Submitted:

15 January 2026

Posted:

16 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

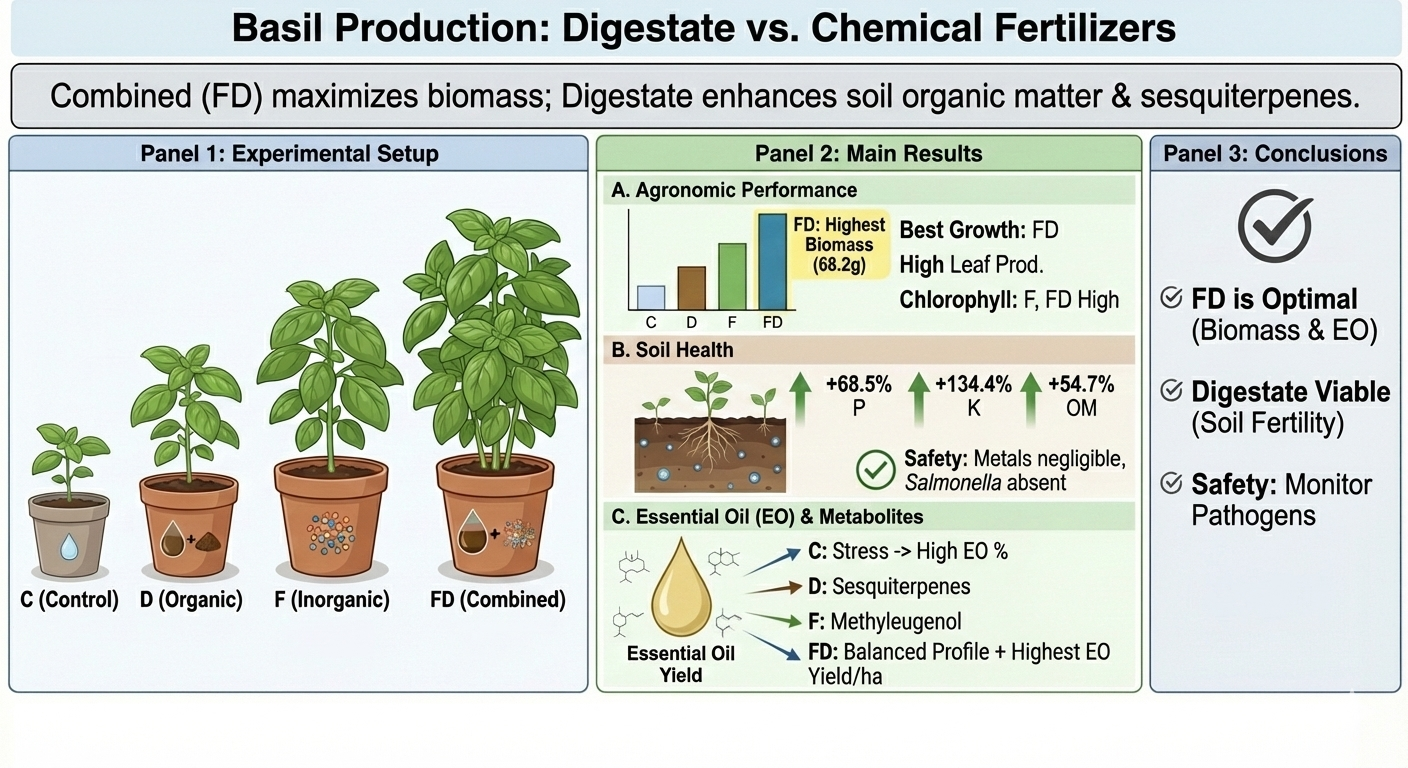

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Experimental Design

2.2. Environmental Conditions

2.3. Growth and Physiological Parameters

2.3.1. Growth Parameters

2.3.2. Physiological Parameters

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.4.1. Analytical Methods for Physicochemical and Microbiological Characteristics

2.4.2. GC-MS/FID Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physiological Parameters

3.2. Essential Oil Production and Composition

3.3. Soil Properties

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferreira, C.S.S.; Keesstra, S.; Destouni, G.; Solomun, M.K.; Kalantari, Z. Soil Degradation in the Mediterranean Region: Drivers and Future Trends. In Environmental Sustainability in the Mediterranean Region: Challenges and Solutions; Ferreira, C.S.S., Destouni, G., Kalantari, Z., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp. 81–112. ISBN 978-3-031-64503-7. [Google Scholar]

