Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Relevant Mosquito Vectors in Europe: Native Species and New Arrivals

- Culex pipiens: Known as the common house mosquito, Cx. pipiens is widespread across Europe. It is a primary vector for West Nile virus (WNV) and can also transmit other pathogens such as Usutu virus (USUV) [5].

- Culex univitattus: This is a competent vector for several pathogens, most notably WNV. In Africa and the Middle East, as well as in Portugal, it has been frequently isolated in association with WNV [6,7,8,9]. The species plays a significant role in the enzootic transmission cycle of WNV, maintaining the virus among bird populations and occasionally transmitting it to humans and other mammals.

- Anopheles spp.: Various species of Anopheles mosquitoes are found in Europe, including An. atroparvus and An. plumbeus. These mosquitoes are known vectors for malaria, although the disease is currently not endemic in Europe [10].

- Aedes spp.: Native Aedes species, such as Ae. vexans, are also present in Europe. This species can transmit the nematodes Dirofilaria immitis and transmit arboviruses like Tahyna, Myxoma, and Rift Valley Fever virus (RVFV) [11,12]. Aedes vexans is also possibly competent for WNV [13] and infected individuals have been recently detected also in the UK [14].

- Aedes aegypti: commonly known as the yellow fever mosquito, is a significant vector for several viruses, including yellow fever, dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses (respectively, YFV, DENV, CHIKV, and ZIKV). Historically, this species was established in southern Europe but disappeared during the mid-20th century. However, it has recently reappeared in some regions, including Madeira (Portugal), parts of southern Russia, Georgia, the Canary Islands and Cyprus in 2022, where it is now established [15]. The re-establishment of Ae. aegypti in Europe raises concerns about the potential for autochthonous transmission of the diseases it carries, especially in southern Europe where climatic conditions are favorable. The species thrives in densely populated areas with inadequate water supply and waste management, making urban environments particularly vulnerable [16,17].

- Aedes albopictus: Commonly known as the Asian Tiger mosquito, it is the most invasive mosquito species worldwide including Europe. It has been established in the region since the 1990s and is a known vector for DENV, CHIKV, and ZIKV [18]. First reported in Europe in 1979 in Albania and later in Italy in 1990, the species is now established in in 369 regions across the EU/EEA, including Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain [19,20].

- Aedes japonicus: The Japanese Bush mosquito, Ae. japonicus, is another invasive species that has spread across Europe. It has competence for transmitting various arboviruses, including WNV [21]. Since 2020, Ae. japonicus has continued to spread across Europe [22]. The species was detected for the first time in southern Poland, where both introduced and already established populations were identified. In addition, further establishment was documented across multiple regions, including northern Czechia, Hungary, northern Italy, the Netherlands, Slovakia, northern Spain, and eastern France. These findings highlight the ongoing spread of Ae. japonicus across central and western European regions and underscore the importance of sustained surveillance to monitor its continued expansion [22].

- Aedes koreicus: The Korean bush mosquito is a relatively recent invasive species in Europe and has demonstrated laboratory competence for transmitting Dirofilaria immitis and chikungunya virus (CHIKV) under specific experimental conditions [23]. Since 2020, surveillance data indicate that the species has continued to expand its distribution showing further spread in Hungary and Switzerland [24]. Earlier records confirm that the species is already established in several European countries, including Belgium, where it was first detected in 2008, Italy, Slovenia, and others. Continued monitoring remains essential to assess its public health relevance and to track its evolving European range.

| Genus | Species | Vectorial Capacity | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culex | Cx. pipiens | WNV, USUV, RVFV transmission as the main problem [28,29,30]; vectorial capacity for JEV just in laboratory conditions [3][]; SINV, TAHV present in natural infections [32]; dirofilarial worms [33], avian malaria [34]. | Native for most of urban, peri-urban and rural areas of Europe [35,36] |

|

Cx. univitattus/ Cx. perexiguus |

WNV, RVFV and SINV (originary isolated in this species) were reported linked to this vector [37,38,39]. In the case of the WNV, the species plays a significant role in the enzootic transmission cycle of WNV [38]. | Mainly located in North Africa and southern parts of Europe (Morocco, Algeria, and some areas of the Iberian Peninsula). Absent from most of Europe except parts of the eastern Mediterranean, like Turkey [40]. | |

| Cx. theileri | Vector competence for WNV at laboratory conditions [41], and Dirofilaria immitis [42]. | Present in southwestern Europe, northern Africa, and parts of the Middle East. Isolated occurrences in eastern Europe, absent at most of central and northern Europe [43]. | |

| Aedes | Ae. aegypti | Principal vector of yellow fever, DENV, CHIKV and ZIKV [44], competence for MAYV observed in laboratory conditions with the Ae.albopictus [45]. | Historically established across the Mediterranean region, the Caucasus and the Atlantic archipelagos.. In Europe its current distribution is limited but expanding. [22,43]. |

| Ae. albopictus | Competent for CHIKV, DENV, ZIKA, dirofilariasis, and other 22 arboviruses including YF, RVFV, JEV, SINDV, LACV, OROV, USUV or MAYV [46]. | It is native to Asia and is now widely established across southern and central Europe, as well as large areas of North, Central and South America and the Caribbean [22,43]. | |

| Ae. japonicus | Several studies have shown competence in WNV [48], JEV , LACV [49] and Eastern equine encephalitis virus, CHIKV, DENV [50] and RVFV fever [51,52,53]. | It appeared in 2000 in northern France with subsequent introductions in Belgium, Switzerland and Germany where it is currently established [22,43]. | |

| Ae. koreicus | It is suspected to be a vector for the JEV [54] . It has been linked also to Brugia malayi and Dirofilaria immitis in dogs [55]. | Established in almost all Hungary and northern Italy, at the Crimean peninsula and with firsts reports in Slovenia. Absent in other territories [22,43]. | |

| Ae. cretinus | Evidence for vector competence of Aedes cretinus is very limited and, for arboviruses, absent. | This species is native to the Eastern Mediterranean basin and Black Sea region, like Turkey, Greece or North Macedonia [56,57,58]. | |

| Ae. vexans | It can transmit TAHV and Dirofilaria immitis [59] and a potential vector also or WNV [60] and RVFV [61]. | It is widely distributed across Europe, particularly in Central Europe, Occidental Russia, and the Mediterranean basin [22,43]. |

1.2. Mosquito-Borne Diseases: Recent Outbreaks in Europe and Potential Risks in the near Future

1.3. Global Change and the Spread of Arboviral Diseases

1.4. Insecticide Resistance

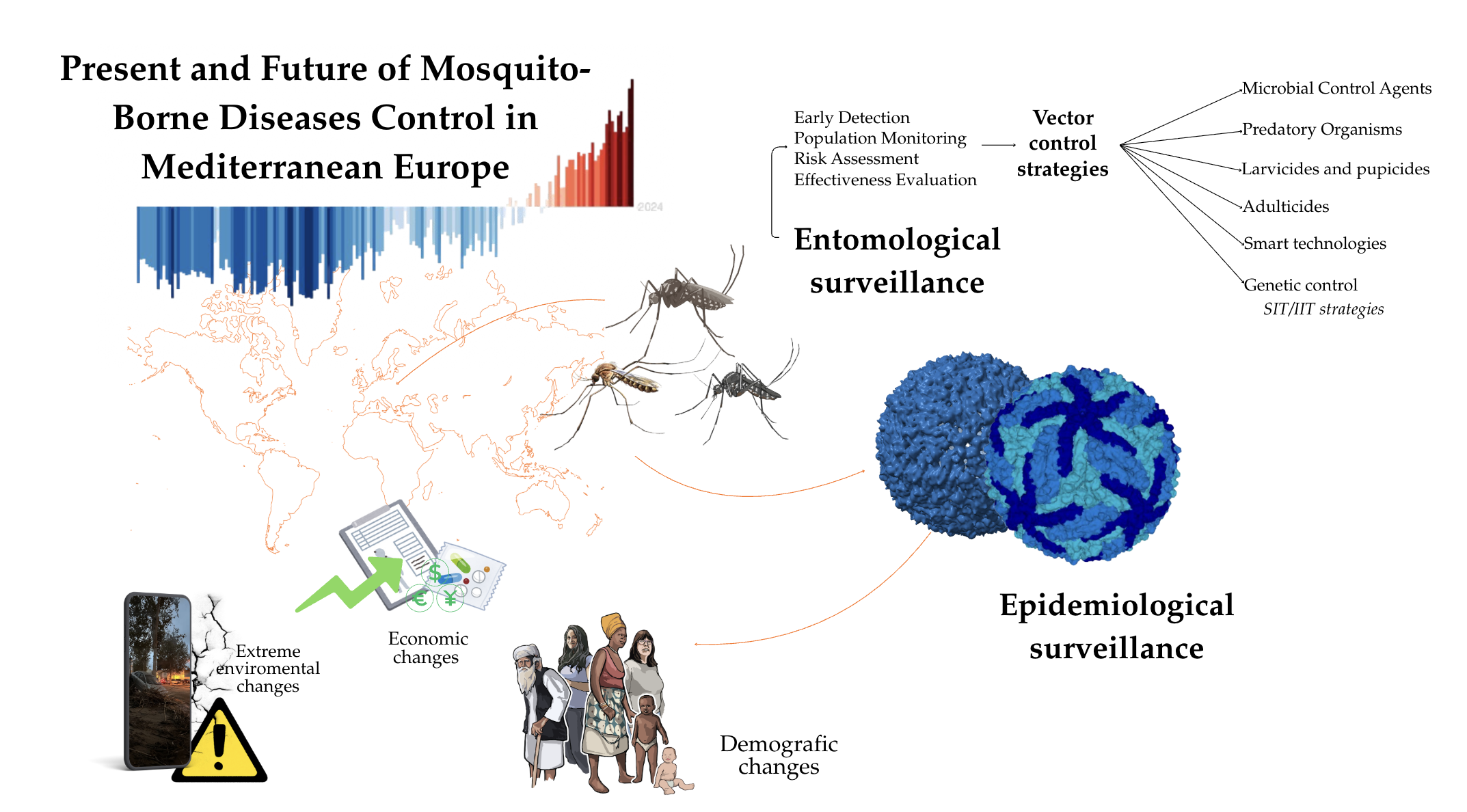

2. Surveillance and Control of Mosquito-Borne Diseases in Mediterranean Europe

2.1. Entomological and Epidemiological Surveillance of Mosquitoes and Mosquito-Borne Pathogens

- Entomological surveillance: aims to detect and examine the population of the invasive and native mosquito species, which are potentially harmful to human and animal health as proven vectors

- Epidemiological surveillance: focuses on existing or threatening outbreaks caused by mosquito-borne pathogens.

