1. Introduction

Malaria remains a significant global public health threat, with approximately 263 million cases and 597,000 fatalities reported worldwide in 2023. Angola bears a substantial portion of this burden, accounting for 3.1% of global malaria cases and 2.7% of related deaths [

1]. In 2023, Angola recorded a malaria incidence rate of 260 per 1,000 population at risk. This figure represents an increase of between 25% and 63% compared to 2015 baseline. Angola is among the countries in the WHO African region where the estimated case incidence was higher in 2023 than in 2015 [

1]. Despite these figures, Angola made significant strides in reducing its malaria mortality rate from 58.2% in 2016 to 26.3% in 2019 [

2]. Most malaria cases in Angola are caused by

Plasmodium falciparum [

3].

In Angola, malaria transmission is complex, with the presence of multiple vectors, including

Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto (s.s.),

An. coluzzii,

An. arabiensis, and

An. funestus s.s. [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Members of the Funestus group, previously confirmed as secondary malaria vectors in other regions, have also been recently reported in Angola [

7], highlighting the need for further investigation into the lesser-studied species of this group. Vector control is primarily made through the distribution of insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITN) and indoor residual spraying (IRS). However, the effectiveness of these interventions can be compromised by the emergence of knockdown resistance (kdr), which is associated with pyrethroids and DDT insecticides. Kdr mutations, particularly West African L1014F and East African L1014S, have already been documented in

An. gambiae complex populations in various locations in Angola [

7,

8], causing a significant threat to the efficacy ITN and IRS [

9,

10,

11].

The Cuando Cubango province was previously classified as mesoendemic with unstable malaria transmission. According to the updated malaria risk stratification map, four districts in the province are now classified as having moderate transmission, two as high transmission, and three as very high transmission [

2]. In 2018 the prevalence of malaria in the province was 38%, the second highest in the country [

12]. To address the challenges of the province, the National Malaria Control Program (NMCP), in partnership with international partners, intensified efforts to control and eliminate malaria in southern Angola. Since 2018, a large-scale IRS campaign has been implemented in the province with support from the Elimination 8 Initiative (E8). The E8 focused on reducing malaria transmission within Angola and strengthening elimination efforts in neighbouring Republic of Namibia through coordinated cross-border interventions, enhanced surveillance, and expanded access to malaria services in border areas [

13]. NMCP, in collaboration with The Mentor Initiative has implemented IRS activities across the border districts in southern Angola, including the four border districts of Cuando Cubango. During the 2019/2020 campaign, 13,047 structures were sprayed across the districts of Calai, Cuangar, Dirico, and Rivungo, protecting 57,157 people and achieving a coverage of 97.8%. In addition to IRS, an ITN campaign was conducted in the province in 2018, during which 286,543 ITNs were distributed, covering 98.5% of the population. From 2018, operational research studies and field assessments have been conducted to evaluate the coverage, effectiveness, and overall impact of these interventions [

12]. Nevertheless, limited information is available on the composition of malaria vector species,

P. falciparum infection rates, host preferences, and the presence of kdr mutations in Cuando Cubango province. Understanding these factors is essential for designing effective, evidence-based, and geographically tailored vector control strategies. This study aimed to update the entomological profile of malaria vectors in the province and to assess the impact of the 2020/2021 IRS campaign on entomological indicators.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

