Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

15 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Cadotte, M.W.; Carscadden, K.A.; Mirotchnick, N. Beyond Species: Functional Diversity and the Maintenance of Ecological Processes and Services. Journal of Applied Ecology 2011, 48, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, A.M.; Chavez, E.; Caicedo, C.; Tinoco, L.; Pulleman, M. Biological Soil Health Indicators Are Sensitive to Shade Tree Management in a Young Cacao (Theobroma Cacao L.) Production System. Geoderma Regional 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres; Torres, J.J.; Mena-Mosquera, V.E.; Rueda-Sánchez, M.N. Influencia de La Altitud Sobre La Composición Florística, Estructura y Carbono de Bosques Del Chocó. UNED Research Journal 2021, 14, e3746–e3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, M.O.V.; Montero, K.E.V. Tipificación de Los Sistemas de Cultivo de Café, Cacao y Ganadero, En La Amazonía Ecuatoriana. Revista Alfa 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyutaxi, F.M.A.; Guambi, L.D.; Corral, R.; Castillo, H.E.G.; Medina, Segundo Alfonso Vasco; Medina, S.A.V.; Motato, N.; Larrea, G.R.S.; L.Z., A.; T.A., Z.; et al. Variedades Mejoradas de Café Arábigo Una Contribución Para El Desarrollo de La Caficultura En El Ecuador; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, O.; Maldonado, J.; Montaño, T.; Caraballo, M.Á. Estabilidad Vertical de La Atmósfera En Las Provincias de Loja y Zamora Chinchipe, Ecuador. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, C.A.; Pritts, A.A.; Zwetsloot, M.J.; Jansen, K.; Pulleman, M.M.; Armbrecht, I.; Avelino, J.; Barrera, J.F.; Bunn, C.; García, J.H.; et al. Transformation of Coffee-Growing Landscapes across Latin America. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.C.; Burgos, E.R.; Bautista, E.H.D. Efecto de Las Condiciones de Cultivo, Las Características Químicas Del Suelo y El Manejo de Grano En Los Atributos Sensoriales de Café (Coffea Arabica L.) En Taza. Acta Agronómica 2015, 64, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, S. Nutrición Del Café. Consideraciones Para El Manejo de La Fertilidad Del Suelo. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guambi, L.A.D.; Murillo, R.M.A.; Alonso, P.C.P. La Competitividad de Los Cafés Arábigos de Especialidades En Los Concursos “Taza Dorada” En Ecuador. Journal of Agricultural Sciences Resarch 2022, 2, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deCastro-Arrazola, I.; Andrew, N.R.; Berg, M.P.; Curtsdotter, A.; Lumaret, J.-P.; Menéndez, R.; Moretti, M.; Nervo, B.; Nichols, E.S.; Sánchez-Piñero, F.; et al. A Trait-based Framework for Dung Beetle Functional Ecology. Journal of Animal Ecology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfiffner, L.; Balmer, O. La Agriculture Ecológica Fomenta La Biodiversidad; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Newbold, T.; Hudson, L.N.; Hill, S.L.L.; Contu, S.; Lysenko, I.; Senior, R.A.; Börger, L.; Bennett, D.J.; Choimes, A.; Collen, B.; et al. Global Effects of Land Use on Local Terrestrial Biodiversity. Nature 2015, 520, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, R.F.; Korasaki, V.; Andresen, E.; Louzada, J. Dung Beetle Community and Functions along a Habitat-Disturbance Gradient in the Amazon: A Rapid Assessment of Ecological Functions Associated to Biodiversity. PLOS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, J.; Hortal, J.; DeCastro-Arrazola, I.; Alves-Martins, F.; Ortega, J.; Bini, L.; Andrew, N.; Arellano, L.; Beynon, S.; Davis, A.; et al. Dung Removal Increases under Higher Dung Beetle Functional Diversity Regardless of Grazing Intensification. Nature communications 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, E.M.; Riutta, T.; Roslin, T.; Tuomisto, H. The Role of Dung Beetles in Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Cattle Farming. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 18140–18140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccini, I.; Arnieri, F.; Caprio, E.; Nervo, B.; Pelissetti, S.; Palestrini, C.; Roslin, T.; Rolando, A. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Dung Pats Vary with Dung Beetle Species and with Assemblage Composition. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriuzzi, W.S.; Wall, D.H. Soil Biological Responses to, and Feedbacks on, Trophic Rewilding. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2018, 373, 20170448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaguana, C.; Lozano Deicy; Aguirre, Z. Flora y Endemismo Del Bosque Humedo Tropical de La Quinta El Padmi, Zamora Chinchipe; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Loayza, V.E.; Rojas, D.; Salas Tenesaca, E.E.; Samaniego Namicela, A. Fortalecimiento Organizacional de Asociaciones de Productores de Café En Las Provincias de Loja y Zamora Chinchipe, Ecuador. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Dávila, A.J.; Escobar-Ramírez, S.; Armbrecht, I. Nesting of Arboreal Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Artificial Substrates in Coffee Plantations in the Colombian Andes. Uniciencia 2021, 35, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.A.; Barlow; França, J.; Filipe; Berenguer, E.; Solar, R.R.C.; Louzada, J.; Leitão, R.P.; Maia, L.F.; Oliveira, V.H.F.; Braga, R.F.; et al. Functional Redundancy of Amazonian Dung Beetles Confers Community-Level Resistance to Primary Forest Disturbance. Biotropica 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Aguilar, E.F.; Arriaga-Jiménez, A.; Correa, C.M.A.; da Silva, P.G.; Korasaki, V.; López-Bedoya, P.A.; Hernández, M.I.M.; Pablo-Cea, J.D.; Salomão, R.P.; Valencia, G.; et al. Toward a Standardized Methodology for Sampling Dung Beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae) in the Neotropics: A Critical Review. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, W.; Marín-Armijos, D.; Asenjo, A.; Vaz-de-Mello, F.Z. Scarabaeinae Dung Beetles from Ecuador: A Catalog, Nomenclatural Acts, and Distribution Records. ZooKeys 2019, 826, 1–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, C.T.; Santini, L.; Spake, R.; Bowler, D.E. Population Abundance Estimates in Conservation and Biodiversity Research. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clusella-Trullas, S.; Nielsen, M.E. The Evolution of Insect Body Coloration under Changing Climates. Current opinion in insect science 2020, 41, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, P.G.D. Annotated Checklist of Aphodiinae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) from Rio Grande Do Sul and Santa Catarina, Brazil. EntomoBrasilis 2015, 8, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Gotelli, N.J.; Hsieh, T.C.; Sander, E.L.; Ma, K.H.; Colwell, R.K.; Ellison, A.M. Rarefaction and Extrapolation with Hill Numbers: A Framework for Sampling and Estimation in Species Diversity Studies. Ecological Monographs 2014, 84, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.5-6 2019. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

