Submitted:

15 January 2026

Posted:

16 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

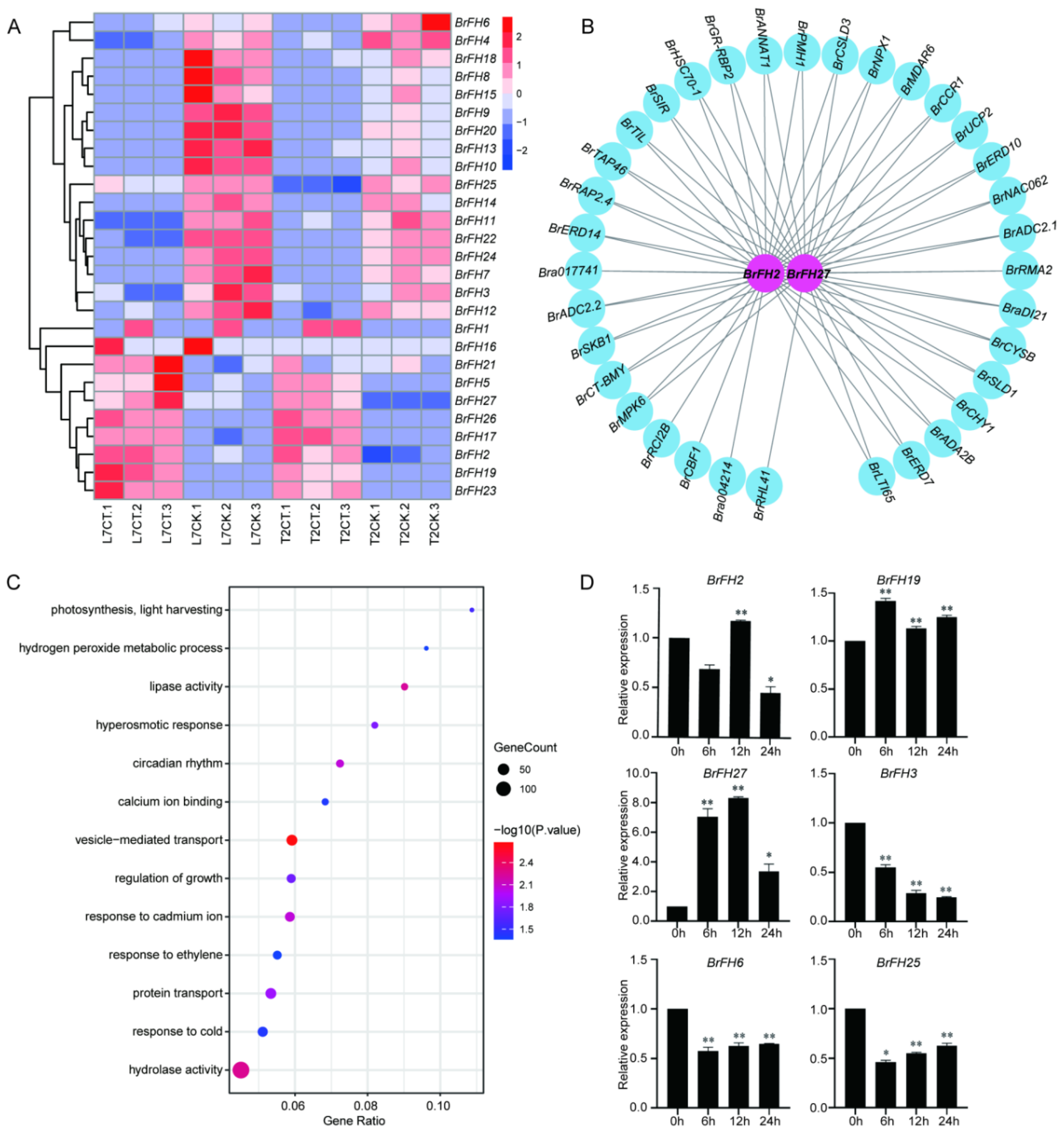

Background: Formin proteins are crucial regulators of actin filament assembly and elongation in eukaryotic cells, playing important roles in plant development and abiotic stress responses. However, the functional characterization of formins in Brassica rapa remains uncover. Methods: A total of 27 formin family members (BrFHs) were identified through genome-wide alignment with Arabidopsis thaliana. Results: Phylogenetic analysis classified BrFH gene family into two distinct clades, designated Group I and Group II, which exhibit divergent protein architectures. Promoter analysis revealed that BrFHs contain multiple cis-regulatory elements related to growth and development, stress responses, and phytohormone signaling. These findings suggest that BrFHs may have diversified functions. Tissue-specific expression analysis revealed that BrFHs exhibit distinct expression patterns across various tissues. Notably, BrFH15 and BrFH18 are highly expressed in flowers, displaying expression profiles similar to those of floral development genes such as AP3, AGL10 and so on. Additionally, many BrFHs show dynamic expression patterns in response to cold stresses. In particular, BrFH2, BrFH19 and BrFH27 were up-regulated, and their co-expression within the gene network suggests potential roles in regulating cold stress. Conclusions: These results clarify the functional roles of BrFHs and shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying their regulation of tissue development and responses to abiotic stress in Brassica rapa.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of FH Genes in the B. rapa Genome and Subcellular Localization Analysis

2.2. Chromosomal Localization, Synteny, and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.3. Motif and Conserved Domain, and Protein Structure Analysis

2.4. Cis-Acting Element Analysis

2.5. Expression Profiling of BrFH Genes in Different Tissues and Under Low-Temperature Stress

2.6. Co-Expression Network Analysis

2.7. Gene Ontology (GO) Enrichment Analysis

2.8. qRT-PCR Analysis

