1. Introduction

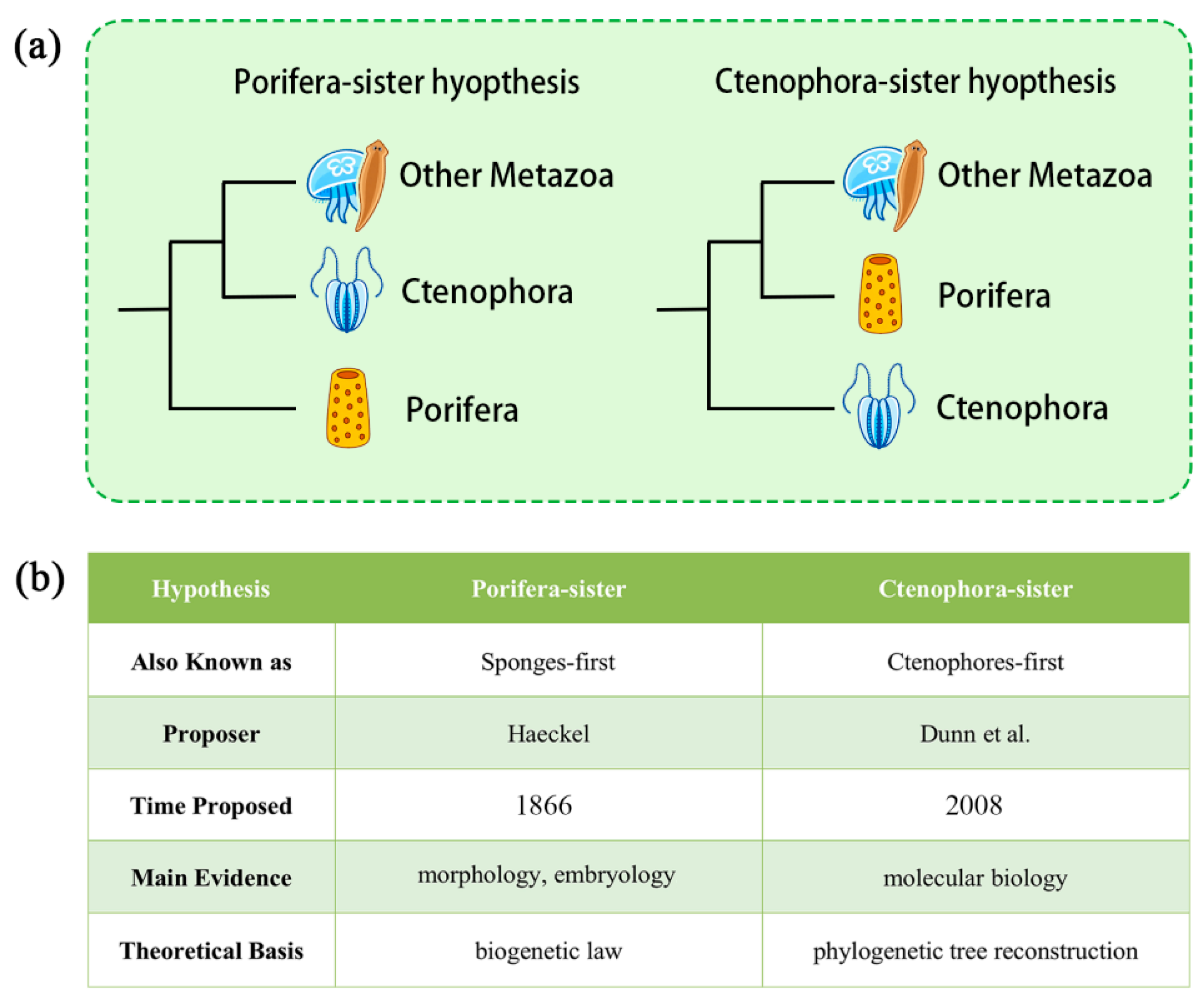

The Porifera-sister Hypothesis (or Sponge-first Hypothesis) posits that sponges represent the sister group to all other metazoans. Its origin can be traced back to 1866, when Haeckel, drawing on his “biogenetic law” and evidence primarily from embryology and morphology (with the known fossil record posing no contradiction), first articulated this view (

Figure 1) [

1,

2]. However, with the continual accumulation of multidisciplinary evidence—from molecular biology to morphology enhanced by new technologies—this traditional perspective has been increasingly questioned and challenged. In contrast, the Ctenophora-sister Hypothesis (or Ctenophore-first Hypothesis), first proposed by Dunn et al. [

3] based on molecular phylogenomic analyses in 2008, argues that ctenophores, rather than sponges, are the sister group to all other animals (

Figure 1). These two competing hypotheses now define the central debate surrounding the root of the animal phylogenetic tree.

The importance of resolving this question extends far beyond simply clarifying the topology of the basal animal tree. On one hand, because the earliest-branching lineages likely involve extensive instances of independent origins, convergence, and secondary loss—phenomena that have historically been misunderstood (see

Section 4 including

Figure 2b) [

4,

5]—addressing this problem may offer a more nuanced understanding of the broader dynamics of biological evolution, beyond conventional linear interpretations. On the other hand, given the pervasive and often conflicting signals in phylogenetic analyses, particularly those derived from molecular data (see

Section 2 including

Table A1) [

6,

7,

8,

9], resolving this debate will also substantially enhance our ability to reconstruct evolutionary history with greater accuracy.

However, resolving this issue is far from straightforward. As Krumbach famously remarked, “Although it is easy in a given case to determine whether or not a particular animal is a ctenophore, it is equally difficult to establish how closely or distantly ctenophores are related to other forms of animals [

10].” As will be shown in the sections that follow, despite substantial progress across individual disciplines, the conclusions they yield are often in conflict with one another.

Nevertheless, encouragingly, discussions surrounding this issue have become increasingly active in recent years. However, many of these studies are still largely discipline-specific or only touch upon other data types in a limited way, underscoring the need for deeper integrative synthesis. Hence, there is a pressing need for an interdisciplinary synthesis that unifies existing findings across diverse fields.

This review begins by examining key lines of evidence from molecular biology, embryology, morphology, and paleontology, and then brings them into dialogue to revisit the long-standing debate over the root of the animal tree. Rather than proposing a formal solution, it aims to highlight conceptual patterns and unresolved tensions across disciplines, with the hope of informing future perspectives on deep-time phylogenetic inference.

2. Molecular Sequence Evidence

This section primarily discusses the phylogenetic signals provided by tree-building approaches based on RNA, DNA, or protein sequences in molecular biology.

The earliest study in this area was conducted by Cavalier-Smith et al., who used 18S rRNA sequences from 453 eukaryotic species—over 100 of which were animals—to reconstruct phylogenetic trees. Their analysis placed sponges at the base of the animal tree, providing the first molecular support for the Porifera-sister hypothesis [

11]. However, due to the limited phylogenetic signal in 18S rRNA and the generally low support values at deep nodes, the reliability of this result was relatively low.

A more comprehensive study was conducted by Dunn et al., who used expressed sequence tag (EST) data—random cDNA fragments derived from transcriptomes—from 29 species representing 21 animal phyla [

3]. This was the first study to propose the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis, placing ctenophores as the sister group to all other animals. Later, Ryan et al. sequenced the full genome of the ctenophore

Mnemiopsis leidyi and conducted further phylogenetic analyses, which reinforced this hypothesis [

12]. These two studies together ignited widespread interest in the debate over the root of the animal tree.

Currently, the controversy surrounding molecular sequence data primarily focuses on how to manage methodological artifacts, especially those stemming from modeling and biological errors.

2.1. Methodological Errors: Long-Branch Attraction (LBA)

This section deals with errors caused by the phylogenetic models themselves, particularly long-branch attraction (LBA)—arguably the most extensively discussed source of bias in this context. In LBA, rapidly evolving (long-branched) taxa may be erroneously grouped together [

13]. In this context, LBA is usually attributed to heterogeneity and outgroup selection.

2.1.1. Heterogeneity-Induced LBA

Heterogeneity can be broadly categorized into two types: compositional heterogeneity among lineages and substitutional heterogeneity across sites.

Compositional heterogeneity arises from differences in base or amino acid usage across species, influenced by factors such as GC/AT bias or amino acid biosynthetic cost [

14,

15,

16]. This can lead to convergent composition between distantly related taxa, potentially resulting in false groupings [

14,

15,

17,

18].

Substitutional heterogeneity refers to variation in substitution rates and patterns (i.e., the probabilities of substitution between amino acids are not uniform) across sites [

19,

20,

21]. Such heterogeneity can lead to saturation at rapidly evolving sites, causing the retained signal to reflect amino acid preferences rather than true phylogenetic relationships, and thereby introducing systematic errors due to convergent substitutions, also contributing to LBA [

18,

19,

21].

