Submitted:

22 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Formal Apparatus of System Identification Theory

2.1. Dynamic Systems and Models

2.2. Identifiability: Can Parameters Be Determined Uniquely?

2.3. Persistent Excitement: Richness of Input Signal

2.4. Fisher Information Matrix: How Much Information About Parameters?

2.5. Hankel Matrix: Minimal Model Complexity

2.6. Asymptotic Accuracy of Parameter Estimates

3. Newton’s First Law: Non-Informativeness Under Zero Excitation

3.1. Traditional Formulation

3.2. Reinterpretation Through Data Informativeness

3.3. Reformulation of the First Law in Terms of Identifiability

4. Newton’s Second Law: Mass as a Conditioning Parameter

4.1. Traditional Formulation

4.2. Transfer Function and Hankel Rank

- : — static system without dynamics. Input is instantaneously transmitted to output: . This corresponds to the first law ( at ) — no memory, no inertia.

- : — simple integrator. Impulse response (step). The Hankel matrix has . Physically, this corresponds to a system where force directly determines velocity: (motion in a viscous medium at low Reynolds numbers). Insufficient for describing inertial dynamics — no second derivative.

- : — double integrator. Impulse response grows linearly. Hankel rank . This is the minimal non-trivial identifiable model describing inertial motion.

- : Transfer functions , , etc., have impulse responses , , and so on. Hankel rank increases: rank = 3, 4, ... However, such models are physically unrealistic for a point mass and excessively complex. At typical noise levels (SNR), adding poles above second order does not improve identifiability — additional parameters "sink" in noise.

- 1.

- Describes non-trivial dynamics (differs from static and simple integrator)

- 2.

- Physically corresponds to inertial motion

- 3.

- Is identifiable under reasonable experimental conditions (two excitation frequencies)

4.3. Mass and Fisher Information Matrix

- 1.

- Use low-frequency excitation (increase )

- 2.

- Minimize measurement noise

- 3.

- Increase experiment duration N (variance decreases as according to Theorem 9.1)

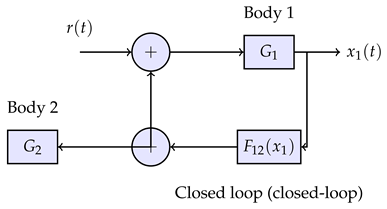

5. Third Law of Newton: Self-Consistency in Closed Systems

5.1. Traditional Formulation

5.2. Identification in Closed Loops: The Indistinguishability Problem

5.3. Self-Consistency and Conjugacy of Operators

- 1.

- Uniqueness of interaction channel:there exists one bidirectional channel, not two independent unidirectional ones

- 2.

- Energy closure:energy is not created or destroyed in the interaction channel

- 3.

- Identifiability of the combined structure:the joint model of the system has a finite Hankel rank

5.3.1. 1. Uniqueness of Interaction Channel

5.3.2. 2. Energy Closure

5.3.3. 3. Identifiability of the Combined Structure

5.4. Reframing the Third Law in Terms of Identifiability

6. Radical Ontological Differences Between the Two Interpretations

6.1. What is Absent in the Proposed Interpretation

6.1.1. 1. Mass as an Intrinsic Objective Property of an Object

6.1.2. 2. Space and Coordinate Grid as a Geometric Entity

6.1.3. 3. Force as an Important Physical Entity

6.1.4. 4. Global Clockwork of Time

6.1.5. 5. Action at a Distance Without Mechanism Explanation

6.2. What Exists Instead of Canonical Concepts

6.2.1. 1. Electromagnetic Spectrum as Observation Channel

6.2.2. 2. Frequency and Phase Domain Instead of Time Domain

6.2.3. 3. Fisher Information Matrix and Cramér-Rao Bound

6.2.4. 4. Boundaries of Knowability BEFORE Model Construction

- 1.

- First analyze identifiability boundaries: which models can in principle be distinguished from data?

- 2.

- Then among identifiable models, choose the minimal in complexity (minimum Hankel rank)

- 3.

