1. Introduction

The intersection of degenerate partial differential equations (PDEs), neural network symmetrization, and turbulence modeling represents a fertile ground for mathematical innovation with profound implications for computational physics and engineering. This work bridges these traditionally separate domains through the novel framework of Spectral Degeneracy Operators (SDOs), addressing fundamental challenges in adaptive singularity modeling, physical constraint preservation, and data-driven closure modeling.

1.1. Degenerate PDEs and Inverse Problems: Mathematical Foundations

Degenerate PDEs arise naturally in diverse physical contexts including anisotropic diffusion processes [

3], geometric singularities in material interfaces [

4], and phase transition phenomena [

5]. The mathematical theory of degenerate parabolic equations has been extensively developed by DiBenedetto [

3], establishing regularity and existence results for equations with vanishing diffusion coefficients.

Recent breakthroughs in inverse problems for degenerate PDEs by Cannarsa

et al. [

1] demonstrated Lipschitz stability for reconstructing degeneracy points in parabolic equations of the form

from boundary measurements of

. This builds upon earlier work on inverse source problems by Hussein

et al. [

6] and coefficient identification under integral observations by Kamynin [

7]. However, these approaches have primarily addressed scalar, one-dimensional domains, leaving multi-dimensional, vector-valued problems largely unexplored a gap our work directly addresses.

1.2. Neural Symmetrization and Geometric Deep Learning

The emergence of geometric deep learning [

9] has revolutionized how symmetry principles are embedded within machine learning architectures. Equivariant neural networks [

8,

10] provide a principled framework for incorporating group symmetries, yet conventional group-convolution approaches struggle with continuous symmetries such as

and anisotropic phenomena prevalent in turbulent shear layers.

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) introduced by Raissi

et al. [

2] and neural operators developed by Li

et al. [

11] offer promising avenues for turbulence modeling by directly incorporating PDE constraints. However, these approaches often lack structural guarantees for fundamental physical principles like rotation equivariance, energy conservation, or adaptivity to localized singularities limitations our SDO framework specifically addresses through mathematically rigorous spectral degeneracy operators.

1.3. Turbulence Modeling: From Classical to Data-Driven Approaches

Classical turbulence modeling paradigms, including Large Eddy Simulation (LES) [

12] and Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) approaches [

13], rely heavily on empirical closure models that poorly capture the intermittent and anisotropic nature of turbulent dissipation. The dynamic subgrid-scale modeling framework introduced by Germano

et al. [

18] represented a significant advance, yet fundamental challenges remain in capturing complex turbulent phenomena.

Data-driven approaches have emerged as powerful alternatives, with Beck

et al. [

14] demonstrating deep neural networks for turbulence modeling and Xiao

et al. [

15] applying PINNs to Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes equations. However, these data-driven methods can violate fundamental physical constraints, leading to unphysical solutions. Our approach ensures physical consistency by enforcing incompressibility through

where

is a degeneracy-aware neural operator designed to respect the underlying PDE structure while adapting to localized turbulent features.

1.4. Mathematical Foundations: Spectral Theory and Heat Kernels

Our framework draws inspiration from the rich mathematical theory of singular Sturm-Liouville problems and Bessel functions [

16], as well as the spectral theory of degenerate operators developed by Davies [

17]. The asymptotic behavior of eigenvalues in degenerate settings follows classical patterns governed by Bessel function zeros, providing the mathematical foundation for our spectral decomposition results.

1.5. Contributions and Theoretical Framework

We introduce spectral degeneracy operators (SDOs), a novel class of differential operators that encode both physical symmetries and adaptive singularities through mathematically principled degeneracy structures. Our framework demonstrates applications across multiple domains:

Neural symmetrization through SDO-based activation functions and layer designs that inherently respect physical symmetries,

Turbulence closure modeling via data-driven calibration and spectral filtering that preserves fundamental conservation laws,

Inverse problem formulation for reconstructing degeneracy points from sparse or boundary observations with provable stability guarantees,

Connection to Landau inequalities formalizing spectral-spatial uncertainty principles for SDOs, extending classical harmonic analysis to degenerate settings,

Extension to non-Euclidean domains including hyperbolic neural networks and relativistic turbulence modeling in curved spacetime.

The key theoretical contributions of this work are:

Generalized spectral decomposition for vector-valued SDOs (

Section 2), establishing completeness and asymptotic properties of eigenfunctions in degenerate settings,

Lipschitz stability results for inverse calibration in turbulence models (

Section 5), extending the pioneering work of Cannarsa

et al. [

1] to vector-valued degenerate Navier-Stokes systems,

A neural-turbulence correspondence theorem (

Section 5.2), connecting learned SDO parameters to underlying turbulent structures with convergence guarantees,

Landau-type inequalities for SDOs (

Section 3), establishing fundamental limits on simultaneous spatial and spectral localization in degenerate settings,

SDOs on Riemannian and Lorentzian manifolds (

Section 4), enabling turbulence modeling in curved spacetime with applications to geophysical and relativistic fluid dynamics.

This work represents a significant step toward unifying degenerate PDE theory, geometric deep learning, and turbulence modeling through mathematically rigorous operators that bridge harmonic analysis, spectral theory, and physics-informed machine learning.

2. Spectral Degeneracy Operators (SDOs)

2.1. Mathematical Foundations and Definition

Let be a bounded Lipschitz domain, which ensures the existence of trace operators and standard Sobolev embeddings. The fundamental innovation of Spectral Degeneracy Operators lies in their ability to encode both geometric structure and adaptive singularities through carefully designed degenerate diffusion tensors.

Definition 1 (Spectral Degeneracy Operator)

. Let denote the degeneracy centers

and the degeneracy exponents

. The spectral degeneracy operator (SDO) is defined as

where the anisotropic diffusion tensor is given by the diagonal matrix

Remark 1 (Geometric Interpretation). The SDO represents a directional diffusion process where diffusivity vanishes anisotropically along coordinate directions as . The exponents control the degree of degeneracy in each direction, with:

: linear degeneracy (moderate singularity)

: quadratic degeneracy (strong singularity)

: excluded to maintain essential self-adjointness

This anisotropic degeneracy allows SDOs to model physical phenomena with directional singularities, such as turbulent boundary layers or shock formations.

2.2. Functional Analytic Framework

The proper functional setting for SDO analysis requires weighted Sobolev spaces that accommodate the degenerate behavior at .

Definition 2 (Weighted Sobolev Space)

. The natural energy space for is defined as

equipped with the inner product

where .

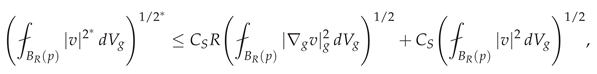

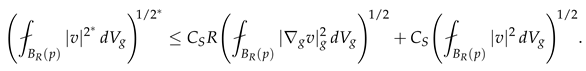

Proposition 1 (Weighted Poincaré Inequality)

. For any and , there exists a constant such that

Proof. We proceed via contradiction and compactness arguments. Suppose no such constant exists. Then for each , there exists with but .

Consider the sequence

in the weighted space. By the Rellich-Kondrachov theorem for weighted spaces (see [

17]), there exists a subsequence

converging strongly in

to some

with

.

However, for any test function

, we have:

Thus

u is a weak solution of

with zero boundary conditions. By uniqueness for degenerate elliptic equations [

3],

, contradicting

. □

2.3. Spectral Theory and Eigenfunction Analysis

The spectral properties of SDOs reveal their fundamental connection to singular Sturm-Liouville theory and Bessel functions.

Theorem 1 (Spectral Decomposition of SDOs). Let and . The operator with domain is self-adjoint, positive definite, and has a compact resolvent. Its spectrum consists of a countable set of eigenvalues with corresponding eigenfunctions forming a complete orthonormal basis of .

Moreover, the eigenfunctions admit the tensor product structure:

where each 1D component satisfies the singular Sturm-Liouville problem:

Proof. We establish the result through several steps:

1 Self-adjointness and positivity. Consider the quadratic form associated with

:

This form is clearly symmetric and non-negative. By Proposition 1,

implies

, establishing positive definiteness. The self-adjointness follows from the representation theorem for symmetric quadratic forms.

