. Population Structure Analysis

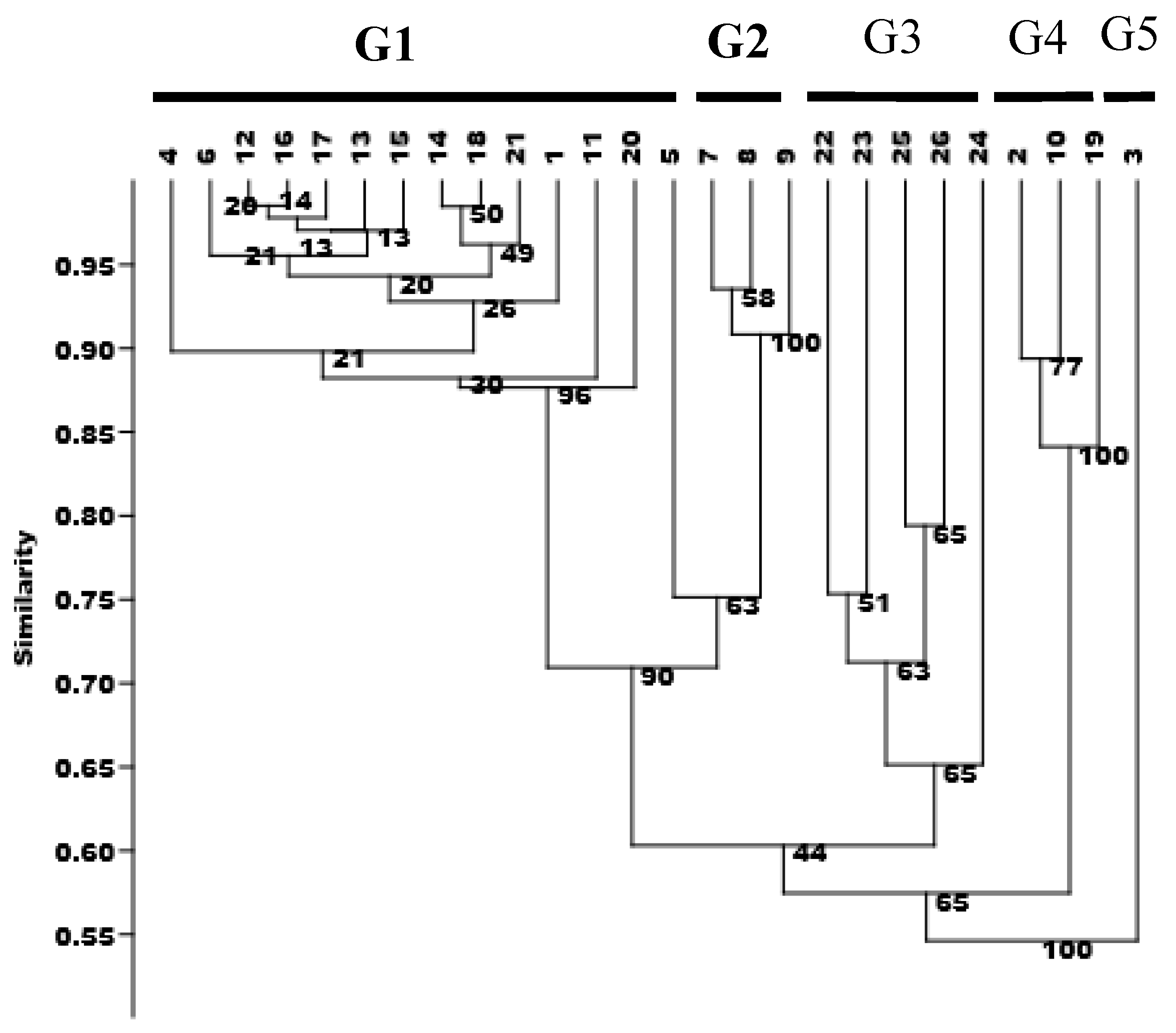

3.4. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA)

