Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Abiotic-Stress Treatments in Carthamus Tinctorius L.

2.2. Identification of C2H2 Genes

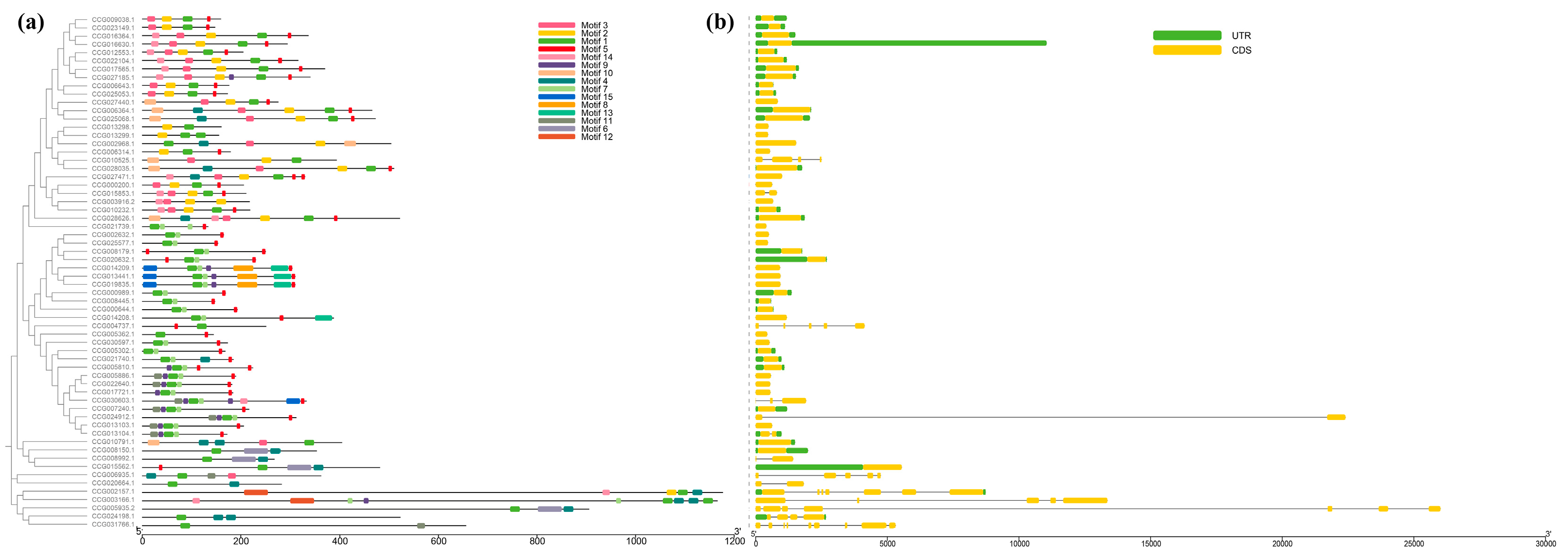

2.3. Motifs and Gene Structure of the CtC2H2-ZFPs

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of CtC2H2 Genes

2.5. Cis-Elements Analysis in CtC2H2 Promoters

2.6. GO Functional Annotation Analysis of CtC2H2 Genes

2.7. RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

2.8. Tissue-Specific CtC2H2 Gene Expression and Validation

2.9. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content and Detection of Key Flavonoid-Biosynthetic Genes

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of CtC2H2 Gene and Analysis of Physicochemical Properties

