1. Introduction

Aedes aegypti is of great public health concern because of its vectorial capacity to transmit various arboviruses such as Zika, yellow fever, dengue, and chikungunya [

1]. In California, its expanding geographic distribution has worried the public [

2]. Between 2016 and 2023, over 1200 travel-associated dengue cases were documented in California [

3], indicating the risk of local transmission due to the presence of competent vector. In 2023, two locally acquired dengue cases were reported for the first time in southern California [

4]. Additionally, a total of 15 locally acquired dengue infections were documented in 2024, indicating the increasing risk of local transmission occurring regularly [

4]. This indeed urgently calls for innovative tools to strengthen the existing Integrated Vector Management (IVM).

The existing IVM utilizes various strategies such as source reduction, biological control (e.g., larvivorous fish), chemical treatment and community engagement to mitigate the expanding distribution of invasive mosquitoes. In2Care® Mosquito Stations, which combines pyriproxyfen autodissemination with the entomopathogenic fungus

Beauveria bassiana to reduce the emergence of

Aedes mosquitoes and subsequently kill the contaminated adult females [

5], have been added recently to complement IVM strategies especially in urban areas with multiple small, cryptic breeding sites [

6]. However, while existing IVM tools continue to moderately suppress invasive mosquito breeding, new innovative tools are required to effectively control the spread of these mosquitoes in diverse settings. Sterile insect technique (SIT) is therefore emerging as a promising and eco-friendly method for controlling

Aedes aegypti populations [

7,

8], especially when used along with the existing IVM strategies.

SIT has been successfully used for decades to control several insect pests, such as the Mediterranean fruit fly [

9], New World screwworm [

10], Mexican fruit fly [

11], tsetse fly [

12], and pink bollworm [

13]. Due to cryptic breeding habitats of

Aedes mosquitoes [

14], the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) has gained momentum as a potential biological control strategy to fight these invasive mosquitoes.

SIT involves mass-rearing male mosquitoes, sterilizing them through irradiation or genetic modification, and then releasing them into the wild. Unlike genetic modification (GM)-based SIT that involves the introduction of engineered genes into male mosquitoes to render them sterile or lethal to their offspring, irradiation-based SIT utilizes ionizing radiation, such as X-rays, to sterilize the male mosquitoes [

15]. The radiation damages the reproductive cells of the male mosquitoes, rendering them sterile without affecting their overall fitness for mating [

16] The sterile males are then released into the wild, where they compete with wild males for female mates. When wild females mate with sterile males, no viable offspring are produced, gradually reducing the mosquito population.

The success of SIT depends on several factors, including the release of a sufficient number of sterile males, ensuring that they are competitive with wild males for mating opportunities, and sustaining multiple releases over time. Logistics is another critical factor that affects the scalability of SIT-based vector control interventions, especially in area-wide applications. Targeted application, on the other hand, requires limited resources and focuses on specific hotspots where mosquitoes pose the greatest risk. This approach is especially preferable for small- to medium-sized vector control agencies since it prioritizes areas with high mosquito density or disease risk unlike area-wide treatment. Since

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes disperse short distances [

17], released sterile mosquitoes will remain in the targeted area, increasing the likelihood of sterile males mating with wild females in the targeted hotspots to result in the desired outcome.

Here we are reporting the first-year outcome of targeted sterile insect releases in southern California to mitigate invasive Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. The study aimed to evaluate the impact of sterile insect releases on overall Ae. aegypti population reduction in historical Aedes hotspots.