- Seker, M.; Gumus, V. Projection of Temperature and Precipitation in the Mediterranean Region through Multi-Model Ensemble from CMIP6. Atmos. Res. 2022, 280, 106440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopnarain, A.; Akindolire, M.A.; Rama, H.; Ndaba, B. Casting Light on the Micro-Organisms in Digestate: Diversity and Untapped Potential. Fermentation 2023, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranagal, J.; Ligęza, S.; Gmitrowicz-Iwan, J. The Impact of Mining Waste and Biogas Digestate Addition on the Durability of Soil Aggregates. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holatko, J.; Brtnicky, M.; Mustafa, A.; Kintl, A.; Skarpa, P.; Ryant, P.; Baltazar, T.; Malicek, O.; Latal, O.; Hammerschmiedt, T. Effect of Digestate Modified with Amendments on Soil Health and Plant Biomass under Varying Experimental Durations. Materials 2023, 16, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didelot, A.-F.; Jardé, E.; Morvan, T.; Gaillard, F.; Liotaud, M.; Jaffrezic, A. Effects of Biogas Digestate and Winter Crops on Dissolved Organic Carbon and Nitrates Fluxes in Soil. Copernicus Meetings: EGU General Assembly 2023, Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Seruga, P.; Krzywonos, M.; Paluszak, Z.; Urbanowska, A.; Pawlak-Kruczek, H.; Niedźwiecki, Ł.; Pińkowska, H. Pathogen Reduction Potential in Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste and Food Waste. Molecules 2020, 25, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.; Chen, Y.; Ndegwa, P. Anaerobic Digestion Process Deactivates Major Pathogens in Biowaste: A Meta-Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 153, 111752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraturo, F.; Panico, A.; Giordano, A.; Libralato, G.; Aliberti, F.; Galdiero, E.; Guida, M. Hygienic Assessment of Digestate from a High Solids Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Sewage Sludge with Biowaste by Testing Salmonella Typhimurium, Escherichia Coli and SARS-CoV-2. Environ. Res. 2022, 206, 112585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejna, M.; Gottardo, D.; Baldi, A.; Dell’Orto, V.; Cheli, F.; Zaninelli, M.; Rossi, L. Review: Nutritional Ecology of Heavy Metals. Animal 2018, 12, 2156–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derehajło, S.; Tymińska, M.; Skibko, Z.; Borusiewicz, A.; Romaniuk, W.; Kuboń, M.; Olech, E.; Koszel, M. Heavy Metal Content in Substrates in Agricultural Biogas Plants. Agric. Eng. 2023, 27, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Dong, Y.; Jia, Q.; Wu, S.; Bai, J.; Cui, C.; Li, Y.; Zou, P.; An, M.; Du, X.; et al. Hazards of Toxic Metal(Loid)s: Exploring the Ecological and Health Risk in Soil–Crops Systems with Long-Term Sewage Sludge Application. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunta, F.; Schillaci, C.; Panagos, P.; Van Eynde, E.; Wojda, P.; Jones, A. Ecological Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals from Application of Sewage Sludge on Agricultural Soils in Europe. Eur. J. of Soil Sci. 2024, 75, e13562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra Caracciolo, A.; Bustamante, M.A.; Nogues, I.; Di Lenola, M.; Luprano, M.L.; Grenni, P. Changes in Microbial Community Structure and Functioning of a Semiarid Soil Due to the Use of Anaerobic Digestate Derived Composts and Rosemary Plants. Geoderma 2015, 245–246, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronga, D.; Pellati, F.; Brighenti, V.; Laudicella, K.; Laviano, L.; Fedailaine, M.; Benvenuti, S.; Pecchioni, N.; Francia, E. Testing the Influence of Digestate from Biogas on Growth and Volatile Compounds of Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.) and Peppermint (Mentha x Piperita L.) in Hydroponics. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2018, 11, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, T.S.; Weekes, M.-A.; Browne, D.-M.; Holder, N. The Effect of Anaerobic Digestate Tea on the Growth of Lemon Grass. Biofuel. Bioprod. Biorefin. 2023, 17, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calamai, A.; Palchetti, E.; Masoni, A.; Marini, L.; Chiaramonti, D.; Dibari, C.; Brilli, L. The Influence of Biochar and Solid Digestate on Rose-Scented Geranium (Pelargonium Graveolens L’Hér.) Productivity and Essential Oil Quality. Agronomy 2019, 9, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindisi, L.J.; Simon, J.E. Preharvest and Postharvest Techniques That Optimize the Shelf Life of Fresh Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.): A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizah, N.S.; Irawan, B.; Kusmoro, J.; Safriansyah, W.; Farabi, K.; Oktavia, D.; Doni, F.; Miranti, M. Sweet Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.)―A Review of Its Botany, Phytochemistry, Pharmacological Activities, and Biotechnological Development. Plants 2023, 12, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, W.M.F.; Kringel, D.H.; de Souza, E.J.D.; da Rosa Zavareze, E.; Dias, A.R.G. Basil Essential Oil: Methods of Extraction, Chemical Composition, Biological Activities, and Food Applications. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzidis, A.; Mitraka, G.-C.; Katsantonis, D.; Singh, A.; Prasad, S.; Koutroubas, S.; Kougias, P.; Korres, N.E. Enhancing Methane Production from Rice Crop Residues via Pretreatment and Co-Digestion with Cattle or Swine Slurry. Front. Energy Res. 2026, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufalo, J.; Cantrell, C.L.; Astatkie, T.; Zheljazkov, V.D.; Gawde, A.; Boaro, C.S.F. Organic versus Conventional Fertilization Effects on Sweet Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.) Growth in a Greenhouse System. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 74, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, E.A.; Ferguson, B.J.; Beveridge, C.A. Apical Dominance and Shoot Branching. Divergent Opinions or Divergent Mechanisms? Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd edition; American Public Health Association (APHA): Washington, DC, 2017; ISBN 978-0-87553-287-5.

