1. Introduction

Meeting the growing global demand for high-quality food, presents significant challenges for modern agriculture [

1]. To establish sustainable agro-food systems, it is crucial to reduce the negative environmental impacts caused by anthropogenic activity on soil degradation, reduction of fertility, and loss of biodiversity, especially in a scenario of climate extremes. Practices that simplify ecological interactions in agroecosystems, such as monoculture, intensive soil mobilization, excessive applications of soluble mineral fertilizers and toxic chemical compounds, interfere with trophic connection networks and alter the structure of biotic communities, reducing the diversity of beneficial species in the ecosystems, and consequently their ability to perform their multiple functionalities [

2,

3]. Implementing ecological agricultural practices as part of management strategies, is essential to address these challenges.

The meta-analysis indicates that productivity in organic food systems worldwide is on average 19-25% lower compared to that derived from conventional agriculture, with this difference depending on the region, agricultural culture, technological level employed and edafo-climatic conditions [

4]. In this sense, biofertilizers are important tools to increase plant productivity, consisting of products or substances, liquid or solid based, composed of live microbial preparations, and on a global scale, promoted an increase of 11.8% in the production of vegetables, root crops and cereals compared to the control without fertilization, in addition to significantly improving nutrient use efficiency by an average of 9.6%, reducing nutrient loss and increasing uptake by plants [

5,

6]. The global market size of biofertilizers was estimated at USD 1.81 billion in 2021, with the market forecast to grow at a compound annual rate of around 12% between 2021 and 2028, reaching a value of around USD 4, 5 billion in 2028 [

7].

In general, brazilian soils are acidic and chemically deficient (high degree of weathering), and to correct and supply the demand for nutrients it is necessary to use fertilizers and correctives. In 2022, brazilian agriculture had the approximate consumption of 38.2 million tons of fertilizers in the national market, in which 33.87 million tons (86%) were imported [

8]. Due to instabilities in the supply of inputs, reduction of the different world reserves, and the imbalance in the trade balance (input price), threats to national food security are identified [

9].

There are 336 thousand establishments dedicated to horticulture in Brazil, in which more than 100 horticultural species are cultivated, with an area of 1.6 million hectares destined to the production of the main crops. The sector generates an average of 30 million tons of vegetables per year, and employs close to 2.4 million people, generating around R

$ 55 billion per year in the national economy [

10]. However, it is observed in the different scenarios of brazilian horticulture, challenges related to infrastructure, technology, management and commercialization. The main problem is related to the use of technologies and practices that result in nutritional imbalance, loss of soil fertility and plant health [

11].

In the approach to recycling organic materials, agricultural and animal waste, there is an alternative organic amendment allowed in organic systems, the bokashi-type biofertilizer. Known to improve the microbial activity, fertility and physical-hydric properties of substrates and agricultural soils [

12,

13,

14,

15], the biofertilizer is made from a balanced mixture of materials of animal, vegetable and mineral origin, and subsequent assembly of a windrow for the occurrence of the controlled process of thermophilic aerobic semi-decomposition, which is mediated by a complex community of microorganisms. The result of the microbiological transformation of the base materials is a stable and bioavailable compound. To improve the efficiency of the bio-oxidation process, and increase the mineralization of organic matter, it is possible to apply microbial inoculum and ultra-diluted and dynamized preparations [

16,

17].

Bokashi-type formulations have a positive effect on the production and quality of various agricultural crops [

18,

19]. The bokashi-type biofertilizer acts in the biofortification of vegetables, increasing the acquisition and efficiency in the use of nutrients, and increasing the photosynthetic capacity [

20]. In addition, there is evidence of soil-borne suppression capacity, by the suppression of phytopathogenic species. The physical-chemical quality, associated with the microbiological richness and bioactive substances (hormones, amino acids, enzymatic complexes, and siderophores) of the biofertilizer, allows it to be incorporated in a mixture with the substrate, promoting seed germination, to generate high-quality seedlings and provide satisfactory yields of the cultures [

21,

22].

Characterizing the microbiome and nutrient content of bokashi-type biofertilizer formulations is necessary to deepen knowledge about which microorganisms are being inoculated into the system, as well as the capacity of the biofertilizer as a source of nutrients [

23,

24]. Thus, the study consists of evaluating different inoculation technologies to stabilize the process of aerobic biological transformation of the "bokashi" type biofertilizer, as well as the effect of the biofertilizer on the production of beet and cabbage seedlings, and subsequent transplantation and cultivation in the field, and on the nutritional aspects of crops and their effects on soil chemical attributes.

2. Materials and Methods

The bioassay was carried out in the municipality of Lages, Santa Catarina (50°18'10.80” W; 27°47'31.82” S), with a geometric altitude of 920 meters (SIRGAS 2000), during the period of January 2021 to June 2022. The climate type is Cfb, according to Köppen - temperate climate, with mild summer [

25]. The experiment was conducted under greenhouse conditions for the production of seedlings, and when they reached the appropriate phenological stage, they were transplanted to field conditions, under management guided by the no-tillage system of organic vegetables (SPDH), in the agroecological experimental area located in the Center of Agroveterinary Sciences (CAV-UDESC).

2.1. Production of Bokashi-Type Biofertilizer Formulations

The bokashi-type biofertilizer was prepared using the following materials and proportions (w/w): poultry litter (27.42%), sieved clayey soil (27.42%), rice husks (27.42%), rice bran (1.37%), varvite remineralizer (9.51%), charcoal (1.37%), brown sugar (0.034%), wood ash (1.00%), yeast (0.03%) and water until reaching 60% humidity. From the base recipe of 3 Mg, the ingredients were mixed and homogenized with the aid of a bucket loader attached to the tractor. With the mixture ready, 200 kg of compost were weighed and separated into eight windrows for the inoculation of following bio-based treatments: T1 BBAC: bokashi + 10 ml L-1 commercial product Bioaction Power ® (Bacillus megaterium, B. subtillis, B. amyloquefaciens and B. pumillus; T2 BEM: bokashi + 10 ml L-1 Efficient microorganisms (methodology Bonfim et al., 2011); T3 BPPGR: bokashi + commercial product ® (Azospirillum brasilense, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Rhizobium sp and Saccharomyces cerevisiae); T4 BCH: bokashi + 10 ml L-1 Dynamized ultra-diluted homeopathic preparation Chamomilla 12 CH; T5 BCV: Bokashi + 10 ml L-1 Carbo vegetabilis 12 CH; T6 BCC: bokashj + 10 ml L-1 Calcarea carbônica 12 CH; T7 BBP: bokashi + biodynamic preparations for compound 502-507; T8: BCONTROL (only commercial yeast).

The aerobic semi-decomposition process took place for 13 days, with manual turning twice a day in the first seven days, and with a decrease in temperature once a day. During the production process of the bokashi-type formulations, the daily temperature variations of the windrows were measured (six measurements per windrow, via digital thermometer). Samples were taken for analysis of pH H2O (potentiometry 1:2.5) and electrical conductivity (Ec) every 3 days. After the biostabilization of the microbiological transformation process, the different formulations presented characteristics suitable for application (pleasant odor, Tº below room temperature, crumbly consistency). Six sub-samples of each treatment were collected, being homogenized to compose the work sample. Biofertilizer samples were sent for analysis to the ABC Foundation laboratory (Paraná) where analyzes of macro and micronutrients, fulvic and humic acids, organic matter, organic carbon and density were carried out (samples in triplicate).

The samples of the biofertilizer formulations were kept frozen until they were sent for metagenomic analysis, which was conducted at the company Lagbio – Metagenomics Analysis and Biotechnology, located in Toledo (PR). For this step, 0.25 grams from each bokashi-type biofertilizer formulation evaluated was used for DNA extraction and subsequent sequencing. The metagenomic analysis steps follow the pipeline described by Breitwieser

et al., (2017). Bacterial diversity was assessed by sequencing the V4-V5 region of the 16S rRNA gene. The library was sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA) yielding an average of 55.000 raw reads per sample. The analysis of the results was carried out in a Linux environment, with the programs R (R core team, 2020), Pavian [

27]), MGrast [

28] and Stamp [

29]. After the treatments of the sequences, a file was generated with the summary of the most important agronomic information that can contribute to the agricultural scenario. For the taxonomic and metabolic analysis, the Refseq and subsystems databases were used. [

28].

