1. Introduction

Understanding vector dynamics in disease transmission is crucial for designing effective vector control interventions against malaria. In Ethiopia, about 47

Anopheles species have been documented [

1,

2]. The primary vector of malaria is the

Anopheles arabiensis, while

An. pharoensis, An. funestus, An. coustani complex, and

An. nili are secondary vectors [

2]. Recently, the Asian malaria vector

Anopheles stephensi, a competent vector of both

P. falciparum and

P. vivax, invaded East African region [

3,

4,

5], complicating the existing malaria vectorial system.

Different malaria vector species exhibit varying blood meal preferences, influenced by host availability. Some are anthropophilic (preferring humans), others are zoophilic (preferring animals), or opportunistic (preferring both) [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. These feeding preferences play a critical role in malaria transmission dynamics. Anthropophilic vectors present the highest risk because of their tendency to frequently feed on humans. Both

An. arabiensis and

An. pharoensis are considered an opportunistic feeder in Ethiopia [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Anopheles stephensi, on the other hand, is predominantly documented with zoophilic affinity [

16,

17].

In Africa, malaria transmission is facilitated by multiple

Anopheles species, each exhibiting different vectorial capacities and behaviours [

6]. In recent years, changes in vector dynamics have been documented in south and east Africa. For instance, Mustapha et al. [2021] indicated that secondary vectors may contribute substantially to malaria transmission because of their high densities and

Plasmodium-positivity rate in Kenya [

18]. This informs that in settings with multiple malaria vectors, continuous monitoring of their vectorial role is essential to understand the role of diverse vector species in malaria transmission and design control measures accordingly.

Hawassa City, the largest city in southern Ethiopia, is endemic to malaria with both

P. falciparum and

P. vivax prevalent [

19,

20]. The city has recently experienced an increase in malaria cases and incidence to epidemic level. Multiple malaria vectors have been reported in the area including

An.

stephensi, An. arabiensis, An. pharoensis, and

An. coustani [

19]. However, the role of diverse vector species in local malaria transmission has not yet been defined.

This study aims to identify the blood meal sources and sporozoite infection rates of Anopheles mosquitoes in Hawassa City, Ethiopia. Better understanding of vectorial characteristics helps guide the development of comprehensive control strategies and prevent recurrent outbreaks.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Period

