Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Dung Beetle Sampling

2.2. Sampling of Environmental Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

AI Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| dbRDA | Distance-Based Redundancy Analysis |

| distLM | Distance-Based Linear Models |

| g | gram |

| PCO | Ordering of Main Components |

| SUTs | Land Use Systems |

| v/v | volume/volume |

References

- Kim, D.; Sexton, J.O.; Townshend, Jr. Accelerated deforestation in the humid tropics from the 1990s to the 2000s. Geophysical Research Letters 2015, 42, 3495–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, P.G.; Hernández, M.I.M. Spatial variation of dung beetle assemblages associated with forest structure in remnants of southern Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Rev Bras Entomol 2016, 60, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.; et al. Anthropogenic land consolidation intensifies zoonotic host diversity loss and disease transmission in human habitats. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2024, 9, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies-Colley, R.J. Payne, G. W.; Van-Elswijk, M. Microclimate gradients across a forest edge. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 2000, 24, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Redding, T.E.; Hope, G.D.; Fortin, M.J.; Schmidt, M.G.; Bailey, W.G. Spatial patterns of soil temperature and moisture across subalpine forest-clearcut edges in the southern interior of British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Soil Science 2003, 83, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.M.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Science Advances 2015, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Maxwelll, M.; Hu, G.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Yu, M. How does habitat fragmentation affect the biodiversity and ecosystem functioning relationship? Landscape Ecology 2018, 33, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, B.S. ; Forest Complexity Drives Dung Beetle Assemblages along an Edge-interior Gradient in the Southwest Amazon Rainforest”. Ecological Entomology 2020, 45, 259–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrochers, A.; Fortin, M.J. Understanding avian responses to forest boundaries: a case study with chickadee winter flocks. Oikos 2000, 91, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, T.A.; Hernández, M.I.M.; Barlow, J.; Peres, C.A. Understanding the biodiversity consequences of habitat change: the value of secondary and plantation forests for neotropical dung beetles. Journal of Applied Ecology 2008, 45, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korasaki, V.; Lopes, J.; Brown, G.G.; Louzada, J. Using dung beetles to evaluate the effects of urbanization on Atlantic Forest biodiversity. Insect Science 2013, 20, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.L.V. Scholtz, C. H.Dung beetle conservation biogeography in southern Africa: current challenges and potential effects of climatic change. Biodiversity and Conservation 2020, 29, 667–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klink, C.A.; Machado, R.B. Conservation of the brazilian Cerrado. Conservation Biology 2005, 19, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MapBiomas, Coleção 9.0. Série Anual de Mapas de Cobertura e Uso da Terra do Brasil. 2025. Access: https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/infograficos/.

- Ab’saber, A.N. O domínio dos cerrados: introdução ao conhecimento. Ed. Fundação Centro de Formação do Servidor Público. 3, 4, 41-55, 1983.

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Fonseca, G.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [CrossRef]

- Overbeck, G. E.; et al. Conservation in Brazil needs to include non-forest ecosystems. Diversity and Distributions 2015, 21, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, C. M. A.; Lara, M. A.; Puker, A. Cerrado vegetation conversion into exotic pastures negatively impacts flower chafer beetle assemblages in the west-central brazil. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science 2021, 41, 2459–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.I.M.; Vaz-de-Mello, F.Z. Seasonal and spatial species richness variation of dung beetle (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae s. str.) in the Atlantic Forest of southeastern Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 2009, 153, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, R.; Louzada, J.; Almeida, S.; Macedo, R.; Barlow, J. Evaluating the impacts and conservation value of exotic and native tree afforestation in Cerrado grasslands using dung beetles. Insect Conservation and Diversity 2011, 5, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueiras, B.; Tabarelli, M.; Leal, I.; Vaz-De-Mello, F.Z.; Iannuzzi, L. Dung beetle persistence in human-modified landscapes: combining indicator species with anthropogenic land uses and fragmentation-related effects. Ecological Indicators 2015, 55, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, E.; Larsen, T.; Spector, S.; Davis, A.L.; Escobar, F.; Favila, M.; Vulinec, K. Global dung beetle response to tropical forest modification and fragmentation: a quantitative literature review and meta-analysis. Biological Conservation 2007, 137, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Cifuentes, A.; Munevar, A.; Gimenez, V.C.; Gatti, M.G.; Zurita, G.A. Influence of land use on the taxonomic and functional diversity of dung beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae) in the southern Atlantic Forest of Argentina. Journal of Insect Conservation 2017, 21, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, T.K.; Rawtani, D.; Agrawal, Y.K. Bioindicators: the natural indicator of environmental pollution. Frontiers in Life Science 2016, 9, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, E.; Spector, S.; Louzada, J.; Larsen, T.; Amezquitad, S.; Favila, M.E. Ecological functions and ecosystem services provided by Scarabaeinae dung beetles. Biological Conservation 2008, 141, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, E. ; Gardner, T.; Peres, C.A.; Spector, S. Co-declining mammals and dung beetles: an impending ecological cascade. Oikos 2009, 118, 481–487. [CrossRef]