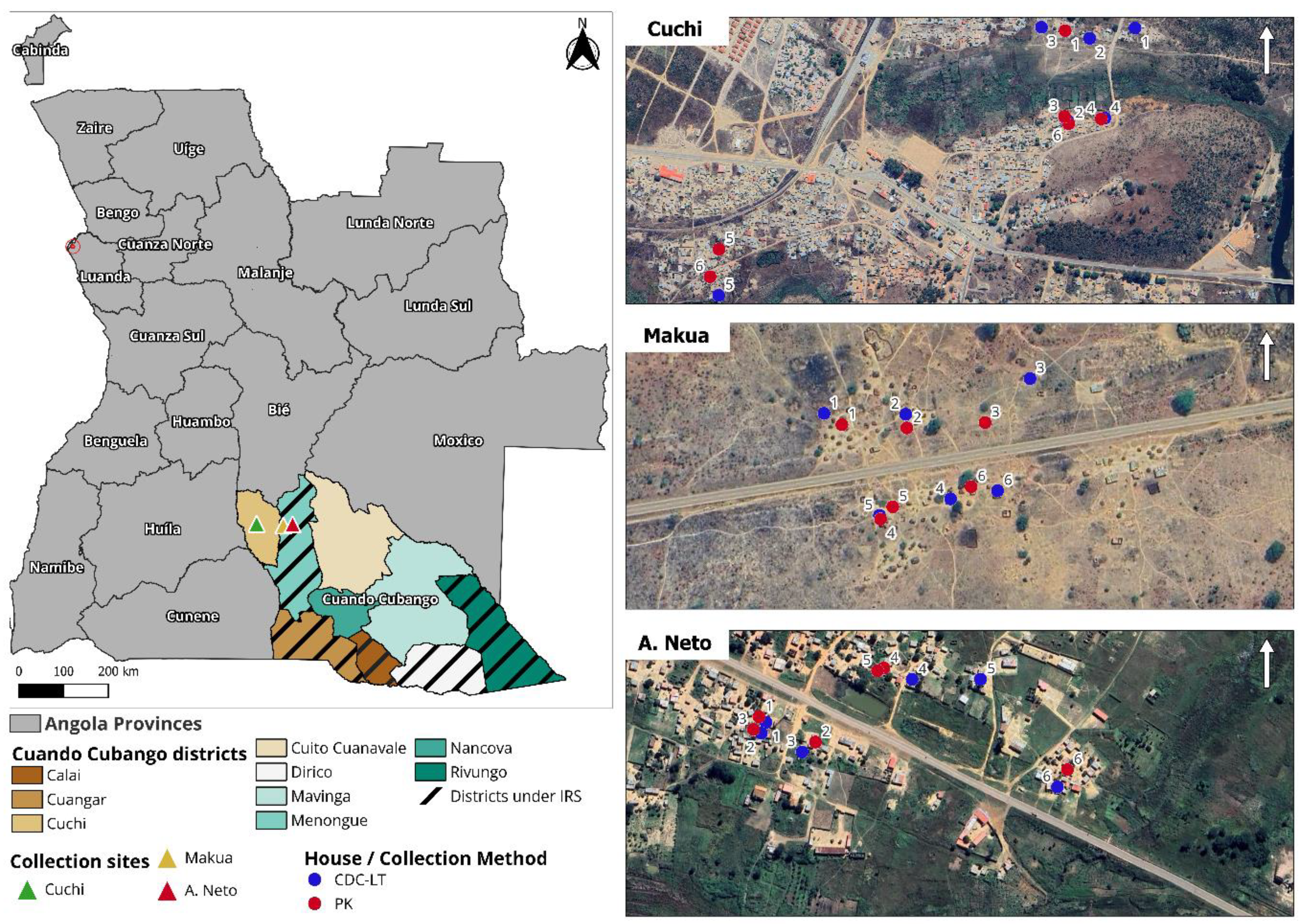

The study was conducted in Cuando Cubango province, located in southeastern Angola. Cuando Cubango shares borders with Republic of Namibia to the south and with the Angolan provinces of Moxico to the north, Bié to the northwest, Huíla to the west, and Cunene to the southwest. The province covers an area of approximately 199,049 km² and had a population of 534,002 [

14]. The average elevation of the province is around 1,200 meters above sea level. Major rivers crossing the province include the Cuando, Cubango, and Cuito rivers [

15]. The average temperature in Cuando Cubango varies between 16.3 °C and 25.5 °C, with a rainy season from October to April and a dry season from May to September.

2.2. Cuando Cubango IRS Campaign

The Cuando Cubango IRS campaign ran from December 2020 to February 2021 in the four border districts of Calai, Cuangar, Dirico, and Rivungo. In this campaign the Menongue district was also included (

Figure 1). A total of 1,519 individuals were trained, including spray operators, enumerators, mobilizers, data collectors, team leaders and supervisors. Training followed the regional Southern Africa Development Community Malaria Elimination Eight Secretariat (SADAC-MEES) guidelines, and included modules on insecticide handling, safety, spray technique, data collection, and community sensitization [

16]. The selection of sprayable structures was conducted in accordance with the previous guidelines. Actellic® 300 CS (active ingredient: pirimiphos-methyl) was applied at a dosage of 1 g/m². Structures enumeration, microplanning, and real-time monitoring were carried out using the pilot version of Reveal v.1 (Akros Inc.). Data was collected using mobile devices, synchronized through the Reveal platform, and used to generate automated reports on campaign progress and coverage.

2.3. Post-IRS Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Survey

A community-based cross-sectional Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) study was conducted from February to March 2021 in the districts of Calai, Cuangar, Dirico, and Menongue, following the completion of the IRS campaign. Households were selected using a two-stage randomized cluster sampling method. One adult respondent per household was interviewed using a structured questionnaire that had been previously piloted in Menongue. The questionnaire assessed knowledge of malaria transmission and symptoms, attitudes towards IRS and malaria prevention, household practices including ITN use, IRS compliance and environmental risk factors. Direct observations were made regarding housing conditions and IRS use. Data was collected using KoboToolbox, validated daily and analysed using Microsoft Excel. Ethical approval was obtained from the Angolan National Ethics Committee.

