1. Introduction

Approximately one billion hectares of land worldwide are affected to varying degrees by salinity and related threats. The increasing demand for the expansion of intensive irrigated agriculture, rising temperatures, increased drought frequency, and water scarcity have led to the accumulation of salts in soils irrigated with saline water. These conditions exacerbate salinization, sodication, and high sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), degrading the chemical environment and the physical health of soils [

1]. Salinity adversely affects crop growth and yield, posing serious challenges to food security and economic stability in affected regions [

2,

3]. In Peru, salinization has been reported on approximately 300,000 hectares of irrigated land, with nearly 150,000 hectares exhibiting high salinity levels. It is estimated that around 40% of the total agricultural area along the Peruvian coast is affected by soil salinity [

4].

In this context, there is a need to develop sustainable agricultural practices that can improve soil quality in saline environments while contributing to circular economy models. Among such practices, the use of biochar, a stable, carbon-rich byproduct from pyrolysis, has gained attention for its capacity to improve soil health and mitigate environmental stress. Biochar has demonstrated residual effects in reducing sodium (Na⁺) uptake under saline stress conditions, through mechanisms such as Na⁺ sorption, increased soil moisture retention, and the supply of essential nutrients that could reduce Na⁺ uptake by plants [

5]. Additionally, its alkaline nature, structural stability, and potential to sequester carbon make it a promising tool for improving agricultural productivity, reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and promoting soil regeneration [

6].

Similarly, previous studies had mentioned that vermicompost and organic amendments are a cost-effective and sustainable approach to improving soil quality in salt-affected regions and boosting crop yields in areas with severe salinity issues [

7,

8]. Also, vermicompost is rich in essential nutrients, humic acids, growth-regulating hormones, and enzymes, enhancing plant nutrition, boosting photosynthesis, improving overall crop quality, and offering potential benefits for pest control [

9]. In this sense, vermicompost leachate (or “vermiwash”) has demonstrated noticeable effects on plants and soil. It was found to possess properties that function as a liquid organic biofertilizer and a biopesticide [

10]. Both amendments originate from agricultural residues, aligning with the principles of circular agriculture by promoting resource efficiency, reducing waste, and enhancing soil resilience.

Nevertheless, despite their benefits, knowledge gaps remain regarding the comparative performance of biochar and vermicompost leachate under salinity stress conditions, especially in coastal agroecosystems. Moreover, potential limitations have been reported. For biochar, ecotoxicological impacts and interactions with soil microbiota, such as negative effects on nitrogen-fixing Rhizobium and phosphorus-mobilizing mycorrhizal fungi, have been observed under arid conditions; however, these may be mitigated when combined with microbial inoculants [

11,

12]. Although rich in nutrients, Vermicompost may pose environmental risks due to nutrient leaching, unpleasant odors, insect proliferation, and GHG emissions during decomposition, especially when not properly managed [

13].

Yellow hard corn is cultivated nearly year-round in Peru, particularly along the Peruvian coast. It is a short-cycle crop with a vegetative period ranging from 4.5 to 5.5 months, depending on the variety and sowing date. Popcorn varieties are characterized by small, round kernels with a soft, starchy core and a hard, glassy outer shell; when heated, the moisture within the starchy core expands and bursts through the hard shell, producing popcorn. These varieties account for less than 1% of global corn production [

14]. The consumption of popcorn maize (

Zea mays var. everta) in Peru has increased significantly, particularly in recent years, with an annual growth rate of 5,527.6 tons (2016-2020). However, Peru imports popcorn maize from three main countries, in descending order of volume: Argentina, Brazil, and the United States [

15].

Considering the growing salinization of coastal agricultural soils and the increasing interest in sustainable crop production, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of two organic amendments—biochar and vermicompost leachate—on soil quality, microbial community, and the growth and yield performance of popcorn maize. The focus was to assess their comparative performance under saline soil conditions and contribute to the understanding of how organic inputs derived from agricultural residues influence crop productivity and soil health in salt-affected environments of the Peruvian coast.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

The study was conducted at the Agricultural Research and Technology Transfer Unit in Organic Solid Waste Management of the “Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria” (INIA). The geographic coordinates are 12° 04' 29.2" S, 76° 56' 26.3" W, and the altitude is 241 m.s.n.m.

The greenhouse where the experiment was conducted had the following dimensions: 10.2 x 8 x 2.7 m.

