1. Introduction

Lithium recovery is a hot topic in the context of the growing market of new energy-driven vehicles. Manganese-based ion sieves, such as H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 (MnO

2·0.5H

2O) with spinel structure, are currently a research priority in the field of lithium recovery from solution resources due to their lithium selectivity [

1,

2,

3]. These materials provide lithium-ion adsorption sites within their crystalline structure, making them highly selective for this application. The lithiation-delithiation process is analogous to that of a rock-chair battery. As with the disadvantage of manganese-based lithium oxides, tri-valent manganese ions would disproportionate into bivalent and tetravalent forms in acidic or neutral solutions. This would reduce the stability and recycling of adsorbent materials [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Theoretically, conventional manganese oxides MnO

2·0.5H

2O typically exhibit a lithium adsorption capacity of less than 40 mg/g

1. This is due to their structural instability, which leads to a lower-than-expected lithium capacity. In a complex brine system with high concentrations of sodium, potassium, and magnesium ions coexisting, competitive adsorption reduces lithium selectivity. It is important to note that repeated adsorption-desorption processes can shorten the lifespan of materials.

Metal-organic framework materials (MOFs), such as zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) [

7], when used as coatings or matrices, have been shown to enhance the performance of lithium ion sieves [

8,

9,

10]. The high specific area of MOFs can provide more active sites, thereby enhancing the diffusion and adsorption of lithium ions [

10,

11]. Some MOFs exhibit a strong affinity for lithium ions, and they have been found to adsorb synergistically with lithium ion sieves. The porosity of MOFs can be tailored to exclude large ions, such as sodium and magnesium ions, by leveraging the molecular sieve effect [

9]. Some functional groups on the surface of MOFs have been found to bind lithium ions via ion exchange preferentially [

10]. MOFs’ frameworks have been developed to enhance structural stability, thereby preventing particle disintegration.

ZIF-8 is defined as a subfamily of MOF composed of zinc ions and imidazole organic ligands. The product has a zeolite-like structure and high chemical stability. In the field of lithium adsorption, ZIFs are widely considered for their adjustable pore sizes and surface chemical properties. The combination of ZIF and manganese-based ion sieve has the potential to enhance lithium selectivity and capacity. Fathina et al. [

8] synthesized Li-MnO

2@ZIF-8 via the ultrasonic method, incorporating Li-MnO

2 nanoparticles into the mesoporous structure of ZIF-8, which contains numerous interconnected cavities and channels. They then wrapped the Li-MnO

2@ZIF-8 nanocomposite particles in a PAN polymer matrix due to the strong interactions between the nanocomposite particles. The polymer network significantly improved the efficiency of lithium adsorption. In this paper, H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 lithium ion sieve has been prepared using the hydrothermal method, subsequently mixed with ZIF-8 via supersonic assistance. A study has been conducted on the lithium adsorption property of the porous materials, and the mechanism has been analyzed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Preparation of H1.6Mn1.6O4

1.58 g KMnO

4 and 8.4 g LiOH·H

2O were weighed and combined in the beaker I. The solid mixture was then dissolved in deionized water. The quantity of 6.76 g of MnSO

4·H

2O (AR) was accurately measured and dissolved in beaker II. The first solution was added to the MnSO

4 solution and thoroughly stirred. The final solution was loaded into a high-pressure hydrothermal reactor and pressurized. The process was conducted at 160 °C for 8 hours. The reaction is as follows:

The container was then removed from the reactor, and the liquid was extracted. The residue was then vacuum filtered with deionized water and ethanol on three separate occasions. The final product was placed in the oven at 60 °C to dry for 8 hours. Following this, the powder was ground and placed in a graphite crucible. It was then sintered in a muffle furnace at 450 °C for 6 hours to obtain the ion sieve precursor.

The precursor (0.8 g) was dissolved in 800 mL of 0.5 M hydrochloric acid in a 1000 mL conical flask. The flask was placed in a constant-temperature incubator shaker at 30 °C and 150 rpm for 12 hours.

2.2. The Preparation of ZIF-8@H1.6Mn1.6O4

3.936 g of 2-methyl imidazole(HMIM, AR)and 16 mL of N, N-dimethlformamide (DMF, AR) were mixed and stirred at 21 °C for 10 minutes to form solution A. 3.986 g of Zn(NO3)2 (AR) and N, N- dimethlformamide (DMF, AR) were mixed at 21 °C to form solution B. Solution A and B were added to a beaker and mixed on a the magnetic stirrer at 40 °C for12 hours. The product, a mixture of solution and white precipitate, was placed in a centrifuge tube with a counterweight, then centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 5 minutes. After the centrifugation, the upper layer was removed, and the white residue was dried in the oven.

The steps involved are identical to those outlined above. Solution A and B were mixed, and the precursor (0.246 g) was added, followed by supersonic agitation for 40 minutes to facilitate the growth of ZIF on the surface of the precursor. The beaker was heated using the magnetic stirrer at 40 °C for 12 hours. The solution and precipitate obtained were then subjected to centrifugation, which yielded a dark brown solid. The solid was subsequently dried in an oven.

2.3. Lithium Ion Adsorption Process

The lithium ion sieve (0.1 g) was added to a 250 ml conical flask, and 100 ml of lithium-ion solution at different concentrations and pH values was added. The incubator shaker was set to 30 °C and 150 rpm at different intervals. The concentration of lithium ions in the supernatant was measured, and the lithium ion adsorption capacity of the material was calculated using Equation (2):

where

C0 (mg/L) is the initial mass concentration of lithium ions in the solution;

Ct (mg/L) is the initial mass concentration of lithium ions at time

t;

V (L) is the volume of the solution; and

m(g) is the mass of added material.