2.9. Ka/Ks Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of FH Family Genes

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis and Classification of FH Family Genes

3.3. Analysis of Evolutionary Relationship, Gene Structure, and Conservative Motif of FH Family Genes

3.4. Cis-Acting Element Analysis of FH Family Genes

3.5. Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns of FH Family Genes

3.6. Transcriptome Analysis of BrFHs in Response to Cold Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Competing interests

References

- Higgs, H.N.; Peterson, K. J. Phylogenetic analysis of the formin homology 2 domain. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Faix, J.; Grosse, R. Staying in shape with formins. Dev. Cell 2006, 10, 693-706. [CrossRef]

- Higgs, H.N. Formin proteins: a domain-based approach. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005, 30, 342-353. [CrossRef]

- Sagot, I.; Rodal, A.A.; Moseley, J.; Goode, B.L.; Pellman, D. An actin nucleation mechanism mediated by Bni1 and profilin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002, 4, 626-631. [CrossRef]

- Courtemanche, N.; Pollard, T.D. Determinants of Formin Homology 1 (FH1) domain function in actin filament elongation by formins. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 7812-7820. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Moseley, J. B.; Sagot, I.; Poy, F.; Pellman, D.; Goode, B. L.; Eck, M. J. Crystal structures of a Formin Homology-2 domain reveal a tethered dimer architecture. Cell 2004, 116, 711-723. [CrossRef]

- Zweifel, M.E.; Courtemanche, N. Profilin’s Affinity for Formin Regulates the Availability of Filament Ends for Actin Monomer Binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, R. Actin filament nucleation and elongation factors--structure-function relationships. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009, 44, 351-366. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhu, Q.; Pin, C.K.; Alma, T.; Xu, L.; Gao, Y.G.; Mu, Y.; Hou, X.; Miao, Y. Profilin negatively regulates formin-mediated actin assembly to modulate pamp-triggered plant immunity. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 1882-1895.