- McGeorge, W.T. Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkaline Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1954, 18, 348–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midorikawa, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Phetsouvanh, R.; Midorikawa, K. Detection of Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Using a Mechanism for Controlling Hydrogen Sulfide Production. Open J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 04, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanetz, L.W.; Bartley, C.H. Numbers of Enterococci in Water, Sewage, AND Feces Determined by the Membrane Filter Technique with an Improved Medium. J. Bacteriol. 1957, 74, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 16193:2013; Sludge, Treated Biowaste and Soil - Detection and Enumeration of Escherichia Coli. 2013.

- Sarrou, E.; Martinidou, E.; Palmieri, L.; Poulopoulou, I.; Trikka, F.; Masuero, D.; Matthias, G.; Ganopoulos, I.; Chatzopoulou, P.; Martens, S. High Throughput Pre-Breeding Evaluation of Greek Oregano (Origanum Vulgare L. Subsp. Hirtum) Reveals Multi-Purpose Genotypes for Different Industrial Uses. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2023, 37, 100516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, RP. Identification of Essential Oils by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. In Allured Pub., USA; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Asp, H.; Bergstrand, Karl-Johan; Caspersen, Siri; Hultberg, M. Anaerobic Digestate as Peat Substitute and Fertiliser in Pot Production of Basil. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2022, 38, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yang, S.; Luan, C.; Wu, Q.; Lin, L.; Li, X.; Che, Z.; Zhou, D.; Dong, Z.; Song, H. Partial Organic Substitution for Synthetic Fertilizer Improves Soil Fertility and Crop Yields While Mitigating N2O Emissions in Wheat-Maize Rotation System. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 154, 127077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, I.; Paungfoo-Lonhienne, C.; Tahmasbian, I.; Hunter, B.; Smith, B.; Mayer, D.; Redding, M. Combination of Inorganic Nitrogen and Organic Soil Amendment Improves Nitrogen Use Efficiency While Reducing Nitrogen Runoff. Nitrogen 2022, 3, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yuan, Y.; Shimizu, N.; Magaña, J.; Gong, P.; Na, R. Impact of Organic Fertilization by the Digestate from By-Product on Growth, Yield and Fruit Quality of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicon) and Soil Properties under Greenhouse and Field Conditions. Chem. biol. technol. agric. 2023, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekiya, A.O.; Ande, O.T.; Dahunsi, S.O.; Ogunwole, J. Sole and Combined Application of Biodigestate, N, P, and K Fertilizers: Impacts on Soil Chemical Properties and Maize Performance. Sci. World J. 2024, 2024, 6685906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamison, J.; Khanal, S.K.; Nguyen, N.H.; Deenik, J.L. Assessing the Effects of Digestates and Combinations of Digestates and Fertilizer on Yield and Nutrient Use of Brassica Juncea (Kai Choy). Agronomy 2021, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brychkova, G.; McGrath, A.; Larkin, T.; Goff, J.; McKeown, P.C.; Spillane, C. Use of Anaerobic Digestate to Substitute Inorganic Fertilisers for More Sustainable Nitrogen Cycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 446, 141016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgutis, L.; Šlepetienė, A.; Šlepetys, J.; Cesevičienė, J. Towards a Full Circular Economy in Biogas Plants: Sustainable Management of Digestate for Growing Biomass Feedstocks and Use as Biofertilizer. Energies 2021, 14, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sanz-Garrido, C.; Revuelta-Aramburu, M.; Santos-Montes, A.M.; Morales-Polo, C. A Review on Anaerobic Digestate as a Biofertilizer: Characteristics, Production, and Environmental Impacts from a Life Cycle Assessment Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, A.M.; Delgado, A.; Anjos, O.; Horta, C. Digestate Not Only Affects Nutrient Availability but Also Soil Quality Indicators. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorine, D.; Céline, D.; Caroline, L.M.; Frédéric, B.; Lorette, H.; Julie, B.; Laure, M.; Christine, Z.; Typhaine, P.; Sandra, R.; et al. Influence of Operating Conditions on the Persistence of E. Coli, Enterococci, Clostridium Perfringens and Clostridioides Difficile in Semi-Continuous Mesophilic Anaerobic Reactors. Waste Manag. 2021, 134, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, B.P.; Gogoi, P.K.; Sarma, A.; Ch, I.; Barua, R. Effect of Integrated Nutrient Management and Different Plant Spacing on Tulsi. Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci. 2018, 7, 1352–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, S.; Desai, B.S.; Jha, S.K.; Sinha, S.K.; Patel, D.P.; Kumar, N. Role of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers in Enhancing Biomass Yield and Eugenol Content of Ornamental Basil (Ocimum Gratissimum L.). Heliyon 2024, 10, e30928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordi, S.; Salmasi, S.Z.; Kolvanagh, J.S.; Weisany, W.; Shannon, D.A. Intercropping System and N2 Fixing Bacteria Can Increase Land Use Efficiency and Improve the Essential Oil Quantity and Quality of Sweet Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alami, M.M.; Guo, S.; Mei, Z.; Yang, G.; Wang, X.; Alami, M.M.; Guo, S.; Mei, Z.; Yang, G.; Wang, X. Environmental Factors on Secondary Metabolism in Medicinal Plants: Exploring Accelerating Factors. Med. Plant Biol. 2024, 3, e016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, T.; Sun, C.; Liu, P.; Chen, J.; Hou, X.; Yu, T.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, L.; et al. Eugenol Improves Salt Tolerance via Enhancing Antioxidant Capacity and Regulating Ionic Balance in Tobacco Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Murtaza, G.; Qian, F.; Li, J.; Zheng, G.; Chen, J.; Xie, J.; Zaman, Q. uz; Deng, G.; et al. Exogenous Application of Limonene Alleviates Drought-Induced Oxidative Stress in Tobacco Plants. Ind. Crops and Prod. 2025, 234, 121639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Baky, R.M.A.; Hashem, Z.S. Eugenol and Linalool: Comparison of Their Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 10, 1860–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenol. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Bethesda (MD), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, R.; Heidari, M. Impact of Drought Stress on Biochemical and Molecular Responses in Lavender (Lavandula Angustifolia Mill.): Effects on Essential Oil Composition and Antibacterial Activity. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, I.C.; de Almeida, A.S.; Sena Filho, J.G. Taxonomic Insights and Its Type Cyclization Correlation of Volatile Sesquiterpenes in Vitex Species and Potential Source Insecticidal Compounds: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burducea, M.; Zheljazkov, V.D.; Dincheva, I.; Lobiuc, A.; Teliban, G.-C.; Stoleru, V.; Zamfirache, M.-M. Fertilization Modifies the Essential Oil and Physiology of Basil Varieties. Ind. Crops and Prod. 2018, 121, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndah, F.; Valolahti, H.; Schollert, M.; Michelsen, A.; Rinnan, R.; Kivimäenpää, M. Influence of Increased Nutrient Availability on Biogenic Volatile Organic Compound (BVOC) Emissions and Leaf Anatomy of Subarctic Dwarf Shrubs under Climate Warming and Increased Cloudiness. Ann. Bot. 2022, 129, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sile, I.; Krizhanovska, V.; Nakurte, I.; Mezaka, I.; Kalane, L.; Filipovs, J.; Vecvanags, A.; Pugovics, O.; Grinberga, S.; Dambrova, M.; et al. Wild-Grown and Cultivated Glechoma Hederacea L.: Chemical Composition and Potential for Cultivation in Organic Farming Conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautela, A.; Chatterjee, R.; Yadav, I.; Kumar, S. A Comprehensive Review on Engineered Microbial