Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

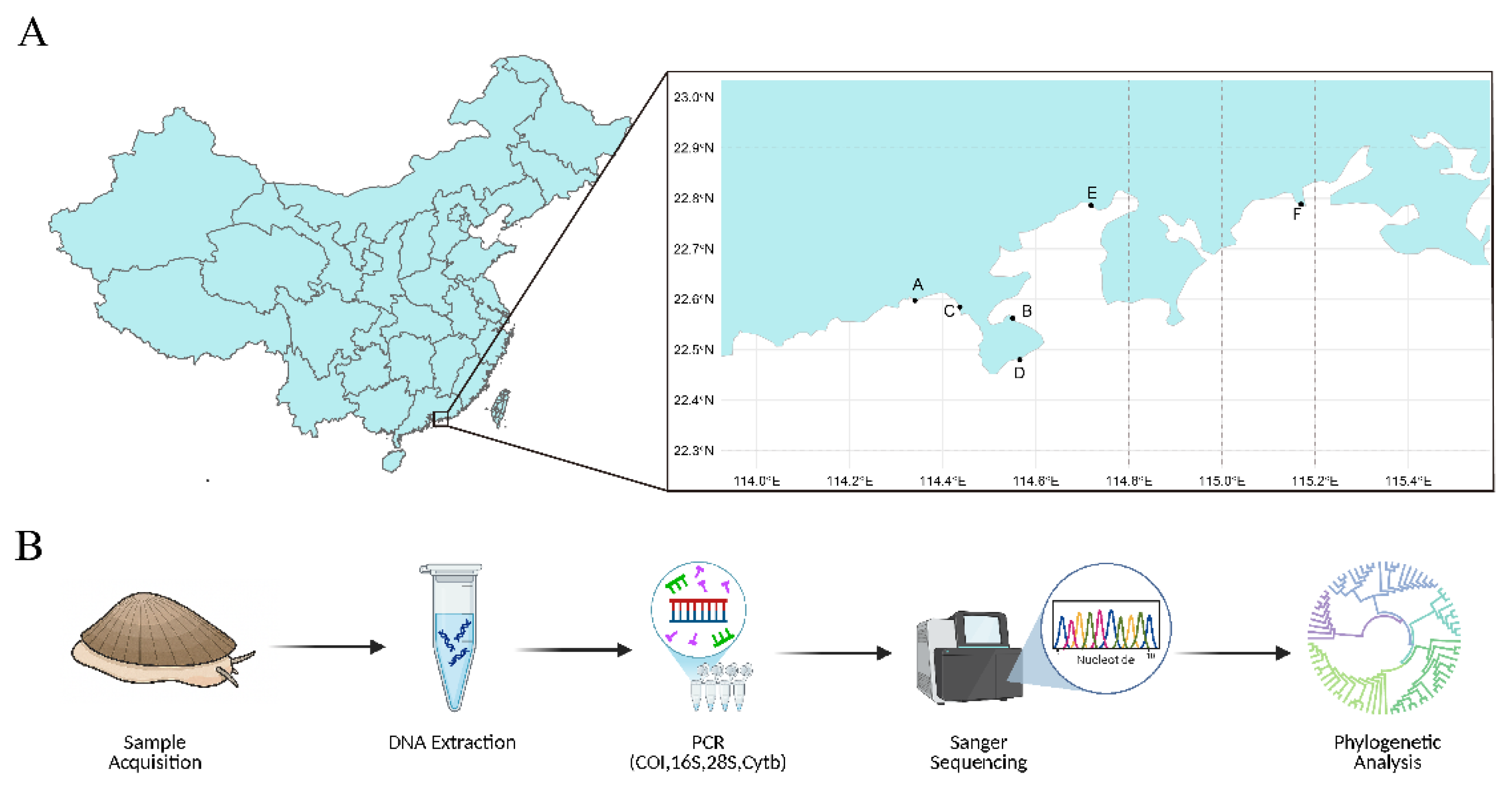

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Acquisition and Preprocessing

