Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

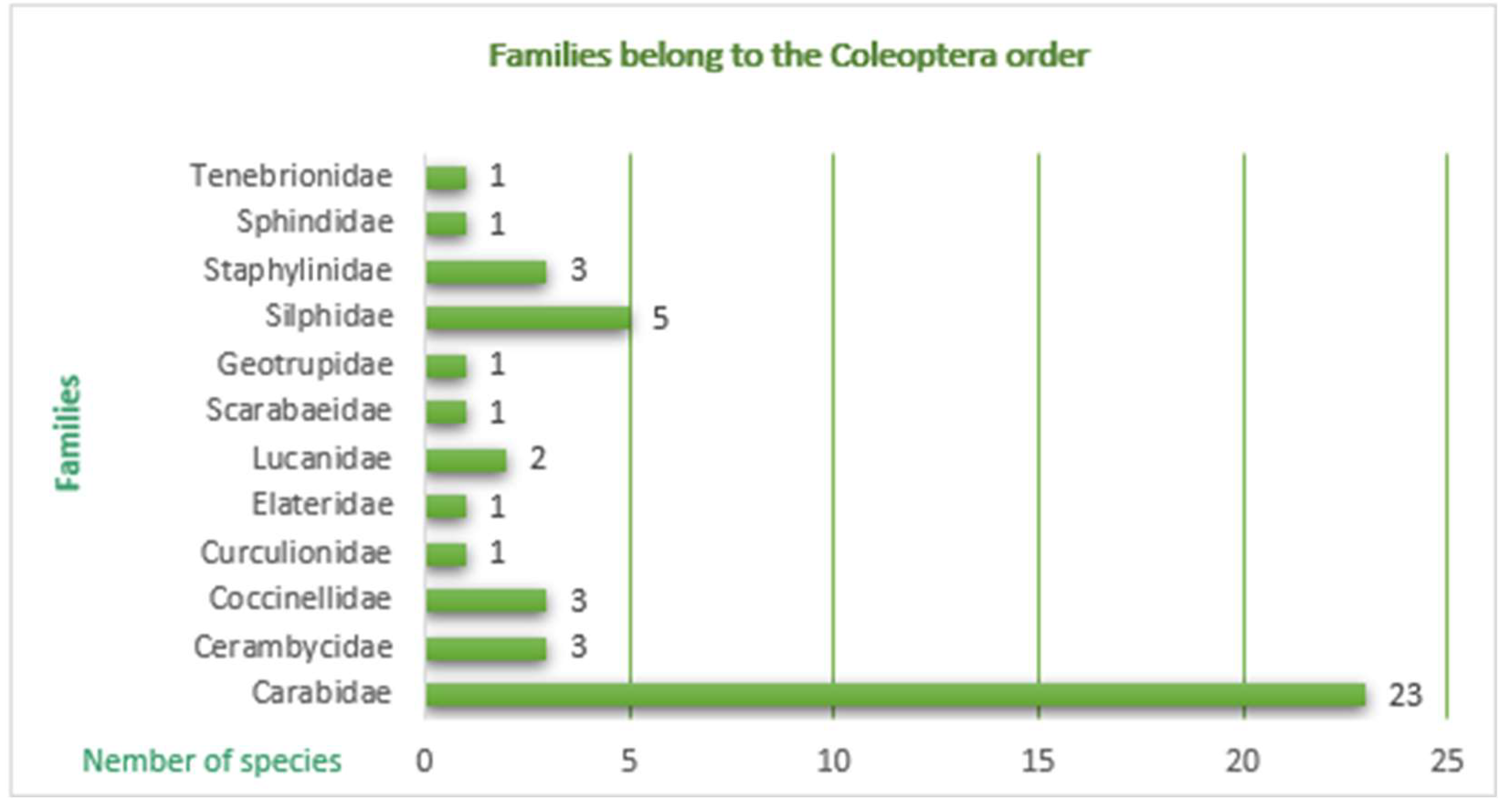

This study presents findings over three years of research into beetle diversity in two urban ecosystems in Sibiu, Central Romania: The Sub Arini Park (referred to after as Arini) (semi-anthropic) over 150 years old within the city, and the Dumbrava Sibiului Nature Reserve (referred to after as Dumbrava) (oak forest) over 170 years old on the city outskirts. Ground-trapping coleopteran collection in both locations (2021-2022 for Dumbrava, 2023 for Arini) was carried out in spring, summer, and autumn seasons. The study aimed to identify species and calculate ecological indices (abundance, dominance, constancy, Index of ecological significance) as input into conservation. The nature of collection technique did mean larger beetle species were collected, being the primary nature of this study. In total, 12 beetle families were identified covering 46 coleopteran species from 5,008 specimens. Section 3.1 records in table format all the beetles found. Carabid species diversity was significantly higher in Arini, due to the more varied vegetation. In Dumbrava the forest edge plays an important role in seasonal beetle migrations. The shady areas with shrub vegetation favor predatory and scavenging shrub species such as Carabus (Procustes) coriaceus Linnaeus, 1758 and Phosphuga (Silpha) atrata Linnaeus, 1758. Dominant species were: Carabus violaceus Linnaeus, 1758 and Pterostichus oblongopunctatus Fabricius, 1787 (crepuscular predators).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Trap components:

- the protection vessel: a 2- litre container with holes in the base to avoid water stagnation;

- Collection vessel: another container smaller than 1.5 litres, inserted into the protection vessel, for collecting insects.

- Preservation solution: a solution of water and detergent (without perfume) was used to preserve the collected insects.

- Abundance: the proportion of individuals of a species in the total individuals collected.

- Dominance: the proportion of a species in the community (D1<1- sporadic, D2=2-4 subdominant, D3=2,1-4 dominant, D4=4,1-8 subdominant, D5=8,1-16 dominant, D6>16 eudominant).

- Constant: frequency of occurrence of the species in the samples (C1=0-10 very rare, C2=10,1-25 rare, C3=25,1-45 rare, C4=45,1-70 constant, C5=70,1-100 constant).

- Index of ecological significance (Dzuba-W Index): W1 with values 0,1% - incidental species, W2 values between 0,1-1% - accessory species, W3 values between 1,1-5% - associated species, W4 values between 0,51-10% - complementary species, W5 values more than 10-20% - characteristic species, W6 >20 main species.

2.1. Dumbrava Sibiului Forest (2021-2022)

2.1.1. Approach to Sampling Vegetation Data

2.1.2. Trapping/Sampling and Insect Identification

2.2. Details About the Park Under Arini (2023)

2.2.1. Approach to Vegetation Data Sampling

| No. | Association | characteristic species | area |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Aegopodium-Alnetum Karpati and Jurko 1961 |

Alnus glutinosa, Aegopodium podagraria, Solanum dulcamara, Angelica silvestris, Lycopus europaeus, Mentha aquatica, Lysimachia vulgaris. Rudbeckia laciniata is an adventive species, a rarity brought from the meadows of Avrig and has become dominant | 2,3,4,5 |

| 2 | Agrostetum albae | Agrostis alba, Ranunculus repens, Carex vulpina, Juncus effusus, Trifolium repens | 2 |

| 3 |

Glycerietum aquaticae Nowinki 1928 |

form a specific appearance and Carex gracilis is a characteristic species | 6 |

| 4 | Scipo-Pbramietetum | classified in the association Rudbeckia laciniata | 5,6 |

| 5 | Quercutum-roboris petraeae | Quercus robur, Quercus petraea, Carpinus betulus, Cerasus avium, Acer campestre | 6 |

2.2.2. Trapping/Sampling and Insect Identification

| Trap | Location | Area description |

|---|---|---|

| Trap 1 | between an oak root and a slope, 5 meters from an alley. | under an oak tree in a disused drainage ditch covered with dry leaves (Figure 7-t1). |

| Trap 2 | positioned between three trees, relatively close to an alley. | area with exposed soil and rare grasses, inside the forest (Figure 7-t2). |

| Trap 3 | in a disused drainage ditch under a footbridge. | area exposed to the sun with no tree branches above, next to an alley. Under the trap were dry leaves (Figure 7-t3). |

| Trap 4 | between a garden fence and a path in the park. | exposed area near the driveway. In summer it was overgrown, but in September the ground was exposed |

| Trap 5 | placed between two distant trees in a relatively exposed area | a considerable distance from paths or roads. thick grass, but not too tall |

| Trap 6 | at the root of a willow, next to a concrete slab | shaded area away from paths. under the trap were dry leaves, twigs and exposed soil |

| Trap 7 | positioned in the middle of the slope towards the Avrig road | the area exposed to the sun. in summer it was covered with small, dense vegetation |

| Trap 8 | found at the root of an oak tree near a pile of fallen branches. | between a dirt road and the trinbah tachelajul. earth covered with twigs, gravel and waste, no vegetation |

| Trap 9 | in an enclosed area under the branches of several trees. | near a fallen stump, away from driveways or roads. covered with a thick layer of dry leaves and plant debris |

| Trap 10 | located in an open area between the park alley and the outside sidewalk | close to a bridge, surrounded by wood debris. no vegetation |

| Trap 11 | positioned between several trees next to a dirt road. | exposed ground with dry leaves and patches covered with ivy. ivy had retreated in September |

| Trap 12 | found among some small dandelions in a sunny area. | a long distance from roads or paths. blades of grass |

| Trap 13 | located under several small trees, shaded by larger trees. | Enclosed area with no sun exposure. very close to a dirt road and about 5-6 feet from an alley. Dry leaves and exposed soil were under trapped |

| Trap 14 | between the driveway and a ditch with occasional water. | area well exposed to the sun, covered with rich vegetation (20-25 cm grass) |

| Trap 15 | under several tall trees next to the outside pavement. | shaded area covered with dry leaves and branches, no vegetation |

| Trap 16 | in a sunny, treeless area about 7-8 meters from an alley. | rich vegetation (grasses and broad-leaved plants) |

| Trap 17 | sunny, treeless area close to an alleyway | nearby was a rotting stump. under the trap were tall weeds covering it. |