- Khuman, A.; Yadav, V.; Chaudhary, B. Evolutionary dynamics of the cytoskeletal profilin gene family in Brassica juncea L. reveal its roles in silique development and stress resilience. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131247. [CrossRef]

- Cvrcková, F.; Novotný, M.; Pícková, D; Zárský, V. Formin homology 2 domains occur in multiple contexts in angiosperms. BMC Genomics 2004, 5. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mao, T. Understanding the functions and mechanisms of plant cytoskeleton in response to environmental signals. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2019, 52, 86-96. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Staiger, C.J. Understanding Cytoskeletal Dynamics During the Plant Immune Response. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018, 56, 513-533. [CrossRef]

- Porter, K.; Day, B. From filaments to function: The role of the plant actin cytoskeleton in pathogen perception, signaling and immunity. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2016, 58, 299-311. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.Y.; Wu, H.M. Overexpression of an Arabidopsis formin stimulates supernumerary actin cable formation from pollen tube cell membrane. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 257-269. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Du, Z.; Jiang, N.; He, S.; Shi, Y.; Xiao, K.; Xu, L.; Wang, K.; Wu, L; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Profiling of the FORMIN Gene Family Implies Their Potential Functions in Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Rice (Oryza sativa). Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 41, 573-586. [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K.; Islam, M.S.U.; Akter, N.; Zohra, F.T.; Rashid, S.B.; Ahmed, M.S.; Rahman, S.M.; Sarkar, M.A.R. Genome-wide identification and characterization of FORMIN gene family in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) and their expression profiles in response to multiple abiotic stress treatments. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0319176. [CrossRef]

- Deeks, M.J.; Hussey, P.J.; Davies, B. Formins: intermediates in signal-transduction cascades that affect cytoskeletal reorganization. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 492-498. [CrossRef]

- Bouain, N.; Korte, A.; Satbhai, S. B.; Nam, H. I.; Rhee, S. Y.; Busch, W.; Rouached, H. Systems genomics approaches provide new insights into Arabidopsis thaliana root growth regulation under combinatorial mineral nutrient limitation. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15. [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, G.V.; Krutovsky, K.V. Mechanical stress effects on transcriptional regulation of genes encoding microtubule- and actin-associated proteins. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2022, 28, 17-30. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.Y.; Niroomand, S.; Zou, Y; Wu, H.M. A transmembrane formin nucleates subapical actin assembly and controls tip-focused growth in pollen tubes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 16390-16395. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Jin, C.; Qu, H.Y.; Tao, S.T.; Xu, G.H.; Wu, G.H.; Wu, J.; Wu, H.Q.; Zhang, S.L. Low temperature inhibits pollen viability by alteration of actin cytoskeleton and regulation of pollen plasma membrane ion channels in Pyrus pyrifolia. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 78, 70-75. [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Li, T.; Chen, S.; Wan, D.; He, Y.; Zheng, C.; Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, J.; et al. Evolution of the thermostability of actin-depolymerizing factors enhances the adaptation of pollen germination to high temperature. Plant cell 2023, 36, 881-898. [CrossRef]

- Deeks, M.J.; Cvrcková, F.; Machesky, L.M.; Mikitová, V.; Ketelaar, T.; Zársky, V.; Davies, B.; Hussey, P.J. Arabidopsis group Ie formins localize to specific cell membrane domains, interact with actin-binding proteins and cause defects in cell expansion upon aberrant expression. New Phytol. 2005, 168, 529-540. [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.; Guo, C.; Chen, D.; Zhao, B.; Yang, B.; Ren, H. Cloning and functional characterization of a formin-like protein (AtFH8) from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 1071-1082. [CrossRef]

- Blanchoin, L.; Boujemaa-Paterski, R.; Henty, J.L.; Khurana, P.; Staiger, C.J. Actin dynamics in plant cells: a team effort from multiple proteins orchestrates this very fast-paced game. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 714-723. [CrossRef]

- Cvrčková, F.; Grunt, M.; Žárský, V. Expression of GFP-mTalin reveals an actin-related role for the Arabidopsis Class II formin AtFH12. Biol. Plant. 2012, 56, 431-440. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Cai, C.; Zhong, C.; Zhu, L.; Yuan, M.; Ren, H. The type II Arabidopsis formin14 interacts with microtubules and microfilaments to regulate cell division. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2710-2726. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Meng, L.; Ren, H. AtFH16, an Arabidopsis type II formin, binds and bundles both microfilaments and microtubules, and preferentially binds to microtubules. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2013, 55, 1002-1015. [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Schmitz, C.; Lace, B.; Ditengou, F.A.; Su, C.; Schulze, E.; Knerr, J.; Grosse, R.; Keller, J.; Libourel, C.; Delaux, P.M.; Ott, T. Formin-mediated bridging of cell wall, plasma membrane, and cytoskeleton in symbiotic infections of Medicago truncatula. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 2712-2719.e5. [CrossRef]