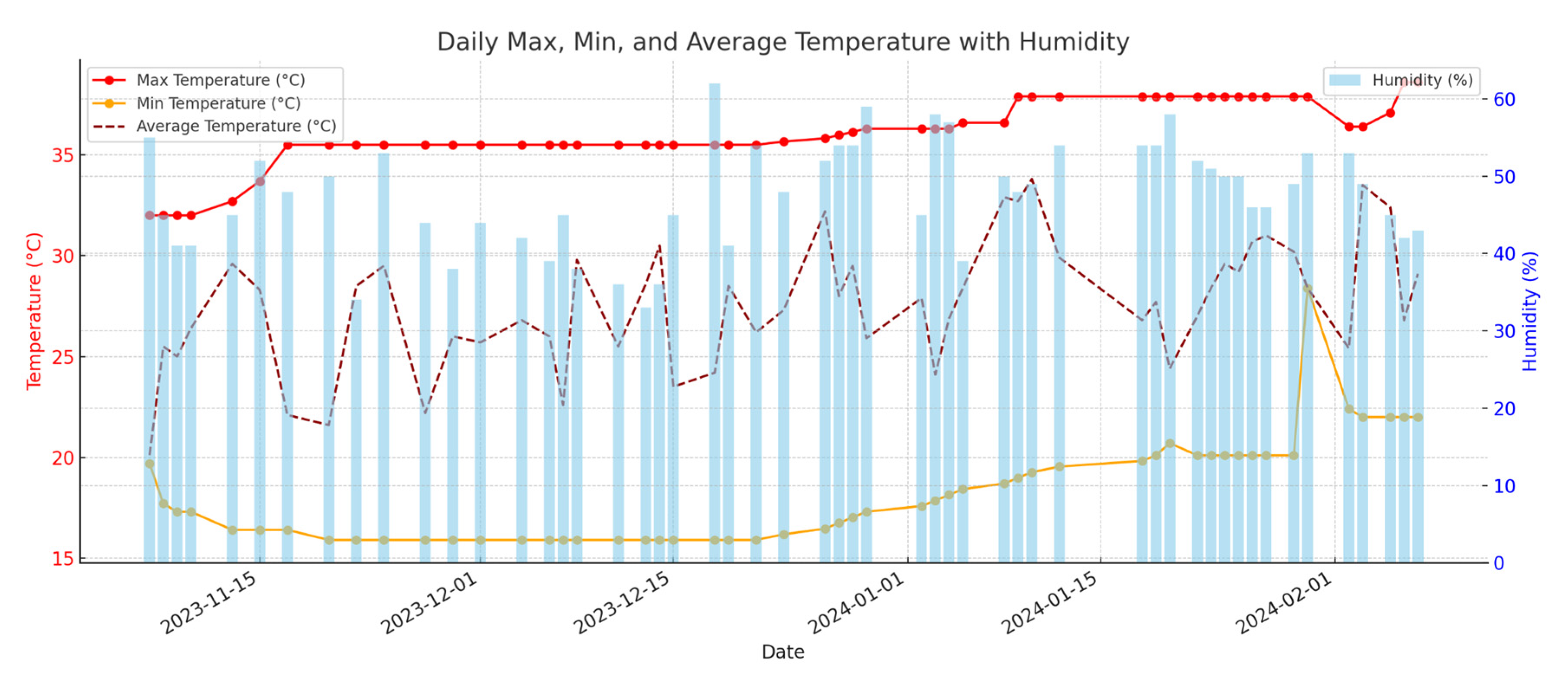

Figure 1 shows the climatic values of temperature and relative humidity. The entire crop cycle was from November 2023 to March 2024.

2.2. Substrates, Water, and Seed Characteristics

2.2.1. Soil

Soil from the “Fertilizantes Orgánicos S.A.C” (FOSAC) company located in the Pachacamac district, province, and department of Lima, was used. The geographic coordinates are 12° 13' 34.3" S, 76° 52'37.4" W. Sampling was conducted at a depth of 0 to 20 cm. The soil was then moved to INIA - Lima, and the soil was extended, homogenized, and air-dried for a week. After this time, it was de-clumped and homogenized again.

A sample was analyzed to obtain the soil characterization, which was realized by the “Laboratorio de Análisis de Suelos, Aguas y Foliares” at INIA - Lima (

Table 1).

The soil had a sandy loam texture, a slightly alkaline reaction, a low CaCO3 content, and was strongly saline. The organic matter, total carbon, and total organic carbon were low, and the available phosphorus and potassium were high. The cation exchange capacity (CEC) was high and had sufficient Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, and Na+ levels. Concerning the metal concentration, the soil would not be contaminated according to Peruvian legislation (Supreme decree N° 011-2017-MINAM); however, it had an elevated concentration of As according to the Canadian Soil Quality Guidelines for the Protection of Environmental and Human Health (> 12 mg kg-1).

2.2.2. Biochar

The technology employed for biochar production was based on Top-Lit UpDraft (TLUD) micro-gasifier and produced from rice husks. This method loads biomass into a combustion chamber and ignites from the top (top-lit). As the combustion progresses downward, pyrolysis gases are released and move upward (updraft) through the unburned biomass. These gases are subsequently combusted in the upper zone of the reactor under limited oxygen conditions. This controlled combustion at 700 °C resulted in the partial conversion of biomass, allowing a solid carbon-rich residue known as biochar. TLUD systems offer several advantages, including high energy efficiency, reduced smoke emissions, low operational costs, and suitability for small-scale or decentralized applications.