2.4. Characterization

The phase composition was analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD, XRD-7000 Shimadzu Corporation, Japan). The concentration of lithium ions in the solution was measured using an Inductively Coupled Plasma Emission Spectrometer (ICP-OES, Plasma 1500, Shanghai Research Institute of Special Steel & NACKS Testing Technology Co., Ltd.), a highly accurate and reliable analytical instrument. The morphology of the materials was observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Apreo 2C), and the semi-quantitative composition and elemental surface distributions were determined using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS, AXIS SUPRA+) was used to analyze the change in the Li 1s and Mn 2p peaks. These peaks are indicative of the lithiation effect and valence change of manganese, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. XRD Patterns of Materials

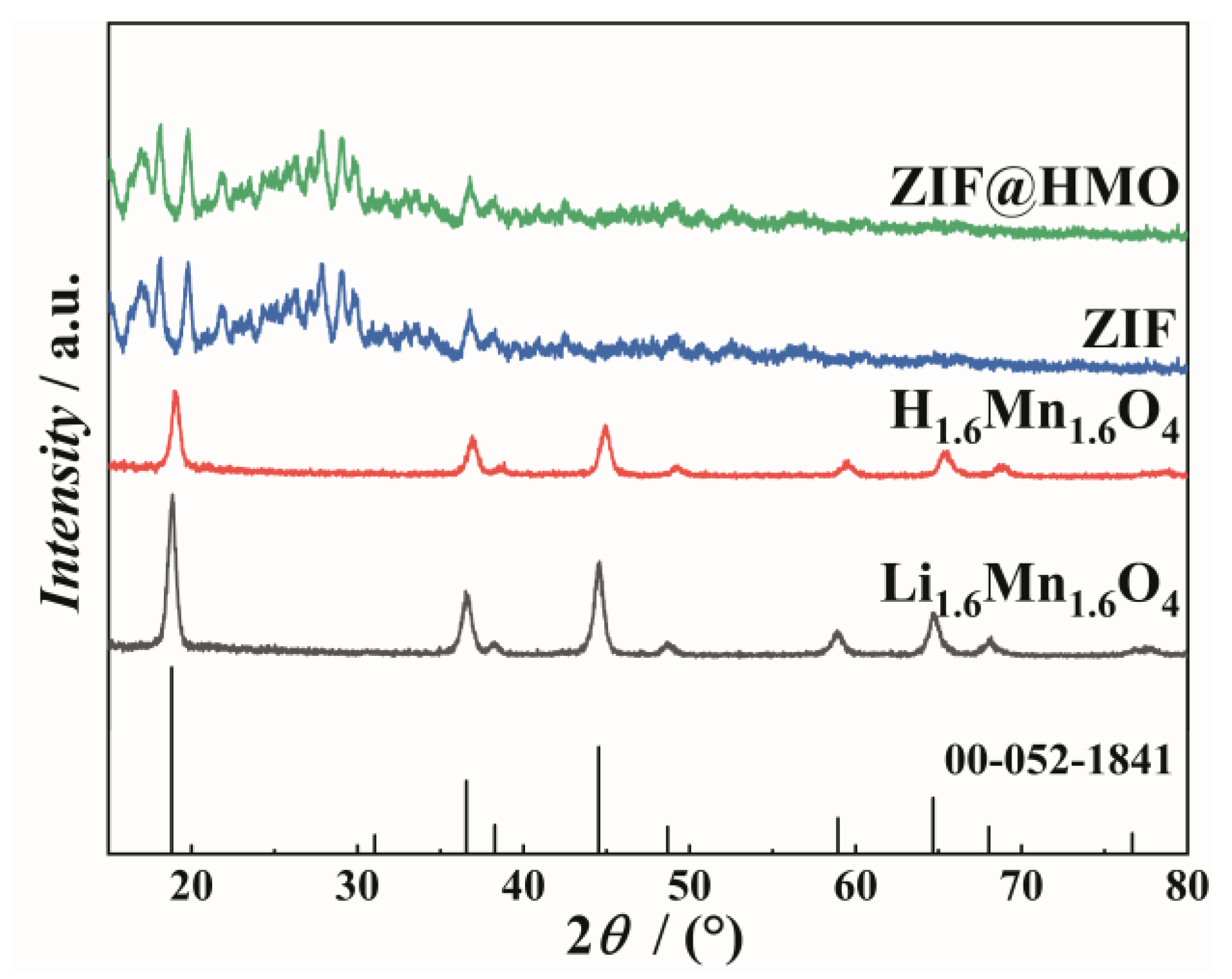

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the XRD patterns of the precursor produced by the hydrothermal method, the lithium ion sieve obtained by hydrochloric acid pickling, and the composite formed via the in-situ solvent thermal growth method are presented.