To mitigate these effects, researchers have developed two major strategies: increasing model complexity and reducing data complexity.

2.1.1.1. Complexity-Based Approaches

These approaches involve the use of site-heterogeneous models (such as the CAT model [

21]), which allow different sites in a sequence alignment to evolve under their own substitution processes. By accounting for variation in substitutional preferences across sites (with the number of distinct substitution types represented as the number of categories), these models tend to be more resistant to long-branch attraction (LBA) artifacts [

22]. In contrast, studies using simpler site-homogeneous models often support the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis [

6,

12], whereas analyses based on CAT models typically support the Porifera-sister hypothesis [

7,

22,

23], but see [

3,

6]. Early assessments also suggested that the CAT model provided a better fit to the data [

6,

7]. As a result, initial skepticism toward the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis was largely attributed to LBA artifacts caused by site-specific substitutional preferences.

However, Li et al. pointed out that when the CAT model defaults to automatically determine the number of categories, it often selects an excessively high number, which leads to overfitting. Their cross-validation analyses showed that CAT models with excessive complexity did not outperform simpler site-heterogeneous models such as C60 on independent datasets. Moreover, they observed that as model complexity increased, the inferred root of the animal tree shifted—from supporting Ctenophora-sister, to an unresolved topology, and eventually to supporting Porifera-sister. This trend suggests that the Porifera-sister result, which only arises under conditions of very high category numbers and closely related outgroups, may in fact be an artifact caused by model overfitting [

8].

2.1.1.2. Simplification-Based Approaches

In related studies, a primary approach to data simplification is amino acid recoding, which involves grouping amino acids that are prone to mutual substitution during evolution into categories, such that only substitutions between these groups are considered.

This method offers dual advantages in addressing compositional heterogeneity and substitutional preference heterogeneity. On one hand, each group includes multiple amino acid types, thereby reducing the impact of lineage-specific compositional biases arising from species’ preferences for certain amino acids. On the other hand, recoding significantly reduces the number of effective states and the total number of substitution events included in the analysis, and diminishes variation among substitution models, which helps to mitigate site-specific heterogeneity. These are stated in [

24,

25], without detailed reasoning.

The application of this method can help counteract long-branch attraction effects and often leads to phylogenetic results supporting the Porifera-sister hypothesis [

22,

23].

Nevertheless, recoding also reduces the overall information content of the data, which can introduce its own biases [

22,

26]. Li et al. demonstrated that both empirical and randomized recoding schemes caused similar shifts toward Porifera-sister, likely as a result of information loss [

8]. Whelan et al. further observed that recoding sometimes led to implausible topologies in other regions of the tree [

26]. Similarly, Shen et al. found in studies of other clades that certain nodes were supported by minimal data, and even small changes could significantly alter the tree’s topology—though this effect was less pronounced in the animal root debate [

27]. These findings collectively suggest that the bias toward Porifera-sister observed in recoded datasets may primarily reflect a loss of phylogenetic signal, effectively introducing additional noise.

Notably, a recent study by Steenwyk et al., which supported the Porifera-sister hypothesis, may also be affected by these limitations. The authors used amino acid recoding and included only a small subset of genes that showed consistent signal under both concatenation and consensus approaches (mean = 4.63% ± 3.84%). Although they tested different threshold levels, the overall number of retained genes remained low. It is not yet clear whether similar results would be observed under randomized sampling schemes [

28]. This highlights the trade-off between signal clarity and completeness that warrants further scrutiny. However, this remains speculative and requires further empirical investigation.

In conclusion, while sequence heterogeneity remains a major concern, its role in driving long-branch attraction may not be as critical as previously thought. Its overall impact on resolving the root of the animal tree appears limited.

2.1.2. Outgroup-Induced LBA

To determine the root of the animal phylogenetic tree, researchers typically rely on outgroups that are manually chosen from lineages outside the ingroup. However, when the chosen outgroup is too distantly related, LBA or even random rooting can occur [

29,

30]. These distal outgroups often form long branches themselves, which exacerbates the LBA effect.

Research has shown that when using CAT models, selecting closely related outgroups tends to support the Porifera-sister hypothesis, while more distal outgroups favor the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis [

7]. Additionally, removing highly conserved proteins such as ribosomal genes—whose exclusion is known to exacerbate LBA—also tends to bias results toward the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis [

6,

7]. These findings underscore the influence of outgroup choice and LBA-related artifacts on inferred tree topology.

Although simpler models appear less sensitive to outgroup choice [

6,

8], and although CAT models may be prone to overfitting [

8], the overarching trend remains clear: strategies that mitigate LBA typically lead to Porifera-sister, whereas those that exacerbate it tend to support Ctenophora-sister. This consistent pattern suggests that LBA may indeed be a significant factor contributing to support for the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis.

2.2. Biological Errors: Tree Incongruence and Gene Loss

This section focuses on errors introduced by biological processes, especially the incongruence between actual gene trees and species trees, which arise from complex evolutionary events rather than methodological artifacts. Such sources of error can be broadly categorized as either “observed” or “unobserved”.

2.2.1. “Observed” Factors: Observable Signals Within the Dataset

“Observed” factors refer to signals directly observable within the dataset that can lead to conflicts between gene trees and species trees. A key source of such incongruence is incomplete lineage sorting (ILS). It refers to the random retention of ancestral alleles in different descendant species, which can lead to distantly related species sharing the same allele and being mistakenly inferred as closely related [

9,

31,

32,

33]. Additional contributors to tree incongruence include introgression (i.e., partial mixing of gene pools caused by interbreeding between closely related species) and horizontal gene transfer (HGT, e.g., cross-species gene transfer mediated by viruses) [

9,

31,

33,

34]. Gene introgression and HGT are collectively referred to as reticulate evolution [

35].

Although often overlooked in earlier studies, this issue has recently gained attention. Rosenzweig et al., using machine learning approaches, identified widespread incongruence between gene trees and species trees across multiple animal clades—most likely due to ILS. Notably, they found that such incongruence was less pronounced under the Porifera-sister hypothesis than under the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis, suggesting that the former may better reflect the underlying patterns of gene evolution [

9]. This suggests the issue may have been underestimated, but given the early stage of research, definitive conclusions are still difficult to draw.

2.2.2. “Unobserved” Factors: Hidden Biases Beyond the Dataset

“Unobserved” factors refer to missing information—especially gene loss—that can subtly distort phylogenetic inference. Like missing data, gene loss can affect estimates of evolutionary rates, leading to artificially long branches and reduced power to detect substitutional saturation, which in turn may induce LBA artifacts [

36]. More critically, because it is often difficult to distinguish whether a gene was ancestrally absent or lost secondarily, taxa with extensive gene loss may be mistakenly placed near the root of the tree.

Pisani et al. highlighted the disruptive impact of extensive gene loss on this phylogenetic question—most notably through a reanalysis showing that correcting the Bayesian model used in Ryan et al. reversed their original support for the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis, instead favoring Porifera-sister [

7,

12]. This case clearly demonstrates that gene loss can indeed affect tree topology. Similarly, Fernández et al. reported high levels of gene loss in ambiguous groups like cnidarians, which had lost 44% of orthologs relative to placozoans—underscoring the widespread and severe nature of gene loss across lineages [

37]. Together, these results suggest that gene loss is a major, yet often overlooked, source of phylogenetic error.

Despite its potential impact, gene loss remains understudied—not only because of the prevailing focus on LBA, but also because some models (e.g., site-heterogeneous substitution schemes and amino acid recoding) are often assumed to partially mitigate LBA caused by gene loss. Further, Bayesian methods—which attempt to infer the presence or absence of ancestral genes by integrating prior assumptions with observed patterns—are commonly employed to improve phylogenetic inference [

38]. However, as shown by the reassessment in Pisani et al. [

7], current applications of Bayesian methods may overestimate their ability to correct for gene loss. Given the possibility of extensive and systematic gene loss, however, these approaches may fail to account for its full impact—a possibility that has not been systematically assessed through empirical validation.

Ultimately, although early molecular sequence studies favored the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis, growing recognition of methodological biases—once corrected—has led to a consistent shift in support toward the Porifera-sister hypothesis, at least for now, while proponents of the Ctenophora-sister remain committed to addressing these critiques (

Table A1). This ongoing methodological contention has made it temporarily difficult to obtain robust and convergent phylogenetic signals.

3. Rare Molecular Event Evidence

While this section draws upon molecular biology, it differs from traditional molecular sequence-based evidence by focusing on rare molecular events—events that are valuable not through tree-based inference, but intrinsically informative due to their low likelihood of convergence and high degree of irreversibility, or at least one of these characteristics. This discussion centers around fusion-with-mixing (FWM) in nuclear genomes and the transfer of mitochondrial genes to the nucleus.

