Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Development of an F2 Segregating Population by Self-Pollination of L. angustifolia var. Hemus

2.2. SSR Marker Development

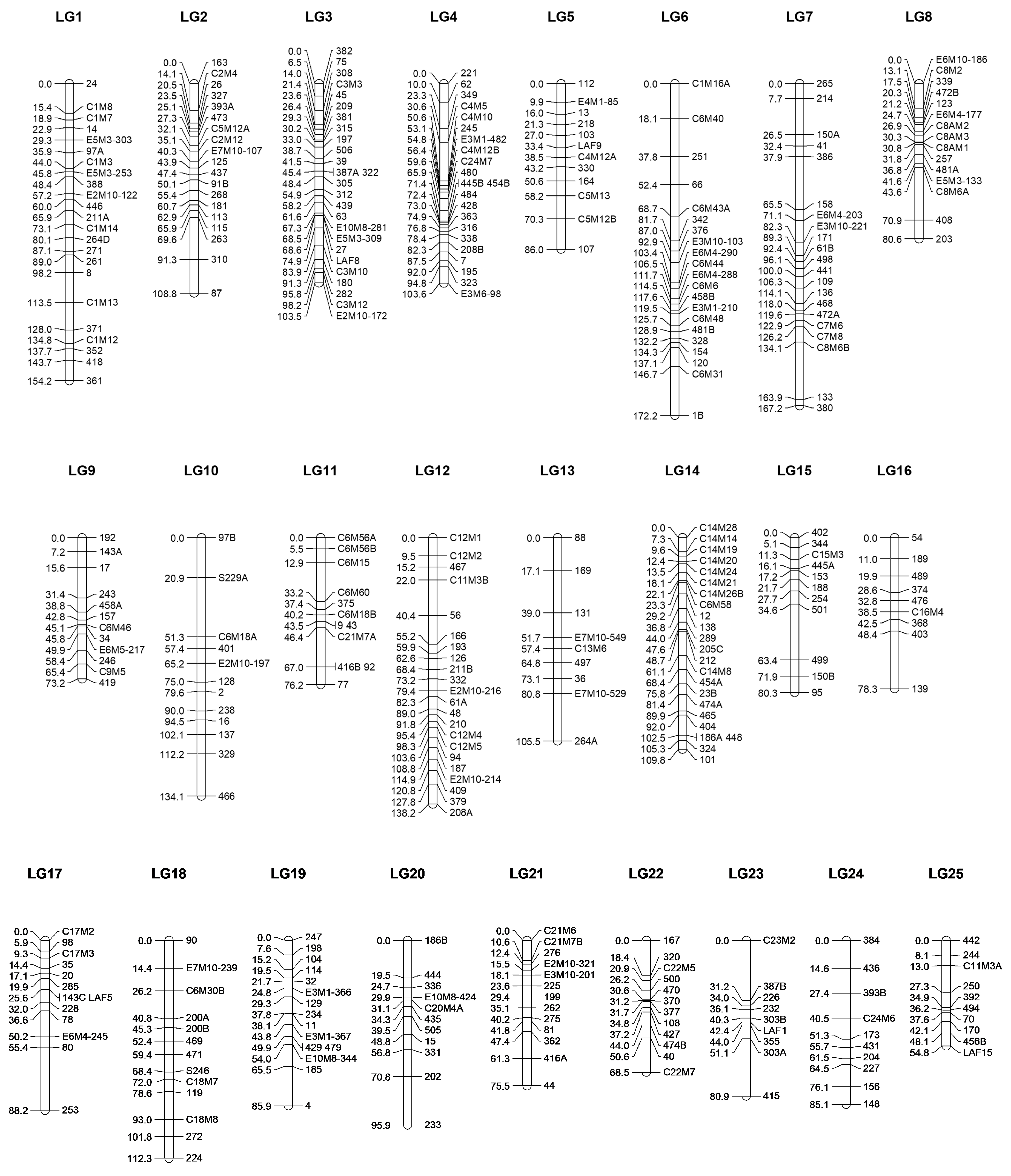

2.3. Linkage Map Construction

2.3. SSR Marker Transferability

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material

3.2. Genomic DNA Isolation

3.3. Next Generation Sequencing, SSR Identification and Primer Design

3.4. SSR Identification after Search of Reference Genome Sequence and Primer Design

3.5. PCR Amplification of SSR Regions

3.6. PCR Amplification of SSR regions with Tailed Primers

3.7. PCR Amplification of SRAP Fragments

3.8. SSR and SRAP Fragment Analysis

3.5. Linkage Analysis and Genetic Map Construction

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cáceres-Cevallos, G. J.; Quílez, M.; Ortiz de Elguea-Culebras, G.; Melero-Bravo, E.; Sánchez-Vioque, R.; Jordán, M. J., Agronomic Evaluation and Chemical Characterization of Lavandula latifolia Medik. under the Semiarid Conditions of the Spanish Southeast. Plants 2023, 12, (10), 1986.

- Gallotte, P.; Fremondière, G.; Gallois, P.; Bernier, J.-P. B.; Buchwalder, A.; Walton, A.; Piasentin, J.; Fopa-Fomeju, B., Lavandula angustifolia Mill. and Lavandula x Intermedia Emeric Ex Loisel: Lavender and Lavandin. In Medicinal, Aromatic and Stimulant Plants, Springer: 2020; pp 303-311.

- Giray, F. H., An analysis of world lavender oil markets and lessons for Turkey. Journal of essential oil bearing plants 2018, 21, (6), 1612-1623. [CrossRef]

- Lis-Balchin, M., Lavender: the genus Lavandula. CRC press: London, UK, 2002.

- Pokajewicz, K.; Czarniecka-Wiera, M.; Krajewska, A.; Maciejczyk, E.; Wieczorek, P. P., Lavandula× intermedia—A Bastard lavender or a plant of many values? Part I. Biology and chemical composition of lavandin. Molecules 2023, 28, (7), 2943.

- Crișan, I.; Ona, A.; Vârban, D.; Muntean, L.; Vârban, R.; Stoie, A.; Mihăiescu, T.; Morea, A., Current trends for lavender (lavandula angustifolia Mill.) crops and products with emphasis on essential oil quality. Plants 2023, 12, (2), 357. [CrossRef]