2.2. Production of beet and Cabbage Seedlings in a Greenhouse

The eight treatments described above were evaluated, with the addition of a control treatment, using only the commercial substrate Carolina Soil® (CSCONTROLE), with 4 replications (completely randomized design). The methodology for distributing and conducting the bioassay was carried out in a “double-blind” method, with the disclosure of treatments only at the end of the study. Each bokashi-type biofertilizer formulation was sieved through a 4 mm mesh, being incorporated in a 40% proportion (bokashi weight/substrate weight) with the commercial substrate Carolina Soil® (60 %), for the production of beet (Beta vulgaris) seedlings and later cabbage (Brassica oleraceae).

Beet sowing was carried out on 1/18/2021, using plastic trays with 128 cells, with 4 beet glomeruli (seeds) per cell (60 cells for evaluation). On the 6th day after sowing (DAS), the plants were pricked, remaining one plant per cell. The trays remained in the greenhouse for 30 days, until they were transplanted to the field (02/18/2021). Cabbage seedlings were produced in a similar way to that described for beet, but sowing two seeds per cell, in a total of 80 cell for evaluation (05/01/2021). The cabbage variety used was “Chato de Quintal cabbage - Topseed blue line”. On the 6th DAS, the plants were pricked, leaving one plant per ballot. The trays remained in the greenhouse for 25 days, until they were transplanted to the field (05/26/2021). The trays were placed in plastic basins to simulate the floating system, and the water was replaced manually, based on the height of the water layer.

2.3. Preparation of the Cultivation Area, Experimental Design and Transplanting of Cultures to the Field

The experimental area was subjected to subsoiling, followed by harrowing. Afterwards, 5 Mg ha

-1 of tanned poultry litter and 5 Mg ha

-1 of liquid pig manure were applied to the total area, and then the beds were prepared with the aid of a filler. The beds were covered with crushed biomass from tree pruning, and periodic maintenance was carried out when necessary. The soil was classified as Humic Dystrudept [

30], and the chemical analysis of the soil is presented in

Table 1. The design used in the experiment was in randomized blocks, with 4 repetitions, also conducted in the “double blind” methodology. The treatments consisted of the 8 previously described, plus a control treatment (CSCONTROL), in which the seedlings were produced only with the substrate Carolina Soil®.

In total, there were 36 sampling units (beds) of 1.44 m², where ten days before transplanting the beet seedlings, a surface application of the equivalent of 5 Mg ha-1 of the respective bokashi-type biofertilizer was carried out, which the seedling was produced per bed, and the control treatment 5 Mg ha-1 of tanned poultry litter. 30 beet seedlings were transplanted on 02/18/2021, spacing 15 x 30 cm. During the development of the culture, the SPAD index and seedling height were evaluated in two moments. On the 40th day after transplanting, leaf tissue samples were collected from the upper portion of the aerial part of 5 healthy plants for macronutrient foliar analysis.

After harvesting the beet crop, 6 cabbage seedlings were transplanted per bed, spacing 80 x 50 cm (05/26/2021). Fertilization with the respective bokashi-type biofertilizer that the seedling was produced with, was carried out with a 50% reduction in the application rate compared to the previous crop (2.5 Mg ha-1). When most of the plants were in head closure, samples of the aerial part of 2 representative plants were collected for macronutrient analysis of the leaf tissue. SPAD index was evaluated in one moment, and plant height in two moments.

The beet plants were harvested on 04/07/2021, and to evaluate the parameters related to the crop, 10 central plants were harvested from each plot. The beet roots were cleaned and packed in paper bags and then washed and air-dried and classified according to the Brazilian Program for the Modernization of Horticulture, according to CEAGESP (2010) classification standards.

The evaluations of the aerial part of the beet consisted of: a) fresh mass of the aerial part (FMAP); b) aerial part dry mass (DMAP); c) leaf area index (LAI). The leaf area index was performed using a digital scanner.

About the evaluations of tuberous roots of beet: a) mean root diameter (RD) (average of longitudinal and transverse measurements); b) root fresh mass (MFR); c) productivity; d) dry mass of tuberous roots (MSR). The RD was determined with the average of the longitudinal and transversal measurements, using a digital caliper. The MF determination was obtained through the mass of the roots separately from the leaves and stems, using a precision scale. Productivity was calculated by multiplying the average tuberous root weight of the respective treatment by the number of plants per hectare.

The shoots were placed in perforated paper bags and then weighed to check the fresh mass of the shoots, and subsequent processing to determine the leaf area index (LAI), using a digital scanner for the leaf area (Licor model). 3100) in the Forage Laboratory (CAV-UDESC). After performing the LAI, the samples were placed in an air circulation oven at 65 ºC, until constant mass, to determine the dry mass of the aerial part.

Regarding the analyzes of the aerial part of the cabbage, they were: a) number of leaves (external and internal), head size, head fresh mass and productivity (kg ha-1).

2.4. Collection of Samples of Leaf Tissue of Crops for Chemical Analysis

Plant tissue from sugar beet and cabbage were ground to a degree of agate, and sieved through a 1mm mesh, followed by sulfuric foliar digestion of 0.2g of plant tissue for determination of macronutrients, following the methodology described by Tedesco et al., (1995). The Ca and Mg concentrations in the plant tissue were quantified by the AA 200 equipment by atomic absorption. P and K were determined by colorimetry [

32] and by flame photometry, respectively. The N concentration was determined by steam entrainment, in a Kjeldahl semi-micro equipment and subsequent titration with 0.0125 M H

2SO

4.

From the MSPA and the levels of N, P, K, Ca and Mg, the accumulated levels of the same in the plant tissue of the evaluated plants were calculated according to equation 1 [

33].

where: NAmacro: corresponds to the amount of the macronutrient accumulated in the plant tissue of the plants and the dry matter of the aerial part (DMAP) produced by the tested plants.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data were submitted to the test for homogeneity of variances by the Ascombe-Tukey test, and for normality of residues by the Shapiro-Wilk test. When the assumptions were met, the means were compared by means multiple comparison test (LSD) at 5% probability. All analyzes were performed in the STATGRAPHICS statistical environment (Centurion version XVI.I).

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Characterization of Bokashi-Type biofertilizer Formulations

Table 2 shows the values of macronutrients (N, P, K, Ca, Mg, S, Na) and micronutrients (B, Cu, Mn, Zn, Fe), dry matter (DM), organic carbon (OC) , organic matter (M.O), fulvic acid (FA) and humic acid (HA), compound density (Ds), values of pH H

2O, pH CaCl

2, electrical conductivity (Ec) in water and CaCl

2, and C/N ratio for the eight elaborated formulations of the bokashi-type biofertilizer.

Fulvic acid values ranged from 3.79 to 36.43%, with the BPPGR treatment having the highest levels of fulvic acids (36.43%), followed by BEM with 10.24%. Regarding humic acid contents, they ranged from 3.21% (BCONTROL) to 5.85% (BEM). The amplitude in organic carbon contents was on average 59.2% when comparing the average contents between BPPGR (12.36%) and BCH (19.68%) treatments. The O.M contents, there was a variation of 59.2% between the minimum and maximum value, where the minimum content was 27.19% (BPPGR) and the maximum 43.31% (BCH). Smaller amplitudes of variation were observed in the contents of N, P, K, Na and S. In general, the nutrient contents of bokashi-type biofertilizer formulations were comparable to those observed in most routinely used organic fertilizers, in addition to presenting values similar to those found in the literature (LEBLANC et al., 2005; TRANI et al., 2013). The bokashi -type biofertilizer formulations characterized contain high levels of micronutrients such as Fe, Mn, Zn and B. Humidity was also monitored and was in the ideal range for the composting process, staying close to 40% of moisture in the windrows at the beginning of the process and ending with a DM content above 83%. According to the data obtained from the C/N ratio, there was a variation from 8.64 (BMPCV) to 13.89 (BCONTROLE), values which point to a net rate of decomposition and mineralization of N quickly in the different formulations evaluated, when incorporate into the soil.