3. Results

3.1. Entomofauna of the Dumbrava Sibiului Forest

3.1.1. Carabidae Insect Species Identified in 2021

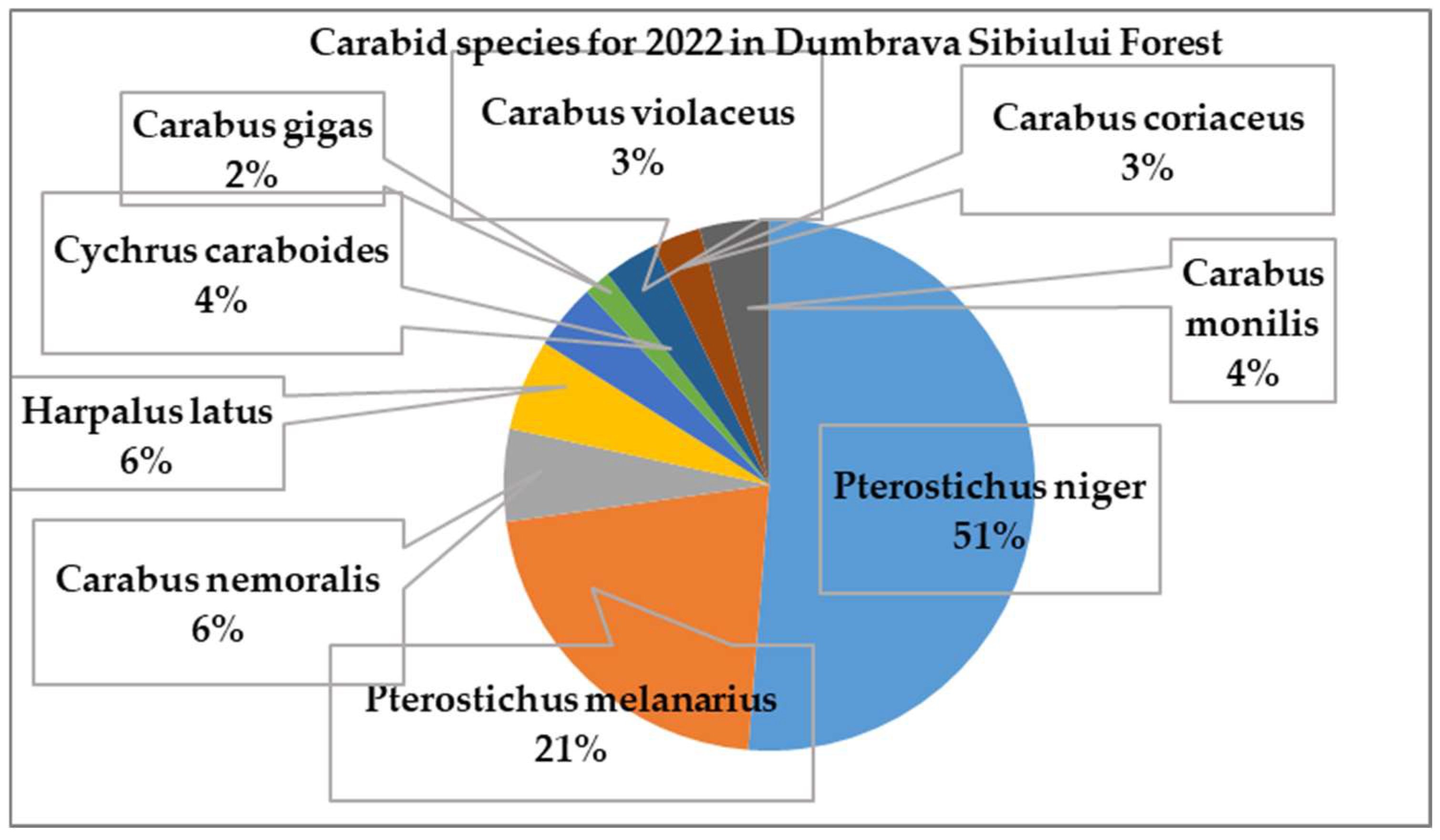

- Pterostichus niger Schaller, 1783 was the eudominant species,

- The dominant species were: Carabus ullrichii Germar, 1824, Cychrus caraboides Linnaeus, 1758 and Harpalus latus Linnaeus, 1758 and

- The subdominant species were Carabus variolosus Fab-Ricius, 1787, C. nemoralis O. F. Müller, 1764, C. coriaceus Linnaeus, 1758, Pterostichus melanarius Illiger, 1798, Platynus asimilis Paykull, 1790, Leistus spinibarbis Fabricus, 1775 (Figure 8).

3.1.2. Carabidae Insect Species Identified in 2022: 9 Species of Carabidae Have Been Identified in Dumbrava Forest

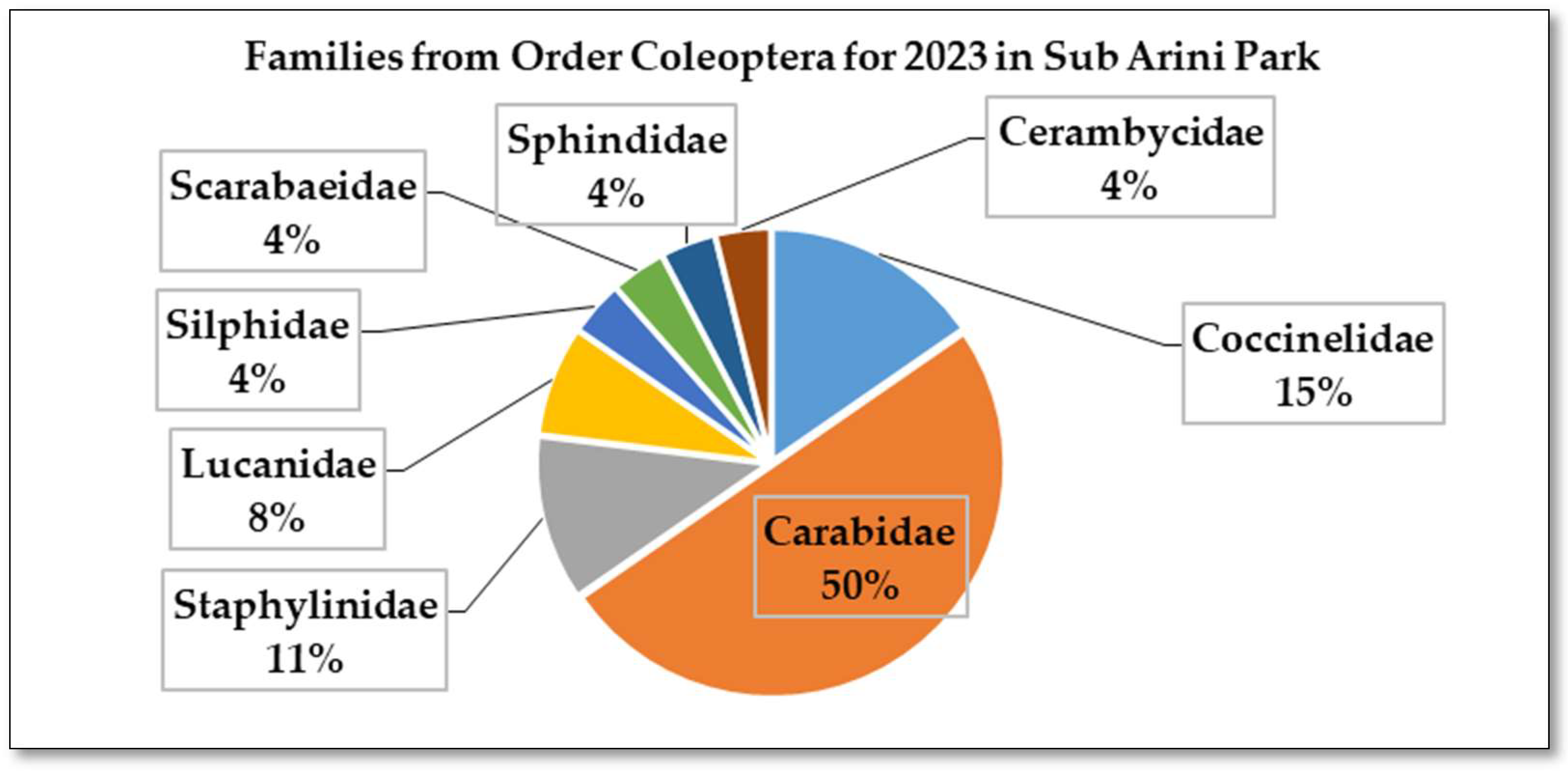

3.2. Coleoptera Found in the Sub Arini Park in 2023

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of All Species Collected at Both Locations