3.1. Fusion-with-Mixing in Nuclear Genomes: Anti-Convergent and Irreversible

Macrosynteny refers to the conserved chromosomal linkage of genes regardless of their precise order [

39]. One key form of rare genomic change is FWM, where two distinct chromosomal segments (ancestral linkage groups, or ALGs) undergo interchromosomal translocation (fusion), and the genes from both sources become fully interspersed through subsequent intrachromosomal rearrangements. This event is considered to have low convergence potential and high irreversibility (see

Section 6.2.2) [

40]. If we trace orthologous gene linkage groups across species and detect such mixing, it signals a fusion-with-mixing event.

In a study by Schultz et al., macrosynteny was compared across three closely related unicellular organisms, two ctenophores, two sponges, one placozoan, and two bilaterians. The analysis revealed that ctenophores share more similar macrosynteny patterns with unicellular relatives, while all other metazoans (excluding ctenophores) exhibit four shared, derived fusion-with-mixing events. Schultz et al. argue that, unless ctenophores are sister to all other metazoans, one would have to accept one of two highly improbable alternatives: multiple highly similar fusion-with-mixing events occurred independently in multiple lineages, or multiple precise reversals occurred in ctenophores, separating previously mixed ALGs [

41]. From a theoretical standpoint, both scenarios are extremely unlikely [

40].

Even so, alternative mechanisms—though highly improbable—could, in theory, lead to convergence or reversion in synteny. Reticulate evolution, including introgression and HGT, may reintroduce ancestral chromosomal segments or independently transfer similar gene clusters, mimicking fusion or reversal patterns. These processes complicate interpretation of rare genomic changes, particularly when few loci are involved.

In Schultz et al.’s study, each linkage group included between 5–29 genes, totaling 291 genes (compared to 2,474 conserved genes in the outgroup-metazoan set) [

41]. For context, introgression from Neanderthals into modern humans involves ~1–4% of the genome (~400–1000 genes) [

42], and Caenorhabditis elegans may have acquired 72–139 genes through HGT [

43]. This suggests that, in terms of scale, reticulate evolution could plausibly affect results—but only through a series of highly specific, low-probability events targeting the same regions.

Furthermore, whether ILS could affect synteny patterns remains unclear and requires further investigation. This, too, could lead to inconsistent signals [

44].

However, no empirical evidence has yet falsified the fusion-with-mixing method directly; critiques remain hypothetical. Given that even when such events are considered, the likelihood of convergence or reversal remains low, the method still exhibits low convergence probability and high irreversibility. Consequently, Schultz et al.'s conclusions are still highly robust and compelling.

3.2. Transfer of Mitochondrial Genes to the Nucleus: Irreversible but Lacking Anti-Convergence

A widespread phenomenon in evolution is the transfer of mitochondrial genes to the nucleus [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. Pett et al. were the first to sequence the mitochondrial genome of the ctenophore

Mnemiopsis leidyi and showed that the atp9 gene had been transferred to the nuclear genome. In contrast, atp9 remains mitochondrial in fungi, choanoflagellates (unicellular relatives of animals), and most sponges. However, in other metazoans, the gene has been transferred, and notably, the presequence in the nuclear-encoded version of atp9 contains the same motif as in the ctenophore version. This suggests a single shared transfer event, implying that ctenophores diverged after sponges [

51].

Experimental evidence in yeast has demonstrated that the reversal of this process is extremely unlikely [

52]. Furthermore, although reversals have been documented in plants [

53,

54,

55,

56], no such phenomenon has been observed in animals, which further supports its strong irreversibility.

However, given the short length of the sequences involved, the likelihood of convergent evolution remains high. Moreover, it's known that mitochondrial genes, once transferred to the nucleus, initially undergo relaxed selection, leading to a temporary acceleration in evolutionary rate [

57], which could facilitate convergence.

In summary, while mitochondrial gene transfer exhibits strong irreversibility, the high likelihood of convergence significantly challenges the robustness of the phylogenetic inferences drawn by Pett et al.

Taken together, rare events that combine low convergence potential and high irreversibility have demonstrated strong robustness and considerable promise for phylogenetic inference. As shown, for instance, by mitochondrial gene transfers, the absence of either feature can markedly undermine the reliability of phylogenetic conclusions—an issue that will be further addressed in the Discussion section. While mitochondrial gene transfer offers limited phylogenetic utility due to its susceptibility to convergence, FWM, by contrast, provides a coherent and arguably the most persuasive line of evidence supporting the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis.

4. Morphological and Embryological Evidence

Morphological and embryological features of sponges have long been considered among the earliest and most fundamental evidence in reconstructing animal evolutionary history. Traditionally viewed as “primitive”, these traits have underpinned the Porifera-sister hypothesis. Any alternative must therefore not only present new data, but also explain why such long-standing signals once pointed to sponges as the earliest-branching lineage.

Notably, recent research appears to be offering at least partial explanations for this discrepancy, first by challenging the logic that underpinned earlier interpretations, and then by questioning the evidentiary strength of the morphological and embryological traits themselves.

4.1. Impact of Evolutionary Models on Criteria for Structural Complexity

Traditionally, biological evolution was thought to follow a unidirectional path in which “advanced” species inherited simple structures from “primitive” ancestors and gradually increased their complexity. Based on this view, evolutionary relationships could be inferred by comparing structural complexity among species. However, the clarification of independent evolution and secondary loss as valid evolutionary mechanisms has severely challenged this assumption.

4.1.1. Nervous Systems and Choanocytes: Independent Origins Disrupt Complexity-Based Inference

One key premise of the complexity-based approach is that morphological traits must be inherited from a common ancestor, in other words, must have originated only once. If a trait instead evolved multiple times independently, this criterion becomes invalid.

Traditionally, the absence of a nervous system in sponges and the presence of a nerve net in ctenophores led to the view that sponges diverged earlier than ctenophores. However, recent findings indicate that the subepithelial nerve net in ctenophores is in fact a syncytial nerve net (SNN)—fundamentally distinct from all other known animal nervous systems (note: only the subepithelial portion is syncytial, not the entire nervous system) [

58]. This follows earlier discoveries showing that the gene repertoire underlying the ctenophore nervous system significantly differs from that of other animals [

12,

59]. Thus, the nervous system of ctenophores is likely to have evolved independently [

5,

60,

61], undermining the use of nervous system complexity as a proxy for phylogenetic order between these groups.

Similarly, the resemblance between choanoflagellates and sponge choanocytes led to the view that sponges evolved directly from choanoflagellate-like ancestors [

62]. Although molecular phylogenies do support choanoflagellates and metazoans as sister groups [

63], the evolutionary significance of this relationship has likely been overstated. Choanocyte-like cells have since been discovered in other animal groups [

64,

65], and detailed analyses reveal significant differences in morphology, function, and development between choanocytes and choanoflagellates [

66]. These findings suggest that choanocytes may have evolved multiple times independently as convergent adaptations for efficient filter feeding [

5,

66], weakening their value as evidence for a direct sponge–choanoflagellate evolutionary link.

Moreover, striated muscle fibers have independently evolved in medusozoan cnidarians (still as epitheliomuscular cells), in ctenophores of the order Cydippida (as true muscle cells), and in bilaterians. This convergence has been identified through histological characteristics, germ layer origins, and molecular markers [

67,

68]. While recognizing these independent origins does little to directly revise traditional morphological phylogenies, it further underscores how common convergent evolution and independent trait emergence are among early-diverging animal lineages.

4.1.2. Germ Layers, Body Axes, and Symmetry: Secondary Loss Obscures Evolutionary History

Another implicit assumption of the complexity-based method is that evolutionary processes always increase structural complexity. Therefore, if a more recently diverged lineage secondarily loses complex features, the method fails.

For instance, sponges are traditionally considered “primitive” for lacking differentiated germ layers, while later-evolving animals were thought to have acquired a gastrula stage and diploblastic body plans. However, Dunn et al. point out that it remains controversial whether sponges ever had a gastrula stage [

69], but see [

70], and that sponges may have descended from ancestors that did have such a stage but lost it secondarily [

4]. If true, then germ layer characteristics do not reliably indicate phylogenetic relationships—though this remains highly debated.

