Submitted:

05 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Materials

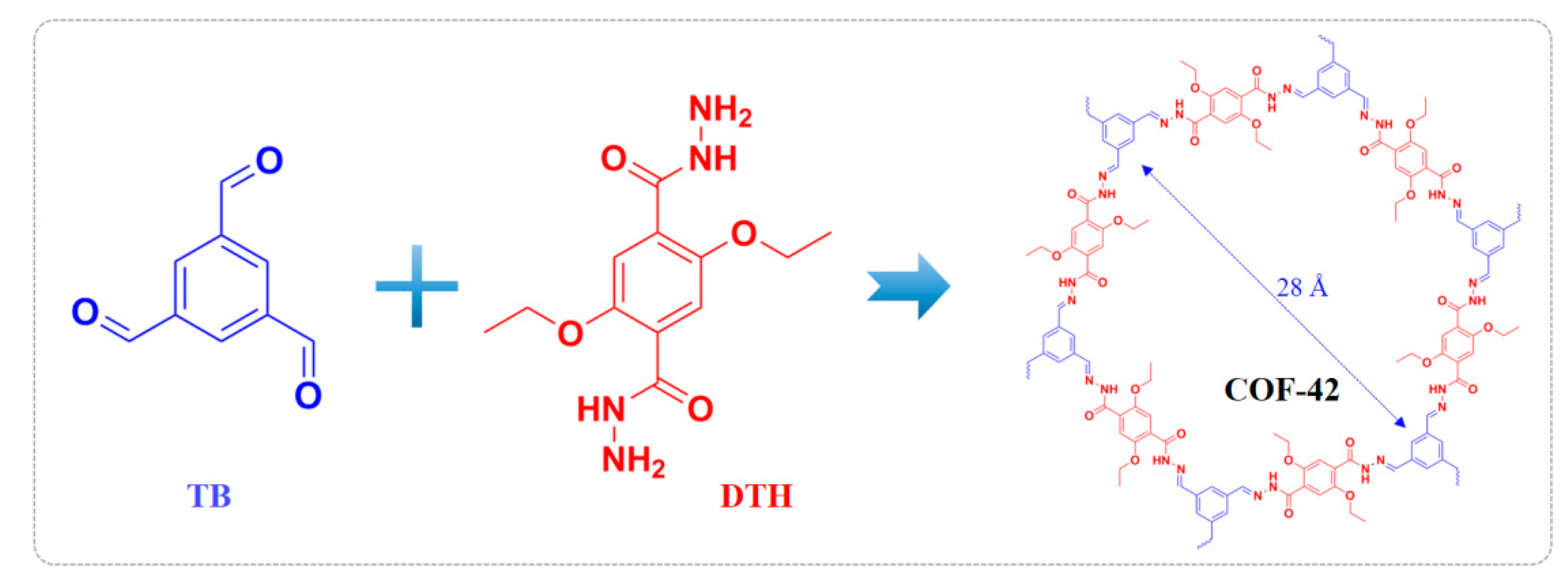

2.2. Preparation of COF-42

2.3. Adsorption Performance of COF-42 Towards Pd

2.4. Characterizations

2.5. Calculations

3. Result and Discussion

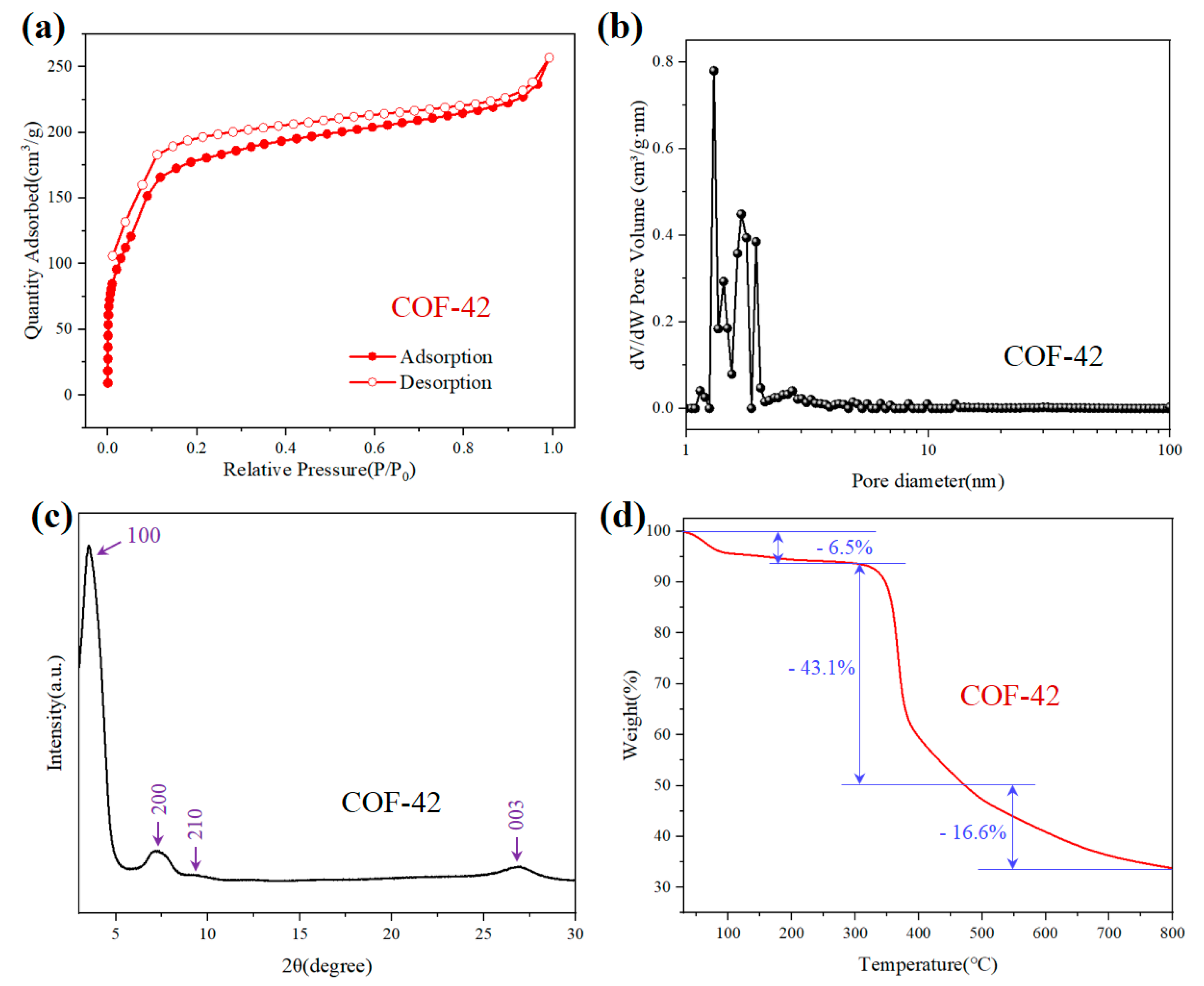

3.1. The Characterization of COF-42

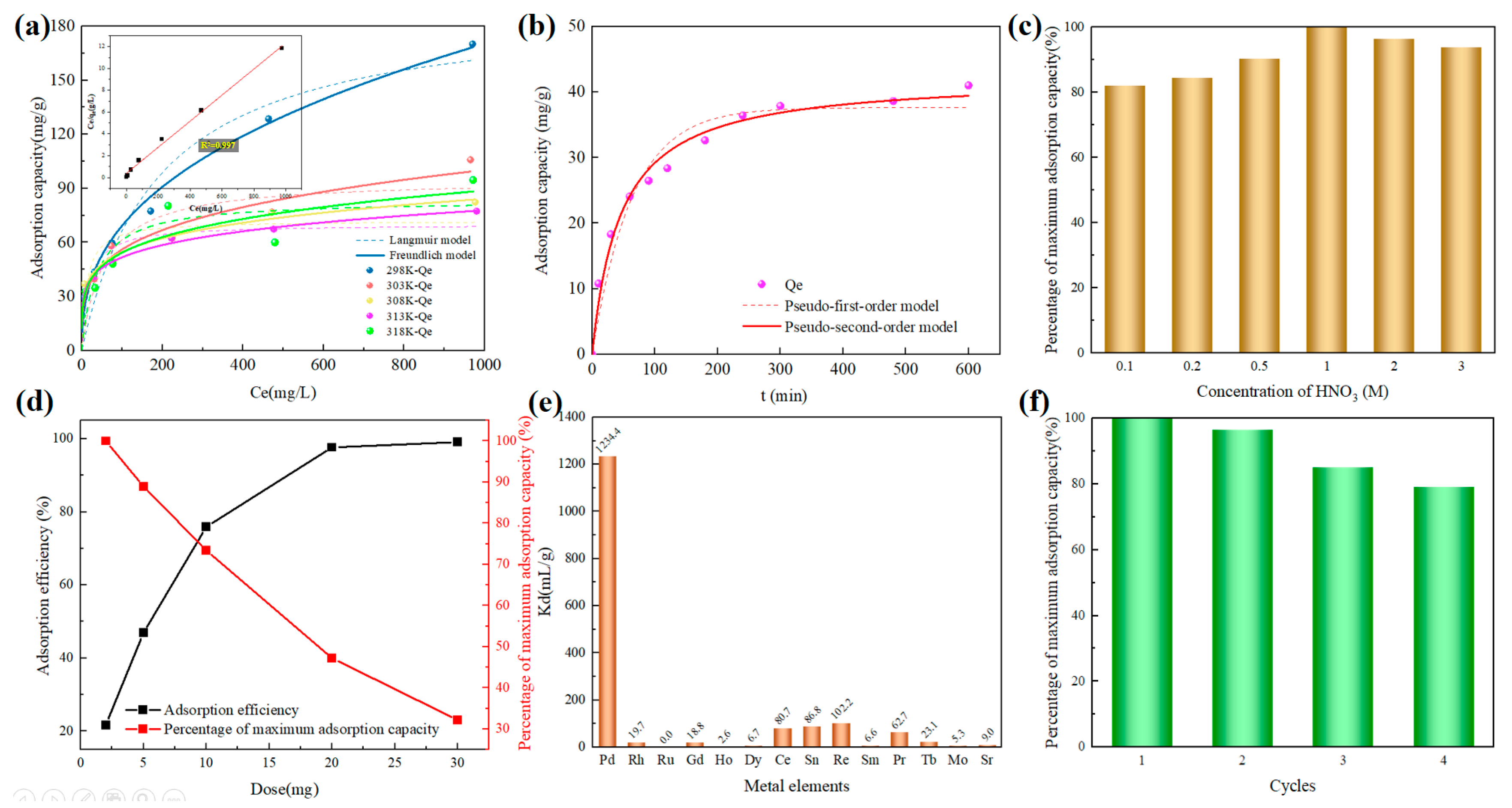

3.2. The Sorption Performance of COF-42 Towards Pd(II)

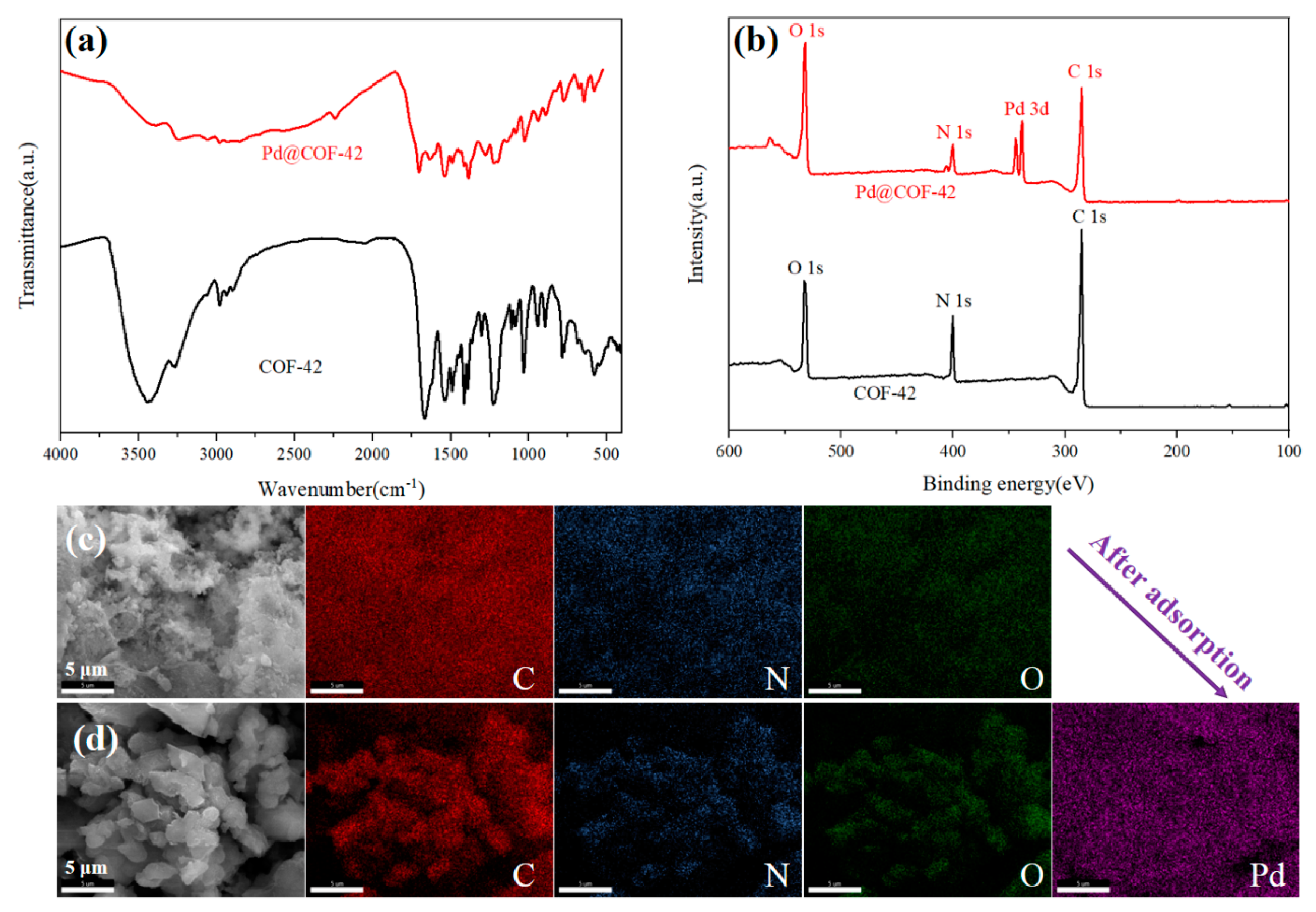

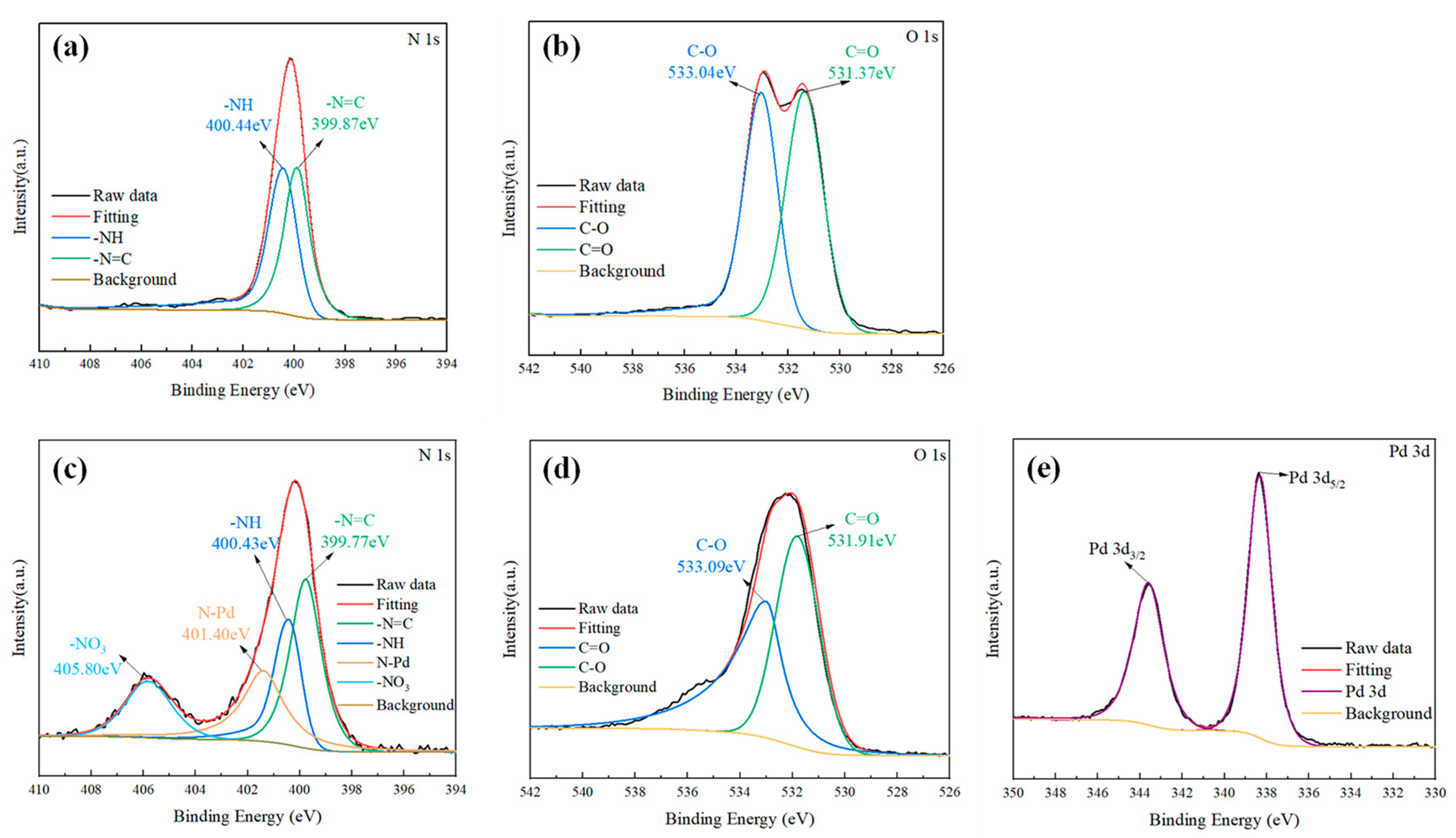

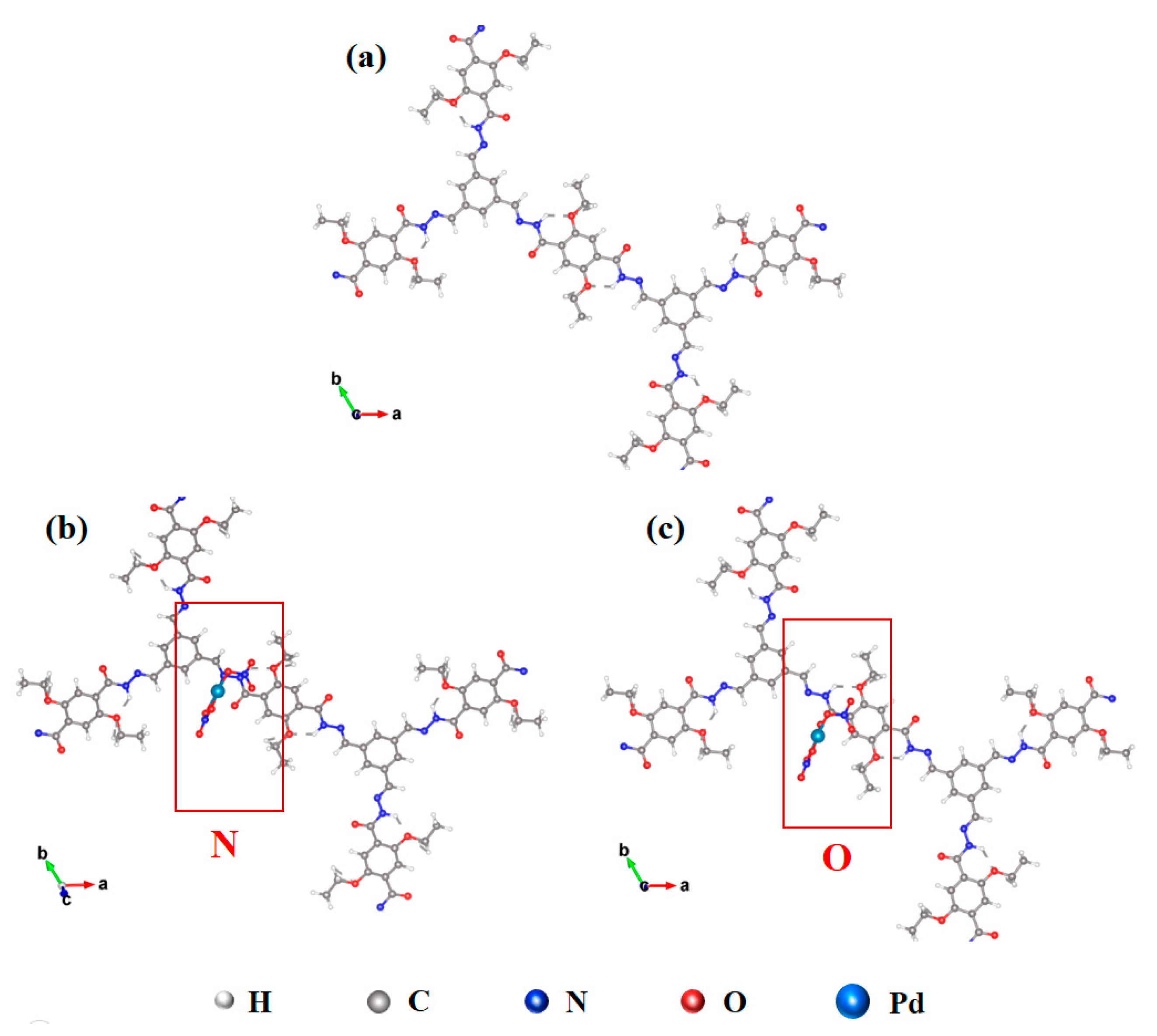

3.3. The Sorption Mechanism of COF-42

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Järvine, A.K.; Murchison, A.G.; Keech, P.G.; et al. A probabilistic model for estimating the life expectancy of used nuclear fuel