3.5. Screening of genotype-specific markers and identification od kumquat accessions

4. Discussion

References

- Liu Binghao; Deng Chongling; Chen Chuanwu; Deng Guangzhou; Ding Ping; Niu Ying; Tang Yan; Fu Huimin. ISSR analysis of local citrus resources in Guangxi. Journal of Fruit Science. 2015, 32, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Li Guoguo; Liu Yaoxin; Chai Lijun; Ye Junli; Mai Caisheng; Ou Zhitao; Chen Xiangling. Ploidy Analysis and SSR Molecular Identification of Gui Wild Shanjingan. Southwest China Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 2017, 30, 1872–1876. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Guixiang; Guo Liying; Zhang Shuwei; He Xinhua; Zhou Ruiyang; Chen Hu; Yang Chunjiang. Genetic relationship analysis of Fortunella germplasm resources from China and Vietnam by ISSR markers. Journal of Fruit Science. 2011, 28, 563–567. [Google Scholar]

- Chenqiao Zhu; Peng Chen; Junli Ye; Hang Li; Yue Huang; Xiaoming Yang; Chuanwu Chen; Chenglei Zhang; Yuantao Xu; Xiaoli Wang; Xiang Yan; Guangzhou Deng; Xiaolin Jiang; Nan Wang; Hongxing Wang; Quan Sun; Yun Liu; Di Feng; Min Yu; Xietian Song; Zongzhou Xie; Yunliu Zeng; Lijun Chai; Qiang Xu; Chongling Deng; Yunjiang Cheng; Xiuxin Deng. New insights into the phylogeny and speciation of kumquat (Fortunella spp.) based on chloroplast SNP, nuclear SSR and whole-genome sequencing. Front. Agr. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Zhonghai; Zhang Anshi; Gao Dengtao; Wei Zhifeng. Genetic diversity analysis and rapid identification of Grapevine Jufeng Cultivars by MCID method. Journal of Northeast Agricultural Sciences. 2022, 4, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan Heqin; Zheng Wei; Dai Jiani; Yan Wuping; Yu Jing; Wu Yougen. Based on camellia species genetic diversity analysis of a molecular marker hainan. Journal of molecular plant breeding. 2022, 20, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Yu; Huang Guodi; Mo Yonglong; Luo Shixing; Zhao Ying; Tang Yujuan; Lu Zushuang; Shan Bin; Rong Tao. CDDP combination of a tag analysis Mang fruit species genetic diversity. South China Fruits. 2022, 2, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun Lili; Peng Lina; Li Zheng; Hou Ruining; Mou Yunhui. Using ISSR and mark build li genetic linkage map. Journal of guangdong agricultural sciences. 2022, 49, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang Wu; Li Yaping; Chen Jiadong; Tao Zhengming. Study on Genetic diversity of Polygonum sativum based on ISSR and SRAP markers [J/OL]. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 2022, 1–9. Available online: http:// http://fffg208e51c2dd88406685526280e50de659hn95vov6v6nc96vfw.fgfy.www.gxstd.com/kcms/detail/12.1108.R.20220929.1912.006. /.

- Wen Zhang; Wei Hu; Xin-Yu Zhang; Min Zhou; Qiao-Qiao Jiang; Zn-Niu Deng; Da-Zhi Li. Identification of the hybrid progeny of Shatian Pomelo × citron by embryo rescue technique and its SRAP detection. Journal of Fruit Science. 2013, 30, 386–389. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Lihua; Han Haozhang; Wang Xiaoli; Li Suhua; Wang Fang; Dong Rong; Liu Yu. Screening of molecular markers for SRAP of Cinnamomum camphora. Anhui Agricultural Science Bulletin. 2019, 25, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing Xu; Limei Tan; Hongyan Fu; Zhimei Zhu; Libing Long; Zhe Hu; Xianfeng Ma; Ziniu Deng. Molecular markers were used to analyze the diversity of 14 citron accessions. Molecular plant breeding. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/46.1068.S.20200401.1548.004.