Similarly, sponges’ apparent lack of symmetry and body axes has been interpreted as “primitive”. Yet, they possess Wnt and other signaling components—key regulators of body axis formation in other animals [

69]. This opens the possibility that sponges secondarily lost body axes. Manuel further suggests that, based on rRNA phylogenies, the last common ancestor of Metazoa may have had cylindrical symmetry, and that sponges secondarily lost this feature, while other lineages evolved new forms of symmetry independently [

71]. Thus, symmetry and body axis organization in sponges likely do not reflect their basal phylogenetic position.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the evolutionary significance of traits in sponges and ctenophores must be re-evaluated. Regardless of the outcome, such reassessment challenges the traditional use of morphological and embryological evidence and may prompt a broader rethinking of evolutionary narratives across all life forms—highlighting the non-linear and non-staged nature of evolution.

4.2. Reassessment of Evidence and Its Implications for Morphological Complexity

Sponges have long been considered “primitive” due to their perceived low degree of tissue differentiation and apparent lack of certain physiological functions. However, accumulating evidence in recent years has challenged this traditional view.

4.2.1. Epithelial Tissue: Structural Complexity

It was once believed that sponge tissues lacked true epithelial features such as adherens and sealing junctions and a basement membrane [

72]. However, various types of adherens and sealing junctions have now been identified in sponges [

73,

74,

75,

76] and at least homoscleromorph sponges have been shown to possess a true basement membrane [

72].

From a genetic perspective, sponges possess a substantial set of core genes associated with epithelial function. Notably, even within cnidarians—traditionally considered to possess true epithelia—there are instances of at least one core epithelial gene being absent [

76], suggesting that sponges may already fulfill the minimal genetic requirements for forming epithelial tissues. Phylogenetically, both the organizational mechanisms of epithelia and several epithelial-associated genes may have emerged prior to the origin of Metazoa [

76,

77,

78]. With epithelial mechanisms already in place, it is hardly surprising that sponges developed true epithelia.

Collectively, these findings support the notion that at least homoscleromorph sponges possess true epithelia, whereas the epithelial status of other sponge classes remains nominally contentious—for the definition of “epithelium” rather than its functional attributes.

4.2.2. Neuron-like and Muscle-like Functions: Physiological Complexity

Sponges are not as physiologically simple as once believed. For instance, they are capable of transmitting action potentials (APs) across epithelial layers, albeit at extremely slow speeds [

79,

80]. In addition, they can integrate information and modulate behavior through various chemical messengers such as nitric oxide (NO) and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [

81,

82]. Sensory structures have also been identified, including non-motile cilia near the osculum that act as flow sensors, and pigmented ring structures in the posterior region of larvae that function as blue light photoreceptors [

83,

84,

85,

86]. Furthermore, reflex-like behaviors have been demonstrated—for example, peristaltic-like actions that expel waste from the aquiferous system in response to mechanical stimulation [

87]. Collectively, these findings indicate that sponges possess neuron-like functions.

Sponge contractility is also more widespread than previously assumed to be limited to porocytes. Localized or whole-body periodic contractions [

81,

82,

88], as well as peristaltic-like expulsive behaviors [

87], have been documented and are regulated by the aforementioned neuron-like systems [

81,

82,

87]. These observations suggest that sponges also exhibit muscle-like functions.

Taken together, the structural complexity of sponge epithelia, along with their neuron-like and muscle-like features, suggests that sponge tissues have been significantly underestimated in both functional and anatomical terms. Under both hypotheses, in most cases, sponges are placed as basal to both Placozoa and Cnidaria [

4,

89], but see [

90], making structural comparisons particularly relevant. Specifically, the positions of sponge neuro-like structures closely match those of neurosecretory cells in placozoans and the nerve net in cnidarians, while the location and degree of differentiation of sponge contractile structures show striking similarities to the fiber cells in placozoans and the epitheliomuscular cells in cnidarians [

91]. These patterns suggest that the structural and functional parallels between sponges and these two phyla may have been underestimated—potentially leading to an undervaluation of the evolutionary role and phylogenetic position of sponges.

It is worth noting, however, that the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis still fails to adequately explain the evolutionary history of certain traits. For instance, if this hypothesis holds true, we must accept that a digestive cavity associated with extracellular digestion appeared very early and was subsequently lost in sponges, or alternatively evolved independently at least twice—once in ctenophores and again in the remaining non-poriferan animals. This would imply a highly convoluted evolutionary scenario [

61]. In fact, ctenophores have even been confirmed to possess a complete digestive tract [

92], which further highlights this issue. Resolving this issue may require comparative analyses of digestive enzymes to determine their homology [

61]. Ironically, however, the phylogenetic tree resulting from the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis already entails multiple independent origins and losses of key traits. From that perspective, one more instance of independent evolution or loss would not significantly increase the overall complexity—making it, paradoxically, a strangely acceptable outcome.

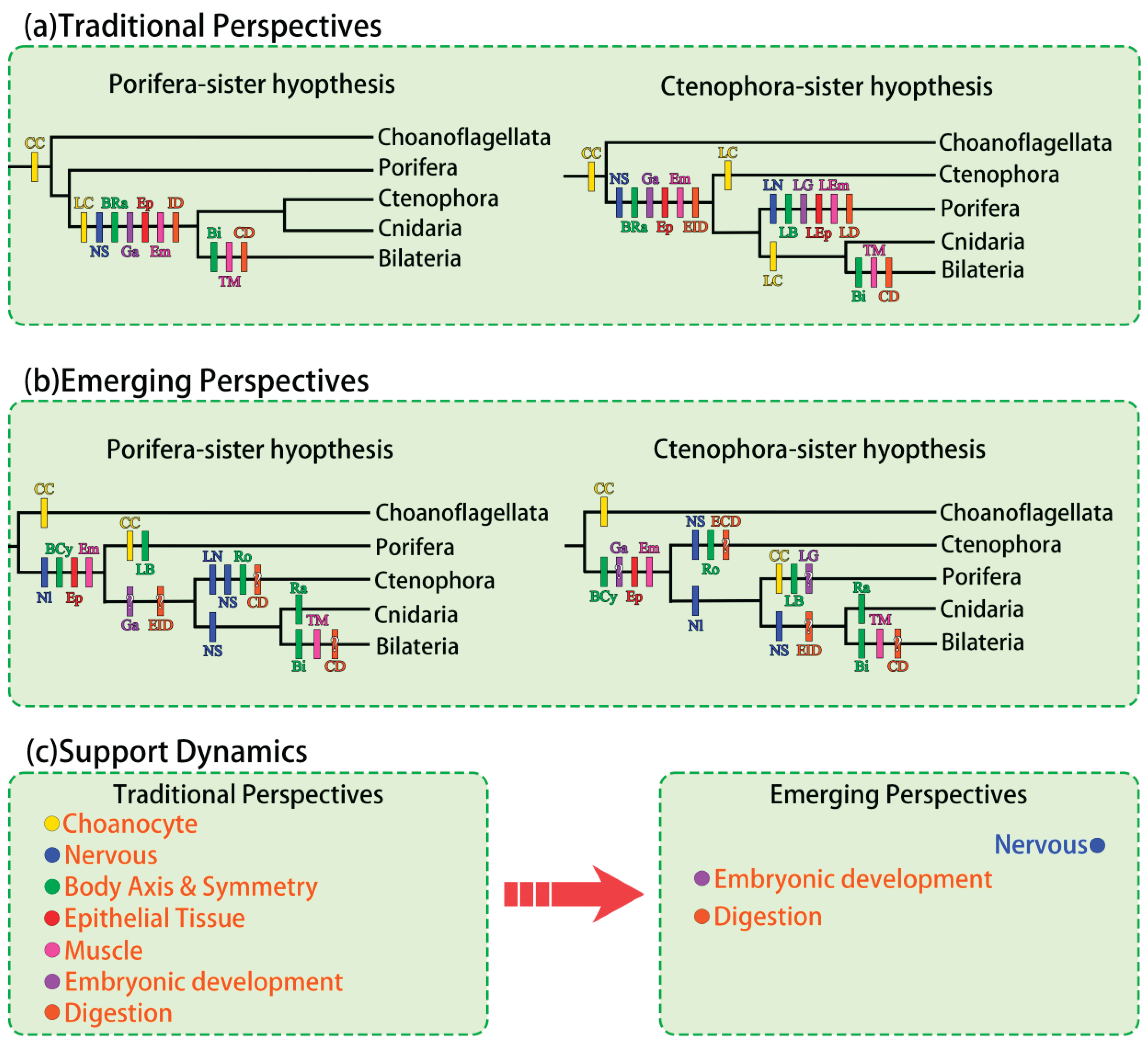

To intuitively compare traditional perspectives under the Porifera-sister hypothesis with emerging perspectives from the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis—in light of recent evidence that reshapes our understanding of trait evolution and redefines the narrative under each phylogenetic scenario—we present a simplified phylogenetic tree based on the preceding discussion (

Figure 2a,b). Because the schematic tree emphasizes broad evolutionary trends and is sensitive to phylogenetic topology, Placozoa is excluded to avoid complications from its deeply uncertain position [

71,

90,

93,

94]. In contrast, earlier comparisons in this paper are less affected by this uncertainty, as they do not rely on exact tree placement.