- Braga, R.F.; Korasaki, V.; Audino, L.D.; Louzada, J. Are dung beetles driving dung-fly abundance in traditional agricultural areas in the amazon? Ecosystems 2012, 15, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, R.F.; Korasaki, V.; Andresen, E.; Louzada, J. Dung Beetle Community and Functions along a Habitat-Disturbance Gradient in the Amazon: A Rapid Assessment of Ecological Functions Associated to Biodiversity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-de-Mello, F.Z. Estado actual de conhecimento dos Scarabaeidae s. str. (Coleoptera: Scarabaeoidea) do Brasil. Proyecto Iberoamericano de Biogeografía y Entomología Sistemática : PRIBES 2000 : trabajos del 1er taller iberoamericano de entomología sitemáica. 2000, ISBN 84-922495-1-X, 183-195.

- Marsh, C.J.; Louzada, J.; Beiroz, W.; Ewers, R.M. Optimizing Bait for Pitfall Trapping of Amazonian Dung Beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae). Plos One 2013, 8, e73147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE – Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Cidades. Access: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/mg/frutal.

- Álvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Gonçalves JL d, M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.L.; Silva, R.J.; Fernandes, I.M.; Sousa, W.O.; Vaz-De-Mello, F.Z. Species composition and community structure of dung beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Scarabaeinae) compared among savanna and forest formations in the southwestern Brazilian Cerrado. Zoologia 2020, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobis, M. “SideLook 1.1-Imaging software for the analysis of vegetation structure with true-colour photographs.” http://www. appleco. ch/ (2005).

- Mitchell, K. Quantitative analysis by the point-centered quarter method. arXiv 2010, arXiv:1010.3303. [Google Scholar]

- Hijbeek, R.; Koedam, N.; Khan, M.N.I.; Kairo, J.G.; Schoukens, J.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F. An evaluation of plotless sampling using vegetation simulations and field data from a mangrove forest. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESRI - Environmental Systems Research Institute. “Topographic”. Base map collection. 19 de fevereiro de 2020. Access: http://www.arcgis.com/home/.

- R Core Team. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.

- Anderson, M.J.; Ellingsen, K.; McArdle, B.H. Multivariate dispersion as a measure of beta diversity. Ecology Letters 2006, 9, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecology 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N. PRIMER v6: User Manual/Tutorial (Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research). PRIMER-E, Plymouth. 2006.

- McCune, B.; Mefford, M.J. PC-ORD Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Data. Version 4. MjM Software Design, Gleneden Beach, Oregon, USA. 1999.

- Dufrêne, M.; Legendre, P. Species Assemblages and Indicator Species: The Need for a Flexible Asymmetrical Approach. Ecological Monographs 1977, 67, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeoch, M.A.; Rensburg, B.J.V.; Botes, A. The verification and application of bioindicators: a case study of dung beetles in a savanna ecosystem. Journal of Applied Ecology 2002, 39, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdú, J.R.; Numa, C.; Hernández-Cuba, O. The influence of landscape structure on ants and dung beetles diversity in a mediterranean savanna—forest ecosystem. Ecological Indicators 2011, 11, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Anderson, M.J. Distance-based redundancy analysis: testing multispecies responses in multifactorial ecological experiments. Ecological Monographs 1999, 69, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J.; Gorley, R.N.; Clarke, K.R. PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: guide to software and statistical methods. PRIMER-E Ltd, Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Plymouth, UK. 214. 2008.