containers in a canadian geological repository: effects of latent defects and repository temperature. Nucl Technol 2020, 206, 1036–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, J.; Ling, K.; Han, L.; Liu, L. Rapid vitrification of simulated HLLW by ultra-high power laser. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Yakoumis, I.; Panou, M.; Moschovi, A.M.; Panias, D. Recovery of platinum group metals from spent automotive catalysts: A review. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2021, 3, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Peng, Z.; Tian, R.; Ye, L.; Zhang, J.; Rao, M.; Li, G. Platinum-group metals: Demand, supply, applications and their recycling from spent automotive catalysts. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 110237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.; Al-Sheeha, H.; Navvamani, R.; Kothari, R.; Marafi, M.; Rana, M.S. Recycling of platinum group metals from exhausted petroleum and automobile catalysts using bioleaching approach: a critical review on potential, challenges, and outlook. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology 2022, 21, 1035–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Ghahreman, A. Platinum group metals recycling from spent automotive catalysts: metallurgical extraction and recovery technologies. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 311, 123357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Ding, Y.; Wen, Q.; Liu, B.; Zhang, S. Separation and purification of platinum group metals from aqueous solution: Recent developments and industrial applications. Resources Conservation and Recycling 2021, 167, 105417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Zhai, L.; Xu, H.; Jiang, D. Stable covalent organic frameworks for exceptional mercury removal from aqueous solutions. J Am Chem Soc 2017, 139, 2428–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro Pellenz, Carlos Rafael Silva de Oliveira, Afonso Henrique da Silva Júnior, Layrton José Souza da Silva, Luciano da Silva, Antônio Augusto Ulson de Souza, Selene Maria de Arruda Guelli Ulson de Souza, Fernando Henrique Borba, Adriano da Silva. A comprehensive guide for characterization of adsorbent materials. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 305, 122435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhou, C.; Fang, H.; Zhu, W.; Shi, J.; Liu, G. Synthesis