- Finally verify whether experimental data are consistent with the chosen model

6.3. Conceptual Economy and Explanatory Power

6.3.1. Conceptual Cleanliness

- Existence of absolute space (or spacetime)

- Existence of mass as intrinsic property of body

- Existence of force as physical entity

- Action at a distance without mechanism

- Uniform flow of time

- Existence of observation channel (electromagnetic spectrum)

- Ability to influence channel input and observe output

- Stationarity of processes (for applicability of Khinchin’s theorem)

6.3.2. Economy of Postulates

6.3.3. Practical Power

6.4. Practical Perspective: Model Usefulness

- Predictive power: how accurately does model predict for new ?

- Parameter parsimony: is Hankel rank minimal (Occam’s razor)?

- Identifiability: can parameters be reliably estimated (rank() = d)?

- Conditioning: how sensitive are estimates to noise (condition number)?

6.5. Historicity and Channel Memory

6.6. Section Conclusion

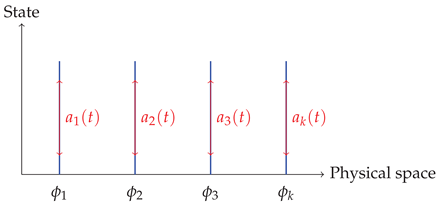

7. Coordinates as Indices of Spectral Modes

7.1. Spectral Decomposition and Modes

7.2. Coordinate Invariance and Minimal Realizations

7.3. Center of Mass as Minimal Parameterization

8. Momentum as the Minimally Identifiable Conserved Quantity

8.1. Velocity as the First Stable Quantity

8.2. Momentum and the Coefficient at 1/s

8.3. Momentum Conservation in Closed Channels

8.4. Non-Compensable 1/s² Mode and Identification Stability

- 1.

- "Detectability": output responds to input, although system does not decay

- 2.

- "Bounded inputs": physical forces are bounded

- 3.

- "Finite Hankel rank": rank() = 2 is finite

8.5. Center of Mass and Uniqueness of Parameterization

- Hankel rank is minimal (rank = 1)

- Coefficient at corresponds to total system momentum

- There are no internal couplings (minimal model)

9. Energy as the Invariant Norm of Identifiable Dynamics

9.1. Quadratic Norms in Linear Identification

9.2. Kinetic Energy as the Norm of Velocity

- —output of system

- T—quadratic norm of signal

- m—metric (Gramian matrix) in velocity space

9.3. Potential Energy and Internal Operator

9.4. Energy Conservation = Norm-Preserving Operator

- Eigenvalues have nonzero real part

- System either grows exponentially () or decays ()

- Growth destroys identifiability: Hankel rank

- Decay means dissipation—the system cannot be considered closed

9.5. Dissipation as Channel Leakage

9.6. Trinity: Inertia, Momentum, Energy

- 1.

- Inertia(m)—conditioning parameter of identification via Fisher information matrix:

- 2.

- Momentum()—conserved coefficient at in closed channel

- 3.

- Energy()—invariant quadratic norm preserved by norm-preserving evolution operator

10. Rotation, Phase Loss, and Bessel Functions

10.1. Rotation as Phase Averaging Mechanism

Slow rotation ():

Fast rotation ():

10.2. Transition from Fourier to Bessel Upon Phase Loss

10.3. Bessel Zeros as Identifiability Boundaries

10.4. Cryo-EM: Experimental Example of Phase Loss

10.5. Angular Momentum as Conserved Coefficient at 1/s

10.6. Differential Rotation and Spiral Structures

- Galaxies: rotation curve is typically flat at large radii, whence (dark matter problem).

- Accretion disks: Keplerian rotation around black holes.

- Hurricanes: inner part—solid-body rotation , outer—potential vortex .

- Sun: equatorial zone rotates faster than polar regions.

- Kepler: (gravitational dominance)

- Galaxy: to (flat rotation curve)

- Potential vortex: (circulation conservation)

10.7. Extreme Physical Information and Rotational Dynamics

- I—Fisher information from Section 2.4

- J—effective information extracted via Hankel operator under channel constraints (noise, finite observation time)

- —information loss due to channel limitations

- 1.

- Avoid resonances (different modes do not interfere)

- 2.

- Maximize rank under energy constraint

- 3.

- Minimize information loss at Bessel zeros

- Quadraticity of Lagrangians ()

- Power laws (scaling laws) in critical phenomena

- Schrödinger equation (as condition for minimizing for quantum systems)

- Bessel functions as optimal basis for rotating systems with phase loss

- Differential rotation as mechanism for avoiding mode conflict

- Spiral structures as geometric consequence of identifiability optimization

10.8. Section Conclusion

- 1.