- Chao, A.; Jost, L. Coverage-based rarefaction and extrapolation: standardizing samples by completeness rather than size. Ecology 2012, 93, 2533–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-de-Jesús, H.A.; Arroyo-Rodríguez, V.; Andresen, E.; Escobar, F. Forest loss and matrix composition are the major drivers shaping dung beetle assemblages in a fragmented rainforest. Landscape Ecology 2015, 31, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.I.M.; Barreto, P.S.C.S.; Costa, V.H.; Creão-Duarte, A.J.; Favila, M.E. Response of a dung beetle assemblage along a reforestation gradient in restinga forest. Journal of Insect Conservation 2014, 18, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdú, J.R.; Galante, E. Behavioural and morphological adaptations for a low-quality resource in semi-arid environments: dung beetles (Coleoptera, Scarabaeoidea) associated with the european rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculusl. ). Journal of Natural History 2004, 38, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righi, C.A.; Sandoval-Rodríguez, C.; Ferreira, E.N.L.; Godoy, W.A.C.; Cognato, A.I. Microclimatic conditions for dung beetle (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) occurrence: land use system as a determining factor. Environmental Entomology 2018, 47, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, B. M.; Pantoja, D. L.; Sousa, H. C.; Queiroz, T. A.; Colli, G.R. Long-term, fire-induced changes in habitat structure and microclimate affect cerrado lizard communities. Biodiversity and Conservation 2019, 29, 1659–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, S.S.P.; Louzada, J.; Sperber, C.F.; Barlow, J. Subtle land-use change and tropical biodiversity: dung beetle communities in cerrado grasslands and exotic pastures. Biotropica 2011, 43, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, P.M.; Arellano, L.; Hernández, M.I.M.; Ortiz, S.L. Response of the copronecrophagous beetle (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae) assemblage to a range of soil characteristics and livestock management in a tropical landscape. Journal of Insect Conservation 2015, 19, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, R.; Audino, L. D.; Korasaki, V.; Louzada, J. Conversion of cerrado savannas into exotic pastures: the relative importance of vegetation and food resources for dung beetle assemblages. Agriculture, Ecosystems &Amp; Environment 2020, 288, 106709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martello, F.; Andriolli, F.S.; Souza, T.B.; Dodonov, P.; Ribeiro, M.C. Edge and land use effects on dung beetles (coleoptera: scarabaeidae: scarabaeinae) in brazilian cerrado vegetation. Journal of Insect Conservation 2016, 20, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.M.Q.; Oliveira, V.H.F.; Maciel, R.; Beiroz, W.; Korasaki, V.; Louzada, J. Variegated tropical landscapes conserve diverse dung beetle communities. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, T.H.; Williams, N.M.; Kremen, C. Extinction order and altered community structure rapidly disrupt ecosystem functioning. Ecology Letters 2005, 8, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artuzo, F.D.; Foguesatto, C.R.; Souza, Â.R.L.; Silva, L.X. Costs management in maize and soybean production. Review of Business Management 2018, 20, 2–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleixo, A. Effects of selective logging on a bird community in the brazilian atlantic forest. The Condor 1999, 101, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.; et al. (2018) Inconsistent effects of landscape heterogeneity and land-use on animal diversity in an agricultural mosaic: a multi-scale and multi-taxon investigation. Landscape Ecology 2018, 33, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R.V.; Vaz-de-Mello, F. Z. New brachypterous species of Dichotomius Hope, with taxonomic notes in the subgenus Luederwaldtinia Martínez (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Scarabaeinae). Zootaxa 2013, 3609, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchiori, C.H.; Caldas, E.R.; Almeida, K. Succession of scarabaeidae on bovine dung in Itumbiara, Goiás, Brazil. Neotropical Entomology 2003, 32, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.R.; Barros, A.T.M.; Puker, A.; Taira, T.L. Diversidade de besouros coprófagos (coleoptera, scarabaeidae) coletados com armadilha de interceptação de voo no pantanal sul-mato-grossense, brasil. Biota Neotropica 2010, 10, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissiani, A.S.O.; Vaz-de-Mello, F.Z.; Campelo-Junior, J.H. Dung beetles of brazilian pastures and key to genera identification (coleoptera: scarabaeidae). Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira 2017, 52, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, R.; Anderson, J. The effects of different pasture and rangeland ecosystems on the annual dynamics of insects in cattle droppings. Hilgardia 1977, 45, 31–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, C.M.A.; Peres, N.D.; Holdbrook, R. Patterns of alimentary resource use by dung beetles in introduced brazilian pastures: cattle versus sheep dung. Entomological Science 2020, 23, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barretto, J.W.; Cultid-Medina, C.A.; Escobar, F. Annual abundance and population structure of two dung beetle species in a human-modified landscape. Insects 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompeo, P.N.; Oliveira-Filho, L.C.I.; Klauberg-Filho, O.; Mafra, A.L.; Baretta, C.R.D.M.; Baretta, D. Diversidade de Coleoptera (Arthropoda: Insecta) e atributos edáficos em sistemas de uso do solo no Planalto Catarinense. Scientia Agraria Paranaensis 2016, 2016. 17, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogoni, J.A.; Hernández, M.I.M. Attractiveness of native mammal’s feces of different trophic guilds to dung beetles (coleoptera: scarabaeinae). Journal of Insect Science 2014, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tixier, T.; Bloor, J.; Lumaret, J. Species-specific effects of dung beetle abundance on dung removal and leaf litter decomposition. Acta Oecologica 2015, 69, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzada, J.N.C.; Silva,P.R. Utilisation of introduced Brazilian pastures ecosystems by native dung beetles: diversity patterns and resource use. Insect Conservervation and Diversity 2009, 2:45–52. [CrossRef]