- Whittaker, R.J.; Willis, K.J.; Field, R. Scale and Species Richness: Towards a General, Hierarchical Theory of Species Diversity. Journal of Biogeography 2001, 28, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R-Core-Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. In R: A language and environment for statistical computing.; 2019.

- Domínguez, D.; Marín-Armijos, D.; Ruiz, C. Structure of Dung Beetle Communities in an Altitudinal Gradient of Neotropical Dry Forest. Neotrop Entomol 2015, 44, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Paladines, V.; Fries, A.; Muñoz, A.; Castillo, E.; García-Ruiz, R.; Marín-Armijos, D. Effects of Land-Use Change on the Community Structure of the Dung Beetle (Scarabaeinae) in an Altered Ecosystem in Southern Ecuador. Insects 2021, 12, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Bautista, J.S.; Parada-Alfonso, J.A.; Carvajal-Cogollo, J.E. Dung Beetles (Scarabaeidae, Scarabaeinae) of the Foothills–Andean Forest Strip of Villavicencio, Colombia. CheckList 2020, 16, 821–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, V.R.; Noriega, J.A. Diversity of the Dung Beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae) in an Altitudinal Gradient in the East Slope of Los Andes, Napo Province, Ecuador. Neotropical Biodiversity 2018, 4, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Clavijo, A.; Armbrecht, I. Soil Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and Ground Beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in a Coffee Agroforestry Landscape during a Severe-Drought Period. Agroforest Syst 2019, 93, 1781–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, E.; Larsen, T.H.; Spector, S.; Davis, A.L.V.; Escobar, F.; Favila, M.E.; Vulinec, K. Global Dung Beetle Response to Tropical Forest Modification and Fragmentation: A Quantitative Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Biological Conservation 2007, 137, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, E.C.; Maldaner, M.; Costa-Silva, V.; Sehn, H.; Franquini, C.; Campos, V.; Seba, V.; Maia, L.; Vaz-de-Mello, F.; França, F. Dung Beetles from Two Sustainable-Use Protected Forests in the Brazilian Amazon. BDJ 2023, 11, e96101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratoni, B.; Ahuatzin, D.; Corro, E.J.; Salomão, R.P.; Escobar, F.; López-Acosta, J.C.; Dáttilo, W. Landscape Composition Shapes Biomass, Taxonomic and Functional Diversity of Dung Beetles within Human-Modified Tropical Rainforests. J Insect Conserv 2023, 27, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halffter, G.; Arellano, L. Response of Dung Beetle Diversity to Human-Induced Changes in a Tropical Landscape1. Biotropica 2002, 34, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, F.G. Invasion and Retreat: Shifting Assemblages of Dung Beetles amidst Changing Agricultural Landscapes in Central Peru. Biodivers Conserv 2009, 18, 3519–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, E.; Spector, S.; Louzada, J.; Larsen, T.; Amezquita, S.; Favila, M.E. Ecological Functions and Ecosystem Services Provided by Scarabaeinae Dung Beetles. Biological Conservation 2008, 141, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, L.L.; Farley, K.A. Does Plantation Forestry Restore Biodiversity or Create Green Deserts? A Synthesis of the Effects of Land-Use Transitions on Plant Species Richness. Biodivers Conserv 2010, 19, 3893–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, T.H.; Lopera, A.; Forsyth, A. Understanding Trait-Dependent Community Disassembly: Dung Beetles, Density Functions, and Forest Fragmentation. Conservation Biology 2008, 22, 1288–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultid-Medina, C.A.; Escobar, F. Assessing the Ecological Response of Dung Beetles in an Agricultural Landscape Using Number of Individuals and Biomass in Diversity Measures. Environmental Entomology 2016, 45, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Alba, Andrés Felipe; Carvajal-Cogollo, Juan E.; Morales Irina. Diversidad de Escarabajos Coprófagos En Dos Periodos de Precipitación Anual En Un Fragmento de Bosque Andino, Santander, Colombia. Intropica 2023, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.C.; Hernández, M.I.M. Dung Beetle Assemblages (Coleoptera, Scarabaeinae) in Atlantic Forest Fragments in Southern Brazil. Rev. Bras. entomol. 2013, 57, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.G.D.; Hernández, M.I.M. Scale-Dependence of Processes Structuring Dung Beetle Metacommunities Using Functional Diversity and Community Deconstruction Approaches. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Ramírez, S.; Tscharntke, T.; Armbrecht, I.; Torres, W.; Grass, I. Decrease in B-diversity, but Not in A-diversity, of Ants in Intensively Managed Coffee Plantations. Insect Conserv Diversity 2020, 13, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, P.G.; Lobo, J.M.; Hernández, M.I.M. The Role of Habitat and Daily Activity Patterns in Explaining the Diversity of Mountain Neotropical Dung Beetle Assemblages. Austral Ecology 2019, 44, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, M.B.; Aranibar, J.N.; Serrano, A.M.; Chacoff, N.P.; Vázquez, D.P. Dung Beetles and Nutrient Cycling in a Dryland Environment. CATENA 2019, 179, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