- Phase loss under fast rotation transforms Fourier basis into Bessel basis through averaging

- 2.

- Bessel zeros become "blind spots"—points of fundamental unidentifiability (Fisher = 0, Cramér-Rao = ∞)

- 3.

- Angular momentum is interpreted as coefficient at in angular dynamics, conserved in closed channel

- 4.

- Differential rotation—not coincidence but optimal strategy for avoiding mode conflict in joint channel use

- 5.

- Spiral structures—geometric consequence of identifiability optimization

- 6.

- EPI principle explains universality of Bessel modes, quadratic norms and power laws as consequence of requiring maximum informativeness under channel constraints

Affiliation and Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. A Parable About a Physicist, Seeds, and Total Darkness

Appendix A.1. Problem Statement

- Seeds—unlimited supply. This is your input signal .

- Ability to throw—you can control where and with what force to throw. This is the ability to influence the system.

- Two ears—you hear in stereo. Left and right ears receive signal with different delays and amplitudes. This is two-channel observation .

- Rotating chair—you can turn in place, changing orientation relative to sound sources. This is controlled modulation of the observation channel.

- Memory—you remember what you threw a second ago, two seconds ago. The system does not reset after each throw. There are temporal correlations.

- Pulse—you can count your own pulse as a rough internal rhythm. This is analogous to discrete time (pulse beats).

- Vision—no direct access to "space geometry".

- Coordinate grid—no predefined axes . Where is up, where is down, where is left, where is right—unknown.

- Uniform clock—pulse exists, but it is uneven and not global (this is your internal rhythm, not "world time").

- Notion of "force"—you simply throw seeds somehow, without a theory of "gravity" or "inertia".

Appendix A.2. Experiment 1: Not Throwing Seeds—Learning Nothing

Appendix A.3. Experiment 2: Throwing Uniformly—Learning Little

Appendix A.4. Experiment 3: Role of Two Ears

Appendix A.4.1. Interaural Time Difference

Appendix A.4.2. Phase Difference

Appendix A.4.3. Experiment: Plugging One Ear

Appendix A.5. Experiment 4: Rotation on Chair

Appendix A.5.1. What Happens During Rotation

- At : maximum response (throw perpendicular to wall)

- At : weaker response (throw at angle)

- At : almost no response (throw almost parallel to wall)

Appendix A.5.2. Formal Interpretation

Appendix A.5.3. Experiment: Not Rotating

Appendix A.6. Experiment 5: Most Critical—One Ear + No Rotation

- When response arrived (delay )

- How loud response (amplitude)

- Statistics of hits (how often I hear responses with random throws)

- Where sound came from (direction)

- How many objects at the same distance (all merge into one "ring")

- Object shapes (only radial profiles distinguishable)

Appendix A.7. Experiment 6: Throwing in Different Directions—Structure Emerges

- Forward—dull thud (soft wall, far)

- Left—ringing clang (metal plate, close)

- Right—nothing (window open)

- Up—thud with delay (ceiling high)

- Down—almost instant thud (floor close)

Appendix A.8. Experiment 7: Echolocator—Complete Picture

Appendix A.9. Identifiability Conditions Table

| Conditions | Eff. dimension | What is lost |

| Rotation + 2 ears | ∼2D (non-integer) | — |

| No rotation | ∼1D | angles |

| One ear | ∼1–1.5D | chirality |

| No rotation + 1 ear | ∼1D → <1 | almost everything |

- Rotation + 2 ears: rank() ≥ 2, system fully identifiable

- No rotation: rank() drops, angular modes degenerate

- One ear: Loss of antisymmetric part of observation operator

- No rotation + one ear: rank() = 1, system reduces to radial profile

Appendix A.10. Where Do "Coordinates" and "Space" Come From?

- Direction 1 (forward) → call it "axis x"

- Direction 2 (left) → call it "axis y"

- Direction 3 (up) → call it "axis z"

Appendix A.11. Where Does "Mass" Come From?

Appendix A.12. Where Does "Time" Come From?

