Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Design

2.2. Soil Greenhouse Gas Flux Measurement

- F: Gas flux (mg m⁻2 h⁻¹)

- S: Slope of gas concentration increase over time (ppm s⁻¹)(CH₄:20s;N₂O:20s;CO₂:30s)

- V: Volume of the chamber (L)

- tc:Time conversion constant, N₂O:20s:180 = (1 h × (60 min/hour) × ((60 s/min)/20s);CO₂:120 = (1 h × (60 min/hour) × ((60 s/min)/30s);

- M: Molecular weight of the gas (g mol⁻¹)

- R: Ideal gas constant (0.082 L atm mol⁻¹ K⁻¹)

- T: Absolute temperature (K)

- 1000: Unit conversion factor (1 mg = 1000 µg)

- A: Area of the chamber base (m2)

2.3. Photosynthetic Carbon Assimilation Measurement

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

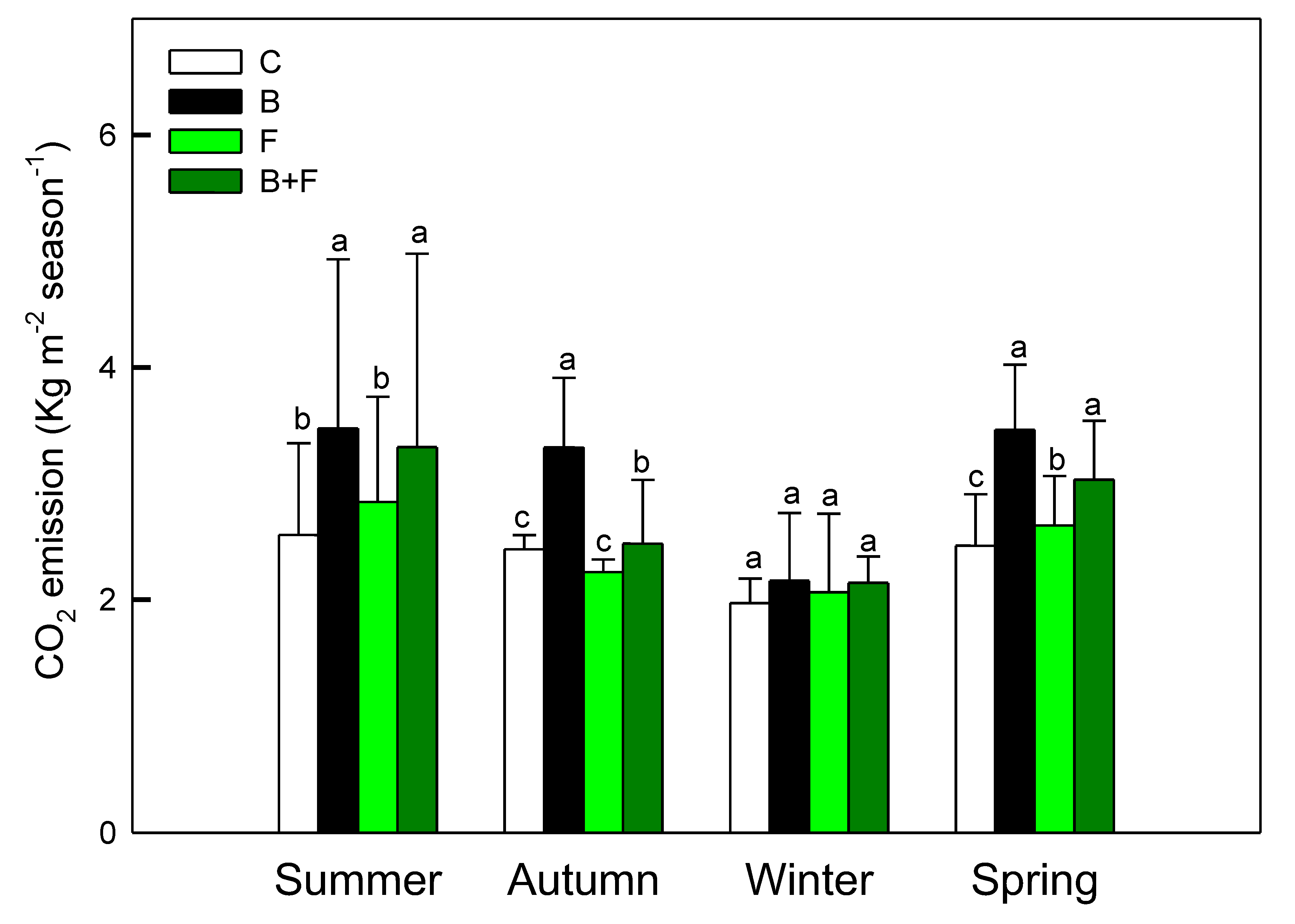

3.1. Seasonal Variation in CO₂ Emissions

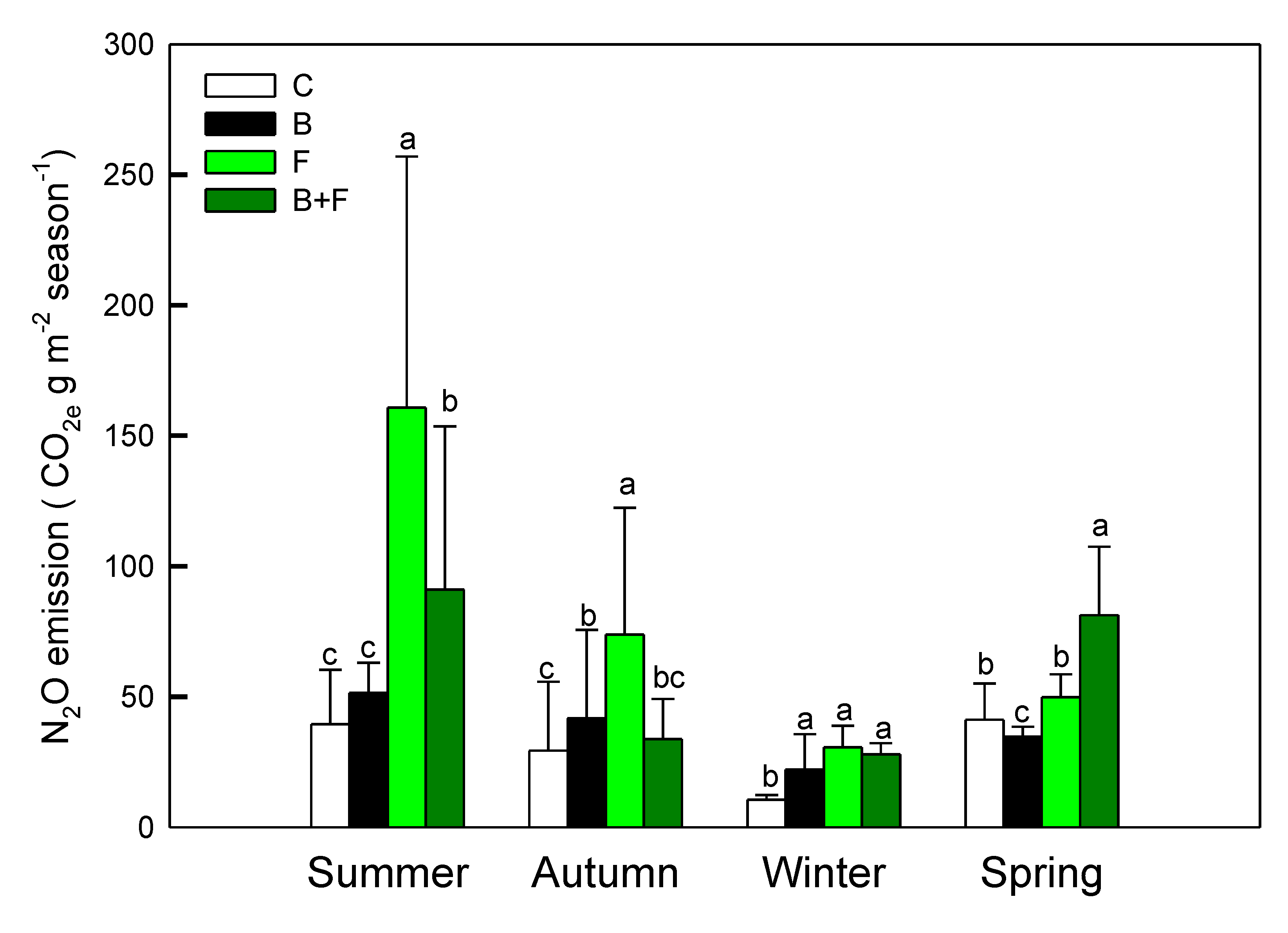

3.2. N₂O Emissions and Fertilizer Response

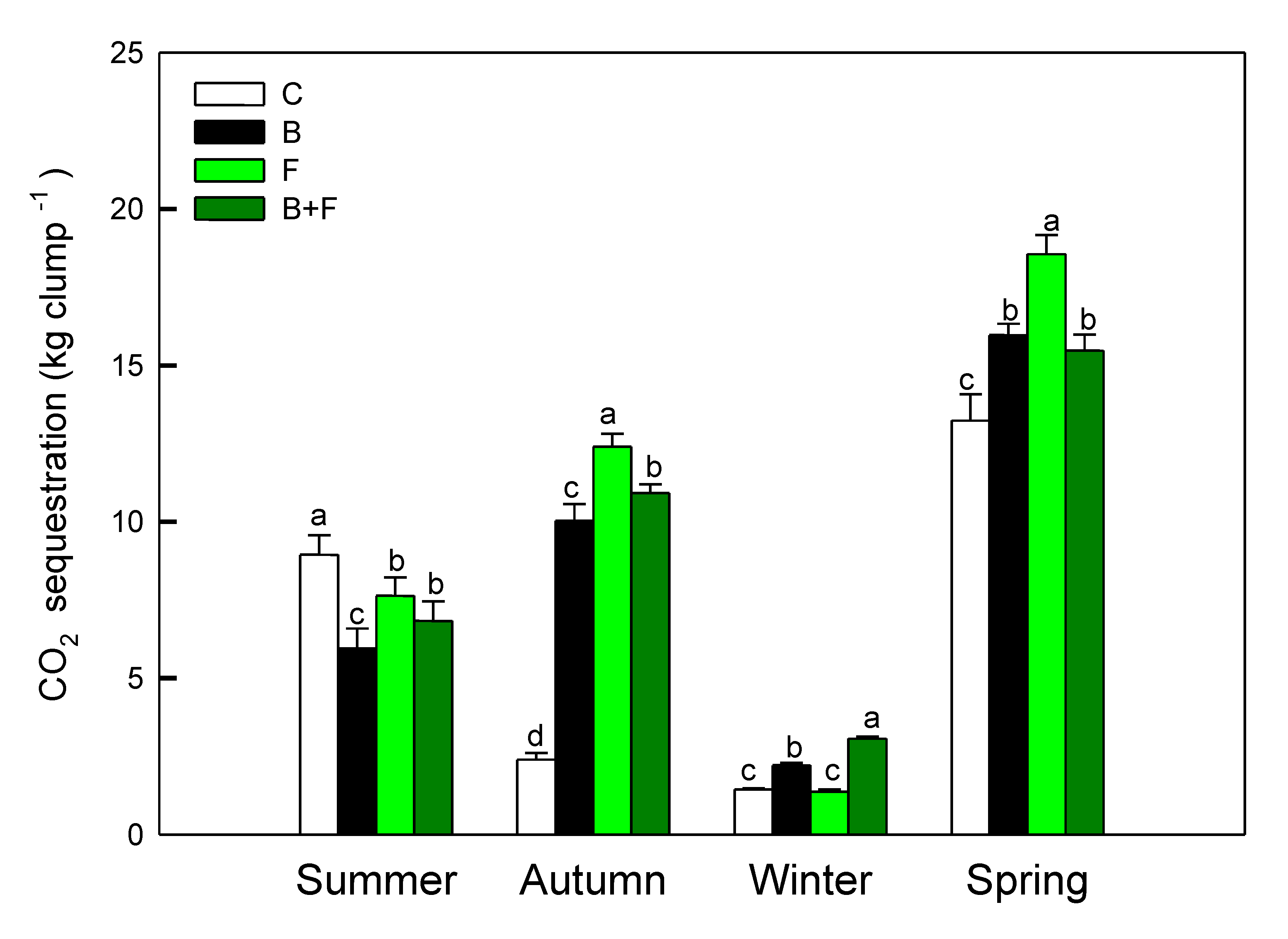

3.3. Carbon Assimilation Performance

| temperature | rainfall | CO2 | N2O | |

| temperature | 1 | .768** | .867** | .763** |

| rainfall | - | 1 | .854** | .857** |

| CO2 | - | - | 1 | .714* |

| N2O | - | - | - | 1 |

4. Discussion

4.1. CO₂ Emissions

4.2. N₂O Emissions and Nitrogen Transformation Pathways

4.3. Carbon Assimilation and Photosynthetic Response

4.4. Management Implications for Bamboo Agroecosystems

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Intergov. Panel Clim. Change 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-synthesis-report (accessed on 2025.6.25).