- Shing, P.; Islam, M.S.U.; Khatun, M.S.; Zohra, F.T.; Hasan, N.; Rahman, S.M.; Sarkar, M.A.R. Genome-wide identification, characterization and expression profiles of FORMIN gene family in cotton (Gossypium Raimondii L.). BMC Genom. Data 2024, 25, 105. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Shan, M.; Amjad, Z.; Xue, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y. Genome-Wide Studies of FH Family Members in Soybean (Glycine max) and Their Responses under Abiotic Stresses. Plants (Basel) 2024, 13, 276. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Q.; Bai, L.; Zhang, T.; Huang, S.; Song, C.; Yuan, M.; Guo, Y. Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate regulates SCAB1-mediated F-actin reorganization during stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. Plant cell 2021, 34, 477-494. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lim, Y.P.; Han, C.T.; Nou, I.S.; Hur, Y. Genome-wide expression profiles of contrasting inbred lines of Chinese cabbage, Chiifu and Kenshin, under temperature stress. Genes Genom. 2013, 35, 273-288. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Guo, X.; Wu J.; Liang, J.; Lin, R.; Yan, Z.; Wang, X. An optimized protocol for detecting guard cell specific gene expression by in situ RT-PCR in Brassica rapa. Hortic. Plant. 2022, 8, 311-318. [CrossRef]

- Artimo, P.; Jonnalagedda, M.; Arnold, K.; Baratin, D.; Csardi, G.; de Castro, E.; Duvaud, S.; Flegel, V.; Fortier, A.; Gasteiger, E.; et al. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W597-603. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Dunbrack, R.L., Jr. Assignment of protein sequences to existing domain and family classification systems: Pfam and the PDB. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2763-2772. [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W585-587. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol Plant. 2020, 13, 1194-1202. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.H.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547-1549. [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293-w296. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Williams, N.; Misleh, C.; Li, W.W. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W369-373. [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Geer, L.Y.; Geer, R.C.; He, J.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; et al. CDD: NCBI’s conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D222-226. [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O; Willmore, L; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493-50. [CrossRef]

- Rosignoli, S; Paiardini, A. Boosting the Full Potential of PyMOL with Structural Biology Plugins. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1764. [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325-327. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Thornton, M.; Kim, D. Rapid and accurate alignment of nucleotide conversion sequencing reads with HISAT-3N. Genome. Res. 2021, 31, 1290--1295. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatic 2014, 30, 923-930. [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 559. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498-2504. [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol Biol Evol. 2021, 38, 5825-5829. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics 2012, 16, 284-287. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K. J.; Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [CrossRef]

- Zhang. Z. KaKs_Calculator 3.0: Calculating Selective Pressure on Coding and Non-coding Sequences. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2022, 20(3):536-540. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cenalmor, P., Martínez, A.E., Moneo-Corcuera, D., González-Jiménez, P., Pérez-Sala, D. Oxidative stress elicits the remodeling of vimentin filaments into biomolecular condensates. Redox Biol. 2024, 75, 103282. [CrossRef]

- Schwertassek, U., Haque, A., Krishnan, N., Greiner, R., Weingarten, L., Dick, T.P., Tonks, N.K. Reactivation of oxidized PTP1B and PTEN by thioredoxin 1. FEBS J. 2014 281(16):3545-58. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N., Hu, C.M., Khan, W.A., Wang, W., Ke, H., Huijie, D., Zhishuo, Z., Hou, X, Genome-wide Identification, Classification, and Expression Pattern of Homeobox Gene Family in Brassica rapa under Various Stresses. Sci Rep. 2018, 8(1):16265. [CrossRef]