3.2. Metagenomic Analysis of Bokashi-Type Biofertilizer Formulations

Through metagenomic techniques, it is possible to access a large part of the information necessary to know which genes and organisms inhabit the ecosystem under study, and thus elucidate how the biogeochemical processes occur in the place.

Table 2 shows some data from the sequenced samples.

The number of reads is not related to the diversity of the sample, and the representation of the samples occurs even with fewer reported reads. The number of reads ranged from 197.097 (BBAC) to 458.348 (BBP), the number of genera from 1187 (BBAC) to 1728 (BBP), finally the number of species from 4038 (BBAC) to 7286 (BBP), being more than 99% of the sequenced microbiome of each treatment is composed of bacteria. About the bacterial genera of the evaluated treatments, a predominance of the genera Marinobacter sp., Halomonas sp., Galbibacter sp., Alcanivorax sp. is observed, where the phylum of Proteobacteria, has as an important propellant the genus Bradyrhizobium sp., an important bacterium used as inoculant in the planting of legumes such as soybean. The phylum Actinobacteria was boosted by the increase in the amount of the genus Streptomyces sp., this genus has among its main activities the decomposition of organic matter and the production of the antibiotic streptomycin. It is still possible to verify the presence of the genera of microorganisms that promote plant growth, Bacillus sp., Pseudomonas sp., Azospirillum sp. and Rhizobium sp. It is important to point out that none of the evaluated formulations sequenced phytopathogenic bacterial genera, which indicates that the aerobic semi-decomposition process was effective in inactivating pathogens. There is also the possibility that the materials used were free of biological contaminants.

3.3. Agronomic Variables of Beet and Cabbage Crops after Transplanting in the Field

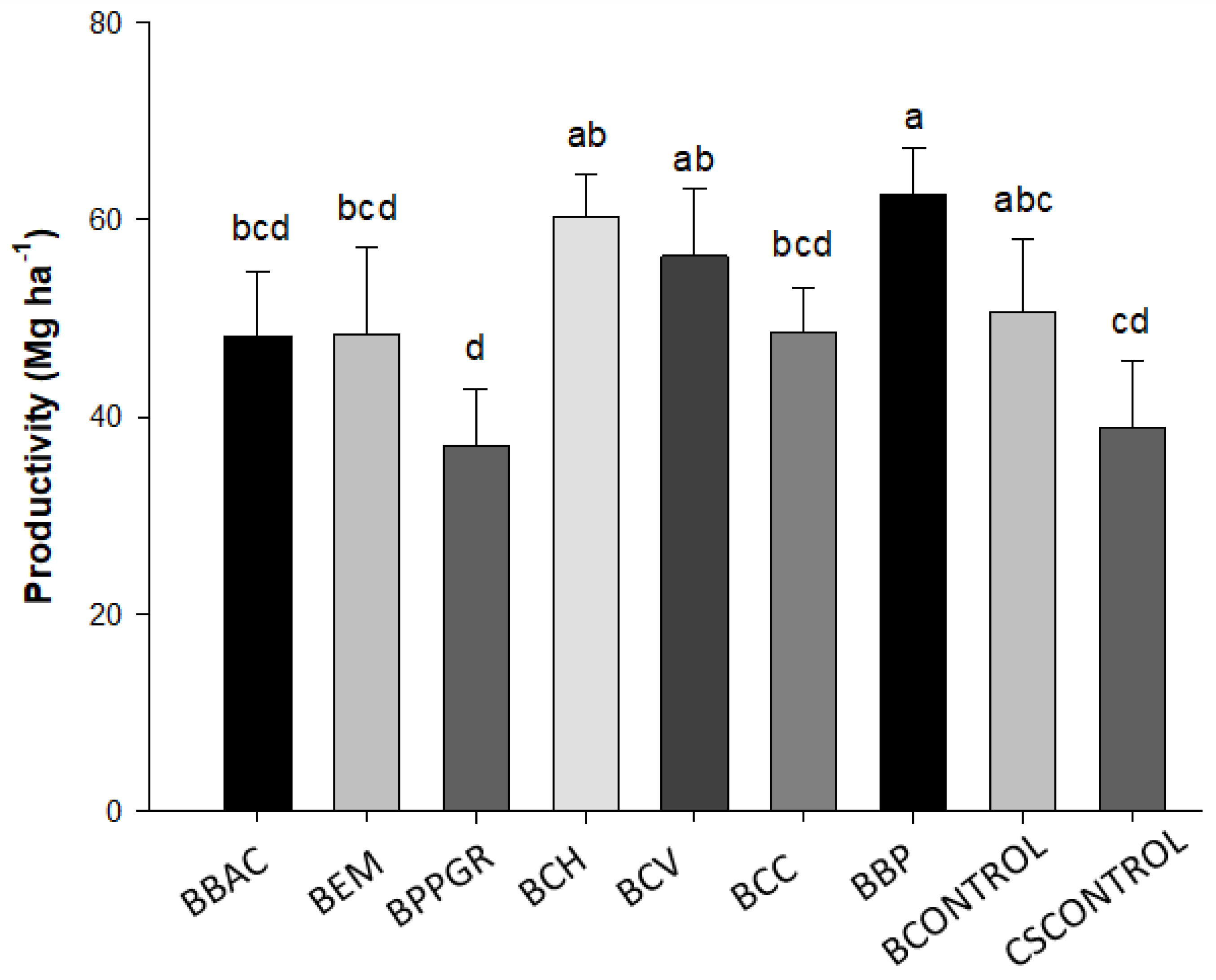

In

Table 4, it is possible to verify the average values of shoot fresh mass (SFM), shoot dry mass (SDM), root fresh mass (RFM), root dry mass (RDM), leaf area index (LAI), average transversal diameter of beet tuberous roots (ATD) and commercial classification. The productivity data (kg ha

-1) of the beet plants are shown in

Figure 1.

The highest average value of SFM was evidenced in beet plants produced with the bokashi-type biofertilizer elaborated with the application of Carbo vegetabilis 12 CH (209.2 g). The plants produced by the treatment with the addition of biodynamic preparations for compost (BBP) showed the highest values of RFM (282.0 g) and RDM (22.4 g), followed by the treatments elaborated with the ultra-diluted and dynamized preparations Chamomilla 12 CH and (BCH), Carbo vegetabilis 12 CH (BCV). The BCC treatment (bokashitype biofertilizer + Calcarea carbonica 12 CH) had the highest LAI (1958.6 m²).

When analyzing the ADT, the BPB treatment presented the highest value 76.3 mm (p<0,05) showing an increase of close to 12.2% in the caliber of the tuberous roots in relation to the CSCONTROL (68 mm). It is possible to perceive a certain antagonism of the interaction of the beet plants produced from the BPPGR treatment in the quality and productivity of the beet. The BPPGR treatment showed the lowest value for DMT. Regarding the commercial classification of tuberous roots, all fall into class 2A (greater than 50 mm and less than 90 mm). It is possible to observe significant increments in the productivity of beet plants when they were cultivated from the combination of bokashi-type biofertilizer (40% w/w) + conventional substrate (60% w/w) in comparison with those produced only with conventional substrate (p < 0.05). The highest yields were identified in the BBP (62.6 Mg ha

-1), BCH (60.2 Mg ha

-1) and BCV (56.3 Mg ha

-1) treatments, corresponding to an increase of 60.9%, 54 .7% and 44.7% respectively compared to CSCONTROL productivity (38.9 Mg ha

-1). Biodynamic preparations (502-507) have action on the development, physiology and resistance to biotic stresses in PB plants, and in this case, the interaction between PB 502-507 when applied in the production of biofertilizer type bokashi, and later as fertilizer for the crop, increased the productivity of beet plants [

34].