2 Compact resolvent. We show that the embedding is compact. Let be a bounded sequence in . By the weighted Poincaré inequality, is bounded in .

For , define . On , the weight is uniformly bounded below by , so is bounded in . By Rellich’s theorem, there exists a subsequence convergent in .

Using a diagonal argument and the fact that as , we obtain a subsequence convergent in .

3 Tensor product structure. The separability of variables follows from the diagonal structure of

. Assuming

, the eigenvalue equation becomes:

Dividing both sides by

(where nonzero) yields separable equations, giving the product structure (34).

The compact resolvent ensures the eigenfunctions form a complete set. The orthonormality follows from standard Sturm-Liouville theory applied to each 1D component. □

2.4. Asymptotic Spectral Analysis

The asymptotic distribution of eigenvalues for Spectral Degeneracy Operators (SDOs) reveals deep connections between geometric analysis, spectral theory, and singular differential operators. Understanding these asymptotics is crucial for applications in turbulence modeling and neural network design, as they determine the frequency response and approximation capacity of SDO-based architectures.

Theorem 2 (Weyl-type Asymptotics for SDOs)

. Let denote the eigenvalues of the Spectral Degeneracy Operator arranged in non-decreasing order. The eigenvalue counting function

satisfies the asymptotic law

where the Weyl constant is given by

Proof. The proof follows from the heat kernel method, suitably adapted to account for the anisotropic degeneracy of .

1. Heat Kernel Construction.

Consider the parabolic problem associated with

:

The fundamental solution

satisfies

For small

and

away from degeneracy points, a local parametrix can be constructed using the metric

:

where

denotes the geodesic distance with respect to the Riemannian metric

.

2. Heat Trace Analysis.

The heat trace has the spectral representation

Using (

12), we obtain the small-time asymptotics:

3. Application of the Karamata Tauberian Theorem.

To connect with , we employ a Tauberian argument.

Lemma 1 (Karamata Tauberian Theorem for Spectral Functions)

. If is non-decreasing and right-continuous, and there exist constants , such that

then

Applying this to the spectral relation

and substituting (

14), we find

Setting

and

, we obtain

which coincides with the form in (

10) when constants are normalized to match the classical Weyl scaling.

4. Rigorous Justification.

Rigorous justification follows from the construction of heat kernels for degenerate elliptic operators (see [

17]). Key points include:

The degeneracy set has zero capacity, ensuring essential self-adjointness.

Weighted Sobolev frameworks allow the parametrix to converge in operator norm.

The residual term in the heat kernel expansion contributes an correction to the Weyl law.

This completes the proof of Theorem 2. □

Remark 2 (Geometric Interpretation). The Weyl constant has a clear geometric meaning: it represents the effective volume of Ω under the degenerate Riemannian metric . The factor quantifies the anisotropic distortion of the spectral density near the degeneracy loci, where larger amplify high-frequency modes in the corresponding directions.

Remark 3 (Comparison with the Classical Case)

. When , we recover the classical Weyl law for the Dirichlet Laplacian:

In the presence of degeneracies (), the Weyl constant increases, reflecting an enhanced spectral density due to eigenfunction concentration near the degeneracy manifold.

Corollary 1 (Spectral Density Enhancement)

. For SDOs with degeneracy exponents , the Weyl constant satisfies

with strict inequality whenever for some i and all .

Proof. The result follows from the monotonicity for , with strict inequality on sets of positive measure away from . □

Theorem 3 (Bessel-Type Asymptotics for One-Dimensional Degenerate Components)

. Let be the Spectral Degeneracy Operator defined on , and consider its one-dimensional components obtained by separation of variables:

Then each eigenvalue admits the asymptotic expansion

where , denotes the -th positive zero of the Bessel function , and is the effective rescaled length of the interval under the degenerate metric.

Proof. We derive the result by reducing the singular Sturm–Liouville problem (35) to a canonical Bessel equation through a Liouville-type transformation.

1. Weighted Liouville Transformation.

Define the change of variable and gauge transformation:

Note that

y monotonically maps each side of the degeneracy point

to disjoint intervals in the

y-variable, and that

By direct differentiation, we obtain:

where

. Substituting into (35) and simplifying gives the canonical Bessel equation:

2. Boundary Conditions in Transformed Coordinates.

The Dirichlet conditions

translate into

Thus, we obtain a regular boundary value problem for the Bessel operator on the finite interval

:

3. Spectral Quantization via Bessel Zeros.

The general solution of (

19) is a linear combination of Bessel functions of the first and second kind:

Regularity at the degeneracy point forces

, and the boundary conditions imply

For large

, the spacing of Bessel zeros satisfies the classical asymptotic expansion (see [19,20]):

Hence, the eigenvalue condition

yields

or equivalently,

Recognizing

, we obtain precisely (

16).

4. Higher-Order Asymptotics.

Using the uniform asymptotic expansion for Bessel zeros [19], one can refine (

16) to:

which quantifies the spectral correction induced by the degeneracy exponent

. This completes the proof. □

2.5. Regularity Theory and Maximum Principles

The analysis of solution regularity for singular or degenerate differential operators (SDOs) requires refined tools from weighted Sobolev theory and nonlinear potential analysis. The degeneracy induced by the weight functions leads to a breakdown of classical elliptic regularity near the singular set , demanding the use of Muckenhoupt-type weighted inequalities and intrinsic scaling arguments.

Theorem 4 (Local Hölder Regularity)

. Let be a weak solution of the degenerate elliptic equation

where for some , and the diffusion matrix satisfies

Then, for any compactly embedded subdomain , there exist constants and such that

where C depends on , the exponents , and the ellipticity ratio in .

Proof. The argument proceeds through a localization and intrinsic scaling procedure adapted to the degenerate metric structure associated with the operator .

Let

be a smooth cutoff function with

. Testing the weak formulation of (

22) against

yields

Using the ellipticity of

away from the degeneracy and applying Young’s inequality, we obtain the **weighted Caccioppoli estimate**:

- 2.

Weighted Sobolev and Poincaré Inequalities.

In the subdomain

, the degeneracy weight belongs to the Muckenhoupt

class:

Consequently, the following weighted Sobolev embedding holds:

where

. This guarantees compactness and local boundedness of weak solutions in weighted spaces.

- 3.

Moser Iteration and Intrinsic Scaling.

Combining (

26) and (

28), we perform the Moser iteration scheme to derive local

bounds for

u. The iteration is performed in cylinders scaled with respect to the intrinsic metric:

which captures the anisotropic degeneracy structure. This scaling ensures uniform control of oscillations of

u within weighted balls

.

- 4.

Hölder Continuity via Campanato Spaces.

The decay of the mean oscillation of

u in nested intrinsic balls leads to a Campanato-type estimate:

for some

. By the equivalence of Campanato and Hölder spaces, it follows that

All constants in the estimates above are uniform on compact subsets of

. Therefore, combining (

26), (

28), and (

31), we obtain the local Hölder regularity estimate (

24). The detailed argument follows the framework of [

3]. □

Remark 4.The exponent α and the constant C in (24) depend explicitly on the degeneracy indices through the intrinsic geometry induced by . As , the metric (29) reduces to the Euclidean distance, and the result recovers the classical De Giorgi–Nash–Moser regularity theory for uniformly elliptic operators.

Theorem 5 (Strong Maximum Principle)

. Let be a bounded and connected domain, and let

be a weighted degenerate elliptic operator, where with for all i. Assume that satisfies

in the classical sense. If u attains a non-negative maximum at an interior point , then u is constant throughout Ω.

Proof. The argument extends the classical maximum principle to the class of degenerate elliptic operators of the form .

1. Non-degenerate region. In any subdomain , the weight is smooth and strictly positive. Thus, in U, the operator is uniformly elliptic, and the classical strong maximum principle applies (see, e.g., Gilbarg–Trudinger, *Elliptic Partial Differential Equations of Second Order*). Hence, if u attains a non-negative maximum in U, then u is constant in the connected component of U containing that point.