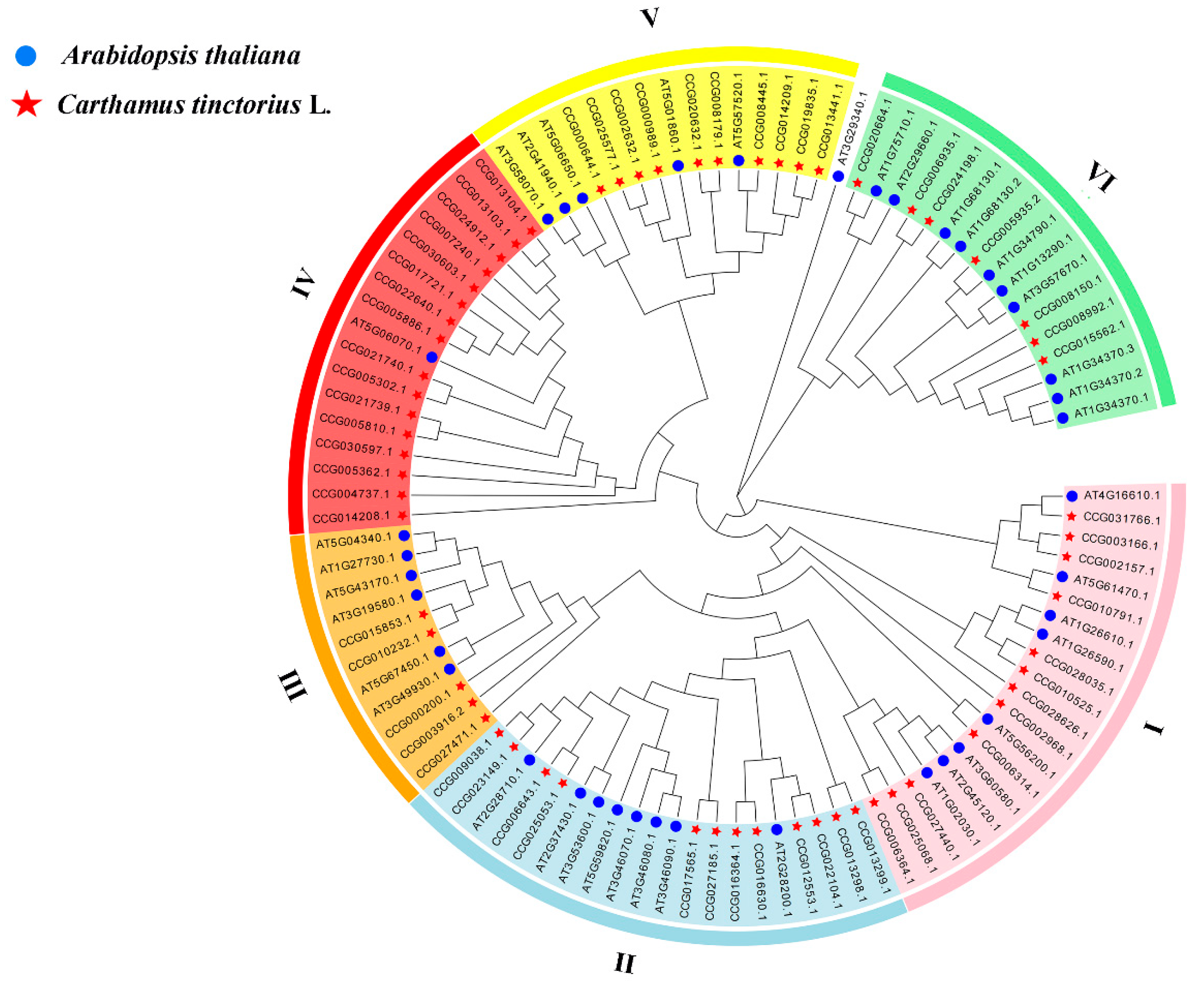

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

3.3. Cis-Acting Elements of the CtC2H2-ZFPs

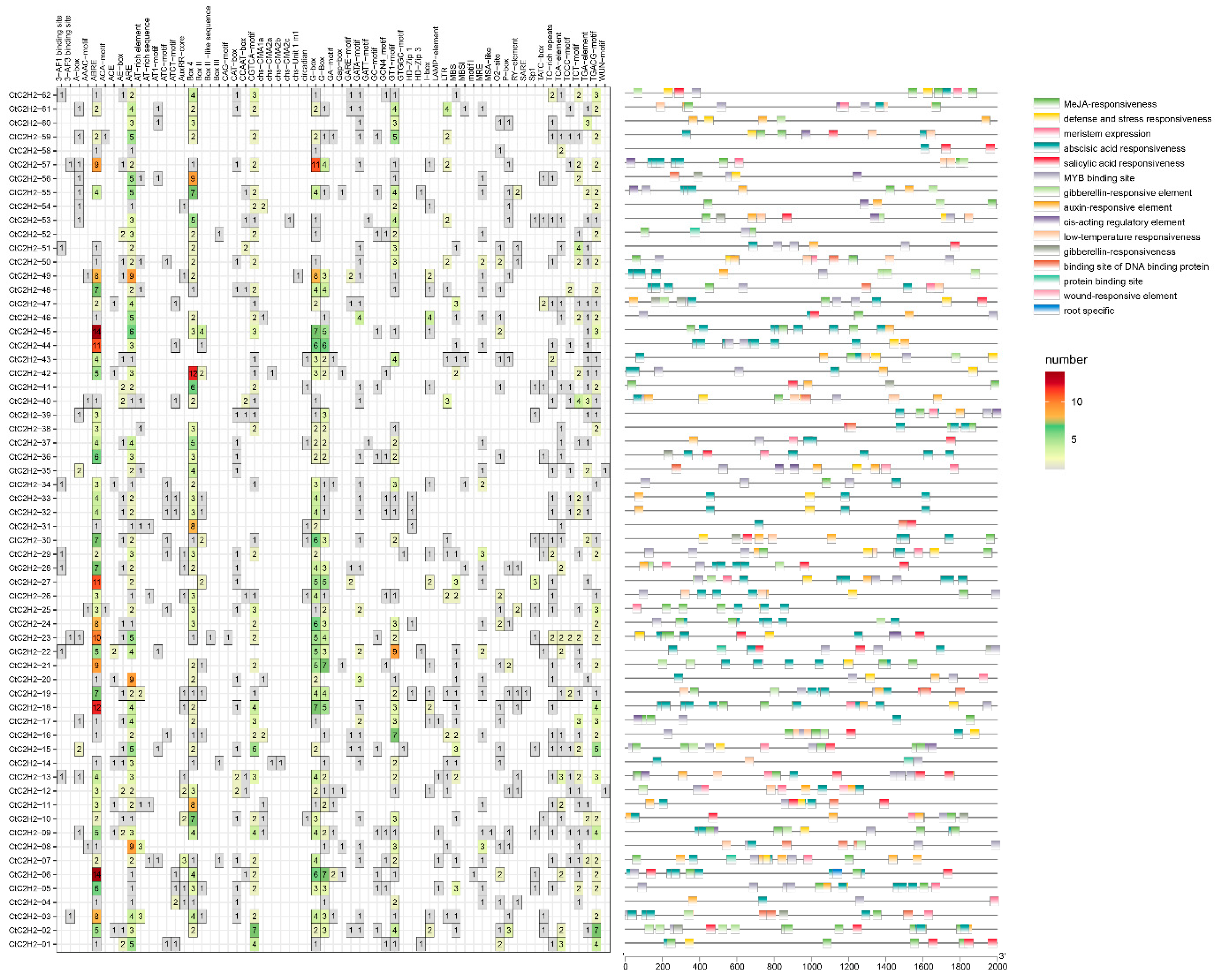

3.4. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements of Gene Promoters