The lowest average productivity was observed in the BPPGR treatment (37.08 Mg ha

-1), again indicating a less efficient effect of the application of the microorganisms

Azospirillum brasiliense,

Pseudomonas fluorescens,

Rhizobium sp and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae as inoculants in the preparation of bokashi-type biofertilizer. The negative result in relation to the productivity of the BPPGR treatment (application of the commercial product Biostart Power®, based on the species

Azospirillum brasilense,

Pseudomonas fluorescens,

Rhizobium sp and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae) can be explained due to antagonistic interactions between microbiological communities, which can cause negative impact by inhibiting and hindering the multiplication of the newly introduced inoculum in the system [

35].

Table 5.

Mean values of the chemical composition of the aerial part of the “Katrina” variety beet plants, N, P, K Ca and Mg content in % and their respective accumulations in mg. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

Table 5.

Mean values of the chemical composition of the aerial part of the “Katrina” variety beet plants, N, P, K Ca and Mg content in % and their respective accumulations in mg. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

| Treatments |

N |

P |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

| --------------- % --------------- |

|---|

| BBAC |

5.3 ab |

1.72 ns

|

5.89 abc |

0.27 a |

0.17 ab |

| BEM |

5.29 ab |

1.83 |

4.40 c |

0.26 ab |

0.13 ab |

| BPPGR |

5.94 a |

1.71 |

4.98 bc |

0.13 c |

0.19 a |

| BCH |

5.45 ab |

1.84 |

4.37 c |

0.15 bc |

0.09 b |

| BCV |

5.15 b |

1.94 |

5.51 abc |

0.27 a |

0.13 ab |

| BCC |

5.26 b |

1.86 |

6.37 ab |

0.35 a |

0.16 ab |

| BBP |

5.0 bc |

2.00 |

5.61 abc |

0.27 a |

0.13 ab |

| BCONTROL |

4.37 c |

1.86 |

6.43 ab |

0.35 a |

0.21 a |

| CSCONTROL |

5.01 bc |

1.80 |

6.96 a |

0.34 a |

0.22 a |

| Ref. values¹ (%) |

3.0 – 5.0 |

0.2 – 0.4 |

2,0 - 4,0 |

2.5 – 3.5 |

0.3 – 0.8 |

| CV (%) |

8.68 |

15.54 |

21.21 |

29.86 |

40.91 |

| Treatments |

N accumulated |

P accumulated |

K accumulated |

Ca accumulated |

Mg accumulated |

| --------------- mg --------------- |

| BBAC |

4252.5 ab |

1372.3 b |

4753.5 ns

|

224.31 abc |

139.34 ns

|

| BEM |

5092.9 ab |

1790.6 ab |

4229.6 |

247.72 ab |

127.31 |

| BPPGR |

5115.2 ab |

1473.6 ab |

4284.4 |

114.77 c |

172.85 |

| BCH |

5492.1 a |

1810.5 ab |

4346.3 |

150.38 bc |

103.09 |

| BCV |

5016.1 ab |

1913.0 ab |

5423.5 |

262.77 ab |

128.88 |

| BCC |

4974.6 ab |

1751.9 ab |

6114.1 |

352.72 a |

167.17 |

| BPB |

5215.4 a |

2083.8 a |

5726.5 |

283.37 a |

136.30 |

| BCONTROL |

3612.1 b |

1564.1 ab |

5352.2 |

279.58 a |

164.81 |

| CSCONTROL |

4226.0 ab |

1643.5 ab |

6273.3 |

278.01 ab |

182.99 |

| CV% |

22.52 |

35.31 |

32.56 |

36.17 |

45.9 |

There were significant differences in the N content in the leaf tissue, which are in an appropriate range for the crop, where the BPPGR treatment had the highest content (5.94%), followed by the treatments BBAC (5.3%), BEM ( 5.29) and BCH (5.45%). The lowest N content in the leaf tissue was obtained in the BCONTROL treatment (4.37%), followed by BBP (5.0%) and CSCONTROL (5.01%). N acts as a basic constituent of proteins, enzymes, chlorophyll and nucleic acids, in addition to participating in the synthesis of plant hormones, a fact that justifies its high demand in cultures [

36]. Regarding the accumulated N content, the highest accumulations are attributed to plants grown from the substrate + biofertilizer prepared with biodynamic preparations for compost (5215.4 mg) and with

Chamomilla 12 CH (5492.1 mg).

Regarding the levels of P in the leaf tissue, the levels found are above the recommended reference values, but no differences were found in the level of the leaves between the evaluated treatments. The highest P accumulation was observed in the BBP treatment (2083.8 mg). Biodynamic preparation 507, based on valerian extract (

Valeriana officinalis) is related to processes involving phosphorus (P) during the preparation of the compound. It is believed that the 507 preparation can potentiate or influence the availability and cycle of phosphorus in the soil, thus promoting benefits for plants [

37]. The highest K contents in the leaf tissue were observed in the treatments CSCONTROL (6.96%), BCONTROL (6.37%) and BCC (6.37%), but no significant effect was verified on the accumulation of K between the evaluated treatments.

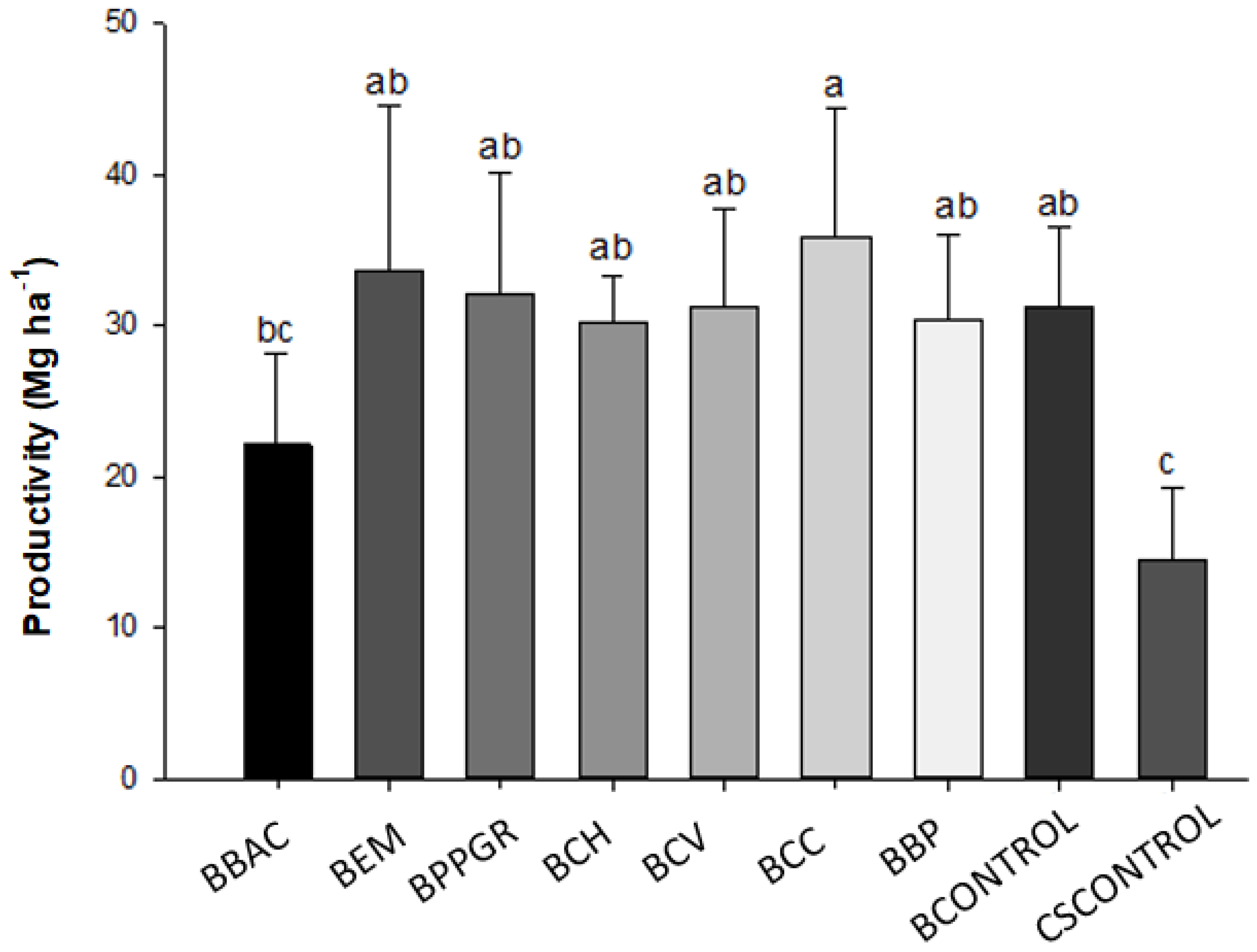

Table 6 shows the data referring to the mean values of total fresh mass of shoots (SFM), number of external leaves (NEL), number of leaves on the head (NLH), head transverse diameter (HTD) and fresh head mass (HFM), and

Figure 2 the average productivity values (Mg ha

-1) of cabbage plants in the field variety “Chato de Quintal” produced with formulations of the bokashi-type biofertilizer.