2. Materials and Methods

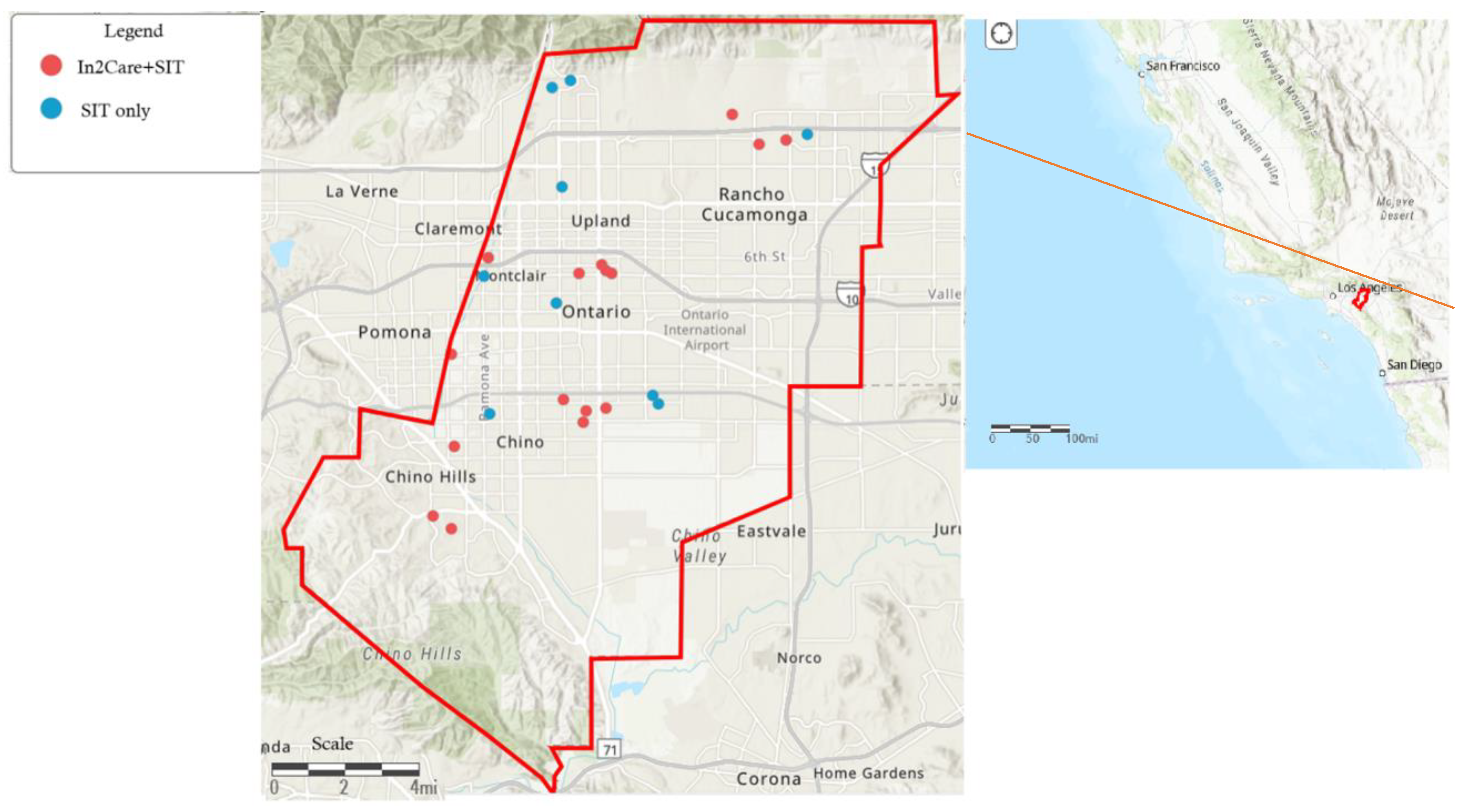

This work was conducted in the West Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District (WVMVCD) in southwestern San Bernardino County, California (

Figure 1). The District covers 544 km

2 and serves over 600,000 residents in the cities of Chino, Chino Hills, Montclair, Ontario, Rancho Cucamonga, Upland, and surrounding unincorporated county areas. The region exhibits a semi-arid climate, with hot summers and mild winters. The summers (June to September) are characterized by temperatures that can reach up to 43

oC. During the winter (December to February), the temperatures drop to as low as 5

oC, with minimal rainfall (average annual rainfall = 381 mm) (

www.usclimatedata.com). The mosquito season lies in the summer. Peak

Ae. aegypti population occurs between July and September [

18].

2.1. Preparation for Sterile Insect Release

Locally obtained

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes were reared in the WVMVCD insectary. The details of mosquito rearing procedure have been documented in our recent work [

19]. In brief, mosquito eggs were hatched in a flask with yeast infused 400 ml water and kept under 600 mmHg negative pressure for one hour. Once hatched, the flask was emptied into a large tub (35.9x19.4x12.4 cm) with 2 L of tap water and 0.44 g alfalfa rabbit food pellets. A further 0.44 g alfalfa pellets were provided to third and fourth instar larvae. Pupae were collected into 540 mL cylindrical plastic containers filled with water and placed in a cage (30x30x30 cm) for emergence. Adults emerging were sorted out by sex using morphological features. Battery operated handheld aspirators (Clarke®, St. Charles, IL) were used by trained technicians to sort out male mosquitoes from the cages within 24 hrs after emergence. Freshly emerged (<1 d old) male

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes were placed in small cup (266 ml) (200 mosquitoes per cup) to be treated at 55 Gray (Gy) radiation dose using Rad Source X-ray Machine (Rad Source RS 1800·Q, Rad Source Technologies, Buford, GA), at a dose rate of 13.89 Gy/min for 7.8 min per round. This dosage was determined effective in sterilizing mosquitoes (>95% sterility) with minimal fitness cost for our mosquito colony [

20]. After irradiation, male mosquitoes were allowed to rest for 30 min before being released back to their cages. Approximately 1,000 – 1,600 sterile males were kept per cage and provided 10% sucrose solution ad libitum until field released. Room temperature was maintained at 27

o ± 2

oC and relative humidity of 55-65%, with a 12:12 hr light:dark photo period. Sterile males were released into the field within 24–48 hours after irradiation.

2.2. Selecting Sites for SIT Release

Historically high-count Ae. aegypti sites were selected for SIT applications. WVMVCD conducts weekly mosquito surveillance from February to November throughout its District. The Biogents (BG-2) Sentinel traps (Clarke, St. Charles, IL) complemented with synthetic lures that mimic human scents (Clarke, St. Charles, IL) and a bucket filled with dry ice (1 kg) were utilized to monitor invasive Aedes mosquito abundance. Mosquitoes collected by these traps were sorted out to species and recorded.

Our routine IVM strategy for

Aedes management includes source reduction, biological control using mosquitofish and community outreach. When BG-2 traps indicate over 20

Ae. aegypti/trap-night, sites receive an In2Care® Mosquito Station which will be kept at the site throughout the season. Here, a treatment site is defined as a residential property with average property size of about 200 sq m (

www.census.gov). Mosquito Stations were serviced every four weeks. Details of the deployment and maintenance of In2Care® Mosquito Station are previously reported [

5].

A total of 25 Ae. aegypti hotspot sites (with >50 Ae. aegypti per trap-night during the peak mosquito season in 2023) were selected for SIT application. These sites were grouped into two cohorts – sites that received SIT treatment only (n=9) and sites that received both SIT treatment and In2Care® Mosquito Station (n=16). In the latter group, sites received In2Care® Mosquito Station when the mosquito counts hit our set threshold (20 Ae. aegypti/trap-night), in accordance with our routine vector management protocol. Sites that received SIT treatment only did not have an In2Care® Mosquito Station in the property or within 0.5 km radius throughout the year to avoid its effect.

2.3. SIT Applications

Irradiated male Ae. aegypti were released within 48 hrs after irradiation treatment. Releases were made bi-weekly between April to November 2024, throughout the mosquito season. Between 1,000 and 1,600 sterile mosquitoes were kept in BugDorm cages (30 x 30 x 30 cm) (Insectabio Inc, Riverside, CA) and releases were made by opening the roof of the cage in the mid-morning hours once the weather was warm enough for mosquitoes to fly out. This was done by trained technicians. First, technicians would canvass the area to make sure the environment was optimal (e.g. not windy) for release. At each release, the number of dead mosquitoes in the cage was recorded. The number of mosquitoes released at each site was determined by the number of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes collected by the BG-2 traps the prior week. At least, a 100-times the number of female Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, (determined by BG-2 traps) were released at each site during treatment weeks. Overall, between 1,000 and 3,000 sterile male Ae. aegypti were released at each site throughout the treatment weeks.