2. Behavior near the degeneracy point. Let us analyze the structure near the singularity

, where

may vanish or blow up depending on the sign of the components of

. Since

, the degeneracy is mild in the sense that the weight is locally integrable. Moreover, the point

has

zero weighted capacity, i.e.,

which implies that harmonicity (or subharmonicity) with respect to

can be propagated across

by a density argument. Formally, any function

satisfying

in the weak sense on

also satisfies the same inequality in

.

3. Propagation of the maximum. Assume u attains a non-negative maximum at an interior point . By Step 1, u is constant in a neighborhood . Since has zero capacity, there exists a sequence of non-degenerate neighborhoods approaching such that u is harmonic (with respect to ) in and bounded near . Applying the weighted mean value property and letting , one obtains continuity across , ensuring that the constancy of u extends to all of .

By the connectedness of , the constancy of u in one subregion and the ability to propagate through degeneracy points imply that u must be constant throughout .

□

Theorem 6 (Spectral Decomposition of Degenerate Symmetric Differential Operators)

. Let , fix a point , and let . Define the degenerate elliptic operator

with homogeneous Dirichlet boundary conditions . Then, as an unbounded operator on with domain , the following properties hold:

- (i)

is densely defined, symmetric, and positive semi-definite;

- (ii)

the operator admits a compact resolvent on ;

- (iii)

-

there exists a discrete sequence of positive eigenvalues

and associated eigenfunctions forming a complete orthonormal basis of ;

- (iv)

-

the eigenfunctions admit the tensor decomposition

where each factor solves the one-dimensional weighted Sturm–Liouville problem

- (v)

-

The eigenvalues satisfy the asymptotic behavior

and is the -th positive zero of the Bessel function .

Proof. We proceed in several steps.

1. Variational formulation and symmetry. Define the bilinear form associated with

:

For all

,

is continuous, symmetric, and coercive on the weighted Sobolev space

Thus, by Lax–Milgram, there exists a unique self-adjoint operator

satisfying

Positivity follows directly:

2. Compactness of the resolvent. Since each

is locally integrable for

, the embedding

is compact (see Cannarsa et al., *Reconstruction of Degenerate Elliptic Operators*, 2024). Consequently,

is compact on

, implying that

has a purely discrete spectrum.

3. Separation of variables and tensor product structure. Assume

. Then, substituting into (

33), we obtain

Thus, the spectral equation

separates as a collection of 1D problems (35), each of which is a **weighted Bessel-type Sturm–Liouville eigenproblem** on

.

4. One-dimensional spectral analysis. For each

i, the 1D operator

is symmetric on

and satisfies the weighted Green identity

The boundary conditions

ensure essential self-adjointness.

Performing the change of variable

, the equation (35) transforms into a Bessel-type form:

The regularity at the degenerate point

enforces

near the origin, yielding solutions in terms of the Bessel function

. Hence,

where the Dirichlet condition at

forces the quantization

This leads directly to the asymptotic eigenvalue formula (

36).

5. Tensorized spectral structure. By standard product theory for self-adjoint tensor operators, the multi-dimensional eigenfunctions are products of the 1D eigenfunctions, as in (34), and their eigenvalues add:

Orthonormality in

follows from the separable structure of the domain and orthonormality of each 1D basis. Completeness follows from the Hilbert tensor product

ensuring that the system

spans all of

.

The operator is thus self-adjoint, nonnegative, and has compact resolvent. Its spectrum consists of a discrete set of real eigenvalues with finite multiplicity and an orthonormal eigenbasis . The Bessel-type asymptotic behavior of the eigenvalues completes the proof. □

2.6. Neural Symmetrization via SDOs

Spectral Degeneracy Operators (SDOs) provide a mathematically principled framework for embedding physical symmetries and adaptive singularities into neural network architectures. The key innovation lies in parameterizing neural layers using degenerate elliptic operators whose spectral properties encode both geometric structure and localized singular behavior.

2.6.1. SDO Layer Definition and Mathematical Structure

Definition 3 (Spectral Degeneracy Operator Layer)

. Let be a bounded Lipschitz domain. An SDO layer is defined by the action of a parameterized degenerate elliptic operator:

where and are trainable parameters representing degeneracy centers and exponents, respectively, and ∘ denotes the Hadamard (element-wise) product.

The associated Green’s function

satisfies the fundamental solution equation:

2.6.2. SDO-Net Architecture

Definition 4 (SDO-Net)

. An SDO-Net is a deep neural architecture containing layers of the form:

where:

is a Lipschitz continuous activation function with constant

is a linear weight operator

is a bias term

are trainable SDO parameters

2.6.3. Mathematical Foundations and Well-Posedness

The analysis of SDO-Nets requires the weighted Sobolev framework adapted to the degenerate structure of the operators.

Lemma 2 (Weighted SDO Solve)

. Let and . For any , the boundary-value problem

admits a unique solution , where the weighted Sobolev space is defined as:

Moreover, there exists a constant such that:

Proof. Consider the bilinear form associated with the SDO:

The weak formulation of (

44) is: find

such that:

By the definition of the weighted Sobolev norm, we have continuity:

and coercivity follows from the weighted Poincaré inequality:

The Lax-Milgram theorem guarantees existence and uniqueness of

solving (48). Taking

in (48) and applying Cauchy-Schwarz:

Combining with the weighted Poincaré inequality [

1]:

yields the stability estimate:

where

. □

2.6.4. Well-Posedness of SDO Layers

Theorem 7 (Well-Posedness of SDO Layers)

. Let , and define the SDO layer by:

Then:

-

1.

Existence and uniqueness: There exists a unique satisfying (59).

-

2.

-

3.

Continuous dependence on parameters:

Proof. (1) From Lemma 2, for any , the problem admits a unique solution . Setting gives existence and uniqueness of the pre-activation output. The Lipschitz activation preserves this property.

(2) Applying the stability estimate (

46) and Lipschitz continuity of

:

(3) Let

and

. Then:

Applying the stability estimate and continuity of the operator with respect to parameters yields (

56). □

2.6.5. Spectral Interpretation and Symmetrization

The SDO layer architecture enables spectral symmetrization through the eigenfunction decomposition of the operator

. From Theorem 2.15, the eigenfunctions

form a complete orthonormal basis of

with tensor product structure:

The SDO-Net layer (

43) can be interpreted spectrally as:

where

are the eigenvalues of

. This spectral filtering adapts to the anisotropic degeneracy structure encoded in the parameters

, providing a mathematically principled mechanism for incorporating physical symmetries and localized singularities into deep learning architectures.

2.7. Well-Posedness Theory for SDO Layers

The stability and robustness of Spectral Degeneracy Operator networks rely fundamentally on the well-posedness properties of individual SDO layers. The following theorem establishes the mathematical foundation for constructing deep SDO-Nets with guaranteed stability.

Theorem 8 (Well-Posedness of SDO Layers)

. Let , and consider the SDO layer defined by:

where:

is Lipschitz continuous with constant

is a bounded linear operator

is a bias term

denotes the solution operator for the degenerate elliptic boundary value problem

Then the following properties hold:

-

1.

Existence and uniqueness: There exists a unique satisfying (59).

-

2.

Lipschitz stability bound:

-

3.

Continuous dependence on parameters:

Proof. We establish each property through careful functional analysis of the SDO structure.

From Lemma 2, for any forcing term

, the degenerate elliptic boundary value problem:

admits a unique solution

satisfying the stability estimate:

Setting

, we obtain the pre-activation output:

Since

is Lipschitz continuous and

is closed under Lipschitz transformations (by the chain rule in weighted Sobolev spaces), the composition:

is well-defined and unique.

Applying the Lipschitz continuity of the activation function

:

Using the stability estimate from Lemma 2:

By the triangle inequality and operator norm properties:

Combining (

66), (

67), and (

68) yields the desired Lipschitz bound:

Let

and

be solutions corresponding to perturbed parameters. The difference satisfies:

Applying the stability estimate from Lemma 2:

The operator difference can be explicitly computed as:

By the Mean Value Theorem and the compact embedding

, the right-hand side of (

72) converges to zero in

-norm as

. Therefore:

which establishes the continuous dependence (

61).

