1. Introduction

Malaria remains a significant public health challenge, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions where mosquitoes are prevalent. Effective management of this disease requires a comprehensive approach that combines mathematical modelling with optimal control strategies to enhance insecticide susceptibility in mosquito populations. In addition, raising community awareness of the dynamics of malaria transmission is crucial in reducing infection rates and promoting preventive measures. According to the World Malaria Report in [

1], malaria continues to inflict unacceptable levels of illness and mortality. The most recent study estimates that as of April 18-20, 2023, there were 608,000 fatalities and 249 million cases worldwide. Since malaria is preventable and treated, lowering the burden of the disease and the death rate while maintaining the long-term goal of eliminating malaria should be a top priority for the entire world. Plasmodium parasites are the cause of malaria, and female Anopheles mosquitoes carry the disease. P. falciparum is the most harmful of the four species of malaria that affect humans. P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. ovale. Of these, P. falciparum and P. vivax are the most common.Human infections with the zoonotic plasmodium P. knowlesi are also known to occur. Despite these advances, endemic malaria continues to exist in the six WHO areas, with the African Region bearing the brunt of the disease burden; an estimated 90% of all malaria deaths occur there. Two countries, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, account for about 40% of the global malarial fatality rate projected. Millions of people around the world lack access to malaria prevention and treatment, and the majority of cases and deaths go unreported. As the world population grows by 2030, more people will live in countries where malaria is a risk, further taxing the finances and health systems of the national malaria program [

2].

Moreover, mosquito species like Anopheles and Culex are able to proliferate as they develop from larvae to adults due to the chemical insecticides (adulticides and lecticides) inadequate targeting of breeding habitats and residential areas [

3,

4,

5]. Furthermore, parasites that feed on blood supply and guarantee hatchability are seen in female Anopheles gambiae and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes. Furthermore, according to [

6], disease is transmitted via vectors because of their increasing resistance to common pesticides. Additionally, studies on community host awareness and chemical pesticide sensitivity status have been conducted worldwide [

7]. Despite the fact that no such study has been published, these frequent diseases spread by mosquitoes are becoming more prevalent worldwide. This is the first study to examine the most effective ways to control mosquito susceptibility to three distinct chemical insecticides: the usual technique (media campaign), propoxur (carbamate), permethrin (pyrethroids), and malathion (organophosphates). However, only a small number of nations have conducted prior tests on mosquitoes worldwide using the pyrethroid chemical insecticide components deltamethrin and permethrin. Nonetheless, the pesticides were suggested to be considered for the current investigation because of their resistance and long testing cycles. The dynamics of optimisation approaches are also used in this study to provide the model formulation in terms of optimal control theory. In this situation, the best control method provides powerful tools for creating and evaluating control plans in many scenarios. According to [

8], there is evidence that malaria cases tend to cluster more when transmission levels are decreasing and get closer to zero. People who are exposed at the same time and place, like through a common vocation or shared travel to endemic areas, may cluster geographically, in small areas like households and neighbourhoods, or socially [

9]. Malaria transmission at the community level may be decreased if clusters can be located and effectively targeted with interventions. Furthermore, in order to manage and measure mosquitoes and consequently reduce the transmission of related diseases, Hafez and Abbas, (2021) in [

10] investigated insecticide resistance to insect growth regulators in Saudi Arabia. Over 700,000 people die each year from vector-borne infectious diseases, of which over 400,000 are from malaria alone. These infections are a major cause of death worldwide. Anopheles gambiae is a common mosquito species that is the main vector for human malaria transmission (Helmi, 2024) in [

11]. In order to create a mathematical model, [

12] combined three control strategies: mass awareness, treatment, and vector control. According to the results, the control of dengue fever is more effectively achieved when vector control, treatment, and public awareness are combined than when these interventions are used alone or in combination. Additionally, [

13] examined the impact of abiotic parameters and species associations on the abundance of seven mosquito species in Spain’s Donana National Park. They evaluated the effects of abiotic parameters and species-to-species associations, which acted as stand-ins for species interactions, and developed three models with different parameters. A fractional order model for the transmission dynamics of malaria was constructed, according to [

14], and it included two control strategies: the use of pesticides and health education campaigns. The findings indicated that the population’s exposure to malaria had been considerably reduced.

Thus, [

15] developed a mathematical model to investigate the dynamics of malaria transmission in the presence of parasites and mosquitoes resistant to antimalarial drugs. A mathematical model for analysing the dynamics of malaria transmission is developed by [

16]. In addition to affecting illness outcomes and healthcare systems, it takes into consideration consequences such as severe anaemia and organ failure. For malaria therapies to be effective, the results highlight the necessity of better vector management and complication control. A mathematical model of malaria transmission dynamics that is non-linear and deterministic was also proposed and examined by [

17]. The ideal model’s results indicated that integrated control measures are superior to a single intervention for the eradication of malaria.[

18] creates a compartmental model to assess how early and late treatment interventions affect the spread of malaria in children under

in order to inform efficient control measures. To examine the dynamics of malaria illness transmission and pesticide control strategies, [

19] developed a mathematical model. The results were presented in a visual format. Insecticide spray has been shown to significantly affect the spread of malaria. Taking into consideration time-dependent treatment, immunisation, and ambient sanitation measures, Olaniyi,

et al., (2025) in [

20] developed a novel mathematical model for RVF. The results of the study shed light on the long-term dynamics of RVF in the community and provide effective preventative and control strategies with low intervention costs. To further reduce transmission between human populations and mosquitoes, Baroudi, em et al., (2025) in [

21], provide an ideal approach that consists of health interventions, safety precautions, and awareness campaigns in dengue endemic areas. [

22] created a model in mathematics. Numerical simulations were used to validate the analytical findings. According to the study’s findings, combining an ideal control plan with social media awareness efforts is the most economical way to treat malaria. Moreover, [

23] developed a mathematical model of the best control method for biological and chemical management of mosquito populations. The results show two options with the best cost-effectiveness metrics and provide some useful information for their possible use in practical situations. A compartmental model was developed by [

24] to demonstrate the spread of co-infection between cholera and malaria. The vector control method is the most efficient strategy to minimise the amount of new interactions, as the numerical results show. The application of a residual insecticide to the interior surfaces of walls, ceilings, windows, and doors is known as indoor residual spraying (IRS), and it is used to eliminate mosquitoes that are at rest and lessen the spread of malaria. Prior to the spread of malaria, the IRS, lasting nets insecticide (LNI), and traditional techniques are typically applied in the form of a campaign over a substantial region or a higher-risk region. Thus, it is advised that IRS, LNI, and traditional techniques be used in the homes of a confirmed case and their neighbours at roughly the same time [

2].

The study is divided into a number of components, beginning with an introduction outlining the significance and goals of the paper. A thorough methodology section that describes the mathematical model and control techniques used to evaluate pesticide susceptibility comes next. Findings from the modelling analysis and community surveys are presented in the results section, and their interpretation in relation to malaria awareness and control is discussed.

The aim of the paper is to develop a mathematical model that predicts how insecticide susceptibility in mosquito populations affects malaria transmission dynamics. Additionally, the study seeks to assess the impact of community awareness initiatives on reducing the spread of malaria. Through this approach, the paper intends to provide insights for creating more effective vector control strategies and public health interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

The model is formulated by incorporating variables that represent the insecticide susceptibility status of mosquito populations and the level of community awareness about malaria prevention. Differential equations are used to describe the dynamics of mosquito populations, taking into account factors such as birth and death rates, as well as the impact of insecticide use. Additionally, parameters related to community education initiatives are included to assess how increased awareness can influence the effectiveness of malaria control strategies.

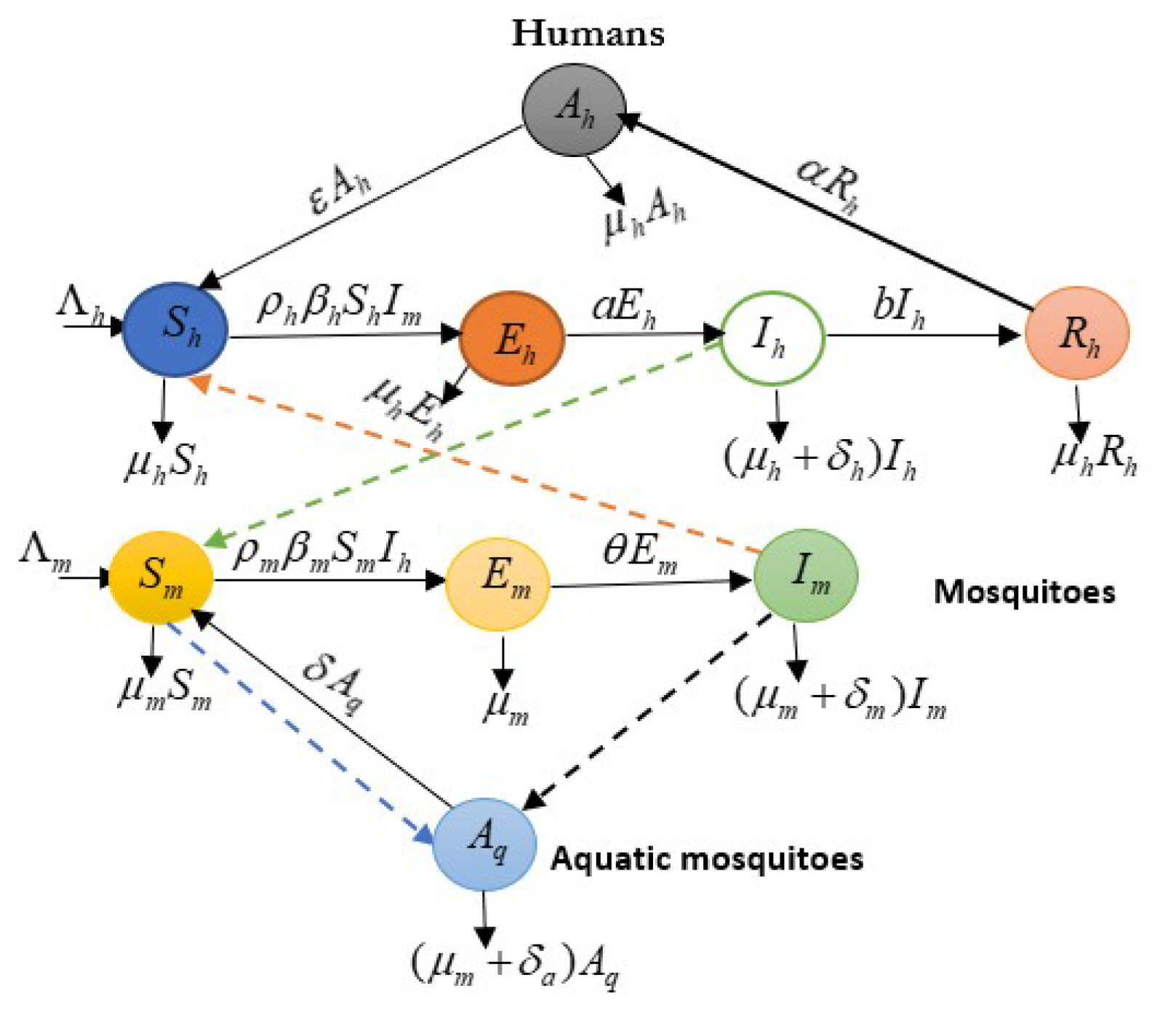

Therefore, the diagram can also be used to identify areas where controls may be most effective, which can be seen in

Figure 1 as follow;

Figure 1.

Diagram of a Malaria Transmission. Source: Authors.

Figure 1.

Diagram of a Malaria Transmission. Source: Authors.

Table 1.

Description of Variables.

Table 1.

Description of Variables.

| Variables |

Biological description |

|

The number susceptible humans with time |

|

The number of aware humans with time |

|

The number of exposed humans with time |

|

The infectious humans with time |

|

The recovered humans with time |

|

The number of adult healthy mosquitoes with time |

|

The number of exposed mosquitoes with time |

|

The number of infectious mosquitoes with time |

|

The number of Aquatic mosquitoes (eggs, larvae, pupae) with time |

Table 2.

Description of Parameters.

Table 2.

