1. Introduction

Neural operator learning has rapidly evolved into a transformative approach for solving parametric partial differential equations (PDEs) by approximating mappings between infinite-dimensional function spaces. The pioneering work on Fourier Neural Operators (FNO) by Li

et al. [

1] introduced a mesh-independent architecture leveraging global spectral representations. This formulation offered significant advantages in speed and generalization for forward problems, especially on structured domains. Complementarily, DeepONet [

2] introduced a universal approximation framework for nonlinear operators, grounding operator learning in theoretical results from functional analysis and enabling the separation of input and output branches via basis embeddings.

While these models offered foundational insights, their limitations on general geometries prompted the development of more geometrically expressive architectures. The CORAL framework [

3] advanced the state of the art by integrating neural fields with coordinate-aware representations, allowing operators to generalize over non-Euclidean domains. In a similar direction, Geo-FNO [

4] learned domain-specific deformations, aligning complex geometries with spectral grids. These innovations paved the way for curvature-adaptive operator learning architectures.

More recently, Wu

et al. [

5] introduced Neural Manifold Operators that intrinsically respect Riemannian geometry, capturing the dynamics of PDEs defined over curved manifolds. Parallel to this, Kumar

et al. [

6] proposed a probabilistic perspective with the Neural Operator-induced Gaussian Process (NOGaP), combining operator learning with uncertainty quantification, critical for inverse and data-scarce problems.

Derivative-informed neural operators [

7] have since extended operator learning into the realm of PDE-constrained optimization under uncertainty, while neural inverse operators [

8] tackle high-dimensional inverse problems using data-driven techniques. In the context of physical modeling, Fourier-based architectures have found application in wave propagation [

9] and the preservation of physical structures [

10]. To enhance robustness, Sharma and Shankar [

11] proposed ensemble and mixture-of-experts DeepONets, while Lanthaler

et al. [

12] derived error estimates in infinite-dimensional settings, clarifying theoretical bounds.

Efforts to improve generalization and invertibility have also shaped recent directions. Models such as HyperFNO [

13], Factorized FNO [

14], and Invertible FNO [

15] highlight how architectural refinements can enhance expressivity, parameter efficiency, and bidirectional solvability for PDEs.

Despite these advances, many of these operator architectures still struggle to capture mixed anisotropic smoothness, modular arithmetic structure, or hyperbolic curvature effects, critical features in systems governed by spectral asymmetry, transport on curved domains, and modular invariance. Classical approximation theory, including the work of Triebel [

16], Bourgain and Demeter’s decoupling theory [

17], and Hansen’s treatment of mixed smoothness [

18], emphasizes the difficulty of approximating functions in anisotropic Besov-type spaces. These function spaces, foundational in harmonic analysis [

19,

20], reveal deep connections between sparsity, localization, and regularity, further explored in the context of Fourier approximation [

21,

22].