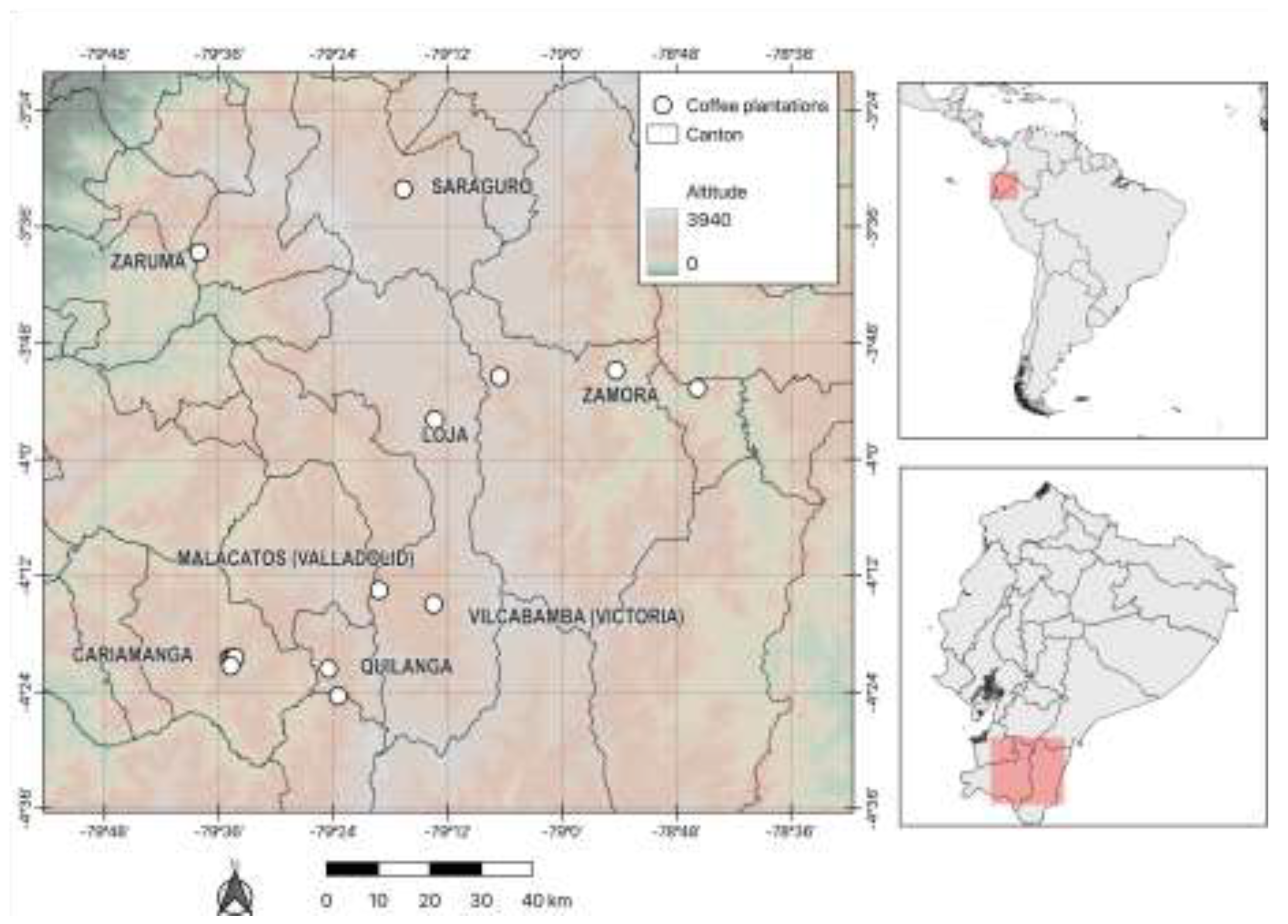

| Province | Canton | Latitude (S) | Longitude (W) | Altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Oro | Zaruma | -3.749 | -79.727 | 962 |

