Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Physicochemical Characterization of the BpHSF Gene Family

2.2. BpHSF Protein Multiple Sequence Comparison

2.3. Chromosomal Localization of BpHSF Genes

2.4. BpHSF Evolutionary Tree Analysis

2.5. Protein Motifs and Gene Structure of BpHSF Genes

2.6. Covarianceanalysis of BpHSF

2.7. Analysis of BpHSF Promoter Cis-Acting Elements

2.8. Secondary and Tertiary Structure Prediction and Subcellular Localisation of the BpHSF Protein

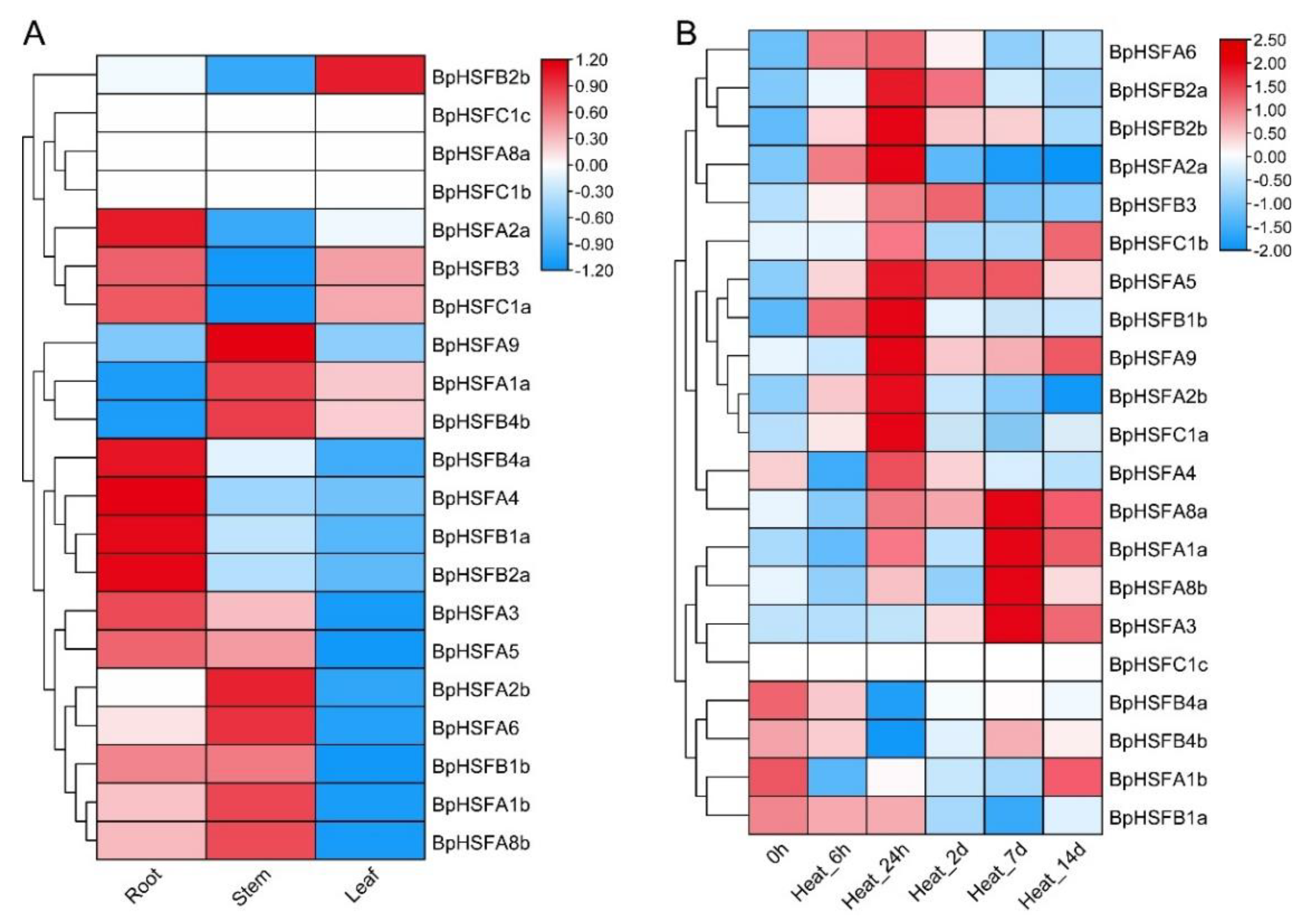

2.9. Expression of BpHSF Gene in Different Tissues and Its Response to High Temperature Stressf

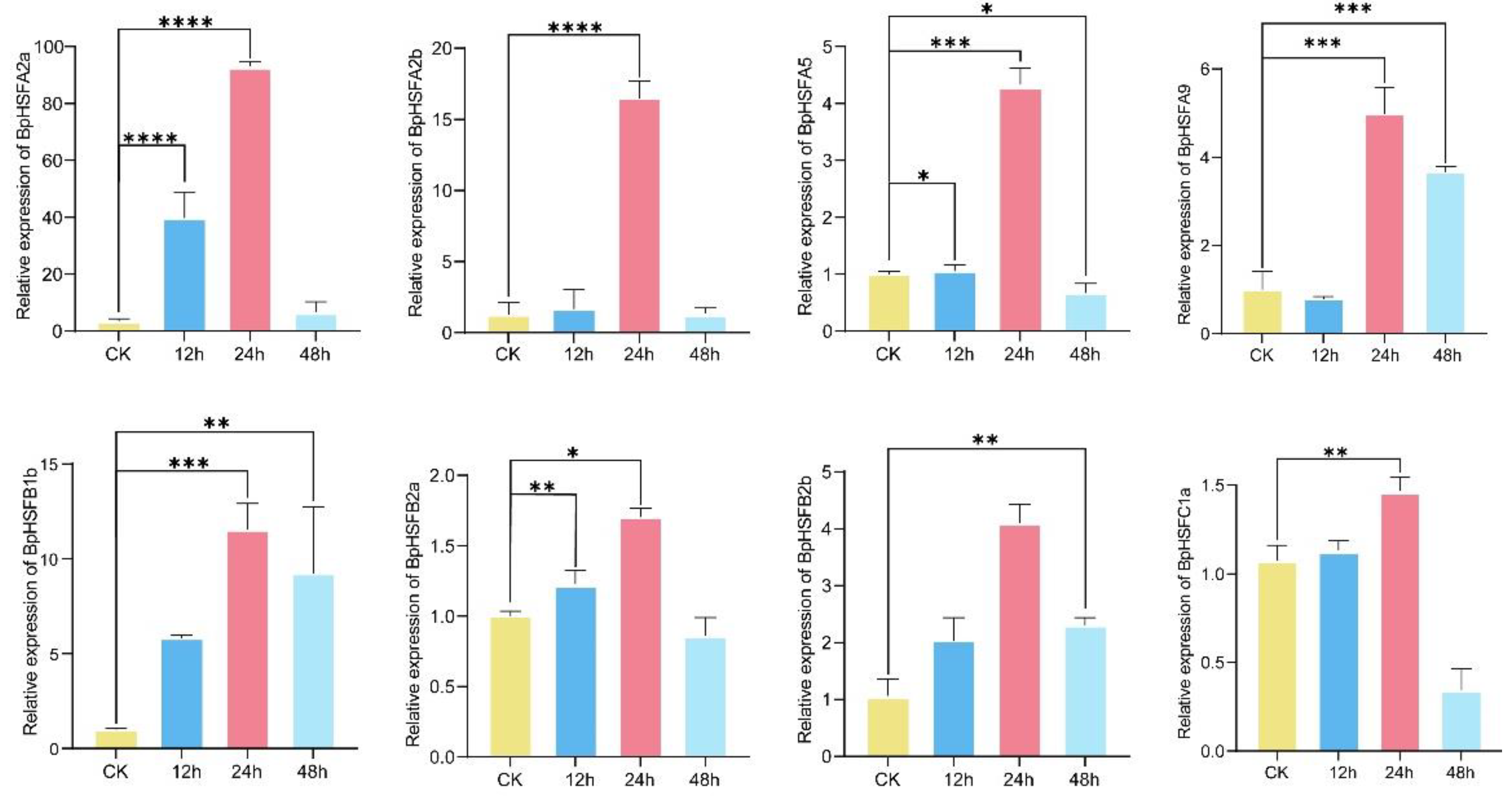

2.10. BpHSF Expression Validation Through qRT-PCR

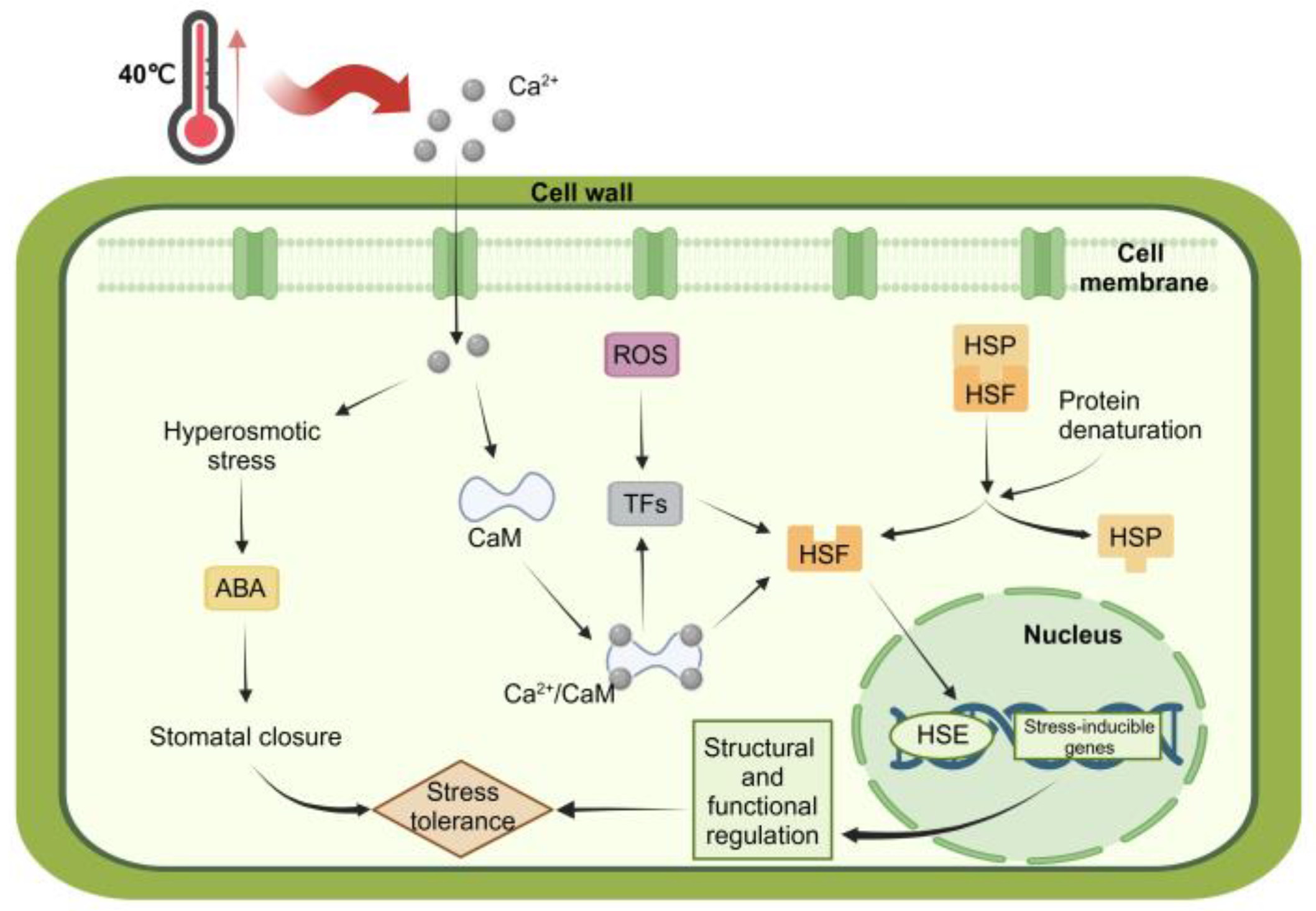

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. BpHSF Gene Family Identification and Characterization