- Seddon, N.; Chausson, A.; Berry, P.; Girardin, C.A.J.; Smith, A.; Turner, B. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2020, 375, 20190120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi). Foundations for Science-Based Net-Zero Target Setting in the Corporate Sector; SBTi: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/foundations-of-net-zero.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- TNFD. The LEAP Approach: A Technical Guidance for Nature-Related Risk and Opportunity Assessment; Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures: Geneva, 2022; Available online: https://tnfd.global (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Zhou, G.; Jiang, P.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y. Carbon balance of a managed Chinese fir plantation ecosystem in sub-tropical China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 212, 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Zhou, G.; Jiang, H.; Yu, S.; Fu, J.; Li, W.; Wang, W.; Ma, Z.; Peng, C. Carbon sequestration by Chinese bamboo forests and their ecological benefits: Assessment of potential, problems, and future challenges. J. For. Res. 2011, 22, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Xie, Z. Long-term carbon input through plant residues and biochar improves soil carbon stock and maize productivity in a subtropical agroecosystem. Field Crops Research 2025, 299, 110040. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.-H.; Wang, S.-C.; Lin, H.-J. Toward national accounting of bamboo-based carbon sinks: Lessons from Taiwan. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Hsu, L. Bio-based nutrient strategies for emission reduction in bamboo plantations. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 43, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Antal, M.J.; Grønli, M. The art, science, and technology of charcoal production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 1619–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, S.; Bezemer, T.M.; Cornelissen, G.; Kuyper, T.W.; Lehmann, J.; Mommer, L.; et al. The way forward in biochar research: Targeting trade-offs between the potential wins. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 2015, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, C.; Yu, M.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Biochar Application Improves Soil Nutrient Availability and Crop Yield by Regulating Enzyme Activity and Microbial Community in Maize Field. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 2992–3007. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, P.; Bhatia, A.; Kumar, R. Biochar and Nitrogen Fertilizer Application Improves Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Maize Yield in Semi-Arid Regions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14523. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Biochar for environmental management: An introduction. In Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. (Eds.), Ed.; Biochar for Environmental Management; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.Z.; Pan, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C. Effects of biochar application on fluxes of three biogenic greenhouse gases: A meta-analysis. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2016, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, J.; Müller, K.; Li, Y.; Fu, W.; et al. Effects of biochar application in forest ecosystems on soil properties and greenhouse gas emissions: A review. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 546–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Yi, Q.; Xu, M.; Zheng, J.; Pan, G. Biochar improves soil organic carbon stability by shaping the microbial community structures at different soil depths four years after incorporation in a farmland soil. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 5, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-C.; Huang, M.-Y.; Chen, C.-I.; Lin, C.-H.; Huang, W.-H.; Lee, L.-H.; Wang, C.-W. Assessing the benefits of alternating wet and dry (AWD) irrigation of rice fields on greenhouse gas emissions in central Taiwan. Taiwania 2025, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-W.; Lin, K.-H.; Feng, Y.-Z.; Lin, Y.-W.; Yang, Z.-W.; Chen, C.-I.; Huang, M.-Y. Effects of crop rotation and tillage on CO₂ and CH₄ fluxes in paddy fields. Taiwania 2025, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, D.; Amonette, J.E.; Street-Perrott, F.A.; Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Sustainable biochar to mitigate global climate change. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, L.A.; Harpole, W.S. Biochar and its effects on plant productivity and nutrient cycling: A meta-analysis. GCB Bioenergy 2013, 5, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.M.; Lima, I.M.; Xing, B.; Gaskin, J.W.; Steiner, C.; Das, K.C.; Schomberg, H.H. Characterization of designer biochar produced at different temperatures and their effects on a loamy sand. Ann. Environ. Sci. 2014, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Cui, K.; Wu, Z.; Shi, M.; Song, X. Biochar amendment alters the nutrient-use strategy of Moso bamboo under N additions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 667964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirahmadi, E.; Ghorbani, M.; Adani, F. Biochar contribution in greenhouse gas mitigation and crop yield considering pyrolysis conditions, utilization strategies and plant type – A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2025, 333, 110040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Huang, L.C.; Chang, C.T.; Sung, H.Y. Purification and characterization of soluble invertases from suspension-cultured bamboo (Bambusa edulis) cells. Food Chem. 2006, 96, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pao, S.H.; Wu, H.; Hsieh, H.L.; Chen, C.P.; Lin, H.J. Effects of modulating probiotics on greenhouse gas emissions and yield in rice paddies. Plant Soil Environ. 2024, 71, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-I.; Wang, Y.-N.; Lin, H.-H.; Wang, C.-W.; Yu, J.-C.; Chen, Y.-C. Seasonal Photosynthesis and Carbon Assimilation Dynamics in a Zelkova serrata (Thunb.) Makino Plantation. Forests 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Sun, C. Nitrogen transformation and microbial community analysis in soil under long-term straw returning and chemical fertilizer application. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 419–428. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.P.; Hatton, B.J.; Singh, B.; Cowie, A.L.; Kathuria, A. Influence of biochars on nitrous oxide emission and nitrogen leaching from two contrasting soils. J. Environ. Qual. 2010, 39, 1224–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertel, C.; Matschullat, J.; Zurba, K.; Zimmermann, F.; Erasmi, S. Greenhouse gas emissions from soils—A review. Carbon Balance Manag. 2016, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, W.; Xie, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Fertilizer management effects on carbon dioxide emissions from vegetable production in China: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 688, 1325–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Raich, J.W.; Tufekciogul, A. Vegetation and soil respiration: Correlations and controls. Biogeochemistry 2000, 48, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subke, J.A.; Inglima, I.; Cotrufo, M.F. Trends and methodological impacts in soil CO₂ efflux partitioning: A meta-analytical review. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, C.; Dong, W.; Li, X. Effect of fertilization on soil respiration and its temperature sensitivity in a winter wheat field. Plant Soil 2011, 343, 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, E.A.; Janssens, I.A.; Luo, Y. On the variability of respiration in terrestrial ecosystems: Moving beyond Q₁₀. Ecology 2006, 87, 2348–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, A.R.; Gao, B.; Ahn, M.Y. Positive and negative carbon mineralization priming effects among a variety of biochar-amended soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 5137–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.; Panzacchi, P.; Biasiol, S.; Tonon, G. Biochar reduces short-term nitrate leaching from A horizon in a silty clay loam soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 512–522. [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbak, I.; Millar, N.; Robertson, G.P. Global meta-analysis of the nonlinear response of soil nitrous oxide (N₂O) emissions to fertilizer nitrogen. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Baggs, E.M. Soil microbial sources of nitrous oxide: Recent advances in knowledge, emerging challenges and future direction. Plant Soil 2011, 339, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Yan, X.; Yagi, K. Evaluation of effectiveness of enhanced-efficiency fertilizers as mitigation options for N₂O and NO emissions from agricultural soils: Meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 1837–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.; Rochette, P.; Whalen, J.K.; Angers, D.A.; Chantigny, M.H. Global nitrous oxide emission factors of mineral and organic fertilizers used in agriculture: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 111, 208–220. [Google Scholar]