- Aprotosoaie, A. C.; Gille, E.; Trifan, A.; Luca, V. S.; Miron, A., Essential oils of Lavandula genus: a systematic review of their chemistry. Phytochemistry Reviews 2017, 16, 761-799. [CrossRef]

- Diass, K.; Merzouki, M.; Elfazazi, K.; Azzouzi, H.; Challioui, A.; Azzaoui, K.; Hammouti, B.; Touzani, R.; Depeint, F.; Ayerdi Gotor, A., Essential Oil of Lavandula officinalis: Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activities. Plants 2023, 12, (7), 1571. [CrossRef]

- Malloggi, E.; Menicucci, D.; Cesari, V.; Frumento, S.; Gemignani, A.; Bertoli, A., Lavender aromatherapy: A systematic review from essential oil quality and administration methods to cognitive enhancing effects. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 2022, 14, (2), 663-690. [CrossRef]

- Wells, R.; Truong, F.; Adal, A. M.; Sarker, L. S.; Mahmoud, S. S., Lavandula essential oils: a current review of applications in medicinal, food, and cosmetic industries of lavender. Natural Product Communications 2018, 13, (10), 1934578X1801301038.

- Stanev, S.; Zagorcheva, T.; Atanassov, I., Lavender cultivation in Bulgaria-21 st century developments, breeding challenges and opportunities. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science 2016, 22, (4).

- Détár, E.; Németh, É. Z.; Gosztola, B.; Demján, I.; Pluhár, Z., Effects of variety and growth year on the essential oil properties of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) and lavandin (Lavandula x intermedia Emeric ex Loisel.). Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 2020, 90, 104020. [CrossRef]

- Kiprovski, B.; Zeremski, T.; Varga, A.; Čabarkapa, I.; Filipović, J.; Lončar, B.; Aćimović, M., Essential oil quality of lavender grown outside its native distribution range: A study from Serbia. Horticulturae 2023, 9, (7), 816. [CrossRef]

- Vijulie, I.; Lequeux-Dincă, A.-I.; Preda, M.; Mareci, A.; Matei, E., Could Lavender Farming Go from a Niche Crop to a Suitable Solution for Romanian Small Farms? Land 2022, 11, (5), 662.