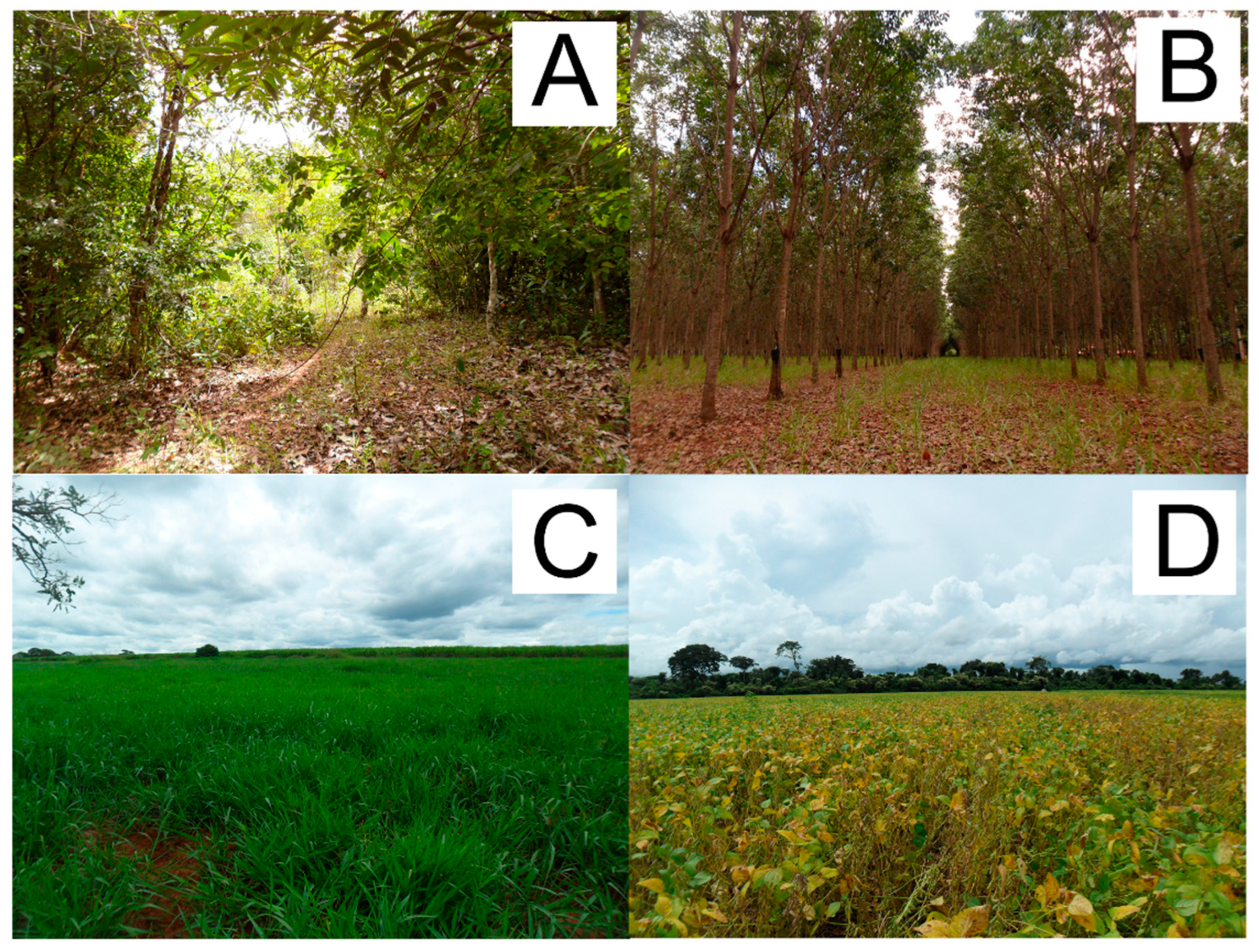

| Land Use | Caracterização |

|---|---|

| Forest | Areas with a predominance of tree species cover, with no history of cutting and felling |

| Rubber tree | Plantations of Hevea brasiliensis L. (rubber tree), the main management carried out are: land clearing, straw maintenance to control the growth of the herbaceous stratum and the understory |

| Pasture | Consisting of areas intended for livestock production, formed by exotic pastures, with a predominance of Urochloa spp. (Syn. Brachiaria spp.). |

| Soy | Consisting of conventional soybean monocultures (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). |

| Tribo/Espécie | Sistema | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Floresta | Pastagem | Seringueira | Soja | ||

| Ateuchini | |||||

| Agamopus viridis (Boucomont, 1928) | - | 15 | - | - | 15 |

| Genieridium bidens (Balthasar, 1938) | - | 101 | 1 | 73 | 184 |

| Ateuchus sp. 1 | - | 2 | - | 1 | 3 |

| Coprini | |||||

| Canthidium refulgens (Boucomont, 1928) | 62 | 15 | 86 | 8 | 171 |

| Canthidium sp. 1 | 3 | - | 3 | - | 6 |

| Canthidium sp. 2 | 1 | - | 3 | - | 4 |

| Canthidium sp. 3 | 6 | 11 | 26 | - | 43 |

| Canthidium sp. 4 | 2 | - | 1 | - | 3 |

| Canthidium sp. 5 | 14 | - | 5 | 63 | 82 |

| Dichotomius bos (Blanchard, 1843) | 2 | 6 | - | 4 | 12 |

| Dichotomius aff. carbonarius (Mannerhein, 1829) | 60 | - | 33 | 44 | 137 |

| Dichotomius glaucus (Harold, 1869) | 8 | - | - | - | 8 |