2.4. Entomological Surveillance and Mosquito Collections

Two districts were selected for the entomological survey: Menongue (targeted for IRS) and Cuchi (no IRS intervention) (

Figure 1). Collection sites were chosen based on logistical capacity and IRS campaign plans. Adult mosquitoes were collected from three sites: two in the district of Menongue: Makua and Agostinho Neto (A. Neto), and one in the district of Cuchi: Cuchi. At each site, twelve houses were randomly selected for adult mosquito collections and equally assigned to one of the sampling methods. Informed consent was obtained from the head of each household, and collection procedures were clearly communicated to all household members. Mosquitoes were collected monthly over three consecutive nights from November 2020 to March 2021. Indoor host-seeking mosquitoes were captured using CDC light traps (CDC-LT; Model 512; John W. Hock Company, Gainesville, Florida, USA). Traps were placed at the foot end of occupied sleeping areas, approximately 1.5 meters above the ground, and operated from 18:00 to 07:00. Indoor resting mosquitoes were captured with Prokopack aspirators (PK; Model 1419, John W. Hock Company, USA). Indoor aspirations were conducted in the morning from 07:00 to 09:00 by two collectors. Each house was examined for 15 minutes, with special attention paid to areas where people had slept the previous night. PK collection cups were replaced every 5 minutes to prevent damage to the aspirated mosquitoes. Collected mosquitoes were transported to the field insectary for morphological identification. Larval collections were conducted across multiple breeding sites across both districts using the standard dipping method. Larvae were transferred to the field insectary and reared to adulthood. At 48h post-emergence, the adults were killed in an alcohol chamber and subjected to morphological identification.

2.5. Morphological Identification

Female

Anopheles mosquitoes were identified using well-established morphological keys [

17,

18]. Morphological identifications were carried out by trained entomologists in the field insectary. Abdomens from female

Anopheles mosquitoes were categorised as fed, unfed, gravid and half-gravid. Samples were stored individually in labelled microtubes containing blue indicator silica gel at room temperature.

2.6. Molecular Species Identification of Anopheles Mosquitoes

An. gambiae complex and Funestus group members were identified to species level by molecular methods. Genomic DNA was individually extracted from legs [

19]. Molecular identification of

An. gambiae complex members were performed using known protocols [

20,

21]. Members of the Funestus group were identified through a multiplex PCR assay to separate

An. funestus s.s. from the more zoophilic species

An. parensis,

An. rivulorum,

An. rivulorum-like,

An. leesoni, and

An. vaneedeni [

19,

22]. Negative controls included a PCR master mix without DNA template and a DNA extraction negative control. Positive controls comprised samples with previously established species molecular identification.

2.7. Detection of Plasmodium Falciparum Circumsporozoite Protein

Head and thoraces of unfed female Anopheles mosquitoes were analysed for the presence of the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP) by enzyme-linked-immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [

23]. If a mosquito tested positive, a confirmatory ELISA test was performed using a boiling step [

24]. Mosquitoes were considered positive for P. falciparum CSP if both tests yielded positive results.

2.8. Blood Meal Origin

Abdomens of blood-fed

Anopheles mosquitoes were subjected to multiplex-PCR targeting the cytochrome B gene for the source of the blood meal [

22]. Five potential hosts were tested: human, cow, goat, pig, and dog.

2.9. Detection of Knockdown Resistance

Knockdown resistance mutations were investigated in An. arabiensis and An. gambiae s.s. following the protocols targeting kdr-West (L1014F) and kdr-East (L1014S) mutations [

25,

26,

27].

2.10. Entomological Parameters and Statitical Analysis

Entomological parameters were assessed before (November 2020 to January 2021) and after IRS (February to March 2021). P. falciparum infection rate (IR%) was calculated as the percentage of unfed mosquitoes testing positive for CSP in the head-thorax (IR% = no. of CSP-positive head-thorax samples / total no. of head-thorax analysed × 100). Human blood index (HBI) was calculated as the proportion of blood-fed anopheline mosquitoes that fed on humans including those with mixed blood-meal (HBI = no. of human-fed mosquitoes / total no. of blood-fed mosquitoes analysed x 100). Adjusted HBI was used to compensate for unidentified blood-meal sources, excluding mosquitoes with unidentified blood-meal from the formula [

28]. Vector density (VD) was calculated as the number of Funestus group members per night per CDC-LT per month. Indoor resting density (IRD) was calculated as the number of Funestus group members collected resting indoors per house (IRD = No. of Funestus group members collected indoor by PK / No. of surveyed houses). To assess the impact of IRS on entomological parameters, we conducted a before-and-after analysis at the A. Neto and Makua collection sites, comparing IRD, VD, and IR% pre- and post-IRS. Chi-square test was used to compare proportions, with a significance level set at 0.05.

2.11. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The entomological and KAP studies received approval from the Instituto Nacional de Investigação em Saúde de Angola (INIS), under approval letters 05/2021 and 06/2021, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Cuando Cubango IRS Campaing and Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Survey

The 2020/2021 IRS campaign was conducted from December 2020 to February 2021 across the districts of Rivungo, Dirico, Calai, Cuangar, and Menongue, covering 17 communes (

Table 1). A total of 102,569 structures were identified, of which 94,609 were successfully sprayed, achieving a coverage rate of 92.2%. The campaign reached 334,604 individuals, an increase of 485.5% compared to the previous campaign, primarily due to the inclusion of Menongue district. Excluding Menongue, the increase compared to the 2019/2020 IRS campaign was 28.9%. Regardig the KAP survey, a total of 647 heads of households were interviewed. Among respondents, 92.4% reported having received IRS in the previous year. Additionally, 87% correctly identified mosquitoes as the primary vectors of malaria, and 78% recognized key symptoms such as fever and chills. Attitudes toward IRS were positive, with 89% of participants supporting its continued implementation. Reported adherence to post-IRS precautions, such as refraining from washing treated walls, exceeded 70%. Only 12% of respondents expressed a preference for ITNs over IRS, primarily due to the perceived longer-lasting protection offered by IRS. Direct observations indicated that in fewer than 80% of sprayed households, IRS marks remained visible and insecticide-treated surfaces were intact, suggesting moderate retention of treatment indicators.