- Despinasse, Y.; Moja, S.; Soler, C.; Jullien, F.; Pasquier, B.; Bessière, J.-M.; Baudino, S.; Nicolè, F., Structure of the chemical and genetic diversity of the true lavender over its natural range. Plants 2020, 9, (12), 1640. [CrossRef]

- Dobreva, A.; Petkova, N.; Todorova, M.; Gerdzhikova, M.; Zherkova, Z.; Grozeva, N., Organic vs. Conventional Farming of Lavender: Effect on Yield, Phytochemicals and Essential Oil Composition. Agronomy 2023, 14, (1), 32. [CrossRef]

- Jug-Dujaković, M.; Ninčević Runjić, T.; Grdiša, M.; Liber, Z.; Šatović, Z., Intra-and Inter-Cultivar Variability of Lavandin (Lavandula× intermedia Emeric ex Loisel.) Landraces from the Island of Hvar, Croatia. Agronomy 2022, 12, (8), 1864.

- Perović, A. B.; Karabegović, I. T.; Krstić, M. S.; Veličković, A. V.; Avramović, J. M.; Danilović, B. R.; Veljković, V. B., Novel hydrodistillation and steam distillation methods of essential oil recovery from lavender: A comprehensive review. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 211, 118244. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Sultan, P.; Qazi, P.; Rasool, S., Approaches for the genetic improvement of Lavender: A short review. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2019, 8, (2), 736-740.

- Sharan, H.; Pandey, P.; Singh, S., Genetic Resources and Breeding Strategies for Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.). In Ethnopharmacology and OMICS Advances in Medicinal Plants Volume 2: Revealing the Secrets of Medicinal Plants, Nandave, M.; Joshi, R.; Upadhyay, J., Eds. Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp 33-54.

- Adal, A. M.; Mahmoud, S. S., Short-chain isoprenyl diphosphate synthases of lavender (Lavandula). Plant molecular biology 2020, 102, 517-535. [CrossRef]

- Adal, A. M.; Najafianashrafi, E.; Sarker, L. S.; Mahmoud, S. S., Cloning, functional characterization and evaluating potential in metabolic engineering for lavender (+)-bornyl diphosphate synthase. Plant Molecular Biology 2023, 111, (1), 117-130. [CrossRef]

- Adal, A. M.; Sarker, L. S.; Malli, R. P.; Liang, P.; Mahmoud, S. S., RNA-Seq in the discovery of a sparsely expressed scent-determining monoterpene synthase in lavender (Lavandula). Planta 2019, 249, 271-290. [CrossRef]

- Demissie, Z. A.; Sarker, L. S.; Mahmoud, S. S., Cloning and functional characterization of β-phellandrene synthase from Lavandula angustifolia. Planta 2011, 233, 685-696. [CrossRef]

- Despinasse, Y.; Fiorucci, S.; Antonczak, S.; Moja, S.; Bony, A.; Nicolè, F.; Baudino, S.; Magnard, J.-L.; Jullien, F., Bornyl-diphosphate synthase from Lavandula angustifolia: a major monoterpene synthase involved in essential oil quality. Phytochemistry 2017, 137, 24-33. [CrossRef]

- Guitton, Y.; Nicolè, F.; Moja, S.; Valot, N.; Legrand, S.; Jullien, F.; Legendre, L., Differential accumulation of volatile terpene and terpene synthase mRNAs during lavender (Lavandula angustifolia and L. x intermedia) inflorescence development. Physiologia plantarum 2010, 138, (2), 150-163.

