Submitted:

06 February 2024

Posted:

08 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Characteristics of Orchid AREB/ABFs

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of Orchid AREB/ABF Proteins

2.3. Conserved Motifs and Gene Structure Analysis of Orchid AREB/ABF genes

2.4. Cis-element Analysis of orchid AREB/ABF Family

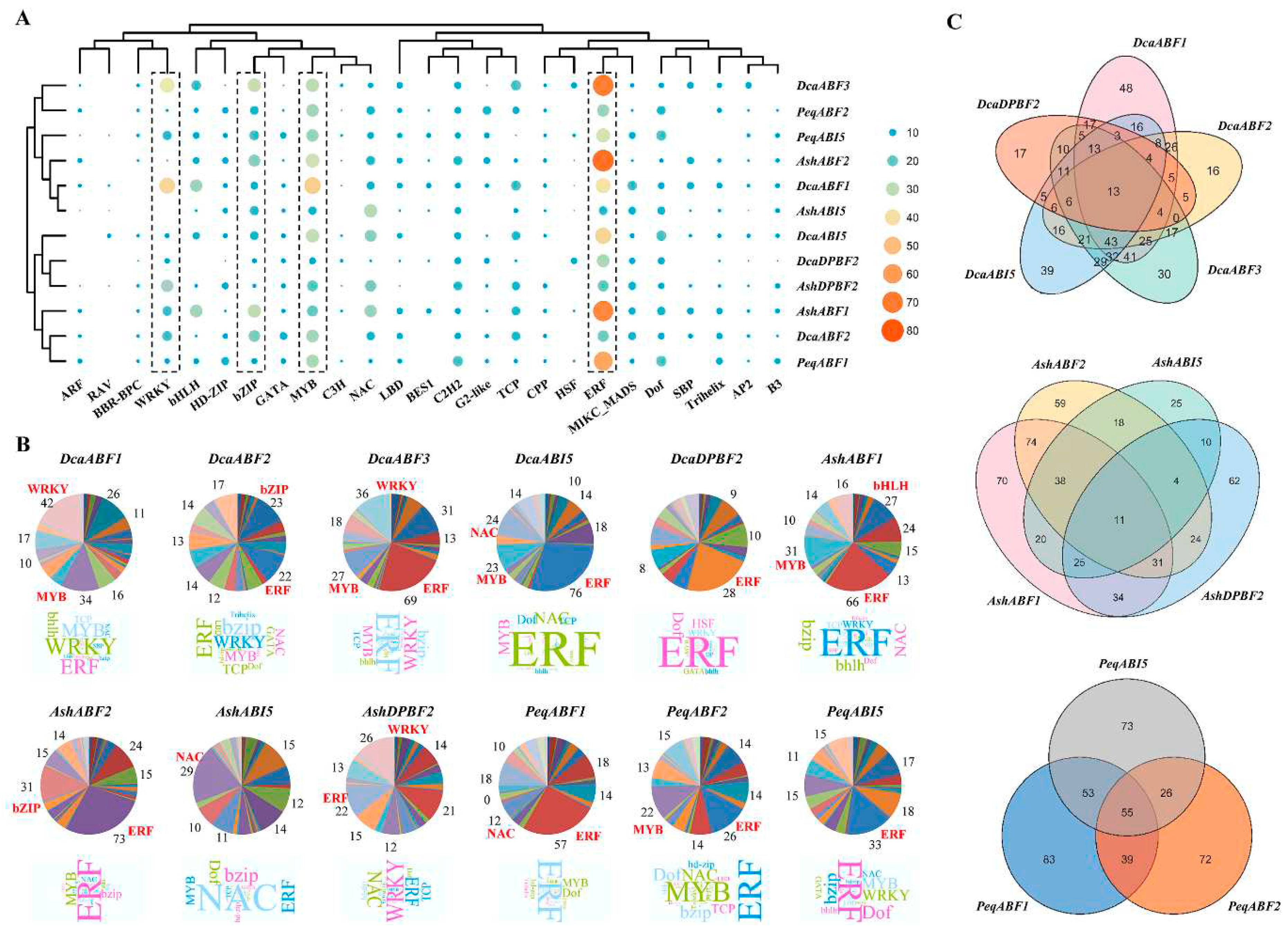

2.5. Prediction analysis of AREB/ABF-mediated regulatory network in orchid plants

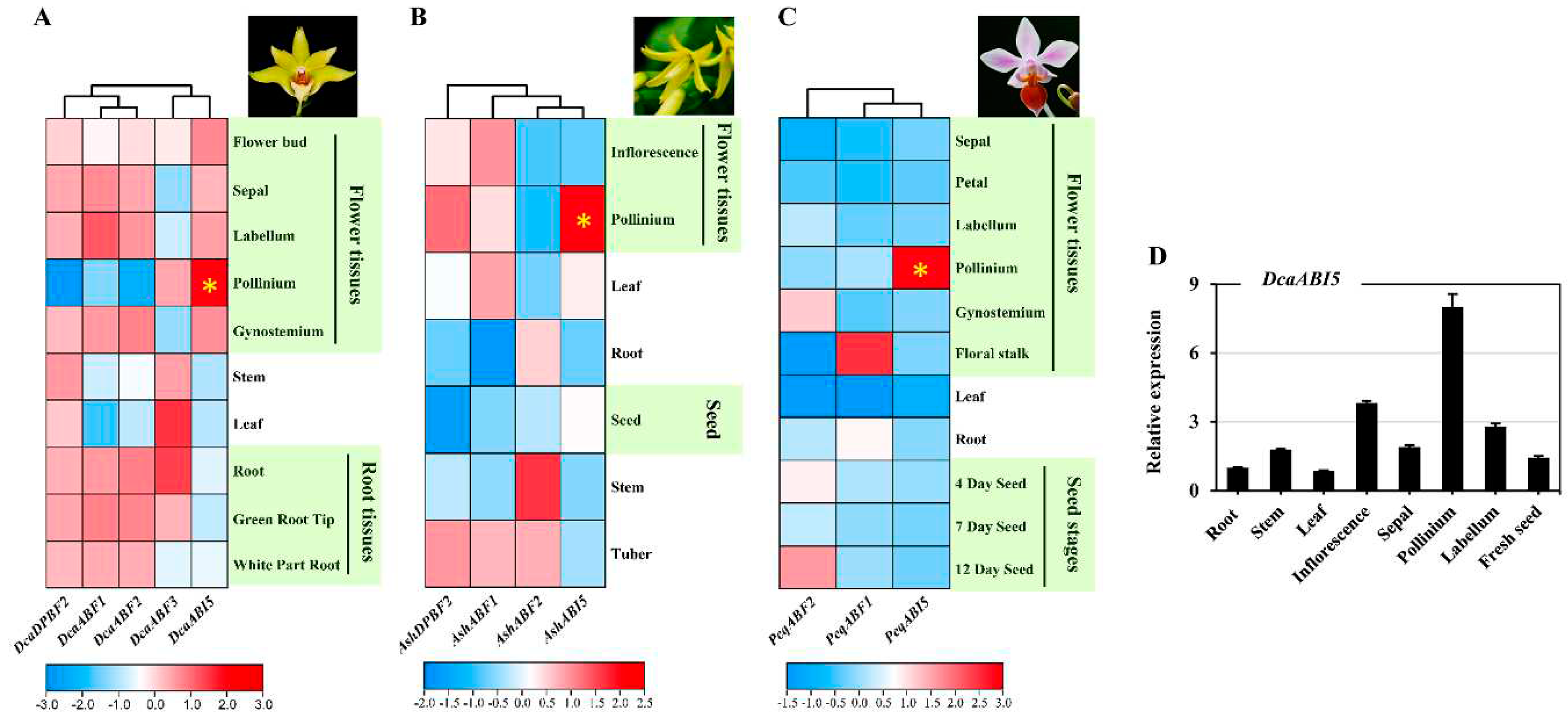