- Vectors of pathogens: The primary vectors are mosquitoes of the genus Culex. Therefore, the surveillance program should prioritize areas with favorable climatic and environmental conditions to their breeding and survival.

- Epidemiological reservoirs: Migratory birds serve as the main epidemiological reservoirs, playing a key role in the dissemination of the virus across different geographic regions.

- Risk areas: Wetlands, such as river deltas, marshy areas, or lakes which host abundant migratory birds and mosquitoes, are optimal habitats for the spread of the disease and should be closely monitored.

- Sentinel species: Equines play a prominent role as sentinels, under certain circumstances, since they are more exposed to the bites of the vector transmitting the disease than humans [113].

- − BG-Sentinel Traps: Specifically designed to attract Ae. albopictus using visual cues and attractants like, lactic acid, CO₂.

- − CDC Light Traps: Use CO2 as an attractant, but are less effective for Aedes invasive species.

- − Gravid Traps: Attract females ready to lay eggs, providing insight into potential breeding activity.

- Detection of the Virus in Mosquitoes: Monitoring mosquitoes as vectors.

- Bird Surveillance: Tracking the virus in birds, which are the main source of infection.

- Sentinel Animals: Using sentinel animals, such as chickens, for early detection [121].

- Reservoirs and Dead-End Hosts: Detecting the virus in humans and horses, which act as dead-end hosts [121]

- Detection of Viral Circulation: Identify risk areas where the disease can spread and cause outbreaks.

- Assess the risk of disease emergence from the perspective of animal and public health to provide a timely and effective response.

- Evaluate the need to implement specific control measures and schedule them appropriately [13].

2.2. Traditional Control: Characteristics and Issues

2.2.1. Source Reduction

2.2.2. Mass Trapping

2.2.3. Biological Control

2.2.4. Larvicides and Pupicides

2.2.5. Adulticides

2.3. Genetic Control: Characteristics and Issues

2.3.1. SIT in Europe

2.3.2. Wolbachia and the IIT Approach in Europe

2.4. Smart Technologies Supporting Surveillance and Control

2.5. The Role of Communities in Mosquito Control

2.6. Cost-Effectiveness of Mosquito Control

3. Perspectives and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Copernicus Climate Change Service. (n.d.). Why are Europe and the Arctic heating faster than the rest of the world? . Retrieved December 26, 2025. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/why-are-europe-and-arctic-heating-faster-rest-world.

- European Commission. Commission takes action for clean and competitive automotive sector (Press release No. IP_25_3051). Directorate-General for Communication. 16 December 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_3051.

- Lühken, R.; Brattig, N.; Becker, N. Introduction of invasive mosquito species into Europe and prospects for arbovirus transmission and vector control in an era of globalization. Infectious diseases of poverty 2023, 12(1), 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Guidelines for the surveillance of native mosquitoes in Europe [Public health guidance]. 19 November 2014. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/guidelines-surveillance-native-mosquitoes-europe.

- Balenghien, Thomas; Vazeille, Marie; Grandadam, Marc; Schaffner, Francis; Zeller, Hervé; Reiter, Paul; Sabatier, Philippe; Fouque, Florence; Bicout, Dominique. Vector Competence of Some French Culex and Aedes Mosquitoes for West Nile Virus. Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2008, 8, 589–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, BR; Nasci, RS; Godsey, MS; Savage, HM; Lutwama, JJ; Lanciotti, RS; Peters, CJ. First field evidence for natural vertical transmission of West Nile virus in Culex univittatus complex mosquitoes from Rift Valley province, Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000, 62(2), 240–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, A; Almeida, AP; Galão, RP; Parreira, R; Piedade, J; Rodrigues, JC; Sousaand, CA; Novo, MT. West Nile virus in Southern Portugal, 2004. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2005, 5, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, PG; Galão, RP; Sousa, CA; Novo, MT; Parreira, R; Pinto, J; Piedade, J; Esteves, A. Potential mosquito vectors of arboviruses in Portugal: species, distribution, abundance and West Nile infection. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2008, 102(8), 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mixão, V; Bravo Barriga, D; Parreira, R; Novo, MT; Sousa, CA; Frontera, E; Venter, M; Braack, L; Almeida, AP. Comparative morphological and molecular analysis confirms the presence of the West Nile virus mosquito vector, Culex univittatus, in the Iberian Peninsula. Parasit Vectors 2016, 9(1), 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffner, F; Thiéry, I; Kaufmann, C; Zettor, A; Lengeler, C; Mathis, A; Bourgouin, C. Anopheles plumbeus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Europe: a mere nuisance mosquito or potential malaria vector? Malar J 2012, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mravcová, K.; Camp, J. V.; Hubálek, Z.; Šikutová, S.; Vaux, A. G. C.; Medlock, J. M.; Rudolf, I. Ťahyňa virus-A widespread, but neglected mosquito-borne virus in Europe. Zoonoses and public health 2023, 70(5), 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnberg, L.; Talavera, S.; Aranda, C.; et al. Field-captured Aedes vexans (Meigen, 1830) is a competent vector for Rift Valley fever phlebovirus in Europe. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. F.; Main, A. J.; Ferrandino, F. J. Horizontal and vertical transmission of West Nile virus by Aedes vexans (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2020, 57, 1614–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlock, J. M.; Vaux, A. G.; Cull, B.; Schaffner, F.; Gillingham, E.; Pfluger, V.; Leach, S. Detection of the invasive mosquito species Aedes albopictus in southern England. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2017, 17(2), 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, M. I.; Notarides, G.; Meletiou, S.; Patsoula, E.; Kavran, M.; Michaelakis, A.; Bellini, R.; Toumazi, T.; Bouyer, J.; Petrić, D. Two invasions at once: update on the introduction of the invasive species Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Cyprus - a call for action in Europe. Deux invasions à la fois: le point sur l'introduction des espèces envahissantes Aedes aegypti et Aedes albopictus à Chypre – un appel à l'action en Europe. Parasite (Paris, France) 2023, 30, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A. P. G.; Freitas, F. B.; Novo, M. T.; Sousa, C. A.; Rodrigues, J. C.; Alves, R.; Esteves, A. Mosquito surveys and West Nile virus screening in two different areas of Southern Portugal, 2004–2007. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2010, 10(7), 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, M. U. G.; Reiner, R. C., Jr.; Brady, O. J.; Messina, J. P.; Gilbert, M.; Pigott, D. M.; Yi, D.; Johnson, K.; Earl, L.; Marczak, L. B.; Shirude, S.; Davis Weaver, N.; Bisanzio, D.; Perkins, T. A.; Lai, S.; Lu, X.; Jones, P.; Coelho, G. E.; Carvalho, R. G.; Van Bortel, W.; Golding, N. Past and future spread of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Nature microbiology 2019, 4(5), 854–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seixas, G.; Salgueiro, P.; Bronzato-Badial, A.; et al. Origin and expansion of the mosquito Aedes aegypti in Madeira Island (Portugal). Sci Rep 2019, 9, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellini, R; Michaelakis, A; Petrić, D; Schaffner, F; Alten, B; Angelini, P; Aranda, C; Becker, N; Carrieri, M; Di Luca, M; Fălcuţă, E; Flacio, E; Klobučar, A; Lagneau, C; Merdić, E; Mikov, O; Pajovic, I; Papachristos, D; Sousa, CA; Stroo, A; Toma, L; Vasquez, MI; Velo, E; Venturelli, C; Zgomba, M. Practical management plan for invasive mosquito species in Europe: I. Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus). Travel Med Infect Dis 2020, 35, 101691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ECDC. 2023. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/aedes-albopictus-current-known-distribution-october-2023 (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Aedes albopictus – current known distribution: June 2025 . 1 July 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/aedes-albopictus-current-known-distribution-june-2025.

- Koban, M. B.; Kampen, H.; Scheuch, D. E.; Frueh, L.; Kuhlisch, C.; Janssen, N.; Steidle, J. L. M.; Schaub, G. A.; Werner, D. The Asian bush mosquito Aedes japonicus japonicus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Europe, 17 years after its first detection, with a focus on monitoring methods. Parasites & vectors 2019, 12(1), 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; European Food Safety Authority. Mosquito maps. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/disease-vectors/surveillance-and-disease-data/mosquito-maps.

- Montarsi, F.; Rosso, F.; Arnoldi, D.; et al. First report of the blood-feeding pattern in Aedes koreicus, a new invasive species in Europe. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 15751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurucz, K.; Zeghbib, S.; Arnoldi, D.; Marini, G.; Manica, M.; Michelutti, A.; Montarsi, F.; Deblauwe, I.; Van Bortel, W.; Smitz, N.; Pfitzner, W. P.; Czajka, C.; Jöst, A.; Kalan, K.; Šušnjar, J.; Ivović, V.; Kuczmog, A.; Lanszki, Z.; Tóth, G. E.; Somogyi, B. A.; Kemenesi, G. Aedes koreicus, a vector on the rise: Pan-European genetic patterns, mitochondrial and draft genome sequencing. PloS one 2022, 17(8), e0269880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrich. 2025.