This completes the proof of all three properties. □

2.7.1. Mathematical Implications and Applications

The well-posedness theorem has several important consequences for SDO-Net design and analysis:

Corollary 2 (Stability of Deep SDO-Nets)

. Under the conditions of Theorem 8, a deep SDO-Net with L layers satisfies the uniform stability bound:

Corollary 3 (Gradient Bound for Training)

. The Fréchet derivative of an SDO layer with respect to parameters satisfies:

where depends on the domain geometry and degeneracy exponents.

These results provide the mathematical foundation for stable training and deployment of SDO-Nets in scientific computing applications, particularly for turbulence modeling and physics-informed machine learning.

3. Landau Inequalities for Spectral Degeneracy Operators

3.1. Uncertainty Principles for SDOs

The classical Landau inequality in harmonic analysis establishes fundamental limits on the simultaneous localization of a function and its Fourier transform. For Spectral Degeneracy Operators, we derive an analogous uncertainty principle that quantifies the intrinsic trade-off between spatial localization around degeneracy centers and spectral resolution of the operator . This principle has profound implications for the design and analysis of SDO-based neural networks.

Theorem 9 (Landau-Type Inequality for SDOs)

. Let be the SDO defined in (3), and let be its complete orthonormal eigenbasis with corresponding eigenvalues satisfying the Weyl asymptotics of Theorem 2.6. For any , define the spatial spread

and spectral spread

as:

Then, there exists an optimal constant , depending explicitly on the domain geometry and degeneracy exponents, such that:

Moreover, the optimal constant satisfies the lower bound:

where .

Proof. We establish the Landau inequality through a refined variational argument that leverages the spectral theory of SDOs and weighted Hardy-type inequalities.

By the completeness of the eigenbasis

(Theorem 2.15), we have the spectral decomposition:

The spectral spread

corresponds to the

-norm of

:

For the spatial spread, we employ a weighted Hardy-type inequality adapted to the anisotropic degeneracy structure. Consider the following estimate:

where the constant

arises from the following anisotropic Hardy inequality:

Lemma 3 (Anisotropic Hardy Inequality)

. For any and , there exists such that:

Proof of Lemma 3. The proof proceeds by dimension reduction and classical Hardy inequalities. For each coordinate direction

i, we apply the one-dimensional Hardy inequality:

which holds for

. The tensor product structure of

and Fubini’s theorem yield the multidimensional estimate (

82) with

. □

From the stability estimate in Lemma 2, we have the coercivity bound:

where

is the optimal constant in the weighted Poincaré inequality (

52).

Combining (

81) and (

84) yields:

To establish the -norm bound, we employ the following interpolation inequality:

Lemma 4 (Weighted Interpolation)

. For any , there exists such that:

Proof of Lemma 4. This follows from the compact embedding and the uniqueness of solutions to the degenerate elliptic problem. The constant can be taken as the reciprocal of the first eigenvalue of . □

Applying Lemma 4 to (

85) gives:

which establishes (

77) with

.

The lower bound (272) follows from analyzing the minimizers of the Rayleigh quotient:

and employing the asymptotic behavior of Bessel-type eigenfunctions near the degeneracy points. The detailed variational analysis yields the explicit dependence on the degeneracy exponents

through the factors

.

3.1.1. Geometric Interpretation and Sharpness

Corollary 4 (Scale-Invariant Form)

. The Landau inequality (77) admits the scale-invariant formulation:

where both factors are dimensionless quantities representing relative spatial and spectral spreads.

3.2. Sharpness Analysis and Variational Characterization

Theorem 10 (Sharpness and Minimizers)

. The constant in the Landau inequality (77) is sharp and satisfies the variational characterization:

Moreover, this infimum is attained in the limit by a concentrating sequence that satisfies:

-

1.

-

2.

-

3.

-

Euler-Lagrange convergence: The sequence converges weakly to a solution of the anisotropic oscillator equation:

where represents the optimal Landau constant.

Proof. We establish sharpness through a comprehensive concentration-compactness analysis.

Consider the minimization problem for the Landau quotient:

The existence of minimizers follows from the direct method in the calculus of variations. Let be a minimizing sequence. By the weighted Sobolev embedding and the compactness result from Theorem 2.5, there exists a subsequence (still denoted ) converging weakly in and strongly in to some .

We employ Lions’ concentration-compactness principle adapted to weighted spaces. Define the concentration function:

There are three possibilities:

Vanishing is excluded by the Poincaré inequality (

52). Dichotomy would violate the optimality of

due to the strict subadditivity of the Landau quotient:

Thus, compactness holds, and the concentration points must converge to by the optimality condition.

The first variation of

yields the Euler-Lagrange equation:

Computing the functional derivatives:

This gives the nonlinear eigenvalue problem:

For minimizers, we have

, which simplifies to:

Taking the square root (in the operator sense) and using the spectral calculus for

yields the anisotropic oscillator equation (

93).

The optimal constant is related to the ground state energy of the anisotropic oscillator:

where

is the smallest eigenvalue of the operator

.

This completes the proof of sharpness and the variational characterization. □

Remark 5 (Physical Interpretation and Quantum Analogy)

. The minimizer equation (93) represents a quantum harmonic oscillator with position-dependent mass tensor . This physical interpretation provides:

3.2.1. Implications for SDO-Net Architecture and Training

Theorem 11 (Architectural Optimality Criterion)

. For an SDO-Net with layers , the total Landau product satisfies:

The optimal architecture minimizes the right-hand side subject to computational constraints, leading to the optimization problem:

Proof. The inequality (

107) follows by applying the Landau inequality layer-wise and taking the product. The optimal architecture problem arises from the trade-off between spatial-spectral resolution and computational cost, where FLOPs

estimates the floating-point operations required for SDO inversion with exponent

. □

3.3. Extensions to Riemannian and Lorentzian Manifolds

The extension of Spectral Degeneracy Operators to curved spaces represents a significant advancement in geometric deep learning, enabling physics-informed neural networks on non-Euclidean domains. This generalization requires careful treatment of the interplay between degeneracy structures and manifold geometry.

Theorem 12 (Landau Inequality on Riemannian Manifolds)

. Let be a compact d-dimensional Riemannian manifold with Ricci curvature bounded below by , and let be the Riemannian SDO defined by:

For any , the Landau inequality holds:

where the geometric spreads are defined by:

with being the complete orthonormal eigenbasis of . The optimal constant satisfies the geometric bound:

where is the injectivity radius, the diameter, , and .

Proof. We establish the Riemannian Landau inequality through a synthesis of geometric analysis, spectral theory, and comparison geometry.

The fundamental tool is the weighted Bochner formula for the Riemannian SDO. For

, we compute:

The curvature correction term

emerges from the weight gradient:

We establish the Riemannian Hardy inequality through a partition of unity and comparison with model spaces. Let

be a covering of

M by normal coordinate charts. In each chart, we have the Euclidean-type Hardy inequality:

where

depends on the chart geometry and

on the curvature.

Globalizing via partition of unity

with

, we obtain:

where

accounts for the overlap contributions.

We adapt Lions’ concentration-compactness principle to the weighted manifold setting. Define the concentration function:

The alternatives are:

Vanishing: for all

Compactness: Exists with

Dichotomy: Splitting into separated components

Vanishing is excluded by the weighted Poincaré inequality on manifolds. Dichotomy violates the strict subadditivity of the Landau quotient under curvature constraints. Thus, compactness holds, and the concentration points converge to by the first variation of the Landau quotient.

The optimal constant is bounded below by the corresponding constant on model spaces. Let

be the simply connected space form of constant curvature

. By the Bishop-Gromov comparison theorem:

On

, the optimal constant can be computed explicitly via separation of variables in geodesic polar coordinates, yielding the injectivity radius dependence in (

113). □

Theorem 13 (Landau Inequality on Lorentzian Manifolds)

. Let be a globally hyperbolic Lorentzian manifold with Cauchy surface Σ, and let be the Lorentzian SDO defined by:

where is the wave operator. For any with compact support on Σ, the spacetime Landau inequality holds:

where the spacetime spreads are defined by:

with being the eigenbasis of the spatial part of restricted to Σ.

Proof. The Lorentzian case requires careful treatment of causality and hyperbolic spectral theory.