of ordered mesoporous silica from biomass ash and its application in CO2 adsorption. Environmental Research 2023, 231, 116070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Joshi, S.; Bayram, G.M.U.; Khati, P.; Simsek, H. Developments and application of chitosan-based adsorbents for wastewater treatments. Environmental Research 2023, 226, 115530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendy, E.A.; Oyekunle, D.T.; Ifthikar, J.; Jawad, A.; Chen, Z. A review on the adsorption mechanism of different organic contaminants by covalent organic framework (COF) from the aquatic environment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 32566–32593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. S. Diercks and O. M. Yaghi, Science, 2017, 355, 923.

- Ding, S.-Y.; Cui, X.-H.; Feng, J.; Lu, G.; Wang, W. Facile synthesis of –CQN– linked covalent organic frameworks under ambient conditions. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 11956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Geng, K.; Liu, R.; Tan, K.T.; Gong, Y.; Li, Z.; Tao, S.; Jiang, Q.; Jiang, D. Covalent Organic Frameworks: Chemical Approaches to Designer Structures and Built-In Functions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5050–5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Chen, F.; Fang, Q.; Qiu, S. Design and Applications of Three Dimensional Covalent Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 1357–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.M.; Parent, L.R.; Flanders, N.C.; Bisbey, R.P.; Vitaku, E.; Kirschner, M.S.; Schaller, R.D.; Chen, L.X.; Gianneschi, N.C.; Dichtel, W.R. Seeded growth of single-crystal two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Science 2018, 361, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. Liao, H. Ding, B. Li, X. Ai and C. Wang, J. Mater. Chem. A, 2014, 2, 8854.

- Zhang, L.; Yi, L.; Sun, Z.-J.; Deng, H. Covalent organic frameworks for optical applications. Aggregate 2021, 2, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Guo, J.; Feng, X.; Honsho, Y.; Guo, J.; Seki, S.; Maitarad, P.; Saeki, A.; Nagase, S.; Jiang, D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 1289–1293.

- S.-Y. Ding, M. Dong, Y.-W. Wang, Y.-T. Chen, H.-Z. Wang, C.-Y. Su and W. Wang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 3031.