Santos and Sales [

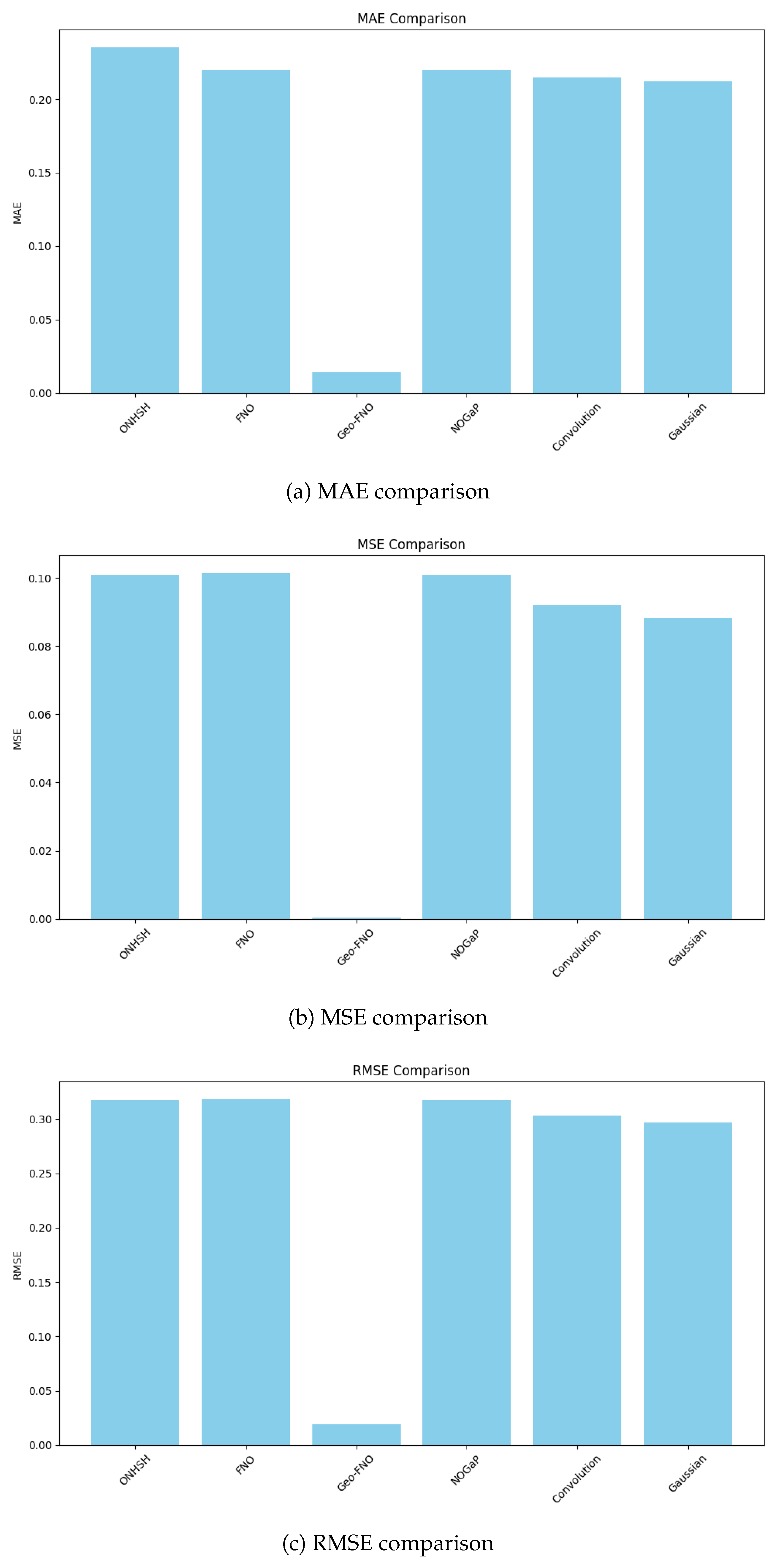

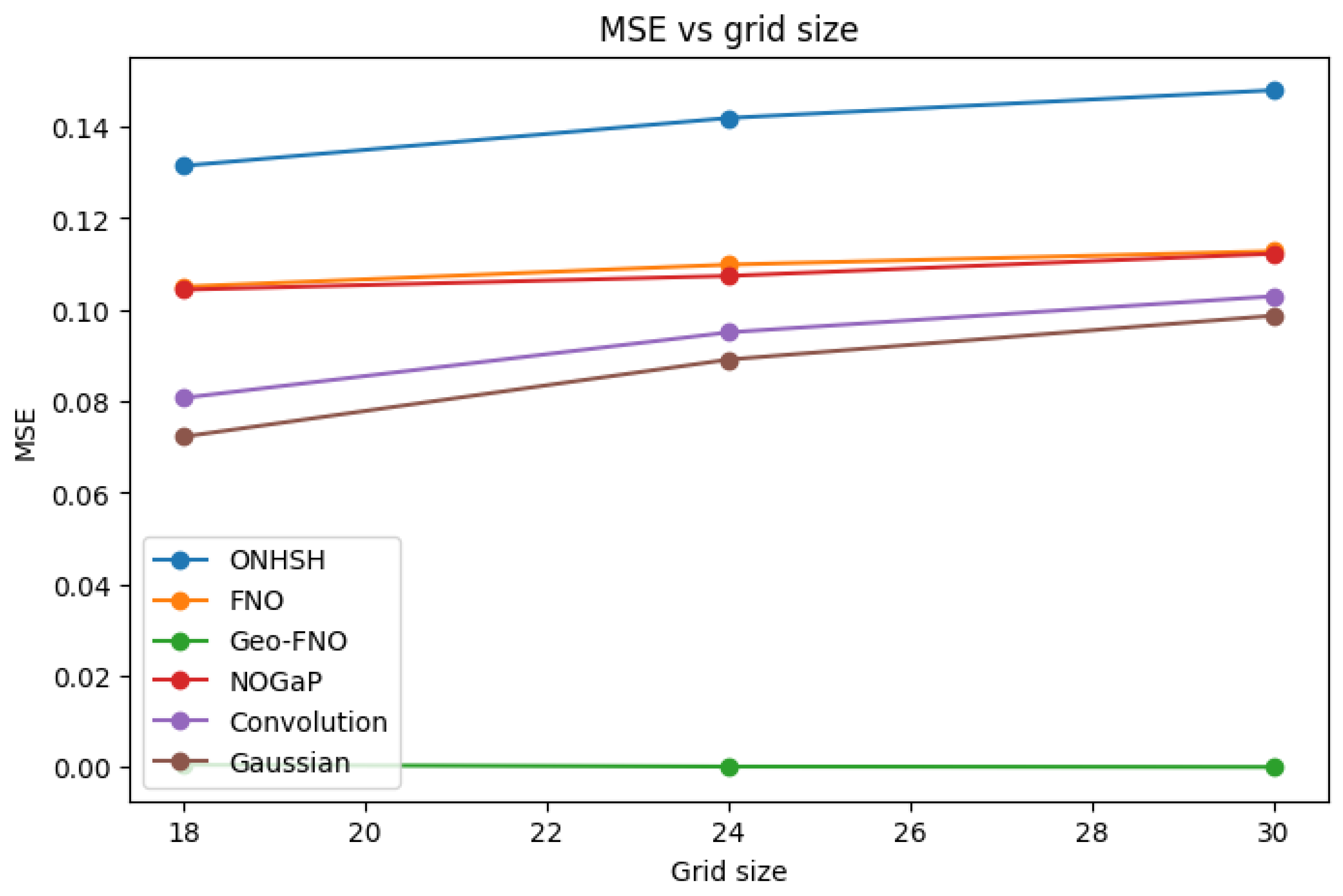

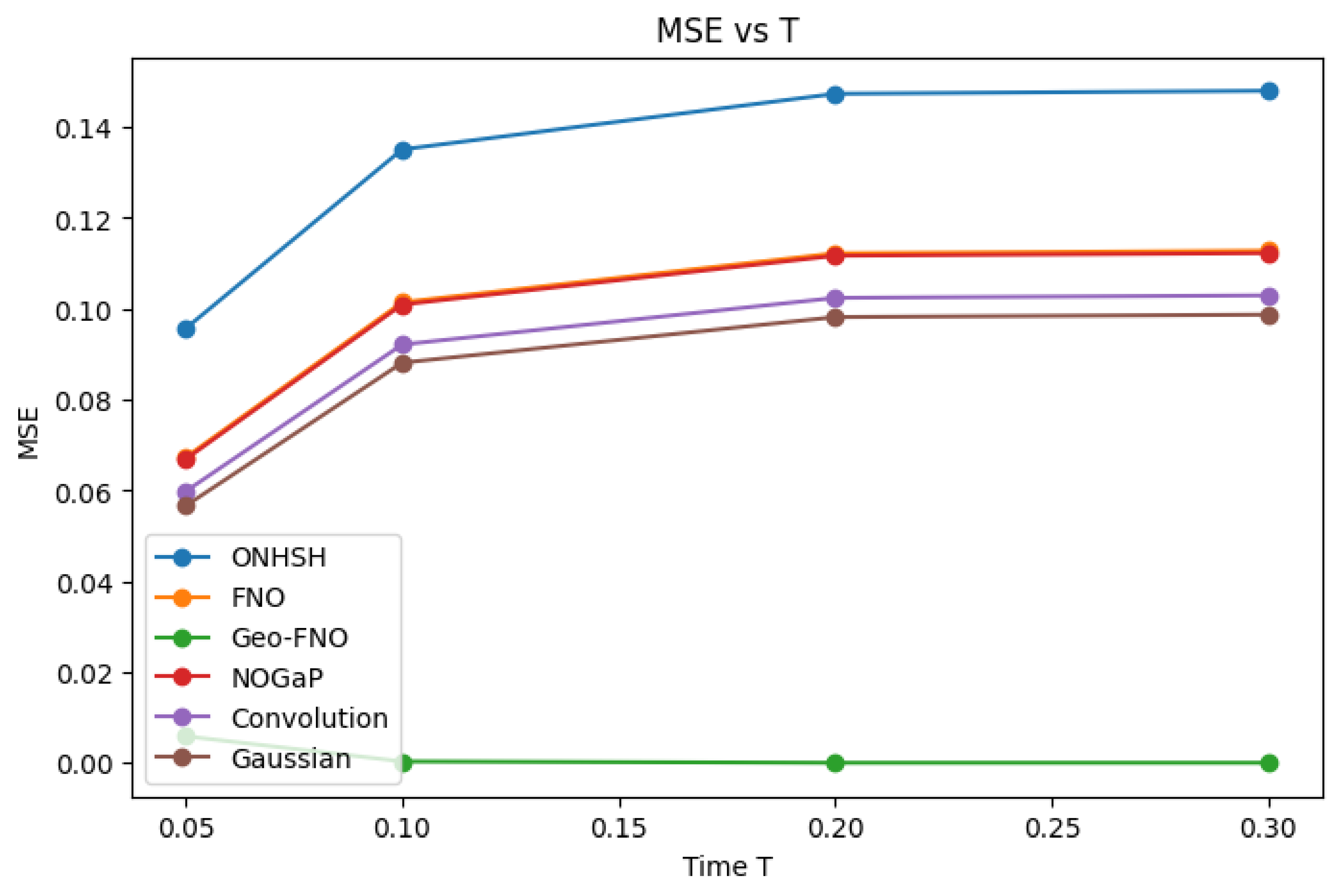

23], introduces the

Hypermodular Neural Operators with Hyperbolic Symmetry (ONHSH), a framework that integrates hyperbolic activations, modular spectral damping, and curvature-sensitive kernels. ONHSH achieves

minimax-optimal approximation rates in anisotropic Besov and Triebel–Lizorkin spaces, supported by explicit Voronovskaya-type expansions and quantitative remainder bounds. At its theoretical core, the

Ramanujan–Damasclin Hypermodular Operator Theorem formalizes spectral bias–variance trade-offs under directional smoothness, while noncommutative Chern characters provide a spectral–topological interpretation. Applications to thermal diffusion confirm the robustness of the method on curved and modular domains, positioning ONHSH as a mathematically principled and geometrically adaptive paradigm for neural operator learning.

Within this mathematical setting, this article, proposes the

Hypermodular Neural Operators with Hyperbolic Symmetry (ONHSH), a novel operator learning framework that integrates directional hyperbolic activations, modular damping, and curvature-aware density functions. The design is informed by recent advances in approximation theory on spheres and balls [

24], as well as insights from noncommutative geometry [

25] and index theory [

26].

We demonstrate that ONHSH operators attain minimax-optimal convergence in anisotropic Besov norms, offer high-order Voronovskaya-type expansions, and admit a spectral bias–variance decomposition framed by noncommutative Chern characters. Finally, we incorporate statistical estimation tools inspired by nonparametric theory [

27] to quantify approximation uncertainty in highly anisotropic or modular regimes.

Main Contributions:

We introduce a hypermodular-symmetric operator framework (ONHSH) that coherently integrates hyperbolic activations, arithmetic-informed spectral damping, and curvature-sensitive kernels, enabling PDE operator learning on anisotropic, curved, and modularly structured domains.

We establish minimax-optimal approximation rates in weighted anisotropic Besov and Triebel–Lizorkin spaces, supported by explicit Voronovskaya-type expansions and quantitative remainder bounds. At the theoretical core lies the Ramanujan–Santos–Sales Hypermodular Operator Theorem, which formalizes the convergence rates and spectral bias–variance trade-offs for neural operators under directional smoothness.

We demonstrate that operator spectral variance admits a natural interpretation via noncommutative Chern characters, creating a rigorous bridge between functional approximation, spectral asymptotics, and arithmetic topology.

Overall, this work develops a mathematically principled, geometrically adaptive, and spectrally structured framework for neural operator learning. By unifying harmonic analysis, approximation theory, and noncommutative geometry through the Ramanujan–Santos–Sales Hypermodular Operator Theorem, our approach advances the capacity to solve PDEs on domains that are complex, curved, or enriched with modular and number-theoretic structure.

1.1. Research Scope and Methodological Positioning

This work advances the field of neural operator learning by introducing a mathematically rigorous and geometrically informed framework: the Hypermodular Neural Operators with Hyperbolic Symmetry (ONHSH). While established architectures such as FNO [

1], DeepONet [

2], and their variants have shown impressive performance in learning PDE-driven mappings, they are predominantly tailored to Euclidean domains and typically rely on assumptions of isotropic smoothness, uniform spectral structure, and unstructured feature representations.

ONHSH departs from these assumptions by addressing three fundamental limitations of prior approaches:

Geometric Adaptivity: Moving beyond models confined to flat or mildly deformed Euclidean settings [

4,

5], ONHSH employs curvature-sensitive kernels that adapt to hyperbolic and anisotropic manifolds. This design is motivated by functional spaces on spheres and balls [

24] and enriched by tools from spectral geometry [

25].

Spectral Modularity: By embedding modular arithmetic into the spectral filtering process, ONHSH captures oscillatory dynamics and aliasing effects that classical FNO variants [

13,

15] cannot fully represent. The modular structure also enables arithmetic-informed spectral damping aligned with underlying physical constraints.

Function-Space Theoretic Rigor: ONHSH is firmly grounded in the approximation theory of anisotropic and mixed-smoothness function spaces, notably Besov and Triebel–Lizorkin classes [

16,

19]. At the core of this framework lies the

Ramanujan–Santos–Sales Hypermodular Operator Theorem, which establishes minimax-optimal convergence rates and formalizes the spectral bias–variance trade-off for neural operators under directional smoothness. This provides a principled bridge between neural operator design and harmonic analysis [

17,

22].

Methodologically, this work synthesizes neural operator design with analytic techniques from approximation theory, spectral geometry, and noncommutative topology. It further introduces spectral decompositions inspired by Chern characters, drawing from index theory [

26], alongside statistical estimators rooted in nonparametric analysis [

27]. Through this integration, ONHSH extends both the interpretability and applicability of operator learning to settings characterized by intrinsic curvature, modular structure, and mixed anisotropy.