Appendix A.13. Three Newton’s Laws in Darkness

Appendix A.13.1. First Law: Not Throwing Seeds—Learning Nothing

Appendix A.13.2. Second Law: Need Minimum Two Types of Throws

Appendix A.13.3. Third Law: Echo Must Be Symmetric

Appendix A.14. Fundamental Conclusion

- Do not "help" get more information

- Make problem fundamentally solvable

Appendix A.15. Moral of Parable

- "Absolute space" not needed—mode indices suffice

- "Mass as object property" not needed—conditioning parameter suffices

- "Force as entity" not needed—input signal suffices

- "Absolute time" not needed—ordering index suffices

- Observation channel (hearing in darkness = electromagnetic spectrum in reality)

- Ability to influence input (throw seeds = apply forces)

- Response observation (hear sound = measure trajectories)

- Memory (system does not reset = temporal correlations)

- Symmetry breaking (two ears + rotation = multichannel observation with controlled modulation)

Appendix B. The Dzhanibekov Effect: Information Loss and Orientation Identifiability

Appendix B.1. Canonical Explanation and Its Limitations

Appendix B.2. Orientation as Hidden Identification Parameter

Appendix B.3. Spectral Decomposition and Bessel Functions

Appendix B.4. Evolution Through Zero-Identifiability Region

Appendix B.5. Topology of SO(3) and Flip as Branch Choice

- Measurement noise at moment of exit from zero-information region

- Small fluctuations of initial conditions

- Structure of information matrix in vicinity of zero

Appendix B.6. Role of Observers: Experimentally Testable Prediction

- 1.

- Flip suppression by multiple detectors. Increasing number of independent observation channels (video cameras at different angles, gyroscopic sensors, optical markers with different orientations, weak external field as additional reference) should make flip less abrupt, reduce its amplitude or completely suppress it.

- 2.

- Dependence on observation geometry. Flip probability and characteristic time should depend on observation angle and detector placement. Configurations where Bessel function zeros for different channels coincide give maximum effect prominence.

- 3.

- Role of microgravity. On Earth, gravitational field breaks rotational symmetry, acting as additional observation channel (via precession and libration). In microgravity this channel is absent—hence clearer manifestation of effect in space experiments.

- One camera (baseline configuration)

- Two cameras at angle

- Three cameras (tetrahedral configuration)

- Additional references (weak magnetic field, luminous markers)

Appendix B.7. Connection to Main Article Concept

- First law: Without excitation () data uninformative ⇒ without observer orientation unidentifiable

- Second law: Mass as identification conditioning parameter ⇒ moment of inertia as orientation identification conditioning parameter

- Third law: Symmetry of interactions ⇒ symmetry of information channels

Appendix B.8. Conclusion

Appendix C. Flickering Lighthouses in Darkness: Insights from the Frugal Devil’s Wife of Ancient Times

Appendix C.1. The Curious Title: Why the Devil’s Wife?

Appendix C.2. The Classical Lighthouse Problem and the b·ω Degeneracy

Appendix C.3. Extended Sensor Array: Physical Setup and Finite Constraints

Appendix C.26.1. Physical Parameters (Given)

- Sensor length: (finite spatial extent), sensor domain

- Observation time: (finite temporal extent)

- Signal propagation speed:c (speed of signal propagation along sensor wire from detection point to readout)

- Frequency resolution: (Fourier limit)

- Spatial resolution: (sensor element spacing or pixel size)

- Temporal resolution: (sampling rate of detection electronics)

Appendix C.26.2. Source Geometry

- : perpendicular distance from source to sensor line

- : lateral offset along sensor line (projection of source onto x-axis)

- : angular velocity of rotation

- : initial phase

Appendix C.26.3. Signal Propagation Delay

Appendix C.26.4. Complete Spatio-Temporal Signal

Appendix C.4. Three Independent Information Channels and Channel Independence

Appendix C.4.1. Channel 1: Spectral Frequencies

Appendix C.4.2. Channel 2: Spatio-Temporal Delays

Appendix C.4.3. Channel 3: Spatial Distribution

Appendix C.4.4. Formal Proof of Channel Independence

- 1.

- temporal spectrum at fixed x (depends only on )

- 2.

- cross-correlation between sensor positions (depends on )

- 3.