4.2. Multiple Sequence Alignment, Chromosomal Localization and Phylogeny

4.3. BpHSF Conserved Motif Prediction and Gene Structure Analysis

4.4. Analysis of BpHSF Covarianceand Cis-Acting Elements

4.5. BpHSF Protein Structure Prediction and Subcellular Localization

4.6. Plant Materials and Treatments

4.7. Expression Profiles Based on RNA-Seq Data

4.8. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suzuki, N.; Rivero, R. M.; Shulaev, V.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R. Abiotic and biotic stress combinations. New Phytol. 2014, 203, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushman, J. C.; Denby, K.; Mittler, R. Plant responses and adaptations to a changing climate. Plant J. 2022, 109, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramegowda, V.; Senthil-Kumar, M. The interactive effects of simultaneous biotic and abiotic stresses on plants: Mechanistic understanding from drought and pathogen combination. J Plant Physiol. 2015, 176, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, T. Regulatory mechanisms of transcription factors in plant morphology and function. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Ohtani, M.; Yamaguchi, M.; Toyooka, K.; Wakazaki, M.; Sato, M.; Kubo, M.; Nakano, Y.; Sano, R.; Hiwatashi, Y.; Murata, T.; Kurata, T.; Yoneda, A.; Kato, K.; Hasebe, M.; Demura, T. Contribution of NAC transcription factors to plant adaptation to land. Science. 2014, 343, 1505–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; He, G.; Hou, Q.; Fan, Y.; Duan, L.; Li, K.; Wei, X.; Qiu, Z.; Chen, E.; He, T. Systematic analysis and expression profiles of TCP gene family in Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn.) revealed the potential function of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 in response to abiotic stress. BMC genomics 2022, 23, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X. M.; Sun, H. M. DOF transcription factors: Specific regulators of plant biological processes. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1044918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abunimye, D. A.; Okafor, I. M.; Okorowo, H.; Obeagu, E. I. The role of GATA family transcriptional factors in haematological malignancies: A review. Medicine. 2024, 103, e37487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Fang, Y.; An, C.; Yao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, R.; Wang, L.; Aslam, M.; Cheng, Y. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the bHLH gene family in passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) and its response to abiotic stress. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L. L.; Liu, Y.; Mao, Y. W.; Wu, X. Y.; Zheng, X. L.; Zhao, W. Y.; Mo, X. Y.; Wang, R. R.; Wu, Q.; Wang, D. F.; Li, Y. H.; Yang, Y. F.; Bai, Q. Z.; Zhang, X. J.; Zhou, S. L.; Zhao, B. L.; Liu, C. N.; Liu, Y.; Tadege, M.; Chen, J. H. GRAS transcription factor PINNATE-LIKE PENTAFOLIATA2 controls compound leaf morphogenesis in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell. 2024, 36, 1755–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Tang, W. S.; Zhou, Y. B.; Chen, J.; Xu, Z. S.; Ma, R.; Dong, Y. S.; Ma, Y. Z.; Chen, M. AP2/ERF transcription factor confers drought tolerance in transgenic soybean by interacting with GmERFs. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2022, 170, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, L.; Priya, M.; Kaushal, N.; Bhandhari, K.; Chaudhary, S.; Dhankher, O. P.; Prasad, P. V. V.; Siddique, K. H. M.; Nayyar, H. Plant growth-regulating molecules as thermoprotectants: functional relevance and prospects for improving heat tolerance in food crops. J Exp Bot. 2020, 71, 569–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Yuan, Y. H.; Du, N. S.; Wang, Y.; Shu, S.; Sun, J.; Guo, S. R. Proteomic analysis of heat stress resistance of cucumber leaves when grafted onto Momordica rootstock. Hortic Res-England 2018, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, H.; Mizoi, J.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Complex plant responses to drought and heat stress under climate change. Plant J. 2024, 117, 1873–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T. Y.; Hoh, K. L.; Boonyaves, K.; Krishnamoorthi, S.; Urano, D. Diversification of heat shock transcription factors expanded thermal stress responses during early plant evolution. Plant Cell. 2022, 34, 3557–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, K. D.; Berberich, T.; Ebersberger, I.; Nover, L. The plant heat stress transcription factor (Hsf) family: structure, function and evolution. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012, 1819, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrási, N.; Pettkó-Szandtner, A.; Szabados, L. Diversity of plant heat shock factors: regulation, interactions, and functions. J Exp Bot. 2021, 72, 1558–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteranderl, R.; Rabenstein, M.; Shin, Y. K.; Liu, C. W.; Wemmer, D. E.; King, D. S.; Nelson, H. C. Biochemical and biophysical characterization of the trimerization domain from the heat shock transcription factor. Biochemistry 1999, 38(12), 3559–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nover, L.; Bharti, K.; Döring, P.; Mishra, S. K.; Ganguli, A.; Scharf, K. D. Arabidopsis and the heat stress transcription factor world: how many heat stress transcription factors do we need? Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001, 6, 177–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotak, S.; Port, M.; Ganguli, A.; Bicker, F.; von Koskull-Döring, P. , Characterization of C-terminal domains of Arabidopsis heat stress transcription factors (Hsfs) and identification of a new signature combination of plant class A Hsfs with AHA and NES motifs essential for activator function and intracellular localization. Plant J. 2004, 39, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerklotz, D.; Döring, P.; Bonzelius, F.; Winkelhaus, S.; Nover, L. The balance of nuclear import and export determines the intracellular distribution and function of tomato heat stress transcription factor HsfA2. Mol Cell Biol. 2001, 21, 1759–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Koskull-Döring, P.; Scharf, K. D.; Nover, L. The diversity of plant heat stress transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2007, 12, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiederrecht, G.; Seto, D.; Parker, C. S. Isolation of the gene encoding the S. cerevisiae heat shock transcription factor. Cell. 1988, 54, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharf, K. D.; Rose, S.; Zott, W.; Schöffl, F.; Nover, L. Three tomato genes code for heat stress transcription factors with a region of remarkable homology to the DNA-binding domain of the yeast HSF. Embo J. 1990, 9, 4495–5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wu, J.; Ji, Q.; Wang, C.; Luo, L.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Genome-wide analysis of heat shock transcription factor families in rice and Arabidopsis thaliana. J Genet Genomics. 2008, 35, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Shou, H. X. Identification and expression analysis of OsHsfs in rice. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2009, 10, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dong, Q.; Jiang, H.; Zhu, S.; Chen, B.; Xiang, Y. Genome-wide analysis of the heat shock transcription factors in Populus trichocarpa and Medicago truncatula. Mol Biol Rep. 2012, 39, 1877–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Chen, J.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, X.; Niu, M.; Chen, X.; Xie, K.; Huang, R.; Zhan, S.; Su, Q.; Shen, M.; Peng, D.; Ahmad, S.; Zhao, K.; Liu, Z. J.; Zhou, Y. General analysis of heat shock factors in the cymbidium ensifolium genome provided insights into their evolution and special roles with response to temperature. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Ohama, N.; Nakajima, J.; Kidokoro, S.; Mizoi, J.; Nakashima, K.; Maruyama, K.; Kim, J. M.; Seki, M.; Todaka, D.; Osakabe, Y.; Sakuma, Y.; Schöffl, F.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis HsfA1 transcription factors function as the main positive regulators in heat shock-responsive gene expression. Mol Genet Genomics. 2011, 286, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yu, M.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Qiao, G.; Wu, L.; Han, X.; Zhuo, R. SaHsfA4c from sedum alfredii hance enhances cadmium tolerance by regulating ROS-Scavenger activities and heat shock proteins expression. Front Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resentini, F.; Orozco-Arroyo, G.; Cucinotta, M.; Mendes, M. A. The impact of heat stress in plant reproduction. Front Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1271644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almoguera, C.; Prieto-Dapena, P.; Díaz-Martín, J.; Espinosa, J. M.; Carranco, R.; Jordano, J. The HaDREB2 transcription factor enhances basal thermotolerance and longevity of seeds through functional interaction with HaHSFA9. BMC Plant Biol. 2009, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolmos, E.; Chow, B. Y.; Pruneda-Paz, J. L.; Kay, S. A. HsfB2b-mediated repression of PRR7 directs abiotic stress responses of the circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014, 111, 16172–16177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wunderlich, M.; Gross-Hardt, R.; Schöffl, F. Heat shock factor HSFB2a involved in gametophyte development of Arabidopsis thaliana and its expression is controlled by a heat-inducible long non-coding antisense RNA. Plant Mol Biol. 2014, 85, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Bayon, R.; Shen, Y.; Groszmann, M.; Zhu, A.; Wang, A.; Allu, A. D.; Dennis, E. S.; Peacock, W. J.; Greaves, I. K. Senescence and defense pathways contribute to heterosis. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Yan, L.; Li, H.; Lian, X.; Cheng, J.; Wang, W.; Zheng, X.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Ye, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Feng, J. Genome-wide identification of HSF family in peach and functional analysis of PpHSF5 involvement in root and aerial organ development. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, D.; Yamaguchi, K.; Nishiuchi, T. High-level overexpression of the Arabidopsis thaliana HsfA2 gene confers not only increased themotolerance but also salt/osmotic stress tolerance and enhanced callus growth. J Exp Bot. 2007, 58, 3373–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-Schaminet, K. Y.; Baniwal, S. K.; Bublak, D.; Nover, L.; Scharf, K. D. Specific Interaction between tomato HsfA1 and HsfA2 creates hetero-oligomeric superactivator complexes for synergistic activation of heat stress gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2009, 284, 20848–20857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. C.; Niu, C. Y.; Yang, C. R.; Jinn, T. L. The heat stress factor HSFA6b connects ABA signaling and ABA-Mediated heat responses. Plant Physiology. 2016, 172, 1182–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, A.; Yabuta, Y.; Yoshida, E.; Maruta, T.; Yoshimura, K.; Shigeoka, S. Arabidopsis thaliana heat shock transcription factor A2 as a key regulator in response to several types of environmental stress. Plant J. 2006, 48, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Lu, J. P.; Zhai, Y. F.; Chai, W. G.; Gong, Z. H.; Lu, M. H. Genome-wide analysis, expression profile of heat shock factor gene family (CaHsfs) and characterisation of CaHsfA2 in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Bmc Plant Biology 2015, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P. S.; Yu, T. F.; He, G. H.; Chen, M.; Zhou, Y. B.; Chai, S. C.; Xu, Z. S.; Ma, Y. Z. Genome-wide analysis of the Hsf family in soybean and functional identification of GmHsf-34 involvement in drought and heat stresses. Bmc Genomics. 2014, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Ni, D.; Wang, M.; Guo, G. Genome-wide characterization of tea plant (Camellia sinensis) Hsf transcription factor family and role of CsHsfA2 in heat tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yin, J.; Zhu, L.; Xu, L.; Wu, W.; Lu, Y.; Chen, J.; Shi, J.; Hao, Z. Genome-wide analysis of the liriodendron chinense Hsf gene family under abiotic stress and characterization of the LcHsfA2a gene. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, M.; Mitsuda, N.; Ohme-Takagi, M. Arabidopsis HsfB1 and HsfB2b act as repressors of the expression of heat-inducible Hsfs but positively regulate the acquired thermotolerance. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, S.; Pandey, M. M.; Rawat, A. K. S. Medicinal plants of the Betula-Traditional uses and a phytochemical-pharmacological review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 159, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; An, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z. H.; Zhao, Y. H.; Wang, X. C. Differences and similarities in radial growth of Betula species to climate change. J Forestry Res. 2024, 35, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, Y. C.; Yu, L. L.; Zheng, T.; Wang, S.; Yue, Z.; Jiang, J.; Kumari, S.; Zheng, C. F.; Tang, B.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Q.; Chen, J. J.; Zhang, W. B.; Kuang, H. H.; Robertson, J. S.; Zhao, P. X.; Li, H. Y.; Shu, S. Q.; Yordanov, Y. S.; Huang, H. J.; Goodstein, D. M.; Gai, Y.; Qi, Q.; Min, J. M.; Xu, C. Y.; Wang, S. B.; Qu, G. Z.; Paterson, A. H.; Sankoff, D.; Wei, H. R.; Liu, G. F.; Yang, C. P. Genome sequence and evolution of B. platyphylla. Hortic Res. 2021, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hu, H.; Wang, W.; Wei, Q.; Hu, T.; Bao, C. Genome-wide identification and functional characterization of the heat shock factor family in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) under abiotic stress conditions. Plants 2020, 9, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. J.; Meng, P. P.; Yang, G. Y.; Zhang, M. Y.; Peng, S. B.; Zhai, M. Z. Genome-wide identification and transcript profiles of walnut heat stress transcription factor involved in abiotic stress. Bmc Genomics. 2020, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. Y.; Huang, C. Q.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H. F.; Yu, J. H.; Hu, Z. Y.; Hua, W. Systematic analysis of family genes in the genome reveals novel responses to heat, drought and high CO2 stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zheng, S. G.; Liu, R.; Lu, J.; Lu, L.; Zhang, C. H.; Liu, Z. H.; Luo, C. P.; Zhang, L.; Yant, L.; Wu, Y. Genome-wide identification, phylogenetic and expression analysis of the heat shock transcription factor family in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Bmc Genomics 2019, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, S. N.; Liu, B. H.; Zhang, Y. Y.; Li, G. L.; Guo, X. L. Genome-wide identification and abiotic stress-responsive pattern of heat shock transcription factor family in Triticum aestivum L. Bmc Genomics. 2019, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamshad, A.; Rashid, M.; Zaman, Q. U. In-silico analysis of heat shock transcription factor (OsHSF) gene family in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Bmc Plant Biology 2023, 23, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, W. H.; Tang, X. H.; Li, J. S.; Zheng, Q. M.; Wang, T.; Cheng, S. Z.; Chen, S. P.; Cao, S. J.; Cao, G. Q. Genome wide investigation of Hsf gene family in Phoebe bournei: identification, evolution, and expression after abiotic stresses. J Forestry Res. 2024, 35, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wan, X. L.; Yu, J. Y.; Wang, K. L.; Zhang, J. Genome-wide identification, classification, and expression analysis of the Hsf gene family in carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus). Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorno, F.; Guerriero, G.; Baric, S.; Mariani, C. Heat shock transcriptional factors in Malus domestica: identification, classification and expression analysis. Bmc Genomics. 2012, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M. J.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, W. W.; Luo, X. B.; Xie, Y.; Fan, L. X.; Liu, L. W. Genome-wide characterization and evolutionary analysis of heat shock transcription factors (HSFs) to reveal their potential role under abiotic stresses in radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Bmc Genomics 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Bautista, Y.; Arroyo-Alvarez, E.; Fuentes, G.; Girón-Ramírez, A.; Chan-León, A.; Estrella-Maldonado, H.; Xoconostle, B.; Santamaría, J. M. Genome-wide analysis of HSF genes and their role in the response to drought stress in wild and commercial Carica papaya L. genotypes. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam 2024, 328, 112889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Dang, H.; Zhou, L. D.; Hu, J.; Jin, X.; Han, Y. Z.; Wang, S. J. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the HSF gene family in Poplar. Forests. 2023, 14, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. A.; Jin, Y.; He, D.; Di, H. C.; Liang, Y.; Xu, Y. X. A Genome-Wide analysis and expression profile of heat shock transcription factor (Hsf) gene family in Rhododendron simsii. Plants. 2023, 12, 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z. B.; Guo, C.; Zhao, X. B.; Li, Z. Y.; Mou, Y. F.; Sun, Q. X.; Wang, J.; Yuan, C. L.; Li, C. J.; Cong, P.; Shan, S. H. Hsf transcription factor gene family in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.): genome-wide characterization and expression analysis under drought and salt stresses. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1214732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, R. J.; Wang, S. W.; Wang, X. X.; Peng, J. M.; Guo, J.; Cui, G. H.; Chen, M. L.; Mu, J.; Lai, C. J. S.; Huang, L. Q.; Wang, S.; Shen, Y. Genome-Wide characterization and expression of the Hsf gene family in Salvia miltiorrhiza (Danshen) and the potential thermotolerance of SmHsf1 and SmHsf7 in Yeast. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 8461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X. L.; Yuan, S. N.; Zhang, H. N.; Zhang, Y. Y.; Zhang, Y. J.; Wang, G. Y.; Li, Y. Q.; Li, G. L. Heat-response patterns of the heat shock transcription factor family in advanced development stages of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and thermotolerance-regulation by TaHsfA2-10. Bmc Plant Biology 2020, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Huang, Q.; Sun, W.; Ma, Z.; Huang, L.; Wu, Q.; Tang, Z.; Bu, T.; Li, C.; Chen, H. Genome-wide investigation of the heat shock transcription factor (Hsf) gene family in Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum). Bmc Genomics. 2019, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. L.; Liu, Y. H.; Chai, G. F.; Zhang, D.; Fang, Y. Y.; Deng, K.; Aslam, M.; Niu, X. P.; Zhang, W. B.; Qin, Y.; Wang, X. M. Identification of passion fruit gene family and the functional analysis of in response to heat and osmotic stress. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2023, 200, 107800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D. X.; Qi, X. Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R. L.; Wang, C.; Sun, T. X.; Zheng, J.; Lu, Y. Z. Genome-wide analysis of the heat shock transcription factor gene family in (Hance) Hedl identifies potential candidates for resistance to abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2022, 175, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G. T.; Meng, X. X.; Wang, S. F.; Mi, Y. L.; Qin, Z. F.; Liu, T. X.; Zhang, Y. M.; Wan, H. H.; Chen, W. Q.; Sun, W.; Cao, X.; Li, L. X. Genome-wide identification of HSF gene family and their expression analysis in vegetative tissue of young seedlings of hemp under different light treatments. Ind Crop Prod. 2023, 204, 117375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Han, Y. T.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, F. L.; Li, Y. J.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y. J.; Wen, Y. Q. Identification and expression analysis of heat shock transcription factors in the wild Chinese grapevine (Vitis pseudoreticulata). Plant Physiol Bioch. 2016, 99, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. K.; Poonia, A. K.; Chaudhary, R.; Baranwal, V. K.; Arora, D.; Kumar, R.; Chauhan, H. Genome-wide identification, phylogeny and expression analysis of HSF gene family in barley during abiotic stress response and reproductive development. Plant Gene. 2020, 23, 100231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, T.; Wang, L.; Cao, K.; Gao, W.; Yan, S.; Cao, J.; Lu, J.; Ma, C.; Chang, C.; Zhang, H. A wheat heat shock transcription factor gene, TaHsf-7A, regulates seed dormancy and germination. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024, 210, 108541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Lu, J. P.; Zhai, Y. F.; Chai, W. G.; Gong, Z. H.; Lu, M. H. Genome-wide analysis, expression profile of heat shock factor gene family (CaHsfs) and characterisation of CaHsfA2 in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Meng, P.; Yang, G.; Zhang, M.; Peng, S.; Zhai, M. Z. Genome-wide identification and transcript profiles of walnut heat stress transcription factor involved in abiotic stress. BMC Genomics. 2020, 21, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, W.; Hu, X.; Meng, L.; Xiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Luo, H.; Ziyomo, C.; Chan, Z. HSFA3 functions as a positive regulator of HSFA2a to enhance thermotolerance in perennial ryegrass. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024, 208, 108512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wan, X. L.; Yu, J. Y.; Wang, K. L.; Zhang, J. Genome-Wide identification, classification, and expression analysis of the Hsf gene family in Carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus). Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. X.; Jiang, H. Y.; Chu, Z. X.; Tang, X. L.; Zhu, S. W.; Cheng, B. J. Genome-wide identification, classification and analysis of heat shock transcription factor family in maize. BMC Genomics. 2011, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. S.; Yu, T. F.; He, G. H.; Chen, M.; Zhou, Y. B.; Chai, S. C.; Xu, Z. S.; Ma, Y. Z. Genome-wide analysis of the Hsf family in soybean and functional identification of GmHsf-34 involvement in drought and heat stresses. BMC Genomics. 2014, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banakar, S. N.; PrasannaKumar, M. K.; Mahesh, H. B.; Parivallal, P. B.; Puneeth, M. E.; Gautam, C.; Pramesh, D.; Shiva Kumara, T. N.; Girish, T. R.; Nori, S.; Narayan, S. S. Red-seaweed biostimulants differentially alleviate the impact of fungicidal stress in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jia, H.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, M.; Hu, J. Molecular evolution and expression divergence of the Populus euphratica Hsf genes provide insight into the stress acclimation of desert poplar. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 30050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Chai, G.; Zhang, D.; Fang, Y.; Deng, K.; Aslam, M.; Niu, X.; Zhang, W.; Qin, Y.; Wang, X. Identification of passion fruit HSF gene family and the functional analysis of PeHSF-C1a in response to heat and osmotic stress. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023, 200, 107800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Lu, M.; Chen, J. Hsf and Hsp gene families in Populus: genome-wide identification, organization and correlated expression during development and in stress responses. BMC Genomics. 2015, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evrard, A.; Kumar, M.; Lecourieux, D.; Lucks, J.; von Koskull-Döring, P.; Hirt, H. Regulation of the heat stress response in Arabidopsis by MPK6-targeted phosphorylation of the heat stress factor HsfA2. PeerJ. 2013, 1, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakery, A.; Vraggalas, S.; Shalha, B.; Chauhan, H.; Benhamed, M.; Fragkostefanakis, S. Heat stress transcription factors as the central molecular rheostat to optimize plant survival and recovery from heat stress. New phytologist. 2024, 244, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Geng, J.; Du, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, W.; Fang, Q.; Yin, Z.; Li, J.; Yuan, X.; Fan, Y. Heat shock transcription factor (Hsf) gene family in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris): Genome-wide identification, phylogeny, evolutionary expansion and expression analyses at the sprout stage under abiotic stress. BMC Plant Biology. 2022, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Liu, J.H.; Ma, X.; Luo, D.X.; Gong, Z.H.; Lu, M.H. The plant heat stress transcription factors (HSFs): structure, regulation, and function in response to abiotic stresses. Frontiers in plant science. 2016, 7, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J. W.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z. H.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y. L.; Feng, J. T.; Chen, H.; He, Y. H.; Xia, R. TBtools-II: A "one for all, all for one" bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol Plant. 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A. Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J. M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G. K.; Shi, W. feature counts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Fang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, L. Genome-Wide identification and expression analysis of auxin response factor (ARF) gene family in Longan (Dimocarpus longan L.). Plants (Basel) 2020, 9, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K. J.; Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods. 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Gene name | MF | MW | pI | II | AI | GRAVY | SL |