3.3. Anopheles Species Composition

A total of 1,436 adult mosquitoes were collected across the three sampling sites. Of these, 549 (38.2%) were female and 20 (1.4%) were male

Anopheles. Among the females, 86.1% were captured using CDC-LT (

Table 2). Unfed

Anopheles comprise the majority of the collections (74.9%), followed by blood-fed females (23.9%) (

Table 2). Makua accounted for 51.5% of all adult

Anopheles mosquitoes (

Table 3). In total, ten

Anopheles species were identified. Funestus group was the most prevalent, accounting for 91.4% of all

Anopheles collected, followed by

An. gambiae complex,

An. rufipes,

An. squamosus,

An. concolor, and

An. ruarinus (

Table 3). Species-specific identification of a subsample of the Funestus group revealed the presence of multiple members. The majority were identified as

An. funestus s.s. (91.7%), followed by

An. vaneedeni,

An. leesoni,

An. rivulorum, and

An. rivulorum-like. The remaining 26 specimens failed to amplify. Regarding the

An. gambiae complex, ten were identified as

An. arabiensis, while four failed to amplify (

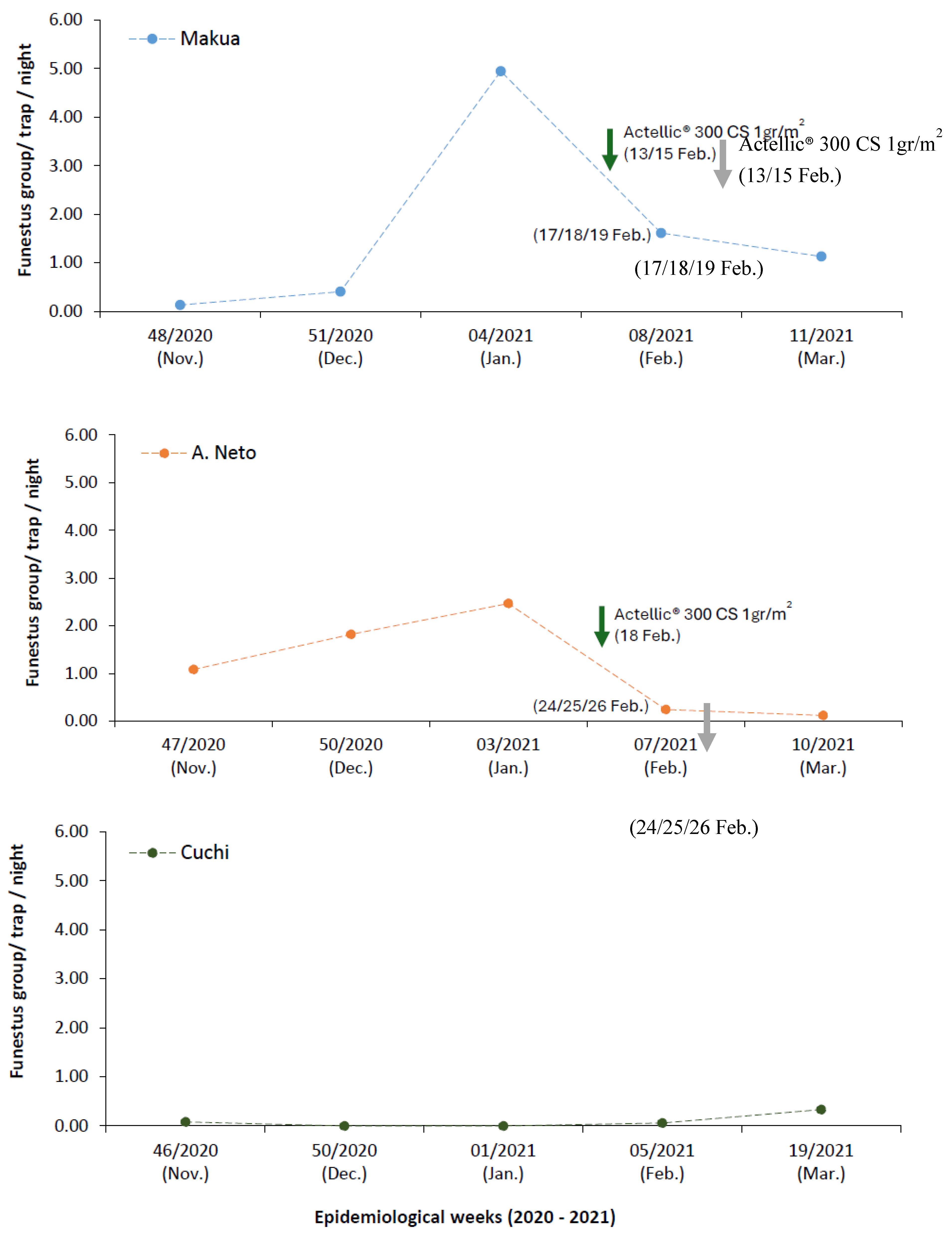

Table 4). In A. Neto and Makua, a rising VD was observed from November 2020 to January 2021, followed by a decrease after IRS (