The peaks of the precursor sample follow the standard peaks of Li

1.6Mn

1.6O

4(PDF No. 00-052-1841 [

1]) at 2 Theta values of 18.6° (111), 36.1° (311), 44.2° (400), 58.7° (511), and 64.5° (440), indicating the sample was pure phase Li

1.6Mn

1.6O

4. The peaks of the pickled phase (H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4) are comparable to those of the precursor (Li

1.6Mn

1.6O

4) phase, suggesting that they belong to the same crystal structure. However, the maximum strength of the (311) crystal face at approximately 36.1 ° is higher due to the orderly occupation of tetrahedral sites by lithium ions. Because of the pickling process, H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 retains the spinel structure, with peaks that shift to the right. This is indicative of the contraction of the crystal lattice upon proton insertion. The composite ZIF-8@H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 patterns show clear peaks indicative of a spinel structure at 36.1° (311) and 44.2° (400), indicating that the ion sieve’s integrity was preserved and undamaged by the coating process. The peaks of H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 appear to shift towards lower angles, a possible consequence of stress at the interface with the ZIF-8 coating. Following the coating of ZIF-8, the half-width height of the peaks of H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 increased, indicating a smaller crystalline size. The (311) facet at the peak of 36.1° is the primary transport route for ions, thereby influencing the adsorption dynamics of lithium ions. The (400) facet at 44.2° is the close-packed plane of the spinel structure and is related to structural stability. The coexistence of ZIF-8 at 17.3 ° and H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 at 36.1 ° indicates a successful reconciliation of the two.

3.2. The Morphology of Ion Sieves

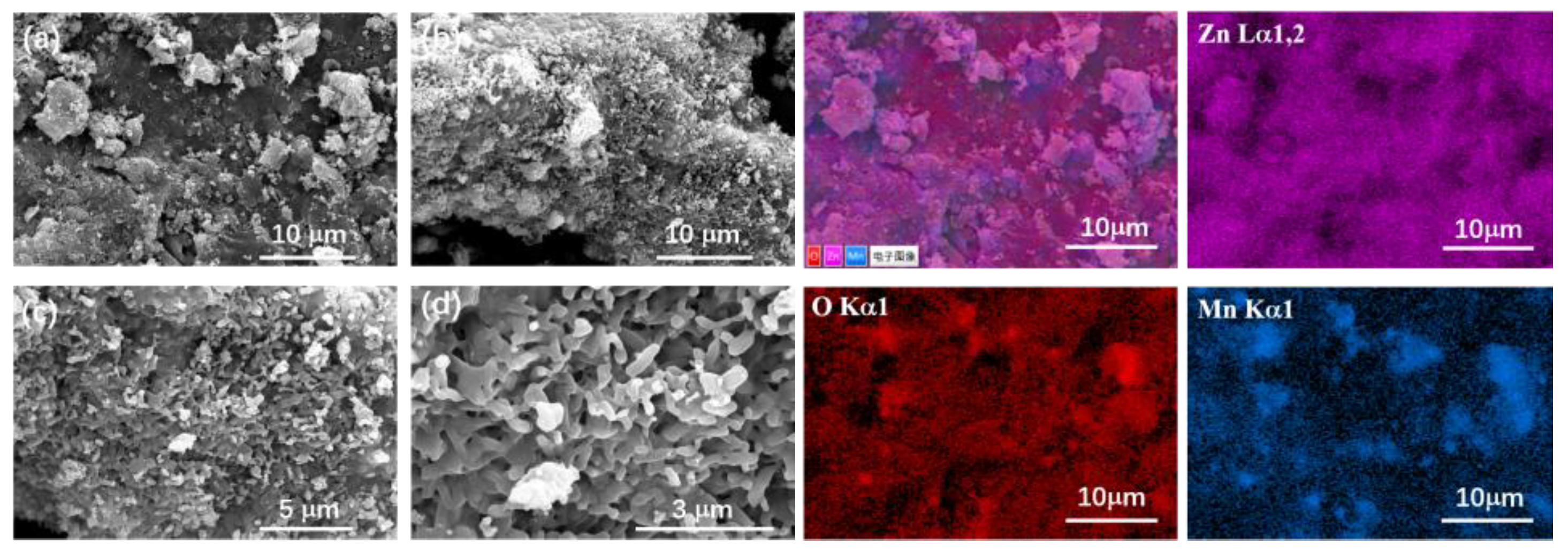

The ZIF@H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 sample was examined using SEM, and a selected area within it was subjected to elemental mapping for Zn, O, and Mn. The resulting images are displayed in

Figure 2 (a ~ d).

As evident from the SEM images at different scales, the sample has a loose, porous structure with uniform, regular morphology. As demonstrated in the right part of

Figure 3, the X-ray energy spectrum analysis confirms the successful dispersion and distribution of different elements in the composite material. By carefully observing the electron microscope images, it can be considered that ZIF materials grow relatively uniformly on the precursor, forming an interlaced state.