- Jaccard, P. Nouvelles recherches sur la distribution florale. Bull. Soc. Vaud. Sci. Nat. 1908, 44, 223–270. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.; Ryan, P.D. Past: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghamedi, K.; Alaraidh, I.; Afzal, M.; Mahdhi, M.; Al-Faifi, Z.; Oteef, M.D.Y.; Tounekti, T.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Khemira, H. Assessment of Genetic Diversity of Local Coffee Populations in Southwestern Saudi Arabia Using SRAP Markers. Agronomy 2023, 13, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard J K, Stephens M J, Donnelly P J. Inference of Population Structure Using Multilocus Genotype Data[J]. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl D A, Vonholdt B M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method[J]. Conservation Genetics Resources 2012, 4, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chown, S.L.; Hodgins, K.A.; Griffin, P.C.; Oakeshott, J.G.; Byrne, M.; Hoffmann, A.A. Biological invasions, climate change, and genomics. In Crop Breeding: Bioinformatics and Preparing for Climate Change; Santosh, K., Ed.; Apple Academic Press: Waretown, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Murish, T.M.; Elshafei, A.A.; Al-Doss, A.A.; Barakat, M.N. Genetic diversity of coffee (Coffea arabica L.)in Yemen via SRAP, TRAP and SSR markers. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 11, 411–416. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, N.; Choudhary, S.; Naaz, N.; Sharma, N.; Laskar, R.A. Recent advancements in molecular marker-assisted selection and applications in plant breeding programmes. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem, M.A.; Nawaz, M.A.; Shahid, M.Q.; Do ˘gan, Y.; Comertpay, G.; Yıldız, M.; Hatipo ˘glu, R.; Ahmad, F.; Alsaleh, A.; Labhane, N. DNA molecular markers in plant breeding: Current status and recent advancements in genomic selection and genome editing. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2018, 32, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamedi, K.; Alaraidh, I.; Afzal, M.; Mahdhi, M.; Al-Faifi, Z.; Oteef, M.D.Y.; Tounekti, T.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Khemira, H. Assessment of Genetic Diversity ofLocal Coffee Populations in Southwestern Saudi Arabia Using SRAP Markers. Agronomy 2023, 13, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Kun, Zhou Yuanjie, Li Yao, Liu Xinling, Guo Yuqi, Xia Hui, Liang Dong. Genetic Diversity Analysis of Kiwifruit Germplasm based on SRAP and SCoT markers [J]. Journal of Fruit Science 2021, 38, 2059–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchu Hu, Xiaobo Wu, Zhe Chen, Fengzhi Wu, Wenjing Zhou, Xuejie Feng, Hongyan Fan, Ruiyun Zhou, Xianghe Wang. Genetic diversity Analysis of Litchi germplasm resources based on SRAP molecular markers [J]. Journal of Tropical Crops 2021, 42, 920–926. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Committee of Flora of China, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Flora of China, Kumquat [M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2004. http://www.iplant.cn/frps/cname/J.

- Wang Ting,Chen LingLing,Shu HuiJuan,You Fang,Liang XiaoLi,Li Jun,Ren Jing,Wanga Vincent Okelo,Mutie Fredrick Munyao,Cai XiuZhen,Liu KeMing,Hu GuangWan. Fortunella venosa (Champ. ex Benth.) C. C. Huang and F. hindsii (Champ. ex Benth.) Swingle as Independent Species: Evidence From Morphology and Molecular Systematics and Taxonomic Revision of Fortunella(Rutaceae)[J]. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 867659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou Kailong, Ye Yinmin. Chinese fruit trees citrus Roll [M]. Beijing: Beijing Forestry Publishing House,2010:126-130,427-433.

- Yasuda, K., M. Yahata, H. Komatsu and H. Kunitake. Phylogeny and classification of Fortunella (Aurantioideae) inferred from DNA polymorphisms. Bul. Fac. Agr. Univ. Miyazaki 2010, 56, l03–110. [Google Scholar]

- Li Huifeng, Ran Kun, Wang Tao. Construction of fingerprint of apple resources in Shandong Province by using SRAP markers [J]. Journal of Shenyang Agricultural University 2020, 51, 470–475. [Google Scholar]