To summarize, the previously accepted Porifera-sister hypothesis was likely supported by the underestimated complexity of sponges and the independent gain or loss of key traits. While direct support for the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis remains limited, growing evidence has increasingly challenged the morphological and embryological basis of the Porifera-sister view (

Figure 2c). Notably, once clarified, these observational traits are generally less susceptible to methodological bias than molecular sequences—even so, further evidence is needed to settle the debate.

5. Paleontological Evidence

Paleontology, as one of the earliest-developed disciplines in evolutionary biology, has accumulated a large body of evidence—though much of it remains highly controversial and subject to significant bias. These lines of evidence can be broadly divided into two categories according to their logical approach to the problem: one seeks to constrain the earliest possible appearance of taxa, and the other aims to reconstruct evolutionary trajectories through comparative morphology and phylogeny.

5.1. Evidence Based on Constraining the Earliest Emergence

A common and intuitive approach assumes that the earlier its first appearance in the stratigraphic record, the earlier it is likely to have originated. Depending on methodology and the focus of debate, fossil evidence can be divided into traditional and molecular fossil evidence.

5.1.1. Traditional Fossil Evidence

This section concerns traditional fossil records—body fossils, trace fossils, and other physical remains of organisms. Compared with molecular fossils, traditional fossils preserve more morphological traits and are thus often more reliable for taxonomic identification.

To assess the reliability of fossil evidence, Antcliffe et al. proposed three criteria [

95]:

Characters criterion – whether the diagnostic traits used to assign a fossil to a particular group are well defined and phylogenetically informative;

Diagnosis criterion – whether those characters are demonstrably present in the fossil;

Age criterion – whether geochronological dating is available.

To standardize temporal interpretation, a geochronological minimum constraint has been recommended [

95,

96]. For a fossil dated to n ± m Ma, the minimum constraint age is defined as (n − m) Ma.

According to these standards, the oldest reliable sponge fossil is

Helicolocellus cantori from the late Ediacaran Dengying Formation, Hubei, China [

97], constrained between 551.1 ± 0.7 Ma and 543.4 ± 3.5 Ma [

98,

99], giving a minimum constraint of 539.9 Ma. The oldest reliable ctenophore fossil comes from the early Cambrian Meishucun section, Shaanxi, China, within the

Anabarites trisulcatus–

Protohertzina anabarica assemblage, represented by embryonic fossils attributed to ctenophores [

100,

101,

102]. These are dated between 541.5 ± 0.5 Ma and 526.5 ± 1.1 Ma [

103,

104], with a minimum constraint of 525.4 Ma. At face value, this apparent age difference could suggest that sponges predate ctenophores.

However, such an inference must be tempered by taphonomic biases. Sponges are inherently more likely to fossilize due to their rigid skeletal components, whereas ctenophores—being almost entirely soft-bodied—are far less likely to be preserved [

95]. Exceptions are rare, such as the extinct group Scleroctenophora, which possessed organic frameworks [

105]. This systematic taphonomic bias means that the fossil record naturally favors the discovery of sponges, while the likelihood of preserving ctenophores is extremely low.

Moreover, fossil discovery is strongly contingent upon chance, and early members of a lineage may have lacked diagnostic features necessary for recognition [

95]. Consequently, traditional fossil evidence can seldom reveal the true earliest appearance of a lineage—it merely defines a minimum age constraint by which that lineage must have existed.

The chronological gap between the earliest reliable sponge and ctenophore fossils is relatively small, with overlapping age uncertainties, and is therefore unlikely to represent a meaningful temporal difference. Moreover, numerous older but controversial specimens satisfying only partial diagnostic criteria continue to be debated (sponges: [

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112], ctenophores: [

113]). This implies that even older examples may yet be discovered.

Transitional fossils between sponges and other early metazoans have not been identified, while putative intermediates between ctenophores and hydroid-like ancestors appear later than the earliest known ctenophore fossils [

102,

114]. This pattern suggests that earlier transitional forms have yet to be discovered. Hence, the record of the “earliest fossils” is expected to remain fluid, subject to continual revision, and its phylogenetic signal correspondingly fragile.

5.1.2. Molecular Fossil Evidence

Molecular fossils, or biomarkers, are organic compounds produced by specific organisms and preserved in sediments or petroleum [

115]. Detection of such a biomarker in a geological formation implies the presence of its biological producer at that time. Compared with traditional fossils, biomarkers are less dependent on exceptional preservation and are more evenly distributed, thereby offering potentially broader temporal coverage—though not necessarily a more complete evolutionary record.

No diagnostic biomarker is yet known for ctenophores, but two generations of biomarkers have been proposed for sponges.

The first-generation sponge biomarkers are C30 steranes, including 24-isopropylcholestane (24-ipc) and 26-methylstigmastane (26-mes), once thought to derive exclusively from demosponges [

116,

117,

118]. Their relative abundance, normalized to the more ubiquitous 24-n-propylcholestane (24-npc), was used to infer sponge presence. However, later studies revealed that some rhizarians also synthesize appreciable quantities of these steranes—exceeding 20% of total sterols after correction for dilution effects caused by dietary input and symbiotic algae. Moreover, the 24-ipc/24-npc ratio in rhizarians spans the entire range observed in sponges. As a result, the specificity of these first-generation biomarkers is now regarded as weak, and they are considered supportive only when corroborated by traditional fossil evidence [

119].

The second-generation biomarker—24-sec-butylcholestane (24-secbc), a C31 sterane with potential sponge specificity—was recently identified as a potentially sponge-specific compound [

120]. While certain brown algae (e.g.

Aureococcus anophagefferens) can synthesize trace amounts of 24-secbc, its abundance in sponges can reach up to 2.4% of total C30 sterols [

120]. Analyses of gene distribution indicate that algal lineages lacked the biosynthetic capacity to produce 24-secbc in the Ediacaran [

121], reinforcing the biomarker’s reliability.

Based on 24-secbc detection in the Masirah Bay Formation, Shawar et al. inferred the presence of sponges by the early Ediacaran [

120], giving an upper bound of 570.2 ± 1.1 Ma and a minimum constraint of 569.1 Ma [

122]—substantially earlier than the oldest credible ctenophore fossil record.

Even so, several caveats must be addressed. Because molecular fossils are more readily preserved and detected, they inherently yield earlier appearance estimates than traditional fossils; combined with the fact that biomarkers are currently known only for sponges, this jointly introduces a directional bias toward that lineage.

Furthermore, if early organisms had not yet evolved the capacity to synthesize diagnostic compounds, the biomarker record would remain silent, regardless of the lineage’s actual existence.

Finally, the second-generation biomarker has only recently been proposed, and its specificity has been tested in a limited number of taxa. While brown algae have been confirmed to produce only trace levels, other groups—particularly rhizarians, which have already produced false positives in the past—have not yet been comprehensively screened. Hence, the phylogenetic exclusivity of 24-secbc remains to be validated.

Taken together, the first-generation sponge biomarkers have been largely discredited as reliable taxonomic indicators, whereas the newly proposed second-generation biomarker requires further verification of its specificity. Moreover, although these molecular data appear to suggest an earlier emergence of sponges, this pattern largely reflects a systematic bias—since biomarkers are currently known only for sponges and, by nature, tend to yield earlier apparent ages than traditional fossils.

In sum, both traditional and molecular fossil evidence are affected by systematic biases favoring sponges and both are incomplete with respect to evolutionary history. Traditional fossil data suffer from limited phylogenetic robustness, whereas molecular fossils still lack fully established specificity. Although both types of evidence currently converge on a sponge-first scenario, this agreement should be regarded as provisional rather than confirmatory, and interpreted with considerable caution.

5.2. Evidence Based on Reconstructing Evolutionary Trajectories

Beyond constraining absolute appearance times, evolutionary relationships can also be inferred from relative evidence—by identifying transitional forms and reconstructing morphological phylogenies. This approach incorporates a broader range of morphological and anatomical data, and is therefore relatively more comprehensive and robust.

No reliable transitional fossils have yet been identified linking sponges to other metazoans. By contrast, some progress has been made for ctenophores.

The dinomischids—a group of extinct hydroid-like organisms from the early Cambrian—display a mosaic of traits relevant to this problem [

102]. Their solitary, hydroid-like morphology resembles the inferred ancestral state of cnidarians [

123]. Each tentacle bears pinnules equipped with rows of compound cilia oriented distally, potentially homologous to the large locomotory cilia of modern ctenophores [

102,

124]. Dinomischids also exhibit an organic skeleton and cushion plate structures comparable to those of fossil and extant ctenophores [

102,

105]. These similarities suggest that a basal cnidarian lineage may have given rise to skeletal ctenophores (Scleroctenophora), which subsequently evolved into the soft-bodied extant forms.

