Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

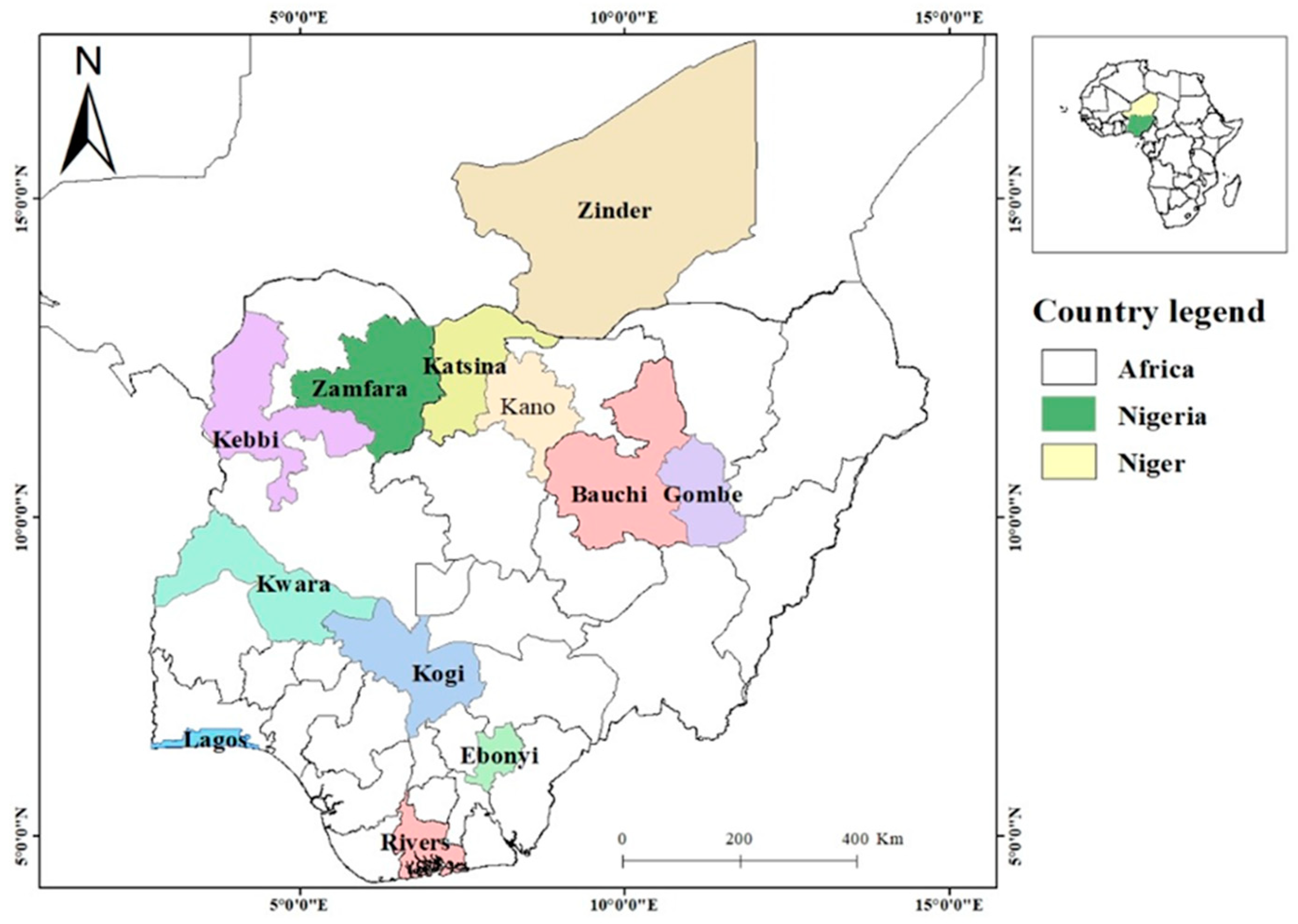

2.1. Collection of Anopheles mosquitoes Along Gradient of Increasing Aridity

2.2. Morphological and Molecular Identification of Anopheles Mosquitoes to Species Level

2.3. Investigation of Spatial Distribution of MB Infection in Anopheles Mosquitoes

2.4. Investigation of the Modulation of Insecticide Resistance by MB