The highest average head fresh mass was obtained by the BCC treatment (1433.4 g), a value that expresses an increase close to 147.9% in relation to the CSCONTROL (578.07 g), which presented the lowest average of this variable compared to other treatments. Only the BBAC treatment (884.5 g) did not differ from the CSCONTROL. The transversal diameter of the head was also influenced by the treatments (p < 0.05), where the plants produced and fertilized with the bokashi-type biofertilizer elaborated with Calcarea carbonica 12 CH (22.1 cm) and with the biodynamic preparations for compost (21, 5 cm), obtained the highest averages for this variable, in comparison with the CSCONTROL (18.2 cm) and BBAC (17.8 cm) treatments.

There were significant differences in productivity depending on the treatment applied (p<0.05). The increase in productivity of cabbage plants was greater in the BCC treatment (35.8 Mg ha-1), being 148.6% higher than in the CSCONTROL (14.4 Mg ha-1). Only the BBAC treatment (22.1 Mg ha-1) did not differ from the CSCONTROLE treatment. The average value of increase in productivity in relation to the control, among treatments BEM, BMPCV, BCH, BCV BPB and BCONTROLE was 115.2%.

Table 7 shows the average values of the chemical composition of the aerial part of the cabbage plants of the “

Chato de Quintal” variety, N, P, K, Ca and Mg content in % and their respective accumulations in mg. A significant difference was verified in the N content of the leaf tissue between the evaluated treatments (p<0.05), where the CSCONTROL presented values in agreement with the N reference, and higher average content (4.05 %), which represents an increase of 57.5% and 50% in relation to the BEM (2.57%) and BBP (2.7%) treatments, respectively. As the productivity of the CSCONTROL treatment was the lowest among the evaluated treatments, it is possible to verify that this accumulation of N in the aerial part was not converted into biomass production and productivity. The highest accumulation of N was observed in plants produced from the bokashi-type biofertilizer made with

Calcarea carbonica 12 CH (405.8 mg), where this value represents an average increase of 54% and 102.7% respectively for treatments with biological inoculations BBAC (263.4 mg) and BEM (200.1 mg).

Regarding the levels of P in the leaf tissue, the treatments CSCONTROL (1.8%) and BPPGR (1.7%) had the highest averages, and it is noteworthy that for all treatments the values of leaf P were higher than the reference values. There was no difference in the accumulated P content. The average K contents are above the recommended reference values, and the BBAC (6.1%) and BPPGR (5.9%) treatments showed an average increase of 41.8% and 37.2% compared to the control (4.3%). K accumulation was also influenced by the application of treatments (p<0.05), where plants produced with bokashi type biofertilizer + Calcarea carbonica 12 CH (558.2 mg) and the BPPGR (542.1 mg) showed an increase average of 87% and 81% respectively when compared with the accumulation of K in the control (298.5 mg).

As for the average levels of foliar Ca, values lower than the reference values for the cabbage crop were obtained in all treatments. The BCC (0.40%) and BBAC (0.40%) treatments had the highest means, with these contents being 73.9% higher than the BCH (0.23%). The highest accumulation of calcium was also verified in the treatment with the application of the ultra-diluted and dynamic homeopathic preparation Calcarea carbonica 12 CH (36.1 mg). The foliar Mg contents are in the appropriate range for the crop, and the treatment produced from the bokashi type biofertilizer + biodynamic preparations 502-507 presented the highest average (0.30%), but for the accumulation of Mg, the treatment with Calcarea carbonica 12 CH showed the highest accumulation of Mg (22.8 mg).

4. Discussion

The periodic addition of organic matter to soils in tropical and subtropical regions, as in the case of Brazilian soils, becomes relevant due to the rapid rate of OM decomposition and the high degree of weathering, caused by the high rates of rainfall and temperatures, typical of these environments [

46]. The application of organic amendments is often used in management systems with the purpose of improving the physical, chemical and biological characteristics of the soil, as these are a source of energy and nutrients for chemical processes and biological cycles of soil organisms, helping in the state dynamic balance of the system, and playing an important role on systemic fertility and plant health [

24] In the compost, mineral nutrients such as K, Ca and Mg are mainly present in forms assimilable by plants. Nitrogen in the compost is present in both organic and inorganic forms (N–NH

4 and N–NO

3), the latter form being readily available to plants. Humic substances are directly related to the degree of maturation of the compound. Humic (HA) and fulvic (FA) acids, components of the humic fraction, are formed by the action of specialized microorganisms that transform organic waste into humified material. The humic fraction has complex physicochemical properties, being different from the original material, where the predominance of humic acids over fulvic acids at the end of composting would be indicative of adequate humification of the evaluated waste, since fulvic acids contain elements that are easily degradable [

38]. The AH/AF ratio is taken as a reference for the degree of humification of organic compounds and the higher the AH/AF ratio, the more humified the compound is [

39]. A well-humified compound must present an AH/AF ratio greater than 1.5 [

40], however some authors explain that it is not possible to establish a universal value to describe and predict the degree of maturation of compounds of different compositions [

41]. Only bokashi +

Bacillus spp. (1.3) bokashi +

Carbo vegetabilis 12 CH (1.0) and bokashi +

Calcaerea carbonica 12 CH (1.22) showed an AH/AF ratio close to the propositions of 1.5 [

40]. In the other treatments there was a predominance of the fulvic acid fraction in relation to the humic acid. Depending on the type of compound evaluated, values of AH/AF ratio can vary between 0.5 and 2.0 [

42].

The moisture, carbon, nitrogen, C/N ratio and pH H

2O contents meet the standards of IN Nº 61 of July 8, 2020 of MAPA, for the classification as class “A” solid compost organic fertilizer in the formulations BBAC, BCH, BCV, BCC and BCONTROL, but the treatments BPPGR (bokashi + commercial product Biostart Power ® based on

Azospirillum brasilense,

Pseudomonas fluorescens,

Rhizobium sp and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae), BEM (bokashi + efficient microorganisms, elaborated following methodology Bomfim

et al., 2011) and with the biodynamic preparations 502-507 showed levels of C organic less than 15% [

44]. The possible effect of intensifying carbon degradation, during the controlled bio-oxidation process of these bokashi-type formulations, may be related to the effect of biological stimulation promoted by the treatments, requiring an increase in the proportions of materials rich in C (rice husk, coal), to raise the organic carbon levels in the final product when using such inoculations. Overall, the macronutrient and micronutrient levels identified in the formulations analyzed in our study, are align with the findings reported in the scientific literature [

17].

Organic compounds for agricultural use, must present characteristics such as acceptable odor, homogeneous mixture of materials and desirable agronomic characteristics such as balanced levels of nutrients, sanitized and free of impurities and contaminants. The organic compounds responsible for odors are degraded during the bio-oxidation process, and the humification process of M.O imparts a dark color to the mature compound. No unpleasant odors or excess moisture were observed at any stage of the preparation process of the bokashi-type formulations. The formulations showed a homogeneous appearance and high dry matter content in the final compound.