4.2. Weather Impact on Insect Populations

5. Conclusions

- 🗸

- first-order consumers (phytophagous species, feeding on fresh plant matter),

- 🗸

- second-order consumers (predatory species with molluscs, worms, and insects as their trophic base), and

- 🗸

- decomposers (detritivores species, feeding on plant detritus, coprophagous species, feeding on animal dung, scavenging species, feeding on corpses.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindenmayer, D.B., Franklin, J.F., Fischer, J., General management principles and a checklist of strategies to guide forest biodiversity conservation, Biol. Conserv. 2006, 131, 433-445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2006.02.019. [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.J., Abiem, I., Abu Salim, K., Aguilar, S., Allen, D., Alonso, A., Anderson-Teixeira, K., Andrade, A., Arellano, G., Ashton, P.S., et al. ForestGEO: Understanding forest diversity and dynamics through a global observatory network. Biol. Conserv, 2021, 253:108907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108907. [CrossRef]

- Isaia, G., Dragomir, I.M., Duduman, M.L., Diversity of Beetles Captured in Pitfall Traps in the S, inca Old-Growth Forest, Bras, ov County, ov, Romania: Forest Reserve versus Managed Forest, Forests, 2023, 14, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14010060. [CrossRef]

- Luick, R., Reif, A., Schneider, E., Grossmann, M., Fodor, E., Virgin forests in the heart of Europe. The importance, current situation and future of Romania's virgin forests. Bucov. For. 2021, 21, 105-126. https://doi.org/10.4316/bf.2021.009. [CrossRef]

- Olenici, N., Fodor, E., The diversity of saproxylic beetles' community from the Natural Reserve Voievodeasa Forest, North-Eastern Romania. Ann. For. Res. 2021, 64(1), 31-60. doi: 10.15287/afr.2021.2144. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, I.E., Gostin, I.N., Blidar, C.F., An overview of the mechanisms of action and administration technologies of the essential oils used as green insecticides. AgriEngineering, 2024, 6(2): 1195-1217. DOI: 10.3390/agriengineering6020068 (online: https://www.mdpi.com/2624-7402/6/2/68). [CrossRef]

- Montandon, A.L., Notes sur la faune entomologique de la Roumanie. Additions au catalog des Coléoptères. Buletinul Societății de Științe, Bucharest. 1908, 17 (1-2), 67-118.

- Ieniștea, M.Al., Contributions to the knowledge of the Coleoptera of the Godeanu Massif (Sibișelului Mountains, Southern Carpathians). Annales scientifiques de l' Unoversité de Jassy. 1936, XXII (1-4), 379-392.

- Panin, S., Family Scarabaeidae, Fauna of Romania, Insecta, Coleoptera, X(4), 315 p+36 pl., Editura Academiei R. P. Române, 1954 (In Romanian).

- Ieniștea, M.Al., Contribuții la cunoașterea fauna de coleoptere cavernicolous fauna of the RPR, Buletin Științific secția de Științe Biologice, Agronomice, Geologice și Geografice. 1955, 7(2), 410-426.

- Marcu, O., Contribuții la cunoașterea faunei coleopterelor coleopterelor Transilvaniei, Buletinul Universității V. Babeș-I. Bolyai Științele Naturii. 1957, 1, 527-544.

- Bobârnac, B., Marcu, O., Chimișliu, C., Sistematica land ecological researchs on Coleopterafauna in Subcarpathian zone of Oltenia Region during the last 70 years (1928-1998). Oltenia Studii și Comunicări Științele Naturii. 1999, 15, 83-95.

- Gîdei P., Popescu I.E., Guide to Coleoptera of Romania, Vol. I., Editura PIM Iași, 2012, p. 533.

- Popa, I., Sustr, V., Collembola (Hexapoda) from Mehedinți Mountains (SW Carpathians, Romania), with four new records for the Romanian fauna. Travaux de l'Institute de Spéologie "E. Racovitza", LV. 2016, 119-127. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/CollembolafromMehedintiMountainsRomaniawithfournewrecordsfortheromanianfauna.pdf. (accessed on November 30, 2023).

- Tóthmérész, B., Magura, T., Diversity and scalable diversity characteristics. European Carabidology. Proceedings of the 1st European meeting 2003. DIAS Report. 2005, 114, 353-368. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/DIAS_Diversity.pdf (accessed on November 30, 2023).

- Mouhoubi, D., Djenidi, R., Bounechada, M., Contribution to the study of entomofauna of the saline wetland of chott of Beida in Algeria. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies. 2018, 6(4), 317-323. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/Djenidi2018%20(2).pdf. (accessed on November 30, 2023).

- Mouhoubi, D., Djenidi, R., Bounechada, M., Contribution to the Study of Diversity, Distribution, and Abundance of Insect Fauna in Salt Wetlands of Setif Region, Algeria. International Journal of Zoology. 2019, Article ID 2128418, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2128418. [CrossRef]

- Gîdei P., Popescu I.E., Guide to Coleoptera of Romania, Vol. II., Editura PIM Iași, 2014, p. 531.

- Nitzu, E., Ilie, V., Contribution to the knowledge of edaphic and subterranean coleoptera from the Closani karstic area (Oltenia, Romania) with special references on the Mesovoid Shallow Substratum. Travaux de l'Institute de Spéologie "E. Racovitza" XLII. 2003, 159-168. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/Nitzu_Ilie.pdf (accessed on November 29, 2023).

- Smetana, A. (Eds.), Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera, Elateroidea, Derodontoidea, Bostrichoidea, Lymexyloidea, Cleroidea and Cucujoidea. Vol. 4. 2007, p.935.

- Nabozhenko, M.V, Löbl, I., Tribe Helopini Latreille, 1802. In Catalog of Palaearctic Coleoptera Vol. 5 Tenebrioidea (I. Löbl, A Smetana Eds.) Stenstrup, Apollo Books. 2008, 241-257.

- Nabozhenko, M.V., Keskin, B., Taxonomic review of the genus Helops Fabricius, 1775 (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) of Turkey. Caucasian Entomological Bulletin. 2017, 13(1), 41-49. DOI:10.23885/1814-3326-2017-13-1-41-49. [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, T., Dusánek, V., Meterlik, J., Kundrata, R., New distributional data on Elateroidea (Coleoptera: Elateridae, Eucnemidae and Omalisida) for Albania. Montenegro and Macedonia, Elateridariu. 2014, 8. 112-117. http://www.elateridae.com/elateridarium.

- Stan, M., Serafim, R., Maican, S., Data on the Beetle Fauna (Insecta: Coleoptera) in Frumoasa Site of Community Importance (ROSCI0058, Romania) and its Surroundings. Travaux du Muséum National dˈHistoire Naturelle "Grigore Antipa" București. 2016, 59(2), 129-159.

- Nitzu, E., Nae, A., Giurginca, A., Popa, I., Invertebrate communities from the mesovoid shallow substratum of the Carpatho-Euxinic area. Travaux de l'Institute de Spéologie "E. Racovitza", XLIX. 2010, 41-80. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/art03.pdf (accessed on November 30, 2023).

- Fleck, E., Die Coleopteren Rümaniens. Bull. Soc. Sci. Bucharest-Romania. State Printing Bucharest. 1904, 13 (3-4), 135.

- Petri, K., Siebenbürgens Käferfauna auf Grund ihrer Erforschung bis zum Jahre 1911. Siebenbürgischen verein für Naturwissenschaften zu Hermannstadt. 1912, p.376.

- Petri, C., Ergänzungen und Berichtgungen zur Käferfauna Siebenbürgens 1912. Verhandlungen und Mitteilungen des Siebenbbgürgischen Vereins für Naturwissensenschsften in Hermannstadt. 1926, 75-76 (1925-1926), 165-206.

- Cuzepan, G., Tăușan, I., The Genus Lucanus Scopoli, 1763 (Coleoptera:Lucanidae) in the Natural History Museum Collection of Sibiu (Romania). Brukenthal Acta Musei, 2013, 3, 451-460. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/CuzepanTausan2013.pdf. (accessed on January 12, 2024).

- Bouchard P., Smith A.B.T., Douglas H., Gimml M.L., Brunkel A.J., Kanda K., Biodiversity of Coleoptera: Science and Society. 2017, pp. 337-417, in Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society, Volume I, Second Edition. Robert G. Foottit and Peter H. Adler (Eds.), John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Published 2017 by John Wiley and Sons Ldt. DOI:10.1002/9781118945568.ch11. [CrossRef]

- Oettel, J.; Lapin, K., Linking Forest management and biodiversity indicators to strengthen sustainable forest management in Europe. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107275 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107275. [CrossRef]

- Grove, S.J., Saproxylic insect ecology and the sustainable management of forests. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 2002, 33, 1-23. https://doi. org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150507. [CrossRef]

- Stokland, J.N., Siitonen, J., Jonsson, B.G., Biodiversity in dead wood. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 2012, p.524. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139025843. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Hernández, A., Martínez-Falcón, A.P., Micó, E., Almendarez, S., Reyes-Castillo, P., Escobar, F., Diversity and deadwood-based interaction networks of saproxylic beetles in remnants of riparian cloud forest. PLoS ONE. 2019, 14(4), e0214920. https://doi.org/10.1371/.