In addition, several morphology-based phylogenetic trees recover both Porifera as the sister group to all other metazoans and a monophyletic Coelenterata (comprising Cnidaria and Ctenophora) [

97,

102,

125]. Under this topology, if ctenophores and cnidarians are indeed sister taxa, sponges must necessarily occupy the basal-most position (

Figure 2a). These findings thus collectively favor a Porifera-sister hypothesis.

Nevertheless, alternative interpretations of dinomischid fossils remain possible:

The common ancestor of metazoans may already have been cylindrically symmetric [

71], a body plan superficially similar to the hydroid form; moreover, skeletal biomineralization was widespread in the Ediacaran–Cambrian interval [

126]. This raises the possibility that dinomischids represent either the metazoan ancestor itself or a case of convergence.

The earliest dinomischid fossils postdate known ctenophores, whereas some controversial taxa such as

Eoandromeda octobrachiata are older but exhibit more derived traits [

102]. This paradox suggests both the potential existence of undiscovered basal lineages and the possibility that dinomischids were derived from ctenophores rather than ancestral to them.

Because soft-bodied ctenophores have an exceptionally poor preservation potential, their role in early metazoan evolution remains obscure. This taphonomic gap further complicates phylogenetic interpretation. Overall, the evolutionary significance of dinomischid fossils remains ambiguous, and the signal they provide is limited.

Similar caution must be applied when interpreting morphological phylogenies. Many traits that distinguish ctenophores and cnidarians as products of convergent evolution—such as embryonic development, locomotion, specialized cell types, muscle tissues, and digestive and neural architectures [

58,

61,

92,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134,

135]—cannot be preserved or reliably recognized in the fossil record. It is therefore unsurprising that morphology-based analyses tend to recover traditional topologies reflecting shared but non-homologous features. Furthermore, the temporal–morphological incongruence of several controversial fossils continues to challenge tree-based reconstructions [

102].

Taken together, interpretations of putative transitional fossils are inherently probabilistic, as their morphological features often permit multiple evolutionary scenarios. Moreover, the limited anatomical information preserved in fossils introduces substantial uncertainty and potential bias into phylogenetic reconstruction. As a result, although these fossil-based analyses tend to support a Porifera-sister topology, the explanatory power of such evidence remains constrained by both taphonomic limitations and interpretive subjectivity.

Ultimately, whether constraining the earliest fossil appearances or reconstructing evolutionary trajectories, both approaches consistently produce signals favoring a Porifera-sister relationship. However, because each dataset carries distinct biases and uncertainties, these signals remain weakly supported and limited in their interpretive power. Paleontological evidence alone, though indispensable, is thus methodologically insufficient to resolve the Porifera–Ctenophora controversy.

6. Discussion

In this section, we discuss and address several key questions that have emerged in this long-standing debate, including:

explaining the causes of discrepancies among different disciplines;

evaluating the resolving power of each methodological approach;

exploring possible ways to integrate different lines of evidence; and

assessing the overall tendencies of current evidence.

6.1. Why Are the Discrepancies Among Disciplines so Large?

These striking inconsistencies are not coincidental. Similar to the controversy over the sister-group relationship between ctenophores and sponges, the phylogenetic placement of Placozoa has also proven difficult to resolve [

89,

90,

93,

94]. Even in plants, analogous debates occur at the base of land plants, accompanied by strikingly similar discussions [

136,

137,

138,

139]. These recurring patterns indicate that the problem is intrinsic to the reconstruction of deep basal divergences.

The fundamental cause of these difficulties lies in the vast temporal depth separating the divergences in question. More specifically, deep-time divergence exerts its effects through several mechanisms:

Accumulation of confounding evolutionary events. Over long evolutionary periods, extensive convergence and reversals inevitably occur, especially among lineages that have evolved independently since their divergence. This effect is especially striking in morphology, where even highly complex structures such as nervous systems have evolved independently and converged, while sponges appear to have undergone remarkably extensive secondary loss of characters. In molecular phylogenetics, such phenomena are even more common, giving rise to LBA and tree incongruence. In paleontology, the effect is smaller but still notable: traditional fossils may differ so greatly from crown groups that their relationships become obscure, while molecular fossils may be difficult to interpret due to uncertainties in biomarker specificity.

Loss of evolutionary information. Although convergence can be viewed as a consequence of information loss, the mechanisms are distinct enough to warrant separate consideration. As seen in molecular sequences, saturation can erase phylogenetic signal, reducing sites to random noise. Large-scale gene or character loss across many taxa can similarly obliterate information, affecting both molecular and morphological analyses. In some cases, information loss arises directly from methodological constraints—for instance, molecular fossils preserve only chemical composition and concentration. Even traditional fossils, which appear to “fix” morphological characters in time, have effectively lost all molecular information. Unlike missing fossils, this kind of information loss affects entire clades or lineages, leaving no isolated remnants and thus representing a complete, irreversible loss of data.

Destruction of physical evidence. This issue is specific to paleontology: over geological time, physical fossils may be lost or damaged through physicochemical processes. In contrast to information loss, the discovery of a single well-preserved fossil can sometimes recover evolutionary information through comparison. Nevertheless, fossil destruction likely occurs more frequently than true information loss. Although molecular sequence loss in fossils might mechanistically resemble physicochemical damage, its lineage-wide and irreversible nature justifies treating it as information loss rather than physical destruction.

Asynchrony among disciplines. Evolutionary changes detected by one discipline may have little or no direct effect on others. For example, multiple minor-effect genetic changes may leave morphology largely unchanged, while a single regulatory mutation could drastically alter morphology but have little impact on sequence-based trees. Over long periods, this asynchronous accumulation amplifies discrepancies among data types. Notably, although the amplifying effect of time is not explicitly addressed, the issue of asynchrony among different lines of evidence had already been recognized [

140].

In summary, mechanisms 1–3 reflect the intrinsic resolution limits of each discipline—their inherent inability to infer topologies beyond a certain temporal depth (

Table 1). Mechanism 4 reflects cross-disciplinary asynchrony, where mismatched between the targets of investigation becomes increasingly magnified over evolutionary time.

We formally introduce the concept of a “Resolution Limit”, defined as the maximum temporal depth at which a given method can yield reliable phylogenetic inference. Although related ideas have been mentioned previously [

18,

27,

141,

142], they have not been explicitly formalized into a general framework. This paper provides a qualitative framework for understanding the factors influencing Resolution Limits and for comparing them across methods; future studies may seek to quantify these limits.

We also propose the term “Deep Basal Problem” to describe cases in which basal nodes become intrinsically difficult to resolve, as methodological Resolution Limits are exceeded and cross-disciplinary asynchrony is progressively amplified over time, leading to persistent conflicts among data types. Although analogous limitations have been independently recognized in studies of various deep divergences, these observations have rarely been synthesized into a general framework that explicitly accounts for methodological Resolution Limits and cross-disciplinary asynchrony. The Deep Basal Problem spans all major lineages of life, with the root of the animal tree merely representing one prominent example. Importantly, any robust solution to this issue would likely resolve analogous problems across the entire tree of life.

6.2. How Far Back in Time Can Different Methods Reliably Resolve Evolutionary Relationships?

To address this question, we first identify the factors that can extend the Resolution Limit, then evaluate the most promising approaches, followed by a brief assessment of the remaining ones.

6.2.1. Factors extending the Resolution Limit

A comprehensive way to identify these factors is to determine which ones mitigate the mechanisms 1–3 in

Section 6.1 (

Table 1):

Reducing the impact of confounding evolutionary events. This can be achieved when (I) such events are mechanistically improbable, (II) traits are insensitive to minor mutations, or (III) large data volumes dilute their effects.

Preservation of evolutionary information. Facilitated when (I) evolutionary rates are low, avoiding saturation; (II) multiple coordinated changes are required for loss, making complete erasure unlikely; or (III) large datasets buffer against random loss.

Ease of evidence acquisition. This includes (I) data readily obtainable from extant taxa (e.g., molecular sequences) and (II) ancient evidence that is both widespread and preservable (e.g., molecular fossils).