It is important to point out that none of the evaluated formulations sequenced phytopathogenic bacterial genera, which indicates that the aerobic semi-decomposition process was effective in inactivating pathogens. There is also the possibility that the materials used were free of biological contaminants. The reduction or elimination of pathogens during composting can be attributed to the high temperatures presented in the thermophilic phase, together with the production of antimicrobial compounds, the hydrolytic activity of enzymes, the production of antibiotics by antagonistic microorganisms (which reduce the ability of pathogens to survive), or competition with new colonizers [

45].

The application of microbial communities via bokashi-type biofertilizer to the soil can promote plant growth, in addition to having a beneficial effect on other populations of soil microorganisms, such as archaea and fungi, which play multiple roles in plant support, being identified as plant probiotics or microorganisms that promote plant growth [

47,

48]. Among the plant support mechanism, include the ability of certain bacteria and fungi to aid in the acquisition of nutrients for plants, through processes such as nutrient mobilization (P and K solubilizing bacteria, P and K solubilizing bacteria, of Zn), nitrogen fixation [

49,

50], production of phytohormones to stimulate plant growth, and production of compounds with antipathogenic activity to protect plants against pathogens [

51].

The verified response in the plants productivity’s can be explained by the presence of bioactive substances, balanced of macro and micronutrients that the biofertilizer presents, which favors adequate nutrition to the cultures. Nutrients are available in the form of organic chelates, that is, they are linked to organic structures and have the advantage of not being lost by leaching and volatilization after application [

52]. The contribution (inoculation) of communities of exogenous microorganisms, when applied to the soil via organic compost, can increase the production rate of organic acids, phytohormones and extracellular enzymes in the system, in addition to acting directly on the cycling of organic waste, to obtain nutrients required by the microbial biomass [

51]. The mixture from organic compost with substrates can be beneficial for the cultivation of vegetables, as it increases the efficiency of nutrient use by activating enzymes that stimulate the absorption and chelation of some elements [

52]. During the mineralization process of the organic substances present in these mixtures, several nutrients and organic molecules are released into the soil solution, that promote plant growth [

53]

Some of the reference studies that applied bokashi to the soil reported an increase in the crop yields of sweet corn [

55], tomato [

56],

Pogostemon cablin [

57]

and Origanum vulgare [

58]. A similar study evaluated the effect of organic fertilizers, organic compost, biodynamic compost, laminar compost with manure and laminar compost with bokashi on beet production and concluded that all forms of fertilization were satisfactory in terms of nutrient supply and beet production [

59]. Several studies with the use of bokashi in different doses and formulations have shown positive results and increased yield of brassicas and other vegetables [60, 61, 62]. Among the benefits of using organic fertilizers are the increase in the amount and diversity of microflora, which favor the cycling of nutrients, thus improving the chemical fertility conditions of the soil [

52], in addition to acting in the control of pests and diseases such as cruciferous hernia, caused by

Plasmodiophora brassicae Wor [

63]. Its evaluated the doses of bokashi 0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.5 and 10.0 Mg ha

-1 in a test with summer broccoli, and it was possible to verify that the doses of bokashi linearly increased the characteristics of plant height, number of leaves per plant, stem and head diameter, and average head mass, up to the maximum dose used, which corresponded to 10 Mg ha

-1 [

64].

The cabbage crop is responsive to organic fertilization with bokashi, and the application of the dose of 10.0 Mg ha

-1 resulted in obtaining superior plants for all evaluated characteristics, providing higher crop productivity (32.63 Mg ha

-1) [

65]. The use of bokashi biofertilizer (4 Mg ha-1) resulted in greater vegetative development of cabbage plants, with an average productivity of 80.36 Mg ha

-1 [

63]. The productive responses observed in this work were lower than those reported by Condé

et al., (2017) and higher than those reported by Xavier

et al., (2019).

Notedly, biodynamic agricultural practices are viable alternatives for farmers, as in addition to improving the quality of life of those involved in the process, they present characteristics with an integrated focus on the management of agricultural production systems, making them sustainable in the long term [

66]. One of the possible mechanisms of action of biodynamic preparations is that water acts as an information transmitter, where what is dissolved in it, through electromagnetic waves, allows the information to be transmitted to the recipient of this aqueous dilution, who is then responsible for by creating substances in it [

67].

5. Conclusions

The highest yields of the beet crop in the field were derived from seedlings produced from the treatments biofertilizer bokashi + biodynamic preparations 502-507 BPB (62.6 Mg ha-1), bokashi + Chamomilla 12CH (60.2 Mg ha-1) and bokashi + Carbo vegetabilis 12 CH (56.3 Mg ha-1), corresponding to an increase of 60.9%, 54.7% and 44.7% respectively compared to the productivity of the control treatment (38.9 Mg ha-1). The application of the commercial product based on Azospirillum brasilense, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Rhizobium sp and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (10 ml L-1), as a microbiological inoculant for the preparation of bokashi-type biofertilizer, did not increase productivity for sugar beet.

The increase in productivity of cabbage plants was higher in the treatment bokashi + Calcarea carbônica 12 CH (35.8 Mg ha-1), being 148.6% higher than the control (14.4 Mg ha-1). Only the BBAC treatment (22.1 Mg ha-1) did not differ from control. The average value of increase in productivity in relation to the control, among treatments BEM, BPPGR, BCH, BCV BBP and BCONTROLE was 115.2%.

The contents of moisture, carbon, nitrogen, C/N ratio and pH H2O meet the standards of IN Nº. 61 of July 8, 2020 of MAPA in the BBAC, BCH, BCV, BCC and BCONTROLE formulations, but the BPPGR treatments (bokashi + commercial product Biostart Power ® based on Azospirillum brasilense, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Rhizobium sp and Saccharomyces cerevisiae), BEM (bokashi + efficient microorganisms, elaborated following methodology Bomfim et al., 2011) and with the biodynamic preparations 502-507 showed levels of organic C less than 15%.

Figure 1.

Productivity of “Katrina” variety beet plants produced from bokashi-type biofertilizer formulations, in an ecological field-based system (plant population 221.944 ha-1). Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021. Note 1: CV = 17.81%. Note 2: Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ from each other by the LSD test (p<0.05). BBAC = Bokashi + Bacillus megaterium, B. subtillis, B. amyloquefaciens and B. pumillus (Bioaction Power ®); BEM = Bokashi + EM; BPPGR = Bokashi + Azospirillum brasilense, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Rhizobium sp and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Biostart Power ®); BCH = Bokashi + Chamomilla 12 CH; BCH = Bokashi + Carbo vegetabilis 12 CH; BCC = Bokashi + Calcarea carbônica 12 CH; BBP = Bokashi + biodynamic preparations for compound 502 – 507; BCONTROL = Bokashi control (only commercial yaest).

Figure 1.

Productivity of “Katrina” variety beet plants produced from bokashi-type biofertilizer formulations, in an ecological field-based system (plant population 221.944 ha-1). Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021. Note 1: CV = 17.81%. Note 2: Means followed by the same letter in the column do not differ from each other by the LSD test (p<0.05). BBAC = Bokashi + Bacillus megaterium, B. subtillis, B. amyloquefaciens and B. pumillus (Bioaction Power ®); BEM = Bokashi + EM; BPPGR = Bokashi + Azospirillum brasilense, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Rhizobium sp and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Biostart Power ®); BCH = Bokashi + Chamomilla 12 CH; BCH = Bokashi + Carbo vegetabilis 12 CH; BCC = Bokashi + Calcarea carbônica 12 CH; BBP = Bokashi + biodynamic preparations for compound 502 – 507; BCONTROL = Bokashi control (only commercial yaest).

Figure 2.

Mean productivity values (Mg ha-1) of cabbage plants in the field, “Chato de Quintal” variety produced with bokashi-type biofertilizer formulations, Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

Figure 2.

Mean productivity values (Mg ha-1) of cabbage plants in the field, “Chato de Quintal” variety produced with bokashi-type biofertilizer formulations, Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

Table 1.