2.6. Distinct Expression Profiles of Orchid AREB/ABF Genes in Different Tissues

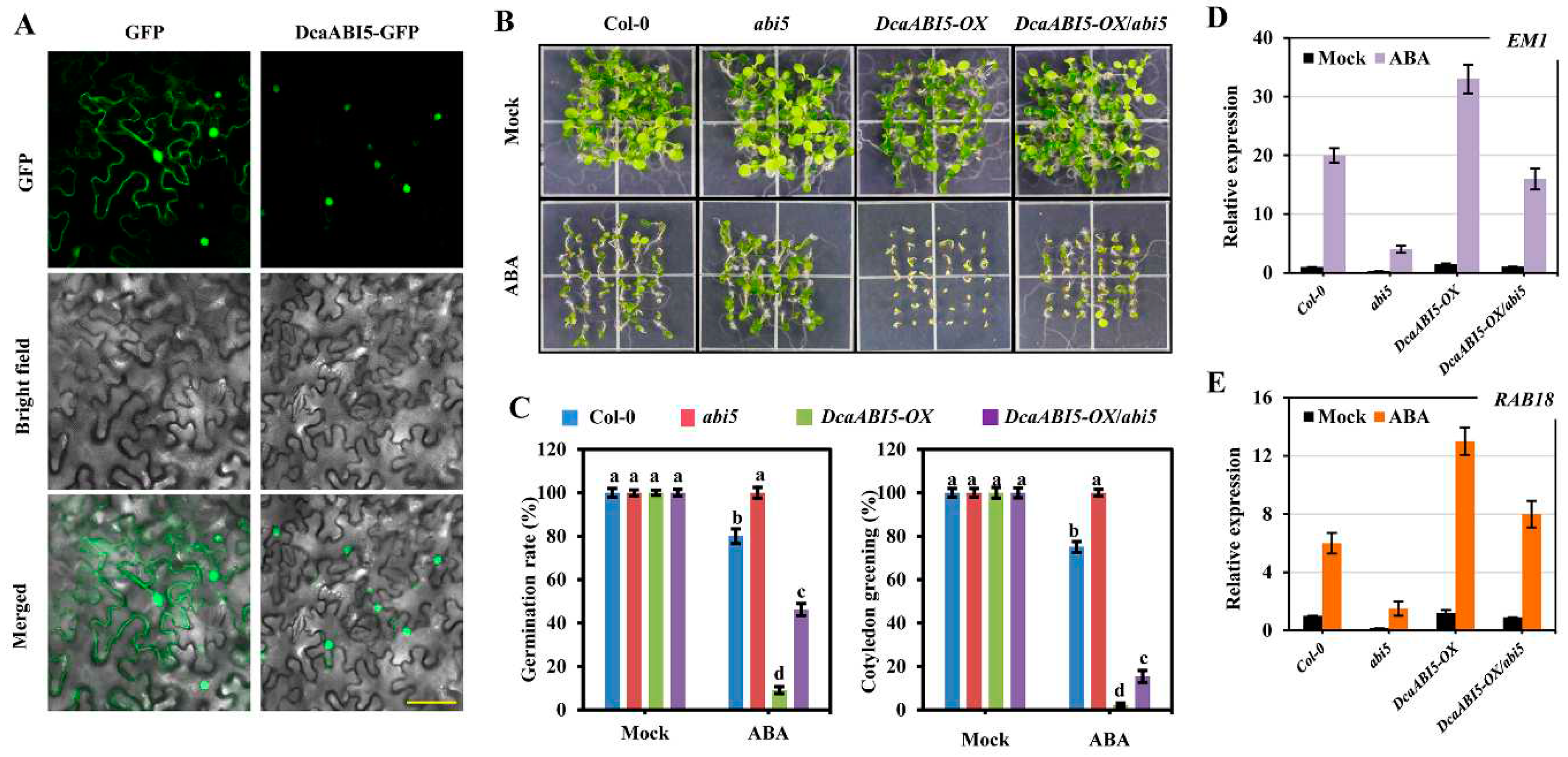

2.7. Functional Analysis of DcaABI5

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of the AREB/ABF Genes in Orchid Species