- Kopeć, P., Rapacz, M., Arora, R., Post-translational activation of CBF for inducing freezing tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27(5):415-417. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Zhao, H., Chen, Y., Jiang, F., Zhou, F., Liu, Q., Fan, Y., Liu, T., Tu, W., Walther, D., Song, B. Comparative transcriptomics analysis reveals a calcineurin B-like gene to positively regulate constitutive and acclimated freezing tolerance in potato. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45(11):3305-3321. [CrossRef]

- Sun, R. Economic/Academic Importance of Brassica rapa. The Brassica rapa Genome, Compendium of Plant Genomes, 2015.

- Pruyne, D.; Evangelista, M.; Yang, C.; Bi, E.; Zigmond, S.; Bretscher, A; Boone, C. Role of Formins in Actin Assembly: Nucleation and Barbed-End Association. Science 2002, 297, 612-615. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Zhou, C. Genome-Wide Characterization and Analysis of the FH Gene Family in Medicago truncatula Under Abiotic Stresses. Genes (Basel). 2025, 16(5):555. [CrossRef]

- Oudelaar, A.M., Higgs, D.R. The relationship between genome structure and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2021, 22(3):154-168. [CrossRef]

- Lata, C., Prasad, M. Role of DREBs in regulation of abiotic stress responses in plants. J Exp Bot. 2011, 62(14):4731-48. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R., Linardopoulou, E.V., Osborn, G.E., Parkhurst, S.M. Formins in development: orchestrating body plan origami. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010, 1803(2):207-25. [CrossRef]

- Faix, J., Grosse, R. Staying in shape with formins. Dev Cell. 2006,10(6):693-706. [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.H., Ahn, M.A., Kim, E., Lee, H.J., Lee, J.H., Wi, S.H., Kim, S.K., Lim, H.B., Hyun, T.K. Plant Response to Cold Stress: Cold Stress Changes Antioxidant Metabolism in Heading Type Kimchi Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. Pekinensis). Antioxidants (Basel). 2022, 11(4):700. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Yang, Y.; Meng, Y. Functional Differentiation of the Duplicated Gene BrrCIPK9 in Turnip (Brassica rapa var. rapa). Genes, 2024, 15, 405. [CrossRef]

| Gene ID | Gene Name | Chr. No | Gene Start Position |

Gene End Position |

A.thaliana ID | A.thaliana Name | Subcellular Localization |

Amino Acid (aa) | CDS (bp) | MW (kDa) | Isoelectric Point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bra039561 | BrFH1 | A01 | 11,886,057 | 11,889,150 | AT5G54650 | AtFH5 | Plasma membrane | 837 | 2,514 | 92.22 | 9.44 |

| Bra035415 | BrFH2 | A01 | 16,477,720 | 16,479,274 | AT1G59910 | AtFH7 | Plasma membrane | 490 | 1,473 | 53.40 | 7.07 |

| Bra028684 | BrFH3 | A02 | 2,564,374 | 2,571,652 | AT5G07770 | AtFH16 | Nucleus | 1627 | 4,884 | 175.30 | 7.39 |

| Bra031838 | BrFH4 | A02 | 27,611,349 | 27,613,482 | AT5G67470 | AtFH6 | Cytoplasm | 440 | 1,323 | 49.71 | 6.02 |

| Bra020385 | BrFH5 | A02 | 6,491,606 | 6,497,627 | AT5G58160 | AtFH13 | Chloroplast | 1396 | 4,191 | 155.28 | 8.30 |

| Bra000328 | BrFH6 | A03 | 10,561,399 | 10,564,306 | AT2G43800 | AtFH2 | Plasma membrane | 895 | 2,688 | 98.20 | 8.47 |

| Bra005952 | BrFH7 | A03 | 1,373,493 | 1,380,081 | AT5G07770 | AtFH16 | Nucleus | 1480 | 4,443 | 160.67 | 6.85 |

| Bra001148 | BrFH8 | A03 | 14,976,355 | 14,979,096 | AT3G05470 | AtFH11 | Plasma membrane | 823 | 2,472 | 91.02 | 8.82 |