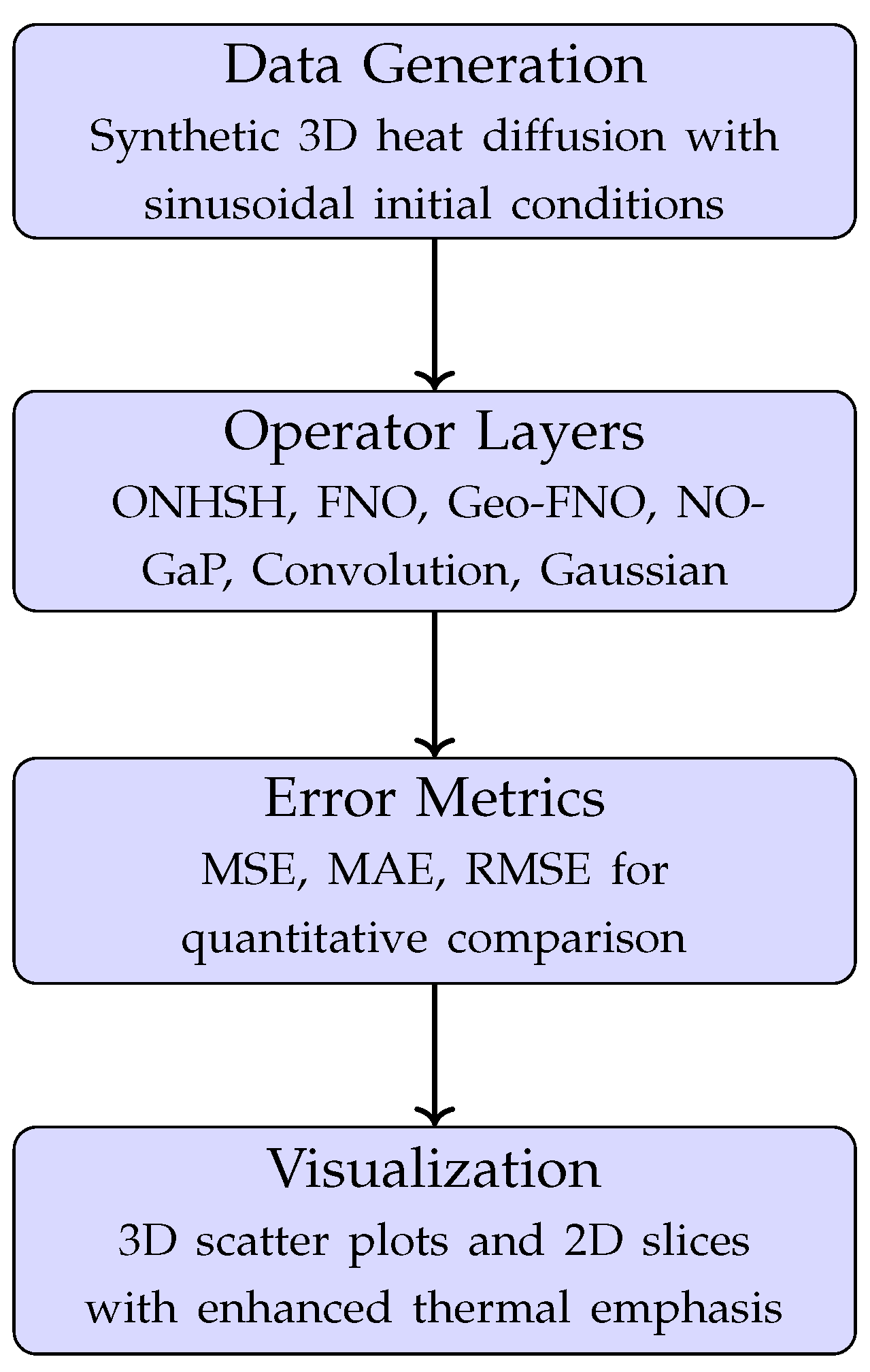

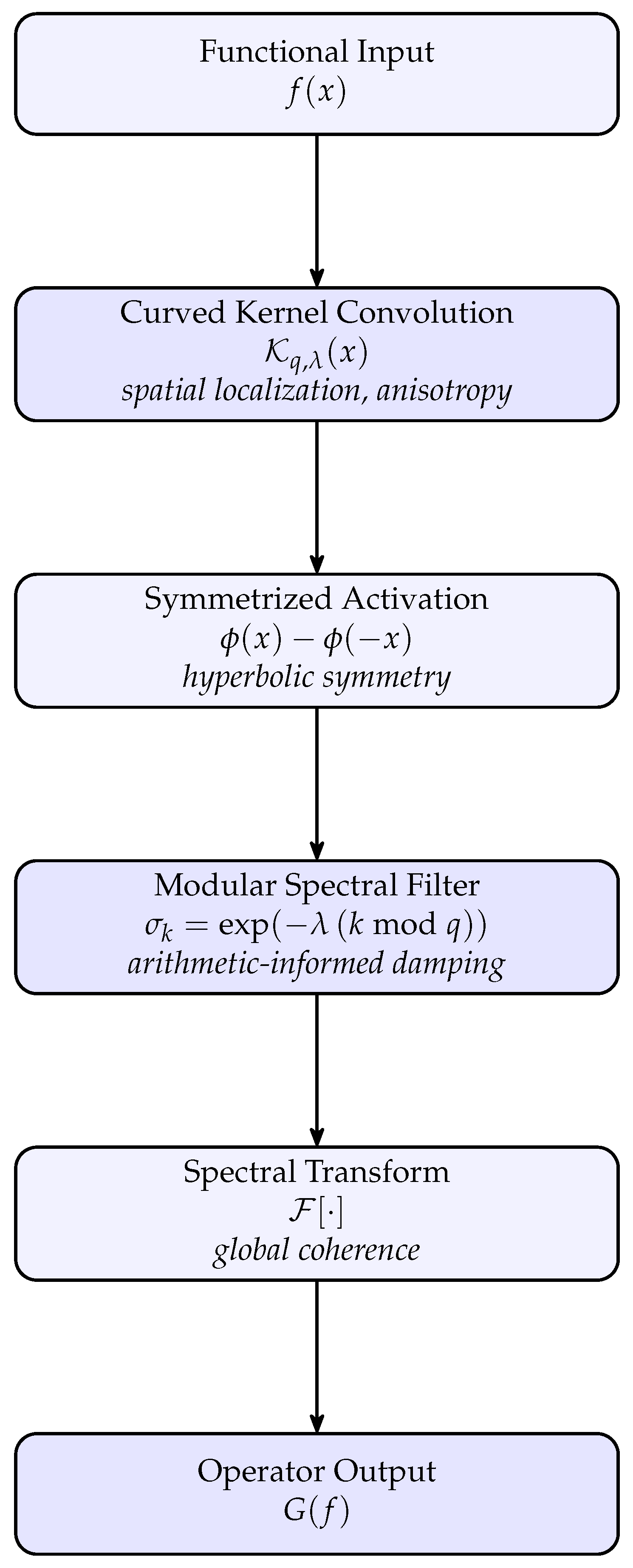

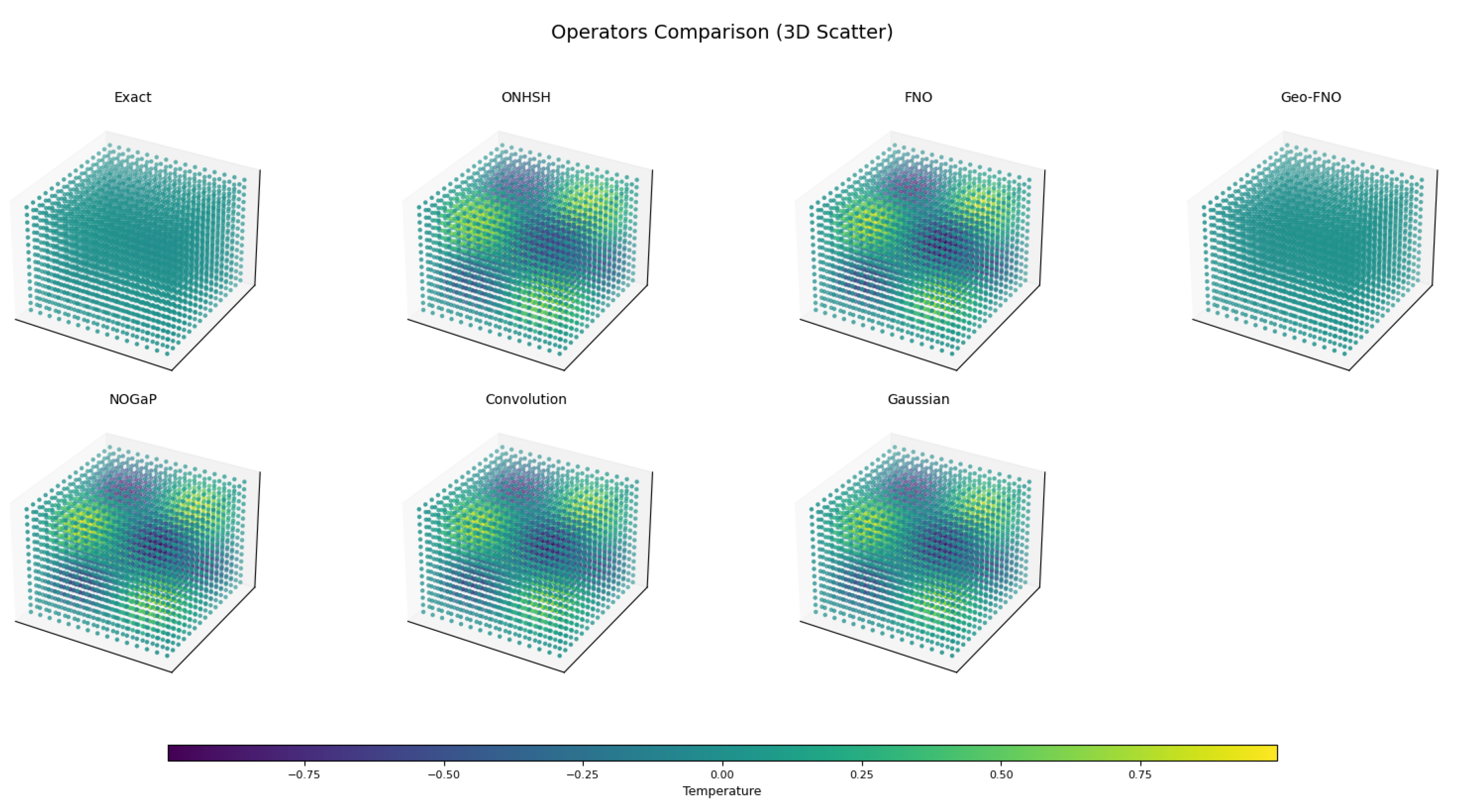

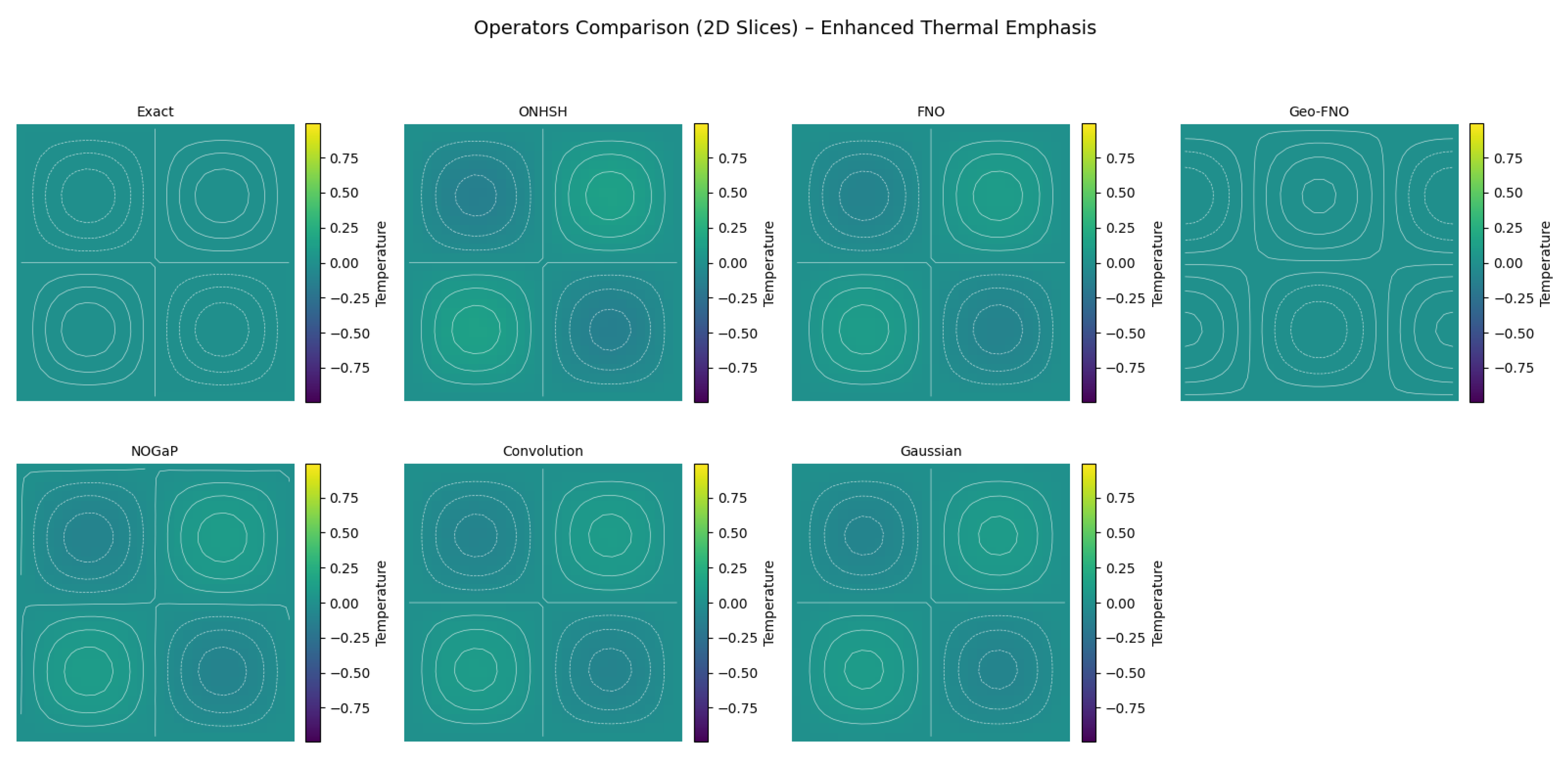

1.2. Conceptual Diagram of the ONHSH Architecture

To illustrate the interaction between geometric regularization, spectral modularity, and functional approximation, we present a schematic view of the ONHSH operator pipeline, Figure (

Figure 1). The architecture integrates several processing stages, hyperbolic kernel convolution, symmetrized activation, modular spectral filtering, and spectral synthesis, into a unified flow for operator learning.