Production of Farnesene for Versatile Applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.H.; Nishida, R. Methyl Eugenol: Its Occurrence, Distribution, and Role in Nature, Especially in Relation to Insect Behavior and Pollination. J. Insect. Sci. 2012, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yu, C. GDNDC (v2.0): Modelling Long-Term Soil Acidification of Cropland under Different Fertilization Scenarios. Copernicus Meetings, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, I.; Di Bene, C.; Sandaña, P. Editorial: Strategies to Reduce Fertilizers: How to Maintain Crop Productivity and Profitability in Agricultural Acidic Soils. Front. Soil Sci. 2025, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, M.; Kowalski, Z.; Makara, A. The Possibility of Contamination of Water-Soil Environment as a Result of the Use of Pig Slurry. Ecol. Chem. Eng. 2019, 26, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragályi, P.; Szécsy, O.; Uzinger, N.; Magyar, M.; Szabó, A.; Rékási, M. Factors Influencing the Impact of Anaerobic Digestates on Soil Properties. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschmiedt, T.; Kintl, A.; Holatko, J.; Mustafa, A.; Vitez, T.; Malicek, O.; Baltazar, T.; Elbl, J.; Brtnicky, M. Assessment of Digestates Prepared from Maize, Legumes, and Their Mixed Culture as Soil Amendments: Effects on Plant Biomass and Soil Properties. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F. da Application of Effluent from Anaerobic Digestion of Biomass to Condition the Soil: A Review of the Literature. Rev. Gestão Soc. 2024, 18, e04280–e04280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolka, E.; Wyszkowski, M.; Żołnowski, A.C.; Skorwider-Namiotko, A.; Szostek, R.; Wyżlic, K.; Borowski, M. Digestate from an Agricultural Biogas Plant as a Factor Shaping Soil Properties. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarino, S.H.; McDaniel, M.D.; Blauwet, M.J.; Sievers, B.; Sievers, L.; Schulte, L.A.; Miguez, F.E. Adding Anaerobic Digestate to Commercial Farm Fields Increases Soil Organic Carbon. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, N.; Echereobia, C.; Ahukaemere, C.; Chris-Emenyonu, C.; Obinna, N.; Osisi, A.; Chukwu, E.; Egboka, N. Chemical Fractionation and Bioavailability of Potassium as Affected by Digestate in a Degraded Ultisol under Maize Cultivation. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2023, 69, 3139–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, J.; Ye, J.; Dai, A.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, D.; et al. Long-Term Organic Fertilization Enhances Potassium Uptake and Yield of Sweet Potato by Expanding Soil Aggregates-Associated Potassium Stocks. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 358, 108701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, L.; Carswell, A.; Misselbrook, T.; Shen, J.; Han, J. Fate and Transfer of Heavy Metals Following Repeated Biogas Slurry Application in a Rice-Wheat Crop Rotation. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 270, 110938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldasso, V.; Bonet-Garcia, N.; Sayen, S.; Guillon, E.; Frunzo, L.; Gomes, C.A.R.; Alves, M.J.; Castro, R.; Mucha, A.P.; Almeida, C.M.R. Trace Metal Fate in Soil after Application of Digestate Originating from the Anaerobic Digestion of Non-Source-Separated Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.W.; Lourenzi, C.R.; Comin, J.J.; Loss, A.; Girotto, E.; Ludwig, M.P.; Freiberg, J.A.; de Oliveira Camera, D.; Marchezan, C.; Palermo, N.M.; et al. Effect of Organic and Mineral Fertilizers Applications in Pasture and No-Tillage System on Crop Yield, Fractions and Contaminant Potential of Cu and Zn. Soil Till. Res. 2023, 225, 105523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 Laying down Rules on the Making Available on the Market of EU Fertilising Products and Amending Regulations (EC) No 1069/2009 and (EC) No 1107/2009 and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 2003/2003 (Text with EEA Relevance). 2024.