| Dichotomius nisus (Oliver, 1789) | 240 | 116 | 77 | 80 | 513 |

| Isocopris inhatus (German, 1824) | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Ontherus appendiculatus (Mannerheim, 1829) | 16 | - | 31 | - | 47 |

| Ontherus sp. 1 | 26 | 11 | 13 | 18 | 68 |

| Ontherus sp. 2 | 18 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 46 |

| Ontherus sp. 3 | 21 | - | 12 | - | 33 |

| Deltochilini | |||||

| Anomiopus sp. 1 | 3 | - | - | - | 3 |

| Canthon conformis (Harold, 1868) | 77 | - | 60 | 6 | 77 |

| Canthon lituratus (Germar, 1824) | 4 | - | - | 4 | 8 |

| Canthon ornatus (Redtennbacher, 1868) | - | 6 | - | - | 6 |

| Deltochilum aff. guyanense (Paulian, 1938) | 1 | - | - | 1 | |

| Pseudocanthon sp. 1 | 4 | 14 | - | - | 28 |

| Onthophagini | |||||

| Onthophagus buculus (Mannerheim, 1829) | 25 | 13 | - | 3 | 41 |

| Onthophagus hircus (Billberg, 1815) | 87 | - | - | 87 | |

| Onthophagus ptox (Erichson, 1847) | - | - | 14 | 1 | 15 |

| Phanaeini | |||||

| Coprophanaeus cyanescens (d’Olsoufieff, 1924) | 17 | - | 2 | - | 19 |

| Coprophanaeus spitzi (Pessôa, 1935) | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| Dendropaemon nitidicollis (d’Olsoufieff, 1924) | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Diabroctis mimas (Linnaeus, 1758) | - | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Gromphas inermis (Harold, 1869) | - | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| Phanaeus palaeno (Blanchard & Brullé, 1845) | 5 | 12 | - | - | 17 |