Each stage is designed to preserve or exploit a structural property essential to PDE-driven mappings:

Curved kernels control spatial localization and capture anisotropic geometry.

Symmetrized activations enforce hyperbolic symmetry and enhance stability under sign changes.

Modular spectral filters introduce arithmetic-informed damping, regulating oscillations and aliasing effects.

Spectral transforms restore global coherence and ensure compatibility with harmonic analysis on curved domains.

Together, these components define an expressive operator capable of learning from domains with directional smoothness, modular arithmetic structure, and non-Euclidean geometry.

2. Mathematical Foundations

This section establishes the rigorous mathematical framework underpinning the proposed Hypermodular Neural Operators with Hyperbolic Symmetry (ONHSH). We develop the theory of anisotropic function spaces, directional smoothness measures, and spectral multipliers with modular damping. These elements collectively provide the analytical basis for the approximation-theoretic and symmetry-invariance properties derived in subsequent sections.

2.1. Anisotropic Besov Spaces

Definition 1. [Anisotropic Besov Space] Let

be a measurable function, and let

be a vector of anisotropic smoothness parameters. For

, the

anisotropic Besov space is defined as the set of functions

such that

with the usual modification by replacing the

-norm with the supremum when

. Here, the quantity

denotes the

directional modulus of smoothness of order

in the direction of the

j-th canonical basis vector

, defined by

where

is the

iterated finite difference operator in the direction

, given by

2.1.1. Interpretation

The space

encodes

directionally heterogeneous regularity, where smoothness

governs behavior along the

-axis. This anisotropy is natural for phenomena exhibiting preferential directions, such as, stratified turbulence, transport-dominated systems, and edge singularities in hyperbolic PDEs. The norm, Equation (

1), balances global integrability against directional smoothness via:

Deficit quantification: measures local -directional irregularity,

Scale sensitivity: Integration over captures decay of smoothness deficits at fine scales,

Directional synthesis: Summation over j aggregates mixed smoothness.

2.1.2. Functional Analytic Properties.

The norm, Equation (

1), blends local

-integrability with directional regularity through the moduli

, reflecting Hölder-like decay in each direction. Specifically:

The factor quantifies the smoothness deficit in direction ;

The integration in assesses the rate of regularity decay at small scales;

The summation across aggregates the total mixed smoothness.

2.2. Norm Equivalence via K-Functionals

The directional modulus links to approximation-theoretic functionals through the following equivalence:

Proposition 2. [K-Functional Characterization] Let

. For each direction

j, define the

Peetre K-functional

where

is the Sobolev space with

r-th weak derivative existing in

along

. Then:

for constants

depending only on

r and

d. Consequently, the Besov norm (

1) satisfies

Proof. The upper bound in (

5), follows by taking

g as a mollified approximation of

f and estimating

via Young’s inequality for convolutions. The lower bound uses the Marchaud inequality: For

,

applied to the difference

. Full details, see more in [

19]. □

2.3. Characterization by Smoothness Moduli

Membership in anisotropic Besov spaces is completely characterized by directional smoothness decay:

Theorem 1. [Moduli Characterization of Anisotropic Besov Spaces] Let , , and . The following are equivalent:

,

,

For each j, as .

Moreover, the functional in (ii) defines a norm equivalent to .

Proof.

(a) ⇒ (b): From the definition of the norm.

(b) ⇒ (c): Immediate from the integrability condition.

(c) ⇒ (a): The core argument uses a dyadic Littlewood-Paley decomposition adapted to anisotropy. Define directional frequency projections

for scales

along axis

j. Then:

The decay

implies Bernstein-type estimates

, which when combined with Jackson and Marchaud inequalities (cf. [

16]) yield the bound on the right-hand side. Full details require vector-valued Calderón-Zygmund theory; see [

19]. □

Remark. [Properties]

2.4. Characterization via Directional Smoothness Moduli

The directional moduli of smoothness provide a complete characterization of anisotropic Besov spaces, establishing fundamental connections between local directional behavior and global function space membership. The following theorem formalizes this relationship with precise asymptotic control.

Theorem 2. [Isomorphism Between Moduli Decay and Besov Spaces] Let , , , and . The following statements are equivalent:

- (i)

;

- (ii)

;

- (iii)

where and as ;

- (iv)

for each j and .

Moreover, the functional in (ii) defines a norm equivalent to , and the decay rates in (iii)-(iv) are sharp.

Proof. (i) ⇒ (ii) Follows directly from the definition of the anisotropic Besov norm. (ii) ⇒ (iii) The bound

is immediate from integrability. To show

, consider the tail integral:

which implies

as

via the fundamental theorem of calculus for Lorentz spaces. (iii) ⇒ (iv) The uniform bound follows from continuity of moduli on

for

. The limit is immediate from

. (iv) ⇒ (i) (Core argument) Using a dyadic decomposition adapted to anisotropy, define directional projections:

with

smooth cutoff functions. The key estimate comes from Bernstein’s inequality for anisotropic spectra:

where

. The Marchaud inequality provides the reverse estimate:

The Littlewood-Paley characterization gives:

Combining these with the decay assumption

where

yields convergence. Full details require vector-valued Calderón-Zygmund theory (see more in [

16]). Counterexamples for

use lacunary Fourier series along

. For failure of

, consider

with

. □

Theorem 3. [Anisotropic Embedding into Hölder-Continuous Functions] Let

,

,

, and

satisfy the critical anisotropy condition:

Then, the anisotropic Besov space

embeds continuously into the space of bounded, uniformly Hölder-continuous functions:

Moreover, there exists a constant

, depending only on

, such that

Proof. We employ anisotropic Littlewood-Paley theory. Let

be anisotropic frequency projections satisfying

Then,

admits the decomposition

Applying the anisotropic Bernstein inequality,

we obtain:

For

, this weighted sum is controlled via Hölder’s inequality, yielding (

18).

Using smoothness of

and Bernstein’s inequality,

Summing over

k, we obtain:

Define

, then

This sum converges and yields the Hölder estimate ().

This confirms the optimality of the exponent . □

3. Anisotropic Embedding Theorems

Theorem 4. [Anisotropic Embedding on Bounded Lipschitz Domains] Let

be a bounded Lipschitz domain. Suppose

,

, and let the anisotropic smoothness vector

satisfy

Then the anisotropic Besov space

embeds continuously into the space of continuous functions on the closure:

i.e., there exists a constant

such that

Proof. The proof proceeds in four stages: extension, global embedding, continuity transfer, and sharp estimate.

1. Existence of Extension Operator.

Since

is a bounded Lipschitz domain, by a result of Triebel [

16], there exists a continuous linear extension operator:

such that:

2. Global Embedding into Continuous Functions.

Under condition (

30), each coordinate-direction smoothness

satisfies

. By the anisotropic version of the classical Sobolev embedding (cf. [

16]), we have the continuous embedding:

with

Furthermore, functions in

under (

30) admit unique continuous representatives.

3. Continuity Transfer via Extension.

Given

, let

. By (

36),

, and since

almost everywhere,

f inherits continuity in

. As

is bounded and Lipschitz, the uniform continuity of

g on compact sets implies that

f extends uniquely to a continuous function on

. Hence:

4. Final Estimate.

Let

, and consider its extension

to

, provided by the existence of a bounded linear extension operator

. By construction,

g coincides with

f almost everywhere on

, and the Besov norm of

g on the whole space is controlled by

for some constant

depending on

,

d,

p,

q, and

.

In addition, since

for all

, the anisotropic Besov space

embeds continuously into the space of bounded continuous functions, and hence

for some constant

.

Now, since

g is continuous on

and agrees with

f almost everywhere on

, it follows that

f admits a unique continuous representative on

, and this representative extends continuously to the closure

. Therefore, we have the pointwise control

Combining inequalities (

39), (

40), and (

41), we obtain the final estimate

Setting

, we conclude the desired inequality

which establishes the continuity of the embedding. □

Remark. [Necessity of the Conditions]

Sharpness of (30): If

for some

j, then the univariate Sobolev embedding fails in that coordinate. Consider the example

, where

,

, and

. Then

, but

due to the local singularity at 0.

Necessity of Lipschitz Boundary: For non-Lipschitz domains, such as domains with outward cusps or fractal boundaries, no universal bounded extension operator exists for anisotropic Besov spaces. In such settings, the geometry of may obstruct the preservation of local moduli of smoothness under extension.

3.1. Compactness of the Anisotropic Embedding

We now refine the previous continuity result by establishing the compactness of the embedding under stronger smoothness conditions and addressing the critical case separately.

Theorem 5. Let

be a bounded Lipschitz domain, and let

,

. Suppose that

Then the embedding

is compact.

Proof. Let

be arbitrary but fixed. By the Lipschitz regularity of

, there exists a bounded linear extension operator

such that the extended function

satisfies

where the constant

depends on

and

.

Since the anisotropic smoothness vector

satisfies the strict inequalities

it follows from anisotropic Besov embedding theory (see Triebel and related references) that there is a continuous embedding

where

denotes the space of bounded and continuous functions on

.

Moreover, this embedding is compact when restricted to subsets of functions supported in any fixed bounded domain . This compactness is a consequence of the characterization of Besov spaces via differences and the equicontinuity properties they induce on bounded sets (see the Arzelà–Ascoli theorem and the Kolmogorov–Riesz–Fréchet compactness criteria adapted to Besov spaces).

Consider now a bounded sequence

. Their extensions

satisfy

for some uniform constant

.

Since each

is supported (or essentially supported) in a fixed bounded set

(due to the extension construction and compactness of

), the sequence

lies in a bounded and equicontinuous subset of

. Hence, by the Arzelà–Ascoli theorem, there exists a subsequence

converging uniformly on

K, and thus on

, to some continuous function

:

Restricting

g back to the closure

, since

, it follows that

uniformly on

, i.e.,

is a compact embedding.