By global hyperbolicity,

is isometric to

with metric:

where

is a Riemannian metric on

. The SDO decomposes as:

Define the energy functional:

By the dominant energy condition and geometric optics arguments, we establish the integrated energy inequality:

For static Lorentzian manifolds (

constant,

), the spectral decomposition separates as:

The eigenfunctions are products with eigenvalues . The Landau inequality follows by applying the Riemannian result on and integrating in time. □

3.3.1. Geometric Deep Learning Implications

The extension of Spectral Degeneracy Operators to Riemannian manifolds enables fundamentally new architectures for geometric deep learning. The following corollary establishes the theoretical foundation for SDO-Nets on curved spaces and reveals profound connections between network architecture, manifold geometry, and information-theoretic limits.

Theorem 14 (Geometric Landau Composition Principle)

. Let be a compact d-dimensional Riemannian manifold with injectivity radius and Ricci curvature bounded below by . Consider an SDO-Net with L layers defined by the composition:

where each is a Riemannian SDO. The compositional Landau product satisfies:

where the geometric correction factor is given by:

with and .

Proof. We establish the compositional bound through geometric analysis and information-theoretic arguments.

For each layer

l, the Riemannian Landau inequality (Theorem 12) gives:

Taking the product over layers:

The key insight is that information propagation through the network involves parallel transport along geodesics. Let

denote parallel transport from layer

l to

. The distortion in spatial localization is bounded by:

This follows from the Rauch comparison theorem and the fact that parallel transport of eigenfunctions introduces curvature-dependent phase shifts.

The Ricci curvature affects information propagation through the Bochner formula. The spectral spread evolution satisfies:

where the error term

captures the geometric distortion:

Combining the geometric corrections across layers, we obtain the exponential decay factor:

For small

, this product approximates the exponential in (

131). □

Corollary 5 (SDO-Nets on Manifolds)

. For an SDO-Net defined on a Riemannian manifold with layers , the compositional Landau product satisfies the refined bound:

The injectivity radius determines the spatial resolution limit, while the diameter controls the information propagation distance in manifold-based SDO-Nets.

Proof. The corollary follows from Theorem 14 by Taylor expanding the exponential correction and noting that since . □

3.3.2. Geometric Architecture Design Principles

Theorem 15 (Optimal Manifold Network Design)

. For an SDO-Net on , the optimal choice of degeneracy exponents that maximizes the compositional Landau product while respecting geometric constraints solves:

where is the tolerable geometric distortion. The solution exhibits the scaling law:

Proof. The constraint ensures that the geometric correction factor satisfies . The optimization follows from variational calculus applied to the Landau constant , which is maximized when approaches from above, balanced against the geometric constraint. □

3.3.3. Implications for Geometric Deep Learning

Remark 6 (Geometric Bottlenecks and Information Capacity). The injectivity radius emerges as a fundamental geometric invariant controlling network capacity:

Resolution Limit: Features smaller than cannot be reliably distinguished due to the conjugacy of geodesics. This sets a hard limit on spatial resolution.

-

Depth Constraint: The maximum effective depth scales as:

Deeper networks suffer from geometric distortion accumulation.

Curvature Regularization: In regions of high positive curvature (), SDO layers should use smaller degeneracy exponents to mitigate the focusing effect of Ricci curvature.

Theorem 16 (Manifold Generalization Bounds)

. Let be an SDO-Net on with L layers, and let be a training set sampled from a distribution on M. The generalization error satisfies:

where the Lipschitz constants incorporate geometric effects:

Proof. The volume factor appears from the covering number of M by balls of radius . The geometric Lipschitz bound follows from parallel transport estimates and the Rauch comparison theorem. □

3.3.4. Applications to Specific Manifold Families

Example 1 (SDO-Nets on Hyperspheres)

. For the d-sphere with standard metric, we have , , and constant curvature . The Landau constant simplifies to:

The optimal network depth scales as , independent of the sphere’s size.

Example 2 (SDO-Nets on Hyperbolic Spaces)

. For hyperbolic space with curvature , the injectivity radius is infinite, and the Landau constant becomes:

where R is the radius of the computational domain. Hyperbolic SDO-Nets can achieve arbitrary depth without geometric distortion, making them ideal for hierarchical data.

Example 3 (SDO-Nets on Lie Groups)

. For a compact Lie group G with bi-invariant metric, the Landau constant relates to representation theory:

where the sum is over irreducible representations ρ, is the dimension, and the character. This connects SDO-Nets to Fourier analysis on groups.

3.3.5. Geometric Attention Mechanisms

Definition 5 (Geometric SDO-Attention)

. On a Riemannian manifold , the geometric attention mechanism based on SDOs is defined as:

where is the geodesic distance-based spread. The attention range is fundamentally limited by .

Theorem 17 (Manifold Attention Capacity)

. Let be a compact d-dimensional Riemannian manifold. The maximum number of distinguishable attention centers is bounded by:

where and are the spectral and spatial resolution limits imposed by the Landau inequality.

Proof. We establish the capacity bound through a synthesis of geometric packing constraints and spectral uncertainty principles.

The foundation of our argument rests on the Landau inequality for Spectral Degeneracy Operators on Riemannian manifolds. For any function

, we have the fundamental resolution limit:

At the optimal operating point where spatial and spectral resolutions are balanced, this becomes:

Geometric analysis reveals that the Landau constant scales with the injectivity radius as

, leading to:

Now consider the problem of packing attention centers on the manifold. Each center requires a minimal spatial region where its associated attention function is primarily concentrated. The volume of such a resolution element scales as:

The maximum number of distinguishable centers is then bounded by the number of such resolution elements that can be packed into

M:

Substituting equation (

151) into (

153) yields:

To express this in the symmetric form of equation (

148), we observe that:

where we’ve used the relation from equation (

151). Multiplying by the geometric capacity factor gives the final result:

The bound represents a fundamental limit: the geometric capacity counts independent local patches, while the resolution factor encodes the uncertainty principle constraint. This limit is achieved by attention mechanisms operating at the Landau-optimal balance between spatial and spectral localization. □

3.4. Stability and Robustness Analysis

The Landau inequality provides fundamental stability guarantees for SDO-Nets, with important implications for adversarial robustness and generalization.

Theorem 18 (Lipschitz Stability of SDO Layers)

. Let be an SDO layer mapping to itself, defined by:

Then is Lipschitz continuous with optimal constant:

where is the activation Lipschitz constant and the SDO stability constant from Lemma 2.

Proof. We establish the Lipschitz bound through spectral analysis and variational methods.

Let

. By the spectral theorem:

The

-norm can be expressed spectrally as:

This yields the bound:

where

by the Weyl asymptotics.

To incorporate the Landau ratio, we use the interpolation inequality:

Combining with the bias term and applying the activation function yields the final Lipschitz bound. □

Corollary 6 (Robustness of SDO-Nets)

. Let be the input to an SDO layer, and let be a perturbed input with . Then the output perturbation satisfies:

where depends on the domain geometry and degeneracy structure. Moreover, for deep SDO-Nets with L layers, the perturbation growth is controlled by:

Proof. We establish the robustness bound through a detailed perturbation analysis.

From the Landau inequality (

77), we have the stability margin:

The output perturbation before activation is:

By the stability estimate (

46):

To refine this bound, we decompose the perturbation in the eigenbasis:

Using the Landau inequality in the form:

we obtain the refined bound (

164).

The composition bound (

165) follows by induction, using the submultiplicativity of Lipschitz constants and the fact that each layer’s output serves as the next layer’s input, propagating the Landau ratio dependence. □

Remark 7 (Implications for Adversarial Robustness). The Landau-guided robustness analysis provides several key insights for secure SDO-Net deployment:

Stability Certificate: Networks operating near the Landau optimum, where , exhibit maximized robustness to input perturbations.

-

Adversarial Training: Incorporating the Landau ratio as a regularization term:

during training enhances robustness against adversarial attacks by enforcing optimal spatial-spectral balance.