- Bonetta, S.; Bonetta, S.; Ferretti, E.; Fezia, G.; Gilli, G.; Carraro, E. Agricultural Reuse of the Digestate from Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Organic Waste: Microbiological Contamination, Metal Hazards and Fertilizing Performance. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2014, 225, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhondwa, J.P. Enteropathogens Survivor Load in Digestate from Two-Phase Mesophilic Anaerobic Digestion and Validation of Hygienization Regime. World Sci. News 2019, 125, 94–113. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, T.; Hoelzle, K.; Philipp, W.; Hoelzle, L.E. Survival of Salmonella Typhimurium, Listeria Monocytogenes, and ESBL Carrying Escherichia Coli in Stored Anaerobic Biogas Digestates in Relation to Different Biogas Input Materials and Storage Temperatures. Agriculture 2022, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on Microbiological Criteria for Foodstuffs (Text with EEA Relevance); Text with EEA Relevance. 2020.

- Barra Caracciolo, A.; Visca, A.; Rauseo, J.; Spataro, F.; Garbini, G.L.; Grenni, P.; Mariani, L.; Mazzurco Miritana, V.; Massini, G.; Patrolecco, L. Bioaccumulation of Antibiotics and Resistance Genes in Lettuce Following Cattle Manure and Digestate Fertilization and Their Effects on Soil and Phyllosphere Microbial Communities. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 315, 120413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Physicochemical Properties | Units | Soil | Digestate |