- Rezza, G.; Nicoletti, L.; Angelini, R.; Romi, R.; Finarelli, A. C.; Panning, M.; Cordioli, P.; Fortuna, C.; Boros, S.; Magurano, F.; Silvi, G.; Angelini, P.; Dottori, M.; Ciufolini, M. G.; Majori, G. C.; Cassone, A.; CHIKV study group. Infection with chikungunya virus in Italy: an outbreak in a temperate region. Lancet (London, England) 2007, 370(9602), 1840–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatta, M.; Brichler, S.; Vindrios, W.; Melica, G.; Gallien, S. Autochthonous Dengue Outbreak, Paris Region, France, September-October 2023. Emerging infectious diseases 2023, 29(12), 2538–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzoli, A.; Bolzoni, L.; Chadwick, E. A.; Capelli, G.; Montarsi, F.; Grisenti, M.; de la Puente, J. M.; Muñoz, J.; Figuerola, J.; Soriguer, R.; Anfora, G.; Di Luca, M.; Rosà, R. Understanding West Nile virus ecology in Europe: Culex pipiens host feeding preference in a hotspot of virus emergence. Parasites & vectors 2015, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilibic-Cavlek, T; Savic, V; Petrovic, T; Toplak, I; Barbic, L; Petric, D; et al. Emerging trends in the epidemiology of West Nile and Usutu virus infections in southern Europe. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2019 2019-December-06, 6, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pages, N; Huber, K; Cipriani, M; Chevallier, V; Conraths, FJ; Goffredo, M; et al. Scientific review on mosquitoes and mosquito-borne diseases. EFSA Supporting Publications 2009, 6(8), 7E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japanese encephalitis.

- Hubálek, Z. Mosquito-borne viruses in Europe. Parasitol Res. 2008 2008/12/01, 103(1), 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo-Barriga, D; Parreira, R; Almeida, APG; Calado, M; Blanco-Ciudad, J; Serrano-Aguilera, FJ; et al. Culex pipiens as a potential vector for transmission of Dirofilaria immitis and other unclassified Filarioidea in Southwest Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2016 2016/06/15/, 223, 173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalubin, F; Delédevant, A; Glaizot, O; Christe, P. Temporal changes in mosquito abundance (Culex pipiens), avian malaria prevalence and lineage composition. Parasites & Vectors 2013 2013/10/25, 6(1), 307. [Google Scholar]

- Haba, Y; McBride, L. Origin and status of Culex pipiens mosquito ecotypes. Curr Biol 2022, 32(5), R237–R246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marcolin, L.; Zardini, A.; Longo, E.; Caputo, B.; Poletti, P.; Di Marco, M. Mapping the habitat suitability of Culex pipiens in Europe using ensemble bioclimatic modelling. Journal of Biogeography 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, R.; Kioko, E.; Lutomiah, J.; Warigia, M.; Ochieng, C.; O'Guinn, M.; Lee, J. S.; Koka, H.; Godsey, M.; Hoel, D.; Hanafi, H.; Miller, B.; Schnabel, D.; Breiman, R. F.; Richardson, J. Rift Valley fever virus epidemic in Kenya, 2006/2007: the entomologic investigations. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2010, 83(2 Suppl), 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, B. M.; Jupp, P. G.; Dos Santos, I.; Meenehan, G. M. Epidemics of West Nile and Sindbis viruses in South Africa with Culex (Culex) univittatus Theobald as vector. 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Mixão, V; Bravo Barriga, D; Parreira, R; Novo, MT; Sousa, CA; Frontera, E; Venter, M; Braack, L; Almeida, AP. Comparative morphological and molecular analysis confirms the presence of the West Nile virus mosquito vector, Culex univittatus, in the Iberian Peninsula. Parasit Vectors 2016, 9(1), 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; European Food Safety Authority. Culex perexiguus/univittatus – Current known distribution: October 2023. ECDC. 17 November 2023. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/culex-perexiguusunivittatus-current-known-distribution-october-2023.

- Burgas-Pau, A; Gardela, J; Aranda, C; Verdún, M; Rivas, R; Pujol, N; Figuerola, J; Busquets, N. Laboratory evidence on the vector competence of European field-captured Culex theileri for circulating West Nile virus lineages 1 and 2. Parasit Vectors 2025, 18(1), 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ferreira, CA; de Pinho Mixão, V; Novo, MT; Calado, MM; Gonçalves, LA; Belo, SM; de Almeida, AP. First molecular identification of mosquito vectors of Dirofilaria immitis in continental Portugal. Parasit Vectors 2015, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Becker, N.; Petric, D.; Zgomba, M.; Boase, C.; Madon, M.; Dahl, C.; Kaiser, A. Mosquitoes and their control; Springer Science & Business Media, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Neto, J. A., Powell, J. R., & Bonizzoni, M. (2019). Aedes aegypti vector competence studies: A review. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases, 67, 191–209. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T. N.; Carvalho, F. D.; De Mendonça, S. F.; Rocha, M. N.; Moreira, L. A. Vector competence of Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes for Mayaro virus. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2020, 14(4), e0007518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-dos-Santos, T.; Roiz, D.; Lourenço-de-Oliveira, R.; Paupy, C. A systematic review: Is Aedes albopictus an efficient bridge vector for zoonotic arboviruses? Pathogens 2020, 9(4), 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardelis, MR; Turell, MJ. Ochlerotatus j. japonicus in Frederick County, Maryland: discovery, distribution, and vector competence for West Nile virus. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2001, 17(2), 137–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sardelis, MR; Turell, MJ; Andre, RG. Laboratory transmission of La Crosse virus by Ochlerotatus j. japonicus (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol 2002, 39(4), 635–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardelis, MR; Dohm, DJ; Pagac, B; Andre, RG; Turell, MJ. Experimental transmission of eastern equine encephalitis virus by Ochlerotatus j. japonicus (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol 2002, 39(3), 480–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, F; Vazeille, M; Kaufmann, C; Failloux, A; Mathis, A. Vector competence of Aedes japonicus for chikungunya and dengue viruses. Eu Mosq Bull. 2011, 29, 141–2. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner, F; Kaufmann, C; Hegglin, D; Mathis, A. The invasive mosquito Aedes japonicus in Central Europe. Med Vet Entomol 2009, 23(4), 448–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turell, MJ; Byrd, BD; Harrison, BA. Potential for populations of Aedes j. japonicus to transmit Rift Valley fever virus in the USA. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2013, 29(2), 133–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, JA. Some ecological aspects of the problem of arthropod-borne Animal viruses in the Western Pacific and South-East Asia regions. Bull World Health Organ. 1964, 30, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shestakov, VI; Mikheeva, AI. Study of vectors of Japanese encephalitis in the Maritime Territory. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 1966, 35(5), 545–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Korean Centre for Disease Control. Elimination of Lymphatic filariasis in Korea. National document for certification; National Institute of Health. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, Ministry of Health and Welfare: Republic of Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Giatropoulos, AK; Michaelakis, AN; Koliopoulos, GT; Pontikakos, CM. Records of Aedes albopictus and Aedes cretinus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Greece from 2009 to 2011. Hell Plant Prot J 2012, 5, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Alten, B; Bellini, R; Caglar, SS; Simsek, FM; Kaynas, S. Species composition and seasonal dynamics of mosquitoes in the Belek region of Turkey. J Vector Ecol 2000, 25, 146–54. [Google Scholar]

- Şimşek, F. M.; Yavaşoğlu, S. İ. Distribution of Aedes (Stegomyia) cretinus in Türkiye. Turkish Journal of Parasitology 2023, 47(2), 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivănescu, L.; Mîndru, R.; Bodale, I.; Apopei, G. V.; Andronic, L.; Hristodorescu, S.; Azoicăi, D.; Miron, L. Circulation of Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens Species in Mosquitoes in the Southeastern Part of Romania, Under the Influence of Climate Change. Life (Basel, Switzerland) 2025, 15(10), 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, R. C.; Abbott, A. J.; Jones, B. P.; Gardner, B. L.; Gonzalez, E.; Ionescu, A. M.; Jagdev, M.; Jenkins, A.; Santos, M.; Seilern-Macpherson, K.; Hanmer, H. J.; Robinson, R. A.; Vaux, A. G.; Johnson, N.; Cunningham, A. A.; Lawson, B.; Medlock, J. M.; Folly, A. J. Detection of West Nile virus via retrospective mosquito arbovirus surveillance, United Kingdom, 2025. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 2025, 30(28), 2500401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndiaye, E.H.; Fall, G.; Gaye, A.; et al. Vector competence of Aedes vexans (Meigen), Culex poicilipes (Theobald) and Cx. quinquefasciatus Say from Senegal for West and East African lineages of Rift Valley fever virus. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman, M. G.; Harris, E. Dengue. The Lancet 2015, 385(9966), 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Ching-Yen; Lee, Ing-Kit; Lee, Chen-Hsiang; Yang, Kuender D.; Liu, Jien-Wei. Comparisons of dengue illness classified based on the 1997 and 2009 World Health Organization dengue classification schemes. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection 2013, Volume 46(Issue 4), 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Fabrice; Caumes, Eric; Jelinek, Tomas; Lopez-Velez, Rogelio; Steffen, Robert; Chen, Lin H. Chikungunya: risks for travellers. Journal of Travel Medicine 2023, Volume 30(Issue 2), taad008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Dispersal of Dengue through Air Travel: Importation Risk for Europe Semenza JC, Sudre B, Miniota J, Rossi M, Hu W, et al. (2014) International Dispersal of Dengue through Air Travel: Importation Risk for Europe. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 8(12): e3278. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Historical data on local transmission in the EU/EEA of chikungunya virus disease . ECDC. 16 July 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/infectious-disease-topics/chikungunya-virus-disease/surveillance-and-updates/local-transmission-previous-years.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Chikungunya virus disease worldwide overview (Chikungunya monthly) . ECDC. 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/chikungunya-monthly.