This amendment was characterized by a proportion of 1:10 [

16], obtaining pH 9.07 and EC 2.473 values.

2.2.3. Vermicompost Leachate

The vermicompost, derived from pre-compost (

Cavia porcellus manure and harvest residues), was processed using earthworms (

Eisenia foetida). The production bed had a width of 1.75 m, a length of 3.65 m, a depth of 70 cm, a channel of 16 cm, and an outlet of 50 cm. Earthworms were incorporated at a ratio of 1 kg per 4 kg of pre-compost and maintained under composting conditions for three months. Subsequently, the resulting vermicompost was flushed with water to extract the leachate, which was then brewed for 48 hours and collected in the system's reservoir. The characterization was carried out. following a proportion of 1:5 [

16], obtaining a pH of 8.40 and an EC of 3.34 dS m

-1.

2.2.4. Irrigation Water

The water had an almost constant pH of 7.7 and EC of 0.619 dS m-1.

2.2.5. Plant Material

PMC.S1 x 8-8 maize seeds were used in this study. This is an experimental hybrid resulting from the cross of two S1 lines. PMC is an S1 line derived from commercial popcorn, while 8-8 is another S1 line obtained from a segregating population originating from the cross between the races Kculli x Confite Puneño. These seeds were provided by the Maize Program of the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina (UNALM).

2.3. Treatments and Experimental Design

We used 5 L pots, and a volume of 4 L was filled with soil and amendments according to treatments (

Table 2).

For T1, the vermicompost leachate was fermented with sugar (40 g) per 2 L of solution for 72 hours, then applied four times, once at the beginning of each week, for one month. The first application occurred one week before sowing. A total volume of 8 L was applied to each pot by the end of the treatment period.

In T2, biochar was mixed into the top 15 cm of soil depth [

17], at a rate of 150 g per pot. In T3, biochar (375 g), vermicompost leachate (2 L), and sugar (20 g) were mixed and fermented for 72 hours. The mixture was applied in the same manner as T1, four times over one month. The first application was made one week before sowing, with the subsequent applications carried out around the base of the plant.

The experimental design was a Completely Randomized Design (CRD) with three treatments and one absolute control. Each treatment had ten replicates with two plants per pot, being a total of 40 experimental units.

2.4. Installation Procedure

Each pot was filled with 5.6 kg of air-dried (equivalent to 4 L), previously crumbled soil. Three maize seeds were sown in each pot, and one week after germination, the two most vigorous plants were selected and the third was removed. Each pot received the recommended fertilizer dose for popcorn maize, corresponding to 150-80-100 kg ha⁻¹ of NPK (UNALM Maize Program), using the chemical fertilizers urea, diammonium phosphate, and potassium nitrate, where urea application was split into two doses, and weeds were removed manually. The entire crop cycle was from November 2023 to March 2024.

2.5. Soil Parameters

At harvest, soil from each experimental unit was removed from the pots. Samples were sent to the “Laboratorio de Suelos, Agua y Foliares” at INIA (Lima) for physico-chemical analysis, and to the “Laboratorio de Ecología Microbiana y Biotecnología” at UNALM for microbiological analysis.

The physico-chemical analysis included determination of texture using the Bouyoucos method [

18], pH measurement with an inoLab® pH 7310 meter, and electrical conductivity (EC) assessed in the saturation extract using an inoLab® Cond 7310. Total carbon (TC), total organic carbon (TOC), and total nitrogen (TN) were quantified through dry combustion with an elemental analyzer (LECO CN828, LECO Ltd., Germany). Extractable phosphorus (Pₐ) was analyzed using the Olsen method [

19]. Additionally, extractable potassium (Kₐ) and exchangeable cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Na⁺) were measured using ammonium saturation, while total metal content and heavy metals were determined via inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) with a Perkin Elmer NexION 2000 Series P instrument (Perkin Elmer Inc., USA).

The microbiological analysis counted mesophilic aerobes (CFU g

-1), molds and yeasts (CFU g

-1), actinomycetes (CFU g

-1), and

Bacillus spp. (CFU g

-1), and enumerated

Pseudomonas spp. (MPN g

-1) [

20,

21].

2.6. Agronomic Parameters

The biometric variables—plant height (cm) and stem diameter (mm)—were measured at the end of the maize vegetative growth stage, approximately 80 days after sowing. We measured plant height from the plant collar to the last visible node on the stem. A caliper was used to measure stem diameter at the center of the first internode emerging from the soil; an average was taken between the largest and smallest diameters. The total number of leaves per plant was also recorded around 80 days after sowing. Leaf area was calculated using the Montgomery formula, multiplying the length and width of each leaf by a correction factor of 0.75 and then summing the total leaf area per plant [

22]. At the end of the experimental period, the aerial parts of the plants were collected and weighed to determine fresh weight. To determine dry weight, the samples were then placed in labeled envelopes and dried in an oven at 70°C for ~ 72 hours until a constant weight was obtained [