- Anshi Zhang, Qingliang Si, Xiujuan Qi, Zhonghai Zhang. Genetic diversity Analysis and fingerprint Construction of Germplasm resources of Kiwifruit [J]. Jiangsu Agricultural Journal 2018, 34, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Shang Xiaoxing, Zhang Anshi, Liu Ying, Gao Dengtao. Genetic diversity Analysis and fingerprint Construction of Grapevine Germplasm resources based on SRAP [J]. Molecular plant breeding 2020, 18, 1916–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Abbreviation | Genotype Name | Scientific name | Possible origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NB jindan | Ningbo jindan | F. crassifolia | Ningbo, Zhejiang |

| 2 | Daguojindou | Daguojindou | F. hindsii | Citrus Research Institute, SWU/CAAS |

| 3 | Jinganzazhong | Guangxi natural kumquat hybrid | Citrus x Fortunella | Hezhou, Guangxi |

| 4 | WZ luofu | Wenzhou luofu | F. margarita | Wenzhou, Zhejiang |

| 5 | NB luofu | Ningbo luofu | F. margarita | Ningbo, Zhejiang |

| 6 | WZ jingdan | Wenzhou jingdan | F. crassifolia | Wenzhou, Zhejiang |

| 7 | Sijiju | Sijiju | Citrus x Fortunella | Citrus Research Institute, SWU/CAAS |

| 8 | Wenzhouju | Wenzhouju (kumquat hybrid) | Citrus x Fortunella | Wenzhou, Zhejiang |

| 9 | Shouxingju | Shouxingju (kumquat hybrid) | Citrus x Fortunella | Citrus Research Institute, SWU/CAAS |

| 10 | Dajindou | Dajindou | F. hindsii | Citrus Research Institute, SWU/CAAS |

| 11 | NB luowen | Ningbo luowen | F. japonica | Ningbo, Zhejiang |

| 12 | RA jingan | Rongan jingan | F. crassifolia | Liuzhou, Guangxi |

| 13 | FY jingan | Fuyuan jingan | F. crassifolia | Liuzhou, Guangxi |

| 14 | CM jingan | Cuimi jingan | F. crassifolia | Liuzhou, Guangxi |

| 15 | Guijingan1 | Guijingan No.1 | F. crassifolia | Yangshuo, Guangxi |

| 16 | Guijingan2 | Guijingan No.2 | F. crassifolia | Yangshuo, Guangxi |

| 17 | YS jingan | Yangshuo jingan | F. crassifolia | Yangshuo, Guangxi |

| 18 | F15-1 | F15-1 | F. crassifolia | Liuzhou, Guangxi |

| 19 | Shanjingan | Hunan Shanjingan | F. hindsii | Changsha, Hunan |

| 20 | LY jingan | Liuyang jingan | F. crassifolia | Changsha, Hunan |

| 21 | HP jingan | Huapi jingan | F. crassifolia | Liuzhou, Guangxi |

| 22 | FC-1 | Guangxi wild kumquat FC-1 | Fortunella sp. | Fangchenggang, Guangxi |

| 23 | FC-2 | Guangxi wild kumquat FC-2 | Fortunella sp. | Fangchenggang, Guangxi |

| 24 | FC-3 | Guangxi wild kumquat FC-3 | Fortunella sp. | Fangchenggang, Guangxi |

| 25 | FC-4 | Guangxi wild kumquat FC-4 | Fortunella sp. | Fangchenggang, Guangxi |

| 26 | FC-5 | Guangxi wild kumquat FC-5 | Fortunella sp. | Fangchenggang, Guangxi |

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5’-3’) | Primer name | Primer sequence (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ME1 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAAA | EM1 | GACTGCGTACGAATTAAC |

| ME2 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAAC | EM2 | GACTGCGTACGAATTAAT |

| ME3 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAAG | EM3 | GACTGCGTACGAATTACG |

| ME4 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAAT | EM4 | GACTGCGTACGAATTAGC |

| ME5 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGACA | EM5 | GACTGCGTACGAATTATG |

| ME6 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGACC | EM6 | GACTGCGTACGAATTCAA |

| ME7 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGACG | EM7 | GACTGCGTACGAATTCAC |

| ME8 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGACT | EM8 | GACTGCGTACGAATTCAG |

| ME9 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAGA | EM9 | GACTGCGTACGAATTCAT |

| ME10 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAGC | EM10 | GACTGCGTACGAATTCCA |