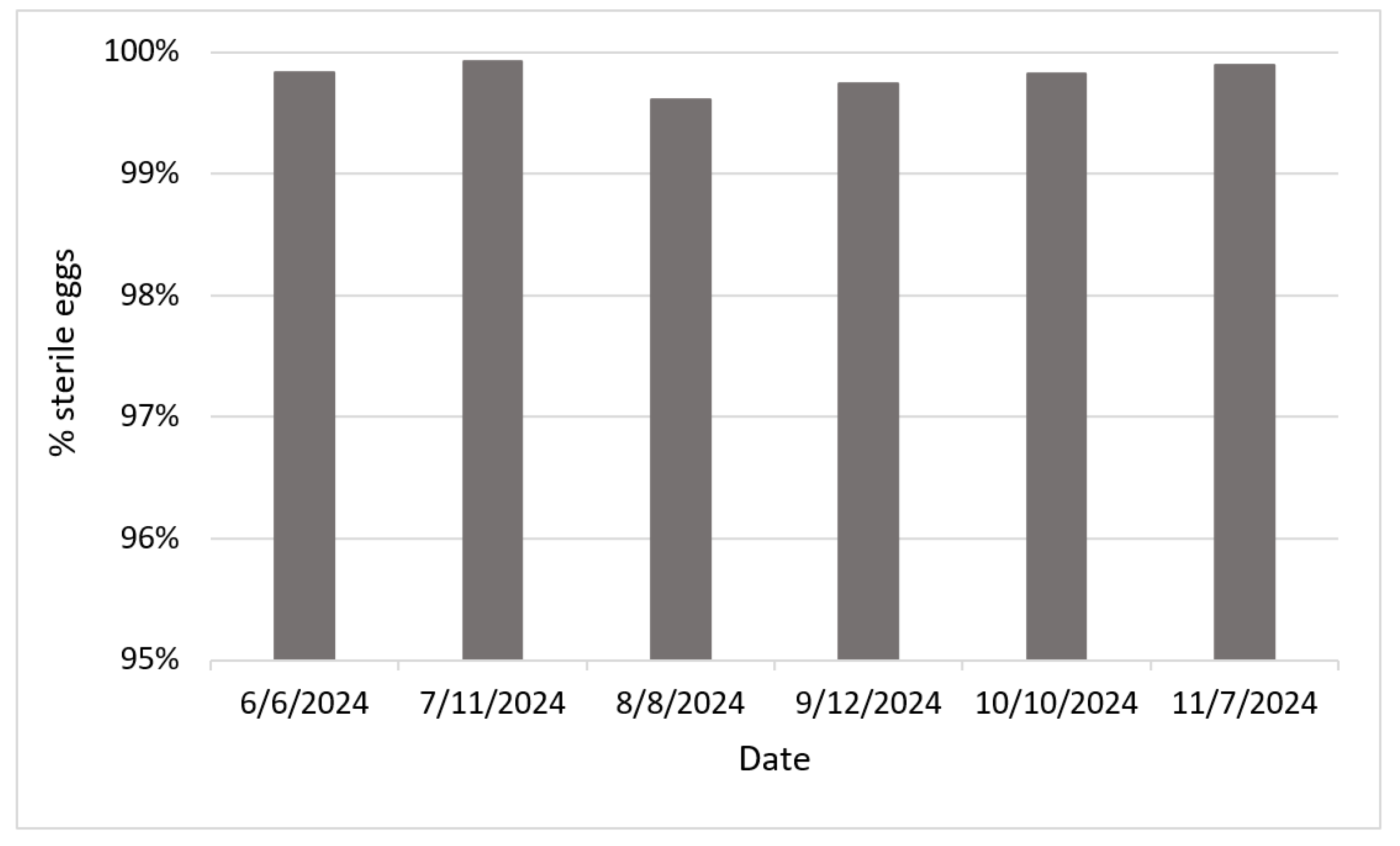

2.4. Quality Control

During the mosquito season, we extracted a subset of samples (n=50) of irradiated male mosquitoes from release cages and placed them in a separate cage with freshly emerged unirradiated female mosquitoes in a 1:1 ratio to evaluate the level of sterility of the eggs from these mosquitoes. This was done to monitor the sterility of irradiated male mosquitoes released. Sugar water (10%) was provided ad libitum. After one week, female mosquitoes were blood fed with bovine blood using glass feeders [

19]. Mosquitoes were blood fed for two days. Five days after blood feeding, egg collection cups lined with filter paper and half filled with water and yeast infusion were placed in cages and left for 5 days. Then filter papers holding eggs were removed and left to dry at normal room temperature. Once dried and counted, eggs were hatched using the procedure described above. Hatched larvae were counted, removed, and destroyed.

2.5. Follow Up – BG-2 Mosquito Trapping

Weekly mosquito surveillance was done at all SIT sites using BG-2 traps between April to November 2024. During the week of sterile insect release, trapping was done before the release day to avoid the chances of catching released mosquitoes. Traps were set on the front yard of houses under a tree or shrub in the afternoon and collected the following morning. Verbal consent was received from homeowners before trapping at each residential site. Trapped mosquitoes were sorted to species and recorded by trained technicians in WVMVCD lab.