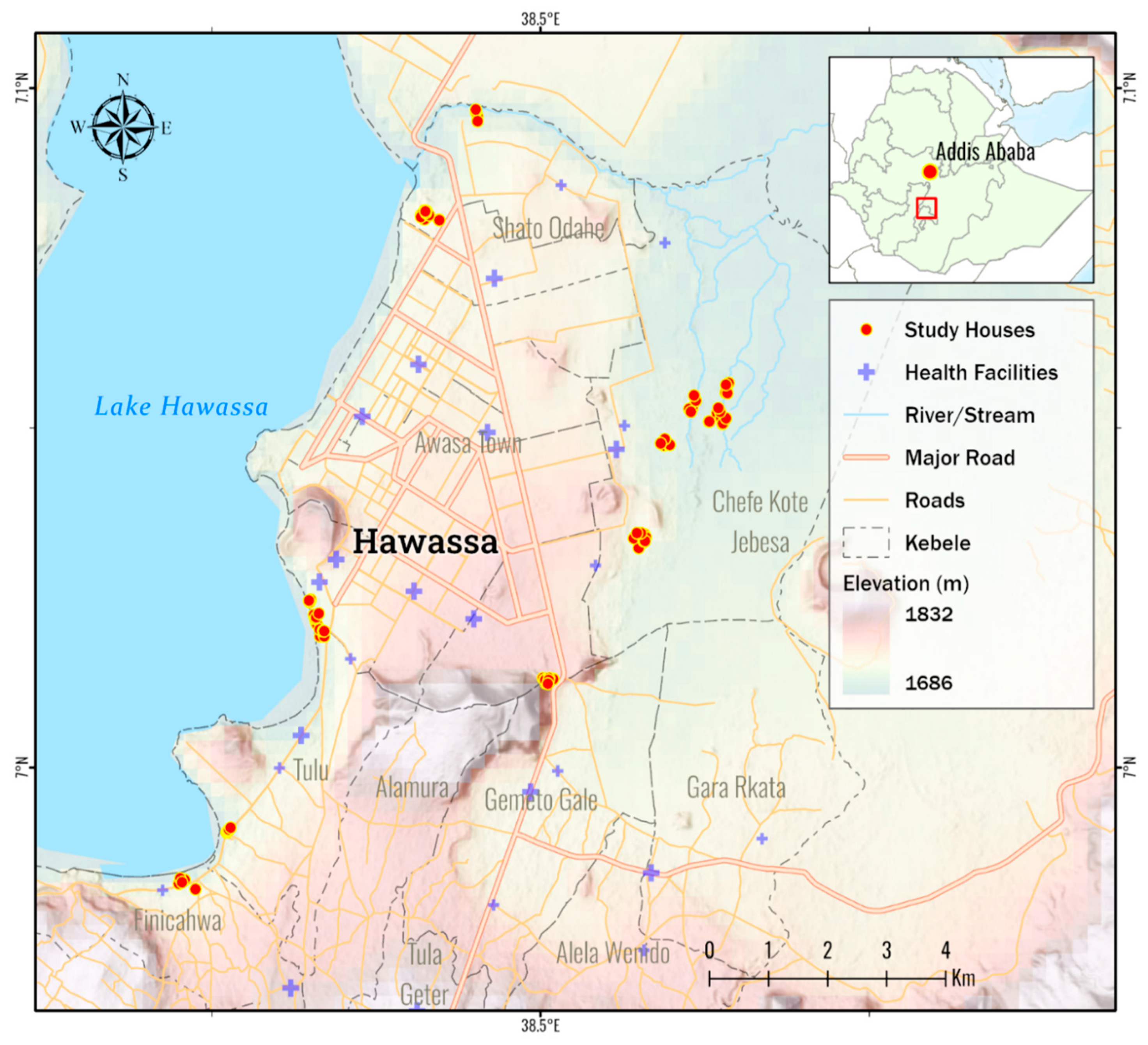

A targeted entomological survey was conducted from January 2023 to April 2023 in Hawassa City, 275 km from the Capital Addis Ababa in Southern Ethiopia (

Figure 1). The Study setting was described elsewhere [

19]. For vector surveillance, malarious villages (

kebeles) were selected based on the report of the Hawassa City’s Health Department [

20].

2.2. Mosquito Survey

Three mosquito surveillance tools were employed to collect adult mosquitoes: CDC Light Traps (Model: John W. Hock CDC Light Trap 512, Gainesville, Florida, USA); Bioagents (BG-pro) Traps with attractant lure (Biogents AG, Regensburg, Germany); and Prokopack Aspirator (John W. Hock 1418, Gainesville, Florida, USA).

Indoor mosquito collections with CDC Light Trap and BG-Pro were conducted overnight from 18:00 to 06:00, with traps suspended 1.5 meters above the ground near sleeping areas. For the outdoor sampling, traps were set within 5-meter away from houses. A total of 180 and 120 trap-nights were set with BG-Pro and CDC Light traps, respectively. In addition, Prokopack Aspirator was used to sample indoor resting mosquitoes in the morning between 6:30 and 8:00 in 60 randomly selected houses.

2.3. Mosquito Specimen Processing

Collected mosquito specimens were brought to the Malaria Research Laboratory at Hawassa University for species identification. Live mosquitoes were euthanized using chloroform. The mosquitoes were then emptied into a petridish and sorted into culicines and anophelines. Culicines were counted, recorded, and discarded, while all

Anopheles mosquitoes were further sorted out to species using a morphological key [

21]. The abdominal status of each specimen was also assessed and categorized as unfed, fed, half-gravid, or gravid. Each female

Anopheles mosquito was individually kept in labelled Eppendorf tubes for further molecular analysis.

2.4. Mosquito DNA Extraction

The head-thoracic part of each female adult mosquito was dissected for DNA extraction. DNA extraction was performed following the established automated DNA extraction protocol outlined by Zhong et al. [

22]. Briefly, DNA extraction utilized the QIAamp 96 DNA QIAcube HT kit with a QIAcube HT 96 automated nucleic acid purification robot (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), following the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modifications. Specifically, each sample was ground in a ZR Bashing Bead Lysis tube (2.0 mm beads, Zymo Research Corporation, Irvine, USA) and homogenized in 200 μl of lysis solution containing 20 µl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml) using the TissueLyser II system (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for 10 minutes at 30 Hz. The genomic DNA was eluted in a final volume of 100 µl for the head-thoracic portion and 200 µl for the abdominal portion. The DNA extracted from the head-thoracic portion was used for detecting

Plasmodium sporozoites, while the DNA from the abdominal portion was used for species and bloodmeal identification [

22].