| ME11 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAGG | EM11 | GACTGCGTACGAATTCGA |

| ME12 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGATA | EM12 | GACTGCGTACGAATTCGG |

| ME13 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGTAA | EM13 | GACTGCGTACGAATTCTA |

| ME14 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGTAG | EM14 | GACTGCGTACGAATTCTC |

| ME15 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGTCA | EM15 | GACTGCGTACGAATTCTG |

| ME16 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGTCC | EM16 | GACTGCGTACGAATTCTT |

| ME17 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGTGC | EM17 | GACTGCGTACGAATTGAT |

| ME18 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGTGT | EM18 | GACTGCGTACGAATTGCA |

| ME19 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGTTA | EM19 | GACTGCGTACGAATTGGT |

| ME20 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGTTG | EM20 | GACTGCGTACGAATTGTC |

| EM21 | GACTGCGTACGAATTTAG | ||

| EM22 | GACTGCGTACGAATTTCG | ||

| EM23 | GACTGCGTACGAATTTGA | ||

| EM24 | GACTGCGTACGAATTTGC |

| No. | Primer | Amplified bands | Polymorphic bands | Polymorphic rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Me1Em15 | 6 | 4 | 66.67 |

| 2 | Me1Em22 | 4 | 4 | 100.00 |

| 3 | Me1Em23 | 6 | 6 | 100.00 |

| 4 | Me2Em17 | 6 | 6 | 100.00 |

| 5 | Me9Em23 | 7 | 4 | 57.14 |

| 6 | Me2Em21 | 6 | 5 | 83.33 |

| 7 | Me10Em7 | 10 | 8 | 80.00 |

| 8 | Me4Em7 | 1 | 1 | 100.00 |

| 9 | Me4Em12 | 10 | 8 | 80.00 |

| 10 | Me3Em17 | 4 | 4 | 100.00 |

| 11 | Me4Em17 | 4 | 4 | 100.00 |

| 12 | Me11Em21 | 2 | 2 | 100.00 |

| 13 | Me10Em13 | 4 | 4 | 100.00 |

| 14 | Me14Em12 | 6 | 6 | 100.00 |

| 15 | Me16Em19 | 4 | 2 | 50.00 |

| 16 | Me7Em4 | 10 | 8 | 80.00 |

| 17 | Me20Em2 | 5 | 5 | 100.00 |

| 18 | Me17Em2 | 2 | 2 | 100.00 |

| 19 | Me18Em22 | 5 | 5 | 100.00 |

| Sum/Average | 102/5.37 | 88/4.63 | 86.27 | |

| Axis | Eigenvalue | Cumulative Eigenvalue | Percent (%) | Cumulative (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 34.80 | 34.80 |

| 2 | 0.29 | 0.83 | 19.25 | 54.05 |

| 3 | 0.19 | 1.02 | 12.74 | 66.78 |

| 4 | 0.17 | 1.19 | 10.90 | 77.68 |

| 5 | 0.09 | 1.28 | 5.67 | 83.35 |

| 6 | 0.08 | 1.36 | 5.38 | 88.72 |

| 7 | 0.03 | 1.39 | 2.10 | 90.82 |

| 8 | 0.02 | 1.41 | 1.61 | 92.43 |

| 9 | 0.02 | 1.43 | 1.34 | 93.76 |

| 10 | 0.02 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 94.78 |

| 11 | 0.01 | 1.46 | 0.78 | 95.56 |

| 12 | 0.01 | 1.47 | 0.52 | 96.08 |

| 13 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 0.24 | 96.32 |

| 14 | 0.00 | 1.48 | 0.11 | 96.42 |

| 15 | 0.00 | 1.48 | 0.00 | 96.43 |

| 16 | 0.00 | 1.48 | 0.00 | 96.43 |

| No. | Germplasm | 1.NB jindan 2.Daguojindou 3.Jinganzazhong 4.WZ luofu5.NB luofu 6.WZ jingdan 7.Sijiju 8.Wenzhouju 9.Shouxingju 10.Dajindou 11.NB luowen 12.RA jingan 13.FY jingan 14.CM jingan 15.Guijingan116.Guijingan2 17.YS jingan18.F15-1 19.Shanjingan 20.LY jingan 21.HP jingan 22.FC14-1 23.FC14-2 24.FC14-3 25.FC14-4 26.FC14-5 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | NB jindan | 1.000 |