- Siewers, J., Schirmel, J., Buchholz, S. The efficiency of pitfall traps as a method of sampling epigeal arthropods in litter rich forest habitats. Eur. J. Entomol. 2014, 111(1), 69-74. doi: 10.14411/eje.2014.008. [CrossRef]

- Radu, S., The ecological role of deadwood in natural forests. In Gafta D., Akeroyd J. (eds.), Nature Conservation: Concept and Practice. Springer. Berlin. 2007, 137-141. DOI:10.1007/978-3-540-47229-2_16. [CrossRef]

- Lassauce, A., Paillet, Y., Jactel, H., Bouget, C., Deadwood as a surrogate for forest biodiversity: metaanalysis of correlations between deadwood volume and species richness of saproxylic organisms. Ecological Indicators. 2011, 11, 1027-1039. https://doi.org.10.1016/j. ecolind. 2011.02.004. [CrossRef]

- Kunttu, P., Junninen, K., Kouki J., Dead wood as an indicator of forest naturalness: A comparison of methods. Forest Ecology and Management. 2015, 353, 30-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.05.017. [CrossRef]

- Tyr, V., Dvorák, L., Brouci (Coleoptera) Žihle a okolí.7.část. Omalisidae, Lycidae, Lampyridae, Cantharidae, Lymexylidae. Západočeské entomologologické listy. 2013, 4, 77-82. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/Tyr-Dvorak2013CanthZihle.pdf (accessed on November 30, 2023).

- Lovei, G.L., Sunderland, K.D., Ecology and behavior of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Annual Review Entomology. 1996, 41, 231-256. [CrossRef]

- Spence, J. R., Niemela, J. K. Sampling carabid assemblages with pitfall traps: the madness and the method. The Canadian Entomologist. 1994, 126, 881-894. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S., Jennions, M.D., Zalucki, M.P., Maron, M., Watson, J.E.M., Fuller, R.A., Protected areas and the future of insect conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2022, 38, 85-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2022.09.004. [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, Z.J., Król, W., Solarz, W. (eds.) Carpathi-an list of endangered species. WWF and Institute of Nature Conservation, Polish Academy of Sciences,Vienna-Krakow. 2003, p.64. https://archive.nationalredlist.org/files/2012/08/Carpathian-List-of-Endangered-Species-2003.pdf (accessed on November 30, 2023).

- Nitzu, E., An update of the Romanian fauna of Coleoptera: New records and notes on rare and little known species. Travaux de lˈ Institut de Spéologie Emil Racovitza LVI. 2017, 25-31.

- Nițu, E., Olenici, N., Popa, I., Nae, A., Biris, I.A., Soil and saproxylic species (Coleoptera, Collembola, Araneae) in primeval forests from the northern part of South-Easthern Carpathians. Ann. For. Res. 2009, 52, 27-53. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/Soil_and_saproxylic_species_Coleoptera_Collembola_.pdf (accessed on November 30, 2023).

- Stan, M., Rove beetles (Coleoptera, Staphylinidae) from Mehedinți Plateau Geological Park (Mehedinți County, Romania), Travaux du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle "Grigore Antipa", II. 2009, 233-247.

- Bartek, Z., Merenyi, Z., Illyes, Z., Gray, Z., Laszlo, P., Viktor, J., Brandt, S., Papp, L., Studies on the ecophysiology of Tuber aestivum populations in the CarpathoPannonian region, Österr. Z. Pilzk. 2010, 19, 221-226. https://www.zobodat.at/pdf/OestZPilz_19_0221-0226.pdf (accessed on November 30, 2023).

- Ariton, M., Data concetning the diversity of Scarabeoid beetles (Coleoptera, Scarabaeoidaea) from the Vânători Neamț Natural Park (Neamț Countru, Romania). Oltenia Studii și Comunicări Științele Naturii. 2011, 27, 109-114. http://188.241.48.170/cont/27_1/IZ10.Arinton.fin..pdf (accessed on November 30, 2023).

- Stoikou, M. G., Paraskevi KThe entomofauna on the leaves of two forest species, Fagus sylvatica and Corylus avelana, in Menoikio Mountain of Serres. Entomologia Hellenica. 2014, 23(2), 65-73. https://doi.org/10.12681/eh.11538. [CrossRef]

- Stancă-Moise, C., Study on the Carabidae fauna (Coleoptera, Carabidae) in a forest biota of oak in Sibiu (Romania). Scientific Papers Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development. 2016, 16(3), 321-324. https://managementjournal.usamv.ro/pdf/vol.16_3/Art43.pdf (accessed on November 30, 2023).

- Hurmuzachi, C., Catalogul Coleopterelor Coleopterelor culese from Romania. Bulletin de la Société des Sciences de Bucarest-Roumanie. 1901, 11(3), 336-374.

- Fleck, E., Die Coleopteren Rumäniens II. Bulletin of the Bucharest Science Society, 1904, 13 (5-6), 402-465.

- Stancă-Moise, C., Moise, G., Rotaru M., Vonica G., Sanislau D., Study on the Ecology, Biology and Ethology of the Invasive Species Corythucha arcuate Say, 1832 (Heteroptera: Tingidae), a Danger to Quercus spp. in the Climatic Conditions of the City of Sibiu, Romania, Forests. 2023, 14(6), 1278. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14061278. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, G.A., Belitz, M.W., Guralnick, R.P., Tingley, M.W., Standards and Best Practices for Monitoring and Benchmarking Insects, Ecol. Evol. 2021, 8, 1-18. doi:10.3389/fevo.2020.579193. [CrossRef]

- Gaoa, T., Nielsenb, A.B., Hedblom, M., Reviewing the strength of evidence of biodiversity indicators for forest ecosystems in Europe, Ecological Indicators, 2015, 57, 420-434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.05.028. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, L.M., Ivison, K., Enston, A., Garrett, D., Sadler J.P., Pritchard, J., MacKenzie, A.R., Hayward, S.A.L. A comparison of sampling methods and temporal patterns of arthropod abundance and diversity in a mature, temperate, Oak woodland, 2022, 103873, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2022.103873. [CrossRef]

- Calo´, L.O., Winckler-Caldeira, M.V., da Silva C.F., Camara, R., Castro K.C., de Lima S.S., Pereira M.G., de Aquino A.M., Epigeal fauna and edaphic properties as possible soil quality indicators in forest restoration areas in Espírito Santo, Brazil, Acta Oecologica. 2022, 117:103870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2022.103870. [CrossRef]

- Viciana, V., Svitok, M., Michalková E., Lukáčikd, I., Stašiovb, S., Influence of tree species and soil properties on ground beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae) communities. Acta Oecologica. 2018, 91, 120-126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2018.07.005. [CrossRef]

- Dudley N. (ed.), Guidelines for applying protected area management categories. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. x + 86 p. With Stolton S., Shadie P., Dudley N., 2013. IUCN WCPA Best practice guidance on ecognizing protected areas and assigning management categories and governance types, Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 21, Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. 2008. x, 86 p. +iv, 31 p.

- Varvara, M., Diversity and the main ecological requirements of the epigeic species of Carabidae (Coleoptera, Carabidae) from two types forest ecosystems in Suceava County (Moldavia). Entomologica Romanica. 2005, 10, 81-88. https://entomologica-romanica.reviste.ubbcluj.ro/10_2005/ER10200510_Varvara.pdf (accessed on November 27, 2023).

- Bacal, S., Observation on the Coleopteran (Insecta: Coleoptera) fauna from Codrii Tigheciului. Oltenia Studii și Comunicări Științele Naturii, 2006, 22, 160-163. http://olteniastudiisicomunicaristiintelenaturii.ro/cont/22/IZ10-Bacal.pdf (accessed on November 27, 2023).

- Babam, E., The saproxylic Coleoptera as indicators of forests of European importance from central Moldavian Plateau. Oltenia Studii și Comunicări Științele Naturii. 2008, 24, 121-124. http://olteniastudiisicomunicaristiintelenaturii.ro/cont/24/IZ12-Baban.pdf (accessed on November 27, 2023).

- Schmidl, J.; Sausage, C.; Bussler, H. Red list and complete list of varieties of the "Diversicornia" (Coleoptera) of Germany. In Red List of Endangered Animals, Plants and Fungi of Germany, Volume 5: Invertebrates (Part 3); Nature Protection and Biodiversity; Ries, M., Balzer, S., Gruttke, H., Haupt, H., Hofbauer, N., Ludwig, G., Matzke-Hajek, G., Eds; Agriculture Publisher: Münster, Germany, 2021; Volume 70, pp. 99-124.