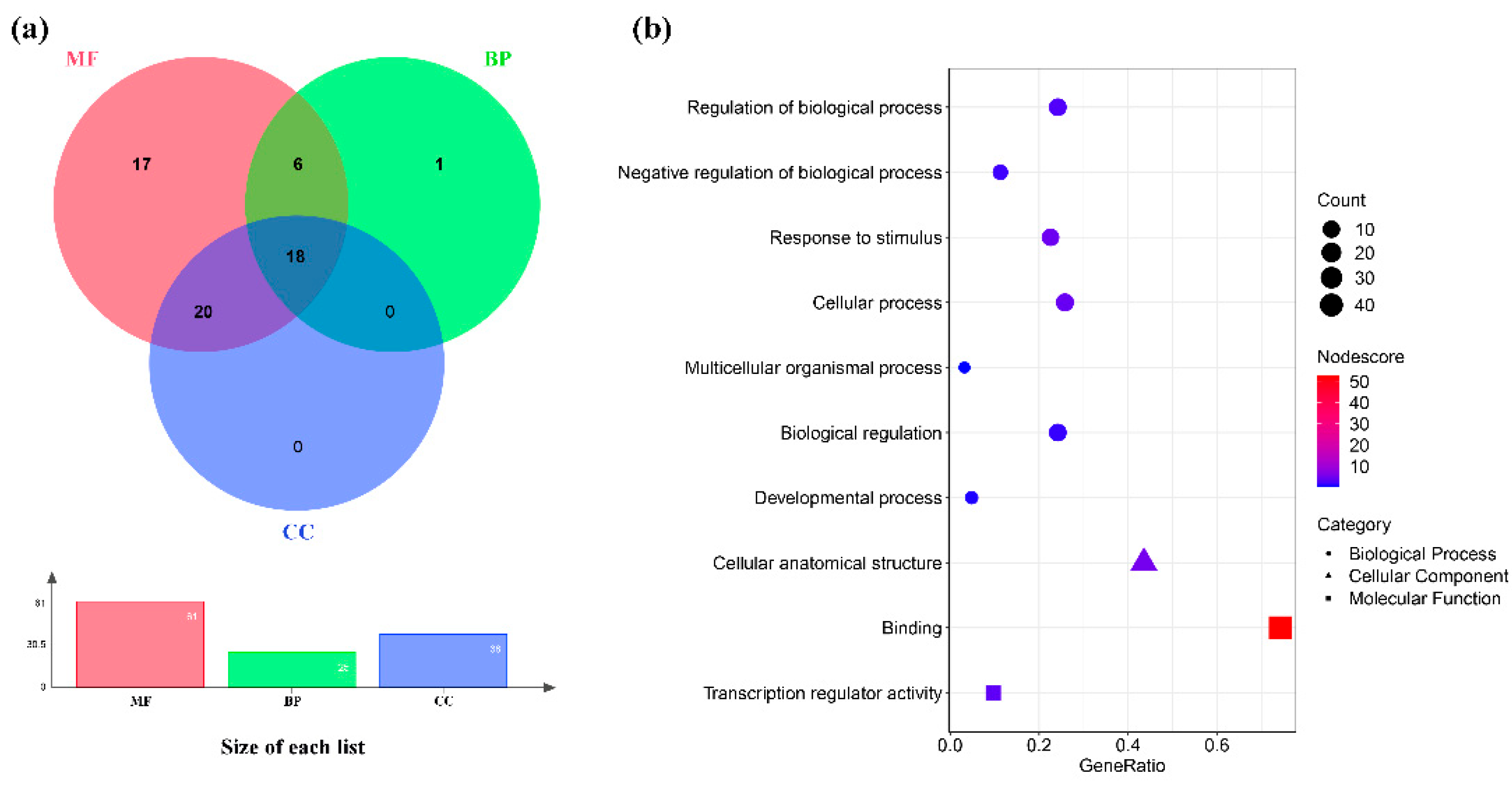

3.5. Functional Categorization and Annotation Enrichment of CtC2H2 Gene Family

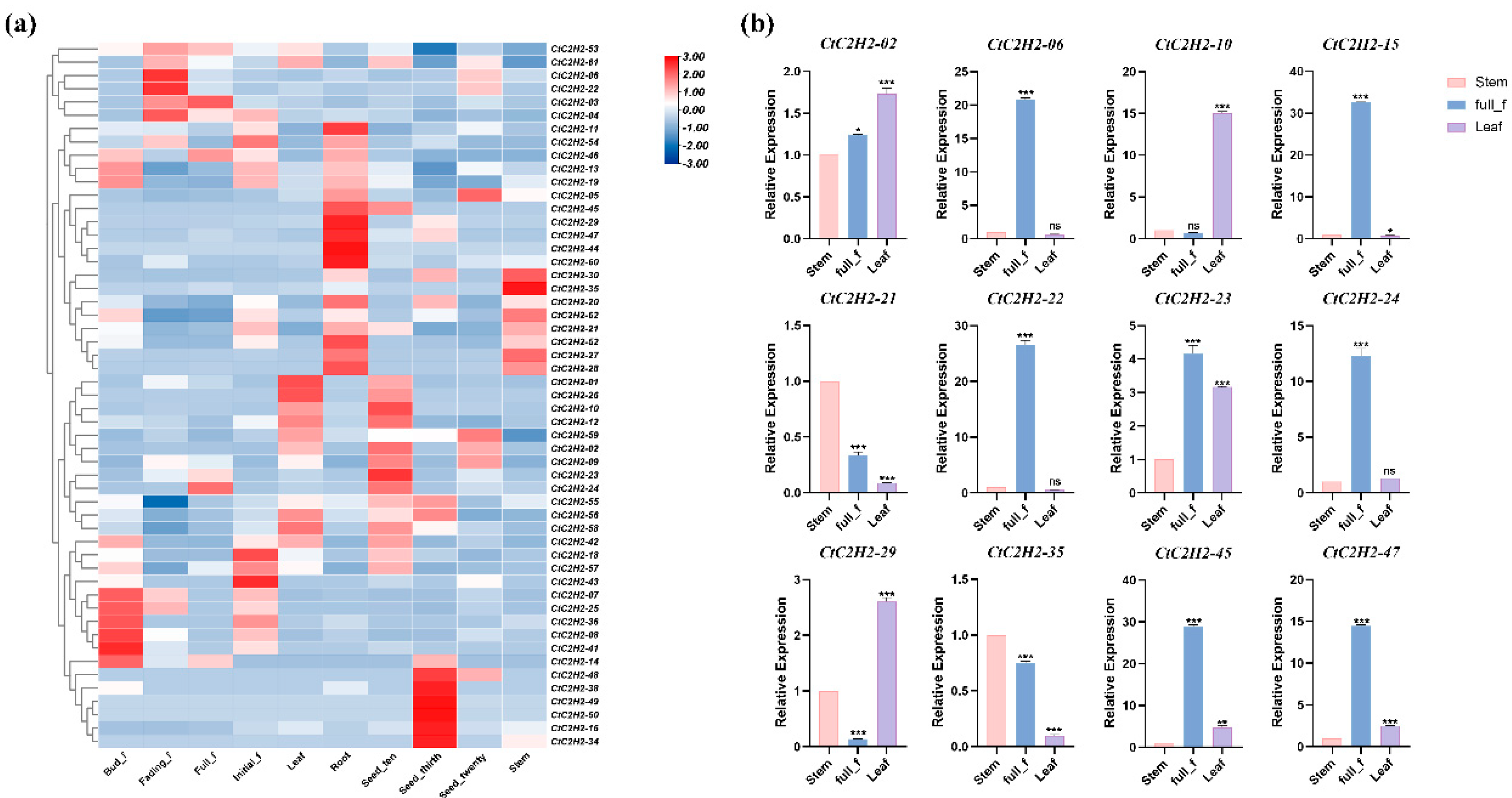

3.6. Tissue-Specific Expression Analysis of C2H2 Family Genes in Safflower

3.7. Cold Stress Triggers Differential and Dynamic Regulation of CtC2H2-ZFPs

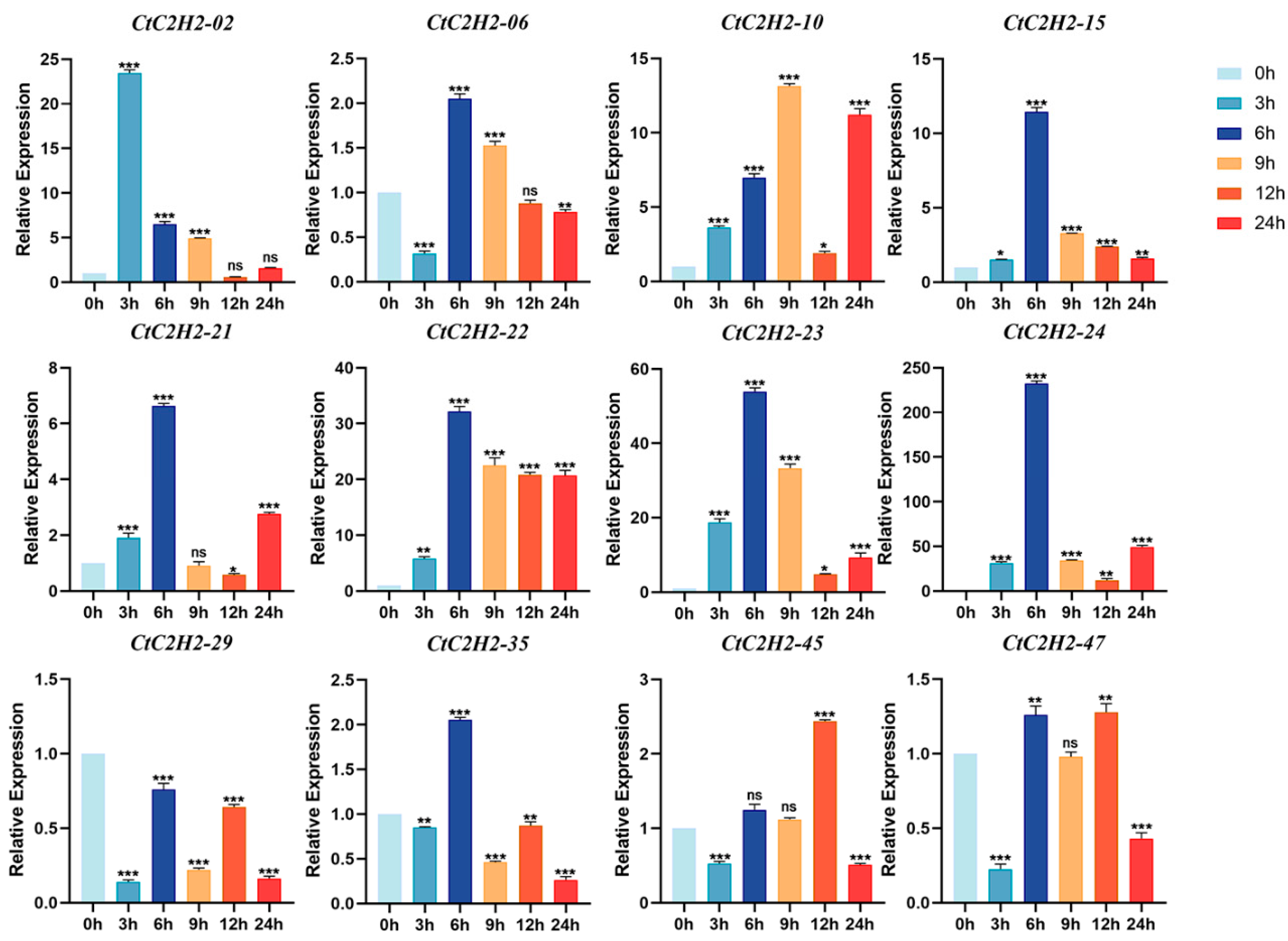

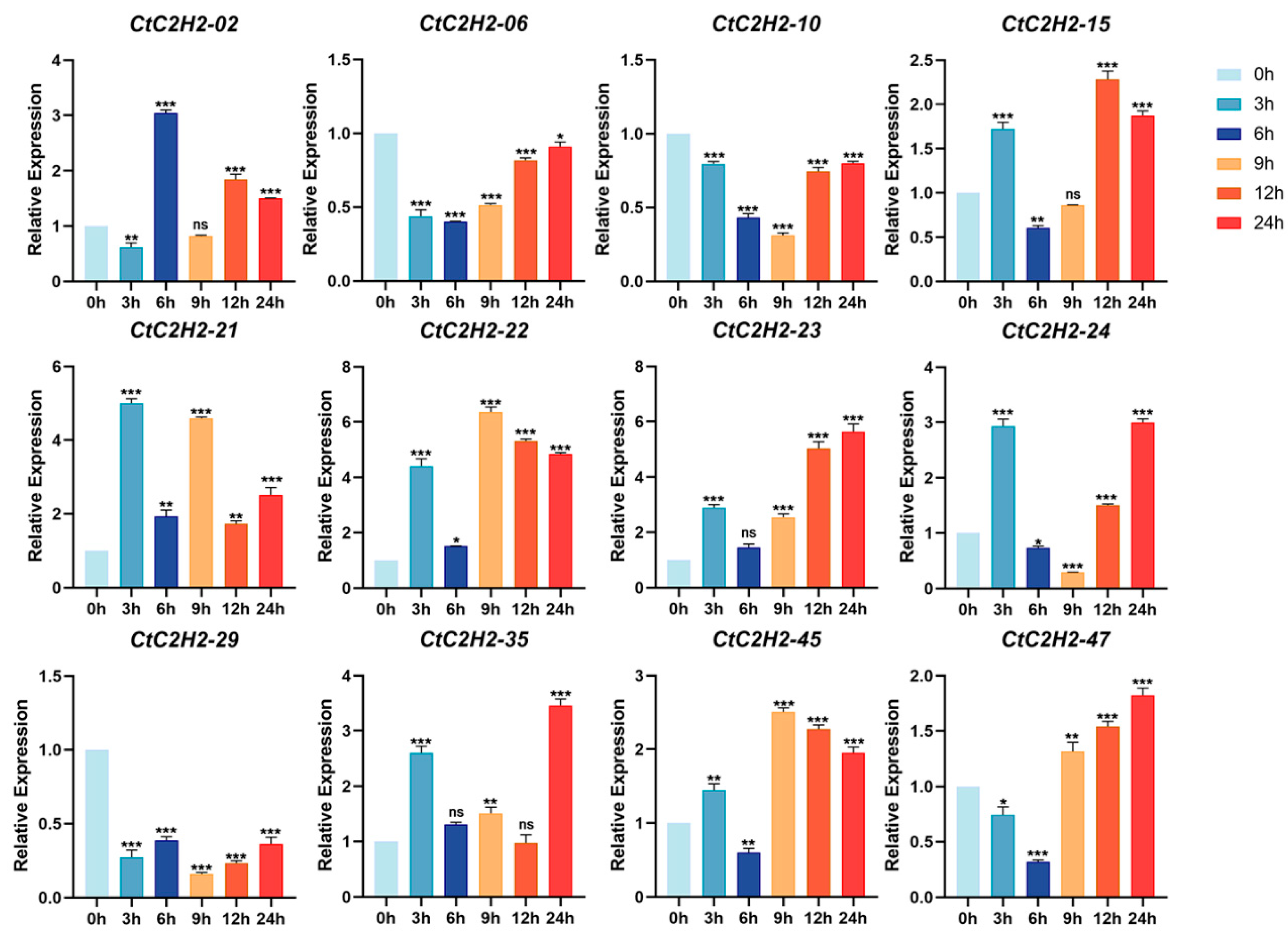

3.8. Differential Expression Responses of CtC2H2-ZFP Genes to ABA and ABA+MeJA Treatments

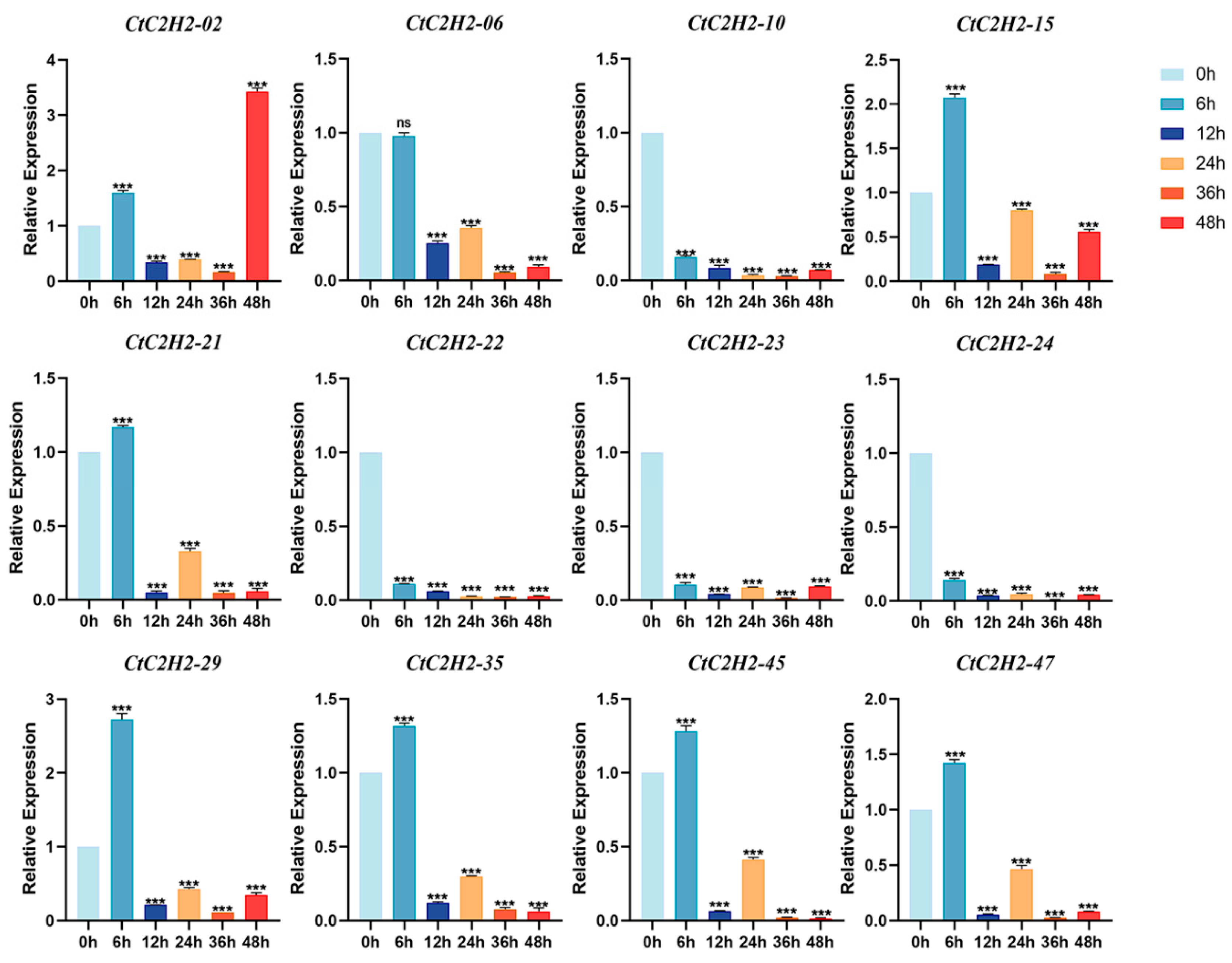