Description of Parameters.

| Parameters |

Biological description |

|

Recruitment per-capita rate of susceptible humans |

|

Recruitment per-capital rate of susceptible mosquitoes |

|

Rate of aware human return to susceptible humans |

|

Rate of recovered human become aware humans |

|

Natural death rates of all humans |

|

Natural death rates of all mosquitoes |

|

Transmission rates per-capita of humans |

|

Transmission rates per-capita of mosquitoes |

|

Per- capita contact rates of human with infected mosquitoes |

|

Per- capita contact rates of healthy mosquitoes with infectious humans |

| a |

Rates of exposed human move to infectious humans |

| b |

Rate of recovered humans |

|

Progression rate of exposed mosquitoes become infectious mosquitoes |

|

Disease induced-mortality rate of infectious human |

|

Proportion rate of the oviposition |

|

Proportion rate of non-infected eggs laid by infected mosquitoes. |

|

Proportion rate in which mosquitoes mature |

|

Mortality rate of infectious mosquitoes due to human activities |

|

Mortality rate of aquatic mosquitoes due to human activities |

2.1. Model Assumption

The model assumes that the mosquito population is homogeneously mixed, meaning that each mosquito has an equal chance of coming into contact with an insecticides. It also presumes that community awareness efforts are uniformly distributed and have a consistent impact on reducing malaria transmission. Furthermore, the model considers environmental factors to be constant over time, allowing for a focus on the interactions between control measures and mosquito behaviour. It assumed that the human and mosquito populations are divided into separate classes, with each distinct one assigned to only one class at a time. In this study, mosquitoes go through an aquatic (water-based) stage before becoming adults with the rate . Only adult mosquitoes are capable of transmitting malaria. It is assumed that malaria spreads through bites?susceptible humans can get infected by bites from infectious mosquitoes, and mosquitoes can become infectious after biting infected humans. Also assumed that the people who recover from malaria may become more aware of the disease and help increase overall community awareness. Therefore, insecticide use increases the death rate of mosquitoes, especially those that are infected. Finally, the community awareness helps reduce the likelihood of people getting infected by promoting protective actions and behaviours.

2.2. Model Description

Susceptible humans

; are humans who have not yet been infected with malaria but are at risk of contracting the disease. These humans are increasing the population through immigration and birth rate. Then decreasing the population through the infectious mosquito rate and the natural death rate of mosquitoes, which gives;

Aware humans

;these population increasing through recovered rate of human and decreasing to susceptible human class. This class are knowledgeable about the life cycle of mosquitoes and the role they play in malaria transmission, thus;

Exposed humans

; are individuals who have been bitten by mosquitoes carrying the malaria parasite but have not yet developed symptoms of the disease. This class increasing through contact rates of human with mosquitoes and decreasing with some rates move to infectious human, gives;

Infectious humans

; play a crucial role in the transmission dynamics of malaria, as they serve as hosts for the malaria parasites. When a mosquito bites an infectious human, it can acquire the parasites, which then develop within the mosquito before being transmitted to other humans, thus;

Recovered human

; a recovered human in this context refers to an individual who has successfully overcome a malaria infection and is now immune to the specific strain they encountered. thus;

Susceptible mosquitoes

; are those that are vulnerable to the effects of insecticides, meaning they can be effectively controlled or eliminated through chemical interventions, gives;

Exposed mosquitoes

; are those that have come into contact with insecticides but have not yet succumbed to their effects, thus;

Infectious mosquitoes

are produced by the maturation of infected aquatic mosquitoes and the infection of susceptible mosquitoes. thus;

Aquatic mosquitoes

; increasing via oviposition by

and infectious

mosquitoes at

and

respectively, where

is the oviposition rate while

is a proportion of non-infected eggs laid by infected mosquitoes. It decreases through mature mosquitoes at a rate

, die naturally at

and mortality rate at

, thus;

The following non-linear differential equations represent the model description for the transmission of mosquito diseases in the community and correspond to the model diagram in

Figure 1, gives;

with the initial conditions;

, and .

2.3. Basic Properties of the Model

The basic properties of the model include the parameters that govern the interaction between mosquitoes and humans, such as transmission rates and insecticide effectiveness. The feasible region defines the set of all possible states of the system, ensuring that population sizes remain non-negative and within biologically realistic limits. The invariant region refers to a subset of the feasible region where the system’s dynamics are constrained to remain over time, reflecting stable population levels and effective malaria control.

2.3.1. Feasible and Invariant Region

The feasible region in this context refers to the set of all possible solutions that satisfy the constraints of the model. Therefore, using the idea of Haile,

et al., (2025) in [

25] as system (

1) will be examined and divided into two, which are both human and mosquito classes, respectively, and given as

Theorem 1. Let system (1) be the set of then the feasible region Ω contain the all solution.

Proof of Theorem 1. Suppose

, then

. To examined the dynamics of system (

1), the

is positively invariant. This region is determined by considering the entire human population.

=

Combining the system (

1) of the first five equations and differentiating both sides with respect to

t yields;

This implies that;

Thus;

Integrating and simplifying both side of equation (

3), obtain;

Where

is constant value. Using the initial condition, rearrange equation (

4), give;

Thus, as

, the total human population

, which indicates that

The invariant region of system (

1) for the human population therefore yields:

Thus, is positively invariant. Subsequently, the total population of mosquito in system (

1) follow as;

Also, differentiating both side of equation (

7) w.r.t,

t obtain;

Solving equation (

9), gives

Hence, the invariant region of system (

1) for mosquito population gives;

Therefore, the invariant region of the whole system (

1) is given as;

The prove is complete and is positively invariant. Finally, all the solution set of system (

1) is bounded in

□

2.3.2. Positivity of the Model Solutions

Suppose

, for all solution to system (

1) with positive initial conditions will stay positive .

Theorem 2. System (1) can be solved as follows, given positive initial conditions; and with positive initial conditions. Also, and remains positive for all .

Proof of Theorem 2. Assume that every state variable in system (

1) is positive. Starting with (

1), the first equation of system (

1) is

,

this implies;

Integrating by applying the method of separation of variable along with initial condition, gives;

Also, in the second equation of system (

1) as

; this implies;

Integrating the both side and applying initial condition, gives;

The third equation in the system (

1) , as

, and implies;

Integrating the both side and applying initial condition, gives;

Furthermore, by applying initial condition on all the equations of system (

1), obtains;

Thus, the system (

1) is mathematically well posed (Hethcote, 2000) in [

26]. This complete the prove. □

2.4. Mosquito Disease Free Equilibrium Points

The Mosquito Disease Free Equilibrium Point (DFEP) refers to a state where the mosquito population is present, but there are no cases of the disease being transmitted within the community, meaning

. The disease free equilibrium in the system (

1) is determined using Maple23 software to identify and set all the model equations to zero.Thus, the disease-free equilibrium point of system (

1) is given as

. Also, this implies that the disease-free equilibrium is given by;

2.5. Endemic Equilibrium Point

At the endemic equilibrium, the population dynamics of mosquitoes and the incidence of malaria cases reach a steady state. This balance reflects a consistent rate of transmission and infection, where the number of new cases is equal to the number of recoveries or deaths. Modelling this equilibrium is crucial for designing effective control strategies that can reduce the prevalence of malaria in affected communities and is denoted as .

Therefore, EEP are as follows;

2.6. Reproduction Number

The Basic Reproduction Number, often denoted as

, is a key epidemiological metric used to describe the contagiousness or transmissibility of infectious agents. It represents the average number of secondary cases generated by one primary case in a completely susceptible population. Understanding

helps in assessing the potential spread of malaria and the effectiveness of control measures. The following result is produced by standard method in [

27,

28].

Considering the infected classes, which are and , gives;

and .

Solving the Jacobian of matrices f and v, then differentiating w.r.t and , gives;

and

.

Therefore, using the method in [

29,

30], the result follows as;

Subsequently;

Therefore, the basic reproduction number of the model system (

1) is denoted by

=

, where

is the spectral radius of the product

, which gives;

Where;

.

Therefore, by further simplification, the basic reproduction number

, gives;

2.7. Local Stability of Disease Free Equilibrium

The local stability of the disease-free equilibrium is crucial in understanding how effective control measures can be in eradicating malaria. A disease-free equilibrium is stable when the basic reproduction number, , is less than one, indicating that the infection will eventually die out. Mathematical models can help identify conditions under which this stability is achieved, guiding strategies for insecticide use and community education efforts. The following theorem analyses the local stability of DFE.

Theorem 3. The DFE of system (1), denoted by , is unstable if and locally asymptotically stable (LAS) in Ω if .

Proof of Theorem 3. At disease-free equilibrium

the Jacobian matrix

is gives as;

The eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix are given by finding the characteristic polynomial, which follow as;

, obtain;

The focus is on

matrix, by considering the rows and columns due to the presence of zeros in the reduction process of equation (

29), gives;

The characteristic polynomial of Jacobian matrix in equation (

30), is given by;

Where;

Thus, from first expression of equation (

31);

and

Subsequently, the second expression of equation (

31) can also be in the form of quadratic expression, which is;

Where;

Applying the Routh-Harwitz criteria in [

25,

31] and by the principle of equation (

31), all the real root of the equation has strictly negative and iff

, Then

.This shown that

because it is the sum of positive parameters [

25,

31]. Hence, the DFE is locally asymptotically stable if

.

However, when

, this shows that

and by Descartes’s rule of signs in [

25] there is exactly one sign change in the coefficient of the characteristic polynomial in equation (

31). So, there is one eigenvalue with positive real part and DFE is unstable. Hence the proved. □

2.8. Global Stability of Disease Free Equilibrium

The global stability of the disease-free equilibrium is crucial for ensuring that malaria transmission can be effectively eradicated. The disease-free state remains stable despite potential perturbations. This involves ensuring the basic reproduction number is less than one, indicating that malaria cannot sustain itself within the community.

Theorem 4. If , the disease-free equilibrium for system (1) is globally asymptotically stable in the feasible region.

Proof of Theorem 4. Using the idea of Haile,

et al., (2025) in [

25] to proof the theorem . The Lyapunov function method is then used to generate an appropriate Lyapunov function

following the procedure described in [

25]. This will show the global asymptotic stability of the equilibrium point.

Let the Lyapunov function be

, where

and

are non-negative constant and

and

non-negative infected classes. Then differentiate the Lyapunov w.r.t time, which gives;

Putting the values of

and

of system (

1) to equation (

33) by solving it and collecting like terms of the equation, obtain;

.

This implies;

.

Subsequently;

Taking the coefficient of

and

and obtain;

From the coefficient of

, which is

, this implies that;

. Also, the coefficient of

, gives;

, and implies that;

. The coefficient of

, have;

, putting

in the coefficient of

, gives;

and further simplification, resolved as;

Therefore by substituting

and equation (

35) into equation (

34), gives;

Further simplification gives;

Where;

and

Suppose

, then;

Thus, if

, then

. Therefore,

. Furthermore,

iff

, this shows that DFEP,

is globally asymptotically stable (GAS).

Remark 1.If , the disease-free equilibrium is stable and the endemic equilibrium is absent, according to the stability analysis of the reproduction number.

Remark 2.In the event where , the endemic equilibrium may exist and be stable, while the disease-free equilibrium is unstable. Hence the proved.

□

3. Sensitivity Analysis of the Model Using

Sensitivity analysis of the model using the basic reproduction number, , helps identify which parameters most significantly affect the spread of malaria. By analysing how variations in respond to changes in different parameters, researchers can pinpoint key areas for intervention. This information is crucial for optimizing control strategies and improving the effectiveness of insecticide use and community awareness programs.

Sensitivity analysis was used, following the methods described in [

32], to ascertain the relative influence of each parameter on the spread of malaria. The normalised forward sensitivity index, as described in [

33], is a variable

that depends on the differentiable parameter

. The analytical outcome of the sensitivity analysis of

is obtained by computing

to each of the parameters contributing to

. Thus, each of the fundamental parameters in

has the following sensitivity;

.

3.1. Interpretation of the Sensitivity Index

The sensitivity index provides insight into which parameters have the most significant impact on the model outcomes. By analysing these indexes, researchers can identify which factors most strongly influence mosquito susceptibility to insecticides and the effectiveness of community awareness programs. This understanding helps in prioritising interventions and resources for more effective malaria control strategies. The sensitivity index in

Table 3 for

shows the expansion of mosquitoes in the community was significantly influenced by the parameters with positive index, which are

and

. As their values increase, the burden on mosquitoes in the community is reduced by parameters with negative index

and

.

In order to combat disease in a community, the sensitivity technique showed that public health sectors and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) should use control tactics to decrease positives and improve control of negative index values. The following part examines an optimal control model in light of this observation in order to determine the best strategy for controlling diseases spread by mosquitoes.

4. Optimal Control Technique

The optimal control technique involves using mathematical models to determine the best strategies for managing mosquito populations and reducing malaria transmission. By adjusting variables such as the timing and quantity of insecticide application, this can minimize mosquito resistance while maximizing the effectiveness of control measures. This approach also considers community awareness programs to enhance public participation and improve overall outcomes in malaria prevention [

32].