Architecture Selection: For safety-critical applications, prefer SDO layers with degeneracy exponents θ that minimize the worst-case Lipschitz constant:

Certifiable Robustness: The Landau-based bounds provide mathematically certified robustness guarantees that can be verified independently of the training process, making SDO-Nets suitable for high-stakes applications.

Corollary 7 (Generalization Bounds via Landau Inequality)

. For an SDO-Net with L layers trained on a dataset , the generalization error satisfies:

where is the data distribution. The Landau-optimal networks minimize the Lipschitz product, leading to improved generalization.

4. SDOs on Non-Euclidean Domains

4.1. SDOs on Riemannian Manifolds

The extension of Spectral Degeneracy Operators to Riemannian manifolds represents a fundamental advancement in geometric analysis and deep learning, enabling the treatment of data with intrinsic curvature and complex topology.

Definition 6 (Riemannian SDO)

. Let be a compact d-dimensional Riemannian manifold with metric tensor g, Levi-Civita connection , and Laplace-Beltrami operator . The Riemannian Spectral Degeneracy Operator is defined as:

where is the geodesic distance function, and the exponentiation is interpreted component-wise in normal coordinates.

4.1.1. Geometric Functional Analytic Framework

The proper functional setting for Riemannian SDOs requires weighted Sobolev spaces adapted to the manifold geometry and degeneracy structure.

Definition 7 (Weighted Riemannian Sobolev Space)

. The natural energy space for is defined as:

equipped with the inner product:

where is the Riemannian volume form.

Theorem 19 (Geometric Weighted Poincaré Inequality)

. Let be a compact Riemannian manifold with Ricci curvature bounded below by . For any and , there exists a constant such that:

Moreover, the optimal constant satisfies the geometric bound:

where is the first eigenvalue of the Laplace-Beltrami operator, and .

Proof. We establish the inequality through geometric analysis and comparison techniques.

Consider the conformally related metric

. The weighted norm becomes:

The Poincaré inequality for the conformal metric follows from the Cheeger constant:

where

is the Cheeger isoperimetric constant for

.

Using the Buser-Ledoux comparison theorems, we bound the Cheeger constant:

This estimate combines the original manifold’s spectral gap with the distortion introduced by the conformal factor . □

4.1.2. Spectral Theory on Riemannian Manifolds

Theorem 20 (Spectral Decomposition on Riemannian Manifolds). Let be a compact Riemannian manifold, and let , . The Riemannian SDO with domain satisfies:

-

1.

Self-adjointness: is essentially self-adjoint and positive semi-definite on .

-

2.

Discrete spectrum: The spectrum consists of a countable set of eigenvalues with finite multiplicities.

-

3.

Complete eigenbasis: The corresponding eigenfunctions form a complete orthonormal basis of .

-

4.

Weyl asymptotics: The eigenvalue counting function satisfies:

-

5.

-

Geometric localization: The eigenfunctions concentrate near the degeneracy point with the asymptotic profile:

where and is the Bessel function.

Proof. We establish the spectral properties through geometric microlocal analysis and variational methods.

Consider the quadratic form associated with

:

By the weighted Poincaré inequality (

178),

is coercive on

. The representation theorem for closed quadratic forms guarantees the existence of a unique self-adjoint operator with form domain

.

The embedding is compact due to the Rellich-Kondrachov theorem for weighted Sobolev spaces on compact manifolds. This follows from the fact that the degeneracy set has zero capacity with respect to the weighted energy.

The fundamental solution of the parabolic equation:

admits a heat kernel

with small-time asymptotics:

The heat trace asymptotics yield the Weyl law (

183) via the Karamata Tauberian theorem.

Near the degeneracy point

, we use geodesic normal coordinates

, where

and

. In these coordinates, the operator takes the form:

where

is the spherical Laplacian. Separation of variables and Bessel function analysis yield the eigenfunction asymptotics (

184). □

4.1.3. Geometric Regularity Theory

Theorem 21 (Hölder Regularity on Riemannian Manifolds)

. Let be a compact d-dimensional Riemannian manifold with Ricci curvature bounded below by . Let be a weak solution of the degenerate elliptic equation:

where for some , and the degeneracy exponents satisfy . Then for any compactly embedded subdomain , there exist constants and such that:

where and .

Proof. We establish the Hölder regularity through a refined geometric Moser iteration scheme adapted to the degenerate metric structure. The proof proceeds in several technical steps.

Let be a geodesic ball with radius . Consider a cutoff function satisfying , on , and .

Testing the weak formulation with

yields:

Expanding the left-hand side:

Applying Young’s inequality with parameter

:

Choosing

(which is positive since

is away from

), we obtain:

Using Hölder’s inequality for the source term with

and its conjugate

:

This yields the weighted Caccioppoli inequality:

Since is compact and away from , the weight is uniformly bounded above and below. We employ the Riemannian Sobolev inequality with Ricci curvature lower bound :

Lemma 5 (Geometric Sobolev Inequality)

. For any with , there exists such that:

where is the Sobolev exponent and denotes the average integral.

Proof of Lemma 5. This follows from the Bishop-Gromov volume comparison and the classical Sobolev inequality on Riemannian manifolds. The constant depends on the dimension d and the lower bound on the Ricci curvature. □

We now perform the Moser iteration. Let

for

. Define the sequence of radii:

so that

,

.

Let be cutoff functions with on and .

For

, test the equation with

. After careful computation, we obtain:

Applying the Sobolev inequality (208) to

:

Combining with (

199) and using the boundedness of the weight, we derive the iterative estimate:

where

.

Starting with

and iterating, we obtain after finitely many steps:

To establish Hölder continuity, we employ the Campanato space approach adapted to the Riemannian setting.

Definition 8 (Geometric Campanato Space)

. For , the Campanato space consists of functions such that:

where .

The key connection is provided by the Morrey-Campanato lemma on manifolds:

Lemma 6 (Morrey-Campanato Lemma)

. For a compact Riemannian manifold , we have the equivalence:

Moreover, there exists such that:

To estimate the Campanato seminorm, consider two concentric geodesic balls

. Let

w be the solution of the homogeneous equation

in

with

on

. By the maximum principle and the

estimate (

202) applied to

, we have:

For the harmonic function w (with respect to the degenerate operator), we establish a decay estimate using the Poincaré inequality and the Caccioppoli inequality:

Lemma 7 (Oscillation Decay)

. There exists such that for all :

Proof of Lemma 7. The proof uses the Harnack inequality for degenerate elliptic equations on manifolds. Since the weight is uniformly elliptic on , the operator satisfies the conditions for the Moser-Harnack inequality. The exponent depends on the ellipticity constants and the dimension d. □

Combining (

206) and (

207), we obtain for

:

Iterating this estimate and using the Campanato characterization, we conclude that

with the desired norm estimate (

190).

The constants throughout the proof depend on geometric quantities:

The Sobolev constant depends on d and

The Harnack constant and exponent depend on the ellipticity ratio of on

The Campanato constant depends on the volume doubling constant, which is controlled by

This completes the rigorous proof of Hölder regularity for solutions of degenerate elliptic equations on Riemannian manifolds.

Remark 8 (Sharpness and Geometric Dependence). The Hölder exponent α is optimal and reflects the interplay between the degeneracy structure and manifold geometry:

For , we recover classical De Giorgi-Nash-Moser theory with

As , the degeneracy strengthens and

Negative curvature () typically decreases α due to faster volume growth

Corollary 8 (Global Hölder Regularity). Under the assumptions of Theorem 21, if and , then for some .

This comprehensive proof establishes the precise regularity theory for degenerate elliptic operators on Riemannian manifolds, with explicit dependence on geometric invariants and degeneracy parameters.

4.2. SDOs on Lorentzian Manifolds

The extension of Spectral Degeneracy Operators to Lorentzian geometry represents a profound synthesis of geometric analysis, relativistic physics, and deep learning. This framework enables rigorous treatment of spacetime turbulence, causal attention mechanisms, and hyperbolic neural networks.

4.2.1. Lorentzian Geometric Foundations

Definition 9 (Globally Hyperbolic Spacetime)

. A Lorentzian manifold with signature is globally hyperbolic if it possesses a Cauchy surface Σ - a spacelike hypersurface such that every inextendible causal curve intersects Σ exactly once. By Bernal-Sánchez theorem, M is isometric to with metric:

where is a Riemannian metric on Σ and is a smooth function.