- Mercier, A.; Obadia, T.; Carraretto, D.; et al. Impact of temperature on dengue and chikungunya transmission by the mosquito Aedes albopictus. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radici, A.; Hammami, P.; Cannet, A.; et al. Aedes albopictus Is Rapidly Invading Its Climatic Niche in France: Wider Implications for Biting Nuisance and Arbovirus Control in Western Europe. Global Change Biology 2025, 31(no. 8), e70414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, J. C.; Sudre, B.; Miniota, J.; Rossi, M.; Hu, W.; Kossowsky, D.; Suk, J. E.; Van Bortel, W.; Khan, K. International dispersal of dengue through air travel: Importation risk for Europe. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2014, 8(12), Article e3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdain, F.; Roiz, D.; de Valk, H.; Noël, H.; L’Ambert, G.; Franke, F.; Paty, M.-C.; Guinard, A.; Desenclos, J.-C.; Roche, B. From importation to autochthonous transmission: Drivers of chikungunya and dengue emergence in a temperate area . PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2020, 14(5), e0008320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giron, S; Franke, F; Decoppet, A; Cadiou, B; Travaglini, T; Thirion, L; Durand, G; Jeannin, C; L'Ambert, G; Grard, G; Noël, H; Fournet, N; Auzet-Caillaud, M; Zandotti, C; Aboukaïs, S; Chaud, P; Guedj, S; Hamouda, L; Naudot, X; Ovize, A; Lazarus, C; de Valk, H; Paty, MC; Leparc-Goffart, I. Vector-borne transmission of Zika virus in Europe, southern France, August 2019. Euro Surveill 2019, 24(45), 1900655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lequime, S; Dehecq, J-S; Matheus, S; de Laval, F; Almeras, L; Briolant, S; et al. Modeling intra-mosquito dynamics of Zika virus and its dose-dependence confirms the low epidemic potential of Aedes albopictus. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16(12), e1009068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, E; Cecere, JG; Iapaolo, F; Di Gennaro, A; Sacchi, M; Savini, G; Spina, F; Monaco, F. West Nile and Usutu Virus Introduction via Migratory Birds: A Retrospective Analysis in Italy. Viruses 2022, 14(2), 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Petrović, T.; Šekler, M.; Petrić, D.; Vidanović, D.; Debeljak, Z.; Lazić, G.; Lupulović, D.; Kavran, M.; Samojlović, M.; Ignjatović Ćupina, A.; Tešović, B. Intensive West Nile virus circulation in Serbia in 2018—results of integrated surveillance program. Pathogens 2021, 10(10), 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Historical data on local transmission in Europe for West Nile virus . ECDC. 10 June 2024. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/west-nile-fever/surveillance-and-disease-data/historical.

- Pisani, G.; Cristiano, K.; Pupella, S.; Liumbruno, G. M. West Nile virus in Europe and safety of blood transfusion. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy 2016, 43(3), 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscher, C; Patzina-Mehling, C; Melchert, J; Graff, SL; McFarland, SE; Hieke, C; Kopp, A; Prasser, A; Tonn, T; Schmidt, M; Isner, C; Drosten, C; Werber, D; Corman, VM; Junglen, S. Ecological and clinical evidence of the establishment of West Nile virus in a large urban area in Europe, Berlin, Germany, 2021 to 2022. Euro Surveill 2023, 28(48), 2300258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santé publique France. Chikungunya, dengue, Zika et West Nile en France hexagonale: Bulletin de la surveillance renforcée du 26 novembre 2025 . 26 November 2025. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/maladies-et-traumatismes/maladies-a-transmission-vectorielle/chikungunya/documents/bulletin-national/chikungunya-dengue-zika-et-west-nile-en-france-hexagonale.-bulletin-de-la-surveillance-renforcee-du-26-novembre-2025.

- Lu, L; Zhang, F; Oude Munnink, BB; Munger, E; Sikkema, RS; Pappa, S; et al. West Nile virus spread in Europe: Phylogeographic pattern analysis and key drivers. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20(1), e1011880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erazo, D.; Grant, L.; Ghisbain, G.; et al. Contribution of climate change to the spatial expansion of West Nile virus in Europe. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y; Wang, M; Huang, M; Zhao, J. Innovative strategies and challenges mosquito-borne disease control amidst climate change. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1488106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, J. C.; Suk, J. E. Vector-borne diseases and climate change: A European perspective. FEMS Microbiology Letters 365 2018, fnx244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsmeier, C.; Bonnamour, A.; Garnas, J.R.; et al. Temporal dynamics and global flows of insect invasions in an era of globalization. Nat. Rev. Biodivers. 2025, 1, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, F.; Brunetti, R.; Buonanno, M.; De Martinis, C.; Cardillo, L.; Fenizia, P.; Anatriello, A.; Rofrano, G.; D’Auria, L.J.; Fusco, G. Temporal Analysis of Climate Change Impact on the Spread and Prevalence of Vector-Borne Diseases in Campania (2018–2023). Microorganisms 2025, 13, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyamba, A.; Chretien, J. P.; Britch, S. C.; Soebiyanto, R. P.; Small, J. L.; Jepsen, R.; Forshey, B. M.; Sanchez, J. L.; Smith, R. D.; Harris, R.; Tucker, C. J.; Karesh, W. B.; Linthicum, K. J. Global Disease Outbreaks Associated with the 2015-2016 El Niño Event. Scientific reports 2019, 9(1), 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Susong, K. M.; Chen, Y.; Joshi, K.; Campbell, A. M.; Lim, A.; Lin, Q.; Ma, Z.; Wei, Y.; Yang, Y.; Sun, C.; Feng, J.; He, Q.; Wang, Z.; Cazelles, B.; Guo, Y.; Liu, K.; Tian, H. Rising dengue risk with increasing El Niño-Southern Oscillation amplitude and teleconnections. Nature communications 2025, 16(1), 8629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, SJ; Carlson, CJ; Mordecai, EA; Johnson, LR. Global expansion and redistribution of Aedes-borne virus transmission risk with climate change. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13(3), e0007213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Khan, Z.; Das, D.; et al. Thermal influence on development and morphological traits of Aedes aegypti in central India and its relevance to climate change. Parasites Vectors 2025, 18, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Ya-Zhou; Ding, Yike; Wang, Xueli; Zou, Zhen; Raikhel, Alexander S. E93 confers steroid hormone responsiveness of digestive enzymes to promote blood meal digestion in the midgut of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2021, Volume 134, 103580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balatsos, G.; Beleri, S.; Tegos, N.; Bisia, M.; Karras, V.; Zavitsanou, E.; Papachristos, D.P.; Papadopoulos, N.T.; Michaelakis, A.; Patsoula, E. Overwintering West Nile virus in active Culex pipiens mosquito populations in Greece. Parasites & Vectors 2024, 17(1), 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagopoulou, A.; Tegos, N.; Beleri, S.; Mpimpa, A.; Balatsos, G.; Michaelakis, A.; Hadjichristodoulou, C.; Patsoula, E. Molecular detection of Usutu virus in pools of Culex pipiens mosquitoes in Greece. Acta Tropica 2024, 258, 107330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coalson, J.E.; Anderson, E.J.; Santos, E.M.; Garcia, V.M.; Romine, J.K.; Luzingu, J.K.; Dominguez, B.; Richard, D.M.; Little, A.C.; Hayden, M.H.; Ernst, K.C. The complex epidemiological relationship between flooding events and human outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases: a scoping review. Environmental health perspectives 2021, 129(9), 096002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treskova, M.; Semenza, J.C.; Arnés-Sanz, C.; Al-Ahdal, T.; Markotter, W.; Sikkema, R.S.; Rocklöv, J. Climate change and pandemics: a call for action. The Lancet Planetary Health 2025, 9(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couper, L. I.; Dodge, T. O.; Hemker, J. A.; Kim, B. Y.; Exposito-Alonso, M.; Breme, R. B.; Mordecai, E. A.; Bitter, M. C. Evolutionary adaptation under climate change: Aedes sp. demonstrates potential to adapt to warming. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2025, 122(2), e2418199122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolimenakis, A.; Heinz, S.; Wilson, M.L.; Winkler, V.; Yakob, L.; Michaelakis, A.; Papachristos, D.; Richardson, C.; Horstick, O. The role of urbanisation in the spread of Aedes mosquitoes and the diseases they transmit—A systematic review. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2021, 15(9), e0009631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The role of urbanisation in the spread of Aedes mosquitoes and the diseases they transmit—A systematic review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0009631.