According to [

20,

34,

35], the optimal control model is a powerful mathematical technique that may be used to complex situation analysis. According to [

36], the control influences the dynamics of the system by entering the model equations for the ordinary differential equations. The goal is to modify control in order to maximise or minimise a particular functional aim. Similar to this, the problem requires a set of control variables,

, a collection of state variables,

, and a cost function,

, for a time

, where

and

are the beginning and ending times, respectively.

The desired outcome is to determine a control and the related state variables in order to minimise a given objective function. The optimal control approaches in this study focuses as;

- (i)

: malathion, propoxur and permethrin chemical ingredients,

- (ii)

: lasting nets insecticides (INI) and

- (iii)

: traditional techniques.

The non-linear differential equations corresponds to the malaria transmission model diagram in

Figure 1 and integrated optimal control technique, gives;

with the initial conditions;

, and .

In order to minimise the cost of control

and to determine the optimal control values, equation (

39) aims to minimise the total number of exposed individuals, infected individuals, and mosquitoes.

of the controls

such that the associated state trajectories

are optimal control with initially conditions. The following is the objective function;

Subject to (

41), where

regards as final time and

with

and

are positive weight constants and the choice of this study control agree with the idea in [

37,

38]. The

are the costs associated with the use of malathion, propoxur and permethrin chemical ingredients, lasting nets insecticides (LNI), and traditional techniques. Consequently, the objective function makes it possible to maximise the Hamiltonian related to the optimum control problem. Afterwards, an optimal control

, and

satisfying equation (

39) was obtained using the Pontryagin maximum principle [

39];

Where

such that

are measurable with

for

is the control set. The controls

In [

40], are bdd Lebesgue integrable functions?

are optimal controls that meet the requirements of Pontryagin’s maximal principle [

41]. Equations (

39) and (

40) are transformed into a pointwise Hamiltonian

H minimisation problem using this method, which yields the controls

. The Hamiltonian derived from the cost functional of equation (

40) and the governing dynamics of equation (

39) is used to determine the optimality conditions. Consequently, the following is the Hamiltonian

H;

Where

are the adjoints that correspond to the state variables. Taking into account, the equation (

42) can be solve through appropriate partial derivatives of the Hamiltonian to the associated state variable.

Theorem 5. Using the idea in [42,43]. Let the optimal control and and have a solution of the corresponding state variables that minimize J over U, and adjoint variables satisfying .

Proof of Theorem 5. According to [

39], the integrand of the objective functional

is a convex function of

and

. The system satisfies the Lipshitz property with regard to the variables

and

and

since the solution of (

39) is bounded. Consequently, the optimal include

exists. By differentiating the Hamiltonian function and evaluating it at the optimal control, the governing equations of the adjoint variables are derived. The adjoint system can therefore be expressed as;

The transversality conditions are given as;

= 1,...,9.

Thus, the result give the control measure as set , which follows with transversality conditions , and the set of control as , gives;

Thus, the arguments, gives;

Therefore;

Furthermore, a sufficient condition for the Hamilton function’s second derivative with respect to

. This implies that

and

This indicates that the optimal problem is minimised at

.

Combining the established control set with the initial and transversality conditions allows one to predict the model equations with optimal control strategies in (

39) and the adjoint variable as:

This complete the proved. □

6. Results and Discussion

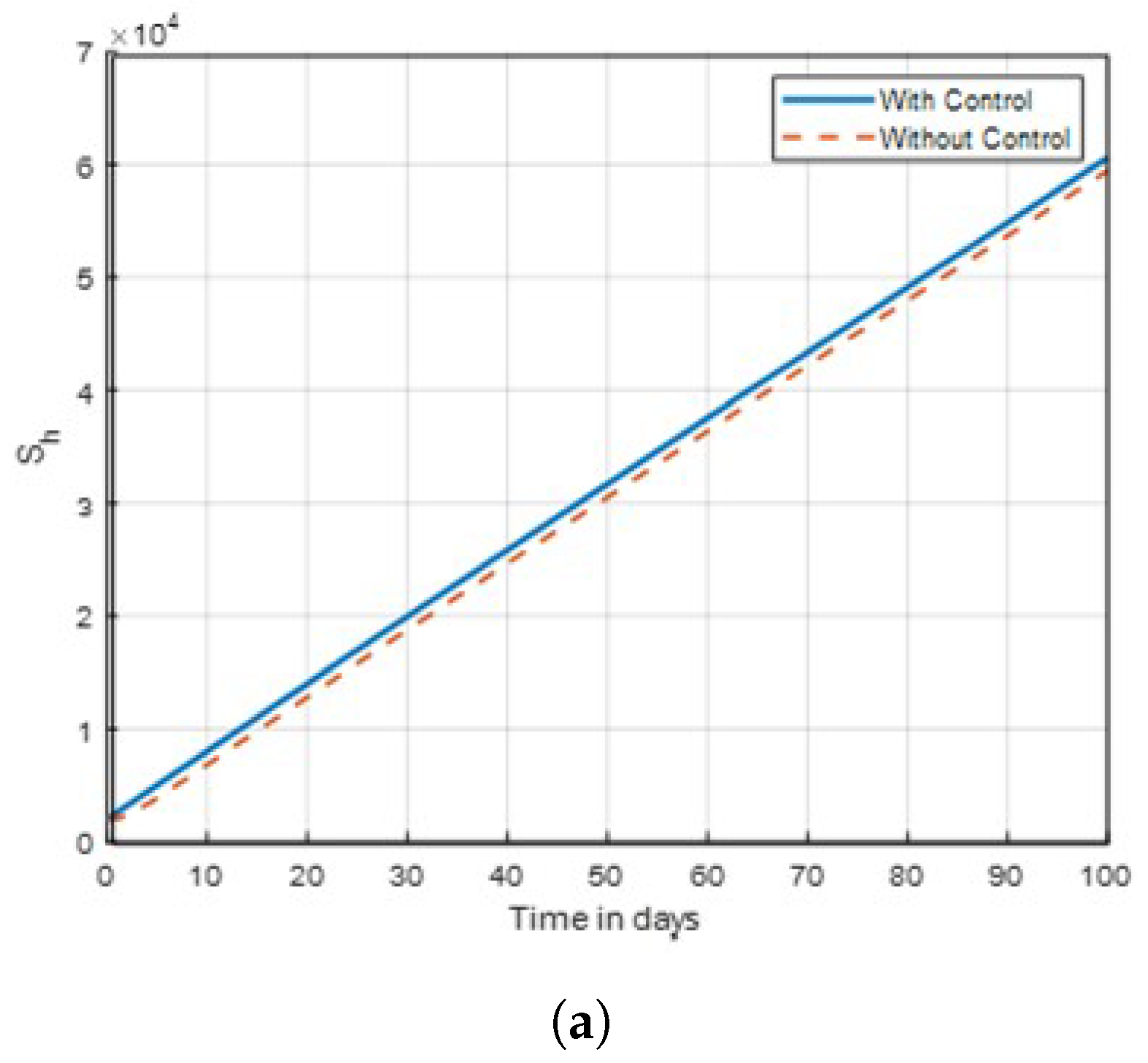

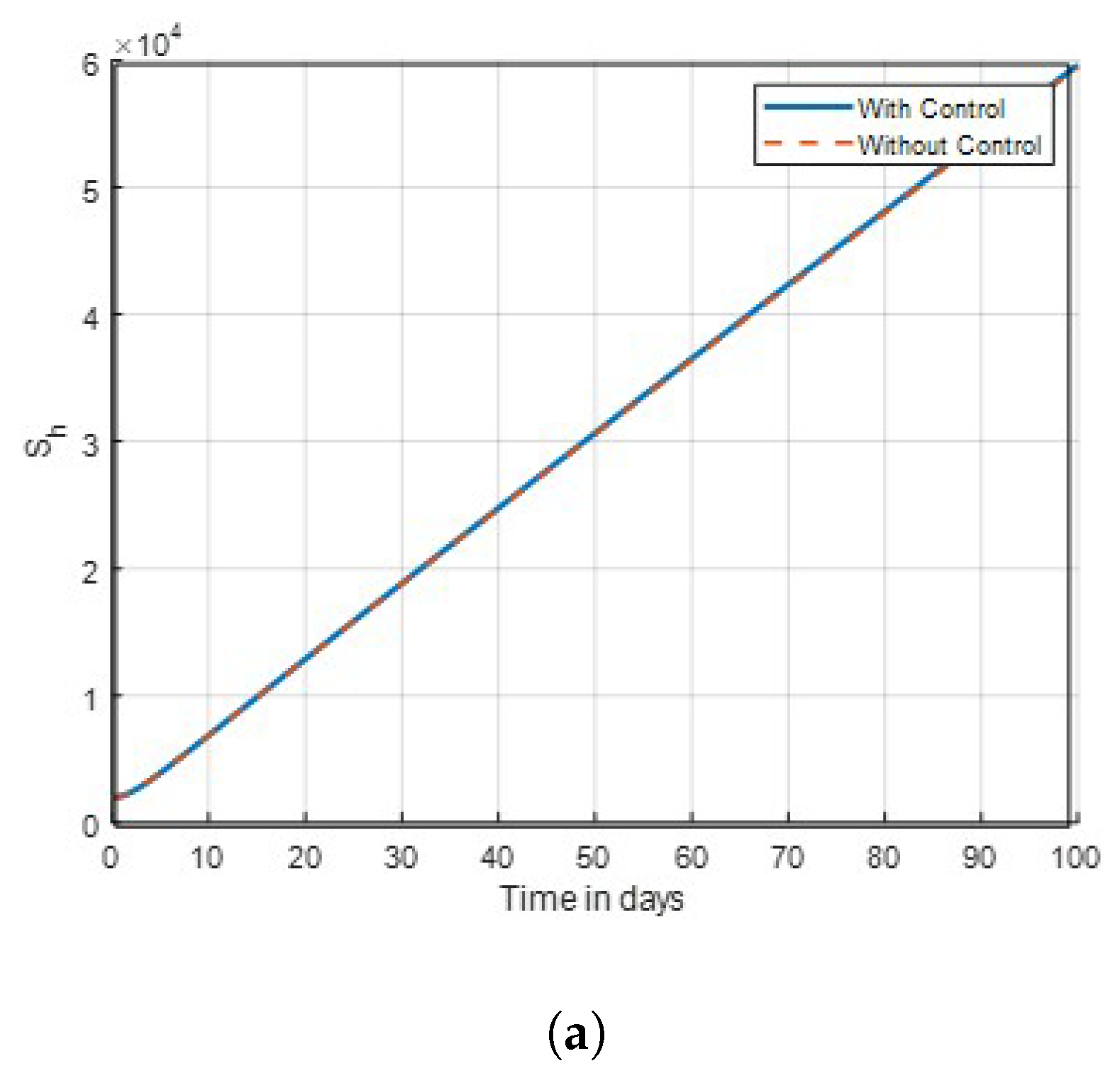

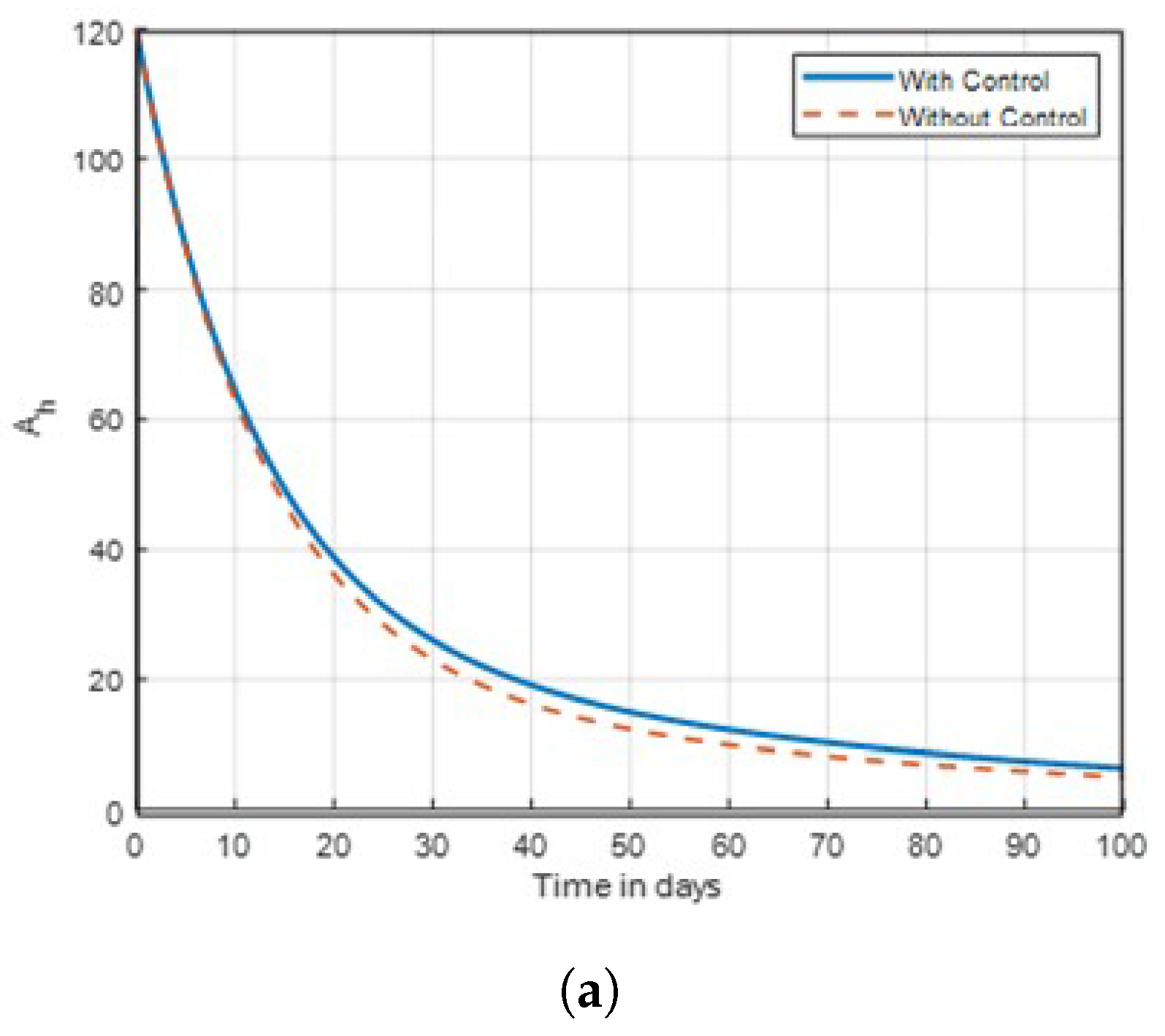

The results indicate that implementing optimal insecticide application strategies can significantly reduce mosquito populations while minimising resistance development. Additionally, enhancing community awareness about malaria transmission dynamics leads to more effective control measures and increased participation in prevention efforts. The combination of these strategies creates a synergistic effect, improving overall public health outcomes in malaria-endemic regions. The sensitivity of mosquitoes strains to insecticides and traditional method, was examined. In

Figure 2, the combined control result of the investigation showed that mosquitoes revealed no possible resistance to malathion, propoxur and permethrin as

in this studied. It was also found that control

showed no significant difference on susceptible unaware human, as shown in

Figure 3. Subsequently, the result investigation revealed that

and

was found to be very effective toward mosquitoes in this study and agrees with the studies in [

14] that found insecticide and awareness to be very active against the mosquito vector tested. The community awareness on mosquitoes is effective via campaign on mosquitoes to combat malaria, and can be deduced from

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 of the recovered individuals. Furthermore, the findings shows from

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 that employed a mathematical model to examine the resistance patterns of mosquitoes to commonly used insecticides, traditional method and evaluated the community’s awareness and practices related to malaria prevention proved to be effective. Based on the findings, it is recommended to implement targeted insecticide rotation strategies to manage resistance in mosquito populations effectively. Additionally, enhancing community education programs about malaria transmission through media campaign can increase awareness and encourage proactive participation in prevention efforts. Collaborative efforts between researchers, public health officials, and local communities are essential for sustainable control and reduction of malaria cases.

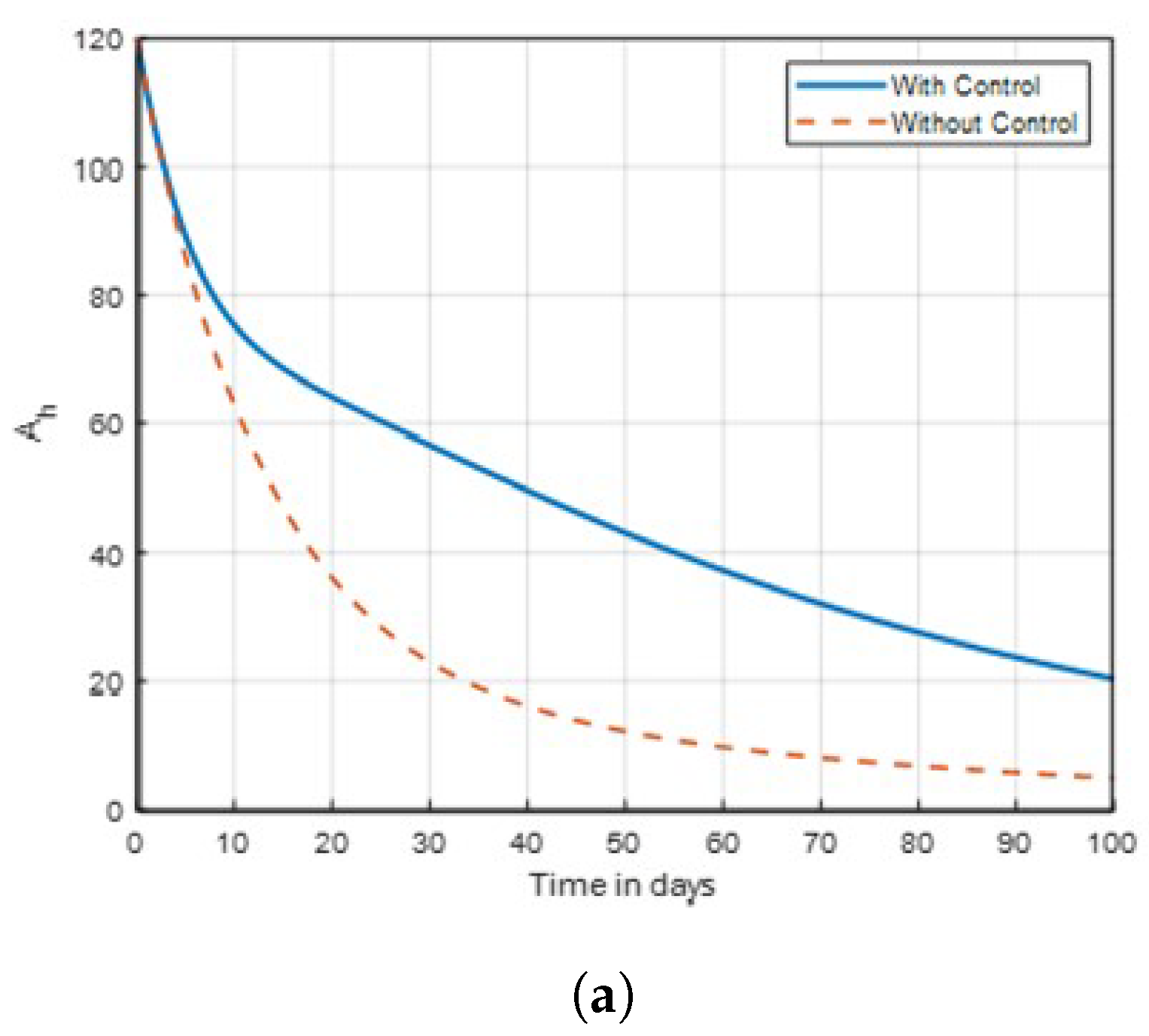

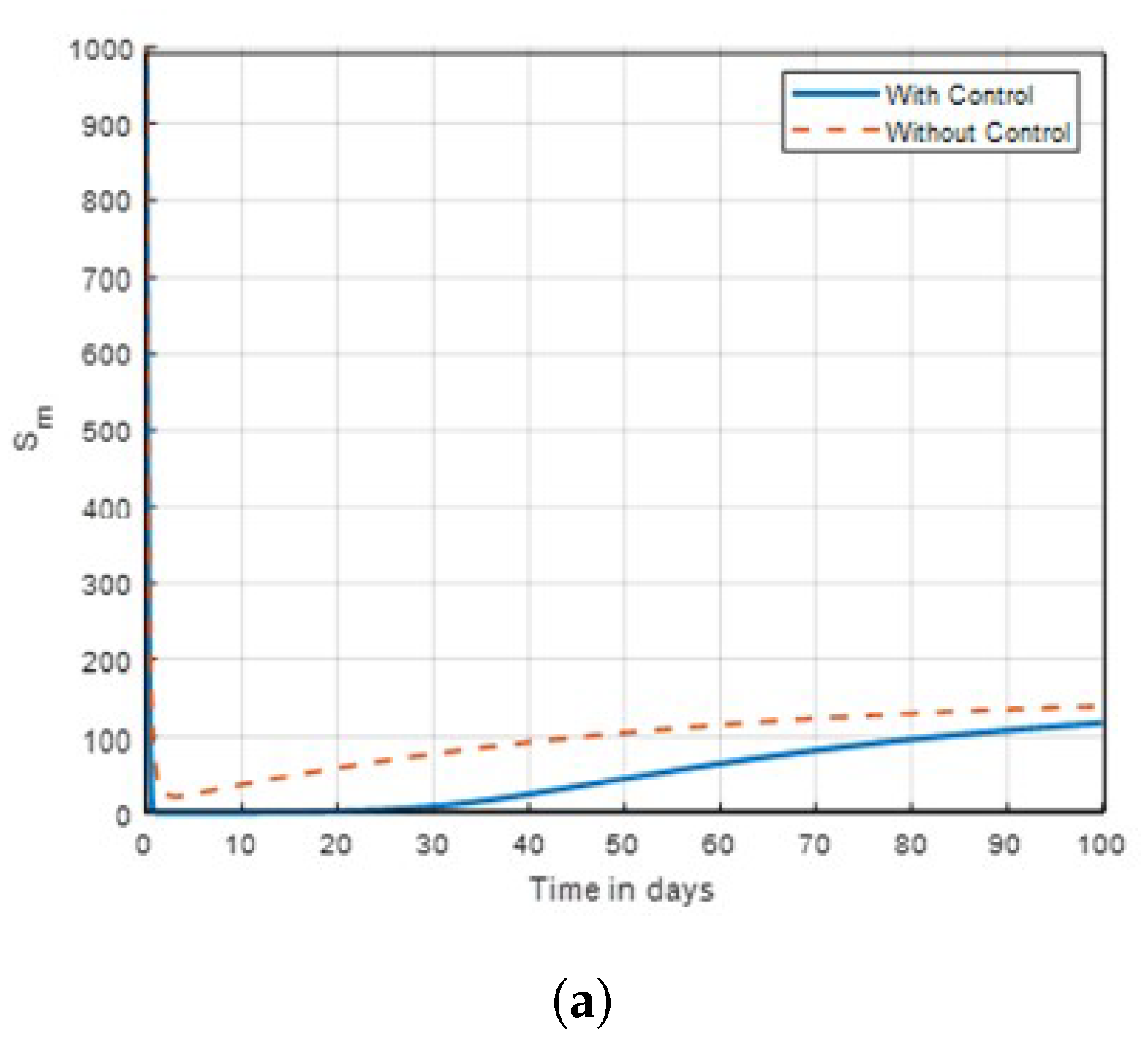

Strategy A:

. The objective function

J is optimised using controls

, while

and

are set to zero in this method. In this case, the aim is to check the contribution of each combination intervention in reducing the mosquitoes and malaria transmission rate in a community. The results are shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 18 where the combination of

(malathion, propoxur, and propoxur) is effective on susceptible,exposed, infected and aquatic mosquitoes, respectively. Also, from