6.2.2. The Most Promising Approach: Highly Anti-Convergence and Highly Irreversible Marginal Instances (HACHIMI)

As discussed in

Section 3, certain rare events with low convergence potential and high irreversibility—such as FWM—exhibit exceptionally deep resolution capacity:

Resistance to confounding events. By definition, such events are inherently robust to convergence and reversal. For example, in FWM, convergence would require similar chromosomal fusions involving entire linkage groups, followed by an intermixing of gene order between them, while reversal would necessitate implausibly precise re-separation of merged genes [

40]; other potential alternative pathways are likewise highly improbable. Moreover, analyses of this type do not depend on exact sequences or gene order, making them insensitive to small-scale changes.

Resistance to information loss. The rarity of these events prevents saturation and secondary loss, and some (e.g., FWM) require multiple concurrent changes to alter a single character, providing strong resistance to data loss.

Accessibility of evidence. While not inherent to the definition, HACHIMI-type events are typically more readily detectable than traditional fossils, which are the main exception.

Furthermore, rare events can harness information inaccessible to other methods. For instance, mitochondrial sequences evolve too rapidly for reliable phylogenetic inference, yet mitochondrial gene transfer—a type of rare event—can still provide useful information [

51].

Although previous reviews have noted the phylogenetic value of rare events, they have primarily focused on genomic changes, generally without emphasizing the combined importance of low convergence and high irreversibility nor discussed their role in extending Resolution Limits [

44]. We therefore propose the dedicated term “Highly Anti-Convergence and Highly Irreversible Marginal Instance (HACHIMI)” to formalize this distinction, which refers to rare evolutionary events that simultaneously exhibit high irreversibility and low convergence potential. HACHIMIs are not restricted to molecular biology; rather, they can occur in any domain exhibiting similar evolutionary properties and are particularly well-suited for addressing Deep Basal Problems across major lineages.

However, it must be acknowledged that some events currently classified as HACHIMI may later be excluded as our understanding of convergent and reversible potential evolves—for instance, complex systems like nervous structures once thought impossible to converge are now known to do so. Finally, due to their rarity, HACHIMIs may be difficult to identify, meaning that the accumulation of detectable and practically applicable HACHIMI markers by researchers will be slow; and in lineages lacking such events, they can provide no information at all.

6.2.3. Resolution Limits of Other Approaches

Molecular sequence evidence. High rates of convergence and reversal generate severe conflicts (e.g., LBA), mitigated only partially by large datasets. Saturation and gene loss are common, and although sequences are easy to obtain from extant taxa, the method’s Resolution Limit remains shallow.

Embryological and morphological evidence. While convergence and reversal occur, high-resolution imaging and molecular tools now enable detailed identification and differentiation of these traits (e.g., the nervous system of ctenophores). Because most morphological traits are polygenic, true loss is rare, and residual evidence can often be detected. However, data collection is labor-intensive and prone to incompleteness. Thus, despite a potentially deeper Resolution Limit, accumulation of high-quality data is slow and low-quality noise remains common.

Traditional fossil evidence. Traditional fossils preserve limited, coarse-grained morphological information and rarely allow assessment of development or molecular traits. Crucially, specimens are rare. Consequently, their Resolution Limit is extremely shallow.

Molecular fossil evidence. Biomarkers may be produced by multiple taxa, and specificity is difficult to confirm. Apart from chemical composition, nearly all information is lost. Despite their abundance and ease of sampling, molecular fossils have a very limited resolution capacity.

In summary, although molecular phylogenies dominate current research, embryological and morphological approaches may actually reach deeper Resolution Limits—thanks to technological advances integrating imaging and molecular data. Future improvements in error correction and dataset expansion may enhance molecular methods, but embryological and morphological evidence already yield high-quality results today. Although both types of paleontological evidence have limited resolution capacity, traditional fossils yield more taxonomically robust but less frequently available data compared to molecular fossils, whose ease of recovery is offset by low reliability.

Overall, HACHIMIs currently provide the deepest Resolution Limit, followed by morphological and embryological evidence, then molecular sequences, traditional fossils, and finally molecular fossils (

Table 2). HACHIMIs thus show great promise for resolving Deep Basal Problems, while morphological and embryological methods remain undervalued and molecular sequence analyses urgently require methodological improvements.

6.3. How Can Different Approaches be Integrated?

This question directly addresses mechanism (4) described in

Section 6.1—namely, the cross-disciplinary asynchrony that arises over deep evolutionary timescales. A straightforward strategy is to incorporate all available lines of evidence—either simultaneously or sequentially—into the analysis, rather than relying solely on the signal from the most methodologically robust dataset.

Although such integrative approaches have been widely explored in previous studies [

140,

143,

144,

145,

146,

147,

148,

149], and given that this paper does not focus on methodological development, we do not attempt to construct a formal analytical framework. Instead, this section highlights several guiding considerations for integration, with the aim of illustrating their potential relevance to the current problem and offering a conceptual starting point for future research.

The first step is to identify the major categories of data that may be integrated. At a minimum, these include:

Molecular sequences – encoding divergence times and gene evolutionary histories;

HACHIMIs – rare events offering high-resolution support for specific nodes;

Embryology and morphology – preserving phenotypic evolutionary trajectories;

Paleontology – providing direct records of lineage existence and transitions.

The second step involves clarifying how trait-based data can be methodologically combined. When working with two data types, one can either merge them into a unified dataset for simultaneous inference, or analyze them separately and integrate the results afterward [

140]. Previous studies have shown that merging data with similar evolutionary properties can reduce noise from stochastic variation [

140], while combining datasets of vastly different sizes may result in signal dilution, where smaller datasets become statistically negligible [

147]. A potentially effective strategy, therefore, is to merge data that are both mechanistically similar and comparable in scale—such as embryological, morphological, and paleontological datasets—while treating divergent or imbalanced datasets separately prior to synthesis [

146,

147].

Lastly, the temporal information from paleontology and molecular sequences may be unified through the use of fossil calibrations in molecular clock models [

143,

144,

145], providing a cross-disciplinary bridge between time-resolved and sequence-based phylogenetic inference.

As this is a review article rather than an empirical study, the method discussed here is intended as a conceptual suggestion to illustrate its potential, and has not been implemented in practice.

6.4. Which Hypothesis Is Currently Better Supported?

Because this paper did not directly implement the integration scheme described in

Section 6.3, our assessment here is qualitative and based on the comparative Resolution Limits discussed in

Section 6.2.

HACHIMI evidence (FWM) supports the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis.

Morphological and embryological evidence: recent high-quality studies tend to be neutral or mildly support the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis, whereas older, less-resolved evidence often supports the Porifera-sister hypothesis (

Figure 2c). Overall, Porifera-sister evidence remains quantitatively more abundant, but Ctenophora-sister evidence exhibits greater methodological rigor and data reliability, indicating a trend increasingly favoring the latter.

Molecular sequence evidence remains highly contentious but currently leans weakly toward the Porifera-sister hypothesis.

Paleontological evidence (both traditional and molecular) is too fragmentary and uncertain to strongly support either side.

In conclusion, methods with higher Resolution Limits generally favor the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis, while approaches with lower limits or greater methodological uncertainty tend to support Porifera-sister. Taken together, the current body of evidence—particularly from high-resolution methodologies—moderately favors the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis. To move beyond current limitations, future studies that formally implement integrative frameworks like the one proposed here may offer a path toward decisively resolving the root of the animal tree.

7. Conclusion

The question of the root of the animal tree remains a central and unresolved issue in evolutionary biology. Despite decades of research, different types of evidence continue to yield conflicting signals. Molecular sequence analyses—from early ribosomal RNA trees to large-scale phylogenomic datasets—have supported both the Porifera-sister and Ctenophora-sister hypotheses, with outcomes depending heavily on model choice, data treatment, and outgroup selection. Rare molecular events have emerged as an independent and theoretically powerful line of evidence, valued not for tree-based inference but for their intrinsic properties of irreversibility and anti-convergence. Morphological and embryological data, long undervalued in the molecular era of phylogenetics, have recently shown renewed potential in explaining the complexity of early animal evolution. Fossil evidence remains indispensable but is constrained by preservation bias, incomplete records, and limited diagnostic power of early traits. However, these bodies of evidence are often mutually contradictory, making it difficult to construct a unified phylogenetic picture.

These persistent contradictions reflect more than technical disagreements; they point to a deeper structural challenge in reconstructing deep evolutionary history. Over vast timescales, phylogenetic signals degrade due to convergence, reversal, and loss—as well as the gradual destruction of physical evidence—while different types of data evolve and erode at asynchronous rates. This leads to systemic inconsistencies, which we define as the Deep Basal Problem—a pattern not limited to metazoans but recurrent across the tree of life wherever early divergences are in question.

To address the persistent difficulty of resolving early animal relationships, we propose the concept of a Resolution Limit—the point beyond which phylogenetic signal degrades across methods. Rare events with both low convergence potential and high irreversibility (i.e., HACHIMIs), such as fusion-with-mixing, may retain deep-time signal and represent promising candidates for future focus. Morphological and embryological traits, though long undervalued, remain relevant due to recent methodological advances. As a preliminary step, we suggest exploring cross-disciplinary data integration through flexible, problem-specific frameworks.