- van den Berg, H.; da Silva Bezerra, H.S.; Al-Eryani, S.; et al. Recent trends in global insecticide use for disease vector control and potential implications for resistance management. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 23867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achee, N. L.; Grieco, J. P.; Vatandoost, H.; Seixas, G.; Pinto, J.; Ching-Ng, L.; Martins, A. J.; Juntarajumnong, W.; Corbel, V.; Gouagna, C.; David, J.-P.; Logan, J. G.; Orsborne, J.; Vontas, J. Alternative strategies for mosquito-borne arbovirus control. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2019, 13(1), Article e0006822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaska, S.; Fotakis, E. A.; Kioulos, I.; Grigoraki, L.; Mpellou, S.; Chaskopoulou, A.; Vontas, J. Bioassay and molecular monitoring of insecticide resistance status in Aedes albopictus populations from Greece, to support evidence-based vector control. Parasites & Vectors 13 2020, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancredi, A.; Papandrea, D.; Marconcini, M.; Carballar-Lejarazu, R.; Casas-Martinez, M.; Lo, E.; Chen, X.-G.; Malacrida, A. R.; Bonizzoni, M. Tracing temporal and geographic distribution of resistance to pyrethroids in the arboviral vector Aedes albopictus. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2020, 14(6), Article e0008350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, V.; Caputo, B.; Valadas, V.; et al. Geographic distribution of the V1016G knockdown resistance mutation in Aedes albopictus: a warning bell for Europe. Parasites Vectors 2022, 15, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, S.; Caputo, B.; Tsunoda, T.; Cuong, T. C.; Maekawa, Y.; Lam-Phua, S. G.; Pichler, V.; Itokawa, K.; Murota, K.; Komagata, O.; Yoshida, C.; Chung, H.-H.; Bellini, R.; Tsuda, Y.; Teng, H.-J.; Filho, J. L. de L.; Alves, L. C.; Ng, L. C.; Minakawa, N.; Tomita, T. First detection of a Vssc allele V1016G conferring a high level of insecticide resistance in Aedes albopictus collected from Europe (Italy) and Asia (Vietnam), 2016: A new emerging threat to controlling arboviral diseases. Euro Surveillance 2019, 24(5), 1700847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, G.; Grigoraki, L.; Weetman, D.; Vicente, J. L.; Silva, A. C.; Pinto, J.; Vontas, J.; Sousa, C. A. Insecticide resistance is mediated by multiple mechanisms in recently introduced Aedes aegypti from Madeira Island (Portugal). PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2017, 11(7), e0005799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioulos, I.; Kampouraki, A.; Morou, E.; Skavdis, G.; Vontas, J. Insecticide resistance status in the major West Nile virus vector Culex pipiens from Greece. Pest Management Science 2013, 70(4), 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoraki, L.; Puggioli, A.; Mavridis, K.; et al. Striking diflubenzuron resistance in Culex pipiens, the prime vector of West Nile Virus. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiba, R.; Varga, Z.; Pásztor, D.; et al. Consequences of insecticide overuse in Hungary: assessment of pyrethroid resistance in Culex pipiens and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Parasites Vectors 2025, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, S.; Vanslembrouck, A.; Kramer, I.M.; et al. Phenotypic insecticide resistance status of the Culex pipiens complex: a European perspective. Parasites Vectors 2022, 15, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portwood, N. M.; Schwan, T.; Pugglioli, A.; Becker, N.; Ingham, V. A. Assessment of pyrethroid resistance and Wolbachia prevalence in pathogen-related mosquito species from southwest Germany . Journal of the European Mosquito Control Association 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoraki, L.; Puggioli, A.; Mavridis, K.; et al. Striking diflubenzuron resistance in Culex pipiens, the prime vector of West Nile Virus. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 112 Fotakis, E. A.; Mavridis, K.; Kampouraki, A.; Balaska, S.; Tanti, F.; Vlachos, G.; Gewehr, S.; Mourelatos, S.; Papadakis, A.; Kavalou, M.; Nikolakakis, D.; Moisaki, M.; Kampanis, N.; Loumpounis, M.; Vontas, J. Mosquito population structure, pathogen surveillance and insecticide resistance monitoring in urban regions of Crete, Greece. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2022, 16(2), e0010186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichler, V.; Valadas, V.; Akiner, M.M.; Balatsos, G.; Barceló, C.; Borg, M.L.; Bouyer, J.; Bravo-Barriga, D.; Bueno, R.; Caputo, B.; Collantes, F. Tracking pyrethroid resistance in arbovirus mosquito vectors: mutations I1532T and F1534C in Aedes albopictus across Europe. Parasites & Vectors 2025, 18(1), 506. [Google Scholar]

- Gothe, LMR; Ganzenberg, S; Ziegler, U; Obiegala, A; Lohmann, KL; Sieg, M; Vahlenkamp, TW; Groschup, MH; Hörügel, U; Pfeffer, M. Horses as Sentinels for the Circulation of Flaviviruses in Eastern-Central Germany. Viruses 2023, 15(5), 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- ECDC. Surveillance of West Nile Virus infections in Europe. Weekly reports. 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/west-nile-fever/surveillance-and-disease-data/disease-data-ecdc (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Schaffner, F.; Mathis, A. Dengue and dengue vectors in the WHO European region: past, present, and scenarios for the future. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2014, 14(12), 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Organisation for Animal Health; International Union for Conservation of Nature. Memorandum of Understanding between the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) (Administrative Working Document 91GS/Adm-09/En). WOAH. March 2024. Available online: https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2024/04/91gs-2024-wd-adm-09-mou-iucn-en.pdf.

- Becker, N.; Langentepe-Kong, S. M.; Tokatlian Rodriguez, A.; Oo, T. T.; Reichle, D.; Lühken, R.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Lüthy, P.; Puggioli, A.; Bellini, R. Integrated control of Aedes albopictus in Southwest Germany supported by the Sterile Insect Technique. Parasites & vectors 2022, 15(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrieri, M.; Bellini, R.; Maccaferri, S.; Gallo, L.; Maini, S.; Celli, G. Tolerance thresholds for Aedes albopictus and Aedes caspius in Italian urban areas. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 2008, 24(3), 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eritja, R.; Escosa, R.; Lucientes, J.; et al. Worldwide invasion of vector mosquitoes: present European distribution and challenges for Spain. Biological Invasions 2005, 7, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolimenakis, A.; Bithas, K.; Richardson, C.; Latinopoulos, D.; Baka, A.; Vakali, A.; Hadjichristodoulou, C.; Mourelatos, S.; Kalaitzopoulou, S.; Gewehr, S.; Michaelakis, A. Economic appraisal of the public control and prevention strategy against the 2010 West Nile virus outbreak in Central Macedonia, Greece. Public health 2016, 131, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrić, Dušan; Petrović, Tamaš; Hrnjaković Cvjetković, Ivana; Zgomba, Marija; Milošević, Vesna; Lazić, Gospava; Ignjatović Ćupina, Aleksandra; Lupulović, Diana; Lazić, Sava; Dondur, Dragan; Vaselek, Slavica; Živulj, Aleksandar; Kisin, Bratislav; Molnar, Tibor; Janku, Djordje; Pudar, Dubravka; Radovanov, Jelena; Kavran, Mihaela; Kovačević, Gordana; Plavšić, Budimir; Galović, Aleksandra Jovanović; Vidić, Milan; Ilić, Svetlana; Petrić, Mina. West Nile virus ‘circulation’ in Vojvodina, Serbia: Mosquito, bird, horse and human surveillance. Molecular and Cellular Probes 2017, Volume 31, Pages 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. EpiCentro . 2025. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/.

- Santé publique France. Report on human surveillance of West Nile virus in metropolitan France, 2024 . Santé publique France. 15 May 2025. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/content/download/721963/4671136/version/1/file/Bilan-surveillance-virus-West-Nile-France-hexagonale-2024.pdf.