2.2. Genomic DNA Extraction

2.3. SEM Images Acquisition and Processing

2.4. PCR Reactions and Pre-Sequencing Preparation

2.5. Sequence Data Filtering and BLASTn

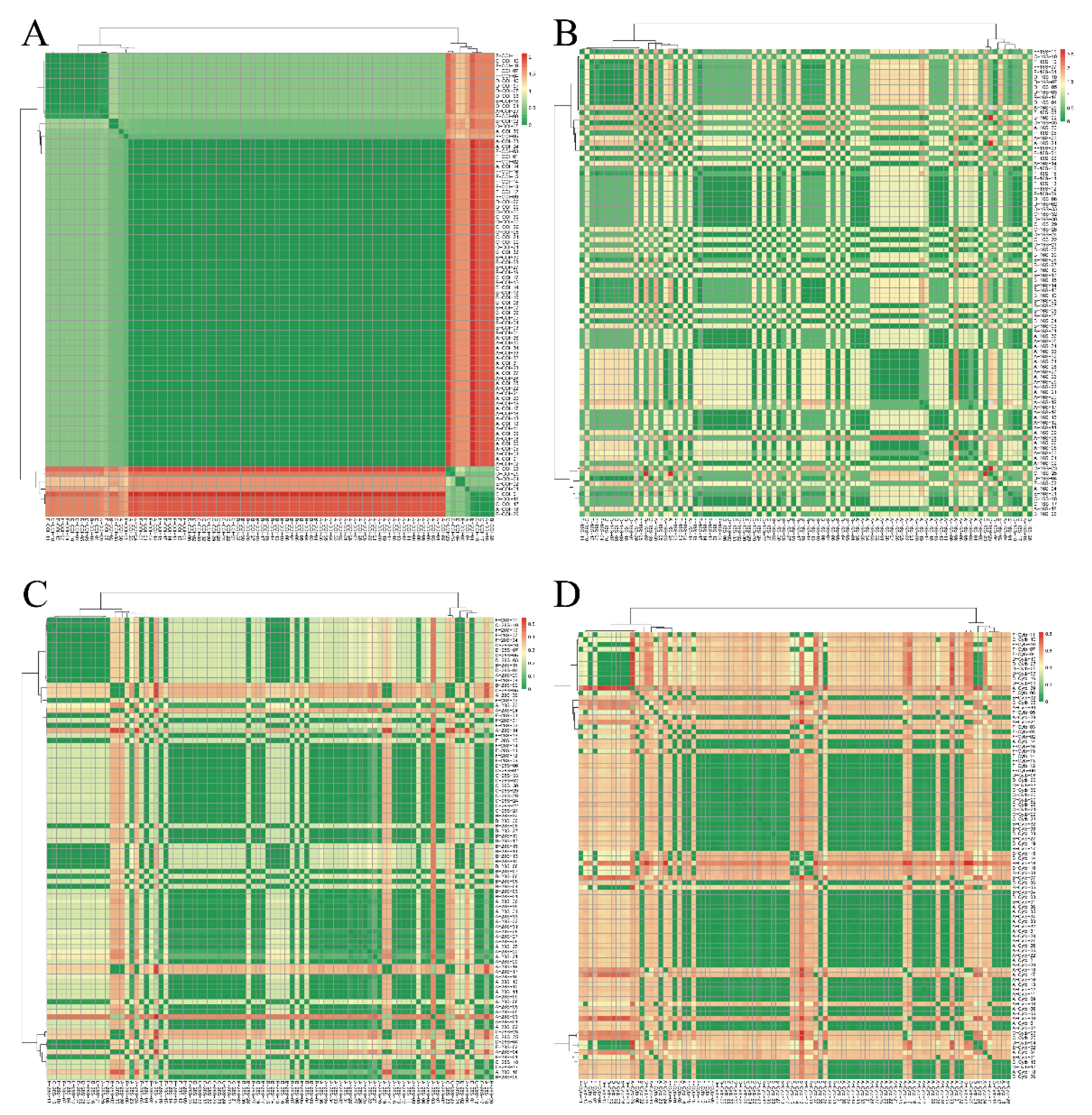

2.6. Genetic Distance Calculation and Hierarchical Clustering

2.7. ASAP Delimitation

2.8. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree Construction