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Bai, H.; Li, H.; Shi, L., The transcription factor LaMYC4 from lavender regulates volatile Terpenoid biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biology 2022, 22, (1), 289. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, L. S.; Adal, A. M.; Mahmoud, S. S., Diverse transcription factors control monoterpene synthase expression in lavender (Lavandula). Planta 2020, 251, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Zhang, X.; Mu, H.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Wen, Y.; Ma, Q.; Guo, S., Transcriptome analysis unravels differential genes involved in essential oil content in callus and tissue culture seedlings of Lavandula angustifolia. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2024, 38, (1), 2367097. [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Kang, K.; Wang, P.; Li, M.; Huang, X., Transcriptome profiling of spike provides expression features of genes related to terpene biosynthesis in lavender. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, (1), 6933. [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.; Boecklemann, A.; Woronuk, G. N.; Sarker, L.; Mahmoud, S. S., A genomics resource for investigating regulation of essential oil production in Lavandula angustifolia. Planta 2010, 231, 835-845. [CrossRef]

- Kelimujiang, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Waili, A.; Tang, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L., Genome-wide investigation of WRKY gene family in Lavandula angustifolia and potential role of LaWRKY57 and LaWRKY75 in the regulation of terpenoid biosynthesis. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1449299. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Dong, Y.; Hao, H.; Ling, Z.; Bai, H.; Wang, H.; Cui, H.; Shi, L., Time-series transcriptome provides insights into the gene regulation network involved in the volatile terpenoid metabolism during the flower development of lavender. BMC plant biology 2019, 19, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Dong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Bai, H.; Li, H.; Shi, L., Genome-wide identification and expression of BAHD acyltransferase gene family shed novel insights into the regulation of linalyl acetate and lavandulyl acetate in lavender. Journal of Plant Physiology 2024, 292, 154143. [CrossRef]

- Malli, R. P.; Adal, A. M.; Sarker, L. S.; Liang, P.; Mahmoud, S. S., De novo sequencing of the Lavandula angustifolia genome reveals highly duplicated and optimized features for essential oil production. Planta 2019, 249, 251-256. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, D.; Bai, H.; Li, K.; Li, H.; Shi, L., The chromosome-based lavender genome provides new insights into Lamiaceae evolution and terpenoid biosynthesis. Horticulture research 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J. P.; Vaillancourt, B.; Wood, J. C.; Wang, H.; Jiang, J.; Soltis, D. E.; Buell, C. R.; Soltis, P. S., Chromosome-scale genome assembly of the ’Munstead’ cultivar of Lavandula angustifolia. BMC Genom Data 2023, 24, (1), 75.

- Fontez, M.; Bony, A.; Nicole, F.; Moja, S.; Jullien, F., Lavandula angustifolia Mill. a model of aromatic and medicinal plant to study volatile organic compounds synthesis, evolution and ecological functions. Botany Letters 2023, 170, (1), 65-76. [CrossRef]

- Guitton, Y.; Nicolè, F.; Moja, S.; Benabdelkader, T.; Valot, N.; Legrand, S.; Jullien, F.; Legendre, L., Lavender inflorescence: a model to study regulation of terpenes synthesis. Plant signaling & behavior 2010, 5, (6), 749-751.

- Habán, M.; Korczyk-Szabó, J.; Čerteková, S.; Ražná, K., Lavandula Species, Their Bioactive Phytochemicals, and Their Biosynthetic Regulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, (10), 8831.

- Adal, A. M.; Demissie, Z. A.; Mahmoud, S. S., Identification, validation and cross-species transferability of novel Lavandula EST-SSRs. Planta 2015, 241, 987-1004. [CrossRef]

- Zagorcheva, T.; Stanev, S.; Rusanov, K.; Atanassov, I., SRAP markers for genetic diversity assessment of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia mill.) varieties and breeding lines. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2020, 34, (1), 303-308.

- Ražná, K.; Čerteková, S.; Štefúnová, V.; Habán, M.; Korczyk-Szabó, J.; Ernstová, M., Lavandula spp. diversity assessment by molecular markers as a tool for growers. Agrobiodiversity for Improving Nutrition, Health and Life Quality 2023, 7, (1). [CrossRef]

- Chahota, R. K.; Katoch, M.; Sharma, P. K.; Thakur, S. R., QTLs and Gene Tagging in Crop Plants. In Agricultural Biotechnology: Latest Research and Trends, Kumar Srivastava, D.; Kumar Thakur, A.; Kumar, P., Eds. Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2021; pp 537-552.

- Chaturvedi, T.; Gupta, A. K.; Lal, R. K.; Tiwari, G., March of molecular breeding techniques in the genetic enhancement of herbal medicinal plants: present and future prospects. The Nucleus 2022, 65, (3), 413-436. [CrossRef]

- Stanev, S., Evaluation of the stability and adaptability of the Bulgarian lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) sorts yield. Agricultural Science and Technolog 2010, 2(3), 121–123.