- Osório, H. C.; Zé-Zé, L.; Amaro, F.; Alves, M. J. Mosquito Surveillance for Prevention and Control of Emerging Mosquito-Borne Diseases in Portugal — 2008–2014. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2014, 11(11), 11583–11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, S.; Duarte, A.; Boinas, F.; Costa Osório, H. A DNA barcode reference library of Portuguese mosquitoes. Zoonoses and Public Health 2021, 68(8), 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, J.; Pinotti, F.; Nakase, T.; Giovanetti, M.; Obolski, U. Letter to the editor: Atypical weather is associated with the 2022 early start of West Nile virus transmission in Italy. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 2022, 27(34), 2200662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenço, J.; Barros, S.C.; Zé-Zé, L.; et al. West Nile virus transmission potential in Portugal. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroco, D.; Parreira, R.; Abade dos Santos, F.; Lopes, Â.; Simões, F.; Orge, L.; Seabra, S. G.; Fagulha, T.; Brazio, E.; Henriques, A. M. Tracking the pathways of West Nile virus: Phylogenetic and phylogeographic analysis of a 2024 isolate from Portugal. Microorganisms 2025, 13(3), 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, MA; Barceló, C; Muriel, R; Rodríguez, JJ; Rodríguez, E; Figuerola, J; Bravo-Barriga, D. Rapid-Response Vector Surveillance and Emergency Control During the Largest West Nile Virus Outbreak in Southern Spain. Insects 2025, 16(11), 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osório, H. C.; Zé-Zé, L.; Neto, M.; Silva, S.; Marques, F.; Silva, A. S.; Alves, M. J. Detection of the invasive mosquito species Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Portugal . International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15(4), 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osório, H. C.; Rocha, J.; Roquette, R.; Guerreiro, N. M.; Zé-Zé, L.; Amaro, F.; Silva, M.; Alves, M. J. Seasonal dynamics and spatial distribution of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in a temperate region in Europe, southern Portugal. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(19), Article 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zé-Zé, L.; Freitas, I. C.; Silva, M.; Soares, P.; Alves, M. J.; Osório, H. C. The spread of the invasive mosquito Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Portugal: a first genetic analysis . Parasites & Vectors 17 2024, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau-Pujol, B.; Moreira, A.; Vieira Martins, J.; Costa Osório, H.; Ribeiro, L.; Dinis, A.; Sousa, C. Rapid response Task Force: addressing the detection of Aedes albopictus in Lisbon, Portugal. European Journal of Public Health 34 2024, Suppl. 3, ckae144.279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M. Á.; Barceló, C.; Arnoldi, D.; Augsten, X.; Bakran-Lebl, K.; Balatsos, G.; Bengoa, M.; Bindler, P.; Boršová, K.; Bourquia, M.; Bravo-Barriga, D.; Čabanová, V.; Caputo, B.; Christou, M.; Delacour, S.; Eritja, R.; Fassi-Fihri, O.; Ferraguti, M.; Flacio, E.; Frontera, E.; Consortium AIM-COST/AIM-Surv. AIMSurv: First pan-European harmonized surveillance of Aedes invasive mosquito species of relevance for human vector-borne diseases. GigaByte (Hong Kong, China) 2022, gigabyte57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patsoula, E.; Vakali, A.; Balatsos, G.; Pervanidou, D.; Beleri, S.; Tegos, N.; Baka, A.; Spanakos, G.; Georgakopoulou, T.; Tserkezou, P.; Van Bortel, W. West Nile virus circulation in mosquitoes in Greece (2010–2013). BioMed Research International 2016, 2016(1), 2450682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervanidou, D.; Kefaloudi, C.N.; Vakali, A.; Tsakalidou, O.; Karatheodorou, M.; Tsioka, K.; Evangelidou, M.; Mellou, K.; Pappa, S.; Stoikou, K.; Bakaloudi, V. The 2022 West Nile virus season in Greece; a quite intense season. Viruses 2023, 15(7), 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pervanidou, D.; Vakali, A.; Georgakopoulou, T.; Panagiotopoulos, T.; Patsoula, E.; Koliopoulos, G.; Politis, C.; Stamoulis, K.; Gavana, E.; Pappa, S.; Mavrouli, M. West Nile virus in humans, Greece, 2018: The largest seasonal number of cases, 9 years after its emergence in the country. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25(32), 1900543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilianakis, N.I.; Syrris, V.; Petroliagkis, T.; Pärt, P.; Gewehr, S.; Kalaitzopoulou, S.; Mourelatos, S.; Baka, A.; Pervanidou, D.; Vontas, J.; Hadjichristodoulou, C. Identification of climatic factors affecting the epidemiology of human West Nile virus infections in northern Greece. PLoS One 2016, 11(9), e0161510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaki Phytopathological Institute. Practical management plan for invasive mosquito species in Europe: I. Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) – Annex 7: Standard operational procedures for quality control on emergency treatments (Technical Report) 2020. [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, M.I.; Notarides, G.; Meletiou, S.; Patsoula, E.; Kavran, M.; Michaelakis, A.; Bellini, R.; Toumazi, T.; Bouyer, J.; Petrić, D. Two invasions at once: update on the introduction of the invasive species Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Cyprus–a call for action in Europe. Parasite 2023, 30, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinou, AF; Schäfer, SM; Bueno Mari, R; et al. A call to arms: Setting the framework for a code of practice for mosquito management in European wetlands. J Appl Ecol. 2020, 57, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinou, A. F.; Fawcett, J.; Georgiou, M. Occurrence of Aedes cretinus in Cyprus based on information collected by citizen scientists. Journal of the European Mosquito Control Association 2021, 39(1), 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetismis, K; Erguler, K; Angelidou, I; Yetismis, S; Fawcett, J; Foroma, E; Jarraud, N; Ozbel, Y; Martinou, AF. Establishing the Aedes watch out network, the first island-wide mosquito citizenscience initiative in Cyprus within the framework of the Mosquitoes Without Borders project. Management of Biological Invasions 2022, 13(4), 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontifes, PA; Doeuff, NL; Perrin, Y; Czeher, C; Ferré, JB; Rozier, Y; Foussadier, R; L'Ambert, G; Roiz, D. A 3-year entomological cluster randomised controlled trial to assess the efficacy of mass-trapping for Aedes albopictus control in France: The vectrap project. Acta Trop. 2025, 270, 107810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiras, AE; Costa, LH; Batista-Pereira, LG; Paixão, KS; Batista, EPA. Semi-field assessment of the Gravid Aedes Trap (GAT) with the aim of controlling Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti populations. PLoS One 2021, 16(4), e0250893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgillito, C; Manica, M; Marini, G; Rosà, R; Della Torre, A; Martini, S; Drago, A; Baseggio, A; Caputo, B. Evaluation of Bacillus thuringiensis Subsp. Israelensis and Bacillus sphaericus Combination Against Culex pipiens in Highly Vegetated Ditches. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2022, 38(1), 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgillito, C; Longo, E; Paolucci, S; Micocci, M; Manica, M; Filipponi, F; Vettore, S; Bonetto, D; Drago, A; Martini, S; Della Torre, A; Caputo, B. Lessons learned exploiting a multi-year large-scale data set derived from operational quality assessment of mosquito larval treatments in rain catch basins. Pest Manag Sci. 2025, 81(10), 6630–6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirrmann, T; Smith, TA; Modespacher, B; Müller, P. Evaluation of VectoMax FG application frequency for the control of Aedes albopictus and Culex species in urban catch basins: evidence from a randomised controlled trial. Parasit Vectors 2025, 18, 7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, O.; García-Berthou, E.; Tedesco, P.A.; et al. Origin and genetic diversity of mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki) introduced to Europe. Biol Invasions 2010, 12, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, I; Jakoby, O; Becker, N. Efficacy of native cyclopoid copepods in biological vector control with regard to their predatory behavior against the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus. Parasit Vectors 2022, 15(1), 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila-Barboza, J.A.; Gutierrez-Rodriguez, S.M.; Juache-Villagrana, A.E.; Lopez-Monroy, B.; Flores, A.E. Widespread Resistance to Temephos in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) from Mexico. Insects 2024, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aïzoun, N; Aïkpon, R; Gnanguenon, V; Oussou, O; Agossa, F; Padonou, G; Akogbéto, M. Status of organophosphate and carbamate resistance in Anopheles gambiae sensu lato from the south and north Benin, West Africa. Parasit Vectors 2013, 6, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brown, F. V.; Logan, R. A. E.; Wilding, C. S. Carbamate resistance in a UK population of the halophilic mosquito Ochlerotatus detritus implicates selection by agricultural usage of insecticide. International Journal of Pest Management 2019, 65(4), 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidy Massa, M.; Ould Lemrabott, M.A.; Gomez, N.; Ould Mohamed Salem Boukhary, A.; Briolant, S. Insecticide Resistance Status of Aedes aegypti Adults and Larvae in Nouakchott, Mauritania. Insects 2025, 16, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Invest, JF; Lucas, JR. Pyriproxyfen as a mosquito larvicide. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Urban Pests, Budapest, Hungary, July 13-16, 2008; pp. 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, M; Hatakoshi, M; Kawada, H; Takimoto, Y. Pyriproxyfen and other juvenile hormone analogues. Rev. Toxicol. 1998, 2, 357–394. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, CH; Mulligan, FS, III. Potential of pyriproxyfen for the control of urban mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in catch basins. J Econ Entomol. 1991, 84(4), 1156–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Lq.; Chen, Yh.; Tian, Yf.; et al. Study on the cross-resistance of Aedes albopictus (Skuse) (Diptera: Culicidae) to deltamethrin and pyriproxyfen. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustedt, JC; Boyce, R; Bradley, J; Hii, J; Alexander, N. Use of pyriproxyfen in control of Aedes mosquitoes: A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14(6), e0008205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- El-Shazly, MM; Refaie, BM. Larvicidal effect of the juvenile hormone mimic pyriproxyfen on Culex pipiens. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2002, 18(4), 321–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jambulingam, P.; Sadanandane, C.; Boopathi Doss, P.S.; Subramanian, S.; Zaim, M. Field evaluation of an insect growth regulator, pyriproxyfen 0.5% GR against Culex quinquefasciatus, the vector of Bancroftian filariasis in Pondicherry, India. Acta Tropica 2008, 107(1), 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, G; Paul, REL; Pires, B; Alves, G; de Jesus, A; Silva, AC; Devine, GJ; Sousa, CA. An evaluation of efficacy of the auto-dissemination technique as a tool for Aedes aegypti control in Madeira, Portugal. Parasit Vectors 2019, 12(1), 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckner, EA; Williams, KF; Marsicano, AL; Latham, MD; Lesser, CR. Evaluating the Vector Control Potential of the In2Care® Mosquito Trap Against Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus Under Semifield Conditions in Manatee County, Florida. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2017, 33(3), 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drago, A; Simonato, G; Vettore, S; Martini, S; Marcer, F; di Regalbono, AF; Cassini, R. Efficacy of Aquatain Against Aedes albopictus Complex and Culex pipiens in Catch Basins in Italy. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2020, 36(1), 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavran, Mihaela; Pajovic, Igor; Petric, Dusan; Ignjatovic-Cupina, Aleksandra; Latinovic, Nedeljko; Jovanovic, Miomir; Quarrie, Stephen Alexander; Zgomba, Marija. : Aquatain AMF efficacy on juvenile mosquito stages in control of Culex pipiens complex and Aedes albopictus. Entomologia Experimentalis et ApplicataVolume 2020, Volume 168(Issue 2Feb 2020Pagesi-iv), 119–197. [Google Scholar]