| -3.719 | -79.65 | 1123 | ||

| -3.644 | -79.635 | 1115 | ||

| Loja | Cariamanga | -4.342 | -79.582 | 1815 |

| -4.343 | -79.577 | 1865 | ||

| -4.34 | -79.571 | 2002 | ||

| -4.355 | -79.579 | 2095 | ||

| Loja | -3.931 | -79.222 | 2100 | |

| -4.224 | -79.319 | 1969 | ||

| -4.249 | -79.224 | 1700 | ||

| Quilanga | -4.360 | -79.408 | 1606 | |

| -4.406 | -79.391 | 1477 | ||

| Saraguro | -3.535 | -79.277 | 1180 | |

| Zamora Chinchipe | Zamora | -3.847 | -78.905 | 1012 |

| -3.858 | -79.109 | 1856 | ||

| -3.878 | -78.762 | 817 |

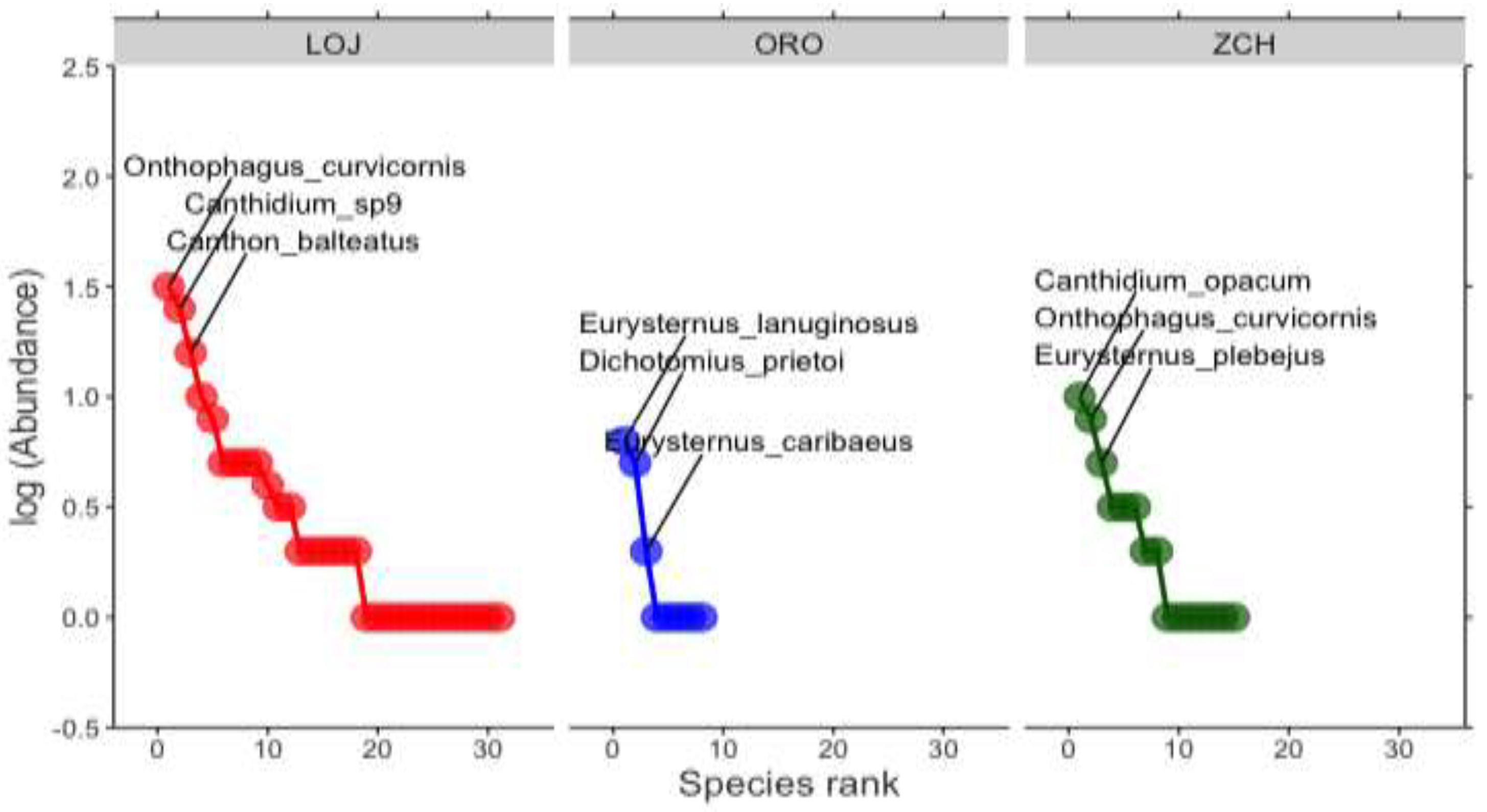

| Species | LOJ | ORO | ZCH | Total | Food preference | Functional group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aphodius sp. 1 Illiger, 1798 | 1 | 1 | C | E | ||

| Canthidium coerulescens Balthasar, 1939 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | C | P |