23].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the R statistical computing environment version 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2023). The data was analyzed with the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality [

24] and Bartlett’s test for homogeneity of variances [

25] at the significance level of p < 0.05. Subsequently, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, and for mean comparisons, Tukey’s test was applied at the significance level of p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have shown that the foliar application of vermicompost leachate can enhance growth and physiological responses in crops under saline conditions. For instance, it promoted the development of pomegranate seedlings by improving tolerance to salinity stress [

26]. Similarly, other research demonstrated that a low dose of solid vermicompost applied before planting improved strawberry yield in the first year; however, in the absence of further fertilization, yields declined to control levels in subsequent years. Although vermicompost leachate did not improve yield, it was associated with better fruit quality [

27]. In our study, a slight reduction in electrical conductivity (EC) was observed in the leachate treatments, although this difference was not statistically significant, suggesting limited efficacy under the experimental conditions.

The chemical characterization of the leachate has an approximate organic matter content of 60%, total humic substances representing 80% of the organic matter, total nitrogen at 2%, and total organic nitrogen at 1.5%. Also, the leachate has an interesting microbial community, among them, amylolytic, cellulolytic, nitrosant, nitricant, sulfate reducers, sulfur oxidants, aerobic nitrogen-fixing, anaerobic nitrogen-fixing, denitrifying, ammonifying, actinomycetes, aerobic, and anaerobic bacteria [