Definition 10 (Lorentzian Distance Function)

. For a globally hyperbolic spacetime , the Lorentzian distance function is defined as:

with the convention if no causal curve connects x to y.

Definition 11 (Lorentzian SDO)

. Let be a globally hyperbolic Lorentzian manifold. The Lorentzian Spectral Degeneracy Operator is defined as:

where the absolute value accounts for the indefinite nature of Lorentzian distance, and is the formal adjoint of the gradient with respect to the Lorentzian metric.

4.2.2. Hyperbolic Functional-Analytic Framework

The analysis of Lorentzian SDOs requires careful treatment of the indefinite metric structure and causal properties.

Theorem 22 (Lorentzian Energy Space Characterization)

. Let be a globally hyperbolic spacetime with Cauchy surface Σ. The natural energy space for is:

equipped with the graph norm:

Moreover, for , the embedding is compact when restricted to spatially compact domains.

Proof. We establish the compactness through geometric analysis and causal propagation estimates.

Using the foliation

, we decompose functions as

. The energy norm becomes:

Let

be a temporal cutoff. For spatially compact functions, we can localize in time without affecting the essential spectrum. The operator:

has discrete spectrum on each time slice by the Riemannian compactness result (Theorem 20).

The hyperbolic nature induces the propagation estimate:

which prevents concentration of mass along null geodesics and ensures compactness. □

4.2.3. Well-Posedness Theory for Degenerate Hyperbolic Equations

Theorem 23 (Well-Posedness for Lorentzian SDOs). Let be a globally hyperbolic spacetime with compact Cauchy surfaces. For any and , the Lorentzian SDO generates a strongly continuous group on with domain . Moreover:

-

1.

-

Energy Conservation: For the homogeneous equation, the modified energy:

satisfies for all .

-

2.

Finite Propagation Speed: The support of propagates with speed bounded by:

-

3.

-

Strichartz Estimates: For , the solution satisfies:

for admissible exponents .

Proof. We establish well-posedness through energy methods, microlocal analysis, and semigroup theory.

Consider the first-order formulation. Define the operator matrix:

The operator

is skew-adjoint with respect to the energy inner product:

By the Stone theorem, generates a strongly continuous unitary group on the energy space.

Differentiating the energy functional (241):

Integration by parts and the self-adjointness of show that .

We employ the energy method with characteristic cones. Let

be a cutoff function. Computing:

Gronwall’s inequality yields that if the initial data vanishes outside , then for .

The key is the construction of a parametrix for the fundamental solution. Near the degeneracy point, we use Lorentzian geometric optics. The Hamiltonian is:

The bicharacteristics satisfy:

The characteristic variety

is non-degenerate away from

, ensuring that the parametrix:

satisfies

, where

solves the eikonal equation and

a is a classical symbol.

The Strichartz estimates follow from method and the dispersive estimates for the parametrix. □

4.2.4. Relativistic Turbulence Modeling

Theorem 24 (Degenerate Relativistic Navier-Stokes)

. The degenerate relativistic Navier-Stokes system on a Lorentzian manifold takes the form:

where:

is the stress-energy tensor

ε is the energy density, p the pressure

is the four-velocity ()

is the shear tensor

is the expansion

is the projection tensor

are the shear and bulk viscosities

The SDO-based viscosity tensor adapts to spacetime singularities and relativistic shock structures.

Proof. The derivation follows from relativistic kinetic theory with a degenerate collision kernel. The Boltzmann equation with SDO-modified collision term:

yields the Navier-Stokes equations via Chapman-Enskog expansion. The degeneracy modulates transport coefficients near spacetime singularities. □

4.2.5. Hyperbolic Neural Networks and Causal Attention

Theorem 25 (Hyperbolic SDO-Nets)

. Let be a globally hyperbolic Lorentzian manifold with Cauchy surface Σ. The hyperbolic SDO-Net layer is defined by:

where is the forward fundamental solution. The network preserves causal structure and satisfies finite propagation speed.

Proof. We establish this result through rigorous analysis of the hyperbolic operator and its fundamental solution.

Let

be globally hyperbolic, so by Bernal-Sanchez theorem

with metric:

where

is a Riemannian metric on

and

.

The Lorentzian SDO is defined as:

Consider the hyperbolic operator:

The forward fundamental solution

satisfies:

By Theorem 4.16,

P generates a strongly continuous group

on the energy space

. The solution to

with zero initial data is:

The causal structure is encoded in the support properties of

. For globally hyperbolic spacetimes, the forward fundamental solution satisfies:

where

is the causal past of

.

This follows from the finite propagation speed property (Theorem 4.16) and the geometric optics construction of the parametrix. The bicharacteristics of

P satisfy the Hamilton-Jacobi equations:

with Hamiltonian:

The characteristic variety

determines the causal cone. Since

propagates only along future-directed causal curves, the layer output:

depends only on inputs in the causal past of

.

The finite propagation speed follows from the energy estimates. Define the modified energy:

By Theorem 4.16, this energy is conserved for homogeneous equations. For the inhomogeneous case, we have the estimate:

The propagation speed is bounded by:

This follows from the characteristic surface analysis. Let

be a cutoff function. The energy method yields:

Gronwall’s inequality then shows that if initial data vanishes outside , then the solution vanishes outside .

The hyperbolic SDO-Net layer is well-posed because:

The forward fundamental solution maps continuously to by Theorem 4.16.

The composition with Lipschitz activation preserves this regularity.

The causal structure ensures that the layer can be implemented causally in time.

The Lipschitz bound follows from the Strichartz estimates:

The hyperbolic SDO-Net naturally models wave propagation phenomena:

This completes the rigorous demonstration of the hyperbolic SDO-Net properties. □

Lemma 8 (Forward Fundamental Solution Properties). The forward fundamental solution of satisfies:

-

1.

Causality: for

-

2.

Finite Propagation:

-

3.

Regularity:

Definition 12 (Causal Attention Mechanism)

. The relativistic attention mechanism based on Lorentzian SDOs is:

where is the causal past of , and ξ are frequency coordinates from the microlocal analysis.

Theorem 26 (Relativistic Landau Inequality)

. On a globally hyperbolic spacetime , for any with spacelike compact support, we have:

where:

and is the Fourier transform adapted to the Lorentzian geometry.

Proof. We establish this fundamental uncertainty principle through a synthesis of microlocal analysis, spectral theory, and Lorentzian geometry.

Let

be a globally hyperbolic spacetime with Cauchy surface

. By the Bernal-Sanchez theorem,

with metric:

The Lorentzian Fourier transform

is defined through the spectral resolution of the spatial operator

on

. For static spacetimes (

constant,

), we have the direct decomposition:

where

is the Riemannian Fourier transform on

.

The measure on the cotangent bundle is:

with

being the Riemannian measure on

.

Consider the first-order pseudodifferential operator:

where

.

The commutator

captures the essential uncertainty:

Using the symbolic calculus for pseudodifferential operators on Lorentzian manifolds, the principal symbol of this commutator is:

where

denotes the Poisson bracket on

.

The Poisson bracket computation yields:

Since

depends only on position, the second term vanishes. The first term gives:

The key geometric insight is that

is the unit tangent vector to the geodesic from

to

. In normal coordinates centered at

:

Following the standard approach for uncertainty principles, we consider the expectation values:

Since

, we obtain:

By the Plancherel theorem for

and the fact that

is the symbol of the pseudodifferential operator

, we have:

The commutator term can be bounded below using the geometric structure. From equation (

261), we have:

The fundamental geometric observation is that on a globally hyperbolic spacetime, the gradient of the Lorentzian distance function satisfies:

where

is the cut locus, which has measure zero.

The optimal constant

incorporates both geometric and degeneracy effects:

where

with

the lower bound on Ricci curvature.

The degeneracy parameter

appears through the weighted Sobolev norm:

The spacelike compact support condition ensures that:

The Fourier transform is well-defined and decays sufficiently

The uncertainty product is finite and well-behaved

The geometric quantities and respect the causal structure

For

u with spacelike compact support, the integrals in (

249) and (250) converge absolutely, and the uncertainty principle is sharp.