| Canthidium opacum Balthasar, 1939 | 5 | 9 | 14 | C | P | |

| Canthidium sp. 11 Erichson, 1847 | 1 | 1 | C | P | ||

| Canthidium sp. 9 Erichson, 1847 | 24 | 24 | C | P | ||

| Canthon balteatus Boheman, 1858. | 17 | 17 | C | T | ||

| Canthon sp. 1 Hoffmannsegg, 1817 | 1 | 1 | C | T | ||

| Canthon sp. 2 Hoffmannsegg, 1817 | 1 | 1 | C | T | ||

| Canthon sp. 4 Hoffmannsegg, 1817 | 5 | 5 | C | T | ||

| Canthon sp. 5 Hoffmannsegg, 1817 | 1 | 1 | C | T | ||

| Canthon sp. 7 Hoffmannsegg, 1817 | 2 | 2 | C | T | ||

| Coprophanaeus ohausi Felsche, 1911 | 2 | 2 | G | P | ||

| Deltochilum robustus Molano & González, 2009 | 1 | 1 | G | T | ||

| Dichotomius talaus Blanchard, 1845 | 1 | 1 | 2 | C | P | |

| Dichotomius prietoi Martínez & Martínez, 1982 | 5 | 5 | C | P | ||

| Dichotomius problematicus Lüederwaldt, 1924 | 5 | 1 | 6 | C | P | |

| Dichotomius protectus Roze 1955 | 3 | 3 | C | P | ||

| Dichotomius quinquelobatus Felsche, 1901 | 1 | 1 | C | P | ||

| Dichotomius sp. 2 Hope, 1838 | 1 | 1 | C | P | ||

| Eurysternus caribaeus Herbst, 1789 | 2 | 2 | 4 | C | E | |

| Eurysternus lanuginosus Génier, 2009 | 6 | 6 | C | E | ||

| Eurysternus plebejus Harold, 1880 | 1 | 5 | 6 | C | E | |

| Onoreidium ohausi Arrow, 1931 | 2 | 2 | C | P | ||

| Ontherus brevicollis Kirsch, 1871 | 1 | 1 | C | P | ||

| Ontherus pubens Génier, 1996 | 4 | 2 | 6 | C | P | |

| Onthophagus confusus Boucomont, 1932 | 5 | 5 | C | P | ||

| Onthophagus curvicornis Latreille, 1811 | 34 | 8 | 42 | C | P | |

| Onthophagus dicranoides Balthasar, 1939 | 2 | 2 | C | P | ||

| Onthophagus nabelecki Balthasar, 1939 | 11 | 11 | C | P | ||

| Onthophagus rubrescens Blanchard, 184 | 8 | 8 | C | P | ||

| Onthophagus transisthmius Howden & Young, 1981 | 3 | 3 | C | P | ||

| Oxysternon conspicillatum Weber, 1801 | 1 | 1 | 2 | C | P | |