| 2 | Daguojindou | 0.634 1.000 |

| 3 | Jinganzazhong | 0.634 0.604 1.00 |

| 4 | WZ luofu | 0.941 0.634 0.594 1.000 |

| 5 | NB luofu | 0.812 0.6436 0.584 0.851 1.000 |

| 6 | WZ jingdan | 0.941 0.634 0.653 0.921 0.812 1.000 |

| 7 | Sijiju | 0.762 0.673 0.634 0.762 0.851 0.782 1.000 |

| 8 | Wenzhouju | 0.703 0.594 0.584 0.703 0.772 0.703 0.871 1.000 |

| 9 | Shouxingju | 0.822 0.673 0.673 0.782 0.831 0.822 0.941 0.851 1.000 |

| 10 | Dajindou | 0.663 0.931 0.594 0.644 0.673 0.663 0.663 0.584 0.703 1.000 |

| 11 | NB luowen | 0.911 0.663 0.644 0.911 0.822 0.911 0.772 0.723 0.832 0.693 1.000 |

| 12 | RA jingan | 0.960 0.653 0.653 0.941 0.812 0.980 0.762 0.703 0.822 0.683 0.931 1.000 |

| 13 | FY jingan | 0.950 0.663 0.663 0.931 0.802 0.970 0.752 0.693 0.812 0.693 0.921 0.990 1.000 |

| 14 | CM jingan | 0.941 0.673 0.653 0.921 0.792 0.960 0.743 0.683 0.802 0.703 0.931 0.980 0.970 1.000 |

| 15 | Guijingan1 | 0.950 0.644 0.644 0.950 0.822 0.970 0.772 0.693 0.812 0.673 0.921 0.990 0.980 0.970 1.000 |

| 16 | Guijingan2 | 0.970 0.644 0.663 0.931 0.802 0.970 0.772 0.712 0.832 0.673 0.921 0.990 0.980 0.970 0.980 1.000 |

| 17 | YS jingan | 0.960 0.653 0.653 0.941 0.792 0.960 0.782 0.723 0.822 0.663 0.911 0.980 0.970 0.960 0.970 0.990 1.000 |

| 18 | F15-1 | 0.931 0.683 0.644 0.931 0.782 0.950 0.752 0.693 0.792 0.693 0.921 0.970 0.960 0.990 0.960 0.960 0.970 1.000 |

| 19 | Shanjingan | 0.644 0.911 0.594 0.644 0.653 0.624 0.683 0.614 0.683 0.881 0.653 0.644 0.653 0.663 0.634 0.653 0.663 0.673 1.000 |

| 20 | LY jingan | 0.941 0.634 0.634 0.921 0.772 0.901 0.743 0.703 0.782 0.644 0.871 0.921 0.911 0.901 0.911 0.931 0.941 0.911 0.644 1.000 |

| 21 | HP jingan | 0.960 0.653 0.653 0.921 0.792 0.941 0.743 0.693 0.802 0.683 0.931 0.960 0.950 0.980 0.950 0.970 0.960 0.970 0.663 0.921 1.000 |

| 22 | FC14-1 | 0.683 0.634 0.574 0.644 0.634 0.683 0.584 0.525 0.644 0.663 0.693 0.703 0.713 0.703 0.693 0.713 0.703 0.693 0.644 0.6434 0.703 1.000 |

| 23 | FC14-2 | 0.703 0.713 0.554 0.663 0.693 0.683 0.683 0.614 0.723 0.743 0.713 0.703 0.713 0.703 0.693 0.713 0.703 0.693 0.723 0.663 0.703 0.822 1.000 |

| 24 | FC14-3 | 0.693 0.644 0.683 0.673 0.743 0.713 0.653 0.604 0.693 0.653 0.723 0.713 0.723 0.713 0.703 0.703 0.693 0.703 0.634 0.673 0.713 0.713 0.772 1.000 |