Figure 16, it can be deduced that only the insecticide

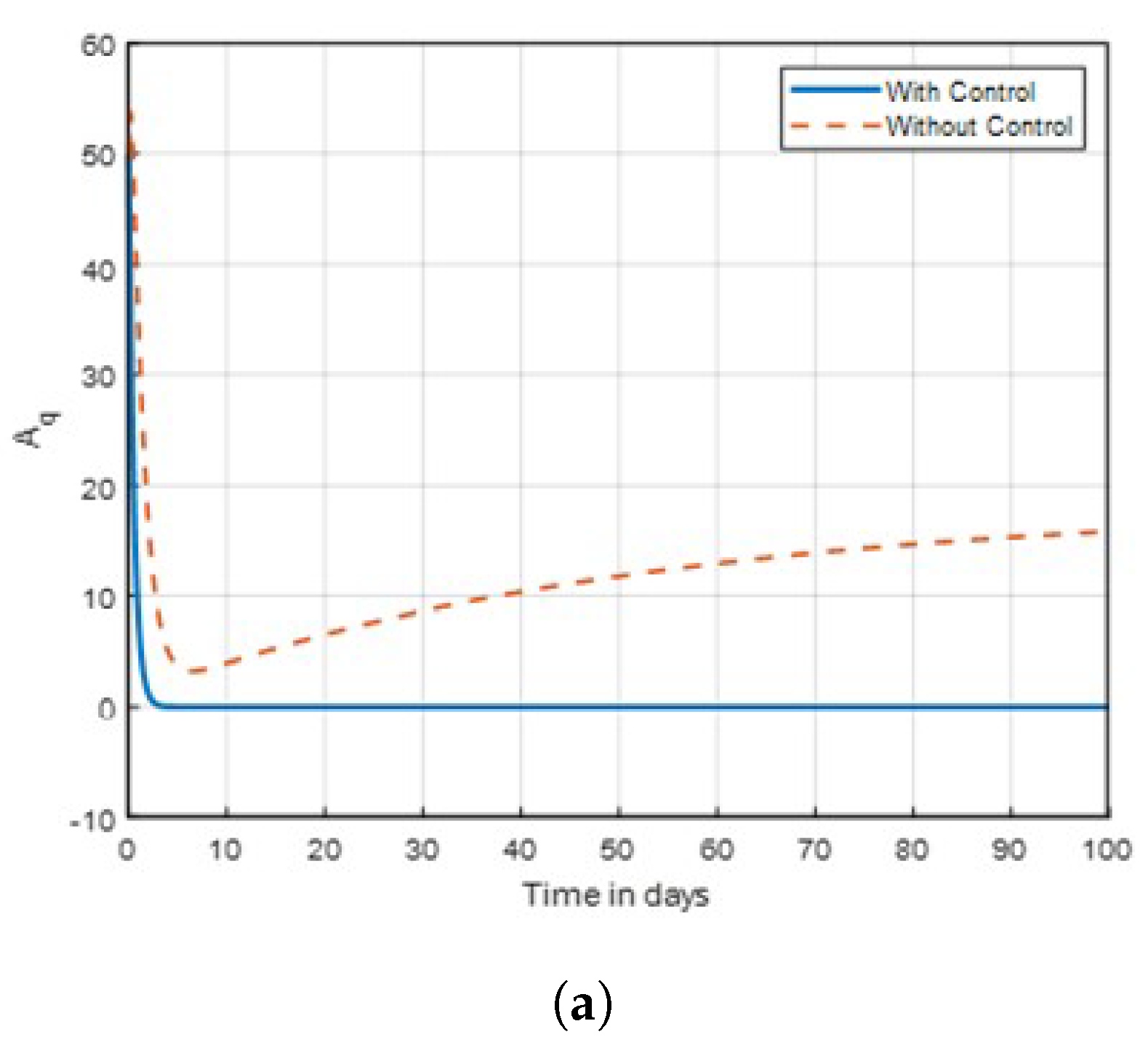

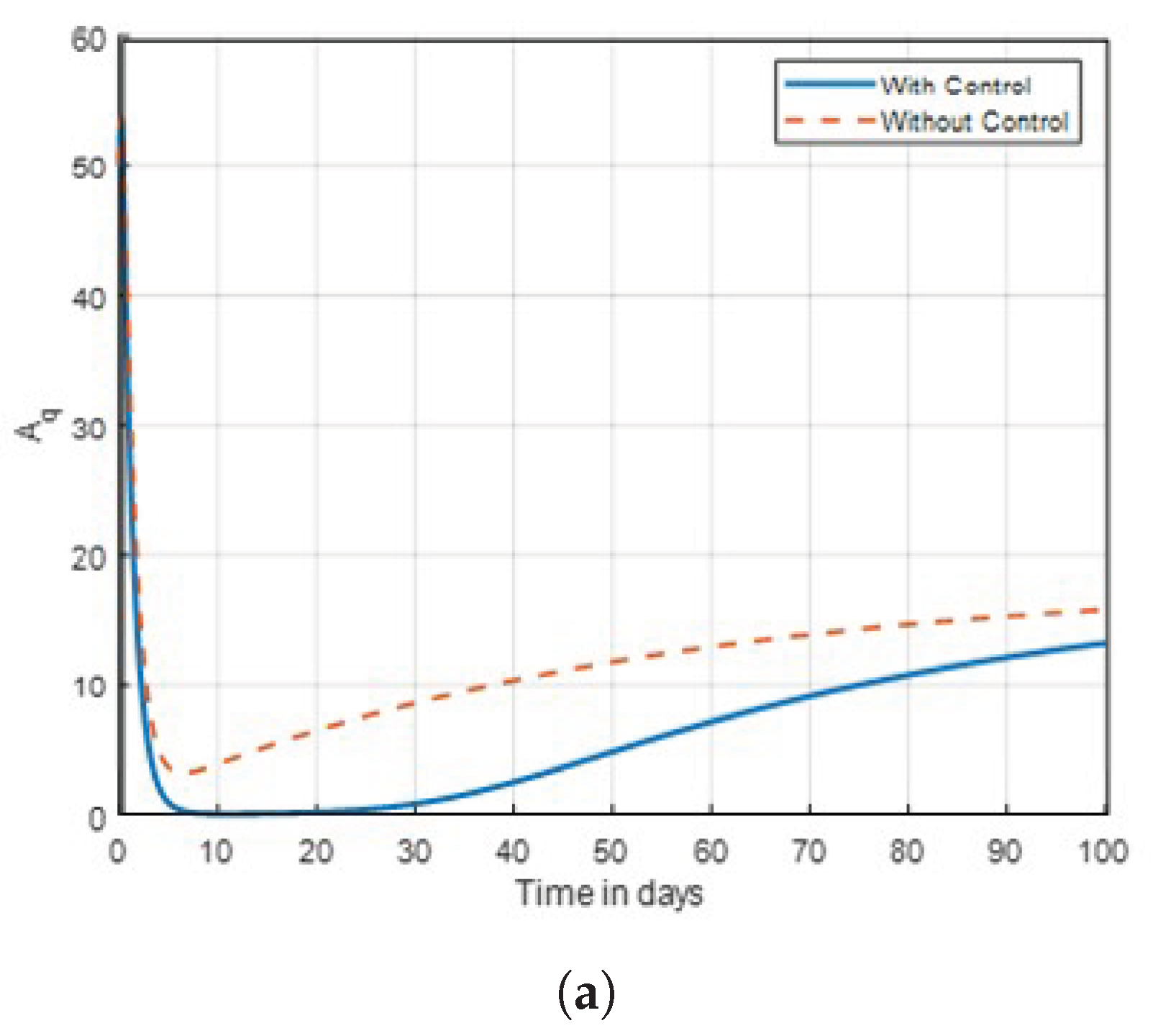

is used on infected mosquitoes and does not work perfectly in reducing the number of vectors. This shows that relying on a single treatment only will not provide effective results. Subsequently, mass awareness and public campaigns on mosquito control are needed. Simply, this is because using insecticides to kill mosquitoes will help in reducing the susceptible. exposed, infected and aquatic mosquito population. As a result, the number of aquatic mosquitoes in the population drops, hence minimising the malaria transmission.

Strategy B:

. The objective function

J is optimized using this technique using the control

, while

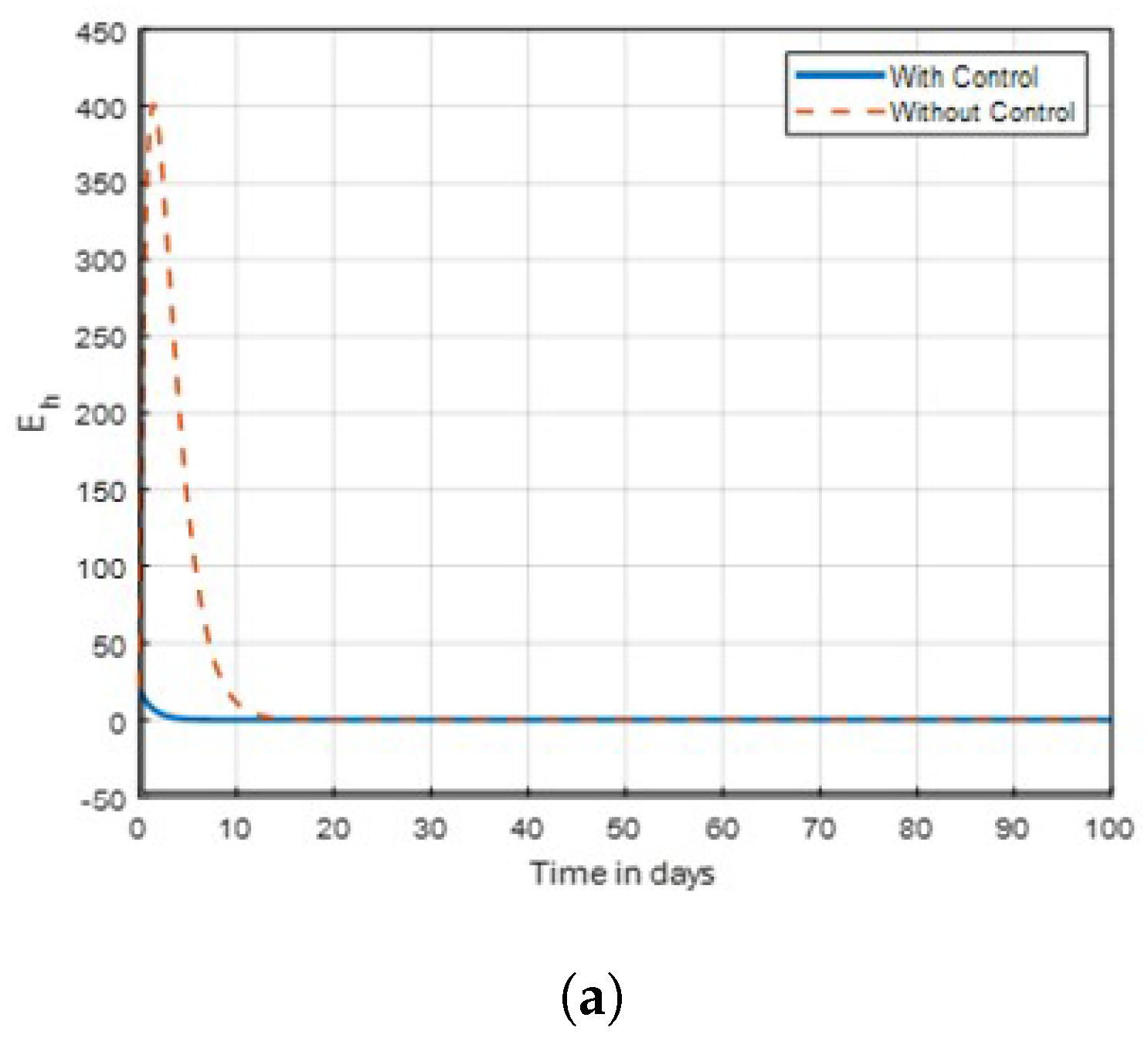

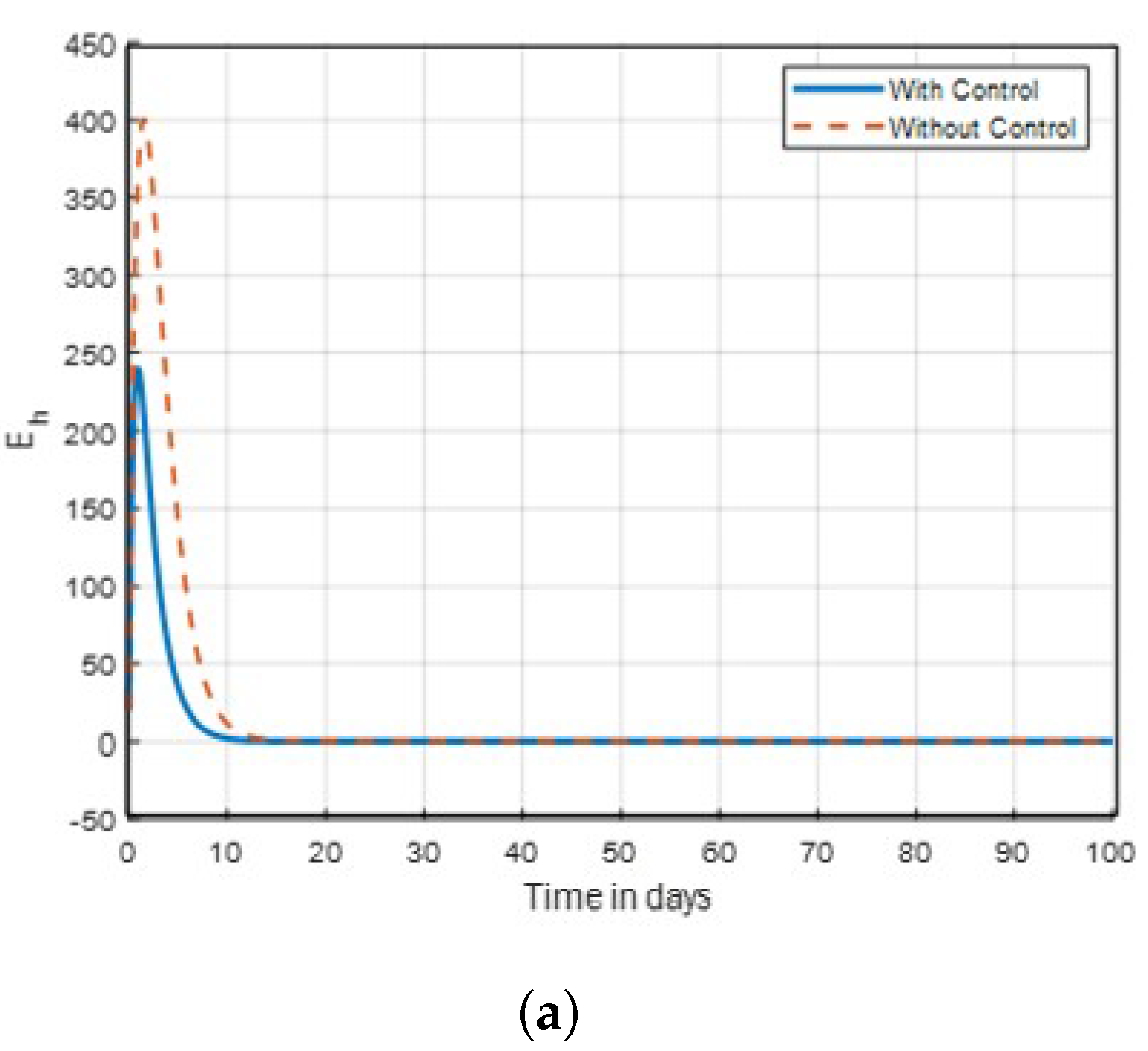

. The control combination strategies on exposed human in

Figure 6 show no significant difference with that of

Figure 7, where mosquitoes seem to be difficult to eliminate on the same dynamics in time. But in

Figure 9, where

as shown, the combination control strategies revealed that lasting net insecticide effective as the number of exposed and infected mosquitoes are decreasing compared to that of aquatic mosquitoes in

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 due to the activities of humans to eradicate infected mosquitoes in a community through the use of insecticides. In this scenario, from

Figure 14 and

Figure 16, it can be deduced where mosquitoes seem to be eliminated using one or two interventions. Finally, it is recommended that these three intervention strategies be implemented simultaneously, especially in endemic areas, to effectively control malaria disease.

Strategy C:

. Is optimised using the objective function

J in this technique, whereas the other controls are set to zero in

Figure 13. Also, from

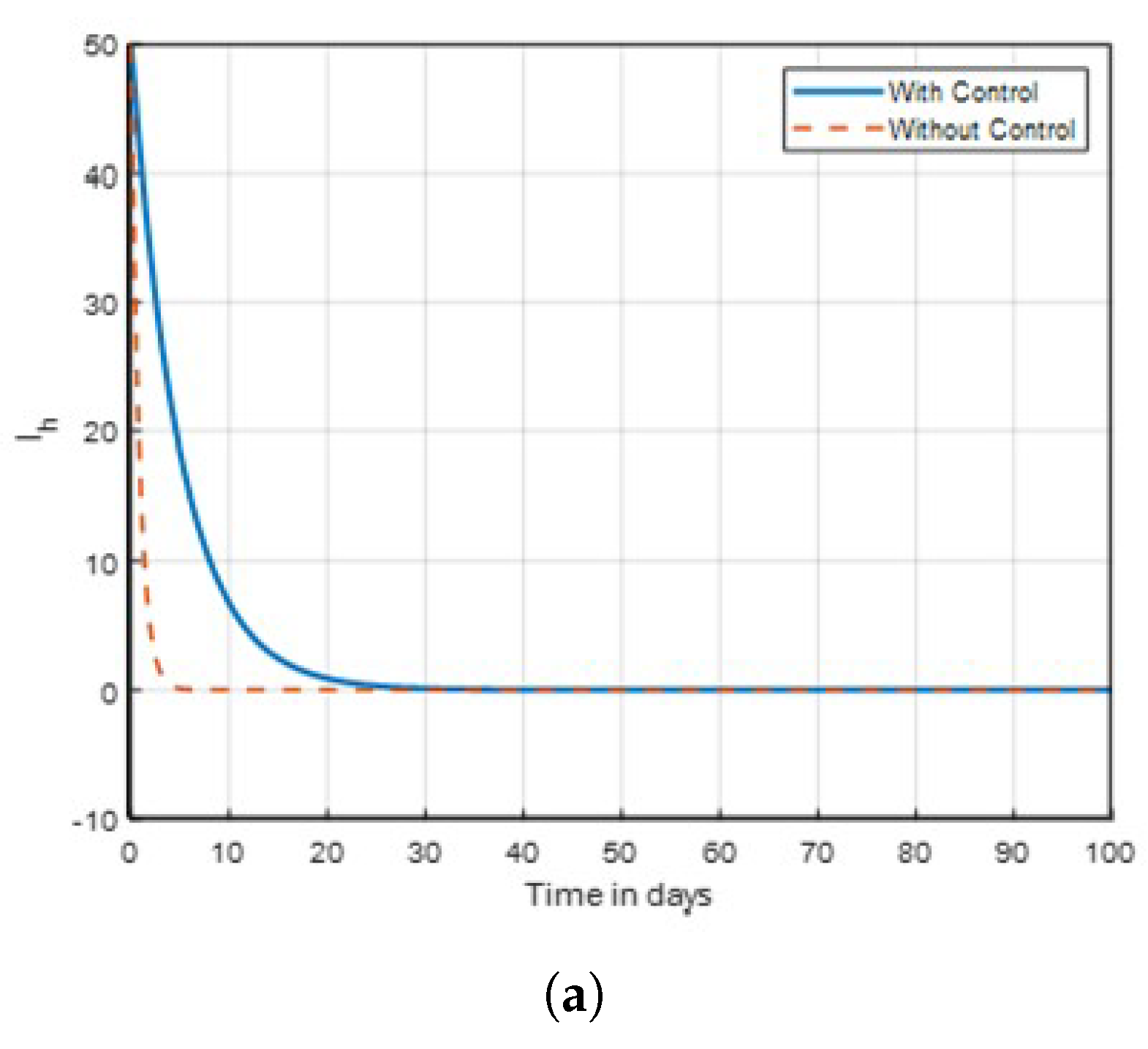

Figure 10, the adult mosquitoes seemed to have been eradicated, and the number of susceptible mosquitoes dramatically decreased throughout the first 100 days. Thus, when the single control strategy in

Figure 8 with traditional method in

Figure 9 is used to combat susceptible mosquitoes, the threat will be lessened compared to when control is not used.

Strategy D:

. Is optimised using the objective function

J in this technique, while

= 0 is set to zero in

Figure 6. Also, from

Figure 10, the number of recovered human seemed to have been progressed, and the number of exposed mosquitoes dramatically decreased throughout the first 100 days in

Figure 14. Thus, when used lasting net insecticide

and

as combined control strategy in

Figure 11, the threat will be lessened compared without control.

Strategy E: combination of

. The objective functional

J is optimised using this technique, the control measures

, and

. The strategy’s applications’ outcomes are displayed in

Figure 15 and

Figure 17, it shows that the mosquito populations of exposed and aquatic are declining as compared to no control.

Strategy F: combination of

. The objective functional

J is optimised using this technique, the control measures

, and

. The control applications are displayed in

Figure 9 and

Figure 11, it shows that the mosquito populations are declining as recovered individuals increasing.

Strategy G: combination of both A, B, and C with

. The objective functional

J is optimised using this technique, the control measures

, and

. The strategy’s applications outcomes are displayed in

Figure 13 and

Figure 17 it shows that the mosquito populations of susceptible, and aquatic are declining as compared to no control. Thus, the intervention technique is successful in reducing the mosquito population in time. Therefore, government decision-makers and all stakeholders are considered in applying all strategies to combat malaria in the specified time. Finally, there is a need to modify insecticide tactics and improve educational initiatives in order to combat the spread of malaria worldwide.

Figure 2.

Graph of susceptible human dynamics shown in time with control .

Figure 2.

Graph of susceptible human dynamics shown in time with control .

Figure 3.

Graph of susceptible human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 3.

Graph of susceptible human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 4.

Graph of aware human dynamics shown in time with varies rates of .

Figure 4.

Graph of aware human dynamics shown in time with varies rates of .

Figure 5.

Graph of aware human dynamics shown in time with varies rates of .

Figure 5.

Graph of aware human dynamics shown in time with varies rates of .

Figure 6.

Graph of exposed human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 6.

Graph of exposed human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 7.

Graph of exposed human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 7.

Graph of exposed human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

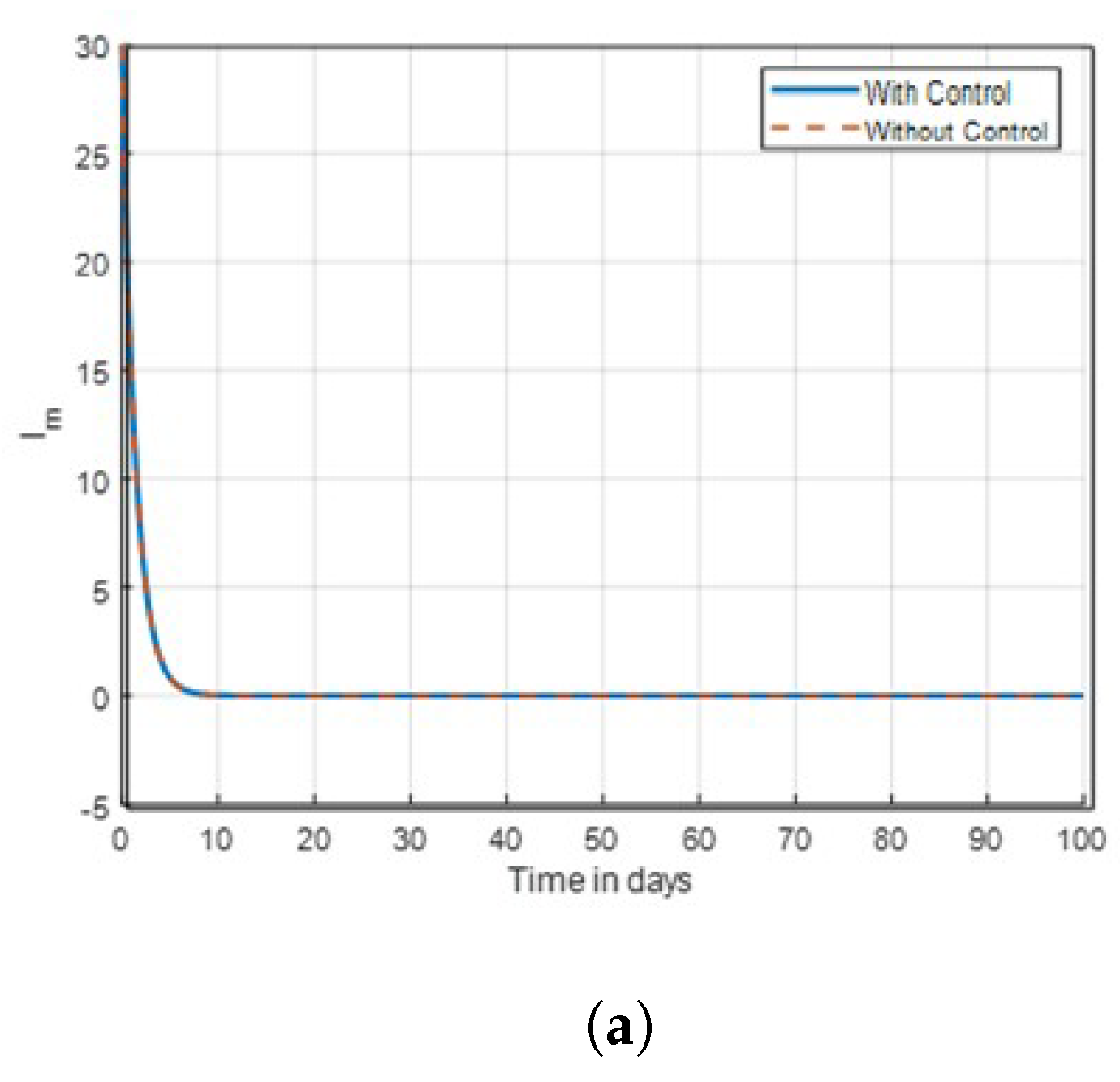

Figure 8.