Figure 2). In Cuchi, the VD is constantly low, increasing from January to March (

Figure 2). When comparing the periods before and after IRS (

Table 5), we observed in A. Neto, a significant decrease in VD from 2.03 mosquitoes/trap/night pre-IRS to 0.18 mosquitoes/trap/night post-IRS (χ², p < 0.0001). In Makua, no significant difference was observed, with VD increasing slightly from 0.99 to 1.36 mosquitoes/trap/night (χ², p > 0.05). In Cuchi, a significant increase in VD was recorded, rising from 0.02 to 0.22 mosquitoes/trap/night (χ², p < 0.01). For Funestus group IRD, results showed a significant decrease at both the Makua and A. Neto after IRS intervention (χ² test, p < 0.001) (

Table 6). In contrast, a non-significant increase in Funestus group IRD was observed in Cuchi (Fisher, p > 0.05;

Table 6).

3.4. Origen of Bloold Meals

A total of 106 blood-engorged

Anopheles mosquitoes were analysed to determine the origin of their blood meals (

Table 7). Among these, 18.9% had fed on humans, indicating a preference for human hosts overall.

An. funestus s.s. exhibited the highest adjusted HBI, with 78.6% in A. Neto and 57.1% in Makua, resulting in an overall adjusted HBI of 67.9%. In contrast,

An. arabiensis showed a lower adjusted HBI of 33.3%, feeding more frequently on cattle rather than on humans.

An. rufipes demonstrated no clear host preference, with an adjusted HBI of 50%. Additionally, one

An. rivulorum-like and one

An. vaneedeni specimen were analysed for host preference, but no identifiable blood meal source was detected in either case (not shown in

Table 7).

3.5. Plasmodium Falciparum Infection Rate

Head-thoraces from 250 unfed female

Anopheles mosquitoes were analyzed by ELISA for the presence of CSP (

Table 8). Among these, 23 tested positive, corresponding to an overall infection rate of 9.2% (23/250). CSP-positive mosquitoes were detected exclusively in

An. funestus s.s., which exhibited a species-specific infection rate of 9.5%. By collection site, Makua had the highest CSP infection rate at 10.2%, followed by A. Neto with 9.3%. No CSP-positive mosquitoes were detected in Cuchi. When considering only

An. funestus s.s., the infection rates were 10.5% in Makua and 9.4% in A. Neto. Before the IRS, 18

An. funestus s.s. were CSP-positive, yielding a pre-IRS IR of 10.2%. Infection rates were higher in Makua (14.0%) compared to A. Neto (8.3%), although not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p > 0.05). Following the IRS intervention, the overall IR decreased to 8.9%, representing a 12.7% reduction, however, not statistically significant (p > 0.05). In Makua, the IR dropped to 6.3%, a 55.0% reduction from pre-IRS levels, though not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Conversely, in A. Neto, the IR increased to 25.0%, representing a 201% rise compared to the pre-IRS period (

Table 9).

3.6. Detection of Knockdown Resistances

Anopheles gambiae complex mosquitoes were genotyped for the presence of the L1014F and L1014S kdr (

Table 10). In Menongue, all

An. arabiensis specimens (n = 3) were homozygous susceptible (SS) for both L1014F and L1014S alleles. In Cuchi, all 33

An. arabiensis were SS for L1014F, and five were heterozygous (RS) for L1014S. For

An. arabiensis, no homozygous resistant genotypes (RR) were detected in

An. arabiensis for either allele. The overall resistant allele frequency for L1014F in

An. arabiensis was 0.0, while the frequency for L1014S was 0.069. In contrast, all five

An. gambiae s.s. from Menongue were homozygous resistant (RR) for the L1014F allele, resulting in a resistant allele frequency of 1.0. No resistance alleles were detected for L1014S in

An. gambiae s.s.

4. Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the

Anopheles mosquito population and the impact of IRS on entomological indicators in Cuando Cubango. Our results confirm the presence of primary malaria vectors such as

An. funestus s.s.,

An. gambiae s.s., and

An. arabiensis, consistent with previous reports from Angola and other regions of sub-Saharan Africa [

4,

6,

7,

18]. In addition, we confirm the presence of

An. concolor,

An. ruarinus,

An. rufipes, and

An. squamosus [

6,

29], and report for the first time, through molecular methods, the presence of

An. leesoni,

An. rivulorum,

An. rivulorum-like, and

An. vaneedeni within the Funestus group. With the exception of

An. concolor and

An. ruarinus, all other species reported, were found naturally infected with

P. falciparum in other sub-Saharan African countries [

30,

31,

32,

33]. These findings demonstrate the need to speed the study of the role of lesser-studied species on malaria transmission in the country.