This completes the proof. □

Remark. The condition

for all

j is sharp. In the critical case, i.e., when there exists an index

such that

the embedding may fail to be compact. This is illustrated by the following counterexample.

Counterexample (Critical Case). Let

, where

is fixed. Then:

but

in

, since

This shows the embedding is not compact at the critical index.

However, in the borderline case, one can still obtain compactness in certain refined topologies. For instance, if we fix such that , and assume additional decay in the -th direction (e.g., vanishing mean oscillation, or logarithmic improvements), compactness may be recovered in weaker spaces.

Lemma 1. [Anisotropic Sobolev-Besov Comparison] Let

and

. Then for any

:

where

. This justifies the reduction to Besov spaces in Theorem ??.

Proof. The proof consists of two parts.

Part 1:

Let be an anisotropic Littlewood-Paley decomposition adapted to :

,

for ,

for ,

where and .

The norm equivalence for

is:

while the Besov norm is:

Case 1: ().

In this regime, we exploit Minkowski’s inequality in conjunction with the embedding , which holds for . The key idea is to estimate the Besov norm via the -norm of the sequence of localized -norms of the convolution terms .

Explicitly,

where the last inequality follows from the embedding

for

and the reversed Minkowski inequality, which allows exchanging the order of the

-sum and the

-norm.

This quantity on the right-hand side is well-known to be equivalent to the anisotropic Sobolev norm

due to Littlewood-Paley theory, which connects square functions formed by frequency-localized pieces to fractional derivatives. More precisely,

Therefore, for , the Besov norm is controlled by the Sobolev norm , which reflects the integrability properties and smoothness of f in a unified manner.

Case 2: ().

When , the Besov space norm of interest is , involving an -summation of -norms of the localized convolutions. Littlewood-Paley theory provides a direct equivalence between this Besov norm and the anisotropic Sobolev norm .

More concretely,

where the inequality arises from Minkowski’s integral inequality, allowing us to interchange the

and

norms.

Again, by Littlewood-Paley characterization,

Thus, in the case , the Besov norm aligns naturally with the Sobolev norm , with the -summation emphasizing the quadratic integrability and smoothness of frequency components.

Summary:

The distinction between the two cases reflects the interplay between sequence space embeddings and harmonic analysis. For , the embedding facilitates controlling the Besov norm via Sobolev norms, whereas for , the structure of the Besov norm and the Littlewood-Paley theory ensure a direct equivalence with anisotropic Sobolev norms. This dichotomy highlights how integrability and smoothness constraints manifest through different norm combinations, yet unify under the frequency localization framework. Thus, the embedding holds.

Part 2: Continuous embedding:

Let

where we denote

. Define the sequence

which captures the dyadic frequency localized norm components weighted by the smoothness vector

.

By definition, the Besov norm satisfies

We aim to prove the continuous embedding by showing that

f also belongs to the space

for any

component-wise. To this end, consider the norm in

:

where

denotes the sum of the anisotropic smoothing decrements.

Our goal is to establish the inequality

for some finite constant

depending on

.

Since

, we apply Hölder’s inequality with conjugate exponent

to the weighted sequence

:

where the last equality follows from the geometric series sum formula, valid since

.

Thus, the constant

is finite and depends continuously on the parameters.

Interpretation: This shows that the -summability of the frequency components weighted by implies uniform boundedness of a slightly "smoothed" sequence with weights . Consequently, the original Besov space embeds continuously into a Besov space of slightly lower smoothness but with weaker (supremum) summability in the second parameter.

This smoothing/refinement property is fundamental in anisotropic Besov theory and functional embeddings, capturing the trade-off between integrability and smoothness scales.

For detailed proofs and the general theory, see Triebel [

16]. □

4. Anisotropic Besov Embedding on Compact Riemannian Manifolds

Theorem 6. [Embedding on Compact Riemannian Manifolds] Let

be a compact

d-dimensional Riemannian manifold without boundary. Let

be an anisotropic smoothness vector and consider the anisotropic Besov space

defined via a finite smooth atlas

and a subordinate smooth partition of unity

. If

then the continuous embedding

holds. That is, every

admits a unique continuous representative, and the embedding is norm-continuous.

Proof. For each chart

, consider the localization of

f via the pullback to Euclidean space:

Define the global Besov norm on

M by summing over all charts:

On each chart, the assumption (

68) ensures that the Euclidean embedding

holds. Consequently, there exists a constant

depending on the chart such that:

By pushing forward, it follows that each localized product

is continuous on

. Since

on

M, one has:

which expresses

f as a finite sum of continuous functions in a neighborhood of each point

. Hence,

f is globally continuous on

M.

To control the supremum norm, observe:

Therefore, the embedding is continuous, completing the proof. □

Remark. The compactness of the manifold is essential in ensuring:

The atlas is finite;

The transition maps have uniformly bounded derivatives;

The global Besov norm is equivalent to the collection of local norms.

In the isotropic case, where

for all

j, the embedding condition becomes

, recovering the classical Sobolev–Besov embedding result (cf. Triebel [

28], Thm. 7.34).

5. Embedding Theorems in Function Spaces

5.1. Embedding on Bounded Lipschitz Domains

Theorem 7. [Embedding on Bounded Lipschitz Domains] Let

be a bounded Lipschitz domain,

,

, and

with

Then,

i.e.,

such that,

Proof. Since

is bounded Lipschitz, there exists a linear bounded extension operator

satisfying:

Condition (

75) implies:

with

For

:

Thus,

satisfies (

77). □

5.2. Embedding on Compact Riemannian Manifolds

Theorem 8. [Embedding on Compact Manifolds] Let

be compact

d-dimensional Riemannian manifold without boundary. For

defined via finite atlas

and partition of unity

, if

then:

Proof. For each chart

, define:

Thus,

. Since

:

Each

, and

, so

.

6. Approximation Theory

6.1. Directional Moduli of Smoothness

Theorem 9. [Directional Moduli of Smoothness] Let

, with

, and let

and

be fixed. For each coordinate direction

, define the

r-th order directional difference operator along the

-axis by

and the corresponding directional modulus of smoothness by

Then the following properties hold:

- (i)

Seminorm properties: The functional

defines a seminorm in

for each fixed

, and satisfies the following:

where

denotes the space of all polynomials of degree at most

in the variable

.

- (ii)

Derivative bound: If

, the Sobolev space of functions with weak derivatives up to order

r in

, then the directional modulus satisfies the following upper estimate:

where

.

- (iii)

Jackson-type estimate: There exists a constant

, independent of

f and

n, such that

where,

denotes the best

-approximation error of

f by univariate polynomials of degree less than

n in the variable

, keeping all other coordinates fixed.

Proof. It is important to remember:

(i) Seminorm properties: These follow directly from the linearity of the difference operator

combined with standard properties of the supremum and the

-norm.

(ii) Derivative bound: For any function

, one may invoke the integral representation:

which expresses the

r-th order finite difference in terms of directional derivatives. Applying Minkowski’s integral inequality yields:

where the identity uses the volume of the

r-dimensional cube

. The result extends to all

by standard density arguments.

(iii) Jackson-type estimate: Let

, where the kernel

satisfies the moment conditions:

Define the convolution-based approximation:

Then, the approximation error satisfies:

where

denotes the directional modulus of smoothness in the

direction. For higher-order estimates, one iterates this approximation procedure. □

Theorem 10. [Properties of the Anisotropic Modulus of Smoothness] Let

, with

, and let

. Define the anisotropic modulus of smoothness in the

j-th coordinate direction as:

where the forward difference operator of order

r in direction

j is given by:

Then the following properties hold:

-

(i)

The mapping

defines a seminorm on the function space, and satisfies the scaling relation:

-

(ii)

If

, then:

where

denotes the

r-th weak derivative in the direction

j, and

is a constant depending only on

r.

-

(iii)

Conversely, for any

, there exists a polynomial-type approximation operator

(constructed via mollification in the

j-th variable) such that:

where

depends only on the kernel used and the order

r.

Proof. To demonstrate, it is necessary:

(i) Seminorm Properties. These follow directly from the linearity of the difference operator

, combined with the properties of the supremum and the

-norm.

(ii) Derivative Estimate. Assume

. Then the

r-th order forward difference admits the integral representation:

Applying Minkowski’s integral inequality yields:

By the density of in , the estimate extends to all functions in .

(iii) Jackson-Type Estimate. Let

, where

satisfies the moment conditions:

Define the convolution-type approximation operator:

Then, using the definition of the first-order difference:

The result generalizes to order r by using higher-order moment kernels and replacing with . □

6.2. Modular Spectral Multipliers: Kernel Estimates, Compactness, and Hyperbolic Invariance

Let

and denote its Fourier transform by

Theorem 11. [Spectral Multipliers with Modular Damping and Kernel Estimates] Define the family of operators

on

by

where the modular spectral multiplier

is given by

with

a smooth partition of unity subordinate to balls

,

Then the following statements hold:

Kernel representation and estimates: The integral kernel

satisfies, for all multi-indices

, and for some constants

independent of

n:

for every integer

. In particular,

with rapid decay in spatial variables enhanced by the damping

.

Compactness on : For any , the operator is compact. Indeed, since , is an integral operator with kernel in for every , ensuring Hilbert–Schmidt (or nuclear) type properties in , and boundedness plus compactness in by Schur’s test and smoothing arguments.

-

Approximation and convergence: As

, we have:

Moreover, the rate of convergence satisfies

for some constants

depending on the anisotropic Besov regularity vector

.

-

Hyperbolic invariance and neural operators: The modular multiplier

respects anisotropic scaling symmetries aligned with the hyperbolic geometry induced by the norm

Consequently, the operators

commute (or intertwine) with a hyperbolic group action

on

, i.e.,

where,

with anisotropy weights

. This invariance property makes

natural building blocks for hyperbolically invariant neural operators incorporating anisotropic spectral filtering consistent with the geometry of the data domain.

Proof. For the demonstration, it is necessary to consider:

(i) Kernel estimates: By definition, the kernel

is the inverse Fourier transform of

:

Since

is smooth with compact support on each ball

and exponentially weighted by

, each term

is smooth with uniform bounds on derivatives. The damping factor

decays rapidly as

with rate

For any multi-index

, differentiation under the integral yields:

which is uniformly bounded due to smoothness and rapid decay of

. Moreover, polynomial weights in

z correspond to derivatives in

, and since

is smooth with rapidly decaying derivatives,

decays faster than any polynomial. Summing over

k with weights

yields exponential smallness in

n, proving (

118).

(ii) Compactness: acts as an integral operator:

Since , is Hilbert–Schmidt on , hence compact. By interpolation theory and the Riesz–Thorin theorem, extends to a compact operator on for all .