- spatial intensity distribution (depends on )

Appendix C.5. The Optimization Problem: Packing Lighthouses into Finite Constraints

Appendix C.5.1. Formal Problem Statement

- Sensor length L (finite spatial domain)

- Observation time T (finite temporal window)

- Signal propagation speed c along sensor

- Frequency resolution

- Spatial resolution (sensor element spacing)

- Temporal resolution (electronics sampling rate)

- Operating frequency range

- Spatial distribution of sources: (source density in space)

- Angular velocity assignment: (rotation law as function of position)

- 1.

-

Spectral separation:For any two sources at positions with angular velocities , harmonics must not overlap:where is the maximum observable harmonic order, determined by the signal-to-noise ratio and harmonic amplitude decay.

- 2.

- Spatial separation:Effective coverage regions must not completely overlap:

- 3.

- Delay resolvability:Time delays must be measurable:

- 4.

- Geometric confinement:All sources lie within a bounded domain:

- 5.

- Effective coverage:Sources must be detectable by the sensor:

Appendix C.5.2. Intuition for the Optimization

- 1.

- Spectral efficiency: To maximize K, we want to pack as many distinct frequencies into as possible.

- 2.

- Spatial efficiency: To maintain identifiability, sources must be spatially separated enough that their Cauchy distributions don’t completely merge on the sensor of length L.

Appendix C.6. Fundamental Limitations of Discrete Configurations

Appendix C.7. Continuous Formulation: The Way Out

Appendix C.7.1. From Discrete to Continuous

- : source density (number of sources per unit radius)

- : angular velocity as a function of radius

Appendix C.7.2. Spectral Density

Appendix C.7.3. Power-Law Differential Rotation

- : Solid-body rotation (all radii rotate together)

- : Keplerian rotation (gravitationally bound orbits)

- : Super-Keplerian (some accretion disk models)

Appendix C.7.4. Phase Averaging and the Emergence of Bessel Functions

Appendix C.7.5. Hankel Matrix for Continuous Systems

Appendix C.8. Variational Derivation of Logarithmic Spiral Geometry

Appendix C.8.1. Fisher Information Functional

Appendix C.8.2. Geometric Constraint

Appendix C.8.3. Variational Argument

- 1.

- The frequency range is covered: spans as varies.

- 2.

- Geometric confinement: for all .

- 3.

- Spatial separation: adjacent sources (infinitesimal increments ) must be spatially separated.

Appendix C.8.4. Combined Parameter

Appendix C.8.5. Why Logarithmic Spirals Are Optimal

- 1.

- Maximal spectral coverage: The exponential mapping provides uniform coverage in logarithmic frequency space, which is the natural scale for the spectral separation constraint.

- 2.

- Spatial efficiency: The self-similar structure of the logarithmic spiral means that the spatial separation between adjacent angular elements is proportional to the radius, matching the scaling of the effective coverage length .

- 3.

- Constant information density: Each angular increment contributes the same amount to the Fisher information, avoiding wasted capacity.

Appendix C.9. Main Optimality Theorem

- 1.

- Spatial distribution:Sources distributed along logarithmic spiral(s) (single spiral or superposition of multiple spirals)

- 2.

- Rotation law:Power-law differential rotation with

- 3.

- Combined parameter:

- Infinite Hankel rank (in the noise-free limit)

- Zero spectral interference between radial elements

- Complete parameter separability via three independent channels

- Optimal scaling of Fisher information with the number of sources

- In gravitational systems, (Keplerian) is dictated by Newton’s law.

- In accretion disks with viscosity, emerges from angular momentum transport.

- In designed sensor networks, β might be chosen to fit geometric constraints of the deployment region.

Appendix C.10. Connection to Bessel Functions and Identifiability Boundaries

Appendix C.10.1. Bessel Zeros as Identifiability Boundaries

Appendix C.10.2. Hankel Matrix Structure and Logarithmic Self-Similarity

Appendix C.11. Physical Manifestations and Concluding Remarks

- Spiral galaxies: Exhibit with (approximately Keplerian in outer regions). The spiral arm structure maximizes information transmission about the mass distribution to external observers.

- Accretion disks: Around compact objects (black holes, neutron stars), due to angular momentum transport. The logarithmic spiral structure optimizes radiative energy transfer.

- Hurricanes and cyclones: Logarithmic spiral cloud bands with differential rotation optimize energy and momentum transport in atmospheric/oceanic vortices.