3.3. XPS Results Before and After Delithiation of Adsorbent Materials

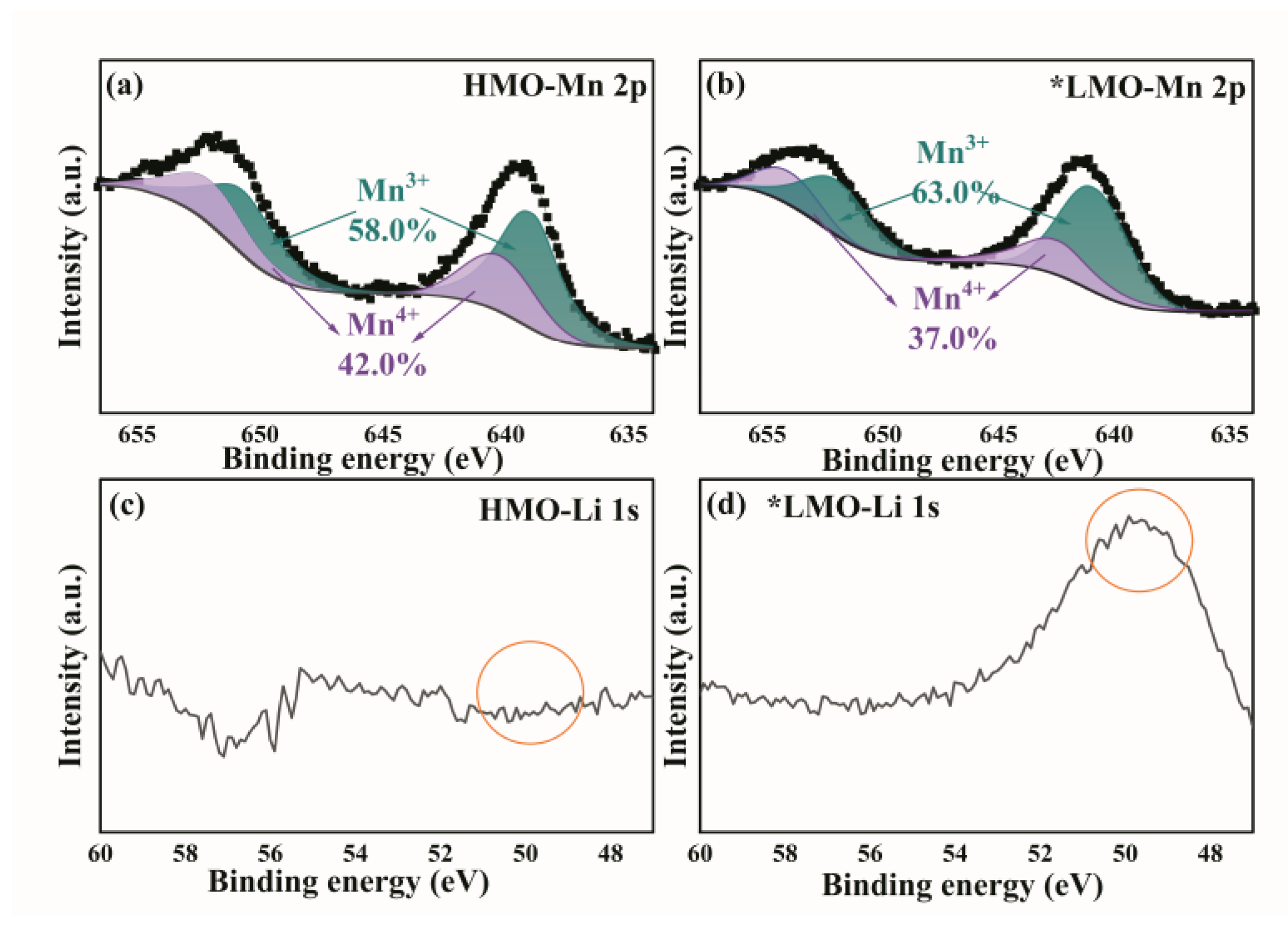

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on two samples of ZIF@ H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 before and after the lithium adsorption experiments, with the Li 1s orbital and Mn 2p orbital selected as the analysis objects.

Figure 3 was obtained.

Based on the comparison of pre- and post-data as well as images, the lithium concentration and content are significantly increased after adsorption, and they are completely adsorbed through chemical adsorption, confirming its high performance in lithium extraction. Before lithium extraction, Mn³⁺ is dominant (641.8 eV), with a small amount of Mn⁴⁺ (643.5 eV), which is consistent with the characteristics of spinel-type lithium manganese oxides [

12]. After lithium extraction, the proportion of Mn⁴⁺ increases, and the peak position shifts toward 643.5 eV. This is due to the oxidation of Mn³⁺ accompanying the insertion/extraction of lithium ions, and Mn²⁺ may be generated (640.5 eV) due to disproportionation caused by the Jahn-Teller effect [

13].