- Alphey, L.; Benedict, M.; Bellini, R.; Clark, G.G.; Dame, D.A.; Service, M.W.; Dobson, S.L. Sterile-Insect Methods for Control of Mosquito-Borne Diseases: An Analysis. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010, 10, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-H.; Gamez, S.; Raban, R.R.; Marshall, J.M.; Alphey, L.; Li, M.; Rasgon, J.L.; Akbari, O.S. Combating Mosquito-Borne Diseases Using Genetic Control Technologies. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzaro, GC; Sánchez, C HM; Collier, TC; Marshall, JM; James, AA. Population modification strategies for malaria vector control are uniquely resilient to observed levels of gene drive resistance alleles. Bioessays 2021, 43(8), e2000282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, A. Heritable Strategies for Controlling Insect Vectors of Disease. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, C.F.; Benedict, M.Q.; Collins, C.M.; Baldet, T.; Bellini, R.; Bossin, H.; Bouyer, J.; Corbel, V.; Facchinelli, L.; Fouque, F.; et al. Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) against Aedes Species Mosquitoes: A Roadmap and Good Practice Framework for Designing, Implementing and Evaluating Pilot Field Trials. Insects 2021, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourtzis, K.; Vreysen, M.J.B. Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) and Its Applications. Insects 2021, 12, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, R; Lim, JT; Ferreira, AGA; Ponti, L; Giovanetti, M; Yi, CJ; Tewari, P; Cholvi, M; Crawford, J; Gutierrez, AP; Dobson, SL; Ross, PA. Exploiting Wolbachia as a Tool for Mosquito-Borne Disease Control: Pursuing Efficacy, Safety, and Sustainability. Pathogens 2025, 14(3), 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Shropshire, J.D.; Cross, K.L.; Leigh, B.; Mansueto, A.J.; Stewart, V.; Bordenstein, S.R.; Bordenstein, S.R. Living in the Endosymbiotic World of Wolbachia: A Centennial Review. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourtzis, K.; Dobson, S.L.; Xi, Z.; Rasgon, J.L.; Calvitti, M.; Moreira, L.A.; Bossin, H.C.; Moretti, R.; Baton, L.A.; Hughes, G.L.; et al. Harnessing Mosquito-Wolbachia Symbiosis for Vector and Disease Control. Acta Trop. 2014, 132, S150–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidler, A.L.; Marrogi, E.; Kauffman, J.; Paton, D.G.; Westervelt, K.A.; Church, G.M.; Esvelt, K.M.; Shaw, W.R.; Catteruccia, F. CRISPR-Mediated Germline Mutagenesis for Genetic Sterilization of Anopheles Gambiae Males. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yang, T.; Bui, M.; Gamez, S.; Wise, T.; Kandul, N.P.; Liu, J.; Alcantara, L.; Lee, H.; Edula, J.R.; et al. Suppressing Mosquito Populations with Precision Guided Sterile Males. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phuc, H.K.; Andreasen, M.H.; Burton, R.S.; Vass, C.; Epton, M.J.; Pape, G.; Fu, G.; Condon, K.C.; Scaife, S.; Donnelly, C.A.; et al. Late-Acting Dominant Lethal Genetic Systems and Mosquito Control. BMC Biol. 2007, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinner, S.A.M.; Barnes, Z.H.; Puinean, A.M.; Gray, P.; Dafa’alla, T.; Phillips, C.E.; Nascimento de Souza, C.; Frazon, T.F.; Ercit, K.; Collado, A.; et al. New Self-Sexing Aedes aegypti Strain Eliminates Barriers to Scalable and Sustainable Vector Control for Governments and Communities in Dengue-Prone Environments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 975786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, A.; Galizi, R.; Kyrou, K.; Simoni, A.; Siniscalchi, C.; Katsanos, D.; Gribble, M.; Baker, D.; Marois, E.; Russell, S.; et al. ACRISPR-Cas9 Gene Drive System Targeting Female Reproduction in the Malaria Mosquito Vector Anopheles gambiae. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, HA; O'Neill, SL. Controlling vector-borne diseases by releasing modified mosquitoes. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16(8), 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ross, PA; Robinson, KL; Yang, Q; Callahan, AG; Schmidt, TL; Axford, JK; et al. A decade of stability for wMel Wolbachia in natural Aedes aegypti populations. PLoS Pathog 2022, 18(2), e1010256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantz, VM; et al. Highly efficient Cas9-mediated gene drive for population modification of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2015, 112, E6736–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galizi, R; et al. A CRISPR-Cas9 sex-ratio distortion system for genetic control. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 31139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtewold, T.; Lwetoijera, D.W.; Hoermann, A.; et al. Gene-drive-capable mosquitoes suppress patient-derived malaria in Tanzania. Nature 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, AA; Ahmad, NW; Keong, WM; Ling, CY; Ahmad, NA; Golding, N; Tierney, N; Jelip, J; Putit, PW; Mokhtar, N; Sandhu, SS; Ming, LS; Khairuddin, K; Denim, K; Rosli, NM; Shahar, H; Omar, T; Ridhuan Ghazali, MK; Aqmar Mohd Zabari, NZ; Abdul Karim, MA; Saidin, MI; Mohd Nasir, MN; Aris, T; Sinkins, SP. Introduction of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes carrying wAlbB Wolbachia sharply decreases dengue incidence in disease hotspots. iScience 2024, 27(2), 108942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly JB, Burt A, Christophides G, Diabate A, Habtewold T, Hancock PA, James AA, Kayondo JK, Lwetoijera DW, Manjurano A, McKemey AR, Santos MR, Windbichler N, Randazzo F. Considerations for first field trials of low-threshold gene drive for malaria vector control. Malar J. 2024 May 22;23(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s12936-024-04952-9. Erratum in: Malar J. 2024 Aug 5;23(1):233. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kapranas, A.; Collatz, J.; Michaelakis, A.; Milonas, P. Review of the role of sterile insect technique within biologically-based pest control–an appraisal of existing regulatory frameworks. Entomologia Experimentalis Et Applicata 2022, 170(5), 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, R.; Calvitti, M.; Medici, A.; Carrieri, M.; Celli, G.; Maini, S. Use of the Sterile Insect Technique Against Aedes albopictus in Italy: First Results of a Pilot Trial. In Area-Wide Control of Insect Pests; Vreysen, M.J.B., Robinson, A.S., Hendrichs, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur, C.; Almenar, D.; Zacarés, M.; Benlloch-Navarro, S.; Pla, I.; Dalmau, V. Suppression Trial through an Integrated Vector Management of Aedes albopictus (Skuse) Based on the Sterile Insect Technique in a Non-Isolated Area in Spain. Insects 2023, 14, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balatsos, G.; Puggioli, A.; Karras, V.; Lytra, I.; Mastronikolos, G.; Carrieri, M.; Papachristos, D.P.; Malfacini, M.; Stefopoulou, A.; Ioannou, C.S.; Balestrino, F. Reduction in egg fertility of Aedes albopictus mosquitoes in Greece following releases of imported sterile males. Insects 2021, 12(2), 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balatsos, G; Karras, V; Puggioli, A; Balestrino, F; Bellini, R; Papachristos, DP; Milonas, PG; Papadopoulos, NT; Malfacini, M; Carrieri, M; Kapranas, A; Mamai, W; Mastronikolos, G; Lytra, I; Bouyer, J; Michaelakis, A. Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) field trial targeting the suppression of Aedes albopictus in Greece. Parasite 2024, 31, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefopoulou, A.; LaDeau, S.L.; Syrigou, N.; Balatsos, G.; Karras, V.; Lytra, I.; Boukouvala, E.; Papachristos, D.P.; Milonas, P.G.; Kapranas, A.; Vahamidis, P. Knowledge, attitude, and practices survey in Greece before the implementation of sterile insect technique against Aedes albopictus. Insects 2021, 12(3), 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrondo Monton, D; Ravasi, D; Campana, V; Pace, F; Puggioli, A; Tanadini, M; Flacio, E. Effectiveness of the sterile insect technique in controlling Aedes albopictus as part of an integrated control measure: evidence from a first small-scale field trial in Switzerland. Infect Dis Poverty 2025, 14(1), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bouyer, J; Gil, DA; Mora, IP; Sorlí, VD; Maiga, H; Mamai, W; Claudel, I; Brouazin, R; Yamada, H; Gouagna, LC; Rossignol, M; Chandre, F; Dupraz, M; Simard, F; Baldet, T; Lancelot, R. Suppression of Aedes mosquito populations with the boosted sterile insect technique in tropical and Mediterranean urban areas. Sci Rep. 2025, 15(1), 17648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Giatropoulos, A.; Balatsos, G.; Karras, V.; Lancelot, R.; Bouyer, J.; Puggioli, A.; Bellini, R.; Papadopoulos, N.T.; Papachristos, D.P.; Mouratidis, I.; Michaelakis, A. Suppression of the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) populations using the boosted sterile insect technique in Greece. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1), 38738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur, C.; Almenar, D.; Benlloch-Navarro, S.; Argilés-Herrero, R.; Zacarés, M.; Dalmau, V.; Pla, I. Sterile Insect Technique in an Integrated Vector Management Program against Tiger Mosquito Aedes albopictus in the Valencia Region (Spain): Operating Procedures and Quality Control Parameters. Insects 2021, 12, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balatsos, G.; Blanco-Sierra, L.; Karras, V.; Puggioli, A.; Osório, H.C.; Bellini, R.; Papachristos, D.P.; Bouyer, J.; Bartumeus, F.; Papadopoulos, N.T.; Michaelakis, A. Residual longevity of recaptured sterile mosquitoes as a tool to understand field performance and reveal quality. Insects 2024, 15(11), 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastronikolos, G.D.; Kapranas, A.; Balatsos, G.K.; Ioannou, C.; Papachristos, D.P.; Milonas, P.G.; Puggioli, A.; Pajović, I.; Petrić, D.; Bellini, R.; Michaelakis, A. Quality control methods for Aedes albopictus sterile male transportation. Insects 2022, 13(2), 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvitti, M; Moretti, R; Lampazzi, E; Bellini, R; Dobson, SL. Characterization of a new Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae)-Wolbachia pipientis (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) symbiotic association generated by artificial transfer of the wPip strain from Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol 2010, 47(2), 179–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvitti, M; Moretti, R; Skidmore, AR; Dobson, SL. Wolbachia strain wPip yields a pattern of cytoplasmic incompatibility enhancing a Wolbachia-based suppression strategy against the disease vector Aedes albopictus. Parasit Vectors 2012, 5, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caputo, B; Moretti, R; Manica, M; Serini, P; Lampazzi, E; Bonanni, M; Fabbri, G; Pichler, V; Della Torre, A; Calvitti, M. A bacterium against the tiger: preliminary evidence of fertility reduction after release of Aedes albopictus males with manipulated Wolbachia infection in an Italian urban area. Pest Manag Sci. 2020, 76(4), 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidelines for mosquito control in built-up areas in Europe (European Mosquito Control Association Technical Report). In European Mosquito Control Association; Seelig, F., Ed.; 10 October 2024; Available online: https://www.emca-online.eu/assets/PDFs/EMCA_published_guideline_9281-1_0_compressed.pdf.