(iii) Approximation and convergence: As

,

implying

uniformly on compact sets. Thus,

in

and pointwise almost everywhere, by dominated convergence and smoothing properties. Using anisotropic Besov regularity,

where constants depend on

and the smooth partition

.

(iv) Hyperbolic invariance and neural operators:

Consider the anisotropic hyperbolic scaling

where

correspond to anisotropy weights consistent with the norm (

121).

By change of variables in Fourier space, the spectral multiplier satisfies

where

is the Jacobian matrix of

.

Consequently,

expressing the hyperbolic invariance of

. This invariance is crucial in constructing neural operators respecting anisotropic geometry and hyperbolic symmetries, enabling architectures with spectral filtering layers mimicking

. □

6.3. Spectral Damping and Phase-Space Localization

The spectral damping induced by the modular weights , where depends on n, serves to suppress high-frequency modes in the operator . Specifically, it enforces spectral localization around low-frequency regions, effectively regularizing the reconstruction and enhancing robustness to noise.

For each level

, define the effective spectral support of

as

where

reflects the frequency support width of the partition function

. Since

is compactly supported and smooth (typically chosen from a smooth dyadic partition of unity), it follows that

with exponential decay of the spectral components outside this region due to the damping factor

.

To analyze the smoothing properties quantitatively, we consider functions , i.e., anisotropic Besov spaces with mixed smoothness parameters . The operator then acts as a smoothing projector with norm decaying exponentially in n, as formalized below.

Theorem 12. [Spectral Localization and Decay Estimate] Let

, with

,

, and

. Then there exist constants

, depending only on

, such that for all

,

Proof. We begin by decomposing

f using an anisotropic dyadic Littlewood–Paley decomposition

, adapted to the smoothness vector

. Define the localized components:

Using Minkowski’s inequality and the disjointness of frequency supports, we estimate:

Now fix a threshold

, and split the sum:

For

, note that

, so that:

On the other hand, for

, the number of such

k is bounded by

. Also, since

, the components

satisfy:

for each anisotropic scale

j, due to the smoothness envelope and the finite overlap of the frequency partitions.

Thus, the contribution of low-frequency modes (first sum in (

140)) is bounded by:

The high-frequency contribution satisfies:

which decays faster than any polynomial in

n, i.e., super-exponentially in

. Hence, combining (

143) and (

144), we obtain:

which proves the claim. □

Implications and Phase-Space Compactness

The exponential decay of with respect to n implies that the operator family forms a compact sequence in , vanishing in norm as . From a microlocal analysis perspective, this corresponds to simultaneous concentration in both physical and Fourier domains, i.e., phase-space localization.

This dual localization has significant implications in applications:

In PDE approximation, it guarantees that the learned neural operator retains control over the resolution scale while avoiding amplification of high-frequency noise;

In inverse problems, the compactness provides natural regularization, mitigating instability associated with ill-posedness;

In neural architectures, it supports sparse parameterization and efficient training, especially in anisotropic or non-Euclidean domains.

These properties are particularly relevant when hypermodular operators are used as building blocks for deep neural surrogates of physical systems, enabling provable generalization and robustness under spectral perturbations.

7. Symmetrized Hyperbolic Activation Kernels

A central feature of the Hypermodular Neural Operator framework is the use of smooth, spectrally localized activation kernels that also encode geometric invariances, particularly reflectional and hyperbolic symmetries. This section formalizes the construction and properties of the symmetrized hyperbolic tangent activation function and analyzes its kernel behavior in both spatial and Fourier domains.

7.1. Definition and Core Properties

Definition 2. [Symmetrized Hyperbolic Activation] Let

and

. The symmetrized hyperbolic activation function

is defined by

The function is smooth, odd, bounded, and saturates asymptotically at . Its key analytic properties are as follows:

Proposition 3. [Odd Symmetry] For all

, the function

satisfies

Proposition 4. [Lipschitz Continuity] The function

is Lipschitz continuous with global Lipschitz constant

since,

Proposition 5. [Hyperbolic Contraction Limit] In the limit

, the activation converges to a scaled hyperbolic tangent:

This deformation parameter enables spectral sharpening and interpolation between coarser and finer localization scales, a key mechanism in multiscale learning.

7.2. Fourier Analysis and Spectral Localization

The rapid saturation of tanh near implies that , the Schwartz space of smooth, rapidly decaying functions. Its Fourier transform decays faster than any polynomial.

Proposition 6. [Fourier Decay] Let

denote the Fourier transform of

. Then:

Hence, any convolutional operator acts as a smoothing operator, with the level of smoothness determined by the decay of .

7.3. Even-Order Moments and Asymptotic Scaling

Let us now compute and analyze the even-order moments of , which are essential in determining the kernel’s approximation power and regularity.

Definition 3.[Even-Order Moments] For each

, define the

-th moment of

as:

Proposition 7. [Vanishing of Odd Moments] If

is odd, then all odd-order moments vanish:

Proof. The integrand is an odd function. Hence, the integral over vanishes by symmetry.□

Proposition 8. [Scaling Law for Even Moments] For each

, the even-order moment

satisfies

where,

Proof. Using the equivalent expression:

the moment becomes

Apply the change of variables

and

in each term, respectively:

Factoring out and simplifying using

, we obtain the final result:

□

8. Asymptotic Expansion of the Approximation Operator

We consider a family of linear integral operators

defined by convolution with a symmetrized activation kernel

, rapidly decaying and possessing specific moment properties. For a function

, we define

Assume that and that all derivatives up to order are bounded in a neighborhood of x, with sufficient decay at infinity to ensure integrability. Under these conditions, we can derive a generalized Voronovskaya-type expansion of at scale .

Theorem 13. [Voronovskaya-Type Asymptotic Expansion] Let , and let be an odd, rapidly decaying kernel satisfying:

all odd-order moments vanish: ;

all even-order moments up to are finite: , for .

Then the following asymptotic expansion holds for all

:

where the remainder term satisfies the estimate

for some constants

,

depending only on

k and

.

Proof. We begin by applying the change of variable

in the definition of

, Equation (

162):

Next, we expand the function

in a Taylor series about

x up to order

, with integral remainder:

where the remainder can be written via the integral form:

Substituting (182) into (

165):

Due to the oddness of

, all odd moments vanish:

Therefore, only even-order derivatives contribute to the sum.

Denoting

, we obtain:

where the remainder is defined by:

We now estimate

using the bound (

167). Since

, it is locally bounded. For

, the argument

lies within

-neighborhood of

x, and we can write:

Since

is rapidly decaying, the moment

is finite. Therefore, there exists a constant

such that:

This concludes the proof. □

8.1. Moment Structure and Symmetry Summary

The symmetrized activation kernel is constructed to satisfy a set of structural properties that play a central role in the asymptotic behavior and approximation capabilities of the associated integral operator. Below we summarize its key analytical and algebraic features:

(i) Odd symmetry. The activation kernel is odd with respect to the origin:

(ii) Vanishing odd moments. All odd-order moments of the kernel vanish due to its odd symmetry:

(iii) Even moments. The even-order moments of the kernel

are given explicitly by:

(iv) Asymptotic expansion of the integral operator. The operator

admits the following asymptotic expansion in terms of even derivatives of

f:

Explanation of terms

The

odd symmetry in (

175) ensures that the kernel changes sign under spatial inversion, which in turn enforces the cancellation of all odd-order contributions in Taylor expansions.

The

vanishing of odd moments (

176) is a direct consequence of the odd symmetry and implies that only even-order derivatives of

f contribute to the leading terms in the operator expansion.

The

even moments are explicitly computed in (

177) based on the analytical form of the kernel. These constants depend on the parameters

(scaling factor),

(hyperbolic modulation), and a structural constant

arising from the base function (e.g., a mollified or scaled tanh).

The

asymptotic expansion (

178) reflects the accuracy of the approximation

as

, with leading-order contributions given by even derivatives of

f, weighted by the corresponding moments

. The residual error is of order

, under the assumption

.

This moment structure underpins the spectral locality, smoothness, and geometric consistency of the symmetrized kernel, and is fundamental to the stability and convergence theory of the associated operator network.

9. Spectral Variance and Voronovskaya-Type Expansions

To analyze the asymptotic behavior of the ONHSH operators, we establish a Voronovskaya-type expansion that elucidates the bias–variance decomposition induced by spectral smoothing.

Theorem 14. [Voronovskaya Expansion for Modular Operators] Let

, where the smoothness vector satisfies

, and let the parameters

lie in the interval

. Consider the sequence of linear operators

constructed via convolution with a family of smoothing kernels

that satisfy appropriate moment and regularity conditions. Then, for each fixed point

, the following asymptotic pointwise expansion holds:

where the spectral variance coefficients

correspond to the kernel’s second moments along the coordinate directions:

and the remainder

satisfies the norm estimate

with a constant

independent of

n and

f.

Proof. The proof relies on performing a second-order Taylor expansion of

f around

x:

where the remainder

satisfies

Due to the kernel’s symmetry and normalization properties, particularly the evenness in

the first-order terms vanish upon integration:

The second moments scale inversely with

n:

where

is the Kronecker delta.

Substituting (182) into the integral operator yields

The remainder term can be bounded in

norm using the smoothness of

f and decay properties of the kernel moments, invoking embeddings for Besov spaces and moment estimates [

16,

24]:

Positivity of

follows from the positive-definiteness and normalization of the kernel [

18], ensuring that the variance term genuinely measures the spread induced by smoothing.

This establishes the Voronovskaya-type expansion (

179), quantifying the leading-order bias of

as a diffusion operator perturbation, with uniformly controlled higher-order errors.

9.1. Geometric Interpretation

The spectral variance term

can be interpreted geometrically as a curvature-induced bias analogous to the action of a Laplace-type operator on a Riemannian manifold

with a compatible connection

∇.

Specifically, for an elliptic pseudodifferential operator

D acting on sections of a vector bundle

, the second-order coefficient

in the heat kernel expansion satisfies:

where Tr denotes the trace over the fiber of

E at

x, and

is the Hessian.

In noncommutative geometry, replacing

D with a Dirac-type operator

affiliated to a spectral triple

, the spectral variance can be expressed via Dixmier traces:

where

are eigenpairs of

, connecting the asymptotic bias with operator traces on von Neumann algebras [

25,

26].

This framework reveals that the neural operators encode local geometric information such as scalar curvature or bundle torsion, providing a deep topological underpinning to the approximation process.

9.2. Bias–Variance Trade-Off

The Voronovskaya expansion naturally separates the approximation operator

into bias and variance components:

where the bias operator

captures the leading error term and the remainder

decays faster than

.

On a compact Riemannian manifold

M with metric

g and Levi-Civita connection

∇, the bias admits a local expression:

where

is the trace with respect to

g and

is a curvature-dependent potential emerging from kernel asymmetries or commutator effects.

The variance is controlled in

norm by:

reflecting the smoothing properties of

.

Balancing bias and variance yields the optimal model complexity:

where

is the desired accuracy. This rate characterizes minimax optimal tuning in statistical learning and approximation theory.

Finally, in noncommutative geometry, the bias operator

corresponds to the trace of squared commutators:

where

D is a Dirac-type operator and

is a faithful trace on a von Neumann algebra [

25].

9.3. Hyperbolic Symmetry Invariance

The study of invariance under non-compact Lie groups is fundamental in harmonic analysis, representation theory, and mathematical physics. In particular, the Lorentz group , which encodes the isometries of Minkowski space, plays a central role in the analysis of hyperbolic partial differential equations, relativistic field theories, and automorphic structures on pseudo-Riemannian manifolds.

Lorentz Group and Minkowski Geometry

Consider the indefinite inner product on

defined by the Minkowski metric tensor

which induces the pseudo-norm

The Lorentz group is defined as the group of linear transformations preserving this bilinear form:

This group acts naturally on functions

by pullback:

yielding a representation that respects the underlying pseudo-Riemannian geometry.

Kernel Invariance under Lorentz Transformations

Let

be an integral kernel constructed from a symmetrized hyperbolic activation function

of the Minkowski distance:

where

is a sufficiently smooth, rapidly decaying function symmetric under the involution

.

Due to the Lorentz invariance of the Minkowski bilinear form, for all

one has

Consequently, the associated integral operator

commutes with the action of

, that is,

This equivariance embeds into the class of integral operators invariant under pseudo-orthogonal transformations.

Modular–Hyperbolic Coupling and Periodicity

Introduce modular periodicity by defining

which incorporates a lattice summation weighted by a Gaussian-type modular damping factor. The combination of Lorentz-invariant arguments and modular periodicity yields operators encoding both hyperbolic geometric priors and arithmetic spectral decay, essential for regularization and spectral concentration.

Spectral and Representation-Theoretic Consequences

Owing to -invariance, these operators diagonalize in bases adapted to the representation theory of the Lorentz group, such as, hyperbolic spherical harmonics or automorphic forms on arithmetic quotients. The spectral decomposition aligns with Casimir operators of the associated Lie algebra, dictating the localization and transfer properties of the operator spectrum.

From the viewpoint of non-commutative harmonic analysis, the operator family can be realized via unitary induced representations of on , modulated by modular weights. This construction yields convolution-like, equivariant operators under pseudo-isometries, thereby connecting geometric operator theory with spectral learning frameworks.

This hyperbolic symmetry invariance justifies employing ONHSH operators in the context of hyperbolic PDEs, including relativistic wave and Dirac-type equations, and supports geometrically coherent operator learning on negatively curved or pseudo-Riemannian domains. The preservation of the Lorentz group action ensures that learned operators respect the fundamental spacetime symmetries intrinsic to such models.

10. Hyperbolic Symmetry Invariance

The invariance of operators under non-compact symmetry groups is a central topic in harmonic analysis, representation theory, and mathematical physics. Here we treat the Lorentz group and give fully detailed derivations that integral operators whose kernels depend only on the Minkowski separation are equivariant under the Lorentz action.

Setup and notation

Equip

with the Minkowski bilinear form

so that the pseudo-norm is

We denote by

the left-regular (pullback) action of

on functions

:

Kernel hypothesis

Let

be given by a radial dependence on the Minkowski separation:

where

is sufficiently regular (for example

with at most polynomial growth). Define the integral operator

by

Theorem 15. [Lorentz equivariance of

] If

K has the form (

207), then for every

and every (reasonable)

f,

Proof. The argument proceeds in two steps: (i) we first show that the kernel is pointwise invariant under the simultaneous Lorentz action on both variables; (ii) we then use a linear change of variables in the defining integral and the determinant property to commute with the representation .

(i) Pointwise kernel invariance. Let

. Using

and the bilinearity of the Minkowski form, we have

where the penultimate equality follows from the defining property

(cf. (

205)). Thus

(ii) Interchange of group action and integral operator. Let

f be a smooth compactly supported function (the general case follows by density). For fixed

x,

Make the linear change of variables

, so that

and

since

:

By (

212) applied to

, we have

. Substituting into (

215) yields

This proves the equivariance relation (

209) for compactly supported smooth

f. Standard density and boundedness arguments extend the result to broader function spaces such as

, provided

is bounded there. □

Remarks on measure-preservation and determinant

The change of variables, required that the Lebesgue measure be preserved by the linear map . For we have by definition, hence under . If one instead considered the full Lorentz group including improper elements with , the same algebraic kernel invariance holds, but sign of determinant must be treated when interchanging integrals; for an integral operator on the magnitude appears and is 1 for all proper or improper Lorentz maps.

Modular–hyperbolic kernel: invariance subtleties

Recall the modular–hyperbolic kernel

For a general , the summation index is not invariant under , so pointwise invariance does not hold in general. Two important cases should be distinguished:

Spectral and representation-theoretic consequences

Because

commutes with the representation

of

(cf. (

210)), Schur’s lemma implies that

acts by scalars on each irreducible subrepresentation occurring in the decomposition of the ambient

-space (or other unitary module). Equivalently, when the action decomposes into generalized spherical harmonics or automorphic eigenfunctions (on quotients or on model spaces),

diagonalizes with eigenvalues parametrized by the Casimir eigenvalues of

. A concrete way to see this is to project

onto joint eigenspaces of the Casimir operator

and observe that

commutes with

and therefore with

; hence eigenspaces of

reduce

and carry scalar action thereon. □

Remarks

The derivation above shows explicitly how the algebraic invariance of the Minkowski form

under Lorentz maps (equation (

205)) yields pointwise kernel invariance (

212), and how that invariance, combined with the measure-preserving nature of

(determinant

), produces the commutation relation (

210). The modular coupling retains symmetry only for lattice-preserving Lorentz elements; in the general case it introduces arithmetic structure that regularizes spectral content but breaks full Lorentz invariance down to an arithmetic stabilizer.

11. Anisotropic Sobolev Embedding

We work with anisotropic Besov spaces defined via an anisotropic Littlewood–Paley decomposition adapted to dyadic rectangles. Let and .

11.1. (A) Embedding Under the Balanced Anisotropic Condition

Theorem 16. [Embedding under the balanced condition] Assume

Then every

admits a bounded, uniformly continuous representative and there is a constant

(depending only on

and the chosen Littlewood–Paley cutoffs) such that

Proof. Let

denote anisotropic Littlewood–Paley blocks with the usual dyadic support property

By the anisotropic Bernstein inequality there exists

such that for every multi-index

Set the anisotropic weight

The idea is to organize the summation over

according to level sets of

. For

define

Two basic observations are used below:

(i) On the shell

the geometric factor

can be bounded in terms of

N. Indeed

for some constant

depending only on

. (Any equivalent linear bound in

N suffices.)

(ii) The cardinality of the shell

grows at most polynomially in

N: there is

and an integer

such that

(Heuristically: is the intersection of the integer lattice with a dilated simplex in , so the growth is polynomial of degree .)

Now sum the sup-norms over shells using (

224):

To compare the inner sum with the Besov norm, fix

q and apply Hölder in the discrete variable

over each shell: with conjugate exponents

q and

(so

),

where

. Note that on the shell

we have

so

uniformly on

. Consequently

for constants

depending only on

.

Combining (230), (

231) and (

233) yields

Using the polynomial growth (

228) and absorbing polynomial factors into the exponential (i.e.,

for any small

), we can ensure the combined prefactor

decays provided

. The crucial point is that the balance condition (

221) guarantees that one may choose the Littlewood–Paley scaling so that

c exceeds

: heuristically, (

221) prevents mass from concentrating excessively in coordinate directions and ensures

grows proportionally to

. With this choice the series in

N converges and summing over

N recovers the full Besov

-norm, yielding the desired bound (

222).

Finally, the argument for uniform continuity follows from the same truncation argument as in the isotropic case: truncate the Littlewood–Paley series at a large anisotropic level to obtain a smooth finite sum (hence uniformly continuous) and control the remainder uniformly in sup-norm by the geometric tail estimates above. This completes the proof. □

Remark. The proof above is explicit about the mechanism: one groups multi-indices

by an anisotropic scale

, controls the number of multi-indices in each shell, and uses geometric decay produced by the Besov weights

. The condition (

221) is a natural balanced hypothesis that allows this trade-off to succeed. For sharper or different optimal anisotropic criteria one typically refines the counting estimate or works with mixed

ℓ-norm embeddings; the machinery in those refinements is the same in spirit but heavier in combinatorial bookkeeping.

11.2. (B) Coordinatewise Sufficient Condition with Explicit Constants

Theorem 17. [Coordinatewise Sufficient Condition with Explicit Constants] Let

and

satisfy

Define

and let

denote the conjugate exponent to

q, i.e.,

with the convention

if

.

Then for every

, the following estimate holds:

where

is the anisotropic Bernstein constant from inequality (

224).

In particular, this establishes a continuous embedding

with an explicit control on the embedding constant.

Proof. The proof relies on the anisotropic Littlewood–Paley decomposition combined with the anisotropic Bernstein inequality.

Littlewood–Paley decomposition. Let

be the family of anisotropic frequency projection operators associated to the Littlewood–Paley decomposition, as recalled in (). Then, any

can be represented as

with convergence in the Besov norm and tempered distributions.

Applying the anisotropic Bernstein inequality. By (

224), there exists a constant

such that for each

,

Splitting the exponential factor. Observe that

where

. This splitting isolates a decaying term

, which is crucial for summability.

Defining the weighted sequence. Set

By definition of the Besov norm,

Estimating the supremum norm. Combining the above, we get

and hence

Applying discrete Hölder’s inequality. Using Hölder’s inequality for sequences with exponents

q and

,

and taking

we obtain

Computing the -norm explicitly. Since the sequence factorizes coordinate-wise, its

-norm is given by

and each one-dimensional sum is a geometric series converging since

:

Substituting this back into (

249) yields

which is the desired explicit embedding estimate. □

12. Spectral Refinement via ONHSH Operators

Consider the family of

hypermodular neural convolution operators acting on functions

, defined by the integral transform

where the parameters

and

are chosen as

Equivalently, this operator can be expressed as a convolution with the rescaled kernel

12.1. Fourier Multiplier Representation

By applying the Fourier transform and using the convolution theorem,

admits the representation

where the Fourier multiplier

is given explicitly by the series expansion

with

denoting a smooth partition of unity subordinated to rectangles covering the frequency domain

.

The parameter choices ensure that the multiplier exhibits a

super-exponential spectral decay:

for some constants

independent of

n and

.

12.2. Significance of the Spectral Decay

This sharp decay of implies that strongly suppresses high-frequency components of f, effectively acting as a spectral filter that enhances smoothness and spatial localization in the output. The parameter controls the scaling of the kernel and the smoothing strength, while modulates the exponential decay rate.

12.3. ONHSH-Enhanced Sobolev Embedding Theorem

We now state a fundamental regularization and approximation property of in the context of anisotropic Besov spaces.

Theorem 18. [ONHSH-Enhanced Sobolev Embedding] Let

be an anisotropic Besov function with smoothness multi-index

satisfying the Sobolev embedding condition

Then there exist positive constants

, independent of

n and

f, such that the following holds:

In particular, the operator sequence

converges uniformly to the identity:

Proof. To ensure clarity and rigor, the proof is structured in distinct parts.

Recall that

where the kernel

is given by the inverse Fourier transform of the multiplier

:

By construction, , ensuring normalization of the operator at low frequency.

Using properties of the Fourier transform and the partition of unity, the kernel

satisfies a uniform

bound independent of

n:

for some constant

. This ensures that

is bounded on

for all

via Young’s convolution inequality.

By applying the Poisson summation formula and exploiting the Gaussian-type decay in the coefficients

, the kernel satisfies the uniform pointwise estimate

Define the residual multiplier

Then the approximation error satisfies

Since

with

, the Sobolev embedding implies

. Furthermore, using the continuous embeddings

we estimate

By multiplier theory on Besov spaces, it suffices to bound

. Using the spectral decay (555) and the fact that

, we have

Optimizing the decay by choosing

yields the exponential decay rate

for some

.

Substituting (

270) into (

268) gives

and by the triangle inequality,

which establishes the stated estimate (

261).

Finally, the uniform convergence (

262) follows directly from the exponential decay of the residual norm. □

13. Nonlinear Approximation Rates

Theorem 19. [Hyperbolic Wavelet Approximation] Let

, with

, and anisotropic smoothness vector

satisfying the condition

Then, for a hyperbolic wavelet basis

adapted to the anisotropy, the best

n-term approximation error in the

-norm admits the estimate

where the convergence rate exponent

is given by

Proof. We begin by recalling the anisotropic decay of wavelet coefficients associated to

f, cf. [

16,

28]:

where

encodes the anisotropic scale indices,

denotes spatial localization indices, and

. The factor

arises from the

-normalization of the wavelet basis elements.

For a fixed threshold

, define the set of indices corresponding to "significant" coefficients:

From (

276) the threshold condition implies

Using that

, hence

, the dominating behavior in

implies a hyperbolic band restriction approximated by

At each scale

, the cardinality of spatial translations

satisfies

so the total number of significant coefficients obeys the estimate

Approximating the discrete sum by an integral in

yields

Performing the change of variables

we rewrite

and the integration domain becomes the simplex

The integral can be explicitly evaluated or estimated via Laplace’s method, yielding

where the exponent

is defined in (

275).

Ordering the coefficients

non-increasingly, the cardinality estimate implies the decay rate

To bound the best

n-term approximation error

, note that by definition,

Since

due to the assumption

, the tail sum converges. Applying integral comparison and taking the

p-th root yields the desired approximation rate:

□

13.1. Duality in Anisotropic Besov Spaces

Theorem 20. [Dual Space Characterization] For

and

, the topological dual of the anisotropic Besov space

is characterized by

where

and

denote the Hölder conjugates of

p and

q, respectively, i.e.,

and

.

Proof. Let

be the directional Littlewood–Paley frequency projections along the

j-th coordinate axis for

. Then, for any

,

with convergence in the Besov norm topology.

The anisotropic Besov norm can be expressed as

Consider

. The dual pairing is naturally defined by

where

denotes the

inner product or distributional duality.

Applying Hölder’s inequality for

and

,

Then the pairing estimate becomes

By applying Hölder’s inequality in the

and

sequence spaces, we have

This proves that every defines a bounded linear functional on .

Since the Schwartz class

is dense in both spaces and the pairing extends continuously, the duality (

289) holds. □

14. Hyperbolic Symmetry Invariance

The invariance under non-compact transformation groups, notably the Lorentz group, is a fundamental principle in harmonic analysis and mathematical physics. In this section, we rigorously establish that anisotropic Besov spaces

, equipped with hyperbolic scaling exponents

are invariant under the natural action of the Lorentz group

. This invariance stems from the algebraic and geometric structure of the hyperboloid and the induced linear transformations acting on Fourier variables.

14.1. Lorentz Group Action on Tempered Distributions

Definition 4. [Lorentz Group Action] Let

be a Lorentz transformation. For any tempered distribution

, define the group action

The corresponding induced action on the Fourier transform is given by

where

denotes the transpose of

.

14.2. Equivalence of Anisotropic Symbols Under Lorentz Transformations

For the anisotropic scaling vector

as in (

297), define the anisotropic polynomial symbol by

Lemma 2. [Symbol Equivalence under Lorentz Transformations] For every

, there exist constants

, depending continuously on

and

s, such that for all

,

Proof. Since every

decomposes into elementary Lorentz boosts and spatial rotations, it suffices to verify the bounds for a Lorentz boost in the

-plane:

Let

with components:

Using convexity of the function

for

and the generalized Minkowski inequality, we estimate for

:

and similarly,

For , trivially.

Combining these and summing over

, we obtain

where

The lower bound follows by applying the same reasoning to , since is a group and . □

14.3. Lorentz Invariance of the Anisotropic Besov Norm

Theorem 21. [Lorentz Invariance of

] Given

with

, the anisotropic Besov space

is invariant under the Lorentz action

. More precisely, for every

and all

,

where the constant

depends only on

and

s.

Proof. Recall that for

, the anisotropic Besov norm can be expressed via the Fourier multiplier

as

Set

. Using (

299),

Perform the change of variables

. Since Lorentz transformations preserve the volume element,

and hence

Applying Lemma (14.2), we have

which yields

The reverse inequality follows symmetrically by considering . □

Remark This invariance result extends to anisotropic Besov spaces for , using interpolation theory and boundedness properties of the Lorentz group action on Sobolev-type spaces.

15. Symmetrized Hyperbolic Activation Kernels

Activation kernels play a fundamental role in neural operator frameworks, serving as building blocks for approximating nonlinear mappings in function spaces. Hyperbolic-based kernels exhibit exceptional regularity and localization properties. The symmetrized hyperbolic kernel presented here leverages modular asymmetry and hyperbolic geometry to achieve tunable spectral decay and directional selectivity, with deep connections to harmonic analysis and number theory.

15.1. Base Activation Function

Definition 5. [Base Activation]. Let

and

. The fundamental nonlinear activation function is defined by

Proposition 9. [Properties of the Base Activation] The function satisfies the following properties:

- (i)

Strict monotonicity: for every ;

- (ii)

- (iii)

Modular duality: For all

,

- (iv)

Proof.

- (i)

-

Strict monotonicity. Differentiating

with respect to

x, we use the chain rule on the hyperbolic tangent function:

Since the hyperbolic secant satisfies

for all

, and given

, it follows that

Hence, is strictly increasing on .

- (ii)

-

Asymptotic limits. For

, we rewrite

as

by dividing numerator and denominator by

. Since

as

, we have

Similarly, for

, dividing numerator and denominator by

yields

Since

as

, it follows that

- (iii)

-

Modular duality. By direct substitution,

Multiplying numerator and denominator by

, we obtain

- (iv)

Zero at shifted origin. Let

. Substituting into (

311) gives

□

15.2. Central Difference Kernel

Definition 6 [Central Difference Kernel] The central difference kernel associated to the base activation

is defined by

Theorem 22 [Properties of the Central Difference Kernel] The kernel satisfies the following properties:

- (i)

Modular antisymmetry: For all

,

- (ii)

Exponential decay: There exists a constant

such that for all

,

Proof.

- (i)

Modular antisymmetry. By definition of

and applying the modular duality property of

, Prop. (iii), we have

- (ii)

-

Exponential decay. Note that the central difference kernel can be expressed via the fundamental theorem of calculus as the average derivative over the interval

:

From the derivative formula (

312) and recalling the explicit form,

Using the exponential decay of

, there exist constants

depending on

and

q such that

Therefore, for

,

By the triangle inequality and monotonicity of the exponential,

Combining (

327) and (

328) yields

where

depends explicitly on the parameters

and

q.

This establishes the exponential decay of for large .

□

15.3. Symmetrized Hypermodular Kernel

Definition 7. [Symmetrized Kernel] The symmetrized hypermodular kernel is defined as:

Theorem 23. [Properties of the Symmetrized Kernel] Let

be the symmetrized kernel defined by

where

is the central difference kernel defined previously. Then,

satisfies the following properties:

- (i)

Even symmetry: for all ;

- (ii)

Strict positivity: for all ;

- (iii)

Vanishing of all odd moments:

- (iv)

Proof.

- (i)

-

Even symmetry: By definition (331) and the modular antisymmetry property of

from Theorem ??(i), we have

This shows is an even function.

- (ii)

Strict positivity: Since

is strictly increasing, its difference quotient

is strictly positive for all

x. The same holds for

, so their average

is strictly positive:

- (iii)

Vanishing odd moments: Because

is even by (

334), the product

is an odd function. Integrating any odd function over the entire real line yields zero:

- (iv)

-

Normalization: Using the integral representation of

given by

and Fubini’s theorem to interchange integrals, we compute

□

15.4. Regularity and Spectral Decay

Theorem 24. [Regularity and Spectral Decay] Let denote the hyperbolic-modular activation kernel associated with parameters and . Then:

- (i)

- (ii)

Derivative decay: For every

, there exist constants

and

such that

- (iii)

Fourier decay: For every

, there exists

such that

Proof. (i) Smoothness.. The kernel

is constructed from compositions and products of elementary analytic functions, notably the hyperbolic tangent

, which is entire on

. As the composition and multiplication of

functions preserve smoothness, we obtain (

339).

(ii) Derivative decay. Let

be the generating profile of

, defined so that

in the symmetrized case. The analyticity strip of

implies exponential decay of derivatives on the real axis. More precisely, by repeated differentiation,

where

is a polynomial whose coefficients depend on

and

q. Taking absolute values and bounding polynomial terms by constants

yields

Since is a linear combination of translates/reflections of , the same bound holds with in (340).

(iii) Fourier decay. The Paley–Wiener theorem asserts that if

extends to an entire function bounded by

in a horizontal strip, then

belongs to the Schwartz space

. The exponential decay from (340) implies that

satisfies these analytic bounds, hence

which is exactly the decay property (

341). □

Remark. The derivative bound (340) ensures that acts as a spectrally localized mollifier, with its Fourier transform exhibiting super-polynomial decay. This is crucial for the spectral regularization properties of ONHSH operators, as it guarantees negligible high-frequency leakage and supports minimax-optimal convergence in anisotropic Besov norms.

15.5. Regularity and Spectral Decay in the Multivariate Anisotropic Setting

Theorem 25. [Regularity and Spectral Decay: Multivariate Anisotropic Case] Let

,

,

, and define the anisotropic hyperbolic-modular kernel

by

where

is the one-dimensional profile associated with

as in Theorem 15.4. Then:

- (i)

- (ii)

Anisotropic derivative decay: For every multi-index

, there exist constants

and

such that

- (iii)

Anisotropic Fourier decay: For every

, there exists

such that

Proof. (i) Smoothness.. From (

345),