3.4. Adsorption Performance of ZIF-8@H1.6Mn1.6O4

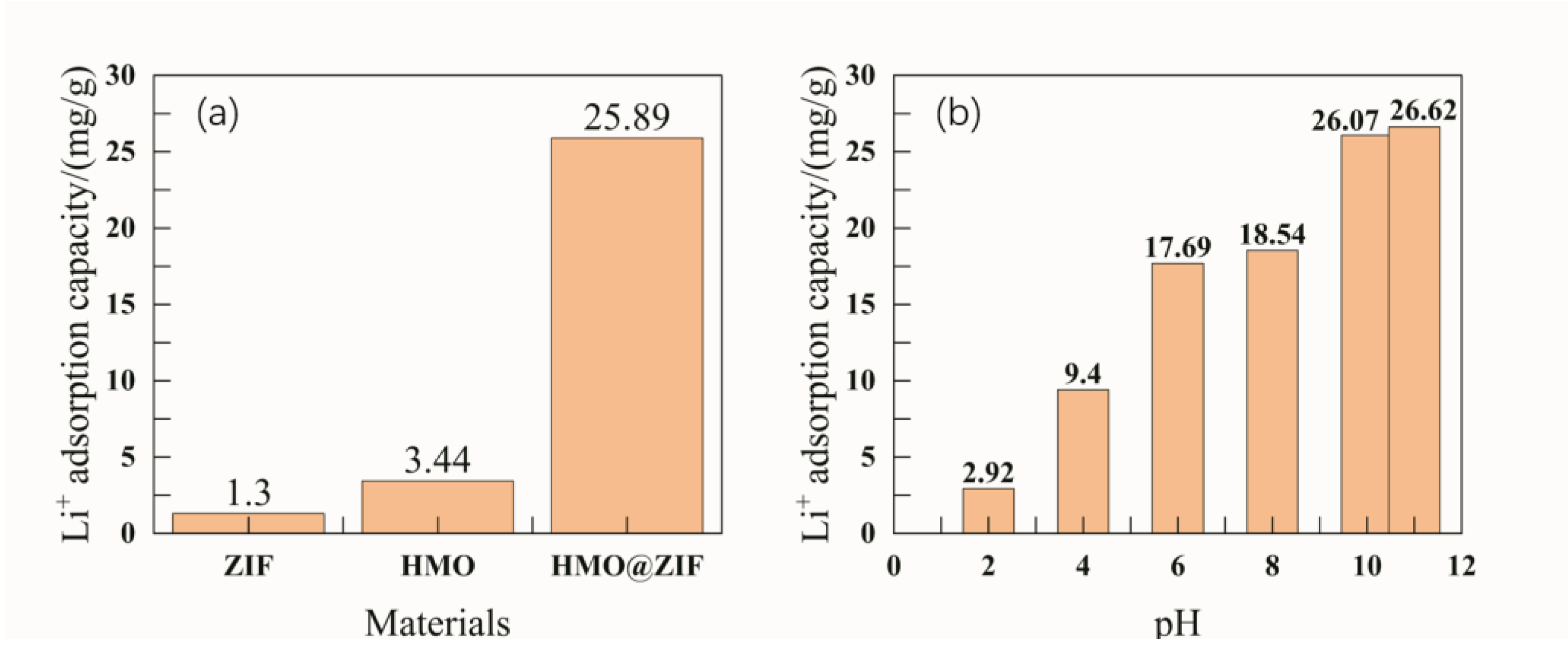

Figure 4 shows the adsorption lithium extraction experimental data of H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4, MOF, and ZIF@ H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4.

It can be clearly seen that under the condition of a lithium ion concentration of 500 mg/L for 24 hours, the lithium extraction capacity of uncoated H1.6Mn1.6O4 is 3.44 mg/g, and the lithium extraction effect of ZIF is 1.3 mg/g. In comparison, the adsorption effect of lithium ions by the ZIF@ H1.6Mn1.6O4 composite material is 25.89 mg/g. This fully demonstrates that the lithium extraction effect of manganese-based lithium ion sieves is significantly improved with ZIF coating.

Different pH levels also affect the adsorption efficiency of lithium ions. In this experiment, under conditions of 30 °C and a concentration of 250 mg/L, lithium ion solutions with pH values of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 11 were subjected to lithium adsorption, and the results are shown in

Figure 5 (b). Experimental results show that under conditions of 250 mg/L concentration and 24 hours of reaction time, the lithium extraction efficiency is 2.92 mg/g when the solution pH is 2, 9.4 mg/g at pH 4, 17.69 mg/g at pH 6, 18.54 mg/g at pH 8, 26.07 mg/g at pH 10, and 26.62 mg/g at pH 11. Therefore, the adsorption-based lithium extraction efficiency of ZIF@ H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 increases with the rise in pH, indicating that the solution pH is a key parameter affecting the interaction between lithium ions and the adsorption surface. At high pH, functional groups undergo deprotonation, forming negatively charged active sites that attract positively charged lithium ions. In acidic conditions, many hydrogen ions cause protonation of the adsorbent’s functional groups and active sites. Additionally, the repulsion between hydrogen ions and lithium ions is enhanced, intensifying the adsorption competition between lithium ions and hydrogen ions at the active sites. Given this, the adsorption effect is better under alkaline conditions.