- Siewers, J., Schirmel, J., Buchholz, S. The efficiency of pitfall traps as a method of sampling epigeal arthropods in litter rich forest habitats. Eur. J. Entomol. 2014, 111(1), 69-74. doi: 10.14411/eje.2014.008. [CrossRef]

- Yeates D.K., Hatvey M.S., Austin A.D., New estimates for terrestrial arthopod species-richness in Australia. Records of the South Australian Museum, Monograph Series. 2003, 7, 231-241. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/Yeatesetal2003.pdf (accessed on November 30, 2023).

- Marske, K.A., Ivie, M.A, Beetle Fauna of the United States and Canada. The Coleopterists Bulletin. 2003, 57(4), 495-503. DOI:10.1649/663.

- Klausnitzer B., Käfer. Nikol Verlag. 2002, p. 242.

- Engelmann, H.D., Zur Dominanzklassifizierung von Bodenarthropoden, For the dominance classification of soil arthropods. Pedobiologia. 1978, 18, 378-380.

- Stugren, B., The basics of general ecology. Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică, Bucharest. 1982, p.435.

- Barkman, J.J., Moravec, J., Rauschert, S. Code of phytosociological nomenclature. 2nd edn. Vegetatio. 1986, 67, 145-195.

- Dragulescu C., Cormoflora of Sibiu County, Pelecanus Publishing House Brasov, 2003, 533p.

- Schneider-Binder E., Forests of the Sibiului depression and marginal hills I, St. and com. Muz. Brukenthal Sibiu, Șt. Nat. 1973, 18, 71-108.

- Stancă-Moise, C., The presence of species Morimus asper funereus Mulsant, 1862 (long-horned beetle) Coleoptera: Cerambycidae in a forest of oak conditions, Scientific Papers Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development. 2015, 15(4), 315-318. https://managementjournal.usamv.ro/pdf/vol.15_4/Art47.pdf (accessed on January 12, 2024).

- Zicha O. (ed.), 1999-2021. BioLib. http://www.biolib.cz.

- Koch, K., Die Käfer Mitteleuropas. Ökologie. The beetles of Central Europe. Ecology. Band 1. Goecke & Evers. Krefeld. 1989, p. 440.

- Koch, K., Die Käfer Mitteleuropas. Ökologie. The beetles of Central Europe. Ecology. Band 3. Goecke & Evers. Krefeld. 1992, p.389.

- Schmidl, J., Bussler, H., Ökologische Gilden xylobionter Käfer Deutschlands. Einsatz in der landschaftsökologischen Praxis ein Bearbeitungsstandard. Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung. 2004, 36(7), 202-218. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/Schmidl_Bussler_NuL07-04.pdf (accessed on January 12, 2024).

- Lobl, I., Smetana, A. (Eds.), Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera, Archostemata, Myxophaga, Adephaga, Vol. 1., 819 p., 2003, LOBL, I.,.

- Lobl, I., Smetana, A., (Eds.), Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera, Tenebrioidea, Vol. 5, 2008, p. 670.

- Lobl, I., Lobl, D. (Eds.), Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera, Hydrophiloidea, Staphylinoidea, Vol. 2, 2015, p. 1702. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/2015Lackner-2.pdf (accessed on January 12, 2024).

- Lobl, I., Lobl, D., (Eds.) Catalog of Palaearctic Coleoptera, Scarabaeoidea, Scirtoidea, Dascilloidea, Buprestoidea and Byrrhoidea, Vol. 3, 2016, p. 984. file:///C://C:/Users/Cristina/Downloads/114-122-CatPalCol2006.pdf. (accessed on January 12, 2024).

- Nieto, A., Alexander, K.N.A., European red list of saproxylic beetles. Publications Office of the European Union. Luxembourg. 2010, p. 44. https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/RL-4-023.pdf (accessed on January 12, 2024).

- Murariu, D, Maican, S. (Eds), The Red Book of Invertebrates of Romania. ThePublishing House of the Romanian Academy. Bucharest. 2021, p. 451.

- Summary monitoring guide for habitats of community interest - scrublands, peat bogs and fens, cliffs, forests. 2005, p. 103.

- Dajoz, R., Les insectes et la forêt. Rôle et diversité des insectes dans le milieu forestier. Lavoisier Tec Doc, Paris. 1998, p. 594.

- Dajoz, R., Morphological study of the Morimus (Coleoptera, Cerambycydae) of the European fauna. LˈEntomologiste, 1976, 67(1-3), 212-231.

- Directive 97/62/EC of 27.10.1997. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A31997L0062 (accessed on January 12, 2024).

- Stichmann, W., Faune d'Europe, Vigot, Paris, France. 1999, p.448.

- Magurran, A.E., Measuring biological diversity. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2004, p. 256. http://www.bio-nica.info/Biblioteca/Magurran2004MeasuringBiological.pdf (accessed on January 12, 2024).

- Magurran, A.E., Species abundance distributions: pattern or process. Functional Ecology. 2005, 19, 177-181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0269-8463.2005.00930.x. [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E., Diversity over time. Folia Geobotanica. 2008, 43, 319-327. https://doi.org/10.1007/.

- Nitzu, E., Eco-faunistic studies on edaphic coleopteran associations in the Sic-Păstăraia area (Transylvanian Plain). Annals ICAS. 2007, 50, 153-167. https://editurasilvica.ro/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/50-1-2007-153-168-Studii-eco-faunistice-asupra-asociatiilor-de-coleoptere-edafice-din-zona-Sic-Pastaraia-Campia-Transilvaniei.pdf.

- Matern, A., Drees, C., Kleinwächter, M., Assmann, T., Habitat modeling for the conservation of the rare ground beetle species Carabus variolosus (Coleoptera, Carabidae) in the riparian zones of headwaters. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 136, 618-627. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2007.01.006. [CrossRef]

- Lie, P., Allgemeine betrachungen mit Bezug auf die Carabofauna des Retezatgebierges (Rumänien, Sűdkarpaten). Ber. Kr. Nűrnberg. Ent. Galathea. 1997, 13(4), 139-144.

- Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora (Habitats Directive) Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/legislation/habitatsdirective/index_en.htm (accessed on January 12, 2024).

- Panin, S., Family Carabidae (genus Cychrus Fabricius and genus Carabus Linne), Fauna RPR, Insecta. 1955. X(2), 148 p. (In Romanian).

- Săvulescu, N., The Forests of South-West Dobrogea, little known monuments of nature. Ocrotirea Naturii. 1964, 8(2), 257-276.

- Stancă-Moise, C.. Observations of the Lucanus cervus Linnaeus, 1758 (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) species in the Sibiu and Hunedoara counties in the conditions of 2020. Olteniei Museum Craiova. Oltenia. Studies and communications. Natural Sciences. 2021, 37(1), 76-82. http://olteniastudiisicomunicaristiintelenaturii.ro/cont/37_1/III.%20ANIMAL%20BIOLOGY%20III.a.%20INVERTEBRATES%20VARIOUS/12%20Stanca-Moise.pdf (accessed on January 12, 2024).

- Ruicănescu, A., Contributions to the study of coleopteran communities in Cheile Turzii. Entomological Information Bulletin Romanian Lepidopterological Society Cluj-Napoca. 1992, 3(4), 9-15.

- Koivula, M.J., Useful model organisms, indicators, or both? Ground beetles (Coloptera, Carabidae) reflecting environmental conditions. ZooKeys. 2011, 100, 287-317. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.100.1533. [CrossRef]

- Brygadyrenko, V., Evaluation of ecological niches of abundant species of Poecilus and Pterostichus (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in forests of steppe zone of Ukraine. Entomol. Fenn., 2016, 27, 81-100. https://doi.org/10.33338/ef.84662. [CrossRef]

- Ponnel, P., Coleoptera of the Massif des Maures and the Permian Peripheral Depression. Faune de Provence. 1993, 5-23.

- Schulze, E.D., Effects of forest management on biodiversity in temperate deciduous forests: An overview based on Central European beech forests. J. Nat. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 43, 213-226. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2017.08.001. [CrossRef]

- Błońska, E. , Bednarz, B., Kacprzyk, M., Piaszczyk, W., Lasota J. Effect of scots pine forest management on soil properties and carabid beetle occurrence under post-fire environmental conditions- a case study from Central Europe. Forest Ecosystems, 2020, 7, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-020-00240-5. [CrossRef]

- Kazerani, F., Farashiani, M.E., Sagheb-Talebi, K., Thorn, S., Forest management alters alpha, beta, and gamma diversity of saproxylic flies (Brachycera) in the Hyrcanian forests. Iran. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 496 (2), 119444. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119444. [CrossRef]

- McGeoch, M.A. The selection, testing and application of terrestrial insects as bioindicators. Biological Revue. 1998, 73, 181-201.