| Oxysternon silenus d’Olsoufieff, 1924 | 1 | 1 | C | P | ||

| Phanaeus achilles Boheman, 1858 | 3 | 3 | C | P | ||

| Phanaeus haroldi Kirsch, 1871 | 1 | 3 | 4 | C | P | |

| Phanaeus lunaris Taschenberg, 1870 | 1 | 1 | 2 | C | P | |

| Phanaeus meleagris Blanchard, 1843 | 1 | 1 | C | P | ||

| Scatimus mostrosus Balthasar, 1939 | 2 | 2 | C | P | ||

| Uroxys lojanus Arrow, 1933 | 1 | 1 | C | P | ||

| Uroxys sp. 5 Westwood, 1842 | 1 | 1 | C | P | ||

| Uroxys sp. 6 Westwood, 1842 | 2 | 2 | C | P | ||

| Uroxys sp. 7 Westwood, 1842 | 1 | 1 | C | P | ||

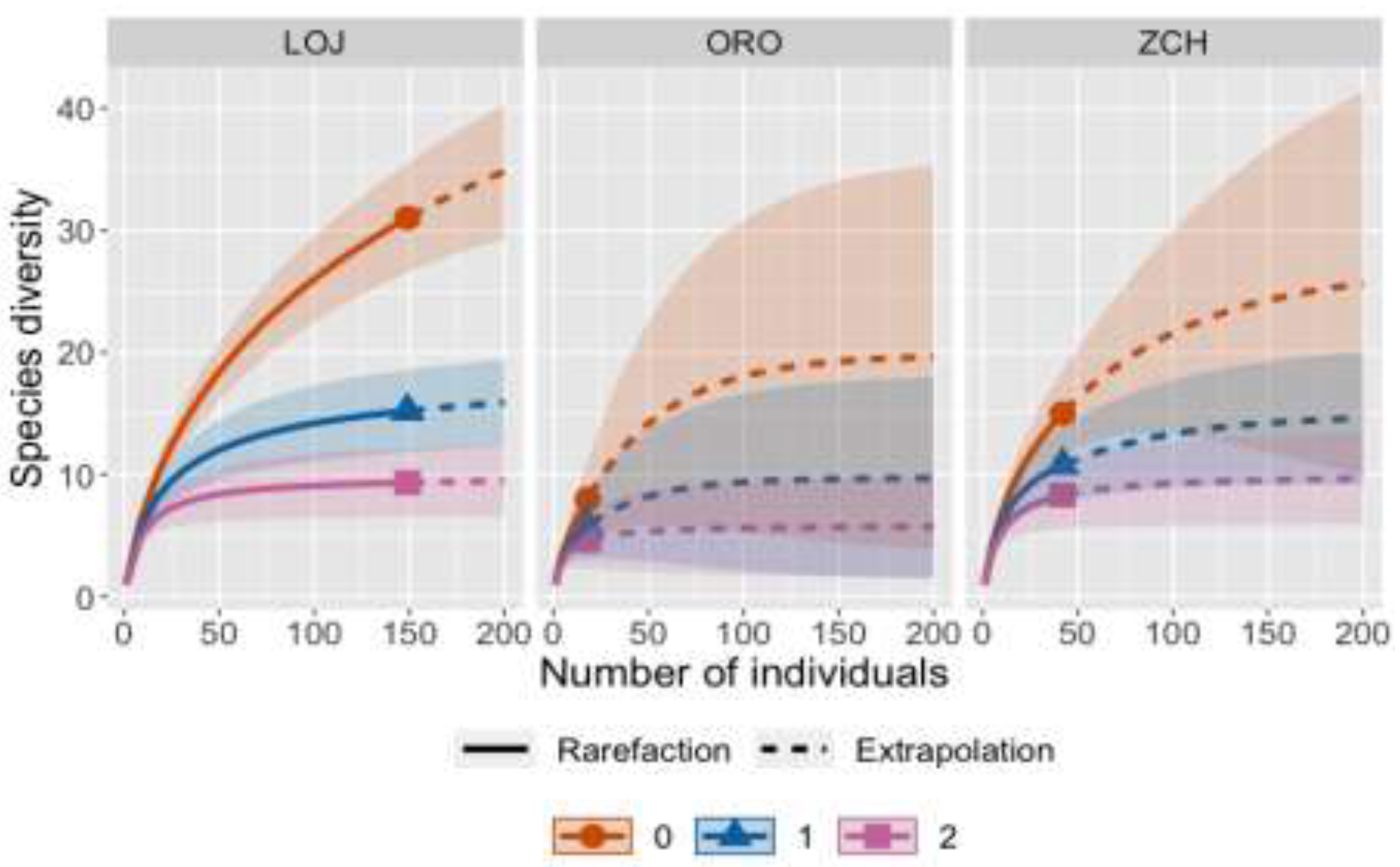

| Abundance | 149 | 18 | 42 | 209 | ||

| Richness | 31 | 8 | 15 | 42 | ||

| Chao1 | 42.1 | 12.7 | 21.8 |

| Responce Variable | Explanatory Variable | Standard error | Z-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abundance | Habitat | |||

| (Intercept) | 0.082 | 19.164 | <0.001 | |

| El Oro | 0.250 | -3.042 | 0.002 | |

| Zamora Chinchipe | 0.175 | -3.093 | 0.002 | |

| Chi test: | ||||

| Habitat | <0.001 | |||

| Abundance | Food preference | |||

| (Intercept) | 0.070 | 19.76 | <0.001 | |

| Generalist | 0.581 | -1.67 | 0.095 | |

| Chi test: | ||||

| Food preference | 0.048 | |||

| Abundance | Functional group | |||

| (Intercept) | 0.243 | 4.294 | <0.001 | |

| Paracoprid | 0.255 | 1.353 | 0.176 | |

| Telecoprid | 0.308 | 1.122 | 0.262 | |

| Chi test: | ||||

| Functional group | 0.360 | |||

| Abundance | Species | |||

| (Intercept) | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Canthidium sp. 9 | 1.021 | 3.114 | 0.002 | |

| Canthon balteatus | 1.029 | 2.753 | 0.006 | |

| Onthophagus curvicornis | 1.012 | 3.009 | 0.003 | |

| Onthophagus nabelecki | 1.044 | 2.296 | 0.022 | |

| Onthophagus rubrescens | 1.061 | 1.961 | 0.050 | |

| Chi test: | ||||

| Species | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).