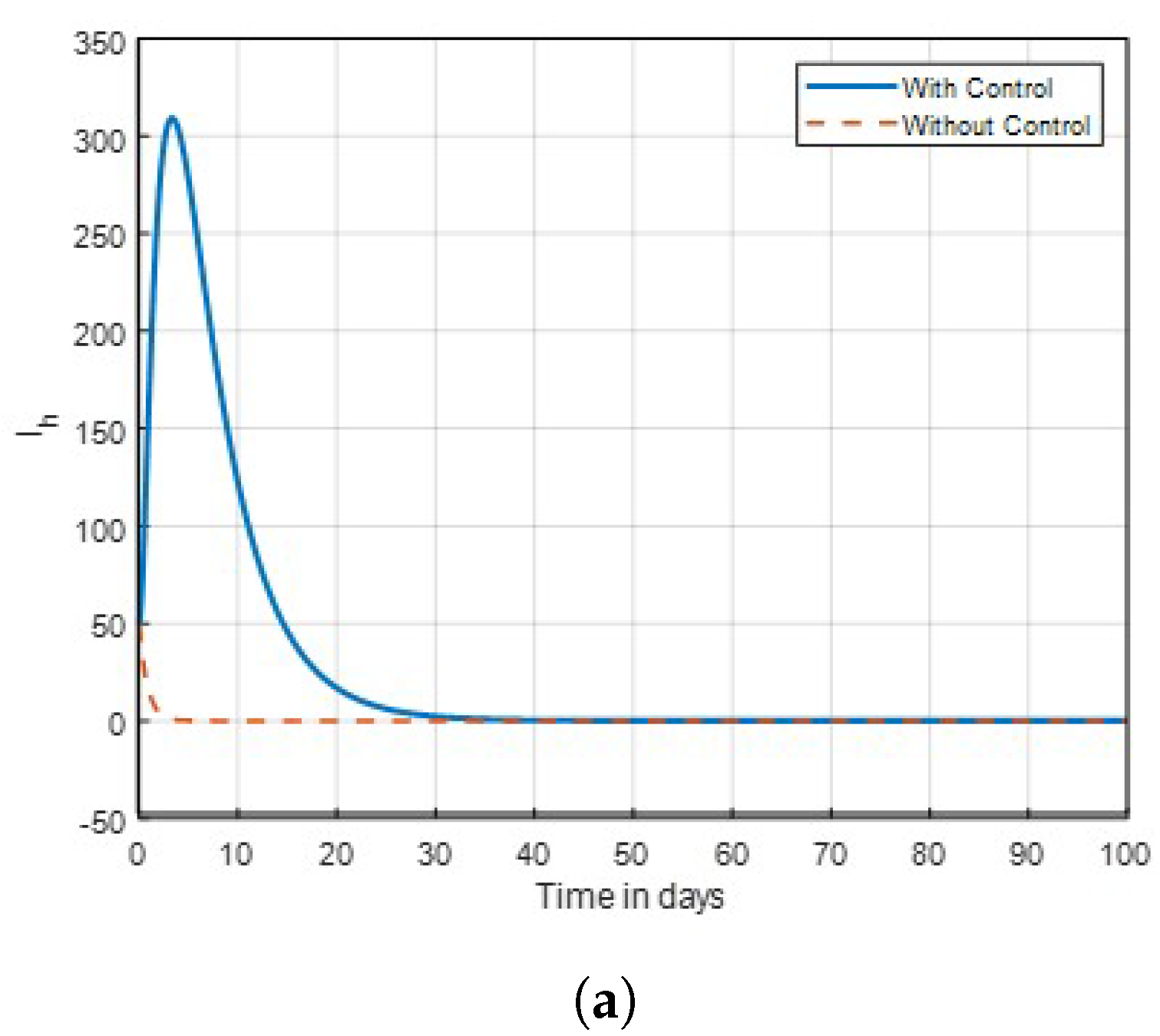

Graph of infected human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 8.

Graph of infected human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 9.

Graph of infected human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 9.

Graph of infected human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 10.

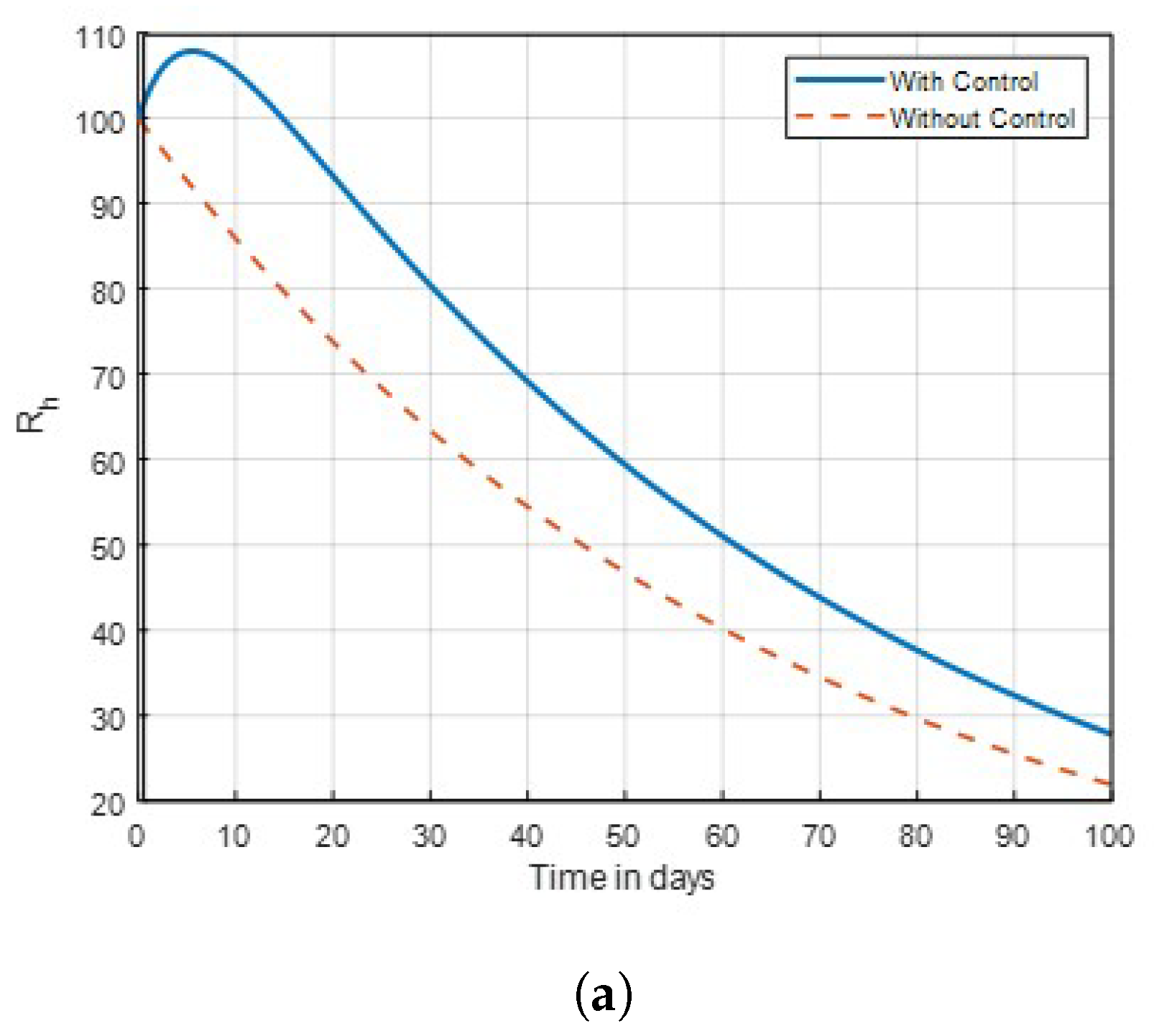

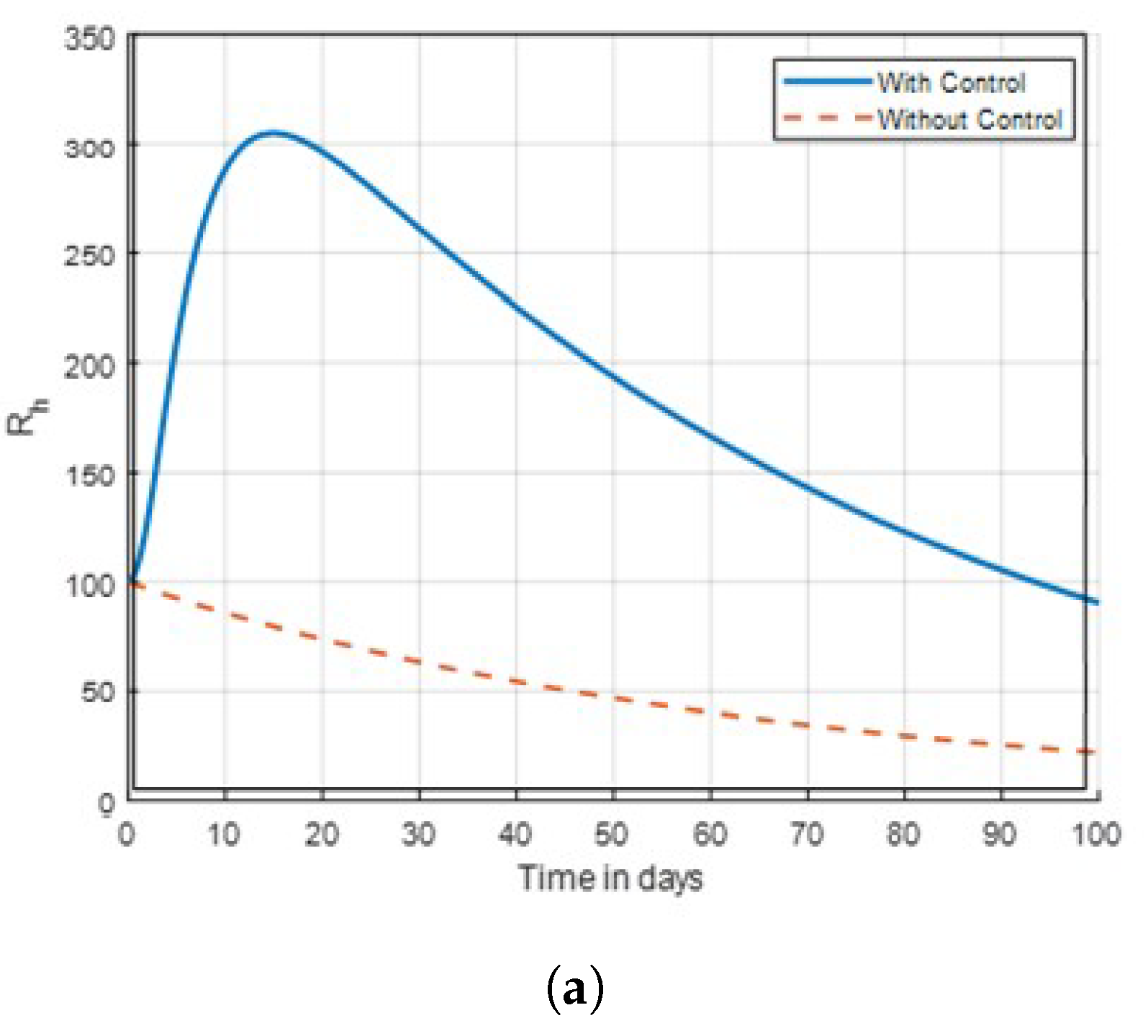

Graph of recovered human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 10.

Graph of recovered human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 11.

Graph of recovered human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 11.