An. funestus s.s. was identified as the primary malaria vector in the study area, consistent with findings from Angola, Zambia, and Namibia [

7,

34,

35]. The absence of

An. gambiae s.s. in indoor collections, despite its detection at the larval stage, may reflect behavioral adaptations to vector control interventions such as ITNs and IRS. Shifts toward exophilic and exophagic behaviors have been reported elsewhere [

36].

Interestingly,

An. arabiensis showed a preference for feeding on cattle, highlighting the tendency of this species to feed on both humans and animals [

37]. However, due to the small sample size in this study, further research is needed to better understand the feeding preferences and host-seeking behavior of

An. arabiensis in this setting. This can be of particularly relevance as the presence of cattle can wark as zooprophylaxis [

38].

Our study confirms the fixation of the West African kdr mutation L1014F in An. gambiae s.s. from Menongue and reports the presence of the East African kdr mutation L1014S in An. arabiensis from the Cuchi district. To our knowledge, this is the first time that both West and East African kdr mutations have been investigated in this province. These findings reveal an unreported challenge in the management of insecticides of public health use and underscore the critical need for regular monitoring of insecticide resistance patterns in local vector populations.

he geographic scope of this study was limited, therefore, expanding entomological surveillance to other districts within Cuando Cubango is essential to capture spatial heterogeneity in vector populations and to better inform decision makers.

The IRS campaign achieved a coverage rate of 92.2%, protecting nearly 335,000 individuals. This level of coverage is critical, as IRS effectiveness is strongly associated with achieving at least 80% household coverage [

39]. However, some studies have shown that lower coverage levels can still produce protective effects comparable to campaigns reaching or exceeding the 80% threshold [

40,

41], Conversely, other evidence indicates that coverage below 80% may fail to generate the desired protective outcomes. This variability highlights the influence of local factors, such as transmission intensity, vector behavior, and housing conditions, on the effectiveness of IRS interventions [

41].

Community acceptance of IRS was high, with 89% of respondents supporting continued spraying and over 70% adhering to post-spray precautions. This level of engagement likely contributed to the observed reductions in vector density and infection rates, particularly in Makua. The preference for IRS over ITNs, cited by 88% of respondents, highlights the perceived value of IRS in providing long-lasting protection.

Post-IRS entomological indicators showed a significant reduction in the indoor resting density (IRD) of the Funestus group in both Makua and Agostinho Neto. Vector density also declined significantly in Agostinho Neto but not in Makua. The lack of statistically significant reductions in CSP infection rates may be attributed to several post-IRS factors, such as the short observation period (only two collection rounds), small sample sizes of mosquitoes collected and analyzed, and environmental variability, such as below-average rainfall, that may have independently suppressed mosquito populations. These limitations underscore the importance of extended surveillance periods and larger sample sizes to robustly evaluate intervention impact.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our work provides important findings on the malaria vector population and the impact of IRS on entomological indicators, essential to support decision for improve vector control mesures.

In conclusion, this study highlights the effectiveness of IRS in reducing Anopheles density and the potential for reduction on malaria transmission in Cuando Cubango.

However, the limited post-intervention data, small sample sizes, and the absence of malaria epidemiological limits the strength of conclusions regarding the impact of IRS on malaria transmission. To overcome these limitations, we recommend the implementation of a study that combines entomological and epidemiological data, enabling a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of vector control interventions. Sustained entomological surveillance and continued community engagement are essential to ensure the long-term success and adaptability of vector control strategies in the region. Further research is also needed to better understand the role of An. gambiae s.s. and potential secondary vectors from the Funestus group. The geographically limited scope of this study, expanding entomological surveillance to other districts within Cuando Cubango is critical to capture spatial vector heterogeneity to better inform national and province-wide malaria control efforts.

These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive knowledge to support evidence-based, locally tailored, and sustainable malaria vector control strategies.

It also highlights the critical importance of comprehensive species identification in mosquito surveillance to support evidence-based vector control strategies [

42].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D., An.D., G.A., and S.L.; methodology, A.D., G.A., and An.D.; formal analysis, G.A., An.D, and L.L.K; original draft preparation, A.D., G.A. and An.D.; funding acquisition, S.L. and J.F.M.; A.D., G.A. and An.D contributed equally to this work and share first authorship. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this research implemented by NMCP and The Mentor Initiative, from which this research arises, was provided by Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, serving as the primary funding agencies of the Elimination 8 Initiative program. L.L.K. is supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (SRUG2203311457)

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Health (MoH), National Malaria Control Program and the Provincial and Municipal Health authorities for their contribution and support. We acknowledge the excellence work of MoH malaria municipal supervisors and The Mentor Initiative entomological supervisors for all the support given during the field work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IRS |

Indoor Residual Spraying |

| ITN |

Insecticide Treated Nets |

| KAP |

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices |

| kdr |

Knockdown resistance |

| MI |

The Mentor Initiative |

| NMCP |

National Malaria Control Program |

| SA-DAC-MEES |

Southern Africa Development Community Malaria Elimination Eight Secretariat |

References

- World Health Organization: World Malaria Report 2024: addressing inequity in the global malaria response. , Geneva (2024).