- Liu, WL; Wang, Y; Chen, YX; Chen, BY; Lin, AY; Dai, ST; Chen, CH; Liao, LD. An IoT-based smart mosquito trap system embedded with real-time mosquito image processing by neural networks for mosquito surveillance. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1100968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rajak, P; Ganguly, A; Adhikary, S; Bhattacharya, S. Smart technology for mosquito control: Recent developments, challenges, and future prospects. Acta Trop.;Epub 2024, 258, 107348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, D.; Mafra, S. Implementation of an Intelligent Trap for Effective Monitoring and Control of the Aedes aegypti Mosquito. Sensors 2024, 24, 6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Escobar, G; Moreno, M; Fornace, K; Herrera-Varela, M; Manrique, E; Conn, JE. The use of drones for mosquito surveillance and control. Parasit Vectors 2022, 15(1), 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saran, S.; Singh, P. Systematic review on citizen science and artificial intelligence for vector-borne diseases . In Proceedings of the ISPRS TC IV Mid-term Symposium “Spatial Information to Empower the Metaverse”; Zlatanova, S., Brovelli, M. A., Wu, H., Helmholz, P., Chen, R., Chen, L., Eds.; Copernicus Publications., 2024; Vol. XLVIII-4-2024, pp. 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, BA; Garriga, J; Eritja, R; Palmer, JRB; Bartumeus, F; Csabai, I. Deep learning identification for citizen science surveillance of tiger mosquitoes. Sci Rep. 2021, 11(1), 4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dom, N.C.; Abdullah, N.A.M.H.; Dapari, R.; et al. Fine-scale predictive modeling of Aedes mosquito abundance and dengue risk indicators using machine learning algorithms with microclimatic variables. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 37017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, H; Ansharullah, BA. The role of artificial intelligence for dengue prevention, control, and management: A technical narrative review. Acta Trop.;Epub 2025, 268, 107741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Jia-Lin; Li, Hua; He, Qi; Jin, Bin-Yan; Liu, Zhe; Zhang, Xiao-Ming; Zhang, Li. Integrating classic AI and agriculture: A novel model for predicting insecticide-likeness to enhance efficiency in insecticide development. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2024, Volume 112, 108113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.E.; Clarke, D.W.; Criswell, V.; et al. Efficient production of male Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes enables large-scale suppression of wild populations. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 38, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A; Ceccarelli, G; Alcantara, LCJ; Ferreira, A; Ciccozzi, M; Giovanetti, M. Wolbachia-Based Approaches to Controlling Mosquito-Borne Viral Threats: Innovations, AI Integration, and Future Directions in the Context of Climate Change. Viruses 2024, 16(12), 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mukabana, W.R.; Welter, G.; Ohr, P.; Tingitana, L.; Makame, M.H.; Ali, A.S.; Knols, B.G.J. Drones for Area-Wide Larval Source Management of Malaria Mosquitoes. Drones 2022, 6, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Maza, I.; Ollero, A.; Gutierrez, D.; Aguirre, I.; Viguria, A. Release of Sterile Mosquitoes with Drones in Urban and Rural Environments under the European Drone Regulation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirk, J. L.; Ballard, H. L.; Wilderman, C. C.; Phillips, T.; Wiggins, A.; Jordan, R.; McCallie, E.; Minarchek, M.; Lewenstein, B. V.; Krasny, M. E.; Bonney, R. Public Participation in Scientific Research: a Framework for Deliberate Design. Ecology and Society 2012, 17(2). Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26269051. [CrossRef]

- Allen, T; Crouch, A; Topp, SM. Community participation and empowerment approaches to Aedes mosquito management in high-income countries: a scoping review. Health Promot Int. 2021, 36(2), 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubler, DJ; Clark, GG. Community involvement in the control of Aedes aegypti. Acta Trop 1996, 61(2), 169–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Public management and essential public health functions. World Bank. 2025. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/121c101f-6c70-5e68-a838-2456b1f682fb.

- Palmer, JRB; Oltra, A; Collantes, F; Delgado, JA; Lucientes, J; Delacour, S; Bengoa, M; Eritja, R; Bartumeus, F. Citizen science provides a reliable and scalable tool to track disease-carrying mosquitoes. Nat Commun 2017, 8(1), 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bartumeus, F.; Oltra, A.; Palmer, J. R. B. Citizen science: A gateway for innovation in disease-carrying mosquito management? . Trends in Parasitology 2018, 34(9), 727–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, R. M.; Mapes, C.; Low, R. D.; Long, A.; Bowser, A.; Durieux, D.; Rivera, K.; Dekramanjian, B.; Bartumeus, F.; Guerrero, D.; Seltzer, C. E.; Azam, F.; Chellappan, S.; Palmer, J. R. B. Integrating Global Citizen Science Platforms to Enable Next-Generation Surveillance of Invasive and Vector Mosquitoes. Insects 2022, 13(8), 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, T; Harvey, M; Lightfoot, P; Kilbey, D; Papadopoulos, T; Jepson, P. 2015 Emerging technologies for biological recording. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 115, 731–749. [CrossRef]

- Sheard, JK; et al. Emerging technologies in citizen science and potential for insect monitoring. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2024, 379, 20230106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Mosquito Program World Mosquito Program. 2025. Available online: https://www.worldmosquitoprogram.org.

- Njue, N.; Kroese, J. Stenfert; Gräf, J.; Jacobs, S.R.; Weeser, B.; Breuer, L.; Rufino, M.C. Citizen science in hydrological monitoring and ecosystem services management: State of the art and future prospects. Science of The Total Environment 2019, Volume 693, 133531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekramanjian, B.; Bartumeus, F.; Kampen, H.; Palmer, J. R. B.; Werner, D.; Pernat, N. Demographic and motivational differences between participants in analog and digital citizen science projects for monitoring mosquitoes. Scientific reports 2023, 13(1), 12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abourashed, A.; de Best, P.A.; Doornekamp, L.; et al. Development and validation of the MosquitoWise survey to assess perceptions towards mosquitoes and mosquito-borne viruses in Europe. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, P.; Aschan-Leygonie, C.; Valiente Moro, C. A review of knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding mosquitoes and mosquito-borne infectious diseases in nonendemic regions. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11, 1239874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputo, B; Manica, M; Russo, G; Solimini, A. Knowledge, attitude and practices towards the tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus. A questionnaire based survey in Lazio region (Italy) before the 2017 chikungunya outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolimenakis, A; Tsesmelis, D; Richardson, C; Balatsos, G; Milonas, PG; Stefopoulou, A; et al. Knowledge, attitudes and perception of mosquito control in different citizenship regimes within and surrounding the Malakasa open accommodation refugee camp in Athens, Greece. IJERPH 2022, 19, 16900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcó, N; Giménez, N; Serra, M; Ripoll, A; García, M; Vives, P. Asian tiger mosquito bites: perception of the affected population after Aedes albopictus became established in Spain. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas (English Edition) 2008, 99, 708–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J; Kampen, H; Walther, D. The nuisance mosquito Anopheles plumbeus (Stephens, 1828) in Germany: a questionnaire survey may help support surveillance and control. Front Public Health 2017, 5, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisia, M.; Balatsos, G.; Beleri, S.; Tegos, N.; Zavitsanou, E.; LaDeau, S.L.; Sotiroudas, V.; Patsoula, E.; Michaelakis, A. Mitigating the Threat of Invasive Mosquito Species Expansion: A Comprehensive Entomological Surveillance Study on Kastellorizo, a Remote Greek Island. Insects 2024, 15(9), 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roiz, D.; Pontifes, P. A.; Jourdain, F.; Diagne, C.; Leroy, B.; Vaissière, A. C.; Tolsá-García, M. J.; Salles, J. M.; Simard, F.; Courchamp, F. The rising global economic costs of invasive Aedes mosquitoes and Aedes-borne diseases. The Science of the total environment 2024, 933, 173054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apouey, S. Challenges and bottlenecks in European vector-control programmes during large-scale arbovirus outbreaks. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, M.Q. Economic and societal impacts of dengue and chikungunya outbreaks in Southern Europe. Eurosurveillance 2022, 78(12), 2200456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Prokopec, G. M.; Kitron, U.; Montgomery, B.; Horne, P.; Ritchie, S. A. Quantifying the spatial dimension of dengue virus epidemic spread within a tropical urban environment. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2010, 4(12), e920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, C., Nwankwo, U., Lenk, E., de Vlas, S. J., & Bundy, D. A. P. (2017). An investment case for ending neglected tropical diseases. In Holmes, K. K., Bloom, B. R., & others (Eds.), Major Infectious Diseases (3rd ed.) (pp. 371–396). The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.A.; Hudgins, E.J.; Cuthbert, R.N.; et al. Managing biological invasions: the cost of inaction. Biol Invasions 2022, 24, 1927–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roiz, D.; Wilson, A. L.; Scott, T. W.; Fonseca, D. M.; Jourdain, F.; Müller, P.; Velayudhan, R.; Corbel, V. Integrated Aedes management for the control of Aedes-borne diseases. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2018, 12(12), e0006845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelakis, A.; Balestrino, F.; Becker, N.; Bellini, R.; Caputo, B.; della Torre, A.; Figuerola, J.; L’Ambert, G.; Petric, D.; Robert, V.; Roiz, D.; Saratsis, A.; Sousa, C. A.; Wint, W. G. R.; Papadopoulos, N. T. A case for systematic quality management in mosquito control programmes in Europe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18(7), 3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, O. J.; Kharisma, D. D.; Wilastonegoro, N. N.; O’Reilly, K. M.; Hendrickx, E.; Bastos, L. S.; Yakob, L.; Shepard, D. S. The cost-effectiveness of controlling dengue in Indonesia using wMel Wolbachia released at scale: A modelling study. BMC Medicine 2020, 18(186), 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]