Chemical and physical attributes of the Humic Dystrudept before the implementation of the experiment. Agroecological experimental area, CAV-UDESC. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil. 2021.

Table 1.

Chemical and physical attributes of the Humic Dystrudept before the implementation of the experiment. Agroecological experimental area, CAV-UDESC. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil. 2021.

| Clay |

pH H2O |

SMP |

P |

K |

O.M |

Al |

Ca |

Mg |

H + Al |

| % |

|

|

------- mg dm-3---- |

% |

------------ cmolc dm-3-------- |

| 0,00 - 0,20 m |

| 36 |

5.53 |

6.19 |

29.35 |

146.5 |

2.9 |

0.00 |

11.92 |

5.51 |

3.51 |

Table 2.

Chemical characterization of the contents of fulvic acids (FA), humic acids (HA), dry matter (DM), organic carbon (OC) , nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), sulfur (S), boron (B), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), density (Ds), pH H2O, pH CaCl2, Ec H2O, Ec CaCl2 and C/N of the evaluated formulations of the bokashi-type biofertilizer. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

Table 2.

Chemical characterization of the contents of fulvic acids (FA), humic acids (HA), dry matter (DM), organic carbon (OC) , nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), sulfur (S), boron (B), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), density (Ds), pH H2O, pH CaCl2, Ec H2O, Ec CaCl2 and C/N of the evaluated formulations of the bokashi-type biofertilizer. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

| Treatments |

FA |

HA |

DM |

OC |

M.O |

N |

P |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

Na |

S |

| |

---------------------------------------------- % ----------------------------------------------------- |

|

| BBAC |

3.79 |

4.93 |

83.8 |

15.19 |

33.41 |

1.43 |

0.74 |

1.86 |

3.68 |

1.76 |

0.31 |

0.36 |

| BEM |

10.24 |

5.85 |

85.5 |

14.14 |

31.12 |

1.32 |

0.72 |

1.89 |

3.33 |

1.61 |

0.31 |

0.36 |

| BPPGR |

36.43 |

3.72 |

83.9 |

12.36 |

27.19 |

1.43 |

0.84 |

1.97 |

4.28 |

2.02 |

0.34 |

0.39 |

| BCH |

4.90 |

4.52 |

85.2 |

19.68 |

43.31 |

1.44 |

0.91 |

2.03 |

4.19 |

2.01 |

0.36 |

0.42 |

| BCV |

3.56 |

3.56 |

85.7 |

16.76 |

36.86 |

1.34 |

0.77 |

1.91 |

3.20 |

1.70 |

0.33 |

0.37 |

| BCC |

4.46 |

5.45 |

87.3 |

18.52 |

40.75 |

1.38 |

0.74 |

1.89 |

3.58 |

1.74 |

0.33 |

0.36 |

| BBP |

5.74 |

3.98 |

84.2 |

13.71 |

30.17 |

1.31 |

0.69 |

1.82 |

3.63 |

2.05 |

0.30 |

0.34 |

| BCONTROL |

6.77 |

3.21 |

84.4 |

18.20 |

40.03 |

1.31 |

0.76 |

1.86 |

3.51 |

1.71 |

0.32 |

0.36 |

| Treatments |

B |

Cu |

Mn |

Zn |

Fe |

Ds |

pH

H2O

|

pH

CaCl2

|

EcH2O

|

EcCaCl2

|

C/N |

| |

-----------------mg kg-1--------- % g cm-3----------------------------------ms-1

|

| BBAC |

42.1 |

437.1 |

552.1 |

284.8 |

5.79 |

0.45 |

8.33 |

8.33 |

2.9 |

3.67 |

10.6 |

| BEM |

40.8 |

415.8 |

578.9 |

273.3 |

5.82 |

0.49 |

8.32 |

8.14 |

2.92 |

3.62 |

10.7 |

| BPPGR |

38.8 |

462.8 |

610.4 |

308.8 |

5.31 |

0.48 |

8.35 |

8.16 |

2.58 |

3.60 |

8.6 |

| BCH |

39.9 |

489.7 |

651.2 |

327.3 |

5.15 |

0.49 |

8.24 |

8.12 |

2.97 |

3.64 |

13.6 |

| BCV |

41.7 |

427.1 |

565.4 |

288.3 |

5.43 |

0.43 |

8.3 |

8.14 |

2.82 |

3.55 |

12.5 |

| BCC |

38.1 |

437.5 |

561.3 |

288.2 |

5.72 |

0.54 |

8.27 |

8.15 |

2.97 |

3.69 |

13.4 |

| BBP |

39.5 |

402.7 |

560.0 |

269.2 |

6.66 |

0.44 |

8.28 |

8.11 |

2.82 |

3.45 |

10.4 |

| BCONTROL |

40.7 |

425.4 |

574.1 |

281.3 |

5.20 |

0.43 |

8.27 |

8.14 |

2.83 |

3.62 |

13.4 |

Table 3.

Metagenome data referring to the number of reads, number of genera and species, and % of bacteria, eukaryotes and others, of the different formulations of the bokashi-type biofertilizer. Sequencing carried out by the company Lagbio – Metagenomic Analysis and Biotechnology. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

Table 3.

Metagenome data referring to the number of reads, number of genera and species, and % of bacteria, eukaryotes and others, of the different formulations of the bokashi-type biofertilizer. Sequencing carried out by the company Lagbio – Metagenomic Analysis and Biotechnology. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

| Treatments |

Reads |

Genus |

Species |

Bacteria % |

Eukaryota % |

Other %* |

| BBAC |

197.097 |

1187 |

4038 |

99.63 |

0.15 |

0.23 |

| BEM |

230.084 |

1296 |

4872 |

99.61 |

0.16 |

0.22 |

| BPPGR |

261.919 |

1403 |

5169 |

99.62 |

0.23 |

0.15 |

| BCH |

327.408 |

1550 |

6024 |

99.65 |

0.13 |

0.22 |

| BCV |

285.633 |

1422 |

5360 |

99.66 |

0.17 |

0.17 |

| BCC |

353.064 |

1587 |

6359 |

99.67 |

0.13 |

0.19 |

| BBP |

458.348 |

1728 |

7286 |

99.63 |

0.17 |

0.19 |

| BCONTROL |

348.092 |

1507 |

6081 |

99.68 |

0.17 |

0.15 |

| Treatments |

BBAC |

BEM |

BPPGR |

BCH |

BCV |

BCC |

BBP |

BCONTROL |

| Bacteria (genus)1 |

---------% DNA G-1

|

| Marinobacter sp. |

22.72 |

21.01 |

17.91 |

22.20 |

27.30 |

23.88 |

21.08 |

25.37 |

| Halomonas sp. |

9.09 |

9.96 |

7.50 |

7.63 |

7.30 |

8.88 |

8.03 |

9.19 |

| Galbibacter sp. |

7.19 |

2.86 |

11.58 |

9.71 |

5.95 |

7.89 |

7.97 |

4.44 |

| Alcanivorax sp. |

6.12 |

7.24 |

7.28 |

6.65 |

6.00 |

6.07 |

5.95 |

7.28 |

| Azospirillum sp. |

1.42 |

2.44 |

1.59 |

1.67 |

1.79 |

1.72 |

1.51 |

2.20 |

| Bacillus sp. |

2.88 |

2.19 |

2.12 |

2.14 |

2.06 |

2.45 |

2.32 |

2.33 |

| Bradyhizobium sp. |

0.14 |

0.18 |

0.26 |

0.15 |

0.39 |

0.12 |

0.12 |

0.26 |

| Burkholderia sp. |

0.12 |

0.15 |

0.12 |

0.12 |

0.13 |

0.12 |

0.11 |

0.13 |

| Cupriavidus sp. |

0.06 |

0.07 |

0.06 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

| Curtobacterium sp. |

0.08 |

0.15 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

0.11 |

0.09 |

0.08 |

0.11 |

| Paenibacillus sp. |

0.13 |

0.22 |

0.30 |

0.17 |

0.10 |

0.16 |

0.21 |

0.10 |

| PParaburkholderia sp. |

0.08 |

0.10 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

0.09 |

0.07 |

0.09 |

| Pseudomonas sp. |

2.20 |

2.96 |

2.20 |

2.32 |

2.45 |

2.27 |

2.02 |

2.31 |

| Rhizobium sp. |

0.12 |

0.17 |

0.12 |

0.12 |

0.11 |

0.13 |

0.11 |

0.10 |

| Streptomyces sp. |

2.08 |

2.87 |

2.00 |

2.12 |

2.40 |

2.03 |

1.81 |

2.35 |

| Idiomarina sp. |

1.49 |

1.46 |

2.14 |

1.85 |

0.82 |

1.33 |

1.30 |

0.69 |

| Brachybacterium sp. |

1.48 |

1.92 |

1.04 |

1.05 |

1.59 |

1.38 |

1.32 |

1.95 |

| Georgina sp. |

1.47 |

2.24 |

1.20 |

1.24 |

1.82 |

1.59 |

1.40 |

2.02 |

| Others |

41.12 |

41.82 |

42.44 |

40.66 |

39.56 |

39.76 |

44.59 |

39.02 |

Table 4.