4.2. Analyses of Conserved Motifs, Exon-Intron Structures and Cis-regulatory Elements in Orchid AREB/ABF Genes

4.3. TFs regulatory network analysis

4.4. Expression Profiles of AREB/ABF Genes in Different Tissues

4.5. Plant Materials and Treatments

4.6. Vectors Construction and Plant Transformation

4.7. Analysis of Gene Expression with RT-qPCR Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fay, M.F.; Chase, M.W. Orchid biology: From Linnaeus via Darwin to the 21st century. Preface. Ann. Bot. 2009, 104, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, M.W.; Cameron, K.M.; Freudenstein, J.V.; Pridgeon, A.M.; Salazar, G.; van den Berg, C.; Schuiteman, A. An updated classification of Orchidaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2015, 177, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindlmann, P.; Kull, T.; McCormick, M. The Distribution and Diversity of Orchids. Diversity 2023, 15, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mérillon, J.M.; Kodja, H. Orchids Phytochemistry, Biology and Horticulture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Ke, S.; Yin, W.; Lan, S.; Liu, Z. Advances and prospects of orchid research and industrialization. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, F.; Xu, L.; Khazi, M.I.; Ali, S.; Rahman, M.U.; Zhu, D. Extraction, purification, and applications of vanillin: A review of recent advances and challenges. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2023, 204, 117372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Chandra, T.; Negi, A.; Jaiswal, S.; Iquebal, M.A.; Rai, A.; Kumar, D. A comprehensive review on genomic resources in medicinally and industrially important major spices for future breeding programs: Status, utility and challenges. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotz, G.; Winkler, U. Aerial Roots of Epiphytic Orchids: The Velamen Radicum and its Role in Water and Nutrient Uptake. Oecologia 2013, 171, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J., Liu, X., Vanneste, K., Proost, S., Tsai, W. C., Liu, K. W., Chen, L. J., He, Y., Xu, Q., Bian, C., et al. The genome sequence of the orchid Phalaenopsis equestris. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 65–72.

- Zhang, G.Q., Xu, Q., Bian, C., Tsai, W.C., Yeh, C.M., Liu, K.W., Yoshida, K., Zhang, L.S., Chang, S.B., Chen, F., et al. The Dendrobium catenatum Lindl. genome sequence provides insights into polysaccharide synthase, floral development and adaptive evolution. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19029.

- Zhang, G.Q., Liu, K.W., Li, Z., Lohaus, R., Hsiao, Y.Y., Niu, S.C., Wang, J. Y., Lin, Y. C., Xu, Q., Chen, L.J., et al. The Apostasia genome and the evolution of orchids. Nature 2017, 549, 379–383.

- Chao, Y. T., Chen, W. C., Chen, C. Y., Ho, H. Y., Yeh, C. H., Kuo, Y. T., Su, C. L., Yen, S. H., Hsueh, H. Y., Yeh, J. H., et al. Chromosome-level assembly, genetic and physical mapping of Phalaenopsis aphrodite genome provides new insights into species adaptation and resources for orchid breeding. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 2027–2041.

- Raghavendra, A.S., Gonugunta, V.K., Christmann, A., Grill, E. ABA perception and signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 395–401.

- Nakashima, K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. ABA signaling in stress-response and seed development. Plant Cell Reports 2013, 32, 959–70. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y., Fujita, M., Shinozaki, K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. ABA-mediated transcriptional regulation in response to osmotic stress in plants. J. Plant Res. 2011, 124, 509–25. [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Y., Fung, P., Nishimura, N., Jensen, D. R., Fujii, H., Zhao, Y., Lumba, S., Santiago, J., Rodrigues, A., Chow, T. F., et al. Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science 2009, 324, 1068–71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y., Szostkiewicz, I., Korte, A., Moes, D., Yang, Y., Christmann, A., Grill, E. Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 2009, 324, 1064-8.

- Fujita, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Pivotal role of the AREB/ABF-SnRK2 pathway in ABRE-mediated transcription in response to osmotic stress in plants. Physiol. Plant 2013, 147, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T.; Mogami, J.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. ABA-dependent and ABA-independent signaling in response to osmotic stress in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 21, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T. , Fujita, Y., Sayama, H., Kidokoro, S., Maruyama, K., Mizoi, J., Shinozaki, K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.. AREB1, AREB2, and ABF3 are master transcription factors that cooperatively regulate ABRE-dependent ABA signaling involved in drought stress tolerance and require ABA for full activation. Plant J. 2010, 61, 672–85. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, F., Sakuma, Y., Tran, L. S., Maruyama, K., Kidokoro, S., Fujita, Y., Fujita, M., Umezawa, T., Sawano, Y., Miyazono, K., et al. Arabidopsis DREB2A-interacting proteins function as RING E3 ligases and negatively regulate plant drought stress-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1693–707.

- Jakoby, M., Weisshaar, B., Dröge-Laser, W., Vicente-Carbajosa, J., Tiedemann, J., Kroj, T., Parcy, F., bZIP Research Group. bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 106–11.