- Zanganeh, A.R. COF-42 as sensory material for voltammetric determination of Cu(II) ion: optimizing experimental condition via central composite design. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry 2022, 53, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Aguila, B.; Perman, J.; Nguyen, N.; Ma, S. Flexibility Matters: Cooperative Active Sites in Covalent Organic Framework and Threaded Ionic Polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15790–15796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q. Fang, J. Wang, S. Gu, R. B. Kaspar, Z. Zhuang, J. Zheng, H. Guo, S. Qiu and Y. Yan, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8352.

- Mitra, S.; Sasmal, H. S.; Kundu, T.; Kandambeth, S.; Illath, K.; Diaz Diaz, D.; Banerjee, R. Targeted Drug Delivery in Covalent Organic Nanosheets (CONs) via Sequential Postsynthetic Modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 4513–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayum M, A.; Vijayakumar, V.; Karak, S.; Kandambeth, S.; Bhadra, M.; Suresh, K.; Acharambath, N.; Kurungot, S.; Banerjee, R. Convergent Covalent Organic Framework Thin Sheets as Flexible Supercapacitor Electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 28139–28146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doonan, C. J.; Tranchemontagne, D. J.; Glover, T. G.; Hunt, J. R.; Yaghi, O. M. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 235–238.

- M. G. Rabbani, A. K. Sekizkardes, Z. Kahveci, T. E. Reich, R. Ding and H. M. El-Kaderi, Chem.—Eur. J. 2013, 19, 3324.

- Wang, Z.; Yu, Q.; Huang, Y.; An, H.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, X.; Shi, X.; Liang, J.; Pan, F.; Cheng, P.; Chen, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Z. PolyCOFs: A New Class of Freestanding Responsive Covalent Organic Framework Membranes with High Mechanical Performance. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 1352–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmerhi, N.; Kumar, S.; Jaoude, M.A.; Shetty, D. Covalent Organic Framework-derived Composite Membranes for Water Treatment. Chem Asian J. 2024, 19, e202300944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, T.F.; Serra, M.E.S.; Murtinho, D.; Valente, A.J.M.; Naushad, M. Covalent Organic Frameworks: Synthesis, Properties and Applications—An Overview. Polymers 2021, 13, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Xue, H. Guo, T. Wang, L. Gong, Y. Wang, J. Ai, D. Huang, H. Chen and W. Yang, Anal. Methods, 2017, 9, 3737–3750.

- Zhou, Z.; Zhong, W.; Cui, K.; Zhuang, Z.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Bi, J.; Yu, Y. A covalent organic framework bearing thioether pendant arms for selective detection and recovery of Au from ultra-low concentration aqueous solution. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 9977–9980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, Z.; Karim, A.; Karam, A.; Khalloufi, S. Adsorption of Heavy Metals: Mechanisms, Kinetics, and Applications of Various Adsorbents in Wastewater Remediation—A Review. Waste 2023, 1, 775–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feia, Y.; Hu, Y.H. Design, synthesis, and performance of adsorbents for heavy metal removal from wastewater: a review. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 1047–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Romo, F.J.; Doonan, C.J.; Furukawa, H.; Oisaki, K.; Yaghi, O.M. Crystalline Covalent Organic Frameworks with Hydrazone Linkages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11478–11481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of Ab-Initio Total Energy Calculations for Metals and Semiconductors Using a Plane-Wave Basis Set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996, 6, 15–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From Ultrasoft Pseudopotentials to the Projector Augmented-Wave Method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104.

- Evans, A.M.; Ryder, M.R.; Ji, W.; Strauss, M.J.; Corcos, A.R.; Vitaku, E.; Flanders, N.C.; Bisbey, R.P.; Dichtel, W.R. Trends in the thermal stability of two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Faraday Discuss. 2021, 225, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Adsorption isotherm models: Classification, physical meaning, application and solving method. Chemosphere 2020, 258, 127279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Adsorption kinetic models: Physical meanings, applications, and solving methods. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 390, 122156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Romo, F.J.; Hunt, J.R.; Furukawa, H.; Klöck, C.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4570–4571.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).