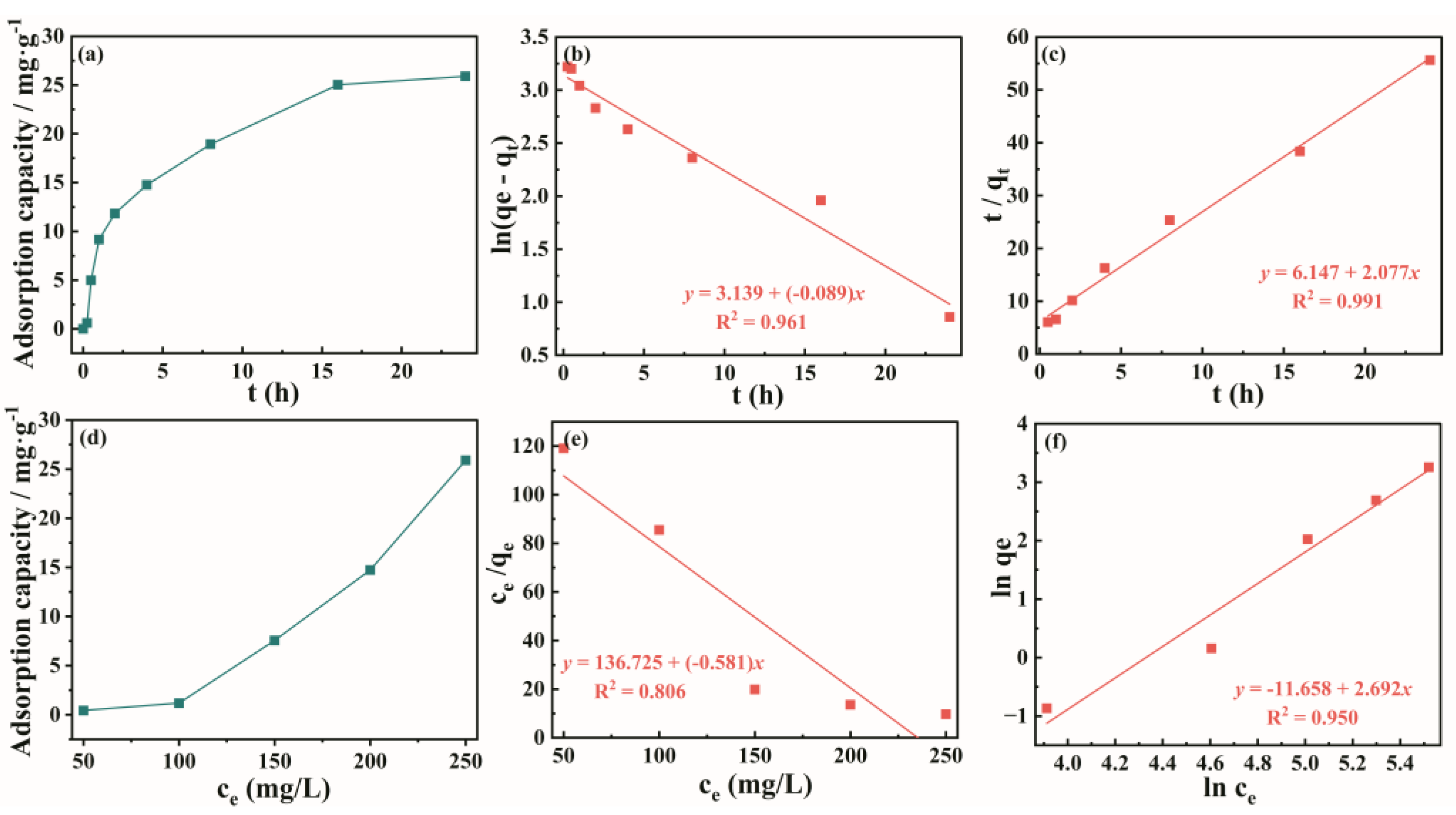

To further investigate the adsorption kinetics of the lithium ion sieve, kinetic model fitting was performed on the lithium ion adsorption time curve of ZIF@ H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 under a concentration of 500 mg/L, as shown in

Figure 5 (a). The data on the lithium extraction effect of ZIF@ H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 over time were organized to obtain

Figure 5 (b). The set of data has been fit with pseudo-first-order kinetics and pseudo-second-order kinetics, respectively, resulting in

Figure 5 (c) and (d). Different lithium ion concentrations have an impact on the lithium ion adsorption effect. Under the conditions of 30 °C and pH 12.18, this experiment was conducted on lithium adsorption from lithium ion solutions with concentrations of 50 mg/L, 100 mg/L, 150 mg/L, and 200 mg/L. The results shown in

Figure 5 (b) can be obtained. The experimental results show that as the lithium ion concentration in the solution gradually increases, the lithium extraction effect gradually improves. With a higher lithium ion concentration, lithium ions have a greater chance of entering the pore window of ZIF@ H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 and combining with vacancies, thereby enhancing the lithium extraction effect. As can be seen from

Figure 5 (c) and (d), the pseudo-second-order kinetic model can better fit the experimental data, with its R² value (0.99) being significantly higher than that of the pseudo-first-order kinetic model (0.85). The maximum adsorption capacity calculated using the pseudo-second-order kinetic model (25.9 mg/g) is also closer to the actual value of 25.89 mg/g. This indicates that the pseudo-second-order kinetic model better describes the transfer process of solid-liquid species during ZIF@HMO adsorption of lithium ions, and that the adsorption of lithium ions by ZIF@H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 is chemical.