2.5. Molecular Genotyping of Species, Bloodmeal, and Parasite Infections

For confirmation,

An. stephensi and

An. arabiensis was screened by PCR using a previously established protocol [

19,

23]. PCR reactions were carried out in a total volume of 17 μl, containing 1 μl of DNA template, 5 pmol of each primer, and 8.5 μl of DreamTaq Green PCR Master Mix (2X) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The thermocycling protocol involved an initial activation step of 3 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 amplification cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C, with a final extension step of 6 min at 72 °C. Other

Anopheles species were identified through DNA sequencing of the ITS2 region of nuclear ribosomal DNA, following the methods described by Zhong et al. [

22].

Mosquito blood meal sources (humans, cows, pigs, goats, and dogs) were examined using qPCR using previously established protocols [

23,

24,

25].

Plasmodium infections (

Plasmodium falciparum,

Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, and

Plasmodium ovale) in mosquitoes were examined by qPCR detection using established protocols [

26,

27,

28]. Multiplexed qPCR was performed on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA) in a final volume of 12 µl, including 2 µl of sample DNA, 6 µl of PerfeCTa qPCR ToughMix, Low ROX Master Mix (2X) (Quantabio, Beverly, MA), 0.5 µl of each probe (2 µM), and 0.4 µl of each forward primer (10 µM) and reverse primer (10 µM). The temperature profile involved a hold stage at 50 °C for 2 min and 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 45 cycles of PCR amplification at 95 °C for 3 s and 60 °C for 30 s.

2.6. Data Analysis

Mosquito density was calculated as the mean number of mosquitoes caught per trap – night for each trap type.

Anopheles species density difference across traps was compared using independent Samples Kruskal-Wallis Test.

Plasmodium sporozoite infection rate was calculated as the proportion of mosquitoes infected with

Plasmodium against those tested. Entomological inoculation rates (EIR) was estimated by multiplying the sporozoite rate by man-biting rate; Man-biting rates were derived from traps catches (i.e., density divided by a conversion factor 1.605 [

29]). The human blood index (HBI) and bovine blood index (BBI) were calculated as the proportion of fed mosquitoes that fed on human and bovine blood meals, respectively [

8,

30,

31]. Mixed blood meals (human + bovine) were included in the counts for both HBI and BBI. All data was analysed using Microsoft Excel (Version 2016, Microsoft Corp, USA) and IBM SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Hawassa University. Mosquito collections from each household were conducted after obtaining verbal consent from the household head.

3. Results

3.1. Anopheles Density

A total of 738 female

Anopheles mosquitoes were collected during the study period.

Anopheles arabiensis was the predominant species, accounting for 72.9% (n=538) of the collections, followed by