- Kang, J.Y., Choi, H.I., Im, M.Y., Kim, S.Y. Arabidopsis basic leucine zipper proteins that mediate stress-responsive abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 343–57. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landschulz, W.; Johnson, P.; McKnight, S. The leucine zipper: a hypothetical structure common to a new class of DNA binding proteins. Science 1998, 240, 1759–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, R., Izawa, T., Chua, N. Plant bZIP proteins gather at ACGT elements. FASEB J. 1994, 8, 192. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siberil, Y., Doireau, P., Gantet, P. Plant bZIP G-box binding factors. Modular structure and activation mechanisms. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 5655–5666. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K., Shinozaki, K. A novel cis-acting element in an Arabidopsis gene is involved in responsiveness to drought, low-temperature, or high-salt stress. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 251–64.

- Choi, H., Hong, J., Ha, J., Kang, J., Kim, S.Y. ABFs, a family of ABA-responsive element binding factors. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 1723–30. [CrossRef]

- Busk, P.K., Pages, M. Regulation of abscisic acid-induced transcription. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998, 37, 425–35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koornneef, M., Leon-Kloosterziel, K.M., Schwartz, S.H., Zeevaart, J.A.D. The genetic and molecular dissection of abscisic acid biosynthesis and signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 1998, 36, 83–9. [CrossRef]

- Shinozaki, K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Molecular responses to dehydration and low temperature: differences and cross-talk between two stress signaling pathways. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2000, 3, 217–23. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T., Fujita, Y., Sayama, H., Kidokoro, S., Maruyama, K., Mizoi, J., Shinozaki, K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. AREB1, AREB2, and ABF3 are master transcription factors that cooperatively regulate ABRE-dependent ABA signaling involved in drought stress tolerance and require ABA for full activation. Plant J. 2010, 61, 672–685.

- Miyazono, K.; Koura, T.; Kubota, K.; Yoshida, T.; Fujita, Y.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Tanokura, M. Purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of OsAREB8 from rice, a member of the AREB/ABF family of bZIP transcription factors, in complex with its cognate DNA. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2012, 68, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikiishi, K.; Matsuura, T.; Maekawa, M. TaABF1, ABA response element binding factor 1, is related to seed dormancy and ABA sensitivity in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seeds. J. Cereal Sci. 2010, 52, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Li, Q., Mao, X., Li, A., Jing, R. Wheat Transcription Factor TaAREB3 Participates in Drought and Freezing Tolerances in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2016, 12, 257–69. [CrossRef]

- Li, F., Mei, F., Zhang, Y., Li, S., Kang, Z., Mao, H. Genome-wide analysis of the AREB/ABF gene lineage in land plants and functional analysis of TaABF3 in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 10, 558.

- Liu, T.; Zhou, T.; Lian, M.; Liu, T.; Hou, J.; Ijaz, R.; Song, B. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the AREB/ABF/ABI5 subfamily members from Solanum tuberosum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 31135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Qiu, X.; Yang, Y.; Kim, H.S.; Jia, X.; Yu, H.; Kwak, S. Sweet potato bZIP transcription factor IbABF4 confers tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, T.C.; Abdel-Mageed, H.; Aleman, L.; Lee, J.; Payton, P.; Cryer, D.; Allen, R.D. Ectopic expression of two AREB/ABF orthologs increases drought tolerance in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.J.; Sun, M.H.; Lu, J.; Liu, Y.J.; You, C.X.; Hao, Y.J. An apple CIPK protein kinase targets a novel residue of AREB transcription factor for ABA-dependent phosphorylation. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 2207–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Mou, W.; Luo, Z.; Li, L.; Limwachiranon, J.; Mao, L.; Ying, T. Developmental and stress regulation on expression of a novel miRNA, Fan-miR73 and its target ABI5 in strawberry. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, X.; Zheng, T.; Zhuo, X.; Ahmad, S.; Li, L.; Li, P.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Q. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and evolution of ABF/AREB subfamily in nine Rosaceae species and expression analysis in mei (Prunus mume). PeerJ 2021, 9, e10785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- eng, Z., Lyu, T., & Lyu, Y. LoSWEET14, a Sugar Transporter in Lily, Is Regulated by Transcription Factor LoABF2 to Participate in the ABA Signaling Pathway and Enhance Tolerance to Multiple Abiotic Stresses in Tobacco. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15093.