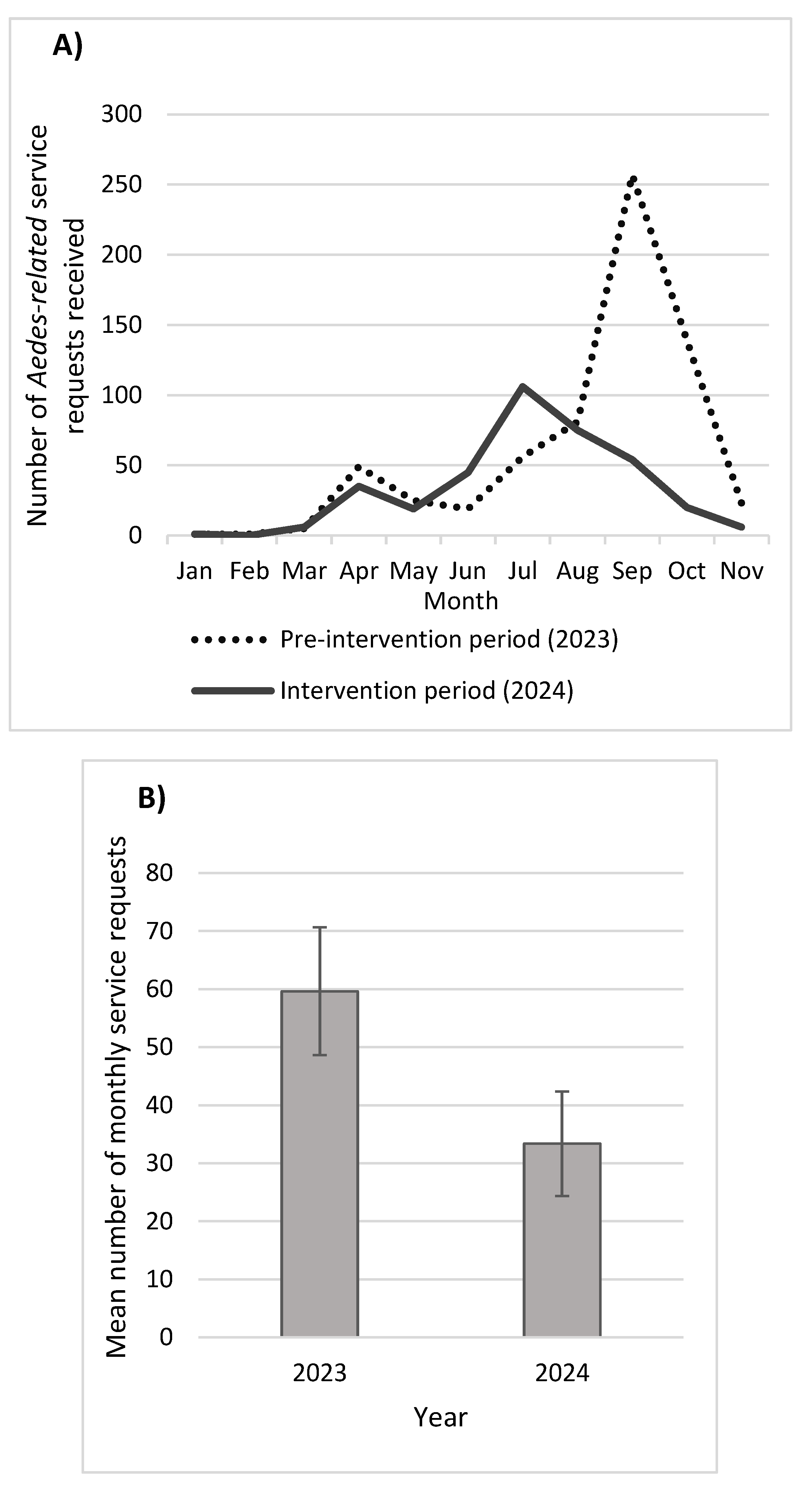

2.6. Aedes-Related Service Requests

As an indirect way of measuring the impact of our vector control, we utilized the data of service requests the WVMVCD received from residents within the District. A service request is defined as when residents call or email the District seeking mosquito management services when bothered by mosquitoes. As a government agency, we provide vector control service by sending out our trained and licensed technicians to inspect the residential property and follow IVM strategies as necessary to control mosquito breeding. Here, we collected the service request data for 2023 and 2024 to represent pre-intervention and intervention periods, respectively. Service requests are considered Aedes- related if the resident complains about being bitten by mosquitoes during the day. If our optimized IVM strategies that incorporated SIT are working, we assumed that we would receive less service request calls.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All recorded data were entered into Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS version-20 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The mean number of female Ae. aegypti per trap-night was calculated for each cohort to compare mosquito density pre-intervention and during intervention. Male counts were not included because there was no way to differentiate the released sterile insects from wild. Therefore, efficacy of the sterile insect release application was measured by the amount of females Ae. aegypti in the BG-2 traps. Data from 2023 was considered as “pre-intervention” since no sterile insect releases were made in 2023. Since sterile releases were made throughout 2024 mosquito season at these sites, the data from 2024 was considered as “intervention” dataset. The monthly mean number of service requests was compared between pre-intervention (2023) and intervention (2024) periods. This data was utilized as an indirect way to measure Aedes-related mosquito problems between the two study periods.

After testing the normality of the data using Shapiro-Wilk test, repeated measures ANOVA was applied to determine differences in mosquito density between pre-intervention and intervention periods. All statistical analyses were performed at the 5 % significance level.