An. pharoensis, 13.4% (n=99),

An. stephensi, 7.5% (n=55), and

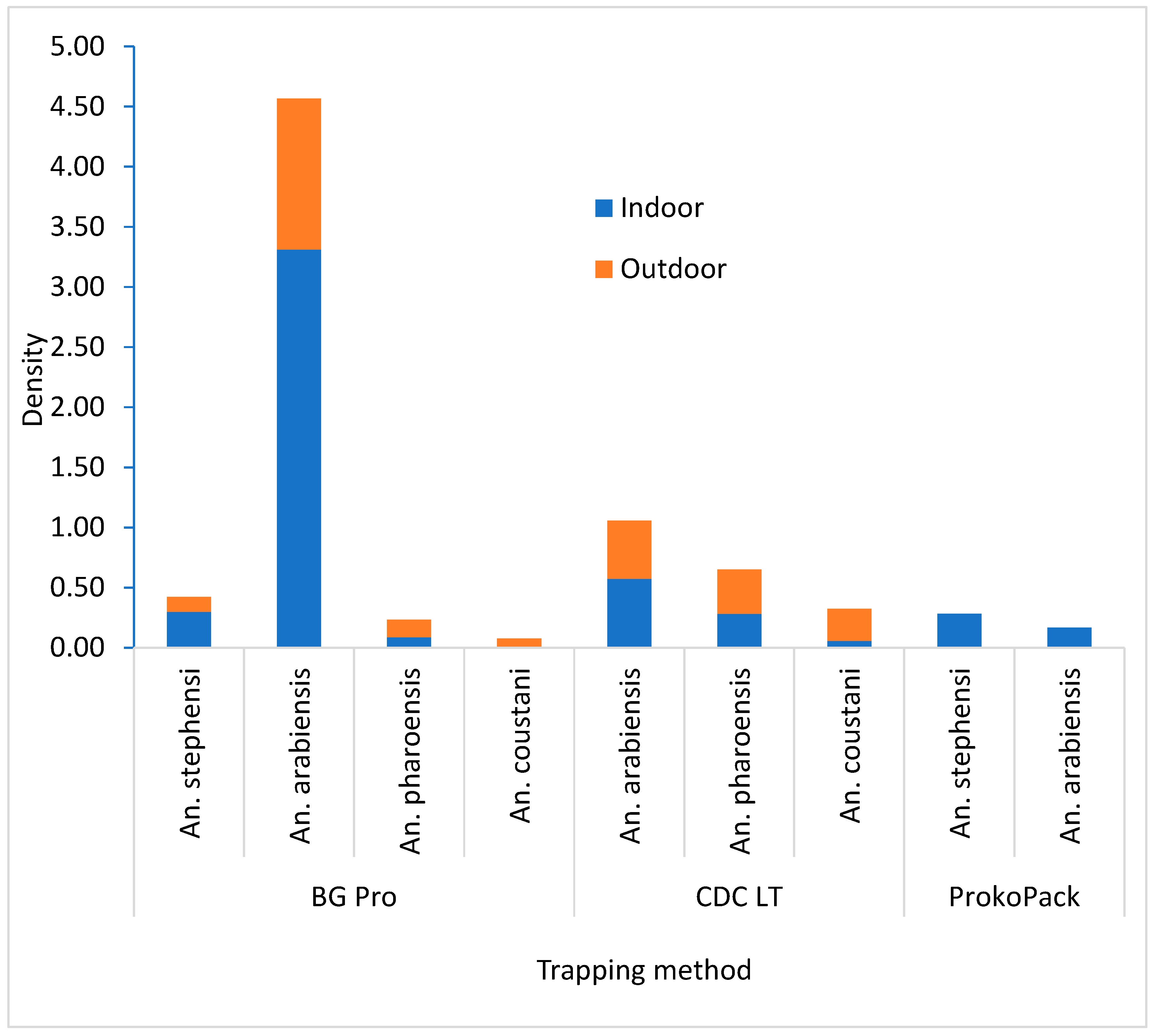

An. coustani 6.2% (n=46). A higher density of

An. arabiensis was recorded in the BG-Pro Trap collection compared to other trapping techniques (df = 2; P = 0.004), while a higher density of

An. pharoensis was observed in CDC Light Trap collection (P = 0.006).

Anopheles stephensi was exclusively captured by the BG Pro Trap and the ProkoPack Aspirator in a comparable density (P = 0.254). In both the BG Pro and CDC LT collections, more

An. arabiensis was collected indoors than outdoors. In contrast, for

An. pharoensis, outdoor density exceeded indoor density by 1.5 times in the BG Pro collection and by 1.3 times in the CDC collection (

Figure 2).