- Biological structures: DNA double helix, nautilus shells, and other biological spirals provide optimal packing of genetic/structural information.

- 1.

- First Law (): No excitation ⇒ rank (parable: physicist in darkness)

- 2.

- Second Law (mass): Conditioning parameter ⇒ Var (parable: heavy seeds harder to identify)

- 3.

- Rotation + Bessel zeros: Angular averaging ⇒ at (parable: lighthouse at Bessel zero, observer blind)

Appendix D. Spectral Topology of Irreversibility: Information-Theoretic Foundation for Mass Anomalies in Non-Equilibrium Systems

Appendix D.1. 9.1. Introduction: Beyond Thermodynamic Irreversibility

Appendix D.2. 9.2. Spectral Overlap as the Fundamental Mechanism of Irreversibility

Appendix D.3. 9.3. Angular Velocity as an Information-Theoretic Control Parameter

Appendix D.4. 9.4. Persistent Excitation and the Requirement of White Noise

Appendix D.5. 9.5. Discrete Transitions and the Information Potential

Appendix D.6. 9.6. Historical Context: Kozyrev’s Experiments and the Reproduction Question

Appendix E. Where the Celestial Beacons Lead: Shadow Modes, Information Echoes, and the Fractal Topology of Pulsar Dynamics

Appendix E.1. Observational Evidence for Quasi-Periodic Structures

Appendix E.2. Theoretical Interpretation: Shadow Modes and Information Echoes

Appendix E.3. Takachenko Oscillations and Vortex Lattice Dynamics

| Observable | Takachenko/Vortex model | Spectral irreversibility |

| Period scaling | (geometric) | (fractal dimension) |

| Chirality | No prediction | |

| Integer period effect | Not predicted | Critical for detection |

| Fractal hierarchy | Discrete spectrum | Irrational period ratios |

| Partial observability | Implicit | Explicit via |

Appendix E.4. Predictions for System Identification Analysis

Appendix E.5. Methodology for Observational Verification

Appendix E.6. Methodological Considerations for Future Analysis

Appendix F. What the James–Stein Phenomenon Reveals About Identifiability Boundaries

Appendix F.1. Introduction: The James–Stein Paradox

Appendix F.2. The Paradox: Why Independent Parameters Help Each Other

Appendix F.3. The Unexplained Boundary at d=2

Appendix F.4. Proposed Reformulation: From Integer to Continuous Dimension

Appendix F.5. Information Channel Capacity: A Physical Interpretation

Appendix F.5.1. The EM Channel Has Intrinsic Dimensionality d=2

Appendix F.5.2. MaxEnt vs Minimax: Two Information Regimes

Historical precedent: Planck’s black body spectrum

Regime I: d≤2 (Channel capacity sufficient)

egime II: d>2 (Channel capacity exceeded)

Appendix F.6. Experimental Prediction

Appendix F.7. Channel-Imposed Identifiability Constraints

Appendix G. Drozd’s Theorem: A View from Algebra Representation Theory Theorem

Appendix G.1. The Fundamental Trichotomy: Finite, Tame, and Wild

Appendix G.2. Two Parameters After Fourier Transform: The Gateway to Complexity

Appendix G.3. Quiver Signal Processing: The Bridge Between Algebra and Signals

Appendix H. The Boundary of Non-Duality, Non-Objectivity: D4 by Dynkin

Appendix H.1. D4 as the Epistemological Boundary

Appendix H.2. The Failure of Spectral Classification

Appendix H.3. Tannakian Reconstruction and the Absence of Global Agreement

Appendix H.4. Time, Memory, and History: What D4 Lacks

Appendix H.5. Scale as the Boundary: Aggregation and Decoherence

Appendix H.6. The Electroweak Interaction as Physical Manifestation

Appendix H.7. Contextuality and the Kochen-Specker Theorem

Appendix H.8. Echo of Triality in Bayes’ Theorem and QBism

Appendix H.8.1. Ternary Structure of Bayesian Update

Appendix H.8.2. QBism: Quantum Bayesianism

Appendix H.8.3. Paradoxes of Bayesian Update: The Second Child Problem and Multiplicity of Trajectories

Appendix H.8.4. Bayesian Section as Choice of Ternary Structure: Towards Duality and Objectivity