Ultimately, although no single dataset has definitively resolved the root of the animal tree, high-confidence signals from HACHIMIs—specifically FWM—alongside emerging high-quality morphological and embryological data increasingly support the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis. More broadly, this paper outlines a conceptual framing for early-divergence problems—introducing the Deep Basal Problem, the Resolution Limit, and the potential role of HACHIMIs. Together, these ideas emphasize that resolving deep phylogenies may depend more on integrative approaches than on increasing data volume. In any case, these developments have already begun—and will continue—to reshape our fundamental understanding of biological evolution, driving substantial methodological advances in phylogenetic reconstruction.

AI Tools Disclosure: ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used in the preparation of this manuscript to assist with language refinement, sentence restructuring, preliminary literature exploration, and reference formatting. All AI-assisted content was critically reviewed and edited by the author. The author accepts full responsibility for the final content. ChatGPT is not listed as an author, in accordance with Preprints.org and COPE authorship guidelines.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed in this study. All data referenced are from published sources cited in the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dou-Dou Yuan for assistance with figure preparation. I am grateful to Professor Wen-Ya Zhang for her valuable comments and suggestions on earlier versions of the manuscript. I also thank Professor Xiao-Feng Li for inspiration on the research topic and for help with access to relevant literature.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Chronological summary of major molecular studies on the root of the animal tree. Study outcomes are indicated by color: blue for support of the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis, orange for the Porifera-sister hypothesis, and black for neutral or unresolved position. Based on

Section 2.

Table A1.

Chronological summary of major molecular studies on the root of the animal tree. Study outcomes are indicated by color: blue for support of the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis, orange for the Porifera-sister hypothesis, and black for neutral or unresolved position. Based on

Section 2.

| Year |

Long-Branch Attraction (LBA) |

Tree Incongruence |

| Model Complexity |

Data Simplification |

Outgroup Choice |

“Observed” Factors |

“Unobserved” Factors |

| 2008 |

First EST-based phylogeny supporting the Ctenophora-sister hypothesis [3] |

| 2013 |

First ctenophore whole-genome data further supporting Ctenophora-sister [12] |

| 2015 |

Site-heterogeneous models

(e.g., CAT) show better fit than site-homogeneous models [6,7] |

Data excluding nuclear proteins mostly support Ctenophora-sister [6] |

Homogeneous models show no effect of outgroup choice [6] |

|

Correcting underestimation of gene loss restores Porifera-sister topology from Ryan et al.’s dataset [7] |

|

Excluding highly conserved proteins (e.g., ribosomal genes) exacerbates LBA [7] |

Under CAT models, closely related outgroups recover Porifera-sister [7] |

| 2017 |

|

First use of amino acid recoding recovers Porifera-sister [23] |

|

|

|

| 2020 |

|

|

|

|

Widespread gene loss, especially in controversial lineages [37] |

| 2021 |

CAT models found to be overfitted; simpler site-heterogeneous models support Ctenophora-sister [8] |

Amino acid recoding introduces biases by reducing information content [8] |

Outgroup choice has no effect under simple site-heterogeneous models [8] |

|

|

| 2022 |

|

|

|

Tree incongruence lower under Porifera-sister than Ctenophora-sister, mainly due to incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) [9] |

|

| 2025 |

|

Used only genes with consistent signals across concatenation and consensus analyses, recovering Porifera-sister [28] |

|

|

|

References

- Haeckel, E. Generelle Morphologie der Organismen (2 Bde); G. Reimer, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levit, G. S.; Hoßfeld, U.; Naumann, B.; Lukas, P.; Olsson, L. The biogenetic law and the Gastraea theory: From Ernst Haeckel's discoveries to contemporary views. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 2022, 338(1-2), 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, C. W., Hejnol, A., Matus, D. Q., Pang, K., Browne, W. E., Smith, S. A., ... & Giribet, G. Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature 2008, 452(7188), 745–749. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, C. W.; Giribet, G.; Edgecombe, G. D.; Hejnol, A. Animal phylogeny and its evolutionary implications. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 2014, 45(1), 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, C. W.; Leys, S. P.; Haddock, S. H. The hidden biology of sponges and ctenophores. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2015, 30(5), 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelan, N. V.; Kocot, K. M.; Moroz, L. L.; Halanych, K. M. Error, signal, and the placement of Ctenophora sister to all other animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112(18), 5773–5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisani, D., Pett, W., Dohrmann, M., Feuda, R., Rota-Stabelli, O., Philippe, H., ... & Wörheide, G. Genomic data do not support comb jellies as the sister group to all other animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112(50), 15402–15407. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shen, X. X.; Evans, B.; Dunn, C. W.; Rokas, A. Rooting the animal tree of life. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021, 38(10), 4322–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, B.; Kern, A.; Hahn, M. Accurate detection of incomplete lineage sorting via supervised machine learning. bioRxiv Preprint. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumbach, T. Ctenophora. In Handbuch der Zoologie; Krumbach, T., Starck, D., Eds.; W. de Gruyter: Berlin, 1925; pp. 905–995. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith, T. M.; Allsopp, M. T. E. P.; Chao, E. E.; Boury-Esnault, N.; Vacelet, J. Sponge phylogeny, animal monophyly, and the origin of the nervous system: 18S rRNA evidence. Canadian Journal of Zoology 1996, 74(11), 2031–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J. F., Pang, K., Schnitzler, C. E., Nguyen, A. D., Moreland, R. T., Simmons, D. K., ... & Baxevanis, A. D. The genome of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi and its implications for cell type evolution. Science 2013, 342(6164), 1242592. [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Cases in which parsimony or compatibility methods will be positively misleading. Systematic Zoology 1978, 27(4), 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, P. J.; Howe, C. J.; Bryant, D. A.; Beanland, T. J.; Larkum, A. W. D. Substitutional bias confounds inference of cyanelle origins from sequence data. Journal of Molecular Evolution 1992, 34(2), 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, P. G.; Hickey, D. A. Compositional bias may affect both DNA-based and protein-based phylogenetic reconstructions. Journal of Molecular Evolution 1999, 48(3), 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akashi, H.; Gojobori, T. Metabolic efficiency and amino acid composition in the proteomes of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99(6), 3695–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermiin, L. S.; Ho, S. Y.; Ababneh, F.; Robinson, J.; Larkum, A. W. The biasing effect of compositional heterogeneity on phylogenetic estimates may be underestimated. Systematic Biology 2004, 53(4), 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S. Y.; Jermiin, L. S. Tracing the decay of the historical signal in biological sequence data. Systematic Biology 2004, 53(4), 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Maximum-likelihood estimation of phylogeny from DNA sequences when substitution rates differ over sites. Molecular Biology and Evolution 1993, 10(6), 1396–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, A. L.; Bruno, W. J. Evolutionary distances for protein-coding sequences: modeling site-specific residue frequencies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 1998, 15(7), 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lartillot, N.; Philippe, H. A Bayesian mixture model for across-site heterogeneities in the amino-acid replacement process. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2004, 21(6), 1095–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmond, A. K.; McLysaght, A. Evidence for sponges as sister to all other animals from partitioned phylogenomics with mixture models and recoding. Nature Communications 2021, 12(1), 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuda, R.; Dohrmann, M.; Pett, W.; Philippe, H.; Rota-Stabelli, O.; Lartillot, N.; ... & Pisani, D. Improved modeling of compositional heterogeneity supports sponges as sister to all other animals. Current Biology 2017, 27(24), 3864–3870. [CrossRef]

- Susko, E.; Roger, A. J. On reduced amino acid alphabets for phylogenetic inference. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2007, 24(9), 2139–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A. M.; Ryan, J. F. Six-state amino acid recoding is not an effective strategy to offset compositional heterogeneity and saturation in phylogenetic analyses. Systematic Biology 2021, 70(6), 1200–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelan, N. V.; Halanych, K. M. Available data do not rule out Ctenophora as the sister group to all other Metazoa. Nature Communications 2023, 14(1), 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X. X.; Hittinger, C. T.; Rokas, A. Contentious relationships in phylogenomic studies can be driven by a handful of genes. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2017, 1(5), 0126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenwyk, J. L.; King, N. Integrative phylogenomics positions sponges at the root of the animal tree. Science 2025, 390(6774), 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, W. C. Nucleic acid sequence phylogeny and random outgroups. Cladistics 1990, 6(4), 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsten, J. A review of long-branch attraction. Cladistics 2005, 21(2), 163–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]