3.2. Blood Meal Source

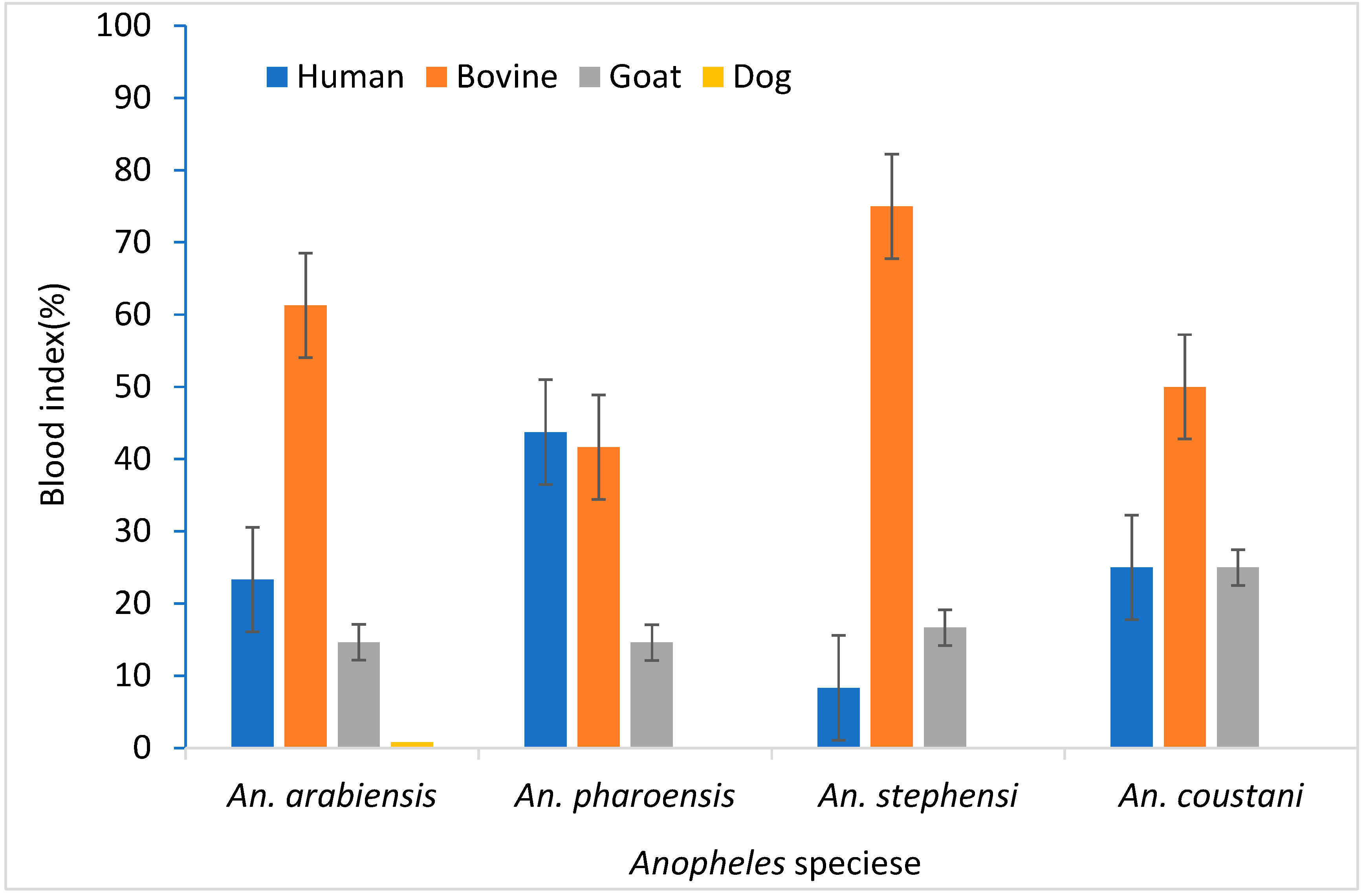

A total of 456

Anopheles mosquitoes were tested for blood meal sources. Blood meals sources identified included human, cow, goat, and dog (

Table 2). Some (37.5%) of the samples were unidentified.

Anopheles arabiensis and

An. stephensi had a lower Human Blood Index (HBI) value, 23.3 % and 8.3%, respectively. These species however demonstrated a higher Bovine Blood Index (BBI), 61.3% and 75.0%, respectively.

An. pharoensis showed similar HBI (43.8%) and BBI (41.7%) (

Figure 3).

3.3. Sporozoite Infection and Entomological Inoculation Rates

PCR results showed 4.0% of

Plasmodium falciparum and 4.0% of

Plasmodium vivax sporozoite infection in

An. arabiensis. Likewise, 3.5% of

P. vivax and 1.2% of

P. falciparum was detected in

An. pharoensis, while no infection was observed in both

An. stephensi and

An. coustani (

Table 3).

The EIR estimated for the study period showed that the study area received 4.50 and 0.25 P. falciparum-infective bites and 4.50 and 0.72 P. vivax-infective bites each night by An. arabiensis and An. pharoensis, respectively.

4. Discussion

The present study highlighted an elevated

plasmodium sporozoite infection rate in primary and secondary malaria vectors of Ethiopia as compared to previous reports.