3. Results

3.1. Sterile Ae. aegypti Releases

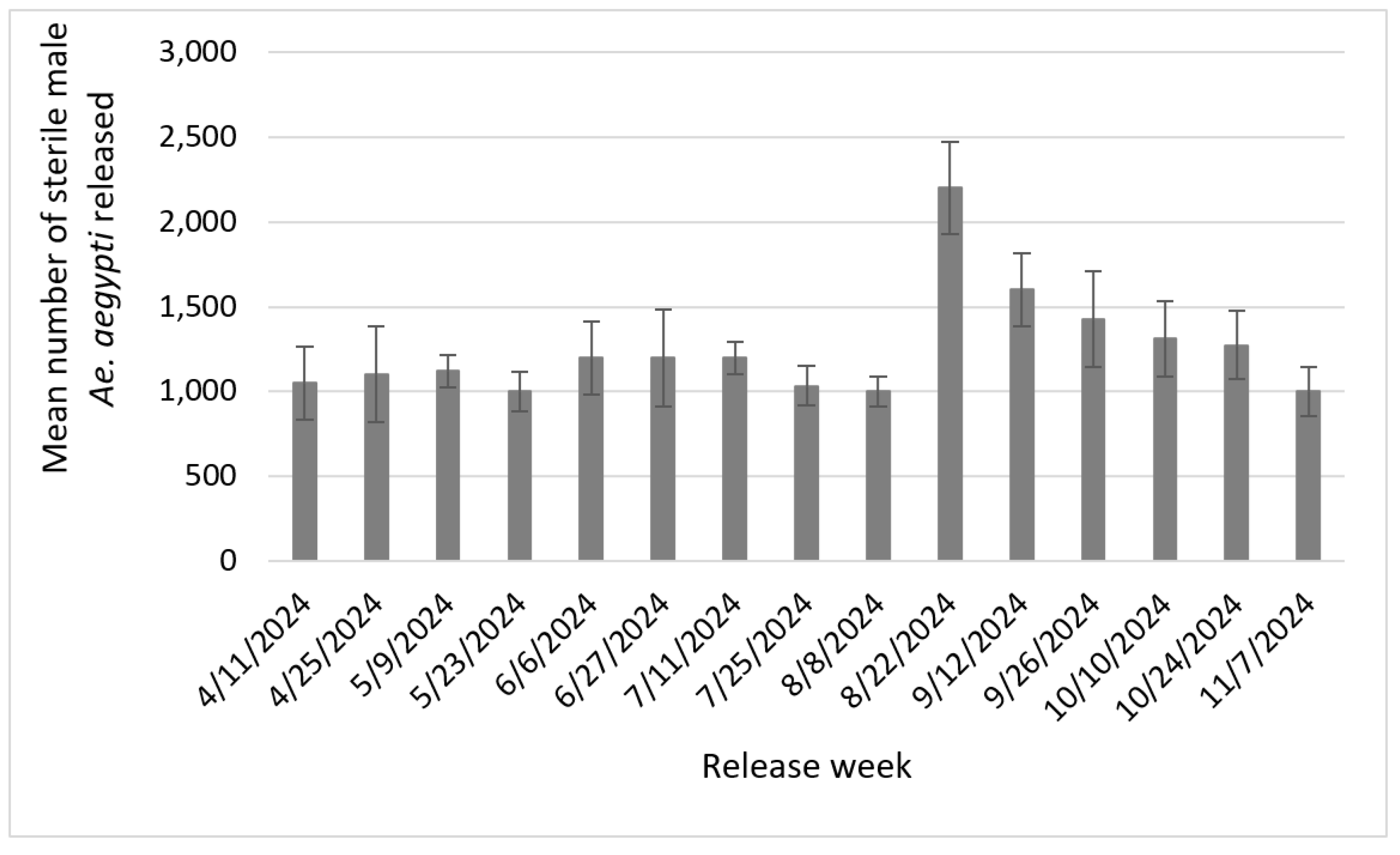

A total of 106,608 sterile

Ae. aegypti were released between April and November 2024 at 25 sites in the WVMVCD (

Figure 2). At each site, on average 1,215 sterile mosquitoes (ranging from 1,050 to 2,200) were released bi-weekly. More sterile mosquitoes were released during the peak of the mosquito season.

3.2. Effect of SIT on Mosquito Abundance

The mean number of female

Ae. aegypti per trap-night were compared between pre-intervention and intervention periods for both cohorts (

Table 1). In the SIT treatment only cohort, the mean number of female

Ae. aegypti per trap-night during intervention period (mean = 10.8 female

Ae. aegypti per trap-night; 95%CI = 8.5 – 13.1; ANOVA,

P < 0.005) was 44% lower than the pre-intervention period (mean = 19.2; 95%CI =14.3 – 24.1). The cohort that received both In2Care® Mosquito Stations and SIT treatment showed a 65% reduction in the number of female

Ae. aegypti per trap-night in the intervention period (mean = 8.2; 95%CI = 3.6 – 12.8; ANOVA,

P < 0.005) compared to the pre-intervention period (mean = 23.5; 95%CI = 19.1 – 27.9).