- PNCM, DNSP: Plano Estratégico Nacional de Controlo da Malária em Angola 2021 - 2025. , Luanda (2022).

- Tavares, W.; Morais, J.; Martins, J.F.; Scalsky, R.J.; Stabler, T.C.; Medeiros, M.M.; Fortes, F.J.; Arez, A.P.; Silva, J.C. Malaria in Angola: recent progress, challenges and future opportunities using parasite demography studies. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuamba, N.; Choi, K.S.; Townson, H. Malaria vectors in Angola: distribution of species and molecular forms of the Anopheles gambiae complex, their pyrethroid insecticide knockdown resistance (kdr) status and Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite rates. Malar. J. 2006, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzetta, M.; Cani, P.J.; Di Deco, M.A.; Santolamazza, F.; della Torre, A.; Carrara, G.C.; Petrarca, V.; Fortes, F. Distribution and chromosomal characterization of the Anopheles gambiae complex in Angola. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008, 78, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, H.; Ramos, H. Research on the mosquitoes of Angola. VI - The genus Anopheles Meigen, 1818 (Diptera, Culicidae). Check-list with new records, key to the females and larvae, distribution and bioecological notes. Sep. Garcia de Orta, Sér. Zool 1975, 4, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, G.; Troco, A.D.; Seixas, G.; Pabst, R.; Francisco, A.; Pedro, C.; Garcia, L.; Martins, J.F.; Lopes, S. Molecular and entomological surveillance of malaria vectors in urban and rural communities of Benguela Province, Angola. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santolamazza, F.; Calzetta, M.; Etang, J.; Barrese, E.; Dia, I.; Caccone, A.; Donnelly, M.J.; Petrarca, V.; Simard, F.; Pinto, J.; et al. Distribution of knock-down resistance mutations in Anopheles gambiae molecular forms in west and west-central Africa. Malar. J. 2008, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.B.; Read, A.F. The threat (or not) of insecticide resistance for malaria control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 8900–8902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemingway, J.; Ranson, H. Insecticide Resistance in Insect Vectors of Human Disease. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2000, 45, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torto, B.; Tchouassi, D.P. Grand Challenges in Vector-Borne Disease Control Targeting Vectors. Front. Trop. Dis. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Malaria Control Programme Angola, The Mentor Initiative: A Rapid Assessment of Severe Malaria Case Management Practices and Constraints in Angola 2020. , Luanda (2020).

- Raman, J.; Fakudze, P.; Sikaala, C.H.; Chimumbwa, J.; Moonasar, D. Eliminating malaria from the margins of transmission in Southern Africa through the Elimination 8 Initiative. Trans. R. Soc. South Afr. 2021, 76, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE): Resultados Definitivos do Recenseamento Geral da População e da Habitação 2014. , Luanda (2016).

- Mendelsohn, J. The Angolan Catchments of Northern Botswana’s Major Rivers: The Cubango, Cuito, Cuando and Zambezi Rivers. World Geomorphological Landscapes. 15–36 (2022). [CrossRef]

- SADC-MEES: Harmonized SADC Elimination Eight regional trainers of trainers guide for indoor residual spraying. , Luanda (2019).

- Ribeiro, H., Ramos, H.D.: Guia ilustrado para a identificação dos mosquitos de Angola (Diptera. Culicidae). Boletim da Sociedade Portuguesa de Entomologia, Lisboa (1995).