Graph of recovered human dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

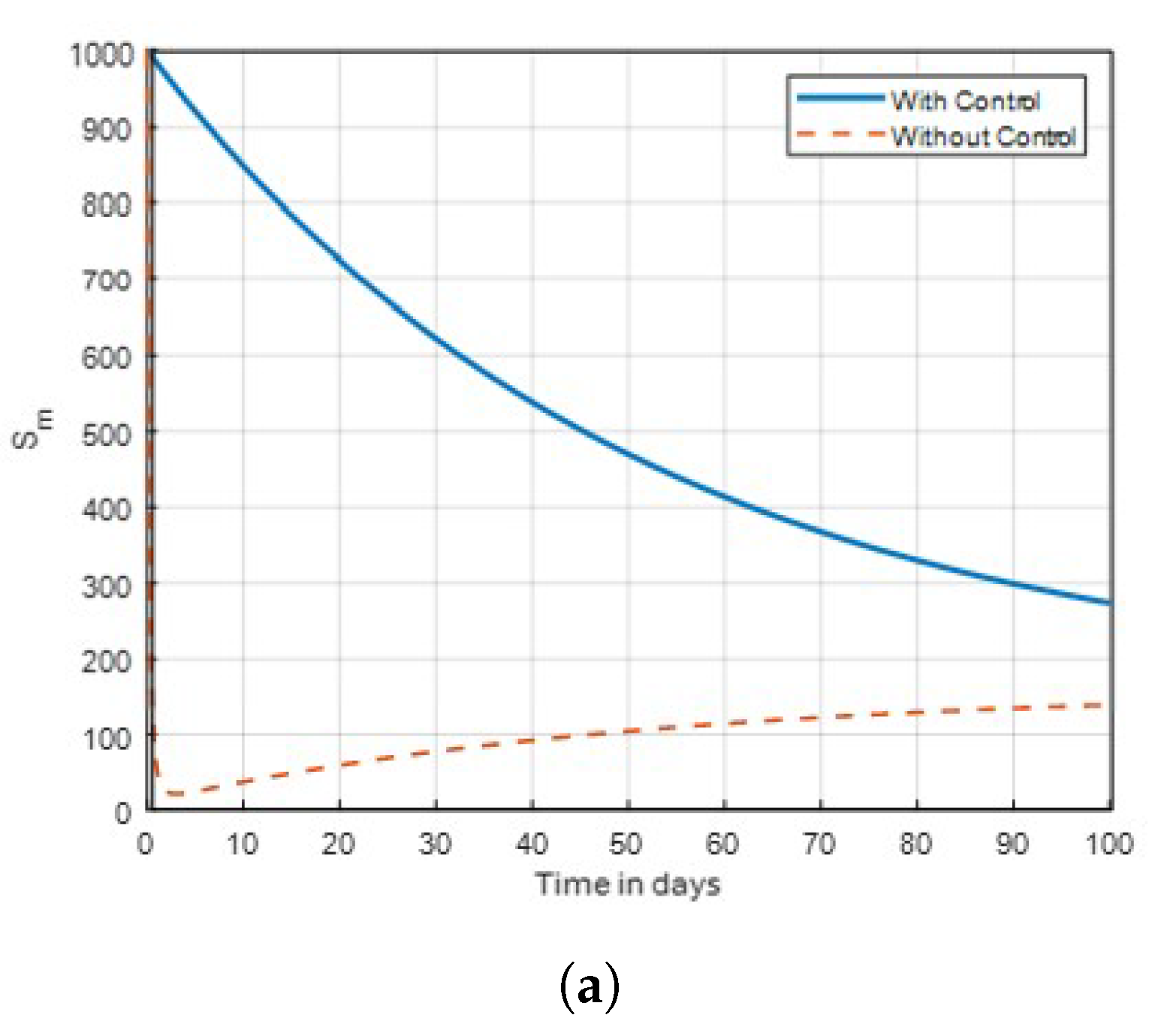

Figure 12.

Graph of susceptible mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 12.

Graph of susceptible mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 13.

Graph of susceptible mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 13.

Graph of susceptible mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

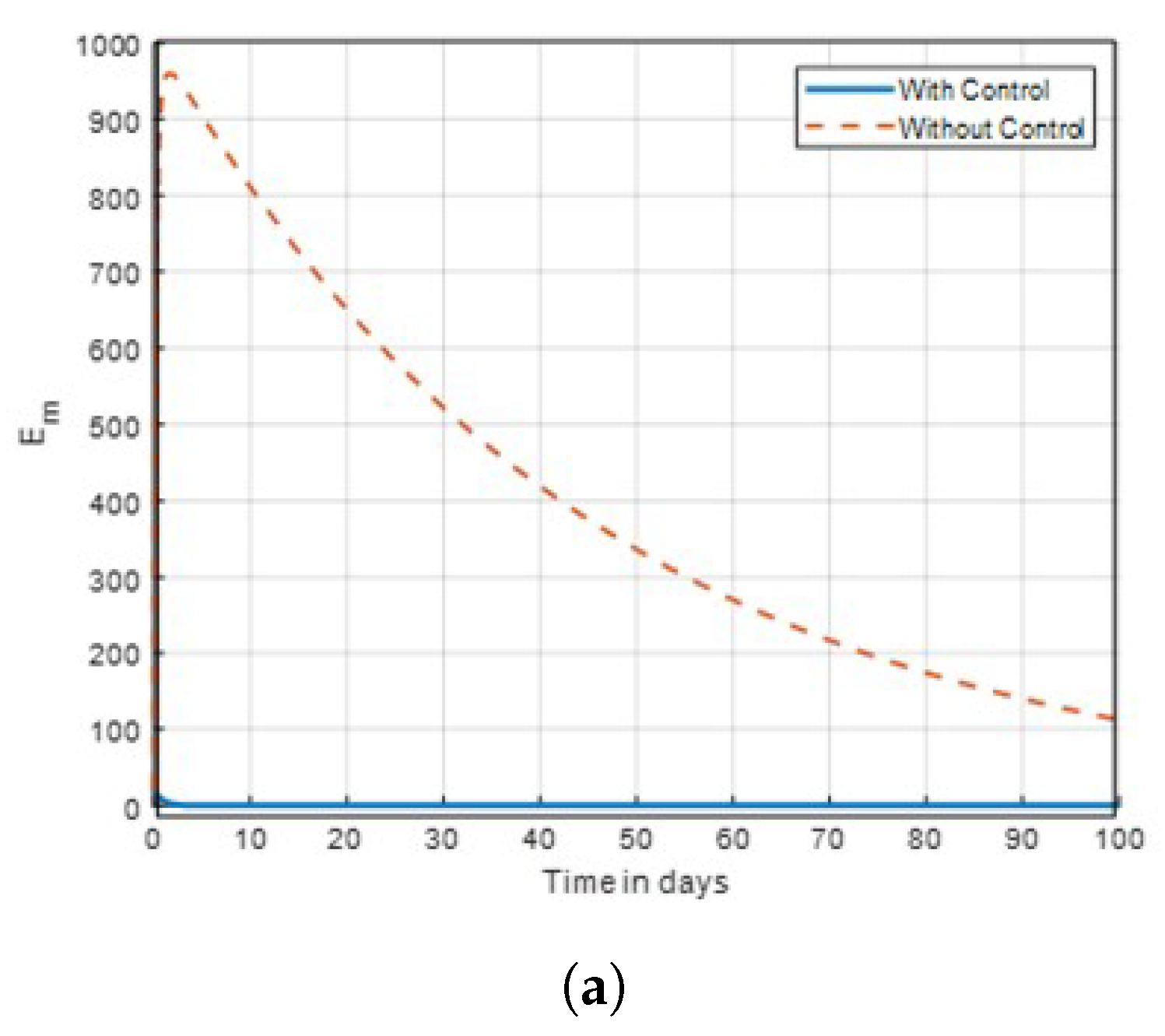

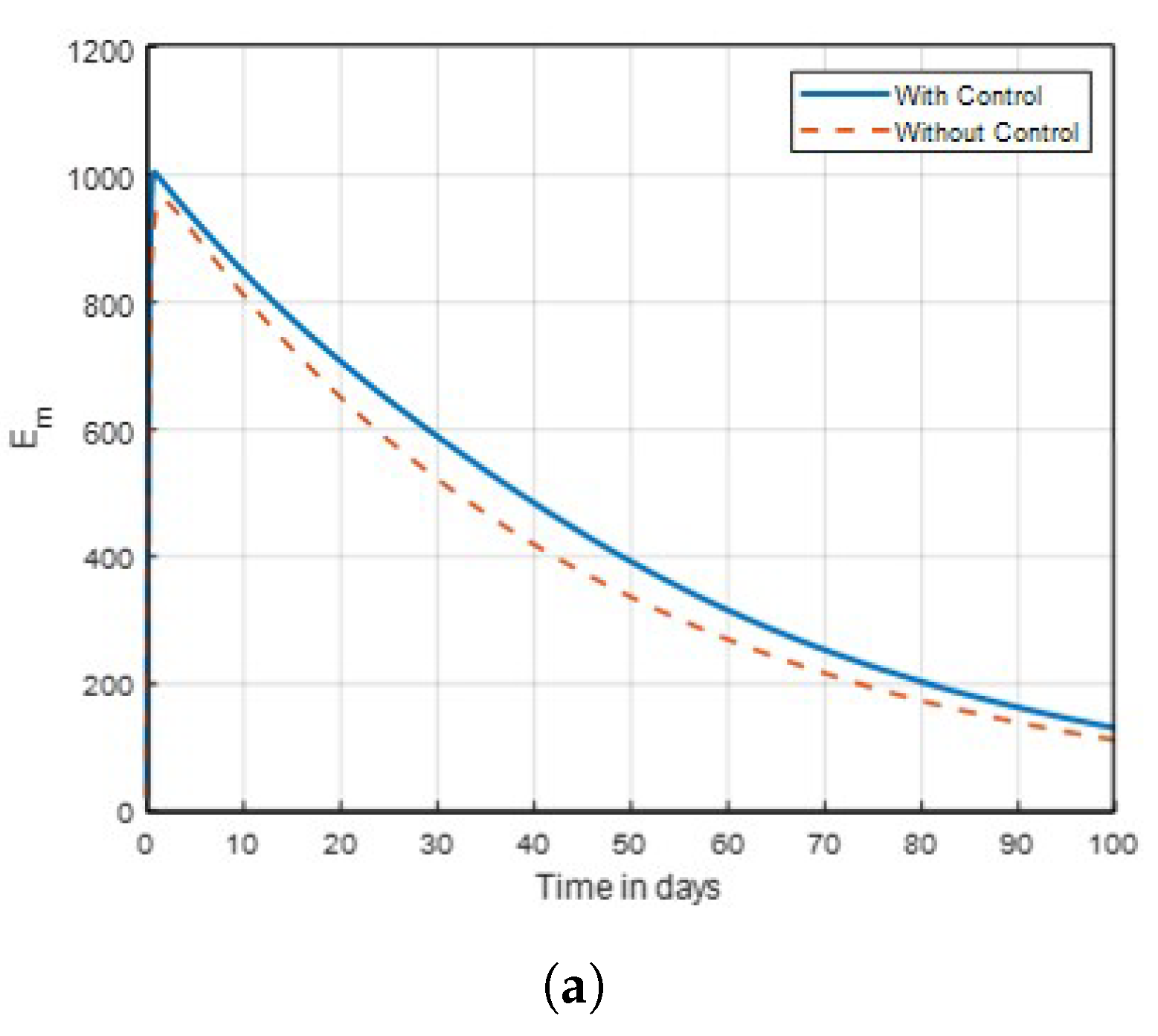

Figure 14.

Graph of exposed mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 14.

Graph of exposed mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 15.

Graph of exposed mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 15.

Graph of exposed mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 16.

Graph of infected mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 16.

Graph of infected mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 17.

Graph of aquatic mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 17.

Graph of aquatic mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 18.

Graph of aquatic mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Figure 18.

Graph of aquatic mosquito dynamics shown in time with control combinations .

Table 3.

Sensitivity index 0f Parameters of the model.

Table 3.

Sensitivity index 0f Parameters of the model.

| Parameters |

Parameter value |

Sensitivity value |

Sensitivity index |

|

0.041, Estimated |

0.5 |

Positive |

|

220, [25] |

0.5 |

Positive |

|

0.042, [25] |

-0.4998702261 |

Negative |

|

0.068, [25] |

0.00004368634364 |

Positive |

|

0.05, Estimated |

-0.00007066908525 |

Negative |

|

0.002, Estimated |

0.5 |

Positive |

|

0.00042, Estimated |

0.5 |

Positive |

|

0.0001645, Estimated |

0.4998972084 |

Positive |

|

0.003, Estimated |

0.5 |

Positive |

| a |

0.072, Assumed |

0.5 |

Positive |

|

0.00652, [25] |

0.5 |

Positive |

|

0.168, Estimated |

-0.0001027913635 |

Negative |

Table 4.

Parameters of the Model with their Values and Sources.

Table 4.

Parameters of the Model with their Values and Sources.

| Parameters |

Parameter value |

|

0.041, Estimated |

|

220, [25] |

|

0.042, [25] |

|

0.068, [25] |

|

0.05, Estimated |

|

0.002, Estimated |

|

0.00042, Estimated |

|

0.0001645, Estimated |

|

0.003, Estimated |

| a |

0.072, Assumed |

|

0.00045, Estimated |

|

0.001, Assumed |

| b |

0.1, Assumed |

|

0.0147, Estimated |

|

0.0018, Estimated |

|

0.0001, [40] |

|

0.08, Estimated |

|

0.00652, [25] |

|

0.168, Estimated |