3. Results

3.1. Cross-Regional Sampling of Limpets in Shenzhen and Adjacent Coastal Cities

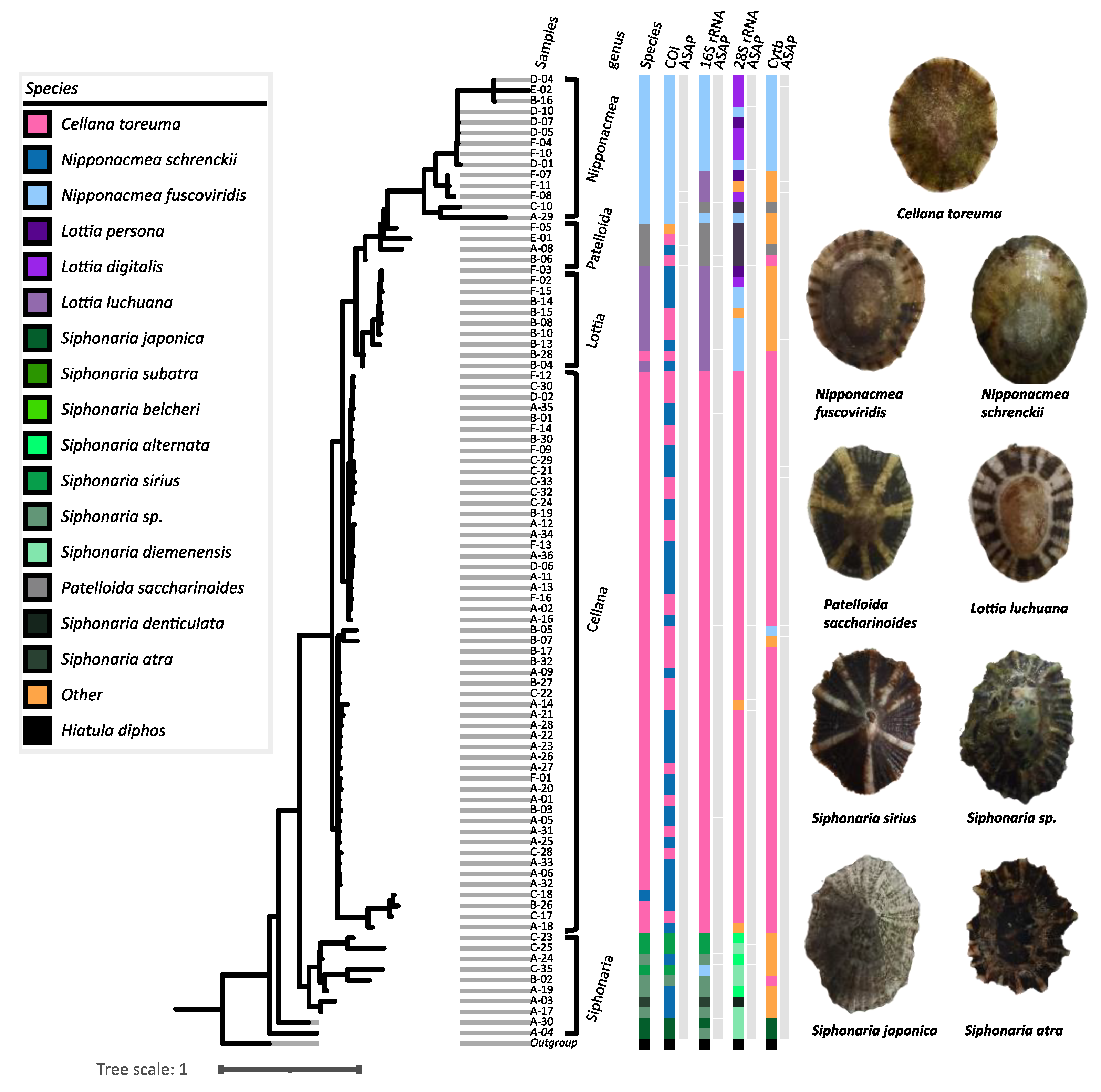

3.2. Conflicting Species Delimitations Within Different DNA Markers

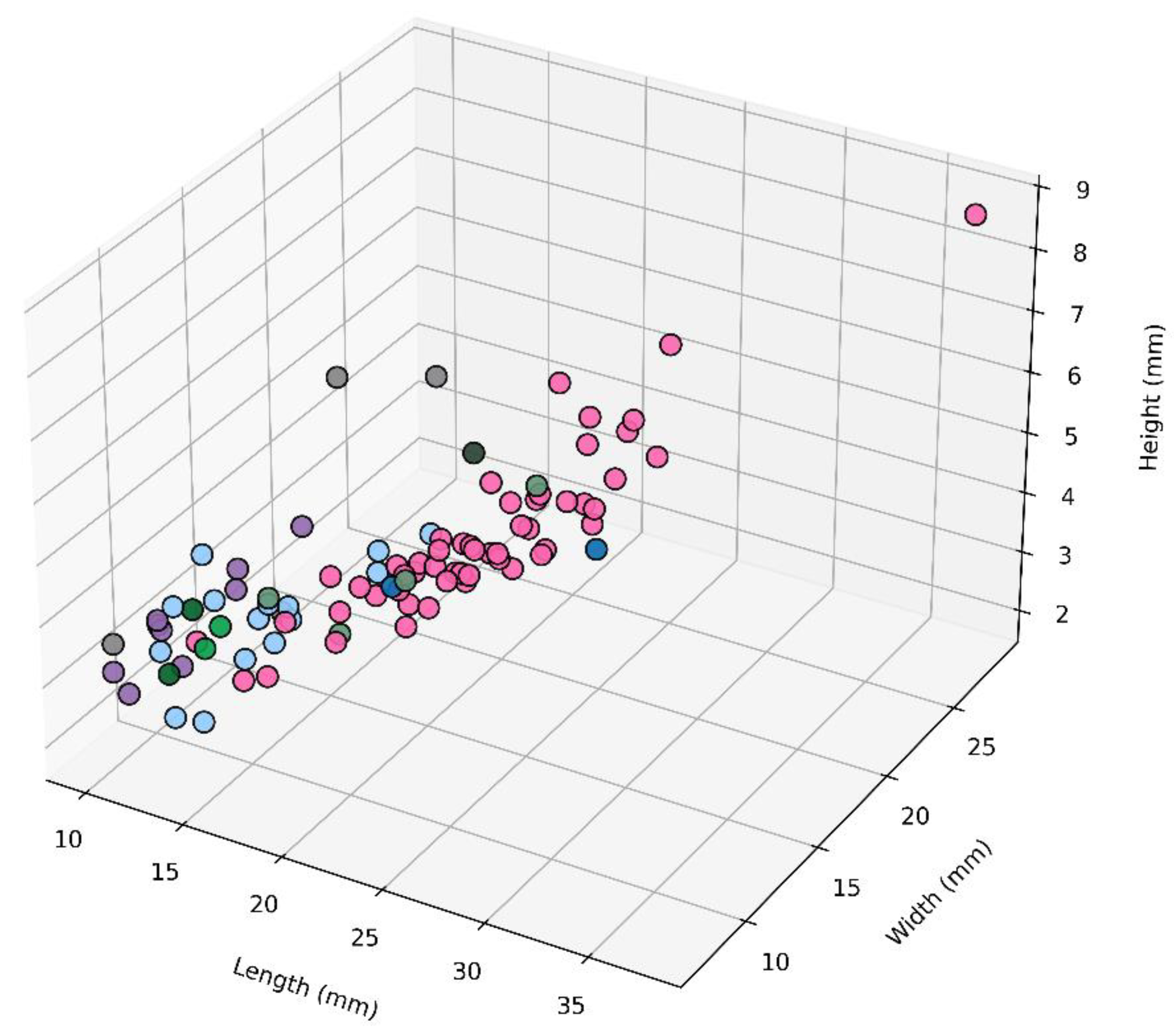

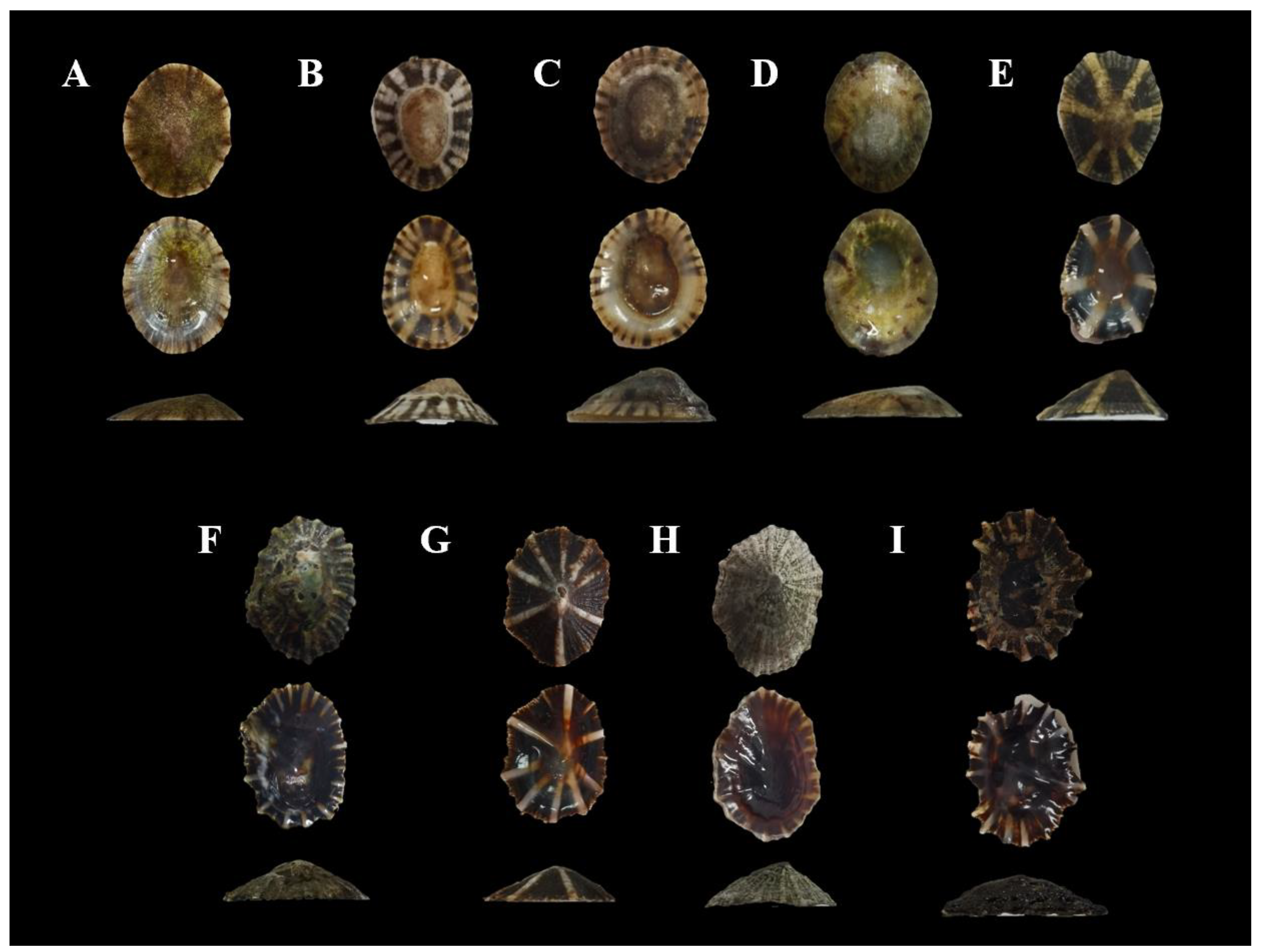

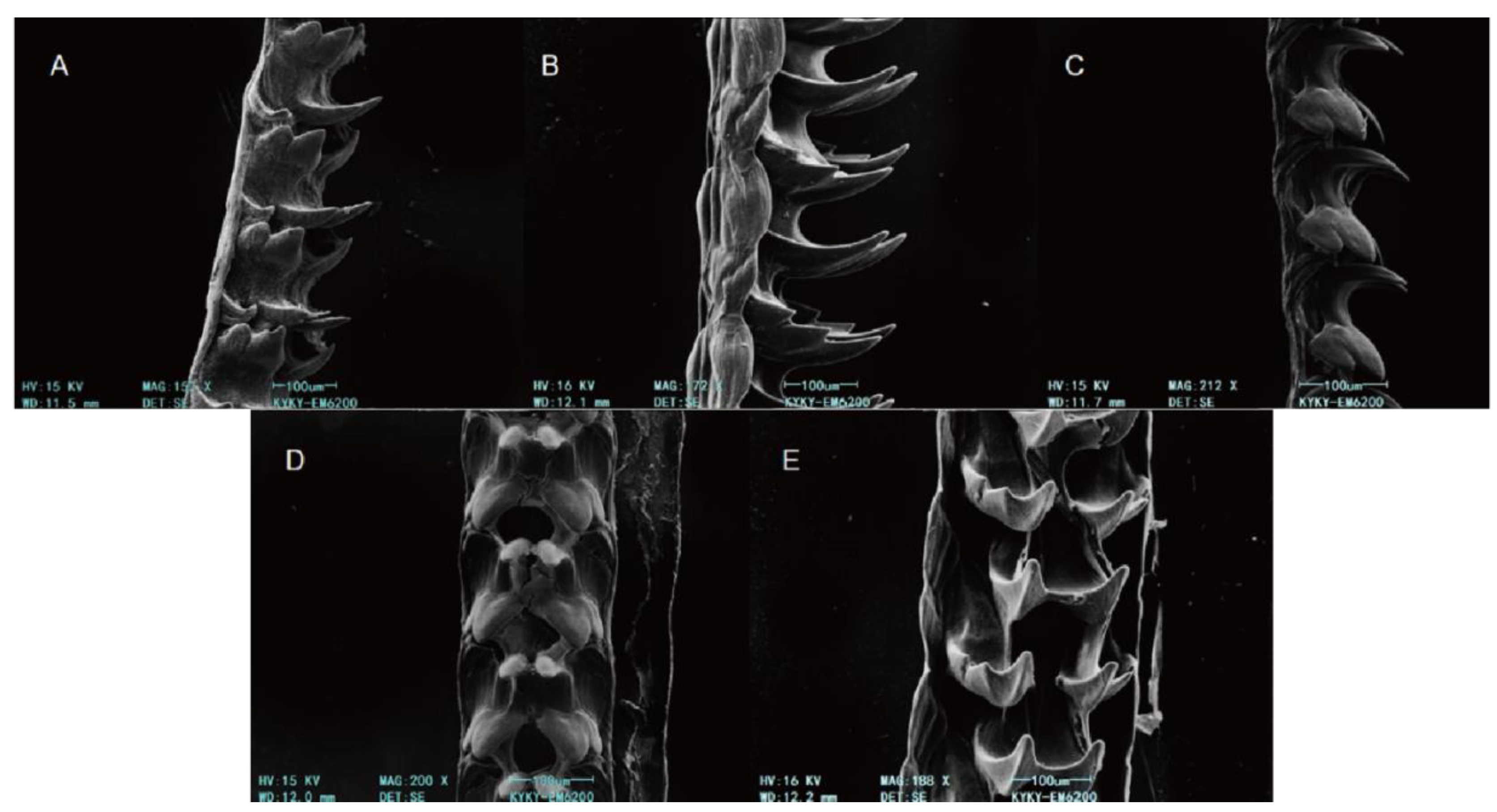

3.3. SEM-Based Morphological Insights of Patellida and Siphonariida

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Branch, G.; Trueman, E.; Clarke, M. Limpets: Evolution and Adaptation. The Mollusca 1985, 10, 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, R.M.; Tsao, Y.-F.; Nakano, T.; Chan, B.K.K. An Integrative Taxonomy Approach in Studying the Biodiversity of Intertidal Limpets in Taiwan. Mar. Biodivers. 2025, 55, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Spencer, H.G. Simultaneous Polyphenism and Cryptic Species in an Intertidal Limpet from New Zealand. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2007, 45, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, W.J.; García-Robledo, C.; Uriarte, M.; Erickson, D.L. DNA Barcodes for Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation. Trends in ecology & evolution 2015, 30, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, W.J.; Erickson, D.L. DNA Barcodes: Methods and Protocols. In DNA barcodes: Methods and protocols; Springer, 2012; pp. 3–8.