Average values of shoot fresh mass (SFM), shoot dry mass (SDM), root fresh mass (RFM), root dry mass (RDM), leaf area index (LAI), mean transversal diameter of tuberous root sugar beet (MTD) and commercial classification of “Katrina” variety beet plants in the field. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

Table 4.

Average values of shoot fresh mass (SFM), shoot dry mass (SDM), root fresh mass (RFM), root dry mass (RDM), leaf area index (LAI), mean transversal diameter of tuberous root sugar beet (MTD) and commercial classification of “Katrina” variety beet plants in the field. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

| Treatments |

SFM

(g) |

SDM

(g) |

RFM

(g) |

RDM

(g) |

LAI

(cm²) |

ATD

(mm) |

Class |

| BBAC |

157.5 b |

80.0 ns

|

217.0 bcd |

16.3 cd |

1355.3 b |

66.3 cd |

2A |

| BEM |

177.3 ab |

95.7 |

217.5 bcd |

17.7 bc |

1474.6 ab |

69.2 bcd |

2A |

| BPPGR |

169.1 ab |

85.9 |

167.0 d |

13.2 d |

1516.1 ab |

64.1 d |

2A |

| BCH |

198.5 ab |

99.6 |

271.3 ab |

21.1 ab |

1620.0 ab |

74.4 ab |

2A |

| BCV |

209.2 a |

97.7 |

253.8 ab |

14.7 cd |

1646.1 ab |

72.7 abc |

2A |

| BCC |

187.5 ab |

93.9 |

218.6 bcd |

17.0 bcd |

1958.6 a |

69.7 abcd |

2A |

| BBP |

198.3 ab |

102.7 |

282.0 a |

22.4 a |

1763.5 ab |

76.3 a |

2A |

| BCONTROL |

169.3 ab |

82.1 |

227.9 abc |

18.1 abc |

1421.9 b |

70.9 abc |

2A |

| CSCONTROL |

168.3 ab |

83.1 |

175.3 cd |

12.5 d |

1402.8 b |

68.0 bcd |

2A |

| CV (%) |

17.97 |

17.14 |

17.81 |

18.09 |

22.64 |

6.59 |

- |

Table 6.

Mean values, shoot fresh mass (SFM), number of external leaves (NEL), number of leaves on the head (NLH), head transverse diameter (HTD) and head fresh mass (HFM) of “Chato de Quintal” variety cabbage plants produced with bokashi-type biofertilizer formulations. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

Table 6.

Mean values, shoot fresh mass (SFM), number of external leaves (NEL), number of leaves on the head (NLH), head transverse diameter (HTD) and head fresh mass (HFM) of “Chato de Quintal” variety cabbage plants produced with bokashi-type biofertilizer formulations. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

| Treatments |

SFM (g) |

NEL |

HTD (cm) |

NLH |

HFM (g) |

| BBAC |

1609.8 bc |

13 b |

17.8 c |

25 ab |

884.5 bc |

| BEM |

2123.3 ab |

13 b |

20.6 abc |

30 a |

1343.2 ab |

| BPPGR |

2162.4 ab |

15 ab |

20.5 abc |

23 b |

1284.0 ab |

| BCH |

2010.5 ab |

17 a |

20.8 abc |

26 ab |

1208.9 ab |

| BCV |

2067.8 ab |

14 ab |

20.6 abc |

26 ab |

1250.3 ab |

| BCC |

2494.7 a |

16 ab |

22.1 a |

26 ab |

1433.4 a |

| BBP |

2038.0 ab |

14 ab |

21.5 a |

26 ab |

1213.7 ab |

| BCONTROL |

2101.3 ab |

15 ab |

21.3 ab |

31 a |

1250.8 ab |

| CSCONTROL |

1246.3 c |

15 ab |

18.2 bc |

26 ab |

587.1 c |

| CV (%) |

23.95 |

15.21 |

10.66 |

15.29 |

24.5 |

Table 7.

Mean values of the chemical composition of the aerial part of the cabbage plants variety “Chato de Quintal”, N, K Ca and Mg content in % and their respective accumulations in mg. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

Table 7.

Mean values of the chemical composition of the aerial part of the cabbage plants variety “Chato de Quintal”, N, K Ca and Mg content in % and their respective accumulations in mg. Lages, Santa Catarina State, Brazil, 2021.

| Treatments |

N |

P |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

| --------------- % --------------- |

|---|

| BBAC |

3.5 ab |

1.3 c |

6.1 a |

0.40 ab |

0.29 ab |

| BEM |

2.5 c |

1.5 bc |

5.1 ab |

0.25 cd |

0.26 ab |

| BPPGR |

3.1 bc |

1.7 ab |

5.9 a |

0.27 cd |

0.26 ab |

| BCH |

3.6 ab |

1.4 c |

5.0 ab |

0.23 d |

0.25 b |

| BCV |

3.4 ab |

1.5 bc |

4.8 ab |

0.32 abcd |

0.28 ab |

| BCC |

3.6 ab |

1.3 c |

4.9 ab |

0.40 a |

0.28 ab |

| BBP |

2.7 c |

1.4 c |

5.6 ab |

0.36 abc |

0.30 a |

| BCONTROL |

3.5 ab |

1.4 c |

5.1 ab |

0.27 bcd |

0.26 ab |

| CSCONTROL |

4.0 a |

1.8 a |

4.3 b |

0.34 abcd |

0.28 ab |

| Ref. values¹ (%) |

4.0 - 4.5 |

0.4 – 0.5 |

2.5 – 2.7 |

0.75 |

0.25 |

| CV (%) |

13.34 |

16.63 |

16.42 |

26.99 |

12.37 |

| Treatments |

N accumulated |

P accumulated |

K accumulated |

Ca accumulated |

Mg accumulated |

| --------------- mg-1 --------------- |

| BBAC |

263.4 b |

104.1ns

|

428.1 ab |

28.8 ab |

21.1 ab |

| BEM |

200.1 b |

118.8 |

388.6 ab |

18.4 b |

19.9 b |

| BPPGR |

278.8 ab |

155.1 |

542.1 a |

22.9 b |

22.8 ab |

| BCH |

289.9 ab |

119.7 |

416.6 ab |

18.8 b |

20.9 ab |

| BCV |

285.2 ab |

125.4 |

400.1 ab |

27.3 ab |

23.1 ab |

| BCC |

405.8 a |

147.8 |

558.2 a |

36.1 a |

28.2 a |

| BBP |

221.2 b |

120.1 |

450.5 ab |

28.6 ab |

24.6 ab |

| BCONTROL |

306.3 ab |

124.3 |

451.9 ab |

21.8 b |

22.1 ab |

| CSCONTROL |

275.5 ab |

124.4 |

298.5 b |

21.6 b |

18.4 b |

| (CV%) |

34.14 |

42.80 |

29,25 |

33.49 |

25.05 |