| Bra001256 | BrFH9 | A03 | 15,545,258 | 15,546,720 | AT3G07540 | AtFH10 | Cytoplasm | 381 | 1,146 | 42.77 | 5.30 |

| Bra013217 | BrFH10 | A03 | 19,804,375 | 19,807,889 | AT3G25500 | AtFH1 | Plasma membrane | 1091 | 3,276 | 119.27 | 8.14 |

| Bra017889 | BrFH11 | A03 | 31,345,005 | 31,356,742 | AT1G59910 | AtFH7 | Plasma membrane | 790 | 2,373 | 85.99 | 9.03 |

| Bra029012 | BrFH12 | A03 | 5,866,076 | 5,869,007 | AT5G54650 | AtFH5 | Plasma membrane | 859 | 2,580 | 93.57 | 8.36 |

| Bra004786 | BrFH13 | A05 | 1,882,215 | 1,825,011 | AT2G43800 | AtFH2 | Chloroplast | 857 | 2,574 | 94.10 | 8.64 |

| Bra029655 | BrFH14 | A05 | 22,786,695 | 22,787,755 | AT3G07540 | AtFH10 | Chloroplast | 303 | 912 | 34.09 | 4.87 |

| Bra039436 | BrFH15 | A05 | 23,324,560 | 23,327,524 | AT3G05470 | AtFH11 | Plasma membrane | 819 | 2,460 | 91.19 | 8.86 |

| Bra037087 | BrFH16 | A05 | 9,934,103 | 9,936,953 | AT5G54650 | AtFH5 | Plasma membrane | 816 | 2,451 | 89.67 | 9.11 |

| Bra024447 | BrFH17 | A06 | 15,802,206 | 15,805,576 | AT5G67470 | AtFH6 | Plasma membrane | 897 | 2,694 | 98.69 | 9.25 |

| Bra037491 | BrFH18 | A06 | 21,200,697 | 21,203,353 | AT5G48360 | AtFH2 | Chloroplast | 807 | 2,424 | 88.31 | 5.78 |

| Bra016233 | BrFH19 | A07 | 18,713,686 | 18,716,094 | AT1G70140 | AtFH8 | Chloroplast, Vacuole | 802 | 2,409 | 87.64 | 9.51 |

| Bra012246 | BrFH20 | A07 | 9,097,123 | 9,097,833 | AT3G07540 | AtFH10 | Cytoplasm | 196 | 591 | 22.01 | 4.75 |

| Bra038438 | BrFH21 | A08 | 8,735,316 | 8,737,759 | AT1G31810 | AtFH14 | Cytoplasm | 303 | 912 | 34.14 | 8.73 |

| Bra023204 | BrFH22 | A09 | 20,717,185 | 20,722,757 | AT1G31810 | AtFH14 | Nucleus | 1163 | 3,492 | 128.06 | 6.72 |

| Bra024640 | BrFH23 | A09 | 23,866,999 | 23,869,323 | AT1G24150 | AtFH4 | Vacuole | 744 | 2,235 | 81.94 | 9.20 |

| Bra007822 | BrFH24 | A09 | 31,070,385 | 31,075,379 | AT2G25050 | AtFH18 | Cytoplasm | 1118 | 3,357 | 124.06 | 8.37 |

| Bra009306 | BrFH25 | A10 | 16,073,796 | 16,079,751 | AT5G07770 | AtFH16 | Chloroplast | 1237 | 3,714 | 137.59 | 5.86 |

| Bra002969 | BrFH26 | A10 | 6,365,088 | 6,368,134 | AT5G54650 | AtFH5 | Plasma membrane | 877 | 2,634 | 95.18 | 9.09 |

| Bra002668 | BrFH27 | A10 | 8,324,945 | 8,330,743 | AT5G58160 | AtFH13 | Cytoplasm | 1292 | 3,879 | 142.04 | 6.67 |

| Average | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ | 849.33 | 2,548 | 93.33 | 7.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).