- McGeoch, M.A., Schroeder, M., Ekbom, B., Larsson, S., Saproxylic beetle diversity in a managed boreal forest: Importance of stand characteristics and forestry conservation measures. Divers. Distrib. 2007, 13, 418-429. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2007.00350.x. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, P., Fortin, D., Hébert, C., Beetle diversity in a matrix of old-growth boreal forest: Influence of habitat heterogeneity at multiple scales. Ecography, 2009, 32, 423-432. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05671.x. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.S., Gage, S.H., Spence, J.R. Habitats and management associated with common ground beetles (Coleoptera:Carabidae) in a Michigan Aricultural landscape. Environmental Entomology, 1997, 26, 519-527. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/26.3.519. [CrossRef]

- Worell E., Contributions to the knowledge of the fauna of coleoptera and lepidoptera in Transylvania, especially in the surroundings of Sibiu. Scientific Bulletin, Section of Biological, Agronomical, Geological and Geographical Sciences. 1951, 3(3), 533-543.

- Byk, A., Semkiw, P., Habitat preferences of the forest dung beetle Anoplotrupes stercorosus (Scriba, 1791)(Coleoptera: Geotrupidae) in the Białowieza Forest. Acta Sci. Pol. Silvarum Colendarum Ratio Et Ind. Lignaria. 2010, 9, 17-28. file:///C:/ /Users/Cristina/Downloads/Anoplotruprupessesstercorosus2010.pdf (accessed on January 29, 2024).

- Esh, M.; Oxbrough, A., Macrohabitat associations and phenology of carrion beetles (Coleoptera: Silphidae, Leiodidae: Cholevinae). J. Insect Conserv, 2021, 25, 123-136. 10.1007/s10841-020-00278-4. [CrossRef]

- https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/ (accessed on February 4, 2024).

| FOREST DUMBRAVA 2021-2022 |

SUB-ARINI PARK 2023 |

|---|---|

| Research place | |

|

|

| Monitoring area | |

| Inside the forest at an altitude of 510 m near the county road 106A, which connects Sibiu to Rășinari. This configuration delimited an area of 452.39 m² inside the forest. |

The land was divided into six collection areas considering both the dendrological criteria and the topography of the site, with a length varying between 250 and 600 meters, depending on the location between the dikes. The monitoring area covered 21.65 hectares. |

| Collection periods | |

| In 2021, 16 field trips were conducted over a collection period of 156 days (between March and August). In 2022, 19 field trips were carried out over a collection period of 178 days (from the beginning of April to the end of September) at the same site. |

In 202325 collection trips = 184 calendar days sample collection started in April and lasted until November (7 months), covering all 4 seasons. |

| Collection methods use | |

| Soil traps were used as a collection method to collect mainly edaphic insects, large and mobile species, mainly predatory and predatory species. The traps used were hand-made from PET containers of two different sizes, fitted together (Figure 3, Figure 7, Figure 8). A total of 41 identical traps were constructed (24 Dumbrava and 17 Arini). These were buried in the ground on stones to facilitate water run-off and hidden so as not to disturb soil fauna. A PVC foil funnel was installed at the mouth of each protection pot. Possible trapping surface area of a trap: 226.08 cm². | |

| A set of 12 traps (labeled C1-C12) were installed (each year) around the circumference of a circle with a radius of 12 m (Figure 3). | The land was divided into six collection areas, ranging in length from 250 to 600 meters, depending on the location between the dikes on which 17 traps were randomly distributed (Figure 7). |

| Flora | |

| Two phytocenological surveys were conducted at the same station for both 2021 and 2022. The surveyed plots belong vegetatively to the association Querco robori - Carpinetum Soo et Pocs (1931) 1957 subass. dacicum var. with Asperula odorata. | It hosts a rich diversity of trees of significant scientific and aesthetic importance. The first inventories were carried out in 1965-1966 by M.I Dollu (80 species of trees and shrubs) and C. Drăgulescu (61 tree species) [71]. |

| Method of analysis | |

| The analysis method used was the calculation of the statistical indices Constant (C), Dominance (D) and Ecological Significance (W). | |

| Results | |

|

26 species (9 families) from 2,118 samples |

| In total, 12 beetle families were identified covering 46 coleopteran species out of 5,008 individuals. Across all three years in both ecosystems, the family Carabidae (Insecta: Coleoptera: Carabidae) has the highest abundance, dominance, constancy with 23 species identified. | |

| No. | Tree species | dominance |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Quercus robur L., 1753 (mature oak, over 100 years old) |

7 (from 7 vegetative surveys) |

| 2 | Quercus petraea L., 1784 | 5 |

| 3 | Tilia sp. | 4 |

| 4 | Carpinus betulus L., 1753 | 7 |

| 5 | Acer campestre L., 1753 | 4 |

| Collection zone | Length (m)/ Area (ha) |

Tree species | Number of traps set |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 450/8 | Ginko biloba, Betula verrucosa, Juglans regia, J. nigra, J. nigra, Populus alba, Platanus aurifolia, Acer platanoides, Quercus robur and Fagus sylvatica. Conifers, including native and exotic species, are well represented here, with species such as Tsuga canadensis, Taxus baccata, Abies alba and Juniperus virginiana. | 8,9,17 |

| II | 600/8 | Populus nigra, Morus alba, Clematis vitalba, Cerasium avium, Pirus sativa, Crataegus monogyna, Platanus acerifolia and Acer platanoides | 6,7,16 |

| III | 250/10 | Salix alba, Cerasum avium, Prunus spinosa, Platanus acerifolia, Robinia pseudoacacia and Acer platanoides | 4,5 |

| IV | 350/7 | Pinus silvestris and meadow vegetation | 1,2,3 |

| V | 250/5 | Quercus robur and Scirpus sp. | 13,14,15 |

| VI | 700/14 | Quercus sp., Scirpus sp. and Phragmites sp. | 10,11,12 |

| No. | 2021 | % | No. | 2022 | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carabidae | 85.89% | 1 | Carabidae | 85.16% |

| 2 | Silphidae | 4.53% | 2 | Tenebrionidae | 3.61% |

| 3 | Scarabaeidae | 3.07% | 3 | Geotrupidae | 3.22% |

| 4 | Sphindidae | 2.34% | 4 | Staphylinidae | 2.43% |

| 5 | Elateridae | 1.54% | 5 | Sphindidae | 1.84% |

| 6 | Staphylinidae | 1.83% | 6 | Silphidae | 1.44% |

| 7 | Curculionidae | 0.8% | 7 | Scarabaeidae | 1.51% |

|

Total: 7 families (1,367 sp.) |

8 | Cerambycidae | 0.79% | ||

| Total: 8 families (1,523 sp.) | |||||

| No | Family | Species | Dumbrava Forest | Constancy (C) | Class (%) | Dominance (D) | Class (%) | Dzuba Ecological significance (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

I. Carabidae |

Carabus violaceus Linnaeus, 1758 | 27 | C2 | 11.57 | 2 | D2 | W5 |

| 2 | Carabus (Procustes) coriaceus L., 1758 | 34 | C1 | 1.04 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 3 | Carabus gigas Creutzer, 1799 | 57 | C1 | 1.97 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 4 | Carabus monilis scheidleri, Panzer, 1799 | 62 | C1 | 2.15 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 5 | Carabus nemoralis, O. F. Müller, 1764 | 74 | C1 | 2.56 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 6 | Carabus ullrichii, Germar, 1824 | 63 | C1 | 2.18 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 7 | Carabus variolosus Fabricius, 1787 | 43 | C1 | 1.49 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 8 | Cychrus caraboides Linnaeus, 1758 | 61 | C1 | 2.11 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 9 | Harpalus latus, Linnaeus, 1758 | 79 | C1 | 2.73 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 10 | Leistus (Pogonophorus) spinibarbis, Fabricius, 1775 | 95 | C1 | 3.46 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 11 | Pterostichus (Bothriopterus) oblongopunctatus Fabricius, 1787 | 156 | C1 | 5.40 | 2 | D2 | W4 | |

| 12 | Pterostichus niger Schaller, 1783 | 941 | C3 | 32.56 | 3 | D3 | W6 | |

| 13 | Pterostichus melanarius, Illiger, 1798 | 371 | C2 | 12.84 | 2 | D2 | W5 | |

| 14 | II. Cerambycidae | Rhagium sycophanta Schrank, 1781 | 2 | C1 | 0.07 | + | D1 | W1 |

| 15 | Morimus funereus Mulsat, 1863 | 2 | C1 | 0.07 | + | D1 | W1 | |

| 16 | III.Curculionidae | Pissodes pini Linnaeus, 1758 | 49 | C1 | 1.70 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 17 | IV. Elateridae | Ampedus sanguineus Linnaeus, 1758 | 85 | C1 | 2.94 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 18 | V. Scarabaeidae | Protaetia marmorata Fabricius, 1792 | 20 | C1 | 1.82 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 19 |

VI. Silphidae |

Nicrophorus vespillo Linnaeus, 1758 | 126 | C1 | 4.36 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 20 | Nicrophorus germanicus Linnaeus, 1758 | 157 | C1 | 5.43 | 2 | D2 | W4 | |

| 21 | Oiceoptoma thoracica Linnaeus, 1758 | 132 | C1 | 4.57 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 22 | Necrodes littoralis Linnaeus, 1758 | 91 | C1 | 3.15 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 23 | VII.Staphylinidae | Ocypus (Staphylinus) olens Műller, 1764 | 10 | C1 | 2.20 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 24 | VIII. Sphindidae | Sphindus dubius Gyllenhal, 1808 | 153 | C1 | 5.29 | 2 | D2 | W4 |

| Total | 2890 |

| Family | Species | Status/characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Carabidae |