28]. Additionally, a pH of 8.40 and EC of 3.34 dS m

-1 enabled the microbial growth, above all bacteria, for example,

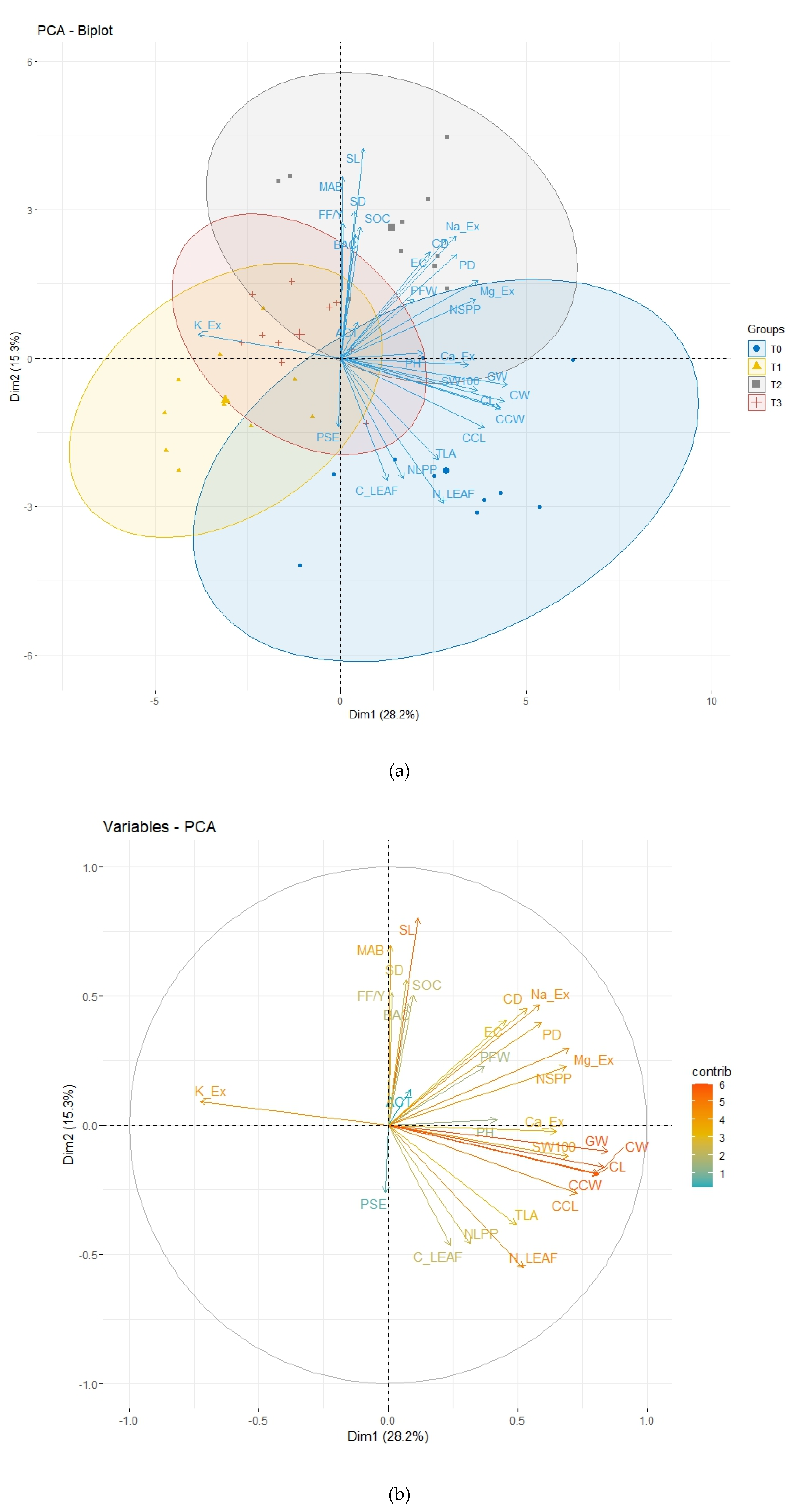

Pseudomonas spp., as they could be seen at PCA for T1. Some authors mentioned that the microbial biomass nitrogen and dehydrogenase enzyme activity were higher after the addition of vermicompost [

29]. All of this leads to the conclusion that the high concentration of applied bacteria but the low content of organic matter in the soil caused a lot of pressure in the microbial ecosystem, and it is presumed that immobilization took place by them.

In addition, vermicompost leachate may contain microbial populations indicative of an incomplete stabilization process, potentially posing phytotoxic or phytopathogenic risks. A study of High-throughput 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing of fresh leachate samples revealed a dominance of Mollicutes, particularly

Acholeplasma, a genus associated with plant pathogenicity. Over time, storage decline Mollicutes and a concurrent enrichment of taxa of plant-beneficial traits, including members of the Rhizobiales and the genus

Pseudomonas. These results underscore the importance of a maturation or storage phase to mitigate potential phytopathogenic risks and enhance the presence of beneficial microbial consortia [

30]; also, the leachate should be characterized in terms of its phytotoxic and phytopathogenic composition to prevent adverse effects.

Likewise, biochar in soils with low organic matter content and high aeration, as is often the case in arid environments, can sometimes limit its benefits. In these systems, limited water availability may suppress the positive effects commonly attributed to biochar, particularly its capacity to enhance nutrient uptake by crops [

12]. Nonetheless, in our experiment, biochar application was associated with improvements in microbial activity and plant growth, despite saline conditions. Also, the soil organic carbon was higher after its application, which gives us the perspective of residual effect and potential for carbon sequestration. Long-term studies are needed to see the residual effect of carbon input to the soil, mesophilic aerobes bacteria, molds, and yeasts.

The observed increase in bacterial abundance under biochar treatment aligns with previous reports indicating that bacteria respond rapidly to environments enriched with labile carbon sources. Furthermore, the microbial response can differ by group; for example, Gram-positive bacteria often rely more heavily on carbon derived from soil organic matter (SOM), while Gram-negative bacteria tend to utilize carbon derived from plant biomass [

31,

32]. Therefore, understanding how biochar influences microbial community structure and metabolism is essential, particularly in degraded or stressed soils. It is well established that organic and biochar-based amendments can significantly reshape the composition and functionality of soil microbial communities, with downstream effects on soil health, nutrient cycling, and crop performance [

33]. In general, biochar is considered non-toxic to soil biota and can promote both plant biomass accumulation and microbial abundance. However, these effects are highly context-dependent, influenced by factors such as biochar feedstock, pyrolysis temperature, application rate, and the baseline properties of the receiving soil [

34]. Interestingly, studies have noted that biochar produced at lower pyrolysis temperatures (<400 °C) may exhibit higher toxicity potential and a greater likelihood of triggering aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated responses in soil organisms, highlighting the importance of carefully selecting and characterizing biochar before use in agricultural systems [

35].

Nevertheless, a Top-Lit UpDraft (TLUD) gasifier, known as the reverse downdraft gasifier, is a type of biomass stove designed for clean, smokeless flame and efficient combustion of solid biomass fuels. It could be used for small-scale energy generation, especially in off-grid or rural areas [

36]. This is important because it is a simple and low-cost biochar production technology suitable for remote areas, which can enhance agricultural production

On the other hand, there are antecedents about the application of activated biochar by vermicompost leachate, which have allowed the colonization and multiplication of bacteria contained in the liquid over biochar particles. It’s important to note that the effects of applying activated biochar to soils can differ based on several factors, including the biochar type, soil composition, and the particular microorganisms present [

37]. Also, it was reported that high salinity soils could be managed through salt leaching by improving the formation of aggregates, aggregate microstructure, and inhibition of nitrogen losses with vermicompost and humic acid fertilizer [

38]; however, it was not evident under the study conditions. Therefore, the combined application would not be the most advisable.

5. Conclusions

While a substantial portion of the soil’s physicochemical, microbiological, and agronomic parameters did not show statistically significant differences compared to the control, biochar application alone led to improvements in key indicators, including total organic carbon and microbial community (mesophilic aerobes, molds, and yeasts). These results confirm the potential of biochar as an effective amendment for enhancing soil quality and supporting plant development in saline environments, not only as a soil conditioner but also as a tool for resilience-building in degraded agroecosystems. Instead, vermicompost leachate may not be suitable as a standalone or complementary amendment under salinity stress, and its presumed agronomic benefits may be overestimated in such contexts.