3.3. Weekly Mosquito Abundance Trend

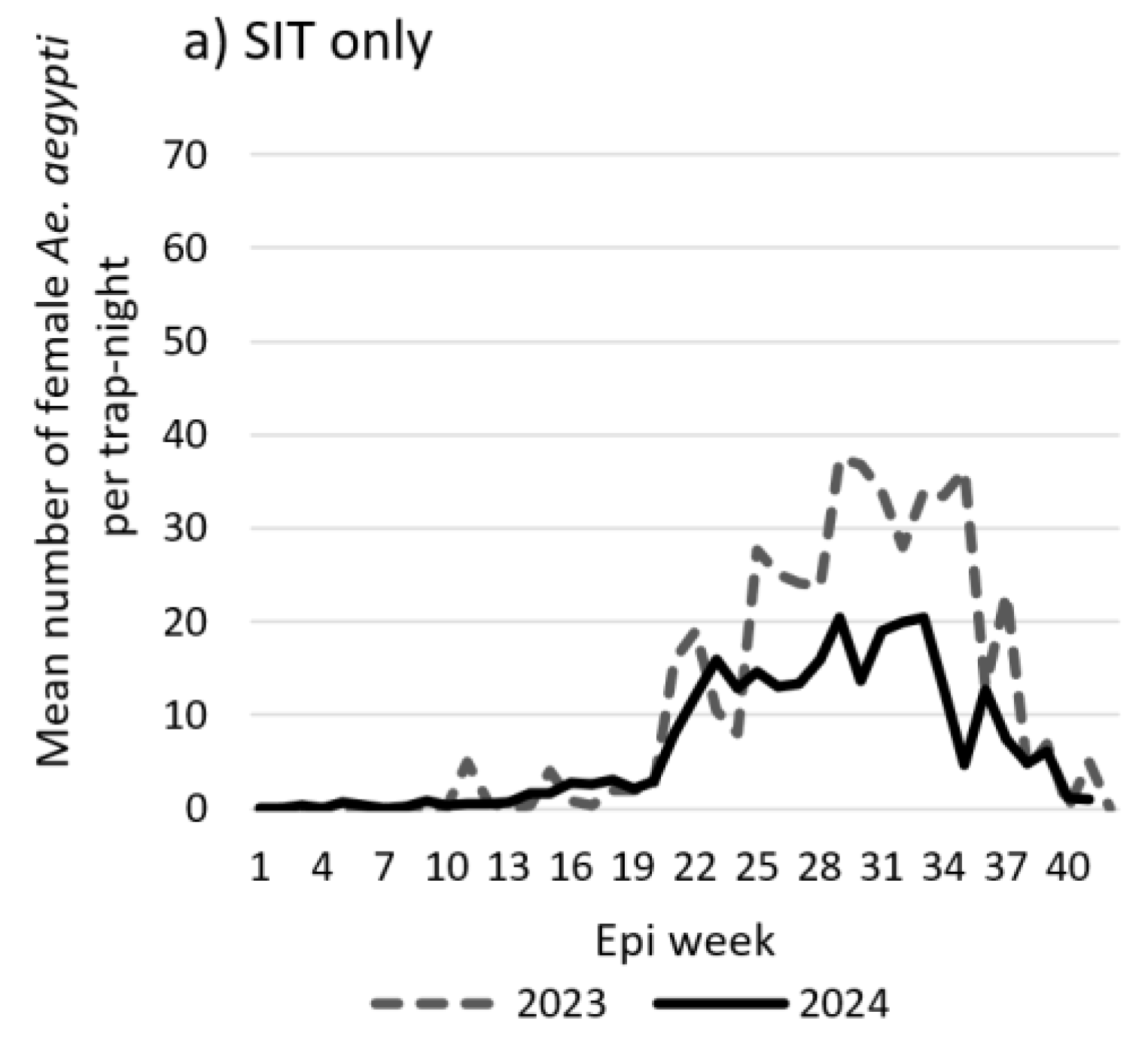

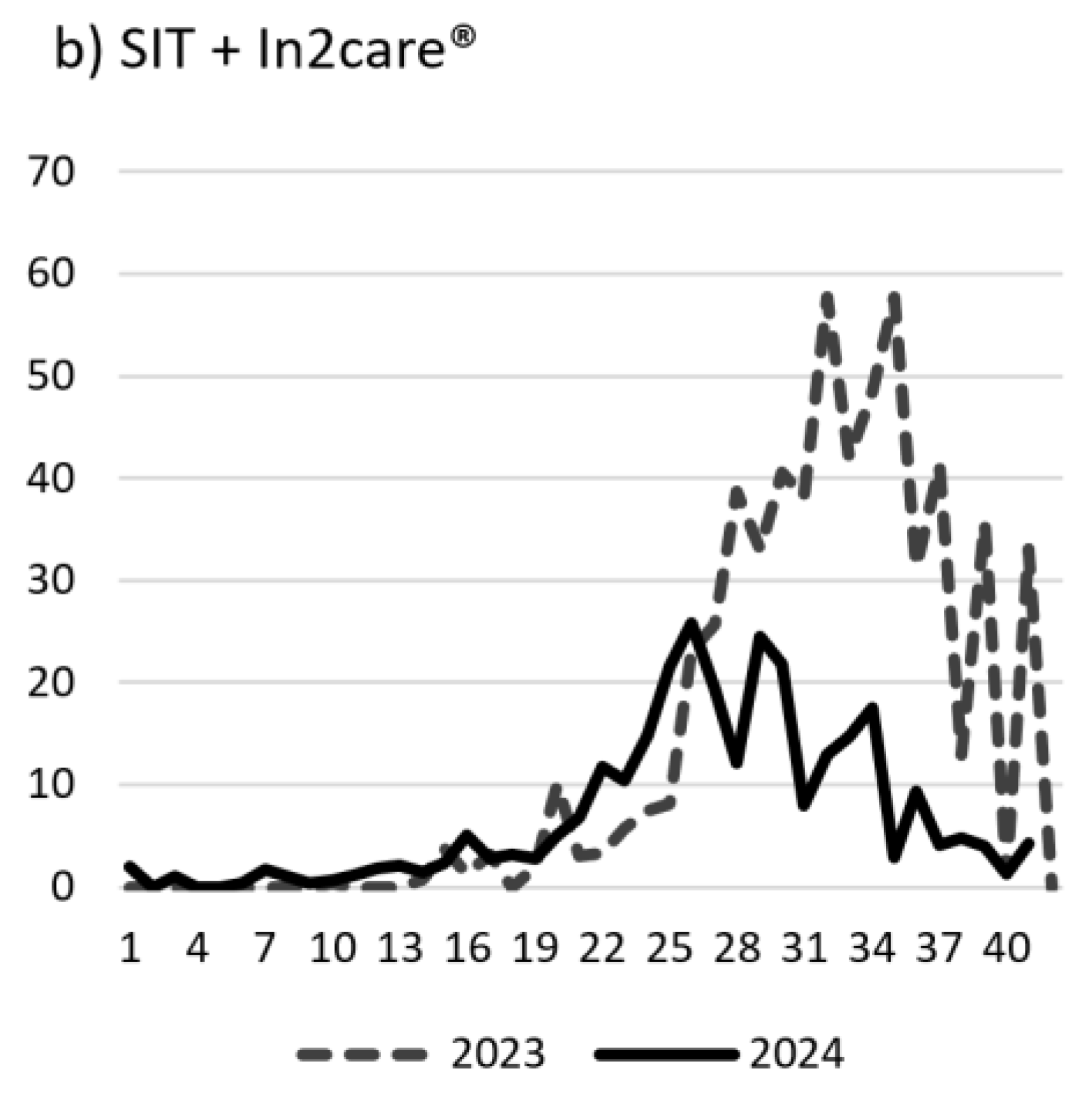

The mean weekly number of female

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes during the pre-intervention and intervention periods in two cohorts are shown on

Figure 3. The weekly female

Ae. aegypti mosquito counts in both cohorts (SIT only and SIT sites with In2Care® Mosquito Stations) were consistently lower in the intervention period compared to the pre-intervention period throughout most of the year. Highest reductions in mosquito counts during the intervention period were observed during peak mosquito season (July and August).

3.4. Quality Control Data

A subset of sterile male

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes from six releases were checked for sterility by letting them to mate with unirradiated female mosquitoes in the laboratory. Over 99.6% eggs collected from these female mosquitoes did not hatch, indicating a high level of sterility of the irradiated males utilized for our SIT application (

Figure 4).

3.5. Aedes-Related Service Requests

The total number of

Aedes-related service requests received from the District’s residents during the intervention year (2024) (n = 367) was 45% lower than the number of service requests received during the pre-intervention year (2023) (n = 656) (

Figure 5). Especially during the peak mosquito season, the number of service requests dropped between 79% – 86% in September and October. While a slight increase in service requests was observed in July during the intervention year, numbers remarkably declined thereafter throughout the mosquito season. Overall, the mean number of monthly

Aedes-related service requests dropped significantly in the intervention period (mean = 33.4 service requests per month; 95% CI = 26.2 – 40.4; ANOVA,

P< 0.05) compared to the pre-intervention period (mean =59.6; 95% CI = 48.1 – 71.2).

4. Discussion

This study documented a dramatic reduction in Ae. aegypti population in areas that received targeted bi-weekly SIT treatment. While SIT application alone resulted in a 44% reduction in Ae. aegypti population at these hotspot sites, combining SIT with optimized IVM strategies (mainly In2Care® Mosquito Stations) offered a 65% reduction in Ae. aegypti populations in treatment sites with historical Aedes endemicity. In addition, the number of service requests – residents seeking vector control services because of mosquito bites – dropped by 45% during the intervention period compared to pre-intervention period. This highlighted the potential efficacy of targeted SIT approach for invasive Aedes control in California. Unlike area-wide treatment, targeted SIT release is affordable and manageable especially for small- to medium-sized vector control agencies as it requires fewer resources. This is the first time significant invasive mosquito reduction is documented by utilizing targeted SIT approach.