| Trichillum externepunctatum (Borre, 1886) | 52 | 146 | 76 | 86 | 360 |

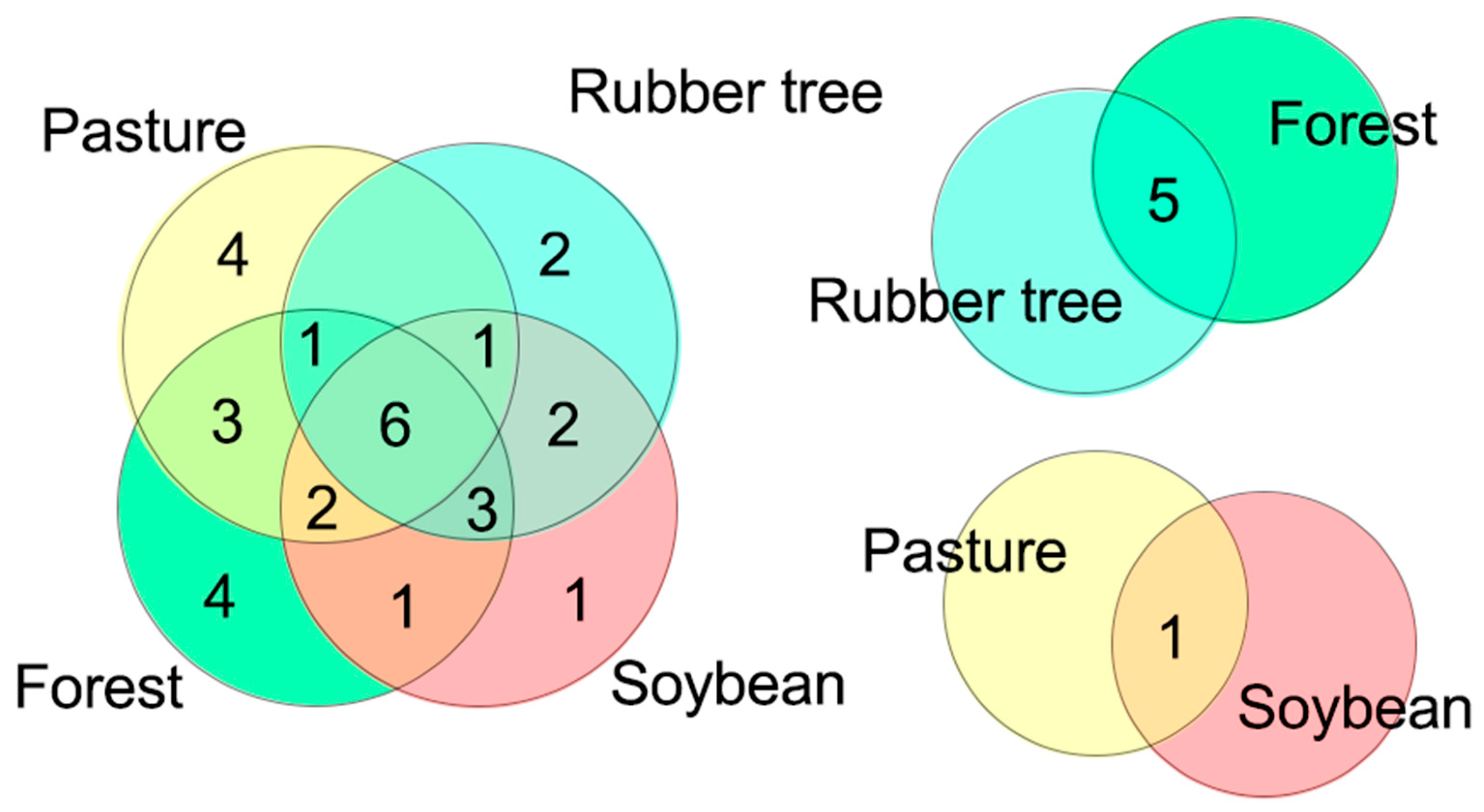

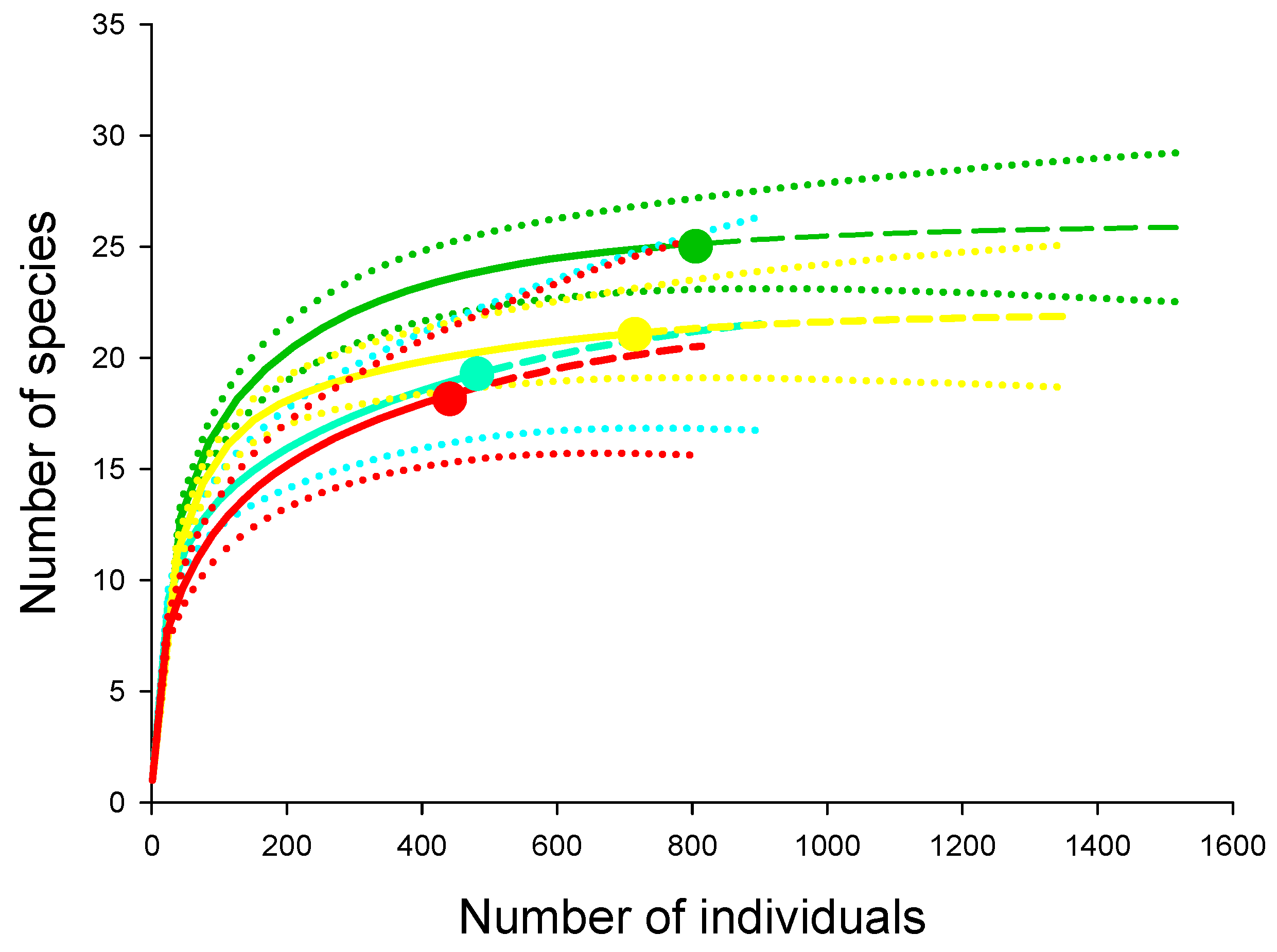

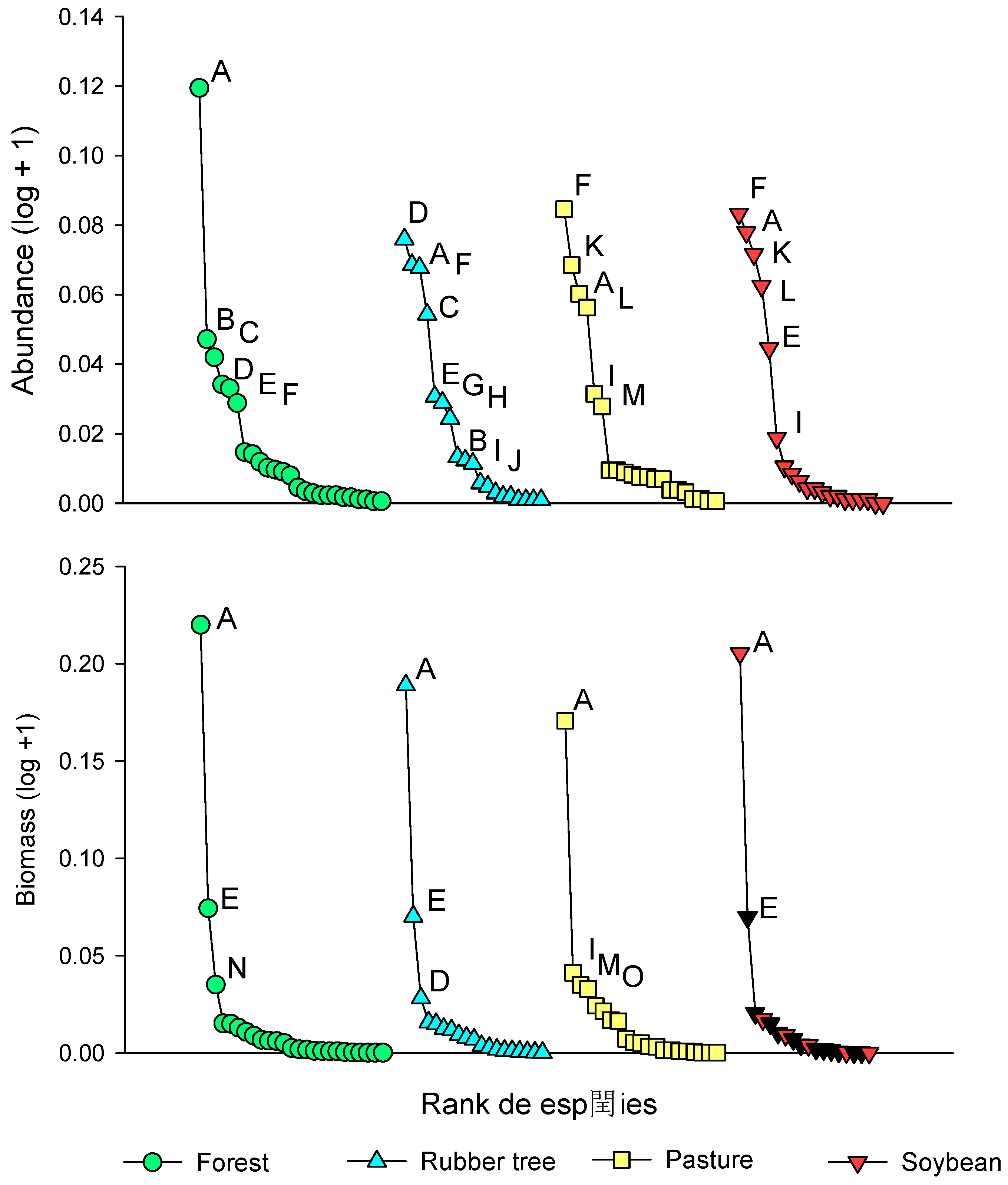

| Number of Species | 25 | 17 | 19 | 17 | 34 |

| Number of Individuals | 758 | 679 | 751 | 406 | 2101 |

| GROUP | PERMANOVA | PERMDISP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | P (Perm.) | T | P (Perm.) | ||

| Soybean X Forest | 1,761 | 0,007 | 0,29698 | 0,888 | |

| Soybean X Pasture | 1,0752 | 0,344 | 0,6901 | 0,6 | |

| Soybean vs. Rubber Tree | 1,8527 | 0,011 | 1,094 | 0,282 | |

| Forest vs. Pasture | 1,9018 | 0,011 | 0,70553 | 0,616 | |

| Forest X Rubber Tree | 0,90103 | 0,628 | 0,84589 | 0,619 | |

| Pasture X Rubber Tree | 2,34 | 0,005 | 0.02549 | 0,984 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).