From an agronomic perspective, the findings are especially relevant for the sustainable cultivation of popcorn maize, a short-cycle and high-demand crop that is gaining commercial interest in Peru. Future research should focus on the long-term environmental fate of these amendments, particularly their mobility in soil, potential for nutrient leaching, previous analysis of phytopathogens, and risks of surface and groundwater contamination. Additionally, further studies are needed to evaluate synergistic strategies, such as combining biochar with beneficial microbial inoculants, to enhance soil functionality and crop productivity under stress-prone conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and L.O.; methodology, R.S. and L.O.; software, W.E.P.; validation, W.E.P. and R.S.; formal analysis, W.E.P. and Y.A.; investigation, B.R.; resources, R.S.; data curation, W.E.P. and Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.R. and W.E.P.; writing—review and editing, W.E.P. and R.S.; visualization, W.E.P.; supervision, R.S.; project administration, R.S.; funding acquisition, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Greenhouse values of temperature and relative humidity.

Figure 1.

Greenhouse values of temperature and relative humidity.

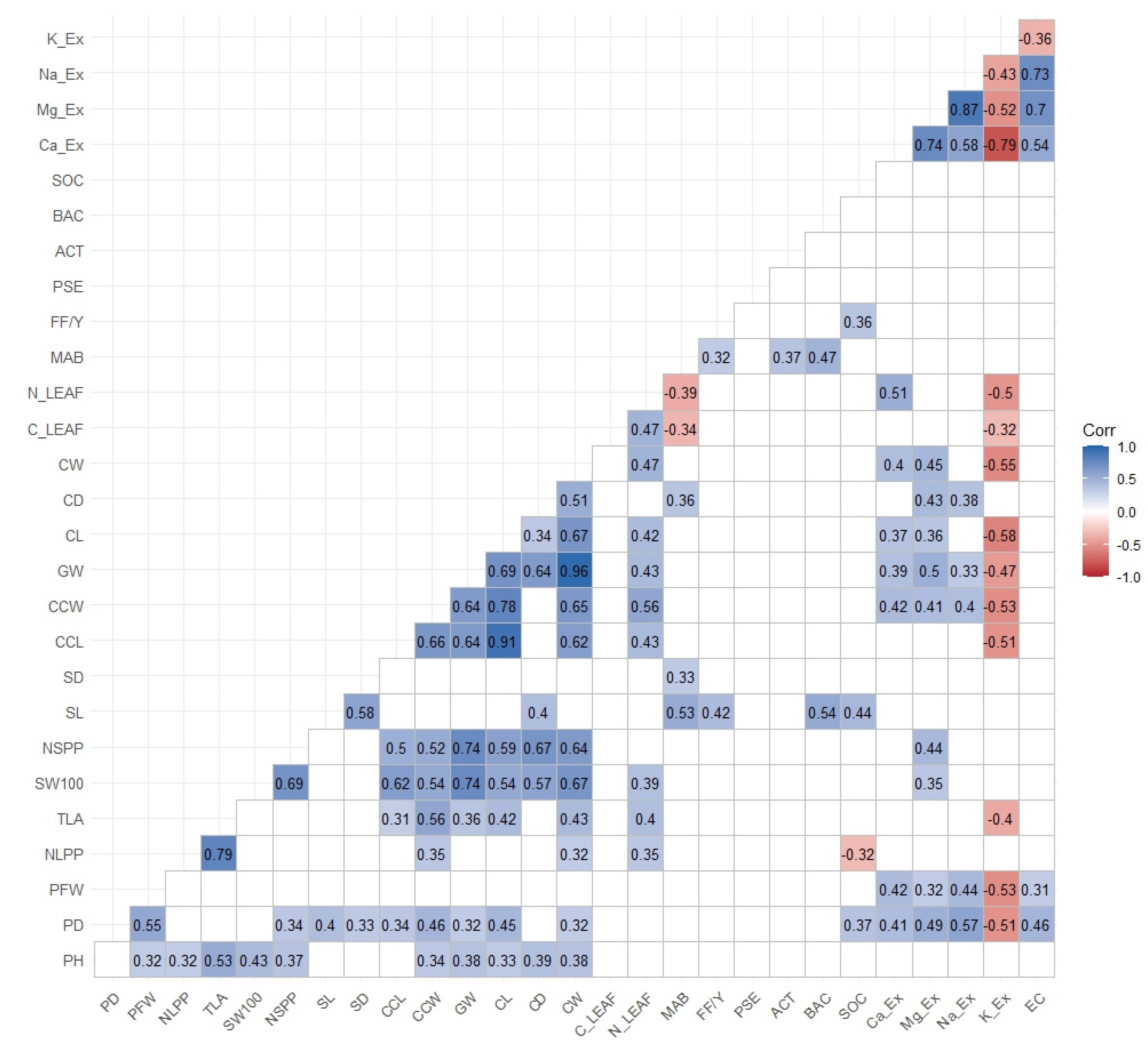

Figure 2.