In Thailand, using similar targeted approach – by releasing approximately 100–200 irradiated

Wolbachia-infected

Ae. aegypti males for six months in selected hotspot houses, a significant reduction (97.30%) in the mean number of female

Ae. aegypti per household was achieved in the treatment areas when compared to the control ones [2021]. In Greece, by releasing sterile male

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes at a rate of 2,547 ± 159 per hectare (or 10,000 sq m) per week as part of an area-wide integrated vector management strategy, a gradual reduction in egg density, reaching 78% from mid-June to early September was achieved [

22]. In our study, we released an average of 1,215 sterile mosquitoes (ranging from 1,050 to 2,200) per house (average property area = 200 sq m) biweekly. Targeted SIT treatment is therefore impactful and convenient in areas with distinct invasive

Aedes hotspots.

Tailoring the SIT program to meet local circumstances is therefore vital for achieving desired outcomes. A recent study reviewed 27 mark-release-recapture experiments and reported that a median distance travelled by

Ae. aegypti is only 106 m [

17]. This makes the targeted SIT application approach preferable as released mosquitoes will remain in the treatment area. However, the effect of resurgence of mosquitoes from adjacent mosquito prevalent sites could be inevitable [

14,

23]. Therefore, continuous monitoring of

the Aedes mosquito population by strengthening and expanding mosquito surveillance throughout the service area is crucial.

Between 2019 and 2024, WVMVCD successfully doubled the annual number of mosquito traps set, increasing from 771 traps in 2016 to 1,429 traps in 2024 (Supplementary Material 1). This significant expansion in surveillance efforts allowed us to monitor mosquito populations with greater precision and frequency. By intensifying our monitoring capabilities, we were able to identify mosquito hotspots in a timely manner, providing critical insights into where intervention efforts should be prioritized. Early detection of these hotspots, well before mosquito populations peaked, enabled us to implement IVM strategies more comprehensively and effectively. This proactive approach ensured that resources were allocated efficiently, reducing the risk of outbreaks and contributing to better control of mosquito-borne diseases in the targeted regions.

Integrating In2Care® Mosquito Stations and SIT into the IVM toolbox significantly enhances the control of

Aedes mosquitoes by providing complementary, environmentally friendly tools. In2Care® Mosquito Stations target both mosquito populations and their cryptic breeding habitats with minimal human intervention. The SIT, on the other hand, introduces sterile male mosquitoes into the population, which mate with wild females but produce no offspring, leading to a gradual population decline. Combining these methods within an IVM framework optimizes mosquito control by addressing multiple stages of the mosquito life cycle, enhancing the sustainability and effectiveness of control programs, reducing reliance on chemical insecticides, and mitigating the development of resistance. While placement of In2Care® Mosquito Stations is dependent on each homeowner’s voluntary approval in cities which profoundly affects its widespread utilization, SIT brings an opportunity to deal with mosquitoes using mosquitoes themselves [

8]. Together, these tools offer a strategic advantage in combating

Aedes populations and associated diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus.

The sterility of irradiated male

Ae. aegypti reported in this study (>99.6%;

Figure 4) was comparable to previous reports [

20,

24,

25]. Such high level of sterility highlights advancements in irradiation protocols and techniques, ensuring that sterile males are more effective in suppressing wild mosquito populations when released. High sterility rates combined with the high irradiated mosquitoes survivorship (63% daily survivorship) we reported recently [

20] enhance the efficacy of the SIT applications.

In conclusion, as SIT gains traction as a key tool in IVM strategies for Ae. aegypti control, targeted application would benefit effective utilization of limited resources. Here, we have demonstrated a great potential of SIT when combined with existing IVM strategies such as In2Care® Mosquito Stations, offering a holistic approach to reducing the public health risks associated with Aedes-borne diseases. Extensive surveillance across the district allowed for the timely identification of Aedes hotspots, enabling targeted interventions at the beginning of the mosquito season before populations soar significantly. This proactive approach could help to effectively flatten the seasonal mosquito density curve, hence suppressing mosquito population and associated risks. Importantly, the number of residents seeking vector control services declined during the intervention period compared to the pre-intervention period, reflecting the program’s success. Ensuring a high sterility rate of irradiated male mosquitoes through rigorous quality control measures proved essential in maintaining the efficacy of SIT. Looking ahead, expanding efforts to identify and target Aedes hotspots intensively before the onset of the mosquito season will further suppress Aedes populations and minimize the risk of Aedes-borne diseases, enhancing public health outcomes across the district.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.B and M.Q.B.; methodology, S.K.B. and M.Q.B.; validation, , S.K.B., J.H. and M.Q.B.; formal analysis, , S.K.B., J.H. and M.Q.B.; investigation, S.K.B., J.H., J.T.C and M.Q.B.; resources, S.K.B., J.H., J.T.C and M.Q.; data curation, S.K.B., J.H., J.T.C., A.M., R.C., H.H., D.M. and K.PL.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.B., J.H. and M.Q.B; writing—review and editing, S.K.B., J.H., J.T.C., A.M., R.C., H.H., D.M., K.PL, M.Q.B.; visualization, S.K.B., J.H.; supervision, S.K.B. and M.Q.B.; project administration, S.K.B and M.Q.B; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the West Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District, California.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McGregor, B.L.; Connelly, C.R. A review of the control of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in the continental United States. J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58, 10-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- California Department of Public Health (CDPH). 2023a. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus Mosquitoes in California by County/City. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document%20Library/AedesDistributionMap.pdf.

- California Department of Public Health (CDPH). 2023b. Guidance for Surveillance of and Response to invasive Aedes mosquitoes and Dengue, Chikungunya, And Zika in California. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document%20Library/InvasiveAedesSurveillanceandResponseinCA.pdf.

- California Department of Public Health (CDPH). 2024. CDPH Monthly Update on Number of Dengue Infections in California December 1, 2024. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document%20Library/TravelAssociatedCasesofDengueVirusinCA.pdf.