- Jin, M., Gan, S., Jiao, J., He, Y., Liu, H., Yin, X., Zhu, Q., Rao, J. Genome-wide analysis of the bZIP gene family and the role of AchnABF1 from postharvest kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis cv. Hongyang) in osmotic and freezing stress adaptations. Plant Sci. 2021, 308, 110927. [CrossRef]

- Fiallos-Salguero, M. S., Li, J., Li, Y., Xu, J., Fang, P., Wang, Y., Zhang, L., Tao, A.. Identification of AREB/ABF Gene Family Involved in the Response of ABA under Salt and Drought Stresses in Jute (Corchorus olitorius L.). Plants (Basel) 2023, 12, 1161.

- Uno, Y., Furihata, T., Abe, H., Yoshida, R., Shinozaki, K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis basic leucine zipper transcription factors involved in an abscisic acid-dependent signal transduction pathway under drought and high-salinity conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97, 11632-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haake, V., Cook, D., Riechmann, J.L., Pineda, O., Thomashow, M.F., Zhang, J.Z. Transcription factor CBF4 is a regulator of drought adaptation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 639–48. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.H., Henderson, D.A., Zhu, J.K. The Arabidopsis cold-responsive transcriptome and its regulation by ICE1. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 3155–75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonapartis, E., Mohamed, D., Li, J., Pan, W., Wu, J., Gazzarrini, S. CBF4/DREB1D represses XERICO to attenuate ABA, osmotic and drought stress responses in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2022, 110, 961–977. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z., Luo, X., Wang, L., Shu, K. ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 5 mediates light-ABA/gibberellin crosstalk networks during seed germination. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 4674–4682. [CrossRef]

- Carles, C., Bies-Etheve, N., Aspart, L., Léon-Kloosterziel, K. M., Koornneef, M., Echeverria, M., Delseny, M.. Regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana Em genes: role of ABI5. Plant J. 2002, 30, 373–83.

- Finkelstein, R.R., Lynch, T.J. The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response gene ABI5 encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 599–609. [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra, A.S., Gonugunta, V.K., Christmann, A., Grill, E. ABA perception and signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 395–401.

- Lee, S.C., Luan, S. ABA signal transduction at the crossroad of biotic and abiotic stress responses. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 53–60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, S.B.; Mitra, A.; Baumgarten, A.; Young, N.D.; May, G. The roles of segmental and tandem gene duplication in the evolution of large gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2004, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y., Jin, X., Liu, J., Zhao, X., Zhou, J., Wang, X., et al. (2018). The gastrodia elata genome provides insights into plant adaptation to heterotrophy. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–11.

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, G. Q., Zhang, D., Liu, X. D., Xu, X. Y., Sun, W. H., et al. Chromosome-scale assembly of the dendrobium chrysotoxum genome enhances the understanding of orchid evolution. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8.

- Chao, Y. T., Chen, W. C., Chen, C. Y., Ho, H. Y., Yeh, C. H., Kuo, Y. T., et al. Chromosome-level assembly, genetic and physical mapping of phalaenopsis aphrodite genome provides new insights into species adaptation and resources for orchid breeding. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 2027–2041. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y., Nakashima, K., Yoshida, T., Katagiri, T., Kidokoro, S., Kanamori, N., Umezawa, T., Fujita, M., Maruyama, K., Ishiyama, K., et al. Three SnRK2 protein kinases are the main positive regulators of abscisic acid signaling in response to water stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 2123–32.

- Lynch, T., Erickson, B.J. Finkelstein, R.R. Direct interactions of ABA-insensitive(ABI)-clade protein phosphatase(PP)2Cs with calcium-dependent protein kinases and ABA response element-binding bZIPs may contribute to turning off ABA response. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012, 80, 647–658. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.T., Liu, H., Stone, S., Callis, J. ABA and the ubiquitin E3 ligase KEEP ON GOING affect proteolysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana transcription factors ABF1 and ABF3. Plant J. 2013, 75, 965–76. [CrossRef]