3.9. CtC2H2-ZFPs Exhibit Distinct Suppressed and Fluctuating Expression Profiles Under UV-B Exposure

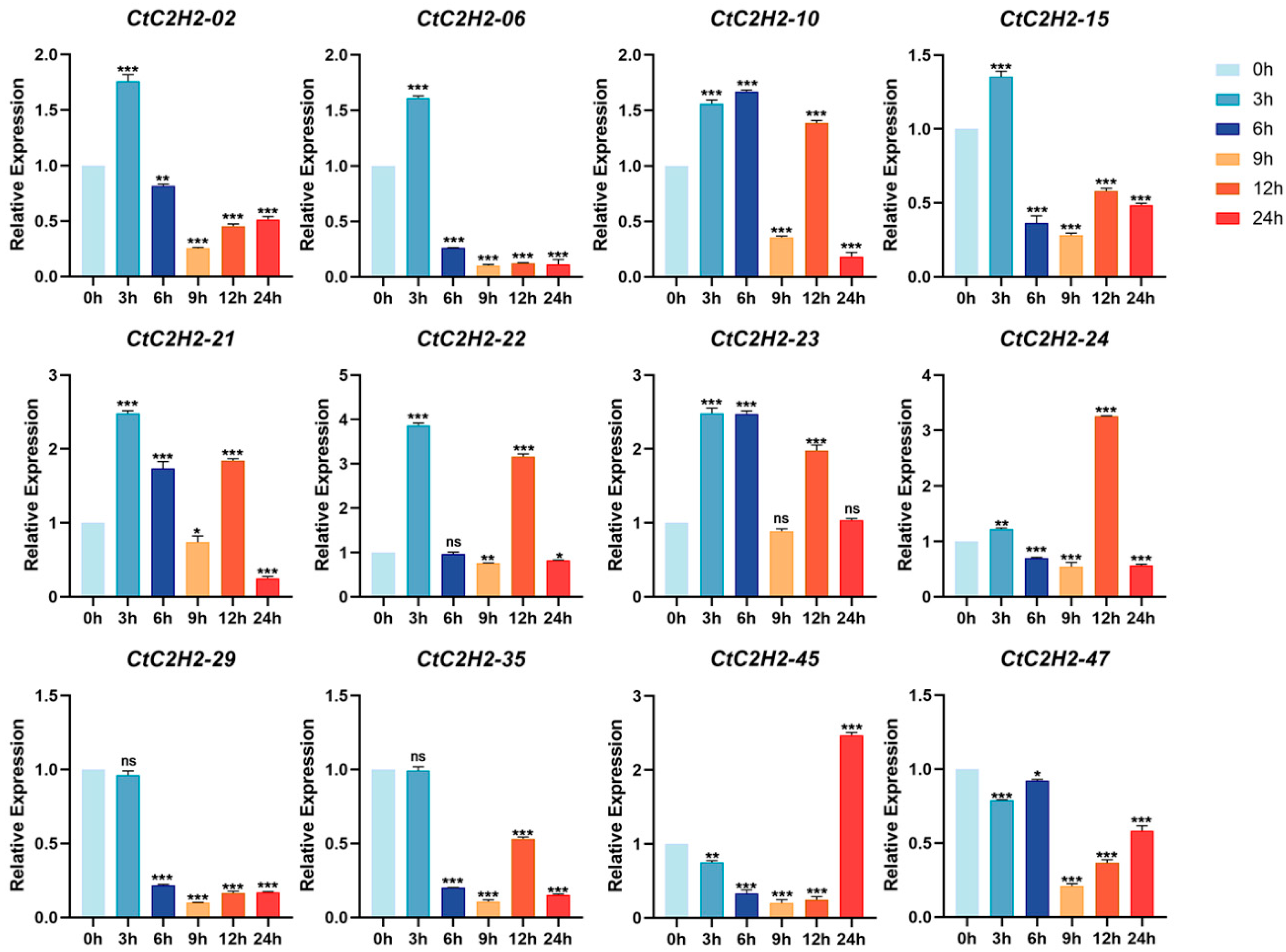

3.10. Distinct and Complex Expression Profiles of CtC2H2-ZFPs Under MeJA Stress

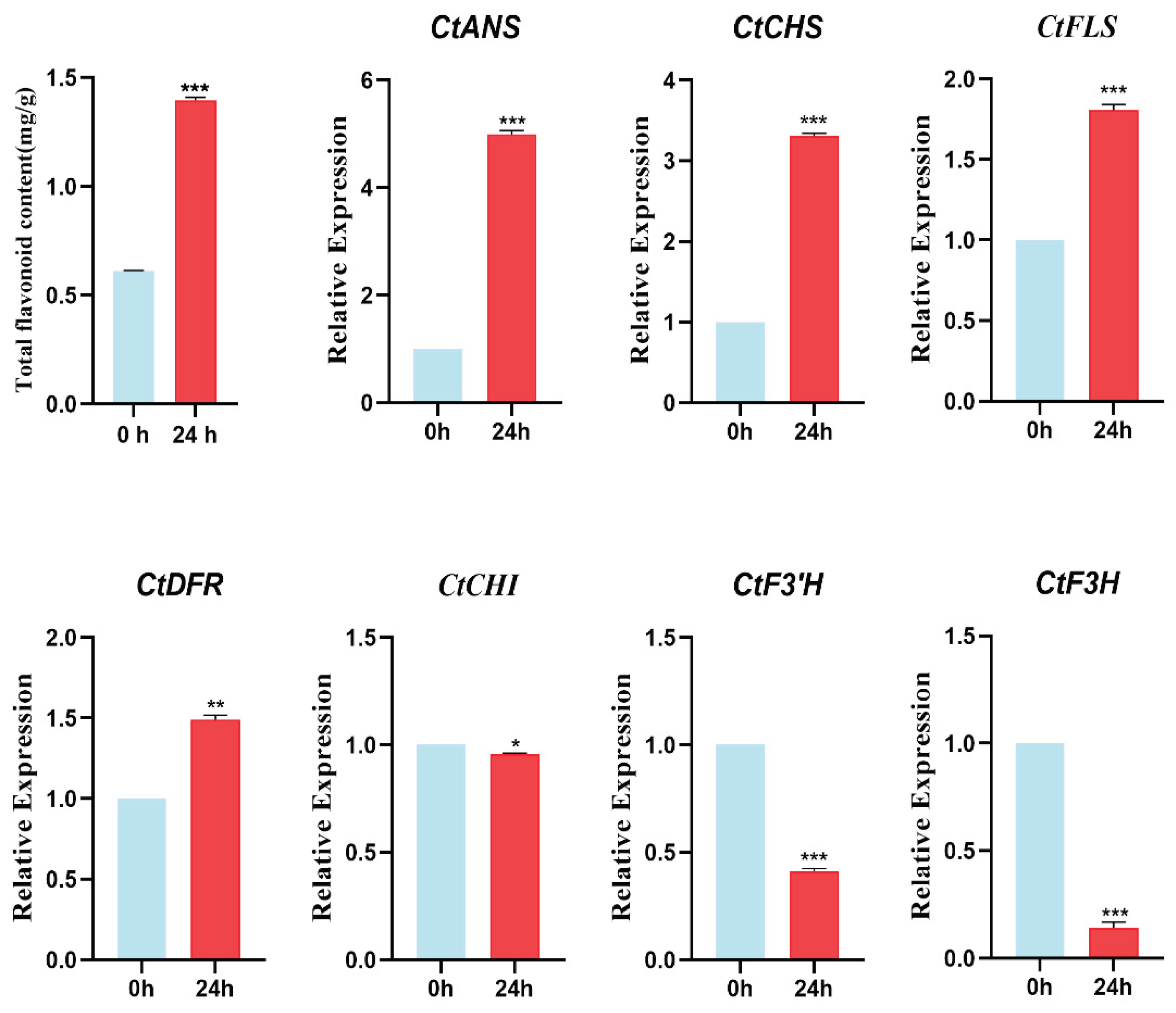

3.11. Changes in Total Flavonoids Content and Key Genes of the Flavonoid Pathway Under ABA Treatment

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alshareef, N.S.; AlSedairy, S.A.; Al-Harbi, L.N.; Alshammari, G.M.; Yahya, M.A. Carthamus tinctorius