Plasmodium sporozoite infection rate of

An.

arabiensis reported was about seven times higher than in previous studies in central and southern Ethiopia [

8,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Similarly, the observed sporozoite rate in

An. pharoensis was about six-times higher than previously reported [

32,

33,

36]. A recent study also documented the increase of malaria incidence in the study area [

19], which might be attributed to the high sporozoite infection rate observed in this study in both primary and secondary vectors. This is mainly because the area is prone to malaria epidemics due to the presence of mosquito-breeding lake shorelines of Lake Hawassa coupled with swampy areas surrounding the city. The present findings suggest the need of inclusive interventions considering both primary and secondary vectors for successful control of malaria in the area. Current control measures predominantly target the primary vectors. However, it is noted that the secondary vectors such as

An. pharoensis and An. coustani, could contribute to residual transmission [

6]. This suggests that in regions with multiple efficient malaria vectors, the interventions targeted a primary vector alone may not effectively reduce malaria transmission as other vectors could keep augmenting the transmission. Additionally, potential vector shift may also occur if targeted intervention suppresses the primary vector population as noted by Msugupakulya et al. (2023) in East and Southern Africa [

37].

Malaria transmission in Ethiopia is a complex and dynamic issue, with a substantial gap in understanding the bionomics and role of secondary vectors in disease transmission.

Anopheles pharoensis was incriminated as the second most abundant malaria vector long time ago and exhibited the second-highest

Plasmodium infection rate after

An. arabiensis in this study, suggesting its significant role in local malaria transmission. Several studies also noted that

An. pharoensis has consistently ranked second in abundance and sporozoite infection rate elsewhere in Ethiopia [

32,

33,

35]. In another laboratory study,

An. pharoensis demonstrated similar susceptibility with

An. arabiensis to

plasmodium falciparum infection [

38]. Unfortunately, less attention has been given to the secondary vectors both in research and vector control interventions in Ethiopia. The study emphasizes the need for a comprehensive understanding of secondary vectors biology, ecology, behavior, vector competence, and response to the existing interventions. As the country embraces to malaria elimination, accurate information on the role of multiple vector species on malaria transmission is critical.

The presence of

An. stephensi could further posed a significant threat to malaria control efforts in Ethiopia [

3]. As the species alarmingly spread to several areas in Ethiopia [

4,

19,

39], control measures are still not well incorporated in routine vector control strategies. Few studies from eastern Ethiopia have linked the recent regional malaria outbreak to

An. stephensi [

40,

41]. In this study, this species was occurred in sympatry with native vectors with low density in adult collections in southern Ethiopia. A recent study in the same study area reported high larval density of

An. stephensi [

19]. This indicates the species is well established in southern Ethiopia. Although no

An. stephensi specimens tested positive for

Plasmodium sporozoites in this study, probably due to small sample size due to absence of optimal vector surveillance tools for

An. stephensi adult collection, this species can be of potential risk for malaria transmission [

4,

39]. Therefore, it is advisable to intensify to further develop efficient surveillance tools to collect a good sample size of adult

An. stephensi specimens for testing, hence better defining its actual role in malaria transmission in the region. The lower HBI and

Plasmodium infection rates observed in wild

An. stephensi populations, both in this study and earlier ones from Ethiopia [

4,

39], are may be hypothesized to result from the mysorensis form of this species which has zoophilic behavior, spreading in Ethiopia (unpublished data). Future research should test these hypotheses in the invaded regions of Ethiopia.

In summary, the study documented the presence of multiple efficient malaria vectors, with An. arabiensis and An. pharoensis showing high Plasmodium infection rates, highlighting the importance of secondary vectors in malaria transmission and the need to address them in control efforts. The coexistence of An. stephensi alongside these primary and secondary vectors adds complexity to malaria control strategies in the area, necessitating continuous monitoring to understand the bionomics and evolving roles of mosquito vector species and species shift in malaria transmission.

Author Contributions

DH and GY contributed to the conception and design of the study. DH, TA, AA, AE, TM, and CA organized and led the collection of specimens. DH analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. MCL and GZ were involved in data analysis. DZ, CW, JC, AL, NS, and KKK involved in laboratory analysis.GY, DY, and SK critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants U19 AI129326 and D43 TW001505). The funders did not participate in the study design, data collection and analysis, publication decisions, or manuscript preparation.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate Hawassa University, Sidama Regional State Health Office, Hawassa City Administration Health Department, and Sidama Region Public Health Institute for facilitating the study. The Hawassa University’s Malaria Research Laboratory has coordinated the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Sinka, ME. Global distribution of the dominant vector species of malaria, Anophelesmosquitoes. New insights into Malar vectors. 2013.