- Valchev, H.; Kolev, Z.; Stoykova, B.; Kozuharova, E., Pollinators of Lavandula angustifolia Mill., an important factor for optimal production of lavender essential oil. BioRisk 2022, 17, 297-307. [CrossRef]

- Alekseeva, M. E.; Rusanova, M. G.; Georgieva, L. N.; Rusanov, K. E.; Atanassov, I. I., High cross-pollination rate of Greek oregano (O. vulgare ssp. hirtum) with Common oregano (O. vulgare ssp. vulgare) under open field conditions as revealed by microsatellite marker analysis. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2023, 37, (1), 2279636.

- Valchev, H.; Kozuharova, E. In In situ and ex situ investigations on breeding systems and pollination of Sideritis scardica Griseb.(Lamiaceae) in Bulgaria, Proceedings of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 2022; pp 527-535.

- Alekseeva, M.; Rusanova, M.; Rusanov, K.; Atanassov, I., A set of highly polymorphic microsatellite markers for genetic diversity studies in the genus Origanum. Plants 2023, 12, (4), 824. [CrossRef]

- Manco, R.; Chiaiese, P.; Basile, B.; Corrado, G., Comparative analysis of genomic-and EST-SSRs in European plum (Prunus domestica L.): Implications for the diversity analysis of polyploids. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 1-9.

- Garavello, M.; Cuenca, J.; Dreissig, S.; Fuchs, J.; Navarro, L.; Houben, A.; Aleza, P., Analysis of crossover events and allele segregation distortion in interspecific citrus hybrids by single pollen genotyping. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11, 615. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Gao, W.; Liu, L.; Liu, M.; Zhao, N.; Han, M.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, W.; Gao, Z.; Hu, Y., Identification of QTL for resistance to root rot in sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam) with SSR linkage maps. BMC genomics 2020, 21, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Baurens, F. C.; Hervouet, C.; Salmon, F.; Delos, J. M.; Labadie, K.; Perdereau, A.; Mournet, P.; Blois, L.; Dupouy, M., Chromosome reciprocal translocations have accompanied subspecies evolution in bananas. The Plant Journal 2020, 104, (6), 1698-1711. [CrossRef]

- Mittelsten Scheid, O., Mendelian and non-Mendelian genetics in model plants. The Plant Cell 2022, 34, (7), 2455-2461. [CrossRef]

- Yoosefzadeh Najafabadi, M.; Hesami, M.; Rajcan, I., Unveiling the mysteries of non-mendelian heredity in plant breeding. Plants 2023, 12, (10), 1956. [CrossRef]

- Canaguier, A.; Grimplet, J.; Di Gaspero, G.; Scalabrin, S.; Duchêne, E.; Choisne, N.; Mohellibi, N.; Guichard, C.; Rombauts, S.; Le Clainche, I., A new version of the grapevine reference genome assembly (12X. v2) and of its annotation (VCost. v3). Genomics data 2017, 14, 56. [CrossRef]

- Howe, K.; Chow, W.; Collins, J.; Pelan, S.; Pointon, D.-L.; Sims, Y.; Torrance, J.; Tracey, A.; Wood, J., Significantly improving the quality of genome assemblies through curation. GigaScience 2021, 10, (1), giaa153. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, G.; Yang, S.; Just, J.; Yan, H.; Zhou, N.; Jian, H.; Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, H.; Dong, X.; Jiang, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, M.; Bendahmane, M.; Ning, G.; Ge, H.; Hu, J.-Y.; Tang, K., The development of a high-density genetic map significantly improves the quality of reference genome assemblies for rose. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, (1), 5985. [CrossRef]

- Rusanov, K.; Vassileva, P.; Rusanova, M.; Atanassov, I., Identification of QTL controlling the ratio of linalool to linalyl acetate in the flowers of Lavandula angustifolia Mill var. Hemus. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2023, 37, (1), 2288929. [CrossRef]