- Nakano, T.; Ozawa, T. Worldwide Phylogeography of Limpets of the Order Patellogastropoda: Molecular, Morphological and Palaeontological Evidence. Journal of Molluscan Studies 2007, 73, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Guo, Y.; Yan, C.; Ye, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, B.; Lü, Z. Comparative Analysis of the Complete Mitochondrial Genomes in Two Limpets from Lottiidae (Gastropoda: Patellogastropoda): Rare Irregular Gene Rearrangement within Gastropoda. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 19277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, T.; Sasaki, T. Recent Advances in Molecular Phylogeny, Systematics and Evolution of Patellogastropod Limpets. Journal of Molluscan Studies 2011, 77, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teruya, S.; Setiamarga, D.H.E.; Nakano, T.; Sasaki, T. Molecular Phylogeny of Nipponacmea (Patellogastropoda, Lottiidae) from Japan: A Re-Evaluation of Species Taxonomy and Morphological Diagnosis. ZK 2022, 1087, 163–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekimova, I.; Deart, Y.; Antokhina, T.; Mikhlina, A.; Schepetov, D. Stripes Matter: Integrative Systematics of Coryphellina Rubrolineata Species Complex (Gastropoda: Nudibranchia) from Vietnam. Diversity 2022, 14, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.-S.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.-L.; Huang, X.-W.; Dong, Y.-W. DNA Barcoding and Phylogeographic Analysis of Nipponacmea Limpets (Gastropoda: Lottiidae) in China. Journal of Molluscan Studies 2014, 80, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazón-Suástegui, J.M.; Fernández, N.T.; Valencia, I.L.; Cruz-Hernández, P.; Latisnere-Barragán, H. 28S rDNA as an Alternative Marker for Commercially Important Oyster Identification. Food Control 2016, 66, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, J.; Song, S.; Tornabene, L.; Chabarria, R.; Naylor, G.J.P.; Li, C. Multilocus DNA Barcoding – Species Identification with Multilocus Data. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 16601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, A.J.; Burgess, K.S.; Kesanakurti, P.R.; Graham, S.W.; Newmaster, S.G.; Husband, B.C.; Percy, D.M.; Hajibabaei, M.; Barrett, S.C. Multiple Multilocus DNA Barcodes from the Plastid Genome Discriminate Plant Species Equally Well. PloS one 2008, 3, e2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasmahapatra, K.; Mallet, J. DNA Barcodes: Recent Successes and Future Prospects. Heredity 2006, 97, 254–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, S. The Radular Morphology of Nassariidae (Gastropoda: Caenogastropoda) from China. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology 2011, 29, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.-L.; Stur, E.; Ekrem, T. DNA Barcodes and Morphology Reveal Unrecognized Species in Chironomidae (Diptera). Insect Systematics & Evolution 2018, 49, 329–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, K.W.; Rubinoff, D. Myth of the Molecule: DNA Barcodes for Species Cannot Replace Morphology for Identification and Classification. Cladistics 2004, 20, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Chiang, L.-P.; Hapuarachchi, H.C.; Tan, C.-H.; Pang, S.-C.; Lee, R.; Lee, K.-S.; Ng, L.-C.; Lam-Phua, S.-G. DNA Barcoding: Complementing Morphological Identification of Mosquito Species in Singapore. Parasites & vectors 2014, 7, 569. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Zheng, G.; Kuntner, M.; Agnarsson, I. Rapid Dissemination of Taxonomic Discoveries Based on DNA Barcoding and Morphology. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 37066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porebski, S.; Bailey, L.G.; Baum, B.R. Modification of a CTAB DNA Extraction Protocol for Plants Containing High Polysaccharide and Polyphenol Components. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 1997, 15, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, E.; Schliep, K. Ape 5.0: An Environment for Modern Phylogenetics and Evolutionary Analyses in R. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Molecular biology and evolution 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puillandre, N.; Brouillet, S.; Achaz, G. ASAP: Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning. Molecular Ecology Resources 2021, 21, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo Cabral, J. Shape and Growth in European Atlantic Patella Limpets (Gastropoda, Mollusca). Ecological Implications for Survival. Web Ecology 2007, 7, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, L.A.; Brooks, V.; Reeve, F.; Sowerby, G.B. (George B.; Sowerby, G.B. (George B.; Taylor, J.E.; Reeve, B., and Reeve.; Savill, E. and Co.; Spottiswoode & Co.; Vincent Brooks, D.& S. Conchologia Iconica, or, Illustrations of the Shells of Molluscous Animals; Reeve, Brothers: London, 1855; Vol. v.8 (1855).

- Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Hwang, U.W.; Park, J.-K. Taxonomic Review of Korean Siphonaria Species (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Siphonariidae). BDJ 2025, 13, e139388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruthensteiner, B. Redescription and 3D Morphology of Williamia Gussonii (Gastropoda: Siphonariidae). Journal of Molluscan Studies 2006, 72, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, A.N. The Biology of Siphonariid Limpets (Gastropoda: Pulmonata). In Oceanography and marine biology; CRC Press, 2002; pp. 253–322.

- SASAKI, T.; OKUTANI, T. New Genus Nipponacmea (Gastropoda, Lottiidae): A Revision of Japanese Limpets Hitherto Allocated in Notoacmea. Venus (Japanese Journal of Malacology) 1993, 52, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, D.R.; JH, M. Tropical Eastern Pacific Limpets of the Family Acmaeidae (Mollusca, Archaeogastropoda): Generic Criteria and Descriptions of Six New Species from the Mainland and the Galápagos Islands. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 1981, 42, 323–339. [Google Scholar]

- Ponder, W.F.; Creese, R.G. A Revision of the Australian Species of Notoacmea, Collisella and Patelloida (Mollusca : Gastropoda : Acmaeidae). Journal of the Malacological Society of Australia 1980, 4, 167–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paran FJ, Sasaki T, Asakura A, Nakano T. 2025. Description of a new species of the intertidal limpet Patelloida (Patellogastropoda: Lottiidae) from Wakayama and Kochi, Japan. Zool Stud 2025, 64:26.

- Sasaki, T.; Nakano, T. The Southernmost Record of Nipponacmea fuscoviridis (Patellogastropoda : Lottiidae) from Iriomote Island, Okinawa. Venus (Journal of the Malacological Society of Japan) 2007, 66, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Willassen, E.; Williams, A.; Oskars, T. New Observations of the Enigmatic West African Cellana Limpet (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Nacellidae). Marine Biodiversity Records 2016, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family | Species | Shape | Height | Exterior shell | Interior shell | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Riblets | Color | Transparency | |||||

| Nacellidae | C. toreuma | Cap-shaped | Low-domed | Rust yellow | Fine radial ribs + irregular brown bands | Silvery gray, lustrous | Translucent | |

| Lottiidae | L. luchuana | Elongated oval | High-domed | Brown + beige | Irregular dark brown bands | Rust yellow | Slightly transparent | |

| N.fuscoviridis | Cockle-hat shaped | High-domed | Black, black-yellow | Dark black radial stripes | Yellow, lustrous | Slightly transparent | ||

| N. schrenckii | Ovoid | Low-domed | Light yellow-brown | Dark brown spots | Light yellow-brown | Translucent | ||

| P.saccharinoides | Irregularly hexagonal | High-domed | Gray-green |

7 white radial ribs | Light purple | Translucent | ||

| Siphonariidae | S.sp | Broad-ovate | Low-domed | Gray-green |

Fine radial ribs + dark streaks | Reddish-brown margins | Translucent | |

| S. sirius | Elevated, elongated-ovate | Low-domed | Dark brown | Robust radial ribs + fine secondary ribs | Dark to light gradient |

Translucent | ||

| S. japonica | Symmetrically ovate | High-domed | Grayish-brown to brown | Uniform radial ribs + bright “stripe + patch” | Pale brown to off-white | Translucent | ||

| S.atra | Broad-ovate | Low-domed | Dark brown to blackish-brown | Sparse robust radial ribs | Dark coloration | Translucent | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).