- Abalos, D.; Jeffery, S.; Sanz-Cobena, A.; Guardia, G.; Vallejo, A. Meta-analysis of the effect of urease and nitrification inhibitors on crop productivity and nitrogen use efficiency. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 3610–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, A.; Ji, C.; Joseph, S.; Bian, R.; Li, L.; Pan, G.; et al. Biochar’s effect on crop productivity and the dependence on experimental conditions—A meta-analysis of literature data. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 592, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, W.; Yu, G. Responses of N₂O emissions to nitrogen fertilization and environmental factors in global paddy fields. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 513–528. [Google Scholar]

- Taghizadeh-Toosi, A.; Clough, T.J.; Condron, L.M.; Sherlock, R.R. Biochar incorporation into pasture soil suppresses in situ nitrous oxide emissions from ruminant urine patches. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. A.; Oh, J. H.; Kim, P. J. Evaluation of silicate iron slag amendment on reducing methane emission from flood water rice farming. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2008, 128, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. A.; Lee, C. H.; Lee, Y. B.; Kim, P. J. Silicate fertilization in no-tillage rice farming for mitigation of methane emission and increasing rice productivity. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2009, 132, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreye, C.; Dittert, K.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Lin, S.; Tao, H.; Sattelmacher, B. Fluxes of methane and nitrous oxide in water-saving rice production in North China. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2007, 77, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirahmadi, E.; Ghorbani, M.; Adani, F. Biochar contribution in greenhouse gas mitigation and crop yield considering pyrolysis conditions, utilization strategies and plant type – A meta-analysis. Field Crops Research 2025, 333, 110040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.R. Photosynthesis and nitrogen relationships in leaves of C₃ plants. Oecologia 1989, 78, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, A.; Sakuma, H.; Sudo, E.; Mae, T. Differences between maize and rice in N-use efficiency for photosynthesis and protein allocation. Plant Cell Environ. 2003, 26, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, K.Y.; Quentin, A.G.; Lin, Y.-S.; Medlyn, B.E.; Williams, D.G.; Barton, C.V.M.; Ellsworth, D.S. Photosynthesis of Eucalyptus species along a subambient to elevated CO₂ gradient. Tree Physiol. 2011, 31, 256–267. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.; Martino, D.; Cai, Z.; Gwary, D.; Janzen, H.; Kumar, P.; Smith, J. Greenhouse gas mitigation in agriculture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 118, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agegnehu, G.; Bass, A.M.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.I. Benefits of biochar, compost and biochar–compost for soil quality, maize yield and greenhouse gas emissions in tropical agricultural soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 218, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. (Eds.) Biochar for Environmental Management: Science, Technology and Implementation, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwan EPA. Taiwan's Net-Zero Emissions Pathway; Environmental Protection Administration, Executive Yuan, Taiwan: Taipei, 2022; Available online: https://enews.epa.gov.tw/Page/3B3C62C78849F32F/f4c3c91d-51f9-41a2-850f-cd1a3f94d50f (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Griscom, B.W.; Adams, J.; Ellis, P.W.; Houghton, R.A.; Lomax, G.; Miteva, D.A.; Fargione, J. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11645–11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).