Appendix H.8.5. Quantum Eraser and the Problem of Locality: Echo of Ternarity in Experiment

Appendix H.8.6. Biological Time and Its Plasticity: Neuroscientific Data

Appendix H.8.7. Time, Gravitation, and Electromagnetic Field: Physical Modulations of Temporality

Appendix H.8.8. D4 Triality: Mathematical Prototype

Appendix H.9. The Limit of Identification: Synthesis and Outlook

References

- Ljung, L. System Identification: Theory for the User, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, G.N. A Treatise on the Theory of Bessel Functions, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kozyrev, N.A. Causal or Asymmetrical Mechanics in the Linear Approximation; (in Russian). Pulkovo Observatory: Saint Petersburg, Russia, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kozyrev, N.A. On the Possibility of Experimental Investigation of the Properties of Time. In Time in Science and Philosophy; Academia: Prague, Czech Republic, 1971; pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kozyrev, N.A. Selected Proceedings; (in Russian). LGU Publishing: Saint Petersburg, Russia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rokityansky, I.I. North-South Asymmetry of Planets as Effect of Kozyrev’s Causal Asymmetrical Mechanics. Acta Geod. Geophys. Hung. 2012, 47, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikhobalov, L.S. The Fundamentals of N.A. Kozyrev’s Causal Mechanics. In On the Way to Understanding the Time Phenomenon: The Constructions of Time in Natural Science. Part 2: The "Active" Properties of Time According to N.A. Kozyrev; Levich, A.P., Ed.; World Scientific: Singapore, 1996; pp. 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tajmar, M.; Plesescu, F.; Seifert, B.; Marhold, K. Measurement of Gravitomagnetic and Acceleration Fields Around Rotating Superconductors. AIP Conf. Proc. 2007, 880, 1071–1082, arXiv:gr-qc/0610015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajmar, M.; de Matos, C.J. Gravitomagnetic Field of a Rotating Superconductor and of a Rotating Superfluid. Physica C 2003, 385, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajmar, M.; de Matos, C.J. Gravitomagnetic Fields in Rotating Superconductors to Solve Tate’s Cooper Pair Mass Anomaly. In Proceedings of the Space Technology and Applications International Forum (STAIF 2006), 2006; AIP: Melville, NY, USA; pp. 1259–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Hayasaka, H.; Takeuchi, S. Anomalous Weight Reduction on a Gyroscope’s Right Rotations Around the Vertical Axis on the Earth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989, 63, 2701–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller, J.E.; Hollander, W.J.; Nelson, P.G.; McHugh, M.P. Gyroscope-Weighing Experiment with a Null Result. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 825–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, J.M.; Wilmarth, P.A. Null Result for the Weight Change of a Spinning Gyroscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 2115–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, A.K.; Shinbrot, T.; Cordes, J.M. A chaotic attractor in timing noise from the Vela pulsar? Astrophys. J. 1990, 353, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, K.; Deshpande, A.A.; Joshi, B.C.; et al. Post-glitch Recovery and the Neutron Star Structure: The Vela Pulsar. arXiv preprint 2025, arXiv:2506.02100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lower, M.E.; et al. On the quasi-periodic variations of period derivatives in radio pulsars. arXiv preprint 2025, arXiv:2501.03500. [Google Scholar]

- Shahabasyan, K.M.; et al. Quasi-periodic Variations in Period Derivatives and Vortex Lattice Oscillations. Proc. Modern Phys. Compact Stars Conf., 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cordes, J.M.; Helfand, D.J. Pulsar Timing. III. The Timing Residuals, Robust Statistics, and Variances. Astrophys. J. 1980, 239, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyne, A.G.; Graham-Smith, F. Glitches and the Variability of Pulsar Rotation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1998, 296, 913–918. [Google Scholar]