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

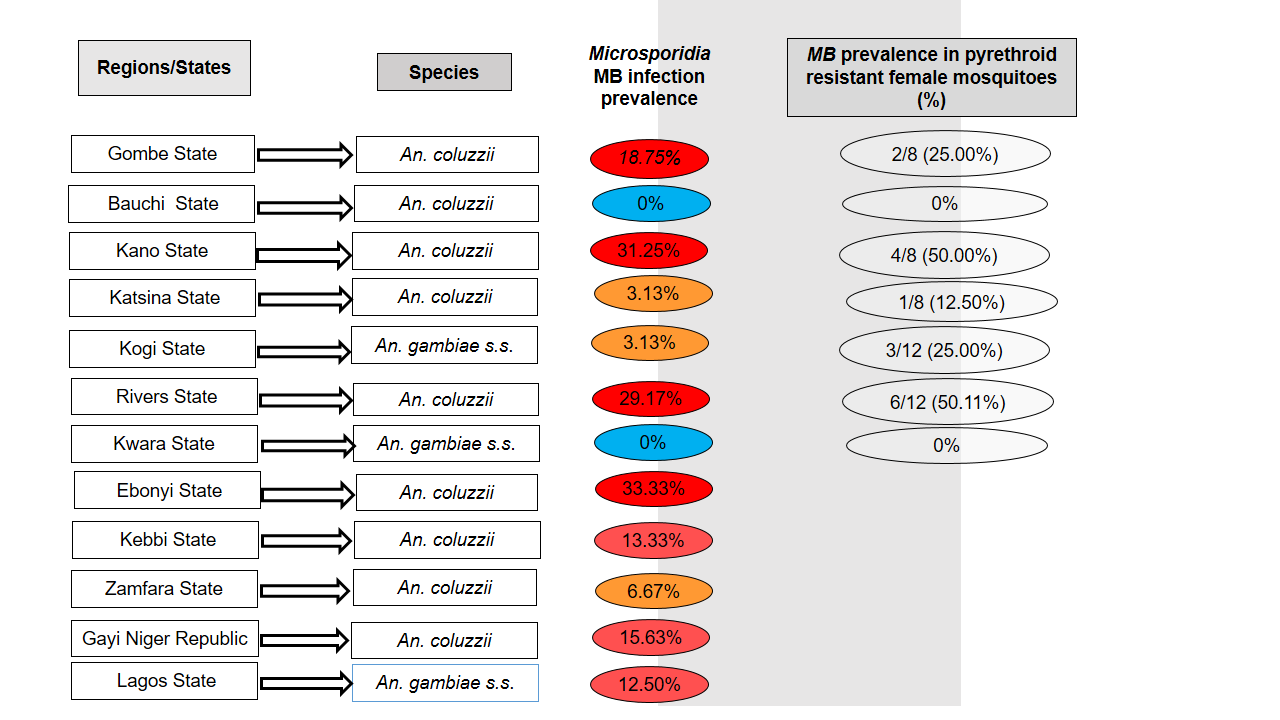

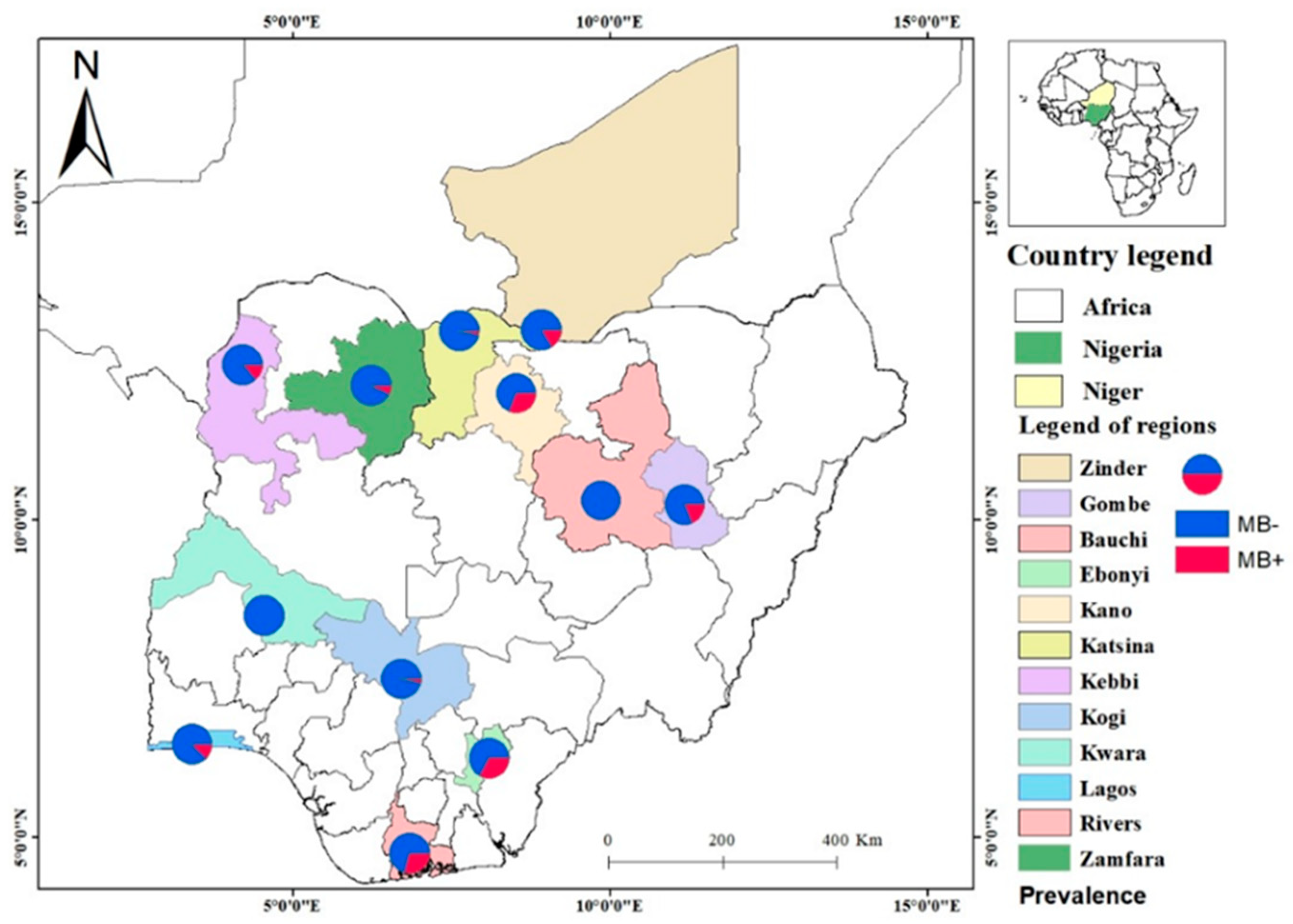

3.1. MB Infects Anopheles Mosquitoes from Contrasting Ecological Settings Along Clinal Gradient

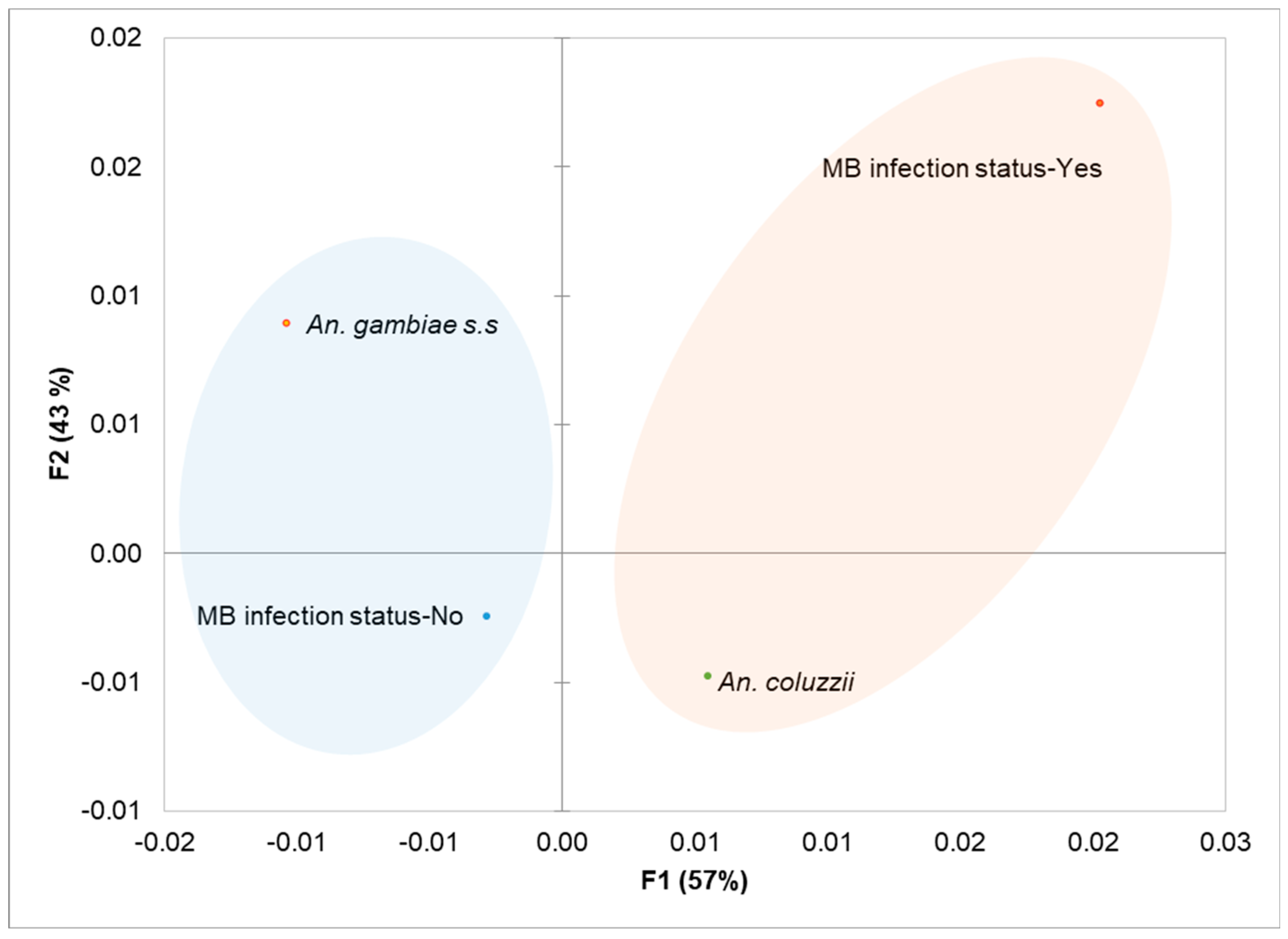

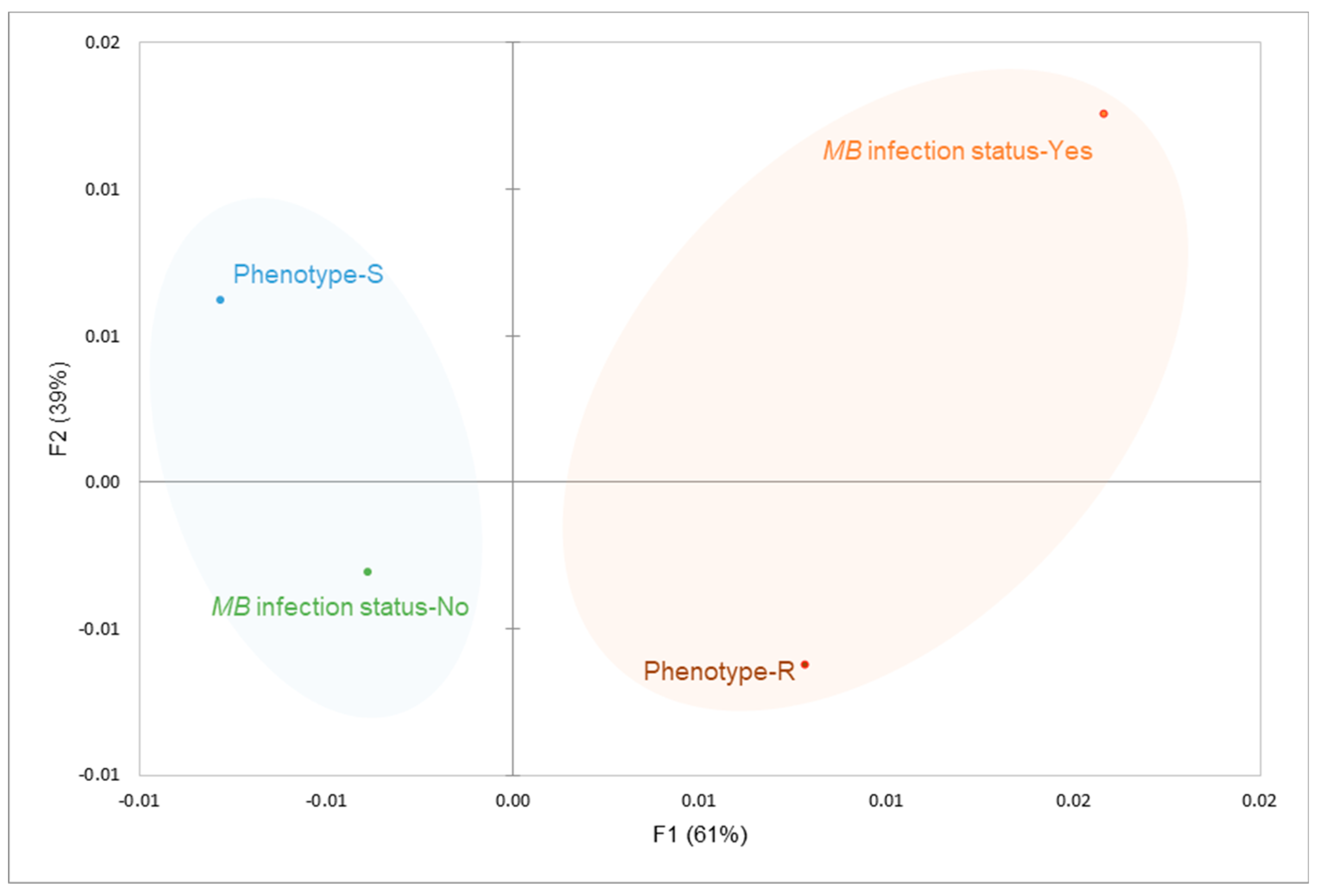

3.2. MB Infection Probably Correlates with Pyrethroid Resistance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO World Malaria Report 2024: Addressing Inequity in the Global Malaria Response. 2024.