- Coetzee, M. Key to the females of Afrotropical Anopheles mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar. J. 2020, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koekemoer, L.L.; Kamau, L.; Hunt, R.H.; Coetzee, M. A cocktail polymerase chain reaction assay to identify members of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002, 66, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanello, C.; Santolamazza, F.; Della Torre, A. Simultaneous identification of species and molecular forms of the Anopheles gambiae complex by PCR-RFLP. Med Veter- Èntomol. 2002, 16, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.A.; Brogdon, W.G.; Collins, F.H. Identification of Single Specimens of the Anopheles Gambiae Complex by the Polymerase Chain Reaction. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993, 49, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohuet, A.; Simard, F.; Toto, J.-C.; Kengne, P.; Coetzee, M.; Fontenille, D. Species identification within the Anopheles funestus group of malaria vectors in Cameroon and evidence for a new species. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 69, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, R.A.; Zavala, F.; Charoenvit, Y.; Campbell, G.H.; Burkot, T.R.; Schneider, I.; Esser, K.M.; Beaudoin, R.L.; Andre, R.G. Comparative testing of monoclonal antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites for ELISA development. Bull World Health Organ. 1987, 65, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Durnez, L.; Van Bortel, W.; Denis, L.; Roelants, P.; Veracx, A.; Trung, H.D.; Sochantha, T.; Coosemans, M. False positive circumsporozoite protein ELISA: a challenge for the estimation of the entomological inoculation rate of malaria and for vector incrimination. Malar. J. 2011, 10, 195–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, C.; Nikou, D.; Donnelly, M.J.; Williamson, M.S.; Ranson, H.; Ball, A.; Vontas, J.; Field, L.M. Detection of knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations in Anopheles gambiae: a comparison of two new high-throughput assays with existing methods. Malar. J. 2007, 6, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Torres, D.; Chandre, F.; Williamson, M.S.; Darriet, F.; Bergé, J.B.; Devonshire, A.L.; Guillet, P.; Pasteur, N.; Pauron, D. Molecular characterization of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol. Biol. 1998, 7, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranson, H.; Jensen, B.; Vulule, J.M.; Wang, X.; Hemingway, J.; Collins, F.H. Identification of a point mutation in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Kenyan Anopheles gambiae associated with resistance to DDT and pyrethroids. Insect Mol. Biol. 2000, 9, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, V.; Reddy, M.; Overgaard, H.J.; Abaga, S.; Caccone, A. Estimation of the Human Blood Index in Malaria Mosquito Vectors in Equatorial Guinea after Indoor Antivector Interventions. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 84, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, H., Ramos, H.D.: Guia ilustrado para a identificação dos mosquitos de Angola (Diptera. Culicidae). Boletim da Sociedade Portuguesa de Entomologia, Lisboa (1995).

- Burke, A.; Dandalo, L.; Munhenga, G.; Dahan-Moss, Y.; Mbokazi, F.; Ngxongo, S.; Coetzee, M.; Koekemoer, L.; Brooke, B. A new malaria vector mosquito in South Africa. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep43779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopya, E.; Ndo, C.; Djamouko-Djonkam, L.; Nkahe, L.; Awono-Ambene, P.; Njiokou, F.; Wondji, C.S.; Antonio-Nkondjio, C. Anopheles leesoni Evans 1931, a Member of the Anopheles funestus Group, Is a Potential Malaria Vector in Cameroon. Adv. Èntomol. 2022, 10, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawada, H.; Dida, G.O.; Sonye, G.; Njenga, S.M.; Mwandawiro, C.; Minakawa, N. Reconsideration of Anopheles rivulorum as a vector of Plasmodium falciparum in western Kenya: Some evidence from biting time, blood preference, sporozoite positive rate, and pyrethroid resistance. Parasit Vectors 2012, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkes, T.J.; Matola, Y.G.; Charlwood, J.D. Anopheles rivulorum, a vector of human malaria in Africa. Med Veter- Èntomol. 1996, 10, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwema, T.; Lukubwe, O.; Joseph, R.; Maliti, D.; Iitula, I.; Katokele, S.; Uusiku, P.; Walusimbi, D.; Ogoma, S.B.; Tambo, M.; et al. Human and vector behaviors determine exposure to Anopheles in Namibia. Parasites Vectors 2022, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Muleba, M.; Stevenson, J.C.; Norris, D.E. Habitat Partitioning of Malaria Vectors in Nchelenge District, Zambia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 1234–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takken, W.; Charlwood, D.; Lindsay, S.W. The behaviour of adult Anopheles gambiae, sub-Saharan Africa’s principal malaria vector, and its relevance to malaria control: a review. Malar. J. 2024, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limwagu, A.J.; Msugupakulya, B.J.; Ngowo, H.S.; Mwalugelo, Y.A.; Kilalangongono, M.S.; Samli, F.A.; Abbasi, S.K.; Okumu, F.O.; Ngasala, B.E.; Lyimo, I.N.; et al. The bionomics of Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles funestus inside local houses and their implications for vector control strategies in areas with high coverage of insecticide-treated nets in South-eastern Tanzania. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0295482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahande, A.; Mosha, F.; Mahande, J.; Kweka, E. Feeding and resting behaviour of malaria vector, Anopheles arabiensis with reference to zooprophylaxis. Malar. J. 2007, 6, 100–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO: Indoor residual spraying: an operational manual for indoor residual spraying for malaria transmission control and elimination. , Genenve (2015).

- García, G.; Hergott, D.; Galick, D.; Donfack, O.T.; Vaz, L.M.; Nchama, L.N.; Eyono, J.M.; Avue, R.N.; Rivas, M.R.; Iyanga, M.; et al. Testing indoor residual spraying coverage targets for malaria control, Bioko, Equatorial Guinea. Bull. World Heal. Organ. 2025, 103, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galick, D.S.; Vaz, L.M.; Ondo, L.; Iyanga, M.M.; Bikie, F.E.E.; Avue, R.M.N.; Donfack, O.T.; Eyono, J.N.M.; Mifumu, T.A.O.; Hergott, D.E.B.; et al. Reconsidering indoor residual spraying coverage targets: A retrospective analysis of high-resolution programmatic malaria control data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2025, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlank, E.; Koekemoer, L.L.; Coetzee, M. The importance of morphological identification of African anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) for malaria control programmes. Malar. J. 2018, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).