- Anilkumar, C.; Sunitha, N.; Harikrishna; Devate, N. B.; Ramesh, S., Advances in integrated genomic selection for rapid genetic gain in crop improvement: a review. Planta 2022, 256, (5), 87. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Bernard, A.; Wang, Y.; Dirlewanger, E.; Wang, X., Genomes and integrative genomic insights into the genetic architecture of main agronomic traits in the edible cherries. Horticulture Research 2025, 12, (1), uhae269. [CrossRef]

- Vervalle, J. A.; Costantini, L.; Lorenzi, S.; Pindo, M.; Mora, R.; Bolognesi, G.; Marini, M.; Lashbrooke, J. G.; Tobutt, K. R.; Vivier, M. A., A high-density integrated map for grapevine based on three mapping populations genotyped by the Vitis 18K SNP chip. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2022, 135, (12), 4371-4390. [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.; Thompson, W., Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic acids research 1980, 8, (19), 4321-4326. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S., FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics. babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Edgar, R. C., Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, (19), 2460-2461. [CrossRef]

- Benson, G., Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic acids research 1999, 27, (2), 573-580. [CrossRef]

- Koressaar, T.; Remm, M., Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, (10), 1289-1291. [CrossRef]

- Untergasser, A.; Cutcutache, I.; Koressaar, T.; Ye, J.; Faircloth, B. C.; Remm, M.; Rozen, S. G., Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic acids research 2012, 40, (15), e115-e115.

- O’Leary, N. A.; Cox, E.; Holmes, J. B.; Anderson, W. R.; Falk, R.; Hem, V.; Tsuchiya, M. T.; Schuler, G. D.; Zhang, X.; Torcivia, J., Exploring and retrieving sequence and metadata for species across the tree of life with NCBI Datasets. Scientific data 2024, 11, (1), 732. [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yue, B., Krait: an ultrafast tool for genome-wide survey of microsatellites and primer design. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, (4), 681-683. [CrossRef]

- Blacket, M.; Robin, C.; Good, R.; Lee, S.; Miller, A., Universal primers for fluorescent labelling of PCR fragments—an efficient and cost-effective approach to genotyping by fluorescence. Molecular ecology resources 2012, 12, (3), 456-463. [CrossRef]

- Schuelke, M., An economic method for the fluorescent labeling of PCR fragments. Nature biotechnology 2000, 18, (2), 233-234. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Quiros, C. F., Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP), a new marker system based on a simple PCR reaction: its application to mapping and gene tagging in Brassica. Theoretical and applied genetics 2001, 103, 455-461. [CrossRef]

- Ooijen, V., JoinMap® 5, Software for the calculation of genetic linkage maps in experimental populations of diploid species. Kyazma BV, Wageningen, Netherlands. 2018.

- Voorrips, R. E., MapChart: Software for the Graphical Presentation of Linkage Maps and QTLs. Journal of Heredity 2002, 93, (1), 77-78.

| Type of the tested markers | total number of tested markers |

markers showing positive amplification and distinct pattern (% from the total number of tested markers) |

number of polymorphic markers (% from the total number of tested markers) [% from the markers with positive amplification] |