- National Institute of Statistics Statistical Directories. National health information system, 2023.

- Ibrahim, S.S.; Mukhtar, M.M.; Irving, H.; Riveron, J.M.; Fadel, A.N.; Tchapga, W.; Hearn, J.; Muhammad, A.; Sarkinfada, F.; Wondji, C.S. Exploring the Mechanisms of Multiple Insecticide Resistance in a Highly Plasmodium-Infected Malaria Vector Anopheles Funestus Sensu Stricto from Sahel of Northern Nigeria. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.S.; Mukhtar, M.M.; Datti, J.A.; Irving, H.; Kusimo, M.O.; Tchapga, W.; Lawal, N.; Sambo, F.I.; Wondji, C.S. Temporal Escalation of Pyrethroid Resistance in the Major Malaria Vector Anopheles Coluzzii from Sahelo-Sudanian Region of Northern Nigeria. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.S.; Manu, Y.A.; Tukur, Z.; Irving, H.; Wondji, C.S. High Frequency of Kdr L1014F Is Associated with Pyrethroid Resistance in Anopheles Coluzzii in Sudan Savannah of Northern Nigeria. BMC Infect Dis 2014, 14, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamidi, T.B.; Alo, E.B.; Naphtali, R. Distribution and Abundance of Anopheles Mosquito Species in Three Selected Areas of Taraba State, North-Eastern Nigeria. Animal Research International 2017, 14, 2730–2740. [Google Scholar]