| 25 | FC14-4 | 0.762 0.693 0.614 0.723 0.733 0.723 0.663 0.614 0.683 0.723 0.733 0.743 0.733 0.743 0.733 0.752 0.743 0.733 0.703 0.762 0.762 0.802 0.822 0.772 1.000 |

| 26 | FC14-5 | 0.683 0.653 0.594 0.663 0.673 0.644 0.604 0.545 0.624 0.683 0.653 0.663 0.673 0.663 0.653 0.673 0.683 0.673 0.663 0.703 0.683 0.762 0.782 0.733 0.861 1.000 |

| Code | Genotypes | Unique specific markers |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | NB jindan | M1E15(1800-), M3E17(250-) |

| 2 | Daguojindou | M1E23(400-) |

| 3 | Jinganzazhong | M1E22(250+), M4E17(500+), M9E23(700-), M10E13(200+) |

| 4 | WZ luofu | None |

| 5 | NB luofu | M2E21(400-), M3E17(450+), M11E21(250+) |

| 6 | WZ jingdan | M2E21(450+), M16E9(350-) |

| 7 | Sijiju | M4E12(1300-) |

| 8 | Wenzhouju | M17E2(530-) |

| 9 | Shouxingju | None |

| 10 | Dajindou | M3E17(100+), M4E17(250-) |

| 11 | NB luowen | none |

| 12 | RA jingan | None |

| 13 | FY jingan | None |

| 14 | CM jingan | None |

| 15 | Guijingan1 | None |

| 16 | Guijingan2 | None |

| 17 | YS jingan | None |

| 18 | F15-1 | None |

| 19 | Shanjingan | M1E22(300-) |

| 20 | LY jingan | M7E4(500+) |

| 21 | HP jingan | None |

| 22 | FC-1 | M2E17(500+), M2E17(1000+) |

| 23 | FC-2 | M4E7(500-) |

| 24 | FC-3 | None |

| 25 | FC-4 | M4E17(300+) |

| 26 | FC-5 | M14E12(1300+) |

| Genotypes | Common specific markers | Combination of unique markers |

|---|---|---|

| FC-3 | M3E17(180+) FC-2; FC-4; FC-5 | FC-2 M4E7(500-); FC-4 M4E17(300+); FC-5 M14E12(1300+) |

| M1E23(500+) Daguojindou | Daguojindou M1E23(400-) | |

| Shouxingju | M2E21(400+) Sijiju | Sijiju M4E12(1300-) |

| M20E2(700+) Wenzhouju | Wenzhouju M17E2(530-) | |

| NB luowen | M10E7(850-) WZ Luofu; NB luofu; Wenzhouju | WZ Luofu M10E7(320-); NB luofu M2E21(400-), M3E17(450+), M11E21(250+); Wenzhouju M17E2(530-) |

| WZ Luofu | M10E7(320-) NB luofu; Wenzhouju; Shanjingan | NB luofu M2E21(400-), M3E17(450+), M11E21(250+); Wenzhouju M17E2(530-); Shanjingan M1E22(300-) |

| Group markers | Shared genotypes with | Unique markers for discrimination |

|---|---|---|

| M1E23(800-) | NB jindan, WZ luofu, WZ jingdan LY jingan |

NB jindan M1E15(1800-), M3E17(250-) WZ Luofu M10E7(320-) WZ jingdan M2E21(450+), M16E9(350-) LY jingan M7E4(500+) |

| M7E4(1050+) | NB jindan NB luofu WZ jingdan LY jingan |

NB jindan M1E15(1800-), M3E17(250-); NB Luofu M2E21(400-), M3E17(450+), M11E21(250+) WZ jingdan M2E21(450+), M16E9(350-) LY jingan M7E4(500+) |

| Marker types | Genotypes | Markers for discrimination |

|---|---|---|

| Single marker | Guijingan1 | M1E22(740-) |

| HP jingan | M10E7(710-) | |

| FY jingan | M3E17(90-) | |

| Bi/Tri- markers | CM jingan + HP jingan | M2E21(480-) |

| YS jingan + F15-1 | M14E12(760-) | |

| Guijingan2 + YS jingan+ HP jingan | M14E12(700-) | |

| No specific marker | RA jingan |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).