- Vysotskii, D. A., de Vries-van Leeuwen, I. J., Souer, E., Babakov, A. V., de Boer, A. H.. ABF transcription factors of Thellungiella salsuginea: Structure, expression profiles and interaction with 14-3-3 regulatory proteins. Plant Signal Behav. 2013, 8, e22672. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z., Duan, X., Luo, L., Dai, S., Ding, Z., Xia, G. How Plant Hormones Mediate Salt Stress Responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 1117–1130. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Xu, M., Cai, X., Han, Z., Si, J., Chen, D. Jasmonate Signaling Pathway Modulates Plant Defense, Growth, and Their Trade-Offs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3945. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M., Yu, G., Cao, C., Liu, P. Metabolism, signaling, and transport of jasmonates. Plant Commun. 2021, 2, 100231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, X., Zhou, J., Wu, C.E., Yang, S., Liu, Y., Chai, L., Xue, Z. The interplay between ABA/ethylene and NAC TFs in tomato fruit ripening: a review. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 106, 223–238. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M. Foes or Friends: ABA and Ethylene Interaction under Abiotic Stress. Plants (Basel) 2021, 10, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G., Kilic, A., Karady, M., Zhang, J., Mehra, P., Song, X., Sturrock, C. J., Zhu, W., Qin, H., Hartman, S., et al. Ethylene inhibits rice root elongation in compacted soil via ABA- and auxin-mediated mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022, 119, e2201072119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z., Sheerin, D.J., von Roepenack-Lahaye E., Stahl, M., Hiltbrunner, A. The phytochrome interacting proteins ERF55 and ERF58 repress light-induced seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 1656. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B., Jin, J., Guo, A.Y., Zhang, H., Luo, J., Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296-7. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Wu, Y., Li, J., Wang, X., Zeng, Z., Xu, J., Liu, Y., Feng, J., Chen, H., He, Y., Xia, R. TBtools-II: A "one for all, all for one" bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [CrossRef]

- Fu, C. H., Chen, Y. W., Hsiao, Y. Y., Pan, Z. J., Liu, Z. J., Huang, Y. M., Tsai, W. C., Chen, H. H. OrchidBase: a collection of sequences of the transcriptome derived from orchids. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011, 52, 238–243. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W. C., Fu, C. H., Hsiao, Y. Y., Huang, Y. M., Chen, L. J., Wang, M., Liu, Z. J., Chen, H. H. OrchidBase 2.0: comprehensive collection of Orchidaceae floral transcriptomes. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, e7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C., Jiang, Y., Shi, M., Wu, X., Wu, G. ABI5 acts downstream of miR159 to delay vegetative phase change in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 339–350. [CrossRef]

- Clough, S.J.; Bent, A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998, 16, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liang, J. Scaffold protein RACK1 regulates BR signaling by modulating the nuclear localization of BZR1. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 1804–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Gene | Gene Id | Coding Sequence (CDS) Length | Protein Length (aa) | Molecular Mass (kDa) | Theoretical pI | Sub-Cellular Location |

| Dendrobium catenatum | DcaABF1 | Dca012913 | 1224 | 407 | 43.50 | 7.7 | Nucleus |

| DcaABF2 | Dca011277 | 1221 | 406 | 42.69 | 9.13 | Nucleus | |

| DcaABF3 | Dca006042 | 1191 | 396 | 42.67 | 9.19 | Nucleus | |

| DcaABI5 | Dca002027 | 1074 | 357 | 38.95 | 7.60 | Nucleus | |

| DcaDPBF2 | Dca016354 | 936 | 311 | 34.83 | 9.50 | Nucleus | |

| Apostasia shenzhenica | AshABF1 | Ash014915 | 1143 | 380 | 40.72 | 8.71 | Nucleus |

| AshABF2 | Ash016767 | 1278 | 425 | 45.56. | 9.00 | Nucleus | |

| AshABI5 | Ash004480 | 1188 | 395 | 42.51 | 5.47 | Nucleus | |

| AshDPBF2 | Ash013161 | 1023 | 340 | 37.18 | 8.74 | Nucleus | |

| Phalaenopsis equestris | PeqABF1 | Peq004088 | 1221 | 406 | 42.60 | 9.39 | Nucleus |

| PeqABF2 | Peq011139 | 1191 | 396 | 42.57. | 8.65 | Nucleus | |

| PeqABI5 | Peq013682 | 1068 | 355 | 39.91 | 9.42 | Nucleus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).