- Moustapha, L.M.; Sadou, I.M.; Arzika, I.I.; Maman, L.I.; Gomgnimbou, M.K.; Konkobo, M.; Diabate, A.; Bilgo, E. First Identification of Microsporidia MB in Anopheles Coluzzii from Zinder City, Niger. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduola, A.O.; Adelaja, O.J.; Aiyegbusi, Z.O.; Tola, M.; Obembe, A.; Ande, A.T.; Awolola, S. Dynamics of Anopheline Vector Species Composition and Reported Malaria Cases during Rain and Dry Seasons in Two Selected Communities of Kwara State. Nig. J. Para. 2016, 37, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenezer, A.; Okiwelu, S.; Agi, P.; Noutcha, Ma.E.; Awolola, T.; Oduola, A. Species Composition of the Anopheles Gambiae Complex across Eco-Vegetational Zones in Bayelsa State, Niger Delta Region, Nigeria. J Vector Borne Dis 2012, 49, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, H.S.; TagEldin, R.A.; Fahmy, N.T.; Diclaro, J.W.; Alaribe, A.A.; Ezedinachi, E.; Nwachuku, N.S.; Odey, F.O.; Arimoto, H. Spatial Distribution of PCR-Identified Species of Anopheles Gambiae Senu Lato (Diptera: Culicidae) Across Three Eco-Vegetational Zones in Cross River State, Nigeria. Journal of Medical Entomology 2022, 59, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeogun, A.; Babalola, A.S.; Okoko, O.O.; Oyeniyi, T.; Omotayo, A.; Izekor, R.T.; Adetunji, O.; Olakiigbe, A.; Olagundoye, O.; Adeleke, M.; et al. Spatial Distribution and Ecological Niche Modeling of Geographical Spread of Anopheles Gambiae Complex in Nigeria Using Real Time Data. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 13679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamane Sale, N.; Zamanka Naroua, H.; Zoulkifouly Hounkarin, W.; Labbo, R.; Maman Laminou, I.; Djibo Souley, A.; Soumana, A.; Issa Arzika, I.; Jambou, R.; Doumma, A. Influence of environmental factors on the abundance of anopheles in the different agroecosystems of the city of Niamey. IJAR 2023, 11, 01–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.S.; Mukhtar, M.M.; Irving, H.; Labbo, R.; Kusimo, M.O.; Mahamadou, I.; Wondji, C.S. High Plasmodium Infection and Multiple Insecticide Resistance in a Major Malaria Vector Anopheles Coluzzii from Sahel of Niger Republic. Malar J 2019, 18, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oduola, A.O.; Obembe, A.; Lateef, S.A.; Abdulbaki, M.K.; Kehinde, E.A.; Adelaja, O.J.; Shittu, O.; Tola, M.; Oyeniyi, T.A.; Awolola, T.S. Species Composition and Plasmodium Falciparum Infection Rates of Anopheles Gambiae s.l. Mosquitoes in Six Localities of Kwara State, North Central, Nigeria. jasem 2022, 25, 1801–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, M.N.; Moustapha, L.M.; Sow, D.; Karimoun, A.; Issa, I.; Sanoussi, M.K.; Diallo, M.A.; Doutchi, M.; Diongue, K.; Ibrahim, M.L.; et al. Circulation of Non-Falciparum Species in Niger: Implications for Malaria Diagnosis. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2024, ofae474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiga, A.-A.; Sombié, A.; Zanré, N.; Yaméogo, F.; Iro, S.; Testa, J.; Sanon, A.; Koita, O.; Kanuka, H.; McCall, P.J.; et al. First Report of V1016I, F1534C and V410L Kdr Mutations Associated with Pyrethroid Resistance in Aedes Aegypti Populations from Niamey, Niger. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamane Salé, N.; Labbo, R.; Laminou, I.M.; Issa Arzika, I.; Djibo Souley, A.; Zoulkifouly Hounkarin, W.; Zamanka Naroua, H.; Soumana, A.; Maiga, A.-A.; Jambou, R.; et al. Insecticide Resistance in Anopheles Gambiae Sensu Lato (Diptera: Culicidae) across Different Agroecosystems in Niamey, Niger. AJTER 2024, 3, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumaila, H.; Hamani, B.; Arzika, I.I.; Soumana, A.; Daouda, A.; Daouda, F.A.; Iro, S.M.; Gouro, S.; Zaman-Allah, M.S.; Mahamadou, I.; et al. Countrywide Insecticide Resistance Monitoring and First Report of the Presence of the L1014S Knock down Resistance in Niger, West Africa. Malar J 2022, 21, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumaila, H.; Idrissa, M.; Akgobeto, M.; Habi, G.; Jackou, H.; Sabiti, I.; Abdoulaye, A.; Daouda, A.; Souleymane, I.; Osse, R. Multiple Mechanisms of Resistance to Pyrethroids in Anopheles Gambiae s. l Populations in Niger. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses 2017, 47, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busari, L.O.; Raheem, H.O.; Iwalewa, Z.O.; Fasasi, K.A.; Adeleke, M.A. Investigating Insecticide Susceptibility Status of Adult Mosquitoes against Some Class of Insecticides in Osogbo Metropolis, Osun State, Nigeria. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0285605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuekezie, O.; Nwosu, E.; Nwangwu, U.; Dogunro, F.; Onwude, C.; Agashi, N.; Ezihe, E.; Anioke, C.; Anokwu, S.; Eloy, E.; et al. Resistance Status of Anopheles Gambiae (s. l.) to Four Commonly Used Insecticides for Malaria Vector Control in South-East Nigeria. Parasit Vectors 2020, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; Ibrahim, S.S.; Mukhtar, M.M.; Irving, H.; Abajue, M.C.; Edith, N.M.A.; Da’u, S.S.; Paine, M.J.I.; Wondji, C.S. High Pyrethroid/DDT Resistance in Major Malaria Vector Anopheles Coluzzii from Niger-Delta of Nigeria Is Probably Driven by Metabolic Resistance Mechanisms. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0247944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojianwuna, C.C.; Enwemiwe, V.N.; Esiwo, E.; Mekunye, F.; Anidiobi, A.; Oborayiruvbe, T.E. Susceptibility Status and Synergistic Activity of DDT and Lambda-Cyhalothrin on Anopheles Gambiae and Aedes Aegypti in Delta State, Nigeria. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0309199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omotayo, A.I.; Ande, A.T.; Oduola, A.O.; Adelaja, O.J.; Adesalu, O.; Jimoh, T.R.; Ghazali, A.I.; Awolola, S.T. Multiple Insecticide Resistance Mechanisms in Urban Population of Anopheles Coluzzii (Diptera: Culicidae) from Lagos, South-West Nigeria. Acta Trop 2022, 227, 106291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.S.; Muhammad, A.; Hearn, J.; Weedall, G.D.; Nagi, S.C.; Mukhtar, M.M.; Fadel, A.N.; Mugenzi, L.J.; Patterson, E.I.; Irving, H.; et al. Molecular Drivers of Insecticide Resistance in the Sahelo-Sudanian Populations of a Major Malaria Vector Anopheles Coluzzii. BMC Biol 2023, 21, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awolola, T.S.; Adeogun, A.; Olakiigbe, A.K.; Oyeniyi, T.; Olukosi, Y.A.; Okoh, H.; Arowolo, T.; Akila, J.; Oduola, A.; Amajoh, C.N. Pyrethroids Resistance Intensity and Resistance Mechanisms in Anopheles Gambiae from Malaria Vector Surveillance Sites in Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, N.; Sheth, M.; Liebman, K.; Pinto, J.; Lenhart, A. Whole Metagenome Sequencing Reveals Links between Mosquito Microbiota and Insecticide Resistance in Malaria Vectors. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herren, J.K.; Mbaisi, L.; Mararo, E.; Makhulu, E.E.; Mobegi, V.A.; Butungi, H.; Mancini, M.V.; Oundo, J.W.; Teal, E.T.; Pinaud, S.; et al. A Microsporidian Impairs Plasmodium Falciparum Transmission in Anopheles Arabiensis Mosquitoes. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattoh, G.; Maina, T.; Makhulu, E.E.; Mbaisi, L.; Mararo, E.; Otieno, F.G.; Bukhari, T.; Onchuru, T.O.; Teal, E.; Paredes, J.; et al. Horizontal Transmission of the Symbiont Microsporidia MB in Anopheles Arabiensis. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 647183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhulu, E.E.; Onchuru, T.O.; Gichuhi, J.; Otieno, F.G.; Wairimu, A.W.; Muthoni, J.N.; Koekemoer, L.; Herren, J.K. Localization and Tissue Tropism of the Symbiont Microsporidia MB in the Germ Line and Somatic Tissues of Anopheles Arabiensis. mBio 2024, 15, e02192-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akorli, J.; Akorli, E.A.; Tetteh, S.N.A.; Amlalo, G.K.; Opoku, M.; Pwalia, R.; Adimazoya, M.; Atibilla, D.; Pi-Bansa, S.; Chabi, J.; et al. Microsporidia MB Is Found Predominantly Associated with Anopheles Gambiae s. s and Anopheles Coluzzii in Ghana. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 18658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahouandjinou, M.J.; Sovi, A.; Sidick, A.; Sewadé, W.; Koukpo, C.Z.; Chitou, S.; Towakinou, L.; Adjottin, B.; Hougbe, S.; Tokponnon, F.; et al. First Report of Natural Infection of Anopheles Gambiae s. s. and Anopheles Coluzzii by Wolbachia and Microsporidia in Benin: A Cross-Sectional Study. Malar J 2024, 23, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, T.; Pevsner, R.; Herren, J. Keith. Microsporidia: A Promising Vector Control Tool for Residual Malaria Transmission. Front. Trop. Dis 2022, 3, 957109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M. Key to the Females of Afrotropical Anopheles Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar J 2020, 19, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santolamazza, F.; Mancini, E.; Simard, F.; Qi, Y.; Tu, Z.; della Torre, A. Insertion Polymorphisms of SINE200 Retrotransposons within Speciation Islands of Anopheles Gambiae Molecular Forms. Malaria Journal 2008, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J. Organization and Mapping of a Sequence on the DROSOPHILA MELANOGASTER X and Y Chromosomes That Is Transcribed during Spermatogenesis. Genetics 1984, 107, 611–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Standard Operating Procedure for Testing Insecticide Susceptibility of Adult Mosquitoes in WHO Tube Tests. 2022.