total number of loci identified (average number of detected loci per marker) |

| NGS-SSR | 471 | 442 (93,8%) | 255 (54,1%) [57,7%] | 282 (1,11) |

| GEN-SSR | 170 | 154 (90,6%) | 79 (46,5%) [51,3%] | 90 (1,14) |

| EST-SSR | 22 | 17 (77,3%) | 5 (22,7%) [29,4%] | 5 (1,0) |

| SRAP | 11 | 11 (100%) | 11 (100%) [100%] | 33 (3,0) |

| Total for the SSR markers | 663 | 613 | 339 | 377 |

| Linkage group | Number of loci * | Map length (cM) |

Map density (loci/cM) |

Largest gap (cM) |

Chromosome sequence (Mbp) |

Foremost position of the loci (Mbp) | Rearmost position of the loci (Mbp) |

Coverage of the chromosome (%) |

| LG1 | 23 | 154,23 | 6,71 | 15,37 | 43,13 | 1,64 | 40,38 | 89,8% |

| LG2 | 19 | 108,82 | 5,73 | 21,70 | 40,25 | 1,08 | 39,51 | 95,5% |

| LG3 | 26 | 103,45 | 3,98 | 9,04 | 39,13 | 1,54 | 39,09 | 96,0% |

| LG4 | 22 | 103,61 | 4,71 | 20,09 | 37,48 | 0,30 | 34,65 | 91,6% |

| LG5 | 12 | 86,01 | 7,17 | 15,69 | 35,70 | 1,86 | 35,64 | 94,6% |

| LG6 | 21 | 172,22 | 7,83 | 19,73 | 35,32 | 0,08 | 35,18 | 99,4% |

| LG7 | 21 | 167,25 | 7,96 | 29,71 | 34,57 | 0,05 | 34,21 | 98,8% |

| LG8 | 15 | 80,61 | 5,37 | 27,30 | 33,58 | 1,31 | 33,47 | 95,8% |

| LG9 | 12 | 73,22 | 6,10 | 15,83 | 33,03 | 10,06 | 30,87 | 63,0% |

| LG10 | 12 | 134,11 | 11,18 | 30,40 | 32,61 | 0,14 | 32,21 | 98,3% |

| LG11 | 12 | 76,24 | 6,35 | 20,61 | 31,76 | 0,78 | 31,00 | 95,2% |

| LG12 | 22 | 138,18 | 6,28 | 18,39 | 31,37 | 0,02 | 26,38 | 84,0% |

| LG13 | 9 | 105,47 | 11,72 | 24,66 | 30,09 | 7,42 | 26,93 | 64,8% |

| LG14 | 23 | 109,78 | 4,77 | 12,39 | 29,44 | 0,25 | 28,75 | 96,8% |

| LG15 | 11 | 80,33 | 7,30 | 28,86 | 28,69 | 1,16 | 27,98 | 93,5% |

| LG16 | 9 | 78,26 | 8,70 | 29,88 | 28,47 | 1,04 | 15,06 | 49,2% |

| LG17 | 13 | 88,16 | 6,78 | 32,75 | 27,94 | 2,54 | 26,43 | 85,5% |

| LG18 | 13 | 112,34 | 8,64 | 14,61 | 27,54 | 2,61 | 27,51 | 90,4% |

| LG19 | 15 | 85,91 | 5,73 | 20,46 | 27,40 | 0,11 | 19,59 | 71,1% |

| LG20 | 11 | 95,90 | 8,72 | 25,05 | 27,08 | 4,13 | 26,87 | 84,0% |

| LG21 | 13 | 75,46 | 5,80 | 14,19 | 27,05 | 5,20 | 26,54 | 78,9% |

| LG22 | 12 | 68,54 | 5,71 | 18,39 | 26,81 | 0,59 | 25,15 | 91,6% |

| LG23 | 9 | 80,88 | 8,99 | 31,23 | 26,63 | 8,33 | 25,49 | 64,4% |

| LG24 | 10 | 85,09 | 8,51 | 14,63 | 23,28 | 1,45 | 17,98 | 71,0% |

| LG25 | 10 | 54,84 | 5,48 | 14,24 | 22,94 | 1,37 | 16,55 | 66,2% |

| Minimal value for LG | 9 | 54,84 | 3,98 | 49,2% | ||||

| Maximal value for LG | 26 | 172,22 | 11,72 | 99,4% | ||||

| Average value per LG | 15,00 +/- 5,33 |

100,75 +/- 30,93 |

7,05 +/- 1,92 |

84,4% +/- 14,2% |

||||

| Total value for the map | 375 | 2518,91 | 6,72 |

| PCR amplification (*) | Results of SSR amplification from DNA of the tested plants** | |||

|

L. angustifolia var. Hidcote Blue |

L. latifolia Ll_abi2 |

L. latifolia Bastin Nursery |

L. × heterophylla var. Big Boy James | |

| (+) | 291 | 243 | 172 | 251 |

| 93,9% | 78,4% | 78,5% | 81,0% | |

| (w) | 10 | 15 | 7 | 10 |

| 3,2% | 4,8% | 3,2% | 3,2% | |

| (-) | 9 | 52 | 40 | 49 |

| 2,9% | 16,8% | 18,3% | 15,8% | |

| Total number tested SSRs | 310 | 310 | 219 | 310 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).