- Adugna F, Wale M, Nibret E. Review of Anopheles Mosquito Species, Abundance, and Distribution in Ethiopia. J Trop Med.

- Tadesse FG, Ashine T, Teka H, Esayas E, Messenger LA, Chali W, et al. Anopheles stephensi Mosquitoes as Vectors of Plasmodium vivax and falciparum, Horn of Africa, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021, 27, 603–607.

- Balkew M, Mumba P, Yohannes G, Abiy E, Getachew D, Yared S, et al. An update on the distribution, bionomics, and insecticide susceptibility of Anopheles stephensi in Ethiopia, 2018–2020. Malar J. 2021, 20, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter TE, Yared S, Gebresilassie A, Bonnell V, Damodaran L, Lopez K, et al. First detection of Anopheles stephensi Liston, 1901 (Diptera: culicidae) in Ethiopia using molecular and morphological approaches. Acta Trop. 2018, 188, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrane YA, Bonizzoni M, Yan G. Secondary Malaria Vectors of Sub-Saharan Africa : Threat to Malaria Elimination on the Continent ? World ’ s largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access book publisher. Curr Top Malar.

- Gueye A, Hadji E, Ngom M, Diagne A, Ndoye BB, Dione ML, et al. Host feeding preferences of malaria vectors in an area of low malaria transmission. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 16410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animut A, Balkew M, Gebre-michael T, Lindtjørn B. Blood meal sources and entomological inoculation rates of anophelines along a highland altitudinal transect in south-central Ethiopia. Malar J. 2013, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katusi GC, Hermy MRG, Makayula SM, Ignell R, Govella NJ, Hill SR, et al. Seasonal variation in abundance and blood meal sources of primary and secondary malaria vectors within Kilombero Valley, Southern Tanzania. Parasit Vector. 2022, 15, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlacha YP, Chaki PP, Muhili A, Massue DJ, Tanner M, Majambere S, et al. Reduced human - biting preferences of the African malaria vectors Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles gambiae in an urban context : controlled, competitive host - preference experiments in Tanzania. Malar J. 2020, 19, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yewhalaw D, Kelel M, Getu E, Temam S, Wessel G. Blood meal sources and sporozoite rates of Anophelines in Gilgel-Gibe dam area, Southwestern. African Journ Vect Bio.

- Asale A, Duchateau L, Devleesschauwer B, Huisman G, Yewhalaw D. Zooprophylaxis as a control strategy for malaria caused by the vector Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae): A systematic review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017, 7, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Fornadel CM, Norris LC, Glass GE, Norris DE. Analysis of Anopheles arabiensis blood feeding behavior in southern zambia during the two years after introduction of insecticide-treated bed nets. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 83, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahande A, Mosha F, Mahande J, Kweka E. Feeding and resting behaviour of malaria vector, Anopheles arabiensis with reference to zooprophylaxis. Malar J. 2007, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett-Jones C, Boreham PFL, Pant CP. Feeding habits of anophelines (Diptera: Culicidae) in 1971–1978, with reference to the human blood index: A review. Bull Entomol Res. 1980, 70, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S, Rubio-Palis Y, Chareonviriyaphap T, Coetzee M, et al. A global map of dominant malaria vectors. Parasit Vector. 2012, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas S, Ravishankaran S, Justin NAJA, Asokan A, Mathai MT, Valecha N, et al. Resting and feeding preferences of Anopheles stephensi in an urban setting, perennial for malaria. Malar J. 2017, 16, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha AM, Musembi S, Nyamache AK. Secondary malaria vectors in western Kenya include novel species with unexpectedly high densities and parasite infection rates. Parasite Vector. 2021, 14, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawaria D, Kibret S, Zhong D, Lee MC, Lelisa K, Bekele B, et al. First report of Anopheles stephensi from southern Ethiopia. Malar J. 2023, 22, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawassa City Administration Health Department. Annual Malaria Morbidity report. Hawassa; 2022.