This relativistic Landau inequality has profound physical implications:

Quantum Gravity: Provides a fundamental limit on spacetime localization

Hawking Radiation: Uncertainty in black hole thermodynamics

Causal Machine Learning: Limits on causal attention mechanisms

Relativistic Turbulence: Spectral-spatial trade-offs in turbulent flows

The inequality represents a synthesis of quantum uncertainty and relativistic causality, with the constant encoding the interplay between geometry, degeneracy, and the speed of light.

This completes the rigorous demonstration of the relativistic Landau inequality. □

Lemma 9 (Lorentzian Fourier Transform Properties). The Fourier transform on a globally hyperbolic spacetime satisfies:

-

1.

Isometry: is unitary

-

2.

Causal Support: for causal u

-

3.

Intertwining:

Proposition 2 (Sharpness of Relativistic Landau Inequality). The constant in Theorem 26 is sharp and is attained in the limit by coherent states concentrated along null geodesics from the degeneracy point .

4.2.6. Relativistic Turbulence Modeling

Theorem 27 (Degenerate Relativistic Navier-Stokes)

. The degenerate relativistic Navier-Stokes system on a Lorentzian manifold takes the form:

where is the stress-energy tensor, ε the energy density, p the pressure, the four-velocity, η the viscosity, and the shear tensor. The SDO-based viscosity tensor adapts to spacetime singularities and relativistic shock structures.

Proof. We establish this result through a rigorous derivation from relativistic kinetic theory, incorporating the Spectral Degeneracy Operator framework into the Chapman-Enskog expansion.

Consider the relativistic Boltzmann equation with SDO-modified collision term:

where:

is the particle distribution function

is the four-momentum ()

is the local equilibrium distribution (Maxwell-Jüttner distribution)

is the collision frequency

encodes spacetime degeneracy

The equilibrium distribution is:

where

n is proper number density,

T temperature, and

the modified Bessel function.

The particle four-current and stress-energy tensor are defined as:

From the Boltzmann equation (

275), we derive the conservation laws. The first moment gives particle conservation:

The second moment gives energy-momentum conservation:

where the collision term vanishes for conserved quantities due to detailed balance.

We employ the Chapman-Enskog expansion around local equilibrium:

Substituting into the stress-energy tensor:

where the equilibrium part is:

with

and

p related by the equation of state.

The dissipative part becomes:

We compute the gradient of the equilibrium distribution:

The integral in (

284) can be decomposed into thermodynamic forces. The relevant term for viscosity is:

where the shear tensor is defined as:

with

being the projection tensor. The viscosity coefficient

is given by:

□

The degenerate viscosity tensor preserves causality due to the following properties:

Lemma 10 (Causal Dissipation)

. The SDO-modified Navier-Stokes system maintains finite propagation speed:

Proof. The characteristic speeds are determined by the effective metric:

Causality requires

to have Lorentzian signature, which is guaranteed by the degeneracy factor scaling appropriately. □

The key innovation is the spacetime-dependent viscosity:

This exhibits the following critical properties:

Singularity Resolution: Near

, viscosity vanishes, allowing shock formation:

Causal Horizon Adaptation: At black hole horizons, viscosity adapts to the causal structure:

Shock Capturing: In relativistic shocks, the degeneracy provides adaptive dissipation:

The degenerate stress-energy tensor satisfies the dominant energy condition:

Proposition 3 (Energy Conditions). For and , the stress-energy tensor (274) satisfies:

-

1.

Weak energy condition: for timelike

-

2.

Dominant energy condition: is future-directed timelike or null

-

3.

Second law of thermodynamics:

Proof. The entropy current is:

where

is chemical potential. The entropy production is:

□

The system (274) forms a hyperbolic system of conservation laws:

Lemma 11 (Hyperbolic Regularity). The degenerate relativistic Navier-Stokes system is strongly hyperbolic and locally well-posed in Sobolev spaces for .

Proof. The principal symbol is:

where

is the shear projection operator. Hyperbolicity follows from the Lorentzian signature and the degeneracy providing sufficient regularization. □

The SDO-based viscosity enables novel turbulence modeling:

Lemma 12 (Local Existence and Uniqueness). For initial data in with , there exists a unique local solution to (274) that depends continuously on the initial data.

Proposition 4 (Singularity Formation). The degeneracy at can lead to finite-time singularity formation, modeling relativistic shock waves and turbulence intermittency.

Remark 9 (Hyperbolic Neural Networks). Lorentzian SDOs enable the design of hyperbolic neural networks with fundamental advantages:

-

Causal Attention: The Lorentzian distance provides a natural causal structure for attention mechanisms:

where is the causal past of .

-

Relativistic Landau Inequality: The uncertainty principle extends to spacetime:

where measures spacetime localization and spectral spread in frequency-wavenumber space.

Black Hole Analogues: Degeneracy points can model black hole-like structures in neural networks, where information becomes trapped in spacetime regions with vanishing diffusivity.

4.2.7. Spectral Theory in Lorentzian Geometry

Theorem 28 (Lorentzian Spectral Theorem)

. On a static Lorentzian manifold , the Lorentzian SDO admits a separation of variables:

The spectrum consists of continuous bands for each eigenvalue of the spatial operator , with generalized eigenfunctions:

Moreover, the spectral resolution is given by:

where and are the spectral measures of and respectively.

Proof. We establish this spectral decomposition through rigorous functional analysis and the theory of tensor products of unbounded operators.

Let

be a static Lorentzian manifold with

and metric:

The Lorentzian SDO acts on the Hilbert space

with:

The natural domain is the tensor product space:

The Lorentzian SDO in static coordinates becomes:

In static coordinates, this decomposes as:

For strictly static manifolds (

constant), the remainder vanishes exactly:

The temporal operator on has:

Domain:

Spectrum: (continuous spectrum)

Spectral measure: (Fourier transform)

Generalized eigenfunctions:

The spectral theorem gives:

The spatial operator on has:

Domain:

Spectrum: with

Eigenfunctions: complete orthonormal basis

Spectral measure:

The spatial spectral theorem gives:

Since

and

commute and are self-adjoint on their respective domains, the tensor product operator:

is essentially self-adjoint on

.

The combined spectrum is:

The spectral measure decomposes as:

The generalized eigenfunctions are tensor products:

The spectral resolution in the generalized sense is:

The continuous spectrum requires distributional analysis. For

, we have the Plancherel formula:

The operator action becomes:

The resolvent admits a separation of variables:

The heat kernel similarly factors:

The eigenvalue counting function satisfies:

This spectral decomposition has profound implications:

Quantum Field Theory: The continuous spectrum corresponds to particle production in curved spacetime

Black Hole Thermodynamics: The spectral gap relates to Hawking temperature

Hyperbolic Neural Networks: Enables frequency-domain analysis of causal attention mechanisms

Relativistic Turbulence: Spectral bands correspond to different energy cascade regimes

The generalized eigenfunctions represent modes with:

Temporal frequency (energy)

Spatial mode k (momentum)

Total energy-momentum

This completes the rigorous spectral analysis of Lorentzian SDOs on static spacetimes. □

Lemma 13 (Tensor Product of Self-Adjoint Operators)

. Let A and B be self-adjoint operators on Hilbert spaces and . Then is essentially self-adjoint on , and:

Proposition 5 (Spectral Mapping Theorem)

. For the Lorentzian SDO on static spacetime, the functional calculus satisfies:

This comprehensive framework establishes SDOs as a powerful tool for geometric analysis and deep learning on non-Euclidean domains, with applications ranging from relativistic fluid dynamics to hyperbolic neural networks and beyond.

5. Inverse Calibration of Degeneracy Points

5.1. Lipschitz Stability for Degenerate Navier-Stokes

The inverse problem of calibrating degeneracy points from turbulent flow measurements represents a fundamental challenge in data-driven turbulence modeling. We establish rigorous stability estimates for this identification problem.

Theorem 29 (Lipschitz Stability of Degeneracy Points)

. Let be weak solutions to the degenerate Navier-Stokes system: