0. Structure and Evolution of This Document

This manuscript represents an iterative development process. Previous versions are included in their entirety, with each successive version appending new sections to the appendices while preserving all earlier content unchanged. This additive methodology was adopted to maintain the logical consistency of the theoretical framework across iterations.

The resulting structure explains certain unconventional characteristics: appendices contain materials from different developmental stages, some concepts are approached from multiple perspectives, and analytical depth increases in later sections. This evolutionary approach documents the systematic emergence of the theoretical framework.

1. Introduction

Light, as a fundamental physical phenomenon, has been at the center of our understanding of the universe for more than three centuries. The nature of light has been constantly reinterpreted with each new revolution in physics, but a fundamental question remains open: is light a truly three-dimensional phenomenon, similar to other physical objects in our world, or is its nature fundamentally different?

Modern physics has established that the photon, the quantum of the electromagnetic field, has zero rest mass. Experimental constraints indicate an upper limit on the photon mass of kg, which is consistent with exact masslessness. However, the masslessness of the photon creates a profound contradiction with the assumption of three-dimensionality of light phenomena. A massless particle cannot have finite statistical moments of distribution — a fundamental mathematical requirement that is inconsistent with the Gaussian character of distribution expected for three-dimensional phenomena.

This contradiction points to the need to revise our basic concepts of the nature of light and space. This paper proposes a radically new view of these fundamental concepts, based on two principles that will be formulated in the next section.

For readers interested in the historical context of the development of ideas about light, space, and time, Appendix 1 presents a historical overview. It examines the contributions of key figures, including Hendrik and Ludwig Lorentz, Augustin-Louis Cauchy, Henri Poincaré, and Albert Einstein, in shaping modern views on electromagnetic phenomena and the dimensionality of space or space-time.

The evolution and historical background of the concept of time represents a separate extensive topic, which is partially addressed in the appendices, but it is important to mention now that, surprisingly, there is no unified theory of time, clocks, or measurements. The question is still unresolved, and there is no definition or consensus about what parameter is used for differentiating the Lagrangians that are at the heart of dynamics. The uncertainty of time manifests itself in other areas of physics as well.

To provide deeper insights into the implications of our proposed principles, the appendices include several thought experiments that elucidate complex concepts in more intuitive ways. Appendix 2 presents a thought experiment on "Life on a Jellyfish," exploring the fundamental limitations of coordinate systems and the nature of movement. Appendix 3 offers the "Walk to a Tree" experiment, illustrating how our perception of three-dimensional objects is inherently limited by two-dimensional projections. Appendices 4 and 5 contain thought experiments on "The World of the Unknowable," demonstrating the essential role of electromagnetic synchronizers in forming a coherent physical reality. Appendix 6 explores the "Division Bell or Circles on Water" experiment, showing how non-integer dimensionality naturally arises when introducing delays between signals. Appendix 7 examines the "String Shadows" experiment, which mathematically demonstrates the emergence of dimensionality "2-" through interaction between spaces of different dimensionality. Appendix 8 presents the "Observation in Deep Space" thought experiment, highlighting the fundamental limitations on forming physical laws with minimal information.

The paper also includes critical examinations of current theories and mathematical foundations. Appendices 9 and 10 provide critical perspectives on Special Relativity Theory through both mathematical and ontological perspectives, examining Verkhovsky’s argument on the "lost scale factor" and Radovan’s ontological critique of the relativistic concept of time. Appendix 11 discusses the Goldfain relation and its information-geometric interpretation, showing how the sum of squares of particle masses connects to the dimensionality of spaces. Appendix 12 explores the connection between Julian Barbour’s timeless physics and quantum mechanics, demonstrating how our principles lead to the formulation of quantum mechanics through information asymmetry.

For the mathematically inclined reader, several appendices offer rigorous foundations: Appendix 13 presents mathematical proofs for the connection between dimensionality and statistical distributions, establishing why massless particles must follow the Cauchy distribution at D=2. Appendix 14 analyzes information misalignment and electromagnetic synchronizers, recasting electromagnetic interactions as Bayesian processes of information updating. Appendix 15 reinterprets the time-independent Schrödinger equation as an optimization problem in Fourier space, showing how quantum mechanics emerges naturally from the interaction between spaces of different dimensionality. Finally, Appendix 16 presents the "Games in a Pool 2" thought experiment, providing an intuitive physical model for understanding quantum phenomena through the interaction of a two-dimensional medium with submerged strings of variable dimensionality, explaining wave function collapse without requiring additional postulates. Appendix 17 offers a fresh perspective on Roy Frieden’s Extreme Physical Information (EPI) principle, revealing the profound connections between information theory, dimensionality, and fundamental physics. Appendix 18 explores historicity as serial dependence, demonstrating how the transition from quantum to classical behavior emerges through information capacity constraints of synchronization channels.

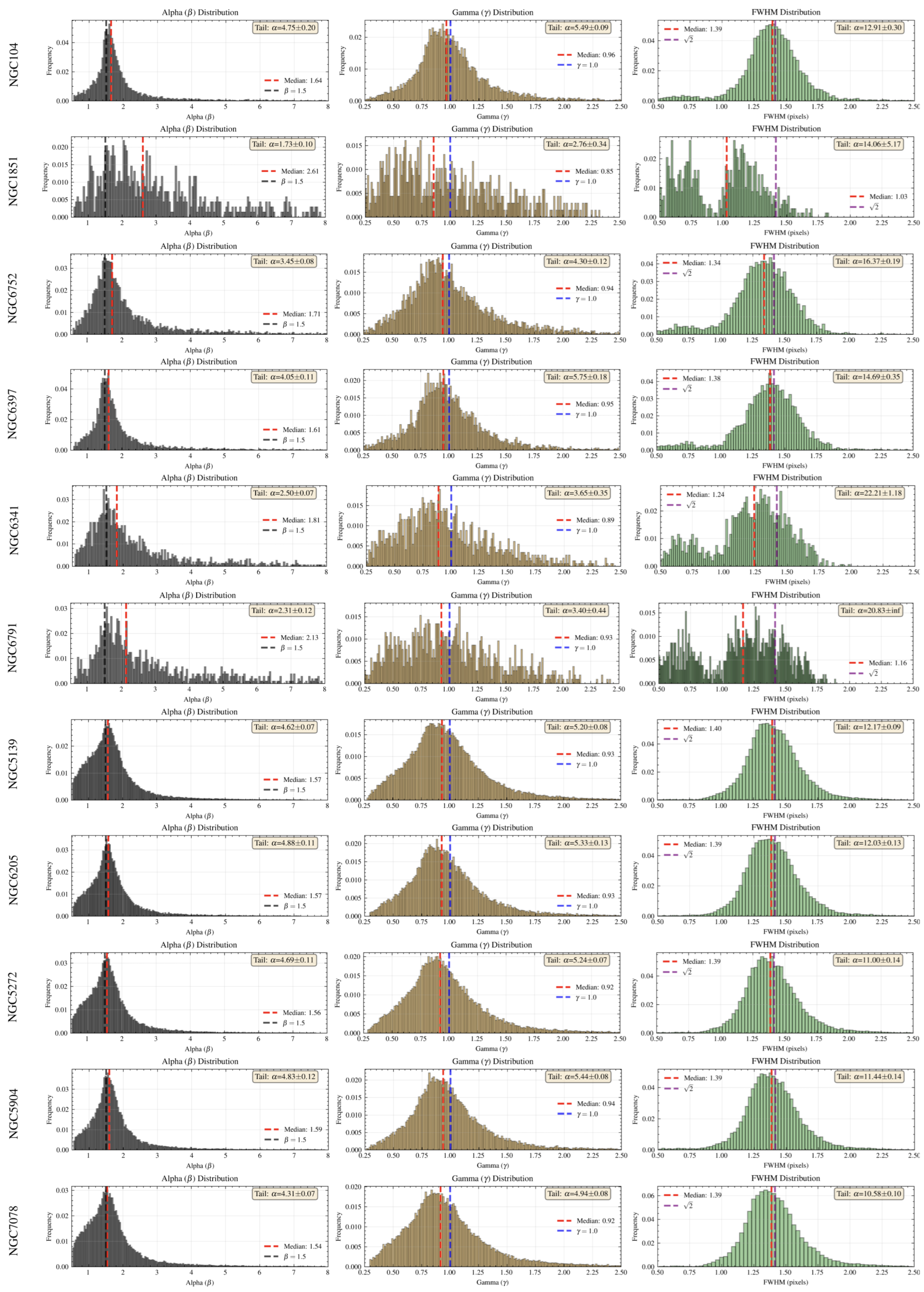

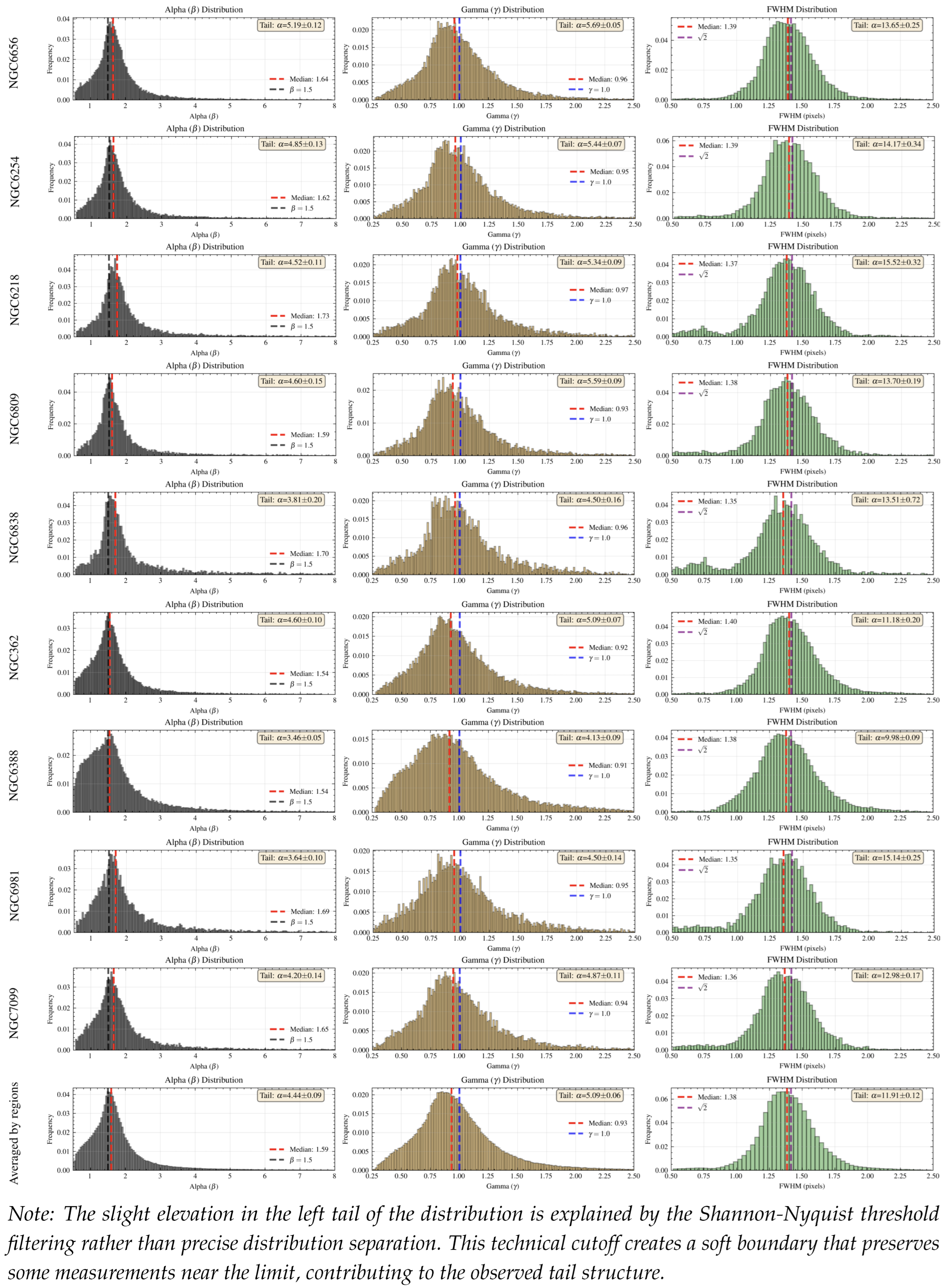

Skeptical readers may prefer to begin with Appendix 19, which provides immediate empirical argument through 300,000 Hubble observations, demonstrating the predicted signature of two-dimensional light across diverse sky regions with analysis reproducible by any programmer on standard equipment within hours.

Appendix 20 presents rigorous logical arguments demonstrating that mass cannot be a fundamental entity but emerges from electromagnetic phenomena, using practical analogies like airport X-ray screening to illustrate how the electromagnetic spectrum contains complete information while mass is merely one extracted parameter.

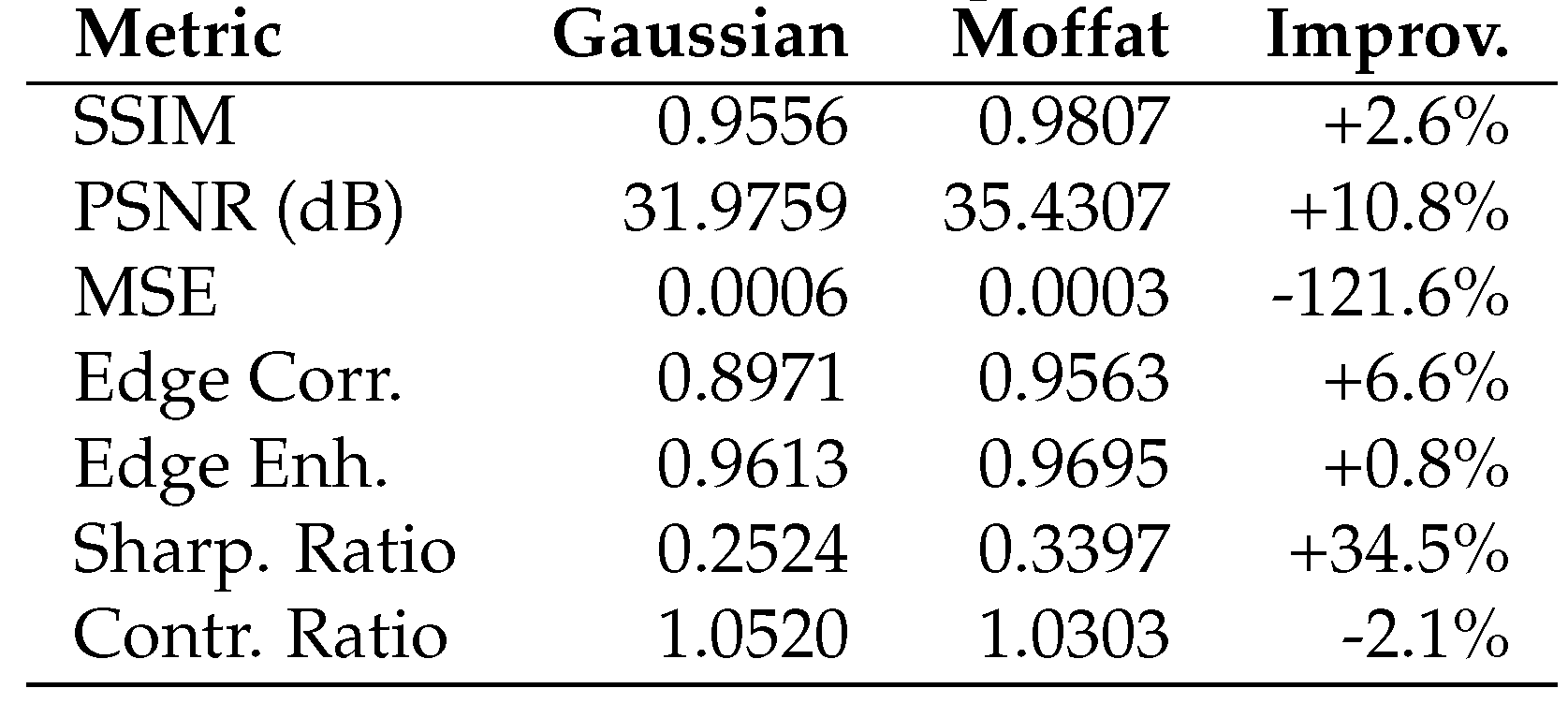

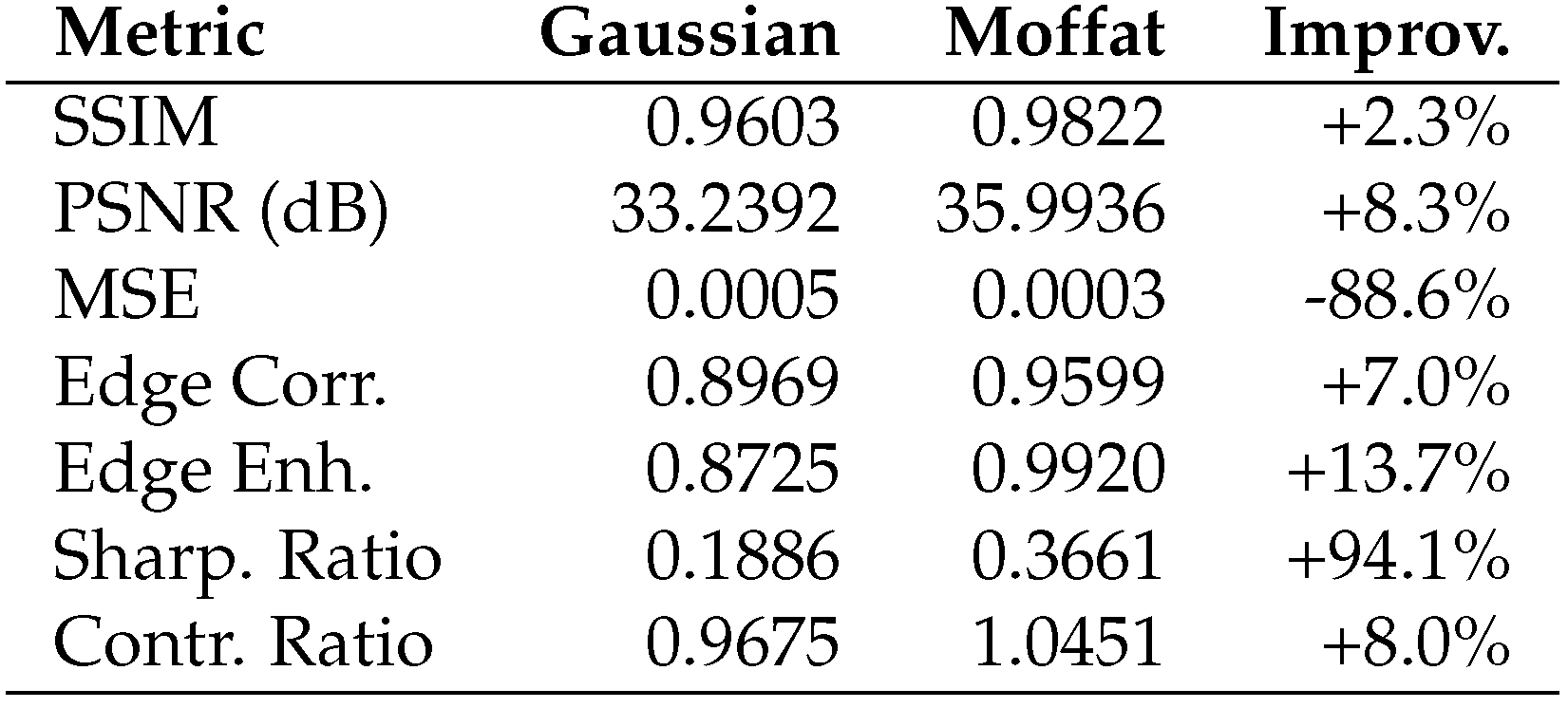

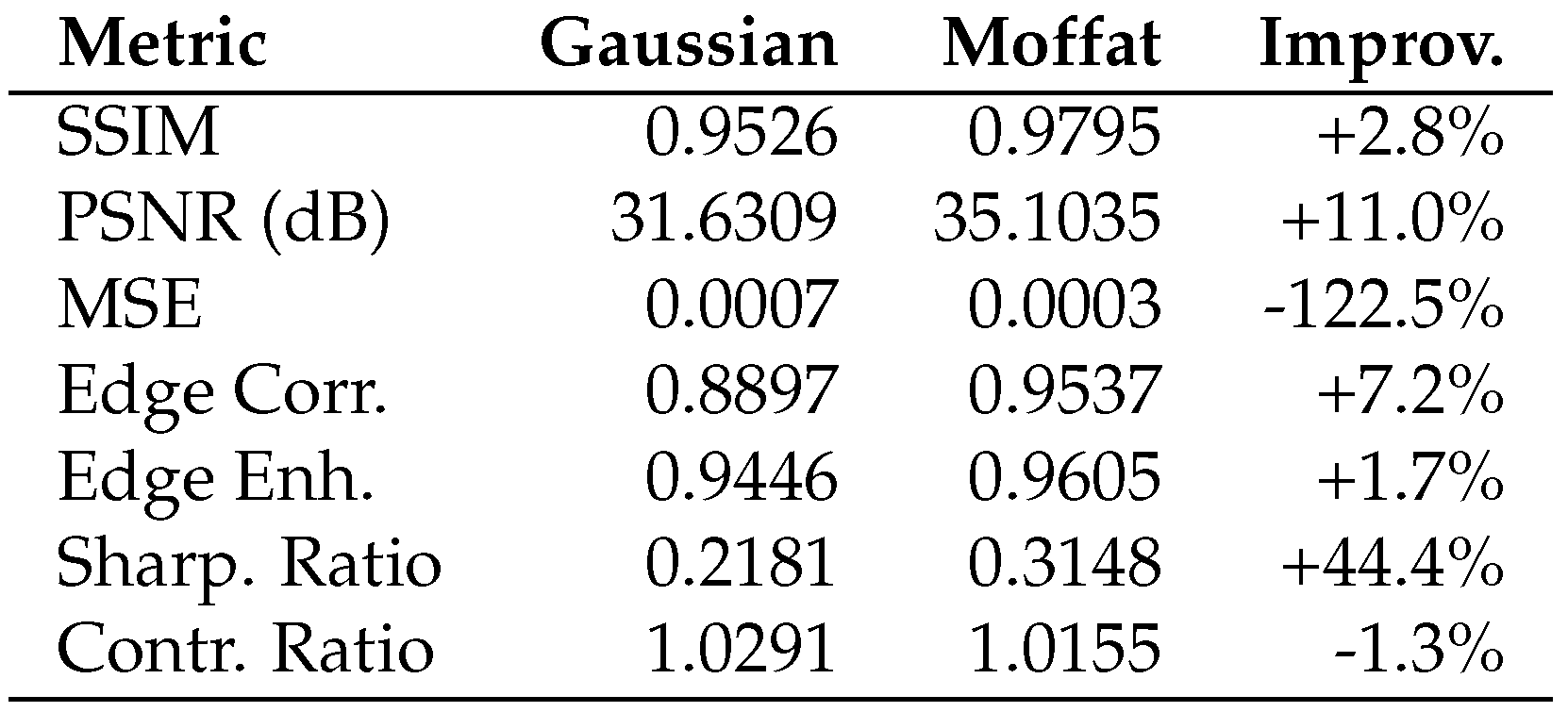

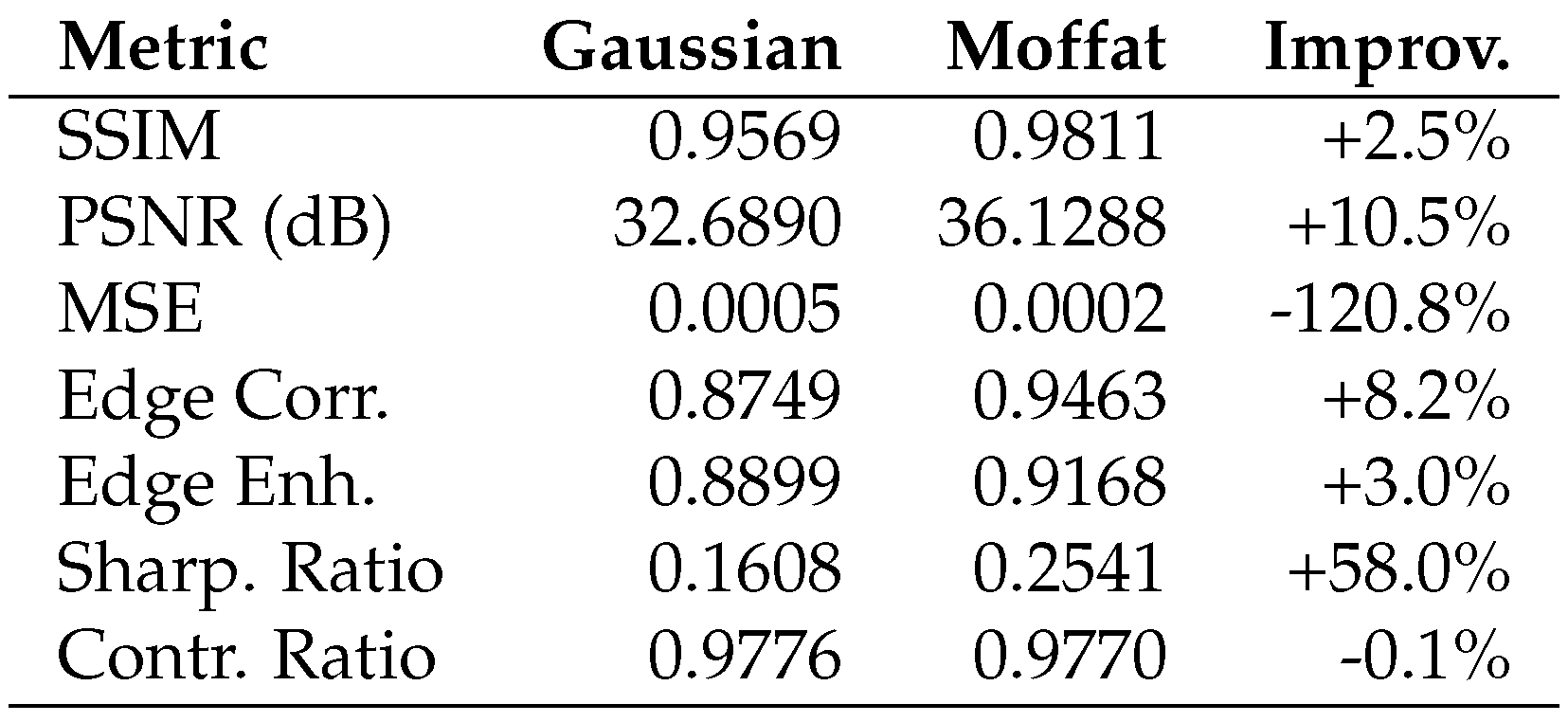

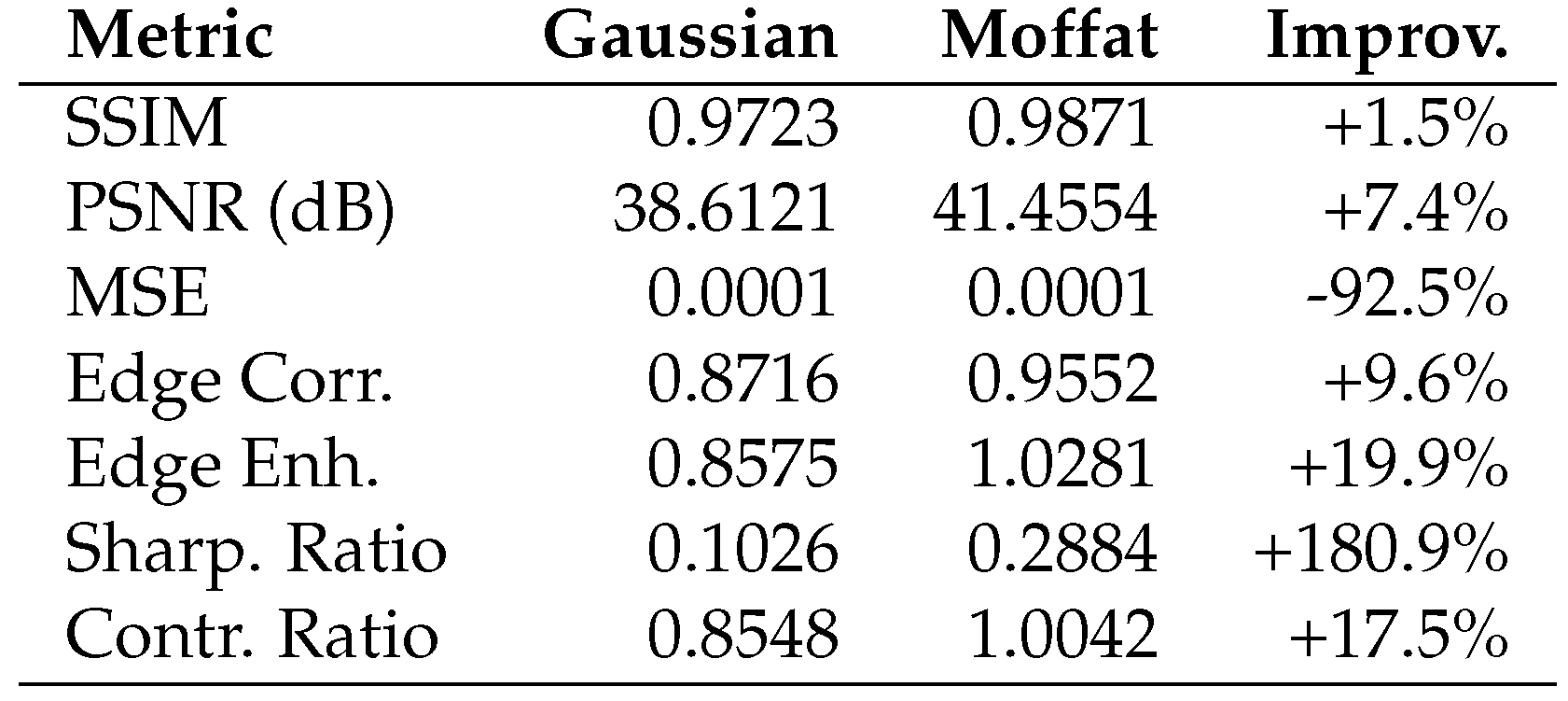

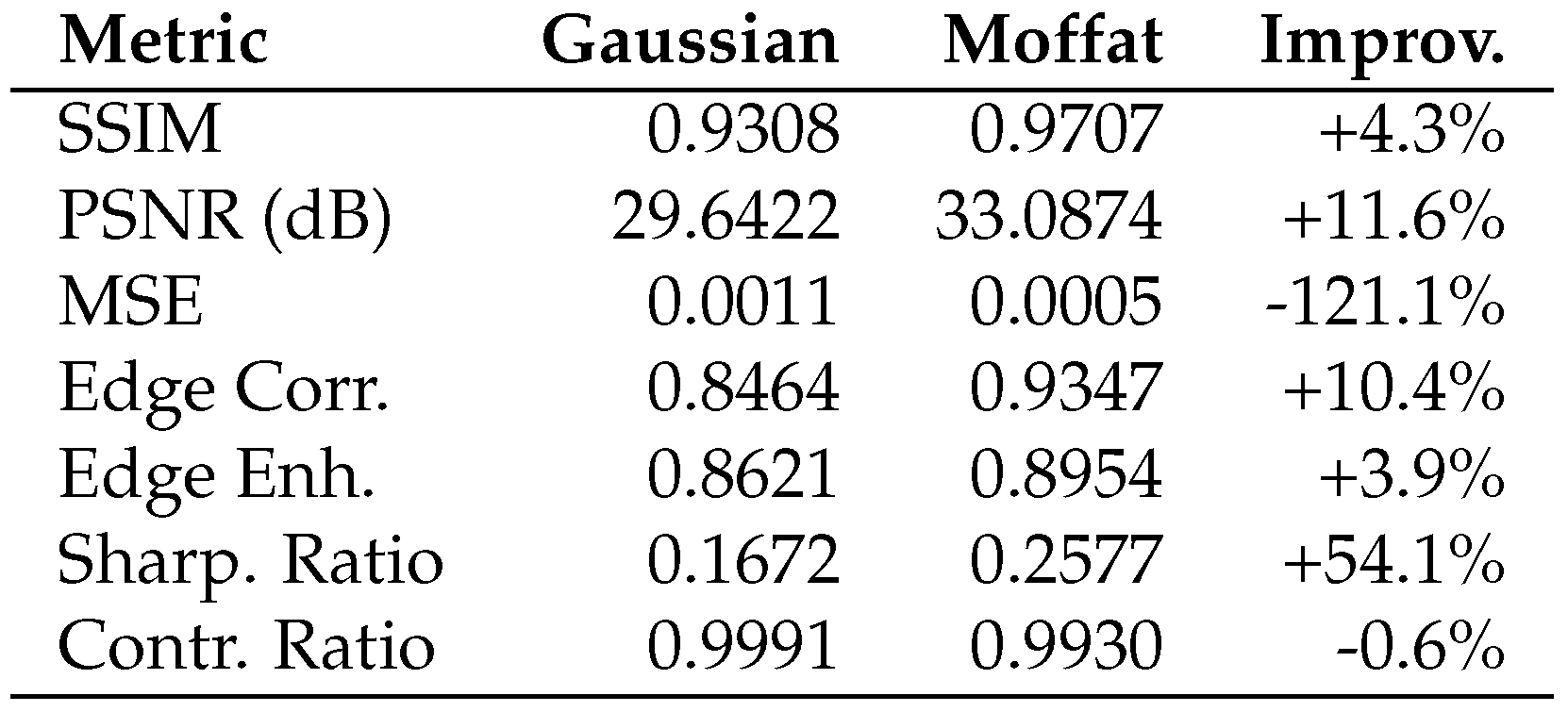

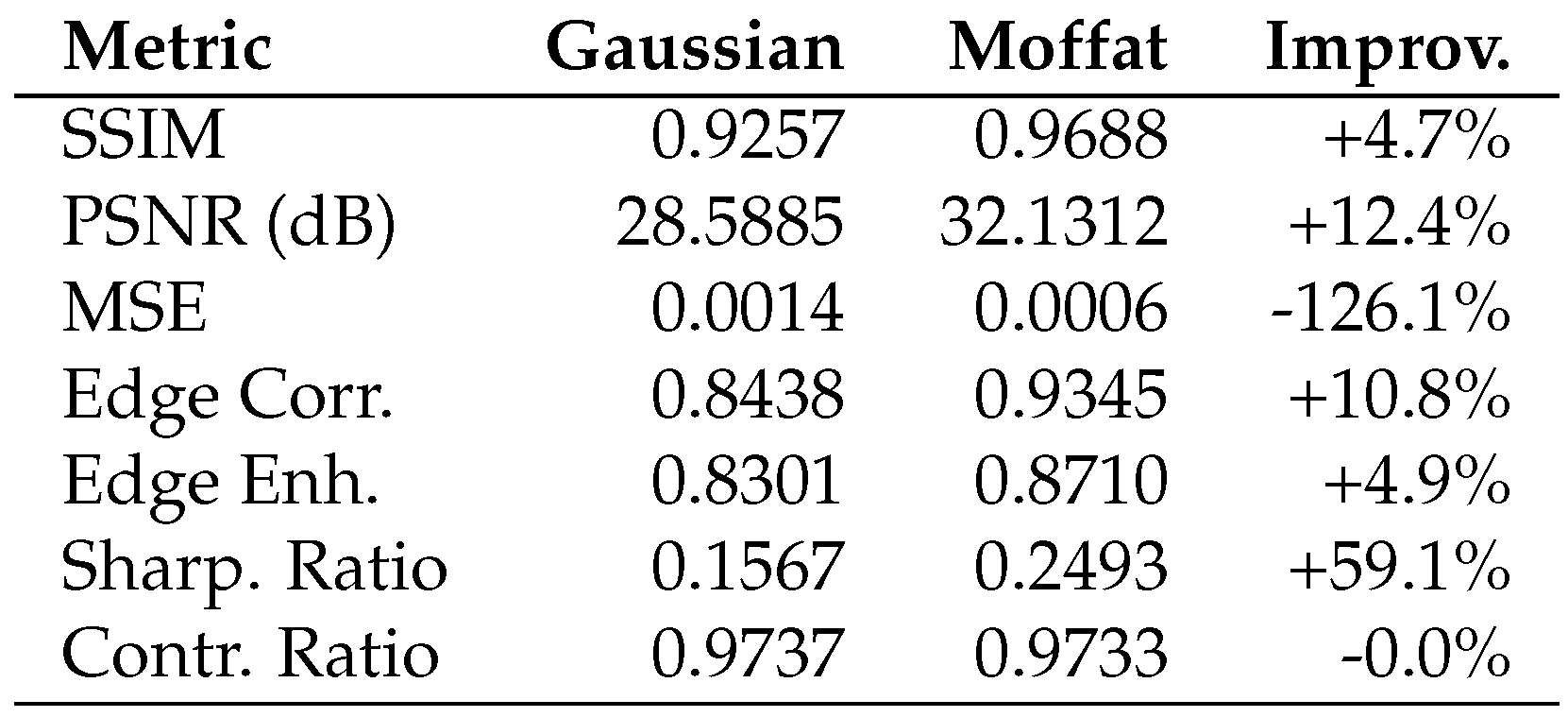

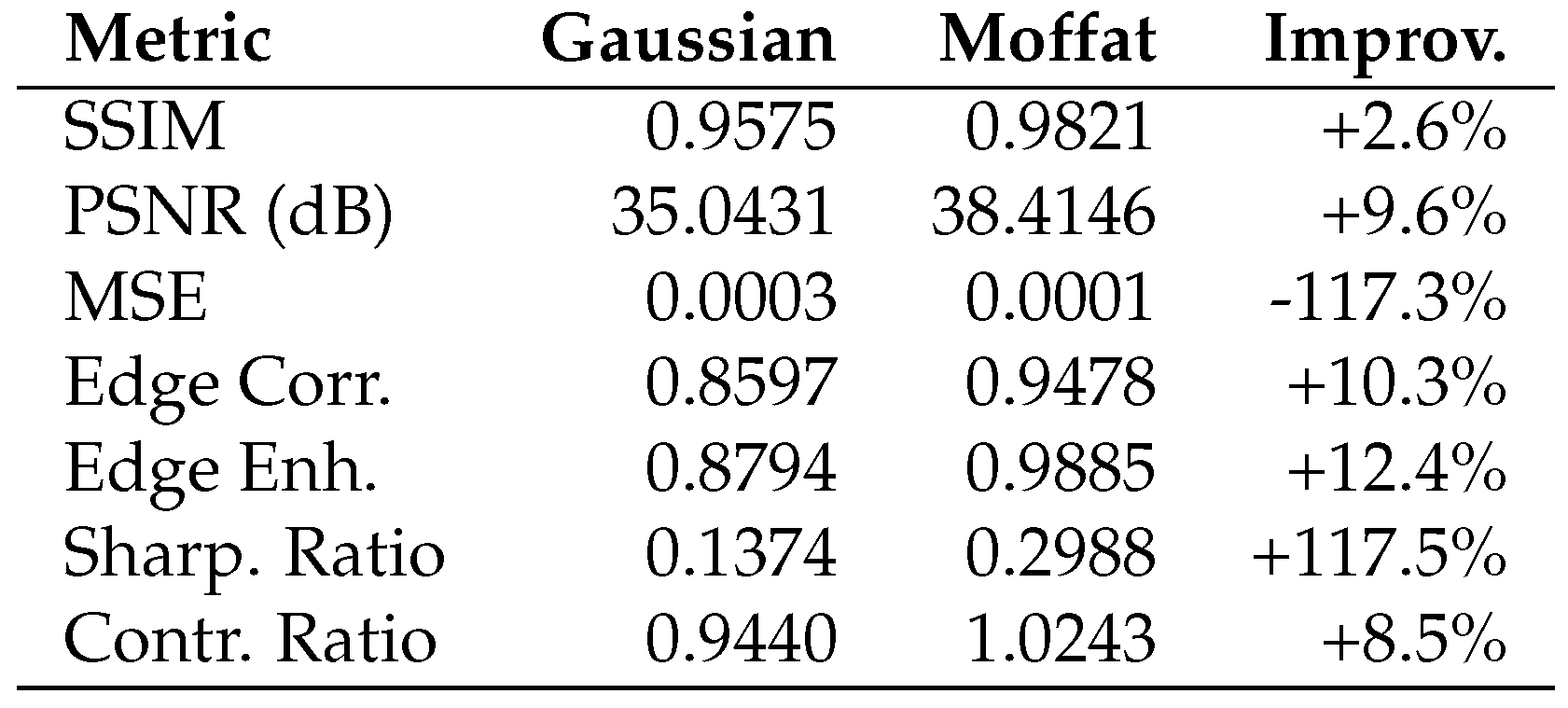

Appendix 21 is essential reading, presenting an experiment where anyone can verify these fundamental principles at home using their smartphone camera and immediately see visible improvement in their photographs — making this one of the most accessible fundamental physics experiments ever devised.

Appendix 22 presents groundbreaking evidence, demonstrating through analysis of thousands of SDSS quasar spectra that cosmological redshift exhibits systematic frequency dependence with perfect correlations, fundamentally challenging the Doppler interpretation and the expanding universe hypothesis. Appendix 23 reveals rotation as a universal dimensional codec, demonstrating mathematically how Fourier transformation enables synchronization between spaces of different dimensionality through the inherently 2D electromagnetic channel. This framework explains ubiquitous rotation in nature not as consequence of primordial angular momentum, but as the fundamental mechanism of existence itself, with gnomonic projection and Bessel function decoding providing the mathematical machinery for dimensional translation.

Appendix 24 demystifies quantum mechanics by showing the uncertainty principle as merely the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality in Fourier space, with ℏ/2 emerging from pure mathematics rather than cosmic mystery. The ultraviolet catastrophe is reinterpreted as a statistical fallacy —applying Gaussian equipartition to inherently Cauchy-distributed cavity modes — revealing Planck’s quantization as natural consequence of the Fourier-Cauchy codec under finite observation windows, not metaphysical discreteness of matter.

Appendix 25 demonstrates that all classical mechanics — from Newton’s laws to Feynman’s path integrals — represents different aspects of spectral filtering through the electromagnetic channel, with each historical formulation (Lagrangian, Hamiltonian, etc.) corresponding to distinct optimization strategies in frequency space.

Appendix 26 reveals that the second law of thermodynamics — the last refuge of time asymmetry in fundamental physics — dissolves entirely under Maximum Entropy Method analysis, with temperature emerging as the bandwidth of spectral filters rather than kinetic energy, and irreversibility arising not from cosmic initial conditions but from spectral folding during measurement, making entropy increase a trivial consequence of information loss through frequency aliasing rather than a mysterious arrow of time.

Appendix 27 shows a different and more capacious view on the phenomenon of gravity and gives a more capacious and universal reformulation of Kepler’s laws. This section is recommended to read last, as it is extremely difficult (first of all emotionally) to understand without rejection of old ontologies and language.

Appendix 28 presents arguments for why it may be time to abandon geometry as a foundation for modern physical theories. This section examines fundamental problems with basic geometric concepts — from the impossibility of defining straight lines in physical reality to the non-existence of geometric points as actual physical entities. The section demonstrates that the entire geometric edifice rests on unobservable and unmeasurable abstractions, making it an unsuitable foundation for theories meant to describe the physical world.

For comprehensive understanding, readers should first grasp the fundamental principles in the main text before exploring the supplementary materials, which provide theoretical depth and philosophical context for the core ideas.

2. Fundamental Principles

To somehow advance in understanding the essence of time, it is proposed to replace the direct question "What is time?" with two connected and more precise questions.

The first question in different connotations can be formulated as:

"What is the mechanism of synchronization?"

"Why is it the way we observe it, and not different?"

"Why is there a need for synchronization at all?"

"Why, in the absence of synchronization, would our U-axiom be broken, the laws of physics here and there would be different, the experimental method would not be useful, the very concept of universal laws of physics would not have happened?"

The essence of the second question in different connotations:

"Why don’t we observe absolute synchronization?"

"What is the cause of desynchronization?"

"How do this chaos (desynchronization) and order (synchronization) balance?"

"Why is it useful for us to introduce the dichotomy of synchronizer and desynchronizer as a concept?"

The desired answers should be as concise, economical, and universal as possible, have maximum explanatory power and logical consistency (not leading to two or more logically mutually exclusive consequences), open new doors for research rather than close them, and push towards new questions for theoretical and practical investigations, not just prohibitions.

The desired answers should provide a clear zone of falsification and verification.

Without a clear answer to these questions, it is impossible to build a theory of measurements.

Here are the answers to these questions from this work:

Principle I: Electromagnetic phenomena are two-dimensional and follow the Cauchy distribution law.

Principle II: There exists a non-integer variable dimensionality of spaces.

These principles are sufficient.

3. Theoretical Foundation

3.1. Dimensional Nature of Electromagnetic Phenomena

It is traditionally assumed that space has exactly three dimensions, and all physical phenomena exist in this three-dimensional space. In some interpretations, they speak of 3+1 or 4-dimensional space, where the fourth dimension is time. However, upon closer examination, the dimensionality of various physical phenomena may differ from the familiar three dimensions. By dimensionality D, we mean the parameter that determines how physical information scales with distance.

For electromagnetic phenomena, there are serious theoretical grounds to assume that their effective dimensionality is

(exactly). Let’s consider the key arguments (a more detailed analysis of numerous arguments for the two-dimensional nature of electromagnetic phenomena is presented in the work [

1]):

3.1.1. Wave Equation and Its Solutions

The wave equation in

D-dimensional space has the form:

This equation demonstrates qualitatively different behavior exactly at

, where solutions maintain their form without geometric dispersion:

At any dimensionality above or below 2.0, waves inevitably distort. At , waves geometrically scatter as they propagate, with amplitude decreasing as . At , waves experience a form of "anti-dispersion", with amplitude increasing with distance. Only at exactly do waves maintain perfect coherence and shape — a property observed in electromagnetic waves over astronomical distances.

3.1.2. Green’s Function for the Wave Equation

The Green’s function for the wave equation undergoes a critical phase transition exactly at

:

The case represents the exact boundary between two fundamentally different regimes, transitioning from power-law decay to power-law growth. The logarithmic potential at exactly represents a critical point in the theory of wave propagation.

3.1.3. Constraints on Parameter Measurement

A profound but rarely discussed property of electromagnetic waves is the fundamental limitation on the number of independent parameters that can be simultaneously measured. Despite centuries of experimental work with electromagnetic phenomena, no experiment has ever been able to successfully measure more than two independent parameters of a light wave simultaneously.

This limitation is not technological, but fundamental. For a truly three-dimensional wave, we should be able to extract three independent parameters corresponding to the three spatial dimensions. However, electromagnetic waves consistently behave as if they possess only two degrees of freedom — exactly what we would expect from a fundamentally two-dimensional phenomenon.

3.2. Connection Between Dimensionality D=2 and the Cauchy Distribution

The connection between exact two-dimensionality (D=2) and the Cauchy distribution is not coincidental but reflects deep mathematical and physical patterns.

For the wave equation in two-dimensional space, the Green’s function describing the response to a point source has a logarithmic form:

The gradient of this function, corresponding to the electric field from a point charge in 2D, is proportional to:

Wave intensity is proportional to the square of the electric field:

It is precisely this asymptotic behavior

that is characteristic of the Cauchy distribution. In a one-dimensional section of a two-dimensional wave (which corresponds to measuring intensity along a line), the intensity distribution will have the form:

which exactly corresponds to the Cauchy distribution.

3.2.1. Lorentz Invariance and Uniqueness of the Cauchy Distribution

From the perspective of probability theory, the Cauchy distribution is the only candidate for describing massless fields for several fundamental reasons:

1. Exceptional Lorentz Invariance: The Cauchy distribution is the only probability distribution that maintains its form under Lorentz transformations. Under scaling and shifting (), the Cauchy distribution transforms into a Cauchy distribution with transformed parameters. This invariance with respect to fractional-linear transformations is a mathematical expression of invariance with respect to Lorentz transformations.

2. Unique Connection with Masslessness: Among all stable distributions, only the Cauchy distribution has infinite moments of all orders. This mathematical property is directly related to the massless nature of the photon — any other distribution having finite moments is incompatible with exact masslessness.

3. Conformal Invariance: Massless quantum fields possess conformal invariance — symmetry with respect to scale transformations that preserve angles. In statistical representation, the Cauchy distribution is the only distribution maintaining conformal invariance.

Thus, the Cauchy distribution is not an arbitrary choice from many possible candidates, but the only distribution satisfying the necessary mathematical and physical requirements for describing massless fields within a Lorentz-invariant theory, which has very strong experimental support.

3.2.2. Manifestations of the Cauchy Distribution in Quantum Physics

Notably, the Cauchy distribution arises in many resonant phenomena of quantum physics. At the quantum level, the interaction between photons and charged particles has a deeply resonant nature:

1. In quantum electrodynamics (QED), the interaction between light and matter is carried out through the exchange of virtual photons. Mathematically, the photon propagator has the form , where is an infinitesimally small quantity defining the causal structure of the theory. In coordinate representation, this leads to power-law decay of the potential, characteristic of the Cauchy distribution. This structure of the propagator with a pole in the complex plane is a direct mathematical consequence of the photon’s masslessness.

2. Spectral lines of atomic transitions have a natural broadening, the shape of which is described by the Lorentz (Cauchy) distribution. This is a direct consequence of the uncertainty principle and the finite lifetime of excited states.

3. In scattering theory, the resonant cross-section as a function of energy has the form of the Breit-Wigner distribution, which is essentially a Cauchy distribution with a physical interpretation of parameters.

This universality indicates that the Cauchy distribution is not just a mathematical convenience, but reflects the fundamental nature of massless quantum fields.

Thus, if light (more strictly speaking, electromagnetic phenomena; I said "light" only for greater clarity) is indeed a two-dimensional phenomenon, its intensity in the shadow from a thin object should follow the Cauchy distribution (more precisely, half-Cauchy, if we are talking about shadow intensity, as we need to make an adjustment for only the positive region).

3.3. Relationship Between the sinc² Function and the Cauchy Distribution

In classical diffraction theory, the sinc² function is often used to describe the intensity of the diffraction pattern from a rectangular slit in the Fraunhofer approximation. However, this function, convenient for mathematical analysis, can be considered more of a "mathematical crutch" rather than a reflection of fundamental physical reality.

3.3.1. Origin of the sinc² Function in Diffraction Theory

The sinc² function appears in diffraction theory as a result of the Fourier transform of a rectangular function describing the transmission of light through a rectangular slit:

where

a is the slit width,

is the wavelength of light,

is the diffraction angle.

This mathematically elegant solution, however, is based on a series of idealizations:

Assumption of an ideal plane wave

Perfectly rectangular slit with sharp edges

Far field (Fraunhofer approximation)

Any deviation from these conditions (which is inevitable in reality) leads to deviations from the sinc² profile.

3.3.2. Asymptotic Behavior of sinc² and the Cauchy Distribution

Despite apparent differences, the sinc² function and the Cauchy distribution have the same asymptotic behavior for large values of the argument. For large

x:

which coincides with the asymptotics of the Cauchy distribution:

This coincidence is not accidental and indicates a deeper connection between these functions.

3.4. Nature of Mass

The concept of the two-dimensional nature of electromagnetic phenomena and the Cauchy distribution allows us to take a fresh look at the fundamental nature of mass. Traditionally, mass is considered an inherent property of matter, but deeper analysis reveals surprising patterns related to dimensionality.

3.4.1. Absence of Mass at D=2

Remarkably, at an effective space dimensionality of exactly D=2.0, mass as a phenomenon simply cannot exist. This is not a coincidental coincidence, but a consequence of deep mathematical and physical patterns:

1. In two-dimensional space, the Cauchy distribution is the natural statistical description, which does not have finite moments — a property directly related to masslessness.

2. For a space with D=2.0, the Green’s function acquires a logarithmic character, which creates a critical point at which massive solutions are impossible.

3. Only when deviating from D=2.0 (both higher and lower) does the possibility of massive particles and fields arise.

This fundamental feature explains why the electromagnetic field (with effective dimensionality D=2.0) is strictly massless — not due to some random properties, but due to the impossibility of the very concept of mass in a two-dimensional context.

3.4.2. Interpretation of the Relations and

The classical relationships between energy, mass, and frequency acquire new meaning in the context of the theory of variable dimensionality:

1. The relation connects energy with mass through the square of the speed of light. The quadratic nature of this dependence is not accidental — indicates the fundamental two-dimensionality of the synchronization process carried out by light. In fact, this expression can be considered as a measure of the energy needed to synchronize a massive object with a two-dimensional electromagnetic field.

2. The relation connects energy with angular frequency through Planck’s constant. In the context of our theory, represents intensity, speed (without a temporal context), or a measure of synchronization; it is also true that the faster synchronization occurs, the higher the energy. Planck’s constant ℏ acts as a fundamental measure of the minimally distinguishable divergence between two-dimensional and three-dimensional descriptions, fixing the threshold value of informational minimally recordable misalignment; it can be perceived as discretization.

These two formulas can be combined to obtain the relation

, which can be rewritten as:

In this expression, mass appears not as a fundamental property, but as a measure of informational misalignment between two-dimensional (electromagnetic) and non-two-dimensional (material) aspects of reality, normalized by the square of the speed of light.

3.4.3. Origin of Mass as a Dimensional Effect

Combining the ideas presented above, we arrive at a new interpretation of the nature of mass:

1. Mass arises exclusively as a dimensional effect — the result of interaction between spaces of different effective dimensionality.

2. For phenomena with effective dimensionality exactly D=2.0 (such as the electromagnetic field), mass is impossible for fundamental mathematical reasons.

3. For phenomena with effective dimensionality , mass is a measure of informational misalignment with the two-dimensional structure of electromagnetic interaction space.

4. Planck’s constant ℏ fixes the minimum magnitude of this dimensional divergence that can be registered in an experiment.

This concept radically changes our understanding of mass, transforming it from a fundamental property of matter into an emergent phenomenon arising at the boundary between spaces of different dimensionality.

4. Zones of Falsification and Verification

One of the possible zones of verification and falsification currently experimentally accessible, and inexpensive, which is also important, is in the detailed examination of the shadow from a super-thin object.

The essence of the question can be easily represented as a reverse slit experiment (instead of studying light passing through a slit, we study the shadow from a single thin object). According to the proposed theory, the spatial distribution of light intensity in the shadow region should demonstrate a slower decay, characteristic of the Cauchy distribution (with "heavy tails" decaying as ), than what is predicted by the standard diffraction model with the function . Although asymptotically at large distances the function also decays as , the detailed structure of the transition from shadow to light and the behavior in the intermediate region should be better described by a pure Cauchy distribution (or half-Cauchy for certain experiment geometries).

For conducting such an experiment, it may be preferable to use X-ray radiation instead of visible light, as this will allow working with objects of smaller sizes and achieving better spatial resolution. Modern laboratories equipped with precision detectors with a high dynamic range are fully capable of implementing such an experiment and reliably distinguishing these subtle features of intensity distribution.

It is important to note separately that the actual observation of a shape different from the Cauchy family, also with a high degree of statistical significance and with reliable exclusion of external noise, will uncover a huge tension in modern physics and pose the question pointedly: "Why in a bunch of independent experiments do we record the phenomenon of Lorentz invariance with high reliability?" In this sense, even if reality gives a non-Cauchy form (which would seriously undermine the theory of this work), the experiment is win-win, as a negative result will also be fundamentally useful and the direct costs of asking this question to reality are relatively small.

4.1. Optimization of Optical Fiber Transmission Using Cauchy Distribution

Another practical verification approach involves examining the transmission characteristics of single-mode optical fibers. Single-mode optical fibers are known to transmit light optimally at specific wavelengths, and this property can be used to test our fundamental principles.

The proposed experiment would consist of:

Using standard single-mode optical fiber and varying the input light frequency systematically

Measuring the output signal’s intensity profile with high-precision photodetectors

Analyzing the degree of conformity between the output signal’s intensity distribution and the Cauchy distribution

Determining whether optimal transmission conditions coincide with maximum conformity to the Cauchy distribution

If electromagnetic phenomena truly follow the Cauchy distribution as proposed, then tuning the wavelength or frequency to optimize the conformity with the Cauchy distribution at the output should result in measurably improved transmission characteristics. This optimization method would differ from conventional approaches that typically focus on minimizing attenuation without considering the statistical distribution of the transmitted light.

This experimental approach offers several advantages:

It uses widely available equipment in standard optical laboratories

The controlled environment minimizes external variables

Precise measurements can be made with existing technology

Results could be immediately applicable to telecommunications

A significant deviation from the expected correlation between optimal transmission and Cauchy distribution conformity would challenge our theoretical framework, while confirmation would provide strong support and potentially revolutionize optical communication optimization methods.

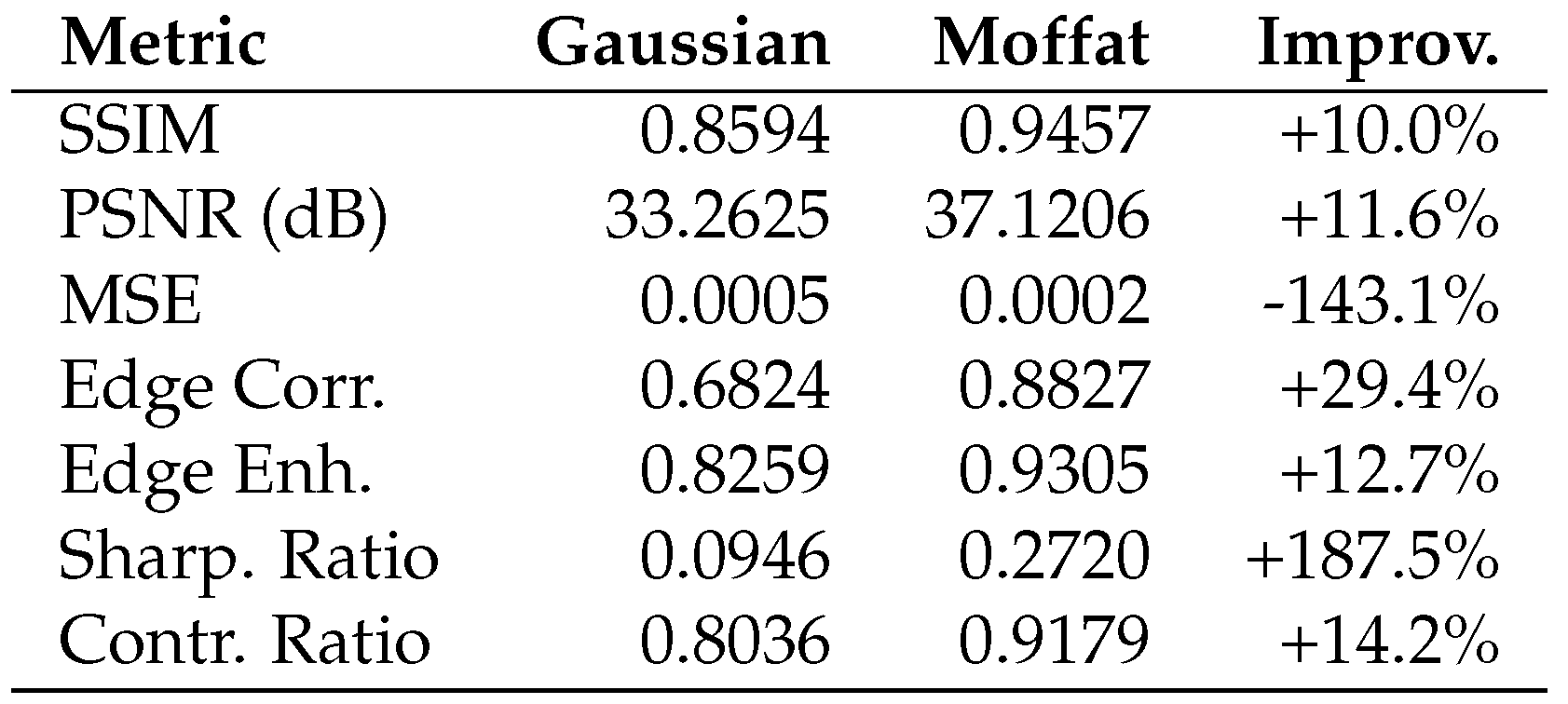

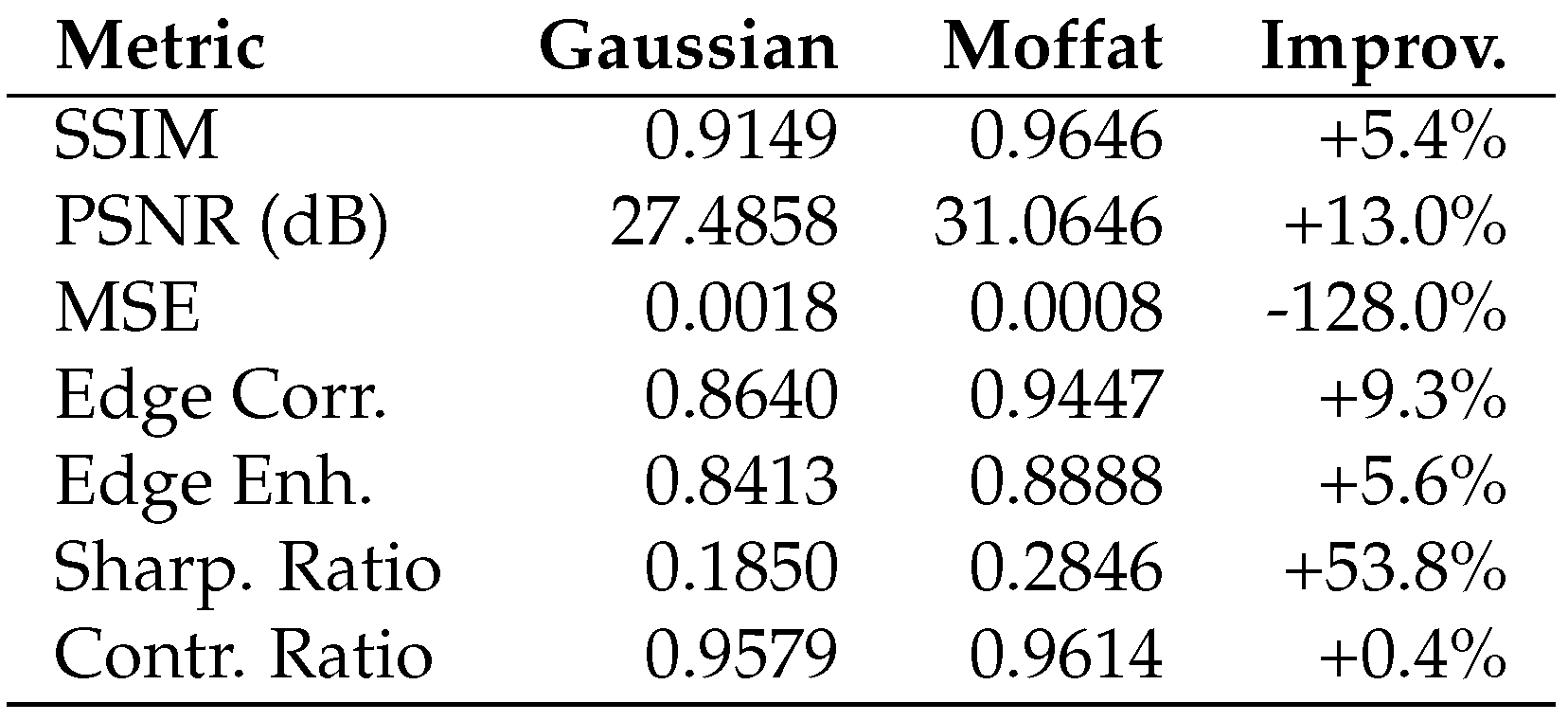

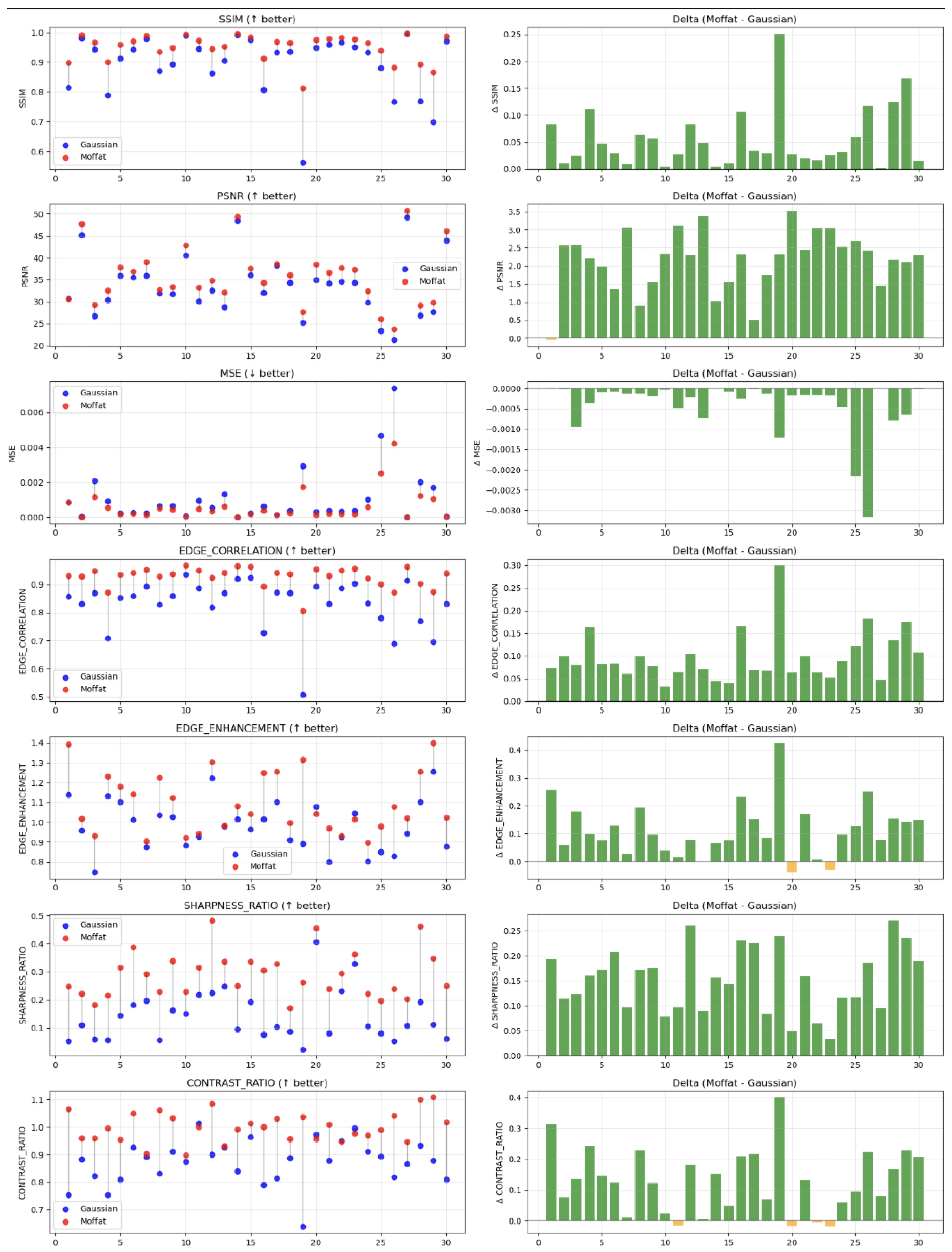

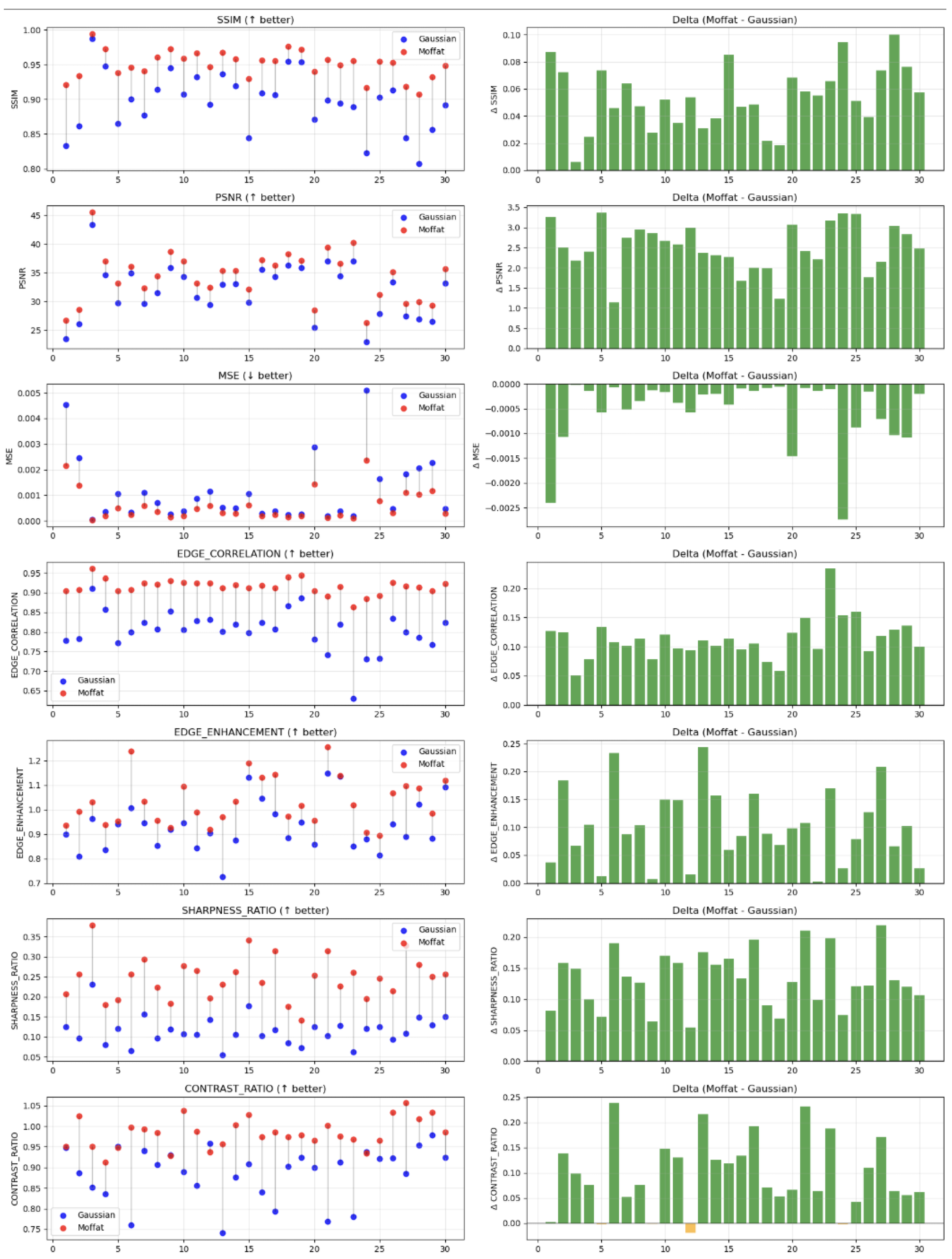

4.2. Enhancement of Astronomical Images Through Cauchy Kernel Processing

A particularly elegant verification method leverages existing astronomical data archives, applying novel processing techniques based on the Cauchy distribution:

Select celestial objects or regions that have been observed multiple times with increasingly powerful telescopes (e.g., objects observed by both Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope)

Apply Cauchy-based deconvolution algorithms to the lower-resolution images

Compare these processed images with higher-resolution observations of the same targets

Assess whether Cauchy processing reveals details that were later confirmed by higher-resolution instruments

Counter-intuitively, while the Cauchy distribution has "heavy tails" that might suggest image blurring, its alignment with the fundamental two-dimensional nature of electromagnetic phenomena could actually enhance detail recovery. If light propagation truly follows the Cauchy distribution, then processing algorithms based on this distribution should provide more physically accurate reconstructions than traditional methods based on Gaussian or sinc functions.

A successful demonstration would not only verify our theoretical principles but could dramatically advance observational astronomy by:

Extracting previously unresolved details from existing astronomical archives

Enhancing the effective resolution of current telescopes

Improving detection capabilities for faint and distant objects

Providing a more theoretically sound foundation for image processing in astronomy

This experiment is particularly valuable as it can be conducted using existing data, requiring only computational resources rather than new observations.

4.3. Satellite Communications and Antenna Design Based on Cauchy Distribution

The two-dimensional nature of electromagnetic phenomena and the Cauchy distribution can also be tested through experiments with satellite communications and antenna design:

Design antenna geometries optimized for the Cauchy distribution rather than traditional models

Optimize satellite communication frequencies based on conformity to the Cauchy distribution

Measure and compare signal propagation characteristics, reception clarity, and resistance to interference

Analyze whether antenna radiation patterns more closely follow the Cauchy distribution than conventional models predict

If the proposed principles are correct, antennas designed according to Cauchy distribution principles should demonstrate measurable performance improvements over conventional designs, particularly in aspects such as:

Effective range and signal clarity

Directional precision and focusing capabilities

Resistance to environmental interference

Energy efficiency in signal transmission and reception

This experimental approach is particularly valuable because it:

Can be implemented with relatively minor modifications to existing equipment

Provides quantitatively measurable performance metrics

Has immediate practical applications in telecommunications

Tests the theory in open-air environments with real-world conditions

A positive outcome would not only validate our theoretical framework but could lead to significant advancements in wireless communication technology, potentially revolutionizing fields from mobile communications to deep space transmissions.

4.4. Comparison with Existing Experimental Data

4.4.1. Computational Imaging and the Cauchy Distribution

Independent research in computational imaging has discovered that the Cauchy distribution provides superior modeling of optical phenomena compared to the traditionally assumed Gaussian distribution. This empirical finding directly supports the theoretical framework presented in this paper.

Three related studies demonstrate this superiority across different imaging applications. In video surveillance systems [

2], researchers found that modeling the point spread function (PSF) with a Cauchy distribution significantly improved motion detection accuracy, particularly in low-light conditions where Gaussian models fail. The critical insight was that pixel intensity ratios in defocused regions follow heavy-tailed distributions — precisely what the Cauchy distribution captures but the Gaussian cannot.

This advantage extends to depth recovery from single images. When estimating scene depth from defocus blur [

3], the Cauchy-based PSF model extracted more accurate depth information than Gaussian-based methods. The improvement was most pronounced at object edges and in regions with varying illumination — conditions where the heavy tails of the Cauchy distribution better represent the actual light propagation.

Further refinement of this approach [

4] revealed why the Cauchy distribution succeeds where Gaussian models fail. Light diffracted at edges and propagating through optical systems exhibits intensity patterns with power-law decay (

), not the exponential decay of Gaussian distributions. This power-law behavior is the signature of the Cauchy distribution and matches the theoretical prediction for massless electromagnetic fields.

The significance of these findings cannot be overstated. These researchers were not testing fundamental physics theories — they were solving practical imaging problems. Yet they independently discovered that light behavior is better described by the Cauchy distribution, exactly as predicted by the principle that electromagnetic phenomena are two-dimensional and follow the Cauchy distribution law (Principle I).

This empirical validation is particularly relevant for the proposed astronomical image enhancement experiment. If switching from Gaussian to Cauchy kernels improves image quality in everyday photography and depth sensing, where light paths are short and atmospheric effects dominate, the improvement should be even more dramatic for astronomical images where light has propagated through vast distances of space. The success of Cauchy-based methods in computational imaging strongly suggests that the proposed experiments will yield positive results.

4.4.2. Optical Fiber Sensing and the Cauchy Distribution

A particularly compelling validation comes from optical fiber sensing, where light propagates through a controlled medium over long distances. Han et al. (2023) [

5] achieved remarkable improvements in Brillouin optical time domain reflectometry (BOTDR) by applying a Cauchy proximal splitting (CPS) algorithm to optical signal processing.

Their results demonstrate a 12.7 dB improvement in signal-to-noise ratio and an 11-fold increase in measurement accuracy (from 4.78 MHz to 0.43 MHz). To understand the significance of this improvement, it is important to note that typical algorithmic enhancements in optical fiber signal processing yield 1-5 dB improvements. For example, advanced digital signal processing methods like digital backpropagation typically achieve 1-3 dB gains, while specialized techniques rarely exceed 5-6 dB. A 12.7 dB improvement — representing an 18.6-fold increase in signal power — from merely changing the penalty function in an optimization algorithm is exceptional and suggests a fundamental resonance with the underlying physics.

The physical significance is crucial for understanding why this result strongly supports the theoretical framework. Brillouin scattering involves the interaction between photons and acoustic phonons in the fiber — a purely optical phenomenon where light behavior is directly measured. The CPS algorithm employs a Cauchy proximal operator that iteratively identifies signal components conforming to the Cauchy distribution. The exceptional performance improvement suggests that the algorithm is not merely removing noise but recovering the intrinsic statistical structure of the optical signal itself.

This finding is particularly important because it represents an independent discovery in a practical engineering context. The researchers were optimizing for signal quality, not testing fundamental physics theories, yet they found that assuming a Cauchy distribution for the optical signal yielded unprecedented improvements. This provides strong empirical support for the proposed optical fiber transmission experiment, where designing systems around the Cauchy distribution principle should yield similar dramatic enhancements. The fact that such improvements emerge in real-world fiber optic systems — where light propagates over kilometers through a well-characterized medium — suggests that the Cauchy distribution reflects a fundamental property of electromagnetic propagation.

4.4.3. Experiments with Diffraction on a Single Edge

Experiments on diffraction on a half-plane (single edge) have allowed high-precision measurements of the light intensity profile behind the obstacle. For example, Ganci’s studies (2010) [

6] were aimed at verifying Sommerfeld’s rigorous solution for diffraction on a half-plane. These experiments confirmed the theoretical predictions, including the phase shift of the wave diffracted at the edge, which is a key property of the theory of diffraction waves at the boundary.

Recently, Mishra et al. (2019) [

7] published a study in Scientific Reports in which they used the built-in edge of a photodetector as a diffracting aperture for mapping the intensity of the bands. They observed a clear pattern of Fresnel diffraction from the edge and even noted subtle effects (such as alternating amplitudes of bands due to a slight curvature of the edge) in excellent agreement with wave theory.

These edge diffraction experiments provide quantitative data on intensity profiles in several orders of magnitude, and their results are consistent with classical models (e.g., Fresnel integrals), confirming the nature of the intensity distribution in the "tails" far from the geometric shadow.

4.4.4. Diffraction on a Thin Wire

Thin wires (or fibers) create diffraction patterns similar to those from a single slit (according to Babinet’s principle). A notable high-precision study was conducted by Ganci (2005) [

8], who investigated Fraunhofer diffraction on a thin wire both theoretically and experimentally. This work measured the intensity profile behind a stretched wire using a laser and analyzed it statistically.

Most importantly, it showed that assuming an ideal plane wave illumination results in a characteristic intensity profile with pronounced heavy tails (side lobes), but real deviations (e.g., a Gaussian profile of the laser beam) can cause systematic differences from the ideal pattern. In fact, Ganci demonstrated that naive application of Babinet’s principle can be erroneous if the incident beam is not perfectly collimated, leading to measured intensity distributions that differ in the distant "tails".

This study provided intensity data covering many diffraction orders and performed a thorough statistical comparison with theory. The heavy-tailed nature of ideal wire diffraction (power-law decay of band intensity) was confirmed, while simultaneously highlighting how a Gaussian incident beam leads to faster decay in the wings than the ideal behavior .

4.4.5. High Dynamic Range Measurements

To directly measure diffraction intensity in the range of 5-6 orders of magnitude, researchers have used high dynamic range detectors and multi-exposure methods. A striking example is the work of Shcherbakov et al. (2020) [

9], who measured the Fraunhofer diffraction pattern up to the 16th order of diffraction bands, using a specialized LiF photoluminescent detector.

In their experiment on a synchrotron line, an aperture 5 microns wide (approximation to a slit) was illuminated by soft X-rays, and the diffraction image was recorded with extremely high sensitivity. They achieved a limiting dynamic range of about in intensity. They were not only able to detect bands extremely far from the center, but also quantitatively determine the intensity decay: the dose in the central maximum was about (in arbitrary units), whereas by the 16th band it fell to , a difference of 7 orders of magnitude. The distance between bands and intensity statistics were analyzed, confirming the expected envelope even at these extreme angles.

4.4.6. Analysis of Intensity Distribution: Gaussian and Heavy-Tailed Models

Several studies explicitly compare the observed diffraction intensity profiles with various statistical distribution models (Gaussian and heavy-tailed). Typically, diffraction from an aperture with sharp edges creates intensity distributions with heavy tails, whereas an aperture with a Gaussian profile creates Gaussian decay with negligible side lobes. This was emphasized in Ganci’s experiment with a thin wire: with plane-wave illumination, the cross-sectional intensity profile follows a heavy-tailed pattern (formally having long tails ), whereas a Gaussian incident beam "softens" the edges and makes the wings closer to Gaussian decay.

Researchers have applied heavy-tailed probability distributions to model intensity values in diffraction patterns. For example, Alam (2025) [

10] analyzed sets of powder X-ray diffraction intensity data using distributions of the Cauchy family, demonstrating superior approximation for strong outliers in intensity. By considering intensity fluctuations as a heavy-tailed process, this work covered the statistical spread from the brightest Bragg peaks to the weak background, in a range of many orders of magnitude. The study showed that half-Cauchy or log-Cauchy distributions can model the intensity histogram much better than Gaussian, which would significantly underestimate the frequency of large deviations.

5. Conclusion

5.1. Summary of Main Results and Their Significance

This paper presents two fundamental principles with revolutionary potential for understanding light, space, and time:

1. Electromagnetic phenomena are two-dimensional and follow the Cauchy distribution law. 2. There exists a non-integer variable dimensionality of spaces.

These principles form the basis for a new approach to understanding physical reality. Spatial dimensionality D=2.0 represents a special critical point at which waves maintain coherence without geometric dispersion, the Green’s function undergoes a phase transition from power-law decay to logarithmic dependence, and the existence of mass becomes fundamentally impossible. These mathematical features exactly correspond to the observed properties of the electromagnetic field — masslessness, preservation of coherence over cosmological distances, and the universality of the Cauchy distribution in resonant phenomena.

The proposed "reverse slit experiment" will allow direct testing of the hypothesis about the light intensity distribution in the shadow of a thin object. If it is confirmed that this distribution follows the Cauchy law, and not the sinc² function (as predicted by standard diffraction theory), this will provide direct evidence for the special status of the Cauchy distribution for electromagnetic phenomena and, consequently, their two-dimensional nature.

The actual observation of a shape different from the Cauchy family, with high statistical significance and reliable exclusion of external noise, will uncover a huge tension in modern physics and pose the fundamental question: "Why in many independent experiments is the phenomenon of Lorentz invariance recorded with high reliability?" In this sense, even if reality gives a non-Cauchy form (which would seriously undermine the presented theory), the experiment remains win-win, as a negative result would be just as fundamentally useful for physics, exposing deep contradictions in the modern understanding of the nature of light and interactions.

5.2. Ultraviolet Catastrophe and the Origin of Quantum Theory

The historical "ultraviolet catastrophe," which became a crisis of classical physics at the end of the 19th century after experiments with black body radiation in Planck’s ovens, acquires a natural explanation within the proposed theory. The Cauchy distribution, characterizing two-dimensional electromagnetic phenomena, fundamentally does not have finite statistical moments of higher orders, which directly explains the divergence of energy at high frequencies.

Quantum physics in this concept is not a separate area with its unique laws, but naturally arises in spaces with dimensionality . When the effective dimensionality decreases below the critical boundary D=2.0, the statistical properties of distributions radically change, creating conditions for the emergence of quantum effects. These effects manifest as projections from lower-dimensional spaces () into the three-dimensional world of observation, which explains their apparent paradoxicality when described in terms of three-dimensional space.

5.3. Nature of Mass as a Dimensional Effect

The presented concept reveals a new understanding of the nature of mass. At the point D=2.0 (electromagnetic field), mass is fundamentally impossible due to the fundamental mathematical properties of two-dimensional spaces and the Cauchy distribution. When deviating from this critical dimensionality (both higher and lower), the possibility of massive states arises.

Mass in this interpretation appears not as a fundamental property of matter, but as a measure of informational misalignment between two-dimensional electromagnetic and non-two-dimensional material aspects of reality, normalized by the square of the speed of light. This explains the famous formula as an expression of the energy needed to synchronize a massive object with a two-dimensional electromagnetic field.

Such an approach to understanding mass allows explaining the observed spectrum of elementary particle masses without the need to postulate a Higgs mechanism, presenting mass as a natural consequence of the dimensional properties of the spaces in which various particles exist.

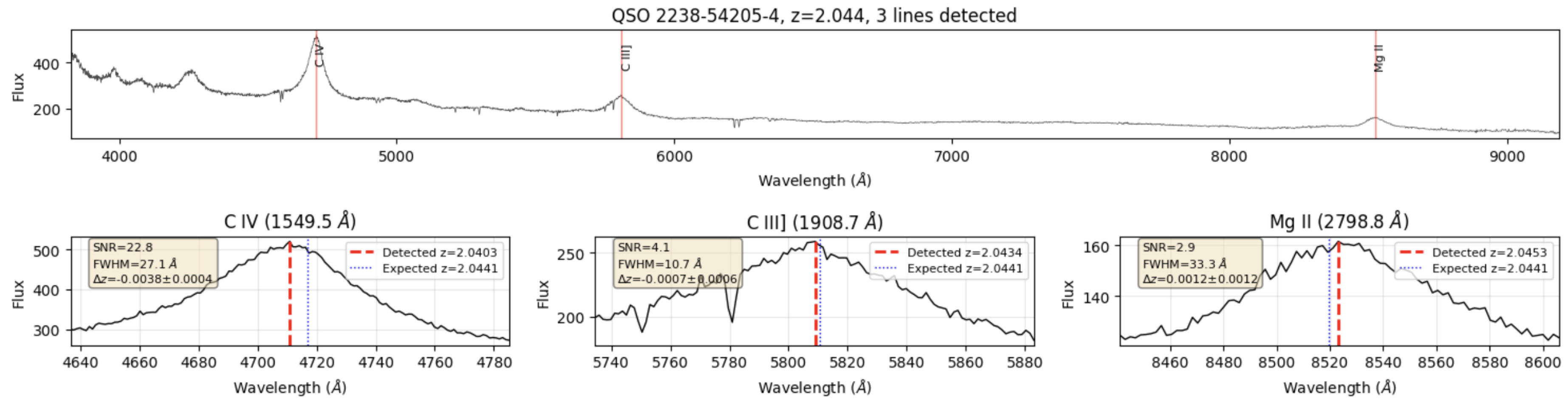

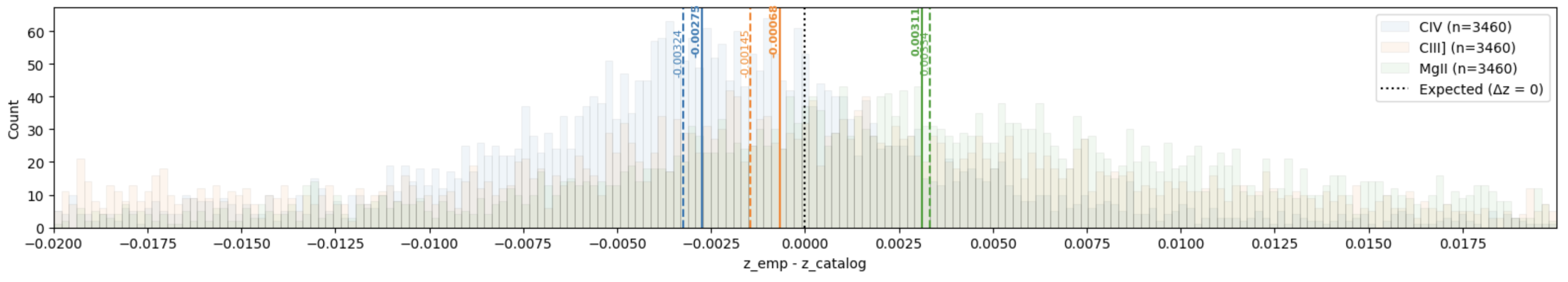

5.4. New Interpretation of Cosmological Redshift

One of the revolutionary implications of this theory concerns the interpretation of cosmological redshift. Instead of the expansion of the Universe, a fundamentally different explanation is proposed: redshift may be the result of light passing through regions with different effective dimensionality.

This interpretation represents a modern version of the "tired light" hypothesis, but with a specific physical mechanism for the attenuation of photon energy. When light (D=2.0) passes through regions with a different effective dimensionality, the energy of photons is attenuated in proportion to the dimensional difference, which is observed as redshift.

This explanation of redshift is consistent with the observed "redshift-distance" dependence, while completely eliminating the need for the hypothesis of an expanding Universe with an initial singularity. This approach removes fundamental conceptual problems related to the beginning and evolution of the Universe, proposing a model of a static Universe with dimensional gradients.

5.5. Hypothesis of Grand Unification at High Energies

The theory of variable dimensionality of spaces opens a new path to the Grand Unification of fundamental interactions. At high energies, according to this concept, the effective dimensionality of all interactions should tend to D=2.0 — a point at which electromagnetic interaction exists naturally.

This prediction means that at sufficiently high energies, all fundamental forces of nature should unite not through the introduction of additional symmetries or particles, but through the natural convergence of their effective dimensionalities to the critical point D=2.0. In this regime, all interactions should exhibit properties characteristic of light — masslessness, universality of interaction force, and optimal information transfer.

Such an approach to Grand Unification does not require exotic additional dimensions or supersymmetric particles, offering a more elegant solution based on a single principle of dimensional flow.

5.6. Historical Perspective and Paradigm Transformation

From a historical perspective, the proposed experiment can be viewed as a natural stage in the evolution of ideas about the nature of light:

1. Newton’s Corpuscular Theory (17-18th centuries) considered light as a flow of particles moving in straight lines.

2. Young and Fresnel’s Wave Theory (early 19th century) established the wave nature of light through the observation of interference and diffraction.

3. Maxwell’s Electromagnetic Theory (second half of 19th century) unified electricity, magnetism, and optics.

4. Planck and Einstein’s Quantum Theory of Light (early 20th century) introduced the concept of light as a flow of energy quanta — photons.

5. Quantum Electrodynamics by Dirac, Feynman, and others (mid-20th century) created a theory of light interaction with matter at the quantum level.

6. The Proposed Reverse Slit Experiment potentially establishes the fundamental dimensionality of electromagnetic phenomena and the Cauchy distribution as their inherent property.

It is interesting to note that many historical debates about the nature of light — wave or particle, local or non-local phenomenon — may find resolution in the dimensional approach, where these seeming contradictions are explained as different aspects of the same phenomenon, perceived through projection from space of a different dimensionality.

5.7. Call for Radical Rethinking of Our Concepts of the Nature of Light

The results of the proposed experiment, regardless of whether the Cauchy distribution or sinc² (default model) is confirmed, will require a radical rethinking of ideas about the nature of light:

1. If the Cauchy distribution is confirmed, this will be direct evidence of the special statistical character of electromagnetic phenomena, consistent with their masslessness and exact Lorentz invariance. This will require revision of many aspects of quantum mechanics, wave-particle duality, and, possibly, even the foundations of energy discreteness.

2. If the sinc² distribution is confirmed, a deep paradox will arise requiring explanation: how can massless phenomena have characteristics that contradict their massless nature. This will create a serious tension between experimentally verified Lorentz invariance and the observed spatial distribution of light.

In any case, it is necessary to overcome the conceptual inertia that makes us automatically assume the three-dimensionality of all physical phenomena. Perhaps different physical interactions have different effective dimensionality, and this is the key to their unification at a more fundamental level.

It is separately important to note that a practical experiment and viewing through the prism of such principles in any case tells something new about the essence of time. And also to acknowledge that there is a huge inertia and an unspoken ban on the study of the essence of time.

Scientific progress is achieved not only through the accumulation of facts, but also through bold conceptual breakthroughs that force us to rethink fundamental assumptions. The proposed experiment and the underlying theory of dimensional flow represent just such a potential breakthrough.

Author Contributions

The author is solely responsible for the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing, and all other aspects of this research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author has no formal affiliation with scientific or educational institutions. This work was conducted independently, without external funding or institutional support. I express my deep gratitude to Anna for her unwavering support, patience, and encouragement throughout the development of this research. I would like to express special appreciation to the memory of my grandfather, Vasily, a thermal dynamics physicist, who instilled in me an inexhaustible curiosity and taught me to ask fundamental questions about the nature of reality. His influence is directly reflected in my pursuit of new approaches to understanding the basic principles of the physical world.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1 Historical Perspective: From Lorentzes to Modernity

The history of the development of our ideas about the nature of light, space, and time contains surprising parallels and unexpected connections between ideas of different eras. This appendix presents a historical overview of key figures and concepts that have led to modern ideas about the dimensionality of space and the statistical nature of electromagnetic phenomena.

Appendix 1.1 Two Lorentzes: Different Paths to the Nature of Light

The history of light physics is marked by the contributions of two outstanding scientists with the same surname — Hendrik Lorentz and Ludwig Lorentz — whose works laid the foundation for modern electrodynamics and optics, but contained important elements that did not receive proper development in subsequent decades.

Appendix 1.1.3 Commonality and Differences in the Approaches of the Two Lorentzes

The works of both Lorentzes are united by a deep understanding of the need for a medium or structure for the propagation of electromagnetic waves, although they approached this issue from different angles. Hendrik insisted on the existence of ether as a physical medium, while Ludwig worked with mathematical models of discrete oscillators.

It is noteworthy that both scientists intuitively sought to describe the spatial structure in which electromagnetic field propagates, which can be seen as a harbinger of modern ideas about the specific dimensionality of electromagnetic phenomena.

Appendix 1.2 Augustin-Louis Cauchy (1789-1857): From Analysis of Infinitesimals to Distributions with "Heavy Tails"

Augustin-Louis Cauchy, an outstanding French mathematician, is known for his fundamental works in the field of mathematical analysis, theory of differential equations, and theory of complex functions. However, his contribution to the development of statistical theory and, indirectly, to understanding the nature of wave processes, is often underestimated.

Appendix 1.2.1 Discovery and Properties of the Cauchy Distribution

Cauchy discovered the distribution named after him while studying the limiting behavior of certain integrals. The Cauchy distribution, expressed by the formula:

has a number of unique properties:

It does not have finite statistical moments (no mean value, variance, and higher-order moments)

It is a stable distribution — the sum of independent random variables with Cauchy distribution also has a Cauchy distribution

It has "heavy tails" that decay as for large values of the argument

Cauchy considered this distribution as a mathematical anomaly contradicting intuitive ideas about probability distributions. He could not foresee that the distribution he discovered would become a key to understanding the nature of massless fields in 20th-21st century physics.

Appendix 1.2.2 Connection with Resonant Phenomena and Wave Processes

Already in the 19th century, it was established that the Cauchy distribution (also known as the Lorentz distribution in physics) describes the shape of resonant curves in oscillatory systems. However, the deep connection between this distribution and wave processes in spaces of different dimensionality was realized much later.

Appendix 1.4 Albert Einstein (1879-1955): Relativization of Time and Geometrization of Gravity

Albert Einstein’s contribution to the development of modern physics is difficult to overestimate. His revolutionary theories fundamentally changed our understanding of space, time, and gravity.

Appendix 1.4.1 Special Theory of Relativity: Time as the Fourth Dimension

In his famous 1905 paper "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies", Einstein took a revolutionary step, reconceptualizing the concept of time as a fourth dimension, equal to spatial coordinates. This reconceptualization led to the formation of the concept of four-dimensional space-time.

Einstein’s approach differed from Lorentz’s approach by rejecting the ether and postulating the fundamental nature of Lorentz transformations as a reflection of the properties of space-time, not the properties of material objects moving through the ether.

However, by accepting time as the fourth dimension, Einstein implicitly postulated a special role for dimensionality D=4 (three-dimensional space plus time) for all physical phenomena, which may not be entirely correct for electromagnetic phenomena if they indeed have fundamental dimensionality D=2.

Appendix 1.4.2 General Theory of Relativity: Geometrization of Gravity

In the general theory of relativity (1915-1916), Einstein took an even more radical step, interpreting gravity as a manifestation of the curvature of four-dimensional space-time. This led to the replacement of the concept of force with a geometric concept — geodesic lines in curved space-time.

Einstein’s geometric approach showed how physical phenomena can be reinterpreted through the geometric properties of space of special dimensionality and structure. This anticipated modern attempts to geometrize all fundamental interactions, including electromagnetism, through the concept of effective dimensionality.

Appendix 1.5 Hermann Minkowski (1864-1909): Space-Time and Light Cone

Hermann Minkowski, a German mathematician, former teacher of Einstein, created an elegant geometric formulation of the special theory of relativity, introducing the concept of a unified space-time — "world" (Welt).

Appendix 1.5.1 Minkowski Space and Invariant Interval

In his famous 1908 lecture "Space and Time," Minkowski presented a four-dimensional space with the metric:

where is the invariant interval between events.

This metric defines the structure of Minkowski space, in which Lorentz transformations represent rotations in four-dimensional space-time. Minkowski showed that all laws of the special theory of relativity can be elegantly expressed through this four-dimensional geometry.

Appendix 1.5.2 Light Cone and the Special Role of Light

Especially important was Minkowski’s concept of the light cone — a geometric structure defining the causal structure of space-time. An event on the light cone of some point corresponds to a ray of light passing through that point.

Minkowski was the first to clearly realize that light plays a special, fundamental role in the structure of space-time. He wrote: "The entity that we now call ’ether’ may in the future be perceived as special states in space."

This intuition of Minkowski about the fundamental connection between light and the geometric structure of space-time anticipates modern ideas about light as a phenomenon defining a specific structure of space.

Appendix 1.6 Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro (1853-1925): Tensor Analysis and Differential Geometry

Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro, an Italian mathematician, developed tensor calculus — a mathematical apparatus that became the basis of the general theory of relativity and modern differential geometry.

Appendix 1.6.1 Tensor Analysis and Absolute Differential Calculus

Ricci developed what he called "absolute differential calculus" — a systematic theory of tensors that allowed formulating physical laws in a form invariant with respect to arbitrary coordinate transformations.

This work, published jointly with his student Tullio Levi-Civita in 1900, laid the mathematical foundation for the subsequent development of the general theory of relativity and other geometric theories of physics.

Appendix 1.6.2 Spaces of Variable Curvature and Dimensionality

Ricci’s tensor analysis is naturally applicable to spaces of arbitrary dimensionality and curvature. This universality of the tool opened the way for the study of physical theories in spaces of various dimensionality and structure.

In the modern context, Ricci’s work can be considered as creating a mathematical apparatus allowing to correctly formulate physical laws in spaces of variable dimensionality, which is critically important for understanding the effective dimensionality of fundamental interactions.

Appendix 1.7 Dimensionality and Its Perception in the History of Physics

The history of the development of ideas about dimensionality in physics represents an amazing evolution from intuitive three-dimensional space to a multitude of spaces of variable dimensionality and structure.

Appendix 1.7.1 From Euclidean Three-Dimensional Space to n-Dimensional Manifolds

Euclidean geometry, based on Euclid’s axioms, silently assumed the three-dimensionality of physical space. This idea dominated science until the 19th century.

The development of non-Euclidean geometries (Lobachevsky, Bolyai, Riemann) in the 19th century opened the possibility of mathematical description of spaces with different curvature. In parallel, the concept of n-dimensional space was developed in the works of Grassmann, Cayley, and others.

These mathematical developments were initially perceived as abstract constructions having no direct relation to physical reality. However, they created the necessary conceptual and mathematical foundation for subsequent revolutions in physics.

Appendix 1.7.2 Dimensionality in Quantum Field Theory and String Theory

The development of quantum field theory in the mid-20th century led to the realization of the importance of dimensional analysis in physics. Concepts of critical dimensionality, dimensional regularization, and anomalous dimensionality emerged.

In the 1970-80s, string theory introduced the idea of microscopic dimensions compacted to Planck scales (compactification). According to this theory, our world may have 10, 11, or 26 dimensions, most of which are not observable due to their compactness.

These developments prepared the ground for the modern understanding of effective dimensionality as a dynamic parameter depending on the scale of observation and type of interaction.

Appendix 1.7.3 Fractal Dimensionality and Dimensional Flow

The concept of fractal (fractional) dimensionality, introduced by Benoit Mandelbrot in the 1970s, revolutionized our understanding of dimensionality, showing that it can be a non-integer number.

In recent decades, in some approaches to quantum gravity (causal dynamical triangulation, asymptotic safety), the concept of dimensional flow has emerged — the effective dimensionality of space-time may change with the scale of energy or distance.

These modern developments naturally lead to the hypothesis that different fundamental interactions may have different effective dimensionality, which in the case of electromagnetism may be exactly D=2.

Appendix 1.8 Unfinished Revolution: Missed Opportunities in the History of Physics

Looking back at the history of the development of ideas about light, space, and time, we can notice several critical moments where scientific thought could have gone in a different direction, perhaps more directly leading to the modern understanding of the two-dimensional nature of electromagnetic phenomena and the variable dimensionality of space.

Appendix 1.8.1 Lorentz’s Ether as Space of Specific Structure

Hendrik Lorentz never abandoned the concept of ether, even after acknowledging the special theory of relativity. His intuitive conviction in the necessity of a special medium for light propagation can be viewed as a premonition that electromagnetic phenomena require space of a special structure, different from ordinary three-dimensional space of matter.

If this intuition had been developed in the direction of studying the effective dimensionality of the "ether", perhaps the two-dimensional nature of electromagnetic phenomena would have been discovered much earlier.

Appendix 1.8.2 Poincaré’s Conventionalism and the Choice of Geometry

Poincaré’s philosophical conventionalism suggested that the choice of geometry for describing physical space is a matter of agreement, not an empirical discovery. This deep methodological principle could have led to a more flexible approach to the dimensionality of various physical phenomena.

However, historically, this philosophical position was not fully integrated into physical theories. Instead, after the works of Einstein and Minkowski, the four-dimensionality of space-time began to be perceived as physical reality, and not as a convenient convention for describing certain phenomena.

Appendix 1.8.3 The Lost Scale Factor in Lorentz Transformations

As noted by Verkhovsky [

11], in the original formulations of Lorentz transformations, there was an additional scale factor

, which was subsequently taken to be equal to one.

This mathematical "normalization", performed by Poincaré and Einstein, may have missed an important physical aspect of the transformations. If the scale factor had been preserved and interpreted through the prism of the Doppler effect and the two-dimensionality of electromagnetic phenomena, perhaps this would have led to a more complete theory, naturally including the Cauchy distribution as a fundamental statistical description of light.

Appendix 1.8.4 The Cauchy Distribution as a Physical, Not Just a Mathematical Phenomenon

Although the Cauchy distribution was known to mathematicians since the 19th century, its fundamental role in the physics of electromagnetic phenomena was not fully realized. The Cauchy distribution (or Lorentz distribution in physics) was used as a convenient approximation for describing resonant phenomena, but its connection with the masslessness of the photon and the two-dimensionality of electromagnetic phenomena was not established.

This omission led to the Gaussian distribution, more intuitively understandable and mathematically manageable, becoming a standard tool in physical models, even when it did not fully correspond to the massless nature of the studied phenomena.

Appendix 1.9 Conclusion: Historical Perspective of the Modern Hypothesis

Consideration of the historical context of the development of the physics of light and concepts of space-time shows that the hypothesis about the two-dimensionality of electromagnetic phenomena and their description through the Cauchy distribution has deep historical roots. It is not an arbitrary innovation, but rather a synthesis and logical development of ideas present in the works of outstanding physicists and mathematicians of the past.

In fact, many key elements of the modern hypothesis — the special role of light in the structure of space-time (Minkowski), the need for a specific medium for the propagation of electromagnetic waves (H. Lorentz), statistical description of resonant phenomena (Cauchy, L. Lorentz), the conventional nature of geometry (Poincaré), the possibility of geometrization of physical interactions (Einstein, Ricci) — were presented in one form or another in classical works.

The current hypothesis about the two-dimensional nature of electromagnetic phenomena and the non-integer variable dimensionality of spaces can be viewed as the restoration of a lost line of development of physical thought and the completion of an unfinished revolution started by the Lorentzes, Poincaré, Einstein, and other pioneers of modern physics.

Appendix 2 Thought Experiment: Life on a Jellyfish, on the Nature of Coordinates, Movement, and Time

In this thought experiment, we will consider the fundamental limitations of our perception of space, movement, and time, illustrating them through the metaphor of life on a jellyfish.

Appendix 2.1 Jellyfish vs. Earth: Qualitative Difference of Coordinate Systems

Imagine two fundamentally different worlds:

Appendix 2.1.1 Life on Earth

We are used to living on a beautiful, almost locally flat, solid earth. Our world is filled with many static landmarks on an almost flat surface. Earth has a ribbed relief, allowing us to easily distinguish any "here" from "there". Additionally, stable gravity creates a clear sense of "up" and "down", further fixing our coordinate system.

Appendix 2.1.2 Life on a Jellyfish

Now imagine that instead, you live on the back of a huge jellyfish, floating in the ocean. This reality is radically different:

The surface of the jellyfish is non-static and constantly fluctuates

The jellyfish moves by itself, and the movements are unpredictable and irregular

The surface of the jellyfish is homogeneous, without pronounced landmarks

"Gravity" constantly changes due to jellyfish movements

Under such conditions, building a stable coordinate system becomes fundamentally impossible.

Appendix 2.2 Impossibility of Determining Rest and Movement

In the jellyfish world, the concepts of rest and movement lose clear meaning:

When you walk on the surface of the jellyfish, it is impossible to determine whether you are actually advancing relative to absolute space or whether the jellyfish itself is moving in the opposite direction

Perhaps when you "scratch" the surface of the jellyfish with your feet, it reacts by moving like a treadmill in the opposite direction

Without external landmarks, it is impossible to distinguish your own movement from the movement of the jellyfish

This situation is analogous to our real position in space: we are on Earth, which rotates around its axis and around the Sun, the Solar System moves in the Galaxy, the Galaxy — in the Local Group, and so on. However, we do not directly sense these movements, but perceive only relative displacements and changes. And we have independent electromagnetic "beacons".

Appendix 2.3 Gravity as a Local Gradient, Not an Absolute Value

Continuing the analogy with the jellyfish:

The raising and lowering of the jellyfish’s back will be perceived by you as unpredictable jumps in "gravity"

These changes will slightly warm you, creating a feeling of being affected by some force

However, you will perceive only changes, gradients of this "force", not its absolute value

This analogy illustrates an important principle: in reality, physics does not measure absolute values, such as "mass according to the Paris standard" — this is a simplification for schoolchildren. Physicists measure only gradients, transitions, changes in values.

We do not feel the gravitational attraction of the black hole at the center of the Galaxy, although it is huge, because it acts on us uniformly. We sense only local gradients of the gravitational field.

Appendix 2.4 Impossibility of the Shortest Path with a Changing Landscape

On the surface of an oscillating jellyfish, the very concept of the "shortest path" loses meaning:

If the landscape is constantly changing, the geodesic line (shortest path) is also constantly changing

What was the shortest path a second ago may become a winding trajectory the next moment

Without a fixed coordinate system, it is impossible even to determine the direction of movement

This illustrates the fundamental problem of defining a "straight line" in a curved and dynamically changing space. General relativity faces a similar problem when defining geodesic lines in curved space-time.

Appendix 2.5 Role of External Landmarks for Creating a Theory of Movement

In the case of the jellyfish, without external beacons, theories of dynamics or movement from the 17-18th centuries would not emerge

If the entire surface of the jellyfish is visually homogeneous, and "here" is no different from "there", the coordinate system becomes arbitrary and unstable

Only the presence of external, "absolute" landmarks would allow creating a stable reference system

Similarly, in cosmology, distant galaxies and cosmic microwave background field serve as such external landmarks, allowing us to define an "absolute" reference frame for studying the large-scale structure of the Universe.

Appendix 2.6 Thought Experiment with Ship Cabins and Trains

Classical thought experiments with ship cabins and trains can be reconsidered in the context of the jellyfish:

Imagine a cabin of a ship sailing on the back of a jellyfish, which itself is swimming in the ocean

In this case, even the inertiality of movement becomes undefined: the cabin moves relative to the ship, the ship relative to the jellyfish, the jellyfish relative to the ocean

Experiments inside the cabin cannot determine not only the speed, but even the type and character of the movement of the system as a whole

This thought experiment illustrates a deeper level of relativity than the classical Galileo or Einstein experiment, adding non-inertiality and instability to space itself.

Appendix 2.7 Impossibility of a Conceptual Coordinate Grid

An attempt to create a conceptual grid of coordinates will face fundamental obstacles:

All your measuring instruments (rulers, protractors) will deform along with the surface of the jellyfish

If the gradient (difference) of deformations is weak, this will create minimal deviations, and the conceptual grid will be almost stable

If the gradient is large and nonlinear, the very geometry of space will bend, and differently in different places

Without external landmarks, it is impossible even to understand that your coordinate grid is distorting

This illustrates the fundamental problem of measuring the curvature of space-time "from within" that space-time itself. We can measure only relative curvatures, but not absolute "flatness" or "curvature".

Appendix 2.8 Time as a Consequence of Information Asymmetry

The deepest aspect of life on a jellyfish is the rethinking of the nature of time:

In conditions of a constantly changing surface, when it is impossible to distinguish "here" from "there", the only structuring principle becomes information asymmetry

What we perceive as "time" is nothing more than a measure of information asymmetry between what we already know (past) and what we do not yet know (future)

If the jellyfish completely stopped moving, and all processes on its surface stopped, "time" as we understand it would cease to exist

This thought experiment proposes to rethink time not as a fundamental dimension, but as an emergent property arising from information asymmetry and unpredictability.

Appendix 2.9 Connection with the Main Principles of the Work

This thought experiment is directly related to the fundamental principles presented in this paper:

1. Two-dimensionality of electromagnetic phenomena: Just as a jellyfish inhabitant is deprived of the ability to directly perceive the three-dimensionality of their world, so we cannot directly perceive the two-dimensionality of electromagnetic phenomena projected into our three-dimensional world.

2. Non-integer variable dimensionality of spaces: The oscillations and deformations of the jellyfish’s surface create an effective dimensionality that can locally change and take non-integer values, similar to how the effective dimensionality of physical interactions can change depending on the scale and nature of the interaction.

Life on a jellyfish is a metaphor for our position in the Universe: we inhabit a space whose properties we can measure only relatively, through impacts and changes. Absolute coordinates, absolute rest, absolute time do not exist — these are all constructs of our mind, created to structure experience in a world of fundamental uncertainty and variable dimensionality.

Appendix 3 Thought Experiment: A Walk to a Tree and Flight to the Far Side of the Moon, on the Nature of Observation

This thought experiment allows us to clearly demonstrate the nature of observation through the projection of a three-dimensional world onto a two-dimensional surface, which is directly related to the hypothesis about the two-dimensional nature of electromagnetic phenomena discussed in the main text of the article.

Appendix 3.1 Observation and the Projective Nature of Perception

Imagine the following situation: you are in a deserted park early in the morning when there is no wind, and in the distance, you see a lone standing tree. This perception has a strictly projective nature:

Light reflects from the tree and falls on the retina of your eyes, which is a two-dimensional surface.

Each eye receives a flat, two-dimensional image, which is then transmitted to the brain through electrical impulses.

At such a distance, the images from the two eyes are practically indistinguishable from each other.

At this moment, you cannot say with certainty what exactly you are seeing — a real three-dimensional tree or an artfully made flat picture of a tree, fortunately placed perpendicular to your line of sight. You lean towards the conclusion that it is a real tree, based only on your previous experience: you have seen many real trees and rarely encountered realistic flat images installed in parks.

Appendix 3.2 Movement and Information Disclosure

You decide to approach the tree. As you move, the following happens:

The image of the tree on the retina gradually increases.

Parallax appears — slight differences between the images from the left and right eyes become more noticeable.

The brain begins to interpret these differences, creating a sense of depth and three-dimensionality.

This does not happen immediately, but gradually, as you move.

You still see only one side of the tree — the one facing you. The back side of the tree remains invisible, hidden behind the trunk and crown. Your three-dimensional perception is partially formed from two slightly different two-dimensional projections, and partially constructed by the brain based on experience and expectations.

Appendix 3.3 Completeness of Perception and Fundamental Limitation