| pH | - | 8.5 | 7.8 |

| Electric Conductivity (EC) | mS cm ⁻1 | 0.24 | 2.42 |

| Salinity | psu | 0.13 | 1.55 |

| Organic Matter (O.M.) | % | 1.81 | - |

| Soil Texture | - | Sandy Loam (SL) | - |

| Clay | % | 14.1 | - |

| Silt | % | 30.8 | - |

| Sand | % | 55.1 | - |

| Dry Matter (TS) | % | - | 1.81 |

| Volatile Solids (VS) | % | - | 1.08 |

| Total Nitrogen | % | - | 0.2 |

| Phosphorus (P) | mg kg ⁻1 | 11.87E | 310T |

| Nitrate Nitrogen (N-NO3) | mg kg ⁻1 | 25.77E | <500 |

| Calcium (Ca) | mg kg ⁻1 | 3610E | 710T |

| Magnesium (Mg) | mg kg ⁻1 | 290E | 260T |

| Potassium (K) | mg kg ⁻1 | 320E | 1430T |

| Zinc (Zn) | mg kg ⁻1 | 2.70E | 18T |

| Iron (Fe) | mg kg ⁻1 | 5.09E | 73.8T |

| Manganese (Mn) | mg kg ⁻1 | 3.53E | 11.9T |

| Boron (B) | mg kg ⁻1 | 0.19E | 2.31T |

| Sodium (Na) | mg kg ⁻1 | 113E | 560T |

| Heavy Metals | |||

| Cadmium (Cd) | mg kg ⁻1 | 0.18T | 0.007T |

| Chromium (Cr) | mg kg ⁻1 | 75.5T | 0.35T |

| Mercury (Hg) | mg kg ⁻1 | 0.05T | 0.02T |

| Copper (Cu) | mg kg ⁻1 | 23.7T | 0.40T |

| Lead (Pb) | mg kg ⁻1 | 14.0T | 0.09T |

| Arsenic (As) | mg kg ⁻1 | 7.90T | 0.05T |

| Pathogens | |||

| Salmonella spp. | cfu g⁻1 | N.D. | N.D. |

| Enterococcus faecalis | cfu g⁻1 | N.D. | 1,8 x 10² |

| Escherichia coli (E. coli) | cfu g⁻1 | N.D. | 45est |

| Peak number | Compound | RT | F | D | FD | C |

| 1 | Limonene | 15.91 | 0.80b | 0.80b | 0.78b | 0.86a |

| 2 | Eucalyptol | 16.07 | 9.02a | 7.43a | 8.40a | 7.41a |

| 3 | trans-β-Ocimene | 17.34 | 2.10b | 2.77a | 2.67a | 1.69c |

| 4 | Linalool | 21.41 | 45.50b | 46.86b | 46.48b | 49.61a |

| 5 | Bornanone | 24.58 | 0.81a | 0.74a | 0.80a | 0.64b |

| 6 | Terpinen-4-ol | 27.45 | 3.75a | 3.89a | 3.67a | 3.33b |

| 7 | Eugenol | 42.23 | 6.13b | 8.17b | 7.41b | 10.11a |

| 8 | β-Elemene | 44.47 | 1.46b | 1.64a | 1.48b | 1.49b |

| 9 | Methyleugenol | 45.31 | 3.47a | 2.05b | 2.18b | 1.93b |

| 10 | α-Bergamotene | 47.05 | 6.29a | 5.87a | 5.56a | 4.61a |

| 11 | α-Humulene | 47.93 | 0.83a | 0.80a | 0.78a | 0.61b |

| 12 | β-Farnesene | 48.22 | 1.31a | 1.02b | 0.97b | 0.92b |

| 13 | GermacreneD | 49.40 | 2.31d | 3.21a | 2.59b | 2.48c |

| 14 | τ-Cadinol | 55.36 | 6.29b | 7.57a | 6.36b | 7.18a |

| Total | 90.07 | 92.82 | 90.13 | 92.87 |

| Chemical and nutrient properties | Treatments | ||||

| Units | F | D | FD | C | |

| pH | − | 7.7a | 7.8a | 7.8a | 8.3b |

| Salinity | psu | 0.91c | 1.20a | 1.07b | 0.16d |

| Electric Conductivity | mS cm⁻1 | 1.30c | 1.94a | 1.47b | 0.22d |

| EBoron (B) | mg kg⁻1 | 0.21c | 0.25a | 0.23b | 0.17d |

| ECalcium (Ca) | mg kg⁻1 | 3373c | 3868a | 3720b | 3332c |

| EPhosphorus (P) | mg kg⁻1 | 13.5c | 20.0a | 17.5b | 9.5d |

| EIron (Fe) | mg kg⁻1 | 5.25c | 8.51a | 7.04b | 4.22d |

| EPotassium (K) | mg kg⁻1 | 380.0c | 750.0a | 650.0b | 294.0d |

| EMagnesium (Mg) | mg kg⁻1 | 310.4c | 420.6a | 380.0b | 274.3d |

| EManganese (Mn) | mg kg⁻1 | 5.20c | 6.70a | 5.83b | 3.38d |

| ESodium (Na) | mg kg⁻1 | 135.1c | 324.9a | 271.7b | 110.7d |

| EZinc (Zn) | mg kg⁻1 | 2.84c | 6.50a | 4.80b | 2.22d |

| Nitrate Nitrogen (N-NO3) | mg kg⁻1 | 48.60a | 43.70b | 50.50a | 12.35c |

| Organic Matter (O.M.) | % | 1.86c | 2.80a | 2.53b | 1.84c |

| Heavy Metals | Treatments | ||||

| Units | F | D | FD | C | |

| TArsenic (As) | mg kg⁻1 | 8.04a | 8.18a | 8.15a | 7.85b |

| TCadmium (Cd) | mg kg⁻1 | 0.19a | 0.20a | 0.19a | 0.19a |

| TChromium (Cr) | mg kg⁻1 | 75.29a | 76.61a | 76.12a | 75.09a |

| TCopper (Cu) | mg kg⁻1 | 23.74a | 24.13a | 24.06a | 23.47a |

| TLead (Pb) | mg kg⁻1 | 15.1a | 15.3a | 15.0a | 14.8a |

| TMercury (Hg) | mg kg⁻1 | 0.05a | 0.05a | 0.04a | 0.04a |

| Pathogens | Treatments | ||||

| Units | F | D | FD | C | |

| Soil | |||||

| Salmonella spp. | cfug˗1 | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D |

| Enterococcus faecalis | cfu g˗1 | N.D | <9.1 | <9.1 | N.D |

| Escherichia coli (E. coli) | cfu g˗1 | N.D | <9.1 | <9.1 | N.D |

| Basil Leaves | |||||

| Salmonella spp. | cfu g˗1 | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D |

| Enterococcus faecalis | cfu g˗1 | N.D | 91est | 73est | N.D |

| Escherichia coli (E. coli) | cfu g˗1 | N.D | <9.1 | <9.1 | N.D |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).