Pearson correlation between soil and agronomic parameters. Plant Height (PH), Plant Diameter (PD), Plant Fresh Weight (PFW), Number of Leaves per Plant (NLPP), Total Leaf Area (TLA), 100-Seed Weight (100 SW), Number of Seeds per Plant (NSPP), Seed Length (SL), Seed Diameter (SD), Cob Length (CCL), Cob Weight (CCW), Corncob Weight (CW), Corncob Length (CL), Corncob Diameter (CD), Leaf Carbon (C_leaf), Leaf Nitrogen (N_leaf), Mesophilic Aerobic Bacteria (MAB), Filamentous Fungi and Yeast (FF.Y), Pseudomonas (PSE), Actinomycetes (ACT), Bacillus (BAC), Soil Organic Carbon (SOC), Exchangeable Cations (Ca_Ex, Na_Ex, Mg_Ex, K_Ex), Electrical Conductivity (EC).

Figure 2.

Pearson correlation between soil and agronomic parameters. Plant Height (PH), Plant Diameter (PD), Plant Fresh Weight (PFW), Number of Leaves per Plant (NLPP), Total Leaf Area (TLA), 100-Seed Weight (100 SW), Number of Seeds per Plant (NSPP), Seed Length (SL), Seed Diameter (SD), Cob Length (CCL), Cob Weight (CCW), Corncob Weight (CW), Corncob Length (CL), Corncob Diameter (CD), Leaf Carbon (C_leaf), Leaf Nitrogen (N_leaf), Mesophilic Aerobic Bacteria (MAB), Filamentous Fungi and Yeast (FF.Y), Pseudomonas (PSE), Actinomycetes (ACT), Bacillus (BAC), Soil Organic Carbon (SOC), Exchangeable Cations (Ca_Ex, Na_Ex, Mg_Ex, K_Ex), Electrical Conductivity (EC).

Figure 3.

Biplot of Principal Component Analysis (PCA): (a) Individuals and variables for each treatment; (b) Variables contributions. Plant Height (PH), Plant Diameter (PD), Plant Fresh Weight (PFW), Number of Leaves per Plant (NLPP), Total Leaf Area (TLA), 100-Seed Weight (100 SW), Number of Seeds per Plant (NSPP), Seed Length (SL), Seed Diameter (SD), Cob Length (CCL), Cob Weight (CCW), Corncob Weight (CW), Corncob Length (CL), Corncob Diameter (CD), Leaf Carbon (C_leaf), Leaf Nitrogen (N_leaf), Mesophilic Aerobic Bacteria (MAB), Filamentous Fungi and Yeast (FF.Y), Pseudomonas (PSE), Actinomycetes (ACT), Bacillus (BAC), Soil Organic Carbon (SOC), Exchangeable Cations (Ca_Ex, Na_Ex, Mg_Ex, K_Ex), Electrical Conductivity (EC).

Figure 3.

Biplot of Principal Component Analysis (PCA): (a) Individuals and variables for each treatment; (b) Variables contributions. Plant Height (PH), Plant Diameter (PD), Plant Fresh Weight (PFW), Number of Leaves per Plant (NLPP), Total Leaf Area (TLA), 100-Seed Weight (100 SW), Number of Seeds per Plant (NSPP), Seed Length (SL), Seed Diameter (SD), Cob Length (CCL), Cob Weight (CCW), Corncob Weight (CW), Corncob Length (CL), Corncob Diameter (CD), Leaf Carbon (C_leaf), Leaf Nitrogen (N_leaf), Mesophilic Aerobic Bacteria (MAB), Filamentous Fungi and Yeast (FF.Y), Pseudomonas (PSE), Actinomycetes (ACT), Bacillus (BAC), Soil Organic Carbon (SOC), Exchangeable Cations (Ca_Ex, Na_Ex, Mg_Ex, K_Ex), Electrical Conductivity (EC).

Table 1.

Physico-chemical characterization of soil.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical characterization of soil.

| Characteristics |

Unit |

Value |

Method |

| Sand |

% |

69.3 |

Sedimentation |

| Silt |

% |

16.3 |

Sedimentation |

| Clay |

% |

14.4 |

Sedimentation |

| Textural Class |

|

Sandy loam |

Hydrometer Method |

| pH (1:1)

|

--- |

7.7 |

Potentiometer Method (inoLab® pH 7310) |

| EC (e)

|

dS m-1

|

14.2 |

Potentiometer Method (inoLab® Cond 7310) |

| CaCO3

|

% |

2.8 |

Titration Method |

| OM |

% |

0.38 |

Dry Combustion (LECO CN828, LECO Ltd., Germany) |

| TC |

% |

0.83 |

Dry Combustion |

| TOC |

% |

0.22 |

Dry Combustion |

| Pa

|

mg kg-1

|

71.7 |

Modified Olsen Method |

| Ka |

mg kg-1

|

594 |

Ammonium Acetate Extract |

| CEC |

Cmol kg-1

|

23.3 |

Ammonium Acetate Extract |

| Ca2+

|

Cmol kg-1

|

16.8 |

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP - MS) (Perkin Elmer NexION 2000 Series P, Perkin Elmer Inc., USA) |