Carabus (Procustes) coriaceus Linnaeus, 1758 |

Important limiting factor for their populations at the site. |

|

|

Carabus (Procerus) gigas Creutzer, 1799 | ||||

| Carabus (Morphocarabus) scheidleri Panzer, 1799 |

Characteristic of oak and gorgonian ecosystems, being a predatory species that feeds on larvae of Lymantria sp. |

|||

| C. nemoralis O. F. Müller, 1764 | ||||

| Carabus (Hygrocarabus) variolosus Fabricius, 1787 | Protection status is given by Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC (Annex II); OUG 57/2007 (Annex 3, 4A) considered endangered in Europe - rare, protected species. | |||

| Carabus (Megodontus) violaceus Linnaus, 1758 | ||||

|

2 |

Cerambycidae |

Rhagium (Megarhagium) sycophanta Schrank, 1781 |

Included in the IUCN European Red Lists [63,82]. is a polyphagous species, common in deciduous forests, preferring oaks, flowering under the bark of fallen trees or under stumps. Adults are active from April to July [78]. Specimens were collected from traps placed in oaks and under flowering shrubs. |

|

|

Morimus funereus Mulsat, 1863 |

Present in Romanian deciduous forests [83]. Previously reported in Dumbrava Forest in 2015 [73]. Saproxylic species, preferring beech and oak [85]. Adults emerge in spring and summer. Larvae develop in thick roots, rotting stumps, wood piles and fallen trunks [86]. Vulnerable species with protected status under Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC (Annex II); OUG 57/2007 (Annex 3, 4A) Vulnerable under criteria A1c. The Red List [87,88]. |

|||

| 3 | Curculionidae | Pissodes pini Linnaeus, 1758 | Collected in 2022 as an accidental species in the forest. | |

|

4 |

Geotrupidae |

Geotrupes stercorarius Scriba, 1791 |

Is nourished by animal excrements, especially sheep excrements, which transit through the forest towards Rășinari commune, thus helping to ensure soil fertility and organo-mineral balance. | |

| 5 | Elateridae | Ampedus sanguineus Linnaeus, 1758 | Common beetle species caught in small numbers. | |

|

6 |

Silphidae |

Oiceoptoma thoracicum Linnaeus, 1758 |

These species are found in woodland habitats and feed on animal droppings [89]. |

|

| Nicrophorus germanicus Linnaeus, 1758 | ||||

| Necrodes littoralis Linnaeus, 1758 | ||||

| Nicrophorus vespillo Linnaeus, 1758 | ||||

| 7 | Staphylinidae | Ocypus (Ocypus) olens Müller, 1764 | Have a varied trophic diet: coprophagous, necrophagous and in some cases they also feed on dried fungi. This trophic regime emphasizes the important role of these species as health biotopes of the Dumbrava Forest [87,88]. | |

| Staphylinus caesareus Cederhjelm, 1798 | ||||

|

Family |

Species |

Sub Arini Park | Constancy (C) | Class (%) | Dominance (D) | Class (%) | Dzuba Ecological significance (W) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

I. Carabidae |

Bembidion illigeri Latreille, 1802 | 43 | C1 | 2.03 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 2 | Bradycellus ruficollis Stephens, 1828 | 50 | C1 | 2.36 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 3 | Carabus violaceus Linnaeus, 1758 | 551 | C2 | 11.57 | 2 | D2 | W5 | |

| 4 | Carabus (Procustes) coriaceus L., 1758 | 18 | C1 | 1.04 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 5 | Harpalus aeneus Fabricius, 1775 | 58 | C1 | 2.74 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 6 | Harpalus rubripes Dufischmid, 1812 | 46 | C1 | 2.17 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 7 | Harpalus rufipes Degeer, 1774 | 65 | C1 | 3.07 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 8 | Lebia chlorocephala Hoffkan, 1803 | 47 | C1 | 2.22 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 9 | Leistus ferrugineus Linnaeus, 1758 | 73 | C1 | 3.45 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 10 | Nebria picicornis Fabricius, 1775, 1801 | 69 | C1 | 3.26 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 11 | Platynus assimilis, Paykull, 1790 | 77 | C1 | 3.64 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 12 | Pterostichus madidus Fabricius, 1775 | 48 | C1 | 2.27 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 13 | II.Cerambycidae | Cerambyx pig Linnaeus, 1758 | 2 | C1 | 0.09 | + | D1 | W1 |

| 14 |

III. Coccinellidae |

Coccinella septempunctata L., 1758 | 94 | C1 | 4.44 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 15 | Harmonia axyridis Pallas, 1773 | 82 | C1 | 3.87 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 16 | Stethorus punctillum Weise, 1891 | 32 | C1 | 1.51 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 17 |

VI. Lucanidae |

Dorcus parallelipipedus L., 1758 | 3 | C1 | 0.14 | + | D1 | W1 |

| 18 | Lucanus cervus Linnaeus, 1758 | 2 | C1 | 0.09 | + | D1 | W1 | |

| 19 | V. Scarabaeidae | Protaetia marmorata Fabricius, 1792 | 71 | C1 | 1.82 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 20 | VI. Geotrupidae | Geotrupes stercorosus Scriba, 1791 | 71 | C1 | 3.35 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 21 | VII. Silphidae | Phosphuga (Silpha) atrata L., 1758 | 90 | C1 | 4.25 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 22 | VIII. Staphylinidae | Staphylinus caesareus Cederh., 1798 | 133 | C1 | 6.28 | 2 | D2 | W4 |

| 23 | Ocypus (Staphylinus) olens M., 1764 | 100 | C1 | 2.20 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 24 | Xantholins linearis Olivier, 1795 | 119 | C1 | 5.62 | 2 | D2 | W4 | |

| 25 | XI.Tenebrionidae | Stenomax aeneus Scopoli, 1763 | 174 | C1 | 8.22 | 2 | D2 | W4 |

| Total | 2118 |

| No. | Family | Species | Status / Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Coccinelidae |

Coccinella septempunctata Linnaeus, 1758 | The presence of these zoophagous species is related to the food source represented by aphids found on Sambucus nigra shrubs inside the Sub Arini Park and other low plants or trees. |

| Harmonia axyridis Pallas, 1773 | |||

| Stethorus punctillum Weise, 1891. | |||

|

2 |

Cerambycidae |

Cerambyx pig Linnaeus, 1758 |

species protected under the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC present in natural, semi-natural forests and in urban parks with old oaks, it develops in 3-5 years on Quercus sp. species from dead wood of living trees. As conservation measures for this species, it is recommended to secure in time and space the habitat of the species, which is represented by old oaks [8]. |

|

3 |

Lucanidae |

Lucanus cervus Linnaeus, 1758 |

species protected under Council of Europe Directive 92/43/EEC [95,96,97,98]. The presence of oak trees in Arini creates a favorable habitat. For this reason, it was accidentally observed in the park, but has also been reported in other habitats in Romania [99] |

| Dorcus parallelipipedus Linnaeus, 1758 | |||

| 4 | Scarabaeidae | Protaetia marmorata Fabricius, 1792 | very rare species, protected in Europe [82]. |