- Coetzee, M. Key to the females of Afrotropical Anopheles mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar J. 2020, 19, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong D, Hemming-Schroeder E, Wang X et al. Extensive new Anopheles cryptic species involved in human malaria transmission in western Kenya. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 16139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993, 49, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbewe RB, Keven JB, Mzilahowa T, Mathanga D, Wilson M, Cohee L, et al. Blood-feeding patterns of Anopheles vectors of human malaria in Malawi: implications for malaria transmission and effectiveness of LLIN interventions. Malar J. 2022, 21, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keven JB, Artzberger G, Gillies ML, Mbewe RB, Walker ED. Probe-based multiplex qPCR identifies blood-meal hosts in Anopheles mosquitoes from Papua New Guinea. Parasite Vector. 2020, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokoples SE, Ndao M, Kowalewska-Grochowska K, Yanow SK. Multiplexed real-time PCR assay for discrimination of Plasmodium species with improved sensitivity for mixed infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009, 47, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann N, Mwingira F, Shekalaghe S, Robinson LJ, Mueller I, Felger I. Ultra-Sensitive Detection of Plasmodium falciparum by Amplification of Multi-Copy Subtelomeric Targets. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001788. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent Veron, Stephane Simon BC. Multiplex real-time PCR detection of P. falciparum, P. vivax and P. malariae in human blood samples. Exp Parasitol. 2009, 121, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakeley C, Schellenberg D, Kihonda J, Sousa CA, Arez AP, Lopes D, et al. An estimation of the entomological inoculation rate for Ifakara: A semi-urban area in a region of intense malaria transmission in Tanzania. Trop Med Int Heal. 2003, 8, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogola E, Villinger J, Mabuka D, Omondi D, Orindi B, Mutunga J, et al. Composition of Anopheles mosquitoes, their blood - meal hosts, and Plasmodium falciparum infection rates in three islands with disparate bed net coverage in Lake Victoria, Kenya. Malar J. 2017, 16, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adugna T, Yewhelew D, Getu E. Bloodmeal sources and feeding behavior of anopheline mosquitoes in Bure district, northwestern Ethiopia. Parasite Vector. 2021, 14, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschale Y, Getachew A, Yewhalaw D, Cristofaro A De, Sciarretta A. Systematic review of sporozoite infection rate of Anopheles mosquitoes in Ethiopia, 2001 – 2021. Parasit Vector. 2023, 16, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibret S, Lautze J, Boelee E, Mccartney M. How does an Ethiopian dam increase malaria ? Entomological determinants around the Koka reservoir. Trop Med Int Heal Vol. 2012, 17, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yewhalaw D, Legesse W, Bortel W Van, Gebre- S, Kloos H, Duchateau L, et al. Malaria and water resource development : the case of Gilgel-Gibe hydroelectric dam in Ethiopia. Malar J. 2009, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam A, Asale A, Waldetensai A, Eukubay A, Tasew G, Massebo F, et al. Malaria vector feeding, peak biting time and resting place preference behaviors in line with Indoor based intervention tools and its implication : scenario from selected sentinel sites of Ethiopia. Hellyon.

- Kibret S, Alemu Y, Boelee E, Tekie H, Alemu D, Petros B. The impact of a small-scale irrigation scheme on malaria transmission in Ziway area, Central Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2010, 15, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Msugupakulya BJ, Urio NH, Jumanne M, Ngowo HS, Selvaraj P. Changes in contributions of different Anopheles vector species to malaria transmission in east and southern Africa from 2000 to 2022. Parasit Vector. 2023, 16, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abduselam N, Zeynudin A, Berens-riha N, Seyoum D, Pritsch M, Tibebu H, et al. Similar trends of susceptibility in Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles pharoensis to Plasmodium vivax infection in Ethiopia. Parasit Vectors [Internet]. Parasite Vector 2016, 9, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashine T, Eyasu A, Asmamaw Y, Simma E, Zemene E, Epstein A, et al. Spatiotemporal distribution and bionomics of Anopheles stephensi in different eco - epidemiological settings in Ethiopia. Parasit Vector. 2024, 17, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiru T, Getachew D, Murphy M, Sedda L, Ejigu LA, Bulto MG, et al. Evidence for a role of Anopheles stephensi in the spread of drug- and diagnosis-resistant malaria in Africa. Nat Med.

- de Santi VP, Khaireh BA, Chiniard T, Pradines B, Taudon C, Larréché S, et al. Role of Anopheles stephensi Mosquitoes in Malaria Outbreak, Djibouti, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021, 27, 1697–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).