| Mg2+

|

Cmol kg-1

|

2.8 |

ICP - MS |

| K+

|

Cmol kg-1

|

1.5 |

ICP - MS |

| Na+

|

Cmol kg-1

|

2.2 |

ICP - MS |

| As |

mg kg-1

|

22.34 |

ICP - MS |

| Ba |

mg kg-1

|

62.76 |

ICP - MS |

| Cd |

mg kg-1

|

0.14 |

ICP - MS |

| Cr |

mg kg-1

|

5.4 |

ICP - MS |

| Hg |

mg kg-1

|

0.24 |

ICP - MS |

| Pb |

mg kg-1

|

10.58 |

ICP - MS |

Table 2.

Applied treatments and substrate proportions.

Table 2.

Applied treatments and substrate proportions.

| Treatments |

Proportion in volume |

| Soil |

Biochar |

Vermicompost leachate |

| T0 |

4.0 |

0 |

0 |

| T1 |

3.2 |

0 |

0.8 |

| T2 |

3.2 |

0.8 |

0 |

| T3 |

3.2 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

Table 3.

Values of soil chemical parameters.

Table 3.

Values of soil chemical parameters.

| Treatment |

ECe |

TN |

TOC |

Ca |

K |

Na |

| dS m-1

|

% |

Cmol kg-1

|

| Control |

4.33ab |

0,00112a |

0.734bc |

8.597a |

0.539b |

0.574ab |

| Leachate |

3.43b |

0.0009a |

0.684c |

7.428bc |

1.044a |

0.42b |

| Biochar |

5.55a |

0,00101a |

1.16a |

8.1ab |

0.688b |

0.812a |

| Leachate+Biochar |

3.37b |

0,00093a |

1.037ab |

7.272c |

0.996a |

0.382b |

| p-value |

0.0136 |

0.3451 |

<0.0004 |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

<0.0002 |

| Significance |

* |

ns |

*** |

**** |

**** |

*** |

Table 4.

Quantification and Enumeration of Microbial Composition.

Table 4.

Quantification and Enumeration of Microbial Composition.

| Treatment |

Mesophilic aerobes |

Bacillus spp. |

Actinomycetes |

Molds and yeasts |

Pseudomonas spp. |

| CFU g-1

|

MPN g-1

|

| Control |

2.63x106b |

1.19x106

|

1.91x106

|

1.61x104c |

274.4a |

| Leachate |

3.22x106b |

1.26x106

|

1.86x106

|

2.7x104bc |

89.1a |

| Biochar |

4.47x106a |

1.67x106

|

2.40x106

|

4.65x104a |

173.8a |

| Leachate+Biochar |

3.49x106ab |

1.33x106

|

1.37x106

|

3.65x104ab |

137.3a |

| p-value |

0.0021 |

0.1585 |

0.2029 |

0.0012 |

<0.4741 |

| Significance |

** |

ns |

ns |

** |

ns |

Table 5.

Morphological variables of popcorn maize plants.

Table 5.

Morphological variables of popcorn maize plants.

| Treatment |

Fresh Weight |

Dry Weight |

Number of leaves |

Stem Diameter |

Leaf Area |

Height |

| g |

n° |

cm |

cm2

|

cm |

| Control |

74.48ab |

0.05052a |

6.7a |

10.97ab |

1199a |

145.7a |

| Leachate |

62.74b |

0.05055a |

6.4 ab |

9.61c |

929b |

137.5a |

| Biochar |

79.17a |

0.05063a |

6.1b |

11.83a |

972.8ab |

143.9a |

| Leachate+Biochar |

68.27ab |

0.05057a |

5.9b |

10.4bc |

847.6b |

145.7a |

| p-value |

0.0153 |

0.9268 |

0.0006 |

<0.0001 |

0.0009 |

0.3114 |

| Significance |

* |

ns |

*** |

**** |

*** |

ns |

Table 6.

Corncob variables and Popcorn yield.

Table 6.

Corncob variables and Popcorn yield.

| Treatment |

Grain weight per corncob |

Corncob Length |

Corncob Diameter |

Popcorn Yield |

| g |

cm |

g planta-1

|

| Control |

20.9a |

8.424a |

2.773a |

24.01a |

| Leachate |

10.68b |

5.739c |

2.367b |

13.06c |

| Biochar |

15.12b |

7.681ab |

2.721a |

19.02ab |

| Leachate+Biochar |

14.14b |

6.879bc |

2.655a |

16.65bc |

| p-value |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

0.0003 |

<0.0001 |

| Significance |

**** |

**** |

*** |

**** |