- Su, T.; Mullens, P.; Thieme, J.; Melgoza, A.; Real, R.; Brown, M.Q. Deployment and fact Analysis of the In2Care® mosquito trap, a novel tool for controlling invasive Aedes species. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2020, 36(3), 167-74. [CrossRef]

- Buckner, E.A.; Williams, K.F.; Ramirez, S.; Darrisaw, C.; Carrillo, J.M.; Latham, M.D.; Lesser, C.R. A field efficacy evaluation of In2Care® mosquito traps in comparison with routine integrated vector management at reducing Aedes aegypti. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2021, 37(4), 242-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gato, R.; Menéndez, Z.; Prieto, E.; Argilés, R.; Rodríguez, M.; Baldoquín, W.; Hernández, Y.; Pérez, D.; Anaya, J.; Fuentes, I.; Lorenzo, C. Sterile insect technique: successful suppression of an Aedes aegypti field population in Cuba. Insects. 2021, 12(5), 469. [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, R. L.; Gibson, S.; Linthicum, K. J. Aedes aegypti controls Ae. aegypti: SIT and IIT—an overview. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2024, 40, 32-49.

- Hendrichs, J.; Franz, G.; Rendon, P. Increased effectiveness and applicability of the sterile insect technique through male-only releases for control of Mediterranean fruit flies during fruiting seasons. J. Appl. Entomol. 1995, 119(1-5), 371-7.

- Mastrangelo, T.; Welch, J.B. An overview of the components of AW-IPM campaigns against the New World screwworm. Insects. 2012, 3(4), 930-55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enkerlin, W.; Gutiérrez-Ruelas, J.M.; Cortes, A.V.; Roldan, E.C.; Midgarden, D.; Lira, E.; López, J.L.; Hendrichs, J.; Liedo, P.; Arriaga, F.J. Area freedom in Mexico from Mediterranean fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae): a review of over 30 years of a successful containment program using an integrated area-wide SIT approach. Fla. entomol. 2015, 98(2), 665-81. [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.; Ashenafi, H.; Daya, T. A review on sterile insect technique (SIT) and its potential towards tsetse eradication in Ethiopia. Adv Life Sci Technol. 2015, 37, 24-44.

- Miller, T.A.; Miller, E.; Staten, R.; Middleham, K. Mating response behavior of sterile pink bollworms (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) compared with natives. J. Econ. Entomol. 1994, 87(3), 680-6. [CrossRef]

- Wilke, A.B.; Vasquez, C.; Carvajal, A.; Medina, J.; Chase, C.; Cardenas, G.; Mutebi, J.P.; Petrie, W.D.; Beier, J.C. Proliferation of Aedes aegypti in urban environments mediated by the availability of key aquatic habitats. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10(1), 12925. [CrossRef]

- Helinski, M.E.; Parker, A.G.; Knols, B.G. Radiation biology of mosquitoes. Malar. J. 2009, 8, 1-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asman, S.M.; Rai, K.S. Developmental effects of ionizing radiation in Aedes aegypti. J. Med. Entomol. 1972, 9(5), 468-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, T.C.; Brown, H.E. Estimating Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) flight distance: meta-data analysis. J. Med. Entomol. 2022, 59(4), 1164-70. [CrossRef]

- Mullens, P.; Su, T.; Vong, Q.; Thieme, J.; Brown, M.Q. Establishment of the Invasive Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in the West Valley Area of San Bernardino County, CA. J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58(1), 365-71. [CrossRef]

- Castellon, J.T.; Birhanie, S.K.; Macias, A.; Casas, R.; Hans, J.; Brown, M.Q. Optimizing and synchronizing Aedes aegypti colony for Sterile Insect Technique application: Egg hatching, larval development, and adult emergence rate. Acta Tropica. 2024, 259, 1073-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birhanie, S.K.; Castellon, J.T.; Macias, A.; Casas, R.; Brown, M.Q. Preparation for targeted sterile insect technique to control invasive Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in southern California: dose-dependent response, survivorship, and competitiveness. J. Med. Entomol. 2024, 61(6), 1420-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittayapong, P.; Ninphanomchai, S.; Limohpasmanee, W.; Chansang, C.; Chansang, U.; Mongkalangoon, P. Combined sterile insect technique and incompatible insect technique: The first proof-of-concept to suppress Aedes aegypti vector populations in semi-rural settings in Thailand. PLOS NTDs. 2019, 13(10), e0007771. [CrossRef]

- Balatsos, G.; Karras, V.; Puggioli, A.; Balestrino, F.; Bellini, R.; Papachristos, D.P.; Milonas, P.G.; Papadopoulos, N.T.; Malfacini, M.; Carrieri, M.; Kapranas, A. Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) field trial targeting the suppression of Aedes albopictus in Greece. Parasites Vectors. 2024, 31. [CrossRef]

- Dallimore, T.; Goodson, D.; Batke, S.; Strode, C. A potential global surveillance tool for effective, low-cost sampling of invasive Aedes mosquito eggs from tires using adhesive tape. Parasites Vectors. 2020, 13, 1-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Park, A.; Che-Mendoza, A.; Contreras-Perera, Y.; Pérez-Carrillo, S.; Puerta-Guardo, H.; Villegas-Chim, J.; Guillermo-May, G.; Medina-Barreiro, A.; Delfín-González, H.; Méndez-Vales, R.; Vázquez-Narvaez, S. Pilot trial using mass field-releases of sterile males produced with the incompatible and sterile insect techniques as part of integrated Aedes aegypti control in Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022, 16(4), e0010324. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Aldridge, R.L.; Gibson, S.; Kline, J.; Aryaprema, V.; Qualls, W.; Xue, R.D.; Boardman, L.; Linthicum, K.J.; Hahn, D.A. Developing the radiation-based sterile insect technique (SIT) for controlling Aedes aegypti: identification of a sterilizing dose. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79(3), 1175-83. [CrossRef]

- Lees, R.S.; Gilles, J.R.; Hendrichs, J.; Vreysen, M.J.; Bourtzis, K. Back to the future: the sterile insect technique against mosquito disease vectors. Curr. Opin. Insect. Sci. 2015, 10, 156-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, C.F.; Benedict, M.Q.; Collins, C.M.; Baldet, T.; Bellini, R.; Bossin, H.; Bouyer, J.; Corbel, V.; Facchinelli, L.; Fouque, F.; Geier, M. Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) against Aedes species mosquitoes: A roadmap and good practice framework for designing, implementing and evaluating pilot field trials. Insects. 2021, 12(3), 191. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).