|

5 |

Carabidae |

Carabus violaceus Linnaeus, 1758 |

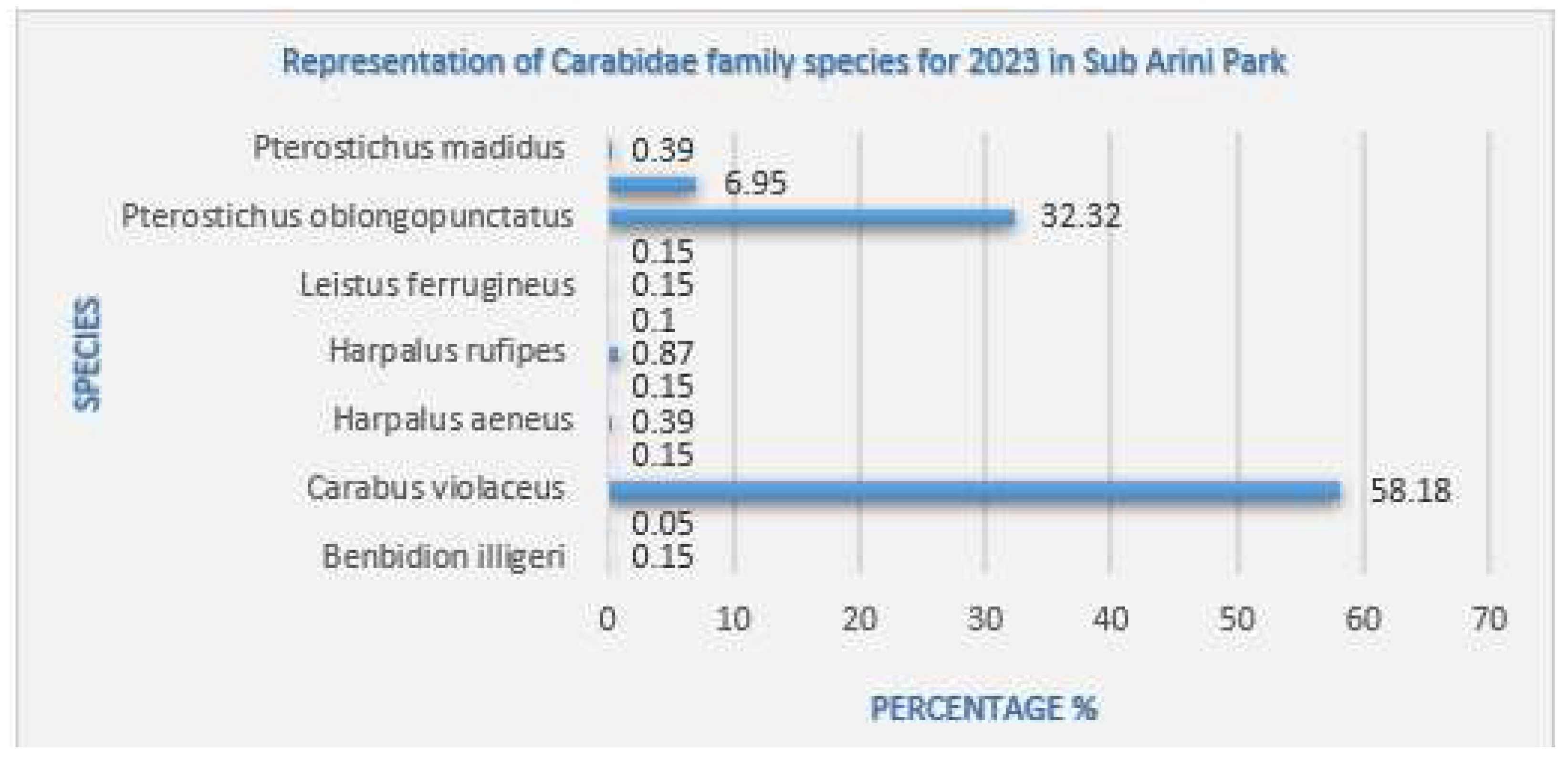

the dominant predatory species in shaded areas with shrubby vegetation from April to November. Present in all collection areas, with 1181 specimens (58.18% of the total), it was found in all traps near alleyways where food sources were also found, with most specimens being caught. during the period when the snail population was increasing. They overwinter as larvae which were identified as of October 1, 2023. |

|

6 |

Carabidae |

Pterostichus oblongopunctatus Fabricius, 1787 |

Predatory species codominant with Carabus violaceus Linnaeus, 1758 in the summer season, common in forest habitats, present in all sectors and traps, with 656 individuals (32.32%). |

|

7 |

Carabidae |

Pterostichus niger Schaller, 1783 |

predatory species present in Zones II, III and IV with 141 individuals (6.95%), feeding on oligochaetes, molluscs and insect larvae. |

|

8 |

Tenebrioninae |

Stenomax aeneus Scopoli, 1763 |

The species is a large primary decomposer that feeds on bird and mammal carcasses, helping to maintain the organic-mineral balance of the forest floor. |

| No | Family | Species | Dumbrava Forest (2021-2022) |

Sub Arini Park (2023) |

Constancy (C) | Class (%) | Dominance (D) | Class (%) | Dzuba Ecological significance (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

I. Carabidae |

Bembidion illigeri Latreille, 1802 | - | 43 | C1 | 2.03 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 2 | Bradycellus ruficollis Stephens, 1828 | - | 50 | C1 | 2.36 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 3 | Carabus violaceus Linnaeus, 1758 | 27 | 551 | C2 | 11.57 | 2 | D2 | W5 | |

| 4 | Carabus (Procustes) coriaceus Linnaeus, 1758 | 34 | 18 | C1 | 1.04 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 5 | Carabus gigas Creutzer, 1799 | 57 | - | C1 | 1.97 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 6 | Carabus monilis scheidleri, Panzer, 1799 | 62 | - | C1 | 2.15 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 7 | Carabus nemoralis, O. F. Müller, 1764 | 74 | - | C1 | 2.56 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 8 | Carabus ullrichii, Germar, 1824 | 63 | - | C1 | 2.18 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 9 | Carabus variolosus Fabricius, 1787 | 43 | - | C1 | 1.49 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 10 | Cychrus caraboides Linnaeus, 1758 | 61 | - | C1 | 2.11 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 11 | Harpalus aeneus Fabricius, 1775 | - | 58 | C1 | 2.74 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 12 | Harpalus latus, Linnaeus, 1758 | 79 | - | C1 | 2.73 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 13 | Harpalus rubripes Dufischmid, 1812 | - | 46 | C1 | 2.17 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 14 | Harpalus rufipes Degeer, 1774 | - | 65 | C1 | 3.07 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 15 | Lebia chlorocephala Hoffkan, 1803 | - | 47 | C1 | 2.22 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 16 | Leistus ferrugineus Linnaeus, 1758 | - | 73 | C1 | 3.45 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 17 | Leistus (Pogonophorus) spinibarbis, Fabr., 1775 | 95 | - | C1 | 3.46 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 18 | Nebria picicornis Fabricius, 1775, 1801 | - | 69 | C1 | 3.26 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 19 | Platynus assimilis, Paykull, 1790 | - | 77 | C1 | 3.64 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 20 | Pterostichus (B..) oblongopunctatus Fabr, 1787 | 156 | - | C1 | 5.40 | 2 | D2 | W4 | |

| 21 | Pterostichus niger Schaller, 1783 | 941 | - | C3 | 32.56 | 3 | D3 | W6 | |

| 22 | Pterostichus madidus Fabricius, 1775 | - | 48 | C1 | 2.27 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 23 | Pterostichus melanarius, Illiger, 1798 | 371 | - | C2 | 12.84 | 2 | D2 | W5 | |

| 24 | II. Cerambycidae | Cerambyx pig Linnaeus, 1758 | - | 2 | C1 | 0.09 | + | D1 | W1 |

| 25 | Rhagium sycophanta Schrank, 1781 | 2 | - | C1 | 0.07 | + | D1 | W1 | |

| 26 | Morimus funereus Mulsat, 1863 | 2 | - | C1 | 0.07 | + | D1 | W1 | |

| 27 |

III. Coccinellidae |

Coccinella septempunctata Linnaeus, 1758 | - | 94 | C1 | 4.44 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 28 | Harmonia axyridis Pallas, 1773 | - | 82 | C1 | 3.87 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 30 | Stethorus punctillum Weise, 1891 | - | 32 | C1 | 1.51 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 31 | IV. Curculionidae | Pissodes pini Linnaeus, 1758 | 49 | - | C1 | 1.70 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 32 | V. Elateridae | Ampedus sanguineus Linnaeus, 1758 | 85 | - | C1 | 2.94 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 33 | VI. Lucanidae | Dorcus parallelipipedus Linnaeus, 1758 | - | 3 | C1 | 0.14 | + | D1 | W1 |

| 34 | Lucanus cervus Linnaeus, 1758 | - | 2 | C1 | 0.09 | + | D1 | W1 | |

| 35 | VII. Scarabaeidae | Protaetia marmorata Fabricius, 1792 | 20 | 71 | C1 | 1.82 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| VIII. Geotrupidae | Geotrupes stercorosus Scriba, 1791 | - | 71 | C1 | 3.35 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 37 |

IX. Silphidae |

Phosphuga (Silpha) atrata Linnaeus, 1758 | - | 90 | C1 | 4.25 | 1 | D2 | W3 |

| 38 | Nicrophorus vespillo Linnaeus, 1758 | 126 | - | C1 | 4.36 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 39 | Nicrophorus germanicus Linnaeus, 1758 | 157 | - | C1 | 5.43 | 2 | D2 | W4 | |

| 40 | Oiceoptoma thoracica Linnaeus, 1758 | 132 | - | C1 | 4.57 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 41 | Necrodes littoralis Linnaeus, 1758 | 91 | - | C1 | 3.15 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 42 |

X. Staphylinidae |

Staphylinus caesareus Cederhjelm, 1798 | - | 133 | C1 | 6.28 | 2 | D2 | W4 |

| 43 | Ocypus (Staphylinus) olens Műller, 1764 | 10 | 100 | C1 | 2.20 | 1 | D2 | W3 | |

| 44 | Xantholins linearis Olivier, 1795 | - | 119 | C1 | 5.62 | 2 | D2 | W4 | |

| 45 | XI. Sphindidae | Sphindus dubius Gyllenhal, 1808 | 153 | - | C1 | 5.29 | 2 | D2 | W4 |

| 46 | XII. Tenebrionidae | Stenomax aeneus Scopoli, 1763 | - | 174 | C1 | 8.22 | 2 | D2 | W4 |

| Total | 2890 | 2118 |

2021 |

minimum temperature -3.4 o C |

January |

2022 |

minimum temperature -4.520 C |

January |

| maximum temperature 25,08 oC | June | maximum temperature 26,81 0C | June | ||

| average temperature 9,85 0C | average temperature 11,60 0C | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).