| 1 | BpHSFA1a | C2707H4259N761O880S27 | 62410.79 | 4.85 | 67.51 | 68.25 | -0.615 | Nucleus |

| 2 | BpHSFA1b | C2443H3836N696O789S23 | 56318.90 | 5.14 | 52.68 | 69.32 | -0.643 | Nucleus |

| 3 | BpHSFA2a | C1760H2779N509O536S14 | 40094.36 | 5.94 | 63.46 | 64.21 | -0.908 | Nucleus |

| 4 | BpHSFA2b | C1878H2982N540O608S13 | 43270.37 | 4.86 | 58.74 | 79.59 | -0.517 | Nucleus |

| 5 | BpHSFA3 | C2831H4389N759O901S18 | 64050.62 | 4.77 | 57.57 | 70.76 | -0.511 | Nucleus |

| 6 | BpHSFA4 | C1993H3072N552O615S16 | 45118.61 | 5.50 | 39.18 | 67.27 | -0.476 | Nucleus |

| 7 | BpHSFA5 | C2363H3686N678O765S13 | 54250.12 | 5.50 | 59.56 | 63.02 | -0.774 | Nucleus |

| 8 | BpHSFA6 | C1673H2617N473O507S12 | 37853.77 | 5.39 | 56.14 | 78.14 | -0.700 | Nucleus |

| 9 | BpHSFA9 | C2463H3909N681O822S22 | 56918.52 | 4.73 | 70.13 | 69.69 | -0.707 | Nucleus |

| 10 | BpHSFA8a | C1022H1586N284O309S7 | 23019.97 | 6.15 | 43.09 | 69.59 | -0.763 | Nucleus |

| 11 | BpHSFA8b | C1795H2828N490O578S23 | 41258.52 | 4.80 | 49.06 | 67.60 | -0.772 | Nucleus |

| 12 | BpHSFB1a | C1046H1643N291O315S11 | 23687.97 | 8.78 | 49.70 | 66.80 | -0.726 | Nucleus |

| 13 | BpHSFB1b | C1055H1653N305O364S9 | 24722.10 | 4.90 | 30.82 | 56.64 | -0.707 | Nucleus |

| 14 | BpHSFB2a | C1475H2318N416O468S10 | 33687.74 | 5.47 | 53.72 | 67.22 | -0.687 | Nucleus |

| 15 | BpHSFB2b | C1579H2492N454O528S6 | 36476.24 | 4.64 | 54.29 | 74.85 | -0.702 | Nucleus |

| 16 | BpHSFB3 | C1013H1615N293O316S10 | 23275.34 | 8.61 | 58.36 | 64.75 | -0.766 | Nucleus |

| 17 | BpHSFB4a | C1583H2405N441O469S10 | 35438.78 | 7.31 | 57.09 | 64.90 | -0.708 | Nucleus |

| 18 | BpHSFB4b | C1718H2657N475O508S13 | 38510.65 | 8.20 | 60.45 | 74.93 | -0.462 | Nucleus |

| 19 | BpHSFC1a | C1602H2508N446O496S19 | 36561.37 | 5.29 | 68.69 | 66.41 | -0.550 | Nucleus |

| 20 | BpHSFC1b | C1139H1770N310O349S15 | 25871.35 | 5.76 | 54.05 | 67.00 | -0.340 | Nucleus |

| 21 | BpHSFC1c | C822H1226N216O267S9 | 18694.60 | 4.34 | 55.65 | 53.63 | -0.351 | Nucleus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).