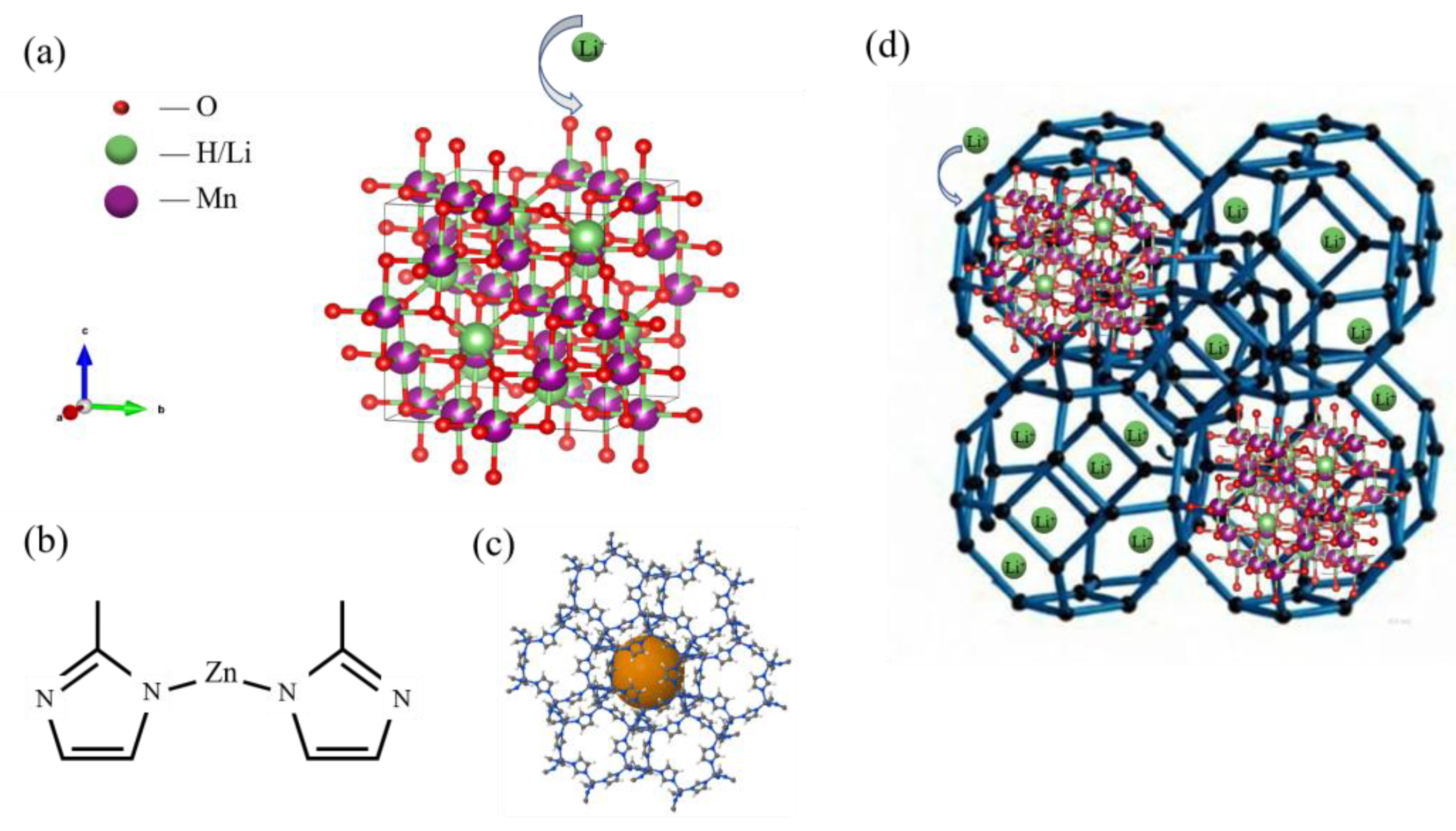

4. Discussion

The lithium selective manganese oxide, H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 (MnO

2‚0.5H

2O) is derived from Li

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 via acid washing. Its ion-exchange capacity was markedly larger than that of the other manganese oxides, because the theoretical exchange capacity reaches 10.5 mmol/g based on the chemical composition [

14]. And the chemical stability is sufficiently high, because it contains only tetravalent manganese, theoretically. According to the results in

Figure 4, H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 has a higher adsorption capacity of lithium compared to ZIF-8. Thus, H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 is the main adsorbent for selective lithium extraction in the coated material ZIF-8@ H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4, primarily achieved through ion exchange between protons and lithium ions (as shown in

Figure 6(a)). Porous crystalline ZIF-8 was formed from the combined network of Zn(C

4H

9N

2)

2 molecules, as shown in

Figure 6(b), prepared by reacting an appropriate hydrated transition metal salt with the ImH ligand in an amide solvent, and then heating the reaction mixture to 85–150 °C. At these temperatures, amines formed through the thermal decomposition of the solvent deprotonate the ImH linker, facilitating framework formation. After the mixture is cooled, crystalline products are usually obtained in moderate to high yields [

7].

The performance optimization of encapsulated lithium-ion sieving materials for lithium extraction from brine requires consideration of three key factors. First, the stability of the material in the liquid phase system; second, precise regulation of pore size can achieve selective transmission of lithium ions while blocking magnesium ions; in addition, ZIF-8 prevents direct contact between H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 and acidic solutions, reducing the possibility of the leaching of manganese ions. It remains relatively stable in the pH range of 2 to 12, protecting the ion sieve from structural degradation under acidic elution conditions. Therefore, the material also exhibits a specific lithium-extraction effect under acidic conditions. Consequently, the lithium extraction mechanism of ZIF@H

1.6Mn

1.6O

4 is a synergistic process of ‘enrichment-exchange’ as

Figure 6(d).

In some circumstances, due to factors such as pH, competitive ligands, and temperature, most coated materials are unstable in aqueous solutions, especially under the high-salinity conditions of salt lake brines, which limits their application for selective lithium ion separation from brines [

8]. However, the manganese-based ion sieves coated with metallic organic frameworks, through exceptional design, can maintain stability in aqueous systems and achieve efficient ion separation. Generally, when the central ion is a high-valence metal ion, strong coordination bonds can be formed with carboxylate-type ligands, thereby enhancing stability [

15]. In addition, the hydrophobicity of the coated materials, and thus their water stability, can be improved by modifying the ligand functional groups or by using mixed metal-organic frameworks [

16]. Ion selectivity in nanochannels requires precise control of surface charge and channel size. To achieve cation selectivity, the nanochannel surface must carry fixed negative charges, and the channel must be narrowed so that the influence of these charges extends throughout the channel. This influence is set by the Debye length, which defines the thickness of the electrical double layer (EDL) at charged interfaces and depends on solution ionic strength (typically ~1–100 nm; ~1 nm for 0.1 M 1:1 electrolyte) [

17]. The EDL consists of a Stern layer of immobilized counterions adjacent to the negatively charged wall and a diffuse layer where counterions, under weaker electrostatic attraction, remain mobile [

18]. Hence, pore-size regulation of coated materials is a key design parameter for efficient lithium-ion separation. By precisely controlling the pore size, a size-exclusion mechanism can be established, allowing only lithium ions to pass while blocking magnesium ions. The surface potential characteristics of coated lithium ion adsorbents have a decisive influence on their selective adsorption behavior. When the material’s surface potential is positive, it electrostatically repels lithium ions, thereby reducing adsorption capacity. Conversely, when the potential is negative, it electrostatically attracts lithium ions, significantly increasing lithium ion adsorption capacity. In this respect, a more in-depth investigation is necessary.