- Melatos, A. Vortex Pinning in Pulsar Glitches. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1997, 288, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.W.; Itoh, N. Pulsar Glitches and Turbulence in Superfluids. Nature 1975, 256, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takachenko, V.K. Vibrations of a Vortex Lattice. Sov. Phys. JETP 1966, 23, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkin, M.; et al. Prospects for Detecting Gravitational Waves from Precessing Neutron Stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2018, 474, 4040–4058. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, C. Inadmissibility of the usual estimator for the mean of a multivariate normal distribution. In Proceedings of the Third Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1956; Volume 1, pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- James, W.; Stein, C. Estimation with quadratic loss. In Proceedings of the Fourth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1961; Volume 1, pp. 361–379. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, B.; Morris, C. Stein’s paradox in statistics. Scientific American 1977, 236, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samworth, R.J. Stein’s paradox. Eureka 2012, 62, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.D.; Zhao, L.H. A geometrical explanation of Stein shrinkage. Statistical Science 2012, 27, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Large-Scale Inference: Empirical Bayes Methods for Estimation, Testing, and Prediction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liashkov, M. Two Principles Redefining Physics and Time: Empirical Arguments and Immediate Benefits. Zenodo. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Drozd, Y.A. On tame and wild matrix problems. In Matrix Problems; Institute of Mathematics, Academy of Sciences of Ukraine: Kiev, 1977; pp. 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Drozd, Y.A. Tame and wild matrix problems. In: Dlab, V., Gabriel, P. (eds) Representation Theory II. Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol 832. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 242–258. 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley-Boevey, W.W. On tame algebras and bocses. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 1988, 56(3), 451–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuschke, G.J. Wild Hypersurfaces. Syracuse University Seminar Notes. 2010. Available at: https://leuschke.org/uploads/Research/SU-wildhyps.pdf.

- Oppenheim, A.V.; Schafer, R.W. Discrete-Time Signal Processing, 3rd ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, G.R.; Swamy, M.N.S. Hilbert transform relations for complex signals. Signal Processing 1991, 22(2), 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Püschel, M.; Moura, J.M.F. Algebraic Signal Processing Theory: Foundation and 1-D Time. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2008, 56(8), 3572–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada-Mayorga, A.; Riess, H.; Ribeiro, A.; Ghrist, R. Quiver Signal Processing (QSP). 2020. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.11525.

- Baez, J.C. The Dodecahedron, the 24-Cell, and Triality. Expository Notes 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley, P. Probability and Measure; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R.L. Notes on Spinors in Low Dimension. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2011.05568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalley, C. The Algebraic Theory of Spinors and Clifford Algebras; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Deligne, P. Catégories Tannakiennes. In Grothendieck Festschrift; Birkhäuser: Boston, MA, USA, 1990; Volume II, pp. 111–195. [Google Scholar]

- Deligne, P. Quantum Fields and Strings: A Course for Mathematicians; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Deligne, P. Tensor Categories with Finite Fiber Functors. Pacific J. Math. 2002, 231, 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Embrechts, P.; Klüppelberg, C.; Mikosch, T. Modelling Extremal Events; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Feller, W. An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Furey, C. Unified Theory of Ideals. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 90, 124062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furey, C. SU(3)C×SU(2)L×U(1)Y as a Subgroup of SL(3,C)×SL(2,C). J. High Energy Phys. 2018, 09, 045. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, J.E. Introduction to Lie Algebras and Representation Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, H. Electroweak Quantum Numbers in the D4 Root System. arXiv preprint 2024, arXiv:2409.15385. [Google Scholar]

- Joyal, A.; Street, R. Braided Tensor Categories. Adv. Math. 1991, 102, 20–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochen, S.; Specker, E.P. The Problem of Hidden Variables in Quantum Mechanics. J. Math. Mech. 1967, 17, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.J. Representations of the Even Clifford Algebra. Topics in Geometry and Physics 1996, 225–244. [Google Scholar]

- Peres, A. Quantum Theory: Concepts and Methods; Kluwer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra, R.C. Tannaka Categories. Ph.D. Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, Canada, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Samoradnitsky, G.; Taqqu, M.S. Stable Non-Gaussian Random Processes; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wallach, N.R. Real Reductive Groups; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Abramsky, S.; Brandenburger, A. The Logical Structure of Classical and Quantum Theory. New J. Phys. 2011, 13, 113036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamović, D.; Milas, A. On the Vertex Algebra Approach to Symmetries of Logarithmic CFT Models. In Contemporary Mathematics; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2008; Volume 497, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, M.; Wallman, J.J.; Veitch, V.; Emerson, J. Contextuality Supplies the Magic for Quantum Computation. Nature 2014, 510, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).