- Lumivero XLSTAT | Logiciel statistique pour Excel Available online: https://www.xlstat.com/fr/.

- Nattoh, G.; Onyango, B.; Makhulu, E.E.; Omoke, D.; Ang’ang’o, L.M.; Kamau, L.; Gesuge, M.M.; Ochomo, E.; Herren, J.K. Microsporidia MB in the Primary Malaria Vector Anopheles Gambiae Sensu Stricto Is Avirulent and Undergoes Maternal and Horizontal Transmission. Parasites & Vectors 2023, 16, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akorli, E.A.; Nana Efua, A.; Egyirifa, R.K.; Dorcoo, C.; Otoo, S.; Tetteh, S.N.A.; Pul, R.M.; Derrick, B.S.; Oware, S.K.D.; Samuel, K.D.; et al. Breeding Water Parameters Are Important Determinants of Microsporidia MB Prevalence in the Aquatic Stages of Anopheles Mosquitoes. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Omoke, D.; Kipsum, M.; Otieno, S.; Esalimba, E.; Sheth, M.; Lenhart, A.; Njeru, E.M.; Ochomo, E.; Dada, N. Western Kenyan Anopheles Gambiae Showing Intense Permethrin Resistance Harbour Distinct Microbiota. Malaria Journal 2021, 20, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelloquin, B.; Kristan, M.; Edi, C.; Meiwald, A.; Clark, E.; Jeffries, C.L.; Walker, T.; Dada, N.; Messenger, L.A. Overabundance of Asaia and Serratia Bacteria Is Associated with Deltamethrin Insecticide Susceptibility in Anopheles Coluzzii from Agboville, Côte d’Ivoire. Microbiology Spectrum 2021, 9, e00157-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boanyah, G.Y.; Koekemoer, L.L.; Herren, J.K.; Bukhari, T. Effect of Microsporidia MB Infection on the Development and Fitness of Anopheles Arabiensis under Different Diet Regimes. Parasites & Vectors 2024, 17, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otieno, F.G.; Barreaux, P.; Belvinos, A.S.; Makhulu, E.E.; Onchuru, T.O.; Wairimu, A.W.; Omboye, S.M.; King’ori, C.N.; Mawuko, S.B.; Kebira, A.N.; et al. Temperature Modulates the Dissemination Potential of Microsporidia MB, a Malaria-Blocking Endosymbiont of Anopheles Mosquitoes 2024, 2024.11.15.623820.

| Locality | n | Species | Bioassay | Ecological setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F0 Parents caught indoor using Prokopack aspirators | ||||

| Gayi Niger, Magaria | 32 | An. coluzzii | - | Sahel |

| Gajerar Giwa, Katsina State | 32 | An. coluzzii | Sahel | |

| Gaa-Bolorunduro, Kwara State | 15 | An. gambiae s.s. | - | Guinea Savanna |

| Zariagi, Lokoja, Kogi State | 32 | An. gambiae s.s. | - | Guinea Savanna |

| Gotomo, Kebbi State | 15 | An. coluzzii | - | Sudan Savanna |

| Tsunami, Gusau, Zamfara State | 15 | An. coluzzii | - | Sudan Savanna |

| Ugalaba, Ezza North, Ebonyi State | 15 | An. coluzzii | - | Tropical Rainforest |

| Obio/Akpor LGA, Rivers State | 24 | An. coluzzii | - | Mangrove Swamp |

| Badagry, Lagos State | 24 | An. gambiae s.s. | - | Mangrove Swamp |

| F1 progenies used for bioassays | ||||

| Gajerar Giwa, Katsina State | 16 | An. coluzzii | Permethrin | Sahel |

| Dadin Kowa, Gombe State | 16 | An. coluzzii | Deltamethrin | Guinea Savanna |

| Zariagi, Lokoja, Kogi State | 24 | An. gambiae s.s. | Deltamethrin | Guinea Savana |

| Gamjin Bappa, Karaye, Kano State | 16 | An. coluzzii | Deltamethrin | Guinea Savana |

| Gadau, Bauchi State | 16 | An. coluzzii | Deltamethrin | Sudan Savanna |

| Obio/Akpor LGA, Rivers State | 24 | An. coluzzii | Permethrin | Mangrove Swamp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).