5. Conclusions

A ZIF-8–coated manganese-based lithium ion sieve (ZIF-8@H1.6Mn1.6O4) was synthesized to enhance lithium extraction from aqueous solutions. The spinel sieve structure of the precursor lithium manganese oxide was maintained while ZIF-8 formed a uniform porous coating with well-dispersed elements. The composite reached high lithium ion adsorption capacity, greatly outperforming the uncoated sieve and ZIF-8 alone, with capacity increasing at higher pH and Li+ concentration. Adsorption followed a pseudo-second-order kinetic model and was dominated by chemisorption. ZIF-8 provided selective channels and structural protection for H1.6Mn1.6O4, enabling a synergistic “enrichment–exchange” process. Controlling pore size, surface charge, and structural stability in saline media is key to achieving Li+/Mg2+ selectivity and long-term durability of MOF coated lithium ion sieves.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used Grammarly for fluency. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HMO |

Protoned Manganese Oxide |

| LIS |

Lithium Ion Sieve |

| LMO |

Lithium Manganese Oxide |

| MOFs |

Metal-organic framework materials |

| ZIFs |

Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks |

References

- Chitrakar, R.; Kanoh, H.; Miyai, Y.; Ooi, K. A New Type of Manganese Oxide (MnO2·0.5H2O) Derived from Li1.6Mn1.6O4 and Its Lithium Ion-Sieve Properties. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 3151–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitrakar, R.; Kanoh, H.; Miyai, Y.; Ooi, K. Recovery of Lithium from Seawater Using Manganese Oxide Adsorbent (H1.6Mn1.6O4) Derived from Li1.6Mn1.6O4. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2001, 40, 2054–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Hou, X.; Sun, Z.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, J. Lithium-Desorption Mechanism in LiMn2O4, Li1.33Mn1.67O4, and Li1.6Mn1.6O4 According to Precisely Controlled Acid Treatment and Density Functional Theory Calculations. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 20878–20890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabolla Rodríguez, R.; Della Santina Mohallem, N.; Avila Santos, M.; Sena Costa, D. A.; Andrey Montoro, L.; Mosqueda Laffita, Y.; Tavera Carrasco, L. A.; Perez-Cappe, E. L. Unveiling the Role of Mn-Interstitial Defect and Particle Size on the Jahn-Teller Distortion of the LiMn2O4 Cathode Material. J. Power Sources 2021, 490, 229519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, P.; Cao, Y.-L.; Xie, Y.-L. Co Ion-Modified Li1.6Mn1.6O4 with Enhanced Li+ Adsorption Performance and Cyclic Stability. J. Mater. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Kim, T.-J.; Kim, Y. J.; Park, B. Complete Blocking of Mn3+ Ion Dissolution from a LiMn2O4 Spinel Intercalation Compound by Co3O4 Coating. Chem. Commun. 2001, No. 12, 1074–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, A.; Doonan, C. J.; Uribe-Romo, F. J.; Knobler, C. B.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O. M. Synthesis, Structure, and Carbon Dioxide Capture Properties of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathinia, S.; Mehdi Salarirad, M. Superior Selective Adsorption of Lithium Using Hierarchical Granular Nanostructures (PAN@LIS-MnO2@ZIF-8) from Its Low-Grade Aqueous Sources. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Mu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y. PVC-Based Hybrid Membranes Containing Metal-Organic Frameworks for Li+/Mg2+ Separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 596, 117724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ying, Y.; Mao, Y.; Peng, X.; Chen, B. Polystyrene Sulfonate Threaded through a Metal-Organic Framework Membrane for Fast and Selective Lithium-Ion Separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2016, 55, 15120–15124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, R.; Zhang, H.; Wei, J.; Kim, S.; Wan, L.; Nguyen, N. S.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Simon, G. P.; Wang, H. Thermoresponsive Amphoteric Metal–Organic Frameworks for Efficient and Reversible Adsorption of Multiple Salts from Water. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1802767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thackeray, M. M. Manganese Oxides for Lithium Batteries. Prog. Solid State Chem. 1997, 25, 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummow, R. J.; de Kock, A.; Thackeray, M. M. Improved Capacity Retention in Rechargeable 4 V Lithium/Lithium-Manganese Oxide (Spinel) Cells. Solid State Ion. 1994, 69, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitrakar, R.; Kanoh, H.; Miyai, Y.; Ooi, K. Recovery of Lithium from Seawater Using Manganese Oxide Adsorbent (H1.6Mn1.6O4) Derived from Li1.6 Mn1.6 O4. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2001, 40, 2054–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Keser Demir, N.; Chen, J. P.; Li, K. Applications of Water Stable Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5107–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, M.; Guo, Y.; Mamrol, N.; Yang, X.; Gao, C.; Van Der Bruggen, B. Metal-Organic Framework Based Membranes for Selective Separation of Target Ions. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 634, 119407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjou, A.; Asadnia, M.; Hosseini, E.; Habibnejad Korayem, A.; Chen, V. Design Principles of Ion Selective Nanostructured Membranes for the Extraction of Lithium Ions. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daiguji, H. Ion Transport in Nanofluidic Channels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).