L. (Safflower) Flower Extract Attenuates Hepatic Injury and Steatosis in a Rat Model of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus via Nrf2-Dependent Hypoglycemic, Antioxidant, and Hypolipidemic Effects. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, C.; Fang, R.; Xu, Y.; Li, K.; Ai, T.; Wan, J.; Qin, Y.; Lyu, X.; Liu, H.; Qin, R.; et al. Safflower petal water-extract consumption reduces blood glucose via modulating hepatic gluconeogenesis and gut microbiota. Journal of Functional Foods 2024, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetti, T.; Morresi, C.; Bellachioma, L.; Ferretti, G. Antioxidant and Pro-Oxidant Properties of Carthamus Tinctorius, Hydroxy Safflor Yellow A, and Safflor Yellow A. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Si, N.; Ma, Y.; Ge, D.; Yu, X.; Fan, A.; Wang, X.; Hu, J.; Wei, P.; Ma, L.; et al. Hydroxysafflor-Yellow A Induces Human Gastric Carcinoma BGC-823 Cell Apoptosis by Activating Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma (PPARγ). Med Sci Monit 2018, 24, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, Z.; Ma, C.; Tian, J.; Fu, F.; Li, C.; Guo, D.; Roeder, E.; Liu, K. Neuroprotective effects of hydroxysafflor yellow A: in vivo and in vitro studies. Planta Med 2003, 69, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, B.; Wang, R.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, Q.; Chen, C.; Xi, Z.; et al. Comprehensive review of two groups of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius L. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 153. [CrossRef]

- Petrussa, E.; Braidot, E.; Zancani, M.; Peresson, C.; Bertolini, A.; Patui, S.; Vianello, A. Plant flavonoids--biosynthesis, transport and involvement in stress responses. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 14950–14973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; McLachlan, A.D.; Klug, A. Repetitive zinc-binding domains in the protein transcription factor IIIA from Xenopus oocytes. Embo j 1985, 4, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielbowicz-Matuk, A. Involvement of plant C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub>-type zinc finger transcription factors in stress responses. Plant Science 2012, 185, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Shi, Y. The galvanization of biology: a growing appreciation for the roles of zinc. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1996, 271, 1081–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuji, H. Zinc-finger proteins: the classical zinc finger emerges in contemporary plant science. Plant Mol Biol 1999, 39, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftci-Yilmaz, S.; Morsy, M.R.; Song, L.; Coutu, A.; Krizek, B.A.; Lewis, M.W.; Warren, D.; Cushman, J.; Connolly, E.L.; Mittler, R. The EAR-motif of the Cys2/His2-type zinc finger protein Zat7 plays a key role in the defense response of Arabidopsis to salinity stress. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 9260–9268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittler, R.; Kim, Y.; Song, L.; Coutu, J.; Coutu, A.; Ciftci-Yilmaz, S.; Lee, H.; Stevenson, B.; Zhu, J.K. Gain- and loss-of-function mutations in Zat10 enhance the tolerance of plants to abiotic stress. FEBS Lett 2006, 580, 6537–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, T.; Cao, J. Cys₂/His₂ Zinc-Finger Proteins in Transcriptional Regulation of Flower Development. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riechmann, J.L.; Heard, J.; Martin, G.; Reuber, L.; Jiang, C.; Keddie, J.; Adam, L.; Pineda, O.; Ratcliffe, O.J.; Samaha, R.R.; et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science 2000, 290, 2105–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Li, M.; Mao, P.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z. Genome-Wide Identification of the Q-type C2H2 Transcription Factor Family in Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and Expression Analysis under Different Abiotic Stresses. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Pan, Y. Genome-wide identification of C2H2 zinc-finger genes and their expression patterns under heat stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). PeerJ 2019, 7, e7929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Hou, Q.; Yu, R.; Deng, H.; Shen, L.; Wang, Q.; Wen, X. Genome-wide analysis of C2H2 zinc finger family and their response to abiotic stresses in apple. Gene 2024, 904, 148164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Arora, R.; Ray, S.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, V.P.; Takatsuji, H.; Kapoor, S.; Tyagi, A.K. Genome-wide identification of C2H2 zinc-finger gene family in rice and their phylogeny and expression analysis. Plant Mol Biol 2007, 65, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Mahanty, B.; Mishra, R.; Joshi, R.K. Genome wide identification and expression analysis of pepper C(2)H(2) zinc finger transcription factors in response to anthracnose pathogen Colletotrichum truncatum. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, R.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, X.; He, Y.; He, Y.; et al. Genome-wide characterization of the C2H2 zinc-finger genes in Cucumis sativus and functional analyses of four CsZFPs in response to stresses. BMC Plant Biol 2020, 20, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Coulter, J.A.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Meng, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the Q-type C2H2 gene family in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 153, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, L.; Pan, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, L.; Han, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, S.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of the C2H2 zinc finger protein gene family and its response to salt stress in ginseng, Panax ginseng Meyer. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 10165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zeng, L.; Xu, Y.; Jin, Q.; Wang, Y. Genome-wide identification of the Q-type C2H2 zinc finger protein gene family and expression analysis under abiotic stress in lotus (Nelumbo nucifera G.). BMC Genomics 2024, 25, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, A.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Hou, F.; Zhang, L. Genome-wide identification of the C2H2 zinc finger gene family and expression analysis under salt stress in sweetpotato. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1301848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Niu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Gao, C.; Zhu, M.; Bai, J.; Liu, M.; He, L.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; et al. The C(2) H(2) -type zinc finger transcription factor OSIC1 positively regulates stomatal closure under osmotic stress in poplar. Plant Biotechnol J 2023, 21, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, R.; Hu, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Xue, R.; Wu, M.; Li, H. Overexpression of wheat C2H2 zinc finger protein transcription factor TaZAT8-5B enhances drought tolerance and root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 2024, 260, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Li, C.Y.; An, J.P.; Wang, D.R.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.K.; You, C.X. The C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor MdZAT10 negatively regulates drought tolerance in apple. Plant Physiol Biochem 2021, 167, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Lu, C.; Guo, J.; Qiao, Z.; Sui, N.; Qiu, N.; Wang, B. C2H2 Zinc Finger Proteins: Master Regulators of Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, S.R. Accelerated Profile HMM Searches. PLoS Comput Biol 2011, 7, e1002195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, W39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, B.; Gao, S.; Lercher, M.J.; Hu, S.; Chen, W.H. Evolview v3: a webserver for visualization, annotation, and management of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, W270–w275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Organization of cis-acting regulatory elements in osmotic- and cold-stress-responsive promoters. Trends Plant Sci 2005, 10, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, A.; Götz, S.; García-Gómez, J.M.; Terol, J.; Talón, M.; Robles, M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3674–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, S.; García-Gómez, J.M.; Terol, J.; Williams, T.D.; Nagaraj, S.H.; Nueda, M.J.; Robles, M.; Talón, M.; Dopazo, J.; Conesa, A. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36, 3420–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. MSOR connections 2014, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ginestet, C. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series a-Statistics in Society 2011, 174, 245–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untergasser, A.; Cutcutache, I.; Koressaar, T.; Ye, J.; Faircloth, B.C.; Remm, M.; Rozen, S.G. Primer3--new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol 2002, 3, Research0034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortazavi, A.; Williams, B.A.; McCue, K.; Schaeffer, L.; Wold, B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods 2008, 5, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Paje, L.A.; Kim, M.J.; Jang, S.H.; Kim, J.T.; Lee, S. Validation of an optimized HPLC–UV method for the quantification of formononetin and biochanin A in Trifolium pratense extract. Applied Biological Chemistry 2021, 64, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, W585–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Cao, Y.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, Y.; Chen, X.; He, C.; Fan, X.; Zheng, X.; et al. Chemical Constituents from the Flowers of Carthamus tinctorius L. and Their Lung Protective Activity. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Li, C.-Y.; An, J.-P.; Wang, D.-R.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.-K.; You, C.-X. The C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor MdZAT10 negatively regulates drought tolerance in apple. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2021, 167, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu Yi-jie, X.U.E.Y.-c. The Research Progress of Flavonoids in Plants. China Biotechnology 2016, 36, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lv, S.; Zhao, L.; Gao, T.; Yu, C.; Hu, J.; Ma, F. Advances in the study of the function and mechanism of the action of flavonoids in plants under environmental stresses. Planta 2023, 257, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agati, G.; Brunetti, C.; Di Ferdinando, M.; Ferrini, F.; Pollastri, S.; Tattini, M. Functional roles of flavonoids in photoprotection: new evidence, lessons from the past. Plant Physiol Biochem 2013, 72, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, M.; Kumeda, S.; Komai, K. Insect antifeedant flavonoids from Gnaphalium affine D. Don. J Agric Food Chem 2000, 48, 1888–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, R.; Khan, M.-A.; Asaf, S.; Lubna; Waqas, M.; Park, J.-R.; Asif, S.; Kim, N.; Lee, I.-J.; Kim, K.-M. Drought and UV Radiation Stress Tolerance in Rice Is Improved by Overaccumulation of Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Flavonoids. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Yuan, L.; Luo, Y.; Jing, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhu, G. A freezing responsive UDP-glycosyltransferase improves potato freezing tolerance via modifying flavonoid metabolism. Horticultural Plant Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritonga, F.N.; Ngatia, J.N.; Wang, Y.; Khoso, M.A.; Farooq, U.; Chen, S. AP2/ERF, an important cold stress-related transcription factor family in plants: A review. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2021, 27, 1953–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, E.; Janjua, N.K.; Ahmed, S.; Murtaza, I.; Ali, T.; Hameed, S. Radical scavenging propensity of Cu2+, Fe3+ complexes of flavonoids and in-vivo radical scavenging by Fe3+-primuletin. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2017, 171, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, C.; Luo, K. Biosynthesis and metabolic engineering of isoflavonoids in model plants and crops: a review. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15, 1384091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).